- Centre for Evidence Based Early Intervention (CEBEI), Bangor University, Bangor, United Kingdom

Introduction: Growing numbers of children enter mainstream education without the skills needed to prosper in the school environment. Without additional support, these children face poor long-term outcomes in terms of academic attainment, mental health difficulties and social problems. The aim of this study was to investigate the feasibility and acceptability of school-based delivery of the Books Together dialogic book sharing program to groups of parents, and to explore whether it impacts parent and child outcomes in order to facilitate school readiness.

Methods: Parents of children aged 3–5 years old (n = 16) were recruited from four North Wales primary schools. Video observations of parent/child interactions, a gaming format measure of expressive child language ability, parent-report measures of children’s behavior, and social-emotional ability and of their parental competence were collected pre- and post-intervention. Thematic analysis of interviews with parents and the school-based staff who delivered the program explored feasibility and acceptability of the program.

Results: Significant post-intervention increases in observed positive parenting and child expressive language skills and significant reductions in observed negative parenting were found. Parents reported significantly higher rates of child prosocial behavior and social/emotional ability as well as improved parenting competency at follow-up. Thematic analysis showed that staff and parents were satisfied with the program and that it was feasible to deliver in a school environment.

Discussion: The Books Together program is a low-cost intervention that, when delivered by school-based staff, shows promise for increasing the use of parenting strategies that build children’s language and social/emotional skills associated with school readiness.

1 Introduction

In the UK, a significant number of children start school with language skills below what is expected for their age (Bercow, 2018) with concerning reports of further increase due to the COVID-19 pandemic (YouGov, 2022). Recent nursery closures and social restrictions as a response to COVID-19 have reduced learning opportunities for children (Araujo et al., 2021) and UK funding for schools has been significantly reduced despite the increase in the number of children needing additional learning support (YouGov, 2020). As a result, the number of UK children with additional learning needs has increased significantly over recent years and, currently, almost half of UK children fail to meet typical developmental milestones in communication, language and personal, social, or emotional development at school entry (YouGov, 2020). Many children with additional learning needs live in socially disadvantaged circumstances and experience more frequent developmental delays that are clearly identifiable by age 5 (Ofsted, 2014). This is a public health concern as poor cognitive and social/emotional development at age 5 are strongly correlated with longer term academic underachievement, mental and physical health difficulties, poor social skills and unemployment (Jones et al., 2015).

Communication and language skills are the strongest predictors of school readiness (Çakıroğlu, 2018) and are the underpinning skills needed for executive function and social/emotional competencies (Slot and von Suchodoletz, 2018; Wolf and McCoy, 2019). Children who meet their developmental milestones in language and communication at age 5 can play, talk, listen, understand, and pay attention, allowing them to fully engage in their learning environment (Adams et al., 2005). The attainment of language skills primarily depends on exposure to child directed speech from caregivers during the preschool years (Zeanah et al., 2011; Golinkoff et al., 2019) and is strongly influenced by the level of interactive dialog that children are exposed to with adults in their immediate environment (Eun, 2010).

Dialogic book sharing (DBS) involves interactive discourses, in which the adult follows the child’s interest, and is associated with prolonged joint attending by providing a rich and effective environment for promoting child development (Doyle and Bramwell, 2006). DBS interventions are usually delivered to caregivers in small groups over several sessions in which key strategies are demonstrated through facilitator support, modeling, viewing video tapes, and role playing or practicing the strategies taught. In addition, picture books and summary sheets are typically provided containing key points from each session to enable home practice (Dowdall et al., 2020).

Dialogic book sharing has shown promise in terms of developing pre-school children’s skills associated with school readiness (Cooper et al., 2015; Vally et al., 2015; Murray et al., 2016). During DBS caregivers encourage children to become the storyteller through open questioning, expansion of children’s utterances, praise, and encouragement, linking book content to the child’s experience, and labeling objects within the book (Arnold et al., 1994). This involves sensitively supporting children’s interest by engaging them in reciprocal interactions over the content of picture books (Murray et al., 2016). These interpersonal interactions increase children’s interest in books and foster higher-level thinking, and an ability to engage in extended discourse, promoting more diverse vocabulary than is achieved by reading to children (Van Kleeck, 2014). Evidence for DBS is so strong that it has been termed a ‘vocabulary acquisition device’ (Ninio, 1983; Barcroft et al., 2021), laying the groundwork for children’s successful social/emotional expression and understanding (Murray et al., 2016).

Pre-school programs that teach DBS strategies to parents demonstrate accelerated child development outcomes (Blom-Hoffman et al., 2007; Mol et al., 2009; Brannon et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2016; Towson et al., 2016; Dowdall et al., 2020) and may be a cost-effective and financially viable way to increase children’s school readiness (Whitehurst et al., 1994; Dowdall et al., 2020). Several well controlled studies, mainly carried out in the US, have demonstrated that carers can be trained to engage in high quality dialogic reading, and that, when such training is provided, there are significant benefits to child development (Blom-Hoffman et al., 2007; Brannon et al., 2013). Furthermore, in recent years, there has been increasing cross-cultural evidence of the gains of training parents in DBS skills. For example, Knauer et al. (2019) taught parents in Kenya to talk about pictures in books and found improved parental and child vocabulary with children of illiterate caregivers benefiting just as much as children of literate caregivers. Similar gains have been reported from Mexico, Bangladesh, China, Brazil, South Africa, and New Zealand (Valdez-Menchaca and Whitehurst, 1992; Chow et al., 2008; Opel et al., 2009; Cooper et al., 2015; Weisleder et al., 2018; Scott et al., 2020). These studies strengthen the evidence for the benefits of DBS training for parents in improving child language skills during the pre-school period.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of DBS interventions found that improved parental DBS competence during training facilitated the reciprocal exchanges required to nurture children’s expressive and receptive language ability (Dowdall et al., 2020). Effects were unrelated to caregiver education or child age; however, positive outcomes were mediated by program length. Another important finding was that group-based DBS interventions were significantly more effective in improving child language outcomes than one to one interventions. This may be because group-based DBS training provides a supportive environment and promotes active engagement, in which participants also benefit from the social capital of the group (Beschorner and Hutchison, 2016).

In the UK Murray et al. (2023) adapted and tested a new version of their program for parents of younger children in a randomized controlled trial with 218 caregivers of children aged 2.5 to 4 years. Parents were recruited through children’s centers in the most deprived areas of Reading and the study evaluated the impact of the intervention on child cognitive (language, attention, and executive function) and social/emotional development, and on parenting strategies. Intention to treat and per-protocol analysis showed no significant post-intervention impact in terms of child outcomes, although there were some effect size benefits, but significant effects were found for relevant parenting behaviors. An analysis of outcomes for the engaged group (59% of the sample) showed that the intervention produced a significant effect for child expressive language and comprehension, however, it appeared that the engaged sample were from a predominantly high income group further reinforcing the need for developing effective strategies to target the most vulnerable families.

Home-school relationships are significant predictors of children’s academic attainment (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2000; Kingston et al., 2013) as well as a smooth transition into school (Carlton and Winsler, 1999) regardless of child age or ethnic origin (Wilder, 2014). Engaging families in the learning process from the very beginning maximizes children’s developmental outcomes (Bridgemohan et al., 2005). In addition, strong home/school partnerships increase parental satisfaction and efficacy and supports teachers with their work (Epstein, 2010) whereas lack of parental involvement in their education negatively affects children’s perception of school and ambition to achieve (Sheppard, 2009). One of the greatest challenges to building effective home/school links is engaging parents who experience poverty, isolation, and poor mental health, as these reduce the parental resources needed to fulfill the parenting role (Skreden et al., 2012; Azmoude et al., 2015). Research into ways of promoting home/school partnerships is limited and inconsistent (Welsh et al., 2014), consequently, it is important to identify ways to support parents, particularly socially disadvantaged parents, to reduce home/school communication barriers that influence children’s successful transition into school. Strategies are needed to encourage parental involvement as their children start school. Providing the parents of children with additional learning needs with the skills and resources needed to develop their language and communication skills could support children’s school readiness and build effective home-school partnerships.

1.1 Rationale for the study

Dialogic book sharing parenting programs support early child development but many children are arriving at school with poor school readiness skills and have reduced life chances perpetuating the cycle of disadvantage (Welsh et al., 2014). There is limited evidence demonstrating school based delivery of DBS with parents of children aged 3–5 years. Implementing DBS parenting interventions within school settings when children start, or are in their early school years, may achieve improved language outcomes for children and additionally support efforts to build good home/school links (Cristofaro and Tamis-LeMonda, 2012; Vernon-Feagans et al., 2020). Delivering DBS programs in, and through, educational settings may further disseminate the positive effects of DBS and improve school readiness outcomes (Welsh et al., 2014).

The current study was designed to:

i) Test the feasibility and acceptability of the Murray and Cooper ‘Books Together’ program delivered by school-based staff to parents of children aged 3–5 years.

ii) Explore initial effectiveness of the program in terms of its impact on child language and social-emotional competencies and parenting skills.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Design

Data were collected as part of a pre-post pilot study using a mixed methods approach to explore the impact of school-based delivery of the Books Together program (Murray et al., 2018). Quantitative analysis assessed outcomes using a repeated measures design via questionnaires, a gaming format child language assessment, and direct observation of parent/child interactions. Qualitative interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis to explore satisfaction with, and the feasibility of delivery of, the program for parents and school-based facilitators.

2.2 Participants

Details of the study were sent to all schools in North Wales using a monthly education bulletin disseminated by the Regional School Effectiveness and Improvement Service for North Wales. Schools were invited to contact the research team with expressions of interest. Five primary schools responded and were recruited through direct telephone contact and visits to the school. Two schools delivered teaching predominantly through the medium of Welsh and the three predominantly in English. Prior to program delivery one Welsh school withdrew from the study as they were unsuccessful in recruiting parents, therefore four schools participated in the study.

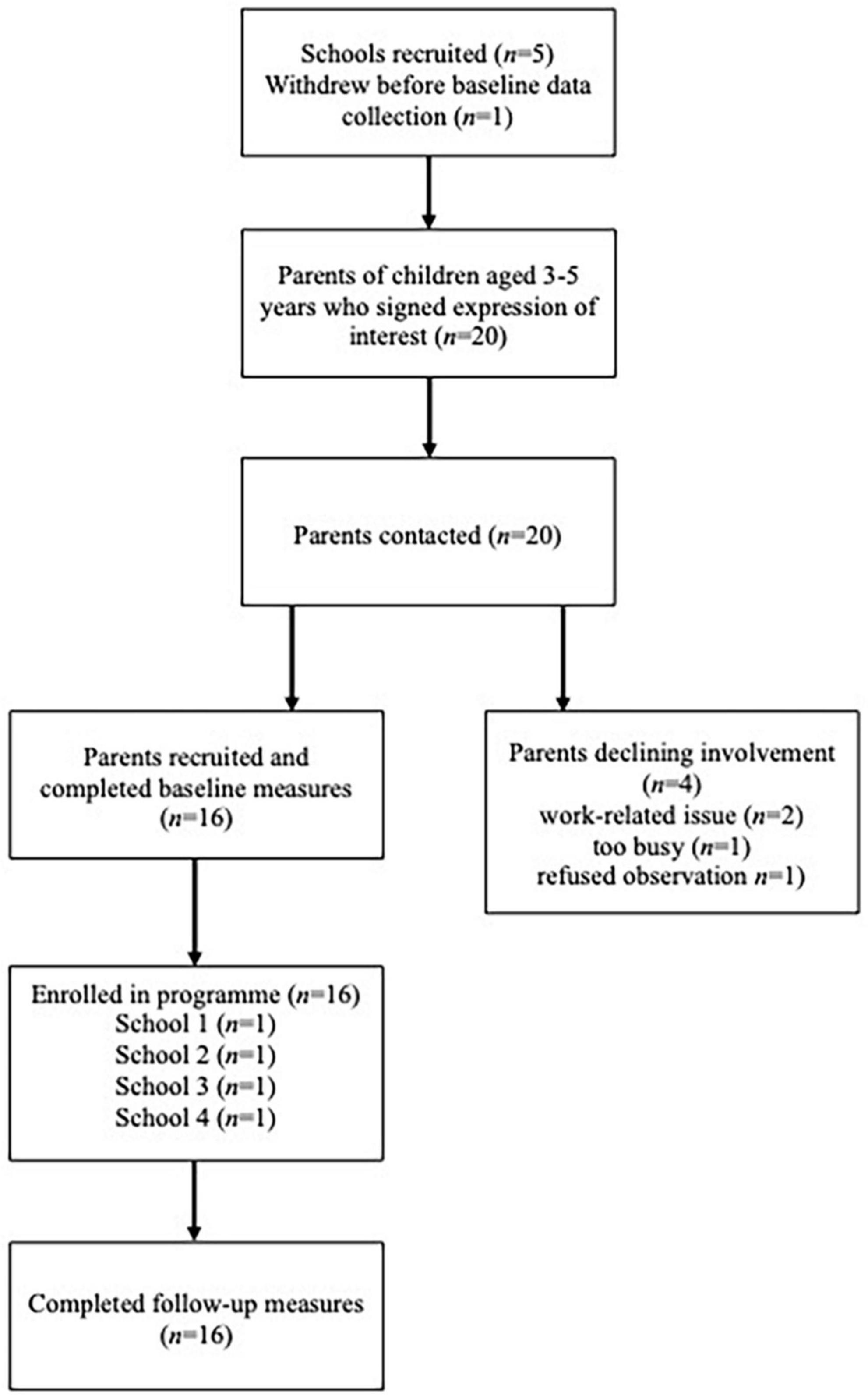

A convenience sample of parents were recruited by the schools who sent letters home and/or directly contacted families of children in need of support in areas of language, behavior, and/or social interactions. Families were eligible for inclusion if they could commit to the 7-week program and had a child aged 3–5 years in the participating school. Five parents from each of the four schools agreed to participate, however, one parent from each school withdrew before program delivery (see flow diagram in Figure 1).

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Family demographic questionnaire

This questionnaire captured information regarding basic socio-demographic details, including characteristics of the family structure, parental education, and participant age.

2.3.2 Feasibility outcomes

Feasibility outcomes were operationalized as program engagement (number of sessions attended) and acceptability (explored using semi-structured interviews with parents and school-based staff).

2.3.3 Parent-child interactions

The observation was based on categories from the Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS; Robinson and Eyberg, 1981) to assess parent/child interactions during a 10-min shared reading activity. Five verbal behavior categories: unlabeled praise, labeled praise, encouragement, reflection, and negative parenting were used to capture parenting behaviors taught in the programme. The DPICS is a widely researched measurement tool and has shown good reliability (r = 0.91 parent behavior; r = 0.92 child behavior; Robinson and Eyberg, 1981). An additional three verbal categories [academic coaching, social emotional coaching and linking to child experience (expansion)] that were developed for an earlier school readiness trial were also coded using the same process (Hutchings et al., 2020).

2.3.4 Child behavior

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997) is a brief parent-reported behavioral screening measure for 2–17-year-olds to detect social-emotional and behavioral problems. The SDQ has 25 items measured on a 3-point Likert scale, with responses not true, somewhat true, and certainly true. It has five subscales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity and inattention, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behavior. A total difficulties score is attained by combining scores from the four problem subscales. Higher scores indicate greater levels of difficulties/strengths. The SDQ has good internal consistency (mean a = 0.73), test–retest stability (r = 0.62), and discriminant validity (Stone et al., 2010).

2.3.5 Child social-emotional ability

The Ages and Stages Social–Emotional questionnaire (ASQ:SE; Squires et al., 2001) is a parent-completed social-emotional screener for children aged between 1 and 6 years. Each questionnaire contains 39 questions covering seven behavioral areas: self-regulation, compliance, adaptive functioning, autonomy, affect, social-communication, and interaction with people. Items score on a three-point Likert scale, often/always, sometimes, or rarely/never which are converted to points of 10, 5, and 0, respectively. Lower scores (0–70) indicate expected levels of social-emotional competency, medium scores (70–85) indicate further monitoring is required, and higher scores (85 and above) indicate high risk of current social-emotional problems. The ASQ:SE has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82) (Squires et al., 2001).

2.3.6 Parental competence

The Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (PSOC; Johnstone and Mash, 1989) is a 17-item self-report questionnaire that measures parents’ sense of their own competence using two broad scales: efficacy and satisfaction. Responses are rated on a six-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. The PSOC has strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80) (Ohan et al., 2000).

2.3.7 Child language

The Early Years Toolbox (EYT; Howard and Melhuish, 2016) is a 45-item iPad-based assessment of children’s ability to identify and name objects to assess child language ability and takes around 5 min to complete. Children respond verbally to images on the iPad, and responses are recorded by the researcher on the app by clicking one of three individual keys: correct response, specific response, or do not know. The measure displays excellent internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92) (Howard and Melhuish, 2016).

2.4 Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from Bangor School of Psychology Ethics committee (application number: 2019-16439). All study participants provided written informed consent before participating.

2.5 Procedures

Data were collected from participants during two home visits, one following informed consent (baseline) and one immediately following program completion. Semi-structured interviews with parents and school-based staff were also conducted after program completion. Each parent/child dyad was observed and video-recorded for 10 min in a reading observation for later analysis. An Usborne Farmyard Tales series book, for children aged between 3 and 6 years, was provided and parents were asked to look at the book with their child for 10 min. The books include brief simple text in a bright and colorful context. To control for prior experience “The Naughty Sheep” was used at baseline and “Pig got Stuck” at follow-up. Parents were asked to share the book with their child for 10 min in a way that was most comfortable to them. The researcher informed parents when the 10 min had elapsed. A camera was set up to record the interaction and a timer used to time the duration. If the parent finished the book before the 10 min had ended, the researcher prompted them to continue by saying “There are X minutes remaining, would you mind carrying on please.” All researchers completed training prior to any data collection. Following training, the first author (primary coder) coded all video observations, and the second author (the criterion coder) coded 25% of randomly selected videos for inter-rater reliability. The interclass correlations (ICC) were between 0.795 and 0.987.

Schools released a staff member to attend the 2-day DBS training in January 2019 and for 2 hours a week for 7-weeks to deliver the program to parents between February and April 2019. Staff were trained by a certified trainer who had initially attended training delivered by the South African Mikhulu Trust that led the earlier South African work.

School-based staff delivered the seven session Books Together program over seven 2-hour weekly sessions (Murray et al., 2018). A member of staff from each school (one teacher and three teaching assistants) were trained and provided with the resources needed to deliver the program. Each session introduces specific strategies. Topics include building and enriching language, numbers, and comparisons, linking to child experience, feelings, intentions, perceptions, and strengthening relationships. During the first hour PowerPoint slides, illustrative video clips and group discussion take place. During the second hour, children join their parents under the guidance of the facilitator, to practice the strategies taught that week. Parents receive feedback and instruction for continued practice. A new book and handout are provided after each session for home practice. The weekly handout (one side of A4) briefly explained the skill for that week’s session and gave examples of strategies to use with that week’s book (e.g., open ended questions to exploring characters feelings during week 4). Parents are encouraged to practice for 10–15 min a day with their child. Discussion on home practice is explored at the start of the following session.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Measures of parental competence, child behavior, language, and social-emotional ability were analyzed using SPSS. Data were scored according to the guidelines for each measure. Paired samples t-tests were performed to determine intervention effects. The SDQ, ASQ:SE, and behavioral observation measures violated the assumption of normality and were therefore analyzed using an equivalent non-parametric test (Wilcox Signed Rank). Effect sizes were calculated including Cohen’s d for the paired t-test and r for the non-parametric Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. Cohen’s classifications were used for interpretation (0.1 small, 0.3 medium, 0.5 large) (Cohen, 1988).

Interviews were recorded to capture in their own words, the ideas, views, and experiences of parents and facilitators who had completed/delivered the program. Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2014) was used to establish the feasibility and acceptability. The recorded interviews were sent to an external transcribing company and, once transcribed, were read, and re-read by the first author to generate a list of ideas to enable themes to be identified. Transcripts were also coded independently by the third author for inter-rater reliability.

3 Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

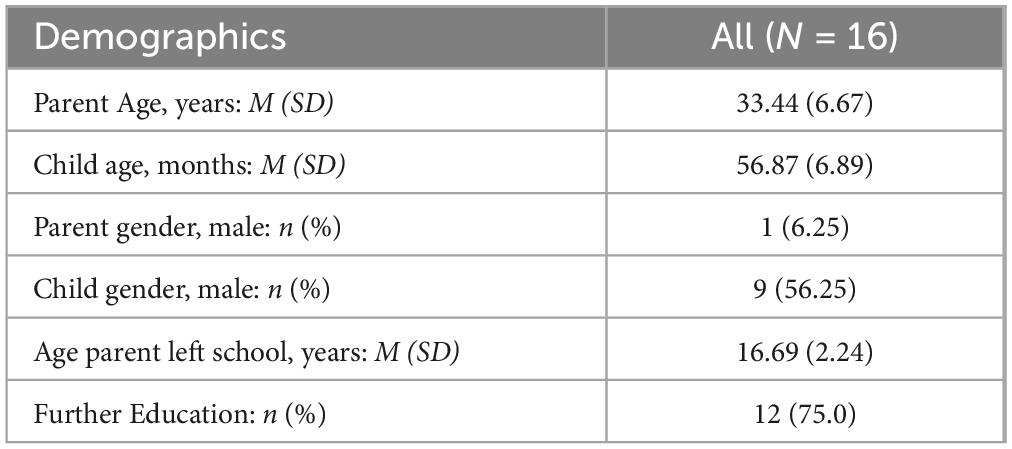

Fifteen mothers and one father participated. Nine children (56%) were male and seven (44%) lived in single parent homes. Nine parents (56%) were unemployed and four (25%) had left school without qualifications (see Table 1). Most children (n = 11, 69%) scored high or very high on the parent reported SDQ indicating significant behavioral concerns. Seven children (44%) scored as high-risk on the ASQ:SE suggesting significant social-emotional difficulties.

3.2 Program engagement

All participants completed the program, with 12 parents (75%) attending at least six sessions and 10 (63%) attending all seven (mean attendance = 6.19, SD = 1.28).

3.3 Feasibility and acceptability

3.3.1 School-based staff

All four facilitators undertook an interview after completing program delivery. Two main themes related to feasibility and acceptability were identified: Program feedback; Feasibility and challenges. All facilitators reported that the program developed supportive friendships with parents in a safe, encouraging environment and that it was easy to deliver and the process was enjoyable. They described how the group setting created a friendly atmosphere to deliver the content, which was well-supported by the program resources. The colorfulness and diversity of the books appealed to everyone and created enjoyable learning experiences for children. Two facilitators thought that the program was an asset to the school curriculum. Two facilitators also reported that the program offered themselves creative ideas to engage children with books and facilitated improved child engagement during lessons. In addition, three facilitators reported that the program taught them to adjust their teaching techniques during the group sessions to support parental learning.

Some barriers were reported by school staff including group management challenges (n = 2) and lack of resources to deliver such as access to available rooms (n = 2) and software to deliver the PowerPoint content. Two utilized their own personal equipment for content delivery. Furthermore, all reported challenges with the poor video and volume quality of the equipment that the program provided, which obstructed the effectiveness of delivery.

3.3.2 Parents

All sixteen parents completed an interview following program completion. Three main themes were identified: Benefits for parents; Child benefits; Program and resource feedback. All parents reported that the program was empowering, supportive and well-informed, that it developed their communication skills and that their children responded positively. Twelve (75%) parents said that they improved in their ability to coach children to consider their own and other’s feelings, and that this enabled them to resolve their children’s behavior challenges more effectively. In addition, the one-to-one time that book-sharing created was valued by parents (n = 9, 56.25%), as it offered an enjoyable child-centered activity that improved interactions and reinforced positive bonds and parents began to feel closer to their children. Twelve (75%) parents valued the interactive nature of the group as it provided an opportunity to make new friendships and share views and opinions in a non-judgmental atmosphere. Parents also enjoyed engaging with their children’s learning experiences during school and valued the home/school partnerships that was created (n = 8, 50%), feeling more welcomed and comfortable in the school setting and consequently, more interested in their child’s school life (n = 10, 62.50%).

All parents reported benefits to their children’s cognitive and social/emotional development. Book-sharing was viewed as an age-appropriate social/emotional learning experience to support children to develop empathy, recognize the feelings of themselves and others, regulate emotions, and cultivate healthy relationships (n = 13, 81.25%). Eleven parents (68.75%) also reported that book-sharing reinforced children’s enjoyment of books and strengthened their focused attention. In addition, four parents (25%) thought that children’s expressive language improved as book-sharing created an interesting and enjoyable context in which to engage in conversations and increase their use of words.

Most parents (n = 12, 75%) reported that the program resources, primarily the books and videos, supported learning and take-home handouts were a valuable addition to weekly sessions providing a reminder of key learning points for home practice. With one exception, the books were positively evaluated for their lack of written content, variety, cultural sensitivity, and colorfulness which offered an enjoyable and entertaining context in which to build a story based on children’s interests. However, five parents (31.25%) considered that the book from the final session was a barrier to child engagement, as it was deficient in color and picture clarity making it difficult to engage them positively with the content. Other challenges for parents included finding the time for home practice due to work and other commitments (n = 1, 6.25%), and the inconvenience to some parents of weekly sessions in the school that did not coincide with start or end of the school day (n = 2, 12.50%).

3.4 Pre-post course results

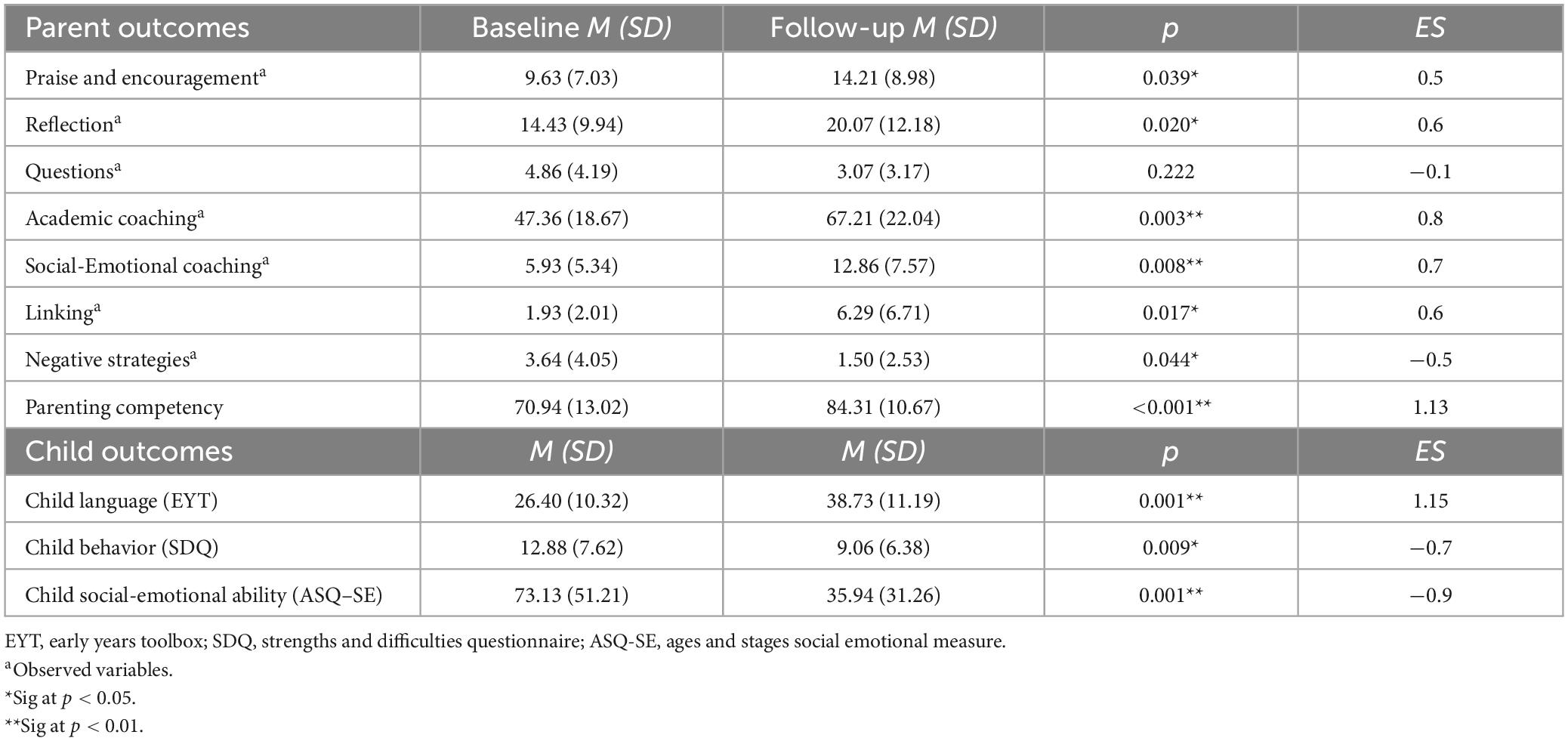

Follow up measures were collected from all 16 parents (100% retention). For the observation outcomes, a Wilcoxon signed-rank non-parametric test showed significant increases in the frequency of use of the positive parenting strategies of praise and encouragement (d = 0.5), reflection (d = 0.6), academic coaching (d = 0.8), social-emotional coaching (d = 0.7), and linking (d = 0.6). There was also a reduction in use of negative parenting strategies (d = 0.5). A paired samples t-test on parental competence showed improved parenting competence and satisfaction (d = 1.12). Children displayed increased expressive language competence (d = 1.15) and had reduced overall behavior problems at follow-up compared to baseline (d = 0.7). Furthermore, children had reduced overall social-emotional difficulties compared to baseline (d = 0.9) (see Table 2).

4 Discussion

This paper reports on the first feasibility study of school-based delivery of the Books Together program for parents of 3–5-year-olds (Murray et al., 2018). It explored feasibility and exploratory outcomes for children and parents.

In terms of feasibility, schools committed staff time for the training, recruitment of parents and for program delivery. They recruited parents of children whom they believed might benefit through direct contact. This approach recruited four parents in each school. Parenting programs do not always reach the families who could most benefit, and collaborative approaches are needed to ensure that families most likely to benefit are recruited (Williams et al., 2020). The results from this trial showed that using a proactive approach, targeting and contacting those whose children were considered most in need, produced successful recruitment of families of children for whom both the school and parents had concerns. Given that parental engagement in children’s education is a key factor in school success (Kingston et al., 2013) establishing how to encourage increased parental involvement, particularly among a group of parents that are least likely to engage with schools is important. Typically, high attrition rates in parenting programs remain a problem (Chacko et al., 2016) but in this study, parent retention was excellent with all 16 parents completing the program with a mean attendance of 6.19 sessions. School staff reported the program as acceptable, enjoyable, and easy to deliver. School staff reported that they would like to continue to deliver the program confirming that it is a feasible and acceptable intervention for school-based delivery. However, some delivery barriers were reported including practical considerations such as timing, lack of school resources to deliver and technical difficulties. This suggests that school procedures and video software may need to be refined to address the practicalities of school-based delivery of the program. Furthermore, school facilitators reported group management challenges. Facilitator training did not include group leadership skills training and no supervision was provided during program delivery. Given the complex needs of the families recruited, group leadership skills training and supervision with a skilled practitioner during program delivery may address the gaps in the skill set required to manage the group setting more effectively (Flay et al., 2005; Falender, 2018). Despite the barriers, the null attrition rate and high parental engagement suggests that the Books Together program may be an acceptable and feasible parenting intervention to positively engage schools, parents, and children.

Similar to other DBS studies, this study reports significant improvements in children’s expressive language, pro-social behavior, and social/emotional competence (Cooper et al., 2015; Murray et al., 2016; Dowdall et al., 2020). The study also reported a significant improvement in observed positive, and a significant reduction in observed negative, parenting strategies and competence. Despite the small sample size the effect sizes ranged from medium to large demonstrating that the magnitude of the result transfers over from being statistically significant to effective in practice in the real world, representing real benefit for children and parents (Aarts et al., 2014). However, the lack of control group suggests that caution should be taken in interpreting the results, particularly given that a recent RCT of the same intervention delivered by children’s center staff found no significant effects for child outcomes (Murray et al., 2023).

4.1 Strengths and limitations

The current study has strengths including the high rates of parental attendance, retention, and program satisfaction as well as the use of a mixed methods approach. However, it also has several limitations including the small sample size and absence of control group. This reduces the generalizability of the findings as well as limiting the interpretation of the findings. Furthermore, since the study had a limited timescale, it was not possible to explore long-term program impact.

5 Conclusion

Despite UK early intervention initiatives children are still arriving at school, and in increasing numbers, without the school readiness skills that will enable them to benefit long term in an educational environment. Schools can identify these children, and do implement interventions for them, however, the home influence is still the strongest predictor of academic outcomes and parent involvement in children’s school life is also impacts on children’s outcomes regardless of child and family characteristics. Delivery of this program to targeted parents as a supportive intervention to help their children in school was successful in recruiting parents of children who benefited from the intervention. The school setting also made delivery easy as the children were on hand for the rehearsal part of the program. Despite the limitations this is the first trial that we are aware of that explores delivery of a DBS program by school based staff to parents of identified high risk school aged children. The preliminary findings are positive and justify a larger, more rigorous RCT trial. The process of delivering to parents during their children’s early school years has several benefits. It builds home-school links, it teaches skills to both parents and school-based staff, school-based staff can encourage parents of children with language and communication needs and the children are accessible for the second half of the session obviating the need for childcare. Therefore, current findings support the need for more rigorous future research to explore the benefits of school-based delivery of the program on parental strategies and wellbeing, and children’s school readiness skills.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Bangor University School of Psychology Ethics Review Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

MW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. CO: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft. JH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by a Knowledge Economy Skills Scholarship 2 (KESS2).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aarts, S., Akker, M. V. D., and Winkens, B. (2014). The importance of effect sizes. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 20, 61–64. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2013.818655

Adams, C., Baxendale, J., Lloyd, J., and Aldred, C. (2005). Pragmatic language impairment: Case studies of social and pragmatic language therapy. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 21, 227–250. doi: 10.1191/0265659005ct290oa

Araujo, L. A., Veloso, C. F., Souza, M. C., Azevedo, C., and Tarro, G. (2021). The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child growth and development: A systematic review. J. Paediatr. 97, 369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2020.08.008

Arnold, D. H., Lonigan, C. J., Whitehurst, G. J., and Epstein, J. N. (1994). Accelerating language development through picture book reading: Replication and extension to a videotape training format. J. Educ. Psychol. 86, 235–243. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.86.2.235

Azmoude, E., Jafarnejade, F., and Mazlom, S. R. (2015). The predictors for maternal self-efficacy in early parenthood. J. Midwifery Reprod. Health 3, 368–376. doi: 10.22038/jmrh.2015.4050

Barcroft, J., Grantham, H., Mauzé, E., Spehar, B., Sommers, M. S., Spehar, C., et al. (2021). Vocabulary acquisition as a by-product of meaning-oriented auditory training for children who are deaf or hard of hearing. Lang. Speech Hear. Servic. Sch. 18, 1049–1060. doi: 10.1044/2021_LSHSS-21-00040

Bercow, J. (2018). Ten years on: An independent review of provision for children and young people with speech, language and communication needs in England. London: ICAN.

Beschorner, B., and Hutchison, A. (2016). Parent education for dialogic reading: Online and face-to-face delivery methods. J. Res. Childh. Educ. 30, 374–388. doi: 10.1080/02568543.2016.1178197

Blom-Hoffman, J., O’Neil-Pirozzi, T., Volpe, R., Cutting, J., and Bissinger, E. (2007). Instructing parents to use dialogic reading strategies with preschool children. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 23, 117–131. doi: 10.1300/J370v23n01_06

Brannon, D., Dauksas, L., Coleman, N., Israelson, L., and Williams, T. (2013). Measuring the effect that the partners’ dialogic reading program has on preschool children’s expressive language. Creat. Educ. 4, 14–17. doi: 10.4236/ce.2013.49B004

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2014). What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well Being 9:26152. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v9.26152

Bridgemohan, R., van Wyk, N., and van Staden, C. (2005). Home-school communication in the early childhood development phase. Education 126, 60–77.

Çakıroğlu, A. (2018). The language acquisition approaches and the development of literacy skills in children. Int. Electron. J. Elementary Educ. 11, 201–206.

Carlton, M. P., and Winsler, A. (1999). School readiness: The need for a paradigm shift. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 28, 338–352. doi: 10.1080/02796015.1999.12085969

Chacko, A., Jensen, S. A., Lowry, L. S., Cornwell, M., Chimklis, A., Chan, E., et al. (2016). Engagement in behavioral parent training: Review of the literature and implications for practice. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 19, 204–215. doi: 10.1007/s10567-016-0205-2

Chow, B. W.-Y., McBride-Chang, C., Cheung, H., and Chow, C. S.-L. (2008). Dialogic reading and morphology training in Chinese children: Effects on language and literacy. Dev. Psychol. 44, 233–244. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.233

Cooper, P. J., Vally, Z., Cooper, H., Radford, T., Sharples, A., Tomlinson, M., et al. (2015). Promoting mother-infant book sharing and infant attention and language development in an impoverished South African population: A pilot study. Early Childh. Educ. J. 42, 143–152. doi: 10.1007/s10643-0591-8

Cristofaro, T. N., and Tamis-LeMonda, C. S. (2012). Mother-child conversations at 36-months and in pre-kindergarten: Relations to children’s school-readiness. J. Early Childh. Literacy 12, 68–97. doi: 10.1177/1468798411416879

Dowdall, N., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Murray, L., Hartford, L., and Cooper, P. J. (2020). Shared picture book reading interventions for child language development: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Dev. 91, e383–e399. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13225

Doyle, B. G., and Bramwell, W. (2006). Promoting emergent literacy and social–emotional learning through dialogic reading. Read. Teach. 59, 554–564. doi: 10.1598/RT.59.6.5

Epstein, J. L. (2010). School/family/community partnerships: Caring for the children we share. Phi Delta Kappan 76, 701–712. doi: 10.1177/003172171009200326

Eun, B. (2010). From learning to development: A sociocultural approach to instruction. Cambrid. J. Educ. 40, 401–418. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2010.526593

Falender, C. A. (2018). Clinical supervision—the missing ingredient. Am. Psychol. 73:1240. doi: 10.1037/amp0000385

Flay, B. R., Biglan, A., Boruch, R. F., Castro, F. G., Gottfredson, D., Kellam, S., et al. (2005). Standards of evidence: Criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prev. Sci. 6, 151–175. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-5553-y

Golinkoff, R. M., Hoff, E., Rowe, M. L., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., and Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2019). Language matters: Denying the existence of the 30-million-word gap has serious consequences. Child Dev. 90, 985–992. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13128

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 38, 581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Howard, S. J., and Melhuish, E. (2016). An early years toolbox for assessing early executive function, language, self-regulation, and social development: Validity, reliability, and preliminary norms. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 35, 255–275. doi: 10.1177/0734282916633009

Hutchings, J., Pye, K. L., Bywater, T., and Williams, M. E. (2020). A feasibility evaluation of the Incredible Years® school readiness parenting programme. Psychosoc. Interv. 29, 83–91. doi: 10.5093/pi2020a2

Johnstone, C., and Mash, E. J. (1989). A Measure of Parenting Satisfaction and Efficacy. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 18, 167–175. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp1802_8

Jones, D. E., Greenberg, M., and Crowley, M. (2015). Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. Am. J. Public Health 105, 2283–2290. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2015.302630

Kingston, S., Huang, K. Y., Calzada, E., Dawson-McClure, S., and Brotman, L. (2013). Parent involvement in education as a moderator of family and neighbourhood socioeconomic context on school readiness among young children. J. Commun. Psychol. 41, 265–276. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21528

Knauer, H. A., Jakiela, P., Ozier, O., Aboud, F., and Fernald, C. H. (2019). Enhancing young children’s language through parent-child book-sharing: A randomised trial in rural Kenya. Policy Research Working Paper No. 8733. World Bank Group. Available online at: https://www.edu-links.org/sites/default/files/media/file/World%20Bank%20ParentChild%20Book%20Sharing.pdf (accessed September 18, 2023).

Mol, S. E., Bus, A. G., and De Jong, M. T. (2009). Interactive book reading in early education: A tool to stimulate print knowledge as well as oral language. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 979–1007. doi: 10.3102/0034654309332561

Murray, L., De Pascalis, L., Tomlinson, M., Vally, Z., Dadomo, H., MacLachlan, B., et al. (2016). Randomised control trial of a book-sharing intervention in a deprived South African community: Effects on carer-infant interactions, and their relation to infant socioemotional outcome. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 57, 1370–1379. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12605

Murray, L., Jennings, S., Mortimer, A., Prout, A., Melhuish, E., Hughes, C., et al. (2018). The impact of early-years provision in Children’s Centres (EPICC) on child cognitive and socio-emotional development: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 19:450. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2700-x

Murray, L., Jennings, S., Perry, H., Andrews, M., De Wilde, K., Newell, A., et al. (2023). Effects of training parents in dialogic book-sharing: The Early-Years Provision in Children’s Centers (EPICC) study. Early Childh. Res. Q. 62, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2022.07.008

Ninio, A. (1983). Joint book reading as a multiple vocabulary acquisition device. Dev. Psychol. 19, 445–451. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.19.3.445

Ofsted (2014). The pupil premium: An update. Available online at: http://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-pupil-premium-an-update (accessed July 5, 2023).

Ohan, J. L., Leung, D. W., and Johnston, C. (2000). The Parenting Sense of Competence scale: Evidence of a stable factor structure and validity. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 32, 251–261. doi: 10.1037/hoo87122

Opel, R., Ameer, S. S., and Aboud, M. E. (2009). The effect of preschool dialogic reading on vocabulary among rural Bangladeshi children. Int. J. Educ. Res. 48, 12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2009.02.008

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Pianta, R. C., and Cox, M. J. (2000). Teachers’ judgments of problems in the transition to kindergarten. Early Childh. Res. Q. 15, 147–166. doi: 10.1016/s0885-2006(00)00049-1

Robinson, E. A., and Eyberg, S. M. (1981). The dyadic parent-child interaction coding system: Standardisation and validation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 49, 245–250. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.49.2.245

Scott, A., McNeill, B., and Van-Bysterveldt, A. (2020). Teenage mothers’ language use during shared reading: An examination of quantity and quality. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 36, 59–74. doi: 10.1177/0265659020903769

Sheppard, A. (2009). School attendance and attainment: Poor attender’s perceptions of schoolwork and parental involvement in their education. Br. J. Special Educ. 36, 104–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8578.2009.00413.x

Skreden, M., Skari, H., Malt, U. F., Pripp, A. H., Björk, M. D., Faugli, A., et al. (2012). Parenting stress and emotional wellbeing in mothers and fathers of preschool children. Scand. J. Public Health 40, 596–604. doi: 10.1177/1403494812460347

Slot, P. L., and von Suchodoletz, A. (2018). Bidirectionality in preschool children’s executive functions and language skills: Is one developing skill the better predictor of the other? Early Childh. Res. Q. 42, 205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.10

Squires, J., Bricker, D., Heo, K., and Trombly, E. (2001). Identification of social-emotional problems in young children using a parent-completed screening measure. Early Childh. Res. Q. 16, 405–419. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(01)00115-6

Stone, L., Otton, R., Rutger, C. M., Engels, E., Vermulst, A., and Janssens, J. (2010). Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire for 4- to 12-year-olds: A review. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 13, 254–274. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0071-2

Towson, J. A., Gallagher, P. A., and Bingham, G. E. (2016). Dialogic reading: Language and preliteracy outcomes for young children with disabilities. J. Early Interv. 38, 230–246. doi: 10.1177/1053815116668643

Valdez-Menchaca, M. C., and Whitehurst, G. J. (1992). Accelerating language development through picture book reading: A systematic extension to Mexican day care. Dev. Psychol. 28, 1106–1114. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.28.6.1106

Vally, Z., Murray, L., Tomlinson, M., and Cooper, P. J. (2015). The impact of dialogic book-sharing training on infant language and attention: A randomized controlled trial in a deprived South African community. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 56, 865–873. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12352

Van Kleeck, A. (2014). Distinguishing between casual talk and academic talk beginning in the preschool years: An important consideration for speech-language pathologists. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 23, 724–741. doi: 10.1044/2014_AJSLP-14-0032

Vernon-Feagans, L., Bratsch-Hines, M., Reynolds, E., and Willoughby, M. (2020). How early maternal language input varies by race and education and predicts later child language. Child Dev. 91, 1098–1115. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13281

Weisleder, A., Mazzuchelli, D., Lopez, A. S., Neto, W. D., Cates, C. B., Gonclaves, H. A., et al. (2018). Reading aloud and child development: A cluster-randomized trial in Brazil. Pediatrics 141:e20170723. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0723

Welsh, J. A., Bierman, K. L., and Mathis, E. T. (2014). “Parenting programs that promote school readiness,” in Promoting school readiness and early learning: The implications of developmental research for practice, eds M. Boivin and K. Bierman (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 253–278.

Whitehurst, G., Arnold, D., Epstein, J., Angell, A., Smith, M., and Fischel, J. (1994). A picture book reading intervention in day care and home for children from low-income families. Dev. Psychol. 30, 679–689. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.30.5.679

Wilder, S. (2014). Effects of parental involvement on academic achievement: A meta-synthesis. Educ. Rev. 66, 377–397. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2013.780009

Williams, M. E., Hoare, Z., Owen, D. A., and Hutchings, J. (2020). Feasibility study of the enhancing parenting skills programme. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 29, 686–698. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01581-8

Wolf, S., and McCoy, D. C. (2019). The role of executive function and social-emotional skills in the development of literacy and numeracy during preschool: A cross-lagged longitudinal study. Dev. Sci. 22:e12800. doi: 10.1111/desc.12800

YouGov (2020). Kindred 2 – School Readiness. The Report of the Independent Review on School Readiness Outcomes following COVID-19. Available online at: https://kindredsquared.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Kindred2-YouGov-School-Readiness.pdf (accessed July 27, 2023).

YouGov (2022). School readiness: Qualitative and quantitative research with teaching professionals. London: Kindred2.

Keywords: dialogic book sharing, parent-child interactions, language, social/emotional ability, parent training

Citation: Williams ME, Owen C and Hutchings J (2024) School-based delivery of a dialogic book sharing intervention: a feasibility study of Books Together. Front. Educ. 9:1304386. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1304386

Received: 29 September 2023; Accepted: 14 February 2024;

Published: 28 February 2024.

Edited by:

Douglas F. Kauffman, Medical University of the Americas – Nevis, United StatesReviewed by:

Roxanne Hudson, University of Washington, United StatesAydin Durgunoglu, University of Minnesota Duluth, United States

Copyright © 2024 Williams, Owen and Hutchings. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Margiad E. Williams, bWFyZ2lhZC53aWxsaWFtc0BiYW5nb3IuYWMudWs=

Margiad E. Williams

Margiad E. Williams Claire Owen

Claire Owen Judy Hutchings

Judy Hutchings