- Department of Language &Translation, Faculty of Art & Humanities, Taibah University, Madinah, Saudi Arabia

Integrating 21st century skills, including communication, collaboration, problem-solving, and critical thinking, into English as a Foreign Language (EFL) university courses is imperative. This study adopts a tripartite focus: (1) investigating cross-cultural EFL instructors’ perspectives on challenges linked to infusing 21st century skills into Saudi EFL university courses; (2) identifying contributory factors underpinning these challenges; and (3) elucidating proposed strategies for embedding 21st century skills in selected Saudi EFL university classrooms. Using narrative inquiry as a research method, empirical data was garnered through semi-structured interviews involving thirty EFL instructors representing mixed-gender and eight nationalities across multiple Saudi universities. The findings underscore instructors’ affirmative disposition towards incorporating 21st century skills in EFL classes, despite entrenched academic, institutional, collegial, and student-centered obstacles. Furthermore, the findings spotlight diverse factors exacerbating these challenges, encompassing technological underpinning, temporal constraints, and the absence of robust assessment frameworks, dwindling student engagement, conventional pedagogic paradigms, and administrative complexities. Addressing these challenges necessitates a comprehensive approach characterized by faculty development, curricular realignment, seamless technology integration, collaborative learning ecosystems, student-centric pedagogies, and judicious evaluation mechanisms. Through adopting this holistic approach, educational stakeholders can effectively surmount the intricacies linked with 21st century skill integration, fostering an enriched educational milieu aligned with evolving global imperatives.

1 Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of 21st century education, the imperative is to equip students with the skills necessary for success in a world characterized by constant change and information abundance (Bharathi, 2011). According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), these skills are pivotal in transforming students into versatile learners capable of adapting to the dynamic 21st century environment (Chun and Abdullah, 2022). As nations across the globe strive to enhance their educational systems, there is a growing emphasis on skill-based learning as a means to cultivate human capital and foster knowledge societies (Alhothali, 2021). However, the integration of 21st century skills into educational practices is not without its challenges. Instructors’ approaches and perspectives may vary due to differences in pedagogical beliefs, sociocultural contexts, and institutional norms. Gaining insights from instructors representing diverse cultural backgrounds can offer a broader understanding of the obstacles and opportunities associated with integrating these skills (Alqahtani, 2020). The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) recognizes the significance of equipping all learners with 21st century skills, as evidenced by its inclusion in the national development plan, the Saudi Vision 2030, which underscores the importance of providing children with the knowledge and skills needed for future employment (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2016). In the realm of English Language Teaching (ELT), the traditional focus on memorization and rote learning no longer aligns with the demands of the 21st century (Handayani, 2017). Instead, today’s EFL classrooms should be spaces where students can apply language and cultural knowledge to global communication (Eaton, 2010). Given the challenges of our evolving society, the quality of education becomes increasingly vital, necessitating adaptability in our school systems. Teachers play a pivotal role in connecting learning to real-life experiences and equipping students with the skills required for success (Nwagwu et al., 2021). The role of the teacher has evolved into one of leadership, guidance, and counselling, moving beyond the mere transfer of information (Alhothali, 2021). In the realm of ELT, the goals have shifted from merely improving language proficiency to instilling a sense of social responsibility in students (Erdoğan, 2019). Fandiño Parra (2013) emphasizes that teaching the English language in the 21st century demands the cultivation of global connections, creativity, self-direction, critical thinking, collaboration, and communication skills. The lack of 21st century skills among young people in Saudi Arabia and beyond raises concerns about their employability in both domestic and international job markets (Alghamdi, 2022). Thus, understanding the challenges faced by cross-cultural English instructors in integrating these skills is paramount. This study aims to shed light on these challenges, contributing to a deeper understanding of the perspectives and difficulties encountered by cross-cultural EFL instructors in Saudi EFL university courses. The findings and recommendations of this research hold relevance for university administrators, policymakers, cross-cultural EFL instructors, researchers, and educators. To the best of the researcher’s knowledge, no prior studies have explored the integration of 21st century skills from the perspectives of cross-cultural English instructors. This study employs semi-structured interviews to elicit participants’ views and gain insights into their cross-cultural perspectives on the integration of these skills into EFL courses. Given the significant changes and improvements underway in KSA, driven by its strategic goal, the Saudi Vision 2030, there is a pressing need for individuals equipped with 21st century skills to compete effectively both domestically and globally (Bolat, 2022). As such, the integration of these skills into the curriculum, with instructors playing a pivotal role, is of paramount importance, particularly in the field of ELT, where proficiency in English and 21st century skills are increasingly intertwined (Warschauer, 2000). The aims of this study are threefold: (1) to investigate cross-cultural EFL instructors’ perspectives on challenges related to integrating 21st century skills into Saudi EFL university courses; (2) to identify the factors underpinning these challenges; and (3) to elucidate proposed strategies for embedding 21st century skills in selected Saudi EFL university classrooms.

2 Literature review

This comprehensive literature review embarks on a critical exploration of 21st century education. It delves into the multifaceted challenges faced by cross-cultural university instructors, dissects the core components that constitute 21st century skills, and elucidates the theoretical framework underpinning this study. The review also presents diverse definitions of 21st century skills, underscoring the paramount importance of equipping students with core competencies such as critical thinking, problem-solving, communication, and digital literacy.

Being a culturally competent instructional designer necessitates an acute awareness of the interplay between learners’ cultural backgrounds and learning processes. It also involves the capacity to effectively develop instructional materials that cater to the diverse needs of students from various cultural backgrounds, ultimately leading to enhanced accessibility and a greater likelihood of success for all learners (Wang, 2007).

The term “cross-cultural” highlights the instructor’s proficiency in navigating and bridging cultural differences within the classroom. This competency is vital for promoting effective communication and enriching learning experiences for students from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. It may entail integrating culturally relevant content, adapting teaching methodologies to accommodate varied learning styles, and fostering an inclusive and respectful learning environment (Byram, 2008; Guilherme, 2015).

2.1 Defining 21st century skills

The foundation of our exploration lies in the definition of 21st century skills, which constitute the cornerstone of modern education. Rich (2010) succinctly encapsulates these skills as “certain core competencies such as collaboration, digital literacy, critical thinking, and problem-solving that advocate believing schools need to teach to help students thrive in today’s world.” The holistic nature of 21st century skills is aptly categorized into four domains, each weaving a tapestry of essential capabilities:

1. Ways of thinking: Creativity, critical thinking, problem-solving, decision-making, learning, and innovation.

2. Ways of working: Communication and collaboration.

3. Tools for working: Information and communications technology (ICT) and information literacy.

4. Living in the world: Citizenship, life and career, and personal and social responsibility (Rich, 2010).

Ananiadou and Claro (2009) further refine this definition, asserting that 21st century skills are indispensable for young individuals to function effectively as workers and citizens in the knowledge society of the 21st century. This elaboration emphasizes these skills’ practicality and real-world applicability in equipping individuals to navigate the complexities of contemporary life. Therefore, the 21st century skills in the current study encompass collaboration, critical thinking, communication, and problem-solving, which are crucial for students to excel in their careers.

2.2 Origins and widening adoption of 21st century skills

The genesis of the 21st century skills paradigm is rooted in the United States in the early 21st century, fueled by the need to adapt to the changing demands of the labour market and enhance educational outcomes for the current generations (Pardede, 2020). Various frameworks for 21st century skills have emerged, reflecting the dynamic needs of the labour market. Notably, the framework designed by the Partnership for 21st Century Learning (P21) (2007) has achieved widespread recognition and adoption across educational institutions and various job sectors (Alghamdi, 2022). This comprehensive framework provides an all-encompassing blueprint for nurturing and assessing 21st century skills.

In a world characterized by rapid and pervasive changes affecting all aspects of life, it is imperative for students to be equipped with a diverse set of skills. These include critical thinkers, problem solvers, innovators, effective communicators, self-directed learners, information and media literate, globally aware, civically engaged, financially, and economically literate (Ashraf et al., 2017). The Partnership’s delineation of these qualities forms the foundation of 21st century education.

The connection between 21st century skills and teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFL) is found in the integration of skills such as critical thinking, communication, collaboration, creativity, and digital literacy into the language learning process. EFL educators can leverage these skills to enhance students’ language proficiency and prepare them for the demands of the modern world. Activities that promote collaborative language projects, digital storytelling, and problem-solving exercises can simultaneously foster language development and 21st century skills in EFL learners (Warschauer, 2007; Benson and O’Dowd, 2014; Lamb and Hipps, 2015; Goh and Parker, 2017; Zheng and Sun, 2019).

2.3 Challenges in integrating 21st century skills into education

The integration of 21st century skills into the educational process presents educators with formidable challenges. These challenges encompass a multifaceted spectrum, demanding the infusion of innovative pedagogical approaches and the cultivation of adaptable curricula. Educators must navigate these challenges adeptly, ensuring that students graduate with the competencies demanded by the 21st century world. Undoubtedly, educators stand as the linchpin in the endeavour to impart 21st century skills to students. As echoed by Nwagwu et al. (2021), the pivotal role of teachers in shaping the educational landscape cannot be overstated. To this end, teacher quality, social status, and competence assume paramount significance (Nwagwu et al., 2021). Griffin and Care (2015) accentuate that teachers’ understanding of the diversity in students’ 21st century skills can be informed by their observations of students when engaged in both online and classroom-based tasks. The essence of allowing students to take more responsibility for their learning, fostering self-directed learning, and inculcating 21st century skills poses a formidable challenge. This challenge is magnified by students’ varying levels of engagement and focus, necessitating teachers with robust classroom management skills and the ability to foster a positive classroom culture (Abu Bakar et al., 2019).

The integration of 21st century skills into education is not a one-size-fits-all endeavour. The educational landscape is fraught with diversity, encompassing varying cultural contexts, pedagogical beliefs, and institutional norms. Consequently, the challenges faced by educators in integrating 21st century skills may differ significantly based on these contextual factors. While navigating this terrain, it becomes apparent that educators must not only grapple with the challenges posed by the skills themselves but also address the intricate interplay of societal, cultural, and institutional factors that shape their teaching practices. The need to tailor educational approaches to specific contexts and demographics adds layers of complexity to the integration process. The challenges of integrating 21st century skills into education are further magnified in cross-cultural contexts. Educators traversing diverse cultural backgrounds encounter a distinct set of difficulties and opportunities. These cross-cultural perspectives bring to the fore the subtle nuances and intricacies of the integration process. Saudi Arabia, with its unique cultural and educational landscape, serves as an illustrative case study. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has embarked on an ambitious journey to equip all learners with 21st century skills, as evidenced by its Vision 2030 plan, which underscores the importance of providing children with the knowledge and skills needed for future employment (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2016). In this multifaceted cultural milieu, the integration of 21st century skills takes on a distinctive character, shaped by the confluence of cultural values, societal norms, and educational imperatives.

Numerous studies underscore the profound impact of teachers’ attitudes and competencies on the successful integration of 21st century skills into education (Alamri, 2020). For instance, Alzuoud and Gaudel (2020) conducted a study to explore teachers’ perspectives on the integration of core skills such as problem-solving, thinking, communication, and language skills into English language teaching in Saudi universities. Their findings revealed the intricate relationship between language and core skills, emphasizing the need for teacher training courses and modifications in examination systems to evaluate both sets of skills. Likewise, Bharathi (2011) investigated teachers’ opinions about their undergraduate students’ writing performance in India, highlighting the need to redesign the existing curriculum of teaching English to develop students’ key competencies and skills to cope with the requirements of the employability market. A recent study by Chun and Abdullah (2022) delved into the effects of language teachers’ attitudes, barriers, and enablers in teaching 21st century skills at Chinese vernacular schools. This mixed-method study, which encompassed questionnaires and semi-structured interviews, unveiled a complex web of challenges. These included inadequate guidelines, time constraints, students’ interest, teachers’ passion, and insufficient knowledge of pedagogical methods. A quantitative study by Tsourapa (2018) further elucidated teachers’ attitudes towards developing 21st century skills in the EFL class. This study, which surveyed 121 teachers in Greece, revealed the positive inclinations of teachers towards developing these skills. However, it also underscored the existence of formidable barriers, including a lack of training or technological equipment, time pressure, course material overload, and constraints imposed by school policies.

The integration of 21st century skills into EFL classes is fraught with a myriad of contextual challenges and barriers. These challenges manifest in various forms, including curriculum deficiencies, material shortages, inadequate infrastructure, and unsupportive administrative attitudes (Bolat, 2022). The study conducted by Blot (2022) specifically explored the challenges teachers face while applying 21st century skills in English language classes. It further probed the extent to which English language teachers use these skills in their classes. The findings revealed a host of challenges, including a lack of qualified pre-and in-service training, insufficient curriculum, a shortage of materials and infrastructure, and unsupportive attitudes of administrators.

The obstacles to integrating 21st century skills into EFL classes have been a focal point of numerous studies. For instance, Bedir (2019) examined the beliefs and perceptions of EFL pre-service teachers regarding 21st century learning and innovation skills, with a special emphasis on the 4Cs. The findings, gleaned from semi-structured interviews and questionnaires, unveiled mixed attitudes. While pre-service teachers held negative beliefs about the emphasis on 21st century skills in the national curriculum and assessment, they exhibited positive beliefs regarding professional development for these skills. In a complementary study, Baran-Łucarz and Klimas (2020) delved into EFL student teachers’ opinions, beliefs, and self-awareness concerning the development of 21st century skills in English classes. Their questionnaire-based study, involving 53 participants, unearthed intriguing insights. The majority of participants possessed limited knowledge of 21st century skills, although they were generally supportive of their incorporation into English classes. This highlighted the pressing need to enhance foreign language teachers’ awareness of implementing these skills in the classroom.

Amidst these challenges, educators and researchers have strived to identify strategies to overcome the hurdles associated with integrating 21st century skills into education. Alamri (2020) explored Saudi EFL female students’ perceptions of their teachers’ usage of 21st century skills and their impact on improving their language skills. The findings underscored the importance of teachers’ professional development programs, ensuring they can incorporate 21st century abilities into the teaching-learning process. Furthermore, language instructors should be willing and prepared to incorporate these skills into learner-centered materials that encourage innovation and interactivity. Alhothali (2021) conducted a study that delved into the global perspective of adding 21st century skills to teacher preparation programs, as well as the feasibility of including these abilities in these programs. The research, adopting an analytical-descriptive approach and utilizing a questionnaire, involved a sample of 50 in-service teachers in Saudi Arabia. The study concluded that in-service teacher preparation, guided by 21st century skills, is an indispensable educational goal for teacher development. This resonates with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, which underscores the importance of developing new curricula grounded in basic skills related to the 21st century. Handayani (2017) emphasized the role of English instructors in the 21st century, asserting that they should “develop their competences by being literate in ICT, and attending some educational trainings and workshops” (p. 163). These studies collectively underscore the pressing need for research that examines cross-cultural perspectives of EFL instructors on the challenges encountered in integrating 21st century skills into Saudi EFL courses, the factors contributing to these challenges, and the proposed strategies to overcome them.

Driven by the complex and dynamic educational landscape, the present study embarked on a quest to understand the lived experiences of cross-cultural EFL instructors in Saudi Arabia using narrative inquiry. Three questions guided the researcher’s path:

1. What challenges do cross-cultural EFL instructors encounter in integrating 21st century skills into Saudi EFL courses?

2. What factors underpin the challenges encountered by cross-cultural EFL instructors in integrating 21st century skills into Saudi EFL courses?

3. What strategies do cross-cultural EFL instructors propose to overcome the encountered challenges?

By delving into these questions, this research aspires to illuminate the intricacies and opportunities associated with the integration of 21st century skills into Saudi EFL education. The insights gleaned will serve to inform pedagogical practices and shape educational policies, fostering a more nuanced understanding of the cross-cultural dynamics that underlie this transformative educational journey.

3 Materials and methods

This section outlines the research design, theoretical framework, sampling strategy, data collection methods, data analysis techniques, and ethical considerations. The research design guides the process of data collection and analysis. The sampling, data collection, and analysis methods ensure a rigorous study. Moreover, ethical considerations safeguard the participants’ rights and well-being.

3.1 Research design

Narrative inquiry is a valuable tool for understanding individual and communal experiences, especially when investigating subjective meaning-making processes (Lieblich et al., 2008). This is consistent with the purpose of the current study delving into the lived experiences of EFL instructors’ incorporating 21st century skills in Saudi institutions. Narrative inquiry looks beyond surface descriptions to reveal the deeper narratives that shape people’s lives and actions (Riessman, 2008). Listening to EFL instructors’ stories gives us deeper insights into the problems, motives, and complications they face while incorporating 21st century skills. It emphasizes inductive analysis, allowing themes and patterns to emerge directly from the instructors’ voices (Creswell and Poth, 2016). This method promotes a more sophisticated understanding of their distinct viewpoints and the context of Saudi universities. As a result, this study uses a qualitative narrative inquiry method. It enables the researcher to investigate the problems and experiences of EFL instructors in their own words, reflecting the depth and complexities of their integration 21st century skills within the context of Saudi universities.

3.2 Theoretical framework

The orientation of the 21st century educational paradigm has a knowledgeable and multi-skilled individual. Therefore, this study adopted the developed framework from the Partnerships for 21st Century Skills (P21) as a theoretical framework (see Figure 1). It includes general kinds of skills. The first skills in this framework are learning and innovation, known as the 4Cs and focus on Collaboration, Critical thinking, Creativity, and Communication. The second kind is digital literacy skills, which focus on information and communications technology, media, and information literacy. The last kind of these skills is life literacy skills focusing on initiative and self-direction, flexibility and adaptability, social and cross-cultural interaction, leadership and responsibility, and productivity and accountability (Van Laar et al., 2017). “Students must fulfil these skills to help them understand ways of thinking, working, media for working, and methods for living together in this world” (Menggo et al., 2022, p. 169).

3.3 Data collection

The form of interview used in the current study was a semi-structured interview due to its flexibility in allowing the researcher to include, modify and delete questions and items according to what information is related. Semi-structured interviews can be used for “exploring issues, personal biographies and what is meaningful to, or valued by participants, how they feel about particular issues, how they look at particular issues, their attitudes, opinions and emotions” (Newby, 2010, pp. 243–244). The current study used a semi-structured interview to gain comprehensive information about the challenges of integrating 21st century skills into EFL classes from the EFL instructors’ perspectives in Saudi universities and unlock the doors to these personal narratives. The semi-structured interview questions were administered to seven jury members (3 males and 4 females) in the English department at different Saudi universities to provide their comments and feedback. The jury members provided feedback and suggestions that focused on removing, adding, and changing the interview questions and the language for clarity and simplicity. Accordingly, the interview questions were modified. The semi-structured interview consisted of eleven questions (See Appendix A). Each interview lasted approximately 20–30 min. To maintain consistency and mitigate potential biases, the same interviewer conducted all the interviews. During the interviews, open-ended questions were used to encourage participants to express their views and experiences freely. Additionally, probing questions were employed to delve deeper into specific topics and challenges. Throughout the interviews, field notes were taken to document non-verbal cues and contextual information. Any challenges encountered during the interviews, such as technical issues or participant discomfort, were addressed promptly to ensure the quality and integrity of the data collection process. After each interview, the recordings were transcribed, converting them into raw materials for narrative tapestry.

3.4 Data analysis

The data from the semi-structured interview was constructed inductively by building categories and themes from the bottom up (Creswell, 2013). This process was guided by Creswell’s (2007) procedures in qualitative data analysis that “consists of preparing and organising the data (i.e., text data as in transcripts, or image data as in photographs) for analysis, then reducing the data into themes through a process of coding and condensing codes, and finally representing the data in figures, tables, or a discussion” (p. 148). This type of analysis requires the researcher to get involved in different research stages. It includes switching back and forth between the original data and the coding process to produce new codes and validate current ones against the original data. Consequently, the data became more organised and accessible.

3.5 Participants

To ensure rich and diverse narratives, participants were selected through purposive sampling. Purposive sampling is utilized to access people’s knowledge about issues based on their professional role, power, access to networks, or expertise (Ball, 1990, cited in Cohen et al., 2011, p. 157). It facilitates the collection of comprehensive data from individuals in their natural settings (Yin, 2014). Each participant brings a unique perspective, weaving threads of cultural backgrounds and teaching philosophies into the overall narrative.

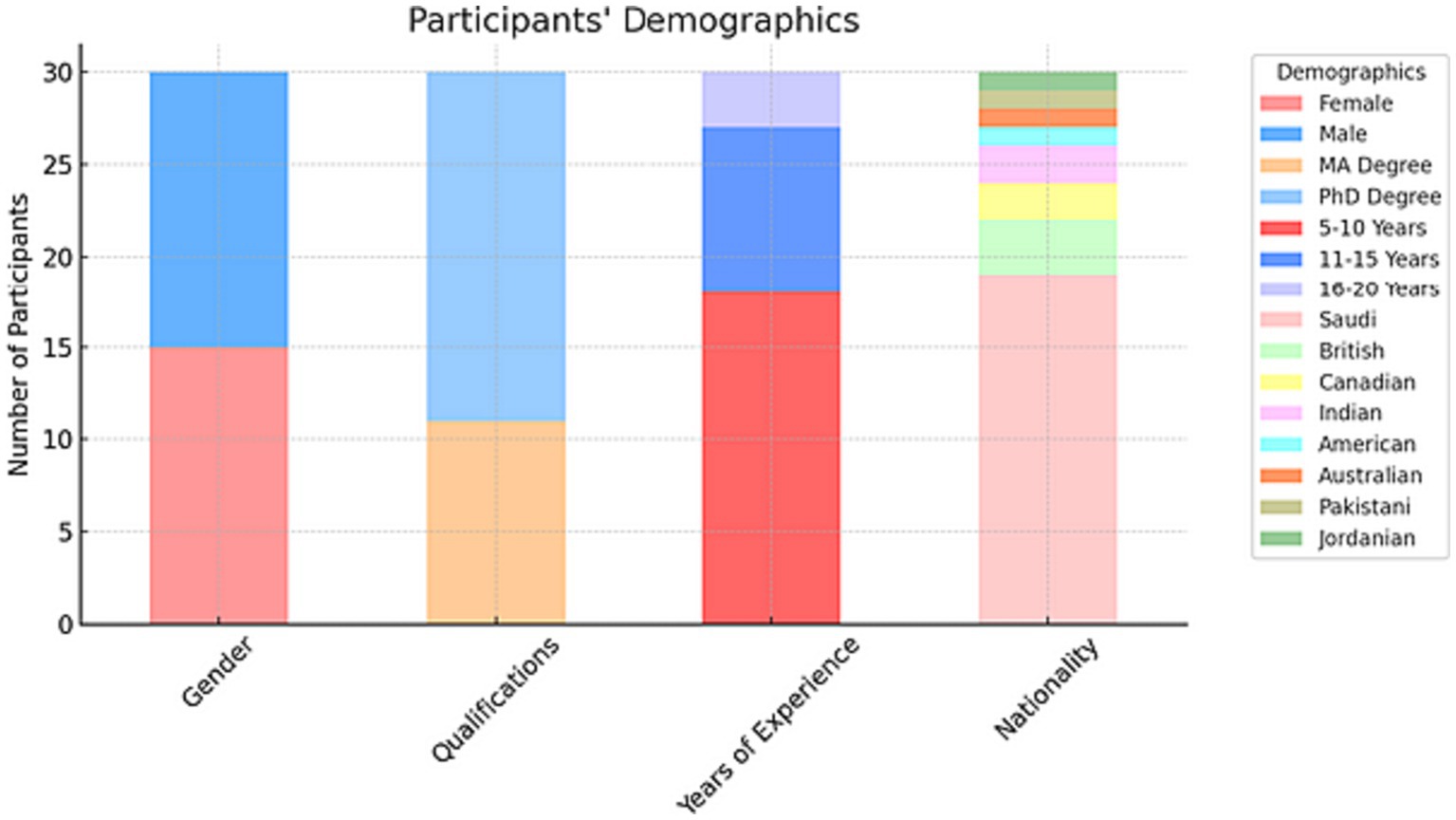

Thirty EFL university instructors working at various Saudi universities participated in the present study (15 females and 15 males). These instructors have varied teaching experience in teaching EFL (18 participants with 5–10 years of experience, 9 participants with 11–15 years of experience, and 3 participants with 10–20 years of experience). Regarding qualifications, 11 participants held an MA degree, and 19 held a PhD degree. The sample participants were multi-national EFL teachers (Nineteen Saudis, three British, two Canadians, two Indians, one American, one Australian, one Pakistani, and one Jordanian). Figure 2 shows the participants’ demographics.

3.6 Ethical considerations

To obtain an accurate description of the central phenomena in a qualitative study, the researcher needs to create a trustworthy connection with each participant (Creswell, 2012). Participants’ confidence and identity was maintained throughout the study (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). Therefore, all the necessary steps were taken to preserve the participants’ physical, psychological, and emotional well-being. Before participating in the study, participants were given a written consent form to sign before the research began voluntarily [British Educational Research Association (BERA), 2018] (See Appendix B). The researcher informed the participants of confidentiality, anonymity, and privacy [British Educational Research Association (BERA), 2018]. Pseudonyms were utilized to keep participants anonymised in the study.

Embracing the narrative inquiry method sets the tone for the study findings, guiding readers on an immersive journey through the lived experiences of cross-cultural EFL instructors in Saudi Arabia. It highlights the human dimension of research, highlighting the voices and experiences that inform study findings.

4 Findings

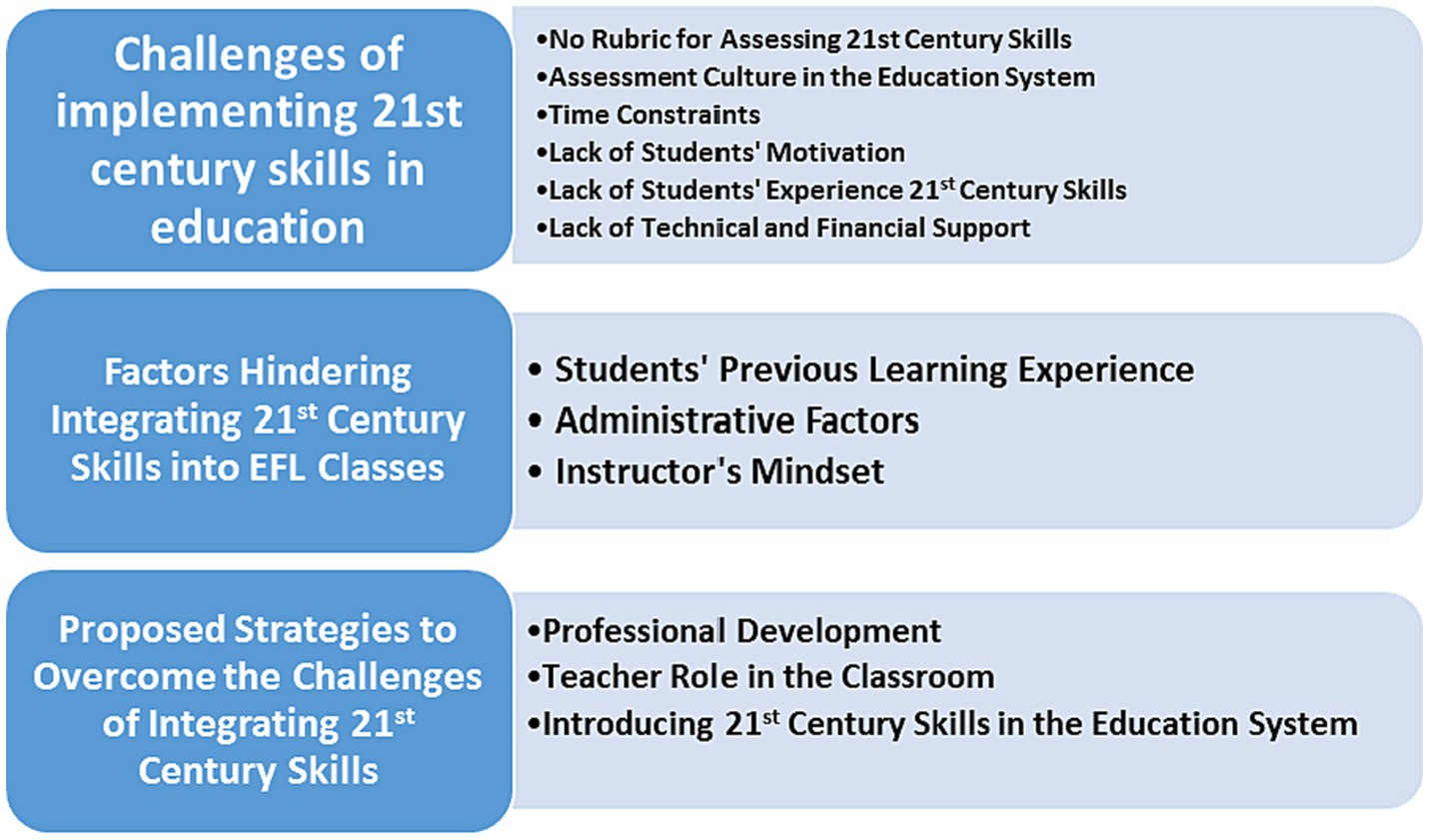

This section reports the findings of the challenges of implementing 21st century skills in education, factors hindering their integration, and proposed strategies for effective incorporation into teaching and learning processes. Figure 3 shows the themes and sub-themes of integrating 21st Century skills into EFL university courses.

4.1 Challenges of implementing 21st century skills

This section systematically explores the obstacles encountered in embedding 21st century skills into educational curriculums, with insights from various educators.

4.1.1 No rubric for assessing 21st century skills

The fundamental challenge of assessment is the lack of a rubric to assess 21st century skills. Participants’ observations underscore the absence of a standard rubric, illustrating the difficulty in both assessing and incorporating these skills into the educational framework. Dr. Ahmed’s statement encapsulates this issue:

"The difficulty is that we do not have a clear rubric or emphasis on employing these. We do not know how to assess these or how to include them. So, it is an individual effort; each doctor or instructor does it according to her definition. But there's now emphasis or a unified rubric to follow, to at least have it in the syllabus." (M1)

Dr. Mohamed further elaborates:

"Assessment is a difficult game, but then we must consider how to assess these skills. We must find ways to assess it. We are worried that when we assess these things, normally, we tend to ignore the content that everybody thinks is the most important part." (M2)

4.1.2 Assessment culture in the education system

The current test-driven system, focused on quantifiable outcomes, neglects the importance of 21st century skills like communication and creativity. This is reflected in the prevailing assessment culture in education, as described by Ali, Dr. Amal, and Mr. Ahmed.

Ali discusses the challenge posed by the current assessment culture:

"The system's culture is a test-driven system that values whatever is quantifiable, showing clearly that students have achieved it. So, how will I prove to them that students are good at communication or creativity? So, the system does not value formative assessment; they only value summative assessment." (M3)

Dr. Amal echoes this perspective:

"Another challenge is that the system itself is product-oriented. It is not process-oriented. As I said, students value the scores. I believe these soft and 21st century skills are not easy to test. They are not easy to provide in the system that those students have achieved or progressed." (F1)

Mr. Ahmed reiterates similar concerns:

"The culture of the education system itself is a test-driven system that values whatever is quantifiable, whatever is shown clearly that students have achieved. So, how will I prove to them that students are good at communication or creativity? So, the system does not value formative assessment; they only value summative assessment." (M1).

4.1.3 Time constraints

Another critical factor impacting the implementation of these skills is time constraints. Dr. Mona, Mr. John, and Dr. Maha’s experiences reveal the challenge of balancing course material with the integration of 21st century skills, highlighting how time limitations affect the depth and quality of skill incorporation.

Dr. Mona addresses the issue of time:

"Time is a challenge, especially with the trimester system. It cannot be easy to integrate all I want to integrate and follow the coursebook and textbooks simultaneously." (F2)

Mr. John’s experience aligns with this:

"Sometimes time is limiting me. Our lectures are 50 minutes long; sometimes, we only see students three to five times a week. So, we barely covered the materials and integrated the 21st skills. So, time is a challenge for me." (M4)

Dr. Maha adds:

"I always felt that we were 'over-taught.' By this, I mean students spend too much time in the classroom (5 hours a day) and not enough time doing their work. They, therefore, became reliant on the teacher and were passive learners." (F3)

4.1.4 Lack of students’ motivation

Another challenge relates to the lack of students’ motivation, as reflected in the experiences of Mr. Yasir, Dr. Huda, and Mr. Mohammed. This section shows how a lack of motivation and fear of making mistakes can hinder the adoption of new skills.

Mr. Yasir reflects on student motivation:

"For me, as an English instructor, it discourages me from going out of my way and spending extra time outside of the university, outside of my work hours, to come up with an exercise to see students not particularly interested in the exercise or activity that would focus on their critical thinking skills or collaboration. So, that is the unfortunate reality." (M5)

Dr. Huda points out the challenge of participation:

"Some students may be less motivated and more passive learners. Getting them to participate and bring the same energy as everyone else cannot be easy." (F4)

Mr. Mohammed highlights the fear factor:

"Students are often terrified of errors regardless of how often I assure them that the classroom is a trial-and-error zone. This can be challenging as it will hinder them from participating in the previously mentioned activities." (M6)

4.1.5 Lack of students’ experience 21st century skills

Students’ unfamiliarity with 21st century skills suggests that the absence of a clear understanding of these skills leads to resistance and a lack of interest among students.

Dr. Ibrahim notes:

"I think that is the biggest challenge, not knowing what it looks like to be creative, critical, or work collaboratively. So, I think that is the biggest challenge, not knowing and therefore having some resistance. Students do not want to do it because they do not know how." (M7)

Ms. Huda observes a similar issue:

"One of the challenges of integrating 21st century skills is whether students know or are familiar with these skills. Even if I try to explain to them 21st century skills, they will say, 'Okay, what's the point of 21st century skills?' I try, I do my best to explain it to them, but not all students are convinced of the importance of these skills." (F4)

4.1.6 Lack of technical and financial support

The technical and financial barriers add another layer to the challenges faced by educators. These challenges highlight how disparities in access to technology and financial resources create uneven opportunities for students to engage with 21st century skills. Dr. Eman speaks to the financial and technical barriers:

"Our students are not financially affluent, so they might not have access to great laptops or technology at home. Not everybody can afford those things. So, there is a bit of a disparity between who can afford to access the best technical products on the market and who can afford to pay for them." (F5)

Ms. Maha adds:

"The students are not always particularly technically proficient. Now, I am working here primarily as an EFL teacher. If you set up some activities which are designed to be done outside of the classroom, at home, maybe online, via the use of some software, or downloading a certain application or something like that, in some cases, some of the students might not be completely technically proficient, they may not be trained in how to use software packages." (F3)

Mr. Peter discusses the role of technical support:

"More financially challenged students may not have access to these devices or software. And they might need more assistance, and then the question is: who is there to provide the technical assistance? Is that the role of a technical support department, or is that the role of an English classroom teacher?" (M8)

Dr. Faisal touches on the challenge of technological issues:

"I feel like that could turn into a waste of time. We should get on with the lesson rather than risk wasting our time trying to fix these technological issues and forcing this thing on another two or four weeks and trying to solve this problem. So, technological faults and technological problems can be an issue here." (M9)

4.2 Factors hindering integrating 21st century skills into EFL classes

Having identified the challenges of integrating the 21st century skills into EFL university courses. This section reports on the various factors impeding the integration of 21st century skills into EFL classes.

4.2.1 Students’ previous learning experience

Students’ previous learning experience plays a crucial role in shaping their approach to 21st century skills. Dr. Omar reflects on the influence of the educational system as follows:

"The education system does not encourage much critical thinking and debate about relevant and complex issues. These lie under the surface. Most Saudi students are more than aware of social and even some difficult intellectual/philosophical issues. They are not encouraged to engage with these. Until these changes, the education system will be more mechanical than creative and transformative." (M10)

Mr. Kareem adds,

"School learning is a big factor; how they study in school shapes how they want to learn in college or university. So, when they go to university, they expect the same because they have done it this way for 12 years." (M11)

Dr. Rana points out the language barrier:

"If they were not introduced to critical thinking in their language at school, they would not know how to use it in their first language-it is like you ask someone to learn math in a second language. They did not learn math in their first language. This is how I see the competencies when students are introduced to them in English and do not practice them in Arabic." (F6)

Dr. Farah comments on the educational culture:

"It is the culture of the system itself. It is a test-driven system that values whatever is quantifiable, whatever is shown clearly that students have achieved. So, how will I prove to them that students are good at communication or creativity? So, the system does not value formative assessment; they only value summative assessment." (F7)

4.2.2 Administrative factors

Institutional policies and practices contribute to the factors hampering the integration of 21st century skills. Mr. David discusses institutional approaches:

We are preparing our students with the 21st century skills.' Yes, but the problem is how this discourse is trickling down into our day-to-day teaching and learning. That is a problem. We know it. The slogan is very beautiful, but the institution did not spend time training people on how to use these skills. We always take the shortcut because we would like to accelerate the result or they have the best result possible, so we take shortcuts." (M12)

Mr. David’s insights into institutional approaches reveal a discrepancy between the aspirational goals of teaching 21st century skills and the actual implementation within educational structures. This relates to the educational culture and its influence on students and teachers.

4.2.3 Instructor’s mindset

Instructors’ mindset is pivotal in the successful integration of these 21st century skills. Dr. Omar’s comments about the traditional mindset of teachers highlight the importance of educators’ attitudes and approaches in fostering an environment conducive to 21st century learning. Ms. Heba’s addition about the lack of a safe communicative environment in classrooms ties back to the need to change teaching methodologies and approaches to create more engaging and effective learning experiences. Dr. Omar highlights the mindset of educators thus:

"The mindset, the mentality of the teachers as well. If you work within a traditional framework and mindset, you will be an implementer of the content; you will not be a designer of learning opportunities for your students. So, I think some teachers go the easier way." (M10)

Ms. Heba adds,

"The lack of a safe environment encourages students to communicate. Some teachers only care about getting on with their lessons and finishing in time than allowing students to communicate meaningfully." (F8)

4.3 Proposed strategies to overcome the challenges of integrating 21st century skills

This section reports on some proposed strategies for the previously identified challenges.

4.3.1 Professional development

Professional development plays a critical role for educators. Dr. Saba suggests that providing training courses for teachers is a foundational strategy, emphasizing the need for skill-specific training to incorporate 21st century skills into curricula.

"Provide training courses for teachers on how to include 21st century skills in the course. If the course or the textbook is already equipped with the 21st skills, we could train teachers on how to activate these, how to use 21st century skills in the textbook, how to activate these skills with students, and how to practice these with students." (F9)

Mr. Mohammed and Dr. Lina reinforce this idea, advocating for workshops and seminars focused on teaching and assessing these skills. Mr. Mohammed supports this idea:

The simplest approach is to train educators in teaching and assessing 21st century skills. Implement workshops or seminars for this purpose and allow faculty to allocate a portion of grades (10-20%) to student projects focused on these skills. (M6)

Dr. Lina further suggests hands-on activities and experiential learning for teachers as follows:

"Teachers need to have some support in achieving their goals. In terms of the instructors, the teachers, or the doctors, I think they need-this is a personal view. They might need professional development, hands-on activities, and experiential learning to deal with these skills and how to integrate them into their teaching. I think the instructor must also have some room and some autonomy in his teaching, in how to choose the material, and how to deliver that material to his students." (F10)

Dr. Ali and Ms. Maha’s points about updating teaching methods and the importance of teacher training in technological competencies link back to the need for comprehensive professional development, addressing both content and delivery methods. Dr. Ali emphasizes updating teaching methods:

"Working in groups via department committees to update subject descriptions focusing on high levels of knowledge (analysis, evaluation, creativity)." (M3)

Ms. Maha notes,

"I am not downplaying the teacher training. There should be some teacher training courses. I would not want that to be the main thing, but teacher training is also important; getting the news, not to be resilient with the technological means that could assist their teaching but learn how to cooperate with it." (F3)

4.3.2 Teacher role in the classroom

Teachers’ evolving role in the modern classroom is important in the proposed strategies. Dr. Fasil’s proposal for teachers to educate students about the importance of 21st century skills highlights the need for educators to be facilitators of knowledge rather than just transmitters.

Dr. Fasil proposes:

"Provide a presentation-each teacher could present to their students about 21st century skills, their benefits, why we need them, and the important part. I would say not every skill is important for students." (M9)

Ms. Mona suggests demonstrating the real-world relevance of language learning strategies and emphasizing essential life skills like collaboration and communication, which ties back to the practical application of these skills.

Assist students in realising the practicality of language learning strategies by demonstrating their real-world relevance. Motivate them by linking lessons to real-life applications, emphasising the importance of collaboration, communication, and critical thinking as essential life skills. (F2)

4.3.3 Introducing 21st century skills in the education system

Systemic changes in the education system need to take place to overcome the previously mentioned hampering factors. Dr. Khalid’s statement about starting the training in critical analysis and other skills early in the education system points to the need for a foundational shift in how these skills are introduced and cultivated.

Training in essential skills like critical analysis for 21st century success should start early. Beginning at 18 or 19 is late, especially with the limited time available in preparatory programs. Therefore, these skills should be introduced at a younger age. (M13)

Dr. Ali’s advocacy for more student-centered learning and open discussion on challenging topics suggests a shift in teaching methods to encourage active learning.

Encourage open discussion on challenging topics and create a learning environment where students take charge of their education. Shift the teacher's role to a guide, facilitating learning rather than just delivering lectures. (M3)

Dr. Yasir and Dr. Hana emphasise integrating technology and extracurricular activities to enhance student engagement and skill application, suggesting practical methods for implementing these changes. Dr. Yasir commented thus:

Adopt flipped, blended, and hybrid learning methods with increased technology use. Incorporate extracurriculars like debates and competitions to enhance students' presentation skills and encourage active engagement and questioning. (M5)

Ms. Maha’s conclusion about utilizing courses better suited for teaching 21st century skills like creativity underlines the importance of a collaborative and holistic approach to education.

Other courses better suited for teaching 21st century skills, like creativity, should be utilised. This should be a collaborative effort to avoid neglecting essential language skills. (F3)

In conclusion, the findings highlight the need for early, comprehensive training in 21st century skills, emphasizing a collaborative approach to education. By adapting teaching methods and aligning them with real-world applications, students can better prepared for the demands of the modern world while maintaining a balance of essential language skills.

5 Discussion

Integrating 21st century skills into English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classes in Saudi universities presents a nuanced and multifaceted challenge. This complexity is rooted in the dynamic interplay between educational practice and pedagogical theory. The study reveals that these pedagogical, institutional and cultural challenges affect educators and students alike. This discussion aims to delve deeper into these challenges, drawing upon the insights from the current study’s findings and aligning them with existing literature, particularly emphasizing the perspectives of Tsourapa (2018), Chun and Abdullah (2022), and other scholars in the field.

5.1 Challenges in integrating 21st century skills

This research underscores several key challenges in integrating 21st century skills into EFL education. Central to these challenges is the absence of a standardised assessment rubric, as highlighted by Bolat (2022). This lack of clear assessment criteria complicates the instructors’ ability to measure and develop these skills in students effectively. Furthermore, the study revealed that technical and financial constraints significantly hamper the ability of instructors to utilize technology effectively, a crucial component in teaching these skills, resonating with the findings of Tsourapa (2018) and Fajriah and Septiyanti (2021).

Another critical challenge is the issue of time constraints. The current academic structure in Saudi universities does not afford sufficient time to develop and practice 21st century skills. This finding aligns with Tsourapa’s (2018) and Chun and Abdullah’s (2022) research, which also identified time limitations as a major barrier to effectively integrating these skills in EFL classrooms.

Additionally, the current study found a notable lack of student interest and engagement in activities geared towards developing these skills. This lack of enthusiasm can significantly hinder the active participation necessary for skill development, echoing the barriers identified by Fajriah and Septiyanti (2021) and Chun and Abdullah (2022).

5.2 Challenges in integrating 21st century skills

Contributing to these challenges are several underlying factors. The prevalence of traditional teaching methods in Saudi universities significantly impedes the integration of 21st century skills. These methods, characterized by a teacher-centered approach and a focus on rote memorisation, are not conducive to fostering critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity skills. This finding is in agreement with Alqudah and Altweissi (2021), who argue that adopting more dynamic and interactive teaching strategies is essential for preparing students for the challenges of the modern workplace and society.

Administrative constraints also play a significant role in these challenges. As Bedir (2017) highlighted, the curriculum’s focus on test-based assessment and lack of emphasis on 21st century learning can make teachers less aware and less equipped to integrate these skills into their teaching practices. Furthermore, if administrators do not recognise the importance of these skills, instructors may not receive the support or freedom to adopt new teaching methods that are better suited for the development of these skills.

The instructors’ mindset is another critical factor. Studies by Baran-Łucarz and Klimas (2020) and Bedir (2019) suggest that instructors who lack a deep understanding or hold negative beliefs about the importance of 21st century skills are less likely to implement instructional strategies that effectively foster these skills. Conversely, those who view these skills positively and understand their relevance are more likely to adopt innovative teaching methods that promote their development.

5.3 Proposed strategies

To address these challenges, a multifaceted approach is required. Professional development programs for instructors, as suggested by Alhothali (2021), are crucial. These programs should equip teachers with the knowledge and skills to effectively integrate 21st century competencies into their teaching. Training courses and workshops could be instrumental in providing in-service teachers with the necessary skills and knowledge.

Transitioning from traditional to more student-centered teaching methods is also recommended. This strategy, supported by Handayani (2017), involves moving from conventional lecture-based teaching to methods that encourage creativity, critical thinking, and active student engagement. Such approaches are more likely to promote the development of 21st century skills and prepare students for the challenges they will face in their future careers and lives.

Moreover, instructors themselves can be instrumental in overcoming these barriers. As Alamri (2020) points out, adopting innovative teaching methods and strategies that actively promote the development of 21st century skills can greatly enhance the learning experience. This could involve integrating project-based learning, collaborative tasks, and problem-solving activities into the EFL curriculum.

To conclude, the integration of 21st century skills in EFL classes in Saudi universities presents significant challenges, primarily due to traditional teaching methods, administrative constraints, and the mindset of instructors. However, the importance of these skills in preparing students for a rapidly evolving global landscape is undeniable. The present study, supported by the insights of Tsourapa (2018), Chun and Abdullah (2022), and other scholars, provides a comprehensive understanding of these challenges and offers a roadmap for addressing them. By empowering educators, rethinking pedagogical approaches, and aligning educational practices with the demands of the 21st century, educational institutions in Saudi Arabia can ensure that their students are proficient in the language and equipped with the critical skills needed for future success.

6 Conclusion

In this investigation, the aim was to explore the perspectives of EFL English instructors regarding the challenges of integrating 21st century skills in Saudi universities. The findings revealed that EFL instructors have a positive attitude towards integrating 21st century skills into English classes in Saudi universities, as reflected in their responses to the semi-structured interviews. Furthermore, the study demonstrated several challenges that hinder EFL instructors from integrating the 21st century in English classes: academic, institutional, collegial, and student-related challenges. Additionally, the study pointed out that students’ previous learning experiences, administration issues, and the instructor’s mindset were the factors that hindered the EFL instructors from integrating 21st century skills. The findings also revealed various strategies that may help solve the challenges of integrating 21st century skills in EFL classes in Saudi universities. The current study has some limitations. First, it has only offered data on perspectives held by male and female EFL instructors. Second, data was collected only through semi-structured interviews. Finally, the sample is limited to 30 EFL instructors. Based on the three limitations, some further research areas are suggested. First, a broader study could be conducted that includes the perspectives of both male and female students to contribute to knowledge in this area. Second, a mixed-methods research design is suggested for further research to elicit students’ perceptions about integrating 21st century skills in Saudi EFL classrooms. Finally, a bigger sample of instructors would help draw a more realistic picture and varied views about the challenges, factors, and strategies of integrating 21st century skills into Saudi EFL classrooms. Also, it is recommended to replicate the current study in other EFL contexts to see the differences and similarities in the reported findings.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Taibah University Permanent Committee for Scientific Research Ethics. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1302608/full#supplementary-material

References

Abu Bakar, A., Amat, S., and Mahmud, M. (2019). Issues and challenges of 21st century teaching and learning: the Malaysian experience. Int. J. Manag. Appl. Sci. 5, 6–11.

Alamri, H. (2020). Teachers' 21st century skills: how do Saudi EFL students evaluate their use? Saudi J. Humanities Soc. Sci. 5, 42–55. doi: 10.36348/sjhss.2020.v05i02.003

Alghamdi, A. (2022). Empowering EFL students with 21st century skills at a Saudi university: challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Educ. Learn. Dev. 10, 39–53. doi: 10.37745/ijeld.2013/vol10no3pp.39-53

Alhothali, H. M. (2021). Inclusion of 21st century skills in teacher preparation programs in the light of global expertise. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 9, 105–127. doi: 10.18488/journal.61.2021.91.105.127

Alqahtani, J. (2020). An Examination of the Higher Education Curriculum for Meeting Labor Market Demands of 21st Century Skills in Students: A Case Study of a University in Dubai, UAE (Doctoral dissertation). The British University in Dubai (BUiD)

Alqudah, M. A., and Altweissi, A. I. (2021). Faculty members' practice of 21st century skills in the Institute of Languages at the University of Tabuk from their point of view. Cairo Univ. J. Educ. 192, 471–495. doi: 10.21608/jsrep.2021.222629

Alzuoud, K., and Gaudel, D. (2020). The role of core skills development through English language teaching (ELT) in increasing the employability of students in the Saudi labour market. Int. J. Engl. Linguist. 10, 108–114. doi: 10.5539/ijel.v10n3p108

Ananiadou, K., and Claro, M. (2009). 21st century skills competencies for new millennium learners in OECD countries. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 41. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Ashraf, H., Ahmadi, F., and Hosseinnia, M. (2017). Integrating 21st century skills into teaching English: investigating its effect on listening and speaking skills. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. 7, 35–43. doi: 10.26634/jelt.7.4.13766

Baran-Łucarz, M., and Klimas, A. (2020). Developing 21st century skills in a foreign language classroom: EFL student teachers' beliefs and self-awareness. Acad. J. Mod. Philol. 10, 23–38.

Bedir, H. (2017). English language teachers' beliefs on 21st century learning and innovation skills. In Cukurova International ELT Teachers Conference (CUELT 3rd). Adana, Turkey.

Bedir, H. (2019). Pre-service ELT teachers' beliefs and perspectives on the 21st century learning and innovation skills (4Cs). J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 15, 231–246. doi: 10.17263/jlls.547718

Benson, C., and O’Dowd, R. (2014). 21st century skills and the teaching of English as a foreign language (EFL). TESOL Quarterly. 48, 127–154.

Bharathi, A. V. (2011). Communication skills–core of employability skills: issues and concerns. High. Learn. Res. Commun. 6:5. doi: 10.18870/hlrc.v6i4.359

Bolat, Y. (2022). The use of 21st century skills by secondary school English language teachers and their challenges (Master's thesis). Trakya Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

British Educational Research Association (BERA). (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research (4th ed.). London: BERA.

Byram, M. (2008). Intercultural competence and second language teaching: Exploratory case studies. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters

Chun, T. C., and Abdullah, M. (2022). The effects of language teachers' attitudes, barriers, and enablers in teaching 21st century skills at Chinese vernacular schools. Malaysian J. Learn. Instr. 19, 115–146.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (6th ed.). London: Routledge.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (laureate Custom ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Eaton, S. E. (2010). Global trends in language learning in the twenty-first century. Calgary: Onate Press.

Erdoğan, V. (2019). Integrating 4C skills of 21st century into 4 language skills in EFL classes. Int. J. Educ. Res. 7, 113–124.

Fajriah, Y. N., and Septiyanti, S. N. (2021). The challenges encountered by EFL teachers in developing students' 4C skills in 21st century education. J. Engl. Pedagogy Appl. Linguist. 1, 106–121. doi: 10.32627/jepal.v1i2.38

Fandiño Parra, Y. J. (2013). 21st century skills and the English foreign language classroom: a call for more awareness in Colombia. Gist Educ. Learn. Res. J. 7, 190–208.

Goh, C. C. M., and Parker, L. (2017). Learning 21st century skills through project-based learning in EFL classrooms. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 13, 1–10.

Griffin, P., and Care, E. (2015). “The ATC21S method” in Griffin, P., and Care, E. (Eds.), Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills methods and approach. (The Netherlands: Dordrecht: Springer), 3–33.

Guilherme, M. (2015). Developing intercultural communicative competence in the language classroom. J. Lang. Teach. Res, 6, 868–881.

Handayani, N. (2017). Becoming the effective English teachers in the 21st century: What should know and what should do? In English Language and Literature International Conference (ELLiC) Proceedings, volume 1, pp. 156–164).

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. (2016). National Transformation Program 2020. Available at: http://vision2030.gov.sa/sites/default/files/NTP_En.pdf

Lamb, S., and Hipps, C. (2015).Developing 21st century skills in the EFL classroom: An action research project. Language Learning & Technology, 19, 156–172.

Lieblich, A., Riessman, C. K., and Tobin, R. (2008). Narrative inquiry in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications

Menggo, S., Ndiung, S., and Midun, H. (2022). Integrating 21st century skills in English material development: what do college students really need? Englisia 9, 165–186. doi: 10.22373/ej.v9i2.10889

Merriam, S., and Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Nwagwu, L., Okere, C., and Branch, N. (2021). Educational challenges of the 21st century in a developing economy: contemporary possible solutions. Int. J. Innov. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. 9, 72–80.

Pardede, P. (2020). Integrating the 4Cs into EFL integrated skills learning. J. Engl. Teach. 6, 71–85. doi: 10.33541/jet.v6i1.190

Partnership for 21st Century Learning (P21). (2007). Framework for 21st century learning. Available at: http://www.p21.org/our-work/p

Tsourapa, A. (2018). Exploring teachers' attitudes towards the development of 21st-century skills in EFL teaching. Res. Pap. Lang. Teach. Learn. 9, 6–31.

Van Laar, E., Van Deursen, A., Van Dijk, J., and De Haan, J. (2017). The relation between 21st-century skills and digital skills: a systematic literature review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 72, 577–588. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.010

Wang, M. (2007). Designing online courses that effectively engage learners from diverse cultural backgrounds. British Journal of Educational Technology, 38, 294–311 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2006.00626.x

Warschauer, M. (2000). The changing global economy and the future of English teaching. TESOL Q. 34, 511–535. doi: 10.2307/3587741

Warschauer, M. (2007). Learning 21st century skills through technology: The changing nature of language acquisition. TESOL Quarterly, 41, 1–22.

Keywords: cross-cultural perspectives, 21st century skills, EFL instructors, higher education, EFL university courses

Citation: Alharbi NS (2024) Exploring the perspectives of cross-cultural instructors on integrating 21st century skills into EFL university courses. Front. Educ. 9:1302608. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1302608

Edited by:

Matthew R. Deroo, University of Miami, United StatesReviewed by:

Abdelhamid M. Ahmed, Qatar University, QatarJill Castek, University of Arizona, United States

Joyce West, University of Pretoria, South Africa

Copyright © 2024 Alharbi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Noof Saleh Alharbi, bnNtaGFyYmlAdGFpYmFodS5lZHUuc2E=

Noof Saleh Alharbi

Noof Saleh Alharbi