- 1Institute of Family Medicine, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Lübeck, Germany

- 2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel, Germany

- 3Department of Prosthodontics, Propaedeutics and Dental Materials, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel, Germany

Introduction: The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic brought public life to a standstill. For universities, this meant the suspension or corresponding adjustment of practical and theoretical teaching. In Germany, the Kiel Dental Clinic received special permits to start face-to-face teaching under appropriate hygienic conditions. Therefore, the aim of this study, which was conducted using a longitudinal qualitative panel, was to interview students and teachers over a period of three semesters under pandemic conditions regarding the effects of the pandemic on dental teaching at a structural, individual and social aspect in order to determine which strategies can be acquired for future teaching design.

Methods: Qualitative methods based on interviews were used for data collection. The same dental students from different semesters (6th, 8th and 10th) and the same teaching staff responsible for the content and implementation of courses within the dental curriculum were interviewed in the summer semesters of 2020 and 2021. The data analysis was performed by qualitative content analysis.

Results: A total of 27 students and 15 teaching staff participated. Our study team received interesting results on the implications of the teaching and learning situation from the start of the emergency transition to remote teaching and then to practical courses in face-to-face situations with specific regulations. Teaching under pandemic conditions resulted in a very stressful situation for the students and teaching staff. The learning process for teaching has led to an improvement in digital literacy for both groups over the last two years.

Discussion: This qualitative longitudinal study describes the different factors that played a role during the course of the various “Corona” semesters. The development process, from thankfulness to taking it for granted, demonstrated that students’ expectation towards the implementation of the courses increased. Simultaneously, the results clearly show that the degree of stress and anxiety among students and teachers increased also. The necessary self-structuring of everyday student life under COVID conditions was not possible for everyone. It was also noted that teachers in particular were aware of this and that they developed a certain vigilance towards students.

Introduction

Due to the outbreak of a new coronavirus (COVID-19), the first lockdown took place in Germany in March 2020, as in many countries worldwide. For the university sector, this meant the suspension of face-to-face teaching for the summer semester of 2020 (Abedi and Abedi, 2020; Barabari and Moharamzadeh, 2020; Prieto et al., 2021) and the adoption of an emergency transition to remote teaching. In public and private life, comprehensive, social distancing rules were introduced (Melnick and Ioannidis, 2020).

As a result of these regulations infrastructural measures related to digital teaching and practical clinical courses had to be implemented on a large scale in a very short time without prior testing. However, since dental education is a very clinical and hands on-oriented programme which includes patient treatment and is conducted almost entirely in person, there was little to no experience with digital teaching concepts. In various studies employing both qualitative and quantitative approaches, it was observed that students and lecturers exhibited a highly diverse range of feeling (Goob et al., 2021; Hattar et al., 2021; Virtanen and Parpala, 2023).

This was characterised by insecurity, powerlessness and helplessness. The repression of the situation also played a role, especially with regard to the desire to continue studying. Additionally, questions arose regarding what this meant for the study of dentistry itself and whether this situation would have an effect on the length of study (Machado et al., 2020; Prieto et al., 2021; Goob et al., 2021; Hertrampf et al., 2022a; Goetz et al., 2023). The lack of social contact, both during studies and in the private sphere, were also described as deficits (Prieto et al., 2021; Schlenz et al., 2020; Hattar et al., 2021; Hertrampf et al., 2022b; Goetz et al., 2023).

The rapid, comprehensive and innovative conversion to digital teaching (Prieto et al., 2021; Hertrampf et al., 2022a), as well as the commitment to conduct practical courses under difficult social distancing and hygiene rules, was often described with thankfulness (Hertrampf et al., 2022b). Digital teaching in particular was definitely seen as an opportunity for the development of virtual educational teaching concepts (Prieto et al., 2021; Schlenz et al., 2020; Hertrampf et al., 2022a).

During the course of the pandemic, severe restrictions continued to occur worldwide. These restrictions affected individuals and educational institutions in different ways for many months such as lower mental health by students and staff as well as challenges for institutions due to ad hoc digitalisation and insufficient IT structure (Hertrampf et al., 2022a; Loch et al., 2021).

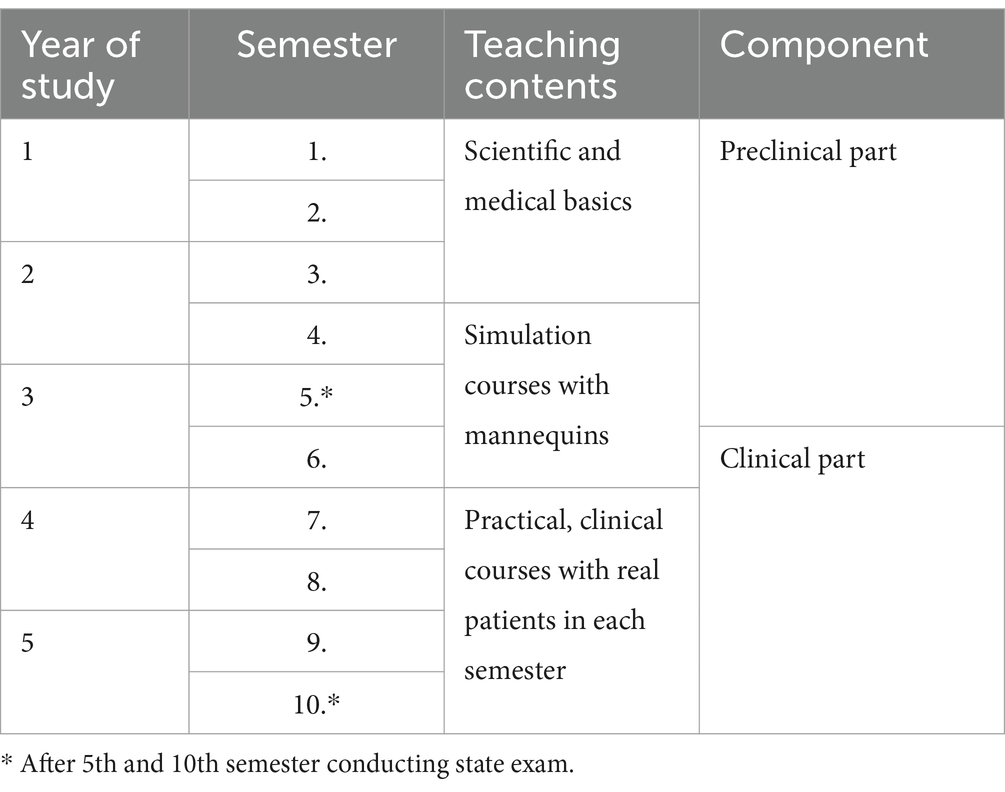

The extent to which dental students and their teachers perceived these restrictions during the course of their studies and how their views of the altered method of teaching may have changed during the course of the pandemic has not yet been sufficiently investigated also for the German situation. The dental curriculum consists of five years, divided in preclinical and clinical components, in Germany. For detail information see Table 1.

The aim of this study was to evaluate an affected cohort of students and lecturers during the summer semester of 2021 under the existing pandemic conditions with regard to the following aspects:

1. What effects could be observed on a structural, individual and social aspect in dental teaching under COVID conditions?

2. What strategies can be acquired for future teaching design?

Materials and methods

Study design

A qualitative longitudinal approach was undertaken in this study in the form of structured interviews to explore the experiences of students and teaching staff, starting with the impact of the pandemic on teaching in the summer semester 2020 and the two following semesters, winter semester 2020/2021 and summer semester 2022. Qualitative longitudinal research allowed for an understanding of subjective experiences and the changing attitudes of individuals over time (Neale, 2016). With this methodological approach, it was possible to evaluate the changes of subjective attitudes and opinions during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic (Terzis et al., 2022). The COREQ guideline (Supplementary file), a checklist for comprehensive reporting of qualitative studies (Tong et al., 2007), was used in this study.

Chronology of teaching and learning situation during the pandemic at Kiel Dental Clinic

In the third week of March 2020, a national lockdown was declared in Germany. In this context, the universities were asked to switch all teaching from face to face to on-line. At the Kiel Dental Clinic, lecturers of theoretical subjects were then asked to teach their lessons via an on-line platform either “in-time” live or to make them available “digitally on demand” from the beginning of the summer semester. This was intended to allow increased availability of the teaching material for students on the programme.

At the beginning of May, the dental clinic received a special permit from the Ministry of Education and Science for the re-introduction of the practical, hands-on and clinical component of the course. Under very strict conditions, the clinical skills courses started on 4 May 2020, with the clinical treatment courses following one week later.

The special permit included strict social distancing and hygiene guidelines, which affected the procedures undertaken within the building and the provision of the individual courses.

In order to maintain adequate social distancing a one-way system was established within the building. In addition to the main entrance, doors through which to enter and exit the building were specified for students. The routes to the respective course rooms were also prescribed. Each student was given a fixed time to enter and to leave the building. Furthermore, the group size was significantly reduced for all courses. As a result, course times were extended throughout the day, which, in part, meant the introduction of extended hours and working patterns for staff. As a result of the special measures introduced, all courses for the summer semester and the subsequent state examinations were successfully conducted without a single COVID case being reported with in the clinic, and the dental clinic received an extended permit for the winter semester 2020/2021 for all courses. Subsequently, theoretical teaching was allowed to attendance based teaching under appropriate social distancing and hygiene rules.

However, due to three COVID cases among teachers of a course shortly before Christmas, the directors of the dental clinic decided to suspend all teaching completely during the last few days before Christmas. No further COVID cases were subsequently identified.

After Christmas holidays, the Board of the University Hospital decided to suspend the continuation of clinical treatment courses from January 2021. The clinical skills courses were allowed to continue and the theoretical teaching was switched back from face to face to on-line. Only after various discussions between the clinic directors and the board were the clinical courses allowed to continue under the existing hygiene rules; the focus on continuing these courses was placed in the final semester so as to not jeopardise the subsequent practical state examinations.

Students of the other clinical treatment courses were given the opportunity, if proof of achievements of the clinical courses were not completed, to undertake them during the summer semester. For the summer semester of 2021, all clinical and practical courses were conducted with special permission and under the special hygiene and social distance regulations, and theoretical teaching was again conducted in person.

Participants and recruitment

A qualitative study was conducted at the Kiel Dental Clinic in the summer semester of 2020 with students from the 4th, 6th, 8th and 10th semesters (n = 39) and lecturers from four clinics (n = 19) participating (Hertrampf et al., 2022a, 2022b). With the expectation of nine students from the 10th semester of 2020, an adapted guideline interview was planned for the summer semester of 2022 with the students. This was then followed for the 6th, 8th and 10th semesters as well as for the 19 lecturers. The interview guideline was adapted from the interviews in the summer semester of 2020.

Due to the same cohort were interviewed the same inclusion criteria were set as used in the first survey of 2020. For the students, the inclusion criteria was involvement in the respective teaching and learning subjects, matched age and sufficient knowledge of the German language. For the lecturers, the inclusion criteria were responsibility for the content of the teaching and its implementation in one of the four clinics as well as sufficient knowledge of the German language.

The project management informed all participants personally about the study and asked to participate again.

The interviews were conducted by the same member of the working group from the middle of the summer semester of 2021 and during the subsequent lecture-free period. Personal appointments were made for all interviews (hygiene and social distancing regulations could thus be observed). Some of the interviews were conducted telephonically; and it was accepted that this methodologically is possible within the design (Sturges and Hanrahan, 2004).

Data collection

The current interview guide from the summer semester of 2020 was adapted for a panel survey and coordinated within the working group. This included team of sociologists, health services researchers, physicians, dental practitioners and dental students.

The interview guide focused on the following topics (see Supplementary file):

• Teaching aspects under pandemic conditions divided into structural, individual and social aspects.

• History of practical courses during the pandemic situation.

The guide was identical for students and lecturers and was tested with regard to comprehensibility and sequence with one student and one lecturer. No changes or adaptations were found to be necessary.

Data analysis

All interviews were digitally audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were not returned to the participants for comments and correction. During the transcription, the texts were anonymised and further subjected to qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2010). To support the data analysis, the computer software ATLAS.ti 8.4 (Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2020) was used. The research team used a deductive–inductive approach for generating thematic categories. Firstly, a provisional category system was developed based on the interview guide in terms of the deductive approach. During the analysis, the provisional category system was adjusted according to the content of the transcripts. Emerging new categories were added in line with an inductive approach. Transcripts were coded independently into main categories and subcategories by one member of the working group (IR) following a consensus meeting in which discussions were held until an agreement was reached. Within the consensus meeting four people participated on the discussion process. These were a dental student (IR), a sociologist and health services researcher (KG), and two dental practitioners with further qualification for education and didactic (H-JW, KH). For publication, the participant quotations were translated from German into English.

Ethical approval

The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Kiel, Germany (D509/20) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. A signed consent form is available for each participant which includes permission to publish anonymised quotations.

Results

Sample characteristics

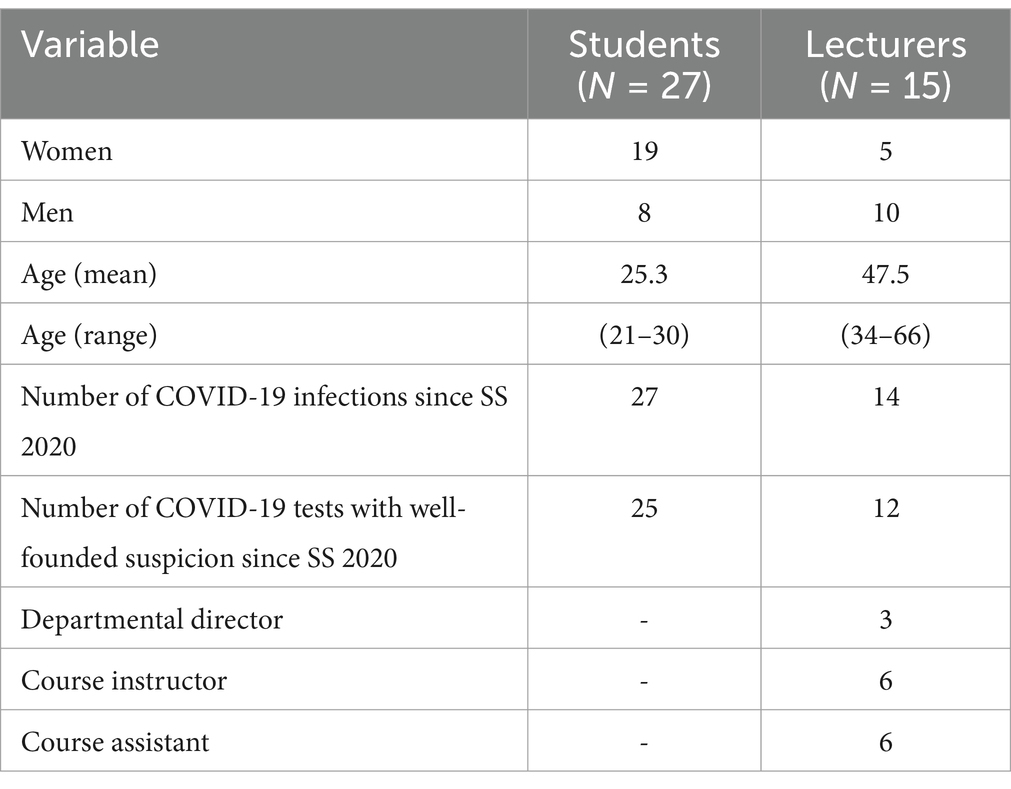

A total of 42 interviews were conducted in 2022; 27 were conducted with dental students and 15 with teaching staff. Seven people were not available for an interview due to different reasons like lectures changed jobs or responsibilities or students were not interested in participating again. Interview duration varied and was 33.3 min on average for the group of dental students (min. = 22 min, max. = 55 min) and 33 min for the teaching staff (min. = 22 min, max. = 46 min). Participant characteristics are shown in Table 2.

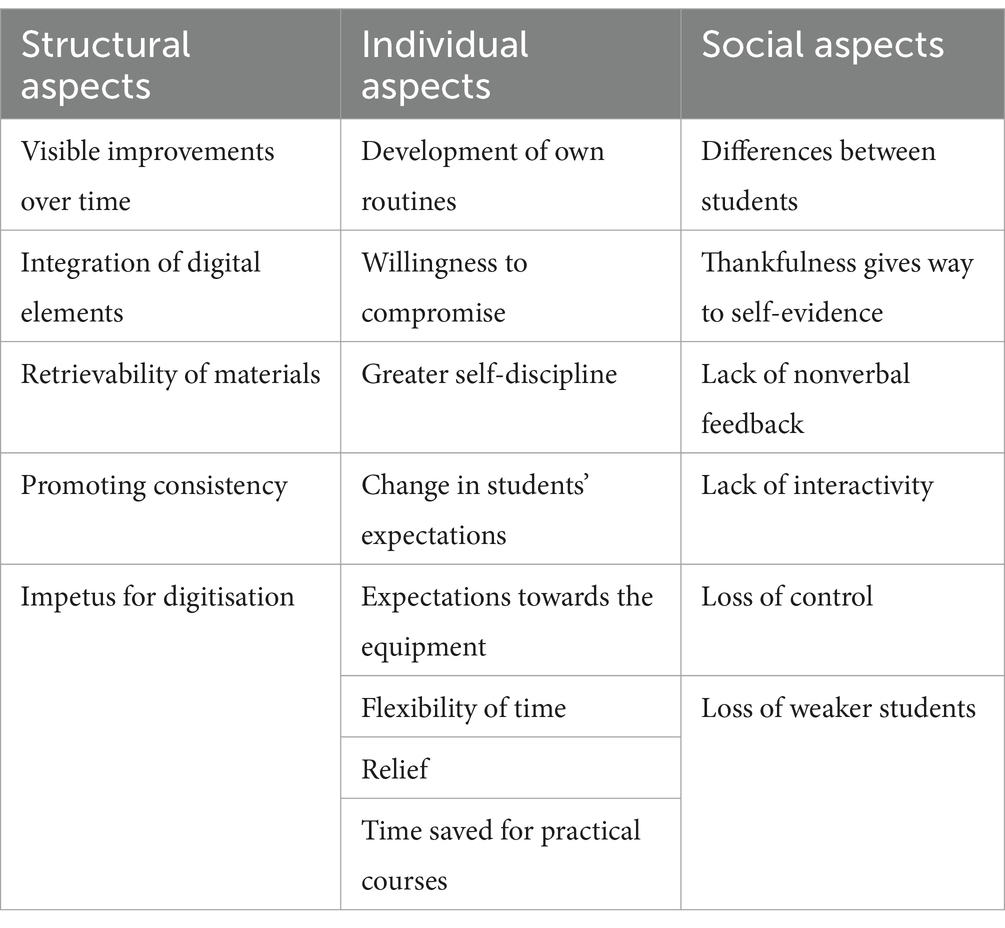

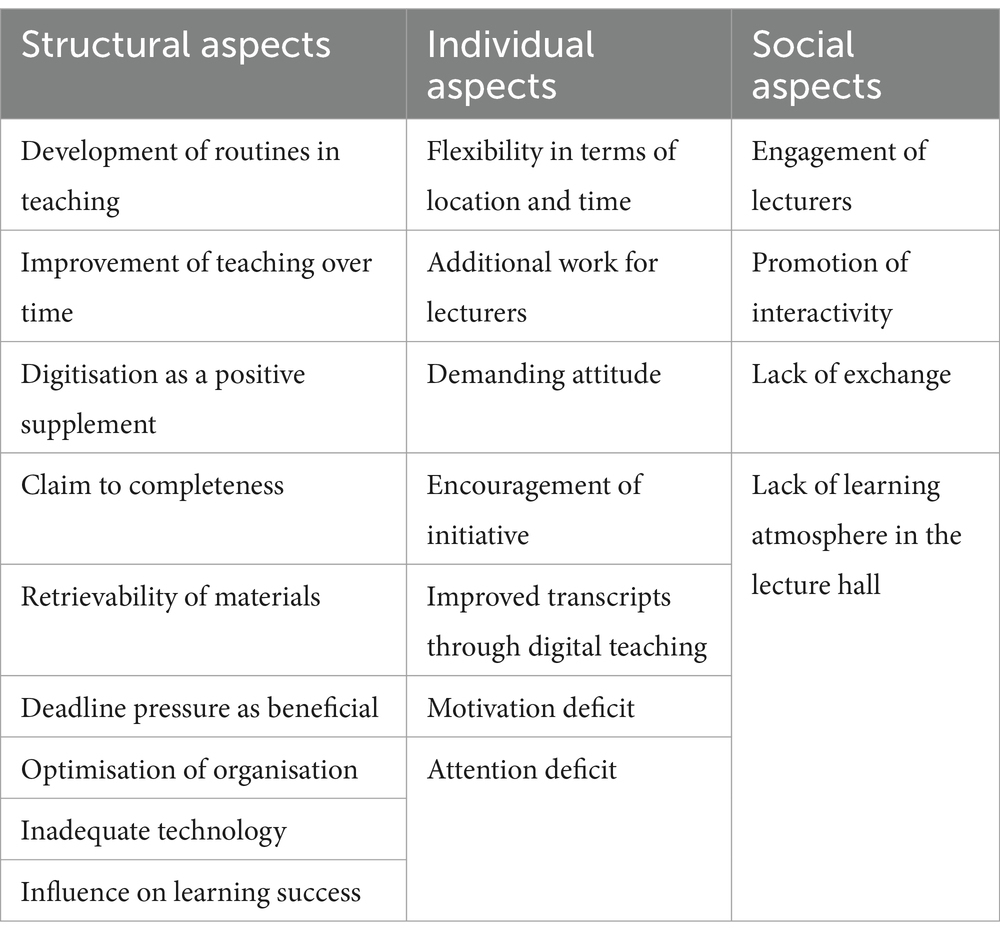

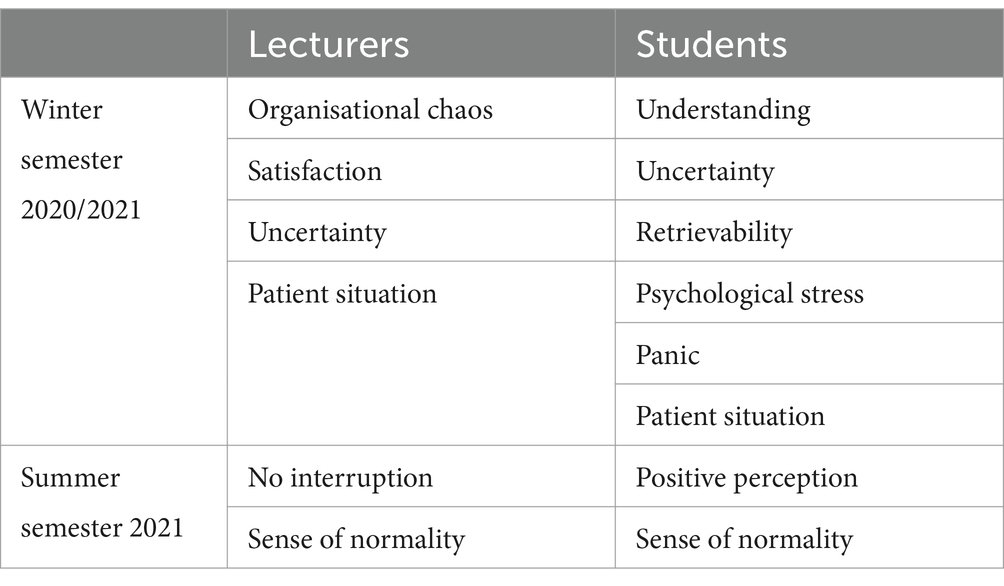

In this study, three main categories were explored concerning the theme ‘Perception of teaching aspects under pandemic conditions’. These categories, structural aspect, individual aspect and social aspect were further divided into students and teaching staff perspectives. For clarity, the perspectives of students and teaching staff were separated into two separate tables (Tables 3, 4). Furthermore, the theme ‘History of practical clinical courses during the pandemic situation’ was divided into two main categories – winter semester 2020/2021 and summer semester 2021 – and is presented in Table 5. The description of the results followed by the two themes ‘Perception of teaching aspects under pandemic conditions’ and ‘History of practical clinical courses during the pandemic situation’ and quotations were used to illustrate relevant statements reported by the participants (students [S] and teaching staff [TS]) and were reported within the results.

Table 3. General reflections on digital teaching during the pandemic from the lecturers’ perspectives – a presentation of the main categories and subcategories.

Table 4. General reflections on digital teaching during the pandemic from the students’ perspectives – a presentation of the main categories and subcategories.

Table 5. Teaching in the practical courses during the pandemic from the perspectives of lecturers and students – a presentation of the main categories and subcategories.

Theme: teaching aspects under pandemic conditions

This theme describes different experiences of students and teaching staff during the teaching period under pandemic conditions. Three main categories were created and divided into different subcategories for students and teaching staff (Tables 3, 4).

Structural aspect

The category “structural aspect” observed aspects of teaching that were essential for the organisation and delivery of the specific teaching outcomes.

Overtime, teaching staff perceived a visible improvement in relation to their on-line teaching and the use of the equipment required for delivery of the teaching material.

“While the routine of developing the seminars and holding them has increased significantly, the technical equipment has improved – better microphones, camera equipment, a second laptop for the second course. That has improved significantly.” (TS06)

Moreover, they stated that on-line teaching could be a favourable complement to analogue teaching.

“I think that in the long term (laughs) it is a wonderful complement to face-to-face teaching, but I do not think it will permanently replace face-to-face teaching.” (TS04)

A positive development was found in the availability of teaching materials as one teaching staff member stated:

“[The fact] that it is permanently available, what one had recorded there, that all students have the possibility to access it at any time, I think that’s something positive.” (TS04)

Furthermore, one of the teaching staff argued that this specific pandemic situation was the driver for the introduction for digitisation.

“Well, the one that we were practically forced to digitise. It was imminent. It was to be expected, and we always put it off a bit.” (TS08)

Students observed that routines were developed within the teaching activities.

“I would say that most areas, so to speak, in our dental clinic, have adjusted to it, and I would say that it has actually gone quite well.” (S06)

Moreover, students perceived that this development led to an improvement in on-line teaching over time. They argued that the digitisation was a positive complement to analogue teaching. However, students missed the completeness of some lectures and more engagement of some teaching staff.

“They are also paid for (paid for teaching). And there are still videos – and I understand that now after, yes, well, the first/s, now that we are in the third semester (during the COVID pandemic) – there are still lectures that are still not held or recorded.” (S17)

An advantage for the learning process for the students was the availability of teaching materials when required and in their own time.

“Yes, as I said, I think it’s an advantage to be able to watch things several times if you have not understood them. You can also watch something accelerated (laughs).” (S30)

Additionally, it was highlighted that some aspects concerning the organisation of on-line teaching could be improved, which also related to the technical equipment. Students perceived that learning outcomes were influenced by the teaching situation, and they argued that the results were better when the meeting was face-to-face.

“But even so, I cannot say that it really completely replaced the face-to-face event. Well, you could already tell that you could learn better with face-to-face events than with digital events.” (S15)

Individual aspect

The category “individual aspect” described their own feelings and experiences in dealing with this specific teaching situation.

Over time, the teaching staff accepted that they had to teach on-line, however, they saw it as a compromise. “Nevertheless, it is somehow second choice. And I think we can reflect on it quite positively, but still with a `but’ in it.” (TS02)

The teaching staff recognised a change in within the student body attitude to one of entitlement and this concerned the teaching method and its usage. Furthermore, the scope of time to implement on-line teaching in a daily routine required more self-discipline.

As one teaching staff member stated:

“I think that [it] has become a bit more, the personal responsibility has become more.” (TS02)

However, due to on-line teaching, the teaching staff stated that they had more temporal flexibility and noticed a time saving for the practical courses. Some of the teaching staff also stated that they felt relieved in the second year of the pandemic because some of the teaching material was already available for the students.

Students recognised that the teaching staff had an additional burden on them as this way was a new way of teaching and additional input was required for preparation and delivery of teaching material.

“And I think it’s also quite a lot of work for them to do that on top of their normal work, because it’s not like they do anything with the media.” (S10)

Additionally, a significant number of students appreciated this kind of teaching as it allowed them to be more independent and gave them a higher degree of flexibility in terms of time and place.

“I actually find it more relaxed because you are more flexible in terms of time. You can simply work from home because you do not have to rely on the premises here, I say.” (S14)

However, some of the students noticed innate deficits concerning motivation to learn from on-line materials and occasionally it was difficult to remain attentive during in on-line teaching courses. One student stated:

“I found that when the camera was off, one was very tempted not to listen very attentively. […] Many people then said that they were cleaning up or cooking dinner or something…” (S26)

Social aspect

The category “social aspect” referred to aspects that could have an impact on the relationship and communication with each other. The teaching staff expressed concerns that weaker students could get left behind in their studies due to the on-line teaching and that this group of students would receive none of the necessary feedback.

“I rather have the feeling that the gap is widening, that the students who are good anyway and can learn well benefit from this way. And the students who are weaker, who need guidance, who need feedback, also feedback in the direction that they are not doing so well right now, in order to motivate themselves again to do more, that they are being left behind a little bit.” (TS13)

Moreover, the teaching staff observed that appreciation was replaced by unappreciativeness after two years of the pandemic.

One teaching staff member stated:

“I found that this was very gratefully received in the first semester, but by the second or third semester, it was more of a matter of course – sure, that’s how it’s going to take place.” (TS12)

The teaching staff also missed the interaction with their students as well as the nonverbal feedback. One teaching staff member argued that students would be out of control. The teaching staff had the feeling that some students were not engaged with their studies. It is not known whether students were actively involved and engaged on-line teaching or whether they simply logged in and did other things.

However, the students recognised that the teaching staff were very engaged with the teaching.

“But, otherwise I found it very positive, and I had the feeling that the dental clinic in particular and many lecturers in general also put in quite a lot of effort.” (S26)

Some of the teaching staff used additional on-line elements to support interactivity as one statement from a student highlighted:

“And then the professor always asked a kind informal survey, like a little exam with about five questions about where you stand, and that was pretty cool.” (S02)

Finally, students missed the exchange with their fellow students as well as the atmosphere within the lecture hall.

“I miss sitting in the lecture hall with fellow students and somehow exchanging ideas, so I would say that [the] social component of studying, I miss that a lot too.” (S31)

Theme: history of practical courses during the pandemic situation

This section describes how students and teaching staff perceived the practical courses from the winter semester of 2020/2021 to the summer semester of 2021. During the period of practical courses, different feelings and experiences were observed. The main categories and subcategories that reflected the feeling and experiences of students and teaching staff are presented in Table 5.

Winter semester 2020/2021

The teaching staff found the start of practical courses in the winter semester to be chaotic, especially at the point of organisation due to the different regulations.

“It required a lot of organisation. So, what I have already said, also a lot of willingness to find a solution from the deanery’s side and also from the board’s side.” (TS11)

In hindsight, teaching staff were satisfied with the different solutions put in place to overcome these difficulties and the practical courses took place. However, during the courses and even before they started, the teaching staff felt insecure. After the Christmas period, the clinical courses with patients were suspended due to COVID cases in the clinic.

“There was a certain insecurity, also in the whole team, because at first there were no courses and everything was closed and…” (TS04)

The decision to suspend the clinical component of the course also raised concerns about the treatment of patients. Patients are an essential part and an important component of the courses.

As teaching staff were concerned that patients would be left untreated or that they could not finish the treatment process.

“We had treated patients; what happens to the patients who are now fitted with temporaries?” (TS04)

Students had a great understanding of the uncertain situation as one statement demonstrated:

“Yes, and also that we were allowed to treat again relatively early, and the other way around. I also thought it was appropriate that we stopped before Christmas. So, I think that was the right step.” (S12)

A number of students remained uncertain due to the suspension of the clinical courses. One student argued:

“That was a pity, of course, also that you did not know when it would go on, will it go on, so this uncertainty for which no one can really do anything, but that is of course already difficult.” (S12)

The uncertainty also implicated the feeling of permanent availability in order to be constantly prepared for any changes in teaching practices. Most of the students stated that they experienced psychological stress and some felt panic that they lost one semester of teaching.

“I remember that we were all, I think, psychologically quite shaken up, because even during this forced lockdown, you did not have two months off, but every day was somehow… You did not know at all what would happen next.” (S24)

This feeling of uncertainty was also transmitted to patients. Students perceived that some patients were impatient.

“The patients became impatient, that was very, very unpleasant, I would say.” (S24)

Summer semester 2021

In contrast, the summer semester was characterised by a feeling of normality for both teaching staff and students.

The practical courses took place under appropriate social distancing and hygiene precautions.

“And that, I found, was actually almost comparable to courses outside Corona in terms of the overall situation.” (TS04)

Due to the improved COVID pandemic situation the regulations for practical clinical courses were reduced to a minimum, and there were no interruptions of the practical courses during this time.

Moreover, students perceived the summer semester and the performance of practical courses as very positive and they felt more certainty.

“That was much more positive because it was accompanied by a reduction in the number of COVID cases. We also received more concessions from the University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein (UKSH) and there was a little more certainty that it could be carried out in this way.” (S08)

Discussion

The results of the interviews conducted with students and teaching staff were based on a qualitative longitudinal approach. This is an important methodological approach to consider experiences and their changes over time (Neale, 2016). The interviews started in the summer of 2020 and were repeated with the same participants in the summer of 2021. Our study team encountered interesting results relating to the implications of the teaching and learning situation from the start of the emergency transition through to remote teaching and then to face to face practical and clinical courses with specific regulations. In general, teaching under pandemic conditions resulted in a very stressful situation for the students in the clinical courses, affecting not only their course achievements and their treated patients but also their state examinations in the final semester. Moreover, different aspects—structural, individual and social—affected for both the students and teaching staff during this time. The teaching staff in particular perceived a change in the attitudes of students. During the summer of 2020, the change in teaching style was received with interest albeit with some trepidation, but the longer this kind of teaching took place, the more it became more routine as our results demonstrated from the interview in the summer of 2021. Furthermore, an increased entitlement concerning design, availability and update of teaching material was observed by students. The learning process over the last two years in relation to moving to a virtual environment for teaching has been tremendous and has led to an improvement in digital literacy for both groups. Over time, the students and teaching staff perceived an experienced handling of the digital courses and the use of digital equipment and furthermore to handling this specific situation for their own satisfaction. Another study with university students in Germany also s describes that this learning experience could lead to improved one’s own self-management and strengthening self-discipline by students (Huang and Yoon, 2023).

Also, it was found that students with low self-efficacy beliefs needed more support regarding the implementation of on-line teaching formats (Roick et al., 2023). In contrast, the support for face-to-face feedback was missing at the beginning of the emergency transition to remote teaching, and so alternative approaches had to be considered to ensure that students could receive feedback from the teaching staff as well from the other students. Feedback is an important tool for the students’ learning process (Fine et al., 2023).

Moreover, our results highlighted that the gap widened between ‘weaker’ and ‘stronger’ students during on-line teaching. The teaching staff perceived that some students (called ‘weaker’) need more support in terms of feedback than other student. This related to the question of how teaching staff can deal with such an observation and the kind of support that would be useful for students. Maybe it depends also on the personality of the students as some are extroverted or some introverted. It can be assumed that the type of personality a person has could significantly influence the learning style as a survey with students observed (Tovmasyan et al., 2023). To understand and evaluate know more about the intrapsychic processes and cognitive patterns, more research is needed.

One further finding was that students and teaching staff thought that theoretical digital courses can actas a supplement to traditional face-to-face classes. However, a small, randomised control experiment with students from statistics courses showed no difference concerning the effectiveness between face-to-face and synchronous on-line teaching (Cheung et al., 2023). Due to the fact that dental students treating patients in their clinical courses face-to-face teaching is indispensable.

The different changes in performance of the practical courses led to psychological reactions such as excessive insecurity, tension and stress, which have also reported in other studies (Loch et al., 2021). Moreover, a study with teachers at a Finnish University showed that their work stress increased under COVID-19 conditions in combination with the specific teaching situation (Virtanen and Parpala, 2023). Both students and teaching staff had to learn to cope with the various difficulties over time. It would be interesting to know more about the specific coping mechanisms and how students and teaching staff can be supported. An educational design that encourages active and collaborative learning, as presented by Green et al. (2020), could be an effective approach for the future (Green et al., 2020).

Limitations and strengths

The results of this qualitative study are based on interviews. As such, the statements made by the participating students and lecturers are subjective. Therefore, it is not possible to make any statement regarding the truthfulness of the information because it is subjective coloured by own experiences and expectations. No participant validation has been undertaken. Since participation was voluntary, it must also be assumed that the study attracted interested students who were more open to the topics being discussed. This selection bias may be reflected in the results and must therefore be considered in the interpretation.

Furthermore, it must be noted that a qualitative approach does not allow for a generalisation of the results. However, the desired number of participants and thus the desired saturation were achieved which was determined when no additional data were found (Nelson, 2017). The quality of the study was ensured by adherence to the quality criteria of qualitative social research (Walby and Luscombe, 2017). All interviews were conducted by the same person using the same interview guide for all students under the same general conditions. In addition, the process of each interview was documented according to a protocol that was previously agreed to. Other strengths of this study include the following: firstly, students and lecturers were asked about the same aspects in the interview and secondly, it was a longitudinal panel study. This meant that common and different perspectives could be worked out very well over a time period of three semesters.

Conclusion

This qualitative longitudinal study describes the different factors that played a role during the dental education of the various “Corona” semesters. Students developed a sense of expectations rather than thankfulness and it shows that the students’ expectation towards the implementation of the courses increased. Simultaneously, the results clearly show that the degree of stress and anxiety among students and teachers increased also. The necessary self-structuring of everyday student life under COVID conditions was not possible for everyone. It is worth noting here that teachers in particular were aware of this and that they developed a certain vigilance towards students. The use of different coping strategies such as by emotional or social support in dealing with similar situations could be a possible option.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of the University of Kiel, Germany. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft. IR: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. H-JW: Conceptualization, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. KH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study was supported by the Medical Faculty of the Christian-Albrechts-University, Kiel.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their thankfulness to the students and teachers who participated in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1293742/full#supplementary-material

References

Abedi, M., and Abedi, D. (2020). A letter to the editor: the impact of COVID-19 on intercalating and non-clinical medical students in the UK. Med. Educ. 25:1771245. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1771245

Barabari, P., and Moharamzadeh, K. (2020). Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and dentistry-a comprehensive review of literature. Dent. J. 8, 1–18. doi: 10.3390/dj8020053

Cheung, Y. Y. H., Lam, K. F., Zhang, H., Kwan, C. W., Wat, K. P., Zhang, Z., et al. (2023). A randomized controlled experiment for comparing face-to-face and online teaching during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Educ. 8:1160430. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1160430

Fine, P., Leung, A., Tonni, I., and Louca, C. (2023). Dental teacher feedback and student learning: a qualitative study. Dent. J. 11:164. doi: 10.3390/dj11070164

Goetz, K., Wenz, H.-J., and Hertrampf, K. (2023). Certainty in uncertain times: dental education during the COVID-19 pandemic-a qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 3039–3049. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043090

Goob, J., Erdelt, K., Guth, J. F., and Liebermann, A. (2021). Dental education during the pandemic: cross-sectional evaluation of four different teaching concepts. J. Dental Educ. 85, 1574–1587. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12653

Green, J. K., Burrow, M. S., and Carvalho, L. (2020). Designing for transition: supporting teachers and students cope with emergency remote education. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2, 906–922. doi: 10.1007/s42438-020-00185-6

Hattar, S., AlHadidi, A., Sawair, F. A., Alraheam, I. A., El-Ma'aita, A., and Wahab, F. K. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on dental education: online experience and practice expectations among dental students at the University of Jordan. BMC Med. Educ. 21, 151–160. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02584-0

Hertrampf, K., Wenz, H.-J., and Goetz, K. (2022b). Covid-19: teaching and learning in practical courses under special regulations—a qualitative study of dental students and teachers. BMC Med. Educ. 22, 596–605. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03656-5

Hertrampf, K., Wenz, H.-J., Kaduszkiewicz, H., and Goetz, K. (2022a). Suspension of face-to-face teaching and ad hoc transition to digital learning under Covid-19 conditions—a qualitative study among dental students and lecturers. BMC Med. Educ. 22, 257–267. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03335-5

Huang, J., and Yoon, D. (2023). Paradigm model of online learning experience during COVID-19 crisis in higher education. Front. Educ. 8:1101160. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1101160

Loch, C., Kuan, I. B. J., Elsalem, L., Schwass, D., Brunton, P. A., and Jum'ah, A. (2021). COVID-19 and dental clinical practice: students and clinical staff perceptions of health risks and educational impact. J. Dental Educ. 85, 44–52. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12402

Machado, R. A., Bonan, P. R. F., Perez, D., and Martelli, J. H. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and the impact on dental education: discussing current and future perspectives. Braz. Oral Res. 34:e083. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2020.vol34.0083

Melnick, E. R., and Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2020). Should governments continue lockdown to slow the spread of covid-19? BMJ 369:m1924. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1924

Neale, B. (2016). Introducing qualitative longitudinal research. What is qualitative longitudinal research? London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic, 1–22.

Nelson, J. (2017). Using conceptual depth criteria: addressing the challenge of reaching saturation in qualitative research. Qual. Res. 17, 554–570. doi: 10.1177/1468794116679873

Prieto, D., Tricio, J., Caceres, F., Param, F., Melendezm, C., Vasquez, P., et al. (2021). Academics' and students' experiences in a chilean dental school during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 25, 689–697. doi: 10.1111/eje.12647

Roick, J., Poethke, P., and Richter, M. (2023). Learners’ characteristics and the mastery of digital education during the COIV-19 pandemic in students of a medical faculty in Germany. BMC Med. Educ. 23:86. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04012-x

Schlenz, M. A., Schmidt, A., Wostmann, B., Kramer, N., and Schulz-Weidner, N. (2020). Students' and lecturers' perspective on the implementation of online learning in dental education due to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): a cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 20, 354–360. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02266-3

Sturges, J. E., and Hanrahan, K. J. (2004). Comparing telephone and face-to-face qualitative interviewing: a research note. Qual. Res. 4, 107–118. doi: 10.1177/1468794104041110

Terzis, L. D., Saltzman, L. Y., Logan, D. A., Blakey, J. M., and Hansel, T. C. (2022). Utilizing a matrix approach to analyze qualitative longitudinal research: a case example during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Qual. Meth. 21, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/16094069221123723

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., and Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 19, 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Tovmasyan, A., Walker, D., and Kaye, L. (2023). Can personality traits predict students’ satisfaction with blended learning during the COVID-19 pandemic? Coll. Teach. 71, 49–55. doi: 10.1080/87567555.2022.2156450

Virtanen, P., and Parpala, A. (2023). The role of teaching processes in turnover intentions, risk of burnout, and stress during COVID-19: a case study among Finnish university teacher educators. Front. Educ. 8:1066380. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1066380

Keywords: COVID, dental education, pandemic, panel, qualitative study, students’ experience, teachers’ experience

Citation: Goetz K, Reimer I, Wenz H-J and Hertrampf K (2024) From thankfulness to taking it for granted – a qualitative study of dental education during COVID. Front. Educ. 9:1293742. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1293742

Edited by:

Melanie Nasseripour, King’s College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Muhammad Kristiawan, University of Bengkulu, IndonesiaJenny Samaan, Child Family Health International (CFHI), United States

Gurdip Kaur Saminder Singh, UNITAR International University, Malaysia

Copyright © 2024 Goetz, Reimer, Wenz and Hertrampf. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katja Goetz, a2F0amEuZ29ldHpAdW5pLmx1ZWJlY2suZGU=

Katja Goetz

Katja Goetz Ida Reimer2

Ida Reimer2