- Faculty of Management, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

This research delves into the challenging paradox facing university faculty: they are often hired with minimal formal teacher training yet must exhibit teaching effectiveness when seeking promotion or tenure. This issue becomes particularly salient for educators with non-traditional, professional backgrounds who must demonstrate pedagogical competence despite lacking conventional academic training. This study examines teaching dossier guidelines employed by prominent universities that hire permanent teaching-focused business faculty who may have diverse, non-traditional backgrounds. For example, a Chartered Professional Accountant who trained in a public accounting firm and worked as a Chief Financial Officer of a public energy company or a sales executive who led the business development department of a large company likely do not possess the same academic training of a doctorate degree like other academics; however, such professional faculty may possess relevant experience and skills to teach accounting or marketing, respectively, to post-secondary students effectively. Our analysis identifies recurring recommendations for faculty to incorporate into their teaching dossiers, encompassing elements such as summaries of teaching responsibilities, documentation of course development or modification, creation of instructional materials, ongoing pedagogical improvement endeavors, outstanding teaching materials, articulation of teaching philosophies, and evidence of collegial collaboration and support. Our findings reveal a disconnect in understanding and recognizing the significance of teaching and teaching dossiers. In light of these observations, this paper outlines the limitations inherent in the current system. It suggests promising avenues for future research within this domain. We aim to foster a more equitable and supportive environment for all faculty members engaged in the complex task of academic teaching.

1 Introduction

Regardless of their diverse backgrounds and academic trajectories, faculty members in the pre-tenure stage often perceive the tenure application procedure as stressful (Hirschkorn, 2010). The process of academic maturation within the confines of academia, which encompasses the seamless progression from undergraduate and graduate studies to the attainment of a Doctorate, followed by placement in post-doctoral and faculty roles, yields a form of natural socialization. We refer to these types of academics as traditional academics as their skills have been developed through a classic academic path. Such a developmental trajectory for traditional academics tends to produce a heightened acumen regarding the required components within a comprehensive teaching dossier. In contrast, practitioners without formal scholarly training (e.g., Chartered Professional Accountants and sales professionals) working in academia, herein referred to as professional faculty, may lack familiarity with these expectations.

University faculty may be hired with no teaching experience (e.g., Dalhousie University, 2021; John Molson School of Business, 2023) and then given little to no formal training on becoming proficient teachers (Robert and Carlsen, 2017). Nonetheless, all educators engaged in instructional roles must substantiate their pedagogical efficacy when seeking advancement in the academic hierarchy, such as promotion or tenure. Notably, Canadian institutions of higher learning generally mandate possessing a doctoral degree as a prerequisite for faculty appointments (Government of Canada, 2023). In contrast, the supply of doctorally qualified applicants for some professional faculty continues to fall short of the demand [i.e., accounting faculty (AACSB, 2020)]. Instead of requiring a doctoral degree as a prerequisite, certain academic institutions may consider a combination of master’s or bachelor’s degrees and substantial senior-level professional experience within the relevant field as an acceptable qualification (AACSB, 2020). As an illustrative instance, academic departments specializing in business education with a distinct emphasis on equipping students for imminent entry into the professional workforce occasionally engage faculty members in accounting who may lack the conventional doctoral credential. In specific scenarios, these faculty appointments may not even necessitate possession of a master’s degree, provided that candidates possess a relevant bachelor’s degree, hold the esteemed Chartered Professional Accountant designation, and possess extensive senior-level practical experience within the realm of the accounting discipline (AACSB, 2020).

Accounting faculty contribute to teaching, research or other professional activities such as consulting, and service (Bédard and Dodds, 1994). In the context of the evolution of the accounting profession, it is important to acknowledge that the entities responsible for assessing the scholarly contributions of accounting faculty may not possess a commensurate level of familiarity with the contemporary trends that characterize accounting education. Furthermore, individuals who have devoted their scholarly efforts to specialized domains, such as accounting curriculum development, may encounter a distinct disadvantage when pursuing advancements in academic rank, including promotions and tenure considerations (Chen, 2017). Notably, the professionals assuming teaching roles within university settings without possessing doctoral or master’s qualifications extends beyond accounting, management, and business. However, the focus of this paper is on professional faculty who are classroom, not clinical or lab, teachers. As such, we limit our subsequent analysis and discussion to professional accounting, management, and business professional faculty.

A definitive and universally recognized criterion for discerning TE remains absent in the Canadian post-secondary education landscape. Notwithstanding the abundance of advisory documents present in the realm of gray literature, designed to offer guidance to educators from diverse disciplinary backgrounds in constructing their teaching dossiers, the onus largely rests upon incumbent and aspiring professional faculty members to navigate this multifarious landscape. They must either diligently scrutinize this literature or make a somewhat arbitrary selection, aspiring that their chosen framework aligns with the exacting expectations of their respective academic institutions, while Seldin et al. (2010) recommend discussing teaching dossier categories with the department head.

A systematic examination and appraisal of the extant gray literature guidance concerning the construction of teaching dossiers have been notably absent. This paper addresses this gap in the scholarly discourse by responding to the overarching inquiry: “What evidentiary indicators of teaching effectiveness (TE) should professional faculty incorporate within their teaching dossiers?” To address this overarching question, the following research queries will be examined:

RQ1a: Which schools hire professional faculty?

RQ1b: Of the schools in RQ1a, what categories of evidence are most recommended in their teaching dossier guidance?

This paper aims to offer several notable contributions to the existing body of knowledge. Firstly, it furnishes a comprehensive analysis of Canadian top-tier, U-15 (U15 Group of Canadian Research Universities, 2022) universities’ practices in recruiting faculty members possessing professional qualifications. Secondly, it distils the most common features of teaching dossiers as outlined in the gray literature, which typically serves as a valuable source of guidance for individuals developing teaching dossiers. Lastly, this paper presents practical recommendations on how faculty members with professional backgrounds can leverage their teaching achievements to construct a substantiated teaching dossier.

We structure the remaining paper as follows. Section two commences with a comprehensive exploration of diverse roles within academic institutions, encompassing an examination of TE and a thorough analysis of extant scholarly literature and methodologies attempting to demonstrate TE within the gambit of teaching dossier guidance. Section three delves into the design, execution, and data analysis pertaining to extant guidance on compiling and presenting teaching dossiers. Section four presents the empirical findings, while section five discusses them. This paper ends with a conclusion where we assist professional faculty members in substantiating their TE, thus facilitating their appointment, reappointment, tenure, and, ultimately, promotion.

2 Background

2.1 Faculty roles

In higher education, faculty members lacking a doctorate degree may find their performance assessments oriented less toward their capacity for generating and proliferating original research within their field. Instead, the evaluation process places a more pronounced emphasis on their aptitude for imparting knowledge and fostering learning among their students (Dalhousie University, 2021; Oler et al., 2022). In evaluating the teaching prowess of current or prospective faculty members, it is paramount for these educators to adhere to established best practices when compiling their teaching dossiers. Therefore, exploring what precisely constitutes these best practices and demonstrating a comprehensive teaching dossier becomes imperative.

In the realm of academic research, the U15 Group of Canadian Research Schools (hereafter referred to as “U15”) comprises a consortium of esteemed universities committed to addressing the most significant societal and global challenges (U15 Group of Canadian Research Universities, 2022). The U15 members are the University of Alberta, the University of British Columbia, the University of Calgary, Dalhousie University, Universite Laval, the University of Manitoba, McGill University, McMaster University, Universite de Montreal, the University of Ottawa, Queens University, the University of Saskatchewan, the University of Toronto, the University of Waterloo, and Western University (ibid). Within the U15 consortium, each member institution boasts a school of business, and in response to a dearth of academically qualified accounting educators, these institutions may occasionally engage individuals with professional qualifications. It is worth noting that the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB, 2022) underscores this aspect on its official website:

[They] are considered to be the best business schools in the world. […] AACSB-accredited schools have better programs, better faculty, better students with higher overall GPAs, more international students, more employers that recruit from them, and graduates that receive better salaries (n.d.).

U15 institutions that boast AACSB accreditation have the potential to harness a dual strength, by enlisting both highly prolific researchers and exceptionally skilled educators. It is important to recognize that not all educators excel as prominent researchers, leading to a growing imperative for universities to broaden their spectrum of tenure-track faculty positions. This expansion initiative is primarily geared toward the recruitment of professionals who may not hold doctoral credentials, or, in cases where they do, may not be actively engaged in research pursuits. Within the framework of AACSB standards (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business [AACSB], 2021), these positions are commonly designated as Instructional Practitioners (IP) or Practice Academics (PA), while their counterparts with doctorate degrees are often referred to as Scholarly Practitioners (SP) or Scholarly Academics (SA). The terms required to separate research-active from non-research-active faculty and those who possess a doctorate are AACSB guidelines. The overlap between U15 and AACSB schools, which introduces non-research-focused faculty (sometimes referred to as either “career stream” or “teaching-focused” faculty), typically results in an emphasis placed on the employees’ teaching abilities. Nevertheless, there are often no standard guidelines for what constitutes teaching excellence, nor for how to build one’s teaching dossier for appointment, reappointment, tenure, and/or promotion.

This scholarly endeavor centers its attention on academic institutions that reside at the confluence of U15 and AACSB qualifications. It is worth noting that while the scope of this investigation primarily encompasses business schools within these select institutions, the insights gleaned herein may be useful to academic disciplines outside of business schools. This is because the overarching aim is to delineate, nurture, and refine the pedagogical best practices, which have relevance and applicability to faculty members across diverse academic disciplines.

2.2 Teaching effectiveness

Institutions may choose to measure TE through five measures (Mazandarani and Troudi, 2022): student learning outcomes (Fernández-García et al., 2021; Tuma, 2021), peer evaluation (Adnot et al., 2017), instructor self-evaluation (e.g., Brand, 1980; Klassen et al., 2021; Rupp and Susann Becker, 2021), observation (e.g., Cinnamon et al., 2021; Granström et al., 2023), and student evaluation of TE (SETE, (e.g., Gallagher, 2000; Griffith and Sovero, 2021; Pan et al., 2021; Sadeghi et al., 2021). However, as noted by Taylor and Thion (2023), TE is a construct that is rarely defined in the literature, and when it is, it is measured typically by either SETE or student objective measures. As such, our focus when discussing TE hereafter will focus primarily on SETE and student objective measures.

SETE (i.e., student ratings of instruction surveys) presents the opportunity for the misalignment of incentives. Griffith and Sovero (2021) found that while there were no different grades awarded to students by untenured (versus tenured) male professors, higher grades were awarded by untenured female professors. In the realm of academic analysis, it is plausible that the elevated academic achievements observed could potentially be attributed to the pedagogical excellence exhibited by female professors who have yet to attain tenure status (ibid). Consequently, this might have led to improved academic outcomes among their students. In addition to possible grade inflection quid pro quo, SETEs are poor evaluations of TE as they are impacted by several biases including gender (Boring, 2017), cultural (Fan et al., 2019), and the availability of non-course incentives like cookies at the time of SETE completion (Hessler et al., 2018). At the very least, it is essential to acknowledge the existence of a perceived conflict of interest within the context of professors who evaluate student performance while simultaneously being subject to those same (potentially biased) students’ evaluations, which can profoundly impact a professor’s professional trajectory and livelihood. As recommended by Linse (2017) faculty (committees) and administrators need to be aware of the body of SETE research that outlines the shortcomings to appropriate utilize such data.

There are a variety of student objective measures, including scores on an objective test (Yunker, 1983), final exam scores (Koon and Murray, 1995), student achievement of learning outcomes (Hanushek et al., 2004), student grades (Ni, 2013), and pre-and post-tests (Cortázar et al., 2021).

While such objective measures may appear to be free of student bias, student-centric methodologies strive to mitigate the potential influence of a reciprocal relationship between instructors and students, wherein better grades might engender a more favorable perception of teaching efficacy. Yunker (1983) employed average mean scores as a method for ascertaining objective assessment, and through this methodology, they succeeded in disentangling class means from student-specific variables. Consequently, this allowed for an assessment of TE to transpire independently of the immediate influence of student perceptions. Nevertheless, this presupposes that objective evaluations can genuinely maintain their objectivity, devoid of any manipulation orchestrated directly by educators. This potential for manipulation introduces an intriguing inquiry regarding its implications for the quality of education as perceived by students, particularly when TE is gauged predominantly by objective metrics such as standardized test scores. Regardless, it is imperative to acknowledge that even these impartial assessment approaches are not immune to challenges when appraising an educator’s TE.

Taylor and Thion (2023) note that TE has two dimensions: student-focused (outcome) and educator-focused (input). Both SETE and student objective are measurements for the student-focused dimension of TE, while peer-review, self-assessment, and administrator evaluation are measurements for the educator-focused dimension of TE, as they all focus on the “input” efforts of educators attempting to demonstrate TE (ibid). Notably, of the educator-focused measures, Taylor and Thion found only administrator evaluation was the sole measurement of SETE, where peer-review and self-assessment were done in combination with SETE, student objective measures (2023).

As such, one strategy for academics to demonstrate TE is to remove the impact of a single evaluative (and potentially punitive) measure. This process is accomplished through the compilation of their instructional background, drawing upon a diverse array of resources, including as Taylor and Thion (2023) suggest, by using multiple measures depending on the focus (dimension) of TE.

2.3 Teaching dossier

Teaching dossiers, otherwise referred to as scholarly dossiers, educational portfolios, and teaching portfolios, contain evidence of a teacher’s teaching efforts. The contents of such teaching dossiers vary, while the lack of analysis of such variance is the subject of this paper.

The lack of standardized guidance on how teachers may demonstrate TE via their teaching dossiers has implications to academics and their institutions. Bailey et al. (2016) discovered that the teaching expectations placed upon newly minted doctoral graduates in the field of social work exhibited a notable absence of comprehensive formalized pedagogical training within the framework of their postgraduate education. This deficiency in structured teacher preparation was observed to hinder the cultivation of these individuals as effective educators within the sphere of social work, thus posing potential challenges to their subsequent professional development in academia. This observation assumes particular significance in light of the prevailing norm within academia, wherein aspiring junior faculty are typically expected to possess a foundation of teaching experience as they embark on their academic careers, the lack of formal preparation for educators entering the higher education field continues to present an issue. Chapnick (2009) provides a general list of elements for a teaching dossier while defining such a collection as a “professional document that provides evidence of your teaching beliefs, experiences, and abilities.” As well, some scholarly resources exist on the creation and maintenance teaching dossiers (e.g., Brewer-Deluce and Gibson, 2017; Knapper, 1998).

Seldin et al. (2010) provided one of the more robust resources to create a teaching portfolio (dossier). They begin their book by outlining what it is and why variances in expectations of teaching dossier readers may vary. While they discuss the nuances of clinical educator dossiers, their discussion of similar professional faculty notes are not addressed, with mentions of “professional” limited to the section that discusses both professional development and service. Nonetheless, Seldin et al. (2010) guide is a comprehensive source which includes and provides details as to what many of the suggested included elements should be. For example, they suggest including a teaching philosophy, state what it is and some guiding questions on how to craft one. However, they do not provide examples or best practices of what such teaching philosophy statements could look like. While there are other articles that research teaching dossiers (McFadyen, 1997; Burnap et al., 2010; Gravestock, 2011), to the best of our knowledge, there appears to be no peer-reviewed scholarly resources using documentary research to examine teaching dossiers.

Similarly, despite the availability of gray-literature for teaching dossier, a gap remains for academics whose teaching accomplishments may not fit a traditional teaching dossier (Wiebe and Fels, 2010). In the context of assembling teaching dossiers, the separation between appropriate materials for inclusion amongst the scholarly literature is lacking. For example, when accounting educators Calderón and Stratopoulos (2020) discussed the level of knowledge required for accountants about blockchain, the authors demonstrated ability through an accessible case study of Listerine, a peer-reviewed journal publication. Calderón and Stratopoulos could have also used the same case of Listerine to teach their accounting students about blockchain. Incorporating this case study, which presents an innovative accounting pedagogical approach, into their teaching dossiers could be deemed a prudent endeavor. Although this study does not investigate into the substantive aspects of a research dossier, it does highlight the most commonly recommended teaching dossier components.

To supplement the peer-reviewed literature, publications hosted by university websites may be used. University of Calgary’s website hosts the comprehensive Guide for Providing Evidence of Teaching (Kenny et al., 2018) that outlines examples of teaching activities and examples of evidence to support such activities. Given the potential for depth amongst university website hosted resources for the demonstration of teaching effectiveness, this study focuses on the examination of university teaching dossier guidance.

3 Materials and methods

To address our research questions (RQs), we conducted a comprehensive examination of teaching dossier guidance materials from prominent Canadian universities that have made faculty appointments from non-conventional (professional) backgrounds. The methodological framework for our documentary research (Martin, 2018) unfolded through distinct phases.

Initially, in Phase 1, we selected our cohort of target institutions. Subsequently, in Phase 2, we ascertained which among our chosen institutions had a teaching-centric approach in their faculty roles. Finally, we conducted an evaluation by examining and categorizing the teaching dossier guidelines, aimed at identifying and categorizing teaching dossier components and their relative prevalence within the overarching context of teaching dossier guidance provided by institutions offering teaching-focused tenured faculty (TTF) positions.

3.1 Phase 1: determining target schools

The primary objective of Phase 1 is to establish the alignment of universities with the prescribed criteria of a designated institution, which entails membership in the U15 group and current accreditation by AACSB. To achieve this, our approach involved a systematic process wherein we leveraged the U15’s official website to identify the preeminent research-focused universities in Canada. Subsequently, a cross-referencing exercise was conducted by comparing this list against the AACSB’s official website. This enabled us to discern which of the prominent research-oriented institutions within Canada also held AACSB accreditation.

3.2 Phase 2: identifying target schools with TTF

In Phase 2 of our research, our objective is to determine which among our designated targets exhibit indications of a faculty role that qualifies for tenure on substantive grounds, yet does not necessitate the production of discipline-specific research outputs. Our analytical approach involves an examination of pertinent documents, including faculty association and/or union guidelines specific to each of the targeted educational institutions. This examination is undertaken to discern the presence of a tenure pathway that predominantly emphasizes teaching over research, as opposed to the more conventional research-centric tenure tracks.

It is noteworthy that these target institutions may offer a distinct “stream” running parallel to the conventional research-oriented professoriate tenure tracks. While these institutions may employ the same tenure track, they often articulate language that accommodates non-research activities as valid contributions toward fulfilling the discipline-related requirements, which are typically met through research endeavors.

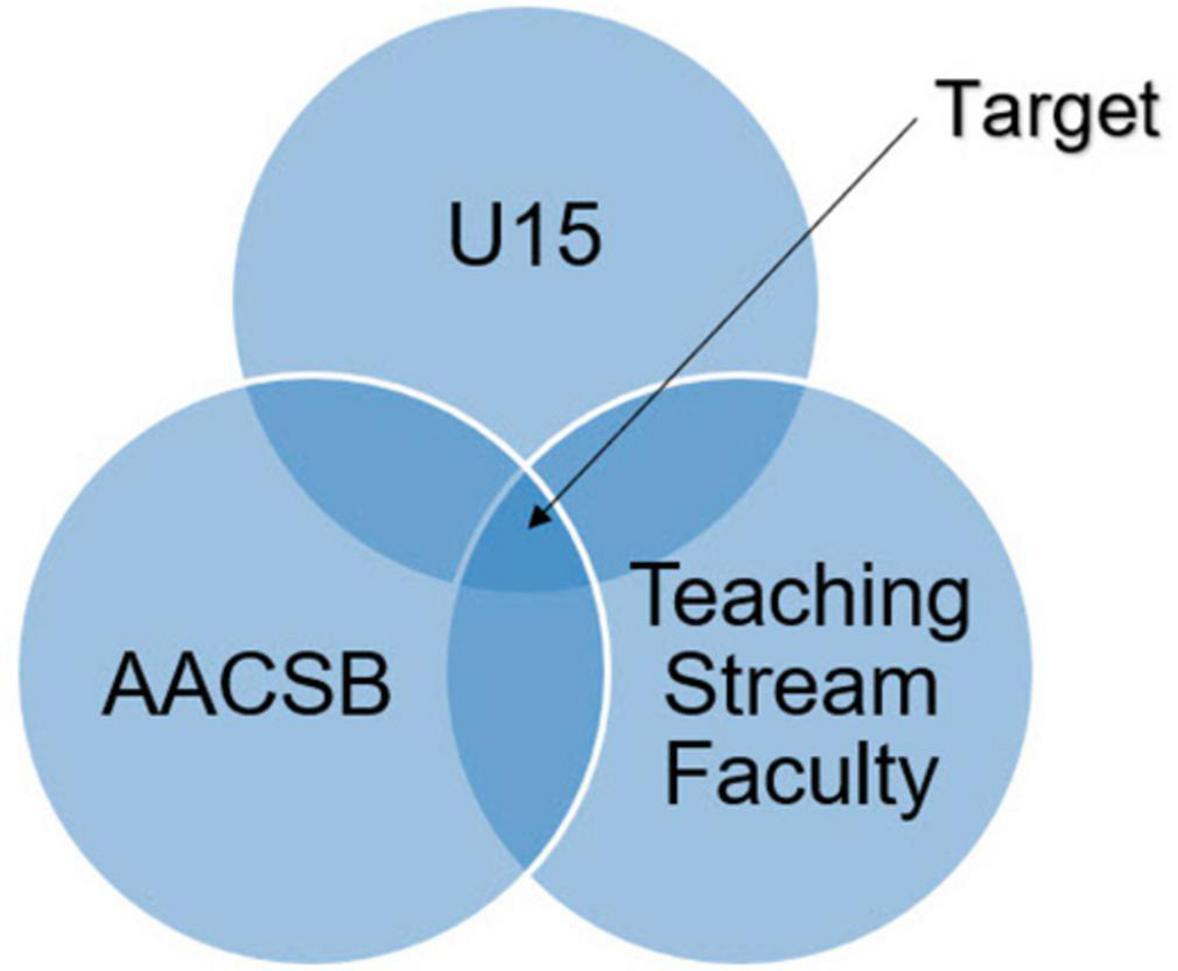

Figure 1 provides a visual representation that summarizes our TTF. The TTF represents the overlap of a “target” group of institutions that have three distinguishing characteristics. First, they are all institutions that fall within the category of top Canadian research-producing universities (commonly referred to as the U15 group). Second, they are all institutions d whose business schools, accordingly to AACSB standards, rank within the top five percent globally. Third, we further delineated these institutions that meet the first two criterion, are U15 and AACSB institutions, by selecting only those institutions that also offer tenure-track faculty positions tailored to emphasize teaching. Thus, the TTF institutions are distinct from their research-active counterparts.

3.3 Phase 3: evaluating teaching dossier guidelines

The focus of Phase 3 is to conduct an extensive evaluation of the thematic categories within the teaching dossier guidance intended for educational institutions employing TTF members. This phase involved a comprehensive examination of teaching dossier guidance materials for TTF positions. Here we analyzed of all pertinent guidance documents, followed by a systematic categorization of recurrent themes and directives therein. To culminate this phase, we compiled a comprehensive tally of the frequency with which each thematic element appeared within headings or specific categories.

4 Results

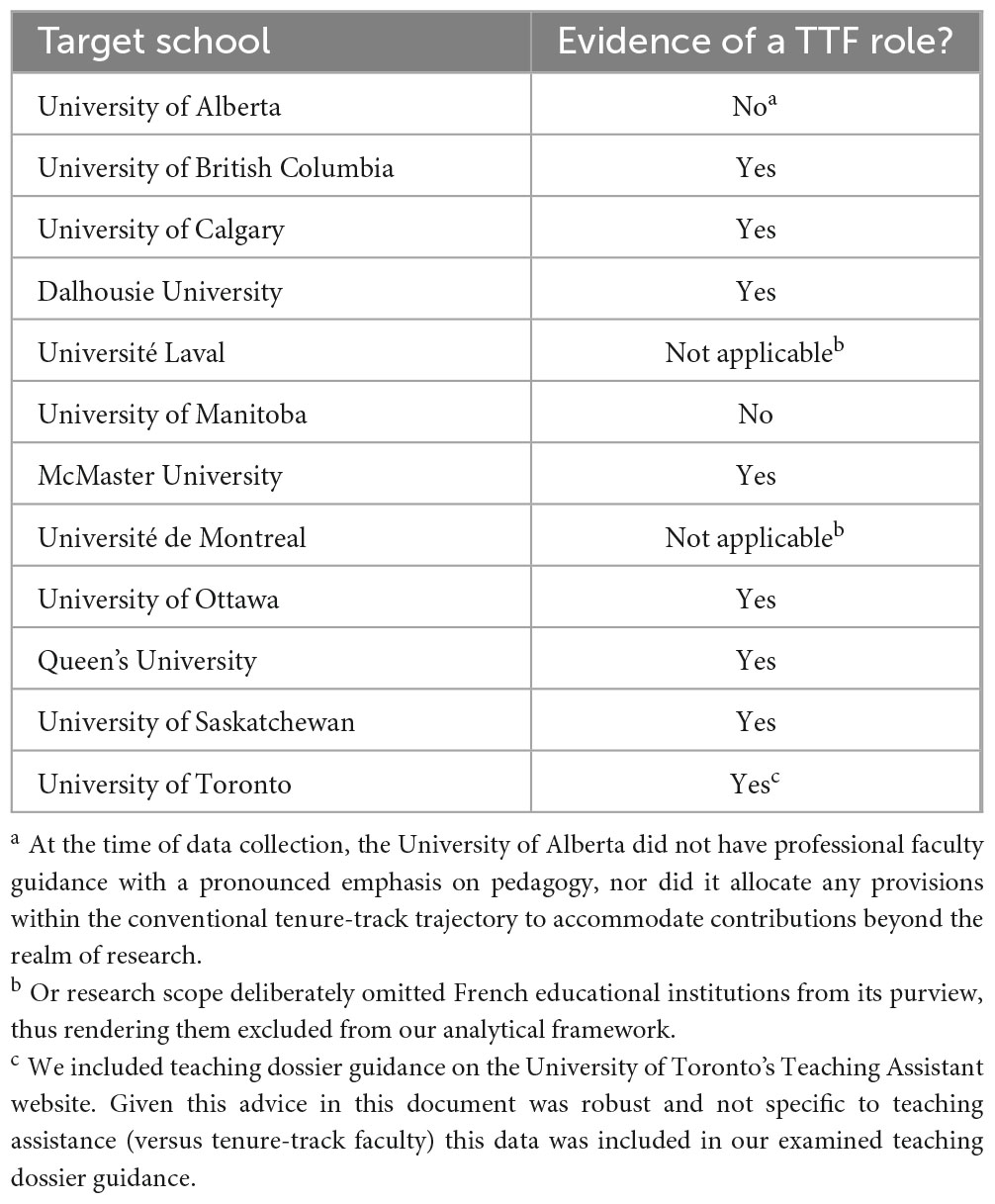

In the context of the U15 consortium, comprising fifteen universities, our study identified that twelve universities conformed to our defined criteria for a target institution, specifically those that are members of the U15 consortium and possess accreditation from AACSB. Subsequently, our investigation delved into the institutional documentation, such as faculty and union guidance, to ascertain alignment with a TTF, denoted as “Yes” in Table 1. This scrutiny yielded a subset of eight universities that met our criteria as “target” institutions, as they exhibited tangible evidence within their faculty and union guidelines that substantiates an emphasis on a teaching-centric faculty role. Part 3 of our analysis was dedicated to a comprehensive examination of these eight identified institutions, which represent the focal point of our study on teaching-focused target universities.

In Note 1, it is noteworthy that the educational institution under examination failed to furnish compelling substantiation in favor of a tenured equivalent faculty track with a pronounced emphasis on pedagogy, nor did it allocate any provisions within the conventional tenure-track trajectory to accommodate contributions beyond the realm of research.

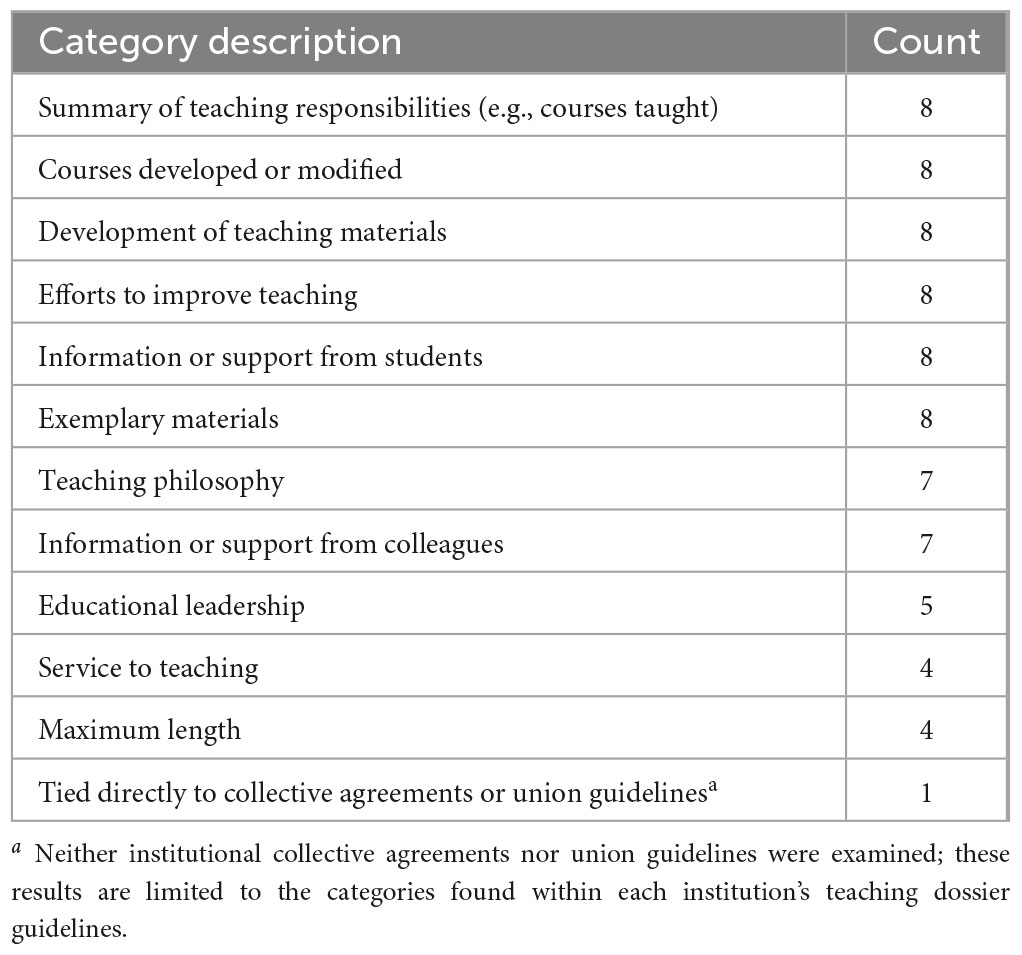

Table 2 summarizes the frequency category mentions within the TTF’s teaching dossier guidelines.1

There exists a strong consensus amongst TTF teaching dossier guidelines for eight categories, with mixed guidance for the remaining five categories. Subsequent discussion will provide a suggested implementation plan for current and prospective faculty members to structure their teaching dossier.

5 Discussion

Consistent with at least seven out of eight TTF guidelines in Table 2, we suggest teaching dossiers include, at a minimum, the following categories2 in the teaching dossier:

• Summary of teaching responsibilities

• Courses developed or modified

• Development of teaching materials

• Efforts to improve teaching

• Information or support from students

• Exemplary materials

• Teaching philosophy

• Information or support from colleagues

Table 2 summarizes a divergence of opinion exists regarding the incorporation or exclusion of elements related to educational leadership within one’s teaching dossier. A similar lack of consensus was identified concerning the inclusion of (internal) service activities related to teaching, such as participation in program committees or attendance at disciplinary hearings. Given this prevailing lack of agreement, we propose that readers initially consult external guidelines, such as faculty agreements or job posting descriptions, or consult their department head (Seldin et al., 2010) to ascertain whether these documents specify the inclusion or exclusion of such elements within or external to their teaching dossier. In the absence of specific external guidance, individuals should evaluate the comprehensiveness of their teaching dossier, its length, and the depth and quality of educational leadership and internal service components they intend to incorporate.

Following an analysis of the available material, when constructing a teaching dossier, we recommend striving for brevity, where feasible, as the dossier is a dynamic document subject to periodic updates. This approach may help mitigate the need for extensive revisions in subsequent years. Notably, one institution aligned its teaching dossier guidelines with its collective agreement guidelines. Consequently, we advise current or prospective faculty to consult their institution-specific teaching guidelines for precise instructions.

While all the TTF guidelines emphasize creating and cultivating a teaching dossier, three resources stand out:

• Dalhousie University’s teaching and learning website offers guidance, The Teaching Dossier Template (Dalhousie University, 2024), adapted from Kenny et al.’s (2018) Teaching Philosophies and Teaching Dossiers Guide is a happy medium of the above two, with the unique feature of presenting it within a starting template. This fillable Microsoft Word template has step-by-step instructions on how to complete it; once users have completed the instructions, they may delete the guidance. What remains would be the user’s teaching dossier.

• McMaster University’s (CAUT, 2018) CAUT Teaching Dossier is a comprehensive resource that provides background into what a teaching dossier is, its administrative use, and in-depth explanation and examples of categories within a teaching dossier.

• The University of Ottawa’s teaching dossier template3 provides a comprehensive template that educators may update with their information to provide a comprehensive teaching dossier in a professional format.

U15 institutions in Canada represent the top five percent of research-producing universities in the country (U15 Group of Canadian Research Universities, 2022), whereas AACSB-accredited institutions worldwide are considered the top five percent among business schools. Importantly, AACSB-accredited institutions do not uniformly mandate that all faculty possess doctoral degrees or engage in active research (AACSB, 2020). Consequently, a teaching dossier demonstrating TE must encompass both an educator’s teaching activities and their unique strengths. This comprehensive approach ensures that current and prospective professional faculty members undergo a thorough and accurate evaluation by university hiring and review committees.

Historically, aspiring and current faculty members demonstrating TE had limited access to specific institutional teaching dossier guidelines. While some scholarly teaching dossier resources exist (e.g., Knapper, 1998; Brewer-Deluce and Gibson, 2017), to our knowledge, there has yet to be a peer-reviewed scholarly publication with documentary research or review of teaching dossier resources. As such, aspiring and current faculty members may resort to manually compiling scattered information from various sources, such as internet searches. Our study marks a pioneering effort in systematically evaluating and summarizing the most prevalent guidelines from major universities that maintain faculty roles for professionally qualified educators.

It is worth noting that distinct guidelines may exist for demonstrating TE during the hiring process as opposed to the reappointment, tenure, and promotion processes. One piece of anecdotal data came from one author’s experience where her U15 institution mandated solely the inclusion of student statements of teaching evaluations for the initial hiring application but necessitated a comprehensive teaching dossier two years later for reappointment. Such distinctions can introduce time constraints, potentially catching professional faculty members unaware until they approach the reappointment deadline. Consequently, explicit and well-defined guidance for a somewhat open-ended requirement—submitting a teaching dossier to demonstrate TE—can be crucial, as it might otherwise lead to undue stress. Many educators excel in their roles as effective teachers, but it is increasingly essential to provide concrete evidence of this effectiveness.

Similar to a traditional academic, professional faculty members may publish peer-reviewed empirical research (e.g., Taylor et al., 2024) engage in large-scale pedagogical research efforts (Wood et al., 2023, e.g.) publish peer-reviewed teaching case studies (e.g., Taylor and McGregor, 2023; Taylor et al., 2023c), simulations (e.g., Taylor et al., 2023a), and textbook chapters (Taylor et al., 2022). Thus demonstrating professional faculty trained outside of academia may publish in similar venues as traditional academics, though with a focus on what Boyer (1990) classified as the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. When creating their teaching dossiers, professional faculty with traditional backgrounds may include such efforts as development of teaching materials (e.g., teaching case studies, simulations, and textbook chapters), efforts to improve teaching (e.g., pedagogical research efforts), and information of support from (traditional academic) colleagues who, for example, collaborate with professional faculty members to utilize their professional knowledge to publish peer-reviewed empirical research.

Furthermore, professional faculty members often engage with the community and the university in ways that traditional academics might not. For example, professional faculty may participate or spearhead a substantial annual project involving the recruitment, training, and evaluation of educators for a large-scale teaching initiative, (CPA Canada, 2024), and co-author a professional education book (e.g., Taylor et al., 2023b) or sport-specific pedagogical guide (Presley and Taylor, 2024). If appropriately documented, such activities could be considered a form of educational leadership and contribute significantly to one’s teaching dossier. However, inadequate documentation may lead review committee members to misconstrue these efforts as consulting or activities falling outside the faculty member’s role, potentially jeopardizing their prospects for hiring, reappointment, tenure, and promotion. Therefore, there is a pressing need for clear guidelines and documentation to ensure equitable evaluation of professional faculty members.

It is incumbent upon us to recognize the constraints of this study. Primarily, we acknowledge that our investigation does not address the frequency with which universities utilize their publicly available teaching guidelines in making hiring and retention determinations. Furthermore, we cannot definitively ascertain whether faculty members who rely on their university’s guidance to showcase their TE encounter adverse consequences. Similarly, although universities may advocate certain teaching best practices, our analysis does not delve into whether each institution mandates faculty or potential faculty members to submit a teaching dossier for assessing TE. Lastly, we have not explored potential compensatory measures that may mitigate subpar teaching performance or an incomplete dossier of teaching activities. For instance, a traditional academic with a robust record of research publications may offset less-than-average teaching performance (Gentry and Stokes, 2015).

Consequently, future research endeavors should aim to address these limitations and expand the analysis of teaching guidance to encompass highly ranked international universities beyond Canada’s borders. Collaborative efforts between professional associations representing their members (e.g., Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada) and traditional higher education institutions could yield valuable guidance for members engaged in professional education, both aspirants and current faculty members. Such guidance could help these professional faculty members demonstrate TE with compelling evidence within their teaching dossiers. Establishing this link between a profession and the higher education institutions serving it could enhance the caliber of educators for both parties, potentially benefiting the quality of graduates as well.

Moreover, forthcoming research could delve into the strategies employed by aspiring and current professional faculty members to showcase TE and examine any detrimental repercussions they may face in the absence of representation or guidance from their professional associations in the realm of traditional higher education. We advocate for extending this study to undertake a more comprehensive analysis. Investigating the experiences of professional faculty members who meet most recommended criteria but face unsuccessful applications and reappointments could yield insights into additional resources that could bolster their ability to demonstrate TE.

Our findings suggest that professional faculty should, at a minimum, include the most frequently recommended categories when creating their teaching dossiers. Those categories are a summary of teaching responsibilities, courses developed or modified, development of teaching materials, efforts to improve teaching, information or support from students, exemplary materials, statement of teaching philosophy, and information or support from colleagues. By including these elements, professional faculty should be able to demonstrate TE and thus attain tenure and promotion. Therefore, continuing to contribute to a diverse academic environment for accounting, management, and business students.

6 Conclusion

Hiring and promotion committees typically mandate the provision of evidence demonstrating TE; however, as discussed in this article, there appears to be an absence of standardized or consistent guidelines on how faculty members can effectively convey this evidence. Furthermore, these committees may lack familiarity with the relevant experiences held by professionally qualified faculty members (Chen, 2017), and conversely, professional faculty members may not be well-versed in the nuanced and comprehensive documentation required to satisfy the discerning criteria employed by these evaluation committees. In contrast to traditionally trained academics, who may be socialized with an understanding of the specific evidentiary requirements expected by these committees, professional faculty members may lack this same level of knowledge. The failure to adequately demonstrate effectiveness across all dimensions, including teaching, is likely to impede the prospects of both aspiring and current faculty members in securing or maintaining their positions.

Professional faculty members may hold pertinent and ongoing leadership roles in education, and their service activities often revolve around committees and working groups focused on teaching. Yet, the classification of such leadership and service roles can vary among different hiring and promotion committees; some may categorize them as teaching, while others might regard them as service. Anecdotally, we have observed that although guidelines exist for hiring and tenure and promotion committees, the responsibility often falls upon the applicant to effectively communicate their proficiency in each required domain. Consequently, an applicant may have fulfilled all teaching, research, and professional duties, as well as service roles, yet fail to convey this effectively through their cover letter or- interviews with the committee, resulting in an unsuccessful outcome despite possessing all the requisite qualifications.

Through our research, we highlight the most recommended components to be included in a teaching dossier, as advised by major universities employing professional faculty. Additionally, we present exemplars and templates that faculty members may employ when constructing their teaching dossiers. Our recommendations are designed to empower professional faculty members to effectively demonstrate their TE, ultimately enhancing their prospects for appointment, reappointment, tenure, and/or promotion.

Author contributions

ST: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. SC: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank professors and peers of Queen’s University Professor Master of Education program for their feedback as an earlier version of this research was submitted as ST final master’s project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ The results are limited to what is found in the TTF’s teaching dossier guidelines and does not include analysis of other internal institutional documents such as tenure and promotion guidelines.

- ^ We have not defined beyond the recommended categories to include in a teaching dossier, as there can be many discipline-specific variations of what could be included in each category.

- ^ https://saea-tlss.uottawa.ca/images/Teaching_Dossier/Teaching_Dossier_-_Template_2023_rev.docx

References

AACSB (2022). 5 Things Business School Rankings Don’t Tell You. Available online at: https://www.aacsb.edu/insights/articles/2022/06/5-things-business-school-rankings-dont-tell-you (accessed September. 14, 2023).

Adnot, M., Dee, T., Katz, V., and Wyckoff, J. (2017). Teacher turnover, teacher quality, and student achievement in DCPS. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 39, 54–76. doi: 10.3102/0162373716663646

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business [AACSB] (2021). 2020 guiding principles and standards for AACSB business accreditation. Tampa, FL: Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business.

Bailey, S. N., Bogossian, A., and Akesson, B. (2016). Starting where we’re at: developing a student-led doctoral teaching group. Transformations 26, 74–88. doi: 10.5325/trajincschped.26.1.0074

Bédard, J., and Dodds, C. (1994). The University accounting professoriate in Canada. Contemp. Account. Res. 10, 75–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1911-3846.1994.tb00422.x

Boring, A. (2017). Gender Biases in Student Evaluations of Teaching. J. Public Econom. 145, 27–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2016.11.006

Boyer, E. (1990). Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Available online at: https://www.umces.edu/sites/default/files/al/pdfs/BoyerScholarshipReconsidered.pdf (accessed September. 14, 2023).

Brewer-Deluce, D., and Gibson, C. J. (2017). Teaching matters: Developing teaching dossiers to showcase teaching success and competency. Teach. Innov. Proj. 7, 3723.

Burnap, C. A., Kohut, G. F., and Yon, M. G. (2010). Teaching dossier documents: A comparison of importance by major stakeholders. J. Effect. Teach. 10, 38–50.

Calderón, J., and Stratopoulos, T. C. (2020). What Accountants Need to Know about Blockchain. Account. Persp. 19, 303–323. doi: 10.1111/1911-3838.12240

CAUT (2018). Caut-Teaching-Dossier_2018-11_online_version.Pdf. Available online at: https://www.caut.ca/sites/default/files/caut-teaching-dossier_2018-11_online_version.pdf (accessed January. 22, 2024).

Chapnick, A. (2009). How to Prepare a Teaching Dossier. University Affairs (blog). Available online at: https://www.universityaffairs.ca/career-advice/career-advice-article/how-to-prepare-a-teaching-dossier/ (accessed November 9, 2009).

Chen, T. T. Y. (2017). Have improvements been made to accounting pedagogy in the new millennium: A guide for accounting academics. J. Account. Finan. 17, 26–35.

Cinnamon, S. A., Rivera, M. O., and Dial Sellers, H. K. (2021). Teaching disciplinary literacy through historical inquiry: Training teachers in disciplinary literacy and historical inquiry instructional practices. J. Soc. Stud. Res. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.jssr.2021.03.001

Cortázar, C., Nussbaum, M., Harcha, J., Alvares, D., López, F., Goñi, J., et al. (2021). Promoting critical thinking in an online, project-based course. Comput. Hum. Behav. 119:106705. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106705

CPA Canada (2024). “Become a CPA PEP Capstone 2 National Marking Centre Marker. Available online at: https://www.cpacanada.ca/become-a-cpa/cpa-certification-program-evaluation/become-a-capstone-2-marker (accessed January 25, 2024).

Dalhousie University (2021). Job Posting: Lecturer or Assistant Professor (Probationary Tenure-track). Available online at: https://www.dal.ca/faculty/management/school-of-information-management/news-events/news/2021/11/12/job_posting__lecturer_or_assistant_professor__probationary_tenure_track_.html (accessed January 25, 2024).

Dalhousie University (2024). Teaching Dossier. Available online at: https://www.dal.ca/dept/clt/programs/Dossiers.html (accessed January 21, 2024).

Fan, Y., Shepherd, L., Slavich, E., Waters, D., Stone, M., Abel, R., et al. (2019). Gender and cultural bias in student evaluations: Why representation matters. PLoS One 14:e0209749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209749

Fernández-García, C.-M., Rodríguez-Álvarez, M., and Viñuela-Hernández, M. (2021). University students and their perception of teaching effectiveness. Effects on Students’ Engagement. Rev. Psicodid. 26, 62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.psicoe.2020.11.006

Gallagher, T. J. (2000). Embracing student evaluations of teaching: A case study. Teach. Sociol. 28, 140–147. doi: 10.2307/1319261

Gentry, R., and Stokes, D. (2015). Strategies for professors who service the University to earn tenure and promotion. Res. Higher Educ. J. 29, 1–13.

Government of Canada (2023). University Professor in Canada | Job Requirements - Job Bank. Toronto, ON: Government of Canada.

Granström, M., Kikas, E., and Eisenschmidt, E. (2023). Classroom observations: How do teachers teach learning strategies?” Front. Educ. 8:1119519. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1119519

Gravestock, P. (2011). Does Teaching Matter? The Role of Teaching Evaluation in Tenure Policies at Selected Canadian Universities. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto.

Griffith, A. L., and Sovero, V. (2021). Under Pressure: How faculty gender and contract uncertainty impact students’. Grades Econ. Educ. Rev. 83:102126. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2021.102126

Hanushek, E. A., Rivkin, S. G., Rothstein, R., and Podgursky, M. (2004). How to improve the supply of high-quality teachers. Brook. Papers Educ. Policy 7, 7–44. doi: 10.1353/pep.2004.0001

Hessler, M., Pöpping, D. M., Hollstein, H., Ohlenburg, H., Arnemann, P., Massoth, C., et al. (2018). Availability of cookies during an academic course session affects evaluation of teaching. Med. Educ. 52, 1064–1072. doi: 10.1111/medu.13627

Hirschkorn, M. (2010). How vulnerable am I? An experiential discussion of tenure rhetoric for new faculty. Rev. Pensée Éduc. 44, 41–54.

John Molson School of Business (2023). “Assistant Professor, Management Accounting - Concordia University. Available online at: https://www.concordia.ca/content/concordia/en/jmsb/about/jobs/tenure-track/2023/assistant-professor-management-accounting.html (accessed January 25, 2024).

Kenny, N., Berenson, C., Jeffs, C., Nowell, L., and Grant, K. (2018). Teaching Philosophies and Teaching Dossiers Guide. Calgary, AB: Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning.

Klassen, R. M., Rushby, J. V., Maxwell, L., Durksen, T. L., Sheridan, L., and Bardach, L. (2021). The development and testing of an online scenario-based learning activity to prepare preservice teachers for teaching placements. Teach. Teach. Educ. 104:103385. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103385

Koon, J., and Murray, H. G. (1995). Using multiple outcomes to validate student ratings of overall teacher effectiveness. J. Higher Educ. 66, 61–81. doi: 10.2307/2943951

Linse, A. R. (2017). Interpreting and using student ratings data: Guidance for faculty serving as administrators and on evaluation committees. Stud. Educ. Eval. 54, 94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.12.004

Martin, J. (2018). “Research Methods in Education 8th Edition,” in Research Methods in Education, eds L. Cohen, L. Manion, and K. Morrison (London: Routledge).

Mazandarani, O., and Troudi, S. (2022). Measures and features of teacher effectiveness evaluation: perspectives from Iranian EFL Lecturers. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 21, 19–42. doi: 10.1007/s10671-021-09290-0

McFadyen, K. K. (1997). Multi-Faceted Performance Evaluation: The Role of Teaching Dossiers. Parkes: National Library of Australia.

Ni, A. (2013). Comparing the effectiveness of classroom and online learning: Teaching research methods. J. Public Affairs Educ. 19, 199–215. doi: 10.1080/15236803.2013.12001730

Oler, D. K., Skousen, C. J., Smith, K. R., and Talakai, J. (2022). An international comparison of the academic accounting professoriate†. Account. Perspect. 21, 131–146. doi: 10.1111/1911-3838.12271

Pan, G., Shankararaman, V., Koh, K., and Gan, S. (2021). Students’ evaluation of teaching in the project-based learning programme: An instrument and a development process. Int. J. Manage. Educ. 19, 100501. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100501

Presley, J., and Taylor, S. (2024). Guide to Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Presented by Presley BJJ. Available online at: https://www.samanthataylor.co/guide-to-bjj

Robert, J., and Carlsen, W. S. (2017). Teaching and research at a large university: Case studies of science professors. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 54, 937–960. doi: 10.1002/tea.21392

Rupp, D., and Susann Becker, E. (2021). Situational fluctuations in student teachers’ self-efficacy and its relation to perceived teaching experiences and cooperating teachers’ discourse elements during the teaching practicum. Teach. Teach. Educ. 99:103252. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103252

Sadeghi, K., Ghaderi, F., and Abdollahpour, Z. (2021). Self-reported teaching effectiveness and job satisfaction among teachers: the role of subject matter and other demographic variables. Heliyon 7, e07193. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07193

Seldin, P., Miller, J. E., and Seldin, C. A. (2010). The Teaching Portfolio: A Practical Guide to Improved Performance and Promotion/Tenure Decisions. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Taylor, S., Barnard, K., McGregor, J., and Rafuse, A. (2023a). Deloitte Canada’s cocreated ICT simulation for advanced accounting. J. Emerg. Technol. Account. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.2308/JETA-2022-020

Taylor, S., Charlebois, S., Crowell, T., and Cross, B. (2024). The paradox of corporate sustainability: analyzing the moral landscape of Canadian grocers. Front. Nutr. 10:1284377. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1284377

Taylor, S., Laguduva, S., and Bury, K. (2023b). 2023 CPAWSB’s Candidate Journey eBook. Edmonton, AB: Chartered Professional Accountants Western School of Business. Available online at: https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/83436/2023-CPAWSB-Candidate-Journey-eBook.pdf?sequence=1

Taylor, S., and McGregor, J. (2023). Goode food trucks Inc. Account. Perspect. 22, 209–214. doi: 10.1111/1911-3838.12337

Taylor, S., Riddle, P., Crowell, T., Bullock, A., and Chisholm, K. (2023c). Ted’s teas: A two-part accounting and audit “crossover case”. Account. Persp. 22, 195–207. doi: 10.1111/1911-3838.12334

Taylor, S., Sundararajan, B., and Munroe-Lynds, C. (2022). “Live Long and Educate: Adult Learners and Situated Cognition in Game-Based Learning,” in Handbook of Research on Acquiring 21st Century Literacy Skills Through Game-Based Learning, eds S. Taylor, B. Sundararajan, and C. Munroe-Lynds (Pennsylvania: IGI Global). doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-7271-9.ch011

Taylor, S., and Thion, S. (2023). How Has Teaching Effectiveness Been Conceptualized? Questioning the Consistency between Definition and Measure. Front. Educ. 8:1253622. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1253622

Tuma, F. (2021). The use of educational technology for interactive teaching in lectures. Ann. Med. Surg. 62, 231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.01.051

U15 Group of Canadian Research Universities (2022). Home - U15 Group of Canadian Research Universities. Available online at: https://u15.ca/ (accessed July 27, 2022).

Wiebe, S., and Fels, L. (2010). Thinking around tenure: ducking under the finish line. J. Educ. Thought 44, 11–26.

Wood, D. A., Achhpilia, M., Adams, M. T., and Zoet, E. (2023). The ChatGPT Artificial Intelligence Chatbot: How Well Does It Answer Accounting Assessment Questions?. Washington, DC: Issues in Accounting Education. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.2308/ISSUES-2023-013

Keywords: teaching dossier, teaching effectiveness, professional, professional training, professional faculty, accounting faculty

Citation: Taylor S and Charlebois S (2024) Teaching dossier guidance for professional faculty: an evidence-based approach for demonstrating teaching effectiveness. Front. Educ. 9:1284726. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1284726

Received: 29 August 2023; Accepted: 14 February 2024;

Published: 05 March 2024.

Edited by:

Stefinee Pinnegar, Brigham Young University, United StatesReviewed by:

José Cravino, University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro, PortugalShawn Simonson, Boise State University, United States

Fabiola Aparicio-Ting, University of Calgary, Canada

Cheryl Jeffs, University of Calgary, Canada

Copyright © 2024 Taylor and Charlebois. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Samantha Taylor, c2FtYW50aGEudGF5bG9yQGRhbC5jYQ==

Samantha Taylor

Samantha Taylor Sylvain Charlebois

Sylvain Charlebois