94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CURRICULUM, INSTRUCTION, AND PEDAGOGY article

Front. Educ., 26 March 2024

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1271924

This article is part of the Research TopicResearch and Discussions in Critical Discourses and Remedies in Global Health EducationView all 20 articles

Leah Ratner1,2

Leah Ratner1,2 Shela Sridhar1,2

Shela Sridhar1,2 Sheila Owusu3

Sheila Owusu3 Samantha L. Rosman1,4

Samantha L. Rosman1,4 Rose L. Molina5,6

Rose L. Molina5,6 Jennifer Kasper7,8*

Jennifer Kasper7,8*To date, the history of colonialism has permeated nearly every aspect of our conceptions, structures, and practices of global health; yet, there are no published medical school curricula aimed at promoting decoloniality in global health. We developed a pilot course for medical students to examine the history of colonialism, power, and positionality; promote self-reflection; and teach strategies for dismantling coloniality in global health. This five-part course was offered to students completing a scholarly project in global health with a mixed in-person/virtual format and online pre-session preparation materials. A pre-course survey on prior experiences in global health and self-efficacy was administered, and a reflection piece was analyzed for themes. After completion of the course, the students again completed the self-efficacy questionnaire, a course feedback survey and a semi-structured interview that was analyzed for themes. On average, the students felt that the course was relevant to their global health scholarly project and that the course met their learning objectives. There was a trend toward increased self-efficacy in decoloniality knowledge and skills following the course. In the post-course structured interviews, students raised issues reflected in the course materials including local project leadership; how identity, privilege and positionality influence relationships and the ability to attain mutual trust; project sustainability; and power dynamics. Undergraduate medical education in global health equity and decoloniality can play an important role in teaching future generations to dismantle the colonialism ingrained in global health and reimagine a global health practice based on equitable partnerships, community needs, and local leadership.

Global health is a field born out of colonialism, i.e., “influence and domination to maintain control over a people or area” (Kohn and Reddy, 2017; Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2023). By the early 1900’s, the British Empire alone colonized 84% of the world’s countries (Fisher, 2015). Health care and research was built for the colonizers’ benefit; colonized people were provided health care only so as to maximize economic output from their labor, which benefited the colonizers. The legacy of colonialism and related epistemic injustice (e.g., discounting local knowledge and practice and elevating the knowledge of those in power) and racism informed positionality. Positionality denotes dynamic relative status in society (University of British Columbia, CTLT Initiatives, 2024). Positionality can both be given and taken and can operate in multiple ways: people with power bestow power and privilege to others based on socially ranked attributes (e.g., gender, education, income); and a person with relative proximity to power based on how well their identities align with the dominant power structure may not be aware of their positionality. Such complex power dynamics have produced a lack of awareness on how to foster authentic partnerships across institutions and entrenched inequities in research, health care, and patient outcomes (Garba et al., 2021). This history permeates modern-day structure and practice of global health. Yet US medical students may not be aware of this history and how their relative power, privilege, and positionality in the world impact their interactions overseas. Global health engagement from students in Western contexts may perpetuate coloniality by primarily prioritizing the student experience rather than local partners’ needs and impacts (Binagwaho et al., 2021). While many medical schools have pre- and post-departure trainings, to our knowledge there are no published curricula in medical schools that promote decoloniality from pedagogy to reflection and action for medical students (Sridhar et al., 2023). To respond to this critical void, and take responsibility for this ongoing injustice, we developed an introductory medical student non-credit course to interrogate the history of colonialism in global health through pedagogical exchange and individual self-reflection as part of students’ creation and implementation of scholarly projects. Although born from different historical oppressions, recognizing power, privilege, positionality and systems of oppression that arise from interpersonal and structural root causes, anti-coloniality in global health has intersections with anti-racism education in the US (Daffé et al., 2021; AAMC, 2022). Similarly, education on decoloniality in global health requires students to carry an active and reflective role in dismantling and rebuilding with critical conscience, epistemic justice, and pragmatic solidarity. Epistemic justice refers to giving equal weight to many systems of knowing and generating knowledge, especially from those whose knowledge was and is discounted or seen as having less value. Pragmatic solidarity activating and delivering vital goods and services to those who lack them while also addressing structural issues that result in acute on chronic maldistribution (Farmer, 2008). While there is no single definition of decoloniality (Opara, 2021), for our study we defined it as a verb that encompasses praxis - the embodiment of action directed toward formation (Freire, 1970) - to both deconstruct and reconstruct global health engagement to include human rights, ethics, equity, collaboration, respect, and authentic partnership. Local/indigenous wisdom, authority, practice and decision-making capacity are key components (Trembath, 2023). The motivation and intention required to achieve this critical examination is foundational to global health work. Prior to launching a course on the history of and contemporary issues of colonialism and decoloniality in global health, it is imperative to understand students’ prior global health experience (breadth and depth), their grasp of power and positionality, and learning goals. This is key to delivering the right content at the right time for optimal engagement and learning. During medical school, students acquire substantive knowledge and skills, develop their identities as physicians, and are offered global health opportunities. As students embark on their careers it is critical that they are introduced to the history of colonialism and its persistent impacts today and acquire techniques to promote decoloniality. The aspirational objective of our pilot course is to help students transform their global health thinking and behaviors and prevent a perpetuation of colonial practice. This study aimed to evaluate the students’ understandings of oppression and decolonization at a theoretical level and their ability to reflect on the real world implications of these concepts in their work.

As an author group, we also want to make a collective statement about our own positionality. We are writing this work from elite academic institutions in the US and Africa. We recognize that this gives us proximity to power and therefore yields responsibility for change. We have written this work, and derived this course, as a first step to hold ourselves, our communities and our institutions accountable to continue to right this injustice.

The pedagogical framework underlying the foundation of this course involved acquisition of theory, reflective practice, and praxis in the field. Three key pedagogical principles were utilized: self-reflection, self-actualization and accountability. In this setting, we define self-actualization through Maslow’s framework as “a person being able to fully embody their talents, while also being able to fully verbalize their limitations” (Macleod, 2024).

1. Self-Reflection: The course was anchored to the students’ global health scholarly project (GHSP). The students learned by applying course content and frameworks to it. The timing of the sessions was designed to coincide with GHSP deliverables. The reflection questions in the prep work and in-class discussions required meaningful time to contemplate complex concepts of identity and proximity to power.

2. Self-actualization: The course was developed and delivered collaboratively with teaching faculty who lived and trained in historically, and in some cases, ongoing colonized settings in Low or Middle Income Countries (LMIC) to avoid it being solely presented by faculty educated within colonial paradigms. Faculty spoke about their lived experience and expertise during their teaching. Students were encouraged to discuss what skills they meaningfully used, what limitations they experienced in their skills and collaborations, and how their positionality and proximity to power influenced these.

3. Accountability. The creators of this course, and authors of this paper, feel strongly that we are held accountable for this work, to avoid common pitfalls that allow for performative outcomes. The meta-objective of the course was to create a learning lab of global health participants where students could update one another about their GHSP, share challenges and create space to share emotional experiences and ethical quandaries, strategize solutions, and support each other. The aim of the course creators was to create a safe, brave, and ‘ethical space,’ just beyond students’ zone of comfort and competency, with a goal of optimizing their learning (Vygotsky, 1978; Csikszentmihalyi, 2008). This intentional community also served as an accountability structure to continue to support each other as individuals, collectively as a group, and eventually as an institution, to decolonize (Zinga et al., 2009; Zinga and Styres, 2018; Battiste, 2019).

We developed and delivered a five-part pilot course over a 12-month period at Harvard Medical School (HMS) focused on supporting decolonialized learning and action. This was an optional course targeting HMS students engaged in a global health scholarly project (GHSP). Completion of a scholarly project is a graduation requirement, the objectives of which include the following: engage in original scholarly work addressing a question in medicine/public health, using approaches from a range of scientific or social science fields; work closely with a faculty mentor on a scholarly project in a partnership that is mutually beneficial; and inspire curiosity, develop critical thinking skills, and identify analytical tools useful for the future physician-scholar. The GHSP process involves the following steps and deliverables: 1) submit a global health concept and mentor information; 2) submit a five-page proposal that is reviewed by a global health advisory committee member and/or the chair (JK); 3) spend 3–5 months (12 months if taking a 5th year) in a LMIC or indigenous setting in the US; 4) write an article for publication or submit a final report, which is critiqued by the reviewer who critiqued their proposal.

A core group of faculty working in global health were course co-creators and educators. Faculty choice was intentional to include scholars from LMIC settings as well as Harvard-based scholars to help support institutional change. The course was designed over a 6-month period of consensus-building discussions regarding key concepts that were necessary for undergraduate medical students. The course was adapted from a similar curriculum designed for pediatric global health fellows (Sridhar et al., 2023), co-authored by several members of this group. Discussions by course creators focused on the overlapping and disparate role of the medical student as compared to a fellow committed to a global health career. We identified the pieces of the fellows’ curriculum that represent foundational knowledge relevant to the student’s immediate GHSP and for future growth and development as students consider and potentially embark on a global health career. The group determined that core concepts in decoloniality in global health should coincide with key scholarly project deliverables to ensure that the course extended beyond traditional theory-based curricula. These core concepts included: defining colonialism in global health and as it pertains to student GHSP; ethics of short-term experiences in global health (STEGH); ethics of global health research; and coloniality in the US. All course materials were provided on an internal learning platform (Figure 1 and Table 1). Overall pedagogical framework was informed by critical consciousness raising, which in health profession education is a powerful framework for anti-oppression teaching (Halman et al., 2017).

Figure 1. Relationship between pilot course topics and students’ global health scholarly project deliverables.

Course sessions were held while students were in-country at different periods of time and in different time zones. To meet learners’ needs, all prep material was available online; students could participate in the sessions in person or via Zoom; and the sessions were recorded for asynchronous learning.

Prior to course launch, students were asked to complete an anonymous survey to assess their baseline ability to apply concepts of power and positionality to their global health work to date; self-efficacy statements (“I feel confident”) used 5-point Likert scales that rated responses from strongly agree to strongly disagree. We asked students to describe their previous global health experiences, meaningful moments and concerns that they observed or experienced, definition of colonialism and learning goals for the upcoming year, time available to complete prep work for each seminar; and likelihood of asynchronously completing prep work for missed seminars (4-point Likert scale from extremely unlikely to extremely likely). Students also wrote an essay on how they developed their GHSP and what it means to examine and revise it from a decoloniality perspective. There was significant discussion by this author group on the order and style of questions so that participants would feel safe being open and honest, but also trying to ensure participants did not feel like there was one “right answer” or that they needed to repeat existing literature and academic frameworks.

At course completion, students were asked to complete another anonymous survey that included a course evaluation, the self-efficacy statements, and an assessment of knowledge acquisition and applicability to their GHSP. They also participated in a 30 min one-on-one semi-structured interview. A team member who was not directly involved with teaching or evaluating the course performed and recorded the interviews via Zoom; all students were given the option to use their camera. The interview guide was designed by the research team and included questions about a meaningful and a concerning moment during their GHSP; lessons learned from the seminar series; future careers plans; and how their school can initiate structural change to promote decoloniality and equity in global health. Questions were designed to promote self-reflection and gain deeper insight into the student’s recognition of their own dynamic positionality and role(s) in these settings and reflection on their responsibility as students from an elite US academic medical school.

Essays, surveys and interview questions were designed to answer the question “are students using principles of self-reflection, self-actualization and accountability to actively and pragmatically decolonize their [global health] experiences?” The goal of this work, as set forth by this author group, was (and continues to be) to foster growth individually, collectively and institutionally. Therefore, the goals of our pragmatic inquiry were to encourage students to dissect the nuance (and the reality) of this work; continually enhance the course to support change in how students individually consider and implement their work in global health; and ultimately influence collective change. During the seminars, this author group observed the students searching for the “correct answer,” a tendency we have witnessed in other academic settings. This type of thinking and institutional culture leads to more concrete thinking, without consideration of context or complexity. For example, many students expressed concerns about themselves or others pursuing global health opportunities in regions of the world that they personally had no connection to. This is evidence of self-reflection; however, it also allows students to avoid the discomfort of further exploring the practical impacts of their disengagement in the process as future practitioners from a high income country and often as those from “colonizing” institutions.

Pre- and post- course survey results were compared. The quantitative analysis was done using basic descriptive statistics in excel, and open-ended answers were analyzed with content analysis and components of relational analysis. Themes were denoted at the level of sentences and phrases rather than word or word-pairing. As concepts emerged, concept frequency was coded.

Pre-course essays were redacted by a team member who was not involved in the analysis. The interviews were transcribed and redacted with the same process. Two independent reviewers analyzed the redacted essays and interview transcriptions using open codes with a grounded theory and thematic approach. A combination of inductive and deductive coding was employed. Both reviewers reached saturation after reviewing approximately 70% of the essays and interviews. A code book was generated and reviewed by a third reviewer to break any ties. Each essay and interview was re-reviewed by both reviewers using the agreed upon code book. After all of the data had been coded, codes were categorized into themes, which were then categorized into concepts and assertions.

General themes were considered with quantitative findings to describe the students’ progression through the curriculum. Our study was reviewed by the HMS Program in Medical Education’s Educational Scholarship Review Committee and was exempted from IRB review.

All students who planned to engage in a GHSP were invited to participate in the course (N = 14). Ten enrolled and seven attended at least one session. Four were ineligible because they did not complete a GHSP. We focused our analysis on five students who completed our pilot course and their global health scholarly project. All of them completed the pre-course survey, post-course survey, and post-course interview; four completed the pre-course essay.

Prior to medical school, these five students had 13 distinct experiences in a mix of rural and urban low and middle income and indigenous settings in 12 countries. Their reported global experiences included working in community, health care, research, and public health. Their time overseas varied: six of their experiences were less than 2 months; three were two-twelve months; and four were greater than 12 months. Activities they were engaged in included water contamination, people with disabilities, maternal and child health, mental health, COVID19, nutrition, and indigenous peoples.

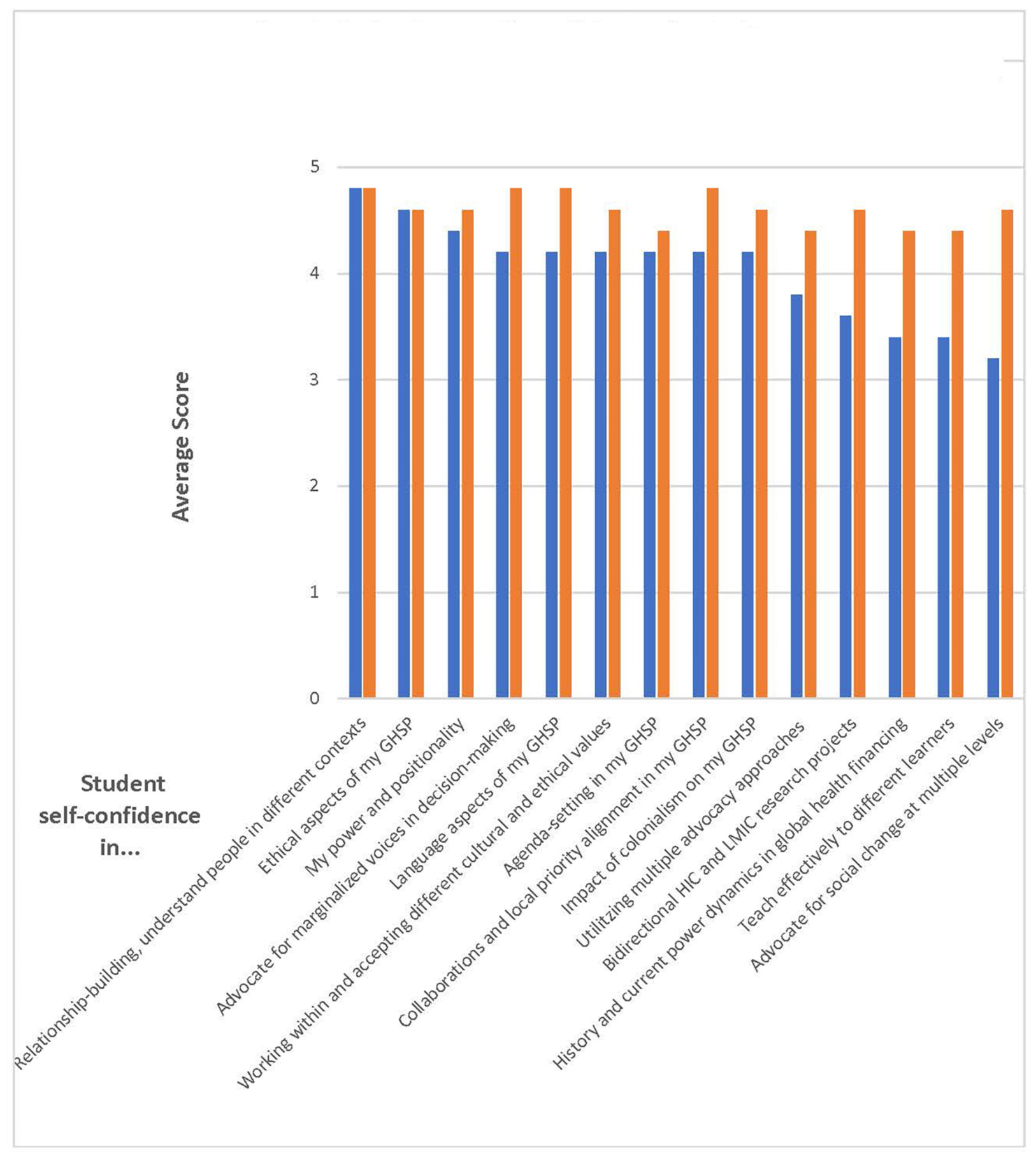

Prior to the course, responses to the self-efficacy survey highlighted that students felt most confident in their ability to build relationships with global partners that facilitated understanding of needs, values, and preferences of people in different contexts. They also expressed confidence in their knowledge of colonialism and its impact on their GHSP; planning their GHSP in collaboration with local partners and aligned with local priorities, with an awareness of who is setting the agenda and which perspectives are missing; evaluating the ethical strengths and weaknesses, and the influence of language and communication on their GHSP; their relative power and positionality, ability to advocate for the inclusion of marginalized voices in decision-making, and working with and accepting ethical and cultural differences. They were less confident in their ability to ensure research projects were bidirectional and promoted local leadership and priority-setting; describe the historical forces that influence current power dynamics in global health financing; and how to utilize multiple advocacy approaches to advocate for social change (Graph 1).

Graph 1. Student self-confidence in their ability to apply concepts of power and positionality to their global health work to date (N = 5). Scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 3 = neutral/no opinion, 4 = somewhat agree, 5 = strongly agree.

The self-efficacy surveys conducted after course completion indicated that there was a general trend toward increased self-confidence across all domains. The greatest increase in self-confidence occurred in students’ ability to promote bidirectional research; effectively teach; understand the historical and present influences on global health financing; and advocate for social change (Graph 1).

Duration of time in-country did not correlate with confidence levels in any domains. Among goals for the course, students named seeking mentors for global health career development, centering local priorities and control of research with bidirectional partnerships, learning about the influence of colonialism on global health, and supporting indigenous activities to promote decolonization.

Students’ pre-course essays (N = 4) highlighted three key themes: current existing colonial practices, working toward anti-colonial practice, and aspirational goals (Table 2).

When discussing prior meaningful moments during their pre-medical global health engagement, the students mostly focused on something they gained from their work (e.g., knowledge, new perspectives, writing skills), and two also spoke about collaborating with a local NGO, and working in the background to amplify the voices of the local colleagues. One student discussed the contemporary, lingering effects of colonization. When asked about moments that raised concerns, the students named asymmetry in resources (e.g., financial, skill building). One student identified the exclusion of local people from conversations and agenda setting. In their definition of colonialism, the students wrote about influence or control of one group over another. Three students spoke about the extractive nature of colonialism, and two students discussed contemporary ramifications of historical practices.

Nearly every student reported completing at least some of the pre-session prep material, but no one reported completing all of it for all five sessions; there was a trend in less preparation for the final two sessions. There was a mix of in-person and virtual participation; similar to preparation, there was less attendance at the last two sessions. On average, the students found the course content very relevant to their GHSP. Students did not report that voices were marginalized or that the course lacked diversity and inclusivity or conveyed bias. Three students agreed or strongly agreed that the course met their learning goals, which included understanding decoloniality work as a process, building community, engaging in critical discourse, and gaining perspective on how to view their role as an outsider. Based on theory discussed during coursework, students reported witnessing deference to local leaders to determine project utility, aims and priorities; how their privilege and identity are at play when connecting with local communities and attempting to build mutual trust; balancing personal obligations and sustainability; and how power dynamics played out in funding (e.g., less opportunities for non-US-based people to travel), partnerships (e.g., government presence), authorship, and project-specific decisions (e.g., non-US people had less voice). Students recommended that future course iterations continue to involve global faculty speakers, STEGH cases and frameworks, and ongoing discussions of individual student’s GHSP.

Similar to the post-survey findings, key themes that emerged in the post-course interview included relational reflections, role reflection, the translation of decolonial theory into personal practice, questioning the bigger picture (and meaning) in this work and a sense of individuality. Emergent themes were categorized and meaningful quotes were re-reviewed to ensure they were representative of the themes (Table 3). These themes were slightly different from the pre-course findings focused on aspirational goals, indicating that the course did push students to consider the more practical implications of their work.

Our findings indicate that the first step in promoting decolonized ideals in global health education for medical students

is to create a learning environment that supports genuine reflective transformational learning. We look to indigenous scholar and thinker, Willie Ermine, on the creation of an ethical space: “An ethical space is not something that is tangible, rather, it is an acknowledgment of a metaphorical ‘space’ that exists between beings through which differing worldviews can interact in authentically (Ermine, 2007).” From our experience, this requires shedding light on the historical power imbalances and oppression that have shaped present-day global health; the students’ relative power and positionality in that world; and how student deliverables do not necessarily follow the same timeline as the Global South or promote the incorporation of community needs and local leadership. To do this requires accountability, authenticity, and vulnerability on the part of the teachers to model and support ethical space creation.

It is worth noting that the quantitative statements around confidence both started and ended at a rather high level, converging with emergent themes around individuality. This illustrates the notion (and the harm that can come from) one’s personal reflection without accountability. Although students may feel confident, they may have unrecognized and unchecked biases based on their own lived experiences (Wong et al., 2021). Therefore, there must be accountability in their GHSPs to ensure that they are not only learning theory, but also truly engaging in reflective practices and praxis. During their exit interviews, genuine and intentional collectivism and building of collaborations were lacking in most of their comments about their GHSP. Research topics were chosen, in some cases, before engagement with the community and did not always involve the community members or prioritize the needs of the community (Noor, 2022). Our course must ensure that students do not pay lip service to decoloniality or resort to tokenism, but rather that they are truly moving toward a collective unity in practice (wa Thiong’o, 1994). Our course needs to push students to identify their own biases and where they can make improvements. To accomplish this, we must create ethical spaces informed by collective vulnerability, humility, curiosity, and ultimately accountability (Wilson, 2022).

We learned key lessons regarding course feasibility. Although our bias is that in-person participation ignites the greatest engagement, sharing, and learning, having a virtual option and making the materials available for asynchronous learning optimizes opportunities for learning. Student participation and guest lectures via Zoom enriched, rather than detracted, from the conversation. However, despite accessibility to the course and its materials, participation waned over time. This could be a product of the optional nature of the course and the asynchronous component; varying times zones; suboptimal internet bandwidth in-country; and a lack of cohesion and accountability among the student cohort. Students who were overseas for the last two sessions of the course said they could not participate because of the difference in time zones. Furthermore, it may be that competing priorities increased toward the end of the academic year. This coming year the course will be a required component of the GHSP, so we will develop tools for greater accountability. We will plan regular check-ins with students and require written reflections for asynchronous learning as a way to evaluate engagement with the topics and provide course credit. Another goal is to create an ongoing global health learning lab whereby we foster more interactions, communication, and cohesion among the students both inside and outside the course. We were fortunate to have teaching faculty who lived and trained in historically and ongoing colonized settings to educate the students. Students said we should invite them to speak at future course iterations. We recognize that this can be an extra burden on these teaching faculty. We must continue active discussions about whether and how they would like to continue teaching the course and to compensate them for their time and expertise.

There are a number of limitations to our study. Our small sample size does not allow us to draw meaningful conclusions about the potential broader impact of this course. But our findings suggest that students felt this was a valuable experience that met their learning objectives and enhanced their understanding, knowledge and efficacy in global health equity. Our study may have had selection bias: the students in this pilot course chose to participate knowing the topic and therefore may represent a group that is more knowledgeable about, more confident in, and committed to promoting decoloniality and equity in global health. As we look to expand the audience, first to all students conducting a GHSP, and eventually to all medical students engaged in any global health activity, it will be important to assess whether it has a similar impact and effectiveness. Finally, we do not know how knowledge and ability to discuss key concepts in global health decoloniality correlate with and translate into true decolonial praxis in global health (Ratner et al., 2022). It will be important to develop metrics to not only assess student knowledge, insight, and understanding but also how the course impacts decoloniality behaviors and practices by students in the field.

As we embark on teaching decoloniality and global health equity to medical students, it is critical that we examine how we simultaneously educate faculty and hold them accountable to equitable global health engagement. In addition, the structures in place, especially within our own institutions, may serve as barriers to true praxis in decoloniality (Eichbaum et al., 2021). Time constraints and educational requirements impact both scholarly projects and away rotations in ways that may work against local control and equitable partnerships based on community needs. Student evaluations by faculty, residency application criteria, grant funding criteria, and academic promotion policies often favor academic skills and work products over true bidirectional partnerships promoting local leadership and community involvement in global health. As we educate students on these issues we must also advocate for dismantling systems that promote coloniality and instead incentivize decolonial global health practices (Besson, 2021). Without this, the “hidden curriculum” promoting US control of global health efforts will work against the teachings of this course.

Our generation has inherited a global health practice born out of colonialism. It is our responsibility to dismantle this colonial legacy and the inherent conceptions and biases in both ourselves and our learners so that we do not continue to pass it on to future generations. We hope that this course serves as a first step in teaching our future physicians the foundations of dismantling colonialism and replacing it with a new global health praxis based on respectful partnerships, local leadership and community needs (Farmer et al., 2013). With continued refinement based on learnings and feedback and an assessment of the curriculum’s efficacy, we hope that this can serve as a model for introducing medical students to decoloniality so that they authentically walk the walk as they talk the talk.

We want to acknowledge that as an author group we are all committed to our personal ongoing journeys in decolonizing, and we have a long way to go. This work was conceptualized through our own epistemic understanding of this injustice, and fails to bring in other ways of knowing. We recognize that the completion of a course, or an essay, may support one’s journey to understanding this work, but does not indicate it is done. We invite feedback, critiques and further guidance from others on how to continue to hold ourselves and our institutions accountable. Lastly we also acknowledge that writing about decolonizing global health is not enough. We must continue to embody its principles every day, in every action. This paper is just the beginning.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

JK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. LR: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review and editing. SS: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review and editing. SR: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review and editing. RM: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. SO: Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review and editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We wish to acknowledge Ms. Kari Hannibal, who was responsible for all course logistics. We also wish to acknowledge Dr. Jonas Attilus, Dr. Sheila Owusu, Mr. Desmond Jumbam, Dr. Bethany Gauthier, and Prof. Joe Gone, extraordinary people and teachers who made time to educate the HMS students.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AAMC (2022). Diversity, equity and inclusion competencies across the learning continuum. AAMC new and emerging areas in medicine series. Washington, DC: AAMC.

Besson, E. K. (2021). Confronting whiteness and decolonising global health institutions. Lancet 397, 2328–2329.

Binagwaho, A., Allotey, P., Sangano, E., Ekström, A. M., and Martin, K. (2021). A call to action to reform academic global health partnerships. BMJ 375:n2658. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2658

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Daffé, Z. N., Guillaume, Y., and Ivers, L. C. (2021). Anti-racism and anti-colonialism praxis in global health—reflection and action for practitioners in US academic medical centers. Amer. J. Trop. Med. Hygiene 105, 557–560. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.21-0187

Eichbaum, Q. G., Adam, L. V., Evert, J., Ho, M. J., Semali, I. A., and van Schalkwyk, S. C. (2021). Decolonizing global health education: Rethinking institutional partnerships and approaches. Acad. Med. 96, 329–335.

Farmer, P. (2008). Challenging orthodoxies: The road ahead for health and human rights. Health Human Rights 10, 5–19.

Farmer, P., Kleinman, A., Kim, J., and Basilico, M. (2013). Reimagining global health: An introduction [Internet]. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 508.

Fisher, M. (2015). Map: European colonialism conquered every country in the world but these five. Vox, Feb 24, 2015. Available online at: https://www.vox.com/2014/6/24/5835320/map-in-the-whole-world-only-these-five-countries-escaped-european (accessed February 9, 2024)

Garba, D. L., Stankey, M. C., Jayaram, A., and Hedt-Gauthier, B. L. (2021). How do we decolonize global health in medical education? Ann. Glob. Hlth. 29, 1–4. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3220

Halman, M., Baker, L., and Ng, S. (2017). Using critical consciousness to inform health professions education. Perspect. Med. Educ. 6, 12–20. doi: 10.1007/s40037-016-0324-y

Kohn, M., and Reddy, K. (2017). “Colonialism,” in The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, ed. E. N. Zalta. Available online at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/colonialism/ (accessed August 2, 2023).

Macleod, S. (2024). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Simply psychology, Jan 24, 2024. Available online at: https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html (accessed February 9, 2024).

Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2023). Colonialism. Merriam-Webster.com. Available online at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/colonialism (accessed August 2, 2023).

Noor, A. M. (2022). Country ownership in global health. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2:e0000113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000113

Opara, I. M. (2021). It’s time to decolonize the decolonization movement. Speaking of medicine and health. Available online at: https://speakingofmedicine.plos.org/2021/07/29/its-time-to-decolonize-the-decolonization-movement/ (accessed August 2, 2023).

Ratner, L., Sridhar, S., Rosman, S. L., Junior, J., Gyan-Kesse, L., Edwards, J., et al. (2022). Learner milestones to guide decolonial global health education. Ann. Glob. Hlth. 99, 1–8. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3866

Sridhar, S., Alizadeh, F., Ratner, L., Russ, C. M., Sun, S. W., Sundberg, M. A., et al. (2023). Learning to walk the walk: Incorporating praxis for decolonization in global health education. Glob. Pub. Hlth. 18:2193834. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2023.2193834

Trembath, S. (2023). “Decoloniality.” American university subject guide. Available online at: https://subjectguides.library.american.edu/c.php?g=1025915&p=7715527 (accessed August 2, 2023).

University of British Columbia, CTLT Initiatives (2024). Positionality & intersectionality. Available online at: https://indigenousinitiatives.ctlt.ubc.ca/classroom-climate/positionality-and-intersectionality/ (accessed January 31, 2024).

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. From: Mind and society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 79–91.

wa Thiong’o, N. (1994). Decolonizing the mind: The politics of language in African literature. Nairobi: East African Publishers.

Wilson, C. (2022). Engaging decolonization: Lessons toward a theory of change for transforming practice. Teach. High. Educ. 2, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2022.2053672

Wong, S. H. M., Gishen, F., and Lokugamage, A. U. (2021). Decolonising the medical curriculum‘: Humanising medicine through epistemic pluralism, cultural safety and critical consciousness. London Rev. Educ. 19, 1–22. doi: 10.14324/LRE.19.1.16

Zinga, D., and Styres, S. (2018). Decolonizing curriculum: Student resistances to anti-oppressive pedagogy. Power Educ. 11, 30–50. doi: 10.1177/1757743818810565

Keywords: global health, decoloniality, colonialism, medical student, undergraduate medical education, scholarly project, equity, coloniality

Citation: Ratner L, Sridhar S, Owusu S, Rosman SL, Molina RL and Kasper J (2024) Talk the talk and walk the walk: a novel training for medical students to promote decoloniality in global health. Front. Educ. 9:1271924. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1271924

Received: 03 August 2023; Accepted: 04 March 2024;

Published: 26 March 2024.

Edited by:

Benedicta Ayiedu Mensah, University of Ghana, GhanaReviewed by:

Anna Kalbarczyk, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Ratner, Sridhar, Owusu, Rosman, Molina and Kasper. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer Kasper, amthc3BlcjFAYndoLmhhcnZhcmQuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.