- Department of Audiology, School of Human and Community Development, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Background: The emergence of the Speech-Language and Hearing (SLH) professions in South Africa took place during the era of racial segregation. Consequently, the culture and language of these professions have predominantly reflected the minority White population, even in SLH training programs. English has remained the language of learning and teaching (LOLT) in most South African tertiary institutions, with a strong Western cultural influence. Given the increasing diversity in these institutions, a mismatch between the language of instruction and that of English Additional Language (EAL) students poses academic challenges for this population, prompting the need for this study.

Aim: This study aims to investigate the learning and social experiences of EAL undergraduate students enrolled in South African SLH training programs, with a specific focus on exploring their engagement with academic content in the curriculum.

Methods: A cross-sectional online survey design was employed, and a total of 24 EAL students participated in the study. Descriptive and thematic analysis methods were utilized for data analysis.

Results: The findings revealed that EAL students encountered academic challenges primarily related to their proficiency in the LOLT, which were most pronounced in lectures and examinations, while being relatively less pronounced in assignments. Complementary use of indigenous languages, simplification of complex terminology and self-employed strategies to cope in response to the existing academic language challenges are highlighted. These findings underscore the significance of addressing pedagogical approaches, language policies, and curriculum transformation towards a more Afrocentric perspective.

Conclusion: The study highlights the academic difficulties faced by EAL students in South African SLH training programs. The implications for future interventions in this context are highlighted. The findings emphasize the need for pedagogical reforms, language policy considerations, and curriculum transformation that embraces Afrocentric perspectives. Addressing these issues is crucial to ensure equitable educational experiences and support the success of EAL students in the SLH field.

1 Introduction

The use of the English language in education in South Africa finds its documented origins in the 1600s – the early colonial epoch of the country when Europeans settled into the country, establishing Dutch (later Afrikaans) and English as the sole languages of education across the country (Suveren, 2019; Mutepe et al., 2021). This backdrop indubitably automated an educational advantage for native speakers of the two languages (Chetty, 2012). Only later during colonial rule were African languages initiated into the education locale, although only up to higher primary and not to levels beyond. Even so, the quality of education varied between the former and latter (Mutepe et al., 2021). What did this signify for non-speakers of the two colonial languages? A deprivation of quality education and very limited interaction with the languages of learning, and inevitably the associated cultures (Mutepe et al., 2021), as well as exclusion and marginalization in certain professions such as SLH professions (Khoza-Shangase and Mophosho, 2021). Nonetheless, even amid a transformed South Africa post-Apartheid, the residues of history still linger around with students exiting non-English based schools and communities into higher education institutions centralized on English-use in all their undertakings (Mutepe et al., 2021). This births a myriad of challenges both socially and academically for these students.

Language, whether directly or indirectly, plays a paramount role in the way one experiences academia and all that encircles it, including the social aspect of the space and experience (Pappamihiel, 2002; Sanner et al., 2002; Bolderston et al., 2008). Equally so, language and culture in all spheres of life, are intricately and inextricably related, and jointly determine an individual’s sense of inclusion or exclusion, and consequently, participation in a particular space (Khoza-Shangase, 2019). In fact, it is virtually impossible to veritably understand and indulge in a particular culture void of language familiarity and comfortability. Language fosters engagement and negotiation of one’s sense of self within the cultural context in which they are found (Foster and Ohta, 2005).

This is no different in the academic space; where the language of learning, teaching, and overall interaction is indivisibly intertwined with institutional culture and participation, as a result (Martirosyan et al., 2015; Almurideef, 2016). Therefore, a disconnect between one and the institutional culture of their academic space through language, has layered implications for participation (social and academic), performance, and overall experience (Almurideef, 2016), among other factors. In view of this background, the need for the current study is highlighted in which the social and learning experiences of English Additional Language (EAL) students were explored and from which necessary changes and efforts can potentially be provoked for the enhancement of the experiences of this population within an African context where capacity versus demand challenges are significantly associated with linguistic and cultural incongruency between the SLH workforce and the population they serve.

English Additional Language (EAL) students represent a rapidly growing group in higher education academic institutions in South Africa (Martirosyan et al., 2015), especially considering the overwhelming diversity that characterizes the rainbow nation since the dawn of South Africa’s democracy (Chetty, 2012; Mutepe et al., 2021). At the break of democracy, all known South African languages were granted officiation, followed by the accompanying trails of ongoing transformation and diversification initiatives in the country’s institutions (Naicker, 2016). In addition to this, South Africa is witnessing an influx of a wide range of international residents and students (Mutepe et al., 2021). This populace of individuals adds significant value to the country on numerous levels including culturally, linguistically, educationally, and economically—with their rich contribution of blended perspectives that enhance and expand the scope of research, learning and teaching, social interaction, and tourism (Almurideef, 2016). This collection consequently renders the country more diverse and more internationally appealing (Almurideef, 2016).

This contextual reality indicates that more than ever before, the chances of finding a significant number of native speakers of the dominant language of academia (English) in South Africa are becoming increasingly low (Linake and Mokhele, 2019). As such, language-related rigidity and mindlessness in academic institutions ought to be carefully reflected upon, particularly in professions at the heart of which is language and communication, such as the communication sciences – speech-language pathology and audiology, called SLH in this paper (Seabi et al., 2014; Khoza-Shangase and Mophosho, 2018). Language is especially important in these professions given the nature of the services, duties, and practices that define the core and essence of what it means to practice the professions of audiology and speech-language pathology (SLP). These professions are mainly linguistically demanding and involve elaborate verbal and written communication with a wide range of individuals. This includes colleagues, clients who present with communication pathologies, allied professionals, and even the general public as reflected in the framed description of the duties of Audiology’s and SLP’s by professional bodies (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2018). Albeit the distinction of roles between SLP’s and Audiology’s, the area of commonality remains fundamentally the communication-centeredness of both professions (Pillay and Kathard, 2015). This highlights the importance of language proficiency for SLH students as communication is not only a life-long necessity for success in the professions, but a success determinant for the duration of their academic and clinical training and practice.

Due to the era when SLH professions were developed in South Africa, during apartheid, the SLH professions are historically rooted in Western, mainly English/Afrikaans ideologies, social, academic, and clinical practices (Pillay and Kathard, 2015). These ideologies are far removed from the reality of the South African population which is largely composed of African language speakers – the grand majority who remain the ‘minority’ in the demographic profile of the professions (Khoza-Shangase and Mophosho, 2018, 2021), starting from the SLH programs academic staff themselves. Consequently, within the South African context, there appears to be a disconnect and mismatch between the homogenous nature of the professions and intents to improve the provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate services (Khoza-Shangase and Mophosho, 2018; Pillay et al., 2020). This has become worse in recent years where the present reality indicates that the racial profiles of students within SLH academic programs are rapidly changing with a significant intake of Black, Indian, and Colored (mixed race) students at universities (Mutepe et al., 2021).

Over the years, several researchers in various contexts and disciplines, have investigated the interaction of EAL students within the academic environment, with findings revealing and highlighting the overall experiences and challenges faced by EAL students (Tshotsho, 2006; Bolderston et al., 2008; Cheng and Fox, 2008; Martirosyan et al., 2015; Civan and Coskun, 2016; Hall, 2019; Ndawo, 2019; Mutepe et al., 2021). The challenges documented include poor academic performance due to unviable English proficiency (Pappamihiel, 2002; Bolderston et al., 2008; Chen, 2015; Sidman-Taveau and Karathanos-Aguilar, 2015; Almurideef, 2016; Hall, 2019; Oducado et al., 2020; Mutepe et al., 2021), anxiety (Pappamihiel, 2002; Kagwesage, 2013; Chen, 2015), social exclusion (Pappamihiel, 2002; Sanner et al., 2002; Bolderston et al., 2008; Almurideef, 2016), and the lack of a sense of identification with and assimilation into the institutional culture of their institutions, among other factors (Bolderston et al., 2008; Cheng and Fox, 2008; Hall, 2019).

Although there is a significant body of literature exploring the experiences of EAL university students, this has mostly been reflective of Western contexts, particularly the United States of America and Canada (Sanner et al., 2002; Bolderston et al., 2008; Cheng and Fox, 2008; Martirosyan et al., 2015; Sidman-Taveau and Karathanos-Aguilar, 2015). Similar studies conducted in the South African context were conducted mainly in fields such as nursing and medicine (Ndawo, 2019). Existing South African studies focusing on the SLH professions, such as that of Seabi et al. (2014) who broadly investigated the living, learning, and teaching experiences of students in higher education in South Africa from three professions, are without a particular focus on EAL students in the SLH professions although students from SLH were included. Most recently, Abrahams et al. (2023) reports on transformation of higher learning in South Africa, with a focus on perceptions and understanding of speech-language pathology and audiology undergraduate students.

It is evident that several years well out of the apartheid dispensation, South African SLH professions remain overly representative of dominant minority populations in the presence of a diverse African population (Khoza-Shangase and Mophosho, 2018). Ideologies and practices of segregation that gave current minorities the upper hand, including language use, remain deeply ingrained in institutions. The English language continues to uphold the position of status and education (Mutepe et al., 2021). This is reflected in the SLH departments in institutions across the country where language and culture maintain a lack of connectedness to that of the majority (Khoza-Shangase and Mophosho, 2021), the majority that remains academically and socially disadvantaged due to language inadequacies. This disadvantage therefore leads to poor representation of EAL students in postgraduate programs, with the consequent outcome of restricting changes in the academics’ demographic profile. A consequence of this underrepresentation extends into a scarcity of linguistically and culturally diverse SLH services in public healthcare—a problem that is yet to be solved in the South African context (Khoza-Shangase and Mophosho, 2021).

In view of this introduction, it can be concluded that in as much as fitting the demographic profile an EAL SLH student may prove advantageous and helpful within the communities to be rendered SLP and Audiology services in a multi-linguistic and diverse South Africa, there still exists an overwhelming plethora of subtle challenges and complexities faced by EAL students. Existing evidence in this area of study has, however, mainly been documented in high income countries with cultural and linguistic contexts and dynamics far different from that of South Africa. The sole published study (Ndawo, 2019) within the South African context is still limited in that it only reviewed the experiences of EAL nursing students, whose scope of practice is not communication pathology as in SLH professions. This area, therefore, still requires some attention in the South African context. This study formed part of a larger study titled “Investigating the experiences and performance of English second language SLA Students,” with its focus being on undergraduate students in a South African University SLH training program.

2 Materials and methods

The primary aim of the research was to explore EAL undergraduate students’ engagement with the academic content in their curriculum in a South African SLH Training Program.

2.1 Research design

To obtain a rich, holistic, and comprehensive view and understanding of the experiences of the EAL SLH students, this study employed a cross-sectional mixed method online survey design (Babbie and Mouton, 2005; Wright, 2005).

2.2 Participants

A non-probability purposive sampling strategy was adopted to allow for the specific and deliberate recruiting of participants capable of providing relevant information for the study as guided by the aim (Cozby, 2009). That is, the sampled participant pool comprised EAL undergraduate students in the SLH program in the 2022 academic year. This program is located in Gauteng, South Africa.

The sample included second- and third year EAL SLH students, and a total of 24 participants agreed to be part of the study. Although this is slightly lower than the expected sample size and population (approximately 80 students in these years of study, of which just under half would meet the inclusion criterion of language), this number of participants was sufficient to obtain a meaningful understanding and picture of the learning and social experiences of EAL SLH students at the university. Considering the inclusion criteria and the high response rate, it can be argued that the current sample was representative of the SLH EAL population at the University.

2.3 Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included that participants had to be registered students at the University in either Speech-Language Pathology or Audiology; and that they had to be English Additional Language speakers; English had to be their additional rather than a native language.

2.4 Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included that students in the SLH program to whom English is not an additional language; that is, English as a First Language (EFL) speakers; EAL SLH 1st year students, as it was assumed that they may be too novice and have insufficient experience in the programs and limited knowledge of departmental culture to comment on learning and social experiences yet; EAL SLH 4th-year students (final year students), as researcher familiarity with participants as a peer may be a confounding factor, especially ethically (McDermid et al., 2014), considering the researcher formed part of this population for the duration of the study; and postgraduate EAL SLH students since the researcher sought to specifically unveil the experiences of students who engage in full-time lectures and clinical practicums as they were in the position of providing more stratified data and to directly provide responses to the research questions. Postgraduate training in South Africa is only for research and not academic or clinical training, with clinical and academic training all taking place at undergraduate level.

2.5 Data collection procedures

2.5.1 Measures or instruments – online survey

An online survey data collection tool in the form of a self-composed questionnaire (Appendix A), adapted from Abrahams (2021) instrument, was used to collect data. Considering the structure and content of the Abrahams instrument, guided by the focus of the current research objectives, the researcher referred to literature around EAL students’ academic and clinical challenges, challenges to participation, social challenges, and institutional culture perceptions across various contexts to develop the survey questionnaire used in this study.

The questionnaire was presented in English considering SLH students are most likely to have considerable proficiency in the language. However, to avoid any misconceptions, the English level used in the questionnaire was kept simple. The researcher ensured that only familiar terms were used and that phrases were presented in simple forms. In cases where simplification was not possible, brief explanations were provided.

Google Forms, an online survey template, was used to develop the survey used. Participants were able to access the survey via a link. The tool comprised a combination of close-ended and open-ended questions totaling to 41 questions. More specifically, the survey consisted of 30 close-ended questions and 11 open-ended questions (Hyman and Sierra, 2016). The survey was open for 6 weeks, with an extension of 2 weeks to improve the response rate.

The survey was divided into five separate sections as follows:

• Demographic Information.

• Academic Experiences.

• Clinical Experiences.

• Participation Factors.

• Social Inclusion and Institutional Culture.

The current paper focuses on the academic experiences.

The use of an online survey in this study was justified based on several considerations related to the research aims, practicality, and accessibility: (1) accessibility, flexibility, and reach—in the current study utilizing an online survey allowed the researchers to connect with a diverse group of very busy students efficiently. It eliminated the need for physical and time-bound presence, making it more feasible to include participants from different locations and backgrounds, and allowing students to complete the survey at their own convenience; (2) cost and time efficiency – the online survey was more cost-effective and time-efficient compared to traditional methods such as face-to-face interviews or mailed questionnaires; thus allowing the researchers to collect data from a relatively large sample size within a reasonable timeframe; (3) anonymity and honest responses – especially for the sensitive topic under investigation, there was a belief that participants may feel more comfortable providing honest and candid responses in an online survey compared to face-to-face interactions; thus the online survey promoting openness, potentially leading to more accurate and unbiased information about the participants’ experiences; (4) ease of data collection and management – where Google Forms offered features that streamline data collection and management; with the digital format facilitating the organization of data, reducing the likelihood of errors associated with manual data entry; and (5) standardization of data collection – the online survey ensured that each participant received the same set of questions, minimizing variations in data collection.

2.6 Procedure

Prior to commencing any form of interaction with data collection and participants, the researchers obtained ethical clearance. Written permission to conduct the study on the SLH students was secured from the Heads Departments. Following obtaining written permission from the two Heads of Department, a pilot study was conducted. The pilot study was conducted on three participants (two second year, and one fourth year students) to determine the appropriateness of the data collection tool in terms of length, content, and structure, among other areas. This was ultimately to allow for the identification of errors and discrepancies in the survey, and to obtain valuable information and feedback from another’s perspective as well as suggestions for improvement of the tool (Lowe, 2019). Feedback from the pilot study was then used to refine the tool into its final state. The feedback from the pilot study indicated that the survey was well-structured and highly relevant, and a suggestion was made for a middle ground to be added to “yes or no” questions.

Once the survey was finalized, a link to the survey was disseminated directly to potential participants’ student emails by the Registrar’s office and departmental administrators who had sent out email communication to students inviting them to participate in the study. Participation was voluntary and students’ consent to participate was confirmed by their completion of the survey.

2.7 Ethical considerations

The research adhered to ethical principles outlined in the 2001 revised Declaration of Helsinki and received clearance from the University of the Witwatersrand’s Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol number: STA_2022_10). Participants volunteered willingly, with the option to decline or withdraw without consequences, and were assured of confidentiality and anonymity due to the sensitive nature of the study. Data were collected and stored securely, with responses viewed anonymously, and only the research supervisor received the results. To address potential emotional distress, contact details for university counselling services were provided. Measures were taken to mitigate conflicts of interest, excluding direct colleagues from the participant pool and maintaining a reflective journal. The researcher ensured respect for participants’ rights and refrained from data collection without official permissions.

2.8 Data analysis

The structure and composition of the survey allowed for both descriptive and qualitative data to be obtained. Therefore, data analysis comprised both quantitative and qualitative analysis methods (Creswell and Hirose, 2019). For analysis of the quantitative component, descriptive analysis was employed in the form of descriptive statistics. For a detailed, and in-depth representation of EAL student experiences, a qualitative analysis of the open-ended questions was conducted by way of thematic analysis guided by the six-phase approach to thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (2006) that include familiarizing oneself with the data; generating initial codes; searching for themes; reviewing potential themes; defining and naming themes; and producing the report.

2.9 Rigor/trustworthiness

Trustworthiness and rigor were assured by paying careful cognizance to integrity and competence, comprehensive and thorough planning, and the selection of an appropriate methodology (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane, 2006). This included a pilot study, maintaining credibility, engaging in peer debriefing, and practicing reflexivity during the research process.

3 Results and discussion

The demographic profile of the participants is presented. This profile includes age, gender, degree program, year of study, race, linguistic profile, history of preexposure to English, and province and setting of high school education.

3.1 Participant description and demographics

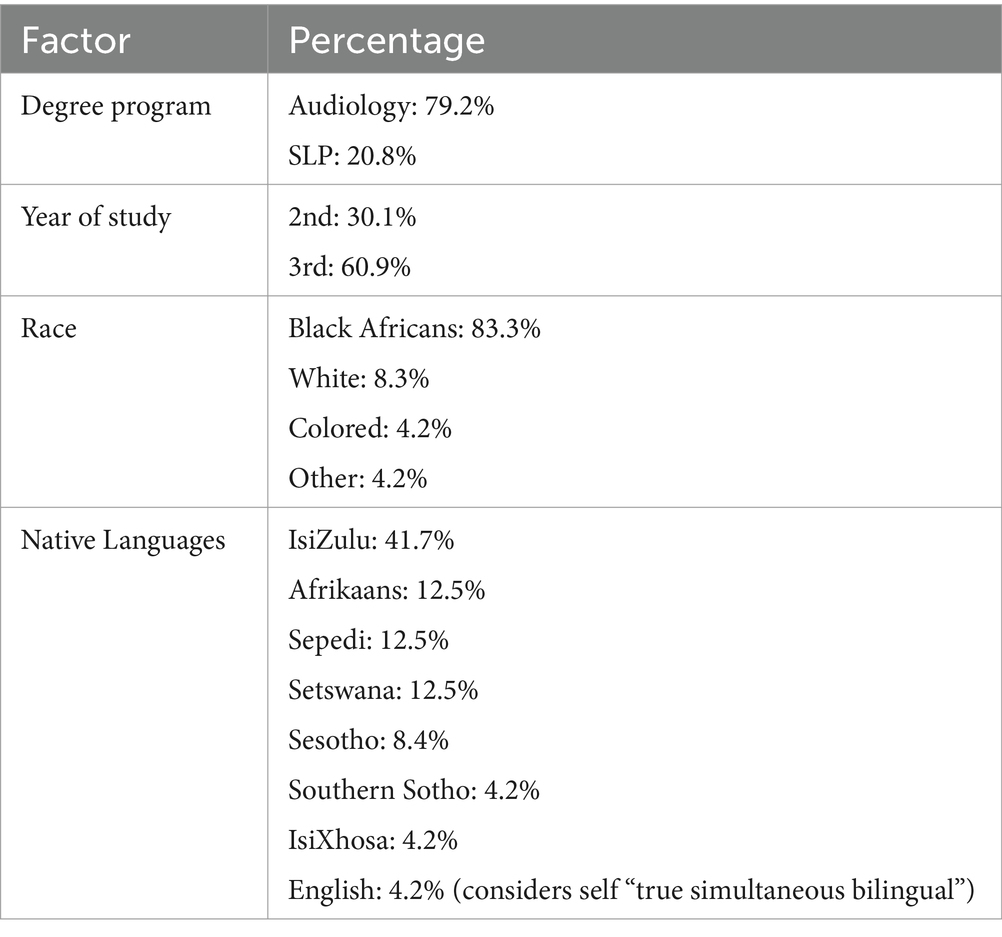

In comparison to the estimated sample size of approximately 30 participants meeting the inclusion criteria, the response rate was 80%. The pool of 24 participants consisted of students with a diverse demographic profile as depicted in Table 1.

All 24 participants were females over the age of 18, which was an expected outcome considering females account for the majority of the SLH student cohort and the professions themselves in South Africa (Pillay et al., 2020). Moreover, as per the inclusion criteria, all participants were EAL and registered students at the University. As depicted in Table 1, the profile of participants consisted of both Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology students, with the majority (79.2%) being the Aud group, and most students coming from the third-year level of study (60.9%). The 1:5 SLP/Audiology ratio is a reflection of the demographic profile of the student body in the two programs at the time of data collection; where the audiology program had more diversity than the SLP program. The racial composition of the group comprised mainly of Black African students (83.3%). This reflects South Africa’s population demographic profile which is largely composed of Black Africans who represent the majority in the country (Statistics South Africa, 2020). It also accurately represents the racial composition of the student body at the University (WITS Facts and Figures, 2020/2021).

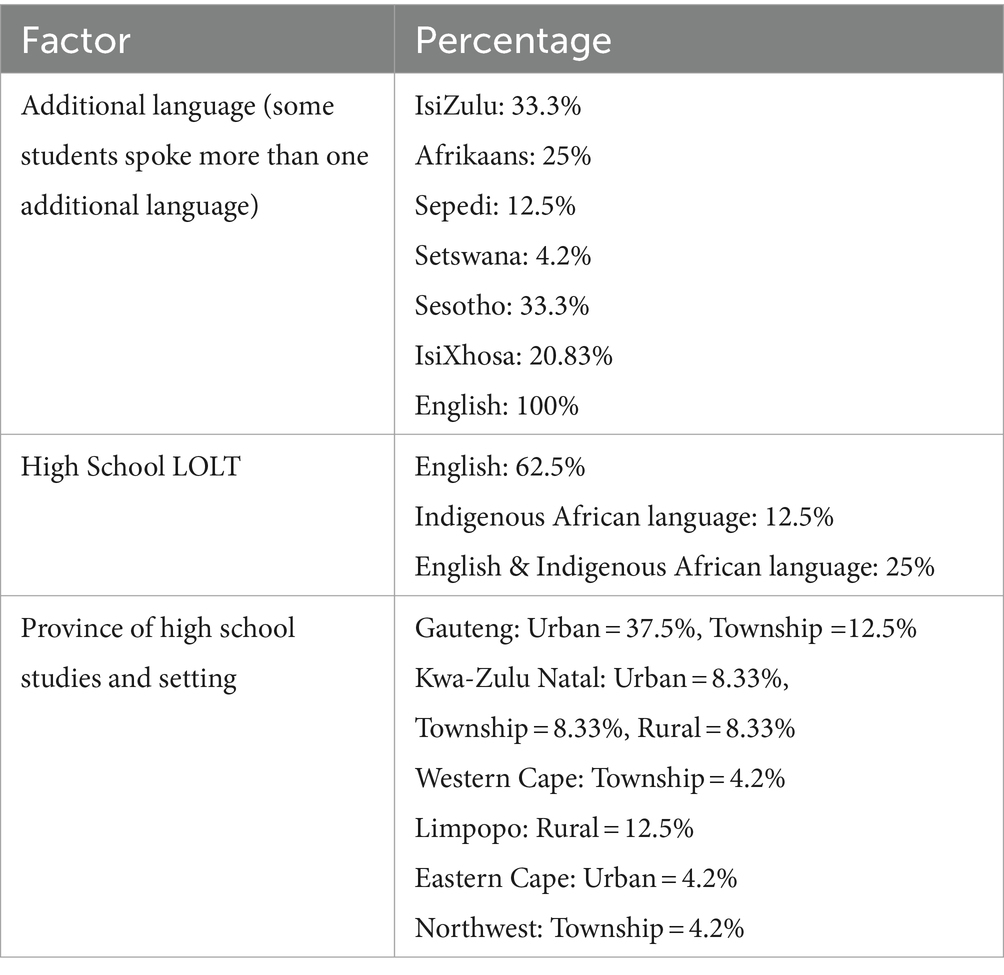

In addition to these demographic areas, participants were requested to provide some linguistic background – information highly pertinent to this study. In terms of the participants’ native language, the results indicate that a large number of the participants were native isiZulu speakers (41.7%). This was an expected statistic considering IsiZulu is the most widely spoken language in South Africa of the official languages (Statistics South Africa, 2020). The only spoken official languages that are not represented in the data are isiSwati, Xitsonga, and Tshivenda.

As an arguably positive outcome of residing in a diverse nation, apart from English, which is inevitably spoken, most participants indicated that they spoke at least one additional official South African language. Although all the participants were originally from South Africa, they completed their pre-tertiary studies in various locales across the country (see Table 2). Amid this, 50% indicated that their school was in an urban area while the remaining half reported schooling in a township and rural settings, respectively. In evident relation to the different geographic profiles, the participants were also educated in different languages at their respective schools. A large percentage was taught purely in English (62.5%) while other participants were taught in either exclusively indigenous languages (12.6%) or a merge of an indigenous language and English (25.1%). Moreover, the overwhelming majority were exposed to English through some kind of medium while growing up. Results related to the linguistic, residential, and schooling profile of the participants are reflected in Table 2.

The current profile, over and above being representative of the SLH EAL population of the university, is also representative of the entire university’s student profile and the South African population in terms of racial composition and linguistic profile (Statistics South Africa, 2020). This is also consistent with statistics and studies acknowledging the slight progress in transformation in terms of the racial profile of tertiary South African universities becoming more reflective of the country’s racial demographics (Kaburise, 2014; South African Government News Agency, 2017; Khoza-Shangase and Mophosho, 2021).

The increase in Black and Colored students, specifically in the SLH degree programs as observed in the current study, supports, and provides an update on previous findings that indicate that for several years the degree programs were under-representative of people of color, but are beginning to gradually change (Khoza-Shangase and Mophosho, 2018, 2021). In fact, it can be posited that (at least at this University), these demographics have significantly shifted to become more representative of the South African society. This change is positive and promising as it implies that the professions have the potential to become less racially and linguistically homogenous over time; therefore, better serving the diverse South African population (Pascoe et al., 2018; Pillay et al., 2020). However, with this positive change in terms of access are implications for more efforts to understand and respond to EAL SLH students’ experiences and more support on the part of the SLH departments within the university to ensure their success.

With regards to preexposure to English, contrary to Linake and Mokhele’s (2019) study that demonstrated little to no preexposure of EAL university students to English as a language of learning and teaching (LOLT), findings in the present study show that the EAL students were exposed to English as a LOLT during their pre-tertiary studies. This preexposure was, however, to varying degrees among the participants, when looking at the distribution in the various provinces and settings in which they completed their high school education– for some rural, and for others urban, or township settings.

It is generally known that the type of spoken English varies from place to place, with those coming from more urban areas most likely being exposed to more native-level English than those in rural areas or townships (Mutepe et al., 2021). This can also be seen in the manner in which some participants’ schools facilitated teaching by means of a combination of English and an indigenous African language. For a student from such an educational background, despite having been exposed to English, lacunae may still exist in their comprehension of highly academic and native-level English, especially with no supplementary Indigenous language input. Therefore, this type of student is likely to fall within the category of EAL speakers who understand and speak English competently at a social level but may have compromised academic competency in the language (Chen, 2015; Hall, 2019).

This further shows the extent to which the SLH programs are evolving demographically, therefore raising implications for necessary intentional steps by the SLH department at the University to provide support to this group of students based on the rurality factor. This support is necessary from the students’ very point of entry into the programs and throughout their studies as exemplified by Gupta et al. (2022) who suggested support strategies related to academic writing. These support strategies entailed academic staff members providing training to EAL students in terms of appropriate discipline-specific writing via seminars and workshops from the first point of entry into the faculty.

3.2 Exploring EAL students’ experiences with regards to engagement with academic content in their curriculum

Current demographic profile data indicate that a significant portion of the participants in the study were not encountering English for the first time in their first year in the SLH programs. However, despite this “pre-exposure,” nearly half of the participants (45.8%) reported deficiencies of some degree in their proficiency in the language. In response to the question about whether participants felt they were confident speaking in their current LOLT, findings demonstrate that although there is considerable proficiency in the LOLT, inadequacies still exist, where only 53% of the sample felt confident in speaking in English. This aligns with empirical evidence highlighting that proficiency in the social and conversational aspect of an additional language does not equate to nor assure adequacy in the written, abstract, and academic components (Teemant, 2010; Chen, 2015; Hall, 2019). This is a distinction that is widely underestimated, as the day-to-day understanding and use of the language is often mistaken for native-like competency, leaving additional language students, unnoticeably disadvantaged and unsupported (Bhatia, 2004; Ip, 2017). What these findings imply for the SLH programs is for the departments to be cognizant of these differences and to have supportive measures in place to assist this group of students to achieve academic proficiency for success in the programs.

When exploring the perceived impact of English proficiency on participants’ understanding of lectures (Figure 1), most (41.7%) agreed that their understanding of lectures was affected by proficiency in the language, 33.3% indicating that their understanding was impaired by proficiency only to an extent, with only 25% expressing no impact. These results are consistent with findings by Pappamihiel (2002), Datta (2012), Chen (2015), and Hall (2019) who reported EAL students’ difficulties with academic learning and lectures due to divided cognitive resources when interchangeably operating between one’s first language (L1)and second language (L2). These findings should not be overlooked, as they flag significant concern considering the importance lectures bear in setting a foundation for understanding academic content, from which further knowledge and understanding can be constructed (Schmidt et al., 2015); and in this group specifically clinical knowledge and understanding required when assessing and treating patients with communication disorders.

When exploring the effect of proficiency on academic writing standard, as depicted in Figure 1, only 20.8% expressed no impact, while most of the respondents (54.2%) reported it was a challenge only to an extent, with a quarter (25.1%) solidly agreeing that proficiency affected their academic writing. These responses are consistent with Sidman-Taveau and Karathanos-Aguilar (2015), Flowerdew (2019), and Gupta et al.’s (2022) findings that academic writing forms an additional area of burden for additional language students. This is bearing in mind the well documented challenges with academic writing faced even by students for whom English is a native language (Tang, 2012; AlMarwani, 2020), who generally encounter challenges with generic academic writing competency. These academic writing challenges are doubled for EAL students (Ip, 2017; Gupta et al., 2022).

As far as the perceived impact on examinations was, similarly, only 25% of the sample reported proficiency not presenting as a challenge. Over half of the respondents (58.3%) expressed experiencing challenges with examinations to an extent, while some participants (16.7%) absolutely reported having trouble with examinations due to their proficiency in English as also reported by Pappamihiel (2002), Bolderston et al. (2008), Chen (2015), Almurideef (2016), Hall (2019), and Mutepe et al. (2021). These findings are similar to those by Teemant (2010) that revealed the layered challenges faced by English as a Second Language (ESL) students when undertaking written assessments such as tests and examinations when students’ perspectives on testing practices at a university in the United States of America was investigated. A similar trend was found with the impact of proficiency on assignments, although less students felt their English proficiency had an impact on their understanding of assignments, a finding that the current researchers believed was influenced by the amount of time that the students have to work on assignments when compared to understanding in examinations and lectures. The flexibility that assignments offer in terms of sufficient time and space to comprehensively engage with complex written terminology, seek assistance, and carefully produce academically acceptable responses by drawing from various sources, could be the influencing factor leading to enhanced performance (Latif and Miles, 2020).

When exploring whether the undergraduate students believed that the curriculum is accommodating of different levels of English proficiency, a striking 70.8% firmly felt the nature of the curriculum is not accommodating of varying student proficiency in the LOLT. This is consistent with literature in the area of transformation that has frequently outlined the rigidity of tertiary curriculums in accommodating the existing and increasing diversity of the student body in institutions (Kaburise, 2014; Seabi et al., 2014; Khoza-Shangase and Mophosho, 2018). Whilst acknowledging the notable demographic profile progress in transformation, these findings have major implications for actions within the University to ensure curriculum transformation to be responsive and relevant to the context, as it appears there remains significant room for more accommodation of the previously disadvantaged in terms of language and culture.

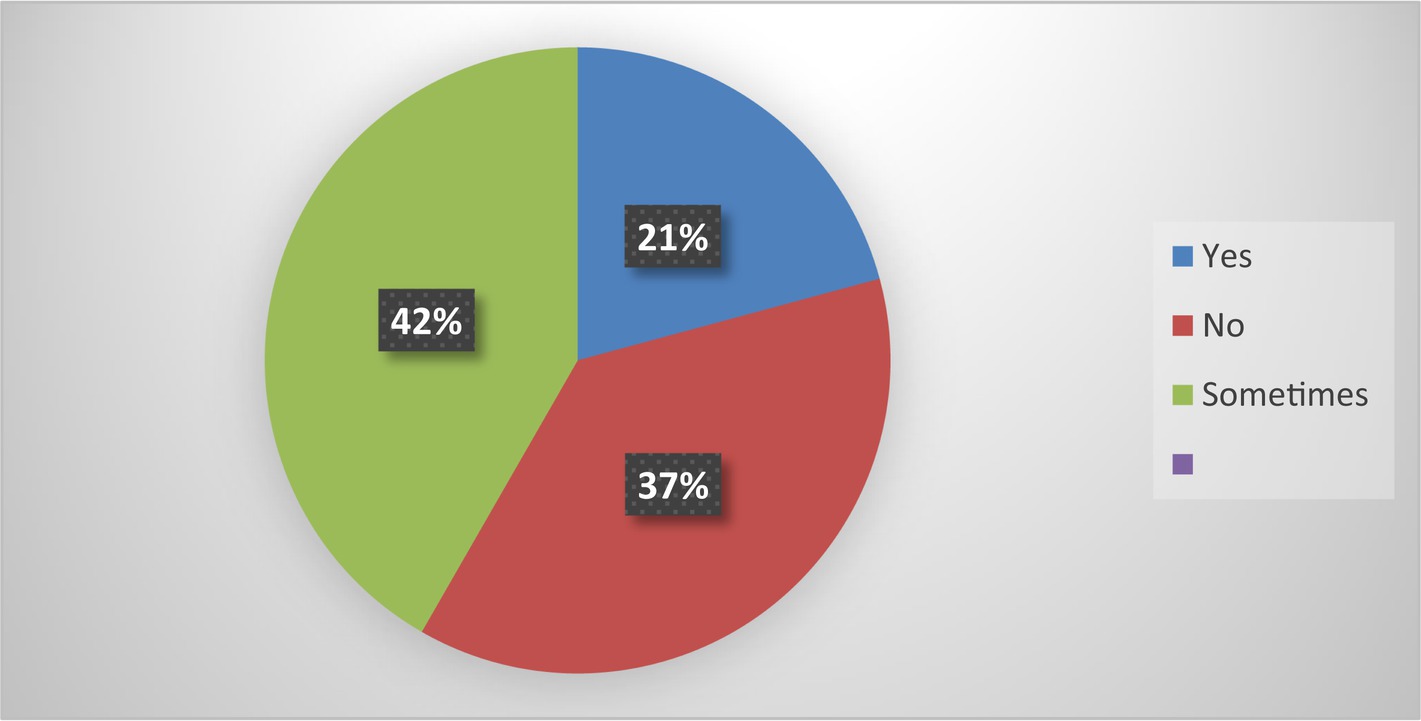

Interestingly, only 21% of the participants felt that oral presentations were impacted by proficiency in LOLT, with only 20.8% expressing challenges with oral presentation tasks all the time. However, the majority (41.7%) experienced difficulty with oral tasks only occasionally (see Figure 2). Therefore, for these participants, proficiency seemed to only affect oral presentation tasks to a minor extent. This contradicts existing evidence by Pappamihiel (2008), Chen (2015), and Pabro-Maquidato (2021), where EAL students reported high levels of difficulty and anxiety when required to engage in oral tasks. The mismatch of findings between the present study and previous studies could be attributed to the contextual differences between EAL students in the present study and those in the previous studies. The EAL students in the present study (having lived in South Africa from birth) had a degree of exposure to English prior to their university studies while students in the previous studies were encountering English for the first time in a foreign country. Furthermore, over and above the contextual differences, these findings reiterate what Bhatia (2004) and Ip (2017) argue is the underestimation of the distinction between the day-to-day understanding and use of the language and native-like competency. This may imply that the type and degree of support required for the EAL students in the current study would differ from that needed for EAL students in previous studies. Nonetheless, this perceived reduced level of difficulty with oral tasks reported by EAL students in the current study is understandable considering the verbal use of language is less grammatically demanding when compared to writing and reading (Datta, 2012).

A notable 58.3% of participants were clear in expressing that their academic performance would be enhanced if learning and teaching occurred in their home language. This further demonstrates an existing relationship between language proficiency and the understanding of academic lingo, and overall performance (Teemant, 2010; Aina et al., 2013; Ghenghesh, 2015). This finding supports previous findings by Pappamihiel (2008) who observed that EAL students demonstrated an improvement in performance when in ESL classrooms than in mainstream English classrooms. However, in the present study, one participant did not concur, stating that their home language (isiXhosa) is already challenging as is and that applying it academically would not prove advantageous for her. This is a valuable outlying point of diversion that may need to be weighed in during considerations around language transformation actions within tertiary institutions in South Africa.

When participants were asked to propose an ideal method of teaching, learning, and assessment that they thought would work better for an EAL student, and when they were further asked to share any other thoughts related to their academic experiences, two themes emerged from the narrative responses, namely, (1) blended-language teaching and learning approach, and (2) simplification of concepts and terminology to an “EAL level.” This additional input reinforces the quantitative findings that revealed that several of the participants found significant difficulty following lectures, which is supported by existing evidence (Datta, 2012; Chen, 2015).

3.3 Theme 1: blended-language teaching and learning approach

Numerous participants suggested it would make a tremendous and progressive difference if the language mode used for teaching and learning interactions would be made a combination of English and Indigenous South African languages. This was not necessarily a demand for the eradication of the current LOLT, but rather for the complementary use of Indigenous languages to aid learning and to foster improved understanding of academic content. These suggestions are mirrored in some of the responses shown below:

“The inclusion of multiple languages or means of explaining, representing, and assessment of the learning language.” (Participant 2)

“[…] for instructions of tasks to be given in multiple languages.” (Participant 20)

“A method whereby concepts are taught in English and if the students have difficulty understanding the concept then the students’ native language is used to aid teaching”. (Participant 14)

This suggestion of blended-language teaching and learning agrees with the existing body of literature around EAL students (Janulevičienė and Kavaliauskienė, 2000; Fachriyah, 2017; Ndawo, 2019; Maja and Motseke, 2021). Janulevičienė and Kavaliauskienė (2000) reported that participants responded favorably to the idea of native language use in the English classroom for particular purposes, including the explanation of difficult concepts and the introduction of new material. However, it must be noted that the context from which these findings stemmed was that of younger students who were learning English for the first time, and not necessarily university students with some pre-exposure to English as in the present study. Fachriyah (2017) illustrated the beneficial use of code-switching in the classroom to confirm and clarify explanations to eliminate misunderstandings between EAL students and their teachers. Most recently, the same code-switching strategy was proposed by Maja and Motseke (2021). Ndawo’s (2019) study also briefly provided a recommendation given by participants, suggesting that EAL students be permitted the opportunity to speak their Indigenous languages while those fluent in the LOLT assist with translation to aid with learning. The use of other students to assist with translation has its own challenges, which would need to be acknowledged and addressed.

Within the South African context, limited evidence exists on the utilization of blended-language teaching and learning approach. As supported by Janulevičienė and Kavaliauskienė’s (2000) findings, what is ultimately being suggested by the participants is continuation of the use of LOLT but with an added layer of support for introducing new concepts and for explaining content that is rather difficult. The use of both the L1 and LOLT could mean enhanced understanding of content, retained meaning, and therefore, improved academic outcomes (Ndawo, 2019). This proposed approach may be unconventional and exigent in execution, particularly since the profile of lecturers remains largely English speaking themselves, thus requiring additional staff as co-assistants who speak the requisite L1. However, it may be a promising stride toward academically accommodating students with varying linguistic backgrounds and may have significant implications for epistemological access as well.

3.4 Theme 2: simplification of concepts and terminology to an “EAL level”

Among the suggestions made by participants, there was an expression that participants’ understanding of academic content would be improved if terminology used to introduce and explain concepts were simplified by lecturers or explained, rather than the present use of complex terms and phrases. The following excerpts encapsulate this:

“Use of English to teach us and not the complex one.” (Participant 21)

“I think it would be beneficial to be provided with translations of terms that are used frequently […].” (Participant 20)

“[…] have the lecturers explain uncommon words.” (Participant 8)

“There is no need for lecturers to teach new concepts using complicated big words and phrases. When you teach new concepts you need to put in the simplest format. Additionally, it’s ridiculous using unfamiliar big words in test because if you don’t know the meaning of one of the words in the question you completely loose the context of the question”. (Participant 4)

The idea behind this theme is closely related to that of the preceding theme in that it nudges at some form of effort on the part of the SLH departments and lecturers. However, unlike the previous theme, this theme is directed toward the use of English as a LOLT (as is presently) but accompanied by the intentional assistance of EAL students. In other words, what is suggested is that focused support be provided to EAL students during lectures and for examinations via the simplification of terms used to introduce concepts, the translation of unusual terms, and the use of simple, commonly understood terminology in tests.

As far as the proposition for the simplification of terms when introducing new concepts is concerned, Kremer and Valcke (2014) present different strategies adopted by students and their educators in enhancing lecture understanding. Among these strategies is that of lecturers simplifying the language used during lectures, as proposed in the current study. Kremer and Valcke (2014) also recommend providing explanations for less common words and main concepts to students. Additionally, participant 20 raised an additional alternative strategy of having lecturers make available the translations of terms that are likely to be used in lectures. This idea supports a coping strategy offered in Kremer’s (2021) study which entailed the development of supporting material, such as glossaries, that outline the definitions of terms that are most relevant to the students’ courses. Collectively, these findings raise implications for the development and application of strategies (and material) by lecturers to simplify EAL students’ access to information during lectures as far as practically possible.

Some participants, however, added to the responses by instead providing suggestions applicable to and pointing responsibility toward the EAL student in mitigating challenges with unfamiliar terms encountered. The following responses are examples of this:

“Find the meanings of frequently used vocabulary to familiarize yourself with them” (Participant 4)

“Writing down notes using the jargon that you use daily in your social settings” (Participant 22)

These findings demonstrate a sense of self-responsibility and effort that some EAL students have assumed as a strategy to cope in response to the existing academic language challenges. This posture of self-determination to resist being disadvantaged due to LOLT inadequacy is similar to strategies employed by EAL students in studies by Wold (2006), Rabea et al. (2018), and Pabro-Maquidato (2021). EAL students in Rabea et al.’s (2018) study persistently made personal efforts to improve their language abilities so that it did not interfere with their academic outcomes and maintained an ambitious attitude to avoid perceiving their proficiency as an insurmountable obstacle. The participants essentially felt that active efforts on the part of an EAL student to improve their academic understanding and performance overall may also make a significant difference in their academic experience. Pabro-Maquidato (2021) also noted the initiative taken by EAL participants which included actively engaging in tasks to overcome their perceived challenges, by for example, seeking feedback, reading English books, and referring to the dictionary. Similarly, in a single-participant study, Wold’s (2006) participant identified her language weaknesses and took the necessary steps to address them, some of which involved efforts to speak more English than her native language to improve. These findings have implications for the accountability, personal initiative, and effort that EAL SLH students ought to engage toward enhancing their academic experiences to meet departmental efforts halfway. Current authors, however, feel that this should only be over and above the concrete measures made by training programs to transform the curriculum to make it more Afrocentric, thus more relevant, and responsive to the context.

Overall, where an 80% response rate from a diverse group of 24 participants that were representative of the demographic profile of the SLH professions, the broader university and national demographics the current study yielded important findings. Regarding preexposure to English, contrary to previous studies, this research found that EAL students had varying degrees of exposure during pre-tertiary education across different provinces and settings. The study highlights the evolving demographics in SLH programs, with a positive shift toward increased representation of Black and Colored students. Despite this progress, challenges persist, as 45.8% of participants reported proficiency deficiencies in English, impacting academic aspects such as lectures (41.7%), academic writing (54.2%), examinations (58.3%), and assignments (41.7%). Participants felt the current curriculum inadequately accommodated varying English proficiency levels, emphasizing the need for transformative measures. While oral presentations were perceived as less impacted by proficiency (21%), academic performance was believed to improve if teaching occurred in participants’ home language (58.3%). Two prominent themes emerged from participants’ suggestions for improvement: a blended-language teaching approach and the simplification of concepts and terminology to an “EAL level.” The majority (70.8%) felt the curriculum was not accommodating, emphasizing the importance of tailored support for EAL students in SLH programs. In summary, the study reveals challenges in English proficiency affecting various academic aspects. The findings underscore the importance of adapting teaching methods and curriculum to better support EAL students, promoting inclusivity and academic success in SLH programs.

4 Conclusion

With results revealing that the SLH student population is becoming increasingly diverse, current findings indicating less than satisfactory academic experiences of EAL students within the SLH training programs in South Africa need to be carefully considered by training programs as well as regulatory bodies. Training programs that are intent on productive, and not cosmetic transformation efforts can benefit from the insights expressed by current undergraduate students to address the pedagogy as well as the curriculum challenges raised by current findings. Findings indicating that EAL students in these programs require support in terms of measures aimed at mitigating the negative influence of proficiency in the language of the LOLT on academic success need noting, and the specificity of the support toward lectures and examinations aids in focusing the limited resources that programs in low-middle-income countries, such as South Africa. The valuable recommendations made around pedagogical strategies and curriculum reform need deliberating on within this context to facilitate academic success and epistemological access. Key implications raised by the study for SLH programs, suggest the need for tailored support to address challenges in English proficiency and creation of an inclusive learning environment. Curriculum modifications, such as a blended-language teaching approach, can enhance academic accessibility for EAL students. The findings contribute to ongoing efforts to foster diversity and inclusivity in SLH programs, ultimately improving the educational experiences of EAL students. Clearly, the smaller-than-expected sample size, potential response bias in self-reported data, and the cross-sectional design limiting the examination of longitudinal changes, and the focus on a specific university may restrict the generalizability of findings to other contexts; however current findings can be viewed as preliminary findings for a larger study with proportional representation of SLH students from a number of programs across South Africa.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of the Witwatersrand’s Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

KK-S: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1258358/full#supplementary-material

References

Abrahams, F. (2021). Transformation in speech-language and hearing professions in South Africa: Undergraduate students’ perceptions and experiences explored. Unpublished Master’s dissertation. University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. HSRC Press Cape Town.

Abrahams, F., Moroe, N., and Khoza-Shangase, K. (2023). Transformation of higher learning in South Africa: perceptions and understanding of speech-language therapy and audiology undergraduate students. Educ. Change 27:11648. doi: 10.25159/1947-9417/11648

Aina, J. K., Ogundele, A. G., and Olanipekun, S. S. (2013). Students’ proficiency in English language relationship with academic performance in science and technical education. Am. J. Educ. Res. 1, 355–358. doi: 10.12691/education-1-9-2

AlMarwani, M. (2020). Academic writing: challenges and potential solutions. Arab World English J. 6, 114–121. doi: 10.24093/awej/call6.8

Almurideef, R. (2016). The challenges that international students face when integrating into higher education in the United States. Theses and Dissertations. Available at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/2336

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (2018). Scope of practice in audiology [scope of practice]. Available at: www.asha.org/policy/

Bolderston, A., Palmer, C., Flanagan, W., and McParland, N. (2008). The experiences of English as second language radiation therapy students in the undergraduate clinical program: perceptions of staff and students. Radiography 14, 216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2007.03.006

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chen, Y. (2015). ESL students' language anxiety in in-class oral presentations. Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Available at: https://mds.marshall.edu/etd/962

Cheng, L., and Fox, J. (2008). Towards a better understanding of academic acculturation: second language students in Canadian universities. Can. Modern Lang. Rev. 65, 307–333. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.65.2.307

Chetty, R. (2012). The status of English in a multilingual South Africa: gatekeeper or liberator. Teaching English Today :4.

Civan, A., and Coskun, A. (2016). The effect of the medium of instruction language on the academic success of university students. Educ. Sci. 16, 1981–2004, doi: 10.12738/estp.2016.6.0052

Creswell, J. W., and Hirose, M. (2019). Mixed methods and survey research in family medicine and community health. Family Med. Commun. Health 7:e000086. doi: 10.1136/fmch-2018-000086

Datta, S. (2012). The effect of language barrier on students’ academic performance. Available at: https://www.csuohio.edu/sites/default/files/60%20The%20effect%20of%20language%20barrier%20on%20students%27%20academic%20performance.pdf

Fachriyah, E. (2017). The functions of code switching in an English language classroom. Stud. English Lang. Educ. 4, 148–156. doi: 10.24815/siele.v4i2.6327

Fereday, J., and Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 5, 80–92. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500107

Flowerdew, J. (2019). The linguistic disadvantage of scholars who write in English as an additional language: myth or reality. Lang. Teach. 52, 249–260. doi: 10.1017/S0261444819000041

Foster, P., and Ohta, A. S. (2005). Negotiation for meaning and peer assistance in second language classrooms. Appl. Linguis. 26, 402–430. doi: 10.1093/applin/ami014

Ghenghesh, P. (2015). The relationship between English language proficiency and academic performance of university students–should academic institutions really be concerned? Int. J. Appl. Linguist. English Liter. 4, 91–97. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.2p.91

Gupta, S., Jaiswal, A., Paramasivam, A., and Kotecha, J. (2022). Academic writing challenges and supports: perspectives of international doctoral students and their supervisors. Front. Educ. 7:891534. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.891534

Hall, G. (2019). The experiences of secondary school students with English as an additional language: perceptions, priorities and pedagogy. British Council. Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/J154%20ELTRA_Secondary%20Students%20Eng%20as%202nd%20Lang%20Paper_A4_FINAL_web.pdf

Hyman, M. R., and Sierra, J. J. (2016). Open-versus close-ended survey questions. Business Outlook 14, 1–5.

Ip, T. (2017). Academic writing in a second or foreign language: issues and challenges. JALT Lang. Teach. 41.

Janulevičienė, V., and Kavaliauskienė, G. (2000). To translate or not to translate in teaching ESP? J. English Lang. Teach. Educ. 3, 9–13.

Kaburise, P. (2014). Why has widening access to tertiary, in South Africa, not resulted in success? Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 5:1309. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p1309

Kagwesage, A. M. (2013). Coping with English as language of instruction in higher education in Rwanda. Int. J. Higher Educ. 2, 1–12, doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v2n2p1

Khoza-Shangase, K. (2019). “Intellectual and emotional toxicity: where a cure does not appear to be imminent” in Black academic voices: the South African experience. eds. K. K.-S. Phaswana and H. Canham, 42–64.

Khoza-Shangase, K., and Mophosho, M. (2018). Language and culture in speech-language and hearing professions in South Africa: the dangers of a single story. South African J. Commun. Disord. 65, 1–7. doi: 10.4102/sajcd.v65i1.594

Khoza-Shangase, K., and Mophosho, M. (2021). Language and culture in speech-language and hearing professions in South Africa: re-imagining practice. South African J. Commun. Disord. 68, 1–9. doi: 10.4102/sajcd.v68i1.793

Kremer, M. (2021). When the teaching language is not the mother tongue: Support of students in higher education. Doctoral dissertation, Ghent University).

Kremer, M., and Valcke, M. (2014). Teaching and learning in English in higher education: a literature review. In 6th international conference on education and new learning technologies (EDULEARN) 1430–1441. International Association of Technology, Education and Development (IATED).

Latif, E., and Miles, S. (2020). The impact of assignments and quizzes on exam grades: a difference-in-difference approach. J. Stat. Educ. 28, 289–294. doi: 10.1080/10691898.2020.1807429

Linake, M. A., and Mokhele, M. L. (2019). English first additional language: students' experiences on reading in one south African university. e-BANGI 16, 199–208.

Lowe, N. K. (2019). What is a pilot study? J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 48, 117–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2019.01.005

Maja, M. M., and Motseke, M. (2021). “Strategies used by UNISA student teachers in teaching English first additional language” in Higher education-new approaches to accreditation, digitalization, and globalization in the age of Covid. (IntechOpen). doi: 10.5772/intechopen.99662

Martirosyan, N. M., Hwang, E., and Wanjohi, R. (2015). Impact of English proficiency on academic performance of international students. J. Int. Stud. 5, 60–71. doi: 10.32674/jis.v5i1.443

McDermid, F., Peters, K., Jackson, D., and Daly, J. (2014). Conducting qualitative research in the context of pre-existing peer and collegial relationships. Nurse Res. 21, 28–33. doi: 10.7748/nr.21.5.28.e1232

Mutepe, M., Makananise, F. O., and Madima, S. E. (2021). Experiences of first-year students with using English second language for teaching and learning at a rural based University in a Democratic South Africa. Gender Behav. 19, 17795–17803.

Naicker, C. (2016). From Marikana to# feesmustfall: the praxis of popular politics in South Africa. Urbanisation 1, 53–61. doi: 10.1177/2455747116640434

Ndawo, G. (2019). The influence of language of instruction in the facilitation of academic activities: nurse educators’ experiences. Health SA Gesondheid 24, 1–10. doi: 10.4102/hsag.v24i0.1261

Oducado, R. M., Sotelo, M., Ramirez, L. M., Habaña, M., and Belo-Delariarte, R. G. (2020). English language proficiency and its relationship with academic performance and the nurse licensure examination. Nurse Media J. Nurs. 10, 46–56. doi: 10.14710/nmjn.v10i1.28564

Pabro-Maquidato, I. M. (2021). The experience of English speaking anxiety and coping strategies: a transcendental phenomenological study. Int. J. TESOL Educ. 1, 45–64.

Pappamihiel, N. E. (2002). English as a second language students and English language anxiety: issues in the mainstream classroom. Res. Teach. Engl. 36, 327–355.

Pappamihiel, N. E., Nishimata, T., and Mihai, F. (2008). Timed writing and adult English‐language learners: An investigation of first language use in invention strategies. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. 51, 386–394.

Pascoe, M., Klop, D., Mdlalo, T., and Ndhambi, M. (2018). Beyond lip service: towards human rights-driven guidelines for south African speech-language pathologists. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 20, 67–74. doi: 10.1080/17549507.2018.1397745

Pillay, M., and Kathard, H. (2015). Decolonizing health professionals' education: audiology & speech therapy in South Africa. African J. Rhetoric 7, 193–227.

Pillay, M., Tiwari, R., Kathard, H., and Chikte, U. (2020). Sustainable workforce: south African audiologists and speech therapists. Hum. Resour. Health 18, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00488-6

Rabea, R., Almahameed, N. A., Al-Nawafleh, A. H., and Obaidi, J. (2018). English language challenges among students of Princess Aisha Bint Al-Hussein college of nursing & health sciences at Al-Hussein bin Talal university. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 9, 809–817. doi: 10.17507/jltr.0904.19

Sanner, S., Wilson, A. H., and Samson, L. F. (2002). The experiences of international nursing students in a baccalaureate nursing program. J. Prof. Nurs. 18, 206–213. doi: 10.1053/jpnu.2002.127943

Schmidt, H. G., Wagener, S. L., Smeets, G. A., Keemink, L. M., and van Der Molen, H. T. (2015). On the use and misuse of lectures in higher education. Health Profess. Educ. 1, 12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.hpe.2015.11.010

Seabi, J., Seedat, J., Khoza-Shangase, K., and Sullivan, L. (2014). Experiences of university students regarding transformation in South Africa. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 28, 66–81.

Sidman-Taveau, R., and Karathanos-Aguilar, K. (2015). Academic writing for graduate-level English as a second language students: experiences in education. CATESOL J. 27, 27–52.

South African Government News Agency (2017). Transformation in higher education institutions commended. Retrieved from Transformation in higher education institutions commended|SAnews

Statistics South Africa (2020). 60,6 million in South Africa. Available at: www.statssa.gov.za

Suveren, D. (2019). The colonization of South Africa and the British impacts on development. Retrieved from the-colonization-of-south-africa-and-the-british-impacts-on-development.pdf. Available at: researchgate.net

Tang, R. (2012). The issues and challenges facing academic writers from ESL/EFL contexts: an overview. Academic writing in a second or foreign language: issues and challenges facing ESL/EFL academic writers in higher education contexts, 1-18.

Teemant, A. (2010). ESL student perspectives on university classroom testing practices. J. Scholarship Teach. Learn. 10, 89–105.

Tshotsho, B. P. (2006). An investigation into English second language academic writing strategies for black students at the eastern cape technikon. Doctoral dissertation, University of the Western Cape.

WITS Facts and Figures (2020/2021). WITS Facts and Figures. Available at: https://www.wits.ac.za/media/wits-university/about-wits/documents/WITS%20Facts%20%20Figures%202020-2021%20Revised%20Hi-Res.pdf

Wold, J. B. (2006). Difficulties in learning English as a second or foreign language. All Regis University Theses. Available at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/333

Keywords: Afrocentric, higher education, responsive curriculum, language of learning and teaching, diversity

Citation: Khoza-Shangase K and Kalenga M (2024) English additional language undergraduate students’ engagement with the academic content in their curriculum in a South African speech-language and hearing training program. Front. Educ. 9:1258358. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1258358

Edited by:

Javad Gholami, Urmia University, IranReviewed by:

Raghad Fahmi Aajami, University of Baghdad, IraqZhila Mohammadnia, Urmia University, Iran

Mikateko Ndhambi, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, South Africa

Nasim Banu Khan, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Copyright © 2024 Khoza-Shangase and Kalenga. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katijah Khoza-Shangase, S2F0aWphaC5LaG96YS1TaGFuZ2FzZUB3aXRzLmFjLnph

Katijah Khoza-Shangase

Katijah Khoza-Shangase Margo Kalenga

Margo Kalenga