- Psychological and Brain Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, United States

The link between intrinsic motivation support from teachers (i.e., teacher support), academic motivation, and academic performance is well documented. However, evidence suggests that racial/ethnic minority students are less likely to perceive support from adults at school, compared to White students. The majority of existing research has emphasized the impact that school-level factors have on racial/ethnic minority students' perceptions of teacher support. However, less research has examined whether students' awareness of racial/ethnic inequality at the socio-structural level may also influence perceptions of teacher support. The present study explores this question and examines whether students' perceptions of race/ethnic based collective autonomy restriction (i.e., the extent to which an individual feels that other groups try and restrict their racial/ethnic groups' freedom to define and express their own social identity) and fair treatment from teachers influence these outcomes. Drawing on cross-sectional survey data from middle and high school students (N = 110), the present study found that racial/ethnic minority students reported greater perceptions of collective autonomy restriction, compared to White students, which mediated the link between students' racial/ethnic identity and perceived teacher support. Furthermore, past experiences with fair treatment from teachers were found to buffer the link between collective autonomy restriction and perceptions of teacher support. The practical implications of these findings for educators to better support students from underrepresented racial/ethnic backgrounds are discussed.

1 Introduction

Intrinsic motivation, or the motivation to engage in behavior to derive personal satisfaction, plays a critical role in students' academic development. For example, students who feel intrinsically motivated to learn - whether to satisfy their own curiosity or to achieve their long-term academic goals - tend to exhibit greater self-efficacy, engagement, motivation, and performance within the classroom (Reeve et al., 2004; Chirkov, 2009; Jang et al., 2009; Ryan and Deci, 2013). Within the classroom, teachers can help support intrinsic motivation development by tailoring the learning experience around their students' learning interests and preferences (Reeve et al., 2004; Kusurkar et al., 2013; Ryan and Deci, 2013). Yet research continuously finds that racial/ethnic minority students (i.e., Black, Indigenous, and Latinx students) are less likely to feel supported in educational settings compared to their White peers (Cabrera et al., 1999; Bottiani et al., 2016).

Extant research on educational racial/ethnic disparities emphasizes the impact that school-level factors (e.g., culturally exclusive school climates, discriminatory experiences with teachers and peers, etc.) can have on racial/ethnic minority students' perceptions of support (Byrd and Chavous, 2011; Benner and Graham, 2013; Smith et al., 2020). In addition to these school-level factors, socio-structural factors that restrict racial/ethnic minority students' access to quality education (e.g., red lining, racial segregation, economic inequality, stereotypes, etc.) can lead racial/ethnic minority students to believe that they “don't belong” in academic environments (Oyserman and Destin, 2010; Oyserman et al., 2011; Oyserman and Lewis, 2017). What remains unclear, however, is whether racial/ethnic minority students' are more aware of socio-structural factors within the U.S. that restrict their racial/ethnic group relative to White students who represent a racial/ethnic majority, and whether this heightened awareness is linked to perceptions of their teachers as supportive of their intrinsic motivational development. In the present study, we explore this question by examining whether students' perceptions of their racial/ethnic groups' freedom to define and practice their own social identity within the U.S. (i.e., collective autonomy) is linked to their perceptions of their teachers as supportive of their intrinsic motivational needs within the classroom. We hypothesize that racial/ethnic minority students are more likely to perceive restriction, and in turn, this will be linked to lower feelings of intrinsic motivation support. We also examine whether positive interactions with teachers and adults at school influence the potential link between students' perceptions of collective autonomy, and intrinsic motivational support from teachers.

1.1 Racial/ethnic collective autonomy

Racial/ethnic collective autonomy refers to the perception that one's racial/ethnic group is free to define and practice its own social identity and culture without interference from other racial/ethnic groups (Kachanoff, 2017). Within the U.S., the unequal distribution of power and resources based on social hierarchy puts racial/ethnic minorities at greater risk of experiencing collective autonomy restriction by others (Kachanoff et al., 2019). As a nation, the U.S. is still reckoning with the impact that slavery, genocide, and racial/ethnic segregation has had on modern policies that perpetuate racial/ethnic inequality at a systemic level. Policies such as the “show me your papers” law in several states (Maggio, 2021); America's “war on drugs” (Fellner, 2009); Trump's Muslim ban (Collingwood et al., 2018); and exclusionary zoning practices (McGahey, 2021; Shertzer et al., 2022) are just a few examples of how institutions of power enact policies that restrict the rights of people of color in the U.S. At the cultural level, forced assimilation to White-Christian American norms, customs, traditions, and values further restricts racial/ethnic minority groups' freedom to practice their culture (Padilla et al., 1991; Comas-Díaz and Greene, 1994; Davis, 2001; Tamura, 2002; Little, 2017; Mitchell, 2017). Considering these pervasive race/ethnic-based inequalities, it is unsurprising that members from racial/ethnic minority groups report greater perceptions of collective autonomy restriction, compared to racial majority group members (Kachanoff et al., 2019). In turn, experiencing collective autonomy restriction has been shown to negatively impact feelings of personal autonomy, self-esteem, and psychological wellbeing among adults from marginalized groups (Kachanoff et al., 2019, 2021). Given that autonomy, self-esteem, and psychological wellbeing are all important predictors of academic motivation and achievement, questions are raised as to whether collective autonomy restriction may influence the academic experience of adolescents through related processes. However, no research has investigated the impact that perceptions of collective autonomy restriction have on the wellbeing and academic motivations of adolescents from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds.

1.2 Uncharted waters: adolescence and collective autonomy restriction

Adolescence is a developmental period when social identity arguably becomes most salient, as youth continue to explore and define their sense of self as they transition into young adulthood (Coleman, 1974; Steinberg and Silverberg, 1986; Huynh and Fuligni, 2010). Relatedly, adolescents of color tend to be hypervigilant toward identity-based discrimination and prejudice, both experienced at the personal level, as well as vicariously through witnessing another individual with a shared social-identity being discriminated against Tarrant et al. (2001), Agnew et al. (2002), Williams and Mohammed (2009), and Louie and Upenieks (2022). Because of this hypervigilance, adolescents of color are likely aware and sensitive to the socio-structural factors in the U.S. that restrict their collective autonomy. Despite these implications, no research has examined adolescent perceptions of collective autonomy restriction, or the downstream consequences on their wellbeing. Furthermore, given that autonomy plays a critical role in shaping students' academic experiences and motivation, we argue that perceptions of collective autonomy restriction may also influence the experience of adolescents of color within the classroom. Specifically, we hypothesize that experiencing racial/ethnic collective autonomy restriction influences student perceptions that their teachers are unsupportive of their intrinsic motivational needs within the classroom. We also examine whether a history of positive interpersonal interactions at school buffers potential links between students' perceptions of collective autonomy restriction, and perceptions of intrinsic motivational support from teachers.

1.3 Teacher fairness: a potential moderator

It is well documented that “fairness” in the classroom (i.e., grading, discipline, and communication) can help foster positive interpersonal relationships between teachers and their pupils (Lowman and Lowman, 1984; Walsh and Maffei, 1994; Chory, 2007). Students are generally more satisfied with their teacher's instructional practices, and report more positive relationships with teachers, when they perceive that the teacher treats students in a fair and just manner (Feldman, 1989; Clayson and Haley, 1990; Rodabaugh and Kravitz, 1994; Houston and Bettencourt, 1999; Gregory and Ripski, 2008). In turn, positive teacher-student relationships can increase academic motivation, achievement, and sense of belonging in school (Hughes, 2011; Allen et al., 2021). Research further suggests that students' racial/ethnic identity adds an additional layer of nuance to our understanding of teacher fairness. On the teacher-behavioral end, racial biases can lead teachers to unintentionally treat students unfairly based on their racial/ethnic identity (Tenenbaum and Ruck, 2007; Glock and Kovacs, 2013; Okonofua et al., 2016; Inan-Kaya and Rubie-Davies, 2022). At the same time, awareness of the potential of being treated unfairly by teachers based on one's racial identity can make racial/ethnic minority students hypervigilant to unfair treatment from teachers (Crystal et al., 2010; Kaufman and Killen, 2022) and may lead them to attribute ambiguous interactions with teachers as racially motivated (Rivera-Rodriguez, 2021). As such, fair treatment from teachers may carry an additional benefit for racial/ethnic minority students, such that it breaks negative expectations that these students may have regarding how they may be treated by teachers and other adults at school. Thus, in the current study, we argue that past exposure to fair treatment from teachers and other adults in schools can help buffer the potentially negative impact of collective autonomy restriction on students' perceptions of teacher support.

1.4 The current study

The current study examined whether perceptions of collective autonomy restriction differed by students' racial/ethnic identity, and tested whether experiencing collective autonomy restriction shaped perceptions of teacher support. It also examined whether previous exposure to fair treatment from teachers attenuated the link between collective autonomy restriction and perceptions of teacher support. Drawing on cross-sectional data from middle and high school students (N = 110), we tested the following hypotheses. First, students of color will report greater perceptions of collective autonomy restriction, compared to White students (H1).1 Second, greater perceptions of collective autonomy restriction will mediate the link between student's racial/ethnic identity and perceived teacher support, such that students of color will be more likely to feel racial/ethnic collective autonomy restriction (compared to White students), which in turn will predict less perceived intrinsic motivation support from teachers (H2). Third, previous exposure to fair treatment from teachers will buffer the negative association between perceived collective autonomy restriction and perceived teacher support (H3).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design

An online survey was used to assess students' perceptions of collective autonomy restriction, perceptions of intrinsic motivation support from their current teacher, and previous exposure to fair treatment from teachers. The survey was administered through our research-partner school during the fall semester of the 2020–21 school year between the dates of October 15th-18th, as part of a broader longitudinal study. At the time of data collection, the school had adopted a remote-learning model because of the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing mandates.

2.2 Participants

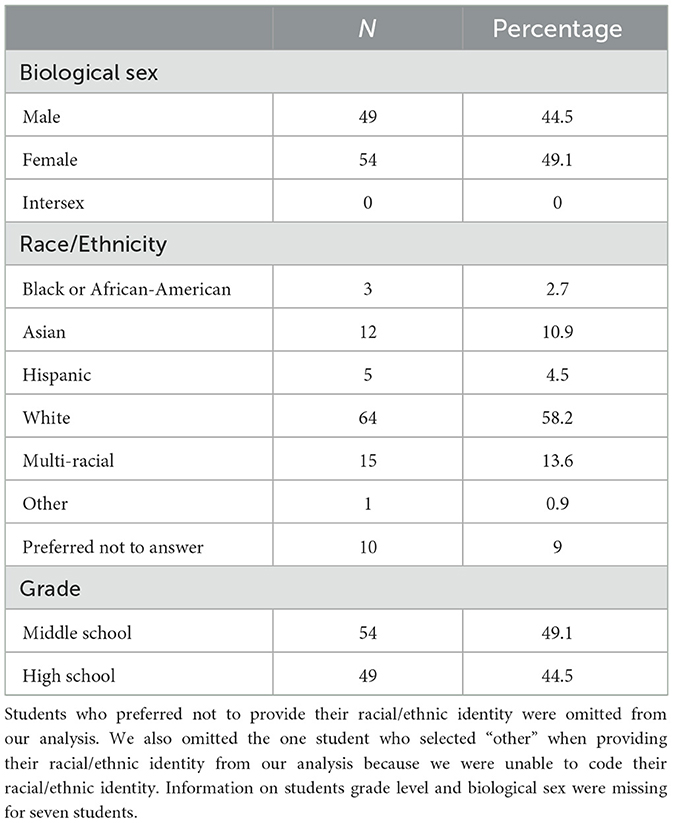

We recruited middle and high school students from a public K-12 charter school in the North Eastern United States. We sought out parental consent from all middle and high school students at the beginning of the year. All students who obtained parental consent were invited to participate in our survey. Of those invited, a total of 110 students assented to participate in our survey. Students received either a $5 Amazon Gift Card or $5 PayPal payment as compensation for each survey they completed across the year. Participant demographic information is reported in Table 1.

2.3 Measures

A list of all items used for each measure is provided in the Supplementary material.

2.3.1 Collective autonomy restriction

We adapted 6 items from Kachanoff et al. (2021) to measure student's experiences of racial/ethnic collective autonomy restriction (i.e., CAR). An example item includes the following: “In the U.S., people from other groups (e.g., racial/ethnic groups, political group, religious groups, etc.) have tried to control us.” Students indicated the extent to which they agreed with each statement on a scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree), with midpoint 4 (Neither Agree nor Disagree). Responses were averaged together, with higher scores indicating greater collective autonomy restriction (α = 0.95).

2.3.2 Intrinsic motivation support

We adapted 14 items from the learning climate questionnaire (Deci et al., 1996) to measure students' perceptions of intrinsic motivation support (i.e. IMS) from their teachers during the 2020–21 school year. An example item includes the following: “I felt that my teachers provided me with choices and options.” Students indicated the extent to which they agreed with each statement on a scale of 1(Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree), with midpoint 4 (Neither Agree nor Disagree). Responses were averaged together, with higher scores indicating greater perceptions of intrinsic motivation support from teachers (α = 0.95).

2.3.3 Fair treatment from teachers and adults at school

A subset of 7 items were adapted from Cohen's Climate Survey (Yeager et al., 2017) to measure students' past experiences with fair treatment (i.e., FT) from teachers and adults at school. An example item includes the following: “In the past, my teachers at school had a fair and valid opinion of me.” Students indicated the extent to which they agreed with each statement on a scale of 1(Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree), with midpoint 4 (Neither Agree nor Disagree). Responses were averaged together, with higher scores indicating more frequent experiences of fair treatment from teachers and adults at school in the past (T1: α = 0.88).

3 Results

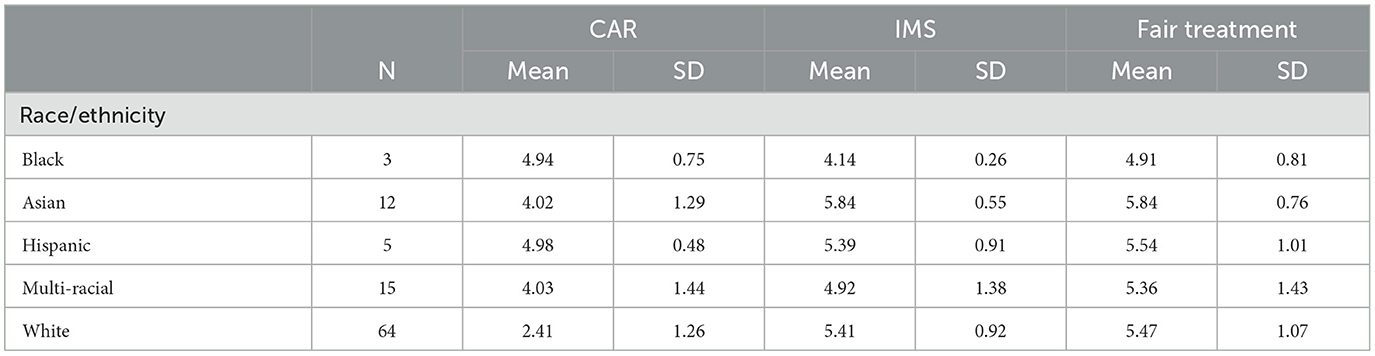

In the following analyses, student race was dummy coded (0 = White, 1 = student of color). The racial category student of color included students who self-reported as Black, Asian, Hispanic, and Multiracial. The decision to group these racial/ethnic identities into the single category “student of color” for our analysis was driven by the small sample size for each individual racial/ethnic category. We provide descriptive statistics for all dependent variables, separately for each racial/ethnic category, in Table 2. All analyses used listwise deletion to address missing data.

3.1 Student perceptions of collective autonomy restriction

Multiple Regression was used to test whether perceptions of collective autonomy restriction differed by students' racial/ethnic identity, while controlling for biological sex (dummy coded: 0 = Male, 1 = Female), grade, and mean neighborhood income (mean centered) [R2 = 0.38, F(4, 80) = 13.77, p < 0.001].2 In support of hypothesis 1, students of color were significantly more likely to experience racial/ethnic collective autonomy restriction compared to White students (bRace = 1.93, SE = 0.29, p < 0.001). Student's biological sex was associated with perceptions of collective autonomy restriction, such that females reported experiencing greater racial/ethnic collective autonomy restriction compared to male students(bSex = 0.66, SE = 0.27, p = 0.017). Mean neighborhood income and student grade were not associated with collective autonomy restriction (bIncome = −0.07, SE = 0.14, p = 0.625; bGrade = 0.04, SE = 0.07, p = 0.544).

3.2 Student perceptions of intrinsic motivational support

Multiple regression was used to test whether student's perceptions of collective autonomy restriction were associated with perceptions of intrinsic motivational support from teachers, while controlling for student race, biological sex, and grade [R2 = 0.07, F(2, 88) = 13.77, p = 0.053]. Consistent with hypothesis 2, greater perceptions of collective autonomy restriction were related to less perceptions of intrinsic motivational support from teachers (bCAR = −0.17, SE = 0.08, p = 0.030). Race, biological sex, and grade were not associated with students' perceptions of teacher support (bRace = 0.06, SE = 0.24, p = 0.785; bSex = 0.11, SE = 0.19, p = 0.810; bGrade = −0.01, SE = 0.05, p = 0.572).

3.3 Mediation analysis: perceptions of collective autonomy restriction mediate the link between student's racial/ethnic identity and teacher support

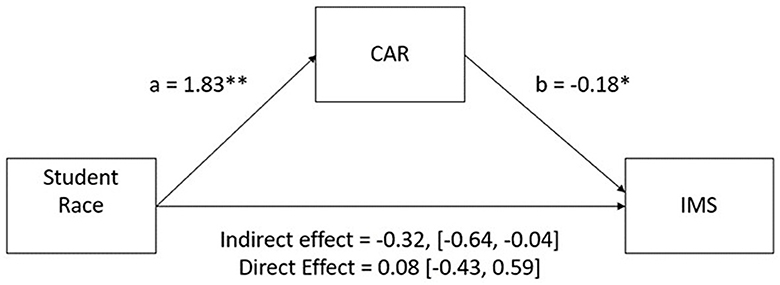

We ran a mediational model with the PROCESS Version 3.4 macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2017) to test whether collective autonomy restriction mediated the link between student race/ethnicity and perceived teacher support. Significant mediation was determined through the interpretation of the indirect effect (IE) using a bootstrap approach (5,000 iterations) to obtain 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Consistent with hypothesis 3, collective autonomy restriction mediated the association between student race/ethnicity and teacher support (IE = −0.32, 95% CI [−0.64, −0.03]; see Figure 1). Specifically, students of color were more likely to feel that their racial/ethnic collective autonomy was restricted (compared to White students), which in turn was associated with less perceived intrinsic motivational support from their teachers. Model coefficients for all pathways are reported in Figure 1.3

Figure 1. Collective autonomy restriction mediates the link between student race/ethnicity and perceived teacher support. N = 91. Student race was dummy coded (0 = White, 1 = Student of Color). CAR, collective autonomy restriction; IMS, Intrinsic Motivation Support from teachers. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

3.4 Moderation analysis: past exposure to fair treatment buffers the link between collective autonomy restriction and teacher support

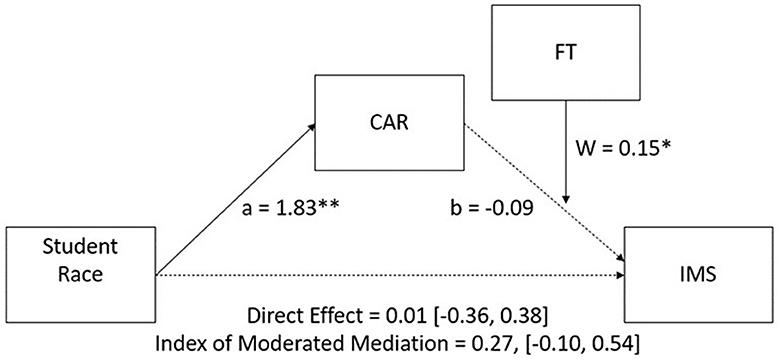

We examined whether previous experiences with fair treatment from teachers and adults at school would attenuate the link between collective autonomy restriction and teacher support (H3), in two steps. First, a regression analysis probed for a significant interaction between collective autonomy restriction (CAR) and fair treatment (FT) in predicting student's perceptions of teacher support. Second, moderation of the full mediational model by FT was tested through a moderated mediational model (see Figure 2). Significant moderated mediation was determined through the interpretation of the index of moderated mediation on the difference between the conditional effects (IE) at low (−1SD), average (Mean), and high (+1SD) levels of fair treatment using a bootstrap approach (5,000 iterations) to obtain 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Moderated mediation by students' past experience with fair treatment from teachers and adults at school. N = 91. Student Race was dummy coded (0 = White, 1 = Student of Color). CAR, collective autonomy restriction; IMS, Intrinsic motivation support from teachers. Dashed lines indicate non-significant pathways. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

Consistent with our hypothesis, the regression analysis yielded a significant CAR x FT interaction, suggesting that the association between collective autonomy restriction and perceptions of teacher support may depend on student's previous experiences with fair treatment from teachers and adults (bCAR×FT = −0.15, SE = 0.05, p = 0.004). We further probed the significant interaction by examining the conditional effects at low, average, and high levels of teacher care. Results from this follow up analysis indicated that greater collective autonomy restriction predicted less perceived teacher support, but only among students who reported experiencing low levels of fair treatment from teachers and adults at school in the past (−1SD: bFT = −0.26, SE = 0.08, p = 0.002). The association between collective autonomy restriction and teacher support was not significant among students who experienced average (Mean: bFT = −0.10, SE = 0.06, p = 0.095) or high (+1SD: bFT = 0.06, SE = 0.09, p = 0.432) levels of fair treatment from teachers and adults.

Despite significant moderation of the link between collective autonomy restriction and teacher support by previous experiences with fair treatment, the index of moderated mediation was not significant (index of moderated mediation = 0.27, SE = 0.18, CI [−0.11, 0.55]). In other words, previous experiences with fair treatment did not moderate the full mediational pathway where student race/ethnicity predicts perceived teacher support though collective autonomy restriction. Model coefficients for all pathways are reported in Figure 2.

4 Discussion

The present research integrates collective autonomy literatures with self-determination (Reeve et al., 2004; Kusurkar et al., 2013; Ryan and Deci, 2013) and identity-based motivational frameworks (Oyserman and Destin, 2010; Oyserman et al., 2011; Oyserman and Lewis, 2017) to advance our understanding of the socio-structural and psychological factors that shape the academic experiences of students of color. In support of our first hypothesis, racial/ethnic minority students were significantly more likely to feel collective autonomy restriction compared to their White peers. This finding is consistent with previous research suggesting that structural inequalities that disadvantage marginalized social groups can exacerbate feelings of collective autonomy restriction among marginalized group members (Kachanoff et al., 2019, 2021).

In support of our second hypothesis, we also showed that greater feelings of collective autonomy restriction among racial/ethnic minority students is associated with less perceived intrinsic motivation support from teachers in the classroom. When considering the role that structural inequality plays in shaping students' perceptions of collective autonomy restriction, this finding further emphasizes the need for researchers to consider the impact that shared societal experiences rooted in students' unique social identities can have on their experiences in the classroom. The current finding also echoes recent calls for education equity researchers to acknowledge the fundamental role that structural inequality plays in perpetuating racial/ethnic achievement gaps in education (Merolla and Jackson, 2019).

Consistent with identity-based frameworks of academic motivation, these findings also suggest that students' perceptions of their racial/ethnic group's collective autonomy within the broader socio-structural context of the U.S. influences their perceptions of teacher support. However, where past research on identity-based motivation emphasizes the impact of socio-structural factors on racial/ethnic minority students' perceptions of themselves within academic contexts, our study suggests that they also shape perceptions of others (e.g., teachers) as supportive of their intrinsic motivational needs. This caries important implications for education equity research, as it highlights the need for researchers and educators to consider the influence that broader structural inequity has, not only on individual motivation, but also on the important relationships between students and educators that help shape academic motivation (Graham et al., 2022; Gray et al., 2022 for related arguments; see Robinson, 2022).

Finally, the present study also examined whether fair treatment from teachers could help buffer the negative association between collective autonomy restriction and perceived teacher support. In partial support of hypothesis 3, students' previous experiences with fair treatment were found to moderate the link between collective autonomy restriction and perceptions of teacher support. Specifically, the negative association between collective autonomy restriction and teacher support was only significant among students who reported experiencing low levels of fair treatment at school in the past. Importantly, there was no significant link between collective autonomy restriction and perceived teacher support among students who reported average to high levels of fair treatment from teachers in the past. One interpretation of these results is that past experiences with teachers and adults who treat students and their peers in a fair and just manner provide students with a positive exemplar of teacher-pupil relationships at school. These positive exemplars, in turn, may “inoculate” student's future perceptions of teachers from harmful cues that may cause them to anticipate that they will not be supported in academic settings (see the Stereotype Inoculation Model for related arguments about self-perceptions in academia: Dasgupta, 2011).

4.1 Limitations and future directions

There are several limitations to consider in the present research. First, challenges around the data collection process resulted in the relatively small sample size reported in this study. Mainly, data collection occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. During this time, our partner school, like most schools across the U.S., had adopted a remote learning model to help reduce the spread of COVID-19 and keep their students and faculty safe. This created barriers for both obtaining parental consent, and collecting student data, as communication between the research team, parents, students, and relevant school faculty was conducted entirely online. The challenges families endured during the pandemic created additional barriers to recruitment.

Because of our small sample size, we made the decision to group Black, Asian, Hispanic, and Multiracial students into a single category (i.e., students of color) to conserve power and test for differences in perceived collective autonomy and teacher support between racial/ethnic minority students and their White peers. We recognize that the racial/ethnic gaps in academic support and performance discussed in our introduction have primarily been documented among Black, Indigenous, and Latinx students. This likely accounts for why we did not observe direct effects of student race/ethnicity on perceived teacher support in our analyses. However, descriptive statistics suggest that Asian and Multiracial students experience collective autonomy restriction at rates similar to those of Black and Latinx students. There are several reasons as to why Asian and Multiracial students would feel that their racial/ethnic collective autonomy is restricted in the U.S., including increased reports of anti-Asian prejudice during to the COVID-19 pandemic (Nguyen et al., 2020; Ruiz et al., 2021), as well as research indicating that Multiracial individuals experience several forms of racial discrimination from both majority and minority group members (Shih and Sanchez, 2005; Franco et al., 2021). However, due to our limited sample size, we were unable to see whether the strength of the link between collective autonomy restriction and perceived teacher support was similar across individual racial/ethnic minority groups. Future research with a more robust sample size should further examine this question.

4.2 Practical implications for educators

The present research provides three important implications for educators to consider. First, our findings indicate that adolescents of color are sensitive to socio-structural inequalities that restrict their racial/ethnic group's freedom to practice and define their collective culture and social identity within the U.S. Second, awareness of such restrictions carries over to the classroom and makes students of color attuned to cues that communicate a lack of support from their teachers. Finally, results from our study emphasize the importance of quality relationships between students, their teachers, and other adults at school in buffering the negative impact that collective autonomy restriction can have on feelings of support, especially among students of color. One way that teachers can help foster quality relationships with their students is by engaging in fair classroom practices. Future research should further examine specific practices that teachers can adopt to support the intrinsic motivational development of students of color.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Massachusetts Amherst Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

AR-R and EM contributed to conception and design of the study. AR-R performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from EM. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

This research would not have been possible without the support and involvement of our community research partners. We thank them for their contributions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1242863/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The present study uses the term “students of color” to refer to Black, Asian, Hispanic and Multiracial students who participated in the present study. We distinguish this term from the previous term “racial/ethnic minority students” to acknowledge that the research highlighted in our introduction mainly documents racial/ethnic disparities among Black, Indigenous, and Latinx students.

2. ^Mean neighborhood income was derived from 2020 census data, and primary residential zip codes provided by each student. Note that 16 students did not provide their zip code.

3. ^Because of the cross-sectional nature of our data, perceived collective autonomy restriction and teacher support were measured at the same time (Fall Semester of the 2020–21 school year), raising questions of the directionality of effects. To address this issue, we ran an additional mediational model where teacher support was treated as the mediator, and collective autonomy restriction was treated as the outcome. The indirect effect of this model was not significant, further supporting our hypothesis which emphasizes collective autonomy restriction as the mediator between student race/ethnicity, and perceived teacher support. Pathway coefficients for this model can be found in the supplemental information.

References

Agnew, R., Brezina, T., Wright, J. P., and Cullen, F. T. (2002). Strain, personality traits, and delinquency: extending general strain theory. Criminology 40, 43–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2002.tb00949.x

Allen, K. A., Slaten, C. D., Arslan, G., Roffey, S., Craig, H., Vella-Brodrick, D. A., et al. (2021). School Belonging: The Importance of Student and Teacher Relationships. The Palgrave Handbook of Positive Education. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 525–550.

Benner, A. D., and Graham, S. (2013). The antecedents and consequences of racial/ethnic discrimination during adolescence: does the source of discrimination matter? Dev. Psychol. 49, 1602–1613. doi: 10.1037/a0030557

Bottiani, J. H., Bradshaw, C. P., and Mendelson, T. (2016). Inequality in Black and White high school students' perceptions of school support: an examination of race in context. J. Youth Adoles. 45, 1176–1191. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0411-0

Byrd, C. M., and Chavous, T. (2011). Racial identity, school racial climate, and school intrinsic motivation among African American youth: the importance of person–context congruence. J. Res. Adoles. 21, 849–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00743.x

Cabrera, A. F., Nora, A., Terenzini, P. T., Pascarella, E., and Hagedorn, L. S. (1999). Campus racial climate and the adjustment of students to college: A comparison between White students and African-American students. The J. Higher Educ. 70, 134–160. doi: 10.1080/00221546.1999.11780759

Chirkov, V. I. (2009). A cross-cultural analysis of autonomy in education: a self-determination theory perspective. Theor. Res. Educ. 7, 253–262. doi: 10.1177/1477878509104330

Chory, R. M. (2007). Enhancing student perceptions of fairness: the relationship between instructor credibility and classroom justice. Commun. Educ. 56, 89–105. doi: 10.1080/03634520600994300

Clayson, D. E., and Haley, D. A. (1990). Student evaluations in marketing: What is actually being measured?. J. Marketing Educ. 12, 9–17. doi: 10.1177/027347539001200302

Coleman, J. S. (1974). Youth: transition to adulthood. NASSP Bullet. 58, 4–11. doi: 10.1177/019263657405838502

Collingwood, L., Lajevardi, N., and Oskooii, K. A. (2018). A change of heart? Why individual-level public opinion shifted against Trump's “Muslim Ban”. Polit. Behav. 40, 1035–1072. doi: 10.1007/s11109-017-9439-z

Comas-Díaz, L., and Greene, B. (1994). “Women of color with professional status,” in Women of Color: Integrating Ethnic and Gender Identities in Psychotherapy, 347–388.

Crystal, D. S., Killen, M., and Ruck, M. D. (2010). Fair treatment by authorities is related to children's and adolescents' evaluations of interracial exclusion. Appl. Dev.Sci. 14, 125–136. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2010.493067h

Dasgupta, N. (2011). Ingroup experts and peers as social vaccines who inoculate the self-concept: the stereotype inoculation model. Psychol. Inq. 22, 231–246. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2011.607313

Davis, J. (2001). American Indian boarding school experiences: recent studies from Native perspectives. OAH Mag. History 15, 20–22. doi: 10.1093/maghis/15.2.20

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., and Williams, G. C. (1996). Need satisfaction and the self-regulation of learning. Learn. Individu. Differ. 8, 165–183. doi: 10.1016/S1041-6080(96)90013-8

Feldman, K. A. (1989). The association between student ratings of specific instructional dimensions and student achievement: refining and extending the synthesis of data from multisection validity studies. Res. Higher Educ. 12, 583–645. doi: 10.1007/BF00992392

Fellner, J. (2009). Race, drugs, and law enforcement in the United States. Stan. L. Pol'y Rev. 20, 257.

Franco, M., Durkee, M., and McElroy-Heltzel, S. (2021). Discrimination comes in layers: Dimensions of discrimination and mental health for multiracial people. Cult. Div. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 27, 343. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000441

Glock, S., and Kovacs, C. (2013). Educational psychology: using insights from implicit attitude measures. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 25, 503–522. doi: 10.1007/s10648-013-9241-3

Graham, S., Kogachi, K., and Morales-Chicas, J. (2022). Do i fit in: race/ethnicity and feelings of belonging in school. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 34, 2015–2042. doi: 10.1007/s10648-022-09709-x

Gray, D. L., Ali, J. N., McElveen, T. L., et al. (2022). The cultural significance of “we-ness”: motivationally influential practices rooted in a scholarly agenda on black education. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 34, 1985–2013. doi: 10.1007/s10648-022-09708-y

Gregory, A., and Ripski, M. B. (2008). Adolescent trust in teachers: implications for behavior in the high school classroom. School Psychol. Rev. 37, 337–353. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2008.12087881

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford publications.

Houston, M. B., and Bettencourt, L. A. (1999). But that's not fair! An exploratory study of student perceptions of instructor fairness. J. Market. Educ. 21, 84–96. doi: 10.1177/0273475399212002

Hughes, J. N. (2011). Longitudinal effects of teacher and student perceptions of teacher-student relationship qualities on academic adjustment. The Element. School J. 112, 38–60. doi: 10.1086/660686

Huynh, V. W., and Fuligni, A. J. (2010). Discrimination hurts: the academic psychological, and physical well-being of adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 20, 916–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00670.x

Inan-Kaya, G., and Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2022). Teacher classroom interactions and behaviours: Indications of bias. Learn. Instr. 78, 101516. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2021.101516

Jang, H., Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., and Kim, A. (2009). Can self-determination theory explain what underlies the productive, satisfying learning experiences of collectivistically oriented Korean students?. J. Educ. Psychol. 101, 644. doi: 10.1037/a0014241

Kachanoff, F. J. (2017). Collective Autonomy: Implications for Individual Group Members and Intergroup Relations. Montreal, QC: McGill University.

Kachanoff, F. J., Cooligan, F., Caouette, J., and Wohl, M. J. (2021). Free to fly the rainbow flag: the relation between collective autonomy and psychological well-being amongst LGBTQ+ individuals. Self Identity 20, 741–773. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2020.1768890

Kachanoff, F. J., Taylor, D. M., Caouette, J., Khullar, T. H., and Wohl, M. J. (2019). The chains on all my people are the chains on me: restrictions to collective autonomy undermine the personal autonomy and psychological well-being of group members. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 116, 141. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000177

Kaufman, E. M., and Killen, M. (2022). Children's perspectives on fairness and inclusivity in the classroom. The Spanish J. Psychol. 25, e28. doi: 10.1017/SJP.2022.24

Kusurkar, R. A., Ten Cate, T. J., Vos, C. M. P., Westers, P., and Croiset, G. (2013). How motivation affects academic performance: a structural equation modelling analysis. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 18, 57–69. doi: 10.1007/s10459-012-9354-3

Little, B. (2017). How Boarding Schools Tried to ‘Kill the Indian' Through Assimilation. New York, NY: History.com.

Louie, P., and Upenieks, L. (2022). Vicarious discrimination, psychosocial resources, and mental health among black Americans. Soc. Psychol. Q. 85, 187–209. doi: 10.1177/01902725221079279

Lowman, J., and Lowman, J. (1984). Mastering the Techniques of Teaching, 1st Edn. Hoboken, SJ: Jossey-Bass.

Maggio, C. (2021). State-level immigration legislation and social life: the impact of the “show me your papers” laws. Soc. Sci. Q. 102, 1654–1685. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.13018

McGahey, R. (2021). Zoning, Housing Regulation, and America's Racial Inequality. Forbes. Available online at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/richardmcgahey/2021/06/30/zoning-housing-regulation-and-americas-racial-inequality/ (accessed May 16, 2023).

Merolla, D. M., and Jackson, O. (2019). Structural racism as the fundamental cause of the academic achievement gap. Sociol. Compass 13, e12696. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12696

Mitchell, C. (2017). Some States With “English-Only” Laws Won't Offer Tests in Other Languages. Education Week. Available online at: https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/some-states-with-english-only-laws-wont-offer-tests-in-other-languages/2017/10 (accessed October 25, 2017).

Nguyen, T. T., Criss, S., Dwivedi, P., Huang, D., Keralis, J., Hsu, E., et al. (2020). Exploring US shifts in anti-Asian sentiment with the emergence of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 17, 7032. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197032

Okonofua, J. A., Walton, G. M., and Eberhardt, J. L. (2016). A vicious cycle: a social–psychological account of extreme racial disparities in school discipline. Persp. Psychol. Sci. 11, 381–398. doi: 10.1177/1745691616635592

Oyserman, D., and Destin, M. (2010). Identity-based motivation: implications for intervention. The Counsel. Psychol. 38, 1001–1043. doi: 10.1177/0011000010374775

Oyserman, D., Johnson, E., and James, L. (2011). Seeing the destination but not the path: Effects of socioeconomic disadvantage on school-focused possible self content and linked behavioral strategies. Self Identity 10, 474–492. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2010.487651

Oyserman, D., and Lewis Jr, N. A. (2017). Seeing the destination AND the path: using identity-based motivation to understand and reduce racial disparities in academic achievement. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 11, 159–194. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12030

Padilla, A. M., Lindholm, K. J., Chen, A., Durán, R., Hakuta, K., Lambert, W., et al. (1991). The English-only movement: myths, reality, and implications for psychology. Am. Psychol. 46, 120. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.46.2.120

Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., and Barch, J. (2004). Enhancing students' engagement by increasing teachers' autonomy support. Motiv. Emotion 28, 147–169. doi: 10.1023/B:MOEM.0000032312.95499.6f

Rivera-Rodriguez, A. (2021). Teacher's Discipline Practices and Race: The Effect of “Fair” and “Unfair” Discipline on Black and White Student's Perceptions and Behaviors. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts.

Robinson, C. D. A. (2022). Framework for motivating teacher-student relationships. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 34, 2061–2094. doi: 10.1007/s10648-022-09706-0

Rodabaugh, R. C., and Kravitz, D. A. (1994). Effects of procedural fairness on student judgments of professors. J. Excellence College Teach. 5, 67–83.

Ruiz, N. G., Edwards, K., and Lopez, M. H. (2021). One-Third of Asian Americans Fear Threats, Physical Attacks and Most Say Violence Against Them is Rising. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/04/21/one-third-of-asian-americans-fear-threats-physical-attacks-and-most-say-violence-against-them-is-rising/ (accessed April 21, 2021).

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2013). Toward a social psychology of assimilation: self-determination theory in cognitive. Self-Reg. Auton. Soc. Dev. Dimens. Hum. Conduct 40, 191. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139152198.014

Shertzer, A., Twinam, T., and Walsh, R. P. (2022). Zoning and segregation in urban economic history. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 94, 103652. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2021.103652

Shih, M., and Sanchez, D. T. (2005). Perspectives and research on the positive and negative implications of having multiple racial identities. Psychol. Bullet. 131, 569–591. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.569

Smith, L. V., Wang, M. T., and Hill, D. J. (2020). Black youths' perceptions of school cultural pluralism, school climate and the mediating role of racial identity. J. School Psychol. 83, 50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2020.09.002

Steinberg, L., and Silverberg, S. B. (1986). The vicissitudes of autonomy in early adolescence. Child Dev. 12, 841–851. doi: 10.2307/1130361

Tamura, E. H. (2002). African American vernacular English and Hawai'i Creole English: a comparison of two school board controversies. J. Negro Educ. 28, 17–30. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3211222

Tarrant, M., North, A. C., Edridge, M. D., Kirk, L. E., Smith, E. A., Turner, R. E., et al. (2001). Social identity in adolescence. J. Adolesc. 24, 597–609. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0392

Tenenbaum, H. R., and Ruck, M. D. (2007). Are teachers' expectations different for racial minority than for European American students? A meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 253. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.253

Walsh, D. J., and Maffei, M. J. (1994). Never in a class by themselves: an examination of behaviors affecting the student-professor relationship. J. Exc. College Teach. 5, 23–49.

Williams, D. R., and Mohammed, S. A. (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J. Behav. Med. 32, 20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0

Keywords: identity, race, collective autonomy, intrinsic motivation, teacher support

Citation: Rivera-Rodriguez A and Mercado E (2024) Racial/ethnic collective autonomy restriction and teacher fairness: predictors and moderators of student's perceptions of teacher support. Front. Educ. 9:1242863. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1242863

Received: 19 June 2023; Accepted: 05 February 2024;

Published: 21 February 2024.

Edited by:

Mohamed A. Ali, Grand Canyon University, United StatesReviewed by:

Sara Costa, Roma Tre University, ItalyGeraldine Keawe, Independent Researcher, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Copyright © 2024 Rivera-Rodriguez and Mercado. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adrian Rivera-Rodriguez, YXJpdmVyYXJvZHJpJiN4MDAwNDA7dW1hc3MuZWR1

Adrian Rivera-Rodriguez

Adrian Rivera-Rodriguez Evelyn Mercado

Evelyn Mercado