- Director of Institutional Effectiveness and Accreditation, Sharjah Maritime Academy, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Introduction: Career advancement must be based on merit, according to the universal norm. However, faculty members continue to express their dissatisfaction with the existing promotion policies and practices, highlighting issues like ambiguity, lack of transparency, inconsistent implementation, and the overall fairness of the evaluation process. This study aimed to explore the intersections of promotion policies with the research habitus and the distribution of different forms of capital in two higher education institutes in the United Arab Emirates.

Methods: Data were gathered from a purposively selected sample of faculty members using semi-structured interviews in addition to key policy documents at both institutes.

Results and discussion: Using Bourdieu’s notion of habitus, capital, and field, the study identified key characteristics of the research habitus and how it shapes perceptions towards aspects of competitiveness and collegiality as practiced in the research world. The study also examined potential relationships between research habitus and promotion policies. Finally, the study explored capital distribution in the research field and identified some of the undisclosed aspects of the promotion world, highlighting areas like prior education, affiliations, professional experience, cultural background, ethnicity, and social networks as some of the factors that may play a role in the promotion outcomes. The findings of the study can be used to offer an additional layer of understanding some hidden rules of academic research fields and capital distribution in light of institutional policy development and enactment. Such understanding can be used to make recommendations on how existing challenges can be addressed to improve perceptions of the clarity and fairness of faculty promotion policies and encourage more transparent practices.

1 Introduction

It is universally accepted that promotion is one of the main indicators of a faculty member’s progression in the academic world. According to Young (2006), it is arguably the most important incentive used by higher education institutes to encourage their faculty. Moreover, Hanley and Forkenbrock (2006) claimed that the university’s stringent promotion and reward system has been the main driver for faculty excellence. Therefore, the employment and advancement of exceptional professors are essential to an academic institution’s overall success (Albatch, 2008). From an academic or faculty member’s point of view, getting a promotion to a professorship is a remarkable achievement that elevates his or her status in the academic field (Azman et al., 2016). Barrow and Grant (2018) identify promotion as a compelling moment of academic subject formation where, in order to participate, individuals must account for themselves as promotion-worthy through presenting a comprehensive dossier in response to a detailed set of norms.

In the past few decades, education systems around the globe have adapted to political, governmental, and market factors. One of the key results of these changes is that faculty performance is being increasingly evaluated based on quantitative results (Heffernan, 2017). As a result, universities and colleges responded to the requirements of neoliberalism by establishing a competitive atmosphere that included responsibility toward their sponsors and regulators (Ward, 2012). This has resulted in a system for faculty hiring, grading, and advancement that resembles a tournament (Musselin, 2005). By comparing faculty members’ outputs, this tournament-like system of marking allegedly aims at boosting productivity, encouraging competition, and refining selectivity.

Evaluating faculty is crucial to promoting faculty development but changes to the evaluation criteria may have jeopardized this aim. Market liberalism emphasized faculty productivity and efficiency (Soudien et al., 2013), fostering a “performativity” culture. Soudien et al. (2013) define “performativity” as a formalized system to monitor and assess faculty effectiveness. Neoliberalism’s market-based principles affected economic, social, and cultural realms, and the need for economic efficiency changed higher education managerial ideologies and practices (Saunders, 2010). The identities and goals of teachers and students have changed as higher education has adapted to neoliberal practices and ideology (Saunders, 2010). Measurable outputs have replaced open intellectual study and discussion in professional society (Olssen and Peters, 2005). Neoliberal principles and market logic have indirectly impacted faculty promotion, citing a decline in academic reasoning and academic values due to market competition (Levin et al., 2020).

Given the dynamic changes in academia, such as the rise of open-access journals, preprint servers, and the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, various parties, including academics, are now examining the effectiveness of conventional methods used for faculty promotion (Schimanski and Alperin, 2018). According to Faria et al. (2013), academic promotion has always been a highly debated subject, with discussions typically focusing on efficacy, excellence, fairness, and quality. Sutherland (2017) highlights that research output is the primary criterion for evaluating academics for distinguished faculty appointments, promotions, honors, and rewards. Most of the institutions are still utilizing simple, easily quantifiable metrics such as the journal impact factor (JIF) or the number of publications as an indicator for research output (McKiernan et al. (2019). Inconsistent evaluation of research-related standards, giving more weight to research than to instruction, and quantity versus quality issues have been a few of the most common difficulties associated with promotion policies.

Another significant obstacle is the widespread belief that the promotion procedure in general, and research outcome evaluation in particular, cannot be democratic or transparent (Omar et al., 2015). For instance, the Pharmacy Faculty Demographics and Salaries report published by the American Association of Colleges and of Pharmacy (2023) cites that women are disproportionately present in lower-ranking roles such as instructor and assistant professor, whereas they are underrepresented in higher-ranking jobs like senior and administrative roles. Most universities have official regulations and procedures for their promotion processes. However, there is frequently considerable subjectivity in terms of how these guidelines are interpreted and enacted. Promotions are always open to subjectivity and bias, and there are often no normative rules for an institution’s decision-making powers (Omar et al., 2015). Consequently, the way each department or unit within an institutional practice applies its promotion strategy may differ significantly.

In light of these complexities, many faculty members may feel compelled to assert their merit or aggressively refute negative stereotypes (Durodoye et al., 2019). For instance, Kulp et al. (2021) highlight that a large body or research points out that mid-career faculty members deal with a variety of demands and stressors that impact both their likelihood of being promoted to full professor and their level of job satisfaction. One of these pressing demands faced by faculty is to continuously seek to achieve an appropriate balance between their teaching, research, and community service duties to align with their professional goals and to meet institutional needs and curricular requirements. The distribution of these efforts is largely impacted by the institutional culture, which also has a large influence on faculty recruitment and retention as well as promotion and tenure (Blakely et al., 2023). Thus, an efficient and fair system for appointing and promoting faculty members is essential for enhancing the overall well-being of scholars and fostering a thriving academic environment at any educational institution.

Based on his research, Pierre Bourdieu proposed a social theory that classified people into “fields,” “capital,” and “habitus.” In any society, there are numerous fields, each with its own set of norms and expectations (Bourdieu, 1989). Bourdieu regularly used metaphors to explain his ideas, and the term ‘field’ is derived from the tournament field. In football, different experiences, opportunities, and skills have brought each player to the field, and everyone’s past has shaped who they are today as competing footballers (Bourdieu, 1990). Referring to the tournament-like model described earlier where faculty members compete to achieve promotion, Bourdieu’s concept of field seems particularly appropriate in the context of this study. Academics acquire the norms of the field as they progress through their careers as students, mentees, and full-fledged faculty members.

An individual’s capital can be broken down into subcategories, including economic, cultural, and social capital. A person’s economic wealth is the amount of money at their disposal. This may be related to one’s job or one’s family’s wealth (Bourdieu, 1995). On the other hand, language, educational attainment, and involvement in peer cultures are all examples of one’s cultural capital. Access to culture may be influenced by an individual’s economic capital and vice versa. Social capital is the sum of an individual’s social networks. It can refer to being able to use these networks to advance one’s career, but simply belonging to a network is also advantageous. The ability of someone’s capital to reveal information about their past and, in turn, predict their future is a key feature of all types of capital. As a result, there are obvious connections between all kinds of capital and the “structured” and “structuring” events that give rise to their habitus. Second, capital, according to Bourdieu, draws more capital. For instance, if a child’s family’s financial capital is transformed into cultural capital as a result of the child attending outstanding schools, that cultural capital may then be transformed back into financial capital as the child embarks on a financially rewarding career at a later stage of his/her life (Grenfell and James, 1998).

How do people in such a restricted social framework as academia be true to who they are? Bourdieu used the term “habitus” to describe this sense of physical and psychological identity that each of us has in the spaces we occupy. By “habitus,” Bourdieu (1994) means the sum of the experiences, interactions, and impressions that have formed one’s personality, outlook, and values throughout their lifetime. Therefore, habitus forms the properties that combine to form the structured and structuring structure of an individual. Habitus also affects how people interact with the outside world, causing them to adopt particular attitudes, values, and behaviors. As Bourdieu said, it is because of his own habitus that ‘I either see or do not see certain things in a given situation. And depending on whether I see these things or not, I shall be incited by my habitus to do or not do certain things’ (Schaffer, 2016).

Therefore, our habitus cover everything we do, whether or not we are consciously aware of them at the time. Since we are continually evaluating ourselves to others, we are also able to spot habitus in those around us. Education, family upbringing, and social connections all play a role in shaping the professional messages we absorb and convey (Bourdieu, 1995). According to Bourdieu, our connections to others, both below and above us, are as important to our achievement as the work we put in on our own (Bourdieu, 1998). A stable and consistent academic hierarchy is maintained by the interplay between habitus, capital, and field norms (Bourdieu, 1998). Power is not usurped before it has been earned through the traditional rites of passage of faculty promotion, which is why “knowing one’s position” is crucial. This entails working tirelessly at teaching, researching, and writing in order to position oneself as a deserving applicant for inclusion in the academically elite society.

Bourdieu insists that a habitus is first and foremost a conceptual tool for use in an empirical study rather than a concept to be debated in texts (Reay, 2004). Habitus offers a strategy for investigating ‘the experience of social agents and the objective structures which make this experience feasible’ all at once (Bourdieu, 1988). Incorporating habitus as a theoretical framework suggests that studies will consider factors beyond those being studied directly. Bourdieu’s approach stresses how “the structure of those worlds is already predefined by broader racial, gender, and class relations,” highlighting the importance of seeing people as actively engaged in creating their social worlds (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992). Although Bourdieu’s theories of habitus, capital, and field can be explained independently of universities or any educational establishment, it is important to note that he was a university professor who interacted with his colleagues and students. Bourdieu’s main work, Homo Academicus, is an application of his theories to the context of higher education (Heffernan, 2021).

Of relevance to this study, Bourdieu’s key concepts and multi-method approach continue to function as a theoretical toolbox for present studies addressing the complexities of career trajectories in higher education. For example, Gander (2022) used Bourdieu’s theory as an integrative framework for career theory, where career stories from university professional staff were analyzed using the lens of The Holistic Career Framework. Smith and Walker (2021) utilized Bourdieu’s analytical framework in an exploratory study that analyzed the role descriptors and promotion criteria of mid-sized United Kingdom universities, citing significant disparities in the job titles within education-oriented career paths, the definitions of scholarship, the anticipated impact, and the connection between scholarship and pedagogic research. Stavrou (2022) investigated the intersection of a knowledge structure with a graduate’s social class by using Bourdieu’s theory to demonstrate how, in each field of study, specific forms of social inequality operate, affecting transitions from higher education to work in increasingly competitive and precarious labor markets. Last but not least, Fudiyartanto and Stahl (2023) explored the role of symbolic capital associated with the training received at the graduate level in informing how academics navigate their careers and how they advance professionally in the context of the Indonesian higher education.

Moreover, Bourdieu’s notions of habitus, capital and filed have been used in higher education research to address areas like inequality and social justice (Birtwell et al., 2020; Bülbül, 2020; Jayakumar and Page, 2021; Reay, 2021; Hassan, 2022; Kovács and Pusztai, 2023), pedagogy and curriculum reform (Annala et al., 2020; Hindhede and Højbjerg, 2020), and learner pathways and mobility (Katartzi and Hayward, 2019).

Based on the above, I decided to investigate the intersection of faculty promotion policies and research conceptions, perceptions, and norms using semi-structured interviews with a purposively selected sample of faculty members from two higher education institutes in the United Arab Emirates. In addition, the study utilized content analysis to offer a careful examination of key policy documents at both institutes. In particular, the theoretical lens of Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of practice was used to answer the following research questions:

• What are the key characteristics of the research habitus at the two institutes as perceived by the participants in this study?

• To what extent does the research habitus at each institute reflect the promotion policy implemented?

• How are economic, social, and cultural capital distributed in different fields of faculty promotion represented by the two institutes? And what are the implications of such distributions for promotion policies and practice?

The study aimed to offer conceptual significance in terms of offering an additional layer of understanding of how different academic research fields can have different rules considering institutional policy development and enactment. Bourdieu’s views adopt a fatalist approach where life is almost predictable, and the future is pre-determined upon birth. In essence, this seems to challenge the core aspect of promotion policies, where the future (e.g., potential promotion) is determined by merit and hard work (e.g., research excellence). Therefore, Bourdieusian analysis seemed like an interesting choice, in my view, to investigate promotion policies and practices.

The study also shed light on some of the hidden forms and perceived values of different capital and how they come to play in the power dynamics associated with faculty promotion. Additionally, the study can hold applied significance by identifying some of the sources of tension between decision-makers and faculty members and how existing challenges can be addressed to improve perceptions of the clarity and fairness of faculty promotion policies and promote more transparent practices.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Research position

A researcher’s epistemological and ontological assumptions must be firmly established as they are underpinned by implicit assumptions that highlight the various ways in which people perceive and construct the world (Silverman, 2013).

The theoretical foundation of Bourdieu’s work is built around a critical social structure that sees society as a field of conflict and dominance molded by symbolic power dynamics. Therefore, this study adopts a critical realist ontology that acknowledges the existence of objective social structures and processes that function independently of individual consciousness while remaining open to interpretation and challenge. While recognizing that social structures like habitus and capital are always subject to interpretation and challenge, critical realism enables us to recognize their objective existence. This indicates that while objective social structures influence people’s actions and views, people also have the power to question and alter these structures.

The study adopts a constructivist stance from an epistemological standpoint, acknowledging that knowledge is created through interactions between people and their environments. When comparing subjectivism and objectivism, constructivism can be seen as a compromise. It recognizes that knowledge is constructed in part based on the individual’s subjective experiences and interpretations of the world (such as their perceptions and reflections on past promotional experiences) and in part based on the objective features of the environment (such as their access to economic and cultural resources). By implication, this view holds that reality is not static but rather open to discussion and change.

2.2 Context

This study was conducted on two higher education institutes in the United Arab Emirates with different academic scopes and contexts. The first institute (herein referred to as Institute X) is a purely academic, research-intense university offering programs to almost 13,000 students at the Bachelor, Master, and Ph.D. levels through nine Colleges. The university has more than 600 faculty members holding the titles of Professor, Associate Professor, and Assistant Professor. The second institute (herein referred to as Institute Y), on the other hand, is considered one of the largest applied higher education institutes in the region offering mostly diploma and bachelor programs in six disciplines to more than 23,000 students across the country. The institute currently has more than 1,200 faculty members.

Institute X has seven strategic objectives covering areas like developing successful future-ready learners, contributing actively to the goals of sustainable development, and fostering national and international partnerships that contribute to the promotion of the university’s reputation and its global standing. Of particular interest to this study is the second strategic goal: Impactful Research and Innovation. Through this goal, Institute X strives to ‘use the University’s research and innovation capabilities to find novel and sustainable solutions to future challenges and enhancing the global competitiveness of the University.’ The university prioritizes seven key area of strategic importance, namely renewable energy, transportation, education, health, technology, water resources and space exploration. As per their website, the university currently has 9 research centers, 2 virtual research institutes, 1 science and innovation park, 590 ongoing research projects, 550 international research grants, and 471 labs.

As per Institute Y, its strategic plan highlights 5 objectives addressing empowering students, offering quality programs, providing quality services, among others. Although no objective directly spells out research, the fifth objective pertains to embedding an innovation culture in the institutional environment. Operationally, this objective is primarily assumed through the Center for Excellence and Research and Training. The center’s homepage identifies applied research as ‘a catalyst to technology-based innovation by converting technology into business incubating opportunities and graduating sustainable companies.’ Institute Y has 3 large innovation and entrepreneurial incubators, which are dynamic environments equipped virtual reality devices, high bandwidth interconnectivity, and fitted with industry scale and high caliber equipment such as the Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machines and virtual reality devices. They cover distinctive areas including design and media, programming and computing, intelligence augmentation, fabrication, business and entrepreneurship, and future industry to support student startups.

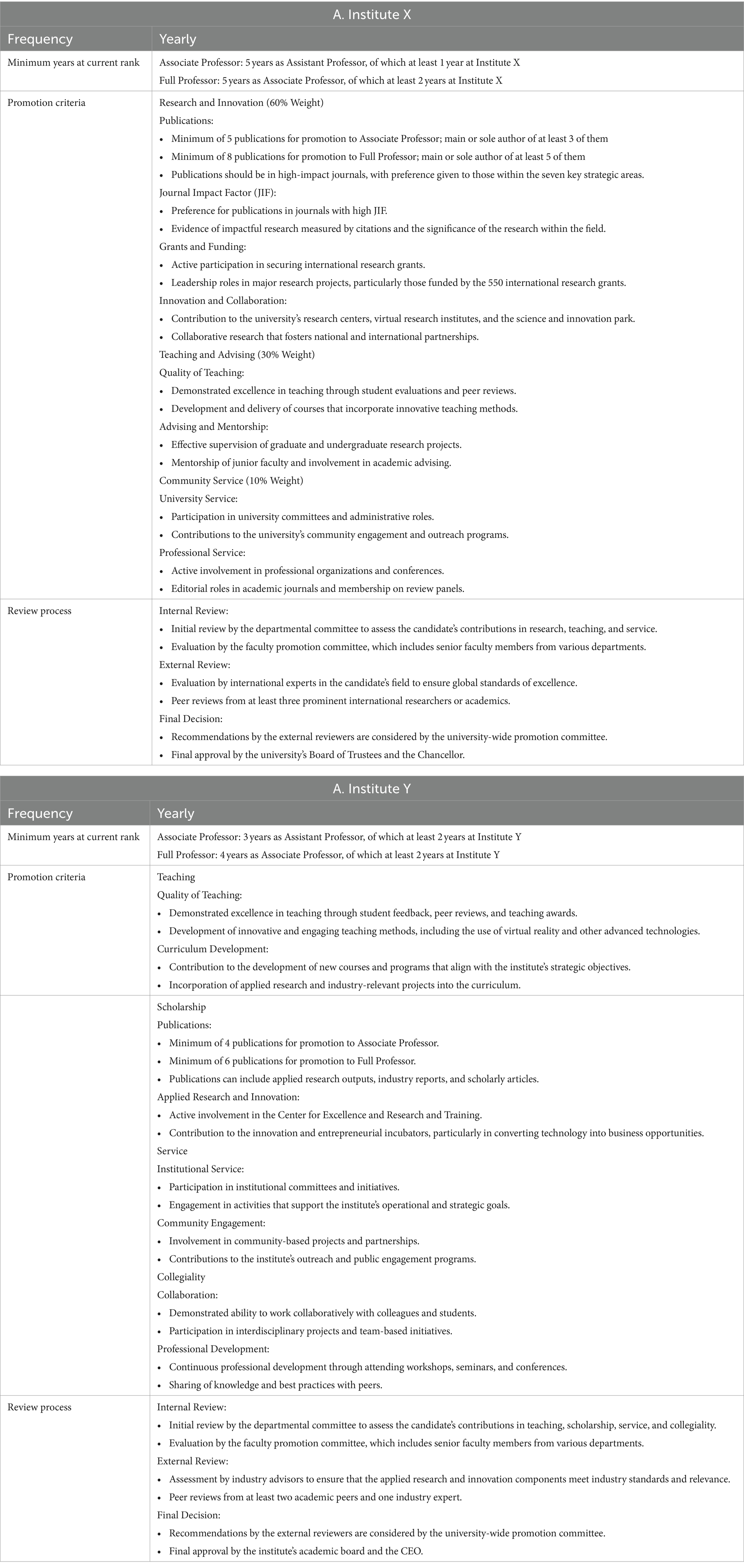

In terms of the promotion policies, Institute X identifies academic research, teaching and advising, and community service as the promotion as the promotion criteria, with 60% weight allocated to research. Institute Y, on the other hand, lists teaching, scholarship, service, and collegiality as its promotion criteria, with no specific weight assigned to research. Institute X requires 5 publications to be promoted to Associate Professor, and 8 to be promoted to Full Professor. Institute Y requires 4 publications and 6 publications to be promoted to Associate Professor and Full Professor, respectively. Table 1 offers details of the two promotion policies.

Both institutes are licensed by the UAE’s Commission for Academic Accreditation (CAA) and therefore are required to demonstrate full compliance with the national policies and regulations in terms of promotion and research expectations. According to the Commission for Academic Accreditation (2019) standards for licensure and program, institutions shall “define their expectations for faculty research and scholarly activity, and embodies these in appointment criteria, faculty performance evaluations and criteria for promotion.” That said, the way these national policies are enacted could be different considering the clear difference in the universities’ mandates and contexts.

2.3 The sample selected

The sample for this study was selected using a snowballing approach, a technique particularly useful in reaching participants who are closely connected through professional networks. Initially, a few full -time faculty members who spent at least 5 years at their current institute and who applied at least once for promotion were identified and interviewed. These initial participants were then asked to recommend other colleagues who meet the same selection criteria and could provide valuable insights into the study. The sample reached a point of saturation after interviewing 16 faculty members. Saturation was achieved when no new or relevant information emerged from the interviews, indicating that the data collected was comprehensive and sufficient to address the research questions.

The respondents were comprised of 63% males and 38% females. In terms of ranking, 38% of the participants were assistant professors, 38% were associate professors, and 25% were full professors. The results also showed that 19% of the sample had 5–9 years of experience, 38% had 10–14 years of experience, 31% had 15–19 years of experience, and 13% had 20 or more years of experience. All faculty members contacted accepted to participate in the study.

2.4 The types of data collected and analyzed

This was a non-experimental, descriptive qualitative study where data was collected using semi-structured interviews and document review. The study utilized an inductive approach to coding and analysis, in which the researcher attempts to make meaning of the data without the influence of preconceived notions, allowing the data to speak for themselves through a bottom-up analytical approach (Wyse et al., 2017). As highlighted by Hillebrand and Berg (2000), inductive coding works well with single cases or when one wants to explore a phenomenon.

Thematic analysis was used to sort and categorize data to make meaning of the participant’s responses during the interviews. Following a process of transcription and familiarization, sub-codes were identified and grouped together using a codebook to form codes, which, ultimately, were used to identify patterns in the data that will be presented as themes. Classical analysis as described by Leech and Onwuegbuzie (2007) was used where I counted how often a code was used to assist in determining which codes are most important. Finally, I moved from a semantic analysis (description of data) to a latent level analysis where data were interpreted to facilitate answering the research questions.

Similarly, an inductive conventional content analysis was conducted for coding and analysis of the faculty promotion policies, faculty handbooks, and faculty promotion records. Using a commercial Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis software, the process included data collection, developing an e-codebook, determining coding rules, iteration on the coding rules, data analysis, and interpretation of the results.

That said, the research design proposed for this study comes with a set of limitations. For instance, participants might tend to provide answers they think the researcher would want to hear. There is also the risk of being disadvantaged or penalized in case their identities are exposed. This could have implications for the reliability of the data gathered from the semi-structured interviews. Another limitation could be attributed to the sample size and the extent to which the findings of this study could be generalized to a larger context. Thus, until the study is replicated at a larger scale, its findings shall be considered indicative rather than conclusive.

Table 2 offers a summary of some of the key methodological decisions for this study.

3 Results

In an attempt to address the first research question, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 8 faculty members from each university. The aim was to understand the key characteristics of their research habitus: the history/background of the faculty members in addition to their perceived values, norms, and practices in the research field.

3.1 Identifying the key characteristics of the research habitus at the two institutes as perceived by the participants in this study

When asked about their perception of their past and current (structured) circumstances that probably lead them to become researchers, most of the participants from Institute X cited coming from middle-class families, with a few describing their background as ‘wealthy’. One of the respondents stated:

We had a steady income; I do not recall my family going through financial challenges. Nothing was extravagant or over the top… just a normal standard of living like most of my other friends at that time.

When discussing academic background, most of the participants from Institute X highlighted that they graduated what could be described as highly ranked or esteemed schools:

My father was a university professor, so he was very particular about our education. His university would allow us to study for free, but he refused. He gave me three options to choose from. All were top schools. The same thing (happened) with my brothers and sister.

On the other hand, there seemed to be a much wider variety in terms of social status and educational background for faculty members from Institute Y. One participant mentioned:

I come from a family of the labour class. My father was a farmer and my mother had to take care of seven children. Not all of us went to school. My brothers preferred to help Dad but I wanted to get a university degree, create something better for myself and my future family. It was the only way out.

Discussions about the more recent and future (structuring) structures of the participants and their implications on their identity as researchers revealed another noticeable difference between participants from Institute X and their counterparts from Institute Y. While all faculty from Institute X stated that they have been considering themselves as established researchers before joining their current institute, the majority of faculty members from institute Y believed that their journey as researchers took off at the current institute:

I was never asked to produce papers before. Only here. I think it is one of the requirements of the regulator. I have four papers so far, in 2 years, which is good. It’s more than many of my colleagues.

In contrast, a faculty member from Institute X stated:

I was recruited because of my research portfolio. It’s been my bread and butter for the past 15 years. It is who I am, what defines me as an academician. Now I bring this experience to help my graduate students do the same. Our role is to create knowledge.

Discussions with faculty members from University X revealed competitiveness as a key descriptor of their research culture. Terms like ‘tough’, ‘fierce’, ‘challenging’, ‘stand out’, and ‘proving worth’ with frequently used:

Have you seen the research expectations guidelines? It’s survival of the fittest. No one will tell you this, but I know some people who left because of this. They simply could not cope. It’s a tough job, very stressful, but it’s also what brings to the university its reputation, its elite status.

Another faculty from University X mentioned:

I used to do a lot of collaborative research in the past… Not anymore. If I am to invest in research, I would rather be the first or the only author. Everyone is doing research and you need to stand out. It looks better on your promotion portfolio.

On the other hand, a main theme emerging from discussions on values and norms with faculty members from University Y was collegiality and collaborative work in research:

We all come from the same sector, even those teaching in different programs. We speak the same language, understand each other. It makes it easier to work on projects together. I do not have time to work on a paper alone. It benefits all when we cooperate in research.

Another common theme extracted from the interviewees from University Y was a sense of confusion about their own roles due to the multiple responsibilities and expectations. For examples, one faculty member stated:

I think most of us are suffering from some sort of identity crisis. My classes, all the committees, the short (vocational) courses, and then research. Who are we in all of this? This is not about the faculty only; it is the entire institution. We need to know who we are first.

3.2 Exploring how research habitues at each institute reflect the research policies

Answering the second research question required conducting content analysis to examine the promotion policies and relevant documents at both institutes, identify the key areas of similarities and differences, and finally investigate whether any points of connection exist with the research habitus.

The content review aimed to aid in identifying possible points of connection between the promotion policies and the research habitus of the faculty members at each institute. Perhaps one of the main observations is the emphasis on collaborative research and how it possibly reflected on the faculty members’ perceptions and values of collegiality in research. Although both institutes make general references to collaborative research in different sections of their documents, only Institute Y includes collaborative research (under ‘Collegiality’) as part of the promotion criteria. Institute X only seems to refer to collaborative research to highlight that it is given less weight compared to single-author publications during the review process. As implied by the faculty responses when discussing their research habitus, faculty members from Institute Y described their research culture as collaborative and expressed high regard for collegiality in research.

A second observation was triggered by the fact that several participants from Institute Y were holders of an Assistant Professor rank. A look at the institutional documents revealed that a starking 53% of the entire faculty population were ranked as Assistant Professors, compared to 29% of faculty members from Institute X holding the same rank.

In an attempt to explore further possible connections, I opted to examine the faculty promotion trends at each institute. A look at relevant institutional documents and reports highlighted a stark difference between the two institutes. For Institute A, the promotion rates in the past 5 years ranged from 36 to 41%. On the other hand, the promotion rates at Institute Y ranged from 12 to 18% for the same period.

3.3 Investigating how are economic, social, and cultural capital are distributed in different fields of faculty promotion

In order to address the third research question, data were collected from the semi-structured interviews with the participants in this study.

Discussions with the faculty members indicated a strong emphasis on social capital in academic promotions. Several participants identified their educational background as an essential component of their professional identity and a priced asset when it comes to different forms of evaluations, including promotions. One faculty member stated:

My master’s is from Oxford while my Ph.D. is from Nottingham. Of course, it matters. Education is an investment for life, it stays with you forever. Today I carry this badge with a lot of pride. I’ve been there, among the best, and I’ve passed and now I’m here. I see how people panic about equivalencies with every performance evaluation. I’ve never had such problems.

One reoccurring theme pertained to the perceived negative impact of cultural background and ethnicity on their promotions:

I happen to come from a poor country. In my village, those who make it to high school are considered high achievers. I had to work so hard to make it, be where I am today. Because of that, some people think I should feel so lucky to be where I am today. Like I do not deserve a promotion no matter what I do. It’s like a dead end. This is not fair, I worked harder than most to be here, I still do, but they do not see it that way.

One female participant of African ethnicity also highlighted:

You think my skin colour does not matter? Who are we fooling? I walk into a room with my (African country) accent and they stop listening. You think when me and someone with (stereotypical description of a white male) apply for promotion. They choose me? It’s not how the world works.

There seemed to be an agreement on how access to financial capital could impact promotion outcomes, with the majority of faculty members highlighting either how the financial status of their families played a role in their education (subsequently supporting their promotion applications) or, perhaps more directly, how access to research grants supported their stance:

I got promoted (to a Professorial rank) last year and I feel a big part of it was the (name of prestigious grant). It is not only the amount, It is the fact that a team of experts agreed that my research deserved it. The announcement has been on the University’s website for months. I am sure the promotion committee did not miss that.

While looking at the demographics, it was observed that the majority of the expats from other Arab countries (i.e., excluding UAE nationals), felt that their limited access to financial funds at some point in their lives harmed their career trajectories.

Lastly, a few participants stressed the importance of being socially connected in improving the chances of a successful promotion:

You do not see those things when you first join. It takes a while. It is not necessarily a bad thing, not like favouritism or something like that. It’s like… they just need to remember your face. I think it’s called personal branding; I came to learn about it the hard way. Now I know that whoever is on the (promotion) committee, at least a few of them will recognize me.

Others also discussed how participating in formal and informal conferences and other venues can help:

The most important part of attending conferences is networking. The sessions are important but getting to meet the right people, it’s like getting membership in the elite club. Our sector is very specific, you know? We know each other now. We meet at conferences, discuss collaborations, and sometimes even review each other’s application forms (for promotion as part of external peer review).

4 Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the intersection of faculty promotion policies and research conceptions, perceptions, and norms as revealed by interviews and policy documents from two higher education institutes in the UAE.

4.1 The characteristics of the research habitus

While faculty from Institute X identified several similar characters when describing their habitus, there seemed to be a wider variety in terms of social status and educational background for faculty members from Institute Y. Additionally, it became clear that faculty members from institute X identified themselves as experienced researchers, with several participants from Institute Y being relatively new to the research world. This could be reflective of the hiring policies and priorities of the two institutions. As a research-intensive institution of higher education, Institute X may have prioritized the employment of faculty members with solid research experience and a more uniform academic profile. In contrast, perhaps the applied nature of Institute Y also led to recruiting faculty members who spent a large portion of their professional career in the fields as practitioners and only became academicians at a later stage of their lives. The demographics and requirements of Institute Y’s student body may also be a contributing factor to the institution’s more diverse faculty backgrounds. Applied colleges, including the one investigated in this study, typically serve a more diverse student population with a broad range of academic backgrounds and experiences, which may necessitate faculty members with diverse backgrounds and skills to meet their requirements. Occasionally, Bourdieu appears to be implying uniformity. In other cases, he emphasizes the uniqueness of each individual’s habitus while acknowledging the variety that exists even among people of the same culture. As individuals’ social paths vary from one another, so do their habitus, both within and across social groups (Reay, 2004).

These results may imply that Institute X faculty members with similar habitus and academic backgrounds may have a clearer route for promotion within the institution, as their research-oriented profile aligns with the institution’s priorities. Faculty members from Institute Y, on the other hand, may face more challenges in terms of career advancement and promotion because their backgrounds may not match as neatly with the institution’s objectives. It is essential to note, however, that diversity in faculty backgrounds can offer benefits to the institution, such as a broader range of perspectives, experiences, and skills. As a result, both institutes should weigh the advantages and disadvantages of their respective hiring policies and work to develop a fair and transparent promotion system that acknowledges and rewards various forms of capital and habitus.

When comparing the two institutes, faculty members from Institute X would describe their habitus as highly competitive where individual faculty need to prove their worth to survive, while their counterparts from Institute Y seemed to have a higher value for aspects of collaboration and collegiality. This may be attributed to several factors. For example, individual achievement and research output may be prioritized as main criteria for promotion and career advancement at Institute X. Faculty members may feel compelled to compete with one another to gain recognition and progress in their careers in this environment. This competitive environment can foster an individualistic culture in which faculty members are solely concerned with their own research objectives and interests. Institute Y, on the other hand, may value collaboration and collegiality as important components of their academic programs. This environment values collaboration and a shared sense of ownership over student learning outcomes. As a result, faculty members may believe that their success is inextricably linked to the success of their co-workers and the institution.

4.2 Research habitues and promotion policies

A comparison of the promotion policies adopted by each institute revealed more similarities than differences. Both institutes consider research contribution a key component of the review criteria for promotion, albeit Institute X allocates a weighted average of 60% and sets higher expectations for research in terms of the number of papers required and years of experience in the current rank. This could explain why most faculty members described their research habitus as competitive, fierce, and overly challenging. As discussed earlier, the neoliberalism ideology continues to play a key role in shaping academic policies, leading to a tournament-like system (Musselin, 2005) for faculty employment, evaluation, and promotion. The faculty review tournament model works by comparing teachers’ outputs, which motivates them to work harder so that they can rise in the ranks. Only applicants with more outstanding outputs than other applicable faculty are promoted, even if they meet the evaluation requirements for the jobs at the next level. Although typically linked to the economic field, neoliberalism uses institutions to change social and cultural norms and values, making economic principles the cornerstone of social structures and processes (Olssen and Peters, 2005; Ward, 2012). Smith and Coel (2018) suggested that teachers are unintentionally breeding hostility by fostering an atmosphere where aggression is rewarded, competition is celebrated, and short-term success is prioritized over long-term goals. Therefore, while encouraging outstanding performance, institutions shall pay close attention to the possible emergence of negative practices associated with tournament-like structures and competition.

On the other hand, the research habitus of Institute Y seems to be more aligned with the values of collegial work highlighted in the adopted promotion policy. That said, it shall be noted that collegiality, although generally favored, has been associated with a few challenges in recent years regarding promotion criteria (Fogg, 2002). Collegiality, as described by Bourdieu (1988), is a desire for group members to exhibit comparable traits and behaviors. For example, a new lecturer needs to assess the norms of the department and, at the very least, appear to conform to them in order to make a smooth transition into the group’s everyday life. In a university or any other workplace, new hires should be appreciated for the fresh perspectives they offer that can help a department grow beyond its current capabilities, as Bonner (2004) points out. Thus, it would be imperative to ensure that collegiality is not overshadowing the individuality and professional identities of those who are expected to broaden the scope of work in terms of research and scholarly activities.

Moreover, while teaching, research/scholarly achievement, and service have historically been the primary criteria for promotions, the inclusion of collegiality introduces new levels of ambiguity and the possibility of discrimination (DiGiorgio, 2010). Due to the subjective nature of the evaluation process and the lack of clear policies on evaluative criteria in universities, it becomes acceptable to attribute one’s inadequacy to a lack of collegiality or even merit, and evidence can be made or tweaked to support this claim (Trower, 1999).

Further examination of the institutional documents and reports revealed a stark difference between the two institutes in terms of recent promotion trends. For Institute X, the promotion rates in the past 5 years ranged from 36 to 41%. On the other hand, the promotion rates at Institute Y ranged from 12 to 18% for the same period. This could raise questions on why, despite the relatively less challenging research requirements, faculty at Institute Y has had such a low promotion rate. One possible reason could be the relatively short experience with research due to spending big positions in their careers as practitioners and industry experts rather than traditional academicians. Many professors in their late careers at new universities were hired primarily for their teaching abilities, as pointed out by Hazelkorn and Moynihan (2010). The challenge for them is to participate in and meet the requirements for professional education and research endeavors. Bourdieu used the metaphor of a “fish in the water” to explain how one’s habitus and capital can enable success in a particular field (Bourdieu, 1990). In the realm of applied research, professors whose primary asset is their years of professional expertise report feeling underappreciated. Although some are highly regarded as industry experts, these faculties do not feel like ‘fish in water’. That said, this remains an assumption until further substantiated. The promotion process is nothing short of complex and several other factors could impact its outcomes.

It is also possible that the use of clear weighted averages for each promotion criteria, including research output, at Institute X may be more transparent and structured, which could make it easier for faculty members to understand what is required to achieve promotion. The unspecified weight allocated to research productivity could arguably have led to the reported confusion and uncertainty among faculty members about what is expected of them. This lack of clarity could contribute to the lower promotion rates at Institute Y.

What could be the negative implications of these findings? The lower promotion rates at Institute Y could lead to demotivation and a sense of frustration among faculty members who feel that their contributions are not being adequately recognized. This could lead to higher turnover rates and a loss of talent at the institution. At Institute X, the higher promotion rates may lead to a culture of individualism and competition, which could hinder collaboration and interdisciplinary research.

Therefore, it is essential for institutions to review and revise their promotion policies to ensure that they are clear, transparent, and equitable in terms of future promotion trajectories for faculty members at each institute. Establishing mentoring programs and providing opportunities for professional development could also assist faculty members in understanding what is required for promotion. In addition, institutions could consider revising their promotion criteria to better reflect the nature of their academic programs and the institution’s culture and values.

4.3 Capital distribution and its implications on promotion practices

The last section of the study was allocated to investigate the interplay of different types of capital and how their distribution can impact promotion outcomes. In particular, most participants in this study perceived cultural capital as a main contributor to their research identities and career trajectories. There seemed to be close connections between cultural and economic capital. Faculty members who came from families with stable access to income carried on to join the highly-ranked institution in an example of economic capital transforming to cultural, and at a later stage, institutional capital.

The connection between economic and cultural capital may have significant implications for the fairness and transparency of promotion policies and practices. Individuals who lack access to economic capital may be at a disadvantage if cultural capital is perceived, whether consciously or unconsciously, as a prerequisite for academic success and career advancement. Individuals from specific socioeconomic origins may be underrepresented in higher education institutions, resulting in a lack of diversity and representation in the academic workforce.

In addition, if promotion policies and practices heavily rely on cultural capital, there is a danger of perpetuating existing power dynamics and reproducing inequalities. Regardless of their research output or merit, faculty members from prestigious institutions or with prior connections to influential individuals in the field may have an advantage over others. This can create a situation in which the promotion process is not transparent or merit-based, leading to frustration and dissatisfaction among faculty members as well as potential negative effects on the culture of the institution.

Consequently, institutions of higher education should strive to cultivate a more equitable and inclusive environment in which all faculty members have access to resources and opportunities to develop their cultural capital. This can be accomplished through targeted support programs, mentorship opportunities, and recruitment pool diversification initiatives. In addition, promotion policies and practices should emphasize merit-based evaluations of research output and influence. Such measures can contribute to the development of a more diverse and inclusive academic community, in which individuals from various backgrounds and experiences can contribute to the advancement of knowledge and scholarship.

Perhaps expectedly, different distributions of cultural capital also meant that different faculty members felt the promotion process was not as fair and transparent as it should be. Issues of skin color, ethnicity, and gender bias were raised at different stages of the interviews, with some participants still believing promotion decisions remain to favor those of certain ethnicity and cultural backgrounds. Undoubtedly, the is a serious concern that suggests that there may be biases in place that are hindering the progress of certain individuals, regardless of their qualifications and merits.

One potential explanation for this bias is that the promotion committees themselves may be lacking in diversity, making decisions that favor people from specific cultural and ethnic backgrounds. Furthermore, informal networks and relationships may influence decision-making, producing a “glass ceiling” effect for certain groups of people. Not only would this have a negative impact on individual faculty members’ career paths, but it could also contribute to a lack of diversity in the academic community. This can lead to a homogeneous academic culture that lacks innovation and inclusivity, eventually impeding the institution’s overall growth and development.

To address these issues, it is critical to include measures in the promotion process that encourage diversity and inclusivity. This can be accomplished by ensuring that promotion committees are diverse and representative of the institution’s staff, as well as by setting clear, transparent, and impartial promotion criteria. Additionally, training for promotion committees to help them spot and mitigate potential biases in the decision-making process may be helpful.

In order to better the promotion process, it is crucial to foster a culture of openness and transparency in which faculty members are encouraged to share their insights and criticism. For example, faculty members can be provided with opportunities to share their research and accomplishments with the larger academic community. In addition, regular channels for feedback and communication between faculty members and promotion committees can be established. Previous research has shown that when faculty members have a more positive view of the promotion process, they are more invested in their jobs, happier in their careers overall, and less likely to leave their positions (Ambrose and Cropanzano, 2003). Whether the academic system and its means of evaluating the worth of its faculty’s contributions have kept pace with societal goals like ensuring equal opportunities for employment and career advancement regardless of gender, ethnicity, or other personal characteristics is a question that López et al. (2018) concluded deserves more attention.

Another issue raised was some faculty members’ confusion about their professional identities as a result of the multiple roles, expectations, and requirements for promotion. One potential source of this confusion is the institute’s lack of clear communication and rules on promotion criteria and faculty member expectations. This lack of clarity can lead to ambiguity in faculty members’ duties and standards, making it difficult for them to align their efforts with promotion requirements. As a result, faculty members who prioritize teaching may feel undervalued and underappreciated during the promotion process, as their efforts toward teaching and the impact they have on students may not be adequately recognized or rewarded. This can result in a lack of motivation and work dissatisfaction, which can have a negative impact on teaching quality and overall institutional performance.

This has been of particular concern to those who perceive teaching as their main function in higher education. External accountability means that institutions are tasked with providing a foundation of evidence for quality teaching, conducting collaborative research, and engaging with the research community. At the same time, they must strive to develop highly skilled and employable graduates (Kyvik and Lepori, 2010). It is difficult for educational organizations to find common ground between the academic, research, and professional spheres. This could explain why some participants in this study have referred to an identity crisis at both the personal and organizational levels as a result of the divergent standards, norms, and practices of these multiple worlds (McNamara, 2010). Individuals who are repositioning themselves toward numerous academic orientations and merging collectivizes may experience identity confusion as outlined by Melles (2011).

Institutes can mitigate this by incorporating teaching-focused promotion criteria that recognize the efforts of faculty members who value teaching. To reduce ambiguity and confusion, faculty members can be provided with clear communication and instructions on the promotion process and criteria. Furthermore, institutes can offer faculty members professional development opportunities to help them improve their teaching skills and build their teaching-focused promotion criteria. Higher education institutes can promote a culture of teaching excellence and ensure the fair and transparent promotion of all faculty members by recognizing and rewarding the efforts of faculty members who prioritize teaching.

5 Conclusion and recommendations

This study aimed at exploring the intersections of faculty promotion, research habitus, and capital distribution. In an attempt to achieve this goal, it examined the research habitus from two higher education institutions in the UAE; one was traditionally academic while the other was more applied. While comparing research habitus to the institutional promotion policies, the study explained certain values, perceptions, and practices related to the competitiveness of the research habitus as well as the collaborative nature and overall collegiality as practiced in the research world. Finally, the study explored some of the hidden rules of the promotion world, highlighting areas like background education, professional experience, cultural background, ethnicity, and social networks as some of the factors that may play a role in the promotion outcomes.

Several recommendations can be made based on the study’s findings to address the issues found. Firstly, it is critical to acknowledge the role of habitus and capital in shaping views in the research world. This can be accomplished through education and training programs aimed at creating a more collaborative and inclusive research culture that values various forms of capital and encourages diverse research practices.

Second, promotion policies should be reviewed and revised to ensure that they are transparent, equitable, and consistent with the research culture’s values. This could entail revising promotion criteria, establishing clear performance metrics, and establishing chances for mentoring and professional growth.

Third, it is critical to handle the unknown variables that could impact promotion outcomes, such as prior education, affiliations, professional experience, cultural background, ethnicity, and social networks. This can be accomplished by diversifying promotion committees, developing clear guidelines for assessing applicants, and providing opportunities for networking and community building.

Fostering cultures of diversity and inclusion is also essential. Creating opportunities for underrepresented groups, encouraging diversity in hiring and promotion, and ensuring that policies and practices are inclusive and equitable are all examples of such measures. It is critical to realize that diversity and inclusion are not only moral imperatives, but also critical factors in fostering innovation and improving research quality. We can help to ensure that all researchers have equal opportunities to contribute to the advancement of knowledge and make significant contributions to society by encouraging a more diverse and inclusive research culture.

In conclusion, it is critical to realize that addressing these problems will necessitate a collaborative effort from all research stakeholders, including researchers, policymakers, and institutional leaders. A collaborative and multidisciplinary strategy that emphasizes transparency, fairness, and inclusivity is critical for developing a more equitable and effective research culture that values diverse forms of capital and promotes the growth and development of all researchers.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AE developed its conception and design. AE organized the database, conducted the interviews, performed the analysis, and wrote all sections of the manuscript. The author performed several revisions of the manuscript and finalized the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albatch, P. G. (2008). The complex roles of universities in the period of globalization. In Higher Education in the World 3: New Challenges and Emerging Roles for Human and Social Development (3rd ed). 5–14. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2099/8111

Ambrose, M. L., and Cropanzano, R. (2003). A longitudinal analysis of organizational fairness. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 266–275. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.266

American Association of Colleges and of Pharmacy . Pharmacy Faculty Demographics and Salaries Report. American Association of Colleges and of Pharmacy. (2023). Available at: https://www.aacp.org/research/institutional-research/pharmacy-faculty-demographics-and-salaries (Accessed June 7, 2024).

Annala, J., Mäkinen, M., Lindén, J., and Henriksson, J. (2020). Change and stability in academic agency in higher education curriculum reform. J. Curric. Stud. 54, 53–69. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2020.1836261

Azman, N., Che Omar, I., Md Yunus, A. S., and Zain, A. N. M. (2016). Academic promotion in Malaysian public universities: a critical look at issues and challenges. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 42, 71–88. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2015.1135114

Barrow, M., and Grant, B. (2018). The uneasy place of equity in higher education: tracing its (in)significance in academic promotions. High. Educ. 78, 133–147. doi: 10.1007/s10734-018-0334-2

Birtwell, J., Duncan, R., Carson, J., and Chapman, J. (2020). Bridging the gap between secondary and tertiary education for students with refugee backgrounds with Bourdieu. Comp. Int. High. Educ. 12, 112–139. doi: 10.32674/jcihe.v12iwinter.1954

Blakely, M. L., Chahine, E. B., Emmons, R. P., Gorman, E. F., Astle, K. N., Martello, J. L., et al. (2023). AACP faculty affairs standing committee report of strategies for faculty self-advocacy and promotion. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 87:100045. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpe.2022.07.001

Bourdieu, P. (1988). Vive la Crise!: for heterodoxy in social science. Theory Soc. 17, 773–787. doi: 10.1007/BF00162619

Bourdieu, P. (1994). Other words: Essays towards a reflexive sociology. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1995). “The forms of capital” in Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. ed. J. G. Richardson (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press).

Bourdieu, P., and Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bülbül, T. (2020). Socio-economic status and school types as the determinants of access to higher education. Eğitim Bilim. 46:8755. doi: 10.15390/eb.2020.8755

Commission for Academic Accreditation (2019). Standards for institutional licensure and program accreditation. United Arab Emirates: Ministry of Higher Education.

DiGiorgio, C. (2010). Capital, power, and habitus: how does Bourdieu speak to the tenure process in universities? J. Educ. Thought 44, 27–40.

Durodoye, R., Gumpertz, M., Wilson, A., Griffith, E., and Ahmad, S. (2019). Tenure and promotion outcomes at four large land Grant universities: examining the role of gender, race, and academic discipline. Res. High. Educ. 61, 628–651. doi: 10.1007/s11162-019-09573-9

Faria, J. R., Loureiro, P. R., Mixon, F. G., and Sachsida, A. (2013). Faculty promotion in academe: theory and evidence from U.S. economics departments. J. Econ. Econ. 56, 1–27.

Fudiyartanto, F. A., and Stahl, G. (2023). Theorizing the professional habitus: operationalizing Bourdieu to explore the role of pedigree in Indonesian higher education. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 1–16, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2023.2291324

Gander, M. (2022). A holistic career framework: integrating Bourdieu and career theory. Aust. J. Career Dev. 31, 14–25. doi: 10.1177/10384162211070081

Grenfell, M., and James, D. (1998). Bourdieu and education: Acts of practical theory. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Hanley, P. F., and Forkenbrock, D. J. (2006). Making fair and predictable salary adjustments for faculty of public research universities. Res. High. Educ. 47, 111–127. doi: 10.1007/s11162-005-8154-5

Hassan, S. L. (2022). Reducing the colonial footprint through tutorials: a south African perspective on the decolonisation of education. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 36:4325. doi: 10.20853/36-5-4325

Hazelkorn, E., and Moynihan, A. (2010). Transforming academic practice: Human resource challenges. London: Springer.

Heffernan, T. A. (2017). A fair slice of the pie? Problematising the dispersal of government funds to australian universities. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 39, 658–673. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2017.1377965

Heffernan, T. A. (2021). Examining university leadership and the increase in workplace hostility through a bourdieusian lens. High. Educ. Q. 75, 199–211. doi: 10.1111/hequ.12272

Hillebrand, J. D., and Berg, B. L. (2000). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Teach. Sociol. 28:87. doi: 10.2307/1319429

Hindhede, A. L., and Højbjerg, K. (2020). How teachers balance language proficiency and pedagogical ideals at universities in indigenous and postcolonial societies: the case of the University of Greenland. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 21, 439–452. doi: 10.1080/15348458.2020.1832496

Jayakumar, U. M., and Page, S. E. (2021). Cultural capital and opportunities for exceptionalism: Bias in university admissions. J. High. Educ. 92, 1109–1139. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2021.1912554

Katartzi, E., and Hayward, G. (2019). Conceptualising transitions from vocational to higher education: bringing together Bourdieu and Bernstein. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 41, 299–314. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2019.1707065

Kovács, K., and Pusztai, G. (2023). An empirical study of Bourdieu’s theory on capital and habitus in the sporting habits of higher education students learning in central and Eastern Europe. Sport Educ. Soc. 29, 496–510. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2022.2164266

Kulp, A. M., Pascale, A. B., and Wolf-Wendel, L. (2021). Clear as mud: promotion clarity by gender and BIPOC status across the associate professor lifespan. Innov. High. Educ. 47, 73–94. doi: 10.1007/s10755-021-09565-7

Kyvik, S., and Lepori, B. (2010). Research in higher education institutions outside the university sector. London: Springer.

Leech, N. L., and Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative data analysis tools: a call for data analysis triangulation. Sch. Psychol. Q. 22, 557–584. doi: 10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.557

Levin, J. S., Martin, M. C., and López-Damián, A. I. (2020). University management, the academic profession, and neoliberalism. Albany: SUNY Press.

López, M., Margherio, C., Abraham-Hilaire, L., and Feghali-Bostwick, C. (2018). Gender disparities in faculty rank: factors that affect advancement of women scientists at academic medical centers. Soc. Sci. (Basel) 7:62. doi: 10.3390/socsci7040062

McKiernan, E. C., Schimanski, L. A., Nieves, C. M., Matthias, L., Niles, M. T., and Alperin, J. P. (2019). Use of the journal impact factor in academic review, promotion, and tenure evaluations. eLife 8:47338. doi: 10.7554/elife.47338

McNamara, M. S. (2010). Where is nursing in academic nursing? Disciplinary discourses, identities and clinical practice: a critical perspective from Ireland. J. Clin. Nurs. 19, 766–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03079.x

Melles, G. (2011). Art, media and design research and practice: views of educators in a 'new' Australian university. Res. Post-Compuls. Educ. 16, 451–463. doi: 10.1080/13596748.2011.627152

Musselin, C. (2005). European academic labor markets in transition. High. Educ. 49, 135–154. doi: 10.1007/s10734-004-2918-2

Olssen, M., and Peters, M. A. (2005). Neoliberalism, higher education and the knowledge economy: from the free market to knowledge capitalism. J. Educ. Policy 20, 313–345. doi: 10.1080/02680930500108718

Omar, I. C., Yunus, A. S. M., Azman, N., and Ahmed Nurulazam, M. Z. (2015). Academic promotion of higher education teaching personnel: Country report for Malaysia. Penang: National Higher Education Research Institute.

Reay, D. (2004). "it's all becoming a habitus": beyond the habitual use of habitus in educational research. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 25, 431–444. doi: 10.1080/0142569042000236934

Reay, D. (2021). The working classes and higher education: meritocratic fallacies of upward mobility in the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Educ. 56, 53–64. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12438

Saunders, D. B. (2010). Neoliberal ideology and public higher education in the United States. J. Crit. Educ. Policy Stud. 1, 42–77.

Schaffer, S. (2016). Bourdieu, Pierre and Roger Chartier, the sociologist and the historian. Can. J. Sociol. 41, 248–252. doi: 10.29173/cjs26067

Schimanski, L. A., and Alperin, J. P. (2018). The evaluation of scholarship in academic promotion and tenure processes: past, present, and future. F1000Research 7:1605. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.16493.1

Smith, F., and Coel, C. R. (2018). Workplace bullying policies, higher education and the first amendment: building bridges not walls. First Amend. Stud. 52, 96–111. doi: 10.1080/21689725.2018.1495094

Smith, S., and Walker, D. (2021). Scholarship and academic capitals: the boundaried nature of education-focused career tracks. Teach. High. Educ. 29, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2021.1965570

Soudien, C., Apple, M. W., and Slaughter, S. (2013). Global education inc: new policy networks and the neo-liberal imaginary. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 34, 453–466. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2013.773734

Stavrou, S. (2022). Structuring forms of transition from higher education to employment: bridging Bernstein and Bourdieu in understanding mismatch. J. Educ. Work. 35, 124–138. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2022.2036709

Sutherland, K. A. (2017). Constructions of success in academia: an early career perspective. Stud. High. Educ. (Dorchester-on-Thames) 42, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1072150

Ward, S. C. (2012). Neoliberalism and the global restructuring of knowledge and education. Abingdon: Routledge, 60.

Wyse, D., Selwyn, N., Smith, E., and Suter, L. (2017). The BERA/SAGE handbook of educational research.

Keywords: promotion policies, research culture, habitus, capital, higher education

Citation: Elhakim A (2024) The intersection of promotion policies, research habitus, and capital distribution: a qualitative case study of two higher education contexts in the United Arab Emirates. Front. Educ. 9:1237459. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1237459

Edited by:

Riki Tesler, Ariel University, IsraelReviewed by:

Enver Zerem, University Clinical Center Tuzla, Bosnia and HerzegovinaAtya Nur Aisha, Telkom University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2024 Elhakim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ahmed Elhakim, YWVsaGFraW1Ac21hLmFjLmFl

Ahmed Elhakim

Ahmed Elhakim