- 1Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 2College of Education and Human Development, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, TX, United States

- 3College of Health and Human Performance, University of Florida, Florida, FL, United States

In this study, we investigated graduate students’ financial security during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the Spring 2022 semester, the continued changes brought on by the precautionary measures implemented presented difficulties for both faculty and graduates. In this mixed methods study, we surveyed graduate students (N = 258) at a public research university to explore the pandemic’s effects on their financial security. Through the sign test analyses, we found a significant decrease in graduate students’ financial security scores during the pandemic, and particular groups of students were more susceptible to decreased financial security. The thematic analysis further explored the financial security decrease and identified inflation and economic downturns, and the suspension of work or financial support as two main challenges graduate students confronted during the pandemic. Both quantitative and qualitative findings reflected the financial stress and hardship confronted by graduate students during the pandemic. It was implied that extra financial support and consultation should be provided to students with meager stipends or student loans. The results further informed the academic community to foster the culture of care inside academia, by addressing graduate students’ financial concerns properly in the post-pandemic period.

Introduction

Starting with the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States of America in March 2020, a series of public health initiatives were taken by the US government. Under the advice of the (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020), public schools began to close as a high-profile response to slow the spread of COVID-19. During the pandemic, students across educational levels experienced an upsurge in issues and obstacles as a result of this unprecedented global health crisis. For graduate students, those issues included but were not limited to problems with their physical and mental health (Chrikov et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020), financial insecurity (Kee, 2021; Walsh et al., 2021), and the lack of academic support and mentoring (Brownlow et al., 2022). These problems are not new to graduate students and are highly associated with each other. Previous research reported that graduate students’ financial concerns are fundamental to their mental health (Charles et al., 2022). Graduate students, regardless of their study areas, would have poorer psychological conditions if they suffered from financial distress. In addition, the correlation between financial security and academic progress is also significant. Wollast et al. (2018) and Hardré et al. (2019) identified financial constraints or concerns as a main factor in predicting graduate students’ drop-out rate. Under that condition, major setbacks such as global pandemics, delayed timeframes, and loss of access to resources have caused many students to be in difficult financial situations and to be ill-prepared to handle unforeseen expenses (Evans et al., 2018; Sverdlik et al., 2018; Jenei et al., 2020; Bozyiğit, 2021; Mutch and Peung, 2021).

In the past few years, most studies investigating the impact of COVID-19 on the educational system focused mainly on students’ mental health (e.g., Bayham and Fenichel, 2020; Viner et al., 2020; Pfefferbaum, 2021), or academic achievement (e.g., Kuhfeld et al., 2020; Basith et al., 2021). In contrast, the financial security of students during the pandemic was rarely investigated (Kee, 2021; Walsh et al., 2021). Financial well-being is especially important for graduate students, who, unlike undergraduate students, are usually considered financially independent (Strayhorn, 2010). So the purpose of this study is to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on graduate students’ financial security at a public institution of higher learning. Despite the fact that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on students have already been investigated in other studies, this one is innovative for three reasons. In the first place, it focuses specifically on graduate students rather than undergraduates or all students. Secondly, while previous research has focused mainly on the physical or psychological aspects of graduate students’ well-being, the goal of this research is to understand how COVID-19 affected financial security, which was at considerable risk given the school closure and school budget constraints. Last but not least, this study seeks to investigate how graduate students at a public research university, which is known for its rigorous academic standards and high levels of research activity, are financially impacted.

Literature review

Financial security and graduate students’ academic success

According to National Center for Education Statistics (2023), approximately 3.2 million students were enrolled at the post-baccalaureate level by fall 2021. Unlike undergraduate students, graduate students are more likely to hold multiple familial or financial responsibilities during their education (Hyun et al., 2006; Ipsos, 2017). In Sallie Mae’s study report (Ipsos, 2017), 1,597 graduate students in the United States were interviewed in 2017 by Ipsos Public Affairs. They were asked various questions regarding their graduate school funding sources and educational expenses. Based on the report, graduate students were found to be more self-reliant in funding their education than undergraduate students. Furthermore, compared with undergraduate students, graduate students were less likely to apply for Federal Student Aid. By the fall of 2017, only 18% of the full-time graduate students in the United States had their graduate education funded by graduate assistantships, and only 28% had grants, scholarships/fellowships, or tuition waivers from the universities. The average amount received by full-time graduate students who had assistantships in the academic year 2016–2017 was only 4,304 dollars. In contrast, the average annual amount they spent on their graduate education for the academic year was 24,812 dollars.

Financial support, or financial opportunities, has been widely documented by researchers as a crucial factor for graduate students’ learning persistence and academic progress (e.g., Gururaj et al., 2010; Litalien and Guay, 2015; Cadaret and Bennett, 2019). In a study conducted by Sverdlik et al. (2018), researchers reviewed 163 previous empirical studies to explore factors affecting students’ doctoral learning experience. Several external factors (i.e., supervision, personal/social lives, department structures, and socialization, financial opportunities) and internal factors (i.e., motivation, writing skills, and regulatory strategies, academic identity) were identified to be important for doctoral students’ achievement and well-being. In regard to the financial opportunities, the researchers specifically mentioned that more financial opportunities were correlated to higher overall satisfaction with the learning experience and a lower attrition rate. Similar findings were reported by Gururaj et al. (2010), who revealed that financial aid for post-secondary students could promote their academic learning persistence. In another study conducted by Cadaret and Bennett (2019), researchers also noted that financial insecurity was significantly associated with academic distress and lower grade point average.

In addition to graduate degree completion and academic achievement, financial security is also found to be highly correlated with graduate students’ mental well-being (Eisenberg et al., 2007; Oswalt and Riddock, 2007; Evans et al., 2018). Hyun et al. (2006) argue that financial support plays a critical role in maintaining mental health among graduate students in North America. The researchers found that financial concerns and career-related problems were among the main reasons why graduate students sought counseling services at universities. Similarly, by analyzing a secondary dataset containing 4,477 graduate students’ demographic information and anxiety disorder information, Barton and Bulmer (2017) found that students with financial problems had a significantly higher rate of depression and anxiety disorders. In another study conducted by Charles et al. (2022), survey responses from 613 post-secondary students enrolled in the University of California were collected and analyzed. Researchers reported a significant association between participants’ financial hardship and their depression symptoms.

Despite the importance of financial security for graduate students, Sverdlik et al. (2018) found that many graduate students do not fully understand the financial conditions they would confront at the time of enrollment, resulting in decision-making without appropriate consideration of funding opportunities and insufficient knowledge of financial planning. For students with fixed incomes, which is usually the case for graduate students with assistantship stipends, their ability to overcome the financial crisis is very limited. The situation is even more challenging for graduate students who hold student loans. Researchers have found that student loan is a strong predictor for financial insecurity and college education discontinuation (e.g., Archuleta et al., 2013; Britt et al., 2015). In a study conducted by Archuleta et al. (2013), it was found that student debt was significantly associated with college students’ financial anxiety. The researchers further pointed out that students from low socioeconomic families, financially independent students, and ethnic minorities were especially vulnerable to financial anxiety.

Prior studies (e.g., Litalien and Guay, 2015; Sverdlik et al., 2018; Cadaret and Bennett, 2019) have repeatedly shown that financial security is highly correlated with graduate students’ learning persistence and academic progress, as well as their mental health (e.g., Hyun et al., 2006; Barton and Bulmer, 2017; Charles et al., 2022). It was also pointed out that most graduate students were not appropriately informed about the financial conditions they might have during their graduate learning before they started their graduate programs (Sverdlik et al., 2018). For most graduate students, their abilities to overcome financial crises are very limited, especially those who receive fixed stipends through their assistantships and those who hold student loans. Given the previous study findings, it is necessary to investigate graduate students’ financial conditions during COVID-19, as the findings could help policymakers and school administrators understand graduate students’ challenges and issues better. A better understanding of the challenges and issues could therefore inform a build-back-better plan in the post-pandemic period and future disaster or emergency response strategies. However, in contrast to the well-document importance of financial security to graduate students, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their financial conditions has not yet been fully explored.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on graduate students

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a rapid and significant reaction was taken by educational institutes in the way the education was delivered. The uncertainties caused by the pandemic inevitably resulted in challenges for graduate students in maintaining financial security and mental well-being (Kee, 2021). Although researchers pointed out that support from their advisors, programs, or departments could help release mental issues caused by financial hardship (Vakkai et al., 2020; Charles et al., 2022), the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic made it extremely difficult for graduate students to seek support from others.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the in-person graduate student instructions were changed to an online format in most of the research institutes. Under that condition, graduate students’ access to advisory and mentorships was highly restricted. As Kee (2021) found, students during this time were not able to interact with their colleagues and instructors in person. Their research or learning was abruptly turned into virtual platforms, which made it hard to seek help or advice from their colleagues or faculty advisors. In addition to the pandemic altering their research and education, the pandemic also heavily altered the personal lives of graduate students. Some graduate students felt difficult to stay concentrated on their work when they suddenly had to work from home (Alsandor and Yilmazli Trout, 2020; Zahneis, 2020). Graduate students who were also parents suddenly needed to homeschool their children while attempting to maintain progress on their coursework and attend classes virtually (Bal et al., 2020; Trout and Alsandor, 2020). The workload for graduate students who also held jobs as instructional designers, university administrators, and other professionals multiplied as they navigated the move to online learning. In a study conducted by Bal et al. (2020), researchers revealed the concerns of graduate students from different perspectives. Graduate students who have children often sacrifice their own academic progress in order to devote more time to caring for their families. Some graduate students who are responsible for instructional designing experienced unprecedented high work demand by switching all the face-to-face courses to online platforms. Graduate teaching assistants confronted different challenges to maintaining efficient course instructions and clear communications in handling all of their courses online.

Additional struggles mounted from increased psychological stresses (Sahu, 2020) and fear of the pandemic itself (Wang et al., 2020). These all impacted graduate students’ ability to complete their coursework and maintain their everyday lives (Alsandor and Yilmazli Trout, 2020; Jenei et al., 2020; Tasso et al., 2021). In a study concerning graduate students’ well-being (Alsandor and Yilmazli Trout, 2020), researchers found that, among the 32 graduate student participants, more than half of them expressed they felt concerned, stressed, and lonely during the pandemic period. Under that condition, many graduate students struggled to stay concentrated and have their studies or research finished as planned. Similar results were found by Tasso et al. (2021). Based on the survey data collected from more than 134,000 international college students from a U.S. university. The researchers revealed that college students were affected by the pandemic in their concerns about networking, coursework completion, as well as mental problems such as feelings of anxiety and depression. In another study conducted by Wang et al. (2020), By collecting survey responses in regard to mental health from 2031 post-secondary students, it was found that the majority of the students (71.26%) experienced increased stress/anxiety levels during the pandemic while no more than a half of them were able to cope with the mental health problems appropriately during the time. Furthermore, 77.17% of the participants indicated that the increased anxiety/stress was caused by their fear and worry about their financial situation. Additionally, Jenei et al. (2020) also pointed out that the financial challenges confronted by graduate students were from unexpected expenses due to extended timelines, limited access to funding, and uncertain future career.

In sum, during the pandemic, students at the post-secondary level confronted various issues and problems, which included but were not limited to increased workload, limited access to mentor-ship and advisory, physical and mental health issues, and financial insecurity. As most of the studies investigating the COVID-19 impact on graduate students focused mainly on their mental well-being and psychological health, studies investigating the COVID-19 impact on graduate students’ financial security are still minimal. Most graduate students, unlike undergraduate students, rely mainly on themselves to financially support their graduate studies. Their financial security is fundamental for their mental health and academic success. The investigation of their financial condition during the pandemic is urgently needed to inform mitigation plans to build back better in the post-pandemic period. So in this study, we addressed this issue by collecting surveys from graduate students in a public research university in the U.S. By analyzing both the quantitative and qualitative data, we aim to describe the financial conditions graduate students experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic and explore whether COVID-19 impacted their financial security. Two research questions anchored this study:

1. Is there any impact of COVID-19 on graduate students’ financial security?

2. What are the underlying patterns of graduate students’ financial security during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Theoretical framework

This study is informed by the hierarchy of needs proposed by Maslow (1954). According to Maslow, there are five levels of needs: physiological, safety, belongingness and love, esteem, and self-actualization. These needs form a hierarchy. Only when the basic physiological and safety needs are fulfilled can humans pursue higher psychological and self-fulfillment needs. The more the basic needs are insecure, the more psychologically disturbed an individual will be. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs has been widely discussed by researchers and scholars in decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic in various areas, such as public health (Ryan et al., 2020), economy (Duygun and Şen, 2020), and education (Ansorger, 2021). The researchers shared the same point of view by arguing that basic physiological and safety needs were mostly impacted by the pandemic and hence called for extra attention on addressing the basic needs in decision-making or mitigation plan designing.

In the current study, financial security represents one of the critical components of physiological and safety needs. In order for graduate students to fully engage in their research and studies, their sources of medical care and financial income must be secure. Throughout the world, COVID-19 and precautionary measures to combat the pandemic both had significant detrimental effects on people’s ability to fulfill their hierarchy of needs, with particularly significant impairment of financial and social needs (Bozyiğit, 2021). Students were particularly negatively impacted by high levels of stress and isolation and reduced access to resources (Bozyiğit, 2021; Mutch and Peung, 2021). In this study, in order for graduate students to be able to learn and innovate, their basic needs of physiological safety must be met. Through this perspective, we recognized graduate students’ financial security as a fundamental construct of their graduate education pursuit and examined how it was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants

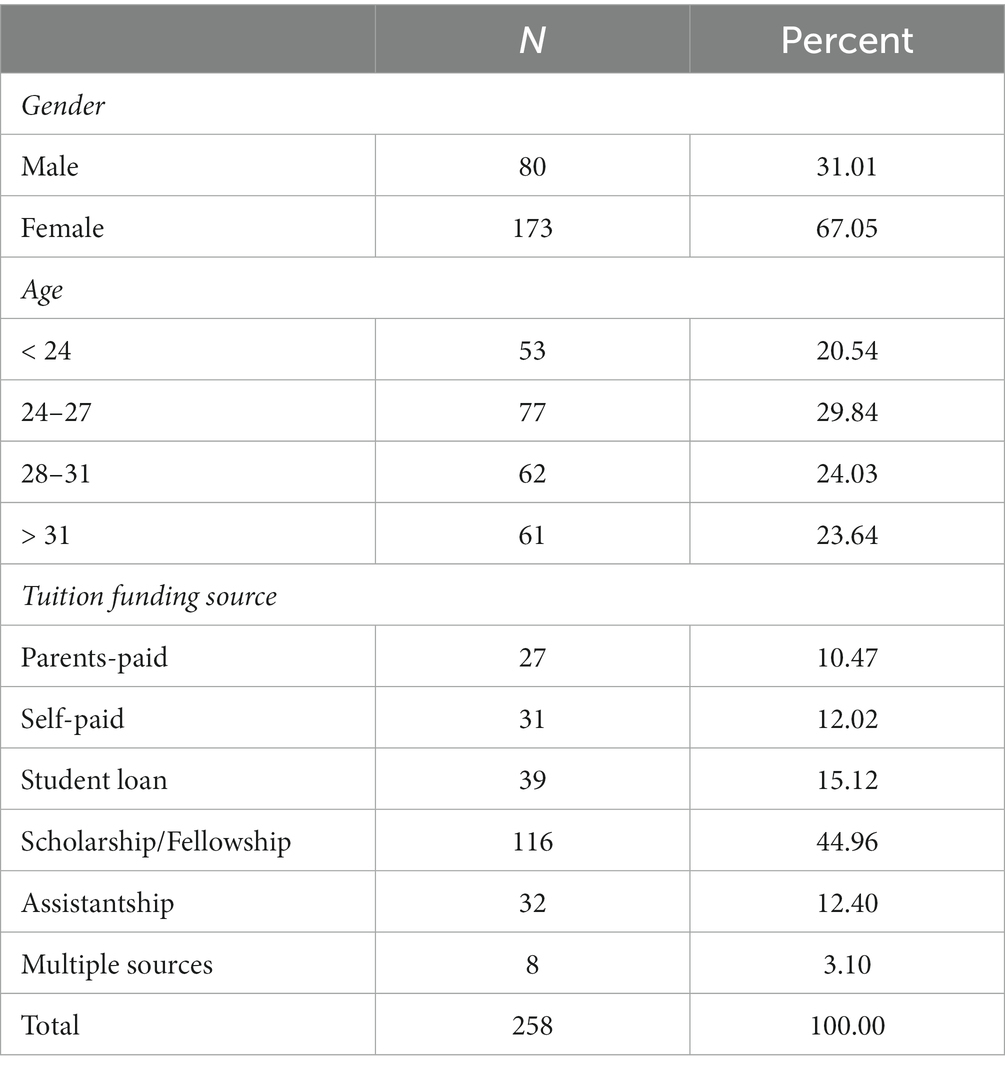

Among the 258 graduate students who finished the survey with consent, 173 of them were female, and 80 of them were male, five of them did not provide their gender information. Most of them (29.84%) were between the ages 24–27 (N = 77), 24.03% of them (N = 62) were in the age range 28–31, 23.64% of them (N = 61) were older than 31, and 20.54% of them were younger than 24 (N = 53). The average age of participants was 29.12. In regard to their tuition funding sources, most of them (N = 116) reported that they had a scholarship/fellowship to cover their tuition, 32 of them were working as graduate assistants, 39 of them had student loans, and 58 of them funded their tuition by themselves or supported by their parents. Detailed information is shown in Table 1.

Methods

This study is part of a larger research project exploring the effect of COVID-19 on graduate students at a public research university in a west-south central state of the United States. Following an explanatory sequential design (Ivankova et al., 2006; Subedi, 2016), we used a mixed methods approach in this study. By conducting a quantitative analysis of participants’ survey questions responses and a qualitative analysis of their open-ended question responses, we investigated the impact of COVID-19 on graduate students’ financial security and explored their financial concerns. By fall 2021, the university had more than 10,000 graduate and professional students enrolled in more than 260 different programs. Starting on April 2022, we sent an email with a web link to the participating consent form and an anonymous Qualtrics survey via the university email to recruit participants. Only the survey responses submitted with the signed consent were used and analyzed in this study. Participants’ information was de-identified right after the data collection.

Data collection

In this study, graduate students were initially invited to respond to closed-ended questions on demographics (i.e., age, gender, and ethnicity) and two five-point Likert scale questions concerning their financial security before and after the school closure. In the local state, the government announced that all schools were temporarily closed on March 20, 2020. Therefore, we set the date as the threshold in our Likert scale questions. The two five-point Likert scale (With “1” for “Strongly Disagree” to “5 “for “Strongly Agree”) questions are:

1. To what extent do you agree with the following statement? “I had sufficient financial resources to cover my monthly costs. Before the school closure (March 20, 2020).”

2. To what extent do you agree with the following statement? “I had sufficient financial resources to cover my monthly costs. After the school closure (March 20, 2020).”

In addition to the Likert scale questions, an open-ended question was also asked to collect specific comments and information from our participants; the question is: “What are your biggest concerns or worries about COVID?” Data was collected online between April first and May fifth, 2022.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis

The final sample consisted of graduate students (N = 258) who answered all questions examined for this study. First, we conducted a quantitative analysis on the two five-point Likert scale questions using descriptive analysis and sign tests. In the descriptive analysis, we described the overall results of the two questions of the participants, and the results based on participants’ gender, age groups, and tuition funding sources. Then we used the sign test (Snedecor and Cochran, 1989) to explore the difference in the financial security of participants before and after the school closure. Four separate sign test analyses were conducted based on the overall participants, gender, age groups, and tuition funding sources. All the quantitative analyses were conducted on the statistical software Stata 17.

Qualitative analysis

The primary survey question, “What are your biggest concerns or worries about COVID?” was left open-ended due to the exploratory nature of the study to allow participants to express their thoughts and experiences. The participants’ comments were coded by researchers by utilizing a thematic step-by-step analysis approach as part of an inductive technique for data analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). In this study, we were informed by Vaismoradi et al. (2016), who recognized themes as something in the data that has a particular degree of pattern or significance in relation to the research questions. Therefore, two of our researchers conducted the analysis by reading and recording the responses cautiously in order to familiarize themselves with the data. Themes were then extracted while reading and re-reading the responses. After the first set of themes was decided, they were sent to another researcher for confirmation and minor adjustments. Discussions were conducted among researchers to decide the final set of themes. Based on the final set of themes, the researchers classified the content of the responses into main themes and sub-themes after discussing them with other team members and reviewing them to ensure that data from a range of participants sufficiently supported all of the themes. So in this study, we used the responses under the central theme of “financial security,” which included responses from 51 participants for in-depth analysis. All the analyses were conducted by using the software NVivo 12.

Results

Results from both the quantitative and qualitative analyses help to answer our original research questions. In general, these results indicated that COVID-19 had a negative impact on graduate students’ financial security. Quantitative analysis results contain general information about the impact of COVID-19 on graduate students’ financial security and how the impact differed in subgroups. Qualitative analysis results provided us with an in-depth understanding of participants’ financial concerns.

Quantitative analysis results

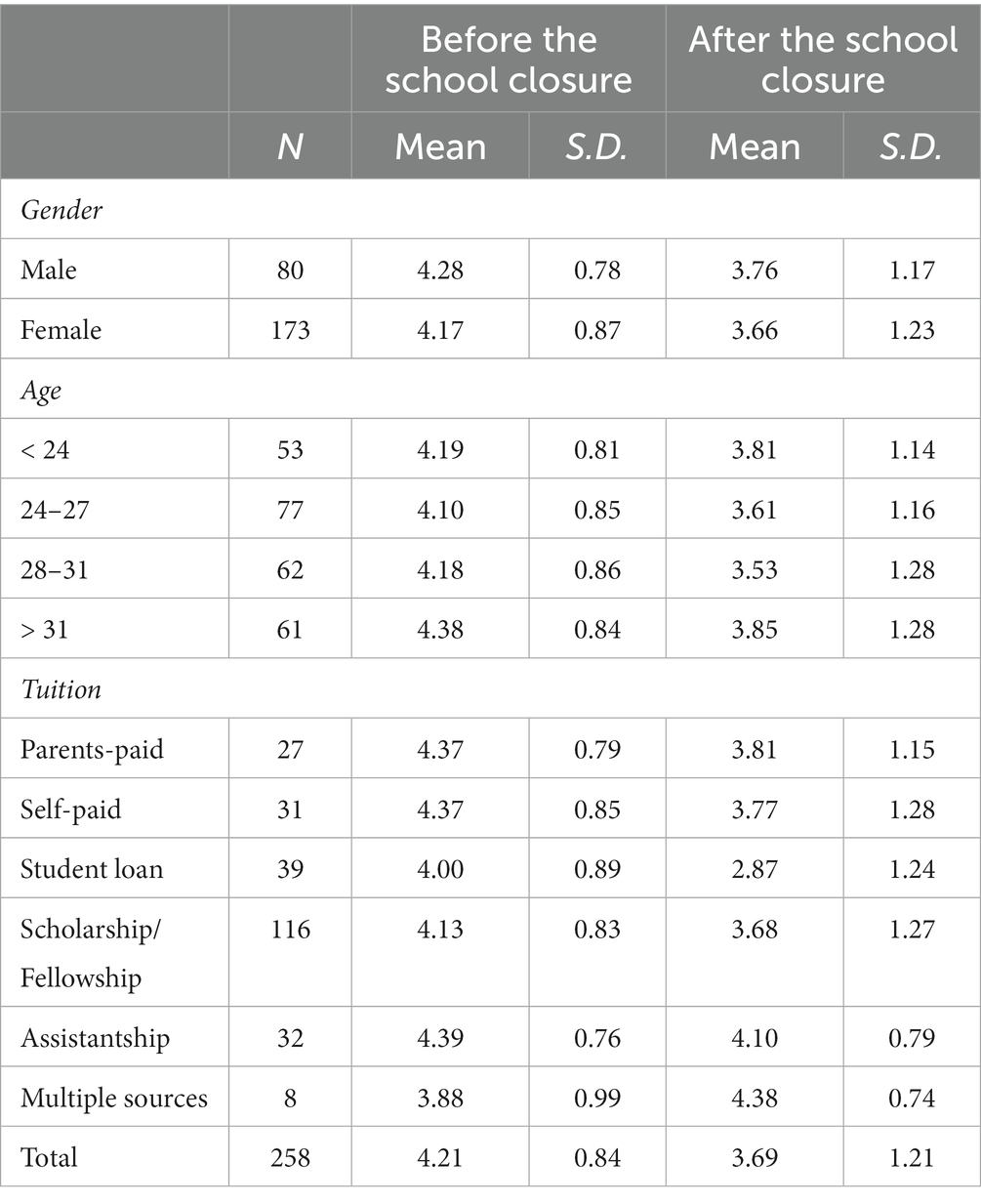

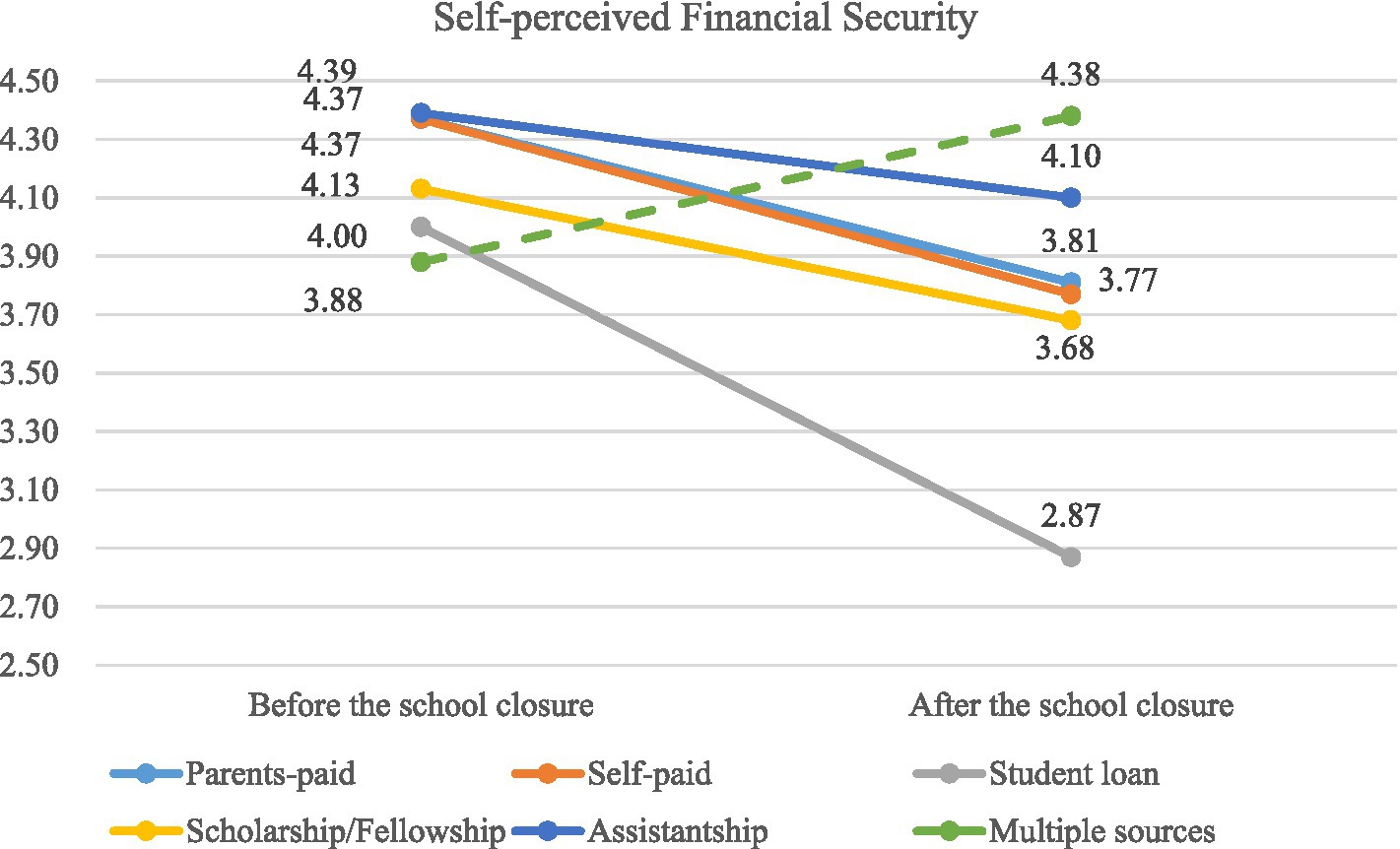

First of all, based on our descriptive analysis results (Table 2), there was a decrease in the mean scores of graduate students in their self-perceived financial security from before (M = 4.21, SD = 0.84) to after the school closure (M = 3.69, SD = 1.21). Female participants scored averagely lower than male students in their self-perceived financial security both before and after the school closure. Looking into different age groups, we found that participants in all age groups perceived less financially secure after the school closure. Participants in the age group 31 or older (N = 61) had the highest average scores before (M = 4.38, SD = 0.84) and after the school closure (M = 3.85, SD = 1.28). In terms of the tuition funding sources, results demonstrated that all sub-groups experienced decreases in their self-perceived financial security after the school closure, except participants with multiple sources of tuition funding. Participants who held student loans (N = 39) had the lowest financial security after the school closure (M = 2.87, SD = 1.24). They also experienced the severest decrease in financial security compared with what they perceived before the school closure (M = 4.00, SD = 0.89). Furthermore, it is also interesting to note that participants who had multiple tuition funding sources had an increase in their self-perceived financial security scores from before (M = 3.88, SD = 0.99) to after the school closure (M = 4.38, SD = 0.74). Considering there were only eight participants in this sub-group, we argue that the results might be subject to potential research bias.

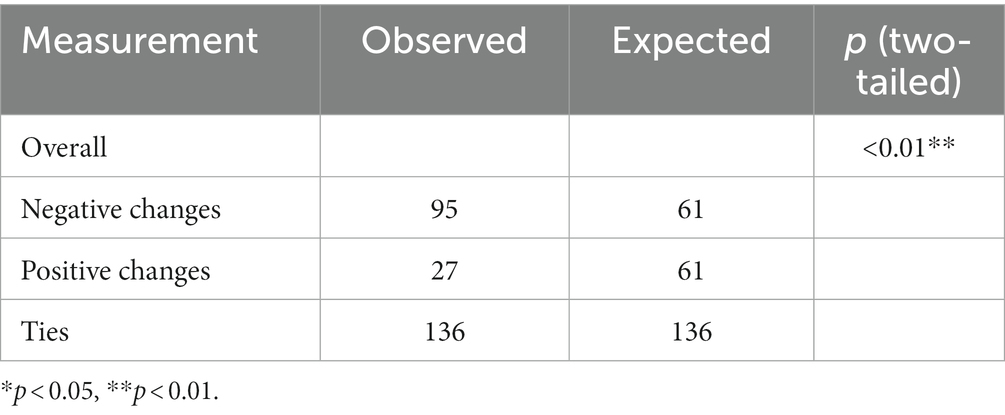

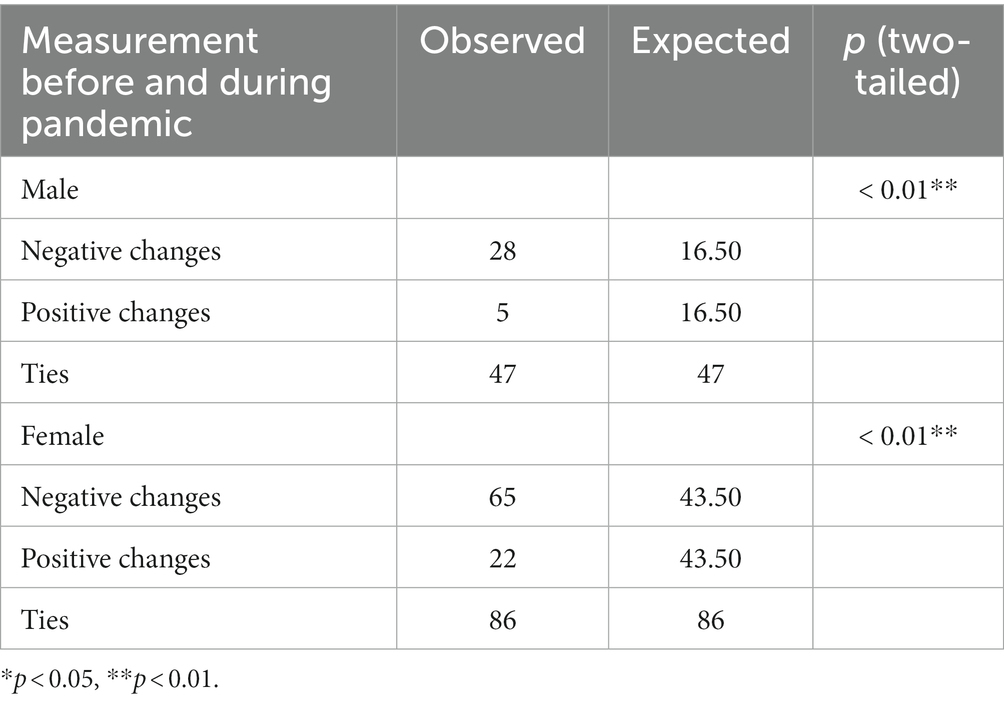

Results of the sign tests echoed what we found from our descriptive analysis and further revealed the impact of COVID-19 on participants’ financial security. The analysis results of all participants indicated that graduate students’ financial security experienced a statistically significant decrease (p < 0.01) from before the school closure to after the school closure (Table 3). By exploring the difference by gender groups, we found that both female and male graduate students’ financial security decreased significantly (p < 0.01) (Table 4). Although female students had lower financial security as measured by the average scores than male students both before and after the school closure, there is no strong evidence to support whether the gender difference was reduced or exacerbated by the pandemic.

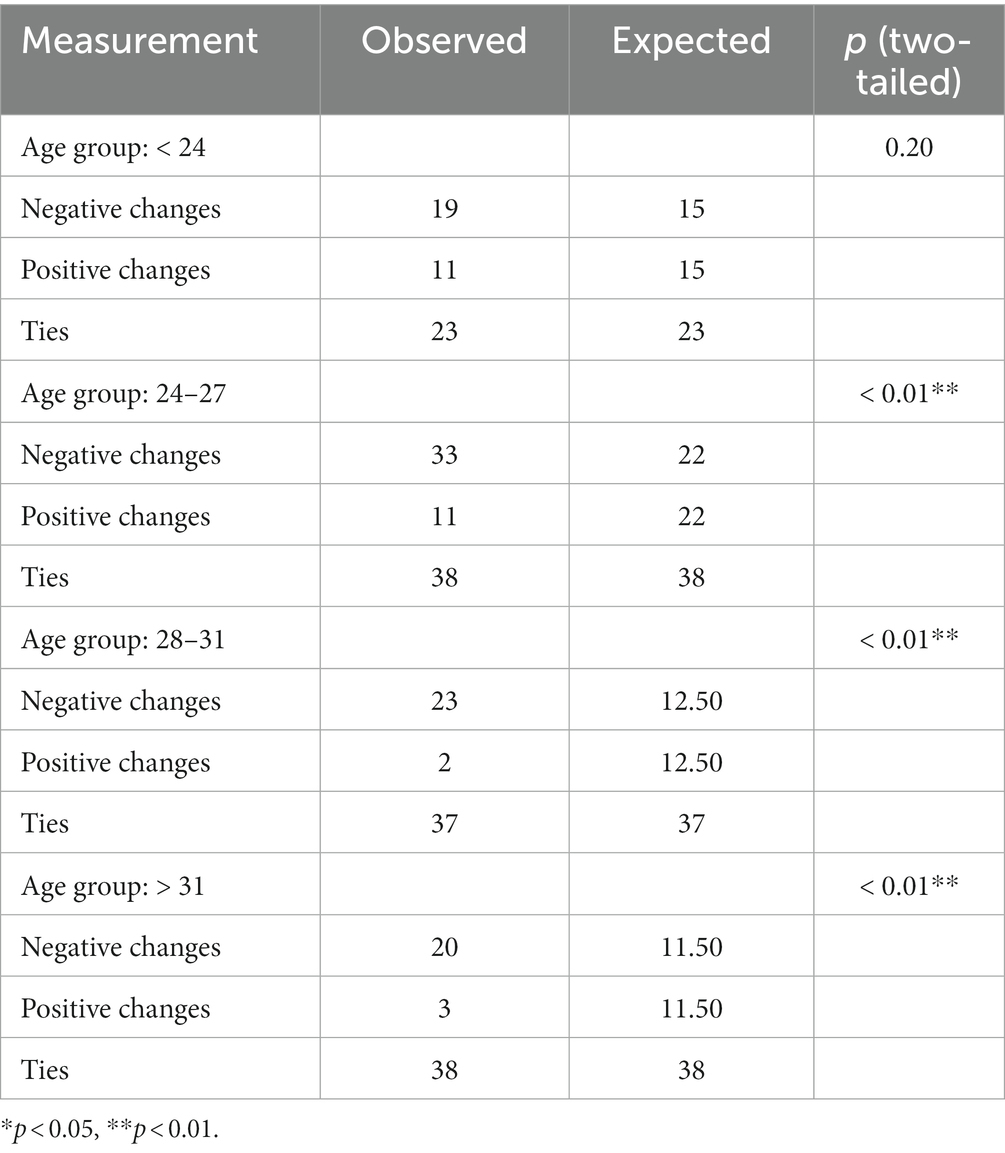

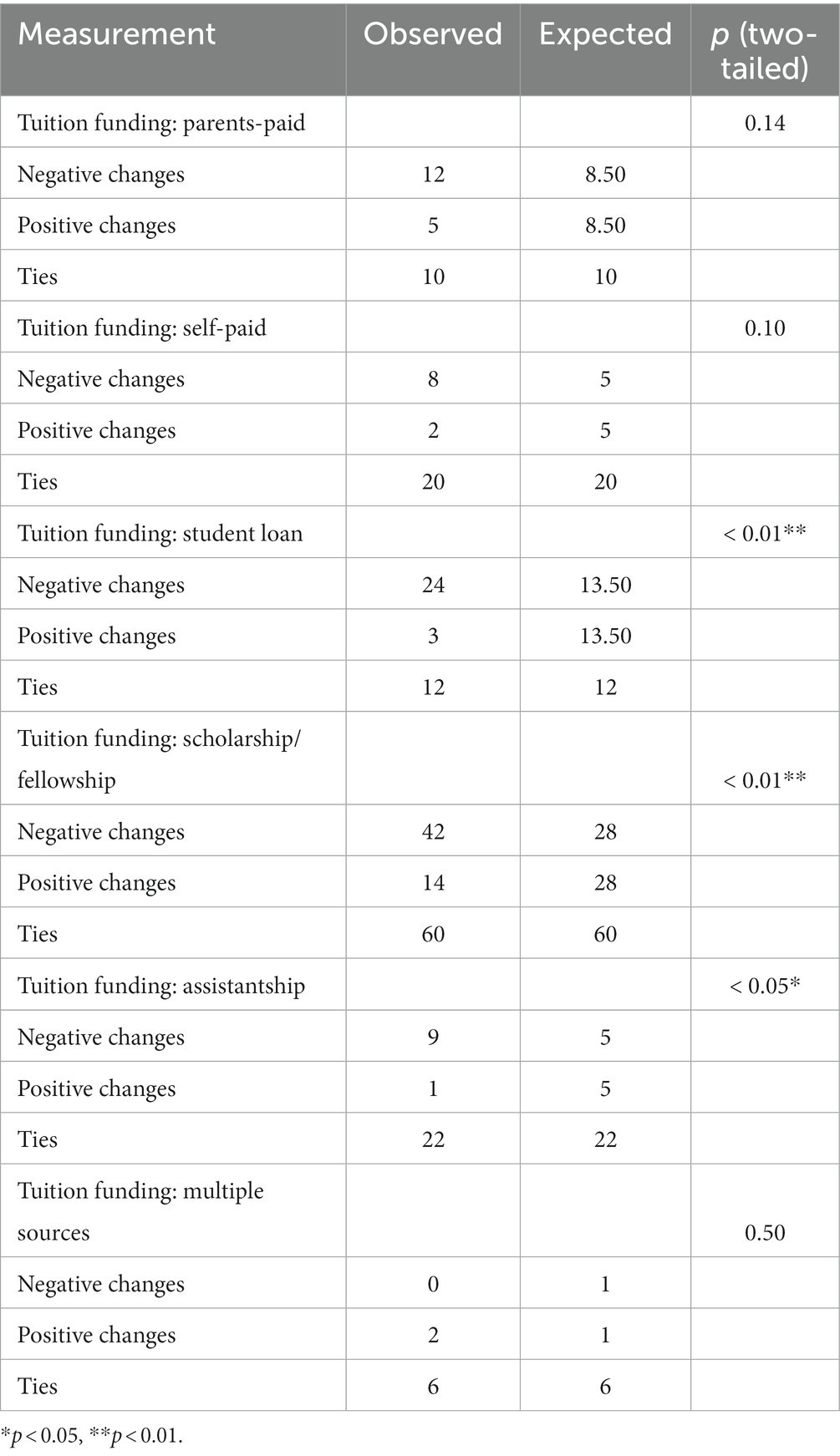

Regarding age groups, graduate students aged 23 or younger did not experience a statistically significant change in their financial security. However, all three other age groups (age 24–27, age 28–31, and age above 31) experienced a statistically significant decrease (p < 0.01) in their self-perceived financial security (Table 5). Among the three age groups, the age group 28–31 experienced the severest decrease in their self-perceived financial security after the school closure. Additionally, students whose tuition was funded by parents, by themselves, or by multiple sources did not experience a statistically significant decrease in their financial security. In contrast, students whose tuition was funded by assistantships (p < 0.01), scholarships/fellowships (p < 0.01), or student loans (p < 0.05) experienced a significant decrease in their financial security (Table 6). The financial security decrease experienced by the graduate students who had tuition funded by student loans was the severest (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The self-perceived financial security of graduate students before and after the school closure by tuition funding source.

Qualitative analysis results

Of the 225 graduate students who gave a response to the question “What is your biggest concern or worry about COVID-19?,” 51 people gave responses that addressed the economic and financial impact of the pandemic. While some of the students (N = 21) gave general responses such as “money,” “financial concerns,” “the economic ramifications,” and “finances,” others gave more detailed responses of how the economic and financial implications impact them personally. Two sub-themes regarding the financial impact were extracted: (1) concerns about inflation; (2) suspension or discontinuation of financial supports.

Concerns about inflation and the economic downturns

Based on our results, 17 (33.33%) participants named inflation their main concern during the pandemic. Graduate students started to observe the disruption to their daily life due to supply chain problems and rising inflation affecting various organizations. During the pandemic, their already limited stipend could not match the price increase, including some basic consumption such as food and housing. As participant 249 responded, “[I am] more worried about inflation and my finances, specifically rising rent and housing crisis.” Participant 179 also mentioned, “I have financial concerns with inflation/gas prices/food shortages.” Others expressed similar but more general concerns about inflation. Some responses are: “I am worried about inflation and stipend not adjusting for it” (Participant 226), “Significant price increase of everything” (Participant 234), and “…I am worried about rising costs…” (Participant 202).

Others expressed general concern about the economy and the impact of shutdowns, with some noting concerns about future job prospects. As participant 296 mentioned, “I am worried about the economic ramifications and finding a job.” The concern about their future career goes beyond the impact of supply chain issues and inflation on their current circumstances. It affects their prospects as economic downturns come with fewer job options. In the response by participant 300, the concern about her academic career was specifically expressed:

I am extremely worried about long-COVID and the potential effects on my career. I am already 40 years old, so it will potentially be more difficult to keep up with young people out in the field. Long-COVID will make that so much more difficult in a field with significant fieldwork.

The response reflected the interactive effect of age and the pandemic on graduate students’ attitudes toward their future careers. The participant specifically expressed concern about competing with younger colleagues in the job market, given the economic downturn the pandemic caused. Participant 300’s response also highlighted the relationship between COVID-19 impact and research areas: those graduate students who conducted more field works in their research activities were more vulnerable to the pandemic impact. Mandatory public health initiatives such as physical distancing heavily disrupted their research works.

In addition, some international students mentioned extra problems the pandemic caused in their financial condition. International students confronted work-hour restrictions made by the local government and were not eligible for many state or federal benefits. The pandemic also restricted them from seeking help from their families. Participant 323 explained: “As an international student? Visa, finances, graduation deadlines, and travel restrictions, to name a few.” Participant 118 also noted, “I cannot return to my home country to stay with my family.”

Suspension or discontinuation of financial supports

In addition to the concerns about inflation and general economic downturns, the suspension or discontinuation of financial support is the other main concern expressed by graduate students. Since many graduate students work hourly, if they do not have an assistantship, this can seriously hamper their academic progress and financial situation. Additionally, their financial assistance could be terminated due to the research institute’s budgetary restrictions, leaving their tuition and other daily expenses uncovered. Among the 30 participants (58.82%) who expressed the concern, 12 of them (40%) mentioned the impact of COVID-19 on their assistantship, as participant 168 responded:

I experienced legitimate delays to my research due to COVID (not being able to collect samples, lab supply shortages). The college and the department have done nothing to help me feel supported. My guaranteed teaching assistantship and tuition and fees payment ends this semester. I have no idea how I will get a stipend in the fall, finish my dissertation, and find a way to pay for tuition and fees on my own.

Other graduate students shared similar concerns as they felt the department or faculty members did not address the problems or issues graduate students had during the pandemic properly: “My biggest concern is the lack of genuine empathy & willingness to fully address the effects of COVID-19 on graduate student cohorts by graduate faculty in their respective departments” (Participant 096); “I feel very disconnected from the university with faculty as well with student organizations” (Participant 043); and

My biggest concerns are: long-term, negative health (physical and mental) effects for individuals and communities; societal and university push to “pre-pandemic times” (despite all of the life, health, etc. changes that have occurred); lack of understanding and accommodations from faculty, staff, and employers. (Participant 021)

These responses reflected the disconnections between graduate students and faculty members during the pandemic. The lack of communication during the pandemic highly restricted students’ access to support from the university or their departments. This was especially the case for those who were having their graduate education alone, away from their families. Participant 047 mentioned in her response:

I came to the university in Fall 2020 and felt like I had no one and nothing to support me. Professors were still acting like there wasn't a massive blanket of doom hanging over us. I was alone for all of my first year and had an emergency that I couldn't contact anyone in town about because I knew no one close enough. I was depressed, I was anxious, everything felt isolated.

Furthermore, some graduate students who could not complete their work due to illness expressed that their learning or research was disrupted. Some of them even decided to withdraw from the university for a semester since they could not manage both their schoolwork and assistantship, as participant 133 explained:

Catching COVID and missing classes or work to a point that is disruptive to my learning. I had COVID-19 in the beginning of February and it impacted my job (deducted pay) and studies, I am having to withdraw this semester due to being out/hospitalized.

Other than the disruption COVID-19 caused on their education progress, the expense of medical care was an extra burden on their already limited financial resources. Some graduate students mentioned that they could not even afford their medical costs and hospitality fee: “The cost of medicine is the biggest concern of me” (Participant 025). “I get severely ill that I need to visit the hospital and not being able to afford such a stay” (Participant 266).

Our qualitative analysis of the responses of participants reflected and further elaborated our quantitative analysis results. Based on the results, graduate students perceived inflation and economic downturns, and the suspension or discontinuation of financial support as the main financial issues they had during the pandemic. They expressed their concerns about the increased daily expenses and the worries about their future career due to the economic downturn caused by the pandemic. Furthermore, many graduate students expressed that the support and accommodation they received from faculty advisors, departments, and the university were very limited. For those graduate students who were infected by COVID-19 or had physical health problems, their work was highly disrupted, and the cost of medical care added an extra financial burden on them.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on graduate students’ financial security and explored the underlying patterns of graduate students’ financial conditions throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous studies examining the effect of the pandemic focused mainly on the educational and emotional impact (e.g., Bal et al., 2020; Kee, 2021). Financial security, crucial for post-secondary students’ academic success and mental well-being (e.g., Gururaj et al., 2010; Cadaret and Bennett, 2019), has not been fully explored. By gathering data from a public research university and analyzing 258 graduate students’ survey responses, we found that the COVID-19 pandemic impacted graduate students’ financial security significantly. Furthermore, our analysis of their open ended question responses revealed that the financial hardship experienced by graduate students was caused by various reasons. A discussion of our findings follows.

For the first research question (i.e., is there any impact of COVID-19 on graduate students’ financial security?), based on our sign test results, we found that the participants perceived a significant impact of COVID-19 on their financial security. During the pandemic, they felt less secure in their financial conditions than in the pre-pandemic period. These findings reflected previous studies (e.g., Alsandor and Yilmazli Trout, 2020; Jenei et al., 2020; Tasso et al., 2021) in revealing problems and issues graduate students had during the pandemic. It further supplements the findings by underlining the fundamental role financial security had during the period. Other than the fears and concerns about physical and mental health, graduate students were under pressure to find sufficient financial support. By conducting a thematic analysis of their open-ended question responses, we found that the financial concerns were mainly caused by inflation and the economic downturns, and the suspension or discontinuation of financial support. Echoed with previous studies (Alsandor and Yilmazli Trout, 2020; Jenei et al., 2020; Tasso et al., 2021), which revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic heavily altered the educational circumstance and personal lives of graduate students, this study further found that graduate students’ academic and career progression were severely disrupted. Many of the research projects were suspended, and graduate students’ access to financial or mental support was minimal. Additionally, with COVID-19 impacting the world and with supply chain issues exacerbating inflation issues, financial concerns remained at the forefront of many graduate students, especially those on a fixed income. We also found that for some graduate students who had physical health problems, the cost of medical care was an extra burden on their budgets. Our results also indicated that some graduate students did not feel they were fully and appropriately supported by their departments. In most cases, they must contend with the changes or problems by themselves.

Next, for our second research question (i.e., what are the underlying patterns of graduate students’ financial security during the COVID-19 pandemic?), we explored the patterns of graduate students’ financial security by analyzing different sub-groups, including gender, age, and tuition funding sources. Based on our sign test results, both male and female students experienced a significant decrease in financial security during the pandemic. Female participants scored lower in the average financial security scores than male participants before and after the school closure. Regarding the age groups, we found that graduate students in most age groups, except the age group 23 or younger, had a significant decrease in financial security. The explanation for the results could be that older students are likely to hold more responsibilities in their academic work and their personal lives. This finding reflects Bal et al. (2020) that the COVID-19 pandemic highly impacted graduate students with children as they had to spend time home-schooling their children while their work was neglected. Other than that, our qualitative findings also revealed that the pandemic and the concomitant concerns about future careers intensified the anxiety of graduate students of higher ages, as they worried they might not be able to compete with their younger colleagues in the job market even after the pandemic. However, in a study conducted by Solomou and Constantinidou (2020), it was found that age and the level of anxiety and depression were negatively correlated. People who were aged 29 or younger were more likely to be anxious and depressed during the pandemic. Therefore, we argued that the concerns and issues in financial conditions of graduate students were intertwined not just with their ages but also with their program levels, academic fields, as well as their academic progress. Future research is needed to collect more information about graduate students to perform a more detailed analysis of the effect of age on their financial security and how the effect might be related to their research field, academic progress, or many potential factors.

In addition, we found that graduate students who had their tuition funded by assistantships, scholarships/fellowships, or student loans had a significant decrease in their financial security during the pandemic. These findings reflected previous studies (Jenei et al., 2020; Tsurugano et al., 2021) in that, during the pandemic, graduate students’ access to assistantships or other work opportunities was highly restricted. As revealed by our qualitative findings, most of them experienced reduced or stalled financial support from their assistantships during the pandemic. Even for those who maintained their financial income, the inflation caused by the pandemic further exhausted their income with increased daily expenses. Mirroring the findings of Archuleta et al. (2013) and Xiao et al. (2020), who pointed out that student loan debt is positively associated with financial insecurity, we found that graduate students who had their tuition funded by student loans experienced the severest decrease of financial security during the pandemic. The pandemic exacerbated educational inequity, as students with lower socioeconomic status were especially vulnerable to the COVID-19 impact (Alon et al., 2020; Gould et al., 2020; Institute of Education Sciences, 2021). Extra support should be provided for students who held education loans in the post-pandemic mitigation plans.

Graduate students are crucial for academic and research innovation (Johnson et al., 2020; Laframboise et al., 2023). The construct of academic research is built mainly upon the work persistently provided by them. As Johnson et al. (2020) pointed out, in most research endeavors, graduate students are providing highly skilled works with inexpensive stipends. In contrast to the contributions they have been making, little attention is made to the financial insecurity suffered by graduate students throughout the pandemic. Based on our research findings, financial security is fundamental for graduate students in coping with other issues or problems they confront in their graduate education, such as academic stress and physical and mental health. Reflecting on other COVID-19 impact studies (e.g., Duygun and Şen, 2020; Ryan et al., 2020; Ansorger, 2021), which were also informed by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, we argued that only when the basic needs are fulfilled, can graduate students maximize their endeavors in pursuit of self-actualization, and contributing on academic innovations.

Implications and limitations

Our study findings have various implications for institutions of higher education. First of all, extra financial support and mitigation plans should be made for students (Bolumole, 2020; Jenei et al., 2020; Sahu, 2020). These strategies include but are not limited to direct case support and the extended timeline for tuition or student loan payments. Financial support is especially important for graduate students who rely on meager stipends or student loans as they experienced severest financial hardship during the pandemic. These findings highlight the disparity in classes between those who have extra resources and those who do not, with many in the latter category not faring well during this pandemic. The qualitative results from this study confirm that financial security is a major concern for graduate students, affecting their physical and mental health as well as their ability to pursue their academic goals. Policymakers and university administrators should also pay attention to the graduate student groups that were the most financially impacted to consider future disaster and emergency response plans.

Additionally, financial advice or consultation service should be provided to graduate students to help them manage their financial situations, especially for those who are holding student loans. Students could be advised about how to find available funding sources to support their education, as those with more sources of financial support experienced the slightest decrease in their financial security during the pandemic. The information about financial support should be disseminated efficiently and appropriately to ensure it can be well-acknowledged by those students in need. People considering attending graduate school should take extra precautions to try to set their finances in good condition and to have a rational envision for their future career prior to starting graduate programs.

Furthermore, as Jenei et al. (2020) argue, the COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity for academic communities to slow down and foster an “ethics of care” (Corbera et al., 2020, p. 192). The pandemic could be a catalyst for us to reflect on building a culture of care inside the academia. Based on our study findings, many graduate students expressed that their department did not appropriately address their problems and needs during the pandemic. The findings reflected the disconnections between faculty members and graduate students in some cases. In the post-pandemic period, the reflection on how to shift our cultural norms and build up an environment of caring would be beneficial for the long-term development of the academic community.

The final implication of this study is that more research needs to be conducted looking at graduate students’ financial security. The sparsity of research combined with the results from this study indicates that financial security was a major concern for many graduate students during COVID-19. While researchers and policymakers continue looking at students’ finances, it is important that they consider the varying effects experienced by different groups of students. Additionally, special attention to research should be paid to the under-represented student groups, such as international students and students with education debts, since we revealed from this study that those students confronted many challenges during the pandemic while having limited resources to cope with them.

The generalization of the study findings is subject to several limitations. First of all, this study was conducted in one public research university, and there were potential biases and correlations in the problems and issues participants confronted. Secondly, as the data of this study was mainly collected from graduate students, the scarcity of data or information from the higher institution could potentially restrict the generalization of the findings. Future studies could further explore the research topic by acquiring data from the university, faculties, and administrators for a more comprehensive understanding of the COVID-19 impact on students’ financial security. In addition, as we did not collect our quantitative data based on international or domestic students status, our qualitative findings about international students were subject to research bias. Supplementary questions should be asked to those who identified themselves as international students to further explore the financial challenges and issues they confronted during the pandemic.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Texas A&M University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

FZ and TG-B conceived of the presented idea. MR and FZ developed the theory and performed the quantitative analyses. TG-B and JC performed the qualitative analysis. FZ and TG-B verified the analytical methods. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., and Tertiary, M. (2020), “The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality”, No. w26947, National Bureau of Economic Research

Alsandor, D. J., and Yilmazli Trout, I. (2020). Graduate student well-being: learning and living during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Multidisc. Perspect. High. Educ. 5, 150–155. doi: 10.32674/jimphe.v5i1.2576

Ansorger, J. (2021). An analysis of education reforms and assessment in the core subjects using an adapted maslow's hierarchy: pre and post COVID-19. Educ. Sci. 11:376. doi: 10.3390/educsci11080376

Archuleta, K. L., Dale, A., and Spann, S. M. (2013). College students and financial distress: exploring debt, financial satisfaction, and financial anxiety. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 24, 50–62,

Bal, I. A., Arslan, O., Budhrani, K., Mao, Z., Novak, K., and Muljana, P. S. (2020). The balance of roles: graduate student perspectives during the COVID-19 pandemic. TechTrends 64, 796–798. doi: 10.1007/s11528-020-00534-z

Barton, B. A., and Bulmer, S. M. (2017). Correlates and predictors of depression and anxiety disorders in graduate students. Health Educator 49, 17–26,

Basith, A., Rahman, M. S., and Moseki, U. R. (2021). College students’ academic procrastination during the Covid-19 pandemic: focusing on academic achievement. Jurnal Kajian Bimbingan dan Konseling, 6, 112–120.

Bayham, J., and Fenichel, E. P. (2020). Impact of school closures for COVID-19 on the US health-care workforce and net mortality: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health 5, e271–e278. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30082-7

Bozyiğit, S. (2021). “Evaluation of Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory within the context of COVID-19 pandemic” in Understanding the consumer behaviour during COVID-19 pandemic. ed. M. Gülmez (Ankara: Akademisyen Kitabevi).

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Britt, S. L., Canale, A., Fernatt, F., Stutz, K., and Tibbetts, R. (2015). Financial stress and financial counseling: helping college students. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 26, 172–186. doi: 10.1891/1052-3073.26.2.172

Brownlow, C., Eacersall, D., Nelson, C. W., Parsons-Smith, R. L., and Terry, P. C. (2022). Risks to mental health of higher degree by research (HDR) students during a global pandemic. PLoS One, 17:e0279698.

Cadaret, M. C., and Bennett, S. R. (2019). College students' reported financial stress and its relationship to psychological distress. J. Coll. Couns. 22, 225–239. doi: 10.1002/jocc.12139

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Considerations for school closure. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/considerations-for-school-closure.pdf

Charles, S. T., Karnaze, M. M., and Leslie, F. M. (2022). Positive factors related to graduate student mental health. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 70, 1858–1866. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2020.1841207

Chrikov, I., Soria, K. M., Horgos, B., and Jones-White, D. (2020). Undergraduate and graduate students' mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Corbera, E., Anguelovski, I., Honey-Rosés, J., and Ruiz-Mallén, I. (2020). Academia in the time of COVID-19: towards an ethics of care. Plan. Theory Pract. 21, 191–199. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2020.1757891

Duygun, A., and Şen, E. (2020). Evaluation of consumer purchasing behaviors in the COVID-19 pandemic period in the context of Maslow's hierarchy of needs. PazarlamaTeorisi ve Uygulamaları Dergisi 6, 45–68,

Eisenberg, D., Gollust, S. E., Golberstein, E., and Hefner, J. L. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 77, 534–542. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.4.534

Evans, T. M., Bira, L., Gastelum, J. B., Weiss, L. T., and Vanderford, N. L. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 282–284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4089

Gould, E., Perez, D., and Wilson, V. (2020), “Latinx workers—particularly women—face devastating job losses in the COVID-19 recession”. Economic Policy Institute. Available at: https://www.epi.org/publication/latinx-workers-covid/

Gururaj, S., Heilig, J. V., and Somers, P. (2010). Graduate student persistence: evidence from three decades. J. Stud. Financ. Aid 40, 31–46. doi: 10.55504/0884-9153.1030

Hardré, P. L., Liao, L., Dorri, Y., and Stoesz, M. B. (2019). Modeling American graduate students' perceptions predicting dropout intentions. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 14, 105–132. doi: 10.28945/4161

Hyun, J. K., Quinn, B. C., Madon, T., and Lustig, S. (2006). Graduate student mental health: needs assessment and utilization of counseling services. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 47, 247–266. doi: 10.1353/csd.2006.0030

Institute of Education Sciences . (2021), 2019-20 national postsecondary student aid study (NPSAS:20). Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED613348.pdf

Ipsos Public Affairs . (2017). How America pays for college. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED577456.pdf

Ivankova, N. V., Creswell, J. W., and Stick, S. L. (2006). Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Methods 18, 3–20. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05282260

Jenei, K., Cassidy-Matthews, C., Virk, P., Lulie, B., and Closson, K. (2020). Challenges and opportunities for graduate students in public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Public Health 111, 408–409. doi: 10.17269/2Fs41997-020-00369-4

Johnson, R.L., Coleman, R.A., Batten, N.H., Hallsworth, D., and Spencer, E.E. (2020), The Quiet Crisis of PhDs and COVID-19: reaching the financial tipping point.

Kee, C. E. (2021). The impact of COVID-19: graduate students' emotional and psychological experiences. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 31, 476–488. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2020.1855285

Kuhfeld, M., Soland, J., Tarasawa, B., Johnson, A., Ruzek, E., and Liu, J. (2020). Projecting the potential impact of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement. Educ. Res., 49, 549–565.

Laframboise, S. J., Bailey, T., Dang, A. T., Rose, M., Zhou, Z., Berg, M. D., et al. (2023). Analysis of financial challenges faced by graduate students in Canada. Biochem. Cell Biol. 101, 326–360. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2023-0021

Litalien, D., and Guay, F. (2015). Dropout intentions in PhD studies: A comprehensive model based on interpersonal relationships and motivational resources. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 218–231.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). The instinctoid nature of basic needs. J. Pers. 22, 326–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1954.tb01136.x

Mutch, C., and Peung, S. (2021). 'Maslow before Bloom': implementing a caring pedagogy during COVID-19. N. Z. J. Teach. Work 18, 69–90. doi: 10.24135/teacherswork.v18i2.334

National Center for Education Statistics (2023). Postbaccalaureate Enrollment. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/chb/postbaccalaureate-enrollment

Oswalt, S. B., and Riddock, C. C. (2007). What to do about being overwhelmed: graduate students, stress and university services. Coll. Stud. Aff. J. 27, 24–44,

Pfefferbaum, B. (2021). Challenges for child mental health raised by school closure and home confinement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 23, 65–69. doi: 10.1007/s11920-021-01279-z

Ryan, B. J., Coppola, D., Canyon, D. V., Brickhouse, M., and Swienton, R. (2020). COVID-19 community stabilization and sustainability framework: an integration of the Maslow hierarchy of needs and social determinants of health. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 14, 623–629. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.109

Sahu, P. (2020). Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus 12, e7541. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7541

Snedecor, G. W., and Cochran, W. G. (1989). Statistical methods. 8th Edn. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press.

Solomou, I., and Constantinidou, F. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and compliance with precautionary measures: age and sex matter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:4924. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17144924

Strayhorn, T. L. (2010). Money matters: the influence of financial factors on graduate student persistence. J. Stud. Finan. Aid 40, 4–25. doi: 10.55504/0884-9153.1022

Subedi, D. (2016). Explanatory sequential mixed method design as the third research community of knowledge claim. Am. J. Educ. Res. 4, 570–577,

Sverdlik, A., Hall, N. C., McAlpine, L., and Hubbard, K. (2018). The PhD experience: a review of the factors influencing doctoral students' completion, achievement, and well-being. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 13, 361–388. doi: 10.28945/4113

Tasso, A. F., Hisli Sahin, N., and San Roman, G. J. (2021). COVID-19 disruption on college students: academic and socioemotional implications. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 13, 9–15. doi: 10.1037/tra0000996

Trout, I. Y., and Alsandor, D. J. (2020). Graduate student well-being: learning and living in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Multidisc. Perspect. High. Educ. 5, 150–155. doi: 10.32674/jimphe.v5i1.2576

Tsurugano, S., Nishikitani, M., Inoue, M., and Yano, E. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on working students: results from the labour force survey and the student lifestyle survey. J. Occup. Health 63:e12209. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12209

Vaismoradi, M., Jones, J., Turunen, H., and Snelgrove, S. (2016). Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 6, 100–110. doi: 10.5430/jnep.v6n5p100

Vakkai, R. J. Y., Harris, K., Chaplin, K. S., Crabbe, J. J., and Reynolds, M. (2020). Sociocultural factors that impact the health status, quality of life, and academic achievement of international graduate students: a literature review. J. Int. Stud. 10, 758–775. doi: 10.32674/jis.v10i2.1222

Viner, R. M., Russell, S. J., Croker, H., Packer, J., Ward, J., Stansfield, C., et al. (2020). School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 4, 397–404. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30095-X

Walsh, B. A., Woodliff, T. A., Lucero, J., Harvey, S., Burnham, M. M., Bowser, T. L., et al. (2021). Historically underrepresented graduate Students' experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fam. Relat. 70, 955–972. doi: 10.1111/fare.12574

Wang, X., Hegde, S., Son, C., Keller, B., Smith, A., and Sasangohar, F. (2020). Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 22:e22817. doi: 10.2196/22817

Wollast, R., Boudrenghien, G., Van der Linden, N., Galand, B., Roland, N., Devos, C., et al. (2018). Who are the doctoral students who drop out? Factors associated with the rate of doctoral degree completion in universities. Int. J. High. Educ. 7, 143–156. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v7n4p143

Xiao, J. J., Porto, N., and Mason, I. M. (2020). Financial capability of student loan holders who are college students, graduates, or dropouts. J. Consum. Aff. 54, –1401. doi: 10.1111/joca.12336

Keywords: graduate students, COVID-19, school closure, financial security, mixed methods

Citation: Zhen F, Graves-Boswell T, Rugh MS and Clough JM (2024) “I have no idea how I will get a stipend”: the impact of COVID-19 on graduate students’ financial security. Front. Educ. 9:1235291. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1235291

Edited by:

Alberto Amaral, Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Agency (A3ES), PortugalReviewed by:

Maria José Sá, University of Aveiro, PortugalAntónio Magalhães, University of Porto, Portugal

Copyright © 2024 Zhen, Graves-Boswell, Rugh and Clough. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fubiao Zhen, emhlbmZ1Ymlhb0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Fubiao Zhen

Fubiao Zhen Taylor Graves-Boswell2,3

Taylor Graves-Boswell2,3 Michael S. Rugh

Michael S. Rugh Jake M. Clough

Jake M. Clough