- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Stanford School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA, United States

- 2Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States

- 3Global Pediatrics Program and Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 4International Research Center of Excellence, Institute of Human Virology Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria

- 5Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Coast School of Medical Sciences, Cape Coast, Ghana

Introduction: The movement to decolonize global health encompasses efforts to dismantle historically inequitable structures and processes in global health research, education, and practice. However, despite increasing literature on the decolonization of global health, gaps between action and knowledge exist in assessments of knowledge production. In this Perspective, we will outline potential biases in current approaches to assessing knowledge production and propose a systems-focused guide to improve the interrogation of knowledge production in this field.

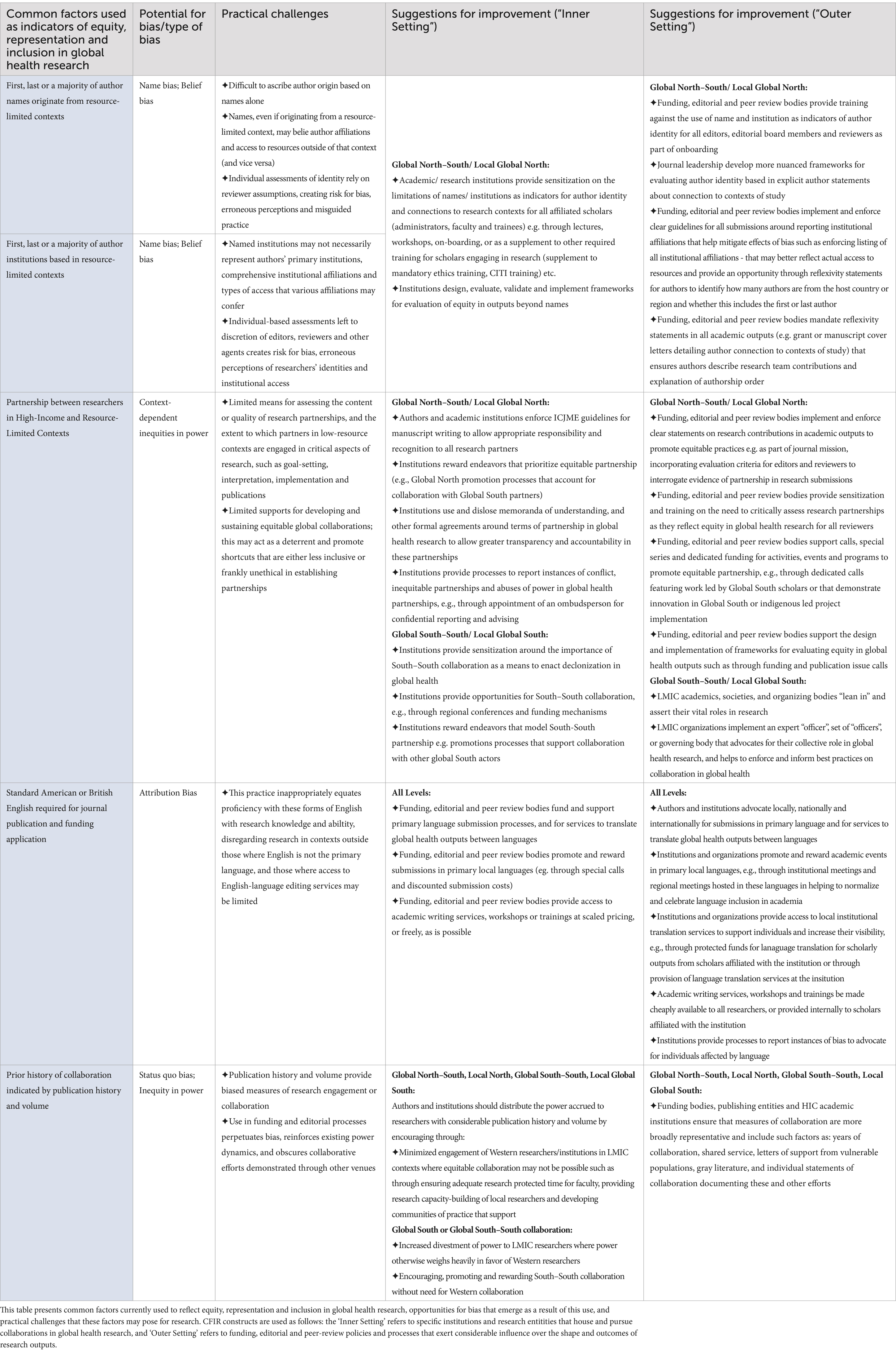

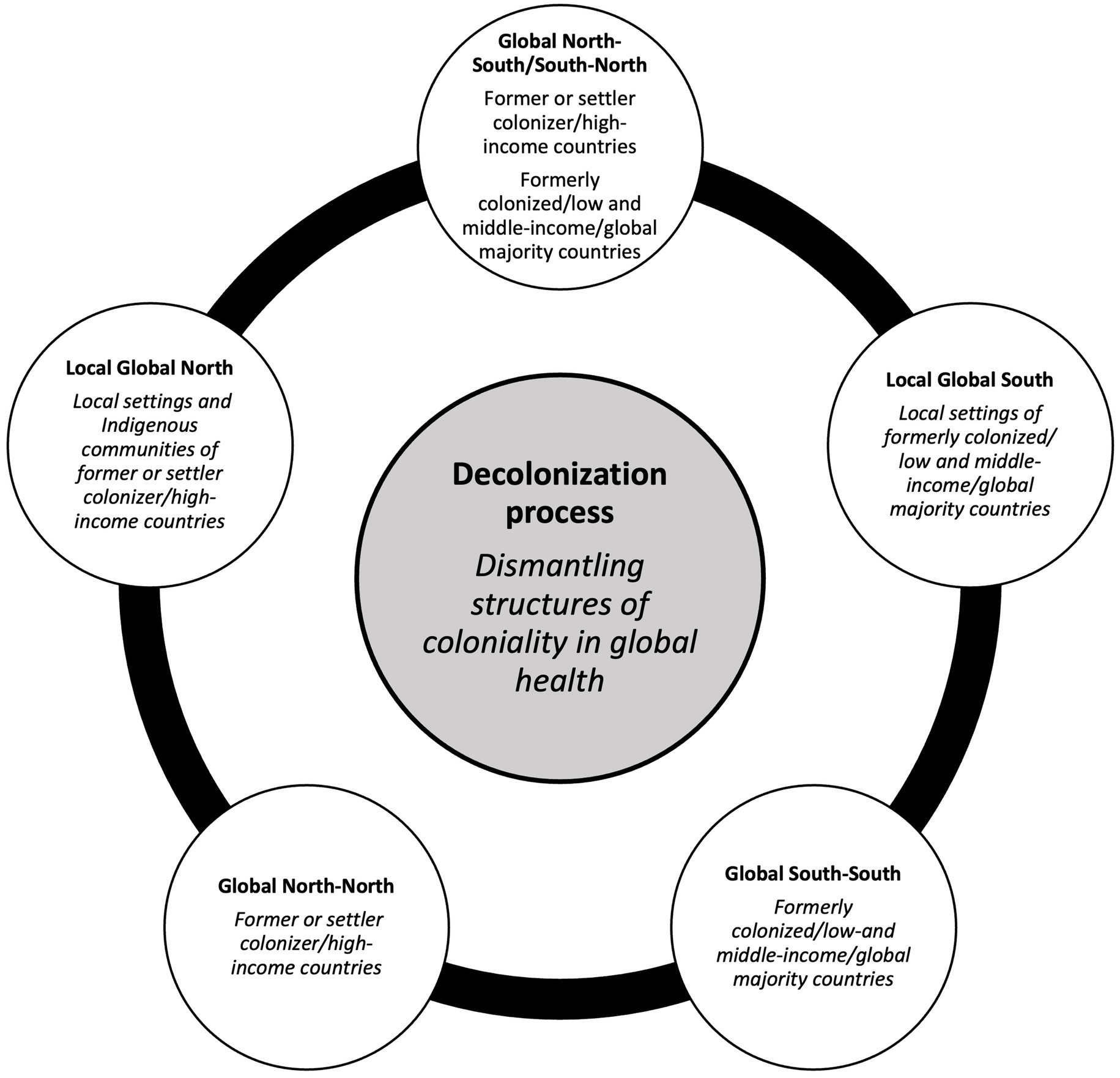

Methods: We leverage the “Inner Setting” and “Outer Setting” domains of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), a well-established, commonly-used implementation science framework to critically assess the status quo of decolonization and to develop criteria to help guide decolonization efforts in academic contexts. We defined the Inner Setting as academic and research institutions leading and participating in global health research collaborations, and the Outer Setting as the funding, editorial, and peer review policies and practices that influence knowledge production in global health. Research institutions in the Inner organizational domain continually interact with the Outer policy domains. We categorize the levels at which decolonization may occur and where action should be focused as follows: (1) North–South, (2) South–South, (3) Local South, and (4) Local North. Using CFIR domains and the levels of action for decolonization, we propose a multi-level guide to improve on the standardization, granularity, and accuracy of decolonization assessments in global health research.

Conclusion and expected impact: The proposed guide is informed by our global health research expertise and experiences as African scientists with extensive exposure in both global North and global South research contexts. We expect that the proposed guide will help to identify and address the biases identified and will lead to better knowledge-driven action in the process of decolonizing global health research.

Introduction

The movement to decolonize global health encompasses efforts to dismantle historically inequitable structures and processes in global health education, research, and practice. Racism, white supremacy, and the marginalization of global majority populations through historical structures of oppression such as colonialism and neocolonialism, are entrenched in global health in its current form. As a result, global health ontology (the realities and study of being) and epistemology (the creation and study of knowledge) from the global South have been at the periphery (Abimbola, 2023). The decolonization movement aims to confront global health’s colonial and white supremacist roots; undo the idea that progress in global health is unidirectional, from the “donor” in the global North to the “beneficiary” in the global South (Abimbola, 2019; Abimbola et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2022); and extend influence over global health beyond Western institutions to global majority settings (Erondu et al., 2020; Pai, 2020). Efforts to decolonize global health have become increasingly prominent since the term was used in seminal articles and catalyzed by the “#decolonizeglobalhealth” social media campaign starting in 2019 (Guinto, 2019). According to Waziyatawin and Yellow (2005), “[d]ecolonization is the intelligent, calculated, and active resistance to the forces of colonialism that perpetuate the subjugation and/or exploitation of our mind, bodies, and lands…” and extends to diet and other aspects of health (Waziyatawin and Yellow, 2005). Publication of field-shifting papers by authors in both the global North and South have lent further strength and evidence to these efforts (Boum Ii et al., 2018; Iyer, 2018; The Lancet Global Health, 2018, 2021; Abimbola and Pai, 2020; Erondu et al., 2020; Pai, 2020; Araújo et al., 2021; Daffé et al., 2021; Pant et al., 2022).

Research has been a particular focus of the decolonization movement’s scrutiny, reflecting its foundational role in creating global health knowledge and shaping global health ethics, education, policy, and practice. Understanding the assumptions and values that underlie research is a part of the decolonization process (Smith, 2012). As is the case in other disciplines, research endeavors in global health require a stepwise series of tasks. These include prioritizing and developing consensus on research topics, identifying collaborators, securing funding, conducting research, and disseminating findings through avenues such as conference presentations and journal publications.

This stepwise process provides ample opportunity to adopt decolonized approaches. Despite an abundance of literature on the need for decolonization, only nascent guidance has been published on specific steps toward achieving this goal (Walters and Simoni, 2009; Khan et al., 2021; Narasimhan and Chandanabhumma, 2021). This allows for bias (systematic inequity) and ambiguity (systematic uncertainty) in actualizing decolonization and perpetuates the status quo. For example, editors may use author names and institutional affiliations to assess researchers’ connections to study settings, leading to misattribution of ethnicity or location due to name and belief biases (Farnbach et al., 2017; Boum Ii et al., 2018; Babyar, 2019; Hudson et al., 2020; The Lancet Global Health, 2021; Patterson et al., 2022). It may also lead to arbitrary quotas for how many authors should be from a specific place or group, rather than addressing underlying practices that would further true inclusivity and belonging. This situation occurs alongside a push to practice vigilance and reflexivity (statements of inclusivity and author identity) in decolonization to ensure that it moves beyond rhetoric and that its outcomes are structural and (Rennie et al., 1997; Yousefi-Nooraie et al., 2006; Matías-Guiu and García-Ramos, 2011; Chersich et al., 2016; Hedt-Gauthier et al., 2019; Mbaye et al., 2019; Rees et al., 2021, 2023; Akudinobi and Kilmarx, 2022).

In recent years, bright spots in academia that have emerged as counters to systemic inequity from colonization include the following: in 2010, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded foreign institutions specifically located in African countries through the Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI) (Fogarty International Center, 2020a). Outcomes included more than 1,000 manuscripts and more than 500 grant and fellowship applications, with a success rate of 34% or 187 awards (Fogarty International Center, 2020b). In 2021, the PLOS GPH journal was launched with the express mission detailed by editors Kyobutungi, Pai and Robinson as having a focus on inclusion and “amplifying the voices of underrepresented and historically excluded communities.” They committed to being “deliberate and intentional about equity, diversity, and inclusion at all levels–editors, editorial boards, peer reviewers and authors–” to broaden the range and diversity of perspectives. As a result, they recruited a majority of section editors that were women, and Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC); half of the section editors are based in the Global South (Kyobutungi et al., 2021). Other global journal efforts include waiving of publication fees for authors affiliated with LMIC-based institutions and providing editing services in some cases. Additionally, the Fogarty Emerging Leader Award was launched a few years ago and is sequestered for LMIC candidates; applicants are provided with “research support and protected time, (and must hold) an academic junior faculty position or research scientist appointment at an LMIC academic or research institution.” These initiatives and their subsequent impacts have been noteworthy, however, the incidence of such examples among funding bodies, journals and other academic gatekeepers is rare. To facilitate structural change, we propose the development and application of frameworks for assessing measurable indicators in the decolonization process.

In this perspective, we highlight measures to guide standardized assessments of systems-level decolonization in global health research. These measures are informed by our personal experiences as African scientists, common observations in the global health field, and the nascent literature around decolonization in research. We make particular note of the challenges and potential biases that may arise from using some of the current approaches to assessing decolonization in global health research, and discuss how our proposed measures may assist authors, research institutions, publishing entities, and funding bodies to avoid these biases.

Conceptualization of the guide

We describe potentially problematic measures of equity, representation, and inclusion currently used to assess decolonization in global health research (Table 1) and the risk of bias associated with each, drawing from key literature where available. For our assessment, we used a well-established implementation science framework, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Means et al., 2020; CFIR, 2022; Damschroder et al., 2022) The CFIR, and implementation science overall, provide a systematic approach to evaluate programs, processes or interventions – a “thing” – with a given purpose. The CFIR framework consists of five different domains and sub-domain constructs established as core to successful and sustainable implementation strategies. In other words, if each of the five domains are optimized, then the thing, or intervention, will have better short-term uptake and long-term achievement of its purpose. On the other hand, if there is failure to optimize a domain, there will likely be challenges during implementation of the intervention and in achieving the desired implementation outcomes. CFIR further delineates each of the five domains with factors, or determinants, that contribute to the collective success of that domain. The five domains are: “Intervention Characteristics” recognizing that “key attributes of interventions influence the success of implementation (Greenhalgh et al., 2004; Rabin et al., 2008); “Outer Setting” (which includes “external strategies to spread interventions including policy and regulations, external mandates, recommendations and guidelines”); “Inner Setting” (which includes implementation climate or “the absorptive capacity for change, shared receptivity of involved individuals to an intervention and the extent to which use of that intervention will be rewarded, supported, and expected…”); “Characteristics of Individuals” (exploring the fact that “organizations are made up of individuals and, ultimately, that the actions and behaviors of individuals. Affects implementation…”), and “Process” (which includes how engagement is conducted or how “attracting and involving appropriate individuals in the implementation and use of the intervention” occurs; this is recommended through a combined strategy of social marketing, education, role modeling, training, and other similar activities).

For our assessment, we interrogated the “Inner Setting” and “Outer Setting” domains of current systems and approaches to tackling decolonization in global health research, in order to propose alternative measures with lower risks of bias. For this paper, we define the Inner Setting as academic and research institutions leading and participating in global health research collaborations. Constructs that apply to this setting include the structure, culture, and communications within these institutions and their readiness to implement changes. The Outer Setting represents funding, editorial, and peer review policies, procedures and practices that exert influence on knowledge production in global health. We used the CFIR to develop a new guide (shown in Table 1) that others can use to actualize and assess decolonization in the academic context.

Domains of action in the process of decolonization

We adopt Sharma and Sam-Agudu’s categorization of the domains in which decolonization in global health research may occur, and where our proposed measures of assessment might be deployed (see Figure 1), (1) the global North–South interface (research collaborations between institutions in high income, former colonizing countries,- and low-middle income formerly colonized countries- e.g. Portugal and Brazil); (2) the global South–South interface (research collaborations between two institutions in low-and-middle income or formerly colonized countries, e.g., Nigeria and Kenya); (3) the local global South setting (research conducted in-country by one or more institutions within a formerly colonized country, e.g., India); and (4) the local global North setting (research conducted in-country in a high-income or settler-colonized country, e.g., Canada; Sharma and Sam-Agudu, 2023).

Figure 1. Domains of action for decolonization in global health research. The global domains for decolonization action are presented as a non-hierarchical circular continuum within which the different domains are interconnected. Adapted from Sharma and Sam-Agudu (2023).

Global North–South/global South–North

This point of action is where the bulk of decolonization efforts are planned for, or occur, because of the history and legacy of colonization of global South states by global North states, and the prevailing North–South inequity in global health research resources and knowledge production. Actors in this domain include individual researchers, and academic and health institutions in the global North, and their global South counterparts. Decolonization actions include “lean out” actions that require global North actors to redistribute resources and power, such as sharing or yielding leadership and enabling global South participation and leadership in authorship, as well as prioritizing the research needs of global South institutions and communities (Lawrence and Hirsch, 2020; Abouzeid et al., 2022). Global South actors also have responsibilities in decolonization at this interface, which include “leaning in” to establish or strengthen ownership, asserting leadership, self-education to recognize, denounce, and counteract coloniality, and making substantial and sustained local investments in global health research (Oti and Ncayiyana, 2021; Sharma and Sam-Agudu, 2023). To establish a lasting culture of decolonial action, both sets of actors should also train their students to identify and address colonialism in global health (Keynejad et al., 2023; Perkins et al., 2023), support critical evaluations of equity in research collaborations, and make functional provisions for reporting and resolving issues around equity in global health partnerships. The measures we propose in this article can serve as a resource for establishing a culture of decolonial action.

Global South–South

This point of action involves entities in low- and middle-income countries in the global South and focuses on interactions between settings that share similarities in geography, colonial history, climate/climate changes environment, social mores, and/or disease epidemiology. Examples of South–South research partnerships where decolonization actions and assessments may occur include collaborative projects on emergency and disaster medicine in conflict-involved areas in the Horn of Africa, tuberculosis in South Asian countries, or the effect of climate change on Indigenous people in South American countries. Decolonization actions here include expanding opportunities for more of such multicounty, cross-regional collaborations. Anti-colonial collaborations and discourse in this domain can motivate and support global South researchers and institutions to assert leadership through collective social and political action, and facilitate the establishment, strengthening and financing of high-quality local research and research institutions. Decolonization actions in this domain would leverage strength and power in numbers and geographical expanse to achieve paradigm shifts in the status quo.

Local global South

Actions at this point concern researchers and institutions within the same global South country. Beyond addressing North–South disparities in global health research, decolonization actions should consider prevailing local disparities (e.g., based on class, ethnicity, indigeneity, or gender) that may create and sustain inequity in global health research leadership and participation. This domain also includes local custodians of Indigenous health knowledge and practice, such as traditional birth attendants and traditional bone healers. This is a particularly important domain for actions to “decolonize the mind,” where local global South actors unlearn the untruths of colonial education and eliminate their internal coloniality (Oti and Ncayiyana, 2021; Sharma and Sam-Agudu, 2023). As recommended for the global South–South, we propose that decolonization actions in this domain involve “leaning in” and rallying social and political support and resources around local knowledge production.

Local global North

While we address decolonization of global health research in the global South, we acknowledge that the global North is not homogenous in resource access and distribution. While much of the global health funding and programmatic infrastructure is centered in the global North, researchers from, and institutions dedicated to Indigenous/minoritized groups have had limited access. For example, in the United States, Canada, Australia, researchers from Indigenous and minoritized groups such as Native American, Black, Latino and Aboriginal people have historically been marginalized or excluded from research leadership, participation and benefits (Hill and Holland, 2021; Laird et al., 2021; Roach and McMillan, 2022; Garba et al., 2023). We acknowledge existing literature on Indigenous decolonization in academia, and recognize the foundational health knowledge and shared experiences of marginalized populations in the global North (Held, 2019; Willows and Blanchet, 2022; Eisenkraft Klein and Shawanda, 2023; Garba et al., 2023; Wispelwey et al., 2023). We build on this work and propose measures for the global North to address local inequities in global health research, particularly those arising from oppression and discrimination from systems of slavery, racism, white supremacy, and settler colonialism.

Global North–North

The North–North interface involves interactions between resource-rich institutions and countries that have contributed to, and/or benefitted from inequities in global health research established or perpetuated by racism, white supremacy, colonization and coloniality in both the global North and the global South. For this domain, we recommend collaborative action by, and between global North institutions to support the measures for decolonization in the North and South domains. As global South entities “lean in,” global North allies in decolonization should also commit to “leaning out” actions that address inequities in global health research. Furthermore, global North entities have an opportunity to collaboratively address inequities in Indigenous individual, institution and community representation, participation and knowledge production in global health research (Held, 2019). However, it is important to note that North–North action must also be informed by Indigenous and other minoritized groups within and across borders (Held, 2019). Proposed actions for decolonizing global health research restorative justice, such as substantial research education and funding opportunities reserved for Indigenous and other minority groups. In this domain, such opportunities should be presented as regional, rather than national initiatives, recognizing geographical commonalities and inequities experienced by the people groups affected by colonialism.

Measures, biases, proposals and actors

Author names and institutions

Author names in manuscripts and grants are routinely used in assessing diversity, inclusion, and equitable study setting (Milkman et al., 2012; Moss-Racusin et al., 2012; Kozlowski et al., 2022). Currently, evaluations based on names are left to the judgment of individual reviewers, without much guidance on how to use author names for these assessments. Names, however, are in themselves complex products of history, and while reflective of certain identities, may not be accurate nor readily associated with all of an individual’s intersecting identities (Kozlowski et al., 2022). The authors have experienced some adverse results of this personally, having received reviewer comments such as “This should be reviewed by a native speaker,” “The authors failed to include adequate representation from the target country,” and “Grant team representation is not reflective of site partners” in cases where the authors were native speakers of English but with foreign names or affiliations, or where the study included authors and team members whose names or affiliations may have not made it immediately apparent that they were from the target countries. Leaving these determinations of identity, then, to the discretion of editors, reviewers, and other agents may not result in accurate conclusions and risks exposing assessments of inclusion and representation to naming and belief biases–the assumption that an author with a name associated with a particular place actually comes from that place.

Using author institutions as indicators is similarly problematic. First, different individuals within the same institution may experience different levels of power and access to resources, some of which may be informed by such factors as seniority, gender, academic rank, race/ethnicity, religion, and other characteristics that may intersect with these (Snow, 2008; Thoits, 2010; Shannon et al., 2019; Batson et al., 2021). As such, an institution’s name or location may not accurately reflect an author’s access to resources. Second, it has become increasingly common for academics to have affiliations at multiple institutions, sometimes in different geographical locations. In turn, it is not uncommon for researchers to list different institutional affiliations for different academic outputs. For example, authors might list affiliations with institutions in low-resource settings where studies were conducted, while maintaining affiliations with institutions in high-resource settings that may provide access to resources not available in the low-resource settings. In situations like this, the primary affiliation tells us precious little about the conditions that shape global health outputs, and, as with author names, editors and reviewers reviewing global health grants and papers have few resources to guide interpretation of author affiliations.

Proposed measures

As an alternative to the above-mentioned approaches, we propose less ambiguous means of considering author relationships to study settings to reduce name and belief biases. These include institutional Inner Setting actions such as mandating training on research bias and solutions such as naming bias, author bias and community-engaged research that could easily augment existing mandated research trainings for all engaged scholars – administrators, faculty, and trainees - (e.g., as a supplement to ethics training, CITI training etc.) already being done. The role for enforcement of completion could be overseen by the same offices ensuring other research trainings are completed prior to engaging in research.

Additionally, explicit acknowledgement of research relationships through reflexivity statements in grant or manuscript cover letters or elsewhere should be done (Saleh et al., 2022). A reflexivity statement could include, for example, how many authors are from the host country or region and whether this includes the first or last author, without giving specific names or affiliations. Standardized means for reporting and ordering author affiliations, e.g., joint or alternating first and/or senior authorships, and multiple Principal Investigator mechanisms for global North–South projects are other means (Sam-Agudu et al., 2016). Funding, editorial, and peer review Outer Setting policies should include requiring the Inner Setting actions as standards for grant or manuscript submissions. In addition, Global South–specific recommendations include asserting their vital roles in research and establishing policy to requiring trained officers to review grant and manuscript submissions in which they are participating for equity. These actions can provide more accurate and nuanced reflections on positionality, connection, and representation in research (Table 1).

In the further future, a global body such as the World Health Organization could facilitate the enforcement and application of such guidelines by governments, research institutions and scientists in member nations. It would also be informative to conduct studies to examine how many journals and funding agencies have implemented the policies and the degree to which they are enforced.

Power dynamics in research partnerships

Collaboration is a key feature of global health work, bringing together perspectives, skills, and resources from a variety of contexts to generate research outputs. However, such collaborations can be influenced by context-dependent inequities in power, where “systems of inequality, such as sexism, racism and ableism, interact with each other to produce complex patterns of privilege and oppression” (Nixon, 2019). These inequities shape differences in resource access experienced by different collaborators; influence distributions of labor, recognition, and reward throughout the research process; and may inform how research is interpreted and valued.

The consequences of this inequity are demonstrated in the disproportionately large influence that global North partners have in global health research leadership, e.g., recognized PI and co-investigator roles rather than non-acknowledgement of key global South or Indigenous/minoritized contributors; decision-making in projects, institutional, national, regional and global agendas; publication representation; invitations and application to present at conferences and other meetings, selection for merit awards, and funding, among others (Boum Ii et al., 2018; Mbaye et al., 2019; Eichbaum et al., 2021). Albeit improving, even this limited representation has come with substantial compromise on the part of global South researchers, who may be cursorily added as “partners” and middle authors on research papers and presentations to satisfy requirements for global South “representation.” Global South researchers may experience particularly high pressure to make these compromises in order to maintain relationships with the global North collaborators, who may be important sources of prestige, funding, opportunities for career advancement, and other benefits.

Proposed measures

To address issues of power in partnerships, we propose the use and disclosure of memoranda of understanding (MOU) between collaborating groups, to establish each partner’s role and scope of work at the earliest possible opportunity and limit the extent to which these roles are influenced by inequities in power (Boum Ii et al., 2018; Abimbola et al., 2021). Gatekeepers such as journal editors and grant funders could play a role in enforcing an MOU, for example by comparing the author contributions listed in a submission to those in the MOU and asking the authors to explain any discrepancies. Having an institutional point person, such as a chair or dean of global relationship (or other ombudsperson), might also help, similar to the role of DEI specialists in the United States (Parker, 2020; Davenport et al., 2022). Additionally, funding, editorial and peer review bodies have a key stake in implementing and enforcing equitable partnerships in research outputs (see Table 1); this might be done through implementing clear statements on inclusion as part of journal mission and objectives, incorporating evaluation criteria for editors and reviewers to interrogate evidence of partnership in research submissions and through dedicated calls soliciting innovative Global South or indigenous led research team outputs, among other reward strategies to promote such work.

We also propose greater institutional support for research partnerships to address issues of power, for example, increasing protected time and academic benefits for faculty engaged in building research capacity for historically or currently disadvantaged personnel (Boum Ii et al., 2018).

Dominance of standard American/British English

Much of the infrastructure and activities surrounding global health research require or assume a command of Standard American or British English (Gnutzmann, 2008; Ammon, 2011; Curry and Lillis, 2024). As such, most reviewers and agencies with decision-making power are located in primarily English-speaking countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States of America. Ultimately, a significant proportion of scientific conferences, journals, and grants default to English language, conferring an advantage to English speakers and excluding large proportions of the global South and parts of the global North. Institutional prestige has also been found to correlate strongly with institutional use of English (Hultgren, 2016).

English language supremacy is rooted in colonial and Eurocentric theories of knowledge (Thiong’o, 1992; Finkel et al., 2022; Wanyenze et al., 2022). The adoption of British and American English as standard language in much of global health furthers this, reproducing Anglophone hierarchies of linguistic respectability in global health (Tupas, 2015). This also presents barriers to the dissemination of global health research, with translation into local language often required to communicate findings for patient populations and wider audiences in settings in which the research was conducted, thus prioritizing the “foreign gaze” over the “local gaze” (Abimbola, 2019).

Proposed measures

Alternatives to English language as a default might acknowledge the usefulness of English as a lingua franca while increasing the availability of English and non-English editing and translation services. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models may help increase this access (see Table 1) by facilitating robust, reliable, and affordable AI editing and translation (Jiang and Lu, 2020). Editorial and funding processes can also become more sensitive to language diversity by supporting authors’ and applicants’ access to translation services. However, limited access to these resources due to logistical or financial limitations (such as affordability of interpreters for individual academics or even departments in low-resource settings, capacity of existing interpreters to translate scientific/technical writing, and lack of ability to reverse translate in order to assess accuracy of translation) may constrain the effectiveness of these approaches. In addition, AI may introduce its own biases to research texts.

Local, national, and international institutions in the global South may provide increased training on academic writing in non-English languages and target local journals that accept non-English manuscripts, while both global North and South institutions can provide translation services where possible. Concurrently, journals, conferences, and funding bodies can reduce language inequities by providing more opportunities for the publication and dissemination of work produced in primary languages beyond English.

Research expertise and history of collaboration via publication history and volume

Editorial and funding decisions consider research experience, which is often assessed by the history and volume of individual or collaborative publications (Stossel, 1987). While such metrics are relevant to evaluating researcher expertise and history of collaboration, they may also entrench privilege and perpetuate disparities in research, where highly recognized researchers and institutions disproportionately access opportunities for further reward, while the efforts of less-well-known counterparts receive substantially less opportunity and reward (Lavery et al., 2013; Piper and Wellmon, 2017). The over-reliance on publication-focused metrics also obscures other meaningful types of engagement in global health research, such as through advocacy or capacity building. For example, collaborations built on grassroots community engagement and organizing may be overlooked because of a lack of, or a seemingly less substantial, publication history.

Proposed measures

We propose that academic institutions work to redistribute the power accrued by researchers with more expansive publication histories by facilitating equity-driven pairings, mentoring, and collaborations with peers who may lack this experience. We also propose that editorial and funding processes integrate assignments of value to factors beyond publication history, such as duration of collaboration, service on committees and in public-facing projects, and letters of recognition and support from traditional health practitioners, study populations and communities.

Discussion

Our proposed measures for standardizing assessments of decolonization in global health are informed by other foundational and transformative scholarly works, referenced previously, that have brought much needed attention to inequity in global health practice and knowledge production (Farnbach et al., 2017; Boum Ii et al., 2018; Babyar, 2019; Hudson et al., 2020; The Lancet Global Health, 2021; Patterson et al., 2022). These measures, however, are still limited by conventional constructs of “donor/expert/advisor/capacity builder/PI” versus “recipient/learner/beneficiary/data collector/study participant” in global health, which may often value the contributions of researchers and institutions in the global North over those of their counterparts in the global South, and so undermine global health equity (Abimbola, 2019; Abimbola et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2022). We sought to be mindful about this construction in identifying specific ways researchers in a variety of contexts may use their privileges to advance equity in global health, and in describing ways that researchers in resource-limited and resource-variable contexts might “lean in,” using the resources at their disposal to highlight and expand their roles in global health.

This “leaning in” resonates with the transformative article by Boum Ii et al. (2018), and its call to place African researchers closer to the center of their research partnerships through measures such as improving communication, advancing mentorship and capacity-building, driving funding strategies, and redefining “academic currency” (Boum Ii et al., 2018). This has also been discussed by several articles by global South authors at home and in the diaspora biases (Boum Ii et al., 2018; Iyer, 2018; The Lancet Global Health, 2018; Abimbola and Pai, 2020; Erondu et al., 2020; Pai, 2020; Araújo et al., 2021; Daffé et al., 2021; The Lancet Global Health, 2021; Pant et al., 2022). We build on these prior works to propose solutions to address inequity in global health knowledge production. These proposed actions focus on dismantling structures of coloniality at multiple levels by addressing biases inherent to current editorial and funding policies and practices in global health research.

We also encourage interrogation of inequitable approaches to inclusion and productivity in research, such as cursory authorship positions that shortchange global South contributors. A less discussed but impactful factor in research productivity is language, and our proposed measures include ways to expand the languages used to perform and discuss global health beyond English. It is intuitive that “global” health research should face the fewest possible barriers to global accessibility. Advances in technology, such as the emergence of generative AI (Abimbola et al., 2021), may provide new opportunities to eliminate the barriers to access that language may create.

Our framework is intended to be an initial, broad description of an approach that could apply to multiple domains, rather than a granular prescription for implementation. Although the broad strokes could be standardized globally, such as shared creation of research projects and early determination of roles in those projects so that each participant receives appropriate credit, the details of implementation are likely to vary from location to location, given differences in culture, history, and specific challenges. It will be interesting to see how individuals, institutions, and regions adapt and apply the broader framework in their nuanced contexts.

Limitations

While we leveraged a theoretical framework (CFIR) to frame decolonization actions, we did not apply decolonial theory to the proposed actions. We agree with Chaudhuri and colleagues, whose position is that decolonization in global health must be grounded in decolonial theory, and that conceptual frameworks developed around understating of oppression and power, rather one-off metrics-based checklists and roadmaps, are needed to move from theory to practice (Chaudhuri et al., 2021), and laud further work that undergirds implementation approaches in decolonial theory. All the same, we present a process guide for changing culture in global health research, which is inherently based on colonialism and power imbalances. As a practical tool for immediate action, we also appreciate that each of the recommended strategies may not be implemented at once: this may depend on factors such as implementation climate, individual engagement, and cost. However, we believe that this can act as a resource for organizations, institutions, individuals, or groups of individuals seeking to guide discussions on consensus and prioritization of strategies to improve decolonization efforts and, through concerted discussion, generate a practical timeline for implementation. In future iterations, the proposed measures could also be identified and defined by individuals, institutions, and regions to encompass other CFIR domains to address nuances in their specific context.

We take the opportunity to state here that we are African global health researchers in the diaspora, who, while maintaining ties to our countries of origin, have affiliations to highly resourced global North institutions. Though we are directly impacted by legacies of colonialism in our lives and global health work, our experiences still may not reflect those of others without these affiliations and their associated privileges (Serunkuma, 2022). Global South colleagues without affiliations to global North institutions likely contend with more formidable manifestations of coloniality in global health research that are not reflected in this article. Pai (2022) forbes article considers the role of diaspora researchers in global health work and describes them as “double agents” in global health who leverage their global North privileges to identify and address inequities in their countries of origin. This was the perspective we sought to bring to this article.

Conclusion

Current measures for assessing the decolonization process in global health carry risk of bias, creating a need for standardized approaches. We acknowledge that research contexts and collaborations across different global North and South domains may require substantially varied strategies; thus, our proposed measures will not be universally applicable. Nevertheless, we stress that the work of decolonization, like research, is an iterative process. We anticipate that these and other such decolonization measures can be further developed into validated, theory-based approaches that will replace or improve on the status quo. Eventually, the effect size as well as costs of implementing these strategies can be measured in order to guide resource allocation. We join other practitioners in continuing to expand the body of knowledge and practice for decolonization and to promote the full practice of equity and justice in global health research.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CN and MM contributed to original conception and design of the study, manuscript. CN wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NAS-A contributed Figure 1 and provided critical review for intellectual content. All authors wrote additional sections of the manuscript and contributed to analysis, manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abimbola, S. (2019). The foreign gaze: authorship in academic global health. BMJ Glob. Health 4:e002068. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002068

Abimbola, S. (2023). Knowledge from the global south is in the global south. J. Med. Ethics 49, 337–338. doi: 10.1136/jme-2023-109089

Abimbola, S., Asthana, S., Montenegro, C., Guinto, R. R., Jumbam, D. T., Louskieter, L., et al. (2021). Addressing power asymmetries in global health: imperatives in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS Med. 18:e1003604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003604

Abimbola, S., and Pai, M. (2020). Will global health survive its decolonisation? Lancet 396, 1627–1628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32417-X

Abouzeid, M., Muthanna, A., Nuwayhid, I., el-Jardali, F., Connors, P., Habib, R. R., et al. (2022). Barriers to sustainable health research leadership in the global south: time for a grand bargain on localization of research leadership? Health Res. Policy Syst. 20:136. doi: 10.1186/s12961-022-00910-6

Akudinobi, E. A., and Kilmarx, P. H. (2022). Bibliometric analysis of sub-Saharan African and US authorship in publications about sub-Saharan Africa funded by the Fogarty International Center, 2008–2020. BMJ Glob. Health 7:e009466. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009466

Ammon, U. (2011). “The dominance of English as a language of science: effects on other languages and language Communities” in The dominance of English as a language of science. ed. U. Ammon (Beijing: De Gruyter Mouton).

Araújo, L. F., Pilecco, F. B., Correia, F. G. S., and Ferreira, M. J. M. (2021). Challenges for breaking down the old colonial order in global health research: the role of research funding. Lancet Glob. Health 9:e1057. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00196-0

Babyar, J. (2019). In search of Pan-American indigenous health and harmony. Glob. Health 15:16. doi: 10.1186/s12992-019-0454-1

Batson, A., Gupta, G. R., and Barry, M. (2021). More women must Lead in Global Health: a focus on strategies to empower women leaders and advance gender equality. Ann. Glob. Health 87:67. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3213

Boum Ii, Y., Burns, B. F., Siedner, M., Mburu, Y., Bukusi, E., and Haberer, J. E. (2018). Advancing equitable global health research partnerships in Africa. BMJ Glob. Health 3:e000868. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000868

CFIR. (2022). The consolidated framework for implementation research – Technical assistance for users of the CFIR framework. Available at: https://cfirguide.org/.

Chaudhuri, M. M., Mkumba, L., Raveendran, Y., and Smith, R. D. (2021). Decolonising global health: beyond ‘reformative’roadmaps and towards decolonial thought. BMJ Glob. Health 6:e006371. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006371

Chersich, M. F., Blaauw, D., Dumbaugh, M., Penn-Kekana, L., Dhana, A., Thwala, S., et al. (2016). Local and foreign authorship of maternal health interventional research in low-and middle-income countries: systematic mapping of publications 2000–2012. Glob. Health 12, 1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0172-x

Curry, M. J., and Lillis, T. (2024). Multilingualism in academic writing for publication: putting English in its place. Lang. Teach. 57, 87–100. doi: 10.1017/S0261444822000040

Daffé, Z. N., Guillaume, Y., and Ivers, L. C. (2021). Anti-racism and anti-colonialism praxis in Global Health-reflection and action for practitioners in US academic medical centers. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 105, 557–560. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.21-0187

Damschroder, L. J., Reardon, C. M., Widerquist, M. A. O., and Lowery, J. (2022). The updated consolidated framework for implementation research based on user feedback. Implement. Sci. 17:75. doi: 10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0

Davenport, D., Natesan, S., Caldwell, M. T., Gallegos, M., Landry, A., Parsons, M., et al. (2022). Faculty recruitment, retention, and representation in leadership: an evidence-based guide to best practices for diversity, equity, and inclusion from the Council of Residency Directors in emergency medicine. Western J. Emerg. Med. 23, 62–71. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2021.8.53754

Eichbaum, Q. G., Adams, L. V., Evert, J., Ho, M.-J., Semali, I. A., and van Schalkwyk, S. C. (2021). Decolonizing Global Health education: rethinking institutional partnerships and approaches. Acad. Med. 96, 329–335. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003473

Eisenkraft Klein, D., and Shawanda, A. (2023). Bridging the commercial determinants of indigenous health and the legacies of colonization: a critical analysis. Glob. Health Promot. :17579759231187614. doi: 10.1177/17579759231187614

Erondu, N. A., Peprah, D., and Khan, M. S. (2020). Can schools of global public health dismantle colonial legacies? Nat. Med. 26, 1504–1505. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1062-6

Farnbach, S., Eades, A.-M., Fernando, J. K., Gwynn, J. D., Glozier, N., and Hackett, M. L. (2017). The quality of Australian indigenous primary health care research focusing on social and emotional wellbeing: a systematic review. Public Health Res. Pract. 27:27341700. doi: 10.17061/phrp27341700

Finkel, M. L., Temmermann, M., Suleman, F., Barry, M., Salm, M., Bingawaho, A., et al. (2022). What do Global Health practitioners think about decolonizing Global Health? Ann. Glob. Health 88:61. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3714

Fogarty International Center. (2020a). Archive: Medical education partnership initiative (MEPI) - Fogarty International Center @ NIH. Available at: https://www.fic.nih.gov/Programs/Pages/medical-education-africa.aspx.

Fogarty International Center. (2020b). Focus: MEPI program enabled African junior faculty to develop research skills, become independent investigators - Fogarty International Center @ NIH. Available at: https://www.fic.nih.gov/News/GlobalHealthMatters/march-april-2021/Pages/mepi-junior-faculty-research-training.aspx.

Garba, I., Sterling, R., Plevel, R., Carson, W., Cordova-Marks, F. M., Cummins, J., et al. (2023). Indigenous peoples and research: self-determination in research governance. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 8:8. doi: 10.3389/frma.2023.1272318

Gnutzmann, C. (2008). English in academia: Catalyst or barrier? Germany: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag.

Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., and Kyriakidou, O. (2004). Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 82, 581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x

Guinto, R. R. (2019). #DecolonizeGlobalHealth: Rewriting the narrative of global health. International. Available at: https://www.internationalhealthpolicies.org/blogs/decolonizeglobalhealth-rewriting-the-narrative-of-global-health/ (Accessed April 27, 2023).

Hedt-Gauthier, B. L., Jeufack, H. M., Neufeld, N. H., Alem, A., Sauer, S., Odhiambo, J., et al. (2019). Stuck in the middle: a systematic review of authorship in collaborative health research in Africa, 2014–2016. BMJ Glob. Health 4:e001853. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001853

Held, M. B. (2019). Decolonizing research paradigms in the context of settler colonialism: an unsettling, mutual, and collaborative effort. Int J Qual Methods 18:160940691882157. doi: 10.1177/1609406918821574

Hill, L. H., and Holland, R. (2021). Health disparities, race, and the global pandemic of COVID-19: the demise of black Americans. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2021, 55–65. doi: 10.1002/ace.20425

Hudson, M., Garrison, N. A., Sterling, R., Caron, N. R., Fox, K., Yracheta, J., et al. (2020). Rights, interests and expectations: indigenous perspectives on unrestricted access to genomic data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 377–384. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-0228-x

Hultgren, A. K. (2016). The Englishization of non-English-dominant universities: an unforeseen consequence of university rankings? Presented at the sociolinguistics symposium 21, Murcia.

Iyer, A. R. (2018). Authorship trends in the lancet Global Health. Lancet Glob. Health 6:e142. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30497-7

Jiang, K., and Lu, X. (2020). Natural language processing and its applications in machine translation: a diachronic review, in: 2020 IEEE 3rd international conference of safe production and Informatization (IICSPI). Presented at the 2020 IEEE 3rd international conference of safe production and Informatization (IICSPI), pp. 210–214.

Keynejad, R. C., Deraz, O., Ingenhoff, R., Eick, F., Njie, H., Graff, S., et al. (2023). Decoloniality in global health research: ten tasks for early career researchers. BMJ Glob. Health 8:e014298. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-014298

Khan, M., Abimbola, S., Aloudat, T., Capobianco, E., Hawkes, S., and Rahman-Shepherd, A. (2021). Decolonising global health in 2021: a roadmap to move from rhetoric to reform. BMJ Glob. Health 6:e005604. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005604

Khan, T., Abimbola, S., Kyobutungi, C., and Pai, M. (2022). How we classify countries and people–and why it matters. BMJ Glob. Health 7:e009704. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009704

Kozlowski, D., Murray, D. S., Bell, A., Hulsey, W., Larivière, V., Monroe-White, T., et al. (2022). Avoiding bias when inferring race using name-based approaches. PLoS One 17:e0264270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264270

Kyobutungi, C., Robinson, J., and Pai, M. (2021). PLOS global public health, charting a new path towards equity, diversity and inclusion in global health. PLoS Glob Public Health 1:e0000038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000038

Laird, P., Chang, A. B., Jacky, J., Lane, M., Schultz, A., and Walker, R. (2021). Conducting decolonizing research and practice with Australian first nations to close the health gap. Health Res. Policy Syst. 19:127. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00773-3

Lavery, J. V., Green, S. K., Bandewar, S. V. S., Bhan, A., Daar, A., Emerson, C. I., et al. (2013). Addressing ethical, social, and cultural issues in Global Health research. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7:e2227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002227

Lawrence, D. S., and Hirsch, L. A. (2020). Decolonising global health: transnational research partnerships under the spotlight. Int. Health 12, 518–523. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihaa073

Matías-Guiu, J., and García-Ramos, R. (2011). Editorial bias in scientific publications. Neurología (English Edition) 26, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/S2173-5808(11)70001-3

Mbaye, R., Gebeyehu, R., Hossmann, S., Mbarga, N., Bih-Neh, E., Eteki, L., et al. (2019). Who is telling the story? A systematic review of authorship for infectious disease research conducted in Africa, 1980–2016. BMJ Glob. Health 4:e001855. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001855

Means, A. R., Kemp, C. G., Gwayi-Chore, M. C., Gimbel, S., Soi, C., Sherr, K., et al. (2020). Evaluating and optimizing the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) for use in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Implement. Sci. 15:17. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-0977-0

Milkman, K. L., Akinola, M., and Chugh, D. (2012). Temporal distance and discrimination: an audit study in academia. Psychol. Sci. 23, 710–717. doi: 10.1177/0956797611434539

Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., and Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 16474–16479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211286109

Narasimhan, S., and Chandanabhumma, P. P. (2021). A scoping review of decolonization in indigenous-focused health education and behavior research. Health Educ. Behav. 48, 306–319. doi: 10.1177/10901981211010095

Nixon, S. A. (2019). The coin model of privilege and critical allyship: implications for health. BMC Public Health 19:1637. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7884-9

Oti, S. O., and Ncayiyana, J. (2021). Decolonising global health: where are the southern voices? BMJ Glob. Health 6:e006576. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006576

Pai, M. (2020). Men in Global Health, time to “lean out” [WWW document]. Nat. Portf. Microbiol. Community. Available at: http://naturemicrobiologycommunity.nature.com/posts/to-address-power-asymmetry-in-global-health-men-must-lean-out (Accessed April 27, 2023).

Pai, M. (2022). Double agents in Global Health. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/madhukarpai/2022/02/06/double-agents-in-global-health/ (Accessed February 3, 2023).

Pant, I., Khosla, S., Lama, J. T., Shanker, V., AlKhaldi, M., El-Basuoni, A., et al. (2022). Decolonising global health evaluation: synthesis from a scoping review. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2:e0000306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000306

Parker, E. T. (2020). Chief diversity officers play a vital role if appropriately positioned and supported (opinion). Inside Higher Ed | Higher Education News, Events and Jobs. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/08/20/chief-diversity-officers-play-vital-role-if-appropriately-positioned-and-supported#:~:text=More%20than%20an%20advocate%2C%20the,to%20center%20the%20diversity%20narrative.

Patterson, K., Sargeant, J., Yang, S., McGuire-Adams, T., Berrang-Ford, L., Lwasa, S., et al. (2022). Are indigenous research principles incorporated into maternal health research? A scoping review of the global literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 292:114629. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114629

Perkins, S., Nishimura, H., Olatunde, P. F., and Kalbarczyk, A. (2023). Educational approaches to teach students to address colonialism in global health: a scoping review. BMJ Glob. Health 8:e011610. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-011610

Piper, A., and Wellmon, C. (2017). Publication, power, and patronage: On inequality and academic publishing.

Rabin, B. A., Brownson, R. C., Haire-Joshu, D., Kreuter, M. W., and Weaver, N. L. (2008). A glossary for dissemination and implementation research in health. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 14, 117–123. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000311888.06252.bb

Rees, C. A., Ali, M., Kisenge, R., Ideh, R. C., Sirna, S. J., Britto, C. D., et al. (2021). Where there is no local author: a network bibliometric analysis of authorship parasitism among research conducted in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Glob. Health 6:e006982. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006982

Rees, C. A., Rajesh, G., Manji, H. K., Shari, C., Kisenge, R., Keating, E. M., et al. (2023). Has authorship in the decolonizing Global Health movement been colonized? Ann. Glob. Health 89:4146. doi: 10.5334/aogh.4146

Rennie, D., Yank, V., and Emanuel, L. (1997). When authorship fails: a proposal to make contributors accountable. JAMA 278, 579–585. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550070071041

Roach, P., and McMillan, F. (2022). Reconciliation and indigenous self-determination in health research: a call to action. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2:e0000999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000999

Saleh, S., Masekela, R., Heinz, E., Abimbola, S., on behalf of the Equitable Authorship Consensus Statement GroupMorton, B., et al. (2022). Equity in global health research: a proposal to adopt author reflexivity statements. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2:e0000160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000160

Sam-Agudu, N. A., Paintsil, E., Aliyu, M. H., Kwara, A., Ogunsola, F., Afrane, Y. A., et al. (2016). Building sustainable local capacity for Global Health research in West Africa. Ann. Glob. Health 82, 1010–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2016.10.011

Serunkuma, Y. K. (2022). Decolonial dilemmas: The deception of a “global knowledge commonwealth” and the tragedian entrapment of an African scholar.

Shannon, G., Jansen, M., Williams, K., Cáceres, C., Motta, A., Odhiambo, A., et al. (2019). Gender equality in science, medicine, and global health: where are we at and why does it matter? Lancet (North American Ed) 393, 560–569. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33135-0

Sharma, D., and Sam-Agudu, N. A. (2023). Decolonising global health in the global south by the global south: turning the lens inward. BMJ Glob. Health 8:e013696. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013696

Smith, P. L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous Peoples: Zed Books. Available at: https://books.google.com/books?id=8R1jDgAAQBAJ.

Snow, R. C. (2008). Sex, gender, and vulnerability. Glob. Public Health 3, 58–74. doi: 10.1080/17441690801902619

Stossel, T. P. (1987). Volume: papers and academic promotion. Ann. Intern. Med. 106, 146–149. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-1-146

The Lancet Global Health (2018). Closing the door on parachutes and parasites. Lancet Glob. Health 6:e593. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30239-0

The Lancet Global Health (2021). Global health 2021: who tells the story? Lancet Glob. Health 9:e99. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00004-8

Thiong’o, N. W. (1992). Decolonising the mind: The politics of language in African literature. Nairobi: East African Publishers.

Thoits, P. A. (2010). Stress and health: major findings and policy implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 51, S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499

Walters, K. L., and Simoni, J. M. (2009). Decolonizing strategies for mentoring American Indians and Alaska natives in HIV and mental health research. Am. J. Public Health 99, S71–S76. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.136127

Wanyenze, R. K., Maragh-Bass, A. C., Tuhebwe, D., Brittingham, S., Fotso, J. C., Kanagaratnam, A., et al. (2022). Decolonization, localization, and diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility in global health and development: A call to action. Available at: https://sph.mak.ac.ug/sites/default/files/2022-09/decol_deia_white_paper_pdf.pdf (Accessed May 15, 2023).

Waziyatawin, A. W., and Yellow, B. M. (2005). For indigenous eyes only: A decolonization handbook. Santa Fe: School of American Research.

Willows, N., and Blanchet, R. (2022). Wasonti: io Delormier T. Decolonizing research in high-income countries improves indigenous peoples’ health and wellbeing. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 48, 1–4. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2022-0334

Wispelwey, B., Tanous, O., Asi, Y., Hammoudeh, W., and Mills, D. (2023). Because its power remains naturalized: introducing the settler colonial determinants of health. Front. Public Health 11:1137428. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1137428

Keywords: decolonization, white supremacy, equity, global health, research, education, implementation, implementation science

Citation: Ngaruiya C, Muhammad MI and Sam-Agudu NA (2024) A proposed guide to reducing bias and improving assessments of decolonization in global health research. Front. Educ. 9:1233343. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1233343

Edited by:

Jessica Evert, Child Family Health International, United StatesReviewed by:

Judith Lasker, Lehigh University, United StatesP. Paul Chandanabhumma, University of Michigan, United States

Joseph Grannum, Tartu Health Care College, Estonia

Copyright © 2024 Ngaruiya, Muhammad and Sam-Agudu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christine Ngaruiya, Y25nYXJ1aXlAc3RhbmZvcmQuZWR1

Christine Ngaruiya

Christine Ngaruiya Muzzammil Imran Muhammad

Muzzammil Imran Muhammad Nadia A. Sam-Agudu

Nadia A. Sam-Agudu