95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 30 January 2024

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1208925

Introduction: Late modernity influences the construction and constitution of identity and the management of adolescents’ future lives. Research has shown that identity capital predicts the resolution of a successful identity; however, in Latin America, no antecedents have conducted studies under this conceptual framework.

Aim: To analyze the relationship pattern between identity capital components and future concerns.

Methods: The participants were 703 adolescents between the ages of 15 and 19 years who, in the year 2021, were in the third and fourth years of high school in urban educational establishments in La Araucanía Chile, to whom questions from the Governance of Educational Trajectories in Europe (GOETE) adapted to the Chilean context and the general self-efficacy scale were applied. Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA) were performed to determine the suitability of the indicators to measure the constructs of interest and a structural equation analysis to determine the pattern of relationships between variables.

Results: The final model obtained excellent indicators of the goodness of fit [χ2 (422) = 965.858, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.977; TLI = 0.975; RMSEA = 0.043; SRMR = 0.056], in which it is evident that parental support and interaction are related to self-efficacy and self-concept and these, in turn, is associated with adolescents’ future concerns.

Conclusion: The relationship pattern tested shows that associations between tangible elements at the family level are related to intangible aspects of a personal nature, which can be protective factors against future concerns, and provide empirical support for the psychometric usefulness of the GOETE indicators in the Chilean context.

During life, human beings are constituted by the influence of different social systems (Butterbaugh et al., 2020), where the family and educational contexts are fundamental pillars in the integral development of individuals. In this regard, it is essential to understand the needs of adolescents from a comprehensive perspective, which allows meeting their needs to reduce behavioral problems (Schwartz and Petrova, 2018) and psychological symptomatology (Chen et al., 2007) because, in adolescence, concerns increase due to cognitive development and personal and social challenges (Vasey, 1993; Brown et al., 2006). On the other hand, adolescents’ perception of the future, expectations, and worries interact to determine how they will develop in the future, which has a crucial impact on wellbeing and future social purposes (Tikkanen et al., 2015; Kiuru et al., 2020), as the context of uncertainty can affect their success (Salmela-Aro et al., 2010; Fusco et al., 2018).

Conceptual frameworks to explain adolescent concerns have predominantly focused on individual clinical aspects (Blázquez et al., 2019; Songco et al., 2020) or unfavorable economic conditions (Conger et al., 1994), whereas, from other perspectives, multidimensional and multidisciplinary models have been developed, as is the case of the identity capital model (Côté, 2005). The latter provides a coherent and comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding such concerns as it assesses how individual resources related to self-concept, together with resources associated with interpersonal relationships, allow adolescents to function comprehensively in highly demanding and competitive social contexts (Burrow and Hill, 2011; Vera-Noriega and Valenzuela-Medina, 2012).

The identity capital model considers two types of resources: tangible and intangible. Tangible resources are ‘socially visible’ and are expressed through behaviors and possessions that facilitate access to and the ability to benefit from socially determined networks and structural positions, while intangible resources embody personality characteristics that help a person reflect on life circumstances and plan the courses of action (Côté and Levine, 2002; Côté and Schwartz, 2002).

Previous studies have demonstrated the appropriateness of using this conceptual framework in educational environments; for example, Williams and Tani (2021) showed that participants with a self-perceived probability of success have better academic performance. Similarly, another study focused on the social interaction aspects of the capital model concluded that those students who perform in environments characterized by fluid interaction more easily develop professional identification, which favors the making of work and academic projections (Jensen and Jetten, 2015).

Specifically, the data suggest that the quality of relationships with parents is significantly linked to the development of academic self-concept and self-efficacy. For example, in the study by Gniewosz et al. (2014), the central role of feedback provided by parents in the forging of academic self-concept was highlighted. In Gniewosz et al.’s study, it was evidenced that adolescents who perceived genuine interest from their parents and received positive feedback from them tended to build a positive academic self-concept, which, in turn, translated into better performance in the disciplines of mathematics and languages. The research of Ahn and Lee’s (2016) corroborated that perceived positive relationships with parents that promoted an optimistic parenting style exerted a direct influence on the formation of self-concept, which translated into a more effective adaptation to the school environment. This relationship is founded on the understanding that a supportive family environment leads to independence, self-actualization, and the opportunity for recognition during the stages of youth development (Aabedi-Asl et al., 2017).

In addition, it has been shown that relationships with parents are related to general self-efficacy in adolescents. Perceived support has been linked to higher levels of self-esteem, which, in turn, influences greater self-efficacy, which is attributed to the fact that, when children feel supported by their parents, they acquire a secure base from which to establish and achieve their goals (Frank et al., 2010). Significant others act as a “social mirror” in which the individual reflects their perceptions, which are internalized and play a fundamental role in shaping their self-concept. In this context, adolescents who perceive support from their parental figures are likely to experience a sense of approval, acceptance, and affection from their family members, which, in turn, nurtures a feeling of confidence in their abilities, an essential element in the development of self-efficacy (Sbicigo and Dell’Aglio, 2012).

Self-efficacy is highlighted as a central psychological variable of social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1977). It refers to the belief that a person has to organize and execute the strategies necessary to achieve particular objectives in an activity, facing challenging changes in a specific context (Bandura, 1986). This view coincides with the identity capital model of Côté et al. (2016) since the latter states that each person must plan and organize strategies to orient himself or herself according to their priorities. Bandura (1977) and Côté et al. (2016) conclude that self-efficacy is crucial in understanding personality phenomena and plotting actions to achieve goals.

Empirical studies have shown that self-efficacy shows a stronger association with academic performance (Bandura, 1982; Çetin and Gök, 2017; Recber et al., 2018; Bravo-Sanzana et al., 2019). Moreover, it predicts cross-sectional academic performance in any culture (Bandura, 2002). In addition, self-efficacy is a motivational variable expressed in the persistence, organization, and execution of strategies for achievement, together with behaviors that reflect frustration tolerance (Moreira et al., 2013).

Therefore, from the identity capital model, academic self-concept and general self-efficacy could be intangible components that represent protective factors against future worries in adolescents, which, in turn, would be related to parental support and interaction. In this sense, Tikkanen (2016) conducted a study in which she measured future concerns and tangible and intangible elements of identity capital through indicators implemented in the Governance of Educational Trajectories in Europe (GOETE) (Parreira do Amaral et al., 2011) that were initially proposed to assess students’ attitudes and experiences about their educational trajectories. In that study, five indexes were used corresponding to (1) future concerns, (2) academic self-concept, (3) father’s support, (4) mother’s support, and (5) interaction with parents, which were corroborated through a confirmatory factor analysis.

To date, in Chile, no research has used this conceptual framework and tested it through multivariate models; however, previous research with identity-related variables shows that elements such as positive identity, character, confidence, and connectedness can be predictors of wellbeing in Chilean adolescents (Pérez-Díaz et al., 2022a,b). In this sense and considering the relevance of identifying protective factors against future concerns at this crucial stage, this study was oriented to three objectives: (i) culturally and linguistically adapt the indicators used by Tikkanen (2016); (ii) determine the factor structure and reliability of the GOETE indicators as measures of parental support and interaction, academic self-efficacy, and future concerns; (iii) determine the associations between the proposed tangible and intangible resources with the identity capital model and future concerns.

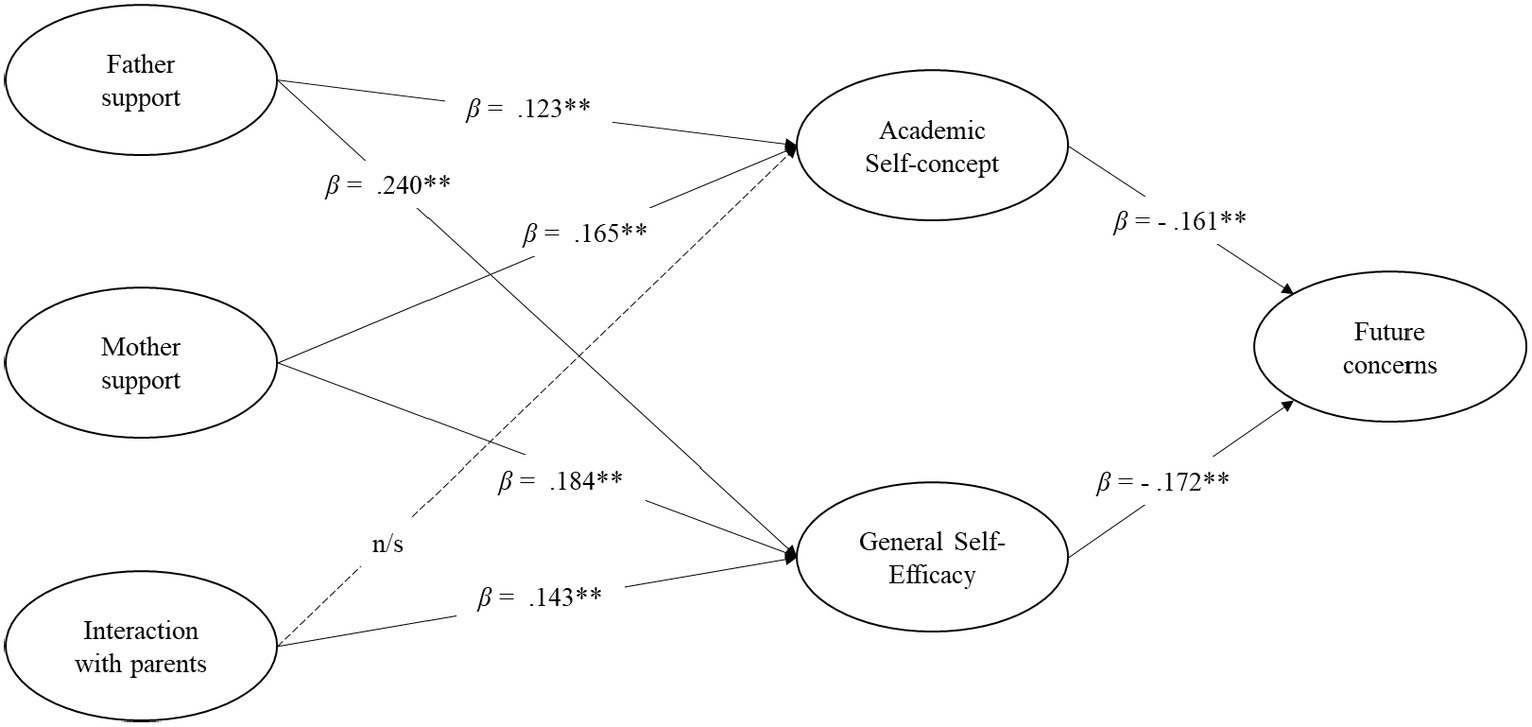

Regarding the last objective, the hypotheses proposed were that the father’s support would be directly related to academic self-concept (H1) and general self-efficacy (H2); similarly, the mother’s support would be directly related to academic self-concept (H3) and general self-efficacy (H4); and interaction with parents would be directly related to academic self-concept (H5) and general self-efficacy (H6). Finally, academic self-concept would be inversely related to future worries (H7) as would general self-efficacy (H8) (Figure 1).

This study was approved by the scientific ethics committee of the Universidad de La Frontera through the Evaluation Act of the Research Project Folio N°102/21. The methodology used in this study is quantitative, with a non-experimental and cross-sectional design. The design was implemented in two stages: the first was aimed at the linguistic and cultural adaptation of the instrument, while the second consisted of obtaining evidence of structural validity, reliability, and relationships between variables.

The sample for the first stage was obtained in a non-probability sampling. It consisted of nine adolescents studying in four establishments in the urban area in the Region of La Araucanía. For the second phase, the sample was obtained through non-probability sampling and included 703 adolescents from 52 educational establishments in the urban area of the Region of La Araucanía. The specific sociodemographic characteristics of those who comprised both samples are detailed in Table 1.

The inclusion criteria were (a) to be a student in the third or fourth year of secondary education in 2021 in a formal establishment (with municipal, subsidized, or private administrative dependence); (b) to give their assent to participate; and (c) to have the informed consent of their legal tutors.

Ad hoc sociodemographic questionnaire: to measure the variables of age, sex, educational level of the student, academic dependence, and school modality.

GOETE indicators: questionnaire developed in the research framework of the Governance of Educational Trajectories in Europe (GOETE) (Parreira do Amaral et al., 2011). The questions were initially used to evaluate students’ attitudes and experiences about their educational trajectories, as well as future concerns related to education and the job market. The measurement models proposed by Tikkanen (2016) used a total of 24 items distributed in five indices corresponding to future concerns (5 items), academic self-concept (3 items), father’s support (4 items), mother’s support (4 items), and the interaction with parents (8 items). The response scale is Likert type with five response options ranging from 1 = “never” to 5 = “always” for future concerns, father support, and mother support dimensions. At the same time, there are response options from 1 = “much worse” to 5 = “much better” for the academic self-concept dimension and from 1 = “not this year” to 5 = “daily” for the parent interaction dimension. The internal consistency reported in the original study was estimated from Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and ranged from 0.78 to 0.89.

The General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES), created by Schwarzer and Jerusalem (1995) and validated in Chile by Cid et al. (2010), is a scale developed to measure individuals’ perceptions regarding their ability to execute tasks or achieve certain levels of performance. The GSES is composed of a total of 10 items with a minimum score of 10 points and a maximum score of 40 points. The response scale is Likert type and ranges from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree.” An example of a scale item is “I can solve difficult problems if I try hard enough.” The reliability of the adapted version in Chile, estimated from Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.84.

In the first stage, a robust cultural and linguistic adaptation procedure was performed through the translation and back-translation of the GOETE indicators, following the analytical-rational procedures for instrument adaptation proposed by Elosua et al. (2014) and the guidelines systematized and issued by the International Test Commission (2017) to ensure the adaptation and equivalence of the instruments. Complementarily, the contributions of Elosua and López (2007), Hambleton and Zenisky (2011), Muñiz et al. (2013), and Muñiz et al. (2015) were considered.

Permission was requested from the instrument’s author to make the pertinent adaptation; then, the process of translating the instrument was initiated, which was performed by two independent translators. Subsequently, both versions were discussed in a committee (Cha et al., 2007) composed of translators, three education professionals, and a psychologist specializing in measurement.

This expert committee evaluated the translation of the instrument through adaptation verification criteria focused on the cultural relevance of the items and the equivalence of the items for the Chilean context concerning the original instrument (Hambleton and Zenisky, 2011). After the agreement of this committee, a pilot version of 24 items was obtained, and it underwent a back-translation process performed by two native speakers, who confirmed that the grammatical and semantic equivalence, cultural relevance, linguistic appropriateness, format, and design of the instrument were optimal.

Afterward, a cognitive interview was conducted through a focus group to evaluate the meanings given by the adolescents to the items that comprised the Spanish version of the questionnaire; after making the pertinent adjustments, these same participants answered the instrument as a pilot test to guarantee the understanding of the items and the non-existence of conflicts in the scale.

For the execution of the second phase, a collaboration agreement was reached via e-mail with the educational establishment’s management team, and the results of the research were offered back to them. In this phase, the questionnaire configured in the pilot test was massively disseminated through the QuestionPro® platform.

Preliminary data analysis shows no missing or out-of-range data. Subsequently, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were performed to determine the fit to the data of the six latent factors. This analysis was achieved through Mplus 8.2 software using the weighted least squares means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator, which is recommended in cases where the nature of the data is ordinal (Li, 2016).

The fit of the model to the data was evaluated with the following goodness-of-fit indicators: chi-square (χ2), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR). An excellent fit to the data is given by a non-significant value of p of χ2, CFI, and TLI above 0.95, while RMSEA and SRMR must be below 0.08 (Byrne, 1998; Hu and Bentler, 1999). In the case of factor loadings (λ), the criterion was that they were greater than 0.40 (Hair et al., 2019). After that, a structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed to test the relation between variables using the same criteria as CFA for model adjustment and factor loadings. The results are reported based on the standardized solution and taking as significant a nominal alpha of 0.05.

For the reliability analysis, the classic Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α) was estimated, and, following current recommendations, the McDonald Omega coefficient (ω) is also reported for each of the dimensions of the scale and the overall instrument (Trizano-Hermosilla and Alvarado, 2016). This last block of analysis was performed in the statistical program JASP 0.16.2.0.

The items of the scale that were modified following the suggestions of the adolescents in the focus group are shown in Table 2. Table 2 maintains the Spanish language as a product of the cultural and linguistic adaptation in the cognitive interview with the participants. These adaptations respond mainly to clarifying terms that address cultural elements, such as substituting “mother tongue” for “Language and Literature” to refer to the current name of the subject related to learning the local language. Similarly, a general modification was to replace “usted” (formal way of saying “you”) with “tú” (informal way of saying “you”) as the participants stated that they felt more comfortable answering in this way.

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted based on the purpose of Tikkanen (2016) for the five latent factors based on GOETE indicators. An excellent fit to the data was obtained for future concerns [χ2 (5) = 7.128, p = 0.211; CFI = 0.999; TLI = 0.997; RMSEA = 0.025; SRMR = 0.027], academic self-concept [χ2 (1) = 1.744, p = 0.187; CFI = 0.998; TLI = 0.993; RMSEA = 0.033; SRMR = 0.013], father’s support [χ2 (2) = 6.125, p = 0.106; CFI = 0.998; TLI = 0.997; RMSEA = 0.039; SRMR = 0.031], and mother’s support [χ2 (2) = 5.210, p = 0.074; CFI = 0.997; TLI = 0.991; RMSEA = 0.048; SRMR = 0.033].

For interaction with parents, the model did not show a good fit to the data [χ2 (20) = 227.506, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.921; TLI = 0.889; RMSEA = 0.122; SRMR = 0.106]. When inspecting the factor loadings, loadings below the established cutoff value were observed for items “Visited relatives or family friends /Visitar a parientes o amigos(as) de la familia” (λ = 0.137), “Done an activity like playing sports or going to a movie/Realizar una actividad como hacer deportes o ir al cine” (λ = 0.276), and “Visited a theatre, museum or the opera/Ir al teatro o museo” (λ = 0.302); therefore, the measurement model was re-specified omitting these indicators achieving an excellent fit to the data [χ2 (5) = 9.530, p = 0.090; CFI = 0.996; TLI = 0.991; RMSEA = 0.036; SRMR = 0.016]. The final version of the items is shown in Table 3.

Internal consistency coefficients were excellent for the latent factors of father’s support (α = 0.911; ω = 0.911) and parent interaction (α = 0.909; ω = 0.910); good for the latent factors of future concern (α = 0.833; ω = 0.854) and mother’s support (α = 0.855; ω = 0.853); and acceptable for the academic self-concept (α = 0.734; ω = 0.781).

The hypothesized model obtained an excellent fit to the data [χ2 (422) = 965.858, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.977; TLI = 0.975; RMSEA = 0.043; SRMR = 0.056]. In this case, mother’s support and father’s support were significantly related to general self-efficacy and academic self-concept. In contrast, parental interaction was related to general self-efficacy but not academic self-concept. In turn, general self-efficacy and academic self-concept were inversely associated with future worries (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Structural equation modeling between identity capital components and future concerns. **p < 0.001.

This study aimed to adapt the GOETE indicators culturally and linguistically to the Chilean context, to determine their psychometric properties, and to analyze their pattern of relationships based on the identity capital model. Regarding the first objective, the translation and back-translation procedures (Elosua et al., 2014) guarantee that the test items are linguistically adapted and culturally relevant for their implementation in the Chilean context in this sense, and particularly for this set of indicators, in addition to the translation of the instrument, adaptations were made to some items to reflect expressions specific to the context and would therefore be more relevant.

For the second objective, factor analyses were performed to determine the suitability of the indicators to measure the latent factors employed by Tikkanen (2016). In most of these indicators, an excellent fit to the data was achieved except for interaction with parents, in which three indicators were not representative of the factor. However, when analyzing the content of the items, it was expected that they would not work adequately for the measurement of the construct, considering that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the restrictions on mobilization and capacity limited many of the activities that were previously part of people’s daily lives. Beyond that, the other indicators adequately represented their respective factors.

The reliability indicators of the instrument were adequate for all dimensions, the lowest being those related to academic self-concept, which may be because the lower the number of items, the lower the internal consistency is (Manterola et al., 2018). In addition, compared with the reports of Tikkanen (2016) and Côté et al. (2016), higher reliability indicators were obtained, asserting that it is an accurate scale for measuring the construct.

Regarding the relationship between the components of identity capital and future concerns, the results obtained show, first, that the perceived support of the father and the mother is directly linked to the intangible elements of the capital model, such as academic self-concept and self-efficacy, and, second, that the perceived support of the father and the mother is directly linked to the intangible elements of the capital model, such as academic self-concept and self-efficacy, which can be explained primarily by the fact that receiving favorable feedback from parental figures would have a direct relationship with the formation of self-image and capabilities that can be perceived by adolescents (Gniewosz et al., 2014; Ahn and Lee, 2016).

Interaction with parental figures had a significant relationship with overall self-efficacy, which may be explained by the idea of a “social mirror” from which establishing affectively enriched relationships with valued attachment figures may represent a scaffolding for the development of adolescents’ agency capacity (Sbicigo and Dell’Aglio, 2012). For this sample, interaction with parents was not related to academic self-concept, which may be mainly attributable to the fact that, in this group of variables related to the family, father’s support and mother’s support are variables oriented to determine cognitive and behavioral variables that contribute directly to the school context, that is, actions such as attendance to school activities can strengthen academic self-concept much more than the more general activities that include the factor of interaction with parents that end up contributing to explain a broader construct such as self-efficacy.

Finally, the evidence obtained in this study shows that general self-efficacy and academic self-concept are associated with lower future concerns, which is consistent with previous findings, given that those who perceive themselves to be more solvent in life situations will present lower levels of concern in general (Barrows et al., 2013); similarly, as expected, the relations of greater magnitude appear with the academic self-concept as these are two components of self-evaluation; therefore, they are highly relevant elements for understanding the sense of agency of individuals (Yulikhah et al., 2019; Tus, 2020).

Although this study had great strengths, such as an adaptation adjusted to the cultural characteristics of the target population, the execution of robust multivariate analyses, and a large sample size, a series of limitations can also be noted. It is relevant to consider that the composition of the sample studied is consistent with the characteristics of the local population; in this study, a non-probability sampling was used, which does not allow the generalization of its results; specifically, when considering exclusively adolescents in urban contexts, it is not possible to affirm that this pattern of relationships occurs in the same way in rural environments. Future research could increase the sample size and conduct probability sampling to evaluate the generalization of the structure reported in the present study.

In addition, analyzing the instrument’s content, relational capital only considers support from their central family. However, in multiple studies, it has been reported that perceived social support is positively associated with life satisfaction and friendships are significant and influential relationships that constitute constant support, which, in turn, is related to subjective wellbeing and quality of life (Chavarría and Barra, 2014; Oh et al., 2021; Stern et al., 2021). Therefore, it is suggested that future studies develop and incorporate this dimension into the questionnaire.

In conclusion, this evidence contributes to the body of knowledge related to identity capital, considering that the pattern of relationships tested shows that associations between tangible elements at the family level are related to intangible aspects of a personal nature, which can be protective factors against future concerns. It also provides empirical support for the psychometric usefulness of the GOETE indicators in the Chilean context; it is suggested that the findings of this study should be included in intervention protocols aimed at fostering identity capital resources and assessing the concerns that adolescents have regarding the future, where educational establishments play a fundamental role by systematically collaborating with the adolescents’ life planning.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: the data set is not available due to the confidentiality stated in the research protocol. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to bW9uaWNhdml2aWFuYS5icmF2b0B1ZnJvbnRlcmEuY2w=.

The studies involving humans were approved by scientific ethics committee of the Universidad de La Frontera through the Evaluation Act of the Research Project Folio N°102/21. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

YN-E and MB-S: problem, conceptualization of the research, methodology, preparation, elaboration of the original writing, visualization, supervision, and administration of the project. OT-M and RM: data analysis and formal analysis. YN-E and OT-M: treatment of the data. YN-E, MB-S, OT-M, and RM: review, editing, and writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Thanks are due to all the adolescents who kindly agreed to answer the questionnaire. The authors appreciate the support of the UNESCO Chair: Childhood, Youth, Education, and Society. The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Vicerrectoria de Investigación y Posgrado (VRIP) of the Universidad de La Frontera for their support in the publication of this manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aabedi-Asl, H. R., Refahi, Z., and Refahi, N. (2017). Studying the relationship between parenting styles and self-concept in adolescents. Specialty J. Psychol. Manag. 3, 19–25.

Ahn, J. A., and Lee, S. (2016). Peer attachment, perceived parenting style, self-concept, and school adjustments in adolescents with chronic illness. Asian Nurs. Res. 10, 300–304. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2016.10.003

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 37, 122–147. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

Bandura, A. (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Appl. Psychol. 51, 269–290. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00092

Barrows, J., Dunn, S., and Lloyd, C. A. (2013). Anxiety, self-efficacy, and college exam grades. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 1, 204–208. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2013.010310

Blázquez, F. P., Solà, C. L., García, M. C., and Medina, M. P. (2019). Modelo de preocupación PAMPA (Percepción de amenaza futura, Activación, Motivación, Pensamiento y Acción): preocupación funcional y patológica. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica 28, 190–198. doi: 10.24205/03276716.2018.1088

Bravo-Sanzana, M., Pavez, M., Salvo-Garrido, S., and Mieres-Chacaltana, M. (2019). Autoeficacia, expectativas y violencia escolar como mediadores del aprendizaje en Matemática. Revista Espacios 40, 28–42.

Brown, S. L., Teufel, J. A., Birch, D. A., and Kancherla, V. (2006). Gender, age, and behavior differences in early adolescent worry. J. Sch. Health 76, 430–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00137.x

Burrow, A. L., and Hill, P. L. (2011). Purpose as a form of identity capital for positive youth adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 47, 1196–1206. doi: 10.1037/a0023818

Butterbaugh, S. M., Ross, D. B., and Campbell, A. (2020). My money and me: attaining financial Independence in emerging adulthood through a conceptual model of identity capital theory. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 42, 33–45. doi: 10.1007/s10591-019-09515-8

Byrne, B. M. (1998) Structural equation Modeling with Lisrel, Prelis, and Simplis: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming Psychology. London: Psychology Press

Çetin, S., and Gök, B. (2017). Modeling the factors affecting students’ mathematical literacy scores: the case of PISA 2012. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 32, 982–998. doi: 10.16986/huje.2016023162

Cha, E. S., Kim, K. H., and Erlen, J. A. (2007). Translation of scales in cross-cultural research: issues and techniques. J. Adv. Nurs. 58, 386–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04242.x

Chavarría, M. P., and Barra, E. (2014). Satisfacción Vital en Adolescentes: Relación con la Autoeficacia y el Apoyo Social Percibido. Terapia Psicológica 32, 41–46. doi: 10.4067/S0718-48082014000100004

Chen, K. H., Lay, K. L., Wu, Y. C., and Yao, G. (2007). Adolescent self-identity and mental health: the function of identity importance, identity firmness, and identity discrepancy. Chin. J. Psychol. 49, 53–72. doi: 10.6129/CJP.2007.4901.04

Cid, P., Orellana, Y. A., and Barriga, O. (2010). General self-effcacy scale validation in Chile. Rev. Med. Chil. 138, 551–557. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872010000500004

Conger, R. D., Ge, X., Elder, G. H., Lorenz, F. O., and Simons, R. L. (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Dev. 65, 541–561. doi: 10.2307/1131401

Côté, J. E. (2005). Identity capital, social capital and the wider benefits of learning: generating resources facilitative of social cohesion. Lond. Rev. Educ. 3, 221–237. doi: 10.1080/14748460500372382

Côté, J. E., and Levine, C. G. (2002). Identity, formation, agency, and culture: A social psychological synthesis. New York: Psychology Press.

Côté, J. E., Mizokami, S., Roberts, S. E., and Nakama, R. (2016). An examination of the cross-cultural validity of the identity capital model: American and Japanese students compared. J. Adolesc. 46, 76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.11.001

Côté, J. E., and Schwartz, S. J. (2002). Comparing psychological and sociological approaches to identity: identity status, identity capital, and the individualization process. J. Adolesc. 25, 571–586. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0511

Elosua, P., and López, A. (2007). Potential sources of differential item functioning in the adaptation of tests. Int. J. Test. 7, 39–52. doi: 10.1080/15305050709336857

Elosua, P., Mujika, J., Almeida, L. S., and Hermosilla, D. (2014). Procedimientos analítico-racionales en la adaptación de tests. Adaptación al español de la batería de pruebas de razonamiento. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología 46, 117–126. doi: 10.1016/S0120-0534(14)70015-9

Frank, G., Plunkett, S. W., and Otten, M. P. (2010). Perceived parenting, self-esteem, and general self-efficacy of Iranian American adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 19, 738–746. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9363-x

Fusco, L., Sica, L. S., Boiano, A., Esposito, S., and Aleni, L. (2018). Future orientation, resilience and vocational identity in southern Italian adolescents. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 19, 63–83. doi: 10.1007/s10775-018-9369-2

Gniewosz, B., Eccles, J., and Noack, P. (2014). Early adolescents’ development of academic self-concept and intrinsic task value: the role of contextual feedback. J. Res. Adolesc. 25, 459–473. doi: 10.1111/jora.12140

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., and Babin, B. J.and Anderson, R. E. (2019) Multivariate data analysis. 8th Edn. Boston, MA: Cengage.

Hambleton, R. K.and Zenisky, A. L. (2011) Translating and adapting tests for cross-cultural assessments. In D. Matsumoto and F. J. R. Vijvervan de (Eds.), Cross-cultural research methods in psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University, 46–70.

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

International Test Commission (2017). The ITC guidelines for translating and adapting tests. 2nd Edn.

Jensen, D. H., and Jetten, J. (2015). Bridging and bonding interactions in higher education: social capital and students’ academic and professional identity formation. Front. Psychol. 6:126. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00126

Kiuru, N., Wang, M. T., Salmela-Aro, K., Kannas, L., Ahonen, T., and Hirvonen, R. (2020). Associations between adolescents’ interpersonal relationships, school well-being, and academic achievement during educational transitions. J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 1057–1072. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-01184-y

Li, C. H. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav. Res. Methods 48, 936–949. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7

Manterola, C., Grande, L., Otzen, T., García, N., Salazar, P., and Quiroz, G. (2018). Confiabilidad, precisión o reproducibilidad de las mediciones. Métodos de valoración, utilidad y aplicaciones en la práctica clínica. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 35, 680–688. doi: 10.4067/S0716-10182018000600680

Moreira, P. A. S., Dias, P., Machado-Vaz, F., and Machado-Vaz, J. (2013). Predictors of academic performance and school engagement — integrating persistence, motivation and study skills perspectives using person-centered and variable-centered approaches. Learn. Individ. Differ. 24, 117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2012.10.016

Muñiz, J., Elosua, P., and Hambleton, R. K. (2013). Directrices para la traducción y adaptación de los tests: segunda edición. Psicothema 25, 151–157. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2013.24

Muñiz, J., Hernández, A., and Ponsoda, V. (2015). Nuevas directrices sobre el uso de los tests: Investigación, control de calidad y seguridad. Papeles del Psicólogo 36, 161–173.

Oh, W., Bowker, J. C., Santos, A. J., Ribeiro, O., Guedes, M., Freitas, M., et al. (2021). Distinct profiles of relationships with mothers, fathers, and best friends and social-Behavioral functioning in early adolescence: A cross-cultural study. Child Dev. 92, 1154–1170. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13610

Parreira do Amaral, M., Litau, J., Cramer, C., Kobolt, A., Loncle, P., McDowell, J., et al. (2011). Governance of educational trajectories in Europe: state of the art report. GOETE working paper. Available at: https://www.goete.eu/download/working-papers?download=24:state-of-the-art-report-governance-of-educational-trajectories-in-europe

Pérez-Díaz, P. A., Bachmann-Vera, D., and Wiium, N. (2022a). A positive-psychology-based multiple regression model predicting wellbeing in Chilean youth. Análisis y Modificación de Conducta 48, 121–135. doi: 10.33776/amc.v48i178.7490

Pérez-Díaz, P. A., Nuno-Vasquez, S., Perazzo, M. F., and Wiium, N. (2022b). Positive identity predicts psychological wellbeing in Chilean youth: A double-mediation model. Front. Psychol. 13:999364. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.999364

Recber, S., Isiksal, M., and Koç, Y. (2018). Investigating self-efficacy, anxiety, attitudes and mathematics achievement regarding gender and school type. Anales de Psicologia 34, 41–51. doi: 10.6018/analesps.34.1.229571

Salmela-Aro, K., Mutanen, P., Koivisto, P., and Vuori, J. (2010). Adolescents' future education-related personal goals, concerns and internal motivation during "towards working life" group intervention. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 7, 445–462. doi: 10.1080/17405620802591628

Sbicigo, J. B., and Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2012). Family environment and psychological adaptation in adolescents. Psicologia 25, 615–622. doi: 10.1590/S0102-79722012000300022

Schwartz, S. J., and Petrova, M. (2018). Fostering healthy identity development in adolescence. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 110–111. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0283-2

Schwarzer, R., and Jerusalem, M. (1995). “Generalized self-efficacy scale GSES” in Measures in health psychology. eds. J. Weinman, S. Wright, and M. Johnston (Windsor, England: NFER-Nelson), 35–37.

Songco, A., Hudson, J. L., and Fox, E. (2020). A cognitive model of pathological worry in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 23, 229–249. doi: 10.1007/s10567-020-00311-7

Stern, J. A., Costello, M. A., Kansky, J., Fowler, C., Loeb, E. L., and Allen, J. P. (2021). Here for you: attachment and the growth of empathic support for friends in adolescence. Child Dev. 92, 1326–1341. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13630

Tikkanen, J. (2016). Concern or confidence? Adolescents' identity capital and future worry in different school contexts. J. Adolesc. 46, 14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.10.011

Tikkanen, J., Bledowski, P., and Felczak, J. (2015). Education systems as transition spaces. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 28, 297–310. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2014.987853

Trizano-Hermosilla, I., and Alvarado, M. (2016). Best alternatives to Cronbach's alpha reliability in realistic conditions: congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Front. Psychol. 7, 1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00769

Tus, J. (2020). Self-concept, self-esteem, self-efficacy and academic performance of the senior high school students. Int. J. Res. Cult. Soc. 4, 45–59. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.13174991.v1

Vasey, M. W. (1993). “Development and cognition in childhood anxiety: the example of worry” in Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. eds. R. J. Prinz and T. H. Ollendick (New York: Plenum Press), 1–39.

Vera-Noriega, J. A., and Valenzuela-Medina, J. E. (2012). El concepto de identidad como recurso para el estudio de transiciones. Psicologia Sociedade 24, 272–282. doi: 10.1590/S0102-71822012000200004

Williams, S. C., and Tani, N. E. (2021). Capital identity projection and academic performance among historically Black college and university (HBCU) students. Grantee Submission 59, 72–89.

Keywords: adolescence, identity capital, concern, cultural adaptation, family

Citation: Neira-Escalona Y, Bravo-Sanzana M, Terán-Mendoza O and Miranda R (2024) Identity capital and future concerns in urban adolescents from La Araucanía-Chile. Front. Educ. 9:1208925. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1208925

Received: 24 April 2023; Accepted: 04 January 2024;

Published: 30 January 2024.

Edited by:

Douglas F. Kauffman, Medical University of the Americas – Nevis, United StatesReviewed by:

Jenni Tikkanen, University of Turku, FinlandCopyright © 2024 Neira-Escalona, Bravo-Sanzana, Terán-Mendoza and Miranda. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mónica Bravo-Sanzana, bW9uaWNhdml2aWFuYS5icmF2b0B1ZnJvbnRlcmEuY2w=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.