- 1Missioneo Lab, Freeland Group, Paris, France

- 2Psychology and Neurosciences Lorraine Laboratory (2LPN, EA 7489), University of Lorraine, Nancy, France

- 3DRM Lab (M&O), UMR CNRS 7088, PSL University, Paris, France

- 4Clermont Auvergne University, LMBP, UMR 6620, Aubière, France

This paper provides insights into the impacts of a self-employment and entrepreneurship education program for high-skilled long-term unemployed workers aged 45–65 in France during the COVID-19 pandemic. The training program involves individual tutoring, synchronous online classes and lead generation workshops with a freelancing project to design and present to a committee. We studied the impact of the training through an adapted version of the CHEERS questionnaire sent to the trainees six months after the training completion. In contrast to the previous literature, we show promising results for this kind of training. Our results show that this training program not only helps people to start a freelancing career but also prepares many of them to find an employee position after a long period of unemployment. We have also been able to identify the main characteristics of the jobs obtained afterwards that matter to high-skilled senior workers and to describe five trainee profiles through a cluster analysis: (1) enthusiastic but not confident, (2) quick return to salaried employment, (3) focused on freelancing, (4) demanding and disappointed elders, and (5) struggling with business tasks.

Introduction

Job prospects for individuals over 50 drastically decline, with longer unemployment periods noted (Bassanini and Duval, 2006; European Commission et al., 2010; Klehe et al., 2012; Wanberg et al., 2016), leading some to label older job seekers as the new unemployables (Heidkamp et al., 2010). These trends are inadequately addressed by policy and private sectors (Coleman et al., 2006; Cristea et al., 2022). The European Commission set a 75% employment target for those aged 20–64 by 2020, with Active Labor Market Programs (ALMPs) assisting job seekers (Kluve, 2010). While self-employment initiatives, like the European Progress Microfinance Facility, have gained support, their effectiveness remains questionable (European Commission, 2010). Amidst these challenges, senior entrepreneurship has garnered increasing attention (Ratten, 2019).

Literature review

Senior entrepreneurs, or seniorpreneurs, are defined as “individuals who have started an entrepreneurial experience after 45. They wish to overcome inactivity and social withdrawal, prolong their professional life or retrain” (free translation from Maâlaoui et al., 2014). In a comprehensive study examining the motivations of senior entrepreneurs, Perenyi et al. (2018) find that senior entrepreneurs exhibit a strong inclination towards “pull” factors in their decision to pursue entrepreneurship. Seniorpreneurs tend to want to pass their expertise, their experience and possibly a legacy to younger generations while maintaining an activity that generates a primary or complementary income. Seniorpreneurship encompasses both founding businesses and participating in startups (Maâlaoui et al., 2014). Ratten (2019) highlights the insufficiently explored area of mature or older entrepreneurship, pointing out the need for a deeper, more precise understanding in this field. This significant research gap indicates a pressing need for specifically designed support for senior entrepreneurship.

Maâlaoui et al. (2014) advocate for removing psychological and cultural barriers in entrepreneurship for seniorpreneurs, alongside facilitating business creation access. The first step is to help seniors to value their experience and skills, i.e., highlight their added value. Subsequently, energizing their creativity and providing a supportive environment with mentoring and diverse networks is crucial. Figueiredo and Paiva (2019) offer perspectives on seniorpreneurs tackling unemployment. They find a trend of ‘reluctant entrepreneurship by necessity’ among educated, older unemployed individuals and emphasize developing specific support programs for these seniorpreneurs. Alongside offering targeted support, understanding the unique training needs of seniorpreneurs is equally critical.

Support should be offered at each stage to validate and develop career plans, develop an economic model and transform it into a business plan oriented towards high-demand markets. Preferably, people from the same generation should provide this support. Indeed, a perceived gap in age and experience with younger coaches can have a negative effect (Maâlaoui et al., 2012). People in this situation might thus feel more comfortable confiding in people with a language, culture, or social vision.

Kenny and Rossiter (2018) provide an example of a training program for seniorpreneurs. The authors identified the entrepreneurial learning and support needs of the unemployed aged 50+ and the barriers that need to be addressed to transition from unemployment to self-employment. First, the authors noticed among the participants a perceived risk of being behind the rest of the workforce because of long-term unemployment. Consequently, the participants perceived a need for learning and personal development. Similarly, their long period of unemployment, and the ensuing difficulties, were identified as their main motivation to start self-employment.

The older unemployed were seemingly worried that their social capital had become obsolete due to long-term unemployment or a switch to a different industry. Peer-to-peer support and creation of a sense of community were part of their expectations from a self-employment learning program. They also mentioned the importance of learning to use new technologies and new business practices from younger generations, and particularly from younger entrepreneurs. These needs point to a greater emphasis on continuous learning and adaptation throughout one’s career.

Participants in Kenny & Rossiter’s study (2018) valued testimonials from role models who started businesses post-50 during unemployment. They advocated for better-trained frontline staff and ongoing connections between trainees and trainers post-training. This underscores the need for lifelong learning and targeted training for self-employment success. Eppler-Hattab (2022) also emphasizes lifelong learning’s role in enhancing seniors’ entrepreneurial skills. Yet even with training, there are tangible barriers that these older individuals face. Additionally, Kenny and Rossiter (2018) identify key barriers for those 50+ transitioning to self-employment: difficult access to finance and even micro-finance; lack of confidence in their ability to come up with a business idea and turn that idea into a viable commercial or social enterprise; fear of losing their welfare benefits; and lack of access to the communication channels and information needed to start a business, particularly for those who are not comfortable for searching for information online.

Beyond individual-level challenges, the overarching economic environment also plays a significant and crucial role in senior entrepreneurship. Linardi and Costa (2022) show the profound impact of the macroeconomic environment on senior entrepreneurial ventures.

Given this broad understanding of senior entrepreneurship, the purpose of this paper is to delve deeper into the impact of specific training programs for high-skilled long-term unemployed workers aged 45–65 in France during the Covid pandemic. We assess the impact of the training program in terms of creation of a self-employment or start-up professional activity, and stimulation of entrepreneurial capacities, mindset and attitudes. Our research question is thus: What works and what does not work in self-employment training for this population?

The objective is to gain insights on this training program through the following questions:

• Does the training facilitate the transition to solo self-employment? By assessing the facilitation of the transition to self-employment, this study aims to provide actionable insights for stakeholders involved in designing and implementing such training programs.

• For those who return to the labor market, what are their work conditions and job characteristics? Do they match with their expectations? A comprehensive understanding of post-training employment outcomes is crucial, not just in terms of job acquisition but also regarding the quality and fit of these roles. This analysis will shed light on the potential gaps in training programs and help refine their focus to ensure better alignment with the current job market.

• What is the typology of the trainees? Understanding the diverse backgrounds and characteristics of trainees, the study aims to identify patterns and trends that can inform the design of more tailored and targeted training programs in the future.

Method

Training context and procedure

Training program

The training assessed in the present paper is an experiential, active learning program, selected and entirely funded by the Paris-region Regional Council. The content is made of four hours of individual instruction, six days of blended learning, 14 h of freelance opportunity search workshop, design of a personal freelancing project with presentation before a committee and additional optional training sessions.

Questionnaire design

Our questionnaire is an adaption of the CHEERS (Careers after Higher Education — a European Research Survey) questionnaire (Schomburg and Teichler, 2006; Teichler, 2007). CHEERS questionnaire was designed to address job searches and the transition period from university to labor market in Europe. Our questionnaire’s measures also aim to explore the transition from long-term unemployment to self-employment after self-employment training:

• Successful transition to self-employment: the time spent and the efforts made to find desirable jobs and the job search methods employed before the first employment obtained. The smaller the efforts, the more successful the transition. Investigating the methods participants used to secure employment offers insights into the program’s efficacy in providing the necessary tools and networking opportunities. The questions curated to evaluate this aspect include assessing whether participants embarked on any independent activity and analysis of their current activity status.

• Quality of employment, i.e., characteristics of their current independent job: salary and revenue, non-monetary benefits, full-time/part-time employment, job security, status of the job, and career prospects;

• Quality of the work tasks: analysing whether their current professional activity is interesting, demanding and independent work; is linked to their expertise; provides opportunities for further education; makes use of skills acquired during trainings; and fulfils their expectations and job satisfaction;

• Perceived quality of the training assessed through targeted questions pinpointing potential gaps or strengths within the program: perceived benefits of learnings, applicability of knowledge and skills gained during the program in their current professions, and satisfaction with the program asked indirectly by ascertaining the likelihood of participants to choose the same program or organization for future endeavors.

Participants

The population studied is in transition from long-term unemployment, after around 20 years of salaried executive or high-skilled work, to solo self-employment. This study involved 97 participants aged 44–65 years (M = 53.4 years; SD = 4.8; Median = 53), including 65 females. The program was designed for people over 45, however the youngest participant was 44 years old and disabled. The oldest was 65 years old. 67% of respondents were between 50 and 59 years old.

Data collection and analysis procedure

All participants received the same distance learning training during the Covid crisis. The first session of the training started in March 2020 and the last one took place in September 2021. The questionnaire was sent to the trainees six months after program completion.

The design of the questionnaire and the descriptives statistics were carried out using Sphinx software.

We conducted two binary logistic regressions using Python: one to identify the factors influencing unemployment probability during the 6 months after the training and one to identify the factors in obtaining a freelance contract after the training.

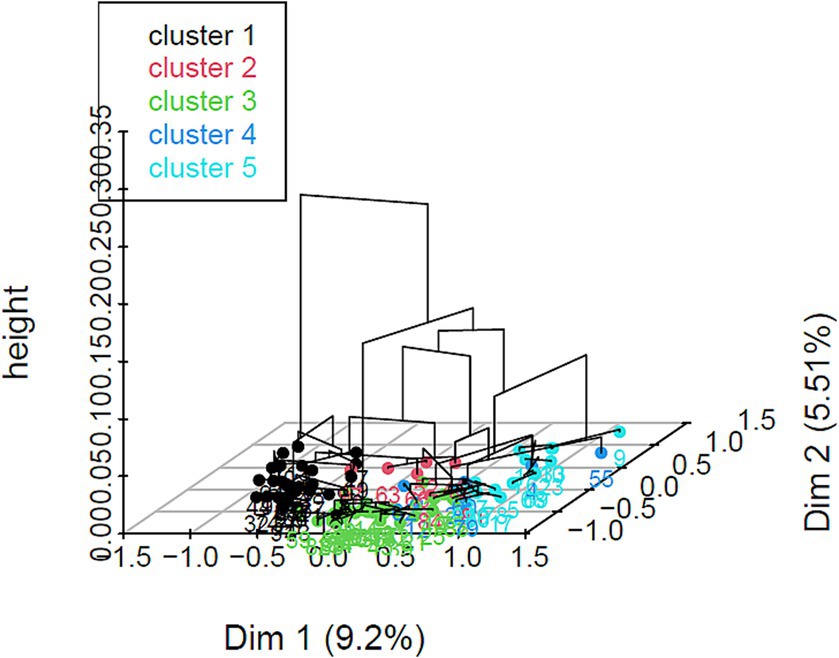

We used a systematic approach to identify distinct trainee clusters. We initiated our analysis with a Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) using the FactoMineR package’s MCA function within RStat. This technique was selected for its efficacy in Van de Velden et al. (2017) and enabled us to determine the coordinates of individuals and variables on principal components. Notably, the first and second axes accounted for 9.2% and 5.51% of the total inertia, respectively.

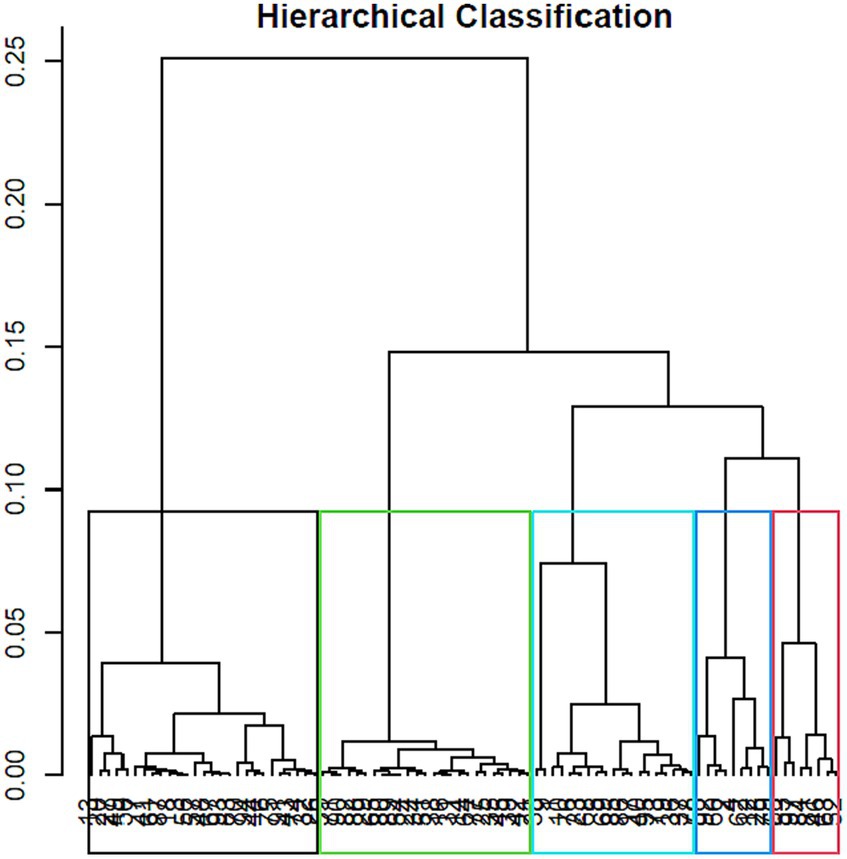

Building on the MCA results, we used Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) on the principal components using the HCPC function of the FactoMineR package (see Figures 1, 2; Table 1).

To calculate distances between individuals, we utilized the Euclidean metric, and Ward’s method was employed for aggregation, minimizing inter-class inertia loss.

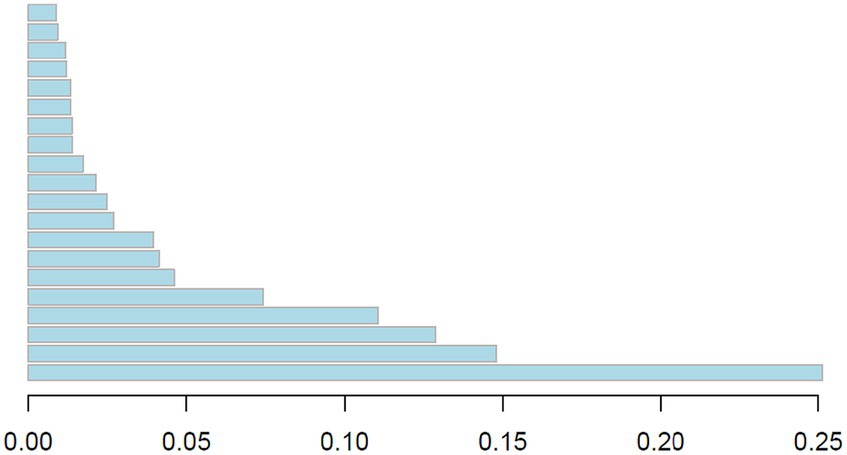

The selection of five classes is visually justified in Figure 3 showing that the gain in inertia diminishes beyond this point, aligning with the elbow method as described by Ketchen and Shook (1996).

This methodology aligns with the approach proposed by Greenacre and Blasius (2006) and offers insights into different kinds of senior entrepeneurship trainees and the impact of training on them.

Results and discussion

Successful transition to self-employment

This section includes professional inactivity rate after the training, freelance activity rate, job search methods and the number of potential clients or employers contacted.

• Inactivity rate after training: only 17 participants out of 96, or 17.71%, responded that they were unemployed, looking for work and had no short-term prospect of finding work.

Our first binary logistic regression (intercept: [−2.31289223]) showed that being unemployed without any employment or contract perspective is more probable for women (1.136110), trainees who are motivated to do a socially useful job (0.996034), trainees who answered that the training program prepared them for aspects other than freelancing (0.952323) and trainees who answered that they need more training because of tasks that were unforeseen at the time of the training (0.569816). These findings confirm that structural gender biases and systemic barriers like discrimination and skewed family role expectations impact freelancing opportunities just like salaried employment (Linardi and Costa, 2022). Additionally, individuals motivated to pursue socially beneficial work might face increased unemployment, possibly due to a misalignment between altruistic motivations and the profit-driven job market. Discrepancies between training program outcomes and labor market demands also emerge, suggesting a potential mismatch in alignment with human capital theory; participants felt prepared for roles outside freelancing, but these might not correspond with current market needs (Linardi and Costa, 2022).

Inversely, the probability of remaining unemployed after the training decreased for trainees who answered that the training helped them start or persevere in their project (−1.186497), define their service offering (−0.586994), develop their network (−0.549139), or prepare for specific freelancing tasks (−0.491995). Unemployment after the training was also less probable for people who were looking for stimulating jobs (−0.839745). These results indicate that practical, skill-based, and network-enhancing aspects of the training significantly reduce the likelihood of post-training unemployment. These aspects are crucial in equipping trainees to not find just any job, but find or create work that is stimulating, aligned with personal goals and viable in the marketplace (Kenny and Rossiter, 2018).

• Self-employment rate after training: a total of 53 participants have, or have had, an activity as a self-employed professional after the training (55.21%).

Our second binary logistic regression (intercept: [0.73473086]) showed that the probability of obtaining an independent contract after the training was higher for those who answered that the training helped them to prepare for specific freelancing tasks (0.539034) and for those finding that the training’s individual instruction has been useful (0.705136). The findings suggest that not just the acquisition of skills but also the way these skills are taught, and the quality of mentorship received are crucial factors that contribute to the successful transition into the freelance market. This highlights the need for training programs to focus on practical skills relevant to freelancing and to incorporate quality instruction as a core component of the training. This result, at the level of one training program, is in line with those of Hernández-Sánchez et al. (2019) who showed, at a regional scale, that entrepreneurship trainings has a positive impact on entrepreneurship activity rate.

Quality of employment

This section includes the rate of full-time professional activity, client diversity, the rate of permanent contracts among employees, the number of hours worked per week, and the rate of satisfaction with their professional situation. These measurements correspond to the traditional objective job quality indicators perspective (Davcheva et al., 2020).

• Full-time / part-time activity rate and numbers of hours worked per week: 44% of active respondents report part-time activity with a weekly average of 26.87 h (SD = 12.98). The median is 30 h. Only 11 people of the employed people report working less than 20 h per week. For employees these statistics may seem disappointing as full-time is associated with higher quality job. However, this number of hours seems consistent with the practices of a population of high-skilled solo self-employed professionals aged 45 and over in France (Lohmann, 2001).

• Diversity of clients: only three self-employed workers report serving a single client. Freelancers working for only one client are at risk of false self-employment (Thörnquist, 2015).

• Rate of permanent contracts among employees: among the trainees who returned to salaried employment, 11 (55%) report working on fixed-term contract. This data suggests that while the training may have helped trainees re-enter the job market, the quality of employment in terms of job security (permanent vs. fixed-term contract) was not optimal for most of them. This should be assessed regarding their long-term period of unemployment and the COVID crisis context, as per the recommendations of Linardi and Costa (2022) to take the macroeconomic situation into account.

Our data showing a quite important portion of the trainees returned to salaried employment, despite the training’s focus on self-employment, can be linked to the previous literature suggesting seniors feel a peculiar barrier to self-employment (Kenny and Rossiter, 2018). Moreover, it aligns with the observations made by Figueiredo and Paiva (2019). Their research highlights a tendency among older individuals, particularly those who have faced long-term unemployment, to prefer the stability and structure of salaried positions over the uncertainties of self-employment.

Quality of the work tasks

This section includes tasks and expertise matching, matching of job characteristics and career aspirations, satisfaction with professional activity and the opportunity to use one’s knowledge and skills in the current job.

• Task/expertise matching

28 trainees (68.3%) report that their activity matches their expertise fully or to a large extent. Only three people report that their professional activity matches their expertise very little or not at all. Ten respondents report that their activity matches to some extent to their expertise. Of these 13 people, 10 report they accepted their job because they have not been able to find a more suitable job.

• Job characteristics/career aspirations matching

The most common characteristics in the participants’ professional activity, which 62 to 78% of the participants noted, were: the possibilities of using the knowledge and skills acquired (78.95%), a largely independent work arrangement (71.05%), stimulating tasks (63.89%) and the variety of work performed (62.16%).

Many trainees’ emphasis on task-expertise alignment over traditional job factors like career prospects aligns with Maâlaoui et al. (2014). Their study suggests that this transition often entails redefining professional priorities for older individuals. As Maâlaoui et al. (2014) elucidate, senior professionals may prioritize the alignment of work with personal expertise and the satisfaction derived from meaningful tasks over conventional career advancements or job security. This is particularly true for those aiming to utilize and share their career-earned expertise in fulfilling ways (Maâlaoui et al., 2014).

• Are you satisfied with your current professional activity?

Of those employed, 36.4% said they were satisfied with their professional situation. 30.9% sad they are neither satisfied nor dissatisfied and 25.5% said they were dissatisfied. Dissatisfaction is therefore notably in the minority among employed participants.

• Taking into consideration all your current professional tasks: to what extent do you use the knowledge and skills acquired during the training?

• 67.1% of participants use the knowledge and skills acquired during the training to a certain extent or to a large extent but 15.2% said they use it moderately and 6.3% said they use them very little or not at all.

• To what extent does their current professional situation meet the expectations they had when they started the training?

Over half of respondents, 57.2% of respondents consider that their current professional situation meets their expectations or is better than what they expected. 5% say they had no expectations and nearly 38% say their situation falls short of their expectations.

Responses to the training’s effectiveness were mixed; while a majority found it beneficial, others felt it lacked in meeting their career aspirations. Overall, the program positively impacted many, especially in re-entering the job market and somewhat meeting career expectations. However, the prevalence of fixed-term contracts and the proportion of participants whose expectations were not met suggests a need for program improvement, focusing more on job security and aligning training with market realities. Results align with Kenny and Rossiter (2018), reflecting the seniors’ concerns about lagging behind in the job market. Echoing Perenyi et al. (2018) our results suggest disenchantment with the job market, not meeting seniors’ expectations.

Classification of the trainees

• Category 1. Enthusiastic but not confident (30.7% of the sample)

Participants in Category 1 found the training beneficial for personal development, starting projects, and making professional decisions. It provided a solid foundation for self-employment skills, particularly in business prospecting and defining business offerings. They felt it aided in network development, though were less certain about its effectiveness in task preparation and entrepreneurial education. Overall, they were inclined to choose the same training again.

• Category 2. Quick return to salaried employment (8%)

Category 2 participants disagreed that the training effectively taught business prospecting or aided in their career path. However, they agreed it met its objectives in entrepreneurial skills and network development. Despite its perceived strengths, they did not find it flawless and sought additional training. They quickly found regular salaried employment post-training.

• Category 3. Focused on freelancing (35.2%)

Category 3 participants, intent on freelancing, found the training effective in defining business offerings, enhancing career perseverance, decision-making, and personal development. They acknowledged the training’s success in imparting entrepreneurial skills, although they noted limited impact on network development and instruction effectiveness. Nevertheless, they viewed the training as a beneficial preparation for their freelance tasks.

• Category 4. Demanding and disappointed elders (9.1%)

These older respondents (58–65 years) critiqued the training’s efficacy in providing relevant knowledge and skills for self-employment, its preparation for current tasks, and network development. They doubted its impact on starting or maintaining career plans, decision-making, and personal development, despite learning to define their business offerings. Despite these critiques, most would still choose the same training again. This last result perhaps suggests that a longer training would be more appreciated.

• Category 5. Struggling with business tasks (17%)

Respondents in this category agreed that this program fulfilled its entrepreneurial skills training aims and helped their personal development. They also tended to agree that this training was a good preparation for their current professional tasks. In contrast, they were not convinced that this training was a good basis for learning freelance work skills or that they acquired a business prospecting method. Nor did the program help them to start or to persevere in a career plan. Most of them did not agree that they learned to define their business offerings. In hindsight, if they were free to choose again, they probably would not choose the same training. Thus, the negative views are concentrated on the business tasks of freelancing.

This study’s trainee classification reveals varied experiences, aligning with theoretical frameworks in vocational and adult education. Category 1, shows personal growth yet lacks practical confidence, reflecting Kenny and Rossiter (2018) and Perenyi et al.’s (2018) findings on seniors’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy despite training and seniors’ strong internal entrepreneurial motivation. This reflects self-efficacy theories, showing that training-acquired knowledge may not fully translate into real-world confidence. Category 2, including participants quickly returning to salaried employment, despite valuing the program’s entrepreneurial skill development. These participants did not find the program conducive to freelancing, reflecting Figueiredo and Paiva (2019) findings on seniors’ preferences for salaried employment. Category 3 shows a group dedicated to freelancing, who valued personal growth and entrepreneurial skills through the program but criticized its networking and mentoring aspects, aligning with Maâlaoui et al.’s (2012) emphasis on social capital in freelance success. Category 4, older trainees, dissatisfied and demanding, likely experienced a generational learning gap, in line with Ratten’s (2019) call for age-specific training methods. Finally, category 5, struggled mainly with the business aspects of freelancing, indicating that while the training succeeded in fostering entrepreneurial mindsets, it fell short in imparting practical business skills, underscoring the training gaps identified by Kenny and Rossiter (2018). The varied experiences highlight the need for tailored, multifaceted training in adult education, crucial for transitioning careers later in life.

Conclusion

In our endeavor to understand the implications of an online training program for unemployed highly skilled seniors during the COVID-19 pandemic, we critically assessed its effectiveness in helping them transition to self-employment. Our research, grounded in an adapted version of the CHEERS questionnaire, has offered a pioneering method for evaluating self-employment training geared towards seniors, thereby filling a crucial gap in the existing literature.

Our findings not only affirm the efficacy of the training but also underscore its broader implications. Participants who underwent this training transitioned successfully to self-employment and re-entered the traditional labor market as salaried employees, challenging prior notions in the literature and offering an optimistic perspective on the versatility of such training programs. This multifaceted impact contributes significantly to the understanding of seniorpreneurship, providing empirical evidence on the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education for this demographic.

However, our research is not without limitations. The lack of a control group, the adaptation of the CHEERS questionnaire for a different purpose, the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, potential non-response bias, and the need for more sophisticated statistical methods in future studies are critical considerations. These factors might limit our ability to draw definitive causal inferences from our results and affect the generalizability of our findings.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

SA, J-YO, and PM made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, participated to the drafting of the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content, provided approval for publication of the content and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The training program has been run by the company Trajectoires Missioneo with fundings from the Ile-de-France Region (France). The authors declare that the research was funded by Freeland Group (Paris, France).

Acknowledgments

We thank Marie Dalle-Molle, Alice Jehan, Hayet rabhi, and Laura Salouhi from Trajectoires Missioneo company for their support and useful discussions. We also thank Anta Mboup for her help with the statistical analysis and Maria Crawford for proofreading.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1199086/full#supplementary-material

References

Bassanini, A., and Duval, R. (2006). “Employment Patterns in OECD Countries: Reassessing the Role of Policies and Institutions,“ OECD Economics Department Working Papers 486, OECD Publishing. Paris, France.

Coleman, L., Hladikova, M., and Savelyeva, M. (2006). The baby boomer market. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 14, 191–209. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jt.5740181

Cristea, M. S., Pirtea, M. G., Suciu, M. S., and Noja, G. G. (2022). Workforce participation, ageing, and economic welfare: new empirical evidence on complex patterns across the European Union. Complexity 2022:7313452, 1–13. doi: 10.1155/2022/7313452

Davcheva, M., Tomás, I., and Hernández, A. (2020). Job quality indicators and perceived job quality: the moderating roles of individual preferences and gender. Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho 20, 1198–1209. doi: 10.17652/rpot/2020.4.04

Eppler-Hattab, R. (2022). From lifelong learning to later life self-employment: a conceptual framework and an Israeli enterprise perspective. J. Enterp. Commun. 16, 948–966. doi: 10.1108/JEC-01-2021-0014

European Commission , Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Maier, C., Grzegorzewska, M., Van der Valk, J., et al. (2010). Employment in Europe 2010. Publications Office. doi: 10.2767/72770

Figueiredo, E., and Paiva, T. (2019). Senior entrepreneurship and qualified senior unemployment: the case of the Portuguese northern region. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 26, 342–362. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-01-2018-0006

Greenacre, M., and Blasius, J. (2006). Multiple Correspondence Analysis and Related Methods (1st ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC.

Heidkamp, M., Corre, N., and Van Horn, C. E. (2010) “The new unemployables ”. Issue Brief, Chestnut Hill, Mass.: Sloan Center on Aging & Work at Boston College.

Hernández-Sánchez, B. R., Sánchez-García, J. C., and Mayens, A. W. (2019). Impact of entrepreneurial education programs on Total entrepreneurial activity: the case of Spain. Adm. Sci. 9:25. doi: 10.3390/admsci9010025

Kenny, B., and Rossiter, I. (2018). Transitioning from unemployment to self-employment for over 50s. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 24, 234–255. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-01-2017-0004

Ketchen, D. J., and Shook, C. L. (1996). The application of cluster analysis in strategic management research: an analysis and critique. Strat. Mgmt. J. 17, 441–458.

Klehe, U.-C., Koen, J., and De Pater, I. E. (2012). “Ending on the scrap heap? The experience of job loss and job search among older workers” in The Oxford handbook of work and aging. eds. J. W. Hedge and W. C. Borman (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press), 313–340.

Kluve, J. (2010). The effectiveness of European active labor market programs. Labour Econ. 17, 904–918. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2010.02.004

Linardi, M. A., and Costa, J. (2022). Appraising the role of age among senior entrepreneurial intentions. European analysis based on HDI. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 14, 953–975. doi: 10.1108/JEEE-12-2020-0435

Lohmann, H. (2001). Self-employed or employee, full-time or part-time? Gender differences in the determinants and conditions for self-employment in Europe and the US, vol. 38 Arbeitspapiere – Mannheimer Zentrum für Europäische Sozialforschung.

Maâlaoui, A., Bouchard, G., and Safraou, I. (2014). Les seniorpreneurs: Motivations, profils, accompagnement. Entrep. Innov. 20, 50–61. doi: 10.3917/entin.020.0050

Maâlaoui, A., Fayolle, A., Castellano, S., Rossi, M., and Safraou, I. (2012). L’entrepreneuriat des seniors. Rev. Fr. Gest. 38, 69–80. doi: 10.3166/rfg.227.69-80

Perenyi, A., Zolin, R., and Maritz, A. (2018). The perceptions of Australian senior entrepreneurs on the drivers of their entrepreneurial activity. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 24, 81–103. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-12-2016-0424

Ratten, V. (2019). Older entrepreneurship: a literature review and research agenda. J. Enterp. Commun. 13, 178–195. doi: 10.1108/JEC-08-2018-0054

Schomburg, H., and Teichler, U. (2006). “Higher education and graduate employment in Europe: results from graduate surveys from twelve Countries ” Springer, Dordrecht.

Teichler, U. (2007). Does higher education matter? Lessons from a comparative graduate survey. European Journal of Education 42, 11–34.

Thornquist, A. (2015), “False self-employment and other precarious forms of employment in the ‘grey area’ of the l abour market”. International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations, 31, 411–429.

Van de Velden, M., Iodice D’Enza, A., and Palumbo, F. (2017). Cluster Correspondence Analysis. Psychometrika. 82, 158–185.

Keywords: entrepreneurship education, self-employment, long-term unemployment, entrepreneurial skills, career transition, seniorpreneur, COVID, pandemic

Citation: Atarodi S, Ottmann J-Y and Mbaye PAM (2024) Maximizing employability and entrepreneurial success: a training program for highly skilled seniors transitioning into freelance consulting. Front. Educ. 9:1199086. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1199086

Edited by:

Douglas F. Kauffman, Medical University of the Americas—Nevis, United StatesReviewed by:

Andreas Walmsley, University of St Mark & St John, United KingdomEmilia Herman, George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences and Technology of Târgu Mureş, Romania

Copyright © 2024 Atarodi, Ottmann and Mbaye. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Siavash Atarodi, c2lhdmFzaC5hdGFyb2RpQG1pc3Npb25lby5mcg==

Siavash Atarodi

Siavash Atarodi Jean-Yves Ottmann

Jean-Yves Ottmann Papa Alioune Meïssa Mbaye

Papa Alioune Meïssa Mbaye