94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 22 April 2024

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1169269

This article is part of the Research TopicFrom Rote Learning to Effective TeachingView all 4 articles

Teachers are pivotal to any efforts to raise the devastatingly low levels of foundational learning that persist across much of the Global South. However, in many education systems, teachers are not equipped with the resources needed for effecting such change. Moreover, numerous reforms have failed to change either children's learning levels or the teacher norms that inadvertently contribute to low learning levels. Moving beyond these circumstances requires an understanding of the factors underlying such norms and of how these factors affect opportunities for changing teacher norms. I examine this question by analyzing the transcripts of interviews with 14 pairs of interlocutors from various contexts who have complementary expertise related to teacher norms. Based on this analysis, I develop a conceptual framework for mapping the factors that sustain teacher norms onto four domains of teachers' experiences: selves (“what I value”), situations (“what can be done”), standards (“what those in charge expect”), and society (broader influences). Different configurations of underlying factors can yield different types of norms: coherent norms, compromise norms, and contestation norms. Drawing on the interviews, I illustrate coherence, compromise, and contestation by discussing examples of teaching narrowly to certain standards and being absent from the classroom during scheduled lessons. Each type of norm offers distinct opportunities for changing the status quo by influencing particular aspects of teachers' selves, situations, and standards. Additionally, one broader opportunity for change is reshaping societal narratives about education and the teaching profession.

How do the factors underlying teacher norms affect opportunities for changing those norms that hinder children's learning? This question has a particular urgency in the many education systems in the Global South that have devastatingly low levels of foundational literacy and numeracy (World Bank, 2019; Crouch et al., 2021) and a demotivated and under-equipped teaching profession (Venkat and Spaull, 2015; Bold et al., 2017). Entrenched teacher norms can play a central role in the persistence of these low learning levels (e.g., Sabarwal et al., 2022)—yet, in exceptional cases, informal norms can also be key influence in transcending these grim trends (e.g., Bano, 2022c).

In this paper, I examine this question by analyzing the transcripts of 14 paired interviews that I conducted in an asynchronous symposium with a total of 28 interlocutors. Each pair of interlocutors had complementary expertise related to norms in the teaching profession, with an emphasis (but not an exclusive focus) on education systems in the Global South. The transcripts from these interviews, along with three discussant essays, are available as an open-access volume titled Purpose, pressures, and possibilities: Conversations about teacher professional norms in the Global South (Aiyar et al., 2022). Based on these interviews, with support from the wider research literature, I argue that different configurations of underlying factors across the four domains of teachers' selves, situations, standards, and society lead to three different types of teacher norms—i.e., norms of coherence, compromise, or contestation—each of which offers different opportunities for change.

In the next section, I give a working definition of teacher norms, and then outline three features of teacher norms from the research literature: they are shaped by competing expectations, they emerge from individual and collective beliefs, and they affect policy implementation. I then describe the data sources and analytical approach used in this paper. This is followed by three sets of results. First, I propose a conceptual framework for mapping the multifarious influences on teacher norms onto four domains: selves, or teachers' perceptions of what they value; situations, or teachers' perceptions of what can be done in their classrooms and schools; standards, or teachers' perceptions of what those in charge (broadly conceived) expect; and society, which encompasses broader influences. Second, I identify three types of teacher norms—coherence, compromise, and contestation—that result from different configurations of underlying factors and that represent different ways in which teachers respond to top-down standards. Third, I consider how different types of norms affect opportunities for improving children's learning. Finally, I draw the analysis together with a discussion.

For the purposes of this study, I define teacher norms as dominant beliefs among teachers about the most suitable practices and priorities in their contexts. This definition thus characterizes teacher norms as beliefs rather than behaviors (as explained below), and as residing in the collective rather than the individual. In the words of interview interlocutor Dan Honig, “norms, ultimately, are a kind of collective belief about each other's collective beliefs” (p. 90 in the interview transcripts).

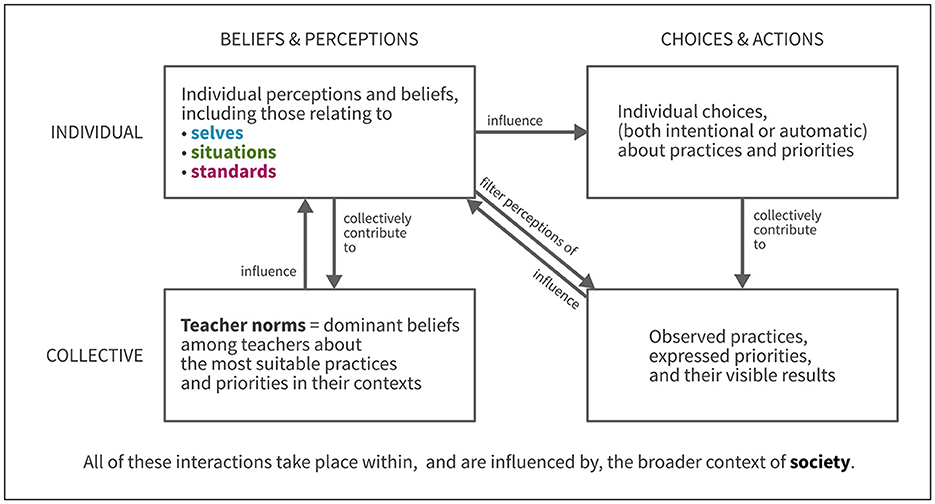

For clarity, I represent this characterization of teacher norms in a schematic diagram in Figure 1. This diagram is not intended to be a technically precise contribution to theory, but simply a device to lay the groundwork for subsequent analysis. As such, it mentions four domains—selves, situations, standards, and society—that I only explore in later sections. Moreover, it is very much a schematic, in the sense of being a simplified sketch.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram illustrating the interplay between teacher norms and related constructs.

This schematic diagram draws on a range of sources. It was informed by Maxwell (2012) critical realist framing of a 2x2 matrix with symbolic/mental phenomena vs. physical phenomena in one dimension, and the individual vs. the collectivity on the other. Other theoretical influences include political theorist Zacka's (2017) construct of “modes of appraisal,” which filter the information that street-level bureaucrats perceive in a given situation, and which are themselves influenced by this incoming information. These “modes of appraisal” prompted the inclusion of the diagonal arrows indicating mutual influence between individual beliefs/perceptions and collective choices/actions. Social norms scholar Bicchieri's (2017) observation that individual decisions about how to behave in a given environment can be made in either a rational, deliberative mode or a subconscious, heuristic mode prompted the qualification that individual choices about practices and priorities can be either intentional or automatic.

Note that all the arrows in this schematic indicate relationships of ongoing influence, rather than suggesting any strict sequence or causal sufficiency. Accordingly, two clarifications are in order, one conceptual and one practical.

Conceptually, I am making the weak claim that a teacher's beliefs about what most teachers think is the most suitable thing to do (i.e., their individual beliefs about collective teacher norms, as defined in this paper) can influence their choices and actions over and above other circumstantial factors (e.g., students' needs, available resources, potential consequences) that influence the suitability of one action over another. I call this a weak claim both because I conceptualize norms as one of many possible influences on teachers' choices and actions—teachers can and do diverge from dominant norms—and because I do not make any strong assertions about the pathways of such influence. Norms may exert influence through a variety of channels, such as triggering threats of direct social sanctions (Bicchieri, 2017), operating as focal points that prompt people to choose one equilibrium over others (Basu, 2018), or shaping teachers' personal beliefs as they are socialized into the profession (Lortie, 1975; see also Bourdieu, 1977), among others. These diverse channels of influence exist partly because what is “most suitable” in a challenging, resource-constrained classroom or school setting (i.e., the overwhelming majority of classroom settings in the Global South) may not necessarily be what teachers believe they should do from a moral or ethical standpoint, or what would be the most efficient or effective choice from a prudential standpoint, but simply the least bad option.

Practically, in this paper I am more interested in the combinations of factors that are currently sustaining teacher norms than in their chronologically causal origins. A norm (set of beliefs) and an associated pattern of behavior may co-occur in a given setting because the belief emerged from the behavior, the behavior emerged from the belief, or both emerged from a complex mutual interaction with other contextual factors or through some other causal relationship (see, e.g., Buehl and Beck, 2015, on teacher beliefs and practices; Bicchieri, 2017, on collective customs, descriptive norms, and social norms). Disentangling the causal origins of patterns of human beliefs and behavior is a hugely complex process (see, e.g., Sapolsky, 2017: Introduction), requiring a much greater volume and precision of empirical data than the interview transcripts that I analyze in this cross-context synthesis. Moreover, teacher norms are so intricately embedded in education systems that even definitive knowledge about the events and phenomena that caused a certain norm to emerge would only be one piece of the puzzle in identifying present opportunities for changing that norm (if such change is warranted). Accordingly, I pay less attention to time-ordered causal chains than to big-picture, systemic patterns.

Two further points about this definition of teacher norms are worth mentioning. First, I conceptualize norms as dominant beliefs rather than uniformly shared ones. A teacher may recognize a set of beliefs as being dominant in their context without subscribing to it. This is reminiscent of the psychometric concept of norm-referenced assessments and the statistical concept of the expected value of a (normal) distribution. Second, different teachers may demarcate the boundaries of their contexts differently, such that a single geographic context may have multiple sets of teacher norms. For example, even in contexts with a demotivated, deprofessionalized teaching corps with norms that do not cultivate children's learning, there may be a subset of dedicated teachers (perhaps in a single school or within a specific social network) who see each other as the salient context for norms rooted in ambitious professional ideals.

One of the key characteristics of teacher norms, as discussed in the research literature, is that these norms are fundamentally shaped by the competing demands that teachers juggle daily. Teachers practice their craft at the intersection of multiple expectations from various education system stakeholders, and of overlapping constraints and possibilities emerging from their immediate classroom and school contexts and from their accumulated experiences and training. This is hardly a new insight. The reality of “multiple and competing and sometimes capricious policies” (Ball et al., 2012, p. 141) has been noted in the context of schools by numerous scholars (e.g., Broadfoot et al., 2006), and in the more general context of frontline public service delivery by Lipsky (2010 [1980]) and others (e.g., Zacka, 2017).

Empirical research has documented a wide range of teacher norms that emerge from reconciling—or at least, coping with—such competing demands. To illustrate, in a study of teachers in Delhi schools, Davis et al. (2019) observed a norm of teachers spending approximately half their working hours on non-teaching-related tasks, largely because of administrative requirements that impinge on time that teachers would prefer to spend on teaching-related tasks (see also Aiyar et al., 2021; Siddiqi, 2022). Also, Booher-Jennings (2005) and Gilligan et al. (2019) have documented norms of “educational triage,” where teachers prioritize certain students and compromise the education of others when exam-based incentives come into tension with a wide spectrum of student academic needs in Texas and Uganda, respectively. Mizel (2009) outlines accountability norms that emerge in Bedouin schools in Israel when loyalty to the tribal sheikh outweighs compliance to government stipulations.

To explore two examples in more detail, Long and Wong (2012) offer a fascinating account of competing priorities at a residential school in an area of China that was devastated by an earthquake, which killed almost half of the school's students and a fifth of its teachers (along with many family members of survivors). On one hand, this disaster was followed by an awareness that socioemotional care mattered. On the other, the earthquake brought the school to national attention, which generated pressure to produce good exam results as a symbol of triumph over adversity. The latter pressure predominated, resulting in a norm that “the teachers and students' only legitimate use of time was to improve academic performance, which was, in turn, taken as a reflection of the teachers' ability, effectiveness, and productivity” (Long and Wong, 2012, p. 246). In turn, Cliggett and Wyssmann (2009) analyze the various strategies that Zambian teachers use to supplement their inadequate and irregular salaries. These strategies are shaped by a mix of formal regulations, informal expectations, societal perceptions, and situational constraints. Accordingly, they are perceived in different ways, including “officially encouraged” strategies such as gaining further qualifications to climb the salary scale, “normal and expected” practices such as small-scale farming, and “regrettable but understandable” strategies such as selling packets of instructional material to students rather than teaching that material in class.

Another important feature of teacher norms is that they cannot be analyzed solely as patterns of behavior or practice. Rather, as indicated in the working definition and in Figure 1, norms are patterns of belief. Bicchieri (2017), a leading theorist of social norms, argues that viewing norms as commonly performed actions without considering the underlying beliefs can lead to ineffective strategies for norms change: a norm driven primarily by a desire for material gain cannot be changed in the same way as a norm driven primarily by the desire to maintain social conformity.

In educational research, teachers' beliefs have long been an object of study because they tangibly influence teaching practice. In a review of empirical studies of teacher beliefs on self-efficacy and on subject-specific pedagogy (e.g., beliefs about teaching science), Kagan (1992) concludes, “The more one reads studies of teacher belief, the more strongly one suspects that this piebald form of personal knowledge lies at the very heart of teaching” (p. 85). This aligns with Lortie's (1975) well-known argument that a teacher's classroom practice is strongly conditioned by beliefs about learning and teaching developed during the “apprenticeship of observation” throughout their own years of schooling. To give a recent empirical example, Filmer et al. (2021) found that one of the most important predictors of primary school students' learning gains in Tanzania is whether their teacher believes that it is possible to help struggling or disadvantaged students to learn.

Teacher norms involve an interplay between the individual and the collective. As beliefs, they reside within individual teachers' minds; as dominant beliefs within particular contexts, they are inherently collective. Such individual-group dynamics have been explored in various strands of social theory. In public policy analysis, March and Olsen (2008) pithily summarize their conceptualization of the “logic of appropriateness” shaping individual behavior within institutions as follows:

The simple behavioral proposition is that, most of the time humans take reasoned action by trying to answer three elementary question: What kind of situation is this? What kind of person am I? What does a person such as I do in a situation such as this? (p. 690).

Similarly, Swidler (1986) sociological analysis conceptualizes culture as “a ‘tool kit' of symbols, stories, rituals, and world-views, which people may use in varying configurations to solve different kinds of problems” (p. 273). Cultural psychologists Markus and Kitayama (2010) argue that culture and selves are mutually constituted: every person “requires input from sociocultural meanings and practices,” and, concurrently, “peoples' thoughts, feelings, and actions (i.e., the self) reinforce, and sometimes change, the sociocultural forms that shape their lives” (p. 423). In their study of teaching practices across countries, Stigler and Hiebert (1999) describe “cultural scripts” that “reside in the heads of participants,” “guide behavior,” and “are widely shared” within a culture (p. 59). Without getting into the theoretically significant differences between these notions of culture, a key point for the purposes of this study is that norms involve an interaction between individual beliefs and collective frames of meaning.

Teacher norms are not only shaped by government policy (among other demands), but they also influence policy implementation. Because of these complex interplays between the individual and the collective and between beliefs and actions, the failure to pay attention teacher norms can result in failed attempts to reform education systems. For example, a large-scale, technically sound, and consistently implemented intervention to improve school quality assurance in Madhya Pradesh, India, did not have any effect on either teacher practice or student learning—in part because the intervention design did not take into account how teachers would perceive such a reform, nor how they understood their relationship to the local education administrators who played a key role in the intervention (Muralidharan and Singh, 2020). More generally, studies of mechanisms and theories of change in policy implementation have noted that subjective perceptions, local behavioral norms, and tacit assumptions can be vital to the success of failure of a policy program (Pawson and Tilley, 1997; Williams, 2020).

Studies of education policy and educational management across contexts have similarly found that good policy design is intertwined with teachers' beliefs (which include teacher norms, as defined above). For example, in a study of teacher evaluation practices across school districts in the U.S., Wise et al. (1985) concluded that effective teacher evaluation systems must be compatible with (among other elements) how teaching is conceptualized in the local district, where such conceptualizations span “labor, craft, profession, and art” (p. 65). In their study of teachers' perceptions amid policy changes in accountability, centralization, and autonomy, Broadfoot and Osborn (1993) observed that teachers in England and France have distinctly different beliefs about the nature of professional responsibility, and argue that “if change in education is to be successfully implemented, much more attention than hitherto needs to be given to considering ways of changing how teachers think, which in turn will impact upon what they do” (p. 127, emphasis original). In a prior study, I found that Finland's and Singapore's approaches to teacher accountability—both of which are celebrated as “best practices” despite being mutually incompatible—succeed because they each cohere with the conceptions with the conceptions of motivation held by teachers in their respective contexts (Hwa, 2022).

Against this backdrop of teacher norms that mutually interact with policy contexts, and of the interaction between individual and collective beliefs and actions, I now turn to the research question: How do the factors underlying teacher norms affect opportunities for changing those norms that hinder children's learning?

The main data source in this analysis is a publicly available set of edited transcripts from an asynchronous symposium of 14 loosely structured, conversational interviews that I conducted with pairs of interlocutors who have complementary expertise related to teacher norms. As shown in Table 1, these interlocutors spanned a range of affiliations and academic disciplines. When selecting interlocutors, I aimed for representation across genders, geographic regions, Southern/Northern backgrounds, and academics/practitioners. Of the 28 interlocutors, eight have classroom teaching experience.

Each paired interview lasted for roughly an hour and loosely followed a set of discussion questions. The three main substantive questions related to what some of the dominant norms among teachers were (especially teachers in the Global South), why certain practices or priorities become dominant norms, and how to reorient detrimental teacher norms for educational improvement. Given the nature of these paired interviews as conversations between pairs of experts, I acted less as a detached interviewer and more as a facilitator adapting to the flow of conversation.

Interviews were conducted and recorded via Zoom (with one exception, which was in person). Audio recordings were machine-transcribed using Otter.ai, after which I edited them for accuracy and so they would read as conversational written text. Next, interlocutors had the option of revising the transcripts as much as they wanted to, in order to balance the spontaneity of a conversation with opportunities for reflection. This combination of live interviews and asynchronous revisions leading to a compilation of edited transcripts was inspired by Munck and Snyder (2008) approach in Passion, craft, and method in comparative politics. In preparation for publication in an edited volume, the edited transcripts were professionally copyedited, after which interlocutors again had the opportunity to check and revise the text. The volume containing the transcripts and the rest of the asynchronous symposium is available at https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-Misc_2022/06.

The analysis was loosely inspired by grounded theory, an approach for inductively constructing conceptual frameworks based on context-specific data through iterative “constant comparison” between data, analytical codes, and emerging theories (Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Charmaz, 2014). In total, I conducted three rounds of coding of the interview transcripts. Besides these transcripts, this iterative process drew on the wider social science literature on teacher beliefs and teacher behavior as well as social and occupational norms (including a systematic literature search described below).

I began with a round inductive coding of the edited interview transcripts, in line with initial coding in grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014). I coded the interview transcripts manually in NVivo. For the initial coding, I constructed codes inductively while reading the transcripts, iteratively revising, combining, and splitting codes as the analysis progressed, and revisiting previously analyzed transcripts whenever the coding scheme had changed significantly. After the initial coding was complete, I took some time to reflect on the emerging coding scheme alongside key literature related to teacher norms. This resulted in an initial version of the “four domains” conceptual framework that I describe below.

The second round of coding focused on validating the conceptual framework and exploring a working hypothesis that emerged alongside the conceptual framework: that practices and priorities are most likely to become dominant norms when they are aligned with factors across multiple domains. This round of coding was loosely in line with grounded theory's focused coding, which prioritizes the codes that are most significant to the emerging theory (Charmaz, 2014). This round of coding forms the basis of the results reported in “Four domains shaping teacher norms: selves, situations, standards, and society.”

Alongside this second round of coding, I stress-tested the conceptual framework using a systematic literature search for a set of articles describing teacher norms and associated contextual factors. Although the paired interviews included a diverse range of interlocutors, these interlocutors were drawn from my primary and secondary networks and thus constituted a non-systematic sample. The aims of this systematic literature search were to ensure that the conceptual framework was not overly influenced by avoidable bias, to mitigate any echo-chamber effects, and to test the conceptual framework against descriptions of teacher norms that had richer detail of teachers' experiences and environments than would typically emerge in a conversational interview with multiple, turn-taking interlocutors. The search, conducted via Scopus, was designed to be both systematic and efficient.1 It yielded 179 results, which were whittled down through a series of exclusion criteria to 11 articles. I analyzed these using an approach similar to the second round of coding for the interview transcripts. I do not report on this part of the analysis here, but it largely supported the conceptual framework, and two of the 11 articles appear as examples in Section 2.2 above on teacher norms being shaped by competing expectations (i.e., Cliggett and Wyssmann, 2009; Long and Wong, 2012).

After validating the four domains of the conceptual framework, I conducted a third round of coding to refine the typology of teacher norms and to explore what the interview transcripts suggest about entry points for changing teacher norms to better cultivate children's learning. To do so, I first extracted text segments in which interlocutors describe teacher norms that can have direct negative effects on children's learning in the classroom (excluding segments that briefly mention relevant norms without discussing underlying factors). I identified the underlying factors described in these segments; classified these factors into the four domains; and then used the configurations of factors underlying each norm to determine its type. This analysis forms the basis of the results reported in “Three types of teacher norms: coherence, compromise, and contestation.” Next, to elicit suggestive evidence on how opportunities for changing teacher norms differ across the three types of norms, I extracted segments in which interlocutors described empirical examples of attempts to reform teacher norms toward improvements in student learning, whether or not these attempts were successful. As far as possible, I categorized these reform attempts by the type of norm they intended to change. The results from this part of the analysis are reported in “Opportunities for changing teacher norms.”

Throughout this paper, text from the interview transcripts is cited with expert interlocutors' names and page numbers from the open-access compilation of transcripts and essays (Aiyar et al., 2022).

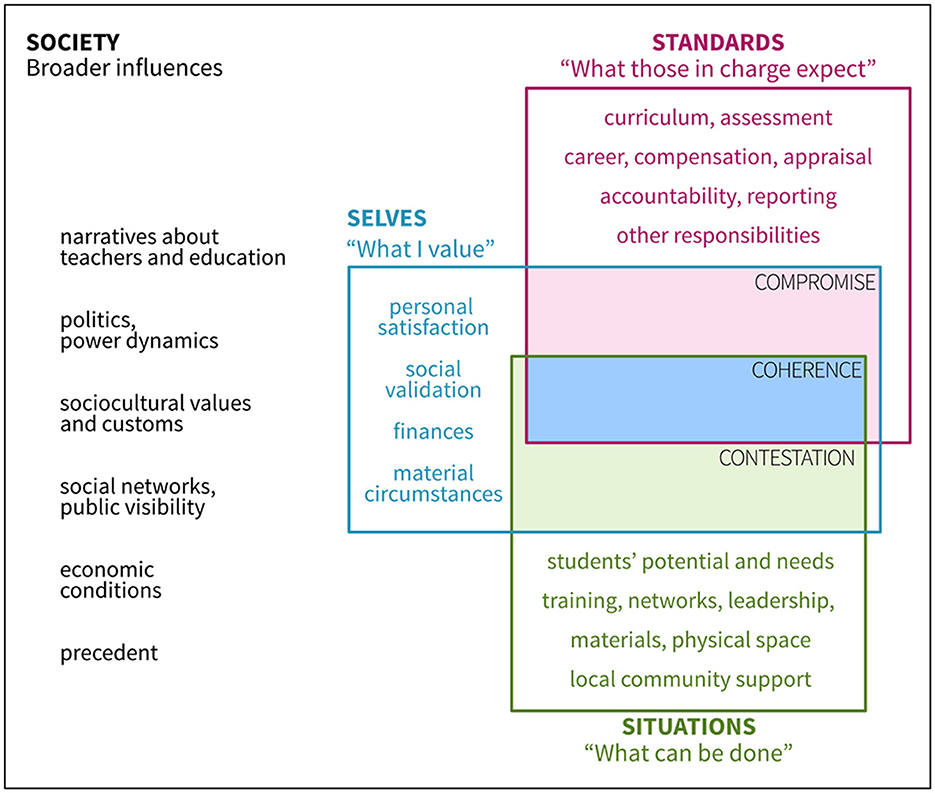

My analysis of the factors underlying teacher norms, as described in the interview transcripts, led to the conceptual framework shown in Figure 2. This framework focuses on four domains that shape teacher norms: selves, or “what I value”; situations, or “what can be done”; standards, or “what those in charge expect”; and society, or broader influences. (Note that this framework is not a Venn diagram. As I discuss in the next section, the overlaps between domains do not represent intersections as in set theory. Rather, they represent emergent norms that are supported by elements of the various domains.)

Figure 2. Conceptual framework: the four domains shaping teacher norms, with illustrative elements in each domain. The illustrative elements in the four domains are non-exhaustive and are derived from analyzing the paired interviews.

This framework was designed to respect not only the complex, systemic interactions discussed in the interviews, but also the centrality of teachers' agency and perspectives—which, as several interview interlocutors noted, are often disregarded in education policy, to its detriment. Accordingly, three of the four domains are framed from a teacher's standpoint. As will be discussed below, society is not represented in terms of teachers' perceptions, but it influences these perceptions nonetheless (this is similar to how beliefs, choices, and norms are all set in the context of society in Figure 1).

Given that this framework draws on systems thinking, it bears a family resemblance to frameworks that are similarly informed by systems thinking. These include the RISE education systems framework, which uses a bird's eye view to map out principal-agent relationships throughout an education system (Pritchett, 2015; Silberstein and Spivack, 2023), and various ability-motivation-opportunity frameworks in business management (e.g., Blumberg and Pringle, 1982), which are oriented toward managers rather than frontline practitioners. The framework also drew inspiration from Lahlou's (2017) “installation theory,” in which much of human behavior in social settings is conditioned by installations, or “specific, local, societal settings where humans are expected to behave in a predictable way” (p. xxiii). Installations consist of three layers—material affordances, embodied competencies, and social institutions—which collectively prompt individuals to act in a certain way. Lahlou gives the example of the typical airport, where the floorplan and signboards (material), cumulative experience of air travel (embodied), and rules about boarding a flight (social) all interact to direct masses of free-willed agents toward outwardly similar behavior.

Besides diagramming how these domains can converge to support certain norms, another function of this framework is mapping competing factors within or between domains. For example, interlocutor Soufia Siddiqi observed that the teachers she encountered in her fieldwork in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, carried not only two forms of identity as teachers and as bureaucrats (both of which span selves and standards), but also a third identity from gendered societal roles (which span selves and society) that profoundly affected their professional lives. She concluded that:

Overall, it's these accounts of many competing identities that allow my research to start saying: these are the ways in which the system then orients teachers away from learning, because there are so many competing voices, and instructions and explanations of the teacher's day, which will ultimately remove time. So if we are saying that time is an important resource to facilitate the delivery of learning outcomes, this multiple split of who you are and what you're supposed to be doing during the day is constantly determining how much time is ultimately dedicated to a coherent learning process (p. 140 of the interview transcripts; see also Siddiqi, 2022).

Before exploring the norms that emerge from such competing identities, I first describe each of the four domains underlying these norms.

The first of the four domains shaping teacher norms is selves. When it comes to teachers' selves, and particularly to what each teacher may value, a fundamental feature is that teachers—like all humans—have multiple and sometimes competing motivations (see, for example, Kuran, 1997, in economics; Appelbaum et al., 2000, in business management; Ryan and Deci, 2000, in psychology). This is not to imply that motivations are the most important aspect of a teacher's self. The self is intractably complex, in ways that go far beyond the scope of this paper. For simplicity, I focus on motivations an aspect of the self that has an obvious and well-established connection both to teacher norms and to teacher-related policy.

To demonstrate the range of motivations emerging from the interviews, I use a 4-fold classification developed in Hwa and Pritchett (2021). As indicated in Figure 2, this classification comprises two psychosocial sources of motivation—i.e., personal satisfaction and social validation—and two pecuniary sources of motivation—i.e., finances and material circumstances. Across the interviews, there was strong agreement that all four sources of motivation matter for teacher practice and teacher norms. Personal satisfaction and social validation were both mentioned in all 14 interviews as being valued by teachers; finances in 12 of the interviews; and material circumstances in eight. However, the intent here is not to test the degree to which the motivations mentioned by interview interlocutors correspond to these four sources of motivation. Rather, the point is that any given teacher will have a heterogeneous range of “what they value”.

Paying attention to such heterogeneity is crucial for would-be education reformers. This is particularly important in the (many) policy contexts where teacher career reforms tend to emphasize finances over other sources of teacher motivation. It is undoubtedly true that teachers should not have to wait months for their wages (as emphasized by interlocutors Juliet Wajega and Barbara Tournier on p. 225–226 of the interview transcripts). However, it is equally true that, in the words of interlocutor Verónica Cabezas:

We can increase teacher salaries in schools in poor communities by, I don't know, 20 percent, 30 percent—and I'm not sure if that would really change how teachers are distributed. Because it's also about social norms. It's about the culture. It's about where they feel comfortable working. It's about social networks, et cetera, et cetera. So, that's really hard, because in the end you see that it's not about a specific policy, no? It's about how we can change the whole organization to have a school system that can attract and retain good teachers (p. 43 of the interview transcripts).

Similarly, Masooda Bano alluded to the importance of personal satisfaction when discussing religious motivations (e.g., drawing inspiration from the Prophet Muhammad's role as a teacher, p. 156 of the interview transcripts; a point also noted by interlocutor and fellow Pakistani scholar Soufia Siddiqi on p. 145). Bano also emphasized the importance of social validation in discussing “the cultural status and respect in the community which comes from being a good schoolteacher” (p. 156). She observed that “in developing countries, the state and international development institutions lean toward a modern secular discourse about policy, where they think about financial incentives as the main variable to engage with” (p. 158)—when instead a balance between financial incentives and religious/cultural motivations “can enhance your ability to mobilize many more teachers in these countries. But the state and donors just don't have any idea how to do it” (p. 156; see also Bano, 2022b).

Motivations vary not only within individual teachers, but also across the pool of teachers. Besides between-country differences in what teachers value (see “Teacher norms affect policy implementation” above for some examples), there is also motivational variation between teachers in the same education system. Some of this variation stems from differences in policy over time or between different parts of the country. For example, interlocutor Kwame Akyeampong mentioned generational differences among teachers entering the profession at different eras of national and educational development (p. 211), an observation echoed by Luis Crouch in the same interview (p. 212). Soufia Siddiqi mentioned differences between teachers in the Pakistani states of Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, who had been subject to high-stakes and low-stakes accountability structures, respectively (p. 149–150).

Situations, the second domain shaping teacher norms, involve interactions between teachers and the settings they inhabit. Specifically, “situations” pertain to teachers' perceptions of what can be done in their classroom and school contexts. Thus, they do not refer to the objective properties of situations, but rather to individual teachers' subjective perceptions thereof. Put differently, situations fall in the top left of Figure 1, together with other individual-level beliefs and perceptions. The influence of these subjective perceptions on teaching and learning was evident in the interviews. For example, interlocutor Lucy Crehan observed that context-embedded professional development can be key to changing such situational perceptions:

… it's difficult to convince teachers to change their behaviors without changing their beliefs. And one of the sticking points, I think, for teachers hearing about something that's happening somewhere else is, “Yeah, that might work there. But that won't work with my kids. They don't understand my context.” So if you can show them, “Actually, we are working with the very same class that you're teaching, and look what is possible,” then that's such a powerful way to change those teacher beliefs (p. 118–119 of the interview transcripts).

Other interlocutors also mentioned instances where the unusually positive tenor of teachers' and other actors' perceptions facilitated excellent teaching practice in challenging circumstances (see, for example, interlocutor Masooda Bano's description of unusually dedicated teachers in Pakistan, p. 153–154 in the interview transcripts). Beyond the interviews, the pivotal role of perceived opportunities (and perceived constraints) is supported in a range of literatures. These include psychological research on self-efficacy beliefs (Bandura, 1977) and on implicit theories of intelligence (Dweck, 2006). Other relevant bodies of research include behavioral economics work on bounded rationality (e.g., Thaler and Sunstein, 2009) and educational research on asset-based pedagogies (e.g., López, 2017). Further suggestive evidence comes from research suggesting that Vietnam's extraordinary educational achievements, relative to countries with similar economic resources, is due in part to unusually strong commitments to education across diverse actors (London, 2021).

Based on content analysis of the interviews, the range of situational factors affecting teachers' perceptions of “what can be done” can be grouped into five categories, as shown in Figure 2. These categories are: students (mentioned in 11 of the 14 interviews); training, networks, and support (14 interviews); leadership (10 interviews); materials and physical space (10 interviews); and the local community (six interviews). Teachers may perceive the factors in each of these categories as being either enabling—i.e., expanding the range of what can be done in their classrooms and schools—or constraining—i.e., narrowing the range of possibilities. As with selves above, these five categories are intended as illustrations of the range of factors influencing teachers' situations, rather than a definitive taxonomy. The main point here is that situational factors can greatly affect what teachers believe they can do in their classrooms and schools.

While situations relate to what teachers believe can be done, the domain of standards encapsulates what teachers believe should be done, as judged normatively by those in charge. “Those in charge” is an intentionally broad framing because the configuration of actors who hold the most sway over teachers' professional decisions can vary greatly across contexts. For example, Farrand (1988), Müller and Hernández (2010), and Czerniawski (2011) find cross-country differences in the degree to which teachers in several European countries (and, in Farrand's study, Mexico) feel that parents, headteachers, inspectors, and other actors hold agenda-setting influence over their work. As with selves and situations, what matters here is teachers' subjective perspectives of who is in charge and what those in charge want.

As shown in Figure 2, the range of standards that interlocutors mentioned can be loosely categorized into: curriculum and assessment (mentioned in 11 of the 14 interviews); frontline discretion or lack thereof (12 interviews); career, compensation, and appraisal (where meeting or not meeting standards primarily affects individual teachers; 13 interviews); accountability, reporting, and data (where the focus is on the school level or the student level; 11 interviews); and other non-teaching responsibilities (six interviews).

Besides the areas for which those in charge have normative expectations, another important form of variation is whether the standards are formal or informal. Interlocutor Margarita Gómez drew a such a distinction, observing that:

… what we have seen when we study public employees' behaviors is that what matters the most, in general, is the informal norms. Everybody knows what these norms are, but they are not a written down or formalized (p. 93 of the interview transcripts).

Some theories related to this formal-informal distinction emphasize the way in which informal standards become systematized into formal standards as a setting grows increasingly complex. For example, in his society-level analysis of institutional change, North (1990) argues that, “The move, lengthy and uneven, from unwritten traditions and customs to written laws has been unidirectional as we have moved from less to more complex societies …” (p. 46). However, in the area of teachers' lived experiences, the interviews suggest that informal standards are more likely to emerge when formal standards do not adequately serve the priorities of those in charge. These priorities are varied. Examples range from informal standards driven by school leaders' desire for favorable exam results (as related by Maria Teresa Tatto on p. 187 and Juliet Wajega on p. 222) to those driven by politicians' desire to shore up local support (as related by Barbara Tournier on p. 223).

Overall, the picture that emerges from the interlocutors' description is one of excessive and often unattainable expectations placed on teachers. This is further complicated by the fact that the expectations of those in charge are sometimes in tension with what teachers personally value (as discussed above under “Selves: ‘What I value”').

The fourth domain influencing teacher norms is society, or broader influences beyond teachers' immediate perceptions of what they value, what can be done, and what those in charge expect. In this framework, “society” functions as a catch-all category for such contextual influences, both for analytical convenience and because the complexity of human beliefs and behavior means that it is probably impossible (and certainly beyond the ambitions of this study) to catalog all the background characteristics that may influence teacher norms across all educational contexts.

Also for analytical convenience, society does not appear directly in the between-domain overlaps where dominant norms may emerge, as indicated in Figure 2. Instead, society can influence the three domains of teachers' perceptions, which in turn influence whether a particular practice or priority becomes dominant. For example, broader societal influences can affect selves by socializing teachers to pursue certain goals for personal satisfaction, or by determining the activities and outcomes for which they may receive social validation or financial and material compensation. Moreover, societal influences can add weight to various factors in selves, situations, and society—which can tilt the balance toward one norm or another when there are competing factors at play.

More concretely, the paired interviews indicate several channels by which societal factors may influence both teacher norms and the domains shaping these norms. As shown in Figure 2, these channels are: narratives about teachers and education (mentioned in 12 out of the 14 interviews); politics and power dynamics (nine interviews); sociocultural values and customs (12 interviews); social networks and public visibility (which can draw attention toward or away from particular images, narratives, or practices; 12 interviews); economic conditions (eight interviews); and precedent (such as historical precedent or precedent from higher-status frames of reference, like medicine in comparison to teaching or high-ranking education systems in comparison to lower-ranking systems; 13 interviews). As with the other domains, this is not an exhaustive categorization of the channels through which broader societal factors may influence individual perceptions and collective norms. Rather, it is simply a loose grouping of channels that were mentioned during the interviews in this asynchronous symposium.

One noteworthy feature of societal influences on teacher norms is that they are often interconnected. Consider the case of narratives about teachers and education in Indonesia. According to interlocutor Shintia Revina, one dominant narrative is that “being an excellent teacher is second to being a good civil servant.” She added that:

I actually heard teachers mention that they are just the soldiers of the government who are ready to do whatever they're instructed to do. “Just tell me what to do. I'm just a soldier, you know, so I will do whatever government wants me to do. A new curriculum, that's okay, change the curriculum. We will do it as long as it comes from the government” (p. 127 of the interview transcripts).

In addition to the connection between this conception of teacher identity and the political relationship between teachers and the state, Revina identified a link between this narrative and Javanese cultural traditions (i.e., sociocultural values and customs): “… we have this so-called obedience culture. So, what matters to teachers is to follow the regulations as a civil servant. What matters to teachers is to follow the instructions from the MoEC, or the local education agency” (p. 126). While not mentioned during the paired interview, Revina and co-authors have written elsewhere about how the “good teacher = good civil servant” narrative is connected to local job markets (i.e., economic conditions): civil service teaching positions are prized because they imply lifelong financial security (Alifia et al., 2022; see p. 173 in the interview transcripts for a similar observation from Melanie Ehren in the South African context). More broadly, other scholars have observed that local narratives about teachers and education can be closely connected to political dynamics (e.g., Mehta, 2013, on competing interest groups and divergent narratives of teacher professionalization in the U.S.), sociocultural frames (e.g., Li, 2012, on Eastern vs. Western educational ideals), and economic circumstances (e.g., Barrett, 2005, on how low pay undermines Tanzanian teachers' identity as societal role models).

Building on the four domains of underlying factors that influence teacher norms, I now describe the three types of norms that are sustained by different configurations of underlying factors. These three types of norms, as shown in the shaded areas in Figure 2, are: coherence, compromise, and contestation. Each type represents a different way in which teachers may respond to the standards imposed on them.

Norms of coherence are supported by underlying factors across selves, situations, and standards. That is, such norms are aligned with formal and/or informal expectations from those whom teachers regard as being in charge, they are considered to be achievable within teachers' classroom and school situations, and they are related to values or outcomes that teachers care about. Typically, they are also supported by broader societal factors. With such alignment of supporting factors across the four domains, coherent norms can be highly resilient to change—perhaps even more so than compromise or contestation norms, as will be discussed below in “Opportunities for changing teacher norms”. The term “coherence” here draws on Pritchett's (2015) conceptualization of coherence within and between accountability relationships in education systems.

Norms of compromise are aligned with formal and/or informal expectations of those in charge (standards)—at least on the surface. Teachers feel compelled to abide by these expectations, whether because these expectations are aligned with what they intrinsically value in their jobs or for the sake of social, professional, or material wellbeing (selves). However, they do not believe that the goal or task in question can be meaningfully realized in their classrooms and schools (situations). Accordingly, they are likely to compromise by partially fulfilling the expectation, such as completing those aspects of the expectation that are administratively monitored. Societal factors are likely to strengthen the pressure to fulfill the standard, and/or to legitimize the decision to compromise with partial fulfillment. Such norms of compromise can emerge for a range of reasons, including impossible demands that prompt people to self-defensively adopt reductive attitudes toward their responsibilities (Zacka, 2017; see also Hood, 2010, on avoiding blame through protocolization), informational constraints that keep individuals in the un-blissful ignorance that many others share their private disagreement with publicly visible norms (Bicchieri, 2017, on pluralistic ignorance; Kuran, 1997, on preference falsification), or the institutionalization of practices that boost legitimacy without improving quality (Meyer and Rowan, 1977; Pritchett et al., 2013, on isomorphic mimicry).

Norms of contestation emerge when teachers do not value a certain standard and, accordingly, they practice or prioritize something other than what the standard expects. Depending on the underlying factor(s) in teachers' selves, contestation norms can include both norms that are altruistic (going above and beyond a standard) and those that are self-serving (harmfully breaching a standard). In either case, the practice or priority in question is seen as being possible in teachers' situations, whether because of available resources for going beyond the call of duty or because of leeway for getting away with lapses. Typically, such practices or priorities are also seen as being affirmed by society, perhaps because of certain images of the ideal teacher or certain attitudes toward government resources. Given the competing expectations that teachers contend with (see “Teacher norms are shaped by competing expectations”), a contestation norm that falls outside a certain standard may be supported by a rival standard—such as a practice that is officially proscribed but informally condoned, or a priority that is disregarded in performance evaluations but promoted by district officials.

Before I turn to concrete examples from the interview transcripts, three points about these types of norms are worth noting. First, teacher agency is central to this analysis. As noted above, these three types of norms represent three different choices that teachers can make in response to top-down standards. Moreover, the subjective perceptions of teachers (and those around them) are pivotal to which type of norm emerges. Second, given that the norms are framed in terms of teachers' subjective responses to standards, they are neutral as to whether these norms benefit or harm students. Norms of all three types can be either “desirable” or “undesirable.” Third, a norm may represent dominant beliefs among most teachers in a geographic/administrative setting or among a subgroup thereof. This is reflected in the working definition in this study of teacher norms as “dominant beliefs among teachers about the most suitable practices or priorities in their contexts”—teachers may regard only certain like-minded peers as constituting the salient context for the norms that they care about. For example, in describing certain teachers' voluntary wraparound support for academically promising students in the broader context of low-performing state schools in Pakistan—a contestation norm of going beyond the call of duty—interlocutor Masooda Bano observed that these highly motivated teachers have their own “counterculture against the school culture” (p. 154 in the interview transcripts; see also Bano, 2022c).

The next phase in exploring the research question—“How do the factors underlying teacher norms affect opportunities for changing those norms that hinder children's learning?”—involves analyzing interview interlocutors' descriptions of such teacher norms. I focus on norms that have immediate effects on teaching and learning in the classroom, setting aside those norms that may have powerful effects but are further upstream (e.g., norms around the extent to which novice teachers are mentored by experienced colleagues, unless the interlocutor made a direct link from this norm to teaching and learning processes).

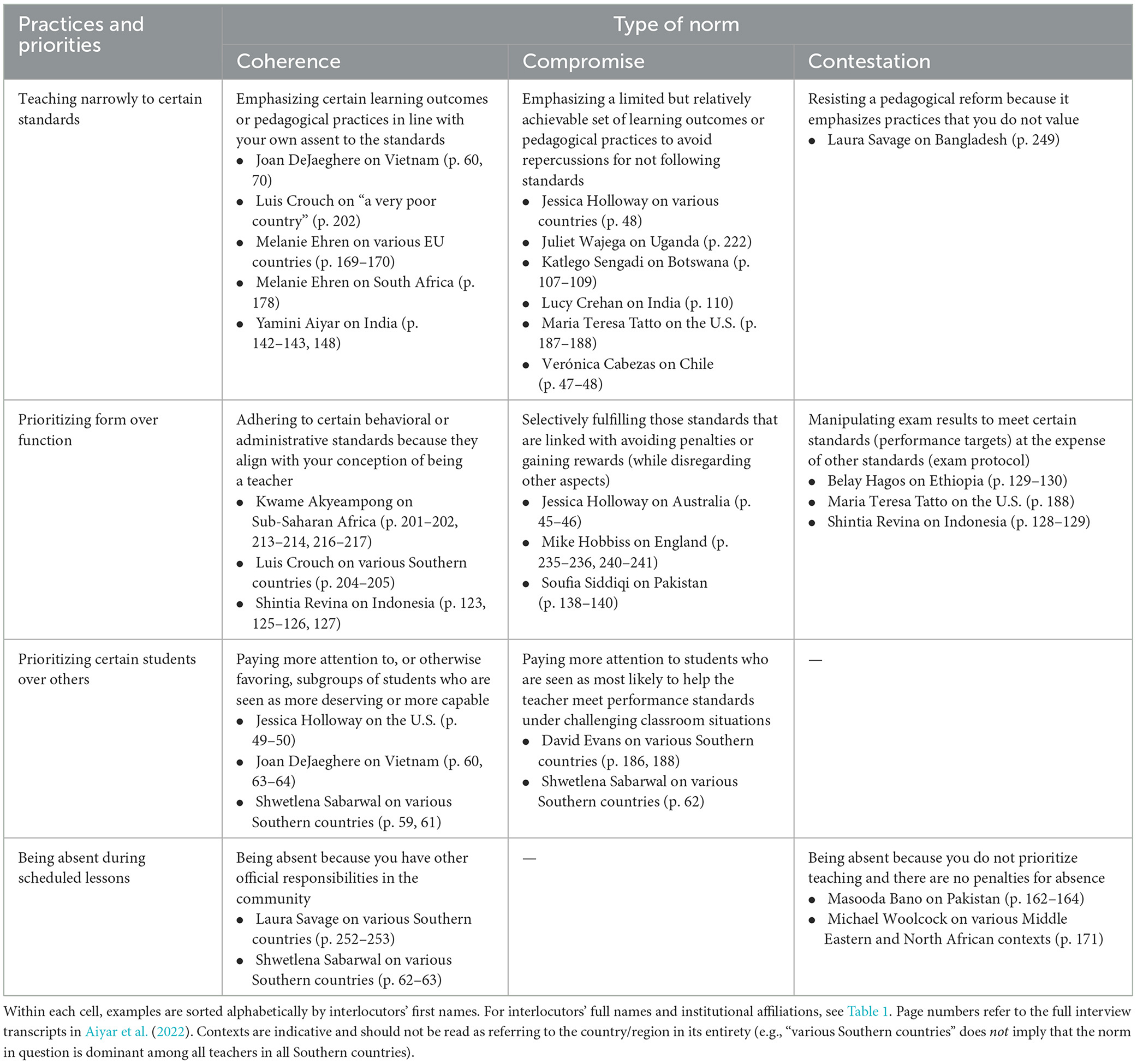

I identified 30 such norms across 20 interlocutors (incorporating a total of 38 text segments because some norms were mentioned repeatedly throughout the interview). Because I focused on empirically rooted examples rather than hypotheticals or general reflections, the distribution of identified norms across interlocutors is uneven, reflecting differences in both experience and speaking style. To better understand these norms, I categorized them by type of norm (coherence, compromise, contestation) and by loose groupings of the practice or priority in question (teaching narrowly to certain standards, prioritizing form over function, prioritizing certain students over others, and being absent during scheduled lessons). This is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Examples of teacher norms that can hinder children's learning in the classroom, by the practice or priority in question and the type of norm.

As shown in Table 2, norms that detract from children's learning can emerge in any of the three types. Across the interviews, the interlocutors described all three types among norms of teaching narrowly to certain standards and of prioritizing form over function. For norms of prioritizing certain students over others, interlocutors described coherent norms in which certain students are seen as more deserving or more capable and compromise norms in which certain students are seen as more likely to help teachers achieve performance targets. Although interlocutors did not offer any empirical examples of prioritizing certain students over others as a contestation norm, such a norm is conceivable—perhaps with teachers voluntarily exceeding their mandated hours to offer extra coaching to particularly disadvantaged children. Similarly, interlocutors did not offer empirical examples of being absent during scheduled lessons as a compromise norm, but such a compromise is certainly conceivable in the face of impossibly competing standards.2

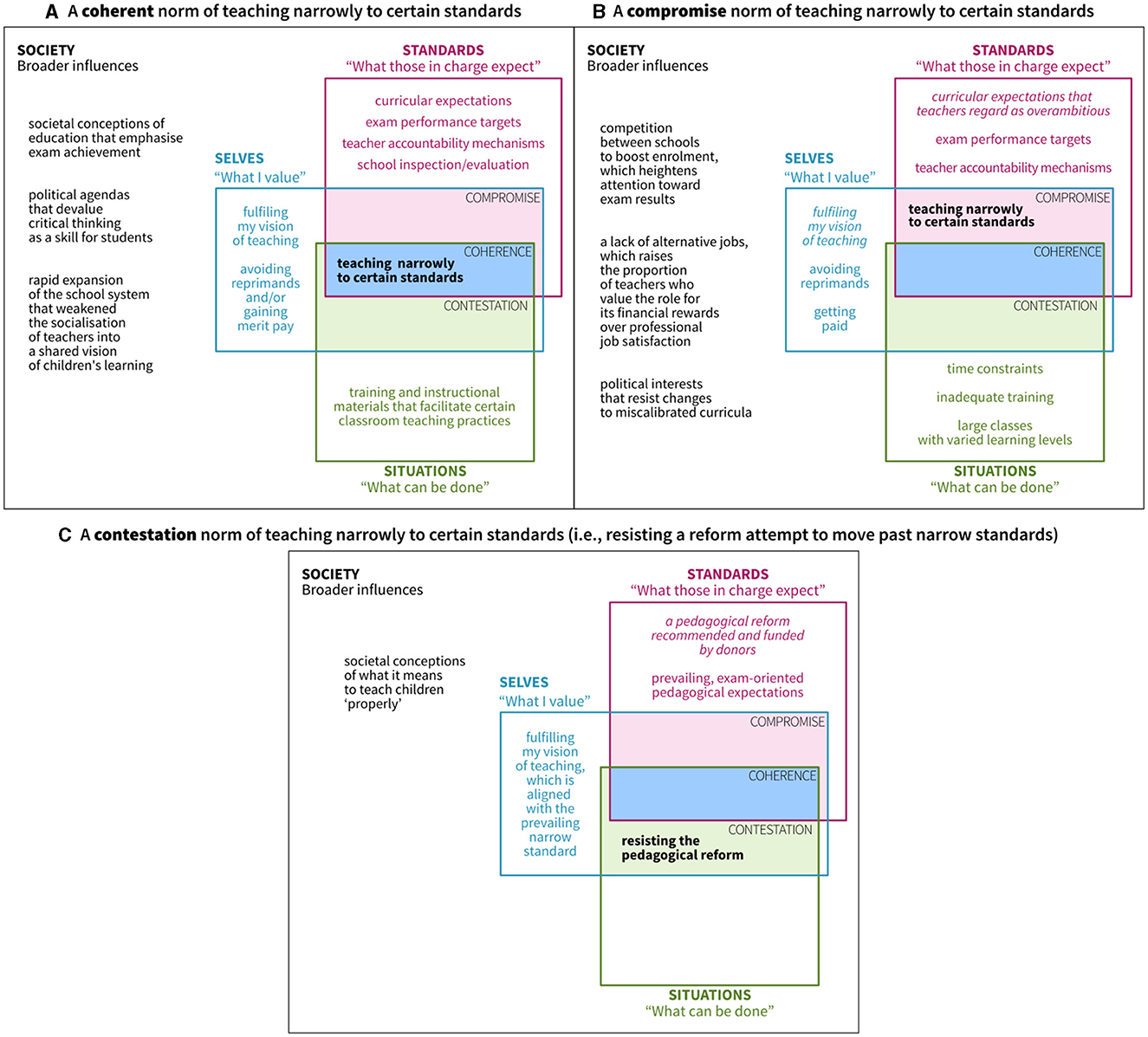

To further explore the differences between the three types of norms, I now discuss each type using examples of norms of teaching narrowly to certain standards. These example norms and their underlying factors are summarized in Figure 3. The figure draws on five examples of coherent norms, six examples of compromise norms, and one example of a contestation norm, as listed in the first row of Table 2.

Figure 3. Examples of coherence, compromise, and contestation in norms of teaching narrowly to certain standards, with underlying factors identified by interview interlocutors. (A) A coherent norm of teaching narrowly to certain standards. (B) A compromise norm of teaching narrowly to certain standards. (C) A contestation norm of teaching narrowly to certain standards (i.e., resisting a reform attempt to move past narrow standards). The underlying factors shown in these figures are derived from descriptions by the interview interlocutors. For the interlocutors and interview segments informing each part of the figure, see Table 2. Italicized text indicates underlying factors that run counter to the norm in question.

To begin with an example of a coherent norm of teaching narrowly to certain standards, interlocutor Yamini Aiyar described what she called the “classroom consensus” in the Indian context:

There's a social conditioning in which we all operate. And that social conditioning prioritizes examination marks—that is how we judge the school, that is how the teacher is also judging the school. …

These are the norms that shape how the teacher is approaching the classroom. And in those norms, the teacher in government schools is not approaching the classroom divorced from the school administration or from the government context in which the teacher is located. And in that government context where performance is determined by your ability to meet the checklist, then pass percentages, examinations, and syllabus completion become the only metrics that you will consider as relevant to performance. Therefore, you reduce the purpose of teaching just to those metrics (pp. 142–143 in the interview transcripts).

This illustrates the fact that coherent norms are supported by underlying factors in multiple domains, such as standards (exams and exam-related government checklists) and selves (teachers define “the purpose of teaching” by exam-based metrics). This norm of narrow, exam-oriented teaching is reinforced by broader societal narratives about what good education is (“that social conditioning prioritizes exam marks”). Later in the interview, Aiyar observed that attempts to change this norm are “not an automatic shift,” partly because teachers “are stymied by not being able to identify what's the best approach” (p. 148). This suggests further reinforcement of the norm from situations, in that teachers' understandings of what can be done in their situations is constrained by training and experience that have been similarly oriented toward exam achievement.

While compromise norms share some characteristics with coherent norms, they differ in that teachers do not believe it is possible to fully realize the given standard in their situations. Interlocutor Juliet Wajega experienced such a compromise norm as a teacher in Uganda:

I was teaching science—chemistry and biology—and this was in a private school. And of course for private schools there is this sense of competition, where you must show results and students must pass so that they're able to attract more students to join their school. In that school, they would really expect you to teach and complete the syllabus, and to go through all the test questions within a very short time …

… this will affect your classroom planning and your teaching. You are just expected to complete the syllabus, regardless of what the learners need, so you ignore other aspects of learning. And then, also, because you must make sure that your students pass, it's hard to have your own vision as a teacher. You are always under some pressure from the administration. So it affects your practice as a teacher. It affects your professional ethics. You may want to do something visionary, but you're under pressure. And, of course, it also affects the students—you don't allow them to be innovative because you're just not giving them enough time. And all of this is something that I saw as being not very right (p. 222 in the interview transcripts).

In Juliet's account, the standard of completing the syllabus and raising pass rates was not fully achievable because of the situational time constraints. Accordingly, she compromised by “just … complet[ing] the syllabus … and ignor[ing] other aspects of learning.” Unlike coherent norms, where teachers mostly concur with the standard in question, compromise norms often align with something that teachers' selves value—such as relieving “pressure from the administration”—while diverging from other valued elements—such as their “own vision as teacher.” However, the compromise prevails. In some cases, the compromise norm is supported by societal factors, such as educational markets that lead to competition between private schools.

Finally, in an example of a contestation norm of teaching narrowly to a certain standard, interlocutor Laura Savage describes an attempt in Bangladesh to implement a program based on Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL). Although the TaRL approach has successfully cultivated children's literacy and numeracy in multiple contexts, it was resisted by teachers here:

… there was an effort to roll out a program based on TaRL. We, as the donors, had recommended it; the government had gone along with it as part of a results-based financing loan. … it was an utter failure. It made absolutely no progress whatsoever. …

A lot of it came down to expectations from both teachers and parents about the style of teaching. This was in a context where BRAC has been an incredibly successful NGO, so we thought that people might understand this new program because it was similar to the kinds of approaches that BRAC were taking in the early years. But what we hadn't quite appreciated—although note that this is not substantiated with systematic data—is that the expectation was that once a child had graduated out of a BRAC accelerated learning program or early childhood program, then they would go to school and learn “properly”. And the idea that teachers might break children into groups with different ability levels or not pursue rote learning to the test was just unacceptable—firstly to teachers, who were worried that these incredibly new expectations were going entirely against everything that they had been given to believe was the approach that you should take to teaching. And it was unacceptable to parents, who were saying, “We're not going to get anything out of this program, because you're not teaching our children properly” (p. 249 in the interview transcripts).

In this case, a prior norm of “pursu[ing] rote learning to the test” meant that the new donor-driven, government-endorsed pedagogical standard faced contestation rather than compliance. The new standard fell outside of what was valued by teachers' selves—it was “just unacceptable,” misaligned with the forms of teaching from which they derived personal satisfaction. Additionally, it was also unacceptable to at least part of society: parents, who did not view it as a “proper” approach to teaching.

Although Savage's description of this contestation norm did not include underlying factors in teachers' situations, it does offer another reminder that the contextual factors salient to teacher norms go beyond what is “objectively” present in a given setting. Teachers in this geographic context were familiar with pedagogical approaches similar to the donor-supported reform, yet such approaches were not seen as suitable for the schooling context in which the reform was introduced. Such subjectivity in teachers' perceptions of what is relevant to their contexts can hinder attempts to reform education systems for student learning. However, as I discuss below, subjective perceptions can also offer opportunities for change.

Diagnosis precedes effective treatment. Accordingly, if a teacher norm is hindering children's learning in a given context, any attempts to change that norm will have a much better chance of success if they are rooted in an understanding of the underlying factors and the general type of the norm in question (see also Silberstein and Spivack, 2023). In this section, I first illustrate why such diagnosis matters and then offer suggestive evidence on entry points for changing each type of norm.

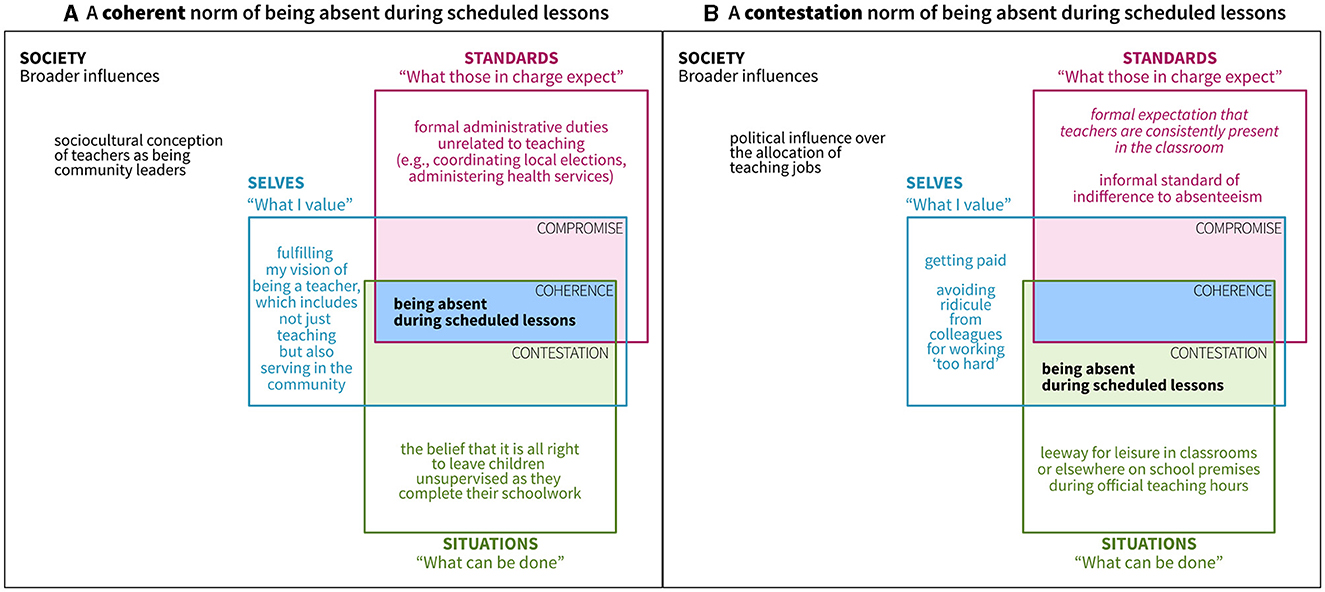

To demonstrate why diagnosing the type of norm matters, consider the norm of being absent during scheduled lessons. The interview transcripts included four examples of such a norm, two of which were coherent norms and two of which were contestation norms. These examples are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Examples of coherence and contestation in norms of being absent during scheduled lessons, with underlying factors identified by interview interlocutors. (A) A coherent norm of being absent during scheduled lessons. (B) A contestation norm of being absent during scheduled lessons. The underlying factors shown in these figures are derived from descriptions by the interview interlocutors. For the interlocutors and interview segments informing each part of the figure, see Table 2. Italicized text indicates underlying factors that run counter to the norm in question.

One example of a coherent norm of such teacher absenteeism came from interlocutor Shwetlena Sabarwal, discussing a nine-country survey of teacher mindsets that she conducted (Sabarwal et al., 2022):

… a teacher is more than a teacher, but also a community leader. The teacher is often the only educated community focal person, so the teacher goes on election duty, does public health services, they were enrolled for the COVID response in a lot of places—so it's seen as completely fine for the teacher to be absent from school, because they have many more important things to do than just teach. And it's completely okay to leave children unsupervised with class work to do, and so on (pp. 62–63 in the interview transcripts).

That is, being absent from the classroom under certain circumstances is entirely coherent with standards that include non-teaching community duties, and conceptions of being a teacher both in society and in teachers' selves that prioritize such duties, and the perception that it is acceptable to leave children unsupervised in such situations.

In contrast, interlocutor Masooda Bano's description of “a pervasive anti-work culture” in some state schools in Pakistan hinged instead on an informal but widespread contestation of formal standards:

… the state bureaucracy is so perverse, in a way, that the mindset is, “I'm getting my salary, but why work?” So a lot of these teachers and principals will sit there drinking tea or having long conversations, rather than being in the class. And they'll ridicule the teachers who want to teach, “Why are you working? These children are from poor backgrounds, they won't learn anyway.” Or, “Why are you trying to be so efficient?” … It's a culture where you find teachers asking students to make tea for them, to massage their feet. …

It's also linked to a context where a lot of teaching appointments are still awarded on political grounds, and so a lot of teachers are not recruited on basis of their competence or their commitment or their ability to be a good teacher. These are state government positions that the politicians can grant as a favor to their constituencies (pp. 162–163 in the interview transcripts).

Despite the universal formal standard of showing up for work, teachers instead adhere to the widespread informal standard of indifference to one's work. This is enabled by classroom and school situations that not only support such negligence but also “ridicule” conscientiousness. The contestation norm is also supported by the societal factor of a politicized recruitment pipeline that yields a pool of teachers whose selves place little value on the craft of teaching.

As shown in Figure 4, despite some outward similarity in behavioral patterns, coherent norms and contestation norms of being absent from the classroom during scheduled lessons differ considerably. These differences may affect efforts to change these norms. For example, interlocutor Bano observed the contestation norm described above when studying public schools in Pakistan that improved under the management of an education foundation called CARE. This foundation had boosted student learning the 850 government schools under its management “by introducing a certain level of accountability, by doing school visits, by providing a teacher of their own who keeps an eye on the other teachers and motivates them through goodwill to start working” (Bano, p. 164 in the interview transcripts). In terms of accountability, Bano notes in her study that there is “a long list of overall school-operating rules that CARE enforces … [in which] the focus is not on training teachers to use new or innovative teaching methodologies, but to ensure that they do the basic stuff regularly” (Bano, 2022a, p. 11). Thus, the CARE approach concurrently reinforces formal standards through such operational rules, reduces leeway for negligence in situations through formal monitoring by CARE senior management, and influences teachers' selves through the motivational influence of in-school CARE teachers. This has proven successful in changing such “anti-work” contestation norms at the school level (albeit with mixed success at the district level, as discussed below).

However, if such an approach were applied to the case of a coherent norm of being absent from the classroom, where such absence is formally mandated as a competing duty, its effects would probably have been minimal—or even detrimental. Whereas the contestation norm that Bano described emerged from teachers not valuing the formal standards, teachers' willingness to abide by formal standards was not the issue in the coherent norm that Sabarwal described. Rather, the root of the problem was that formal standards (and associated values in selves and society) did not prioritize classroom teaching and learning. If additional anti-absenteeism rules and social pressure to abide by these rules were to be introduced into contexts with coherent norms of performing other official duties during school hours, this would likely result in compromise norms such as superficial fulfillment of the out-of-school responsibilities or token demonstrations of teacher presence in the classroom. Instead, the coherent norm of teacher absence would be better addressed by reducing or rescheduling those non-teaching duties (coupled with other changes that are coherent with the new prioritization). Yet such a reduction of non-teaching duties would have made little difference to teacher absenteeism in settings with “anti-work” contestation norms. The key point here is that even for the same behavioral pattern, different types of norms need different approaches to reform.

Having demonstrated that different configurations of underlying factors can lead to different types of norms that are sustained and changed in different ways, I now turn to suggestive evidence on what opportunities for change might look like for each type of norm. As noted in the methods section, this part of the analysis draws on empirical examples of successful and unsuccessful attempts to reform teacher norms toward improvements in student learning. However, as there were only 13 such examples in the interviews (some of which did not include sufficiently detailed descriptions of the pre-existing norm to determine its type with certainty), this part of the analysis is more speculative than the preceding sections. To supplement these examples, I have also drawn on several other ideas and principles for change offered by the interview interlocutors.

This suggestive evidence on opportunities for change is summarized in Table 3. I will first propose type-specific opportunities for changing teacher norms by influencing selves, situations, and standards, before discussing cross-cutting opportunities in the domain of society.

Out of the 13 empirical examples of attempts to change teacher norms, nine addressed coherent norms (based on my best judgement of the available detail). Collectively, these examples offer a clear lesson: to reorient coherent norms, work to influence multiple domains concurrently, and be willing to adapt along the way. This lesson was consistent across the four successful and five unsuccessful reform attempts. The unsuccessful attempts all offered involved changes in one domain—either changes in standards or attempts to change situations via teacher professional development—that could not overcome the mutually reinforcing influence of factors in the other domains (such as the attempt to change pedagogical standards in Bangladesh, summarized above in Figure 3). In contrast, the successful reforms all intervened in multiple domains. This was true both in examples of systemwide reforms (Yamini Aiyar on p. 148–149 and David Evans on p. 195–196 in the interview transcripts) and in examples of professional development approaches for changing classroom practice (Maria Teresa Tatto on p. 196 and Mike Hobbiss on p. 244–245 in the interview transcripts; see also Hobbiss et al., 2021).

For compromise norms, interlocutor Katlego Sengadi gave a detailed account of compromise norms of teaching narrowly toward exam results and syllabus completion from her experience as a teacher in Botswana (p. 107–109 in the interview transcripts)—along with an example of how pedagogical techniques from the Teaching at the Right Level approach have helped teachers in this context to move beyond “standing in front of the students and just bombarding them with information” toward “actually going down to their level and interacting with them” (p. 118). Similarly, three other interlocutors emphasized (albeit without specific empirical examples) the power of demonstration effects in changing teachers' understandings of what can be done in their classroom and school situations. Besides situations, four interlocutors observed that many education systems maintain extensive standards for teacher accountability and related areas that aim, in the words of interlocutor Dan Honig, to “minimize the damage of the worst actor, but it does so at the cost of preventing better actors from doing things that would be good” (p. 83 in the interview transcripts). Hence, another entry point for changing compromise norms would be streamlining standards, such that there is greater coherence between standards and situations. Beyond the interview transcripts, a reform to streamline curricular standards in grades 1 and 2 in Tanzania led to significant improvements in children's mastery of foundational literacy and numeracy skills (Rodriguez-Segura and Mbiti, 2022).

For contestation norms, entry points for shifting the norm toward cultivating children's learning may differ depending on whether the norm in question is a harmful contestation of a learning-oriented standard or a learning-oriented contestation of harmful standard. The two empirical examples of contestation-related reform attempts in the interview transcripts are both cautionary tales of attempts to diffuse positive practice throughout the system that were quashed by top-down standards. Specifically, Masooda Bano observed that district education offices often reassert control over schools that had been improved by the CARE approach (p. 163–164 in the interview transcripts); and Sharath Jeevan described instances in which a ministerial directive disrupted collegial teacher networks supported by STiR Education (p. 80–81). This indicates that one entry point would be altering standards to formally affirm and protect desirable teacher practices, such that they move from being contestation norms toward more widespread coherent norms (see also remarks from Soufia Siddiqi on p. 146–147). Beyond the interview transcripts, recent educational interventions suggest that harmful contestation norms can, in turn, be shifted by using standards and/or situational factors to remove leeway for misconduct (see Berkhout et al., 2020; Singh, 2020, on reducing exam cheating; Gaduh et al., 2021; Hwa et al., 2022, on reducing teacher absenteeism). As for teachers' selves, several interview interlocutors suggested (although without identifying particular reform attempts) that some combination of teacher career reforms, peer networks, and demonstration effects could shift the balance toward either increasing the proportion of teachers who beneficially contest top-down standards by going above and beyond them, or reducing the proportion of teachers who harmfully contest formal learning-oriented standards (see also Bicchieri, 2017, on trendsetters who contravene and eventually change social norms).

Finally, the interviews also offered insights on reorienting teacher norms via the broader domain of society. Verónica Cabezas gave the specific example of Elige Educar, a Chilean organization that has changed societal narratives about the teaching profession through a blend of public recognition, media campaigns, and direct messaging to secondary school leavers who are choosing their career paths (see p. 52–54 in the interview transcripts). Other interlocutors spoke about opportunities for changing such narratives by aligning formal articulations of the purpose of teaching with existing sociocultural ideals.

Teacher norms—dominant beliefs among teachers about the most suitable practices and priorities in their contexts—profoundly shape teacher practice and, by extension, children's educational experiences. As shown in this paper, dominant and often informal norms can inadvertently orient teachers' daily choices and actions away from the purpose of cultivating their students' capabilities. Such norms include completing the delivery of an overcrowded curriculum whether or not children master its content, prioritizing exam scores over children's present and future wellbeing, and putting administrative reporting and other non-teaching tasks ahead of core instructional duties.

To deepen the current understanding of how to move past such detrimental norms, in this paper I have asked the question of: How do the factors underlying teacher norms affect opportunities for changing those norms that hinder children's learning? My argument has proceeded in three parts.

First, teacher norms are underpinned by varied configurations of factors across the four domains of teachers' selves (“what I value”), situations (“what can be done”), standards (“what those in charge expect”), and society (broader influences). This aligns with prior observations of competing and often impossibly numerous expectations that shape the lived experiences of teachers (Broadfoot et al., 2006; Ball et al., 2012) and of street-level bureaucrats more generally (Lipsky, 2010 [1980]; Zacka, 2017).