- Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands

As a growing number of Dutch higher education institutions become increasingly interested and active in university–community engagement, questions have arisen about their motivations, goals, and activities in this area. This paper aims to provide insight into the factors driving universities’ community engagement and how this is manifested in the Netherlands, considering, in particular, the role of marketization and corporate social responsibility. It thus offers an empirical foundation for understanding university–community engagement. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with major stakeholders in university–community engagement at four Dutch universities, including members of the executive boards. It was found that university–community engagement shows several similarities to corporate social responsibility and is based on a complex mix of value-driven, performance-driven, and reaction-driven motivations. Three relationships between marketization and university–community engagement are identified, characterizing university–community engagement as a counteraction against marketization, an expression of marketization, and a result of marketization.

1 Introduction

Universities across the world are becoming increasingly interested and active in fighting social inequality, restoring trust, and strengthening social cohesion at a local level (e.g., Dempsey, 2010; Grau et al., 2017; Farnell, 2020). These universities aim to engage with and provide benefits to the communities in which they are located using activities such as service-based learning, participatory research, and student volunteering (e.g., Weerts and Sandmann, 2008, 2010; Humphrey, 2013; Goddard et al., 2016). This phenomenon, known in the academic literature as “university–community engagement,” “local engagement,” “community outreach,” or “community–university partnership,” is receiving ever more attention from policymakers and academics. Interestingly, this increase in attention to the local societal contribution of universities is taking place at a time when universities are also expected, more than ever, to have a global impact through their activities in research and education (Goddard et al., 2016; see also Atakan and Eker, 2007). The latter focus is a product of the growing influence of marketization on higher education as declining public investment causes universities “to rely on market discourse and managerial approaches in order to demonstrate responsiveness to economic exigencies” (Gumport, 2000, 1).

As a result of the increasing globalization and marketization of higher education institutions, many such institutions have seemingly become detached from their local surroundings (Ostrander, 2004; Dempsey, 2010; Goddard et al., 2016; Benneworth et al., 2018; Farnell, 2020). This may reduce universities’ (perceived) contribution at a local level, an effect that has led to a growing demand for evidence of their societal impact and contribution to the public good. Standards of accountability and corporate social responsibility (CSR), familiar in the world of business, are thus increasingly applied to universities (Hemsley-Brown and Oplatka, 2006; Albertyn and Daniels, 2009). Following the global trend of enacting university–community engagement initiatives, a growing number of Dutch universities now include societal engagement in their mission statements and strategic plans (see, e.g., Van der Meulen et al., 2019). This fairly recent and seemingly sudden interest in the topic may be based on a deliberate calculation. Since many university–community engagement initiatives existed before the concept gained such attention among Dutch universities, however, the question arises of whether university–community engagement truly constitutes an expansion or alteration of universities’ activities or only a matter of (re)framing (Bruning et al., 2006; Mtawa et al., 2016).

So far, conclusions regarding the motivations of universities for university–community engagement have been somewhat ambivalent (see, e.g., Albertyn and Daniels, 2009; Dempsey, 2010; Benneworth et al., 2018). In particular, empirical research on the motives of universities for such engagement is lacking. Furthermore, the academic literature on the topic is dominated by Anglo-Saxon perspectives and studies reflecting the situation in the United States and the United Kingdom, with a lack of insights from other countries, particularly those in northwestern Europe. The state-of-the-art review conducted by Benneworth et al. (2018) shows that the discussion has been ongoing for quite some time and that it is broadening to include other countries; however, this review also observes the lack of progress in the debate over the past 35 years (Benneworth et al., 2018, 12). This applies particularly to the Netherlands.

This paper aims, therefore, to gain a deeper understanding of the factors driving universities’ community engagement and how this is manifested in the Netherlands. Specifically, it explores to what extent the motivations, goals, and activities of Dutch universities with regard to university–community engagement are related to marketization, seeking to answer the following research question: To what extent does the marketization of higher education play a role in university–community engagement among Dutch universities? The paper compares insights from four Dutch universities: the Delft University of Technology (TU Delft), Utrecht University (UU), the Erasmus University Rotterdam (EUR), and the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VU). These universities were selected on the basis of their level of involvement in university–community engagement, their type, and their location. The data were collected through semi-structured interviews conducted with major stakeholders in university–community engagement at each university, including members of the executive board. The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides theoretical background on university–community engagement, marketization, and CSR. Section 3 sets out the methods used, and section 4 presents the results. Finally, sections 5 and 6 offer a discussion of the findings and conclusions based on this discussion.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 University–community engagement

Universities have three main roles: research, teaching, and the “third mission,” with the last of these also known as service, valorization, or knowledge transfer. Over the last few years, the term “university–community engagement” has been gaining currency among Dutch universities. This concept can be defined in many ways, most of which consist of spatial, reciprocal, developmental, or instrumental aspects or a combination thereof (Benneworth et al., 2018; Farnell, 2020; Koekkoek et al., 2021). For the purposes of this paper, we define university–community engagement as the activities conducted by universities to address societal needs through mutually beneficial partnerships with their local (external) communities. “Communities” in this context include civil society, public authorities, businesses, other knowledge institutions, and cultural organizations. Activities can be carried out by students or university staff and can form part of teaching, research, or university governance and management.

This broad definition results in the inclusion of various activities: for example, offering lifelong learning opportunities, volunteerism, service-based learning, participatory research, knowledge exchange, cultural and educational events, and providing access to university buildings for others to use (see, e.g., Humphrey, 2013; Goddard et al., 2016). In academic literature, university–community engagement is also known as “civic engagement,” “community outreach,” “community–university partnerships,” and the “scholarship of engagement” (Sandmann, 2008; Weerts and Sandmann, 2008, 2010; Hart and Northmore, 2011). Notably, the terminology used by authors differs greatly between disciplines (Giles, 2008). The motives of universities for university–community engagement often include a combination of intrinsic beliefs and external pressures (Albertyn and Daniels, 2009; Dempsey, 2010). Universities that feel an intrinsic motivation to engage with the community view this as a moral obligation and an essential aspect of universities, based on ideological stances or religious beliefs (Benneworth et al., 2008; Farrar and Taylor, 2009; Goddard et al., 2016). The increasing interest in university–community engagement can also be ascribed, however, to external influences, which have shifted rapidly over the last three decades (Fisher et al., 2004; Furco, 2010). Economic, political, and social changes such as the growth of the knowledge society and globalization impact “the universities’ mission, organisation and profile, the mode of operation and delivery of higher education” (Vasilescu et al., 2010, 4,179). In this paper, we focus specifically on the growing influence of marketization on higher education institutions (Benneworth et al., 2008, 2018; Albertyn and Daniels, 2009; Koekkoek et al., 2021).

2.2 Marketization

Neoliberal policies in the public sector, also known as New Public Management, have introduced corporate and market principles to the running of public institutions (Van Schalkwyk and De Lange, 2018). The aim of this is to stimulate such institutions, including universities, to innovate (Benneworth, 2013b) and focus on competition “as a way of increasing productivity, accountability and control” (Olssen and Peters, 2005, 326). This shift in focus is accompanied by changes in funding, targets, benchmarking, measurable outputs, and performance criteria (Olssen and Peters, 2005).

A visible manifestation of the marketization of higher education is the rise of league tables consisting of a range of indicators of institutional performance. Their purpose is to offer student–consumers a more informed choice and give universities a tool with which to compete with one another; “this will help to allow the market mechanism to reward success” (Benneworth, 2013b, 312). In addition to this effect, several authors have argued that the majority of universities now focus on collaboration with large corporations as a result of cuts to public funding (e.g., Olssen and Peters, 2005; Goddard et al., 2016). Furthermore, various stakeholders, such as policymakers and political parties, increasingly ask for evidence of universities’ societal impact (Benneworth et al., 2008; Hart and Northmore, 2011; Van Schalkwyk and De Lange, 2018).

Marketization and university–community engagement may seem incompatible concepts, with the former promoting a more self-serving form of the latter than that presented by the traditional image (Van Schalkwyk and De Lange, 2018). University–community engagement is, moreover, difficult to represent in league tables (Benneworth and Humphrey, 2013). It can even function as a protest against marketization by offering “alternatives to measuring the value of a university education by students’ future economic success” (Ostrander, 2004, 77). The concept of CSR, however, may offer a new perspective on the relationship between university–community engagement and marketization. Similar to that of universities, the role of corporations has been subject to debate for many decades, with many commentators arguing that corporations have broader responsibilities than simply striving for maximum profit (Carroll, 1991; Nejati et al., 2011). In response, many corporations have adopted CSR programs through which they aim to contribute to society in a responsible and ethical way, addressing social and environmental concerns (Vasilescu et al., 2010).

2.3 CSR

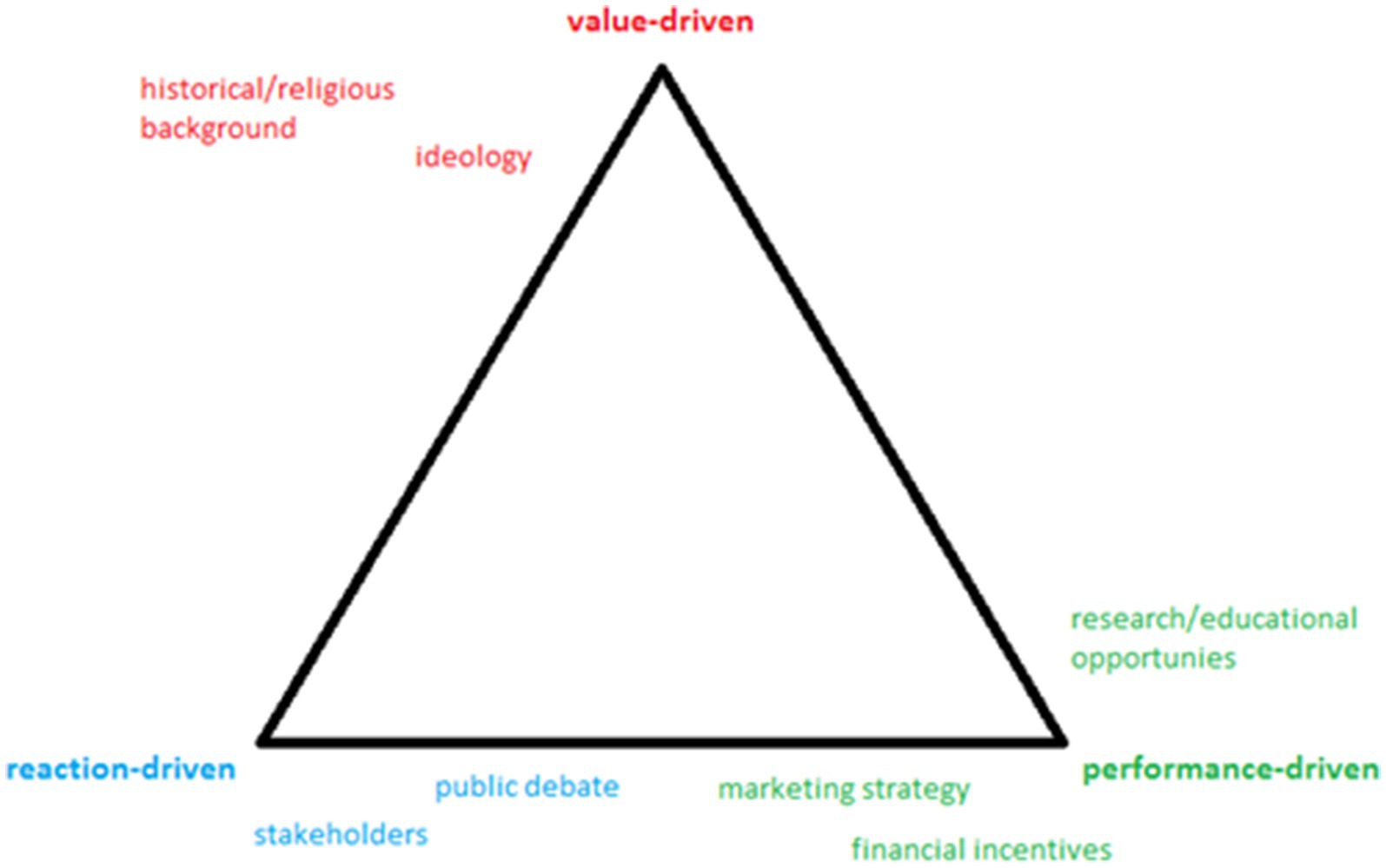

Conceptually, there is some resemblance between CSR and university–community engagement: Both are related to public values and the public interest, offer a means of contributing to the public good, and entail a voluntary behavioral aspect (Brammer et al., 2012; Hayter and Cahoy, 2018). Similar to university–community engagement, various motivations drive corporations to pursue CSR. Three types of motivations can be distinguished: reaction-driven, value-driven, and performance-driven (Maignan and Ralston, 2002; Fassin and Buelens, 2011). The three often blur together, and most corporations’ motivations consist of a combination of two or all three (Fassin and Buelens, 2011).

Reaction-driven motivation originates from both internal and external expectations and demands from stakeholders. Customers, for example, have become increasingly intolerant of corporate practices that harm the environment or disregard human rights (Brønn and Vidaver-Cohen, 2009). Pressure to engage in CSR can also come from the corporate community itself: For instance, studies have shown that managers feel more compelled to donate to charitable causes when philanthropy is promoted among their peers (Brønn and Vidaver-Cohen, 2009). These pressures are often—though not exclusively—experienced as obligations.

Value-driven motivation is based on intrinsic personal values and ethics and “the desire to make a positive contribution to society’s future” (Brønn and Vidaver-Cohen, 2009, 95). Drivers of this type are more positive, often experienced as voluntary, and, when taken seriously, affect the core business and strategies of the firm in various ways (Brønn and Vidaver-Cohen, 2009; Fassin and Buelens, 2011).

Finally, performance-driven motivation is based on instrumental drivers, such as marketing and financial considerations (Fassin and Buelens, 2011). The major purpose of CSR driven by this type of motivation is to improve the reputation of the company and protect or increase profit levels (Brønn and Vidaver-Cohen, 2009). A corporation’s reputation represents an important competitive advantage. It reflects the organization’s strategy, culture, and values—its corporate identity (Atakan and Eker, 2007)—and depends heavily on the perceptions of consumers. CSR actions may improve these perceptions and, consequently, the company’s reputation. Several studies have shown a positive association between CSR behavior, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty (Antonaras et al., 2018).

2.4 University–community engagement and CSR

Like companies, universities compete with one another and seek a competitive advantage (Atakan and Eker, 2007; Goddard et al., 2016; Benneworth et al., 2018). It is possible, therefore, that some turn to university–community engagement to improve their reputations—which could be interpreted as a performance-driven motivation (Atakan and Eker, 2007). For example, several authors have argued that universities use community engagement to attract future students and thereby ensure the collection of tuition fees (Hemsley-Brown and Oplatka, 2006; Pampaloni, 2010; Benneworth, 2013a). In terms of research opportunities, Dutch national funding agencies, such as the Dutch Research Council, increasingly require universities to include engagement with other communities in their research proposals. In other words, university–community engagement may also be directly financially motivated. However, as explained in section 2.1, universities can also be motivated by intrinsic beliefs, that is, by value-driven motivation. In particular, the historical, religious, or ideological background of a university may drive its community engagement (Benneworth et al., 2008; Farrar and Taylor, 2009; Goddard et al., 2016).

In addition, external and internal pressures may also motivate universities to consider community engagement, constituting a reaction-driven motivation. As mentioned in section 2.2, stakeholders such as political parties generally expect universities to be “good neighbors.” Other relevant stakeholders may include students, staff, local governments, societal organizations, and other universities. Students, for example, may demand societally relevant education, which “has put pressure on […] universities to provide more community-based learning opportunities” (Furco, 2010, 380). In the Netherlands, policymakers, political parties, and other stakeholders increasingly ask for evidence of universities’ societal impact (Van der Meulen et al., 2019; Sociaal-Wetenschappelijke Raad, 2022).

In summary, a comparison can reasonably be made between the behavior of universities and that of corporations (Benneworth and Jongbloed, 2010; Williams and Cochrane, 2013). Moreover, universities are under increasing pressure to keep up with societal changes in perceptions and expectations of higher education institutions (Fisher et al., 2004; Atakan and Eker, 2007; Weerts and Sandmann, 2008, 2010). Where corporations turn to CSR activities to make a positive contribution to society, then, university–community engagement might similarly be seen as universities’ answer to calls for social responsibility. University–community engagement may thus be better understood in the context of CSR and the marketization of higher education.

In the remainder of this paper, we examine the role of marketization and CSR in the recent trend of increasing university–community engagement among Dutch universities. Specifically, we apply the three types of motivations for CSR (see Figure 1) to interview data regarding university–community engagement in the Netherlands to gain a deeper understanding of the complex motivations of universities in pursuing such engagement.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 The empirical context: higher education in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, 14 public universities and 4 ideologically based universities receive funding from the national government. These can be divided into general and specialized universities (e.g., universities of technology). There are three funding streams: The first is provided by the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science; the second is offered by national research organizations, such as the Dutch Research Council; and the third originates from external sources, such as the European Union. The legal obligations of universities are set out by the Law for Higher Education. Historically, Dutch universities have focused on teaching and research, as these two activities are associated with substantial income streams (Conway et al., 2009). As a result, the “third mission” “has not translated smoothly into a significant social impact […] on Dutch society” (Conway et al., 2009, 59).

The national government aims to increase societal impact through a range of policy measures. A recent example is the City Deal Knowledge Making initiative, a collaboration between local governments, knowledge institutions, corporations, and societal organizations to find solutions to urban issues. In recent years, organizations such as the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Universities of the Netherlands, and the Rathenau Institute have highlighted the need to increase the societal impact and relevance of science, develop open science, and reform the system of recognition and rewards (e.g., Van der Meulen et al., 2019; Sociaal-Wetenschappelijke Raad, 2022).

3.2 Selection of universities and data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews conducted with stakeholders from four Dutch universities: TU Delft, UU, VU, and EUR. These universities were selected for their relatively high reported levels of involvement with university–community engagement. Within the last few years, each has begun to incorporate explicit statements regarding university–community engagement into its official communication, including mission statements and strategic plans. The four universities have also implemented several programs in this area. UU has two programs that concern university–community engagement: Public Engagement, which focuses mainly on research, and Community Engaged Learning. The VU runs a program titled “A Broader Mind” and offers community-service-based courses. The TU Delft operates the program “WIJStad” to connect local societal issues with research and education. University–community engagement and societal impact are also core elements of the strategic plan “Being an Erasmian” (2020–2024) of the EUR.

Of the four universities, UU and the VU are larger institutions. UU has roughly 36,900 students and offers 46 Bachelor’s and 77 Master’s courses. The VU has roughly 31,700 students and offers 45 Bachelor’s and 85 Master’s courses. The EUR could be considered medium-sized, with around 31,200 students and 22 Bachelor’s and 50 Master’s courses. The TU Delft is a relatively small institution: It has around 26,600 students and offers 16 Bachelor’s and 34 Master’s courses.

All four universities are located in the Randstad area and operate at a national and international level. Although the cities of Delft and Utrecht (with approximately 101,000 and 334,000 inhabitants, respectively) are smaller than Rotterdam and Amsterdam (with approximately 623,000 and 821,000 inhabitants, respectively), all four universities are located in densely populated areas characterized by large student populations. These similar contexts enable comparison among the universities, as they rule out such possible explanatory factors as national policies, while the differences in the type of university offer the potential for diversity in the approaches taken to university–community engagement.

3.3 Data collection

The research population consisted of staff members across the aforementioned four universities who were involved in university–community engagement. Focusing on an administrative perspective, we sought to interview, for example, the responsible staff members of the universities’ corporate offices and the responsible members of the executive boards. Because corporate offices at Dutch universities do not employ large numbers of staff, the pool of potential respondents was small. Purposive and snowball sampling were used to identify possible participants. Respondents were recruited via email, through which they were provided with a description of the study and a consent form. Interviews were conducted face-to-face at the respondents’ workplaces and lasted between 45 and 75 min. Before each interview began, the informed consent form was again presented to the respondent, checked, and signed. In total, 18 interviews were conducted between June 2019 and December 2019. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim to enable a thorough content analysis using ATLAS.ti.

The interview questions focused on respondents’ understanding of their respective universities’ motivations for involvement with university–community engagement, the content and organization of that engagement, the influence of various societal developments, and respondents’ attitudes toward university–community engagement. To capture the many possible meanings of the term “university–community engagement,” respondents were not offered a working definition but were instead asked about their own definitions of the concept.

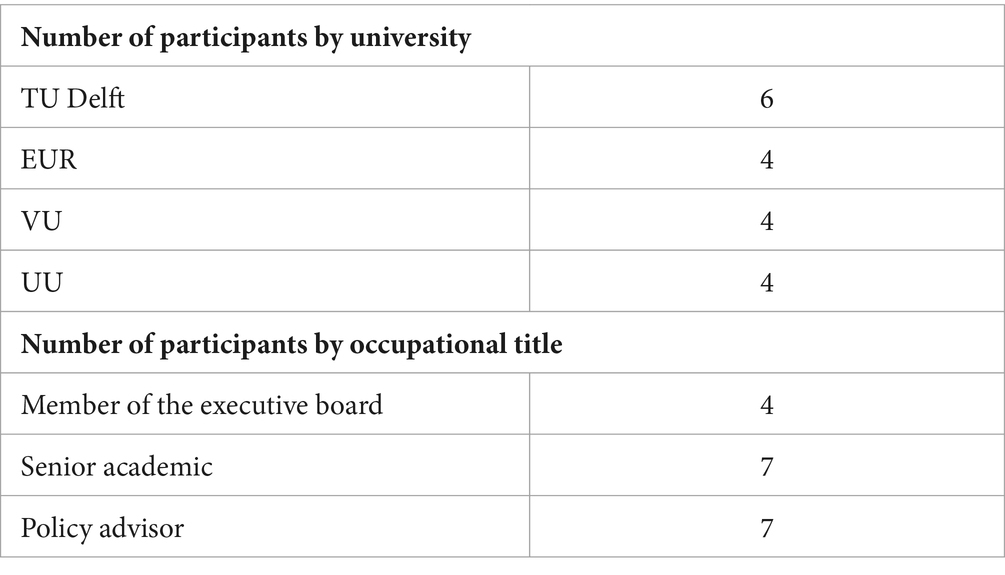

The universities’ names and host cities were not anonymized in the resulting transcripts, as we believe that these provide relevant context. To ensure anonymity for the respondents, however, each was given a general occupational title, such as “senior academic” or “policy advisor.” Since the responsible members of the executive boards could be easily identified when linked to their respective universities, they were each labeled as “member of the executive board,” with no mention of their university or city. Table 1 provides an overview of the participants by university and occupational title.

3.4 Coding and content analysis

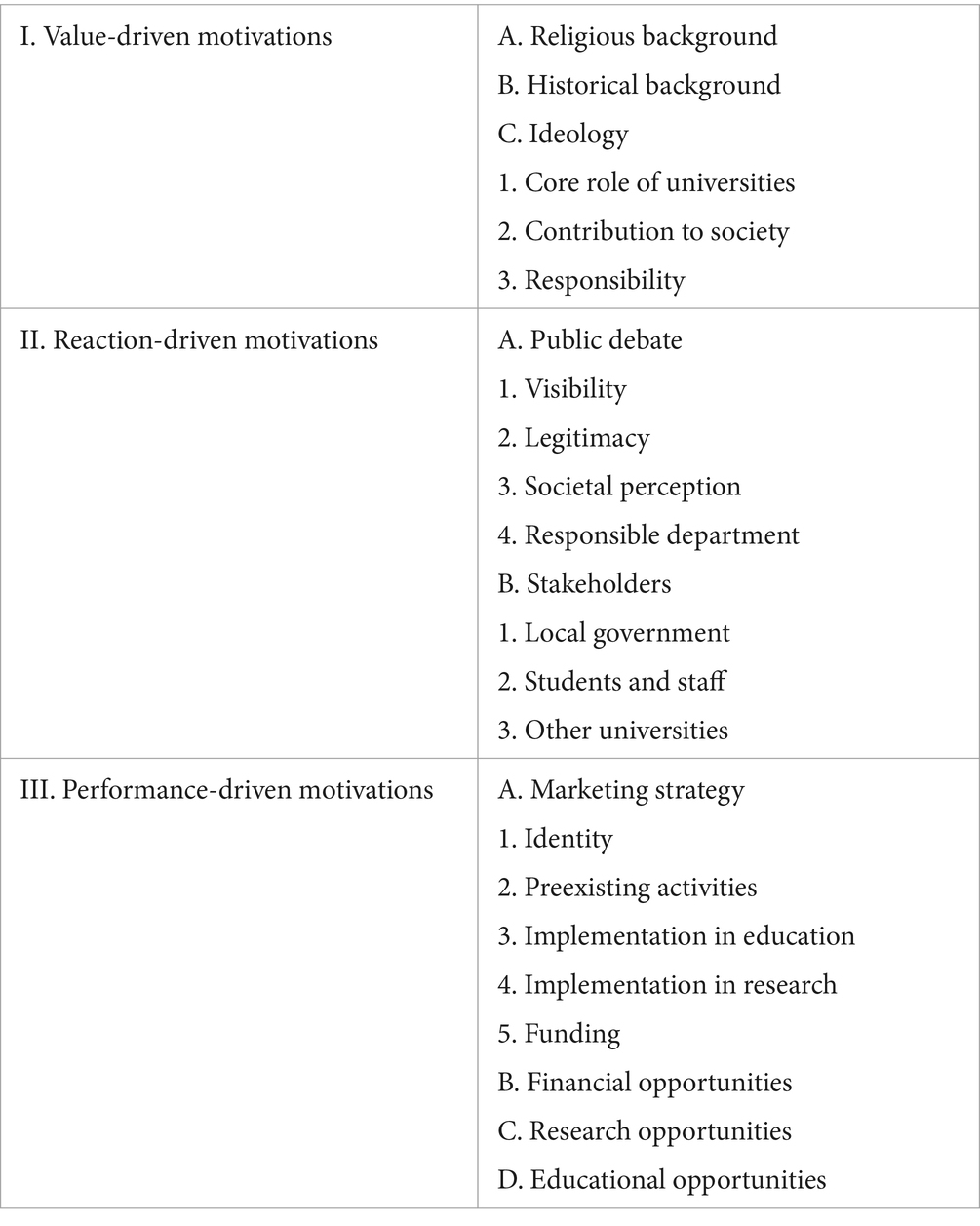

The main objective of the content analysis was to reveal how (configurations of) particular motives of the studied universities connected to the tripartite distinction between reaction-driven, value-driven, and performance-driven motivations; see section 2. In light of the combination of extensive (theoretical) literature and minimal empirical evidence on the topic of motivations for university–community engagement, we needed an analytical approach that combines theoretical classification with harvesting “unexpected” empirical classifications. For this reason, we selected thematic analysis, which enables the simultaneous application of deductive and inductive approaches to the data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). We developed an initial deductive coding frame based on themes and topics drawn from the literature that underlie the various types of motivations (e.g., ideology, historical background, public debate, marketing strategy). Subsequently, we used an inductive approach to allow unanticipated themes to be identified from the data (e.g., visibility, responsible department). These inductively derived codes were categorized as sub-themes, as they represent more detailed aspects of the deductively established main themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006), to develop an overarching explanatory framework (see Table 2). The categorization of the (sub-)themes was based on the three main dimensions of Figure 1: value-driven, reaction-driven, and performance-driven motivations. The overall explanatory framework thus enabled a comprehensive thematic analysis of the three types of motivations. This was first conducted by university and subsequently followed by a cross-case synthesis and comparison across all four universities.

4 Results

The results are set out by theme, with themes divided into value-driven, reaction-driven, and performance-driven motivations.

4.1 Value-driven motivations

4.1.1 Historical/religious background

According to several of the respondents, the historical background of the VU and EUR is a major factor in these universities’ community engagement. The VU was founded in 1880 as a private university and initially focused primarily on Christian theology. Respondents explained that the VU’s involvement with university–community engagement is due to this historical and religious background. The original Christian values of the university led to a focus on inclusivity and charity toward people who needed help, were excluded, or belonged to groups for whom it was not common to attend university. Respondents believed that the identity of the VU still attracted staff members who considered it the responsibility of a university to be socially engaged.

Similarly, respondents from the EUR explained that the university had been involved in the local community since its foundation. As the university was partially founded using private capital and the desire for a university in Rotterdam came from its citizens, a bond was formed with the local government, business sector, and public sector. University–community engagement is, moreover, a core element of the strategic plan “Being an Erasmian” (2020–2024), which, respondents from the EUR explained, is linked to the historical background of the university. Specifically, the university is named after the philosopher Erasmus, who was born in Rotterdam in the 15th century, and the five core values on which the strategic plan is built, including societal engagement and connectedness, are similar to his guiding ideas, which is why the university calls them “Erasmian Values”.

4.1.2 Ideology

Several respondents felt that it was part of the mission of universities to contribute to society beyond research and teaching. Some also felt a responsibility to offer their students a broader form of development—a kind of Bildung. They expressed the belief that students would become better people in general by developing an awareness of how the world works outside of their own “bubble.” Several respondents explained that universities are somewhat elitist and that university–community engagement can bring different groups together, as the activities involved bring students into contact with different organizations and neighborhoods they would not otherwise visit.

University–community engagement was also seen as a way to contribute to decreasing educational inequalities. For example, the TU Delft and UU participate in the project “Meet the Professor.” By visiting primary schools, respondents hoped to encourage children from less privileged socioeconomic backgrounds to develop an interest in attending university. This can be linked to the topic of public debate: Activities such as these can be used to show how universities operate, providing a form of accountability (see section 4.2.1). The following quote shows how societal expectations have assumed greater importance in university–community engagement illustrates the possible blending of different types of motivations:

That other motif, that as a university you need to consider very carefully whether what you are doing is seen as legitimate, is supported by society. […] It’s a mix of that idealistic goal of improving society that has now been coupled to political legitimacy. (TU Delft, senior academic)

Value-driven motivations may thus be linked to reactions to larger contextual developments, such as societal expectations. This brings us to reaction-driven motives.

4.2 Reaction-driven motivations

4.2.1 Public debate

According to several respondents, many people have a mistaken idea of science and universities. This undermines the legitimacy of and societal trust in universities and creates a perceived dichotomy between universities and wider society (Bruning et al., 2006; Dempsey, 2010; Farnell, 2020). Examples of the perceptions mentioned by respondents included that universities receive a lot of money from local governments; that students only party and drink; and that research is not independent or free of (leftist) values. One respondent clearly described how a perceived dichotomy between universities and wider society may negatively affect universities’ legitimacy:

If, as a university, you continue practicing and carrying out research and teaching separate from society, legitimacy becomes an issue, in part because the university is not automatically trusted. At the end of the day, we are an establishment, in a time of somewhat anti-establishment feelings. And also because we are in a sort of post-truth period. What does all that academic knowledge contribute anyway? (UU, senior academic)

“Visibility” was often mentioned as a factor in why and how universities adopt university–community engagement strategies. Engagement activities are used to illustrate why institutions are worthy of receiving funding from taxation. They also allow scientific knowledge and skills to be applied at a local level, which makes them more visible to the public. Finally, university–community engagement is a way for academics to tell a story about what a university does and how science works: Through activities such as participatory research, citizens learn about the different aspects of research.

For respondents from the TU Delft, visibility was also linked to local perceptions of the university. According to these respondents, many citizens see only the negative side of having a large university in the city. Issues include nuisance caused by students and large numbers of bicycles throughout the city. University–community engagement is used to show the positive side of the university’s presence: This is done through activities such as student volunteering, as well as the exhibiting of technological innovations in the city center. The latter example, in particular, seems to be a part of a marketing strategy—interestingly, at the TU Delft, university–community engagement falls under the remit of the department of strategy and communication.

Several respondents saw the public debate not only as a negative driver to which universities were forced to react; rather, they believed that universities should take the opportunity to reflect on their identity and position in society, as that society is continuously changing. According to these respondents, today’s society rightly asks for greater societal impact from universities. One respondent emphasized that this call from society requires universities to answer a fundamental question about their raison d’être:

For a long time, the prevailing attitude was, let the professionals get on with it, we bring forth sensible things, do not interfere with us. I think that it is actually a very good thing that we are now really being forced to answer the question, why are we here? And for whom? (member of the executive board)

4.2.2 Stakeholders

During the interviews, certain major stakeholders in university–community engagement were mentioned. These are detailed below.

4.2.2.1 Local government

For the TU Delft, the local government plays a substantial role in university–community engagement. In 2017, an agreement was made between the executive board of the university and the local government, including a section on university–community engagement. The respondents pointed out that the administration of the TU Delft was not interested in the university’s local environment before the arrival of the current mayor. Many described the situation as one where, had the university been picked up and placed in a different city, it would have made no difference.

The EUR also has a covenant with the local government, which has been in place since 2010. At the administrative level, both parties wished to institutionalize their relationship, as the number of practical collaborations was increasing, but clear organization remained limited. The covenant improved communication between the EUR and the local government and led to greater financial commitment from both parties. As in the case of Delft, the mayor of Rotterdam was identified as playing an important role in the relationship between the university and the local government:

Then we say “What keeps [Mayor] Aboutaleb awake at night,” or something along those lines, and that’s really the driving force behind the meetings. (EUR, senior academic)

In other words, bot actors really tried to instill the collaboration with clear and shared ideas on its wider meaning and (possible) outcomes.

4.2.2.2 Students and staff

Both the EUR and UU had conducted research among their staff and students to identify the focus for their new strategic frameworks. Several respondents reported that this research had showed that societal responsibility and impact were important themes to the current generation of students and younger staff members. These findings formed the basis for university–community engagement at both universities. For example, UU had begun to organize workshops about public engagement, where students wo take societal responsibility very seriously, learned about different ways to disseminate their research.

What I also think it includes, […] that you see many students who find social issues and responsibility very important. So it’s not, it’s not just us exploring how we can connect this to the teaching, but you see that they are calling upon the board, they also want to see that connection. (EUR, senior academic)

4.2.2.3 Other universities

Several respondents mentioned the lack of any major collaboration between the executive boards of Dutch universities in the field of university–community engagement. At other administrative levels, they reported some communication, mainly aimed at sharing inspiration. The respondents ascribed this minimal collaboration to the local nature of university–community engagement: Every city is different, so activities are customized to local surroundings (e.g., available partners, problems, opportunities).

Several respondents mentioned the City Deal Knowledge Making initiative of the national government. This is a collaboration between local governments, knowledge institutions, corporations, and societal organizations that aims to find solutions to urban issues. Although it cannot be fully equated with university–community engagement, it involves a network of individuals who are often involved with both the initiative and university–community engagement programs.

Among Dutch academics, there is a growing demand for change in the current system of recognition and rewards. Many feel that the current assessment system lacks balance in its valuation of research, education, impact, and leadership (Van der Meulen et al., 2019; Smit and Hessels, 2021). An example of this trend on a wider basis is the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment, which UU has signed. Among others, this declaration aims to improve the evaluation of scientific output by eliminating the use of journal-based metrics and exploring new indicators of impact. Several respondents placed university–community engagement within this context, believing that a new assessment system for impact would facilitate the further growth of university-community engagement.

You could ask the question, and I often do ask it, what is more interesting or important, is it being published in Nature or Science, etc., or is it the results of a study that will end up in the guidelines used by every GP in the Netherlands? For me, the answer is crystal clear. Only the second example, the guideline, will never be published in a journal, so you will not get a single citation from it. So we need to really broaden our thinking about what constitutes the result of research and how we can give it equal value. (UU, member of the executive board)

Should the current competitive environment change, on this basis or another, not all competition will disappear. Rather, it seems that the rules of the competition are changing: The new goal is to become a “civic” university, and the means of getting there involve university–community engagement, an instrumental perspective that leads to our final section.

4.3 Performance-driven motivations

4.3.1 Marketing strategy

Several respondents noted that university–community engagement can be seen as a “selling point” in the competition among universities (Bruning et al., 2006). It is used to build up an identity that may attract future students and staff. At all four universities, many activities already existed in this area before the term “university–community engagement” gained prominence. They were first called “service,” “knowledge transfer,” or “valorization” and now “university–community engagement.” The relevant activities were mainly relabeled, making the greatest change that taking place at the administrative level. The term “university–community engagement” is now explicitly incorporated into university policies, for example at TU Delft.

All of a sudden we are calling it community engagement, but I think there’s a difference between administrative engagement and what we have actually always been doing. And now it’s just becoming more formalized. In the beginning, it was an informal circuit and not labeled as such. (TU Delft, senior academic)

Respondents reported that university–community engagement was mentioned through various channels of communication, but actual implementation in curricula and available funding differed from one university to another. The VU and UU had incorporated university–community engagement into their courses and research. Respondents from the EUR expressed the ambition to implement further engagement over the coming years. At the higher administrative level, respondents from the TU Delft reported, the university did not want to implement university–community engagement as part of its curricula, preferring to focus on volunteering: Proponents of this approach argued that further engagement would take away the intrinsic motivation of students, and they did not wish to impose it upon their staff. At the lower administrative level, some respondents reported that they would like to see further implementation. However, other respondents observed that the discussion about costs for community engagement in practice often outweighs its marketing benefits of engagement.

The trouble is that you often see that this kind of pilot that is going really well is used in a certain way, particularly by the board, to make a good impression; it gets bandied about whatever the occasion. But if we say we need an extra €50,000 for a new assistant, it’s not possible. Then I think, how does that square up? (VU, policy advisor)

4.3.2 Financial opportunities

Funding agencies such as the Dutch national government and the European Union increasingly demand evidence of the societal impact of research. For the TU Delft, financial support from the local government was one of the key incentives to establish the agreement with the former, in which university–community engagement was mainly the idea of the mayor. In this context, university–community engagement may be seen as a means of exchange between universities and other partners (Atakan and Eker, 2007). In the words of a TU Delft policy advisor:

There are also financial reasons, of course. If I look at it from a TU Delft perspective, the campus is facing a number of huge challenges, accessibility and growing student numbers, that sort of thing. So we do not just need partners for that, but also money. (TU Delft, policy advisor)

4.3.3 Research and educational opportunities

University–community engagement creates possibilities in research and education. UU has a program for public engagement that mainly focuses on research. Through activities such as citizen science, it aims to generate interactions between society and the university. Citizen science can be defined as “the intentional involvement of members of the public in scientific research” (Phillips et al., 2019, 666). The motivation for this program, as respondents noted, is twofold: On the one hand, it is performance-driven, as it offers pragmatic advantages (for example, citizen science can boost the amount of data collected); on the other hand, the public debate on universities again plays a role—a reaction-driven motivation. Citizen science can be used:

not just to inform the public about the results of specific research but also about science in general, in these times where “science is also just an opinion.” And why so many millions, if not billions, are poured into it. It’s also about showing accountability. (UU, policy advisor)

University–community engagement also offers benefits for students. As section 4.1.2 notes, this can be linked to the value-driven consideration of universities’ responsibility to teach students about others’ experiences. In a more practical sense, several respondents expressed the view that students would become better professionals through university–community engagement. Specifically, working with professionals and sensitive target groups can teach students how to conduct themselves and perform societally relevant research.

5 Discussion

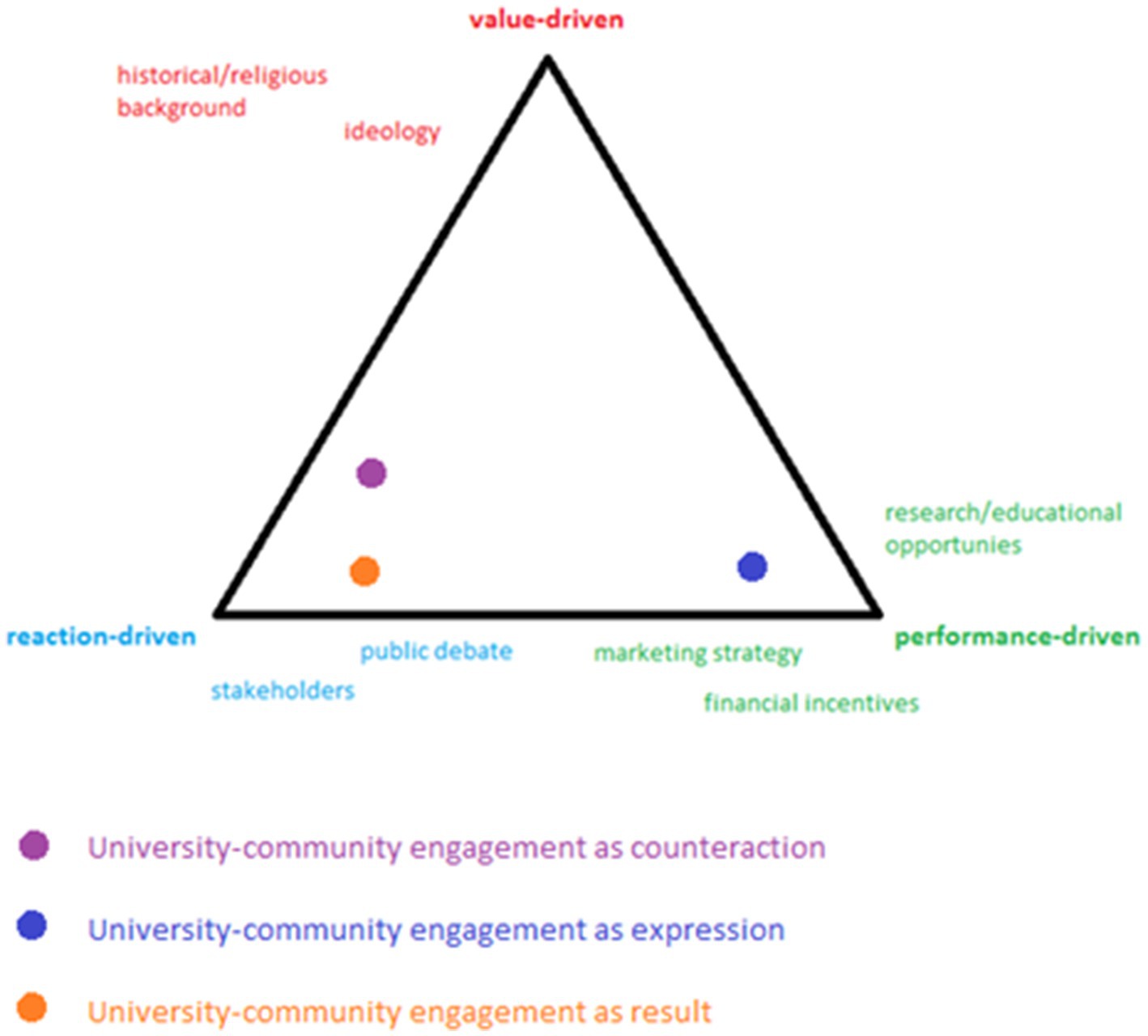

As explained in the theoretical framework, higher education institutions are increasingly coming under the influence of marketization (Benneworth et al., 2008, 2018; Albertyn and Daniels, 2009; Farnell, 2020). University–community engagement may, therefore, be better understood in the context of CSR and the marketization of higher education. We developed and applied a conceptual framework based on three types of motivations for CSR to the motivations for university–community engagement reported by interviewees from four Dutch universities. From the results, we identified three relationships between marketization and university–community engagement: university–community engagement as a counteraction against marketization; university–community engagement as an expression of marketization; and university–community engagement as a result of marketization. These relationships are closely intertwined and exist simultaneously. Figure 2 shows how the motivations for university–community engagement presented above and the proposed relations with marketization are linked. These links are discussed in further detail in the following sections.

Figure 2. Links between motivations for university–community engagement and relationships with marketization.

5.1 University–community engagement as a counteraction against marketization

First, some aspects of university–community engagement at the four universities seem to counterbalance the influence of marketization. This finding is in line with those of earlier research (e.g., Barker, 2004; Ostrander, 2004; Dempsey, 2010). Universities are involved in an international competition that focuses heavily on rankings and publications, resulting in a high-pressure, performance-driven working environment (Gelmon et al., 2013; Goddard et al., 2016). University–community engagement can be seen, in some respects, as a reaction to this: It focuses on local relationships rather than international ones, involves forms of academic output other than traditional publishing, and acknowledges the value of societal impact more than traditional rankings do.

In particular, the movement for a new approach to recognizing and rewarding academics can be seen as a protest against marketization. In the current academic system, scholars often report an absence of rewards for engagement activities, a lack of procedures for documentation and evaluation, and concerns regarding the time it takes to engage with local communities (see, e.g., Koekkoek et al., 2021). These findings raise the question of whether the additional tasks involved in university–community engagement are worthwhile, particularly if this engagement is not fully implemented and facilitated by universities. As it stands, university–community engagement often depends on the personal efforts and motivation of academic staff. Changes in the system of recognition and rewards may accommodate the advancement of university–community engagement while offering adequate support to academic staff.

This relationship between university–community engagement and marketization reflects a mixture of motivations. As a reaction to the external pressure of marketization, it involves a reaction-driven motivation. In university–community engagement’s apparent offer of a new way to compete with other universities, there is also a performance-driven motivation. Finally, a value-driven motivation appears in the idealistic aspiration, reflected across the four universities, to make a positive contribution to society beyond research and teaching.

5.2 University–community engagement as an expression of marketization

Second, university–community engagement can be seen as an expression of the marketization of higher education institutions. Similar to other studies, our findings show that university–community engagement offers a competitive advantage and is used as a marketing tool to improve the reputation of universities and form an institutional brand—a practice quite similar to corporations’ use of CSR activities (e.g., Hemsley-Brown and Oplatka, 2006; Nejati et al., 2011; Benneworth, 2013a). The involvement of students at UU and the EUR can be seen as a sensible corporate decision in this context, as it may keep current students satisfied with their choice of university and attract future students. Likewise, it is practically significant for universities to ensure that stakeholders such as local governments have a “favorable disposition” toward them (Atakan and Eker, 2007), since local governments are a source of financial opportunities.

As with CSR, questions arise about the implementation of university–community engagement. Across the four universities, respondents indicated that the available funding and support for university–community engagement were limited. Furthermore, activities used for university–community engagement had often been conducted for some time before being relabeled and explicitly communicated by the universities. The question thus arises of whether university–community engagement is being used as “window dressing” (Atakan and Eker, 2007).

This relationship encompasses a performance-driven aspect, since pragmatic drivers such as marketing considerations play a role. A value-driven motivation can be recognized in that universities base their institutional brand and thus their university–community engagement on their backgrounds: Although their goal is pragmatic, they wish to be able to stand by their activities. Finally, a reaction-driven motivation is present because of the link with the public debate on the role of universities.

5.3 University–community engagement as a result of marketization

Third, the public debate on the role of universities is a major driving factor in university–community engagement. Our findings show that the four universities studied all feel pressure to demonstrate their societal relevance and contribution to society and that as part of their strategy to do so, they turn to university–community engagement. The question nonetheless remains as to whether this engagement improves the societal perception of universities. So far, little research exists on the relationship between university–community engagement and societal perceptions (Benneworth et al., 2018; Van der Meulen et al., 2019; Koekkoek et al., 2021).

If universities only engage locally for their own benefit (to show their societal relevance) or because society requests it, their behavior will remain businesslike, self-serving, and disconnected from their local environment (Van Schalkwyk and De Lange, 2018). In this sense, university–community engagement may trap universities in a paradox: By trying to prove their societal value, they continue to enact market logic. The issue of legitimacy will thus remain unresolved. This raises the further question of whether the responsibilities of universities are limited: If we apply the concept of CSR to higher education, universities are seen as an “extension of the business world” (Munck et al., 2012), but it can also be argued that universities are, through their teaching and research, inherently societally engaged institutions (Nejati et al., 2011).

This relationship again reflects a reaction-driven motivation, although this is almost opposite to the reaction discussed in section 5.1, which defies marketization. This relationship illustrates that university–community engagement can also arise from marketization when the latter’s influence is accepted rather than rejected. A value-driven motivation can be recognized in the intrinsic belief of the respondents that universities and their work are important to society. Finally, the relationship includes a performance-driven motivation, as university–community engagement can constitute part of a marketing strategy (see section 5.2).

6 Conclusion

6.1 Main findings and contribution

In this article, we have explored what role marketization plays in university–community engagement in the Netherlands, aiming to gain a deeper understanding of the factors driving Dutch universities’ community engagement and its manifestations. The central research question was as follows: To what extent does the marketization of higher education play a role in university–community engagement among Dutch universities?

We identified three closely intertwined relationships between marketization and university–community engagement: university–community engagement as a counteraction against marketization; university–community engagement as an expression of marketization; and university–community engagement as a result of marketization. These relationships, as we have shown, exist simultaneously. In addition, we found that university–community engagement in Dutch universities shows several similarities to CSR. Like CSR, university–community engagement is based on a complex mix of value-driven, performance-driven, and reaction-driven motivations. It involves similar dynamics with stakeholders and societal perceptions, similar goals and benefits, similar issues regarding the level of implementation, and similar concerns about the sincerity of the activities involved.

Our research contributes to the literature on this topic by unraveling the complexity of motivations for university–community engagement, as well as the intricate relationship between university–community engagement and the marketization of higher education. In offering an empirical perspective on university–community engagement, the study contributes to a field lacking in empirical evidence. More specifically, our findings illustrate the effects of the public debate on the role of universities. Based on our results, in Figure 2, we offer a model of how the motivations for university–community engagement and the relationships between this practice and marketization are linked. Finally, this paper provides insight into how university–community engagement is understood and operationalized among Dutch universities, adding a new perspective to the research literature in this area, which is dominated by Anglophone cases.

6.2 Limitations and further research

This research has some limitations. As our findings are based on a limited number of respondents and universities in the Dutch context, we do not claim our study to be fully representative for other contexts. Nonetheless, we believe that the inclusion of a diverse selection of universities, approaches, and administrative perspectives, including members of the executive boards of the universities studied, offers a rich exploration of university–community engagement in the Netherlands, and that this article can provide a starting point for future research. Another obvious limitation is the cross-sectional nature of this exploratory study. Because we interviewed respondents once, our view on the evolution of the topic covers a limited period of time.

Given the shortcomings of existing literature, further research on the motivations for university–community engagement should be expanded to other universities in the Netherlands and other countries. Since stakeholders are a major driver of university–community engagement, future research could consider the views of local governments, nongovernmental organizations, professional organizations, and other potential collaborators with universities. Future research may also explore in depth what citizens expect from universities and how university–community engagement fits into these expectations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Human Research Ethics Committee TU Delft. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albertyn, R., and Daniels, P. (2009). “Research within the context of community engagement” in Higher education in South Africa: a scholarly look behind the scenes (Stellenbosch: SUN Press), 409–428.

Antonaras, A., Iacovidou, M., and Dekoulou, P. (2018). Developing a university CSR framework using stakeholder approach. World Rev. Entrepren. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 14, 43–61. doi: 10.1504/WREMSD.2018.089074

Atakan, M. S., and Eker, T. (2007). Corporate identity of a socially responsible university–a case from the Turkish higher education sector. J. Bus. Ethics 76, 55–68. doi: 10.1007/s10551-006-9274-3

Barker, D. (2004). The scholarship of engagement: a taxonomy of five emerging practices. J. High. Educ. Outr. Engag. 9, 123–137. Available at: https://openjournals.libs.uga.edu/jheoe/article/view/890

Benneworth, P. (2013a). “University engagement with socially excluded communities” in University engagement with socially excluded communities. ed. P. Benneworth (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 3–31.

Benneworth, P. (2013b). “The evaluation of universities and their contributions to social exclusion” in University engagement with socially excluded communities. ed. P. Benneworth (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 309–326.

Benneworth, P., Ćulum, B., Farnell, T., Kaiser, F., Seeber, M., Šćukanec, N., et al. (2018). Mapping and critical synthesis of current state-of-the-art on community engagement in higher education. Zagreb: Institute for the Development of Education.

Benneworth, P., and Humphrey, L. (2013). “Universities’ perspectives on community engagement” in University engagement with socially excluded communities. ed. P. Benneworth (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 165–187.

Benneworth, P., Humphrey, L., Charles, D. R., and Hodgson, C. (2008). “Excellence in community engagement by universities” in Proceeding of 21st Conference on Higher Education Research (CHER.) Excellence and Diversity in Higher Education. Meanings, Goals, and Instruments, 1–43.

Benneworth, P., and Jongbloed, B. W. (2010). Who matters to universities? A stakeholder perspective on humanities, arts and social sciences valorisation. High. Educ. 59, 567–588. doi: 10.1007/s10734-009-9265-2

Brammer, S., Jackson, G., and Matten, D. (2012). Corporate social responsibility and institutional theory: new perspectives on private governance. Soc. Econ. Rev. 10, 3–28. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwr030

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brønn, P. S., and Vidaver-Cohen, D. (2009). Corporate motives for social initiative: legitimacy, sustainability, or the bottom line? J. Bus. Ethics 87, 91–109. doi: 10.1007/s10551-008-9795-z

Bruning, S. D., McGrew, S., and Cooper, M. (2006). Town–gown relationships: exploring university–community engagement from the perspective of community members. Public Relat. Rev. 32, 125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2006.02.005

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 34, 39–48. doi: 10.1016/0007-6813(91)90005-G

Conway, C., Humphrey, L., Benneworth, P., Charles, D., and Younger, P. (2009). Characterising modes of university engagement with wider society: A literature review and survey of best practice. Newcastle upon Tyne: University of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne.

Dempsey, S. E. (2010). Critiquing community engagement. Manag. Commun. Q. 24, 359–390. doi: 10.1177/0893318909352247

Farnell, T. (2020). Community engagement in higher education: Trends, practices and policies. NESET report,. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Farrar, M., and Taylor, R. (2009). “University-community engagement: analysing an emerging field” in A practical guide to university and college management: Beyond bureaucracy. eds. S. Denton and S. Brown (London: Routledge UK), 247–265.

Fassin, Y., and Buelens, M. (2011). The hypocrisy-sincerity continuum in corporate communication and decision making: a model of corporate social responsibility and business ethics practices. Manag. Decis. 49, 586–600. doi: 10.1108/00251741111126503

Fisher, R., Fabricant, M., and Simmons, L. (2004). Understanding contemporary university-community connections: context, practice, and challenges. J. Community Pract. 12, 13–34. doi: 10.1300/J125v12n03_02

Furco, A. (2010). The engaged campus: toward a comprehensive approach to public engagement. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 58, 375–390. doi: 10.1080/00071005.2010.527656

Gelmon, S. B., Jordan, C., and Seifer, S. D. (2013). Community-engaged scholarship in the academy: an action agenda. Change 45, 58–66. doi: 10.1080/00091383.2013.806202

Giles, D. E. (2008). Understanding an emerging field of scholarship: toward a research agenda for engaged, public scholarship. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engag. 12, 97–106. Available at: https://openjournals.libs.uga.edu/jheoe/article/view/511

Goddard, J., Hazelkorn, E., Kempton, L., and Vallance, P. (Eds.) (2016). The civic university: The policy and leadership challenges. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Grau, F. X., Hall, B., and Tandon, R. (2017). Higher education in the world 6. Towards a socially responsible university: Balancing the global with the local. Girona: Global University Network for Innovation.

Gumport, P. J. (2000). Academic restructuring: organizational change and institutional imperatives. High. Educ. 39, 67–91. doi: 10.1023/A:1003859026301

Hart, A., and Northmore, S. (2011). Auditing and evaluating university–community engagement: lessons from a UK case study. High. Educ. Q. 65, 34–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2273.2010.00466.x

Hayter, C. S., and Cahoy, D. R. (2018). Toward a strategic view of higher education social responsibilities: a dynamic capabilities approach. Strateg. Organ. 16, 12–34. doi: 10.1177/1476127016680564

Hemsley-Brown, J., and Oplatka, I. (2006). Universities in a competitive global marketplace: a systematic review of the literature on higher education marketing. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 19, 316–338. doi: 10.1108/09513550610669176

Humphrey, L. (2013). “University–community engagement” in University engagement with socially excluded communities. ed. P. Benneworth (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 103–124.

Koekkoek, A., Ham, M.Van, and Kleinhans, R. (2021). Unravelling university-community engagement. A literature review. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engag., 25, 3–24. Available at: https://openjournals.libs.uga.edu/jheoe/article/view/1586

Maignan, I., and Ralston, D. A. (2002). Corporate social responsibility in Europe and the US: insights from businesses’ self-presentations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 33, 497–514. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8491028

Mtawa, N. N., Fongwa, S. N., and Wangenge-Ouma, G. (2016). The scholarship of university-community engagement: interrogating Boyer's model. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 49, 126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.01.007

Munck, R., McQuillan, H., and Ozarowska, J. (2012). “Civic engagement in a cold climate: a glocal perspective” in Higher education and civic engagement. eds. L. McIlrath, A. Lyons, and R. Munck (New York: Palgrave Macmillan), 15–29.

Nejati, M., Shafaei, A., Salamzadeh, Y., and Daraei, M. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and universities: a study of top 10 world universities’ websites. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 5, 440–447.

Olssen, M., and Peters, M. A. (2005). Neoliberalism, higher education and the knowledge economy: from the free market to knowledge capitalism. J. Educ. Policy 20, 313–345. doi: 10.1080/02680930500108718

Ostrander, S. A. (2004). Democracy, civic participation, and the university: a comparative study of civic engagement on five campuses. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 33, 74–93. doi: 10.1177/0899764003260588

Pampaloni, A. M. (2010). The influence of organizational image on college selection: what students seek in institutions of higher education. J. Mark. High. Educ. 20, 19–48. doi: 10.1080/08841241003788037

Phillips, T. B., Ballard, H. L., Lewenstein, B. V., and Bonney, R. (2019). Engagement in science through citizen science: moving beyond data collection. Sci. Educ. 103, 665–690. doi: 10.1002/sce.21501

Sociaal-Wetenschappelijke Raad (2022). Wetenschap met de ramen wijd open. Tien lessen voor wie impact wil maken. Amsterdam: KNAW.

Sandmann, L. R. (2008). Conceptualization of the scholarship of engagement in higher education: a strategic review, 1996–2006. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engag. 12, 91–104. Available at: https://openjournals.libs.uga.edu/jheoe/article/view/520

Smit, J. P., and Hessels, L. K. (2021). The production of scientific and societal value in research evaluation: a review of societal impact assessment methods. Res. Eval. 30, 323–335. doi: 10.1093/reseval/rvab002

Van der Meulen, B., Diercks, G., and Diederen, P. (2019). Eieren voor het onderzoek: prijs, waarde en impact van onderzoek. Den Haag: Rathenau Instituut.

Van Schalkwyk, F., and de Lange, G. (2018). The engaged university and the specificity of place: the case of Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. Dev. South. Afr. 35, 641–656. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2017.1419858

Vasilescu, R., Barna, C., Epure, M., and Baicu, C. (2010). Developing university social responsibility: a model for the challenges of the new civil society. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2, 4177–4182. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.660

Weerts, D. J., and Sandmann, L. R. (2008). Building a two-way street: challenges and opportunities for community engagement at research universities. Rev. High. Educ. 32, 73–106. doi: 10.1353/rhe.0.0027

Weerts, D. J., and Sandmann, L. R. (2010). Community engagement and boundary-spanning roles at research universities. J. High. Educ. 81, 632–657. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2010.11779075

Keywords: community engagement, higher education, marketization, corporate social responsibility, motivations

Citation: Koekkoek A, Kleinhans R and van Ham M (2024) University–community engagement in the Netherlands: blurring the lines between personal values, societal expectations, and marketing. Front. Educ. 9:1005693. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1005693

Edited by:

Shaun Sydney Nykvist, NTNU, NorwayCopyright © 2024 Koekkoek, Kleinhans and van Ham. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anouk Koekkoek, YS5rb2Vra29la0B0dWRlbGZ0Lm5s

Anouk Koekkoek

Anouk Koekkoek Reinout Kleinhans

Reinout Kleinhans Maarten van Ham

Maarten van Ham