- 1Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

- 2Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

- 3Department of Psychiatric Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

- 4Department of Nursing, University of Social Welfare Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 5Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

Introduction: Social accountability is a new paradigm in dental education and a sort of cultural change. This study is an attempt to elaborate on the process of social accountability in the Iranian dentistry education system.

Materials and methods: This study was carried out as a qualitative work based on a grounded theory approach. The participants were selected through purposive sampling and took part in deep semi-structured interviews, and data saturation was achieved with 14 interviews. The main interviews were private, and face-to-face interviews were held on different occasions (morning and afternoon) in a quiet and decent environment. The interviews were held by the author and voice-recorded with the permission of the interviewees. Data analyses were performed through the Strauss–Corbin method along with the interviews.

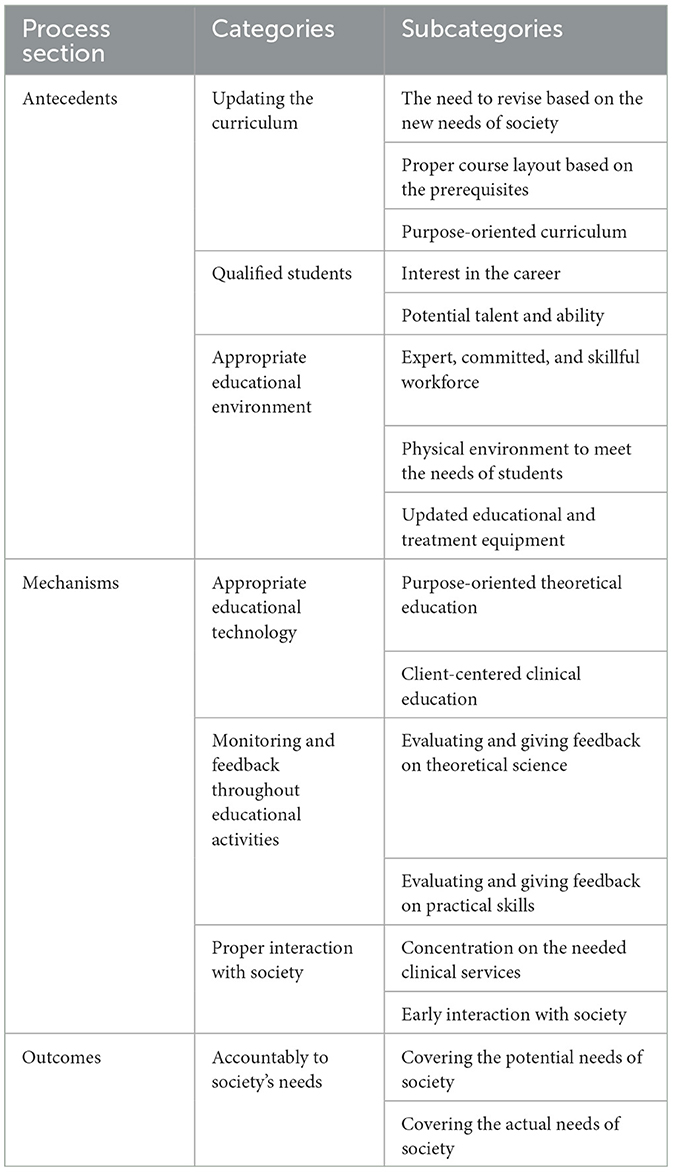

Results: The results indicated that the process of social accountability featured three stages: antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes consisting of 619 codes, 16 subcategories, and 7 categories. Updating the curriculum, qualified students, appropriate educational environment, appropriate educational technology, monitoring and feedback throughout educational activities, proper interaction with society, and accountability to society's needs were the main categories in the study. The concept of proper interaction with society was the core variable.

Conclusion: The results indicated that the process of social accountability has major and effective requirements in the antecedent, mechanism, and outcome stages, and it has a good performance in fulfilling the current needs of society for dentistry services. However, to meet potential needs, it needs special attention and programming.

Introduction

Dentistry education is one of the most expensive programs for medicine students. The educational system needs to prioritize social needs as one of its top priorities (Walker et al., 2008). Comprehending the needs of society in a dentistry education system with a society-centered approach leads to deeper learning and experiences for the students (Brondani et al., 2020). Being accountable to society's needs has received a great deal of attention over the past few years in many branches of science and dentistry in particular (Sanaii et al., 2016).

Social accountability in dentistry education can be seen as a society-centered approach that, along with a detailed and comprehensive examination of society in the dentistry field (Philibert and Blouin, 2020), introduces educational and health policies in the health sector based on the needs of society (Petterson and Shea, 1972; Lindgren and Karle, 2011). Toward implementing such policies and programs, a variety of prevention levels are emphasized by the health system. Eventually, the objective of such a system is to prepare graduates who can provide services to their society (Dehghani et al., 2014). To achieve social accountability, we need to concentrate on the health requirements of society in three fields: social responsibility, responsiveness, and accountability (Abdolmaleki et al., 2017a). Social responsiveness means attempting to recognize needs and problems in society, while social accountability also includes introducing efficient programs to deal with the problems and needs in an efficient way (Salehmoghaddam et al., 2017).

There have been studies on dentistry education and social accountability (McAndrew, 2010; Rohra et al., 2014; Batra et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2015). Social responsiveness in dentistry education is an important and purposeful issue in higher education in health (Batra et al., 2015), and the graduates need to develop adequate skills along with the knowledge to meet the needs in society for dentistry services with commitment and practical approaches (Chen et al., 2015). Therefore, it is essential to pay more attention to the needs of society and responsiveness toward such needs in the policies of the dentistry education system (Batra et al., 2015). To understand the implementation of a society-centered education in the educational system and the way of implementing social accountability in dentistry education in particular, there is a need to monitor and validate educational systems and programs in a continuous manner (Chen et al., 2015). Accountability in dentistry education is a process with diverse fields and intrinsic and extrinsic factors (Abdolmaleki et al., 2017b). To examine different social processes, qualitative studies with a grounded theory approach can be fruitful (Speziale and Carpenter, 2011). Grounded theory research is a study with a naturalistic approach that examines social interactions and processes in a real environment (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). Compared to medical education, in which social accountability is seen as a serious matter, the emphasis on social accountability has received limited attention in other educational fields and majors (Armstrong and Rispel, 2015). Therefore, the objective of this study is to elaborate on the social accountability process in the dentistry education system using a qualitative method based on a grounded theory approach.

Materials and methods

Design

The study was carried out as a qualitative study using the grounded theory method (Speziale and Carpenter, 2011).

Setting

The study environment was a dentistry school and affiliated educational clinics. The school admits postgraduate dentistry students in master's programs and started its activity 12 years ago with 10 educational departments including Pediatric Dentistry, Oral Diseases, Oral Radiology, Oral Pathology, Oral and maxillofacial surgery, Restorative Dentistry, Orthodontics, Endodontics, Periodontics, and Dental Prostheses. More than 50 faculty members work in this school, and every year more than 60 students graduate from this school with a master's degree in dentistry.

Participants

The participants in the study were all faculty, students, and dentists with an education or therapeutic experience in dentistry. Using the purposive sampling method, the participants who met the inclusion criteria entered the study. Being interested in participation, knowledge about the topic, key informant, and having the ability to speak and fill in the informed consent form was other inclusion criteria. With 14 interviews, data saturation was achieved, and throughout the data analysis methods, 2 participants were selected for theoretical sampling.

Data collection

The main data-gathering method in this study was a semi-structured deep interview using open-ended questions. The main interviews were private, and face-to-face interviews were conducted at different hours of the day (morning and afternoon) in a place convenient for the participants. The interviews were conducted by the second author and voice-recorded with the permission of the participants. In addition, memos and note-taking were used throughout the interviews to record tone of voice, accent, smiles, and pauses. The interview time duration depended on the participant's energy. The mean time of interviews was 50 to 70 min on average. To facilitate data gathering, guiding questions were used. The validity of the guiding questions was confirmed by the content validity method and using the opinions of seven medical scientists and researchers familiar with qualitative research.

Guiding questions:

1. How can dentistry education meet the needs of society?

2. What are society's needs that dentistry education experts need to take into account?

3. What are the measures needed to add accountability to dentistry education?

4. What factors affect social accountability in the dentistry education system?

5. What are the steps to make the dentistry education system socially accountable?

Data analysis

Strauss and Corbin's method was followed for data analysis (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). The main stages of this method are open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. To this end, the recorded voices from the interviews were listened to several times and then transcribed using Word Office 2016. The transcribed interviews were read twice and open-coded. The codes were selected from words and sentences in the interview scripts. All the interviews were analyzed immediately after the interviews along with the next interviews. Afterward, the authors started to study and compare the extracted codes continuously to determine similarities and differences. The codes with similar features were categorized into one category. Categorization was conducted through axial coding. The continuous process of comparing codes and rearranging them among categories along with adding new codes based on similarities and differences was continuous throughout the data analysis stages. Continuous comparison of codes and themes along with categorizing and organizing new codes resulted in the formation of codes and themes. In addition, memos were used in data analyses. To integrate, purify data analysis, discover main themes, achieve the core variable, and discover the relationship between themes, storyline writing was used.

Rigor

To make sure of data rigor, Guba and Lincoln's four measures were used (Speziale and Carpenter, 2011). The authors spent long hours in the research environment to win the trust of participants and gain a reliable perception of the research environment. Data analysis results were confirmed by the participants' focus group meetings to make sure that the authors had a correct perception of the participants' ideas and thoughts. In addition, a wide range of participants in terms of age, gender, work history, and type of service were selected to increase the credibility of the findings. As to conformability, researchers' ideas and perceptions were bracketed, and the principles of no bias were observed in data gathering, analysis, and dissemination of the findings. In addition, university professors and researchers familiar with qualitative research and the topic were consulted. To control the dependability and stability of the findings, the interviews were transcribed and coded independently by three researchers. The findings were provided to other members of the research team and other experts to make modifications if needed. In addition, some of the interview scripts were reviewed by supervisors. To make sure of transferability, a rich description with details about the environment and participants was provided along with the demographics of the participants. In addition, numerous direct quotations were used in the Results section.

Results

In total, five general dentists (at least 3 years of experience and at most 7 years of experience as general dentists), six faculty board members (three associate professors and three assistant professors with at least 5 years and at most 9 years of experience), and three senior dentistry students were interviewed. In addition, 16 private interviews and 1 focus group interview were held, and throughout the data analysis phase, a general dentist and a senior dentistry student were recruited as theoretical sampling.

After the completion of interviews and simultaneous analyses, 7 categories, 16 subcategories, and 619 codes were obtained. Table 1 lists the categories and subcategories and the steps of social accountability in the dentistry education system based on the results of interview analyses.

Categories and subcategories

As illustrated, the process of social accountability in dentistry education in Iran features three stages: antecedent, mechanism, and outcomes. Each one of these stages also contains categories and subcategories.

Updating the curriculum

The category contains three subcategories as follows:

The need to revise based on the new needs of society

This subcategory is based on the data derived from the clients' statements and emphasizes the need to pay attention to the day-to-day needs of society in different fields and reconstructive needs in particular. The university professors stated, “What people want from dentistry is beauty dentistry, which is only briefly mentioned in the curriculum, while the students need more knowledge about such dentistry services…”.

“There are good content in the curriculum; however, the society had new demands so that along with basic education, advanced content and the needs of society should be covered as well…”.

Proper course layout based on the prerequisites

The majority of participants believed that the specialized courses should be made available with priority and observation of the prerequisites. One of the professors said, “Some courses contain highly specialized and advanced content, which need basic courses as prerequisite. For instance, while students are not familiarized with radiology, they need to pass courses that need diagnosing teeth decay…”.

Purpose-oriented curriculum

The participants' statements indicated a need for constant revision of the curriculum and a purpose-oriented layout of the courses. One of the dentists stated, “there were challenging and useless courses in the curriculum, while the portion of useful and critical courses was very small…”.

A professor added, “The current curriculum is not designed based on the new needs of society and it needs to become purpose-oriented through timely revision based on the new needs in society…”

Qualified students

The category contains two subcategories as follows:

Interest in the career

Based on the interviews, it was found that the number of students who are interested in dentistry is declining, which is due to the good financial expectations in a dentistry career. Students are admitted based on rank in national admittance exams, and the main motivations for students to choose this major are good financial opportunities and income in the future.

The professors believed that “even in the first year, the students are eager to know the income and money they can expect for providing each new service they learn…”. “In the early stages of training, the students are only concerned about beauty treatments and skills that can create more income. They are not interested in skills related to oral health…”.

Potential talent and ability

The participants emphasized that potential talent and ability in students were the key factors in training capable dentists. One of the professors noted, “Many of the students entering the program are very talented and smart; unfortunately, however, instead by concentrating on learning and self-empowerment, many of them seek opportunities to earn more income after graduation…”.

Suitable educational environment

The category contains three subcategories as follows:

Expert, committed, and skillful workforce

The participants believed that given the importance of clinical education in dentistry, it is imperative to have skillful, committed, and capable instructors. Students noted that “There are only a few good instructors in the school, and the rest are newly graduates who are not familiar with teaching skills…”. Another student added, “The majority of newly recruited instructors do not have the skill or intention to teach students…”.

One of the instructors mentioned, “Unfortunately many of the instructors are not interested in their job and they only work as a faculty board member to fulfill their obligatory services…”.

Physical environment to meet the needs of students

The participants believed that the physical space was not enough for that number of students. One of the newly graduated dentists noted, “There are too many students and a few patients and dental units and none of us were able to master the skills expected in the curriculum…”.

One of the professors mentioned, “There are too many students in clinical courses, and we cannot work with all students and teach all the skills to them…”.

Updated educational and treatment equipment

All the participants mentioned the need for adequate modern equipment to meet the new needs and advances in science. A professor noted “We need adequate new equipment and tools to implement the curriculum and extra material that the students need to meet the new needs in society. This a problem almost in all dentistry schools in the country…”. “The equipment is outdated even in the schools located in the capital city let alone the schools located in other smaller cities…”.

Educational technology

The category contains two subcategories as follows:

Purpose-oriented theoretical education

The participants believed that using proper educational technology and concentrating on the needs of society and providing content that empowers students more efficiently were key factors in accountability-oriented education. One of the professors said, “Us teachers need to also focus on the educational needs of society in the educational process in addition to the curriculum…”. Another participant added, “Teachers need to follow specific framework and objective and in this case is to improve the knowledge needed by dentistry students…”.

Client-centered clinical education

All the participants noted that education must take into account the needs of clients and make the student realize that the key point in clinical activities is the client's needs and preferences. One of the professors noted “Interacting with the patients and accepting them along with their cultural concerns are highly important in clinical education. Students need to learn to pay attention to patients' opinions in providing clinical care…”.

One of the dentists added, “Teachers in the clinics only perform the primary measures and ask the clients to visit their own clinic for more specialized services…”.

Evaluating and giving feedback on educational activities

The category contains two subcategories as follows:

Evaluating and giving feedback in theoretical science

Evaluating and giving feedback in theoretical education was one of the key issues emphasized by all participants. One of the professors noted, “Educational processes need to use evaluation methods that suit the education and give feedback to students based on the evaluations…”.

One of the graduates said, “All we did was to memorize the material and since the questions were based on the textbooks, we were able to gain top scores…”.

Evaluating and giving feedback on practical skills

All the participants highlighted that measuring students' performance in clinical courses and giving feedback to them highly affected education outcomes. A professor noted, “There are too many students in clinical courses and it is not actually possible to evaluate skills of all students. In fact, there is no time for evaluation and giving feedback…”.

A graduate added “Unfortunately, there were too many of us in clinical courses and it was not possible for us to practice clinical measures on patients as needed. There was a limited time and the instructor was too busy to evaluate us or give us feedback…”.

Proper interaction with society—Core variable

The category contains two subcategories as follows:

One of the main categories that interacted with other categories and was considered the core variable was proper interaction with society, which comprised two subcategories.

Concentration on the needed clinical services

All participants believed that the dentistry services needed in society must be covered in the program. A professor noted, “the instructors need to be in contact with society to find out what type of dentistry services are needed most and cover such needs in their teaching…”. A student added “the majority of instructors only cover some of the cases and complications in the clinic of school. Some others, however, have their own clinic and invite us over to learn those services that are not provided in state-run clinics…”.

Early interaction with society

The participants emphasized that students should enter clinical fields as soon as possible after entering the program. Through this, they can understand the needs of society for specialized services and interact properly with society. A professor noted “students can spend more time in clinical setting and interacting with people if they enter clinics sooner in the program. Through this, they can have a better understanding of people's needs and prepare themselves to answer such needs…”.

Accountability for the needs of society

The category contains two subcategories as follows:

Covering the potential needs of society

Data analysis indicated that without proper infrastructure and due to non-purposeful programming, the dentistry profession has failed to keep up with the growth of dentistry science around the world. Since it has failed to predict the potential needs of society, it has failed to prepare itself for them. Professors said, “Giving the low salary given to the faculty board members, the majority of professors seek more revenue by opening their own clinic, which consumes all the time that are supposed to spend on studying and researching…”. “Dentistry schools are in charge of developing dentistry science, while because of limited budget, they cannot keep up with the world in terms of equipment. Therefore, there is also a gap between us and the needs of society…”.

Covering the actual needs of society

The participants highlighted that the knowledge transferred to dentistry students and graduates can cover the actual needs of society, and the shortcomings are limited to reconstructive dentistry and some special services that are highly expensive and not covered by medical insurance. A professor noted, “there are shortcomings in the curriculum about reconstructive services needed by the society. Still, it covers all the current needs of society for dentistry services…”. “Taking into account the number graduates in general and specialized fields, we can say that the current needs of society for dentistry education are covered…”.

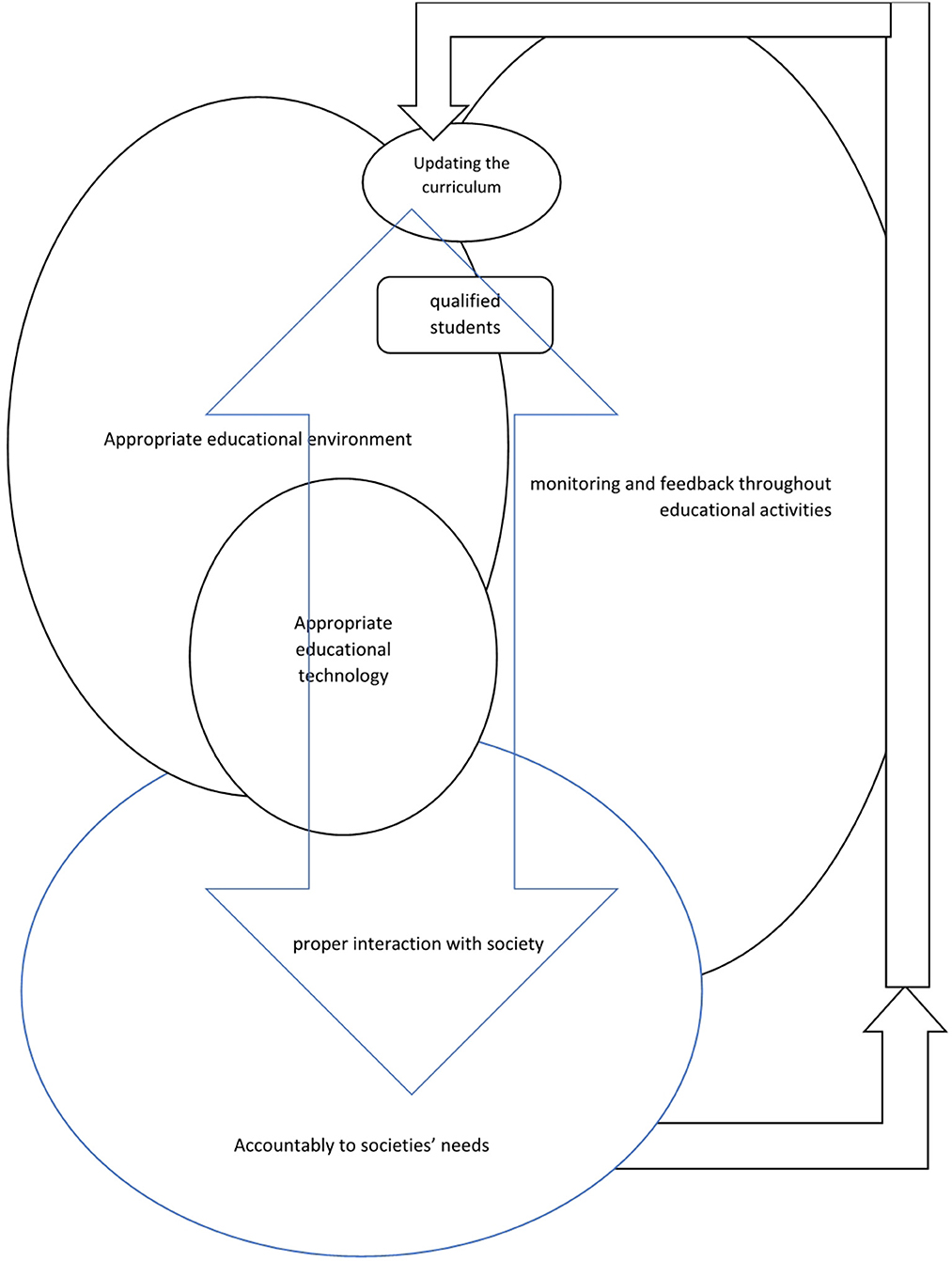

Storyline

The process of social accountability in the Iran dentistry education system is composed of three parts: antecedent, mechanism, and outcomes. It starts with curriculum design, and factors, such as qualified students and proper educational environment, are the main variables in the antecedent stage with a notable effect on the process. With properly designed and arranged factors in the antecedent stage, positive effects on the process that activates the mechanisms can be expected. The process mechanisms include educational technology, evaluation and feedback in education, and proper interaction with society. In the case that the antecedents are designed properly and the mechanisms demonstrate the required efficiency, the process can meet the actual and potential needs of society (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual model of social accountability for the Iranian dentistry sciences education system.

Discussion

The social accountability process in the dentistry education system was elaborated qualitatively and using a grounded theory approach. As the results showed, the process features three steps of antecedent, mechanism, and outcomes in a conceptual model with 7 categories and 16 subcategories.

Factors such as updating the curriculum, competent students, and a proper educational environment were antecedent factors with a profound impact on the process. The curriculum needs to be updated regularly given the latest needs of society for dentistry services and reconstructive dentistry in particular. In addition, the curriculum content should be designed in a purpose-oriented manner and arranged based on priorities. Daher et al. (2012) conducted a study in Brazil and found that a curriculum based on the needs of society can provide dentistry students with valuable experiences; however, failure to update the curriculum based on the needs of society can lead to unwanted outcomes. Kassebaum et al. (2004) also showed that changes and innovations in curriculum relative to the needs of society were essential for dentistry students and had positive effects on their learning. Witton and Paisi (2021) found that creating society-based learning opportunities in the dentistry program provided the students with better learning and interaction opportunities. To elaborate on the findings, given the continuous progress of medical sciences and dentistry in particular, it is important to stay updated and consistent with changes in society. In addition, there is a need to create better coordination between different disciplines based on the new findings and changes in society to meet the changing needs of society. The outcomes of this coordination should be reflected in the educational process. To this end, we need to create a proper educational environment including recruiting committed and efficient faculty board members and admitting talented and interested students. Blouin and Philibert believed that educational evaluation in the educational environment of instructors, equipment, clinical and theoretical education environments, and educational processes were methods to empower disciplines to meet the needs of society (Philibert and Blouin, 2020). Olsson et al. (2021) showed that a society-oriented curriculum in dentistry education can help students answer the needs of society. Therefore, such a curriculum not only ensures deep learning in students but also makes them more accountable to society (Brondani et al., 2020).

Factors such as educational technology, evaluation and feedback in educational activity, and proper interaction with society affected the process under study. The findings indicated that a proper interaction with society as the core variable was connected with all categories with a direct impact on the process. Purpose/clinical-oriented education, using standard evaluation and assessment methods, and proper and timely interaction with society can be the outcomes of the variables in the antecedent stage. The variables in the process, when supported well by the variables in the antecedent stage, can cover the needs of society. Other studies have also emphasized the educational process, educational technology (Philibert and Blouin, 2020), and proper interaction with society (Strauss et al., 2010). Brondani et al. (2020) found that giving efficient feedback and purposeful evaluation to students based on a society-oriented curriculum can empower the students to be socially accountable. To explain the findings, early, proper, and dynamic interaction of students with society in all disciplines and curricula can train more responsive and social-oriented students. Through such an educational environment, good planning to develop a society-oriented curriculum, and using updated educational technologies, we can expect training empowered and society-oriented graduates.

As the results showed, the dentistry education system was socially accountable to some extent given the shortcomings in the curriculum, education system, student admittance system, and faculty board member recruitment, that is, the system has managed to meet the current needs of society and because of the said shortcomings, it has failed to answer the potential needs of society. Chen et al. (2015) found that dentistry education needed to answer the needs of society, but in practice, it had failed to do so because of the ruling mindset of the graduates who believe oral and dental health should be the priority of society. To be properly accountable to the needs of society, dentistry education needs to detect the requirements and variables in the process and introduce a proper program for them. Several studies have also highlighted the requirements of the process such as curriculum (Kassebaum et al., 2004; Yamani and Fakhari, 2014; Emadzadeh et al., 2016), a decent environment (Kassebaum et al., 2004; Emadzadeh et al., 2016; Ventres et al., 2018), and educational technology and evaluation (Philibert and Blouin, 2020; Olsson et al., 2021). Therefore, the social accountability process in medical education has prerequisites known as antecedents that are considered the foundations and basis of this discipline, and the main mechanism in the process that determines the variables affecting the process and results in the main outcomes of the process, i.e., fulfilling actual and potential needs of society as to dentistry. In this regard, we always need to interact with society efficiently and in a timely manner to cover the cultures, expectations, and preferences of the main communities in society.

Study limitations

One advantage of the study was the qualitative approach followed in a real environment, which gave a realistic picture of the process under study. Unfortunately, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the selected participants refused to participate in the interviews for approximately 1 year until the prevalence of the virus was controlled for some periods in Kermanshah City, Iran, and the participants agreed to attend the interviews. Given the situation, selecting the participants and conducting the interviews took more than 1.5 years, which was due to the closure of schools and the reluctance of the participants to attend the interviews.

Conclusion

In summary, the results showed that the process of being accountable to society's needs in dentistry education featured three stages: antecedents, mechanism, and results. The process also included 7 categories and 16 subcategories in which proper interaction with society was the core variable. The results indicated that the process has been successful in covering the actual needs of society for dentistry services, but it needs improvements and better planning to cover the potential needs of society.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by IR.NASRME.REC.1397.2554. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MI and AJ contributed to designing the manuscript. AJ, MI, PN, FR, and MD collected the data. Data analyses were performed by AJ and MD. The final report and manuscript were written by AJ, PN, and MI. All authors participated and approved the manuscript, design, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education, Tehran, Iran (Grant No. 972554). The cost of the payment was spent on the design and data collection of the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors hereby express our gratitude to the contributors, researchers, and dentistry clinics in the city of Kermanshah and the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education, Tehran, Iran. All the participants, individuals, and organizations were also appreciated for their collaboration with this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

MSc, Master of Science.

References

Abdolmaleki, M., Yazdani, S., and Momtazmanesh, N. (2017a). Social accountable medical education: a concept analysis. J. Adv. Med. Educ. Prof. 5, 108–115. doi: 10.22037/jme.v16i2.16057

Abdolmaleki, M., Yazdani, S., Momtazmanesh, N., and Momeni, S. A. (2017b). Social accountable model for medical education system in iran: a grounded-theory. J. Med. Educ. 16, 55–70.

Armstrong, S. J., and Rispel, L. C. (2015). Social accountability and nursing education in South Africa. Glob Health Action. 8, 27879. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.27879

Batra, M., Shah, A. F., Dany, S. S., Rajput, P., and Mehar, J. (2015). Social accountability: the missing link in dental education. Int. Arch. Integrat. Med. 2, 137–140.

Brondani, M., Harjani, M., Siarkowski, M., Adeniyi, A., Butler, K., Dakelth, S., et al. (2020). Community as the teacher on issues of social responsibility, substance use, and queer health in dental education. PLoS ONE. 15, e0237327–e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237327

Chen, V., Foster Page, L., McMillan, J., Lyons, K., and Gibson, B. (2015). Measuring the attitudes of dental students towards social accountability following dental education – Qualitative findings. Med. Teach. 38, 1–8. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1060303

Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Losangeles: SAGE (2008). doi: 10.4135/9781452230153

Daher, A., Costa, L. R., and Machado, G. C. (2012). Dental students' perceptions of community-based education: a retrospective study at a dental school in Brazil. J Dent Educ. 76, 1218–1225. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2012.76.9.tb05377.x

Dehghani, M-. R., Azizi, F., Haghdoost, A., Nakhaee, N., Khazaeli, P., Ravangard, Z., et al. (2014). Situation analysis of social accountability medical education in university of medical sciences and innovative point of view of clinical faculty members towards its promotion using strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis model. Strides Dev. Med. Educ. 10, 403–412.

Emadzadeh, A., Mousavi Bazaz, S. M., Noras, M., and Karimi, S. (2016). Social accountability of the curriculum in medical education: a review on the available models. Fut. Med. Educ. J. 6, 31–37. doi: 10.22038/fmej.2016.8

Kassebaum, D. K., Hendricson, W. D., Taft, T., and Haden, N. K. (2004). The dental curriculum at North American dental institutions in 2002-03: a survey of current structure, recent innovations, and planned changes. J. Dent. Educ. 68, 914–931. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2004.68.9.tb03840.x

Lindgren, S., and Karle, H. (2011). Social accountability of medical education: aspects on global accreditation. Med. Teach. 33, 667–672. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.590246

McAndrew, M. (2010). Community-based dental education and the importance of faculty development. J. Dent. Educ. 74, 980–985. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2010.74.9.tb04953.x

Olsson, T. O., Dalmoro, M., da Costa, M. V., Peduzzi, M., and Toassi, R. F. C. (2021). Interprofessional education in the Dentistry curriculum: analysis of a teaching-service-community integration experience. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 26, 174–181. doi: 10.1111/eje.12686

Petterson, E. O., and Shea, N. (1972). Interaction of dental students with the educational environments provided by preventive and community dentistry; realism and reasonableness of the educational planning and implementation. J. Public Health Dent. 32, 2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1972.tb03934.x

Philibert, I., and Blouin, D. (2020). Responsiveness to societal needs in postgraduate medical education: the role of accreditation. BMC Med. Educ. 20, 309. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02125-1

Rohra, A., Piskorowski, W., and Inglehart, M. (2014). Community-based dental education and dentists' attitudes and behavior concerning patients from underserved populations. J. Dent. Educ. 78, 119–130. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2014.78.1.tb05663.x

Salehmoghaddam, A. R., Mazloom, S. R., Sharafkhani, M., Gholami, H., Emami Zeydi, A., Khorashadizadeh, F., et al. (2017). Determinants of social accountability in iranian nursing and midwifery schools: a delphi study. Int. J. Commun. Based Nurs. Midwifery 5, 175–187.

Sanaii, M., Mosalanejad, L., Rahmanian, S., Sahraieyan, A., and Dehghani, A. (2016). Reflection on the future of medical care: challenges of social accountability from the viewpoints of care providers and patients. J. Adv. Med. Educ. Profession. 4, 188–194.

Speziale, H. S., and Carpenter, D. R. (2011). Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. 15th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Strauss, R., Stein, M., Edwards, J., and Nies, K. (2010). The impact of community-based dental education on students. J Dent Educ. 74, S42–55. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2010.74.10_suppl.tb04980.x

Ventres, W., Boelen, C., and Haq, C. (2018). Time for action: key considerations for implementing social accountability in the education of health professionals. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 23, 853–862. doi: 10.1007/s10459-017-9792-z

Walker, M. P., Duley, S. I., Beach, M. M., Deem, L., Pileggi, R., Samet, N., et al. (2008). Dental education economics: challenges and innovative strategies. J. Dent. Educ. 72, 1440–1449. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2008.72.12.tb04622.x

Witton, R., and Paisi, M. (2021). The benefits of an innovative community engagement model in dental undergraduate education. Educ. Prim. Care 2021, 1–5. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2021.1947160

Keywords: dentistry education, accountability, society, qualitative study, Iran

Citation: Imani MM, Nouri P, Jalali A, Dinmohammadi M and Rezaei F (2023) A social accountable model for Iranian dentistry sciences education system: a qualitative study. Front. Educ. 8:993620. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.993620

Received: 13 July 2022; Accepted: 19 July 2023;

Published: 15 August 2023.

Edited by:

Andres Eduardo Gutierrez Rodriguez, Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (ITESM), MexicoReviewed by:

Bin Pang, Beijing Institute of Technology, ChinaHabibolah Khazaie, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Copyright © 2023 Imani, Nouri, Jalali, Dinmohammadi and Rezaei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amir Jalali, YV9qYWxhbGlAa3Vtcy5hYy5pcg==

Mohammad Moslem Imani

Mohammad Moslem Imani Prichehr Nouri2

Prichehr Nouri2 Amir Jalali

Amir Jalali