- Department of Education Studies, University of Warwick, Coventry, United Kingdom

Understanding what different stakeholders mean by “parental engagement” is vital as school leaders and policy makers increasingly turn to parental engagement to improve pupils’ outcomes. Yet, to-date, there has been little examination of whether parents’, teachers’, and school leaders’ conceptions of parental engagement match those used in research and policy. This case study used online questionnaires to explore the conceptions of parental engagement held by 103 parents and 40 members of staff at one large English primary school. The results showed that only a quarter of school staff conceptualized parental engagement in relation to learning at home and that school leaders appeared to overestimate the impact of school-based activities. This is at odds with previous research suggesting that it is parental engagement with learning in the home – rather than parents’ involvement with school - that is associated with pupil attainment. This suggests that there might be a striking mismatch in the way that parental engagement is conceptualized by researchers advocating for its efficacy, and by school staff devising and implementing parental engagement initiatives. It is vital to raise awareness of this possibility amongst practitioners, researchers, and policy makers because any such mismatch could result in the misdirection of time and resources and the undermining of parental engagement’s potential as a powerful tool for raising attainment and closing achievement gaps.

1. Introduction

Parental engagement has been linked to improvements in attendance, behavior, and academic achievement (Gorard et al., 2012; Jeynes, 2012, 2022; Wilder, 2014; Marti et al., 2018; Sylva et al., 2018). It has even been argued that - for primary school pupils – parental engagement has a bigger impact on pupil outcomes than school quality (Desforges and Abouchaar, 2003) or socioeconomic status (Jasso, 2007). As a result, the term parental engagement has been widely used within policy documents, research papers, and schools themselves (Barr and Saltmarsh, 2014). There appears to be an underlying assumption that the various stakeholders share an understanding of – and aspirations for – parental engagement. Yet, there has been little examination of whether parents’, teachers’, and school leaders’ conceptions of parental engagement are aligned with those of researchers and policymakers. This study aims to address this through an examination of how parental engagement is conceptualized by parents and school staff in England.

There has been no single definition of parental engagement in academic literature or educational policy. Wilder’s (2014) meta-synthesis found that published studies have defined parental engagement in relation to: parent-child communication about school; assisting with homework; having high aspirations; attending school events; reading to children; supervising; communicating with schools; and parenting style. Meanwhile, the focus in policy has been on the role of parents in relation to their children’s schooling (Barr and Saltmarsh, 2014) and parents’ entitlement to information from schools (Harris and Goodall, 2008). In the UK context, the influential Education Endowment Foundation (2018:1) have defined parental engagement as “the involvement of parents in supporting their children’s academic learning.” Whilst widely cited, the emphasis on academic learning implies a “school-centric” view of education. Meanwhile, Pushor and Amendt (2018) have argued convincingly that teachers and school leaders should take a much broader, “family-centric” view of education. A broader definition is offered by Abdul-Adil and Farmer (2006: 2), who suggest that parental engagement encompasses “any parental attitudes, behaviors, style, or activities that occur within or outside the school setting to support children’s academic and/or behavioral success.” The key strength of this “family-centric” (Pushor, 2015) definition is that it acknowledges the role of parents in relation to schools and in relation to their children’s learning outside of school. This paper therefore follows Goodall and Montgomery (2014) in recognizing that a whole spectrum of home- and school- based activity exists under the broad term of “parental engagement,” allowing respondents to define and exemplify the concept during data collection.

Daniel (2005) noted three other terms – parent involvement, parent participation and family-school partnerships – which are often used interchangeably with parental engagement. Parental engagement was chosen as our preferred term because it is widely recognized in the UK school context. However, as with other studies in the field (e.g., Goodall, 2013), the term “parent” is used to refer inclusively to all parents, carers, and guardians throughout.

Different conceptualizations of parental engagement affect pupil outcomes in different ways. Wilder’s (2014) meta-synthesis of nine meta-analyses found a positive relationship between parental engagement and academic achievement regardless of how these concepts were defined and measured. However, the relationship was strongest when defined as parental expectations for the academic achievement of their children. The same result has been reported in other meta-analyses (Jeynes, 2007; Axford et al., 2019), but controlled intervention studies targeting parental expectations are needed (Gorard, 2012). Meanwhile, Desforges and Abouchaar’s (2003) large-scale review of the parental engagement literature found that “at-home good parenting” had the largest effect on children’s achievement. This was true across all social classes and ethnic groups. This is consistent with evidence that effective parental engagement is usually rooted in the home (Melhuish et al., 2001; Sylva et al., 2003; Lehrl et al., 2020) whilst school-initiated, school-based parental engagement (such as attending school events or volunteering in school) does not consistently raise attainment (Okpala et al., 2001; Husain et al., 2016). Similarly, Harris and Goodall (2007) concluded that parents have the greatest impact on their children’s achievement through supporting learning in the home. It is therefore vital that all stakeholders have a shared understanding of parental engagement and recognize the types of activity that are – and are not – associated with pupil attainment. This is important because any mismatch could lead to misdirected efforts and resources in the push to maximize parental engagement and improve pupil outcomes.

1.1. The national policy context

The representation of parental engagement within the educational policy landscape is key here because the aim of this study is to investigate whether the conceptualization of parental engagement in research and policy matches the conceptualizations currently being used within schools in England. Moreover, the language of policy documents and policy demands placed on school are likely to influence how parental engagement is conceptualized by school leaders. The idea that parental engagement enhances educational outcomes is not new and has received significant, long-standing political attention (e.g., Plowden, 1967). Since then, the importance of parents in relation to schooling in England has been re-emphasized in a series of policy documents including “Excellence in Schools” (Department for Education and Employment, 1997), “Higher Standards, Better Schools for All” and “Every Parent Matters” (Department for Education and Skills, 2005, 2007). Most significantly for school leaders, parental engagement has been a recurring theme in successive versions of the Ofsted Inspection Framework (OIF).

From the first OIF, published in 1992, “parental links” have been a factor contributing to the overall judgment of schools (Elliot, 2012). More recently, the OIF has included the need for schools to “engage with parents and carers in supporting pupils’ achievement” (OFSTED, 2012: 16), “engage parents to the benefit of pupils” (OFSTED, 2015: 51), and “engage effectively with learners and others in their community, including – where relevant – parents” (OFSTED, 2019a: 13). It is clear from these statements that the intent is to boost pupil performance through parental engagement, but it is not clear what specific activities the statements aim to encourage. Is the policy aiming to encourage greater parental involvement in school-based activities? Is the intention to encourage schools to facilitate more learning in the home? Improve home-school communication? Or parent-voice in decision-making? This is ambiguous because of the numerous possible conceptions of parental engagement. Epstein (1987, 1995, 2001) identified the following types of parental engagement: parenting, communicating with school, volunteering in school, learning at home, decision making, and collaborating with the community. Whilst Epstein’s research was mostly conducted in the U.S., similar roles were identified by a U.K.-based review of parental engagement (Goodall and Vorhaus, 2011).

Although the formal policy statements within the OIF are ambiguous, the research summary published alongside the latest OIF suggests that the intention is to encourage “the involvement of parents in their children’s learning” through “providing practical advice on how parents can support learning at home” (OFSTED, 2019b: 38) and improving home-school communication. Strikingly, there is no suggestion that schools should be prioritizing parental attendance at school events. This is consistent with the evidence that it is parental engagement with learning in the home – rather than parents’ involvement with school – that is associated with increased pupil attainment (Okpala et al., 2001; Desforges and Abouchaar, 2003; Harris and Goodall, 2007).

From this, it appears that the conceptualization of parental engagement in U.K. educational policy broadly matches that of researchers. Namely, the emphasis is on facilitating parental engagement with pupils’ learning beyond the school gates. Alignment around this goal could present a powerful mechanism for improving pupil outcomes. However, the integration of parental engagement into educational policy in England has been inconsistent. Partnership with parents has only recently been added to the Headteachers’ Standards (Department for Education, 2020) and Core Content for Initial Teacher Training (Department for Education, 2019). As it stands, less than 10% of U.K. teachers have undertaken training related to parental engagement (Education Endowment Foundation, 2018).

1.2. Barriers to parental engagement

Many parents face material barriers to parental engagement – particularly in the form of attending school events. Working parents commonly express frustration that the timing of school events prevents them from engaging, whilst childcare and other caring responsibilities can pose similar difficulties (Harris and Goodall, 2008; UK Government, 2018). These barriers tend to be understood by school staff because many are parents whose jobs prevent them from attending their own children’s school events.

However, other barriers may be less tangible and less well understood, particularly those faced by parents from minority groups (Harris and Goodall, 2008; Conus and Fahrni, 2019). Treating parents as a homogeneous group is a flaw in most schools’ parental engagement policies (Crozier and Davies, 2007). This overlooks structural barriers to the parents’ involvement and fuels misconceptions amongst staff. For example, parents from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to be labeled as “difficult” or “hard to reach” whilst non-attendance at school events may be the result of language barriers or a lack of knowledge of the local education system (Harris and Goodall, 2008; Theodorou, 2008). Over three quarters of the “hard-to-reach” parents interviewed by Campbell (2011) described negative experiences during their own time as pupils and/or previous negative interactions with school staff or other parents on the school site.

Socio-economic status (SES) is another factor that predicts level of parental engagement (Payne, 2006). However, research suggests that what you do with your children is much more important than who you are (Dearing et al., 2006; Jasso, 2007). Hence, SES does not determine the level of parental engagement but mediates it through material deprivation and parental behaviors (Sacker et al., 2002; Hayes et al., 2016). Parents without post-16 education are less confident communicating with teachers and find educational jargon more off-putting (Williams et al., 2002). Low-income parents may also struggle to attend school events as a result of lack of childcare or transport (Harris and Goodall, 2008). Finally, low-income parents often feel stigmatized by teachers (Wilson and McGuire, 2021) whilst middle-class parents are more likely to view teachers as their equals and feel confident in the school environment due to their shared social capital (Harris and Goodall, 2008).

Whilst parent-teacher relationships are often the focus of parental engagement research, Barr and Saltmarsh (2014) concluded that school leaders set the tone for building and maintaining relationships with families and communities, particularly for marginalized parent groups. Meanwhile, other studies have emphasized the importance of “a welcoming front of house” including the office area and the office staff (OFSTED, 2011: 8). The current study therefore includes all these staff groups.

These issues affect parents’ engagement with schools, but they do not automatically impact engagement with their children’s learning (Goodall and Montgomery, 2014). For example, language barriers and being uncomfortable engaging with school staff might impact attendance at school events, but they do not necessarily prevent parents from engaging with their children’s learning in their own home and their own language. Smith and Wohlsetter (2009) suggest that school staff and policy makers generally lack awareness of the invisible strategies minority or low-income parents use to support their children’s education. Goodall (2015)2021 identifies a tendency for policy makers, educators, and researchers to adopt a deficit model when considering parents that are not visibly engaged with school. When parents do not engage in expected ways they are labeled as “hard to reach parents” (Munroe and Evangelou, 2012). This phrasing suggests that the problem lies with the parents rather than with the school. Pushor and Amendt (2018) believe that this is because staff are predisposed to look outward, toward parents, families, and the community to find explanations for perceived low levels of parent engagement (e.g., “these parents don’t care”). Meanwhile parents may feel that problems lie primarily with schools being unwelcoming or difficult to access (Crozier and Davies, 2007).

Parental role construction can also affect the extent to which parents engage with their child’s learning and their child’s school. Parents have different beliefs about their role in the education of their child (Jasso, 2007). This is likely to be related to parents’ sense of personal efficacy (Gubbins and Otero, 2020). Parents will only get involved to the extent that they feel their contributions will make a difference (Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2001). This is consistent with Desforges and Abouchaar’s (2003) conclusion that parental perception of their role and their levels of confidence in fulfilling it can determine the extent of their engagement.

1.3. The theoretical framework

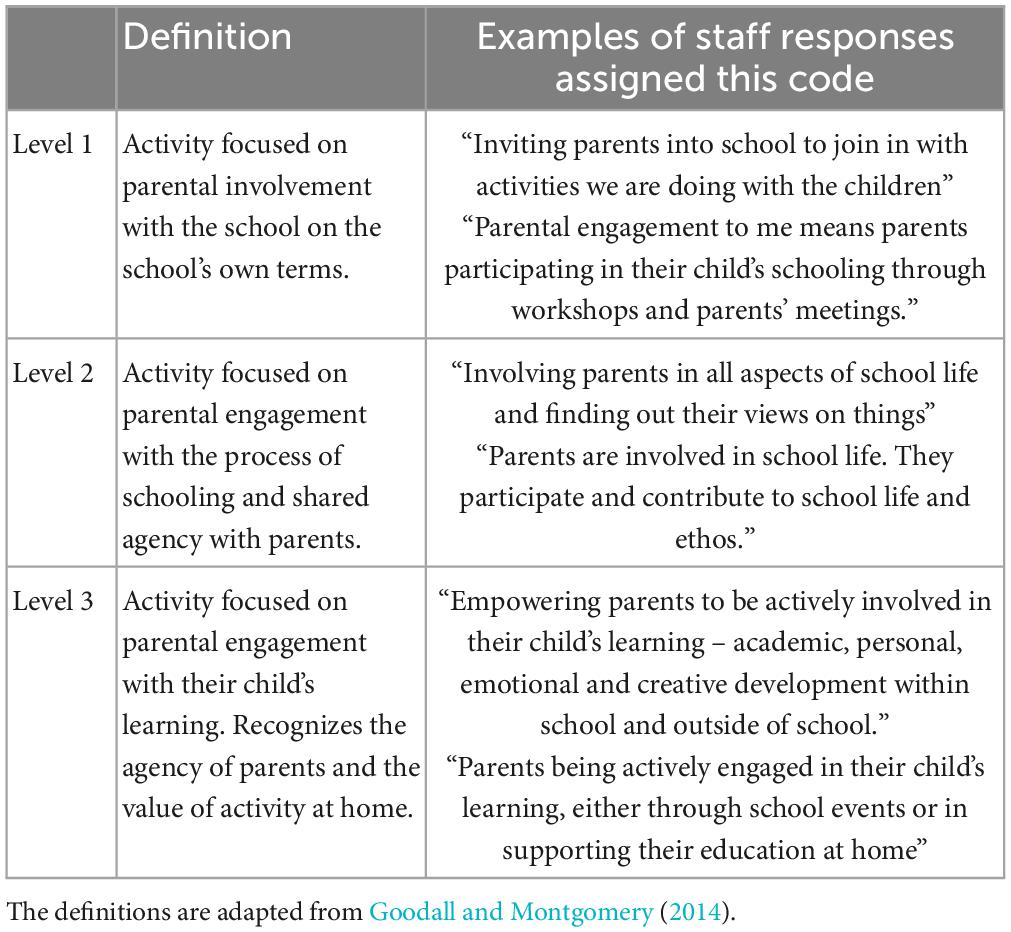

This study uses Goodall and Montgomery’s (2014) model of parental engagement. The model presents parental engagement as a continuum, with parental involvement and parental engagement at opposite ends of a spectrum. During parental involvement, activities tend to be school-based and school-directed. Examples could include teachers providing parents with information or inviting parents into classrooms to observe or support the teacher. This type of involvement can be appealing to school leaders because it is easy to initiate and measure. However, it is likely to have minimal impact on pupils’ outcomes (Harris and Goodall, 2007).

At the next point on the continuum, the focus moves from involvement with the school to involvement with the broader process of schooling. Agency is shared between parents and the school (Goodall and Montgomery, 2014). For example, a parent-teacher meeting where parents are partners in constructing a fuller portrait of the child. It is recognized that parents’ knowledge of their child is essential information that should be embraced to maximize the child’s potential (Moss et al., 1999).

Parental engagement directly with children’s learning is the final point on the continuum (Goodall and Montgomery, 2014). This is characterized by the attitude toward learning in the home. At this point, parents’ actions may still be based on information provided by the school, but the choice of action remains with the parent. Parents choose to engage with their child’s learning here because of their perceptions of their role as parents (Peters et al., 2007). At this stage parental engagement is unlikely to be located in school. Parents are engaged wherever they and their children discuss learning or engage in learning activities. This is consistent with earlier assertions that the most beneficial parental engagement is likely to be interactions between parent and child in the home (Melhuish et al., 2001; Desforges and Abouchaar, 2003; Sylva et al., 2003).

Goodall and Montgomery’s (2014) framework is used in this study because it provides a broad view of the spectrum of parental engagement activities, thus enabling us to compare different conceptions. For example, parents reading at home with their child, family museum visits, parents volunteering in school, and parents’ evenings can all be discussed in relation to the continuum. A purely school-centric or entirely family-centric model of parental engagement is unlikely to be able to cope with the perspectives of parents and school staff simultaneously. Furthermore, the model recognizes that parents can influence their children’s learning directly through engagement at home and indirectly through involvement with school (Desforges and Abouchaar, 2003). Thus, it allows us to consider both routes without conflating them. Finally, the smooth continuum between home and school avoids conceptualizing schools as closed, self-sufficient systems, and allows us to view them as open systems that engage in learning at the boundaries between families and communities (Price-Mitchell, 2009). This allows recognition of boundary-spanning activities such as home visits.

The aim of this study was to explore whether there is a shared understanding of the term “parental engagement” among parents and school staff at one large English primary school. It provides an in-depth exploration of how parental engagement is conceptualized by parents and staff through the following research questions:

(1) Which parental engagement activities are identified by parents and school staff?

(2) What are the perceived barriers to further parental engagement according to parents and school staff?

2. Methodology

This paper presents a case study examining parental engagement in its real-life school context. This was deemed to be the most appropriate research strategy because parental engagement is context-dependent (Crozier and Davies, 2007; OFSTED, 2011) and case studies are useful when “the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident” (Yin, 1981: 59). As a result, this case study focused on parental engagement at one school whilst utilizing multiple sources to allow for triangulation being respondents (Johnson, 1994).

2.1. The school context

The school examined in this case study is a large, state-maintained English primary school with over 600 pupils and 60 members of staff. The school has been given the pseudonym Hollyoaks. Hollyoaks was selected because the first author’s pre-existing relationship with the school enabled direct communication with parents and staff members, and a detailed understanding of the school’s context. It is also much larger than the average primary school which allowed the examination of subgroups such as comparing the views of senior leaders with those of class teachers and teaching assistants.

Hollyoaks is an inner-city school located in an area of the Midlands that has significant levels of deprivation. According to the 2021 census, 27% of working-aged residents had no qualifications and the proportion of residents experiencing long term unemployment (17%) was almost double the national average (9%; Office for National Statistics, 2021). Consequently, over 40% of pupils at Hollyoaks are eligible for free school meals. The percentage of residents from minority ethnic groups (50%) is more than double the national average (19%; Office for National Statistics, 2021). Consequently, the schools’ pupils have diverse ethnic backgrounds. The largest groups within the school are Pakistani, White British and Romani. This is important because minority and low-income families may experience different barriers to parental engagement (Weiss et al., 2003; Harris and Goodall, 2008; OFSTED, 2011).

2.2. Ethics

This study received ethical approval from the Department of Education Studies ethics committee of the University of Warwick. In accordance with British Educational Research Association guidelines (British Educational Research Association [BERA], 2018), the school has been given the pseudonym Hollyoaks to protect the anonymity of pupils, parents, and staff. Voluntary informed consent was obtained from the Headteacher in writing prior to starting the study, and then from each individual staff and parent respondent at the start of the survey. Participation was optional.

2.3. Participants

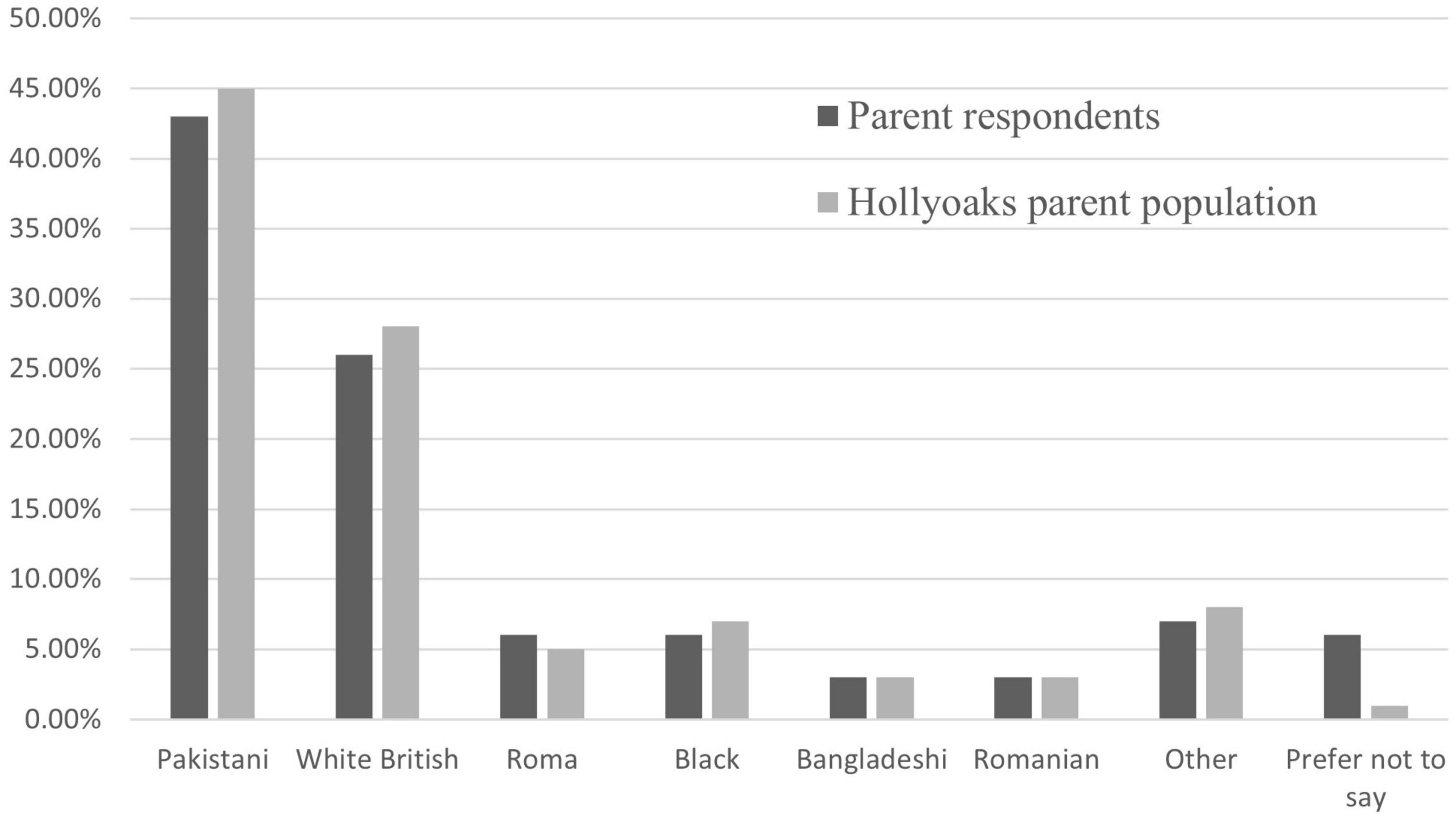

A total of 103 parents from Hollyoaks completed the online parent questionnaire. The respondents had a total of 172 children attending Hollyoaks. The parental response rate was 30%. Figure 1 shows the ethnicity breakdown of the parent respondents.

Figure 1. A graph showing the ethnicity breakdown of the parent respondents compared with the ethnicity breakdown of the Hollyoaks parent population.

Forty members of staff from Hollyoaks completed the online staff questionnaire (5 senior leaders, 26 class teachers, 11 teaching assistants, 2 office staff, 6 other staff). This represented a response rate of 63% which compares favorably to other school staff surveys in the literature (e.g., Sturman and Taggart, 2008 [44%]; Elton-Chalcraft et al., 2017 [10–45%]; Fotheringham et al., 2022 [6%]).

2.4. Measures

A staff questionnaire and parent questionnaire were developed for the purpose of collecting primary data for this study. Each questionnaire consisted of eight questions. One open question was used at the start of the staff questionnaire to elicit detailed descriptions of parental engagement in the participants’ own words. The rest consisted of closed questions (Likert scales and multiple choice) to facilitate comparison between the responses of different groups. An optional comment box was added to each closed question so that participants were able to expand on or clarify their responses. The content of the questionnaire was driven by the research questions and informed by the findings of the literature review. For example, a matrix was used to ask staff and parents to consider the perceived impact of different types of parental engagement. The activities for consideration in the questionnaire were taken from both ends of Goodall and Montgomery’s (2014) continuum.

The draft questionnaires were piloted with eight teachers and twelve parents from other schools and several questions were re-worded as a result. For example, “in the last 12 months, have you taken your child to visit educational places” was found to be ambiguous and was therefore edited in the final version to ask about museums and libraries.

2.5. Procedures

With the permission of the Headteacher, a link to the staff questionnaire was included as a standing item on Hollyoaks’ pre-existing daily briefing emails sent to all staff. Verbal reminders were also given during weekly staff meetings. Meanwhile, all parents were invited to complete the parent questionnaire via Hollyoaks’ existing online parent communication system. This enabled most parents to complete the survey at home on their own devices. Parents were also given the opportunity to complete the survey on school iPads in the playground before or after school in order to provide equal opportunity to parents who could not access the internet and/or a suitable device at home. Both surveys remained open for 4 weeks.

2.6. Data analysis

The responses from the parent survey and the staff survey were first analyzed separately in order to identify which types of parental engagement were valued by each group. Views from both sets of respondents were then compared for the analysis of barriers to parental engagement. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize and compare responses to the closed questions.

Deductive thematic analysis was used to analyze the free-text descriptions of strong parental engagement. Staff were asked, “In your own words, please explain as fully as possible what you think we mean by the term “parental engagement.” Include examples of what you think strong parental engagement looks like.” Their free-text responses were coded using Goodall and Montgomery’s (2014) continuum as either level 1, level 2, or level 3 (see Table 1). Using these pre-defined levels as a framework for analysis allowed a balanced approach advocated by Janesick who argues that the analysis of qualitative data requires the mind to be “open but not empty” Janesick (2000: 384). Each response was coded by the first author and then independently coded by a second person, blind to the first author’s ratings. The codes assigned by the two raters were then cross-checked. The codes given were consistent for 32/40 responses (80%). For the responses where different codes were assigned, the two raters reached an agreement through discussion with reference to the original definitions.

3. Results

3.1. What sort of parental engagement do school staff identify?

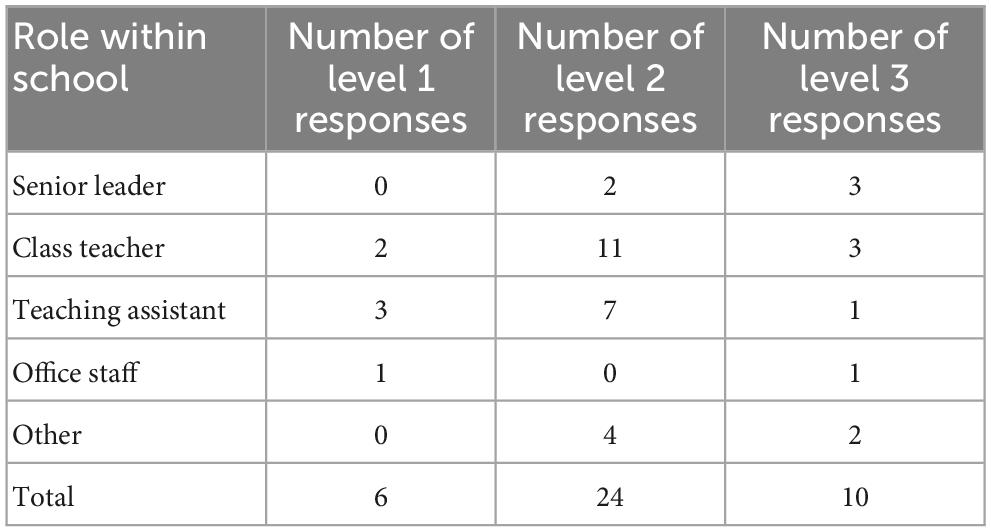

As a result of coding process outlined above, 15% of staff conceptualizations of parental engagement were coded at level 1, 60% at level 2, and 25% at level 3. This suggests that staff currently have mixed views of parental engagement at Hollyoaks. A sizeable minority of staff appear to believe that the goal of parental engagement is to increase parent attendance at school events. Just one quarter of staff expressed aspirations for parental engagement which included empowering parents to engage with their children’s learning beyond the school gates.

The frequency of each type of response was broken down according to staff group (see Table 2). It is encouraging to note that no level 1 responses were given by senior leaders. However, they still fall short of consensus in their conceptions of parental engagement as 2/5 made no reference to parental engagement with learning at home. The wide spread of responses in all groups suggests that there is work to be done in ensuring that all staff have shared understanding of what is meant by parental engagement and the future aspirations for Hollyoaks in this area.

Table 2. An overview of the number of responses coded at each level, broken down by role within school.

Next, staff members were asked to consider the impact on learning of 15 different parental engagement activities. The purpose of this question was not to attempt to evaluate the actual impact of each activity on learning, but rather to consider whether staff perceptions are consistent with the growing evidence that level 3 activities are more impactful than level 1 or 2. Overall, parents reading with their children at home, encouraging their children to access educational resources, and taking their children to educational places were rated by staff as having the greatest impact on learning. Parents volunteering in school and attending family learning, performances and exhibitions in school were considered to have the least impact on learning. This suggests that most staff are on some level aware that what parents do with their children at home is more important than their engagement with school-based activities.

Comparing the impact scores given by different staff groups revealed that senior leaders tended to believe that school-based activities were having a greater impact on learning than the impact perceived by class teachers or teaching assistants. For example, for parent-to-school days (where parents observe lessons) all senior leaders believed there was a strong positive impact on learning compared to one third of teachers. The literature review indicated that school-based, school-initiated activities such as parent-to-school days are likely to have little impact on learning which suggests that senior leaders are overestimating the impact of this initiative rather than teachers underestimating it. Leaders may overestimate the positive benefits of their own initiatives. Alternatively, senior leaders may be more likely to only consider the positive side of school-based initiatives whilst teachers and teaching assistants may be balancing the positives with the realities of having parents and young siblings in school. Some teachers chose to add free text comments which included references to lessons being disrupted by babies crying and parents taking phone calls in crowded classrooms.

Interestingly, the reverse pattern was found for most parent-initiated activities with teachers believing the impact was stronger than senior leaders. For example, two thirds of teachers indicated that parents taking their children to educational places (e.g., museums, libraries etc.) had a strong positive impact on learning compared to just one of the senior leaders. Again, previous research supports the views of teachers rather than those of senior leaders.

3.2. What sort of parental engagement do parents identify?

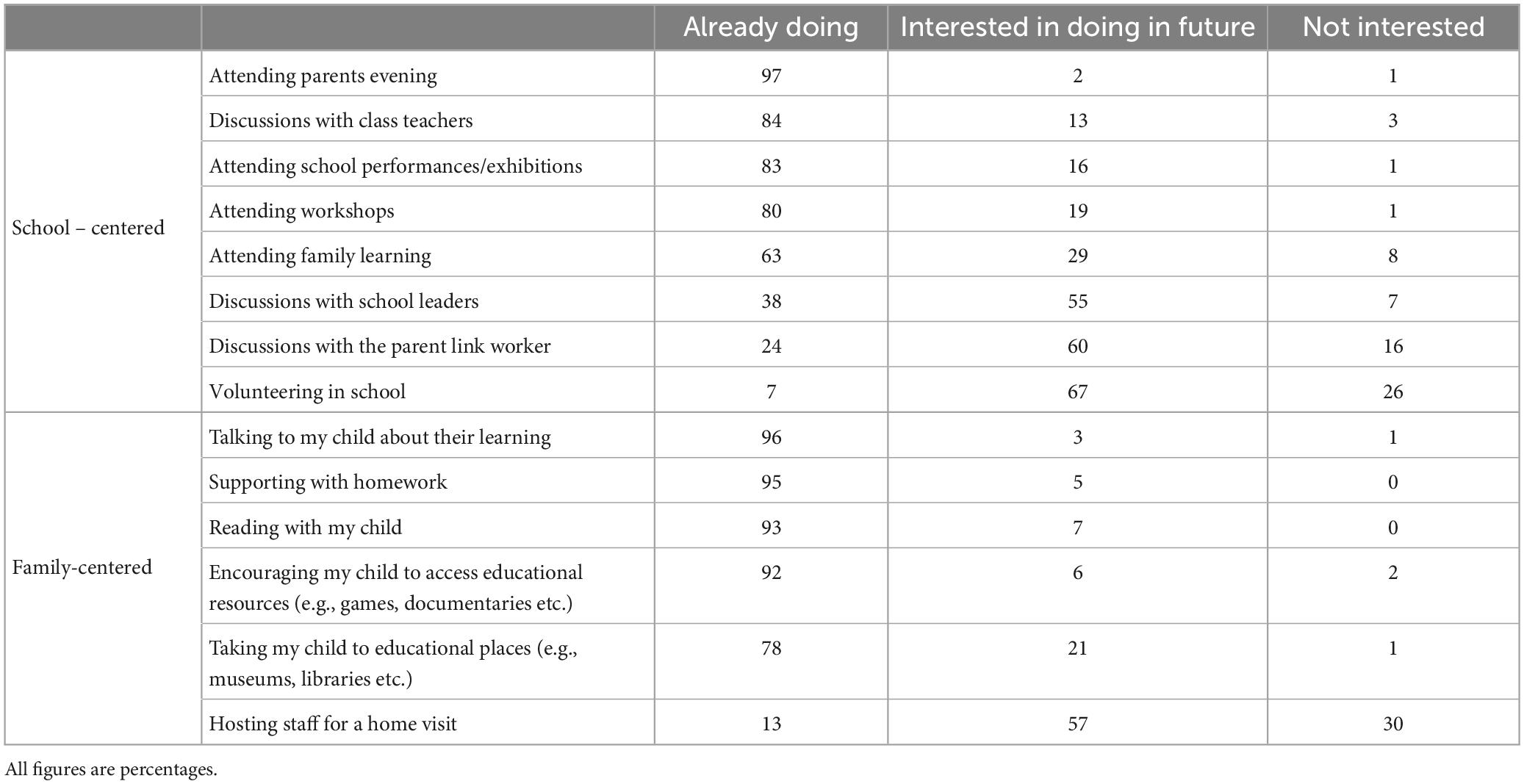

Parents were asked to consider a list of ways they might support learning and to indicate for each activity whether they had done it in the last 12 months, had not done it but would be interested in future, or were not interested doing it. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. An overview of parent responses to questions about different ways that parents might engage with learning (n = 103).

Table 3 shows that vast majority of parents already engage with learning through parents evening, supporting with homework, reading at home, encouraging access to educational resources, and talking to children about their learning. This suggests that parents value these types of engagement – most of which are family-centered. The high percentages interested in volunteering in school, having discussions with staff, and attending events (e.g., exhibitions, workshops, performances and family learning) in future suggests that parents also value school-based parental engagement opportunities. However, given that family-centered engagement is likely to have the greatest impact, the most important areas are the family-centered activities that parents are interested in engaging with. For example, 21% of parents had not taken their child to a museum or library but were interested in doing so and 57% would be interested in hosting staff for a home visit.

Parents were invited to add any ways in which they engaged with their children’s learning that were not already covered by the questionnaire. Most comments repeated activities already discussed (e.g., “speaking to teachers at least once a week” and “encouraging children to read more”). However, one comment suggested that parents support learning through “discussions with other parents.” Parent-to-parent engagement with pupils’ learning is an interesting consideration as it appears to be largely absent from the parental engagement literature. Its strength is in it being entirely parent led but schools may be able to support or facilitate engagement of this kind through providing space and time for parent networks.

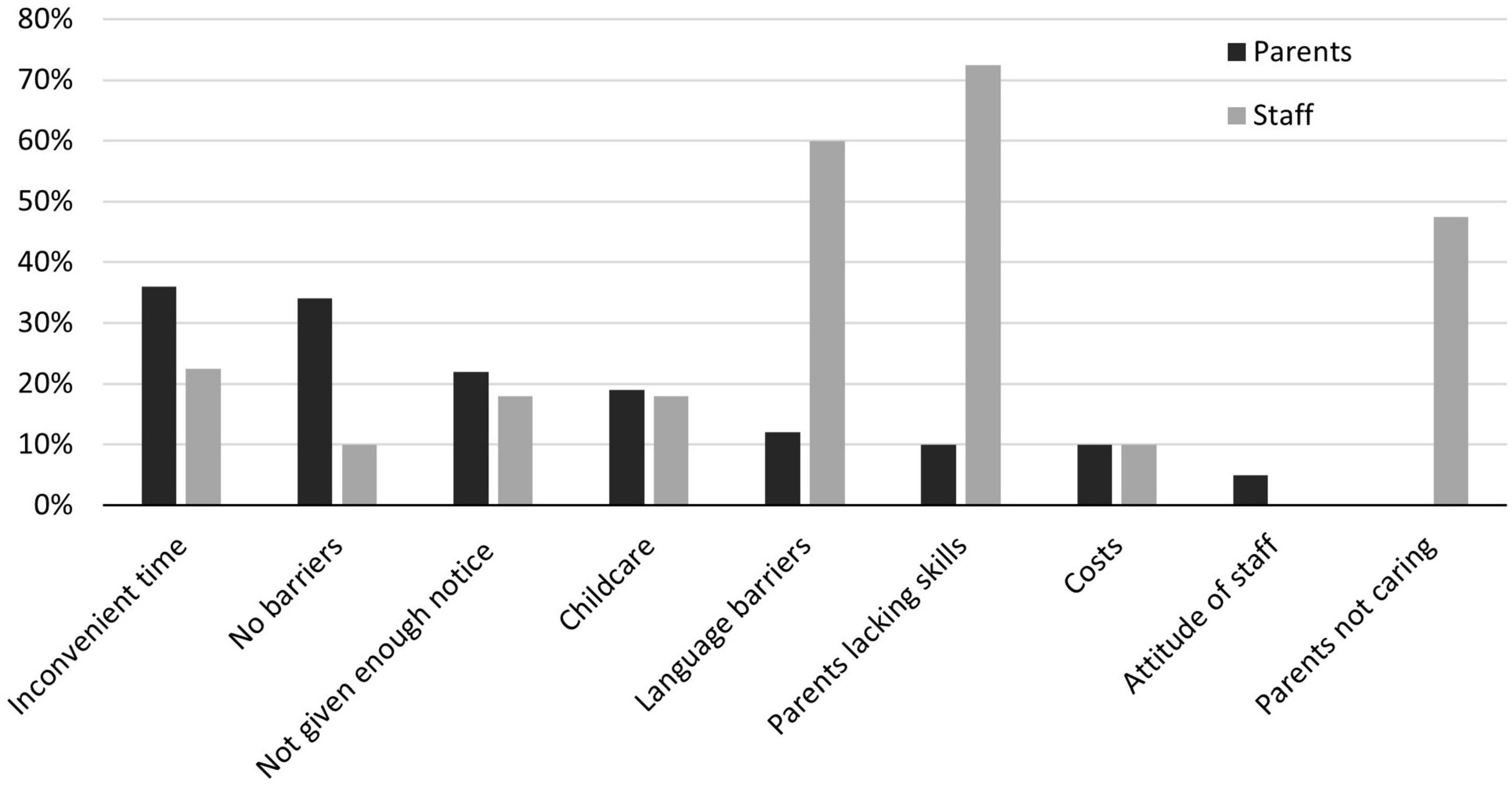

3.3. What are the perceived barriers to parental engagement?

Staff and parents were asked to indicate their perceived barriers to greater parental engagement. There were striking differences between the perceptions of the two groups (see Figure 2). The two most common barriers identified by parents were school-based issues around the timing of events and lack of notice. Staff underestimated both of these barriers and generally perceived the main barriers to be shortcomings of the parents. Three quarters of staff said that parents lacked the skills to support their children’s education and nearly half of staff thought that parents not caring about their children’s education was a significant barrier.

Figure 2. An overview of the barriers to parental engagement as perceived by staff and parents at Hollyoaks.

There were large within-group differences in staff perceptions of barriers. Encouragingly none of senior leaders said that parents do not care, however this view was held by half of teachers and teaching assistants, and all office staff. The opposite pattern was observed in group differences in response to parents not having the skills to support their children’s education. All senior leaders but only half of teachers considered this to be a barrier. Interestingly, only 10% of parents thought that they might lack the skills to support their child’s education. It is vital that school staff empower all parents to believe in their own ability to make a difference, but this will be difficult to do whilst none of the senior leaders believe it themselves.

Language barriers was the final area in which there was significant discrepancy between staff and parents. Only 10% of parents considered language to be a significant barrier but this is likely to be skewed by the fact that completion of the online questionnaire required competency in English. For staff, 60% indicated that language was a barrier. Most staff considered the responsibility for resolving this to be on the parents rather than on the school. Crucially, 4/5 of senior leaders said that not enough parents speak English whilst none of them thought that not enough staff spoke Urdu etc. This outlook is reflected in decisions taken at Hollyoaks. For example, the school hosts ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) classes for parents but does not translate home-school communications.

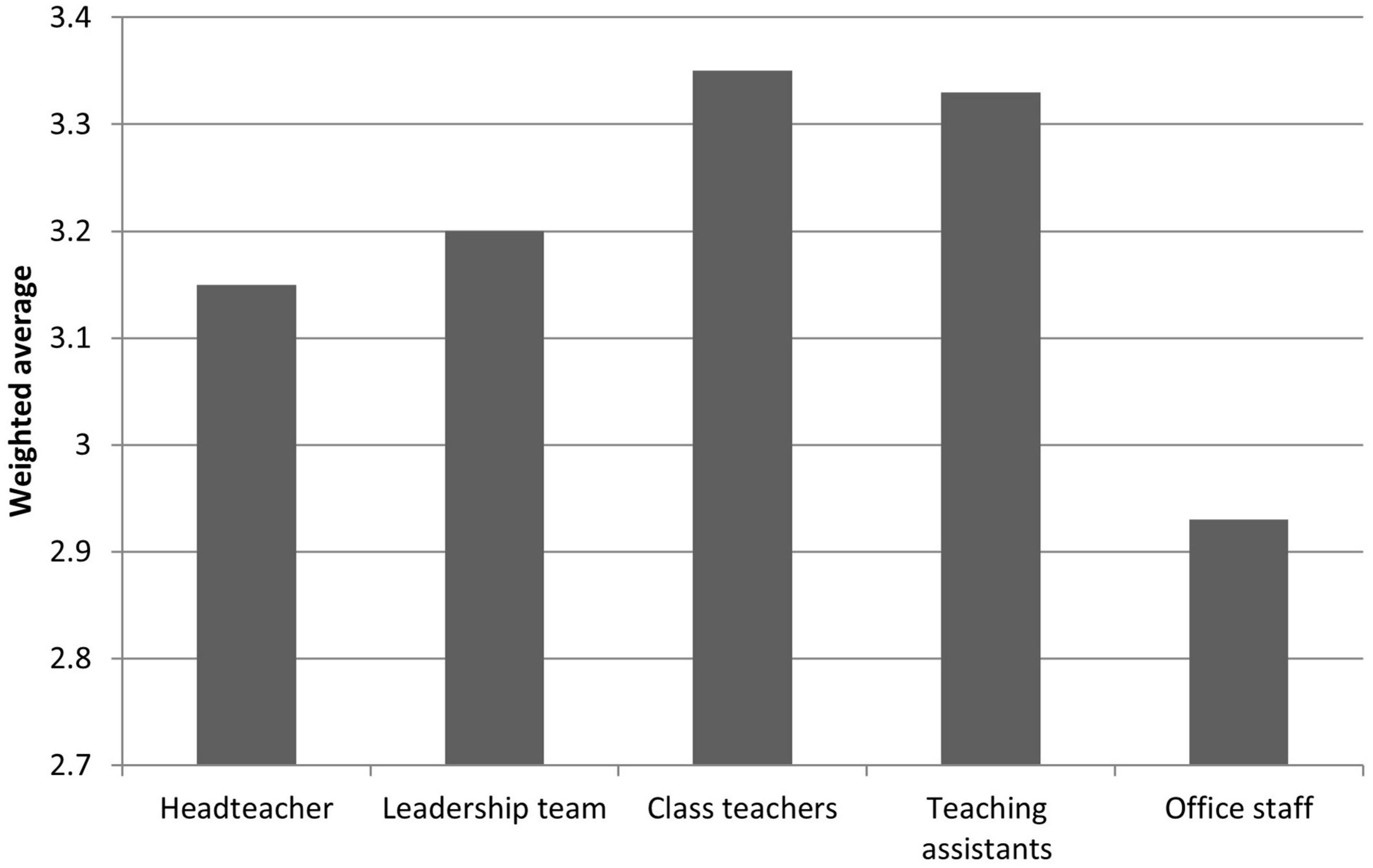

Despite this, 90% of parents said they felt welcome in school. Parents were then asked to what extent they felt that parental engagement was valued by different staff groups at Hollyoaks. Parents responded on a 4-point Likert scale for each staff group. Weighted averages were calculated and are compared in Figure 3. Some researchers caution against calculating numerical averages from Likert scales because it assumes that the “distance” between each point on the scale is equal (Göb et al., 2007). However, in Figure 3 the point of interest is not the absolute value of the weighted average, but the relative score given to each group. Parents felt that their engagement was most valued by class teachers, followed by TAs. A smaller percentage of parents agreed that the headteacher and senior leadership team valued parental engagement. Parents felt least valued by office staff.

Figure 3. A graph showing the extent to which parents agreed that parental engagement is valued by each staff group at Hollyoaks.

4. Discussion

This study examined the conceptualization of parental engagement among parents and school staff. The data showed that three quarters of staff conceptualized parental engagement in relation to participation in school events and relationships with teachers. Just one quarter of school staff described parental engagement in terms of the relationship between parents and their children’s learning beyond the school gates. Meanwhile, almost all parents felt that they regularly engaged through home-based activities, including reading at home, encouraging access to educational resources, and talking to children about their learning. There were also clear differences between the barriers to engagement identified by parents and those identified by school staff. This suggests that parents and school staff do not have a shared conception of – or aspirations for – parental engagement even within the same school.

The school-centered conceptions being used by school staff are concerning because there is strong, pre-existing evidence that parents contribute most to pupil outcomes through engaging with their learning outside of school (Melhuish et al., 2001; Desforges and Abouchaar, 2003; Sylva et al., 2003; Harris and Goodall, 2007). Senior leaders in this study also appeared to overestimate the impact of school-based activities despite evidence that the impact of school-based events is often minimal (Okpala et al., 2001; Desforges and Abouchaar, 2003; Harris and Goodall, 2007; Husain et al., 2016). Researchers and policy makers have suggested that schools should “shift from simply involving parents with the school to enabling parents to engage themselves more directly with their children’s learning” (OFSTED, 2011: 8) but the finding here suggest that some schools may still be focused on school-centric parental involvement. This may be related to the fact that less than 10% of teachers have had any training in relation to parental engagement (Education Endowment Foundation, 2018).

All parents in this study were keen to engage directly with their children’s learning. This is consistent with the findings of Harris and Goodall (2008), Theodorou (2008), and Campbell (2011) who have previously shown that parents care deeply about their children’s education, including those who face barriers to engaging with schools. This study has gone further in also identifying several areas in which greater facilitation by the school is likely to be welcomed by parents. For example, 99% of parents said they want to take their children to museums and libraries but only 78% are currently doing so. In response, the school could host parental engagement events at local libraries or museums. These could be organized in partnership with parents to ensure that the format, timing, and communication of the event allow for maximum engagement. This represents an exciting opportunity for the school to facilitate parental engagement with learning, in response to an expression of interest from parents themselves.

Similarly, 98% of parents are interested in encouraging their children to access educational resources but only 92% have done this at any point in the last 12 months. This provides an opportunity for Hollyoaks to “shift to encouraging parental engagement with learning in the home through providing levels of guidance and support which enable such engagement to take place” (Harris and Goodall, 2008: 286). In response, Hollyoaks could compile examples of free educational, age-appropriate games and apps. The school could also signpost parents to documentaries or home-learning resources that complement each in-school topic or which may just be of general interest to families. They could also host the infrastructure for parents to be able to share their own ideas with each other as the foundation for building parent-parent networks.

In addition to implementing evidence-based initiatives, school leaders must play a key role in fostering a culture that allows parental engagement to thrive (Pushor and Amendt, 2018). However, in the current study, staff perceived the biggest barriers to parental engagement to be: parents not attending school-based events (78%), parents not having the right skills to support their children’s education (73%), and parents not caring about their children’s education (48%). This is consistent with Goodall’s (2015) conclusion that educators tend to adopt a deficit model when considering parents that are not visibly engaged with school, whilst parents may feel that problems lie primarily with the school (Crozier and Davies, 2007). Pushor and Amendt (2018) suggested that school leaders must lead a transformation whereby school staff look at their own disposition, actions, or inactions to find reasons for perceived low parental engagement and to generate solutions (e.g., “perhaps if I had made a home visit rather than expecting parents to come here”).

It is vital that school staff empower all parents to believe in their own ability to make a difference (Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2001; Desforges and Abouchaar, 2003; Peters et al., 2007). However, in this study, all of the senior leaders believed that parents lacked the required skills to support learning and therefore they are unlikely to be able to empower parents in the community they serve. Significant attempts must be made to tackle misconceptions among teachers and school leaders if the full potential of parental engagement as a tool for school improvement is to be realized. This is likely to require staff training (Goodall and Vorhaus, 2011) and scaffolded opportunities for staff and parents to mix authentically within the local community (Pushor and Amendt, 2018).

Parental engagement training could be of benefit to all school staff, not just teachers. In this study, parents felt most welcome by class teachers and TAs. This appears to be in contrast with Barr and Saltmarsh’s (2014) conclusion that the headteacher and leadership team set the tone for how valued parents feel within school. However, teachers and TA in primary schools may have more opportunities for regular, informal interactions with parents, whilst headteachers and senior leaders only have personal interactions with parents in response to concerns such as poor behavior or attendance. Furthermore, parents felt that their engagement was valued least by office staff. This is concerning given the recognized importance of office staff in relation to the parent-school relationship.

5. Limitations and suggestions for further research

Caution should be exercised in drawing generalizations from this data. The case study design means that the data produced is rooted in a specific context. Data from larger, representative samples is needed to determine whether school-centric definitions of parental engagement might be a national – or indeed international – problem. The findings have direct implications for school leaders at Hollyoaks. Leaders at other schools should consider the extent to which the results and recommendations might apply to their own context. School leaders may wish to use the procedures outlined here to collect similar data from their own staff and parents to facilitate evidence-based action.

Future research with larger samples should also explore the perceptions of different parent groups, including parents of children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND). This particular group of parents may have different perspectives on parental engagement because the SEND code of practice in England places a statutory duty on schools to take a family-centric approach and to involve parents in decision making (Department for Education, 2015). Parents of children with SEND may also face unique barriers to parental engagement including the lack of “school gate culture” in special schools (Spear et al., 2022) and a lack of confidence in the education system as a result of negative experiences (Lamb, 2009).

There is also the possibility of response bias in the parent sample. Whilst the ethnicity breakdown presented in Figure 1 does not suggest a skewed sample, it remains possible that the sample was not representative based on other, unmeasured characteristics. For example, those with a pre-existing interest in the topic, those with higher literacy levels and those with internet access may have been more likely to respond to the questionnaires. This risk was minimized by offering all parents the opportunity to complete the survey on iPads in the playground but cannot be entirely discounted. As with all self-report surveys, social desirability bias is also a possibility. The anonymous nature of the survey removes the motivation for participants to deliberately present themselves in a favorable light, but participants may still have done so subconsciously. However, if present, one would expect the direction of this bias to predispose staff and parents to report alignment with research and policy. Social desirability bias is therefore very unlikely to undermine the key findings of this study.

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in significant changes to the way in which parents engaged with schools and with learning. Future research should examine whether this has had any lasting impact of the ways in which parental engagement is conceptualized by parents and school staff. This may require increased scrutiny of the role played by technology, along with the opportunities and barriers this creates (e.g., See et al., 2021; Baxter and Toe, 2023).

6. Implications

This study has challenged the assumption that stakeholders in education possess a shared understanding of what effective parental engagement is and what the barriers are to achieving this. The findings suggest that there may currently be a worrying mismatch in the way that parental engagement is conceptualized by researchers and policy makers advocating for its efficacy, and the conceptions of school staff devising and implementing parental engagement initiatives. If school leaders continue to confuse parental involvement with school and parental engagement with learning, then resources are likely to continue to be disproportionately allocated toward school-based events aimed at parents’ relationships with schools, rather than supporting family-centered engagement with learning. If this happens, efforts will not lead to the progress expected and parental engagement as a strategy for school improvement will be de-valued (Cowley and Cowley, 2013).

To rectify this, school leaders, teachers, teacher educators, parents, researchers, and policy makers need a shared conceptualization of parental engagement, centered on the relationship between parents and their children’s learning. Inclusion in initial teacher training and the Headteachers’ standards could be a starting point for disseminating this widely. For policy makers, this presents an opportunity to unite thousands of professionals behind a family-centric conceptualization of parental engagement and equip teachers with the knowledge, skills and attitudes needed to promote parental engagement as a mechanism for improving pupil outcomes.

The findings here suggest that some staff may need to re-examine their beliefs about parents and address misconceptions so that mutually respectful partnerships can be built. For teachers, the findings of this study may serve as a starting point in examining their own conceptualization of parental engagement and considering whether deficit views of parents could be preventing them from building effective partnerships (Goodall, 2021). Meanwhile, school leaders may wish to reflect on the conceptions and possible misconceptions that may be present in their setting. For example, on whether policies and practices reflect a family-centric or school-centric conceptualization of parental engagement, and whether parental engagement training for staff could be beneficial.

This study has also provided detailed information about the views of parents and school staff in relation to specific parental engagement activities. Responses from parents indicate that there may be opportunities to refocus parental engagement efforts on learning in the home and community, rather than on surface-level engagement with the school itself. For example, schools could; provide educational resources to support the home learning environment, facilitate interaction between families and educational places such as museums and libraries, and support parent-to-parent networks.

7. Conclusion

Our study examined whether there was a shared understanding of parental engagement among parents and school staff in the context of one UK-based primary school. Our findings pointed toward a striking mismatch concerning how parental engagement is currently being conceptualized in related research and school staff perceptions who are at the forefront of developing and implementing parental engagement activities.

In highlighting disparities in how parental engagement is currently conceptualized by different groups, namely teachers and parents, and providing recommendations aimed at reaching a shared understanding, it is hoped that this study can contribute to the potential of parental engagement being harnessed more effectively.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because participant consent was only sought for specific named researchers to access the data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to CJ, Yy5qb25lcy4yN0B3YXJ3aWNrLmFjLnVr.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Education Studies Ethics Committee, University of Warwick. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CJ contributed to the conception and design of the study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. OP contributed to the substantial redrafting of the manuscript and revisiting of the intellectual content. Both authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The work of CJ was supported by an ESRC studentship (award number ES/P000711/1).

Acknowledgments

We thank the parents and staff at Hollyoaks who generously gave their time to participate in this research. We also thank Sue Johnstone-Wilder who supervised the thesis from which this manuscript arose.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdul-Adil, J. K., and Farmer, A. D. (2006). Inner-city African American parental involvement in elementary schools: getting beyond urban legends of apathy. School Psychol. Q. 21, 1–12. doi: 10.1521/scpq.2006.21.1.1

Axford, N., Berry, V., Lloyd, J., Moore, D., Rogers, M., Hurst, A., et al. (2019). How can schools support parents’ engagement in their children’s learning? Evidence from research and practice. London: Education Endowment Foundation.

Barr, J., and Saltmarsh, S. (2014). ‘It all comes down to the leadership’: the role of the school principal in fostering parent-school engagement. Educ. Manag. Administr. Leadersh. 42, 491–505. doi: 10.1177/1741143213502189

Baxter, G., and Toe, D. (2023). ‘Parents don’t need to come to school to be engaged:’ teachers use of social media for family engagement. Educ. Action Res. 31, 306–328. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2021.1930087

British Educational Research Association [BERA] (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research (online), 4th Edn. London: British Educational Research Association.

Campbell, C. (2011). How to involve hard-to-reach parents: encouraging meaningful parental involvement with schools. Nottingham: National College for School Leadership.

Conus, X., and Fahrni, L. (2019). Routine communication between teachers and parents from minority groups: an endless misunderstanding? Educ. Rev. 71, 234–256. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2017.1387098

Cowley, A., and Cowley, D. (2013). An investigation into OFSTED’S approach to parental engagement within the inspection frameworks. Available online at: https://issuu.com/engagementineducation/docs/ofsted_and_parental_engagement (accessed June 2, 2022).

Crozier, G., and Davies, J. (2007). Hard to reach parents or hard to reach schools? A discussion of home–school relations, with particular reference to Bangladeshi and Pakistani parents. Br. Educ. Res. J. 33, 295–313. doi: 10.1080/01411920701243578

Daniel, G. (2005). “Parent involvement in children’s education: implications of a new parent involvement framework for teacher education in Australia,” in Teacher education: local and global, ed. M. Cooper (Queensland, AU: Griffith University).

Dearing, E., Simpkins, S., Kreider, H., and Weiss, H. (2006). Family involvement in school and low-income children’s literacy: longitudinal associations between and within families. J. Educ. Psychol. 98, 653–664. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.653

Department for Education (2015). Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years. London: Department for Education.

Department for Education and Skills (2005). White paper: higher standards, better schools for all. London: HMSO.

Desforges, C., and Abouchaar, A. (2003). The impact of parental involvement, parental support and family education on pupil achievement and adjustment: a literature review. London: Department for Education.

Education Endowment Foundation (2018). Working with parents to support children’s learning. London: Education Endowment Foundation.

Elliot, A. (2012). Research and information on state education: twenty years inspecting English schools – OFSTED 1992-2012. London: RISE.

Elton-Chalcraft, S., Lander, V., Revell, L., Warner, D., and Whitworth, L. (2017). To promote, or not to promote fundamental British values? Teachers’ standards, diversity and teacher education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 43, 29–48. doi: 10.1002/berj.3253

Epstein, J. (1987). Parent involvement: what research says to administrators. Educ. Urban Soc. 19, 119–136. doi: 10.1177/0013124587019002002

Epstein, J. (1995). School/family/community partnerships: caring for the children we share. Phi Delta Kappan 76, 701–712. doi: 10.1177/003172171009200326

Epstein, J. (2001). Building bridges of home, school, and community: the importance of design. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk 6, 161–168. doi: 10.1207/S15327671ESPR0601-2_10

Fotheringham, P., Harriott, T., Healy, G., Arenge, G., and Wilson, E. (2022). Pressures and influences on school leaders navigating policy development during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. Educ. Res. J. 48, 201–227. doi: 10.1002/berj.3760

Göb, R., McCollin, C., and Ramalhot, M. F. (2007). Ordinal methodology in the analysis of likert scales. Qual. Quant. 41, 601–626. doi: 10.1007/s11135-007-9089-z

Goodall, J. (2013). Parental engagement to support children’s learning: a six point model. Schl Leadersh. Manag. 33, 133–150. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2012.724668

Goodall, J. (2015). Ofsted’s judgement of parental engagement: a justification of its place in leadership and management. Manag. Educ. 29, 172–177. doi: 10.1177/0892020614567246

Goodall, J. (2021). Parental engagement and deficit discourses: absolving the system and solving parents. Educ. Rev. 73, 98–110. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2018.1559801

Goodall, J., and Montgomery, C. (2014). Parental involvement to parental engagement: a continuum. Educ. Rev. 66, 399–410. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2013.781576

Goodall, J., and Vorhaus, J. (2011). Review of best practice in parental engagement. London: Department for Education.

Gorard, S. (2012). Querying the causal role of attitudes in educational attainment. Int. Scholarly Res. Notices Educ. 2012:501589. doi: 10.5402/2012/501589

Gorard, S., See, B., and Davies, P. (2012). The impact of attitudes and aspirations on educational attainment and participation. New York, NY: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Gubbins, V., and Otero, G. (2020). Determinants of parental involvement in primary school: evidence from Chile. Educ. Rev. 72, 137–156. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2018.1487386

Harris, A., and Goodall, J. (2007). Engaging parents in raising achievement. do parents know they matter?. London: Department for Children, Schools and Families.

Harris, A., and Goodall, J. (2008). Do parents know they matter? Engaging all parents in learning. Educ. Res. 50, 277–289. doi: 10.1080/00131880802309424

Hayes, N., Berthelsen, D. C., Nicholson, J. M., and Walker, S. (2016). Trajectories of parental involvement in home learning activities across the early years: associations with socio-demographic characteristics and children’s learning outcomes. Early Child Dev. Care 188, 1405–1418. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2016.1262362

Hoover-Dempsey, K., Battiato, A., Walker, J., Reed, R., Dejong, J., and Jones, K. (2001). Parental involvement in homework. Educ. Psychol. 36, 195–192. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3603_5

Husain, F., Jabin, N., Haywood, S., Kasim, A., and Paylor, J. (2016). Parent academy evaluation report and executive summary. London: Education Endowment Foundation.

Janesick, V. (2000). “The choreography of qualitative research design: minuets, improvisations and crystallization,” in Handbook of qualitative research, eds N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 379–399.

Jasso, J. (2007). African American and non-Hispanic White parental involvement in the education of elementary school-aged children. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University.

Jeynes, W. H. (2007). The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Urban Educ. 42, 82–110. doi: 10.1177/004208590629381

Jeynes, W. H. (2012). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of different types of parental involvement programs for urban students. Urban Educ. 47, 706–742. doi: 10.1177/0042085912445643

Jeynes, W. H. (2022). Relational aspects of parental involvement to support educational outcomes: parental communication, expectations, and participation for student success. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lehrl, S., Evangelou, M., and Sammons, P. (2020). The home learning environment and its role in shaping children’s educational development. Schl Effect. Schl Improv. 31, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2020.1693487

Marti, M., Merz, E. C., Repka, K. R., Landers, C., Noble, K. G., and Duch, H. (2018). Parent involvement in the getting ready for school intervention is associated with changes in school readiness skills. Front. Psychol. 9:759. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00759

Melhuish, E., Quinn, L., Sylva, K., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., Taggart, B., et al. (2001). Cognitive and social/behavioural development at 3-4 years in relation to family background. Belfast: The Stranmillis Press.

Moss, P., Petrie, P., and Poland, G. (1999). Rethinking school: some international perspectives. Leicester: National Youth Agency for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Munroe, G., and Evangelou, M. (2012). From hard to reach to how to reach: a systematic review of the literature on hard-to-reach families. Res. Papers Educ. 27, 209–239. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2010.509515

Office for National Statistics (2021). Census: digitised Boundary Data (England and Wales). Available online at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/ (accessed June 2, 2022).

OFSTED (2012). The framework for school inspection: guidance and grade descriptors for inspecting schools in England under section 5 of the Education Act 2005, from January 2012. London: OFSTED.

Okpala, C., Okpala, A., and Smith, F. (2001). Parental involvement, instructional expenditures, family socioeconomic attributes, and student achievement. J. Educ. Res. 95, 110–115. doi: 10.1080/00220670109596579

Payne, R. (2006). Working with parents: building relationships for student success, 2nd Edn. Highlands, TX: Aha Process.

Peters, M., Seeds, K., Goldstein, A., and Coleman, N. (2007). Parental involvement in children’s education. London: Department for Children, Schools and Families.

Plowden, B. (1967). Children and their primary school. report of the central advisory council for education (England). London: HMSO.

Price-Mitchell, M. (2009). Boundary dynamics: implications for building parent-school partnerships. Schl Commun. J. 19, 9–26.

Pushor, D. (2015). “Walking alongside: a pedagogy of working with parents and families in Canada,” in International teacher education: promising pedagogies (Part B), eds L. Orland-Barak and C. Craig (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 233–251. doi: 10.1108/S1479-368720150000025008

Pushor, D., and Amendt, T. (2018). Leading an examination of beliefs and assumptions about parents. Schl Leadersh. Manag. 38, 202–221. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2018.1439466

Sacker, A., Schoon, I., and Bartley, M. (2002). Social inequality in educational achievement and psychosocial adjustment throughout childhood: magnitude and mechanisms. Soc. Sci. Med. 55, 63–880. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00228-3

See, B. H., Gorard, S., El-Soufi, N., Lu, B., Siddiqui, N., and Dong, L. (2021). A systematic review of the impact of technology-mediated parental engagement on student outcomes. Educ. Res. Eval. 26, 150–181. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2021.1924791

Smith, J., and Wohlsetter, P. (2009). Parent involvement in urban charter schools: a new paradigm or the status quo. Nashville: Vanderbilt University.

Spear, S., Spotswood, F., Goodall, J., and Warren, S. (2022). Reimagining parental engagement in special schools – a practice theoretical approach. Educ. Rev. 74, 1243–1263. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2021.1874307

Sturman, L., and Taggart, G. (2008). The professional voice: comparing questionnaire and telephone methods in a national survey of teachers’ perceptions. Br. Educ. Res. J. 34, 117–134. doi: 10.1080/01411920701492159

Sylva, K., Siraj-Blatchford, I., and Taggart, B. (2003). Assessing quality in the early years: early childhood environment rating scale. Trentham: Stoke on Trent.

Theodorou, E. (2008). Just how involved is ‘Involved’? Re-thinking parental involvement through exploring teachers’ perceptions of immigrant families’ school involvement in cyprus. Ethnogr. Educ. 3, 253–269. doi: 10.1080/17457820802305493

UK Government (2018). Improving the home learning environment: a behaviour change approach. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/919363/Improving_the_home_learning_environment.pdf (accessed June 2, 2022).

Weiss, H., Mayer, E., Kreider, H., Vaughan, M., Dearing, E., Hencke, R., et al. (2003). Making it work: low income working mothers’ involvement in their children’s education. Am. Educ. Res. J. 40, 879–901. doi: 10.3102/00028312040004879

Wilder, S. (2014). Effects of parental involvement on academic achievement: a meta-synthesis. Educ. Rev. 66, 377–397. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2013.780009

Williams, B., Williams, J., and Ullman, A. (2002). Parental involvement in education. Research report 332. Available online at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/4669/1/RR332.pdf (accessed June 2, 2022).

Wilson, S., and McGuire, K. (2021). They’d already made their minds up’: understanding the impact of stigma on parental engagement. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 42, 775–791. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2021.1908115

Keywords: parental engagement, parental involvement, teacher attitudes, school leaders, policy

Citation: Jones C and Palikara O (2023) How do parents and school staff conceptualize parental engagement? A primary school case study. Front. Educ. 8:990204. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.990204

Received: 09 July 2022; Accepted: 20 June 2023;

Published: 06 July 2023.

Edited by:

Matteo Angelo Fabris, University of Turin, ItalyReviewed by:

Caroline Walker-Gleaves, Newcastle University, United KingdomNelly Lagos San Martín, University of the Bío-Bío, Chile

Kristina Astrid Hesbol, University of Denver, United States

Copyright © 2023 Jones and Palikara. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cat Jones, Yy5qb25lcy4yN0B3YXJ3aWNrLmFjLnVr

Cat Jones

Cat Jones Olympia Palikara

Olympia Palikara