94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 09 February 2023

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.967279

This article is part of the Research TopicInclusion and Diversity in EducationView all 9 articles

Individual and social explanatory models provide different frameworks for teachers’ practice. This study addresses how teachers’ understanding of inclusion and challenging behaviors affects their work with an inclusive practice in school. The chosen research design can be characterized as a qualitatively driven mixed-method case design, and the data collection was based on an explorative sequential design. All teachers from two schools that both have a vision linked to being inclusive were invited to participate, and the first five teachers who signed up from each school were included in this study. The data are based on interviews with and observations of 10 teachers as well as a survey conducted at 16 schools in Western Norway distributed across eight different municipalities. Based on an inductive analysis, the findings show that physical participation in the classroom is central to teachers’ understanding of inclusion. At the same time, they emphasize the importance of social and academic mastery. The study, nevertheless, shows that classroom participation and coping can conflict with each other. This means that teachers must often balance different considerations related to both practical and ethical dilemmas. When they encounter challenging behavior, they are additionally forced to make assessments in stressful situations. It is also in these situations that the underlying and often unconscious explanatory models provide the greatest guidance for the teachers’ decisions. Nevertheless, decision-making in stressful situations seems to be an almost absent topic in both teacher training and the professional community in schools. The authors of this article, therefore, argue that decision-making in stressful situations seems to be underestimated in the work on developing inclusive practices.

In recent decades, inclusion has received great commitment in school systems around the world. Despite the broad support, as well as comprehensive guidelines from the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (General Comment No. 4), there is no unanimous agreement on what inclusion entails or what an inclusive practice looks like (Allan, 2008; Kiuppis, 2011; Haug, 2017). Florian (2014) argued that inclusion must be understood contextually and that an inclusive practice can have many different forms. The background for such an argument is that inclusive practices must be developed in unique schools and classrooms, which, in turn, are influenced by various framework factors and educational policy guidelines. The development of an inclusive practice must also be balanced in relation to several different tensions. Such tensions will, for example, be about creating room for individuality versus being able to adapt to a group. Furthermore, the tensions can be about adapted teaching, where the students work with individual tasks versus finding universal tasks that all students can master simultaneously. As a teacher, one must consider short-term mastery versus long-term mastery and academic development versus social development. Van Manen (1991) reminds us to always ask the child about their experience, which then brings us to the fact that inclusion also has a subjective dimension (Qvortrup, 2012). Such a starting point will naturally mean that what is perceived as an inclusive practice for one student cannot necessarily be considered inclusive for another student. Moreover, students are constantly evolving, and an inclusive practice must, therefore, be adapted to their age and level of development. When dealing with great diversity, an inclusive practice will look different for the youngest grade levels than for the oldest ones. The development of an inclusive practice requires one to address these dilemmas, and the responsibility for inclusion is thus largely left to the respective schools and teachers (Takala et al., 2012). Many of these dilemmas come to the fore when dealing with challenging behavior, and, hence, the development of an inclusive practice that takes into account challenging behavior is perceived as one of the most demanding challenges in a teacher’s everyday life (Avramidis and Norwich, 2002; De Boer et al., 2010; Buttner et al., 2015; Willmann and Seeliger, 2017). Being a teacher means being able to balance different expectations that are sometimes difficult to reconcile. Calderhead (1981) claimed that a teacher makes up to 200 decisions during a 45-min teaching session, and many of these decisions will indirectly or directly have a great impact on inclusive practice. Borko et al. (1990) underlined how decisions affect practice, and Blackley et al. (2021) stated that “the process and outcome of decisions made in a classroom are important, considering teachers are estimated to make a new decision every 15 seconds (p. 548). This means that an inclusive practice must be based on the teacher’s professional judgment. Therefore, it is also natural that teachers’ understanding of the concept of inclusion is a critical factor in developing an inclusive practice (Norwich, 1994). Several studies have shown how teachers’ beliefs are important for the work with inclusive practices (Avramidis and Norwich, 2002; Hodge et al., 2004; Grieve, 2009; Dignath et al., 2022; Woodcock and Nicoll, 2022). Teachers’ beliefs have “an adaptive function in helping individuals define and understand the world and themselves” (Pajares, 1992, p. 325). Based on a literature review, Fives and Buehl (2012) define teachers’ belief systems as a set of dynamic and integrated beliefs in connection with various themes, where belief systems function as “(a) filters for interpretation, (b) frames for defining problems and (c) guides or standards for action” (p. 478). Jørgensen and Phillips (2002) argued that our knowledge of the world should not be treated as objective truths. Our knowledge and representations of the world are not reflections of the reality “out there” but, rather, products of our understanding of various phenomena and concepts. Argyris and Schön (1974) talk about “beliefs” using the term “theories of actions” (p. 3). “Theories of actions” can be described as a personal theory that seeks to explain and solve a given situation or challenge. Such a theory can thus be described as an explanatory model based on our beliefs and perceptions of reality. An explanatory model (Argyris and Schön, 1974, 1978) enables some forms of action to become natural, while others become unnatural. This brings with it some pedagogical implications, as our understanding of reality provides guidelines for practice (Kos et al., 2006; Barker and Mills, 2018). When challenging behavior must be understood and handled within an inclusive framework, it is not the teacher’s understanding of the concept of inclusion alone that provides guidelines for pedagogical practice. Therefore, the research question in this article is as follows:

How can different explanatory models relating to inclusion and challenging behaviour affect teachers’ work with an inclusive practice in school?

Inclusion and inclusive practices can be understood and studied at both the micro and macro levels. In addition, the connection between these levels is crucial (Haug, 2017) for the development of inclusive communities. However, in this study, we have chosen to limit inclusive practice to occurrences in the classroom and at the individual school level. The authors relied on inclusive pedagogy from Florian and Black-Hawkins (2011) and their framework for participation. Here, participation is linked to access, collaboration, achievement and diversity.

Challenging behavior is difficult to define, and this makes the phenomenon complex in both the ontological and the epistemological sense (Øen and Krumsvik, 2021). Although it is possible to reach a certain consensus that some types of behavior are more challenging than others, the context in which said behavior occurs will, nevertheless, be of great importance for our assessment. For example, some may argue that saying “hell” is an example of unacceptable language that should not be used in school. However, if it is said in connection with a student reading aloud from the Bible, uttering the word “hell” will be unproblematic and natural. The same applies to punches and kicks, which can, of course, be examples of challenging behavior. However, if punches and kicks occur as a part of a play that includes an adaptation of force, these actions can be considered innocent. Therefore, context is essential when the appropriateness of specific behaviors is being assessed. Purely objective criteria for assessing whether a behavior is challenging have clear limitations. Another ambiguity when discussing challenging behavior is associated with who or what the behavior is a challenge for. We can say that the behavior creates problems for the other students (Razer and Friedman, 2013) or that it creates problems for the teacher (Avramidis and Norwich, 2002; De Boer et al., 2010; Buttner et al., 2015). Sometimes, it is mentioned that the behavior creates problems for the learning environment and for the flow of teaching (Orsati and Causton-Theoharis, 2013; Hind et al., 2019). Finally, one can also talk about challenging behavior as a problem for the students who perform the behavior themselves (Gidlund, 2018).

If one accepts that some types of behavior are challenging or problematic, new questions arise regarding how one can understand the occurrence of such behavior and where the “responsibility” for such behavior is placed. To answer these questions, and for the sake of simplicity, one can make a rough distinction between individual models and social models (Reindal, 2009). Within individual and social models, there are different approaches, and some will be more extreme than others. Therefore, a continuum can be imagined with several intermediate positions, where the most radical individual and social models represent the extremes on each side. The individual models are often based on essentialism, where the challenging behavior is linked to the personality traits or characteristics of the person performing the behavior. In its radical version, essentialism will take a reductionist form, in which an individual in a biomedical discourse, for instance, has an understanding that all behaviors can be explained on the basis of biological mechanisms (Burr, 2015). With regard to challenging behavior, this thinking will, among other things, highlight extensive research on individual risk factors. Typical examples of such individual risk factors may be restlessness, poor impulse control, weak self-regulation, difficulty controlling temperament and executive dysfunction (Thomas et al., 1968; Moffitt, 1993; Barkley, 2012). Such individual risk factors also constitute some of the core symptoms for certain medical diagnoses, and challenging behavior is often linked to diagnoses such as ADHD and Tourette’s and Asperger’s syndrome (Kristjansson, 2009). Erlandsson and Punzi (2017) claimed that there is a growing tendency to perceive and explain human characteristics, emotions and behavior as expressions of neurobiological functions and dysfunctions. Thus, when challenging behaviors occur, a child becomes both the cause and the problem within such biomedical discourse and must, therefore, be examined and treated. Barker and Mills (2018) suggested that this thinking has made its way into the education system and that teachers play a central role in the medicalisation and psychologisation of children and childhood. Teachers are often the first to suggest diagnoses such as ADHD when a student shows challenging behavior in the classroom (te Meerman et al., 2017), and, hence, they function as an extension of the medical profession (Erlandsson and Punzi, 2017). Berg (2013) referred precisely to how this thinking can be expressed and what consequences this can have for the understanding of inclusive practice:

At last, we succeeded in figuring out Roar. He has been given an ADHD diagnosis. It was really a huge relief for me … my responsibility as teacher is finally clarified, so to speak. The diagnosis confirms Roar’s special problems. It’s not me that is wrong or bad or something. I always knew that, of course, but you start putting yourself down when you fail to manage class, and things get worse and you’re feeling bad. Now Roar has been given his medicine, and consequently, I can expect him to behave properly and to adjust to the behavioural norms. From now on … I mean … things are going to be normal again. If not, he’ll be moved to “the group for the badly behaved ones”. (p. 274)

In this quote, the teacher presents the entire “explanation” of ADHD and considers neither themself nor other contextual factors as a part of the “picture”. In this way, challenges such as lack of adjustment in school, poverty, drug abuse and domestic violence can be turned into individualized problems in the child, leading to the notion that these children lack what it takes to participate in class (Øen and Krumsvik, 2021).

On the other side of the continuum, we find social models. These are based on a social constructivist approach and can be understood as a critique of individual models (Burr, 2015). Social constructivism is often critical of “taken for granted” knowledge. While individual models rely on empirical evidence showing, for instance, that ADHD increases the risk of developing challenging behaviors (Banaschewski et al., 2003), social models will ask critical questions about the existence of such types of diagnosis. There are several diagnoses related to “challenging behavior” that were previously taken for granted, but which remain as gross repression in today’s context. An example of this is drapetomania, a “mental illness” that was used as an explanation for why some slaves seemed to have an “urge” to escape from the plantation (Jutel, 2009). While individual models in a school context rely on the question “What is wrong with this child?,” social models will focus on the context and ask, “What is wrong with the learning environment that causes some children to struggle?.” Social models can be more or less radical, and, based on relativism, they argue that nothing exists outside the socially constructed world (Burr, 2015). Therefore, there are no deviations from the normal, only natural variations within human diversity (Reindal, 2009). Based on this argument, special education can be understood as an artificially created phenomenon that arises from barriers in the education system. Instead of accepting that such barriers exist, a relativist will claim that a misconception has been developed which suggests that some children deviate to such an extent that something very special is required to meet their educational needs. Segregated special-needs education is thus ethically problematic and exclusive because some children are deprived of the opportunity to take part in community, academic and social activities due to system weaknesses. Based on such thinking, it can be argued that the extent of special-needs education becomes an indicator of inclusive practice, where schools with little to no special-needs education can be considered more inclusive than those with a substantial level of the same. Although such an argument may appear both logical and alluring, such relativism can also be criticized for denying and obscuring the existence of “real difficulties” (Cigman, 2007; Hornby, 2015). The recognition that there are children with real special-education needs and an increased understanding of their challenges can contribute to the reduction of challenging behaviors by establishing a better environment (Montoya et al., 2011; Ferrin et al., 2016; Dahl et al., 2019).

As stated, social constructivism exists in various forms and can also recognize that there are individual variations in personalities that can increase the risk of, for example, challenging behaviors (Atkinson, 1995; Burr, 2015). Different explanatory models within both individual and social models should, therefore, be understood as a continuum in which there are several intermediate positions. Such a position can be found, for instance, through the bio-ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner and Ceci, 1994), where one understands human behavior as a product of both biology and the environment. From this perspective, challenging behaviors can be understood as the “failure to match” that occurs when there is a mismatch between individuals’ competences and the demands and expectations of their environment (Nordahl et al., 2005). Here, it is assumed that people have different prerequisites, but it also allows for all people to have the potential to reach “the breaking point” when exposed to a sufficient degree of “unreasonable” demands and expectations.

Another important question is whether challenging behaviors are the result of characteristics or of conscious choices and free will. The question can also be linked to individual and social models and, thus, understood as a part of the same continuum. An approach in which one emphasizes free will and that a child chooses their own behavior can be linked to relativism, where one denies that real difficulties, such as executive dysfunction, can be used as an “explanation” for the child’s behavior. With such a starting point, there is no good ethical argument for adapting to the child’s needs (Reindal and Hausstätter, 2010). From this perspective, if a child in the classroom behaves in a way that is problematic for themself or others, they are fully responsible for their own actions. Such a radical approach would be problematic, as the Salamanca Declaration (UNESCO, 1994) – considered by many to be the starting point for inclusive pedagogy – emphasizes that inclusion is about taking into account that children and young people come to school with different prerequisites and encourages the creation of a space for all within the community.

At the other end of the continuum, a one-sided emphasis on characteristics and lack of skills is closely linked to the biomedical discourse. This facilitates individual adaptation and, at the same time, provides guidelines for how one can understand a student’s self-determination. For example, a focus on the lack of self-regulation and executive difficulties can lead to a perception that a child lacks what it takes to make good choices in many situations (Barkley, 2012). Such a child becomes more of a victim of their external environment and, thus, needs someone to “take control” on their behalf. Within the biomedical discourse, the student’s self-determination risks being subordinated, as they do not have the prerequisites to choose their own best interests. This, in turn, leads to a paternalizing pedagogical practice where the child is primarily given the position of an object. The risk of inhumanity is also greater when the perception of the child is rooted in objectivism (Ekeland, 2014).

Biesta (2016) linked pedagogical practice to Aristotle’s distinction between poiesis and praxis. When pedagogical practice is linked to poiesis, children become an object of creation. Thus, pedagogy based on poiesis becomes technical and recipe-based. If pedagogy is based on praxis, it is the attitudes behind the actions that become the crux, and ethics come to the center. Therefore, pedagogical practice must always be perceived as praxis to prevent an instrumentalist touch (Skjervheim, 1992). Carr and Kemmis (1986) also relied on Aristotle and distinguished practice as more or less automated actions, while praxis was considered a conscious action where the focus is on the practitioner’s desire to act wisely. Calderhead (1981) indicated that many teachers’ actions often show signs of being automated, and this especially occurs in situations where they experience anxiety or fear (Senge et al., 2005). The learning potential is great in such critical situations (Lewin, 1951), but this potential is often not utilized. The problem is that, in critical situations, individuals tend to maintain their established patterns of interpretation, and this prevents them from considering new perspectives. New perspectives can actually be threatening, and people often end up looking for interpretations of situations that coincide with the beliefs and explanatory models they trust. Therefore, Tiller (1999) claimed that when a teacher is confronted with their standard repertoire, they often find that their pedagogical practice does not reflect the intentions, values and attitudes that they want to express. An important prerequisite for this article is the acknowledgement that the gap between “life and learning,” or theory and practice, can never be closed completely in a pedagogical situation. The complexity in the field of practice is too great and will always have several dilemmas that teachers must deal with promptly. Nevertheless, Weniger (1975) precisely discussed the “true and real” practice in which one works to minimize the gap between theory and practice. It is not a matter of searching for the “right” practice in the universal sense but of removing logical shortcomings between the theoretical and ethical bases that one relies on and their pedagogical practice. Inclusion regarding challenging behavior can be understood as a search for a pedagogical practice where wise decisions and ethics are central. Such a quest requires what Aristotle described as phronesis: a moral virtue with a tendency to act wisely, truthfully and justly (Aristoteles, 2011). With such a starting point, an inclusive practice will mean that the teacher takes with them principles and values related to inclusion and applies these wisely when dealing with their class and individual students.

To search for good and applicable theories related to the concept of inclusion, Nilholm (2020) argued that case studies appear to be a suitable approach. Case studies make it possible to consider the complexity of studied phenomena while preserving their integrity (wholeness). Nilholm (2020) also stated that case studies related to the field of inclusion should be based on rich data and combine both qualitative and quantitative methods. In the literature, case studies are referred to as both a method and a methodology. Stake (2005) claimed that case studies are not about methodology but about what is to be studied. However, this article considers case studies to be a methodological approach and relies on Creswell and Poth’s (2018) definition of case studies: “a qualitative approach in which the investigator explores a real-life, contemporary bounded system (a case) or multiple bounded systems (cases) over time, through detailed, in-depth data collections involving multiple sources of information” (p. 96–97).

Fetters et al. (2013) positioned case studies in what he calls an “advanced framework” mixed-method design, which requires an intensive and often cumulative qualitative and quantitative data collection over time. The qualitative and quantitative data to be collected depend on the nature of the case. The qualitative and quantitative elements within mixed methods may have equal or different dominance. In this study, which is a qualitatively driven mixed-method study, it is the qualitative method that serves as the core (Hesse-Biber and Johnson, 2015).

This study is based on an explorative sequential design (Schoonenboom and Johnson, 2017) in which a literature review (Øen and Krumsvik, 2021) and the schools’ vision formed the basis for the first phase: the interview guide. The study has an inductive approach and, therefore, semi-structured interviews were planned. The interview guide was mainly characterized by open questions as support for elucidating the teachers’ understanding of inclusion and challenging behavior. Some examples of the questions are presented below:

• How do you understand the term “challenging behaviour”? What do you mean by this, and do you have examples from your everyday life?

• When situations with challenging behaviour arise, what thoughts do you have in relation to “why” the student shows such behaviour or the “reason” for the behaviour?

• What do you mean by the term “inclusive practice”?

• What opportunities, challenges, dilemmas and barriers do you see in relation to working towards an inclusive practice in your own workplace?

Based on an analysis of the interviews, an observation guide inspired by the work of Merriam and Tisdell (2016) was developed, where one seeks rich descriptions. Hence, the observation guide mainly consisted of bullet points that should help the observer narrow their observations. Examples of such bullet points are presented below:

• How does the teacher relate to individual agreements/adjustments?

• Which forms of teaching seem to dominate?

• Where do the interactions with the students take place?

• What behaviour seems to challenge the teacher?

• How does the teacher respond emotionally to challenging behaviour?

• How does the teacher speak to the student?

• How are situations resolved when challenging behaviour occurs?

The interviews and observations then formed the foundation for a qualitative analysis (interview and observations), which, in turn, underpinned the items of the survey. Such a quantitative follow-up is useful to strengthen the validity of qualitative findings for a wider population and to “test out the theoretical ideas generated from the qualitative study” (Hesse-Biber and Johnson, 2015, p. 8). It also provides an opportunity to further explore the findings obtained from the qualitative analysis.

A characteristic of mixed-methods studies is that they have at least one “point of integration” where the qualitative and quantitative components are brought together (Schoonenboom and Johnson, 2017). Although Figure 1 gives the impression of a sequential linear process, the design lends itself to an iterative process where the various sequences are based on analysis from previous sequences. At the same time, subsequent sequences shed light on the initial analysis, and, in this way, the “point of integration” in such a design starts with the research question itself.

When choosing a case, it is not uncommon to think that it should be representative. Such ambition can, however, be problematic, as one or a few cases cannot represent others in a way that can help make statistical generalizations. Stake (1995) argued that the most important criterion when choosing a case is to think about what one can learn the most from. In this study, there are two cases in the form of two schools. Both schools have clear visions related to inclusion and, therefore, work systematically toward an inclusive practice. The principals of the two schools, after discussions with other management and the school’s teachers, were positive about participating in the project. The researchers were given access to the school’s meeting time and informed the teachers themselves about the project. All teachers were also given written information about the project. The teachers who wanted to participate were encouraged to make direct contact with the researchers, and the criterion for participation was that the teachers themselves had had a subjective experience of having challenging behavior in their classroom. The first five teachers who signed up from each school participated and gave written consent to participate. Thus, a total of 10 teachers were taken as subunits of analysis, and the design can be described as an embedded case design (Yin, 2014). Of the 10 teachers who participated, eight were women, while two were men. To maintain anonymity, we have chosen to use “she” when referring to the teachers.

With regard to the survey, an invitation to participate was sent to 26 schools in Western Norway distributed across eight municipalities. The invitations were based on a stratification in which both primary and secondary schools, as well as schools of different sizes, were to be represented. The researchers received a positive response from 16 principals and provided direct information to the teachers through physical presence at the school. It was clearly emphasized that participation in the survey was voluntary regardless of the headmasters’ request for the same. A total of 293 teachers participated in the survey (N = 293), and the survey had a response rate of 67%, which is acceptable considering that many schools had abnormally high sickness absences among teachers due to COVID-19 in the spring of 2022. In the survey, 75.86% of the respondents were women, while 24.14% were men, and the respondents were distributed relatively evenly across the 10 grade levels of the Norwegian primary and lower secondary school system (Table 1).

The project was assessed and approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) in October 2020. We then executed an excessive cumulative data collection process and analysis in our case study from November 2020 to June 2022; this long period allowed us to test our interpretations along the way and detect contrary evidence. As this is a qualitatively driven mixed-method study, the primary data material in this article is based on interviews with the 10 teachers as well as observations of the same teachers during classroom situations and collaborations with colleagues in the professional community. The teachers were interviewed individually in the autumn of 2020 and in the winter of 2021, and the interviews lasted for an average of 55 min. When all the interviews were completed, open coding was performed (Corbin and Strauss, 2008) using NVivo, the analysis tool.

A total of 73 teaching sessions of varying lengths were observed, adding up to 70.5 h (4,920 min). The observations were carried out from January 2021 to June 2021. After each observation, an informal observation interview was also conducted with the teacher to determine whether they were available for such a conversation. Sometimes, this was impossible, as the teacher had to run to other classes or became busy following up on a situation that had arisen during the class. Such informal conversations allowed teachers to provide a quick assessment of how they experienced the lesson in addition to justifying the choices they made. It also allowed for researchers to ask clarifying questions. When you both interview and observe teachers, it can reveal gaps between what the teacher says they do and what they actually do (Krumsvik, 2014). When there is a gap between the expressed or desired practice and what happens in the classroom, Irgens (2007) describes this as an integrity gap. By combining interviews with subsequent follow-up observations, the researchers risked uncovering both large and small integrity gaps. This meant that they had to deal with certain ethical considerations. Although the purpose of this study was not to identify an integrity gap, it was a challenge, since research should always safeguard human dignity and personal integrity. To safeguard the teachers’ integrity, it was particularly important to provide them with thorough information about the study. In addition, the informal conversations after the lesson were very important so that the teachers themselves had the opportunity to justify the choices they made during the lesson as well as elaborate on the dilemmas they experienced along the way.

Furthermore, 13 h (780 min) of the observations carried out consisted of the teachers collaborating with colleagues, management and the schools’ external supporters (educational and psychological counseling service, child welfare service, municipal guidance service, etc.). All the observations were made by the researcher as a participating observer (Gold, 1958). Immediately after the observation, the researcher withdrew to write the observation notes. All field notes were written supplementarily before a new observation was carried out. Using this method, one can seek to keep the various observations as far apart as possible (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016).

Once again, the qualitative analysis formed the basis of a survey that was conducted at 16 schools in Western Norway in the spring of 2022. The survey was conducted digitally using Survey Monkey. The data collection was set up so that the teachers had been allocated time to answer the survey immediately after the researcher had visited the school and informed them about the study.

Given the research question, it was considered most appropriate to conduct an inductive thematic analysis of the qualitative data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Braun et al. (2018) claim that “thematic analysis” should be understood as an umbrella term that includes different approaches through which one seeks to identify patterns or themes in qualitative datasets. The inductive approach employed allowed for a richer and freer description of the data material; it was not governed by existing theory in the field and can, therefore, be characterized as data-driven (Patton, 2015). Although the interviews were previously analyzed to serve as a basis for the observation guide, all the interviews were re-analyzed in combination with the observations. Open coding was performed (Corbin and Strauss, 2008) using NVivo. The codes were then grouped, and themes were developed through an iterative process. For the analytical process to be as transparent as possible, Table 2 shows an example of how the coding was carried out, from the various quotes to the overall theme.

Through the analysis, four main themes were developed. These are inclusion as mastery and participation in a strong collective, mindset to challenge, responsibility in the situations and in the heat of the moment. Utilizing an exploratory sequential design, the researcher first collected and analyzed the qualitative data. The findings then informed the quantitative data collection and analysis so that the integrations took place through what Fetters et al. (2013) refers to as building. The four themes from the qualitative analysis, therefore, formed the basis of the quantitative analysis, while the quantitative analysis contributed to underpinning, expanding and nuancing the qualitative analysis. Thus, we have chosen to present the findings from the two analyzes using a weaving approach, which involves writing both qualitative and quantitative findings together on a theme-by-theme basis. Furthermore, we applied narratives whereby the qualitative and quantitative results are reported in the same article (Fetters et al., 2013).

The main quantitative measures encompassed two latent composite variables: (1) segregation and (2) negative experiences. Segregation [M = 3.36, SD = 0.63, α = 0.77, 95% CI (0.73, 0.81), n = 231] was computed based on 11 observed variables (e.g., an inclusive school is positive for all pupils), measured on a Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Further, negative experiences [M = 1.79, SD = 0.62, α = 0.83, 95% CI (0.79, 0.85), n = 288] were computed based on seven observed variables (e.g., how often did the teachers feel afraid due to challenging behavior), measured on the following scale: 0 (never), 1 (less than once a month), 2 (monthly), 3 (weekly) and 4 (daily). The data were screened and analyzed using R (R Core Team, 2022).

The teachers in the qualitative part of the study experienced that they work in a class/group with an average or slightly above average degree of challenging behavior. When teachers were asked to describe what they categorize under the term “challenging behavior,” everyone mentioned what typically falls under “externalizing behavior.” This can range from disrupting behavior and swearing to more serious forms of externalizing behavior such as violence and bullying. However, all teachers said that externalizing behavior is by no means the only form of challenging behavior. One of the teachers said, “There is a lot that can be challenging behavior, such as to not wanting to work. It’s quite challenging when I have students who refuse to work or who refuse to talk.”

Not getting the student to participate actively or not getting proper contact with the student is highlighted by many as demanding. One teacher described self-harming behavior as very challenging for the teacher as well as the student. The teachers’ different emphases show that the understanding of challenging behavior is subjective. One of the teachers stated the following:

I sometimes think it's easier to deal with those who have a behaviour that you have read about in the textbooks. There, you read that some students jump out the window, and some hang in the curtains. Ok, you’re prepared for that. But then, there are those who are a little more subtle.

She then followed up by saying that what really makes her “boil” are the “good girls” who try to twist her around their little finger and get “benefits” that the other students do not have. However, she did not believe that this type of behavior bothered the other teachers with whom she collaborated. Therefore, in the introduction to the survey, it is emphasized that it is the teachers’ own subjective assessment that shall be used as a foundation when they are asked to assess the extent of challenging behavior in their own practice. From Table 3, we can see that 24.74% of the respondents in the survey believed that the school they work at has a large to very large scale of challenging behaviour, while the corresponding figure for the grade level they handle is 34.02%.

In the following sections, the four main themes will be presented and elaborated.

When the teachers in the interviews were asked about their understanding of the concept of inclusion, everyone emphasized that physical participation in the class or group constitutes its essence. Nevertheless, it was clear through both the interviews and the observations that some students receive all or a part of their education out of the classroom by way of one-on-one time with the teacher or in small groups. The teachers experience this as a big dilemma, as they also emphasized that inclusion is about mastery. In the survey, 73.97% of teachers “somewhat agree” or “strongly agree” that mastering academics is a prerequisite for students to feel like a part of the community. Furthermore, 90.72% “somewhat agree” or “strongly agree” that mastering social interaction is a prerequisite for feeling like a part of the school community. When “mastery” becomes a central part of the work associated with inclusive practice, some of the teachers stated in the interviews that certain students do not have the capacity for full physical participation. It is not the consideration of the other students that is emphasized here but what is good for the students themselves. In some situations, certain students need to be in a smaller environment than in a large classroom. One of the teachers problematises this, saying, “I know it’s like swearing in church to say that we do not think everyone should be included all the time, but I actually mean that some students do not cope with full inclusion all the time.”

When the school’s ambition is to promote health and contribute to well-being as well as professional and social development, our findings indicate that teachers often experience being caught between competing values. Several teachers also stressed that inclusion is also about creating a strong collective and that this requires everyone to pay attention to each other. One of the teachers stated the following:

I do not think it’s a right to be in the classroom no matter what. Because if you are going to be in a community, then you must respect the rules of the community. If, for various reasons, you are unable to comply with these rules, then you are allowed to take a break. It is perfectly legal, and it is quite common that we need breaks from time to time. But the fact that everyone should always be in the same room, all the time and at all costs, it destroys the learning community, and it is not fair.

This indicates an approach to inclusion wherein belonging to an inclusive community is not exclusively a right, as there is also an expectation and a requirement for the individual student with regard to contributing to an inclusive community. Similar statements appeared several times during the observations, where the teacher typically told students, “If you are going to be in here, you have to follow the rules.” Teachers are concerned that students must be made responsible for their own behavior in an inclusive community. One of the teachers stated, “Inclusive community is about respecting each other, for the rules we have, and that we should care about each other.”

Such thinking also implies that the school and the teachers show respect and care for the students even though the students exhibit challenging behavior. This became clear at a meeting between the school and one of the external supporters, where some students had resorted to vandalism in their spare time and had been taken by the police. Although the school felt that the students had to be responsible for their actions, they reiterated the importance of the students still feeling welcome at the school. They acknowledged that the situations were frustrating and demanding for the students and had several conversations with them, during which the students were allowed to share their anger and frustration. The school highlighted that this was especially important when the students were feeling as though everyone else had turned their backs on them. Such an approach can be interpreted along the lines of an understanding of inclusion where students, regardless of their actions, belong to and are always welcome at school. This understanding of inclusion is comparable to the unreserved love parents often give to their children.

Differing emphases on “mastery” and “the strong collective” mean that two distinctive approaches to inclusive practice crystallized in the data. The strong focus on mastery meant that several of the teachers placed value on individual adaptation to a great extent. This was expressed through individual plans, individual work assignments, teaching through workstations, tailor-made social stories and so on. Above all, this was expressed through the teachers’ preparatory work before each lesson. During one of the informal conversations after an observation, the researcher told one of the teachers that they had noticed how much preparation she was doing. She said that being observed had also led to opening her eyes to how much work she had put into this. She said, “I have worked as a teacher for 17 years, and I work more now than when I started.” She further said that all those small preparations helped her avoid critical transitions and situations and that that was the very key to success with students who could be challenging with their behavior at times. Moreover, as adapted teaching was seen as a necessity by several teachers, some reflected on how much individualisation was possible to carry out before it went beyond the feeling of being a part of a group. One teacher stated the following:

We must accept the students’ differences; but at the same time, we must find the limit for when the feeling of participation ceases. That’s what challenges me, where the end point for adapted teaching should be … so that we do not end up having 25 individual goals in one hour.

Another teacher said that she had so many students in the class with special arrangements and special agreements that it had become difficult for the staff to keep track. Although all the teachers in the interviews were concerned with physical participation, the recognition of mastery meant that inclusive practice was not assessed based on physical presence alone. In the survey, 85.56% answered that they somewhat or completely agreed that an inclusive school is positive for all students. Nevertheless, only 10% of the teachers completely agreed with the statement “In an inclusive school, there are no students who are taken out of the community.” Overall, 91.69% believe that there should be greater opportunities for some students to be “out of school” one to two days a week to do practical work. This can be interpreted in different ways; but considering the qualitative data, this is primarily understood as an expression of the fact that many teachers experience the school’s framework as being too limited when faced with the large diversity of students. When the teachers in the interviews reported that an inclusive practice must also allow for segregated teaching, they stressed that deviations from the principle of full participation must not occur at the expense of the students not feeling like a part of a larger community.

At the other end of the scale are teachers who highlighted to a greater extent that inclusion is about building a “strong collective.” One of the teachers expressed scepticism about too much adapted teaching and said that she was afraid that a culture would develop where the students thought that “if I am just difficult enough, I will also be allowed to do more fun things.” The teachers who prioritized the strong collective worked hard for the students to feel like they belonged together and were a class. In one of the observed lessons, the teacher started by telling the students to draw a circle on a sheet of paper. On the outside of this circle, they were to draw two new circles so that there was a total of three circles. The teacher further said that the students should write “me” in the innermost circle. They were asked to write the name of the student they were sitting next to in the next circle and write “The Class” in the outer circle. The students were then asked to write down what they knew about a topic in the inner circle. They would then discuss and share the same with their peer and write down what they learned from each other. Finally, all the students walked around the classroom and shared what they had written with their other classmates. The teacher stated several times along the way that “everyone participates on their own terms and brings what they have to the class community. There is no competition because it is what we can do together that counts.” There was a high level of student activity, and the students seemed engaged. At the end of the lesson, the class made a mind map together on the board, and the teacher ended by saying, “See what we as a class can do.” Several lessons were observed in which joint activities were emphasized, and many of these lessons seemed to engage most of the students. At the same time, it often led to some students disconnecting completely from the teaching. Sometimes, this resulted in disruptive behavior, while the disconnection from teaching took a passive form at other times. In one of the lessons observed, it was completely quiet in the classroom when the students had to work independently on a computer. Of the 16 students who were in the room, six played computer games and were not active in the learning activity at all.

When asked why they think challenging behavior occurs during the interviews, all the teachers answered that this is a complex issue. Eight out of the 10 teachers specifically mentioned diagnoses as a factor, and several mentioned ADHD in particular. In addition to more medical explanatory models, several of the teachers highlighted other individual-oriented explanations, such as a lack of self-confidence, negative self-image and lack of academic and social competence. Many also mentioned difficult home situations as a reason for challenging behavior. All 10 teachers were clear that challenging behavior must be understood contextually, which can be interpreted to entail that none of the teachers locked themselves into one type of explanatory model. Overall, it was highlighted that the school has become more theoretical and that it embraces the diversity of interests and talents to a lesser extent than before.

He is really good at making things, technical things. He can work on an engine for a whole day and thinks it’s very nice to master it. But he is not allowed to use those abilities at school, and then inclusion is a bit of a bad word to use for his situation.

The teachers mostly discussed conditions that arise in the classroom in meetings between teachers and students. These can be a lack of adapted teaching, where tasks become too difficult, as well as tasks that can be too easy and, as a result, lead to boredom. Others indicated the lack of student participation as a possible cause. In addition, the relationship between teachers and students was highlighted as a key factor. One of the teachers described this in connection with a two-teacher system. When conflicts arise between students and the other adult, she said that she is often tempted to say to the adult, “Can you just walk away so I can sort it out?.” She said that she knows that she has a good relationship with most of the students and that, thereby, she is in a completely different position to resolve conflicts in the classroom than the other adults. She stated that it is actually easier when she is alone because then she gets the opportunity to handle potential conflict situations herself. Another teacher referred to a conflict between a student and another teacher and said, “To be completely honest, I think it depends a bit on who the teachers are.” Hence, several of the teachers were clear that the most important thing in relation to inclusion is to build a good relationship with the students.

All teachers used terms such as “to test” or “try to challenge us” when describing why challenging behavior occurs. They consider the behavior intentional and rational. Some saw this as a natural part of building relationships, where “testing teachers out” is a part of becoming confident in the teacher and finding out whether they are trustworthy. Others considered challenging behavior more as a cunning and calculated action directed at the teacher. They described that some students “think it’s fun to make the teacher a little sweaty and stressed” or that it is about “making the teacher insecure.” One of the teachers stated that challenging behavior is also about disrespect, reporting, “Students have less and less respect for us adults and also less and less respect for fellow students.”

The survey showed that grade levels seem to have a negligible impact on the reasons due to which teachers adopt challenging behavior. In other words, there was no significant difference in what a teacher of the first grade thinks about the connections between diagnoses and challenging behavior compared to one of the 10th grade. What emerged clearly was that different explanatory models associated with challenging behavior are closely linked to the attitudes toward segregated teaching. Being positive toward segregated teaching is positively correlated with individual-oriented explanatory models [rs(272) = 0.27, 95% CI (0.16, 0.38), p ≤ 0.001] and negatively correlated [rs(272) = −0.20, 95% CI (−0.31, −0.08), p ≤ 0.001] with explanatory models that emphasize contextual conditions related to teaching, the teacher or the school.

As described earlier, none of the teachers were locked into one-sided explanatory models. No students can be characterized based on one explanatory model. In addition, the students’ capacities vary from day to day and from situation to situation, and, thus, it is required that every situation must be assessed and analyzed individually. One teacher explained as follows:

I can only think of what happened yesterday. Then, there was a student who had a bad, a very bad day. If I just talked to her, if I just sat down next to her, just barely touched her, it was screaming and yelling. She was having such a hard time inside. She has no language to put it into words and is unable to regulate herself. She does not want to take a break… all the things we rehearse. She cannot do it with the other students in the room, and then it becomes difficult for an entire class. When it is completely quiet, and, suddenly, a desk comes flying through the room because the person she was playing with got more points than her in a math game.

The teachers highlighted that there would always be uncertainty about what is the wise and most appropriate response from the teacher in such situations. This illustrates that having some common boundaries and rules in a class and being sure that all the students have the capacity to meet these expectations entails a complex balance. One of the teachers talked about the time she took over a new class:

I probably challenged the students a little too much, because I set boundaries in a different way than they were used to. Then, there were two boys who reacted strongly. They often ran out of class. They cursed and called me, the class, the school and the principal incredibly rude things. They smashed windows; they ran on the roof. They had an extreme reaction. So, it became a complete clinch, and I learned a lot from it.

Another teacher said that much of the challenging behavior disappeared when they stopped pushing students “into a corner.” She mentioned that, a year ago, one of the students would often stand outside the classroom and throw stones at the window. He had stopped doing this recently, and the teacher believed this was related to the fact that they had created a sense of acceptance that students could take breaks and retire from class if they needed that.

In almost all observations, there were situations where the teacher had to consider whether they should meet the students with demands, considering the calculated risk that entails. The following example from one of the observations illustrates this:

The student who eats comes with constant interruptions, and the teacher must go to the student several times to calm him down. The student responds by throwing a piece of pizza across the classroom. Teacher says he should stop and go pick up what he threw. The student gets up, goes to pick up the piece of pizza, and then goes back to his place.

In this situation, in giving the student an order, the teacher could risk the student refusing to pick up the food, which, in turn, would create a new situation that could quickly develop into a power struggle. This shows how the teacher is constantly balancing on a knife’s edge, where timing and a wise response are crucial. Another example was observed when a teacher asked their students to make a choice and said, “If you are going to be in this classroom, you have to abide by the rules.” Here too, there was a possibility that the situation could escalate, with the students either ignoring the teacher or taking the teacher at her word and leaving the classroom. A teacher’s choice is thus closely linked to their assessment of what the student has the capacity for and their knowledge of the student. Further, the teacher’s choice was clearly related to the assessment of who is responsible for the behavior occurring. One of the teachers reflected on this and said the following:

I may have missed a bit with the level of a task, and that is often enough for the challenging student to find out that he cannot stand this. Then, he decides to walk around the classroom and throw things around the classroom for the rest of the lesson.

However, this statement does not mean that “students should do as they please” if the lesson does not engage them. In many of the observations, the teacher handled challenging behavior by giving the students more adapted academic or social work tasks. During an observation, one of the teachers had a goal for a lesson that all the students should practice putting on a bathing cap, as their first swimming lesson was the following day. The teacher was busy following up with one student at a time, and, hence, the students who were not trying on a swimming cap had to work individually on written assignments. After a short while, complete chaos broke out in the classroom. Many students walked around the room, and several of the boys fought. It was very noisy, and the noise came exclusively from non-academic activities. After trying to calm the class twice, the teacher responded by walking to the front of the class and saying, “That was not how I had imagined this lesson.” She then moved on to Plan B, which was watching a movie instead of undertaking written assignments. The students immediately went to their desks and calmed down. In the informal conversation after the observation, the teacher opened by saying, “Well, well. That is not how it should be done.” She was clearly embarrassed that her lesson had gone differently than she had planned. The teacher mentioned this lesson repeatedly during other informal conversations and almost apologized that someone had seen this. Although it was quite clear that the teacher “missed” with Plan A, the most interesting thing about the observation was the choice that the teacher made. Instead of placing responsibility on the students and making them responsible for not doing as told, the teacher took full responsibility. This appears as a classic example of the contextual and holistic approach that teachers must rely on when preventing and dealing with challenging behavior within the framework of an inclusive practice.

The analysis shows that the teachers’ judgment is decisive in the pedagogical response with which they counter the situations. This judgment is critical in the short term, as the situation can always escalate if the teacher handles it inappropriately. In addition, the judgment will be critical in the long run, as the choice of response will also affect the teacher–student relationship. Several of the teachers, therefore, mentioned that they are often worried about doing something wrong that can damage the relationship between them and their students. At the same time, the teachers were concerned that the response should also signal to the class what behavior is not acceptable. The teachers talked about a cross-pressure in terms of meeting one student’s needs and simultaneously taking care of all the students in the classroom. What also seemed to characterize situations where teachers are faced with challenging behavior is that, to a small extent, they experience the opportunity to take a step back to analyze the situations. Decisions must be made immediately in adrenaline-driven, chaotic situations:

What should I do? So, it’s buzzing in my head, and I’m wondering what to do. What do I do now? I have to say something; I must come up with something clever. I must calm him down. I must get things in place. Then you simply get an unpleasant feeling, but it’s probably a stress reaction.

One of the teachers stated that, in such stressful situations, she feels a lot of emotions. She does not necessarily get angry but gets a bit shaky and loses control over herself. One teacher said that she often reacts with anger, fear and despair at the same time. She referred to a specific situation and said that she first became furious and then became afraid that she crossed the line when she yelled. The teacher’s lack of control led to the fear that her reactions would not be pedagogical. She further stated that she thought that her own fear spread to the students. She experienced that the students saw that she was afraid and realized that she had no control over what she said and did. Many mentioned that the feeling of getting angry is often associated with disappointment with themselves as teachers and that they had “nothing more to contribute to rectify the situation.” The description of powerlessness was, therefore, repeated by most teachers. Another teacher used the term “wing clipped” several times to describe the feeling of not having good response options. Others talked about experiences of humiliation, frustration, breaking down in front of the class and the occurrence of anxiety attacks: “So, I felt so humiliated because I had received so many ugly comments, and the last one was … in a way, it was a minor issue, but that made the cup … I think it was powerlessness.”

One teacher who faced challenging behavior over time also said that the worst thing was that she was afraid to go to work. She dreaded it every day and developed a feeling of simply being a bad teacher. Several of the other teachers described a feeling of not being good enough as well as being in a continuous state of emergency where one wonders, “When will it blow? When will it blow?.” During an interview, one teacher also started to cry when she talked about her experiences. She spoke of a situation where she broke down in front of the class and later got the impression from her colleagues that she “perhaps should not show that weakness to the students.” When showing real and honest feelings is characterized as a weakness, one may ask how this affects the teachers’ reflection on their own practice. One can also ask how it affects reflections in the professional community. In the survey, teachers were asked whether, during their teacher education, they received training in making good decisions in stressful situations. In this regard, 82.59% of the teachers answered that they did not receive such training. When teachers were asked whether they practice making good decisions in stressful situations in their professional community at school, only 12.29% somewhat or completely agreed that they practiced this. One of the teachers mentioned in the interview that in school in general, there is far too little focus on what it does to teachers to experience challenging behavior. She believes that experiences such as the one described above are a larger part of the everyday life of teachers than anyone would like to admit.

There is no guidance for teachers to reflect on what it does to me when I am in a stressful situation, how I feel when I am scared, how I feel when I am tired or frustrated or do not know what to do. There are no arenas where this should be reflected on. But that is something that teachers experience all the time. When facing people who are struggling with emotional issues and disorders, then you need to be aware of yourself as a person. You need to be aware of who you are, what you think, how you react. If you have an adult in crisis who must deal with a young person in crisis, things can go really wrong.

Another teacher also reflected on this in connection with a very demanding situation that she had experienced recently. She said that she had a great need to talk through the situations with the others on the team, but she still failed to involve the others because she was unsure if it was interesting for them.

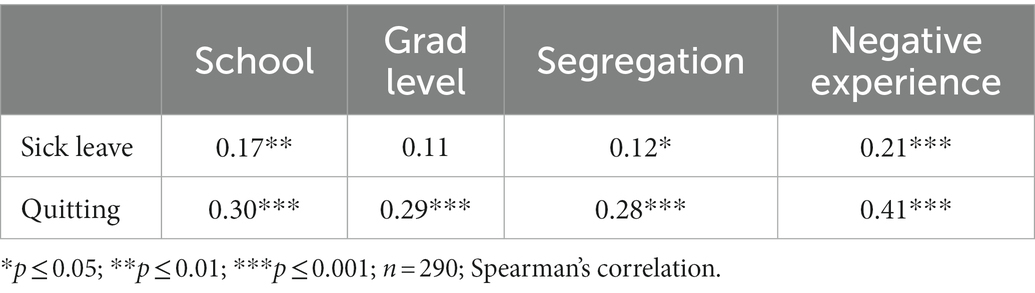

When the teachers in the survey were asked how often they experience what they themselves characterize as challenging behavior, 39.25% answered that they experience this every day, while 38.23% reported that they experienced this weekly. Facing challenging behavior often gives teachers negative experiences. In situations where challenging behavior occurs, 32.19% of teachers feel powerless on a daily or weekly basis, and 15.36% experience the feeling of being a bad teacher on a daily or weekly basis due to negative experiences related to challenging behavior. Moreover, 2% are scared at work every week, while a further 8% are scared at least once a month. The survey showed that 20.89% (n = 61) of the teachers had been on sick leave due to challenging behavior, while almost half (49.83%, n = 146) reported that they had considered leaving the job for the same reason. The odds ratio states that it is 5.7 times likelier that someone who has been on sick leave has considered quitting the job compared to someone who has not been on sick leave [OR = 5.71, 95% CI (2.81, 12.45), p ≤ 0.001]. As seen in Table 4, both sickness absences and the assessment of quitting as a teacher are positively correlated with perceived challenging behavior at school and in one’s own grade level.

Table 4. Sick leave, assessment of quitting as a teacher, challenging behavior, segregation and negative experiences.

It can be seen that sick leaves, especially in addition to the assessment of quitting as a teacher, are positively correlated with the attitudes toward the segregation of individual students and negative experiences with challenging behavior. Finally, there is a positive correlation between negative experiences and segregation, which reinforces the impression from Table 4 that a negative encounter with challenging behavior corresponds with positive attitudes toward segregation of individual students from ordinary teaching.

The research question in this article is “How can different explanatory models relating to inclusion and challenging behavior affect teachers’ work with an inclusive practice in school?.” Based on both qualitative and quantitative data, we have tried to shed light on this research question, and the findings of this study point to several interesting issues. In a literature review from Øen and Krumsvik (2021), it emerges that teachers often tend to rely on individual-oriented explanatory models when they are faced with challenging behavior. The same individual-oriented explanatory models are in use when Florian (2015) refers to “the bell curve thinking” as a challenge related to the development of inclusive practice. She stated that many students are often met with very low expectations in terms of both academic and social development. The teachers in the survey seemed to be very conscious of placing high, realistic expectations on the students. Completely disregarding individual-oriented explanatory models in favor of social explanatory models will thus also be problematic in the search for realistic expectations. Human diversity implies individual differences, and an inclusive practice precisely recognizes these differences through equality. Therefore, the development of an inclusive practice is about a constant balancing act, in which there will always be a risk of making mistakes. This is the nature of pedagogy, which was reiterated by Biesta (2016), who mentioned “the beautiful risk of education.” When students are subjected to expectations that are too high, it sometimes results in challenging behavior. The same can occur if expectations are too low. If high, realistic expectations for all students are at the core of the work with inclusive practice, the risk of challenging behavior occurring must also be a natural part of this work. When the classroom community also constitutes the hub of the work of inclusion, the students must also fulfil expectations regarding taking others into account. This is a demanding balance. A certain occurrence of challenging behavior can almost be seen as a logical consequence of teachers constantly searching for the right balance between realistic expectations and mastery within the framework of the community. Thus, inclusive practice cannot be assessed based on the extent of challenging behavior but, instead, on how the school and the teachers handle the challenging behavior.

The teachers in this study put in a great deal of preparatory work to prevent challenging behavior. Moreover, they talked about a continuous analysis of the pedagogical situation, where uncertainty is always present. When challenging behavior occurs, they seem to take great responsibility in the situation and often place the responsibility on themselves. This shows that they largely rely on contextual explanatory models where the students’ behavior is understood in relation to demands, expectations and teaching. Sometimes, they must protect both the class and themselves from physical attacks, and they described finding themselves in these situations as being very demanding. They must make decisions in situations with a high level of stress. Stress can be characterized as a condition or feeling where the demands of the situation exceed the personal and social resources the individual is able to mobilize (Phillips-Wren and Adya, 2020). The known stressors that also characterize the teaching profession are time pressure, complexity and uncertainty. High stress levels affect what can be referred to as decision quality. Stress often leads people to use more stereotypes while assessing the situation and ignore the context of the situation during decision-making (Wickens, 2002). Stressed people more often make hasty decisions, do not examine alternatives sufficiently and rely on oversimplified strategies (Hogarth and Makridakis, 1981). Under stressful conditions, it also seems that individuals resort to safe, well-known and previously applied strategies despite the fact that these may be insufficient for the challenging situation encountered (Kaempf et al., 1996). This, in turn, can lead to a gap between “espoused theory” and “theories in use” (Argyris and Schön, 1974, 1978), which results in a pedagogical practice that does not reflect the intentions, values and attitudes that the teachers want to express. A teacher may, for example, have the desire to meet challenging behavior in a calm and controlled manner and believe that they are doing just that. In practice, however, through fear and a high level of stress, they can unconsciously signal with their body language that one is both scared and angry. This, in turn, could “trigger” the situation such that it escalates. This can lead to feeling inadequate in terms of mastering the job as a teacher, which, in turn, can increase the chance of both them taking sick leaves and them leaving the profession.

For several years, the shortage of teachers in Norwegian schools has worried both the teaching industry and politicians. Some claim that there is no shortage of teachers in Norway at all, but the problem is that many teachers choose to work elsewhere rather than in schools. A report from the Ministry of Education and Research (Kunnskapsdepartementet, 2016) stated that approximately 25% of recent graduates choose to never enter the teaching profession. In addition, a further 16% choose to leave the profession after five years as a teacher. When many teachers also retire at a young age, it is reasonable to claim that the teaching profession is leaking from all directions. Other professionals who often face critical situations, such as the police, receive extensive training on dealing with such stressful situations. Nevertheless, the police have the authority to use force if the purpose is to enforce the law and what is right. However, what is “right” in a pedagogical situation is difficult to assess. What precisely characterizes pedagogical situations is the complexity which the teacher must navigate to balance goals and expectations that are sometimes demanding to reconcile. The teachers also reiterated that the relationships between them and their students are one of the most important factors in the work associated with inclusion. In critical situations, teachers are highly concerned that the student who exhibits challenging behavior should also be treated with respect and care. Teachers are afraid to make decisions that could damage the relationship between them and the student. An important part of the teachers’ understanding of inclusion is precisely that the student must be met with a blank slate every day regardless of what the student did the day before. Thus, inclusive practice seems to be about the teachers’ ability to make wise decisions.

An interesting approach to the development of inclusive practice is phronesis (Aristoteles, 2011) or practical wisdom. Such wisdom is what van Manen (1991) describes as pedagogical tact, and it requires high ethical awareness. Inclusive practice stemming from phronesis cannot be based solely on procedures and must first be developed through continuous reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action (Schön, 1991) individually and through the professional community. For many decades, researchers and practitioners have discussed what inclusion is and what inclusive practice looks like (Øen and Krumsvik, 2021). According to this study, it is just as relevant to discuss what characterizes the competence for inclusive practice among teachers. Such competence lies in a teacher’s ability to make wise and ethical decisions during daily classroom activity. The teachers’ descriptions of how they experience challenging behavior demonstrate that they can rarely withdraw to analyze the situation. Thus, a large part of their everyday life involves making decisions under a high level of stress, where they are scared, angry and desperate. Competence for inclusive practice with respect to challenging behavior is about making wise ethical decisions under a high level of stress. In such situations, teachers often struggle to identify good alternatives. Therefore, an important question is whether the competence required here is a part of the education for the teaching profession. As the survey illustrates, it appears that this type of competence development is absent in Norwegian teacher education even though inclusion is a key value. Nevertheless, practical wisdom in stressful situations must be developed primarily in practice. One can argue that such practice experiences should be a vital part of the teacher’s continuous professional development. Hence, teachers must practice in situations within a safe environment where fear, despair and the feeling of powerlessness are recognized as a part of their everyday lives. When such training is also absent in the professional communities in schools, it indicates that this is an underestimated and perhaps undiscovered component of the work on inclusive practice.

Although this study shed light on how inclusive practice can be understood and what competences are needed for its development, certain limitations should be mentioned. In this study, we have chosen to limit inclusive practice to what happens in the classroom and at the individual schools. The focus has been on how teachers’ explanatory models (Senge et al., 2005) provide guidelines for practice. We have not examined how national and local governance signals affect teachers’ explanatory models. The macro perspective has not been discussed in this study. Moreover, the study is based on teachers’ statements, practice and assessments. Parents’ and children’s assessments of inclusive practice could form the basis for other findings and analyzes. Corresponding studies where the child’s voice is heard can make an important contribution to the development of an inclusive school. We should also mention the relationship between the quantitative and qualitative data. Herein, there are no clear unambiguous connections related to the fact that the quantitative data exclusively confirmed the picture that the qualitative findings had formed. The various data bring out important nuances and, thereby, are primarily complementary. Moreover, it is important to emphasize that the number of participants in the survey (N = 293) makes it difficult to draw generalized conclusions. Thus, this study is simply a single piece that can contribute to a larger jigsaw puzzle.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by NSD - Norwegian Centre for Research Data. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

KØ in charge for all process, research idea, and design of the work, generating data, analysis, and interpretation of the data, main writer of the manuscript, and provided ethical approval for publication of the content. RK substantial contributions to the design of the work, generating survey data, analysis, and interpretation of the quantitative data, and provided contributions to the final manuscript. ØS substantial contributions in relation to analysis and interpretation of the quantitative data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study is part of the SUKIP project which is led by NLA university college. The SUKIP project is in turn funded by the Research Council of Norway (Project number 296636).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Allan, J. (2008). Rethinking Inclusive Education: The Philosophers of Difference in Practice 1. Aufl, 5. Springer Netherlands.

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. A. (1974). Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Aristoteles, (2011). Aristotle’s Nicomachean ethics (R. C. Bartlett & S. D. Collins, Trans). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Avramidis, E., and Norwich, B. (2002). Teachers’ attitudes towards integration/inclusion: a review of the literature. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 17, 129–147. doi: 10.1080/08856250210129056

Banaschewski, T., Brandeis, D., Heinrich, H., Albrecht, B., Brunner, E., and Rothenberger, A. (2003). Association of ADHD and conduct disorder – brain electrical evidence for the existence of a distinct subtype. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 44, 356–376. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00127

Barker, B., and Mills, C. (2018). The psy-disciplines go to school: psychiatric, psychological and psychotherapeutic approaches to inclusion in one UK primary school. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 22, 638–654. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2017.1395087

Barkley, R. A. (2012). Executive Functions: What They Are, How They Work, and Why They Evolved. New York City: Guilford Press. 50.

Berg, K. (2013). Teachers’ narratives on professional identities and inclusive education. Nordic Stud. Educ. 33, 269–283. doi: 10.18261/ISSN1891-5949-2013-04-03

Blackley, C., Redmond, P., and Peel, K. (2021). Teacher decision-making in the classroom: the influence of cognitive load and teacher affect. J. Educ. Teach. 47, 548–561. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2021.1902748

Borko, H., Livingston, C., and Shavelson, R. J. (1990). Teachers’ thinking about instruction. Remedial Spec. Educ. 11, 40–49. doi: 10.1177/074193259001100609

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa