94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 16 January 2024

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1339173

This article is part of the Research TopicPromoting Organizational Resilience to Sustain School Improvement EffortsView all 5 articles

Introduction: This article looks at organizational resilience (OR) through the analysis of a sub-set of data gained from an independent and embedded mixed methods implementation and process evaluation (IPE) of the Schools Partnership Program (SPP) implemented over 3 years (2018–2021) and funded by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) in England. We describe ways in which SPP ‘learning map’ addresses the (i) anticipation, (ii) coping and (iii) adaptation stages and the extent to which SPP helped building organizational resilience. Taking this theoretical framework as a foundation is a novelty, as despite OR has become prominent in the academic literature apart from a few exceptions there is a dearth of international research examining OR within the school sector.

Methods: A sample of 422 primary schools that took part in SPP (treatment schools) and their comparisons are analyzed applying the organizational capability-based framework. Drawing on SPP empirical data from numerous data collection strategies (interviews, surveys, shadowing school reviews and improvement workshops), the extent to which schools’ resilience capacities were improved is analyzed.

Results: Our findings suggest that SPP supported the development of OR in SPP primary schools. Despite facing several challenging external factors (student deprivation, the COVID disruption, changes to the external accountability framework and competing demands of other partner organizations) and internal factors (teacher attrition, need to developing leaders, upgrade pedagogical skills and encourage student subgroups who were underperforming) SPP schools exert (1) knowledge building through training, the review process, professional dialogue, learning from each other, as well as receiving and giving feedback. Regarding (2) resource availability, schools used SPP as a scaffold to build improvised strategies to access and mobilize shared human and physical resources; (3) social resources were built in the SPP through social capital, sharing of knowledge, enhancing a shared vision and trust. Finally, (4) SPP promoted lateral power dynamics driven by professional learning and accountability.

Discussion: Overall, the paper extends the understanding of school peer review approaches for school improvement and adds to the OR international literature by presenting features that extend it toward building system resilience.

Over the last decades organizational resilience (OR) has gained traction in the academic literature (e.g., Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007). Within the school sector, work on resilience has looked mostly at programs oriented to improve pupil resilience (e.g., Pinto et al., 2021). A smaller but nevertheless significant body of research has focused on teacher resilience and its relationship with school performance and teacher attrition (e.g., Gu and Day, 2007), as well as school wellbeing (e.g., Brown and Shay, 2021). However, there is a dearth of research examining OR within the school sector internationally, with a few exceptions (e.g., Kopp and Pesti, 2022). Recent conceptualisations of OR have shown strong overlap with the teacher resilience literature in that both see the concept as being a ‘dynamic’ rather than static process; and in the case of teacher resilience, this is seen as being mediated strongly by organizational and leadership elements (Gu and Day, 2007).

Drawing on research conducted in England between 2018 and 2021 and funded by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) (Godfrey et al., 2023) we employ mixed methods to look at threats to organizational performance at schools who participated in The Education Development Trust’s (EDT) Schools Partnership Program (SPP) over 3 years. Among significant data regarding external threats to school performance in treatment primary schools, we consider Income deprivation affecting children index (IDACI). Applying Duchek’s (2020) organizational capability-based framework, we describe ways in which SPP ‘learning map’ addresses the, (i) anticipation, (ii) coping and (iii) adaptation dimensions. Drawing on empirical data from interviews, surveys, shadowing school reviews and improvement workshops, the extent to which schools’ resilience capacities were improved is analyzed.

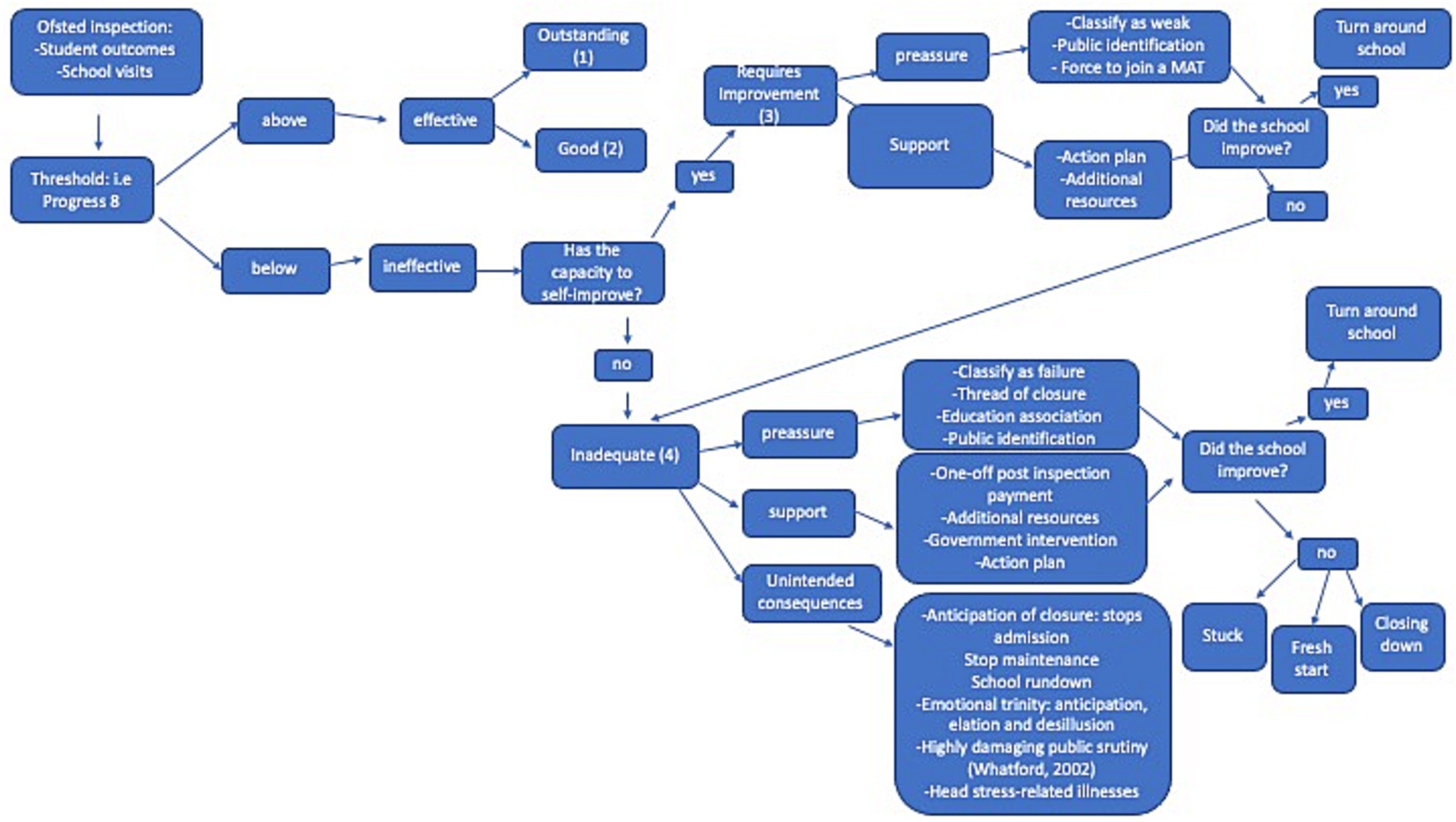

The current English school system is the result of the application of neoliberal principles of marketisation, competition for students, and parental choice (Ball, 2016). These principles have shaped a performative culture that paradoxically combines high autonomy and strong central accountability (Greany and Higham, 2018). Routinely schools are subjected to a high-stake external accountability regime by the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) that judges and publishes schools’ overall performance using a four-point scale: Outstanding (1), Good (2), Requires Improvement (3) or Inadequate (4). There are consequences for schools judged above and below the ‘good’ threshold, as summarized in the Figure 1.

Figure 1. Ofsted school inspection consequences according to overall performance grades (created by authors).

As described in Figure 1, schools judged as effective (Outstanding and Good), are granted more autonomy to operate. Those judged as ineffective (Requires Improvement and Inadequate) receive a combination of pressure and support intended to improve their effectiveness. One of these consequences is forced academisation. Yet, irrespective of where a school is positioned in the inspection hierarchy ‘inspection systems challenge the intrinsic value system of the teaching profession and give weight to extrinsic values and standards; they change the balance of power in and between education systems, schools and teachers. These changes in values and power will highly depend on the existing status quo in schools, particularly in the notions of school quality, the roles and responsibilities in shaping and implementing such notions, as well as in the attitudes and knowledge of school staff toward the external evaluation of their school’s quality’ (Ehren et al., 2015, p. 395). While teacher retention rates in the UK are at their lowest level since 2010 (NFER, 2023), their working hours are the highest of OECD countries, and are the most monitored through external inspection, it is clear how this performative culture takes a heavy toll (Perryman and Calvert, 2020). To regaining power, schools engage in a range of formal and informal alliances to provide mutual support, challenge and professional accountability. In this context, school improvement through peer learning partnership practices have emerged from policies designed to promote a self-improving school system (SISS), in which sustainable improvement of schools comes from bottom-up approaches and locally embedded activities. The SISS emphasizes:

• a structure of schools working in clusters and partnerships to promote improvement.

• a culture of constructing and implementing local approaches for improvement; addressing topics that are relevant for a specific locality.

• highly qualified people who act as system leaders in creating new knowledge, disseminating knowledge, and bringing schools together in partnership work (Hargreaves, 2010).

The 2010 coalition Government in England introduced academisation (independent state schools; many of these new academies formed Multi-Academy Trusts (MATs)); much like Charter schools in the USA, these formal organizational networks were funded by central government and thus work independently of local (education) authorities (LAs) in terms of school support and improvement. England now has a mix of schools funded by LAs and centrally as academies. Schools in the SPP would frequently be involved in other formal and informal partnerships, often providing synergy in collaborative school improvement, but sometimes experiencing tensions derived from competing aims of these formal and informal networks. Some schools worked together with their ‘fellow’ MAT schools using SPP methodology to conduct peer review within their organizational network, while others had a mix of LA and MAT schools.

During the period of the SPP evaluation we saw multiple exogenous challenges to the schools involved. Most notably, the COVID pandemic both tested the collaborative nature of the program as well as provided potential support. A new inspection framework was introduced in 2019 by Ofsted. This new framework led to a stronger focus on the school curriculum. Some of the SPP schools also worked in areas of multiple deprivation, which provides a useful context to analyze a subset of data.

This section examines the conceptual framework for the Schools Partnership Program (SPP), which in turn will be used in the next section for analyzing the evaluation findings. First, we examine a range of literature exploring the concept of school peer review, sometimes called peer enquiry or collaborative peer enquiry (Godfrey, 2020), as it forms one of the central pillars of the SPP. Then, we engage with the notion of Joint Practice Development (JPD), as it provides the theoretical rationale underpinning school peer review. Then, we explore the link between school accountability, and external and internal forms of school evaluation. Finally, we focus on the organizational resilience field specifically addressing the school sector.

To counterbalance a system of external accountability with the highest stakes of any European country (Hofer et al., 2020), England has developed a high prevalence of peer review practice among its schools (Godfrey, 2020). In a 2017 think piece, peer review was seen as increasingly part of local area partnerships’ change strategies and school improvement work (Gilbert, 2017). A survey conducted in 2018 found nearly half of all schools in England had engaged in peer review in the previous year (Greany and Higham, 2018). The benefits of peer learning between schools have been described in a report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2013), citing evidence from Belgium, England, and the Netherlands. In England Peer reviews promote lateral improvement, system leadership, and moral and professional accountability (Godfrey, 2020).

School peer review refers to collaborations between schools involving mutual or reciprocal school visits to collect data, learn from the other school’s context and provide feedback on an aspect of school function. Despite on the surface school peer reviews resemble school inspection visits, they are markedly different as they are a form of internal evaluation, the reviews are voluntary, reports are kept internal to the schools, and the focus of the evaluation is decided (sometimes in discussion with partner schools) by the school itself.

Establishing effective school peer reviews is not without challenges, requiring an existing culture of school self-evaluation, strong supportive infrastructure, and trust between participant schools (Godfrey, 2020). Part of this supportive network requires regular ‘training’, by which we mean specific learning of a task or skill within a peer review process, such as evidence scrutiny, coaching, feedback, or leading an improvement workshop. Yet, the dominance of the Ofsted inspection model can also lead participants into merely preparing for inspections (so-called Mocksteds) instead of engaging in an open process of learning, and at worst, engaging in self-policing (Greany, 2020).

School peer reviews involve a process of evaluation, with its own sets of protocols and practices for collecting and analyzing data. However, school peer reviews (or peer enquiry) models can also be considered as a form of Joint Practice Development (JPD) in which knowledge is not seen to be transferred from expert to receiver (as in traditional continual professional development models), but where learning is practice-based, mutually beneficial and research-informed (Sebba et al., 2012). Thus, reviewers in school peer reviews learn as much from observing practice as the host school does from receiving visitors’ feedback. In the JPD SPP, the review was an enquiry based around agreed focus questions, and academic research was later introduced to support the recommendations of the reviewing team, alongside other school-based evidence and data.

One of the most impressive and consistent findings in evaluations of peer review programs, is that they are highly effective ways of developing school leadership (Godfrey, 2020).

This and other OR related themes, are further explored below.

Organizational resilience has been defined as ‘maintenance of positive adjustment under challenging conditions such that the organization emerges from those conditions strengthened and more resourceful’ (Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007, p. 3418). This definition suggests a character of a resilient organization, that while not guaranteeing a robust response to future threats, should nevertheless increase its probability. In other words, resilience is an ongoing organizational feature, not just a response to specific challenges. Furthermore, OR results from ‘processes and dynamics that create or retain resources (cognitive, emotional, relational, or structural) in a form sufficiently flexible, storable, convertible, and malleable that enables organizations to successfully cope with and learn from the unexpected’ (Sutcliffe and Vogus, 2003, p. 3419 in Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007).

Among the mechanisms of resilience Vogus and Sutcliffe (2007) state the early anticipation of potential threats and deviations from normal organizational performance as threatening to organizational health. Staff within resilient organizations have a sense of collective efficacy, i.e., they have a belief that they will be able to make a difference to performance despite external challenges. The behaviors associated with OR include questioning assumptions and received wisdom, discussing human and organizational capabilities, learning collectively from errors, and distributing decisions to the people with greatest expertise, regardless of rank. Affectively, resilient organizations are less ‘optimistic’ and more ‘hopeful’ based on a realistic assessment of their situation and resources to cope with threats. Finally, Vogus and Sutcliffe (2007), show that such organizations engage in a ‘superior brand of learning’ (p. 3421), albeit suggesting more research would be needed to understand the character of this learning.

After reviewing the literature, Duchek (2020) suggests that the main antecedent of OR is its knowledge base. Organizations need to develop a broad understanding of their field, avoid getting stuck in surface explanations and encourage a diversity of skills, personalities and perspectives in decision-making that promote creativity and innovation. Duchek (2020) also argues that underpinning the development of this knowledge base, are the drivers of resource availability, social resources and power dynamics. Availability of resources, time and personnel, including having staff who can scan the organizational environment to avoid focusing on only internal solutions. Building social capital with colleagues is important, including sharing visions with organizations and networks and supportive dialogues and teams based on mutual trust. This enables the sharing of knowledge and the revelation of deep underlying issues and problems that need to be solved. Finally, whether new knowledge is put into effective practice in the organizations often depends on the power dynamics. Duchek concludes that hierarchical power relationships are not conducive to the implementation of new ideas, rather these should be based on expertise and shared responsibility.

Duchek’s (2020) capability-based conceptualization (CBC) of OR, also describes the before (anticipation), during (coping) and after (adaptation) processes or stages of OR. More precisely, (1) Anticipation entails monitoring the performance of the organization and recognizing where this is below the expected or desired level. This stage requires skills of observation, data collection, the use of a prior knowledge base to analyze the situation and is both aided by and affects the identification of resource availability. This happens in anticipation of an unexpected event, with the desire to take proactive action; (2) Coping requires the affective dimension of accepting the current situation (based on the prior analysis) and then involves developing and implementing approaches to deal with this, building on the first stage. Here, the social resources - teams, collegiality, support, leadership and so on – are crucial to developing solutions during the challenge itself; finally (3) Adaptation is characterized by reflection and learning, leading to change, and is the stage where power and responsibility dynamics come into play. Here, as with other stages, actions can be both cognitive and behavioral. This stage then informs further understanding of the situation (and other associated challenges), feeding into new ‘prior knowledge’ to face novel challenges.

Within the field of educational effectiveness and improvement a growing body of literature is suggesting that generic leadership practices (Leithwood et al., 2020) need to be situated and adapted, especially when applied to challenging contexts (Hirsh et al., 2023). An increasingly documented reality is that no size fits all when describing effective leadership in schools located far from the norm. In the field of educational effectiveness new conceptualizations are replacing deficit models for problem-solving approaches that emphasize what school leaders and communities do to lead effective organizations (Day, 2014) instead of focusing on what they lack.

Research on resilience gained traction during the last pandemic to learn from those best practices that helped students, teachers, leaders and school communities endure adversity. The concept of resilience has its origins in physics to describe the ability of materials to absorb and release energy without leaving permanent distortions. For example, plastic is more resilient than iron as it is more ductile and less likely to break. In psychology, resilience has been defined as the individual ability to bounce back from adversity without psychological damage (Kotliarenco et al., 1997). In the last decade, literature on leadership has included resilience as a trait of effectiveness. ‘Most successful school leaders are open-minded and ready to learn from others. They are also flexible rather than dogmatic in their thinking within a system of core values, persistent (e.g., in pursuit of high expectations of staff motivation, commitment, learning and achievement for all), resilient and optimistic’ (Day et al., 2009, p. 29). While resilient leadership has been defined as ‘leading in the face of adversity’ (Olmo-Extremera et al., 2022, p. 1) by extending this definition to organisations, resilient organizations can be understood as those working in disadvantaged contexts who achieve relatively high levels of performance. However, more research is needed to extend the definition of resilient leadership to organizations, as research on schools working in disadvantaged contexts found that despite these schools significantly improved students’ academic outcomes, they remained judged as ineffective by the inspectorate (Munoz-Chereau et al., 2022).

The context in which schools are operating seems to play a key role in why certain schools perform according to expectations while others fail. In England, schools with a disadvantaged intake or with a high proportion of pupils with low prior attainment are five times more likely to have their overall quality rated inadequate by Ofsted than those with better intakes, and less than half as likely to be rated outstanding (Hutchinson, 2016). Also, the inspection outcome itself affects the socio-economic composition of schools. After analyzing 10 years of Ofsted inspections, an inverse association between Ofsted grades and changes in schools’ student deprivation composition was established: whilst schools judged good or outstanding tended to see reductions in the proportion of their students who are eligible for FSM (Free School Meals), the opposite was true for schools judged as less than good (Greany and Higham, 2018).

Apart from responses to continuous contextual hardship, resilience in education has stressed its relational nature. Day (2014) researched how 12 leaders in schools serving high-challenge communities of socio-economic disadvantage internationally sustained their resilience. He highlighted personal factors- such as courage and conviction- but also organizational factors influencing leaders’ capacity to manage anticipated and unanticipated challenges. Day coined the term ‘everyday resilience’ to refer to ‘a resolute everyday persistence and commitment, which is much more than the ability to bounce back in adverse circumstances. The social environment is important, and resilience can be fostered or diminished through the environment (for example, leadership interventions in establishing and nurturing structures and cultures)’ (Op. cit, p. 641).

Researchers are progressively reporting differing repertoire of practices of leaders working in disadvantaged and more advantaged communities. As schools educating socioeconomically disadvantaged communities face greater challenges -such as lower staff commitment and retention, student behavior, motivation, and achievement- than those working in more advantaged communities, ‘the sets of skills and attributes used by successful principals in more disadvantaged schools is different and, we found, more complex, than those in more advantaged schools’ (Day, 2014, p. 642). As these leaders face persistent levels of challenge, they apply greater combinations of strategies, and a wider range of (inter)personal skills than those working in advantaged communities (Day, 2014). Yet this comes at a cost, as these leaders are likely to be less experienced and stay for shorter periods than those in more advantaged communities (Day et al., 2020). After reviewing international literature, Day and Gurr (2013) concluded that resilient leadership was characterised by academic optimism, trust, hope, and ethical purpose or conviction. In Sweden, the situated nature of leadership was recently explored qualitatively in 20 schools of low-socio-economic status. To maintain resilient organizations, leaders were ‘present, gatekeeping, sheltering, collaborative, and compensatory’ (Hirsh et al., 2023, p. 1). The authors concluded that this context-specific skill set could be enhanced through context-sensitive training and support provided by local education administrations and universities.

In the educational literature, resilience research has tended to focus on teachers, examining issues underpinning the reasons for leaving the profession. When examining OR, particular attention needs to be paid to the role of teachers, given their centrality to the goals of the organisation – i.e., educating young people. It is widely accepted that the quality of teaching makes an important difference to students’ academic outcomes (Hattie, 2003; Rockoff, 2004) and that school leadership, while secondary in the effects to improve students’ outcomes, is nevertheless central to this (Day et al., 2016). Since the performance of teachers is so important to schools and attrition so detrimental to building the skills required to become an expert teacher (Allen and Sims, 2018), teacher resilience then becomes of paramount importance. Teacher resilience has been defined as ‘the capacity to maintain equilibrium and a sense of commitment and agency in the everyday worlds in which teachers teach’ (Gu and Day, 2013, p. 26). Therefore, teacher retention can be seen as the outcome of teacher resilience.

However, teacher retention is best understood not as a characteristic residing purely within an individual but a dynamic process relating to leadership and organizational factors. In a study of 300 secondary school teachers in England, Gu and Day (2013), identified, over a 3 year period, that ‘teachers were working under considerable persistent and negative pressures and that these were largely connected to poor relationships with school leadership and colleagues, deteriorating pupil behavior and attitudes, lack of parental support, the effects of government policies and unanticipated life events which had led to a weakening of their core commitment and educational values’ (p. 27). In a survey in England, nearly 40% of teachers of the 1,000 questioned had considered leaving the profession because of disruptive pupil behavior; and more than a fifth said they had developed mental health problems [Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL), 2010, in Gu and Day, 2013, pp. 23–24]. In Gu and Day’s (2013) research, insufficient collegiality and leadership support reduced teacher resilience. Teacher resilience was also shown to be negatively correlated with the socio-economic context of the school.

The relationship between organizational support, teacher well-being and teacher resilience has been established elsewhere. In a study of Ohio public (secondary) schools, using an explanatory sequential mixed methods research design, 254 teachers were surveyed followed up by 10 interviews. The interview data indicated that teachers with higher resilience experienced more support from leaders, were treated as professionals, given recognition, worked in teams and had adequate resources. These staff had effective teaching skills, good relationships and had flexible mindsets. The study implies that organizational practices, polices and routines, alongside supportive leaders and a collegial environment created a sense of teacher well-being, provided protective factors or conditions for the development of resilience.

As Gu (2018), explains in her social ecological model, four propositions underpin teacher resilience: (1), Teacher resilience is associated with teachers’ identities and values, i.e., as a vocation in which practitioners wish to grow, to learn and to have high self and collective-efficacy; (2) It is built through relationships, where relational trust is essential, strong collegial connections and social support; (3)Teacher resilience is a necessary but insufficient condition for teachers to be effective. That is to say, they also need to be knowledgeable about their students, their subject, and about management tasks; and (4) Building and sustaining resilience is more than an individual responsibility. Promoting and cultivating healthy individual and collective learning and achievement cultures in schools is essential to how teachers feel about themselves as professionals.

In summary, in the school context organizational, leader and teacher resilience are overlapping and complementary dimensions.

SPP aims to develop a culture of partnership working through school self-evaluation, peer review, and school-to-school support (for a fuller description of the program see Godfrey et al., 2023). Self-formed partnerships signed up to the program and a partnership lead was decided from within this group of schools, usually one of the headteachers (principals) in the partnership. School leaders were joined by other senior, middle leaders and teachers in the schools to train to participate in the program. Workshops and training occurred at least three times a year to prepare participating staff, and to provide top-up training for new staff. Schools conducted a self-evaluation using the SPP framework that asked participants to consider ‘to what extent’ questions. These were designed to set the tone of the review as an evidence and enquiry-based process. A pre-review meeting between lead reviewer and headteacher of the host school started the process of review, deciding the focus and finalizing the timetable for the visiting review team.

Schools worked in small clusters (usually around 5 or 6) and took turns to review each other. Reviews lasted 1 day, were led by a lead reviewer (normally a headteacher) and assisted usually by another reviewer (a senior leader). Typically reviews involved scrutiny of documents and school data, classroom observations, and interviews with staff and students. The day ended in a feedback discussion between reviewers and the host school leadership team. Improvement Champions (ICs), usually two middle or senior leaders from other schools, attended final feedback in the review. ICs led a facilitative coaching discussion with the host school staff in an ‘improvement workshop’ approximately 2 weeks later, normally after school hours, and lasted around 1.5 h. Staff in the host school were encouraged to come up with their own solutions to the review report findings and recommendations. ICs were encouraged to introduce research evidence on the topic of the review in the improvement workshop. Schools were expected to have ‘90-day’ progress discussions between headteachers in the partnership to check progress after the review. EDT workshops encouraged half yearly and full year reflections on progress and identification of ways to implement changes and to adjust practices to work more effectively in partnership. The cycle would be repeated, usually in the second year (although in this evaluation there were interruptions and extensions due to COVID).

At cluster level, the program was set up to increase collaborative leadership, to improve transparency and data sharing, and to develop a culture of shared responsibility. At leadership level, there should be increased leadership of collaborative school improvement, strengthened lateral trust between leadership teams, embedding of peer review, and the follow up of school-to-school support. Finally, at teacher level, the program was designed to increase ownership and engagement in strategies for improvement, improved lateral trust between teachers within and across schools, and improved awareness of improvement priorities and responsibility for changing practice. The cluster, leadership and teacher level outcomes were designed to improve outcomes at the student level, which would vary depending on the self-determined focus of the schools in their reviews.

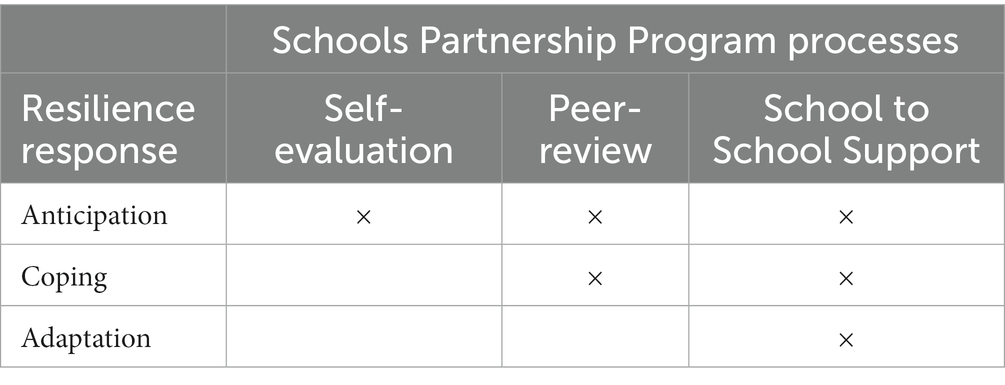

The SPP model can be seen as illustrative of the OR stages mapped out by Duchek (2020). We can see how the CBC model maps onto the three overall change processes in the SPP model of self-evaluation, peer review and school to school support (Table 1):

Table 1. The Schools Partnership Program processes mapped against the capability-based conceptualisation of organizational resilience.

The SPP seeks to develop an anticipation of challenges to performance, by providing training and a framework for effective school self-evaluation. This process is further validated, consolidated and/or challenged by reviewers from outside the school, adding a further ‘pair of eyes’ and in providing some feedback on strategies in place, and suggestions for refinement. School support is woven into the program, since schools work in clusters, helping each other to identify critical performance issues and deciding on a potential area of focus for the enquiry (anticipation). Having received a review, the school hosts an improvement workshop around 2 weeks later in which staff are encouraged to come up with new strategies (coping) using a coaching model led by ‘Improvement Champions’, usually two trained middle leaders from other schools in the cluster. Finally, a ‘90 day’ follow up involves senior leaders in partnerships touching base to evaluate and discuss the success of these strategies. SPP workshops also provide a further infrastructure of support, in which clusters come together mid and end of year and are assisted in evaluating their change process, they are provided with leadership and other tools to lead these changes and engage in systematic professional dialogue to derive lessons learned at the end of the school year.

An independent evaluation of SPP was conducted by a team of academics at UCL Centre for Educational Leadership (Godfrey et al., 2023). This was set up as a quasi-experimental impact evaluation using school-level matched difference in differences involving 422 primary schools in the treatment group and 374 in the matched or comparison group. Secondly, an embedded mixed methods implementation and process evaluation (IPE) combined numerous data collection strategies to gain in depth understanding of the mechanisms of the program, and questions of fidelity, adaptation and differentiation. As the evaluation occurred between 2018 and 2021, student level data was unavailable due to disruptions in the national examinations derived from school closures during COVID. However, the IPE was expanded, along with the period of the evaluation, in order to gain further insights into how participants perceived the impact of participation and how COVID impacted on its operation. The evaluation was designed to look at the ways SPP influenced the capability, culture, and practice of partnerships, leadership, and teachers in treatment schools; how it worked to achieve participants’ perceived forms of impact; the factors involved in sustaining engagement in the program, including why some withdrew and to look at the difference COVID-19 made to the operation, participant engagement, and perceived forms of impact of the SPP.

The IPE included initial and final surveys of treatment schools and explored the counterfactual using interviews and surveys with matched or comparison schools. We conducted intensive case studies of two clusters of treatment schools, one in the north and one in the south of England, the former being in a more deprived, urban setting and the latter in a wealthier, rural area. Each cluster involved five schools. For each case study we conducted two sets of interviews with key staff, shadowed their training and some of their reviews. We also interviewed senior leaders in matched or comparison schools, observed EDT training, and the reviewing process in one more cluster, outside of our case studies. We supplemented our IPE with additional group interviews of key stakeholders, including SPP permanent staff, associated staff (facilitators), partnership leads, and ICs. Our own independent evaluation data was supplemented by evaluation records from the SPP project team. We thus triangulated our data collection from multiple data collection methods (interviews, observations, and surveys); and multiple sources of data—including headteachers, senior and middle leaders and other program staff, across different schools and regions; and over various time points. Validity was further strengthened by having multiple perspectives of researchers and through holding regular team meetings in which we discussed emerging findings. Table 2 below gives a detailed overview of IPE methods.

Recruitment to the study was carried out by the project team (EDT), drawing on their national databases to contact schools. They advertised the evaluation and approached schools through their existing networks, and successfully recruited 422 English state-funded primary schools that started the evaluation. Initial partnerships ranged from 2 schools to 15 in size, but larger ones split into smaller clusters for the purposes of reviewing each other, usually between 4 and 6 schools.

All recruited schools received the intervention, while statistical matching methods were used to identify the matched or comparison group using publicly available school performance data on the Department for Education website. The matching variables included the Key Stage 2 reading score and mathematics of the school in 2017; the number of pupils in the school in 2017; school’s most recent inspection (Ofsted) rating in 2017; the deprivation of the school’s intake; and the region in which the school was located.

We recorded the income deprivation affecting children index (IDACI) for each school. In the treatment group, the breakdown was as follows (Table 3):

In our treatment group, the proportions of schools’ Ofsted ratings were, 17% Outstanding (1), 71% Good (2) and 10% Requires Improvement (3), with none in the rated inadequate category. 18% of the treatment group were Academies and 82% were local authority or other categories of school.

On these dimensions the sample was formed by a balanced representation of primary schools in England and the treatment group very closely matched the comparison schools.

Using the matching variables, the evaluation team were able to identify case study schools that matched our treatment school cluster case studies and to take part in interviews and a final comparison schools’ survey. Respondents to the surveys were headteachers1 (81%) or senior school leaders. Of our treatment schools final survey, we had responses from 23 schools that had withdrawn from the study (but had at least participated for the first few months) to gain an understanding of their reasons for withdrawal and to understand their perceptions of the program more generally.

To be fully compliant, treatment schools had to receive at least two reviews and to have attended at least 75% of the training and workshops over the period of the evaluation. To be minimally compliant, schools had to attend some of the training and to have received one review. All others were considered non-compliant. On this basis, 16% of schools were considered fully compliant and 40% minimally compliant. Analysis of the IPE survey showed very few differences between responses of headteachers from minimally compliant versus fully compliant schools, therefore we pooled these to 56% that completed the evaluation (238 schools) and compared responses on the survey to the remaining 44% non-compliant (184 schools). EDT data suggests only 57 schools withdrew prior to COVID (31%), with the remaining 181 schools (69%) withdrew post COVID. Of the 137 schools that supplied reasons to EDT for withdrawing, 66% gave COVID as a response, followed by ‘lack of capacity’ (21%) as the next top answer (multiple responses were possible). As the original evaluation was only intended to be 2 years’ long, some schools will have decided to withdraw at the end of this period in any case. Several new schools entered a partnership during the evaluation period but their data was not included in this analysis.

For the purposes of this paper, our research question is:

To what extent did the Schools Partnership Program build organizational resilience in participating primary schools?

Despite SPP schools facing several challenging external factors (student deprivation, the COVID disruption, changes to the external accountability framework and competing demands of other partner organizations) and internal factors (teacher attrition, need to developing leaders, upgrade pedagogical skills and encourage student subgroups who were underperforming), they developed organizational resilience to overcome these factors. We present findings from a variety of data points that relate specifically to factors that Duchek’s (2020) identified as capabilities for developing OR: knowledge building, resource availability, social resources, and power dynamics.

School’s knowledge base was built through both training and other sessions offered on the program and through the review process, learning from others and by receiving feedback from others.

In the training stage, senior leader participants learned how to conduct a school review and improvement champions (ICs), usually middle leaders or teachers, learned how to lead an improvement workshop (IW) in a reviewed school. Reviewers learned the skills of forming an appropriate enquiry question, evaluating a range of school data, and providing oral and written feedback to a host school’s leadership team. ICs learned how to set up a workshop and follow a coaching model to encourage the reviewed school team to prioritize key action points in relation to the focus of the review and its findings. In later training, ICs also learned how to introduce published research to reviewed schools, so that authoritative external evidence could be applied to the problem at hand. Our observations of training showed very skilful and experienced facilitators and the final surveys showed very strong satisfaction by headteachers of SPP training overall.

Knowledge about specific school improvement issues or dealing with specific challenges was derived from both SPP training, in the research articles circulated by ICs and through professional dialogue between schools in their clusters. To name some examples, once schools returned after the first lockdown, the SPP team laid on additional workshops about the catch-up curriculum, with an expert speaker, to help schools focus on strategies to help students that had fallen behind from school closures. Also, schools shared ideas about digital learning, making it the focus of some of the reviews. Knowledge was shared when visiting reviewers, often experienced headteachers, were able to pass on their own strategies for dealing with problems to a school they were reviewing. Whether this advice was received well, depended on both the credibility of the reviewer and in the readiness of school staff to accept feedback.

In one of our case study schools, the headteacher turned the focus of her school’s review to how to strengthen the middle leadership team, particularly in relation to how they managed the curriculum in both numeracy and literacy areas of the school. This was a direct response to Ofsted’s new guidance to inspectors and focus on curriculum. In this way, the school received feedback from a knowledgeable headteacher in the cluster on these areas.

In our interviews with SPP case study school leaders (and comparison schools for that matter), a few of them identified resourcing challenges to school improvement efforts, partly provoked by the government’s academisation process. One headteacher said that their local authority, now stripped of resources due to schools’ conversion to academies were now passing this cost onto schools, which had forced them to look to for other forms of collaboration for school improvement.

‘I mean we came together as a [SPP] cluster originally over disenchantment with [local authority] about newly qualified teachers because their program was costing hundreds. We did not have the money. I mean financially, we are not too bad off, I’ll be honest, but a lot of our group could not afford it so we thought, well why are we paying when we can do it between us?’ (Headteacher, school 1d, year one).

Rather than conform to the pressure to join a local MAT, schools in the above case study decided to build on an existing local alliance and used SPP to add more structure to this. This was a theme shown in our overall survey, that the SPP was seen to strengthen existing partnerships, providing a more effective way of working and learning together and for greater sharing of resources. As an example, during COVID, one treatment group case study partnership collaborated by sharing school premises, enabling some of the schools to close completely while a smaller number, sharing staff, stayed open to look after children of key workers. There were other examples given in interviews, such as greater sharing of teacher team expertise and shared professional development sessions. These were partly about pooling resources, and as much about sharing expertise. The relatively small size of many primary schools made collaboration a strong imperative in general. Looking at some of our treatment school survey items, we can see strong agreement about this building of structure in networks, for instance, when asked about the main benefits of SPP, the top answer listed was:

• Building networks and partnerships (52% of respondents listed answers in this category)

The top priority listed for SPP was given as:

• Sustained focus on teaching quality and improvement (29% of respondents listed answers to do with this), alongside many more specific ones, such as improving reading (27%), mathematics (24%), writing (23%) and curriculum development (19%).

Thus the raison d’être for collaboration for the majority of schools was to improve performance in key areas of schools’ function during the period of the evaluation. Interestingly, responding specifically to the post-covid situation, and remote teaching was only listed by 6% of respondents in the treatment schools survey.

The sense of working together to address resourcing for school improvement was conveyed clearly in this extract from an interview with one of our SPP case study headteachers:

‘Now as time has gone on, we have had training days together, so all the staff have spent days together and lots of things like that, like staff from the other schools have delivered CPD for the other schools, not just the improvement workshops but completely unrelated CPD … It’s not formal, we are not charging each other, we’ll just pay it back with another favor, but I do think that’s got deeper now’ (Headteacher case school 1e, year one).

We also found that one of the principal reasons for withdrawing from the SPP was given as lack of staffing and time capacity to participate. This was second to COVID as a reason for withdrawal, with 66% stating COVID and 21% citing capacity issues. Changes in school leadership, were also cited by 35% respondents in the final survey. Furthermore, while the impact of the IC role was given prominence in the final survey due to its leadership of change role and development of middle leaders, it was also seen to be one of the most challenging roles to undertake, so getting the right people was seen as crucial.

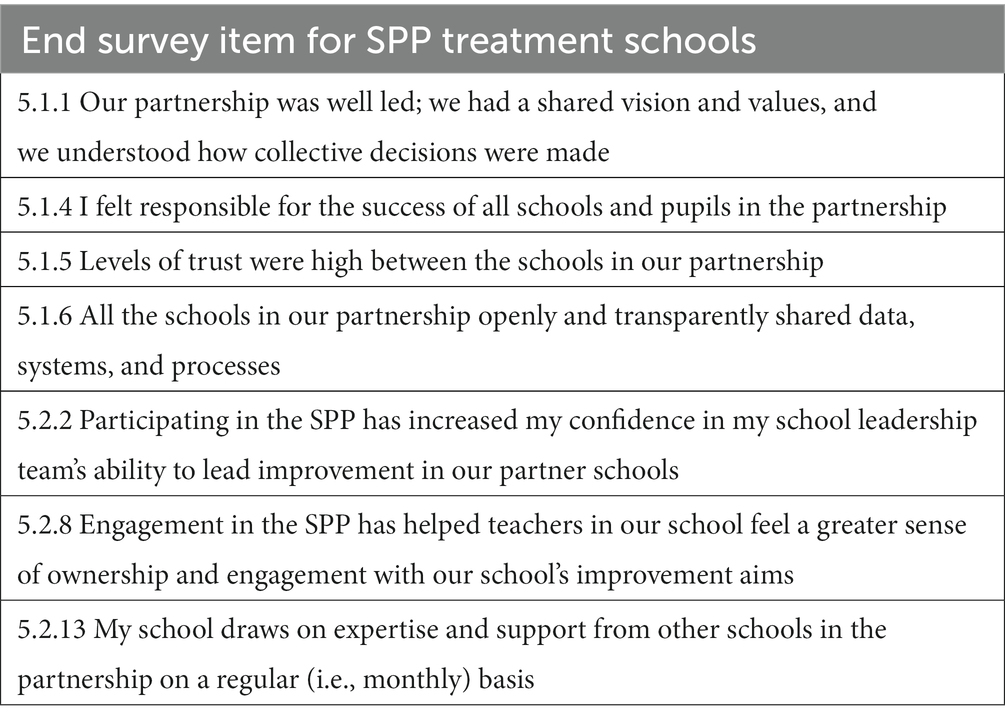

Building on social capital, sharing of knowledge, enhancing a shared vision and trust were seen as features of our evaluation data in treatment schools.

We compared initial school leader self-reported responses (year one of the evaluation) with the end (year three). Below we show some of the significant differences and associations in the data.2

Comparing the initial and end treatment schools’ survey, we saw an increase in agreement that:

• teachers felt a sense of ownership of and engagement with the improvement aims of all the schools in their SPP partnership (from 15 to 34%)

For the statement:

• Engagement in the SPP has helped teachers in our school feel a sense of ownership of and engagement with our school’s improvement aims (88% respondents felt this was strong at the start of the program, and 64% stated that this had increased at the end)

We saw increases in knowledge exchange between partner schools, to the statements:

• All the schools in our partnership openly and transparently share data, systems, and processes (from 68 to 91%)

• My school draws on expertise and support from other schools in the partnership on a regular (i.e., monthly) basis (from 54 to 68%)

When we likened SPP treatment school responses to comparison schools, we find higher agreement in treatment schools for:

• All the schools in our partnership openly and transparently shared data, systems, and processes (91% vs. 77%)

Other responses were rated at a similarly high level to comparison schools, who were rating their survey responses in relation to ‘my most significant school improvement partnership over the last 3 years’, including statements about the benefits of this partnership work on leadership development. It is useful to note that we included responses in the SPP survey for both schools that completed and schools that were only partly compliant or had withdrawn before the end of the evaluation. Another important point is that, of the comparison schools surveyed, 61% said they had engaged in peer review over the previous 3 years and 50% said that peer review was firmly embedded in their practices (compared to 60% of the SPP respondents surveyed). Therefore it was not so much peer review that distinguished schools in our treatment group, but the participation in this particular program – a program that also had elements of school to school support and other features of leadership development.

Schools with deprived student intake seemed to benefit particularly strongly from knowledge exchange and the development of collective responsibility for improvement. Of the 157 schools (i.e., school leaders) that completed the final treatment survey, 41 were in IDACI quintile 1 (least deprived student intake), 41 were in IDACI quintile 2, 39 were in IDACI quintile 3, 22 were in IDACI quintile 4, and 14 were in IDACI quintile 5. School leaders from SPP schools in IDACI quintile 5 (most deprived student intake) were more likely to agree that they shared data, systems and processes, and that they drew on expertise and support from partner schools. IDACI 5 schools agreed, more than IDACI 1 schools, that they had developed teachers’ sense of ownership and engagement with their school’s improvement aims (see Table 4 below).

Table 4. Survey relationships where responses showed significantly higher agreement in IDACI 5 (most deprived student intake) compared to IDACI 1 (least deprived student intake).

We did not find this variation in responses from school leaders in the comparison schools. Given the small sample size of IDACI 5 schools, we need to exercise caution in these findings. Nevertheless, these significantly higher ratings of benefits of participation from school leaders in schools with highly deprived student intakes warrants further investigation.

The role of the program in helping participants get through the Covid challenges was one area however, in which the SPP did not rate highly. The most popular response was to neither agree nor disagree to this statement (35%) and with 46% disagreeing. While one headteacher in our case study schools did talk about being glad to be able to pick up the phone and have a supportive colleague, it was understood that this was an already existing local alliance. The key issue is that, while remote peer reviewing was offered – and there was some limited take up of this – most schools wanted to wait until they were able to get back to in-person reviews. In other words, one of the strengths of SPP was the in-situ learning and professional dialogue that ensued.

Evaluation collected by EDT after year one showed that partnership leads were not systematically (or at all) using the 90 day follow up. In the light of this, a webinar open to all partnership leads (PLs) focused on providing a structure for sharing progress and for the other school leaders in the cluster to support or challenge the progress made. We do not have systematic data on this, or the extent to which this support or challenge led to change, although one of our case study PLs mentioned that this was now more formally included in their regular meetings and this was felt to help keep things on track.

SPP is set up with the specific intention of promoting lateral and professional learning and accountability. The notion of ‘peer review’ is central to its mission and theory of change and added to the sense of collective responsibility for change and leadership of this across schools. Peer review was seen as a shared enquiry rather than a top-down evaluation by a more senior leader or an external authority, this headteacher comment is an example:

‘So because it’s your peers coming in, people do not see it as a judgemental process. We’re quite clear about that when we go into things; you are not here to pass judgment. You’re here to I suppose … I talk about this phrase a lot but in a way you air your dirty laundry to people and actually you want another person’s perspective on this particular problem that you identify in the enquiry approach.’ (Headteacher and Partnership lead).

We found strong support for this sense of shared endeavor, and lateral relationship in our evaluation. For instance, in the final survey of treatment school headteachers, compared to comparison schools, they had higher agreement to the statements:

• All school leaders in our partnership had an equal level of status (89 vs 75%)

• There has been a positive impact on the ability of our school’s leaders to improve partner schools (78 vs 61%)

In one group interview of the headteachers nominated to be partnership leads, one comment particularly confirmed the sense of collective leadership, and there seemed wide agreement to this in other interviews:

‘So just setting that up at the beginning, the shared joint values, everyone knowing what we were trying to achieve and going into the reviews with our eyes open completely, getting to the point where you are just developing and enabling a school team to come up with its own solutions has been phenomenal at lots of different levels. It really has created the opportunities for genuine culture and practice for self-improvement’ (Headteacher/partnership lead).

This article drew on Duchek’s (2020) organizational capability-based framework as a theoretical lens to analyze a sub-set of data gained from a sample of 422 primary schools that took part in SPP and their comparisons.

Overall, there is strong support from our data on the potential for SPP to build OR through developing its constitutive capabilities. More precisely, knowledge building occurred mainly through training, the review process, professional dialogue, learning from each other, as well as receiving and giving feedback. While the evaluation data provides support for perceived leaders’ increased ownership and engagement in improvement, our study was necessarily limited in that we did not systematically observe or survey teachers to find out the extent to which they implemented new approaches. A complicating factor within our results is that many clusters were working together, irrespective of their SPP work. This adds a layer of complexity in that it is not always simple to say which resilience findings were the effect of the program, and which were the result of their existing and ongoing collaborative work. There is strong support from school leaders that SPP did add structure and rigor to their work and that levels of trust and knowledge exchange improved. Some of these findings were present in our matched schools, albeit we do not know how many of these schools were involved in partnerships that specifically engaged in peer review. It is also the case that many schools were involved in multiple partnerships. The relationship between peer review practices and other networked activity, formal and informal, remains an interesting area for future research.

Regarding resource availability, despite SPP schools stressed ongoing challenges to school improvement efforts derived from the government’s academisation process, they used SPP as a scaffold to build improvised strategies to access and mobilize shared human and physical resources. However, as one of the principal reasons for withdrawing from the SPP was given lack of staffing and time capacity to participate, it is important to recognize that SPP itself challenges capacity and resources, as it demanded significant time of school leaders, teachers and middle leaders. The need for a supportive infrastructure to provide training and coordination of the network, is also highlighted as a key pillar of the program. While SPP’s states as their aim to eventually ‘do themselves out of a job’, it is not clear that this would lead to sustainability ‘SPP-like’ processes in the long run. Closely linked with resource availability, social resources were built in the SPP through social capital, sharing of knowledge, enhancing a shared vision and trust. Finally, SPP promoted lateral power dynamics driven by professional learning and accountability. The notion of peer review is seen as a shared enquiry rather than a top-down evaluation, promoting collective responsibility for change and leadership across schools.

Our work also adds nuance to Duchek (2020) capability-based framework for OR, particularly within the school sphere. For one, the CBC literature has been generally used to identify singular exogenous threats to performance (e.g., Kopp and Pesti, 2022), instead we looked at these as a conglomeration of associated external challenges that came together to form significant challenges to the schools. Schools used SPP to identify specific areas of focus and choose their own improvement aims; part of the issue was to conceptualize the problem itself, making these examples of ‘wicked’ problems (Rittel and Webber, 1973). As such, Vogus and Sutcliffe’s idea of OR being about the ‘maintenance of positive adjustment under challenging conditions’ (Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007, p. 3418), and the concept of renewal over time through innovation (Reinmoeller and van Baardwijk, 2005) are more apposite in our examples. Although we added research questions in relation to COVID, these were as much about how SPP adapted in response to this, as it was about how SPP helped participant organizations to anticipate, cope and adapt. Other factors such as student deprivation are clearly not ‘unexpected’ threats. Factors contributing to these challenging conditions, such as student deprivation, changes to the external inspectorate framework, the COVID pandemic, the effects of the academisation program and local resourcing constraints form part of the accumulated exogenous variables that threatened OR.

Furthermore, given that most of the literature in OR refers to the ‘business’ sector generally, it is a moot point to what extent the same pressures apply within a public schooling system. For instance, while singular external exogenous threats may be a serious threat to the business model of many companies, for instance the entrance of a new technology or a competitor, with schools it is less clear that this would provide an existential threat. While schools that are slipping in performance may be closed and transformed into a different school with a new senior leadership team, some remain stuck at levels below the required standard for more than a decade (Munoz-Chereau et al., 2022). Thus, for schools, the ongoing monitoring and self-evaluation adds continual accretions of learning that may increase the probability that they can meet ever changing configurations of threats to performance. There is a broader debate too, about what constitutes ‘performance’ in schools. In our original evaluation design, the measure of this was supposed to be numeracy and literacy outcomes in national tests, which were abandoned during COVID, so we cannot know this impact. Instead, we have rich data about processes which will allow in future research for hypotheses to be stated about intermediate variables that underpin schools’ efforts to meet their self-identified, self-stated aims.

One of the biggest challenges for the SPP model was the turnover of key staff in schools, as mentioned in our survey and interviews. Although we did not measure this precisely, we know from the literature in England that teacher attrition has been on the increase over the last 10 years (McLean et al., 2023) and so the concern would be about the loss of a significant amount of time invested in the training for SPP. However, attrition, where teachers leave the profession – is different to turnover – where teachers move from school to school. Recent data suggests that turnover, as indicated by teacher vacancies is higher in the year up to February 2023 than it was prior to the pandemic (McLean et al., 2023). There are a range of drawbacks – and some possible benefits to high turnover rates in schools (see Menzies, 2023 for a full discussion). In the case of this program, new staff will have needed training in reviewing and the IC roles. However, it is also worth noting that this knowledge moves with the staff to a new school and this, in a system where our data shows a significant density and normality of peer review practice in schools. Hence, SPP (and similar programs), through its perceived strong leadership development outcomes, may work beyond the confines of individual schools or clusters, increasing ‘system resilience’. By strengthening evaluation and professional accountability, such programs can be seen as a welcome feature of a maturing self-improving school system (Matthews and Ehren, 2017).

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by IOE, UCL Faculty of Education and Society (University College London). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

DG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BMC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors declare that this study received funding from Education Endowment Foundation. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^In England the term headteacher equates to ‘Principal’.

2. ^We compared responses to individual Likert scale items using a Classical Student’s t-test (p < 0.05). Percentage agreement combines strongly agree and agree, and disagreement combines strongly disagree and disagree, unless stated.

Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL) (2010) Press release – Annual Conference March 2010: over a quarter of education staff have dealt with physical violence by pupils, London, ATL

Ball, S. J. (2016). Neoliberal education? Confronting the slouching beast. Policy Fut Educat 14, 1046–1059. doi: 10.1177/1478210316664259

Brown, C., and Shay, M. (2021). From resilience to wellbeing: Identity‐building as an alternative framework for schools’ role in promoting children’s mental health. Review of Edu. 9, 599–634.

Day, D. V. (Ed.). (2014). The Oxford handbook of leadership and organizations. Oxford: Oxford Library of Psychology.

Day, C., Gu, Q., and Sammons, P. (2016). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: how successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educ. Adm. Q. 52, 221–258. doi: 10.1177/0013161X15616863

Day, C., and Gurr, D. (Eds.). (2013). Leading schools successfully: stories from the field. London Routledge.

Day, C., Sammons, P., and Gorgen, K. (2020). Successful school leadership. Reading, UK Education development trust.

Day, C., Sammons, P., Hopkins, D., Harris, A., Leithwood, K., Gu, Q., et al. (2009). The impact of school leadership on pupil outcomes. Final report National College for School Leadership. Available at: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/49786164/The_Impact_of_School_Leadership_on_Pupil20161022-20085-uqf86y-libre.pdf?1477170971=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DThe_Impact_of_School_Leadership_on_Pupil.pdf&Expires=1703770331&Signature=S4GjXD9Qibv3cZ1rTXrw3hd3-vOOF6Y4OorrIJni5Nx~bFX1oyePq3XkbI3QoYUP2Y9VRrdM1uNeMFtOk7u37z4RcdZvv6FjavrpAmJjCAnB66jnl8syhz3HZ0~1H6234c79wzL4Wqsvm0W0sqFBTJEmq~kd7BnuGPPjPX5kP1tLIZIpMqpNOnGs9y70reAXpflhFkJ5at-oazAIx8slkb6OhBvVEQF6-nDXhVdtL4Dcs22FhlEn40fVcIoZ~6ncsUWdHGyoSLFScatvjtKv~duK6g4NrwuP82xbaTaVWhxWzBFlkL3zW~~Y4XXTVWUOGGeGVJTXK9kJcObLDhvafw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA (Accessed December 28, 2023).

Duchek, S. (2020). Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Bus. Res. 13, 215–246. doi: 10.1007/s40685-019-0085-7

Eells, R. J. (2011). Meta-analysis of the relationship between collective teacher efficacy and student achievement Doctoral dissertation Loyola University Chicago.

Ehren, M. C., Gustafsson, J. E., Altrichter, H., Skedsmo, G., Kemethofer, D., and Huber, S. G. (2015). Comparing effects and side effects of different school inspection systems across Europe. Comp. Educ. 51, 375–400. doi: 10.1080/03050068.2015.1045769

Gilbert, C. (2017). Optimism of the will: the development of local area-based education partnerships. A think-piece. LCLL Publications. Available at: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10065147/14/Gilbert%20IOE%20thinkpiece%20-%20Version%20September%202019.pdf (Accessed October 29, 2023).

Godfrey, D. (Ed.). (2020). School Peer Review for Educational Improvement and Accountability: Theory, Practice and Policy Implications. Cham: Springer Nature.

Godfrey, D., Anders, J., Stoll, L., Greany, T., Munoz Chereau, R., and McGinity, R. (2023). The Schools Partnership Programme. Evaluation Report. Education Development Trust.

Greany, T. (2020). “Self-policing or self-improving? Analysing peer reviews between schools in England through the lens of isomorphism” in School peer review for educational improvement and accountability: Theory, practice and policy implications. ed. Godfrey (Cham: Springer), 71–94.

Greany, T., and Higham, R. (2018). Hierarchy, markets and networks: analysing the ‘self-improving school-led system’ agenda in England and the implications for schools. London: IOE Press.

Gu, Q. (2018). (Re) conceptualising teacher resilience: a social-ecological approach to understanding teachers’ professional worlds. M. Wosnitza, F. Peixoto, S. Beltman, and C. F. Mansfield Resilience in education: concepts, contexts and connections, 13–33 Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Gu, Q., and Day, C. (2007). Teachers’ resilience: a necessary condition for effectiveness. Teach. Teach. Educ. 23, 1302–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.006

Gu, Q., and Day, C. (2013). Challenges to teacher resilience: conditions count. Br. Educ. Res. J. 39, 22–44. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2011.623152

Hargreaves, D. H. (2010). Creating a self-improving school system. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7e48b2ed915d74e33f13e6/creating-a-self-improving-school-system.pdf (Accessed December 28, 2023).

Hattie, J. (2003). Teachers make a difference, what is the research evidence? 1997–2008 ACER research conference archive. Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). Melbourne, Australia Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER)

Hirsh, Å., Liljenberg, M., Jahnke, A., and Karlsson Pérez, Å. (2023). Far from the generalised norm: Recognising the interplay between contextual particularities and principals’ leadership in schools in low-socio-economic status communities. Educat. Manag. Administr. Leader. doi: 10.1177/17411432231187349

Hofer, S. I., Holzberger, D., and Reiss, K. (2020). Evaluating school inspection effectiveness: a systematic research synthesis on 30 years of international research. Stud. Educ. Eval. 65:100864. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100864

Hutchinson, J. (2016). School inspection in England: Is there room to improve? Education policy Institute.

Kopp, E., and Pesti, C. (2022). Organisational learning and resilience in Hungarian schools during COVID-19 distance education – study of two cases. Eur. J. Teach. Educ., 1–20. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2022.2154205

Kotliarenco, M. A., Cáceres, I., and Fontencilla, M. (1997). Estado de Arte en Resiliencia. Chile: Organización Mundial de la Salud, Fundación Kellogg y CEANIM.

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., and Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leader. Manag. 40, 5–22. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2019.1596077

Matthews, P., and Ehren, M. (2017). Accountability and improvement in self-improving school systems. School Leader. Educat. Syst. Reform. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. 44–55.

McLean, D, Worth, J, and Faulkner-Ellis, H. (2023) Teacher labour market in England annual report 2023. Available at: https://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/teacher-labour-market-in-england-annual-report-2023/ (Accessed October 29, 2023)

Menzies, L. (2023). Continuity and churn: understanding and responding to the impact of teacher turnover. Lond. Rev. Educ. 21. doi: 10.14324/LRE.21.1.20

Munoz-Chereau, B., Hutchinson, J., and Ehren, M. (2022). ‘Stuck’ schools: Can below good Ofsted inspections prevent sustainable improvement? London: UCL.

NFER (2023) Teacher labour market in England. Annual report 2023. Available at: https://www.nfer.ac.uk/media/3jrpvnet/teacher_labour_market_in_england_annual_report_2023.pdf

OECD (2013) School evaluation: From compliancy to quality. In Synergies for better learning: An international perspective on evaluation and assessment, 383–485. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264190658-10-en

Olmo-Extremera, M., Townsend, A., and Domingo Segovia, J. (2022). Resilient leadership in principals: case studies of challenged schools in Spain. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ., 1–20. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2022.2052758

Perryman, J., and Calvert, G. (2020). What motivates people to teach, and why do they leave? Accountability, performativity and teacher retention. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 68, 3–23. doi: 10.1080/00071005.2019.1589417

Pinto, T. M., Laurence, P. G., Macedo, C. R., and Macedo, E. C. (2021). Resilience programs for children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 12:754115. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.754115

Reinmoeller, P., and van Baardwijk, N. (2005). The link between diversity and resilience. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 46, 61–65.

Rittel, H. W., and Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy. Sci. 4, 155–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01405730

Rockoff, J. E. (2004). The impact of individual teachers on student achievement: evidence from panel data. Am. Econ. Rev. 94, 247–252. doi: 10.1257/0002828041302244

Sebba, J., Kent, P., and Tregenza, J. (2012). Joint practice development (JPD): What does the evidence suggest are effective approaches?. Nottingham, England: National College for School Leadership.

Sutcliffe, K. M., and Vogus, T. J. (2003). “Organizing for resilience” in Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline. eds. K. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, and R. E. Quinn (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers)

Keywords: school peer review, school improvement partnerships, organizational resilience, school leadership, professional accountability

Citation: Godfrey D and Munoz-Chereau B (2024) School improvement and peer learning partnerships: building organizational resilience in primary schools in England. Front. Educ. 8:1339173. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1339173

Received: 15 November 2023; Accepted: 20 December 2023;

Published: 16 January 2024.

Edited by:

Coby Meyers, University of Virginia, United StatesReviewed by:

Eila Burns, JAMK University of Applied Sciences, FinlandCopyright © 2024 Godfrey and Munoz-Chereau. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David Godfrey, RGF2aWQuZ29kZnJleUB1Y2wuYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.