94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 12 January 2024

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1338321

Introduction: Ethics and professionalism in the health professions reflect how health professionals behave during practice, based on their professional values and attitudes. Health professions education institutions have implemented various strategies for teaching ethics and professionalism, including interprofessional education. The aim of the study was to evaluate the perception of undergraduate health professions students about the outcomes of an online interprofessional course in ethics and professionalism as well as their perception of interprofessional education and the importance of ethics and professionalism after taking the course.

Methods: This is a descriptive cross-sectional study that targeted medical, dentistry, and pharmacy students. A researcher-made 31-item questionnaire was used. The questionnaire was tested for face, content, and construct validity. Reliability of the questionnaire was estimated by Cronbach alpha test. Descriptive statistics were used. T-test was performed to compare the results of male and female students and ANOVA was performed to compare the results of medical, dentistry, and pharmacy students. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results: Factor analysis of the questionnaire yielded three factors, namely course evaluation, perception of interprofessional education, and importance of ethics and professionalism in health professions education. The study participants expressed positive perceptions of all aspects of the course. They reported positive perceptions of interprofessional education, highlighting its benefits in enhancing understanding, teamwork skills, and respect for other healthcare professionals. The findings reveal some program-related differences in participants’ responses, where medical students showed higher ratings of all aspects of the course, interprofessional education and importance of ethics and professionalism.

Conclusion: Students of the three programs showed positive perceptions of the online IPE course on ethics and professionalism as well as the benefits of IPE and the importance of ethics and professionalism. This highlights the effectiveness of the course in addressing such important aspects of health professions education.

Health professionals are confronted with complex ethical challenges during practice, and they are constantly expected to demonstrate professional behavior by upholding ethical standards, displaying empathy, and maintaining effective communication skills (Bulk et al., 2019; Desai and Kapadia, 2022). Therefore, medical ethics and professionalism are fundamental pillars in the education and practice of health professionals. Literature on the education of health professionals highlighted the importance of teaching and assessment of the principles and concepts of medical ethics and professionalism in undergraduate curricula (Atwa et al., 2016; Mahajan et al., 2016; Cellucci, 2022).

Medical ethics is concerned with the morality of medical interventions as well as a reflection of the way health professionals should behave as providers of health care services. The four ethical principles, which are autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and justice are the cornerstone of excellent clinical practice. Health care practitioners can make difficult decisions related to patient care through applying these principles to each encountered clinical case (Panza and Potthast, 2010). Moreover, when treating a patient, the healthcare team should make sure they offer the most suitable care for the patient that is compatible with the patient’s values, preference, and religious beliefs (Atwa et al., 2016).

Professionalism in health care is the relationship that is built on trust between the healthcare professionals and their community, focusing mainly on patients’ interest and adherence to the standards for competency and skills. It is about thinking, behaving, and feeling like a professional, as well as taking responsibility for one’s own personal and professional development (Salih et al., 2019, Bhardwaj, 2022; Cao et al., 2023). Professionalism is one of the main competency domains in the different competency frameworks for medical practice, including the Accreditation of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) framework (Swing, 2007), the Canadian Medical Education Directives (CanMEDS) (Frank and Danoff, 2007), and the Saudi Medical Education Directives (SaudiMEDs) (Zaini et al., 2011; Tekian and Al Ahwal, 2015). Professionalism should be promoted and disseminated as early as possible during undergraduate education (Hilton and Slotnick, 2005). Health Professions educators argue that formal and explicit inclusion of the principles of professionalism in the curriculum is the only way that professional behavior can be improved (O'sullivan et al., 2012).

To ensure that undergraduate health professions students are well-prepared in these critical areas (ethics and professionalism), educational institutions have implemented various strategies, including the integration of interprofessional education (IPE) initiatives (Cino et al., 2018; Naidoo et al., 2020; Seidlein et al., 2022). In IPE, students from two or more health professions are brought together during all or part of their training to learn about, from, and with each other which leads to the creation of a shared understanding and synergy (Yan et al., 2007; World Health Organization, 2010). Interprofessional education aims to equip learners with the knowledge and skills they need to work effectively as part of a health care team providing patient-centered health care (Mohammed et al., 2021). Evidence from literature indicates that IPE enables effective collaborative practice which in turn enhances the quality of health-services delivery, strengthens health systems, and improves health outcomes (Alghamdi and Breitbach, 2023).

IPE is an uncommon educational strategy in the health professions institutions in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, and student readiness for it is understudied (El-Awaisi et al., 2016). This infrequent use of IPE suggests a gap in the integration of this collaborative approach, which could potentially hinder the development of students’ interprofessional skills (Zaher et al., 2022). Furthermore, literature shows conflicting views on the teaching and learning approaches to IPE. Therefore, the body of literature can still receive input from studies about IPE in the MENA context (Sulaiman et al., 2021). As regards students’ perception of IPE in our context, a few studies have reported that students from different health professions showed positive attitude toward learning together in an interprofessional contexts (El Bakry et al., 2018; Sulaiman et al., 2021). A few other studies had assessed students’ satisfaction and self-perceived competencies with courses on ethics and professionalism (Aldughaither et al., 2012; Salih et al., 2019) and reported positive perception toward such courses by the students who agreed that their knowledge and competencies in those two important topics had improved after the courses, especially when they study with students from other health professions.

Ibn Sina National College for Medical Studies (ISNC) in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia has recently introduced a core course on ethics and professionalism for undergraduate medical, dentistry and pharmacy students. The main goal of this course is to provide future medical, dental, and pharmacy graduates with the foundational knowledge to identify, analyze, and manage the most common ethical issues and dilemmas and to practice in a professional manner. The course is taught in an interprofessional context and was initiated as an online course due to the lock-down in 2020 and the suspension of face-to-face education because of the COVID-19 crisis. Research examining the effectiveness of online courses in healthcare education has shown promising results (Alblihed et al., 2021; Atwa et al., 2022). Online learning platforms provide flexibility and accessibility, allowing students to engage with course materials at their own pace and convenience. Online courses also promote active learning through interactive modules, case studies, and virtual simulations, which can enhance students’ understanding of complex ethical scenarios (Francisco, 2020; Hasan and Khan, 2020). Moreover, online platforms facilitate interprofessional collaboration by overcoming geographical barriers and enabling students from various health professions to engage in discussions and shared learning experiences (Abdelaziz et al., 2021, Almoghirah et al., 2023).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the different aspects of this online course on ethics and professionalism from the students’ perspectives, in addition to exploring their viewpoints regarding the importance of learning ethics and professionalism in the undergraduate curriculum as well as their attitude toward interprofessional learning with other healthcare professions.

This is a descriptive, cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study that was conducted to evaluate, from the viewpoints of students, a course on “ethics and professionalism” that was taught through the interprofessional learning strategy to the 4th year medical, dental, and pharmacy students at ISNC in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The course had both theoretical and practical components that were taught through interactive lectures, case-based learning sessions, and student-led webinars, and discussion forums. Students from the three programs (Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmacy) learned with and from each other in an integrated interprofessional environment. The course was implemented online during the second semester of the academic year 2020–2021. Implementation of the course was assisted by a learning management system called DigiVal DigiClass® integrating with Microsoft Teams® as a videoconferencing platform. DigiClass® was used to host the course materials and the offline discussion forums. Microsoft Teams® was used for live interactive lectures, case-based learning sessions, and student-led webinars. Teaching/learning sessions happened in small groups of 10–12 male and female medical, dental, and pharmacy students with an assigned facilitator from the faculty members who participated in the delivery of the course.

This study employed comprehensive sampling. The target population consisted of all fourth year medical (190), dental (27), and pharmacy (33) students who took the course during the academic year 2020–2021.

Data was collected through a self-administered online questionnaire that was developed and revised by all the authors after extensive review of relevant literature and similar studies.

The questionnaire consisted of 31 items that addressed the different aspects of the course as well as the interprofessional learning strategy and the importance of ethics and professionalism for health professions students. The questionnaire employed a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 5 (Strongly Agree) to 1 (Strongly Disagree). In addition, the questionnaire form contained items that explored demographic data of the respondents (gender and study program) as well as a brief introduction about the aim, importance of the study and informed consent for participation in the study.

As the questionnaire was constructed by the authors, we conducted reliability and validity studies to explore its suitability for the study. The questionnaire was tested for reliability (internal consistency) through Cronbach’s alpha test. Three types of validity were established for the questionnaire: content validity, face validity, and construct validity.

• Content validity was done through review of the questionnaire by four medical education experts. Based on expert opinions, the questionnaire was edited. This included modifying item #2 from “The course content was useful for my learning after graduation” to “The course content was relevant and useful for my future career” and adding item #23 (Interprofessional education can be used to teach other subjects as well). Other items of the questionnaire were reported to be clear, contextual, and measuring the intended construct.

• Face validity was evaluated through piloting the questionnaire with ten different professions students and the results were not included in the results of the study. Based on those students’ responses, a few modifications were made in some of the questionnaire’s items to remove any vagueness and ensure they are clear in meaning.

• Construct validity was established through Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA).

The questionnaire form was converted into a Google Form® and disseminated to the students through different social media platforms, such as email and WhatsApp®, once the course had finished. Clear and concise instructions for completing the questionnaire accurately were given to the students at the beginning of the questionnaire.

Data was analyzed by using the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 25. Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, minimum, and maximum) were used. Comparing the means of two groups was done using independent samples t-test. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparing the means of more than two groups. A p < 0.05 was considered as the cut-off point for statistical significance.

Principal component analysis with Varimax rotation was used in EFA. The number of factors extracted and used was based on the Kaiser criterion, which considers factors with an eigenvalue >1 as common factors (Kaiser, 1960), the Scree test criterion (the Cattell criterion) to identify the inflection point indicated by the Scree plot (Cattell, 1966), and the cumulative percentage of variance extracted (Pett et al., 2003). Factor solutions were then analyzed based on the following interpretability criteria (Lee and Hooley, 2005):

• An accepted factor must contain at least three items with substantial loadings (a loading of 0.30 as the cutoff).

• Items that load on the same factor must have a common conceptual meaning.

• An item that loads on a different factor measures a different construct.

This study aimed at evaluating a newly introduced interprofessional course on ethics and professionalism for health professions students from the viewpoints of those students who studied the course. Data of this study was collected through an online questionnaire prepared by the authors.

The results of this study are presented under two sections: reliability and validity studies of the questionnaire and analysis of the responses of study participants.

The reliability (internal consistency) of the questionnaire was assured through Cronbach’s alpha test. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.931 was detected, which indicates a high level of internal consistency reliability for the questionnaire. Internal consistencies of individual subscales were 0.925, 0.872, and 0.901 for “Course evaluation,” “Perception of interprofessional education,” and “Importance of ethics and professionalism for health care professionals” respectively.

This was done through EFA (Table 1 and Figure 1). The following steps were taken:

• Checking data adequacy for factor analysis. We collected 207 responses. The amount of data was found adequate for factor analysis (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) was 0.88 and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity χ2 (465, N = 207) =4627.57, p = 0.00). This output indicated the adequacy and appropriateness of collected data for factor analysis.

• Factor extraction and rotation. Results revealed that the 31 items of the questionnaire could be grouped under three factors with Eigenvalues >1. Those three factors together accounted for 67.83% of the data variance. Factor rotation revealed that none of the 31 items was to be removed from the analysis as all factors had three or more items, no cross-loading of any items was detected, and all items had item loading of >0.30 on relevant factors.

After EFA, the questionnaire consisted of the original 31 items grouped under three factors. Factors were then named according to the heaviness of loading of relevant items on them as well as according to the idea behind the items collectively as follows:

• Factor 1 explained 41.09% of the variance in responses, with an eigenvalue of 11.24. Sixteen items loaded on this factor, with values between 0.465 and 0.863. This factor has been named “Course Evaluation.”

• Factor 2 explained 17.70% of the variance in responses, with an eigenvalue of 4.41. Eight items loaded on this factor, with values between 0.639 and 0.813. This factor has been named “Perception of Interprofessional Education.”

• Factor 3 explained 9.04% of the variance in responses, with an eigenvalue of 1.74. Seven items loaded on this factor, with values between 0.480 and 0.872. This factor has been named “Importance of Ethics and Professionalism for Health Care Professionals.”

The response rates were 86.3% from medical students (n = 164), 75.8% from pharmacy students (n = 25), and 66.7% from dental students (n = 18). In total, 207 students responded to the questionnaire, 68.1% of them were females and 31.9% were males. Medicine program participants constituted 79.2%, pharmacy students were 12.1%, while dentistry students were 8.7% (Table 2).

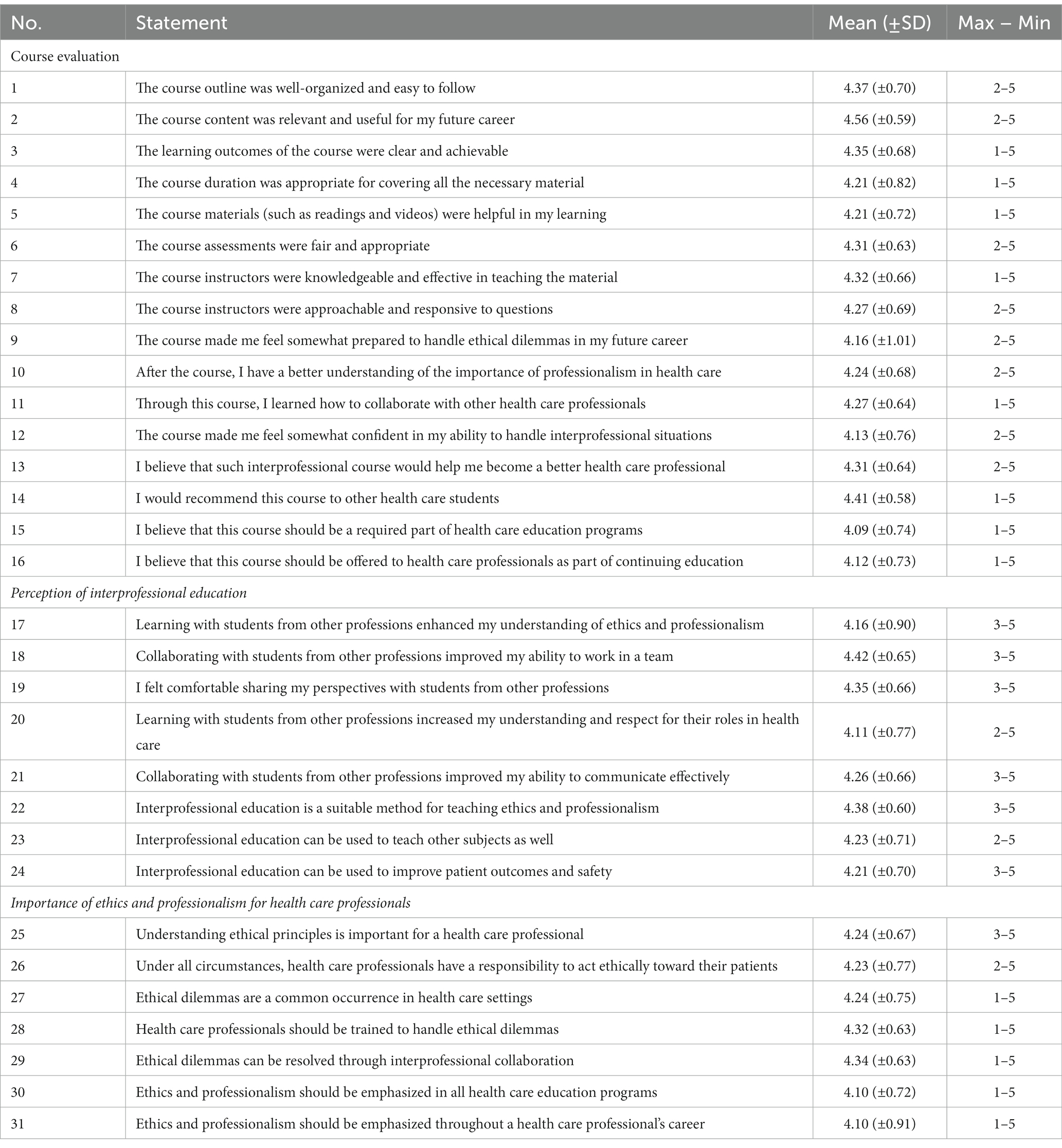

The results of the study showed that the participants expressed positive evaluations of the course, with mean scores above 4 for all questionnaire statements. They also recognized the importance of professionalism in healthcare and believed that the course contributed to their understanding and development in this area. Participants reported positive perceptions of interprofessional education, highlighting its benefits in enhancing understanding, teamwork skills, and respect for other healthcare professionals. Additionally, they emphasized the importance of ethical principles, ethical training for healthcare professionals, and the role of interprofessional collaboration in resolving ethical dilemmas (Table 3).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of participants’ responses to the questionnaire statements (N = 207).

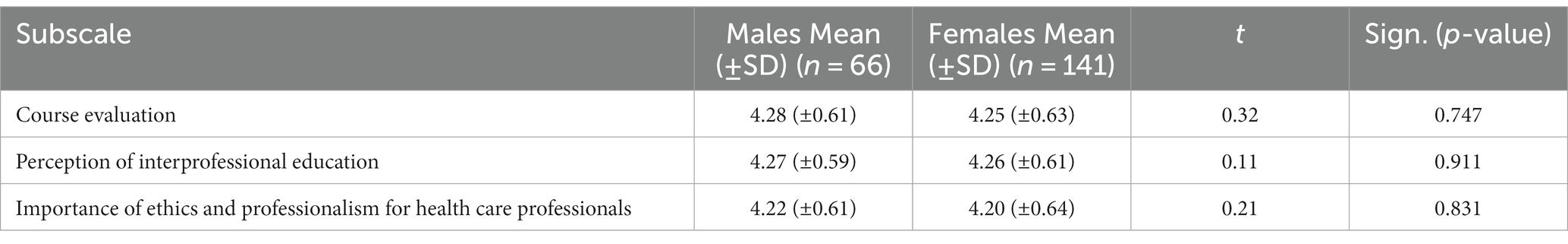

Table 4 presents the results of an independent samples t-test comparing the responses of male and female participants. Both male and female participants provided positive evaluations of the course, recognized the benefits of interprofessional education, and emphasized the importance of ethics and professionalism for health care professionals. No statistically significant differences were found between either gender in any of the questionnaire subscales.

Table 4. Comparison between the responses of male and female students to the questionnaire (independent samples t-test).

The findings in Table 5 reveal program-related differences in participants’ responses. Participants from the medicine program generally provided higher ratings for course evaluation, perception of interprofessional education, and the importance placed on ethics and professionalism for healthcare professionals than the participants from the dentistry and pharmacy programs. The differences among the responses of the participants of the three programs regarding the questionnaire subscales were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

The results of this study provide understanding of students’ experience of an online interprofessional course on ethics and professionalism for health professions students at a private medical college in Saudi Arabia. The course was an initiative to establish IPE at ISNC since it is a novel concept in the Middle East and North Africa region (Zaher et al., 2022). The students reported their experience with the course from three aspects, which are perception of the course, perception of interprofessional education, and the perceived importance of ethics and professionalism to their future practice. Overall, the participants expressed positive evaluations of the course, highlighting its organization, content relevance, instructor effectiveness, and contributions to their understanding and development of professionalism and appreciation of IPE. These findings are consistent with previous research on the effectiveness of online IPE courses for health professions students (Akerson et al., 2013; Tilley et al., 2021).

Reasons that might have led to students’ satisfaction with the course include the diversity in teaching and learning methods and the use of small group learning, since small group learning is reported to benefit IPE through creating a community-like environment that fosters social interactions (Burgess et al., 2017). Furthermore, the role of facilitators as IPE role models was highlighted and considered as beneficial for promoting trust and acceptance of interprofessional practice (van Diggele et al., 2020).

As a result of the IPE course, the students reported improvement in their teamwork abilities, understanding of ethics and professionalism, enhanced communication skills, and increased receptiveness of the interprofessional context. Similar studies reported more benefits than challenges related to IPE, with emphasis on ability to learn from each other and the understanding other students’ professional practice (Mahler et al., 2018) and recommending IPE courses in undergraduate medical education to enable students to function effectively as part of the healthcare team upon graduation (Tsakitzidis et al., 2015).

Moreover, the students showed positive perceptions of the IPE as a learning strategy for teaching ethics and professionalism and even agreed that it should be used for teaching other subjects as well. This may be because IPE, highlighting the process and benefits of interprofessional teamwork and collaborative practice that constitute the environment in which they will work after graduation. Several previous studies have highlighted the importance of IPE and the perception of undergraduate health professions students of it (Darlow et al., 2015; Fallatah et al., 2015; Anderson, 2016; Cino et al., 2018; Berger-Estilita et al., 2020; Atwa et al., 2023).

Regarding the perceived importance of ethics and professionalism, the students showed positive perceptions as well. This might be attributed to the vital role of ethics and professionalism in their professional career as health care professionals. The importance of teaching ethics and professionalism to undergraduate health care students was highlighted in several previous research studies (Agich, 1980; Blumenthal, 1994; Garman et al., 2006; Cassidy and Blessing, 2007; Slomka et al., 2008; Atwa et al., 2016; Mahajan et al., 2016; Cellucci, 2022).

The results indicate that the course was equally well perceived by both male and female participants, suggesting that gender does not play any significant role in shaping participants’ perceptions and evaluations of the IPE course, their views on interprofessional education, or their recognition of the importance of ethics and professionalism in health care. This finding is congruent with previous studies by Hylin et al. (2007) and Reynolds (2003) who found no substantial differences between males and females in perception of an IPE in different courses. However, previous studies by Wilhelmsson et al. (2011) and Sulaiman et al. (2021) reported that female students in general viewed interprofessional learning more positively than males and were more open-minded regarding co-operation with other professions.

The nature of the program, whether medicine, dentistry, or pharmacy, seemed to play a role in shaping participants’ responses, as medical students provided more positive ratings for course evaluation, perception of IPE, and perception of the importance of ethics and professionalism for health care professionals as compared to dentistry and pharmacy students. In contrast to our findings, Hylin et al. (2007) found no profession-related difference in regard to perception of IPE. In relation to these results, specialty was studied in two previous studies that used the readiness for interprofessional learning scale. The first study reported that pharmacy students had significantly higher scores on their readiness for IPE from medicine, dentistry and applied medical sciences colleges (Sulaiman et al., 2021). In the second study, nursing interns were found to have higher readiness to IPE than medical interns (El Bakry et al., 2018). The contrasting findings suggest that the profession-related preferences might depend on the context and the content of the course, as well as the effectiveness of implementing the IPE activities.

The IPE course in the current study was conducted online. The use of technology-enhanced learning has been reported to be increasingly prevalent in the recent years (van Diggele et al., 2020), not only during the time of Covid-19 crisis but also in the post-Covid era, which denotes that undergraduate students should also be trained for contemporary practice (Almoghirah et al., 2023). Online learning in IPE is believed to overcome many of the challenges related to IPE, such as shortage of time, lack of resources, and difficulty in synchronizing timetables (Casimiro et al., 2009; Solomon and King, 2010; Evans et al., 2013, 2017; Abdelaziz et al., 2021, Almoghirah et al., 2023).

The limitations of the study, which can also be considered as areas for future research is that the questionnaire did not tackle the perceived challenges to IPE by students, not all health professions students were included (such as nursing students), and the study measured only one level of evaluation of educational intervention model (Barr et al., 2002). In addition, as this is a descriptive cross-sectional study, other factors that might have accounted for the differences between the students of different programs remained unexamined. Moreover, data collected through the questionnaire might be subjected to response bias, and in-depth qualitative data would have been useful for triangulation of evidence of students’ perceptions.

The positive perception of the online IPE course on ethics and professionalism expressed by the study participants, along with their recognition of the importance of ethics and professionalism and the benefits of interprofessional education, highlight their positive experience of the course and its effectiveness in addressing such important aspects of health professions education. These findings support the integration of similar courses into health professions curricula. By incorporating ethics and professionalism education through IPE, the development of competent and ethical healthcare professionals can be fostered, ultimately improving patient care and patient outcomes.

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the ISNC Research and Ethics Committee (IRRB-05-28022022). All the students were informed about the purpose of the study, and they were given the right to refuse participation without any consequences or harm to them. Ethical conduct was maintained during data collection and throughout the research process. Participation in the study was completely voluntary and the participants’ confidentiality was maintained as the questionnaire was provided anonymously.

HA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AF: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JTB: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LFM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. AA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors are grateful for the students who participated in this research work. We also would like to thank the administration of the college for the support and facilitation of the data collection process.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abdelaziz, A., Mansour, T., Alkhadragy, R., Abdel Nasser, A., and Hasnain, M. (2021). Challenges to interprofessional education: will e-learning be the magical stick? Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 12, 329–336. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S273033

Agich, G. J. (1980). Professionalism and ethics in health care. J. Med. Philos. 5, 186–199. doi: 10.1093/jmp/5.3.186

Akerson, E., Stewart, A., Baldwin, J., Gloeckner, J., Bryson, B., and Cockley, D. (2013). Got ethics? Exploring the value of Interprofessional collaboration through a comparison of discipline-specific codes of ethics. MedEdPORTAL 9:9331. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9331

Alblihed, M. A., Aly, S. M., Albrakati, A., Eldehn, A. F., Ali, S. A. A., Al-Hazani, T., et al. (2021). The effectiveness of online education in basic medical sciences courses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: cross-sectional study. Sustainability 14:224. doi: 10.3390/su14010224

Aldughaither, S. K., Almazyiad, M. A., Alsultan, S. A., Al Masaud, A. O., Alddakkan, A. R. S., Alyahya, B. M., et al. (2012). Student perspectives on a course on medical ethics in Saudi Arabia. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 7, 113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2012.11.002

Alghamdi, H., and Breitbach, A. (2023). “Governance of Interprofessional education and collaborative practice” in Novel health Interprofessional education and collaborative practice program: Strategy and implementation (Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore)

Almoghirah, H., Illing, J., Nazar, M., and Nazar, H. (2023). A pilot study evaluating the feasibility of assessing undergraduate pharmacy and medical students interprofessional collaboration during an online interprofessional education intervention about hospital discharge. BMC Med. Educ. 23:589. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04557-x

Anderson, E. S. (2016). Evaluating interprofessional education: an important step to improving practice and influencing policy. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 11, 571–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2016.08.012

Atwa, H., Abouzeid, E., Hassan, N., and Abdel Nasser, A. (2023). Readiness for Interprofessional learning among students of four undergraduate health professions education programs. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 14, 215–223. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S402730

Atwa, H., Ghaly, M., and Hosny, S. (2016). Teaching and assessment of professionalism: a comparative study between two medical schools. Educ. Med. J. 8, 35–47. doi: 10.5959/eimj.v8i3.441

Atwa, H., Shehata, M. H., Al-Ansari, A., Kumar, A., Jaradat, A., Ahmed, J., et al. (2022). Online, face-to-face, or blended learning? Faculty and medical students' perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-method study. Front. Med. 9:791352. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.791352

Barr, H., Freeth, D., Hammick, M., Koppel, I., and Reeves, S. (2002). A critical review of evaluations of interprofessional education. United Kingdom: Higher Education Academy, Health Sciences and Practice Network.

Berger-Estilita, J., Chiang, H., Stricker, D., Fuchs, A., Greif, R., and McAleer, S. (2020). Attitudes of medical students towards interprofessional education: a mixed-methods study. PLoS One 15:e0240835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240835

Bhardwaj, A. (2022). Medical professionalism in the provision of clinical Care in Healthcare Organizations. J. Healthcare Lead. 14, 183–189. doi: 10.2147/JHL.S383069

Blumenthal, D. (1994). The vital role of professionalism in health care reform. Health Aff. 13, 252–256. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.13.1.252

Bulk, L. Y., Drynan, D., Murphy, S., Gerber, P., Bezati, R., Trivett, S., et al. (2019). Patient perspectives: four pillars of professionalism. Pat. Exp. J. 6, 74–81. doi: 10.35680/2372-0247.1386

Burgess, A., Roberts, C., van Diggele, C., and Mellis, C. (2017). Peer teacher training (PTT) program for health professional students: interprofessional and flipped learning. BMC Med. Educ. 17, 239–213. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1037-6

Cao, H., Song, Y., Wu, Y., Du, Y., He, X., Chen, Y., et al. (2023). What is nursing professionalism? A concept analysis. BMC Nurs. 22:34. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-01161-0

Casimiro, L., MacDonald, C. J., Thompson, T. L., and Stodel, E. J. (2009). Grounding theories of W (e) learn: a framework for online interprofessional education. J. Interprof. Care 23, 390–400. doi: 10.1080/13561820902744098

Cassidy, B., and Blessing, J. D. (2007). Ethics and professionalism: a guide for the physician assistant. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA: FA Davis.

Cattell, R. B. (1966). The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behav. Res. 1, 245–276. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10

Cellucci, L. W. (2022). Ethics and professionalism for healthcare managers. eds. A. J. Cellucci, T. J. Farnsworth, and E. Forrestal (Washington, DC: Association of University Programs in Health Administration).

Cino, K., Austin, R., Casa, C., Nebocat, C., and Spencer, A. (2018). Interprofessional ethics education seminar for undergraduate health science students: a pilot study. J. Interprof. Care 32, 239–241. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2017.1387771

Darlow, B., Coleman, K., McKinlay, E., Donovan, S., Beckingsale, L., Gray, B., et al. (2015). The positive impact of interprofessional education: a controlled trial to evaluate a programme for health professional students. BMC Med. Educ. 15, 98–99. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0385-3

Desai, M. K., and Kapadia, J. D. (2022). Medical professionalism and ethics. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 13, 113–118. doi: 10.1177/0976500X221111448

El Bakry, A. A. N., Farghaly, A., Hany, M., Shehata, A. M., and Hosny, S. (2018). Evaluation of an interprofessional course on leadership and management for medical and nursing pre-registration house officers. Educ. Med. J. 10, 41–52. doi: 10.21315/eimj2018.10.1.6

El-Awaisi, A., Saffouh El Hajj, M., Joseph, S., and Diack, L. (2016). Interprofessional education in the Arabic-speaking Middle East: perspectives of pharmacy academics. J. Interprof. Care 30, 769–776. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2016.1218830

Evans, S., Sonderlund, A., and Tooley, G. (2013). Effectiveness of online interprofessional education in improving students' attitudes and knowledge associated with interprofessional practice. Focus Health Prof. Educ. Multi-Disciplinary J. 14, 12–20.

Evans, S. M., Ward, C., and Reeves, S. (2017). An exploration of teaching presence in online interprofessional education facilitation. Med. Teach. 39, 773–779. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1297531

Fallatah, H. I., Jabbad, R., and Fallatah, H. K. (2015). Interprofessional education as a need: the perception of medical, nursing students and graduates of medical college at King Abdulaziz university. Creat. Educ. 6, 248–254. doi: 10.4236/ce.2015.62023

Francisco, C. (2020). Effectiveness of an online classroom for flexible learning. Int. J. Acad. Multidiscip. Res. 4, 100–107.

Frank, J. R., and Danoff, D. (2007). The CanMEDS initiative: implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med. Teach. 29, 642–647. doi: 10.1080/01421590701746983

Garman, A. N., Evans, R., Krause, M. K., and Anfossi, J. (2006). Professionalism. J. Healthcare Manage 51, 219–222. doi: 10.1097/00115514-200607000-00004

Hasan, N., and Khan, N. H. (2020). Online teaching-learning during covid-19 pandemic: students’ perspective. Online J. Distance Educ. e-Learn. 8, 202–213.

Hilton, S. R., and Slotnick, H. B. (2005). Proto-professionalism: how professionalisation occurs across the continuum of medical education. Med. Educ. 39, 58–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02033.x

Hylin, U., Nyholm, H., Mattiasson, A. C., and Ponzer, S. (2007). Interprofessional training in clinical practice on a training ward for healthcare students: a two-year follow-up. J. Interprof. Care 21, 277–288. doi: 10.1080/13561820601095800

Kaiser, H. F. (1960). The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 20, 141–151. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000116

Lee, N., and Hooley, G. (2005). The evolution of “classical mythology” within marketing measure development. Eur. J. Mark. 39, 365–385. doi: 10.1108/03090560510581827

Mahajan, R., Aruldhas, B. W., Sharma, M., Badyal, D. K., and Singh, T. (2016). Professionalism and ethics: a proposed curriculum for undergraduates. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 6, 157–163. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.186963

Mahler, C., Schwarzbeck, V., Mink, J., and Goetz, K. (2018). Students perception of interprofessional education in the bachelor programme “Interprofessional health care” in Heidelberg, Germany: an exploratory case study. BMC Med. Educ. 18, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1124-3

Mohammed, C. A., Anand, R., and Ummer, V. S. (2021). Interprofessional education (IPE): a framework for introducing teamwork and collaboration in health professions curriculum. Med. J. Armed Forces India 77, S16–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2021.01.012

Naidoo, S., Turner, K. M., and McNeill, D. B. (2020). Ethics and interprofessional education: an exploration across health professions education programs. J. Interprof. Care 34, 829–831. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2019.1696288

O'sullivan, H., Van Mook, W., Fewtrell, R., and Wass, V. (2012). Integrating professionalism into the curriculum: AMEE guide no. 61. Med. Teach. 34, e64–e77. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.655610

Panza, C., and Potthast, A. (2010). Ethics for dummies. Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

Pett, M. A., Lackey, N. R., and Sullivan, J. J. (2003). Making sense of factor analysis: The use of factor analysis for instrument development in health care research. Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Sage.

Reynolds, F. (2003). Initial experiences of interprofessional problem-based learning: a comparison of male and female students' views. J. Interprof. Care 17, 35–44. doi: 10.1080/1356182021000044148

Salih, K. M., Abbas, M., Mohamed, S., and Al-Shahrani, A. M. (2019). Assessment of professionalism among medical students at a regional university in Saudi Arabia. Sudanese J. Paediatr. 19, 140–144. doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1571425730

Seidlein, A. H., Hannich, A., Nowak, A., and Salloch, S. (2022). Interprofessional health-care ethics education for medical and nursing students in Germany: an interprofessional education and practice guide. J. Interprof. Care 36, 144–151. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2021.1879748

Slomka, J., Quill, B., des Vignes-Kendrick, M., and Lloyd, L. E. (2008). Professionalism and ethics in the public health curriculum. Public Health Rep. 123, 27–35. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S205

Solomon, P., and King, S. (2010). Online interprofessional education: perceptions of faculty facilitators. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 24, 51–53. doi: 10.1097/00001416-201010000-00009

Sulaiman, N., Rishmawy, Y., Hussein, A., Saber-Ayad, M., Alzubaidi, H., Al Kawas, S., et al. (2021). A mixed methods approach to determine the climate of interprofessional education among medical and health sciences students. BMC Med. Educ. 21, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02645-4

Swing, S. R. (2007). The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med. Teach. 29, 648–654. doi: 10.1080/01421590701392903

Tekian, A. S., and Al Ahwal, M. S. (2015). Aligning the SaudiMED framework with the National Commission for academic accreditation and assessment domains. Saudi Med. J. 36, 1496–1497. doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.12.12916

Tilley, C. P., Roitman, J., Zafra, K. P., and Brennan, M. (2021). Real-time, simulation-enhanced interprofessional education in the care of older adults with multiple chronic comorbidities: a utilization-focused evaluation. Mhealth 7:3. doi: 10.21037/mhealth-19-216

Tsakitzidis, G., Timmermans, O., Callewaert, N., Truijen, S., Meulemans, H., and Van Royen, P. (2015). Participant evaluation of an education module on interprofessional collaboration for students in healthcare studies. BMC Med. Educ. 15:188. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0477-0

van Diggele, C., Roberts, C., Burgess, A., and Mellis, C. (2020). Interprofessional education: tips for design and implementation. BMC Med. Educ. 20, 455–456. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02286-z

Wilhelmsson, M., Ponzer, S., Dahlgren, L. O., Timpka, T., and Faresjö, T. (2011). Are female students in general and nursing students more ready for teamwork and interprofessional collaboration in healthcare? BMC Med. Educ. 11, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-15

World Health Organization . (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice (No. WHO/HRH/HPN/10.3). Geneva: World Health Organization Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/66399/retrieve (accessed: 13 November 2023)

Yan, J., Gilbert, J. H., and Hoffman, S. J. (2007). World Health Organization study group on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J. Interprof. Care 21, 587–589. doi: 10.1080/13561820701775830

Zaher, S., Otaki, F., Zary, N., Al Marzouqi, A., and Radhakrishnan, R. (2022). Effect of introducing interprofessional education concepts on students of various healthcare disciplines: a pre-post study in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Med. Educ. 22, 517–514. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03571-9

Keywords: ethics, professionalism, interprofessional education, evaluation, online course

Citation: Atwa H, Farghaly A, Badawi JT, Malik LF and Abdelnasser A (2024) Evaluation of an online interprofessional course on ethics and professionalism: experience of medical, dental, and pharmacy students. Front. Educ. 8:1338321. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1338321

Received: 14 November 2023; Accepted: 18 December 2023;

Published: 12 January 2024.

Edited by:

Mona Hmoud AlSheikh, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Mohamed Elhassan Abdalla, University of Limerick, IrelandCopyright © 2024 Atwa, Farghaly, Badawi, Malik and Abdelnasser. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hani Atwa, aGFueXNtYUBhZ3UuZWR1LmJo

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.