- 1Faculty of Arts, Design, and Archietecture, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2UNSW Disability Innovation Institute, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3Faculty of Science, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4School of Business, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Neurodivergent students are one of the fastest growing diversity groups in tertiary education. This highlights the need for a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) perspective in course design and delivery. One important component of UDL is student voice, which has been historically lacking, especially for neurodivergent students. In this perspectives article, the authors present a viewpoint on the importance of promoting co-production in course design and delivery between neurodivergent students and instructors and illustrate the concept with examples from the Diversified Project. The “Diversified Group” was established by neurodivergent students and faculty members to address the perceived inadequacy in instructor awareness regarding the varied needs of an expanding neurodiverse student population at the university. The authors provide recommendations for systemic, faculty, school, and instructor-level actions to improve the learning experience for neurodivergent students. Current advances and future directions in promoting co-production in university course design and delivery are provided.

1 Introduction

In the evolving landscape of tertiary education, the significance of creating an inclusive environment for neurodivergent students cannot be understated. Neurodivergence, encompassing a spectrum of cognitive variations such as ADHD, autism, dyslexia, and others, presents both unique challenges and strengths within academic settings. As the global student population becomes increasingly diverse, universities are tasked with the responsibility of ensuring that their pedagogical approaches, resources, and support systems are tailored to meet the varied needs of all students.

Recent literature underscores the pivotal role of accessibility in shaping the academic experiences and outcomes of neurodivergent students (Bunbury, 2020; Cook-Sather, 2020; Kim and Kutscher, 2021). Studies have highlighted the myriad of barriers these students often face, ranging from curriculum design and assessment methods to social integration and mental well-being (Smith et al., 2020). However, while challenges persist, there is a growing recognition of the immense potential and unique perspectives that neurodivergent individuals bring to the academic table. Their distinct cognitive processing styles, often characterized by deep focus, pattern recognition, and innovative thinking, can greatly enrich the academic community (Brown and Green, 2018).

1.1 Neurodivergence and the neurodiversity movement

Neurodiversity encompasses a broad spectrum of cognitive differences, including ADHD, dyslexia, Tourette’s, bipolar disorder, autism, anxiety, and many more. Individuals with these differences, termed as neurodivergent, have unique approaches to tasks and problem-solving, distinct from the neurotypical population. This concept underscores the inherent variations in brain functions (Turner and Smith, 2023).

The rise of the term “neurodiversity” has been accompanied by a movement that challenges the traditional binary view of “good” versus “bad” brains. As Emily Ladau (2021) articulates, the movement promotes the understanding that every brain is unique, moving away from value-based judgments. In this paper, our focus is on fostering an environment that supports neurodivergent individuals, allowing them to thrive authentically. We will not segregate strategies based on specific neurotypes, due to the unique manifestation of traits in each person and the practical reality that we often do not categorize students or scientists by their neurotypes. The strategies presented are general, emphasizing the importance of individualized approaches.

We believe a collaborative approach is the optimal way to make this happen. Even neurodivergent educators or leaders might require guidance in accommodating their students or teams, given the diverse manifestations of neurodivergent traits. It is essential to avoid prying into someone’s neurotype. Instead, when unique needs arise, they should be addressed without bias. The focus should shift from highlighting deficits to recognizing and leveraging individual strengths.

1.2 Universal design for learning

The current study is underpinned by Universal Design for Learning (UDL). UDL is based on cognitive neuroscience research, using what is known about the brain during learning to design environments to support all learners. The three principles of UDL are based on the neurological organization of the brain and include providing students with multiple means of: representation, engagement, and action and expression (CAST, 2018). Up until recently, UDL was mainly used in traditional K-12 educational settings, but higher education institutions have come to realize and appreciate the benefits for students and educators alike, when courses are designed according to the principles of UDL. Cumming and Rose (2021) reviewed the literature supporting UDL and found over 800 articles supporting its theory and practice in higher education. Cumming and Rose (2021) also found that students with and without disabilities appreciated having the affordances of UDL incorporated into their courses.

Integrating the principles of UDL into course design and delivery, offering students choice, and supporting them in their self-regulation, goal setting, and effort and persistence serves to address some of the challenges they face, capitalizing on their strengths, therefore enhancing student equity. Unfortunately, Cumming and Rose (2021) also identified systemic barriers to the implementation of UDL in higher education. While instructors recognized the potential benefits of integrating UDL into their teaching approaches, they often felt that their faculties did not sufficiently value UDL. Moreover, there was a notable absence of support, particularly in terms of training and allotted time for course redesign. These insights highlight the importance of amplifying both student and instructor perspectives when striving for more inclusive university learning. By co-creating course designs, materials, and delivery methods, both students and instructors can actively contribute to equitable learning environments.

1.3 Co-production in higher education

Research has demonstrated that dialogical co-production partnerships can be a powerful way to promote more collaborative and responsive approaches to teaching and learning in higher education (Cook-Sather, 2018; Higgins et al., 2019; Marquis et al., 2019). The term co-creation is sometimes used to encompass the terms co-production and co-design. According to Cook-Sather (2020), co-creation refers to the process of academic staff and students working together to develop and implement teaching and learning practices that are more equitable and inclusive. This involves valuing and incorporating the perspectives and experiences of both staff and students and engaging in ongoing dialogue and reflection to improve teaching and learning outcomes.

The advantages of co-production in higher education courses are many. Participation in an effective pedagogical partnership fosters important affective experiences in relation to all faculty and to fellow students, informs students’ academic engagement in their own classes, and contributes to students’ sense of their evolution as active agents in their own and others’ development (Cook-Sather, 2018). Partnership programs can also foster important affective experiences, inform academic engagement, and contribute to students’ sense of themselves as active agents in their own and others’ development. Co-creation can support the development of staff and student voices by creating a safe and supportive space for dialogue, valuing and incorporating the perspectives and experiences of both groups, and encouraging ongoing reflection and improvement. The study also found that co-creation can lead to more equitable classroom approaches by promoting inclusive teaching and learning practices that are responsive to the needs and experiences of underrepresented and underserved students (Cook-Sather, 2020).

Slates and Cook-Sather (2021) presented a collection of perspectives on successful partnerships in tertiary education. They showcased the contributions of diverse ideas and voices; contributors discussed what successful partnership means to them. These experiential reflections emphasized the importance of shared ownership, decision-making, and mutual benefits in partnerships. They also highlighted the need to challenge norms, push beyond comfort zones, and ask new questions for meaningful partnership. Successful partnerships are seen as ongoing processes that focus on relationships, processes, and community, rather than just outcomes. The contributors discussed how partnerships have played a crucial role in navigating challenges, such as the shift to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In short, co-production can support the development of staff and student voices by creating a safe and supportive space for dialogue, valuing and incorporating the perspectives and experiences of both groups and encouraging ongoing reflection and improvement. This will then lead to more equitable classroom approaches by promoting inclusive teaching and learning practices that are responsive to the needs and experiences of neurodivergent students.

1.4 Challenges

The concerns raised by university teaching staff regarding accommodations for students with disabilities elucidate the feelings of inaccessibility and exclusion experienced by many neurodivergent students. Instructors in Bunbury (2020) study revealed that they faced a lack of training and awareness, a lack of resources, and a lack of clarity around legal requirements. University teaching staff also reported feeling overwhelmed by the complexity of accommodating multiple disabilities and the challenge of balancing the specific needs of students with disabilities against those of the broader student population. Bunbury suggested that these challenges could be overcome by providing staff with more opportunities for professional development, such as workshops and training sessions, more centralized support services and clearer guidelines around legal requirements.

University course instructors are also sometimes resistant to the idea of student-faculty co-creation of teaching approaches, course design, and curricula. According to the results of a literature review conducted by Bovill et al. (2011), staff may be skeptical of the value of student involvement, particularly regarding their own time commitment and the resources required to facilitate student involvement. Some teachers reported difficulty in identifying and recruiting students who are willing and able to participate. Bovill et al. also warned that the unequal power dynamics between students and faculty/staff that may hinder effective collaboration and that there existed a potential for conflict or disagreement between students and faculty/staff over the direction of the development process.

Marquis et al. (2019) surveyed students involved in student-faculty partnership programs at four universities in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada and found that they faced barriers in terms of their participation in these partnerships. They reported that the most common barrier that students face when participating in student-faculty partnership programs is the fear of not being able to commit to a project. Other barriers mentioned by students included lack of time, lack of information about the program, and concerns about the program’s inclusivity. These findings have significant implications for scholars and practitioners of student-faculty partnerships, as they highlight the importance of addressing students’ concerns about program inclusivity and ensuring that students have adequate access to information about the program.

1.5 Good practice

There are elements of good practice in student-teacher co-production that may help to ameliorate the typical challenges of such partnerships. Effective co-production partnerships.

recognize the inherent and complex interplay of power and expertise and use it advantageously. While staff members hold more formal authority, students bring valuable experiential knowledge and insights into the learning needs of their peers (Higgins et al., 2019). Ongoing reflection and discussion among the student and staff partners, with a focus on identifying and addressing the learning needs of students in the course is crucial for a more collaborative and responsive approach to teaching and learning, with students and staff working together to design and implement effective learning activities.

The Students as Learners and Teachers (SaLT) partnership program (Cook-Sather, 2020) is a structured framework for academic staff and students to co-create teaching and learning practices. The staff and students involved in the program engaged in regular dialogue and reflection, with a focus on valuing and incorporating the perspectives and experiences of both groups. This creates a safe and supportive space for dialogue and encourages ongoing reflection and improvement. The program includes several components that are considered good practice and contribute to SaLT’s success. Teaching staff are given the opportunity to participate in partnerships with students and attend a pedagogy seminar in exchange for a reduced teaching load in their first year. Students apply to become student consultants that any and all teaching staff can choose to work with at any time. Student consultants are paired with staff based on compatibility of schedules, to support the effective use of both of their time. Student consultants attend an orientation and learn a set of guidelines, visit their staff partners’ classes once a week, and take detailed observation notes. They have one-on-one weekly meetings with their staff partners to affirm what is working well and what could be revised to make the course more inclusive. Student consultants also meet weekly with other student consultants and the director of SaLT. One of the most important components of the program is that the university demonstrates that it values the students’ voice and work by paying them by the hour at the top of the student pay scale. In lieu of pay, students can choose to earn academic credit for their work. Overall, the SaLT program provides a structured framework for academic staff and students to work together in co-creating teaching and learning practices that are more equitable and inclusive.

2 Our co-production journey: the diversified project

2.1 The diversified project

The Diversified Project at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) stands as a testament to the transformative power of targeted interventions, co-production, and support. This initiative, rooted in empirical research and a commitment to inclusivity, seeks to bridge the gap between neurodivergent students and the broader academic community. By fostering an environment where neurodivergent students are not only accommodated but celebrated, the project aims to shift the narrative from one of mere integration to genuine empowerment.

This section delves into the intricacies of the Diversified Project, highlighting its impact on neurodivergent students’ academic and personal growth. By sharing our journey, experiences, and personal reflections, we aim to shed light on the profound ways in which targeted support can reshape the tertiary education experience for neurodivergent individuals.

2.2 Genesis of the diversified project

The Diversified project began with a neurodivergent student having difficulty understanding assessment briefing, due to its formatting and confusing structure, so rather than complaining, she decided to re-design the assessment briefing in a more accessible manner. When she returned the briefing to the course convenor, he was so impressed that he involved a university education developer and the three collaborated on the development of an exemplar template that is now used within the course moving forward and available to the entire university community via the university’s Teaching and Learning web page.

The series of events began with a dialogue between the aforementioned student and another neurodivergent peer, in which they shared experiences and insights about the challenges faced in tertiary education settings. Subsequently, the Academic Lead of Education from the university’s disability institute reached out to the group. Discovering their mutual aspiration to enhance the university’s accessibility, they secured grant funding to initiate their vision. The project’s primary objectives were twofold: to gain a deeper understanding of the specific needs of neurodivergent students and to develop actionable recommendations for faculty to elevate the inclusivity and accessibility of their teaching approaches. Consequently, the “Diversified Project” was launched.

2.3 Workshops: listening to student voices

Within the University of New South Wales (UNSW), amidst the diverse range of students, there exists a group whose experiences often go unnoticed: neurodivergent students. These are students with conditions like autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and more. Their journey through academia is punctuated with unique challenges, from sensory issues to understanding and navigating the nuances of traditional learning environments.

While the group acknowledged the global academic community’s commendable efforts in promoting diversity, they felt that the discourse on neurodiversity remained nascent. The longstanding “one-size-fits-all” approach to tertiary education, albeit unintentional, often made neurodivergent students feel like they were trying to fit square pegs into round holes. The issue extends beyond just grades or academic performance; it’s about ensuring students feel recognized, comprehended, and cherished.

Our conversations with these students at UNSW painted a poignant picture. Stories of feeling unsupported, tales of isolation, and accounts of untapped potential. It became evident that while UNSW prided itself on its diverse student body, there was a pressing need to address the unique challenges of its neurodivergent community.

The Diversified Project wasn’t just about creating support systems; it was about reimagining the academic landscape for neurodivergent students. It was about fostering a sense of belonging, building bridges of understanding, and most importantly, empowering these students to realize their full potential. In the grander scheme of things, the Diversified Project is more than just a university initiative. It’s a reflection of a global shift toward a more inclusive educational paradigm. As the discourse around neurodiversity gains momentum, it’s high time institutions like UNSW lead the charge, ensuring every student, irrespective of their neurological makeup, finds their place under the academic sun.

2.4 Recommendations

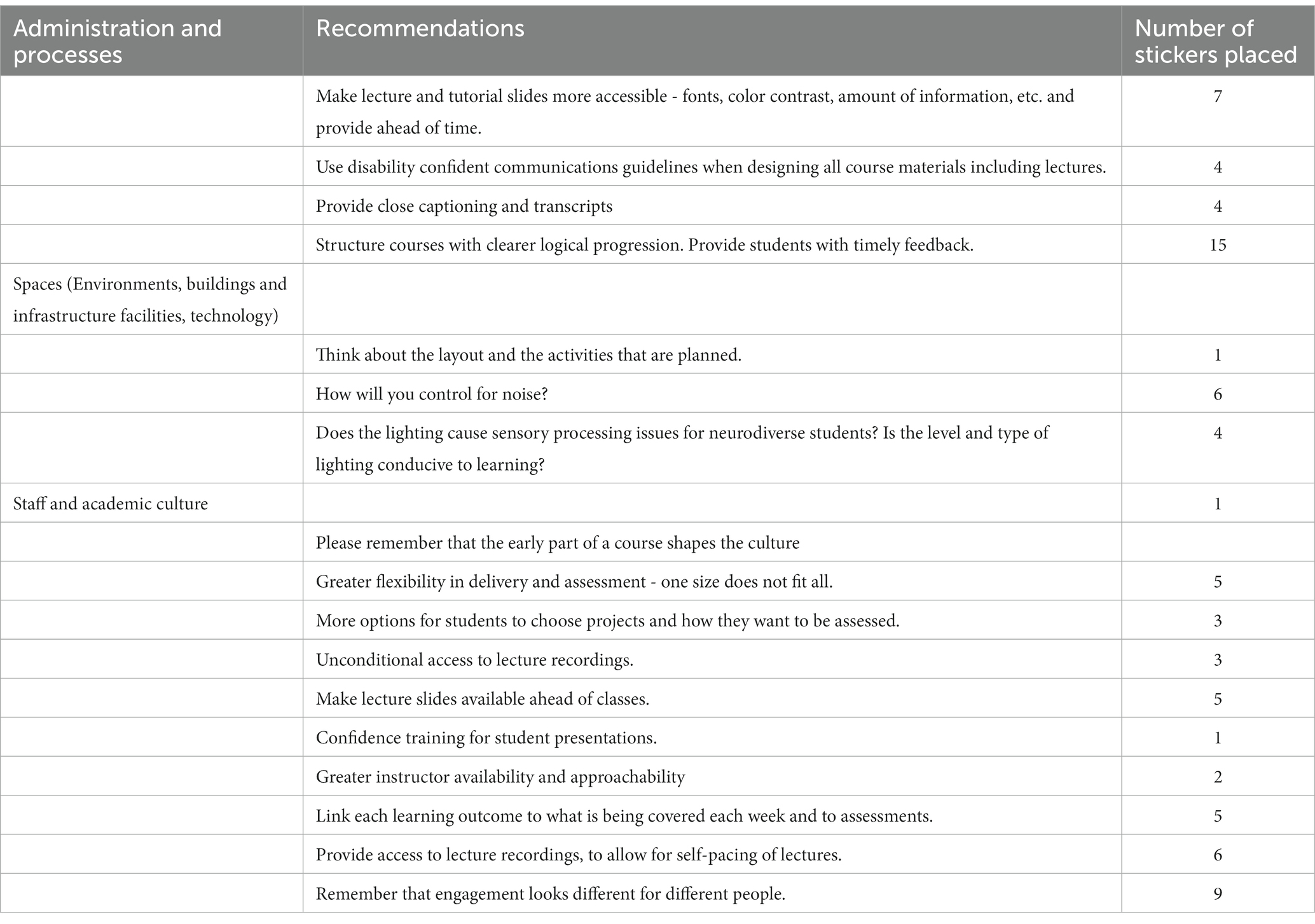

Our Diversified Project workshops were attended by neurodiverse students and neurodiverse and neurotypical teaching and other staff. The following is a summary of the cumulative outcomes and recommendations emerging from the three workshops. We have organized these into categories that emerged during our workshops: (a) Admin/processes, (b) Spaces, (c) Staff/academic culture, (d) Student identity and culture. These recommendations have been further grouped into actions that should be taken at Systemic (university wide) level, Faculty level/School level, and Course/Instructor level.

A. Administration/Processes

Systemic level

• Remove the onus for students to have to come up with answers to support their learning- Ask “How can I support everyone to better access teaching and learning in my course?”

• Develop a central checklist for accommodations/modifications to allow students to have more ownership of their supports.

• Make accommodations more specific, such as how to support students in large and small group discussions, working on group projects, etc.

Faculty level/School level

• Change the structure and wording of course outlines to make them more accessible and accurate.

• Course documentation to articulate more specific outcomes based on careers/long-term benefit.

• Pacing of lectures should take ability to engage into account.

Course/Instructor level

• Make lecture and tutorial slides more accessible- fonts, color contrast, amount of information, etc. and provide ahead of time.

• Use disability confident communications guidelines when designing all course materials including lectures.

• Provide close captioning and transcriptions (both MS Teams and Zoom support live captioning).

• Structure courses with clearer logical progression.

• Provide students with timely feedback.

A. Spaces (Environments, buildings, infrastructure, facilities, technology)

Systemic level

• Consider ways to make lighting suitable for more students. How does lighting affect visibility of screens?

• Audio amplification makes the lecture more accessible.

• Consider whether students have accessibility to technology and how to use it.

Faculty level/School level

• Survey for first year students - responsive survey that collates answers and makes recommendations to go to Equitable learning Services (ELS) if a certain level of applicable responses is reached. The survey should provide a detailed picture and trends related to the broader neurodiverse community in a faculty, which can inform investment in resources to support neurodiverse students.

Course/Instructor level

• Match the layout and the activities that are planned.

• How will you control for noise?

A. Student Identity and Culture

Systemic level

• Faculties and their staff (both teaching and admin) should be approachable and consistent with care and support.

• The culture of academe should be accessible and inclusive, as historically it deters and excluded promising neurodivergent students and faculty members.

Faculty level/School level

• Make student programs and experiences collaborative across faculties; currently siloed. For example, there are different orientations for different faculties, different supports, and different expectations. Guidance for teaching staff on how to support neurodiverse students is also different across faculties.

Course/Instructor level

• Trust students regarding special consideration; procuring documentation can often compound the problem, particularly if it is anxiety and/or burnout.

A. Staff and Academic Culture

Systemic level

• To overcome the lack of lived experience by neurotypical teaching staff and students, create awareness of neurodiversity.

• Compulsory training modules for all staff on neurodiversity including casual staff (in manner of ADA Cultural Reflexivity modules).

• Awareness campaign across the university from management down.

• Upper management to foster a more open, compassionate, inclusive culture that addresses the needs of all students + funding to support this.

• Learning Management System bots that provide appropriate support, links to services, and answer questions

• Expand Learning Management System profile or dashboard to link to ELS that ND students can use to self-identify, articulate, update, and notify academics about needs, issues, episodes etc.

• Publish clear guidelines for all staff.

Faculty level/School level

• Pre/Early course survey to inform teachers who is in class/issues/needs/access to technology etc.

• Templates/forms for students to self-identify as neurodiverse.

• More encouragement for students to access help.

• UDL/ULS feedback surveys that flag neurodiverse students to academics (via email?) upfront.

• Flexible attendance/ Opt-in to class modality – Flexible delivery (eg. Self-paced, modular).

• Better early intervention mechanisms.

• Academic expectations adjustment framework.

• Allow students choice of mode of attending and participating.

• Encouragement and training for staff to be able to offer neurodiverse students other modes of engagement rather than current narrow range of expectations, patterns, and understandings of what a “good student” is.

• Course outlines in plain English.

Course/Instructor level

• Consideration that the early part of a course shapes the culture.

• Greater flexibility in delivery and assessment – one size does not fit all.

• More options for students to choose projects and how they want to be assessed.

• Unconditional access to lecture recordings.

• Make lecture slides available ahead of classes.

• Disability/confidence training for student presentations.

• Greater availability and approachability.

• Link learning outcomes to what is being covered each week and to assessments.

• Provide access to lecture recordings, to allow for self-pacing of lectures.

• Remember that engagement looks different for different people.

2.5 Key initiatives

2.5.1 Neurodiversity video

During the workshops, students raised concerns about the lack of awareness around neurodiversity, which we have detailed in the recommendations above. Students felt that it was important “To overcome the lack of lived experience by neurotypical teaching staff and students, (and) create awareness of neurodiversity.” Increasing awareness of and fostering an inclusive environment of neurodivergence enables the neurodivergent community to feel heard, be seen, and improves the likelihood of the uptake by staff of any resources or materials that Diversified produce. The Diversified team, comprising neurodivergent staff and students, plays a pivotal role in advocating for neurodiversity within the academic community. They are catalysts for change and are committed to creating an environment where neurodivergent students can flourish.

The Diversified team partnered with the UNSW Arts, Design and Architecture (ADA) portfolio of Disability and Mental health Champions Karen Kriss (Diversified staff team member) and Alexander Smith to produce a video in response to these concerns around awareness. The video was carefully crafted by these champions alongside the Diversified team (both staff and students) and a cinematographer, aiming to provide a platform for neurodivergent students to share their experiences and insights.

ADA Disability and Mental health Champion Karen Kriss, the lead and producer for this video, met with a cinematographer and discussed the potential for the narrative to be driven by a set of questions around neurodiversity that the group devised. The Diversified group agreed it was important to have these set of questions as a platform that you can steer the message from for example “this is what my life is like, this is what my life is like on campus.” The questions were designed to evoke meaningful responses, enabling a deeper understanding of neurodiversity.

A comprehensive list of 42 questions was considered by Diversified, encompassing various themes discussed during the workshops. These questions were refined to the following 15:

1. Tell us a bit about yourself, and what you do at UNSW?

2. What is your understanding of the term ‘neurodiverse’?

3. In one sentence, what does neurodivergent mean to you?

4. What are some of the benefits you have found in being neurodivergent?

5. What strategies have you used to get to this point in your university career?

6. If you could go back in time, what advice would you give yourself in your first week of university?

7. What do you wish you knew now that you did not before, which might help other neurodiverse students?

8. What would an accessible and inclusive UNSW look like for you as a neurodiverse student?

9. How could the university at large better support neurodivergent students?

10. As a neurodiverse student, what is one thing you wished your lecturers and fellow students knew?

11. What is the most effective way for you to receive and learn new information?

12. How do you think your lecturers could support you better?

13. What type of support could your tutors provide to assist you in class?

14. What are 3 things that would help you the most in understanding the course work and completing assessment tasks?

15. What is your experience of accessing support at UNSW?

The video’s process was initially intended to follow these scripted questions but during filming this evolved into a more improvisational session. This approach provided a platform for a more genuine and engaging dialogue. While these questions were helpful for directing the kind of content and flow of ideas for the video, on the day of filming it became more conversational.

Karen created an initial edit of the content which the Diversified group commented on, which then gave the cinematographer a narrative and flow for the whole video. The Diversified group made comments on aspects of the video including the pacing, the background sound, the footage being used, and the overall message conveyed.

This collaborative initiative which culminated in the creation of this neurodiversity video, demonstrates the power of students taking the lead in advocating for change. The video provides valuable insights and advice for other neurodivergent students, helping them navigate their university experiences more effectively. The video underscores the importance of creating a university that better supports neurodivergent students, including improvements in teaching methods and support services. It also offers a sense of belonging and community.

2.5.2 Storybox

2.5.2.1 Storybox was showcased in the Sydney CBD area

During 2021 Diversified began experimenting in post-COVID Sydney with digital media in urban placemaking contexts. Our experience of the urban environment and our community can also be shaped by very specific sets of conditions and relationships, and this can shape the types of stories we can tell. We can utilize this to build participatory methods that give voice to marginalized communities as in our recent/ongoing UNSW Art & Design project “Co-designing Digital Inclusion” with neurodiverse participants.

This project involved the Diversified team collaborating with an industry partner (Esem Projects) working with public digital media, and members of Sydney’s neurodivergent community. The study was focused on co-designing digital inclusion by collaboratively empowering people who identify as neurodivergent (those with autism, ADHD, Dyslexia, social anxiety, and other associated conditions). The project piloted a pluriversal community-led participatory design framework that is representative of an approach to design where in the words of Arturo Escobar (2018) the aim is to co-create, “a world where many worlds fit.”

This research project was significant because it advanced new models for establishing the value of inclusive public space media while addressing digital inclusion for neurodiverse communities, public awareness of, and engagement with neurodiversity through the pluriversal participatory co-design framework. In a series of collaborative participant – led workshops, neurodivergent stakeholders framed their individual issues and problems and created audio-visual content (digital storytelling, visual information, digital artworks). These were then deployed on our industry partner Esem Project’s digital media platform STORYBOX1 in cultural programming to help re-activate post-COVID19 public spaces at sites around Sydney during 2023–2024.

The videos were also deployed via STORYBOX on UNSW campuses as part of the Faculty of Arts, Design, and Architecture’s Health research showcase ADAxHealth.

The research focus is on inclusivity to build the resilience and well-being of neurodivergent communities who do not have a public platform to express their experiences and life stories thereby remaining invisible and/or misunderstood in the community.

This project further tests design co-creation and participation models for inclusive design that establish, negotiate, and communicate the value of community-led digital urban interventions for better and more socially sustainable and inclusive placemaking. We are seeking to provide evaluative mechanisms enabling development of a more balanced and inclusive public digital media ecology and to demonstrate public and stakeholder impact and engagement. We argue novel and more inclusive forms of digital, participatory placemaking can build resilience, inclusion, and socially sustainable urban places.

2.5.3 Public engagement

2.5.3.1 Diversity festival

In conjunction with the UNSW Diversity Festival held in September 2023, the Diversified Project established a dedicated stall. Our primary objectives were to elevate awareness about neurodiversity, share the project’s milestones, and engage attendees with our set of recommendations, specifically those at the course/instructor level. Attendees were given stickers to mark their recommendation preferences on laminated boards. A total of 94 students responded. The student feedback on the recommendations and what they would prioritize is depicted in Table 1.

The festival was a melting pot of diverse cultural backgrounds and varying levels of familiarity with neurodiversity. One of the most enlightening moments was witnessing neurotypical students recognize their shared challenges with their neurodivergent peers. Another heartening interaction was with a student eager to understand neurodiversity better to support his neurodivergent friends, having been previously unaware of the challenges they face in a university setting.

2.5.3.2 Presentations

Diversified has promoted the group and our various projects by presenting our work at various events on and off campus. These include the 2022 UNSW Education Festival, 2022 UNSW Inclusive Education Conference, and UDLHE Digicon 2023 – Multiple Means of Sharing UDL, an international conference. All members of the group also frequently present their work on accessibility, neurodiversity, and UDL in an effort to improve life on campus for neurodivergent students globally.

2.5.4 Co-production project

Historically, students, especially those who are neurodiverse, have had little say in their learning (how coursework is delivered) at tertiary education institutions. This project aimed to address this inequity by promoting co-production in course design and delivery between neurodivergent students and instructors. This was accomplished through the establishment of a student consultation group and the delivery of three student-instructor co-production workshops. The first workshop centered around framing the problem, the second supported student-instructor teams to respond to the problem together, and the third provided time and space for the teams to refine their ideas/products. Neurodivergent students were recruited to act as a consultation group with Diversified student lead, Aaron Bugge, leading the workshops and showcase.

The main outcomes of the workshops were assembled into a toolkit of freely available instructional “How to” sheets, checklists, and videos (with examples and insights from neurodivergent students and staff) co-designed with neurodivergent students to assist instructors in operationalizing the recommendations of the Diversified Project, including:

• Making lecture and tutorial slides more accessible - fonts, color contrast, amount of information, etc.

• Using disability confident communications guidelines when designing all course materials including lectures.

• Providing close captioning and transcriptions.

• Structuring courses with clear logical progression using UDL principles to create greater flexibility in delivery and assessment (multiple means of representation, engagement, action/expression), linked to learning outcomes.

• Creating an inclusive course culture.

• Preparing students to present in class.

This project was well situated under the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework that guides instructional design to be flexible and address the needs of many learners through the provision of multiple means of representation, engagement, and expression. It incorporates accessibility and inclusive practices into the design of courses, so that there is less need for accommodations and modifications for individual students.

2.6 Recognition and impact

The strength of Diversified as a group can be seen through the various projects and measures of recognition that showcase the positive impact of the project on neurodivergent students. The team’s work has been recognized with two awards. As a result of the video and work on the Diversified project and its impact on the university community, the Diversified team won the Faculty of Arts, Design and Architecture Dean’s High Impact Award at the 2022 UNSW Education Festival. The team won an excellence award at the Australian Disability Clearinghouse on Education and Training, Accessibility in Action Awards 2023.

The Diversified Team was recognized in Australian national media when it was included in an ABC video titled Women with ADHD 'falling through the cracks' with diagnosis and treatment (1.77Million subscribers, 5,800 views). The Neurodiversity video and other Diversified initiatives have been shared to several social media sites and viewed by many: The University’s YouTube page (13,700 subscribers, 374 views), the University’s Facebook page (44, 793 subscribers, 220 reactions), the Faculty’s Instagram page (14,900 followers), the Education Focused Bulletin (400 members), Teaching for Equity and Diversity (TED) Community of Practice (100 Members), Education Focused CoPs (100 Members), Faculty Yammer (1,383 followers), and the UNSW Disability Innovation Institute newsletter (912 subscribers).

The Storybox project has been the subject of public exhibitions with its 11 videos exhibited on an Esem STORYBOX at Campsie, NSW March 2023, outside Customs House, Circular Quay, Sydney, NSW April 2023, and combined with ‘Tiny Stories’ and exhibited at the ADAxHealth Exhibition at The Bank, UNSW (Oct – Nov 2023). Dr. Sarah Barnes, Esem Storybox industry partner declared, “to be honest, being down there at Customs House with the participants was one of our all-time favorite Storybox moments…thank you!”

2.7 Future vision

As the landscape of tertiary education evolves, the Diversified team envisions a transformed and inclusive learning environment where neurodivergent students thrive. The Diversified project, which began as a grassroots initiative and inspiration for neurodivergent students, serves as a model for co-production and partnership between staff and students. This sets a standard for inclusive education that reaches those that are often hidden within a tertiary environment. This project echoes The Students as Learners and Teachers (SaLT) partnership program (Cook-Sather, 2020), where it places students on an equal footing with educators as active participants in shaping educational practice.

In the future vision of university learning we see systematic changes, where being neurodivergent is not just acknowledged but celebrated, and students’ perspectives and critique is intrinsically linked to reshaping their learning experience. Universities will have comprehensive support systems in place, including mandatory training for both staff and students. This would promote awareness of neurodiversity and the compulsory implementation of Universal Design for Learning in all course design. The entire academic culture will be approachable and consistent, ensuring that neurodivergent students feel valued, supported, and celebrated. Neurodivergent students will have a voice in shaping their education experience and no longer face barriers related to curriculum design, assessments methods or social integration. They will be empowered to participate in the co-creation of teaching and learning materials and practices. Course materials will in turn be made more accessible for everyone.

This future vision imagines physical spaces will be designed with neurodiversity in mind. Teaching and learning environments will feature suitable lighting, sensory awareness spaces, and technology that is easy to use and made accessible to all. Faculties and academics will work together to create a culture of inclusion, where support is collaborative across faculties and students have the freedom to choose modes of participation that suits their changing needs. All academics will recognize that a one size fits all approach to course delivery does not suit the need for increased flexibility for a multitude of learning styles and needs.

The Diversified project has the potential to inform other universities to follow suit, leading a global shift toward more inclusive educational paradigms. The impact also extends beyond the academic realm and holds promise for transforming workplaces. By fostering a culture of co-production, inclusivity and empowerment in higher education, this initiative paves the way for a deeper understanding of the value of neurodiversity. As graduates who have experienced these methods of co-creation and inclusive methods graduate, they are more likely to carry these values into their workplaces. Diversified’s emphasis on breaking down barriers, valuing individual strengths and creating inclusive spaces, serves as a catalyst for more neurodiverse workplaces, leading to improved productivity, innovation, and well-being for employees.

In the immediate future, the Diversified team is undertaking a commitment to amplifying student voices in course design and increasing the impact of its recommendations at UNSW. The group aims to leverage internal and external presentations, additional workshops and funding to create specific course design checklists, training material and videos for academic staff. The ultimate aim is to firmly embed Diversified’s co-production approach within the fabric of the UNSW community.

3 Aaron Bugge - a neurodivergent student’s journey at UNSW

As a mature-aged student at UNSW with neurodivergent traits, my academic journey has been marked by both challenges and triumphs. My early educational experiences were limited, having grown up in an environment characterized by lower education levels and without the formal completion of Year 12. Despite these initial setbacks, I am currently pursuing my undergraduate degree in molecular biology, then honors and I have aspirations to undertake a PhD in education. All would not have been possible without the alignment of my values with the project and my passion for creating more accessible systems for minority group individuals.

Upon my initial entry into the university setting, I grappled with feelings of alienation, self-doubt, and the feeling that I did not belong. The academic environment felt foreign, and I often questioned my place within it. These sentiments were exacerbated by my neurodivergent nature, which often made me feel as though I was an outlier, struggling to fit the mold of traditional academia.

However, my trajectory shifted dramatically upon my involvement with the Diversified Project at UNSW. This initiative provided me with a profound sense of belonging, as being backed by a dedicated team of professionals and academic staff, provided the support and resources I desperately needed. Their passion and commitment to fostering an inclusive academic environment played a pivotal role in my transformation. Today, I stand confident, resilient, and empowered, ready to tackle the challenges that lie ahead.

The significance of this project extends beyond academic support. It has granted me a voice, ensuring that my unique experiences and perspectives are acknowledged and valued by the broader academic community. This validation has been instrumental in alleviating the anxieties and doubts that once clouded my academic pursuits.

Reflecting on my personal history, marked by adversities such as exposure to substance abuse, familial violence, and being the first in my family to break certain detrimental cycles, the importance of such inclusive initiatives becomes even more evident. My journey serves as a testament to the transformative power of targeted support and research-driven interventions in the realm of accessibility.

It is my fervent hope that, with continued efforts in this direction, future generations, including my neurodivergent nephew, will experience an even more inclusive and supportive UNSW.

4 Conclusion

The Diversified Project not only achieved its primary objective but also transcended its foundational goals. At its core, the initiative aimed to foster co-production in course design and delivery, bridging the gap between neurodivergent students and their course instructors. This was realized through a series of collaborative workshops, where both neurodivergent students and invested teaching staff convened to delineate the challenges unique to the neurodivergent community at UNSW. Together, they ideated solutions and strategies to address these concerns.

However, the impact of the Diversified Project extended beyond its structural objectives. For many neurodivergent students, the project represented a beacon of hope and validation. It signified that their voices, which had often been marginalized or overlooked, were not only being heard but were also instrumental in driving tangible change. The sense of empowerment and validation this initiative offered cannot be understated. It conveyed a powerful message: that UNSW is committed to not just acknowledging but actively addressing the unique needs of its neurodivergent community, emphasizing the statement “nothing about us, without us.”

As we move forward, our dedication to amplifying these voices remains unwavering. The Diversified Project will continue to champion the recommendations derived from our collaborative efforts. Through presentations, promotional videos, social media campaigns, and ongoing project initiatives, we aim to embed the ethos of this project deeply within the UNSW fabric. Our pursuit for funding from various avenues is driven by a singular vision: to make the Diversified Project an indispensable pillar of the UNSW community, ensuring an inclusive, accessible, and empathetic academic environment for all.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

TC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. KK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft. KW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. UNSW Division of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (2 separate grants, 2023 and 2021). UNSW School of Art and Design Research Support Scheme (2022). UNSW Arts, Design and Architecture (ADA) Disability and Mental Health (2021).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support and participation of neurodivergent students and colleagues, who gave their time and shared their expertise and lived experiences in each of Diversified’s projects to make them a reality.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Bovill, C., Cook-Sather, A., and Felten, P. (2011). Students as co-creators of teaching approaches, course design, and curricula: implications for academic developers. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 16, 133–145. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2011.568690

Brown, A. H., and Green, T. (2018). Beyond teaching instructional design models: exploring the design process to advance professional development and expertise. Journal of Computing in Higher Education 30, 176–186. doi: 10.1007/s12528-017-9164-y

Bunbury, S. (2020). Disability in higher education – do reasonable adjustments contribute to an inclusive curriculum? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 24, 964–979. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1503347

CAST . (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2. Available at: http://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Cook-Sather, A. (2018). Listening to equity-seeking perspectives: how students’ experiences of pedagogical partnership can inform wider discussions of student success. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 37, 923–936. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2018.1457629

Cook-Sather, A. (2020). Respecting voices: how the co-creation of teaching and learning can support academic staff, underrepresented students, and equitable practices. High. Educ. 79, 885–901. doi: 10.1007/s10734-019-00445-w

Cumming, T. M., and Rose, M. C. (2021). Exploring universal design for learning as an accessibility tool in higher education: a review of the current literature. Aust. Educ. Res. 49, 1025–1043. doi: 10.1007/s13384-021-00471

Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the pluriverse: radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds. Duke University Press, Durham.

Higgins, D., Dennis, A., Stoddard, A., Maier, A. G., and Howitt, S. (2019). Power to empower: conceptions of teaching and learning in a pedagogical co-design partnership. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 38, 1154–1167. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2019.1621270

Kim, M. M., and Kutscher, E. L. (2021). College students with disabilities: factors influencin growth in academic ability and confidence. Res. High. Educ. 62, 309–331. doi: 10.1007/s11162-020-09595-8

Ladau, E. (2021). Demystifying disability: what to know, what to say, and how to be an ally. Ten Speed Press. California

Marquis, E., Jayaratnam, A., Lei, T., and Mishra, A. (2019). Motivations, barriers, & understandings: how students at four universities perceive student–faculty partnership programs. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 38, 1240–1254. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2019.1638349

Slates, S., and Cook-Sather, A. (2021). Voices from the field-the many manifestations of successful partnership. Int. J. Stud. Part. 5, 221–232. doi: 10.15173/ijsap.v5i2.4911

Smith, S. J., Rao, K., Lowrey, K. A., Gardner, J. E., Moore, E., Coy, K., et al. (2020). Recommendations for a national research agenda in UDL: Outcomes from the UDL-IRN preconference on research. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 30, 174–185. doi: 10.1177/1044207319826219

Keywords: co-design, co-production, neurodivergent, universal design for learning, tertiary education, university

Citation: Cumming TM, Bugge AS-J, Kriss K, McArthur I, Watson K and Jiang Z (2023) Diversified: promoting co-production in course design and delivery. Front. Educ. 8:1329810. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1329810

Edited by:

Maria Esteban, University of Oviedo, SpainReviewed by:

Elena Mirela Samfira, University of Life Sciences “King Mihai I” from Timisoara, RomaniaCopyright © 2023 Cumming, Bugge, Kriss, McArthur, Watson and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Therese M. Cumming, dC5jdW1taW5nQHVuc3cuZWR1LmF1

Therese M. Cumming

Therese M. Cumming Aaron Saint-James Bugge1,3

Aaron Saint-James Bugge1,3 Karen Kriss

Karen Kriss Zixi Jiang

Zixi Jiang