- 1Faculty of Education, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Curriculum, Teaching & Learning, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Narrative inquiry has been widely used in different disciplines around the world. In this article, we focus on narrative inquiry in China where we start by retelling our first close contact with narrative researchers in China in 2007 when Professor Gang Ding at East China Normal University invited leading Chinese researchers to a three-day narrative inquiry workshop co-planned with us (Connelly and Xu). Second, we review narrative studies published in Chinese to demonstrate how widely narrative inquiry has been adopted in educational studies in the country in the past two decades by Chinese university researchers, graduate students, and schoolteachers. Next, our review of English literature of narrative studies related to education in China has two important components: English literature on narrative inquiry contextualized in China and narrative inquiry for reciprocal learning in teacher education and school education between Canada and China. Both reveal how narrative inquiry has contributed to international cross-cultural educational studies related to Chinese contexts. Finally, in the “Discussion” section, we provide our interpretation of some current dialogs on narrative inquiry among Chinese educational researchers; for example, the differences between yanjiu 研究 (research) and tanjiu 探究 (inquiry). Some heated discussions surrounding narrative inquiry in China are also highlighted, including: (1) cultural complexities in narrative inquiry, (2) theoretical frameworks in narrative inquiry, (3) re-storying and fictionalization processes in narrative inquiry, and (4) ethical considerations in narrative inquiry. To conclude, with cases selected and elaborated from the Canada-China partnership, we demonstrate how narrative inquiry has enabled us to develop “reciprocal learning” as both a conceptual framework and a methodological approach to building a multidimensional bridge for reciprocal learning in education between the West and East. This Reciprocal Learning approach reflects our global comparative studies view that the path to global cross-cultural harmony and understanding lies with collaborative action plans among people of different cultures. Writing this article on narrative inquiry in China enabled us to reflect on and learn from narrative inquirers and researchers in China while sharing what we have done in our own narrative inquiry.

Introduction

Narrative inquiry is a relatively recent research methodology worldwide (Connelly and Clandinin, 2006) and has taken hold in China since about the year 2000. Our first close contact with narrative inquiry in China was in 2007 when Professor Gang Ding at East China Normal University invited leading Chinese researchers to a three-day narrative inquiry workshop co-planned with Shijing Xu and Michael Connelly. The Shanghai Workshop: narrative inquiry in teaching and research, was subsequently published as a book in Chinese (Ding and Wang, 2010). Key features of the growing Chinese interest in and literature on narrative inquiry characterized the workshop and served as the starting point for this article as the origins, development, and future possibilities for narrative inquiry in China are discussed.

On day one of the workshop, Professor Ding led a panel emphasizing how educational narratives in the form of teaching stories told by schoolteachers opened the door for primary and secondary schoolteachers in China. Educational research tended to be dominated by theories in the quantitative paradigm. Narrative research helped bridge the gap between theory and practice for Chinese university researchers and school practitioners (Ding, 2008a). Professor Zhan Wang from Guangxi Normal University discussed how she and her graduate students had been influenced by Connelly and Clandinin’s narrative work and had done narrative studies in teaching and teacher development centered on teachers’ personal beliefs, teacher as researcher, novice teacher life, head teacher’s job burnout, and so on (Wang, 2007). Professor Juanjuan Geng’s narrative case study research of a female middle school teacher’s education beliefs was a highlighted example at the Shanghai workshop (Wang, 2007). Another example was Professor Lianghua Liu, who was known for his narrative work, especially for an online platform he created for schoolteachers to share their educational narratives (Wang, 2007). Professor Zhan Wang pointed out the differences between educational narratives told mostly by schoolteachers as teacher stories and narrative research done by university researchers and graduate students who were seeking theoretical guidelines for their narrative research. She also discussed the distinction between the fictional “I” in literature and the real “I” in educational narratives. Using this distinction, she emphasized the importance of authenticity in narrative research based on substantial field work research, which is fundamentally different from the narratives in novels. Professor Zhou (2008) from East China Normal University introduced his book that tells stories of the early-year school teaching life of five well-known historical figures known as great Masters of Modern China during the early 20th century period of the Republic of China. His book illustrated another of Professor Ding’s points on the localization of narrative research in China. Localization refers to the idea that narrative researchers should contextualize Chinese narrative discourse within its own cultural and social context, rather than merely adopting Western contexts as templates to follow. A group of scholars supported Ding’s argument (see Wu and Jiang, 2009; Wu, 2011; Liu, 2020, 2021). Professor Zhou described how his writing of the historical narratives of these Chinese historical figures was influenced by traditional Chinese narratives. He referenced the Chinese classic masterpiece, a dream of red mansions 红楼梦, and the novels written by Congwen Shen 沈从文, a well-known writer in the early 20th century China. Professor Ju (2007) from East China Normal University, a plenary presenter, described how she saw narrative inquiry as an important approach to understanding teacher development through sophisticated accounts of lived experience. In contrast to Professor Zhou’s intensive literature analysis to create historical narratives, she spent over a year in a secondary school in Shanghai studying the professional lives of six teachers. She published one of the earliest Chinese books on a narrative inquiry into teachers’ personal practices (Ju, 2004). She emphasized how the publication of her research helped legitimate teachers’ sense of the scholarly value of their experiences and helped them to overcome the notion that their professional work was too “common” to be noticed as a valuable topic of academic research (Ju, 2007).

As invited speakers, Michael Connelly and Shijing Xu made three one-hour plenary presentations, followed by small-group discussions, on the topics: “What is narrative inquiry,” “What do narrative inquirers do,” and “Issues in narrative inquiry.” One of the points generating discussion was the idea of narrative inquiry taking place at a formalistic-reductionistic boundary and how narrative inquirers lived their academic lives at such boundaries (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000). They stated that narrative inquiry searched for general theoretical explanations and shared features with traditional formalistic inquiry. At the same time, narrative inquiry was concrete, specific, and local and shared features with traditional reductionistic empirical inquiry. Chinese researchers expressed this tension and associated publication and research funding uncertainties. It appeared that two main Chinese research ideas were at work in workshop participant communities: a movement toward abstract theoretical ideas and a tradition of quantitative empirical work. The question of how to position narrative inquiry in this matrix and how to construct theory was of interest.

Professor Gang Ding is widely recognized as a leading advocate of narrative inquiry (Peng, 2010; Yu and Lau, 2011; Zhou, 2011); he is considered the best-known advocate of narrative inquiry in China as described by Zhou (2011). Yu and Lau (2011) credit Ding as one of the earliest scholars in China to show a keen interest in narrative inquiry. They highlight that his substantial contribution to the field is notable through a series of five monographs dedicated to this area of study.

In his 2009 work, Ding highlighted the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in educational research, emphasizing the need to transcend disciplinary boundaries to better understand and cultivate individual learning development. He highlighted the social and cultural aspects of education, advocating for a holistic understanding of the field that integrates theory, practice, and a diverse range of methodologies. He described how the application of diverse methodologies, including narrative inquiry, can “push forward with educational development and understanding toward education, especially education in China” (Ding G., 2009, p. 2).

In 2019, Ding accepted an interview by editorial department of the China Higher Education Review (中国高等教育评论期刊编辑部), in which he discussed his doctoral students’ dissertations. Hongchang Si conducted an exceptional study for his doctoral thesis titled schools embedded in villages: a historical anthropological inquiry into ren village education [嵌人村庄的学校:仁村教育的历史人类学探究] (Si, 2009). This work, which combines anthropological methods with educational narrative research, was recognized as one of the top 100 outstanding doctoral dissertations in China in 2008. As Professor Ding described, Si’s research stands out for its depth and rigor in the field of educational research, setting a high benchmark that few have matched to date. Another student, Zhou (2004), focused his doctoral thesis on educational discourse in 11th-century China. His thesis, titled knowledge, moral education, and desire: educational discourse in 11th century China [知识、教化与欲望——中国十一世纪的教育话语] explores this era through the lens of Neo-Confucianism, incorporating elements from novels and dramas. Lijing Jiang, another of Ding’s students, wrote a doctoral thesis titled the shadow of history: educational memories of a generation of female intellectuals [历史的背影:一代女知识分子的教育记忆]. This research presents a narrative history of three female university students—Feng Wanjun, Lu Yin, and Cheng Junying—during the Republic of China era (Jiang, 2012). These women were among the first generation of female university students in modern China and later became scholars, poets, and intellectuals. According to Ding, Jiang’s work, which was nominated for inclusion among the top 100 doctoral dissertations in that year, offers a unique perspective on the lives and educational experiences of these pioneering women.

Fifteen years after the Shanghai Workshop: narrative inquiry in teaching and research, we are honored and humbled to be invited to write about narrative inquiry in China. We (Connelly and Xu) welcome the opportunity to reconnect with the great variety of narrative work in China while sharing what we have done with Chinese and Canadian university and school educators for West-East reciprocal learning with narrative inquiry. Chenkai Chi as Xu’s doctoral student has participated in this West-East reciprocal learning project since his master’s program, which has inspired him to embark on a narrative inquiry journey for his doctoral studies. Hence, the collaborative writing of this article reveals the continuity of our narrative inquiry in/with China as well as the continuity of narrative inquiry by three generations of educational researchers in international and cross-cultural settings. For Xu and Connelly, the process is fueled by the energy of memory and the longitudinal collaborative inquiry with university and school educators in the Canadian and Chinese partner institutions while for Chi the energy comes from inquiry beginnings and deep engagement in Xu and Connelly’s international and cross-cultural school-based partnership work. This sense of “we” permeates this article.

Following the above retelling of our story of initial close contact with Chinese narrative research, we first review the narrative research published in Chinese since the first Chinese publication in the field in 2003 (Liu, 2021). The themes and ideas from the 2007 Shanghai Workshop provide a frame to present Chinese narrative work more holistically and show how Chinese university researchers, graduate students, and schoolteachers have adopted narrative inquiry in their teaching and research. Second, we review narrative studies in English related to education in China to summarize how narrative inquiry has contributed to international cross-cultural educational studies in the Chinese context. Finally, we introduce narrative work done by Chinese, Canadian, and American educators and graduate students who have been engaged in Xu and Connelly’s (2013–2020) Canada-China partnership for West-East reciprocal learning in teacher education and school education. With cases selected and elaborated from the Canada-China partnership, we demonstrate how narrative inquiry has enabled us to develop “reciprocal learning” as both a conceptual framework and a methodological approach to building a multidimensional bridge for reciprocal learning in education between the West and East (Connelly and Xu, 2019; Xu and Connelly, 2022). This reciprocal learning approach reflects our global comparative studies view that the path to cross-cultural harmony and understanding lies with collaborative action plans among people of different cultures. It is one thing to know something about another; it is something else to work with another. The reciprocal learning program is a working-with-another program.

Literature review

An overview of narrative inquiry as a research methodology in China

In the previous section we introduced our first close contact with Chinese narrative research in 2007. At that time narrative inquiry in the form of educational narratives (教育叙事) appeared to be a well-received educational approach among Chinese schoolteachers who had contact with the methodology. Only a few researchers were doing narrative inquiry; now in 2023, narrative inquiry as a research methodology is widely used in Chinese educational studies (Ding, 2008a,b; Ding L. L., 2009; Liu, 2009, 2021; Sun and Jin, 2015; Bu, 2021). According to Liu (2021), since 2000, using the keywords education and narrative to retrieve relevant articles, there have been over 2,000 dissertations and theses on narrative and education. Judging from paper citations, much of this work adopts and adapts the Canadian line of narrative research associated with Michael Connelly and Jean Clandinin (Liu, 2007, 2009; Ding, 2008b,c; Sun and Chen, 2009; Li and Sun, 2011; Xue and Liu, 2015). This line of work appears to have been introduced to China by Professor Ding (Wan, 2019; Bu, 2021; Liu, 2021). In 2002, Ding published a book series titled Chinese education: research and review (中国教育:研究与评论), where he included a book by Dr. Juanjuan Geng based on her dissertation educational beliefs: a narrative inquiry into a Chinese female middle school teacher (教育信念:一位初中女教师的叙事探究) that adopted narrative inquiry as its methodology. In 2003, as editor of the East China Normal University journal, global education (全球教育展望), Ding curated a special issue on narrative inquiry in education. In his monograph voices and experiences: narrative inquiry in education (Ding, 2008c), Ding clearly demonstrated how to use narrative inquiry as a methodology to conduct educational research in China. Moreover, with development of digital technology and the internet, Professor Liu (2007) created educational blogs on narrative inquiry in education1 and encouraged teachers in Chinese primary and secondary schools to submit their educational narratives. According to Zhang and Guo (2010), this blog provided a platform for primary and secondary schoolteachers in China to tell their own stories, making it possible for teachers in different regions and cultural backgrounds to exchange educational experiences. Furthermore, some primary and secondary schoolteachers even set up their own blogs to tell their own stories of education and teaching, which gradually popularized the new method of narrative research popular among Chinese primary and secondary schoolteachers. Professor Wang Z. (2008) introduced narrative inquiry as an approach to studying teachers’ classroom experiences in her monograph teachers’ trajectories: narrative research of classroom life (教师印迹:课堂生活的叙事研究). This work sparked teachers’ interest in using narrative research as a method to do educational research, especially under the circumstances that schoolteachers in China are also expected to do educational research for teacher development and promotion. Professor Xiangming Chen, who has done substantial school-based research for decades, has also conducted narrative action research with schoolteachers, in which teachers themselves work as reflective researchers guided by university educators (Chen, 2021). Combining Connelly and Clandinin’s (1990) narrative inquiry with the methodology of action research to resolve teaching problems that teachers often encounter in practice, Chen (2021) argues that:

Narrative inquiry, originally pioneered by Connelly and Clandinin, inherently possesses the potential for action and change. However, since its introduction to our country in the 1990s, this approach has gradually become more objective and neutral, evolving into a more scientific form of “narrative research.”2

Narrative inquiry has also been adopted by many educational researchers in Hong Kong and Taiwan China (e.g., Trahar and Yu, 2015; Eng, 2021; Lau, 2021). To name but a few, Lau (2021) conducted a longitudinal study of family cultural matters encountered as the family moved abroad for his doctoral study. Similarly, Eng (2021) explored cultural encounters as several generations of one family moved back and forth between Mainland and Hong Kong China and the United States. In their edited book, Trahar and Yu (2015) invited authors from Asian Pacific regions to demonstrate how they have used narrative inquiry for educational research. Shijing Xu’s contribution to this volume highlighted the importance of ethical boundaries and considerations in cross-cultural narrative inquiry. Details about ethical concerns of narrative inquiry are considered below in the “Discussion” section.

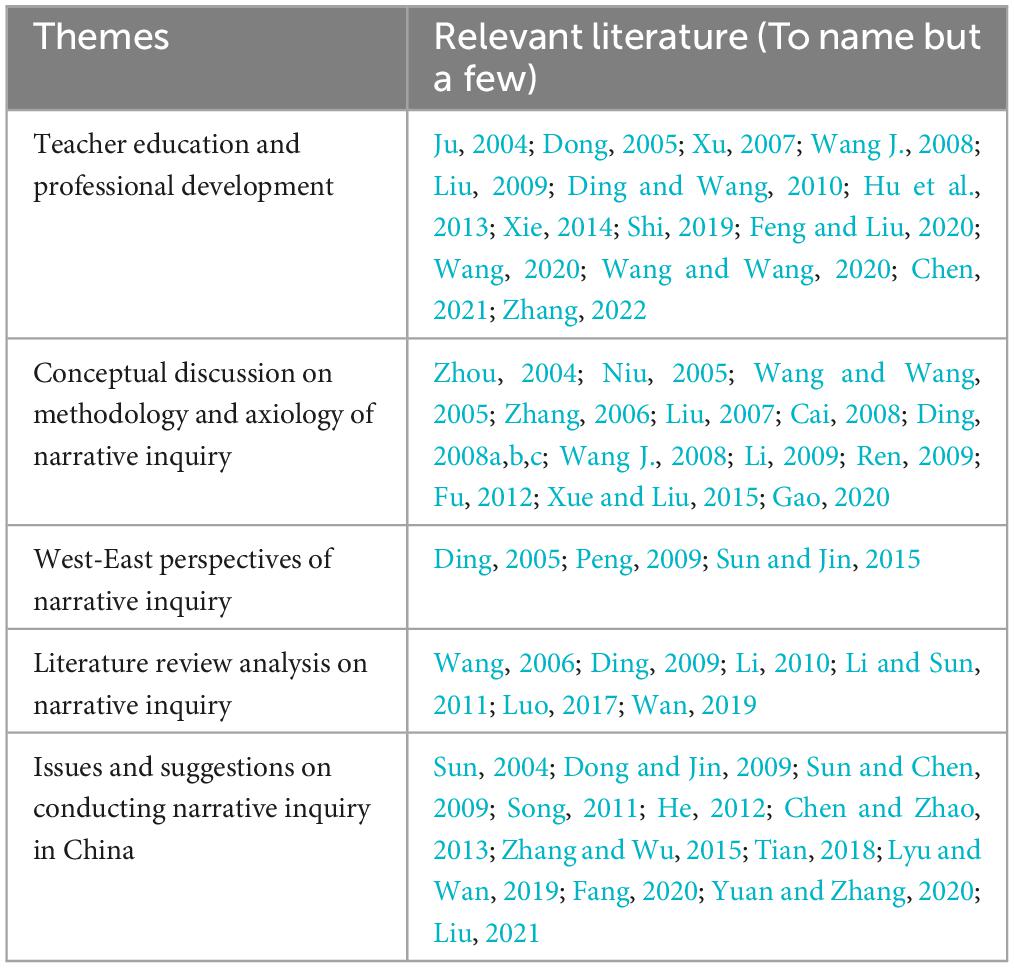

In summary, narrative inquiry has been widely adopted in educational studies in China in the past two decades. The topics Chinese articles published on narrative inquiry in education include: (1) teacher education and professional development, (2) conceptual discussion on methodology and axiology of narrative inquiry, (3) West-East perspectives of narrative inquiry, and (4) literature review analysis on narrative inquiry, and (5) issues and suggestions on conducting narrative inquiry in China. Table 1 provides a list of relevant literature in each theme.

Narrative inquiry as a popular educational approach among Chinese primary and secondary schoolteachers

The information shared at the 2007 Shanghai Workshop and our recent literature review suggest that the popularity of using narrative inquiry in education in China reflects a common theory and practice dichotomy in education (Fu, 2012). Fu (2012) argues that discrepancies between educational experiences and practices on the one hand and theories on the other are hindrances to educational reform in China. It is essential, she says, to combine educational theories with practices to promote educational research and provide valuable suggestions for Chinese education reform. Sun and Chen (2009) argue that the discourse of education research in China is dominated by researchers in universities or organizations, and teachers are marginalized and relegated to the role of implementors of educational theories proposed by researchers. However, narrative research that focused on teaching practices sparked teachers’ research interests and acknowledgment of the value of teacher knowledge. Echoing ideas Ju (2007) shared at the workshop, Niu (2009) found that through the crafting of teacher narratives teachers realize that their daily practices could also be valued. This, in turn, fostered teacher confidence in sharing their teaching narratives. Thus, more and more teachers in Chinese primary and secondary schools are using narrative inquiry to do educational research (Zhang, 2022). At the school level, teachers increasingly document their teaching narratives and reflect on their practices. Many researchers point out that using narrative inquiry this way is a form of professional development for teachers. Recognizing the value of narrative inquiry as a form of action research contributes to competency and reflection (Sun, 2004; Liu, 2005; Yang, 2006; Chen, 2009; Song, 2011; Yang, 2016; Bai, 2020; Fan, 2020; Peng, 2021; Zhang, 2022).

However, this practitioner-based form of narrative inquiry in China has, as in other jurisdictions, led to certain criticisms by university researchers who argue that narrative research by teachers does not constitute academic research. According to Sun and Chen (2009) and Sun and Jin (2015), narrative inquiry among schoolteachers is reduced to merely “telling stories.” For example, Lyu and Wan (2019) distinguish between educational narratives and narrative research. They argue that educational narratives refer to telling the events and phenomena that occurred in educational activities. The purpose of educational narratives is for individuals to describe educational practices and events, and to reflect on the real classroom situations. Educational narratives provide research texts for narrative research. Following this line of thought, teacher narratives are databases for narrative research but, in and of themselves, do not constitute research. Comparatively, Lyu and Wan (2019) believe that educational narrative research means doing educational research in a narrative manner and providing in-depth analysis on the insights and reflections obtained from them. The purpose of narrative research is to excavate the educational significance, essence, and regular patterns behind educational events, and thus to promote the formation of a new educational concept. Wu (2014) points out that to the extent that teachers and school administrators think that documenting educational narratives such as teaching blogs, reflection notes, and classroom observational notes can be regarded as genuine “research,” contributes to a situation in which teachers may be required to submit “narrative research” as a form of teacher evaluation. Gradually, Wu raised the concern that teachers may have to make up stories to meet the requirement.

Narrative inquiry as a research methodology in Chinese graduate students’ theses and dissertations

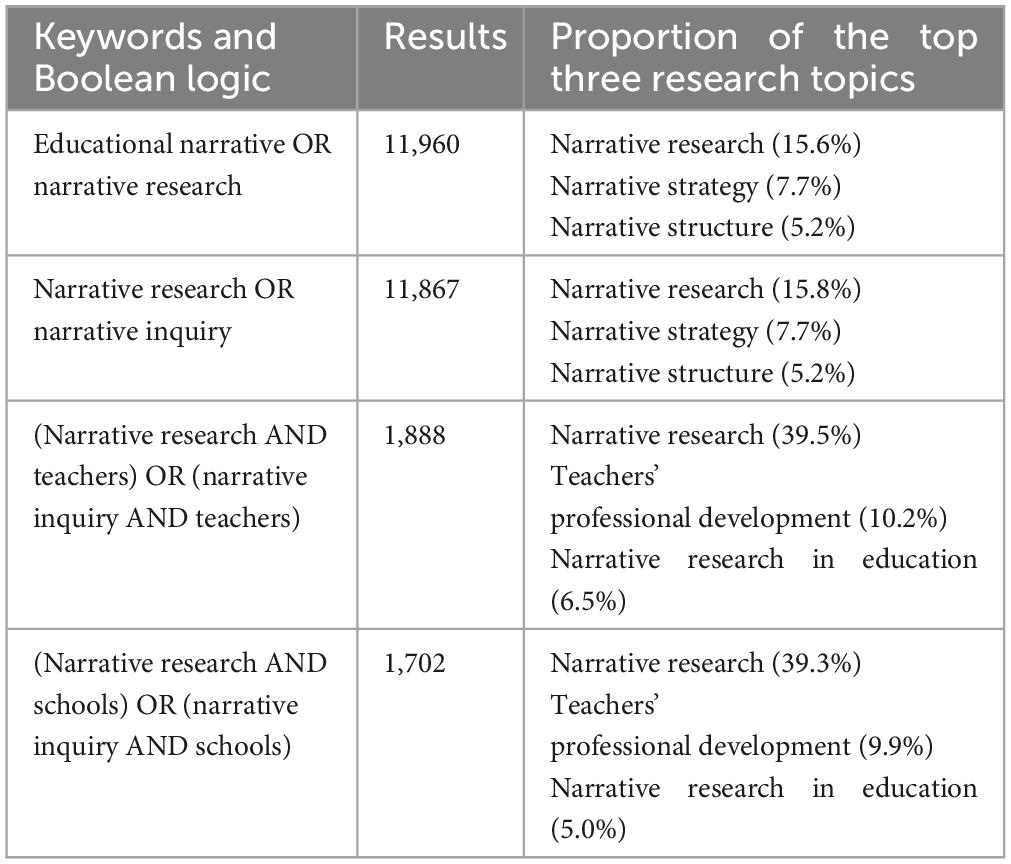

We used different keywords to search Chinese graduate students’ theses and dissertations in the biggest Chinese academic database: China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). Table 2 captures our keywords with Boolean logic, results, and proportion of the top three research topics with the respective categories.

To narrow the scope of our search in the education field, we also tried the keywords “Narrative Research in Education (教育叙事研究)” and “Narrative Inquiry in Education” (教育叙事探究) with the Boolean logic of “OR” and got 507 results. The research topics include: (1) teachers’ professional development, (2) teachers’ narratives, and (3) teachers’ practical knowledge. The following discussion is based solely on these 507 results from one database for Chinese theses and dissertations, which may not include all theses and dissertations in China. Among these 507 results, the earliest thesis on narrative research was posted in 2003 from South China Normal University. The majority of these theses and dissertations use the title of “narrative research” (叙事研究) or “narrative research in education” (教育叙事研究), which accounts for 70.6% of all retrieved articles. The research topics include: (1) teachers’ professional development, (2) teachers’ narratives, and (3) teachers’ practical knowledge. Therefore, narrative inquiry was widely used in Chinese graduate students’ theses and dissertations mostly in the field of teacher education. Moreover, it is noted that from 2010, the number of empirical studies using narrative inquiry has increased significantly, which might be a positive outcome from the nation-wide discussion of the methodological and theoretical aspects of narrative inquiry in Chinese academia between 2000 and 2010. Furthermore, students majored in curriculum studies and pedagogy in China most frequently use narrative inquiry as their research methodology, taking up 25% of the whole population of the retrieved articles, followed by educational foundation (14%), early childhood education (5.1%), and educational technology (4.15%).

English literature

There is a reasonably extensive narrative inquiry related English-based literature on and about China. The present study is focused on China-based inquiry and does not comprehensively review the English literature. Nevertheless, there are strong related threads that may reasonably be thought to affect the Chinese landscape of narrative inquiry. The following identifies a literature contextualized in China divided into two parts: English Literature on narrative inquiry Contextualized in China and our own Canada-China partnership Project discussed under the heading narrative inquiry for reciprocal learning in teacher education and school education between Canada and China.

English literature on narrative inquiry contextualized in China

The main English literature strand is on international cross-cultural educational programs. The purpose of this research is often to unpack students’ lived experience in a different country and culture. For example, an US-China exchange program supported and hosted by the University of Houston’s Asian American Study Center has generated a narrative inquiry related literature. The center is directed by Dr. Yali Zou who, with Dr. Cheryl Craig and Dr. Gayle Curtis, studied and described the exchange program (Craig et al., 2019). They state, “the purpose of the Center was to generate knowledge and cultural understandings and to increase awareness and foster appreciation of the Asian and Asian American experience in the US and abroad” (p. 209). Surrounding this program, many studies have been done with the adoption of narrative inquiry as the methodology. Studies done by Center faculty and graduate students demonstrate deep understanding of education in China with consideration of cultural complexities. Altogether the cross-cultural learning of 43 American doctoral student participants was documented for the travel study abroad program to China. Moreover, Zou et al. (2016) explored one principal, one deputy principal, and three teachers in a Chinese elementary school to reflect what the West could learn from the East. In addition, Craig et al. (2015a) investigated student journal writing as a way to know culture in the Center’s study abroad program to China. Furthermore, Craig et al. (2015b) studied three Chinese principalships. Craig (2020a) used a Chinese metaphor—fish jumps over the dragon gate—to make sense of her career trajectory and to demonstrate the importance of the “best loved self,” a concept Craig proposed on the basis of her research and personal experiences (Craig, 2020b; Li and Craig, 2023a).

Several important narrative inquiry studies emerged from the Center and doctoral student mentoring, most in close association with Craig. Libo Zhong undertook a narrative inquiry into the cultivation of self and identity of three novice teachers in Chinese colleges through the evolution of an online knowledge community (Li et al., 2017; Zhong and Craig, 2020) after his supervisor Xiaohong Yang, the first International Studies Association for Teachers and Teaching (ISATT) Chinese member, died before retirement (Li and Craig, 2023b). In addition, Jing Li, currently Post-Doctoral Fellow at East Normal University, received an ISATT research grant to support her narrative work with Xiaohong Yang in teacher education in China (Li et al., 2017, 2019). Gang Zhu, currently Associate Professor at East China Normal University, adopted narrative inquiry to explore Chinese teachers’ attrition (Zhu et al., 2023).

It is noted that in these narrative inquiry studies, several characteristics can be summarized. First, a sense of continuity is developed throughout Craig, Zou, and Curti’s studies. Their narrative inquiry does not start from scratch. The “continuity” and “situation” (Dewey, 1938) in the study abroad program contribute to the quality of lived experience expressed in their narrative inquiries and those who have participated in their study abroad program in the past decade. Such continuity is also reflected in Zhong and Craig’s (2020) narrative inquiry when Zhong, as Xiaohong Yang’s student, was able to carry on Yang’s legacy following his death and make a narrative inquiry mentored by Craig. Second, in their narrative inquiries, they effectively showcase how to work with field texts by adopting the idea of “broadening,” “burrowing,” “storying,” “re-storying,” and “fictionization described above.” Third, in these studies (Craig et al., 2019), a great deal of cultural and historical consideration enabled them to “think narratively” (Xu and Connelly, 2009). Craig et al. (2019) elaborated the importance of cultural and historical considerations in narrative inquiry by writing that “narrative inquirers suspend judgement… rather than… adopting a critical framework where what the researcher knows trumps what the teachers know” (p. 12).

In addition to study-abroad programs, there are many other English narrative inquiry studies contextualized in China. The main topics that stand out are: (1) teachers’ identity construction (e.g., He, 2002; Liu and Xu, 2011; Jiang et al., 2013; Liu, 2014; Yuan and Lee, 2016; Ye and Edwards, 2017; Zhu, 2017; Leigh, 2019; Li and Craig, 2019; Sun and Trent, 2020; Teng, 2020; Zhu et al., 2020; Ding and Curtis, 2021; Li, 2022), (2) school-base leadership (e.g., Li et al., 2019; Wei and Xing, 2022), and (3) teacher knowledge (e.g., Xu and Liu, 2009; Chen et al., 2017). Teachers’ identity construction is the most popular topic. For example, He (2002) examined the identity development of three Chinese women teachers who engaged in Eastern and Western cultures. Liu and Xu (2011) investigated how an English as a foreign language (EFL) teacher negotiated her identity in a Chinese university. Similarly, Leigh (2019) used narrative inquiry and positioning theory to explore eight EFL teachers’ professional identity in Shenzhen, China. Around the topic of school-based leadership, Wei and Xing (2022) explored Chinese university leader’s intercultural competence in leadership. Zhou (2011), studied Chinese EFL teachers’ intercultural competence. Moreover, Li et al. (2019) explored a teacher-principal’s best-loved self in an online teacher community in China. In terms of teacher knowledge, Xu and Liu (2009) explored teachers’ assessments of knowledge and practice through a narrative inquiry of a college EFL teacher in China. Chen et al. (2017) studied Chinese teachers’ ethical dimension of their practical knowledge while thinking and acting in dilemmatic spaces. The methods of data analysis varied among these narrative studies. Many adopt coding and/or a thematic approach to data analysis. Others employ broadening, burrowing, storying and re-storying, and fictionalization to transform field texts into research texts.

Our literature review reveals that much of the research using narrative inquiry in China is related to international cross-cultural studies. This leads us to believe that cross-cultural and international contexts greatly contribute to the development and spread of narrative inquiry. Conversely, narrative inquiry is making a positive contribution to international and cross-cultural studies with enhanced understanding and appreciation of different cultures. The Canada-China partnership Grant Project discussed below is an exemplar.

Narrative inquiry for reciprocal learning in teacher education and school education between Canada and China

The opening up of China in 1978 coincided with an expanding literature on cross-cultural educational programs in which the idea of narrative inquiry has played an important role. The most extensive initiative is the multi-year Canada-China partnership project referred to as reciprocal learning in teacher education and school education between Canada and China, directed by Xu and Connelly (2013–2020). Among other publications, the Project produced an ongoing Palgrave Macmillan book series, co-edited by Connelly and Xu, currently consisting of 12 published and three forthcoming books. Reviews have appeared in Frontiers of education in China (see Buckner, 2020; Hayhoe, 2020; Liao, 2020; Westbury, 2020), the Canadian journal of education (see Chi C., 2020), and multicultural perspectives (see Zhou, 2023). These books are built around classroom teaching, teachers, newcomers, teacher education, and school education, and focus on reciprocal learning among cultures (e.g., Xu, 2017; Huang, 2018; Elkord, 2019; Chi C., 2020; Craig, 2020b; Bu, 2021; Khoo, 2022). The program grew out of Xu’s narrative inquiry-based study (Xu et al., 2007; Xu, 2011, 2017) of Chinese families new to Canada that was contextualized in Connelly’s longitudinal school-based project. The program is built on two essential components: (1) the pre-service teacher education reciprocal learning program (RLP) (Xu et al., 2015; Xu, 2019a,b), and (2) the Canada-China Sister School Network (SSN) (Connelly and Xu, 2019; Xu and Connelly, 2022). The two key narrative inquiry features of this program are the emphasis on understanding school and teacher education practices as narrative extensions of cultural histories, and the focus on collaborative working experience in contrast, for example, to identifying cultural similarities and differences. This latter feature means that this work is not, strictly speaking, demonstrative of China narrative inquiry research. The partnership work is focused on the in between space as Canadian and Chinese educators work together such that partnership work undertaken and published in China is seen as shaped by Canadian thought; and work undertaken and published in Canada is seen as shaped by Chinese thought. For example, Xu et al. (2015) discuss the pedagogical implications for both Canadian and Chinese teacher candidates who were engaged in West-East reciprocal learning while working with people in cultures different from their own with an attitude of mutual respect and appreciation. The idea of reciprocal learning as collaborative partnership (Xu and Connelly, 2015; Connelly and Xu, 2019), one of the main concepts of this work, means that research focuses on the ways people integrate their experience during culturally collaborative work.

Many Canadian and Chinese master’s and doctoral students involved in the partnership program adopted narrative inquiry for their studies. For instance, Yishin Khoo’s dissertation examines how Toronto teachers developed citizenship education skills in globalized settings working with Shanghai partners (Khoo, 2018). Khoo’s dissertation, recognized by the Canadian Association for Teacher Education (CATE) Dissertation Award, is now a published book in the Palgrave Macmillan book series (Khoo, 2022). This study emphasizes the role of narrative inquiry in fostering collaborative, reciprocal learning communities. It is noted that the Shanghai-Toronto Sister School Project featured two important concepts guiding cross-cultural activities: (1) reciprocal learning as collaborative partnership conceptualized in narrative terms (Xu and Connelly, 2017; Connelly and Xu, 2019), and (2) The life-practice (生命实践) educology proposed and implemented by Professor Lan Ye with her East China Normal University (ECNU) team (Ye, 2020; Deng and Xu, 2023). ECNU team member Professor Yuhua Bu authored another book in the series, about the Chinese perspective of the partnership’s narrative inquiry-based collaboration in which she reviewed the Canada-China partnership work from the point of view of Chinese cultural and research history and tradition (Bu, 2021). She also published an article with Xiao Han on successful university and school collaboration for enhanced teacher development through the New Basic Education in China (Bu and Han, 2019).

Ju Huang from Southwest University made a narrative inquiry into four Chinese teacher candidates’ cross-cultural learning in Canada through the RLP. Her dissertation (Huang, 2017), published in English (Huang, 2018) and Chinese (Huang, 2023), offers insights into the transformative impact of international and intercultural learning experiences on Chinese teachers’ professional identity and pedagogy. Minghua Wang conducted a narrative study for her master’s thesis on the international cross-cultural experiences of Canadian teacher candidates in China through the RLP, highlighting the profound influence of international and cross-cultural experiences on Canadian teacher candidates’ global competencies and perspectives (Wang, 2015). Potocek (2016), who participated in the RLP first as a pre-service teacher in 2013 and then as a master’s student in 2015, made a narrative inquiry into Language immersion in ESL and EFL classes for his master’s thesis. Yuhan Deng examined Canadian teacher candidates’ experiences in learning the Chinese language and their cross-cultural immersion through the RLP/Mitacs internship in China, revealing how this international intercultural learning experience fostered the Canadian pre-service teachers’ understanding of newcomer English-language learners with enhanced pedagogical skills (Deng, 2019). Building on her master’s thesis, Deng currently is doing her doctoral dissertation to make a narrative inquiry into Canadian novice teacher development by following up with her master’s thesis research participants who are now novice teachers teaching in Canada or abroad. Haojun Guo, recently completed her doctoral narrative thesis, exploring the translanguaging and bilingual/cultural experiences of young visiting Chinese students in Windsor, Canada, as part of the partnership project (Guo, 2023), and is now an assistant professor at Nanjing Normal University. Chenkai Chi’s doctoral research focuses on his narrative wonder about the Canadian generalist teaching model, the Chinese specialist teaching model, and the strengths in each for reciprocal learning across educational cultures. As a key research assistant for the partnership in Chongqing-Windsor Sister School Network, Chi has done extensive fieldwork at Windsor TL Public School and Chongqing RH Primary School. His dissertation research won the Ontario Graduate Scholarship (OGS) twice and a SSHRC Doctoral Fellowship award. Chi’s preliminary dissertation findings can be found in the conversation (Chi and Xu, 2023). In addition to these formal studies, the teacher education reciprocal learning program sponsored many Chinese and Canadian teacher candidates in a narrative inquiry conceptualized international, cross-cultural and reciprocal learning experience. Students participated in a wide-ranging variety of narrative inquiry-based exercises. Details are available in consultation with this paper’s senior author who directed this aspect of the program beginning several years prior to the initiation of the partnership project. In addition, master’s and doctoral research associated with the teacher education research team led by Dr. Yibing Liu at the Southwest University and in association with Shijing Xu at the University of Windsor has been influenced by the partnership’s narrative inquiry focus (see, Jia, 2016; Zhao, 2016; Shi, 2017; Luo, 2019).

Student theses have been part of the broader narrative inquiry within the SSHRC partnership grant project, which emphasizes two key aspects: initiating an inquiry with a practical puzzle rather than a purely theoretical perspective, and the importance of a trustworthy collaborative relation between researchers and participants throughout the reciprocal learning research process. The partnership created a West-East reciprocal learning research community in which master’s and doctoral students were engaged deeply in the large project as both research assistants and learners before initiating their own research. This approach has allowed them to acquire essential skills in cross-cultural school-based research and develop and establish a strong rapport with potential participants with a narrative sense of inquiry and ethical considerations through classroom observations in sister schools and monthly Skype meetings between Canadian and Chinee sister school pairs as well as interactions with Chinese and Canadian teacher candidates in the teacher education reciprocal learning program (RLP).

In addition, this partnership also offered collaborative research opportunities for other Canadian professors who were interested in international cross-cultural work. For example, Parker et al. (2022) explore the perspectives of Chinese preservice teachers on mentoring relationships with their Canadian mentors through the RLP. The study finds that the candidates valued the relationships they formed with their mentors, which helped them to develop cultural competence and gain a deeper understanding of Canadian education. Holloway et al. (2023) explore the experiences of Chinese and Canadian preservice teachers through the RLP that created face-to-face guided dialogs between the two groups. The findings suggest that the RLP can provide valuable opportunities for pre-service teachers to engage in meaningful cross-cultural exchanges and to develop the cultural and global competence needed to work effectively in diverse classrooms.

Canadian and Chinese RLP preservice teacher participants have also been encouraged in writing for publications emanating from the partnership project. For example, guided by the framework of narrative inquiry with the concept of “reciprocal learning as collaborative partnership,” pre-service teachers, school principals and teachers, and graduate students are engaged as collaborative chapter authors with university researchers in three forthcoming Palgrave Macmillan books featuring teacher education research through the RLP (Xu et al., forthcoming a), language education research (Xu et al., forthcoming b) and general education and culture research (Khoo et al., forthcoming) through the Canada-China partnership.

Additional publication sources covering the work of the project’s International Advisory Committee members, faculty, school board members and student participants are found in special issues of teachers and teaching theory and practice (TTTP), Frontiers education in China (Volume 12, issue 2), and journal of teaching and learning (JTL). Because the partnership project was defined by two quite different cultures, and because of the large number of research and school-based professional participants, readers will find a variety of working interpretations of narrative inquiry in the research. On the one hand, the project is directed and governed by a reasonably well-defined notion of narrative inquiry. On the other hand, participants coming from quite different methodological backgrounds as, for example, is the case in mathematics education, undertake adaptations of narrative inquiry compatible with their working understandings of methodology. We believe the process underway in these adaptations is akin to the adaptations that take place in reciprocal learning more generally. The authors of this article welcome comments on this matter.

Discussion

The previous sections review and demonstrate the academic and professional interest in, and uses of, narrative inquiry in China. Some of the earliest work as mentioned in Ding’s 2007 workshop presentation focused on teacher narratives with the result that the construction of teacher narratives for research and for professional development purposes is important in China (Ding and Wang, 2010). Considerable work has been done by Chinese graduate students in their theses and dissertations. In addition, it is seen how narrative inquiry contributes to international cross-cultural studies in the Chinese educational context, particularly in study abroad programs. The review concludes with an account of how narrative inquiry shaped the Canada-China school-based partnership in which university and school educators and students in both China and the West actively engaged in building an international intercultural multidimensional bridge for West-East reciprocal learning. In this initiative Canadian and Chinese faculty, students, schoolteachers and school administrators were committed to a common long-term collaborative narrative inquiry study. In the following section, we discuss current matters that have the potential to shape the future of narrative inquiry in China and, indeed, globally.

Narrative inquiry and narrative research

Narrative inquiry and narrative research are often used in an exchangeable way in China. Bu (2021) notes that the first article on narrative inquiry listed in the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, 中国知网) published by Liu (2002) did not distinguish between tanjiu (探究 inquiry) and yanjiu (研究 research) with the result that most researchers use the term “narrative research.” However, some argue that there are fundamental differences between inquiry and research. Chen and Zhao (2013) point out the difference but do not provide substantial explanation. Sun and Jin (2015) analyze western scholars’ perspectives on narrative inquiry and use Connelly and Clandinin’s notion of a three-dimensional life space: temporality, sociality, and place to articulate the idea that narrative inquiry is contextualized and situated within a three-dimensional life space.

Following the 2007 Shanghai Workshop on narrative inquiry for teaching and research, Michael Connelly and Shijing Xu’s presentations were published, in Chinese, in The Peking University Review (Xu and Connelly, 2008a) and in a methodology book edited by Professor Xiangming Chen (Xu and Connelly, 2008b) in which Xu translated narrative inquiry into 叙事探究, putting an emphasis on “inquiry” (tanjiu). Using the idea of the three-dimensional life space, these publications discussed what a narrative inquirer would do and how this might differ from other more traditional forms of research. This notion has been further developed in writings contextualized by the Canada-China partnership project. Xu and Connelly (2009) write that narrative inquiry adopts a bottom-up way to see a phenomenon, not a top-bottom theory-loaded way. The partnership was developed with a sense of inquiry, which pervades the concept reciprocal learning as collaborative partnership. This idea is elaborated in Connelly and Xu’s (2020) Oxford Encyclopedia entry on Schwab’s theory of the practical and in its place in the idea of reciprocal learning. Schwab, like Dewey before him, argued that the English based research literature was conceptually and theoretically driven and obscured the nuances of practice. Schwab’s writing on what he referred to as the practical provided a profoundly different, practical, starting point to inquiry. From this point of view the differences of tanjiu (inquiry 探究) and yanjiu (research 研究) lie in the starting point of an educational study. To be more specific, tanjiu uses Schwab’s Practical as the starting point to understand a phenomenon. Yanjiu uses the theoretic as the starting point for inquiry, as every student knows from advice given on the writing of a thesis proposal. Reid writes that the strength of theory is its capacity to “join a category and share in all properties conventionally associated with that category” (Reid, 1991, p. 3). We are open to different scholars’ understandings of tanjiu and yanjiu. We believe that tanjiu best captures the narrative idea of life space while recognizing that yanjiu opens the door to more reproducible theoretically guided studies. This distinction helps explain Yang’s (2016) puzzle: although more and more research articles have been published on teacher-student relationship, Yang claims not to know how to deal with teacher-student relationship. With the theoretic as the starting point, before inquiry, people often have a framework in their mind to guide them to listen to, see, and know what they want to know while overlooking or ignoring the nuances of different experiences lived by people due to different personal, social, cultural, historical, political and/or economic situations. By starting from the theoretic, teacher-student relationship may be clearly demonstrated and analyzed under certain frameworks, but the discussion of this topic may become increasingly stylized and abstract, thereby limiting understanding of what is happening at the personal-practical level. In effect there is a research trade-off. That is, researchers need to be aware of the distinction and consider possible consequences for their inquiry.

Methodological discussion of narrative inquiry

When narrative inquiry was first introduced into China, most concerns and discussions were on the theoretical and methodological aspects of narrative inquiry. During the Shanghai Workshop in 2007, the most intense discussions were around the place of theory in narrative inquiry and the construction of theory for narrative inquiry in China. Luo (2017) summarized four research models of narrative inquiry in China: (1) qualitative research model; (2) class lesson research model; (3) crucial education events model, and (4) autobiographical narratives model. Luo listed the steps followed in each model:

1. Qualitative research model steps: (1) set up a research question; (2) select research participants; (3) enter the research site; (4) collect data; (5) analyze collected data, and (6) write research articles or reports.

2. Class lesson research model steps: (1) class observation and analysis, and (2) action research

3. Crucial education events model steps: (1) present educational events; (2) point out the key to the educational events; (3) discuss “how to do,” and (4) discuss “why to do”

4. Autobiographical narratives steps: include autobiography, biography, memories, oral history, diary, letters, archives, and artifacts (p. 144).

In terms of historical and cultural aspects, narrative inquiry has its cultural complexities.

Luo (2017) argues that narrative research should create a new research discourse that is different from the quantitative research paradigm. He also emphasizes that more attention should be paid to localization of narrative inquiry by which he means the use of Chinese traditional knowledge on narrative to develop new theories to guide narrative inquiry in Chinese contexts. Such sentiments echo Liu’s (2021) argument that narrative research should not only simply borrow from the western research discourse but also be grounded in the Chinese traditional way of narrative. Zongjie Wu, professor at Zhejiang University and International Advisor on the Canada-China partnership grant project, holds a similar opinion that China has its own narrative system of thought with its special way of telling and retelling stories (Wu, 2011). Wu and Jiang (2009) called this special way of telling and retelling as Chun Qiu technique (春秋笔法), more specifically, Wei Yan Da Yi (微言大义), sublime words with deep meaning. Song (2011) also argues that the style of educational narrative in Chinese contexts should follow Wei Yan Da Yi.

Many Chinese scholars think that narrative inquiry should have clear guiding theory especially in data collection, analysis and interpretation. For example, Liu (2021) argues that narrative research in Chinese contexts often lacks theoretical guidance. This makes the data analysis in narrative research be reduced to reading comprehension that is simple understanding without consideration of social, cultural, and historical contexts. To be clear, without clear frameworks, different people with different lens can interpret differently, with which narrative inquiry receives a lot of criticism. Liu (2007) argues that most narrative research in China adopts grounded theory as a method of data analysis, and the final goal is to develop a theory. Niu (2005) believes that because narrative research often has no clear theoretical framework to guide the research, narrative research is often regarded as storytelling without research rigor.

Another important Chinese discussion around narrative inquiry is about the re-storying process. Sun and Chen (2009) argue that an important discussion of narrative research in Chinese contexts is whether the stories should be real or, when re-storying, people can create fictional stories. They argue that from western scholars’ perspectives, the stories should be real and cannot be fictional. However, Tian (2018) believes that fictional stories are acceptable in narrative research. Cai (2008) suggests that stories should be real but in order to re-story, it is acceptable to have some slight adjustment. However, he does not specify what slight adjustment means. Connelly and Clandinin (1990) proposed an interpretive tool for narrative inquiry: broadening, burrowing, storying and re-storying. To build on these tools, Clandinin et al. (2006) proposed a fourth tool: fictionalization. Craig (2013) suggests that “fictionalization allows the researcher to subtly shift circumstances to protect individuals when they become increasingly identifiable, and their relationships are potentially placed at risk in local situations” (p. 5). It is noted that one of the underlying assumptions of fictionalization is ethical protection of participants.

Compared to other topics found in the Chinese narrative inquiry literature, ethical considerations and protocols are rarely discussed. For the most part Chinese research institutions and agencies do not have strong ethical protocols. The situation contrasts sharply with Canadian and American human based research. Funding agencies such as the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) have developed extended research funding protocols in response to public equity issues. Still, there is growing interest in ethical matters in Chinese research. Sun and Jin (2015) argue that narrative inquirers in China should think ethically, and that ethical awareness should be throughout the whole research process including the ways of approaching participants, researcher-participant relationship, and data analysis. Wan (2019) highlights the importance of ethical caring for research participants, especially for teachers and student participants. Researchers need to think about whether the research is beneficial to the research participants. In our partnership work with Chinese colleagues, we emphasize the importance of the ethical consideration in narrative inquiry not only focusing on institutional ethical protocols but also paying attention to the moral aspect (Xu, 2015). The partnership emphasizes the term collaborator-collaborator relationship over the term researcher-participant relationship. Reciprocal learning as collaborative partnership is the guiding principle for the Canada-China partnership involving university researchers, graduate students, pre-service teachers, schoolteachers and administrators, students and families (Xu and Connelly, 2015; Connelly and Xu, 2019). The researcher-participant relationship in Canada-China partnership narrative inquiry is designed to be relational, ethical, moral and collaborative, in which both the researchers and the participants are learners in a reciprocal learning process through the narrative inquiry.

Confucius, the ancient Chinese philosopher and educator, advised, “三人行必有我师” (In a group of three people, there will be someone that I can learn from). Writing this article on narrative inquiry in China enabled us to reflect on and learn from narrative inquirers and researchers in China while sharing what we have done in our narrative inquiry.

Author’s note

SX: Canada Research Chair in international and intercultural reciprocal learning in education, and Professor, Faculty of Education, University of Windsor. SX co-directed with MC the Canada-China Reciprocal Learning partnership grant project with narrative inquiry as the guiding methodology and developed the teacher education reciprocal learning program with Dr. Shijian Chen and his colleagues at Southwest University China.

MC: Professor Emeritus, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto, and Co-Director with SX of the SSHRC funded Canada-China Reciprocal Learning partnership grant project. MC holds an Honorary Doctorate from the Education University of Hong Kong and American Educational Research Association (AERA) and Canadian Society for the Study of Education (CSSE) lifetime achievement award in curriculum and teacher education.

CC: Ph.D. candidate at the Faculty of Education, University of Windsor, Canada. He holds two Ontario Graduate Scholarships, a SSHRC Doctoral Fellowship, and is a Graduate Research Assistant in Xu and Connelly’s (2013–2020) SSHRC partnership grant project. He studies West-East reciprocal learning between elementary education generalist and specialist teaching models using narrative inquiry methodology.

Author contributions

SX: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The work reported herein is supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada Partnership Grants Program (Grant 895-2012-1011) and Canada Research Chair Program. This work is also supported by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada Doctoral Fellowship and Ontario Graduate Scholarship.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Editor-in-Chief SP and the Associate Editor CC, for the opportunity to write this article on narrative inquiry in China. We greatly appreciate all the educators, teachers, graduate students and schoolteachers that we have met or worked with, who are interested in narrative inquiry and publish their work to share their thoughts, perspectives and understanding of narrative inquiry. We are very grateful to university and school educators in our Chinese and Canadian partners with whom we have engaged in the West-East reciprocal learning in teacher education and school education. We also find it a reciprocal learning experience for us in reviewing the narrative work published in Chinese and/or English as well as in collaboratively writing this article. The University of Windsor sits on the traditional territory of the Three Fires Confederacy of First Nations, which includes the Ojibwa, the Odawa, and the Potawatomi. We respect the longstanding relationships with First Nations people in this place in the 100-mile Windsor-Essex peninsula and the straits—les détroits—of Detroit. We wish to acknowledge this land on which the University of Toronto operates. For thousands of years it has been the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and the Mississaugas of the Credit. Today, this meeting place is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island and we are grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ http://blog.cersp.com/index/1002266.jspx

- ^ Translated from Chen (2021) Chinese text: 由康纳利和克兰迪宁开创的叙事探究 (narrative inquiry) 本来就有行动和改变的潜力。然而,这种路径自从 20 世纪 90 年代引入我国后,逐渐变得客观、中立起来,成为更具科学主义意义的“叙事研究”。” (p. 52)

References

Bai, F. (2020).  [Educational narrative becomes the internal driving force of teachers’ growth].

[Educational narrative becomes the internal driving force of teachers’ growth].  Sci. Consult. 5, 49–51.

Sci. Consult. 5, 49–51.

Bu, Y. (ed.) (2021). “Narrative inquiry into reciprocal learning between Canada-China sister schools: A Chinese perspective,” in Palgrave Macmillan book series: Intercultural reciprocal learning in Chinese and western education, eds M. Connelly and S. Xu (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

Bu, Y., and Han, X. (2019). Promoting the development of backbone teachers through university-school collaborative research: The case of new basic education (NBE) reform in China. Teach. Teach. 25, 200–219. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2019.1568977

Buckner, E. (2020). Cross-cultural schooling experiences of Arab newcomer students: A journey in transition between the East and the West. Front. Educ. China 15:530–532. doi: 10.1007/s11516-020-0023-7

Cai, C. (2008).  [Why “narrative” and “story” can be called “research”: On the basic theoretical issues of educational narrative research].

[Why “narrative” and “story” can be called “research”: On the basic theoretical issues of educational narrative research].  J. Capital Norm. Univ. Soc. Sci. Edn 4, 125–130.

J. Capital Norm. Univ. Soc. Sci. Edn 4, 125–130.

Chen, F. B., and Zhao, K. (2013).  [Educational narrative research in my country: Current situation, hot issues and future trends].

[Educational narrative research in my country: Current situation, hot issues and future trends].  Educ. Daokan J. 1, 71–73.

Educ. Daokan J. 1, 71–73.

Chen, X. J. (2009).  [Practical exploration of educational narrative research in the training of backbone teachers in primary and secondary schools].

[Practical exploration of educational narrative research in the training of backbone teachers in primary and secondary schools].  Continue Educ. Res. 2, 124–126.

Continue Educ. Res. 2, 124–126.

Chen, X. M. (2021).  [From narrative inquiry to narrative action research].

[From narrative inquiry to narrative action research].  Educ. Innov. Talents 1, 50–56.

Educ. Innov. Talents 1, 50–56.

Chen, X., Wei, G., and Jiang, S. (2017). The ethical dimension of teacher practical knowledge: A narrative inquiry into Chinese teachers’ thinking and actions in dilemmatic spaces. J. Curr. Stud. 49, 518–541. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2016.1263895

Chi, C. (2020). Book review: Cross-cultural schooling experiences of Chinese immigrant families: In search of home in times of transition. Can. J. Educ. 43, 11–14.

Chi, C., and Xu, S. (2023). How Canadian and Chinese teachers’ reciprocal learning can benefit students. The Conversation. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/how-canadian-and-chinese-teachers-reciprocal-learning-can-benefit-students-205733 (accessed November 5, 2023).

Chi, X. (2020). “Cross-cultural experiences of Chinese immigrant mothers in Canada: Challenges and opportunities for schooling,” in Palgrave Macmillan book series: Intercultural reciprocal learning in Chinese and Western education, eds M. Connelly and S. Xu (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Clandinin, D. J., Huber, J., Huber, M., Murphy, M. S., Orr, A. M., Pearce, M., et al. (2006). Composing diverse identities: Narrative inquiries into the interwoven lives of children and teachers. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203012468

Connelly, F. M., and Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educ. Res. 19, 2–14.

Connelly, F. M., and Clandinin, D. J. (2006). “Narrative inquiry,” in Complementary methods for research in education, 3rd Edn, eds J. L. Green, G. Camilli, and P. Elmore (American Educational Research Association), 477–488.

Connelly, F. M., and Xu, S. (2019). Reciprocal learning in the partnership project: From knowing to doing in comparative research models. Teach. Teach. 25, 627–646. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2019.1601077

Connelly, M., and Xu, S. (2020). “Reciprocal learning as a comparative education model and as an exemplar of Schwab’s the practical in curriculum inquiry,” in Oxford research encyclopedia of education, eds L. Sokal and J. Katz (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1161

Craig, C. J. (2013). Opportunities and challenges in representing narrative inquiries digitally. Teach. College Record 115, 1–45. doi: 10.1177/016146811311500405

Craig, C. J. (2020a). Fish jumps over the dragon gate: An eastern image of a western scholar’s career trajectory. Res. Papers Educ. 35, 722–745. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2019.1633556

Craig, C. J. (2020b). “Curriculum making, reciprocal learning, and the best-loved self,” in Palgrave Macmillan book series: Intercultural reciprocal learning in Chinese and Western education, eds M. Connelly and S. Xu (London: Palgrave MacMillan).

Craig, C. J., Zou, Y., and Curtis, G. (2019). Moving from arrogance to acceptance: Narratively shifting human perceptions through a China study abroad programme. Pedagogies Int. J. 14, 206–228. doi: 10.1080/1554480X.2019.1625271

Craig, C. J., Zou, Y., and Poimbeauf, R. (2015a). Journal writing as a way to know culture: Insights from a travel study abroad program. Teach. Teach. 21, 472–489. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2014.968894

Craig, C. J., Zou, Y., and Poimbeauf, R. P. (2015b). A narrative inquiry into schooling in China: Three images of the principalship. J. Curr. Stud. 47, 141–169. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2014.957243

Deng, Y. (2019). Chinese as a foreign language: A narrative inquiry into Canadian teachers Reciprocal Learning in China. Ph. D Thesis. Windsor, ON: University of Windsor.

Deng, Y., and Xu, S. (2023). Review of [Life-practice educology: A contemporary Chinese theory of Education]. Can. J. Educ. 45, 10–12. doi: 10.53967/cje-rce.5921

Ding, F., and Curtis, F. (2021). ‘I feel lost and somehow messy’: A narrative inquiry into the identity struggle of a first-year university student. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 40, 1146–1160. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1804333

Ding, G. (2008c).  [Voices and experiences: Narrative inquiry in education].

[Voices and experiences: Narrative inquiry in education].  Beijing: Educational Science Publishing House.

Beijing: Educational Science Publishing House.

Ding, G. (2009).  [Narrative paradigm and historical perception: a methodological dimension in educational history research].

[Narrative paradigm and historical perception: a methodological dimension in educational history research].  Educ. Res. 5, 2–6.

Educ. Res. 5, 2–6.

Ding, G., and Wang, Z. (2010).  [Narrative inquiry in teaching and research].

[Narrative inquiry in teaching and research].  Guilin: Gaungxi Normal University Press.

Guilin: Gaungxi Normal University Press.

Ding, L. L. (2009).  [Literature review of domestic educational narrative research].

[Literature review of domestic educational narrative research].  Heilongjiang Chronicles 17, 134–138.

Heilongjiang Chronicles 17, 134–138.

Ding, S. (2005).  [The variation and countermeasures of Narrative Research in China: How to carry out educational narrative research].

[The variation and countermeasures of Narrative Research in China: How to carry out educational narrative research].  J. Ideol. Theoret. Educ. 5, 49–52.

J. Ideol. Theoret. Educ. 5, 49–52.

Dong, C. H. (2005).  [An interpretation of the educational narrative method: Take “an experience and reflection on organizing a class competition” as an example].

[An interpretation of the educational narrative method: Take “an experience and reflection on organizing a class competition” as an example].  Theory Pract. Educ. 13, 60–62.

Theory Pract. Educ. 13, 60–62.

Dong, M. Y., and Jin, L. X. (2009).  [The search for educational research paradigm: Reflections on the research fever of educational narratives].

[The search for educational research paradigm: Reflections on the research fever of educational narratives].  Mod. Univ. Educ. 2, 1–5.

Mod. Univ. Educ. 2, 1–5.

Elkord, N. (2019). “Cross-cultural schooling experiences of Arab newcomer students: A journey in transition between the East and the West,” in Palgrave Macmillan book series: Intercultural reciprocal learning in Chinese and Western education, eds M. Connelly and S. Xu (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

Eng, B. (2021). “Personal narratives of teacher knowledge: Crossing cultures, crossing identities,” in Palgrave Macmillan book series: Intercultural reciprocal learning in Chinese and Western education, eds M. Connelly and S. Xu (London: Palgrave MacMillan).

Fan, W. (2020).  [Educational narrative research: An effective path to leading teachers’ professional growth].

[Educational narrative research: An effective path to leading teachers’ professional growth].  Sci. Consult. Educ. Res. 5, 26–28.

Sci. Consult. Educ. Res. 5, 26–28.

Fang, P. (2020).  [Analysis of the current situation of localization of educational narrative research in China].

[Analysis of the current situation of localization of educational narrative research in China].  J. Teach. Manag. 12, 16–19.

J. Teach. Manag. 12, 16–19.

Feng, P., and Liu, Z. J. (2020).  [The influence of educational narrative research on the professional development of college English teachers].

[The influence of educational narrative research on the professional development of college English teachers].  Mod. English 24, 118–120.

Mod. English 24, 118–120.

Fu, L. P. (2012).  [Educational narrative research: “Experience”, “problem” and “theory”].

[Educational narrative research: “Experience”, “problem” and “theory”].  J. Zhangzhou Teach. Coll. Philos. Soc. Sci. 26, 151–155.

J. Zhangzhou Teach. Coll. Philos. Soc. Sci. 26, 151–155.

Gao, W. H. (2020).  [Narrative research methodology and educational research: Features, contributions and limitations].

[Narrative research methodology and educational research: Features, contributions and limitations].  Explor. Educ. Dev. 40, 24–31.

Explor. Educ. Dev. 40, 24–31.

Guo, H. (2023). Translanguaging and bi-lingual/cultural acquisition: A narrative inquiry into young Chinese visiting students’ international and cross-cultural experiences between Canada and China. Ph. D Thesis. Windsor, ON: University of Windsor.

Hayhoe, R. (2020). Book series: Intercultural reciprocal learning in Chinese and Western education. Front. Educ. China 15:526–529. doi: 10.1007/s11516-020-0022-8

He, M. F. (2002). A narrative inquiry of cross-cultural lives: Lives in China. J. Curr. Stud. 34, 301–321. doi: 10.1080/00220270110108196

Holloway, S. M., Xu, S., and Ma, S. (2023). Chinese and Canadian preservice teachers in face-to-face dialogues: Situating teaching in cultural practices for West-East Reciprocal Learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 122:103930. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103930

Hu, Y. H., Zhou, D. S., and Liang, H. (2013).  [Educational narrative research and its application in physical education research].

[Educational narrative research and its application in physical education research].  J. Xian Phys. Educ. Univ. 30, 370–374.

J. Xian Phys. Educ. Univ. 30, 370–374.

Huang, J. (2017). A narrative inquiry into Chinese pre-service teacher education and induction in Southwest China through cross-cultural teacher development. Ph. D. Thesis. Windsor, ON: University of Windsor.

Huang, J. (2018). “Pre-service teacher education and induction in Southwest China: A narrative inquiry through cross-cultural teacher development,” in Palgrave Macmillan book series: Intercultural reciprocal learning in Chinese and Western education, eds M. Connelly and S. Xu (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

Huang, J. (2023).  [Narrative inquiry into teachers’ cross-cultural development under the perspective of reciprocal learning].

[Narrative inquiry into teachers’ cross-cultural development under the perspective of reciprocal learning].  Beijing: Science Press.

Beijing: Science Press.

Jia, F. (2016). Research on free normal students’ teaching ability from the perspective of cross-cultural learning–A case study of normal students exchange between China and Canada. [ ] Ph. D Thesis. Chongqing: Southwest University.

] Ph. D Thesis. Chongqing: Southwest University.

Jiang, L. (2012). The shadow of history: Educational memories of a generation of female intellectuals.  Beijing: Educational Science Press.

Beijing: Educational Science Press.

Jiang, Y., Min, H., Chen, Y., and Gong, Z. (2013). “A narrative inquiry into professional identity construction of university EFL teachers in China: A case study of three teachers based in community of practice,” in Proceedings of the 2013 12th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET), (Antalya: IEEE), 1–8.

Ju, Y. (2004).  [Approaching teachers’ life space: A narrative inquiry into the theory of teachers’ personal practice.]

[Approaching teachers’ life space: A narrative inquiry into the theory of teachers’ personal practice.]  Shanghai: Fudan University Press.

Shanghai: Fudan University Press.

Ju, Y. (2007).  [“Narrative inquiry focuses more on sophisticated lived experience,”] in

[“Narrative inquiry focuses more on sophisticated lived experience,”] in  [Narrative inquiry in teaching and research],

[Narrative inquiry in teaching and research],  eds G. Ding and Z. Wang (Guilin: Gaungxi Normal University Press).

eds G. Ding and Z. Wang (Guilin: Gaungxi Normal University Press).

Khoo, Y. (2018). River flowing and fire burning: A Narrative Inquiry into a teacher’s experience of learning to educate for citizenship — from the Local to the Global — through a shifting Canada-China Inter-School Reciprocal professional learning landscape. Ph. D Thesis. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto.

Khoo, Y. (2022). Becoming globally competent through inter-school reciprocal learning partnerships: An inquiry into Canadian and Chinese teachers’ narratives. J. Teach. Educ. 73, 110–122. doi: 10.1177/002248712110423

Khoo, Y. Connelly, M. F., and Xu, S. J. (eds) (forthcoming). “West-East reciprocal learning from a Canada-China sister school network: Stories for hope,” in Palgrave Macmillan book series: Intercultural reciprocal learning in Chinese and Western education, eds M. Connelly and S. Xu (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

Lau, C. K. (2021). “Life and learning between Hong Kong and Toronto: An intercultural narrative inquiry,” in Palgrave Macmillan book series: Intercultural reciprocal learning in Chinese and Western education, eds M. Connelly and S. Xu (London: Palgrave MacMillan).

Leigh, L. (2019). “Of course I have changed!”: A narrative inquiry of foreign teachers’ professional identities in Shenzhen, China. Teach. Teach. Educ. 86:102905. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.102905

Li, C. J., and Sun, P. P. (2011).  [A review of educational narrative research].

[A review of educational narrative research].  Contemp. Educ. Cult. 3, 1–6.

Contemp. Educ. Cult. 3, 1–6.

Li, J. (2010).  [A review of educational narrative research].

[A review of educational narrative research].  Shanxi Norm. Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Edn 37, 145–149.

Shanxi Norm. Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Edn 37, 145–149.

Li, J., and Craig, C. J. (2019). A narrative inquiry into a rural teacher’s emotions and identities in China: Through a teacher knowledge community lens. Teach. Teach. 25, 918–936. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2019.1652159

Li, J., and Craig, C. J. (2023a). A beginning teacher’s living of counter stories in a high-needs school in rural China. Res. Papers Educ. 38, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2021.1941215

Li, J., and Craig, C. J. (2023b). “Tribute to Xiaohong Yang,” in Teacher education in the wake of COVID-19: ISATT 40th Anniversary Yearbook, eds C. Craig, J. Mena, and R. Kane (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited), 71–72.

Li, J., Yang, X., and Craig, C. J. (2017). “Parallel stories: Teachers and facilitators in a transformative online teacher learning community,” in Search and research: Teacher education for contemporary Contexts, ed. J. Mena (Salamanca: ISATT), 1093–1100.

Li, J., Yang, X., and Craig, C. J. (2019). A narrative inquiry into the fostering of a teacher-principal’s best-loved self in an online teacher community in China. J. Educ. Teach. 45, 290–305. doi: 10.1080/09589236.2019.1599508

Li, W. (2022). Unpacking the complexities of teacher identity: Narratives of two Chinese teachers of English in China. Lang. Teach. Res. 26, 579–597. doi: 10.1177/1362168820910955

Li, X. (2009).  [Theoretical appeal of educational narrative—A study on meta-educational narrative].

[Theoretical appeal of educational narrative—A study on meta-educational narrative].  Shanghai Res. Educ. 7, 12–14.

Shanghai Res. Educ. 7, 12–14.

Liao, W. (2020). Pre-service teacher education and induction in Southwest China: A narrative inquiry through cross-cultural teacher development. Front. Educ. China 15:532–535. doi: 10.1007/s11516-020-0024-6

Liu, T. F. (2005).  [Educational narrative and teacher growth].

[Educational narrative and teacher growth].  J. Heibei Norm. Univ. Educ. Sci. Edn 6, 24–28.

J. Heibei Norm. Univ. Educ. Sci. Edn 6, 24–28.

Liu, W. (2014). Living with a Foreign Tongue: An autobiographical narrative inquiry into identity in a foreign language. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 60, 264–278. doi: 10.11575/ajer.v60i2.55803

Liu, X. H. (2021).  [How method is possible: The logic and path of new educational narrative research].

[How method is possible: The logic and path of new educational narrative research].  J. Educ. Sci. Hunan Normal Univ. 20, 17–23.

J. Educ. Sci. Hunan Normal Univ. 20, 17–23.

Liu, Y., and Xu, Y. (2011). Inclusion or exclusion?: A narrative inquiry of a language teacher’s identity experience in the ‘new work order’of competing pedagogies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 589–597. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.10.013