95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 05 January 2024

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1326515

Introduction: The increased stress, pressure, and organizational change draw attention to the importance of doing research on workplace stress and resources, as well as other sources of stress among university teachers. Based on the job demands-resources theory (JD-R theory) this paper investigates the workplace factors affecting the health and wellbeing of Central and Eastern European (CEE) academics. A further question is, what are the institutional factors that (could) improve or worsen their wellbeing, as well as how they are able to cope with the stress on an individual level.

Methods: For the analyses, seven focus group interviews were conducted with academics from nine higher education institutions in Hungary, Slovakia, Ukraine, Romania, and Serbia (N = 41).

Results: According to our results of the focus group interviews the most important workplace difficulties, challenges, and resources are related to teaching roles, interpersonal relationships, support by the management, and infrastructural conditions.

Discussion: Institutions can contribute to the wellbeing and health of the academics primarily by offering free or at least discounted participation in sports, cultural and leisure events, as well as mental health counseling, but it is important for these not to be self-serving (the colleagues from the university should not participate in the programs to make up for the missing audiences of the otherwise overfunded organizations of the institution) and haphazard: without a targeted health strategy, these are not sufficiently effective.

The situation of higher education as a workplace as well as that of the academics has changed significantly in recent decades. Expansion, diversity and the knowledge society brought dramatic changes in the lives of higher education institutions, including academics, after World War II (Aarrevaara et al., 2021). Earlier, compared to working in other fields, teaching at a university was considered to be a relatively stress-free, flexible, autonomous, and socially recognized profession. Teachers and colleagues were protected from many sources of workplace stress, such as uncertainty, work-related ambiguity, or low job control, but today this is no longer the typical case. The expectations (or needs) related to these roles and activities put strong pressure on the teachers, they are serious sources of stress that have a negative impact on their health, wellbeing (Bell et al., 2012; Kinman, 2014; Papp et al., 2021; Szigeti and Kovács, 2022). Thanks to various reforms in higher education (see Bologna Process in Europe, strong government-driven policies in the East-Asian territories, etc.), the position of teachers has also changed significantly. While they had been the key actors in higher education institutions, external stakeholders started to occupy important leadership positions in the institutions. Although teachers continued to enjoy freedom in their teaching and research, institutional management and external stakeholders increasingly monitored and controlled their performance. This change, and working in this new environment, has been associated with decreased job satisfaction and increased stress among teachers in many countries (Aarrevaara et al., 2021). Similar changes have taken place in recent years in several CEE countries, with Ukraine and Romania developing specific performance evaluation systems to assess the work of teachers, while in Hungary, all but five universities have been converted to private (foundation) status, with a share of teachers’ salaries determined by the results of a newly developed performance evaluation system (Pimenta et al., 2021).

In our study, we examine the workplace factors affecting the health and wellbeing of Central and Eastern European academics. Our main question is what difficulties, stressors the university teachers of the region have to deal with during their work, and what are the resources that contribute to their wellbeing and may also contribute to offset negative consequences related to stress. A further question is, what are the institutional factors that (could) improve or worsen their wellbeing, as well as how they are able to cope with the stress caused by the workplace on an individual level. The job demands-resources theory (JD-R theory) was used as a theoretical background to examine this issue. The JD-R theory is a theoretical framework that helps to explain and understand the relationship between workplace characteristics and employee performance and wellbeing. The theory is a revised form of the JD-R model, supplemented with personal resources. It classifies the workplace characteristics into two categories that are negatively correlated: (negative) work requirements and work-related resources which have a direct impact on the employee’s stress level, motivation, health problems, and numerous organizational outcomes. Job-demands, such as high workload, lack of support, limiting efficiency, different teacher roles, pressure on publication and grants, etc., exhaust the employee’s physical and psychological resources and drain their energy, cause additional fatigue, negatively affecting their wellbeing and performance, leading to emotional exhaustion and burnout. Workplace resources are the characteristics of the workplace that are necessary to achieve the work goals set, contribute to work enjoyment, motivation, and engagement (Bakker and Demerouti, 2014). Work resources contribute to the personal development and learning of the employee as intrinsic motivation and to achieving goals at an institutional level as extrinsic motivation (Han et al., 2020). Work requirements are inversely related to commitment to work. A high level of work requirements can lead to chronic stress, fatigue, and emotional exhaustion, which can reduce the commitment to work, and through this, job satisfaction (Johnson et al., 2005). One of the most important resources is social support, which is negatively correlated with emotional exhaustion and burnout among trainers (too), and contributes to job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Vigoda-Gadot and Talmud, 2010; Salami, 2011). Overall, academics who have more access to workplace resources (such as a supportive institution and colleagues) and resources needed for teaching are much more enthusiastic, engaged, and enjoy their work (Han et al., 2020).

Earlier research primarily took a psychological approach and examined psychological stress sources and resources, and showed their correlation with regard to work performance, workplace and psychological wellbeing, or even burnout (Moueleu Ngalagou et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020; Alqarni, 2021; Lei, 2022). But in our exploratory research, based on the JD-R theory difficulties and resources related to the work of the teachers were examined from a higher education research perspective and using a qualitative method (focus group interviews). Previous empirical works that utilized this theory applied the correlations of stress and resources primarily for different aspects of wellbeing. As the first step of our study, the sources of job-stress and the job-resources were identified utilizing the experiences of the teachers in the region under investigation, which influences their wellbeing according their perceptions. Related to the JD-R theory, the interviews also asked how academics cope with workplace stress on an individual level and how their higher education institution contributes or can contribute to this.

The validity of the JD-R theory and workplace stressors has been extensively studied among educators worldwide (see Kinman et al., 2006; Bell et al., 2012; Aziz and Quraishi, 2017; Han et al., 2020; Iyaji et al., 2020; Alqarni, 2021; Fetherston et al., 2021), but these have primarily addressed stress and resources in the context of wellbeing, job efficiency, satisfaction, etc., rather than institutional and individual opportunities and factors for coping with them. In these papers, there is little evidence of how university teachers cope with workplace stress at an individual level, or how their institution contributes to coping with workplace stress. Also, an important uniqueness of our research is that, in contrast to the most commonly used questionnaire survey and multivariate models, it is not investigated workplace stressors among teachers based on given options but rather inductively identify them by drawing on everyday individual experiences, perceptions and opinions, taking into account local specificities, and then compare them with JD-R theory and previous research findings. The reason for this is that the quantitative research mentioned above has been carried out in other countries with different economic, cultural and social situations and educational characteristics and is therefore not necessarily valid for the CEE context under study. In order to be able to investigate these relationships deductively in a large sample survey, it important to identify the experiences of job demands and resources among educators in the countries under study by exploring them at the individual level.

Going beyond theory, it was not only explored the perceived work-related stressors and resources among teachers at an individual level but also it was looked for possible solutions, good practices and opportunities that can help university staff at an institutional and individual level to cope effectively with the challenges they face in the workplace. Thus, our research has also explored how the HEIs under study can and do contribute to overcoming stress and thus increasing employees’ job satisfaction, effectiveness and wellbeing. In addition to the institutional level, it was looked at individual-level solutions, including the individual-level activities that can help reduce workplace stress and provide a basis for designing and implementing institutional-level programmes to enhance employee engagement and wellbeing. The wellbeing and health of the teachers is important not only from a personal perspective, but also from an organizational point of view, that is, when it comes to the institutions. Higher education is a labor-intensive industry that relies heavily on the skills and goodwill of the employees in order to ensure quality. The increased stress level of the employees can also lead to the institution not being able to function properly, because if its employees do not feel well, are too tired, listless, and undermotivated, it negatively affects the operation of the whole university/college as an organization (Bell et al., 2012; ChaaCha and Oosthuysen, 2023).

The geographical area (CEE) can be considered a novelty, as it is a region that contains several countries that have similar cultural roots and historical antecedents and are in a similar social-economic situation but at the same time, they have many peculiarities (Pusztai and Márkus, 2019). This topic has not yet been studied using this method in this region. Although a similar research has been conducted among young researchers in Hungary not long ago, it is not the same population as that of the teachers. The applied method is suitable for getting to know the characteristics and challenges of teaching work in the countries and institutions examined in a close-up, valid way, over a broad basis, based on the opinions and experiences of those affected, laying the foundation for further quantitative research that reveal correlations.

In the next part of our study, we will review the most important international research on higher education and academics’ situation over the past two decades. We will also discuss the findings on workplace stress sources and resources in academics’ work, which greatly influence their wellbeing, job satisfaction, commitment, and different work outcomes. The next chapter will present the research’s methodological background, followed by the most important results, discussion, and conclusions.

Several international comparative studies have looked at academia in recent decades. In the project of Changing Academic Profession in 2006, a study of academics in 19 countries worldwide was carried out, which did not include CEE countries. However, the European continuation of the research, “The Academic Profession in Europe-Responses to Societal Challenges” (EUROAC), included Poland and Romania from the region in 2007 to 2011. The comparative studies have reached similar conclusions: although the academic profession is subject to increasing expectations and pressures, these expectations are not a constraint on how academics perceive their situation and how they act. Of course, they have to respond to these challenges, but they have room for maneuver in how they interpret them and how they react (Höhle and Ulrich, 2013). The most important (negative) predictor of job satisfaction was administrative processes in almost all countries (Bentley et al., 2013). As a continuation of Changing Academic Profession 2006 (CAP), the Academic Profession in the Knowledge-Based Society (APIKS) research was carried out between 2019 and 2021 in 18 countries (CEE countries were not included), with two objectives defined by the editors in the synthesis volume: (1) Providing a conceptual overview about the knowledge society/economy and the role of higher education, and (2) a conceptual analysis about 18 higher education systems changing and developing in it (Aarrevaara et al., 2021). The volume presents the main findings of the research on a country-by-country basis. However, one of its main messages is that although the academic profession appears similar in many respects in the countries studied when examined in depth, there are very large differences even when answering a simple question such as who is considered a researcher in a given country (Jung et al., 2021).

Numerous studies over the world have examined the background factors affecting the wellbeing and especially the psychological health of the teachers, the sources of workplace stress that impair their wellbeing, or the predictors and protective factors that contribute to higher (psychological) wellbeing (Bentley et al., 2013). Low stress levels and good health are important predictors of high wellbeing (Johnson et al., 2005; Alqarni, 2021), but the relationships between these factors can also be examined in reverse: wellbeing (e.g., job satisfaction) may also predict health over time (e.g., sickness absences) (Hoogendoorn et al., 2002).

A portion of the sources of stress are related to workplace requirements (long working hours, time pressure, working conditions, inadequate facilities and students’ misbehavior, administrative burdens, providing academic and mentoring support, carrying out and fulfilling tasks required for quality assurance, pressure for grants and publications, managing a large number of e-mails, etc.) (Kinman et al., 2006; Salami, 2011; Alqarni, 2021), another portion to the factors limiting efficiency (ineffective management, the lack of administrative and technical support, poor communication, rushed work pace, frequent interruption of work, conflicting roles and limited opportunities to prepare for teaching, research, and professional development), and other problems (such as lack of respect, harassment, interpersonal conflicts, or job insecurity) (Iyaji et al., 2020). The high workload also significantly affects the health of the academics, which is related to and can be manifested in symptoms of depression, aggressiveness, impatience, rejection, and procrastination (Iyaji et al., 2020). Lack of management support refers to the situation when there is a lack of feedback, encouragement, and support when the work is emotionally taxing. It is also a very important source of stress if the colleagues do not support each other emotionally (Vigoda-Gadot and Talmud, 2010; Salami, 2011). The clarification of the roles is also a significant factor: this includes the clarification of individual roles and responsibilities in accordance with the goals of the institute and the whole institution. When an employee’s role within an institution is not clear, it can lead to high levels of ambiguity, insecurity, depression, rejection, and job dissatisfaction (Kinman, 2014; Iyaji et al., 2020). The final source of stress is change, that is, when there is no consultation with the colleagues about the changes that take place in the life of the institution, especially about how the changes that occur will be implemented in practice (Kinman, 2014).

In relation to teaching and research work, sources of stress can be identified as the growing number of students, the increased attention to quality education and research, international and domestic competition for resources and technological developments, as well as the ever rapidly changing technology, increasing workplace requirements on part of the higher education sector that provides high quality services and products. Research conducted among Australian and British academics and Saudi Arabian language teachers have overall identified extensive working hours, the large amount of work-related thoughts, inactivity and the difficulty of reconciling work and private life as the most important factors that affect psychological and physical wellbeing (Bell et al., 2012; Kinman, 2014; Alqarni, 2021; Fetherston et al., 2021).

Based on the above, the aim of our research is to examine the sources of stress (job demands) and resources that characterize the work of university teachers in five CEE countries and the effects of stress sources and resources on their health, wellbeing and effectiveness. Another question is how teachers cope with their workplace and how their institution can or could contribute to reducing stress. Due to the exploratory, qualitative nature of our survey, the teachers were deliberately not asked specifically about the job demands and resources that were tested in the JD-R theory previously, as presented in the literature review above. The interviews were conducted in general terms, asking academics what causes them stress and difficulties in their work and what kind of sources of pleasure can be found that make them enjoy their work. In the responses and experiences received, we sought to identify the factors described above and other unique factors by comparing the situation of CEE academics with colleagues who teach in different higher education institutions worldwide.

In our research, a qualitative method, focus group interviews was used, to reveal the job demands and resources, and the coping mechanisms affecting the wellbeing and health of Central and Eastern European university teachers. For the analyses, seven focus group interviews were conducted with academics from nine higher education institutions in five countries, online in 2022. In the first phase of the research, the members of the research team explored the literature related to their research topic in relation to academics, and then compiled and finalized the interview schedule. This was followed by the organization of focus groups in Hungary and the recruitment of moderators in the cross-border institutions. After the training of the moderators, the criteria for selecting the interviewees were defined and, based on these criteria, the selected subjects were invited. This was followed by technical organization of the interviews. Once recorded, the interviews were transcribed and the written material was manually coded and analyzed using JD-R theory.

When selecting the interviewees, it was aimed to obtain as heterogeneous a sample as possible in terms of faculties, disciplines, gender and age/position/professional experience. On this basis, interviewees were invited from each faculty by institution, taking into account the above criteria. It was sought to ensure that the interviewees did not include educational researchers who, as experts in the field and subject matter, would have provided biased responses. In each institution, it was assisted in the organization and preparation of the interview by a person who was a teacher at the institution, who was familiar with its structure and who had an appropriate network of contacts to be able to recruit enough interviewees to share their thoughts about their workplace.

Before selecting the interviewees, the moderators were briefed on the purpose of the research, the questions, the interview outline, and the sample selection criteria, and then the interviewers started to visit the interviewees. Once the subjects agreed, a convenient time was arranged for an interview of about 2 h. The interviews were conducted on a Zoom interface and recorded. Before the interviews began, the research ethics were explained, the subjects were assured of their anonymity, and verbal permission was sought from each of them individually to record and use audio material for analysis. All participants agreed to participate; thus, all interviewees’ responses could be recorded and used for analysis.

The length of the interview material is about 8 h, which was transcribed into a total of 168 pages of written text. The interview outline broadly examined the work and situation of the teachers along the following dimensions: introduction, dimensions of teaching effectiveness, challenges of higher education pedagogy, the impact of teaching work on wellbeing and health, institutional culture, leisure time and cultural consumption, experiences and attitudes toward disabled students, religiosity, language and ethnic diversity in higher education, the role of the institution in preserving and developing the health of the academics.

During the analysis, deductive and inductive coding was used: the difficulties and resources related to work in connection with the JD-R theory (deductive) were examined, and it was looked for other sources of stress and supporting factors inductively. Deductive coding was applied a priori using a code grid based on the literature, followed by data-driven generation of additional codes through further subdivision of text segments into subunits due to the semi-structured nature of the interview. Based on the answers, a type analysis was performed to typify the difficulties and resources, and a thematic analysis was performed regarding the coping strategies used to overcome stress, sports and other activities related to health behaviors, institutional contributions, and expectations. The codes are: (1) work-related difficulty, stress, and (2) resources; (3) individual protective factor, coping strategy; (4) institutional supporting factor and (5) expectations, that could promote the wellbeing of academics.

The number of participants in the focus group interviews was between four and eight from the following institutions (41 people in total): University of Debrecen (UD), Reformed Theological University of Debrecen (RTUD), University of Nyíregyháza (UNY) (Hungary); Sapientia Hungarian University of Transylvania (branch Miercurea Ciuc, SAPI, Romania), Partium Christian University (PCU, Romania); Ferenc Rákóczi II. Transcarpathian Hungarian Institute (THU, Ukraine), J. Selye University (JSU, Slovakia), University of Novi Sad (UNS), Subotica Tech–College of Applied Sciences (STCAS) (Serbia). The Hungarian universities are institutions from the North-Eastern region of the country, where the proportion of disadvantaged students is overrepresented compared to other regions, so the academics have to deal with special challenges. From the other countries, the higher education institutions of the Hungarian minority were picked, so the teachers and students are also in a special situation, due to being members of a minority. The interviewees were selected in such a way as to obtain heterogeneous groups according to gender, age, and position, as well as field of study (faculty). In terms of position, there were participants from all levels, from Ph.D. students who are part-time teachers to full professors, several interviewees also holding senior positions (department head, institute head, doctoral program president, dean, assistant dean, assistant rector). Based on the age known, the youngest respondent was 31 and the oldest was 65. 18 men and 23 women participated in the interviews (Supplementary Appendix 1).

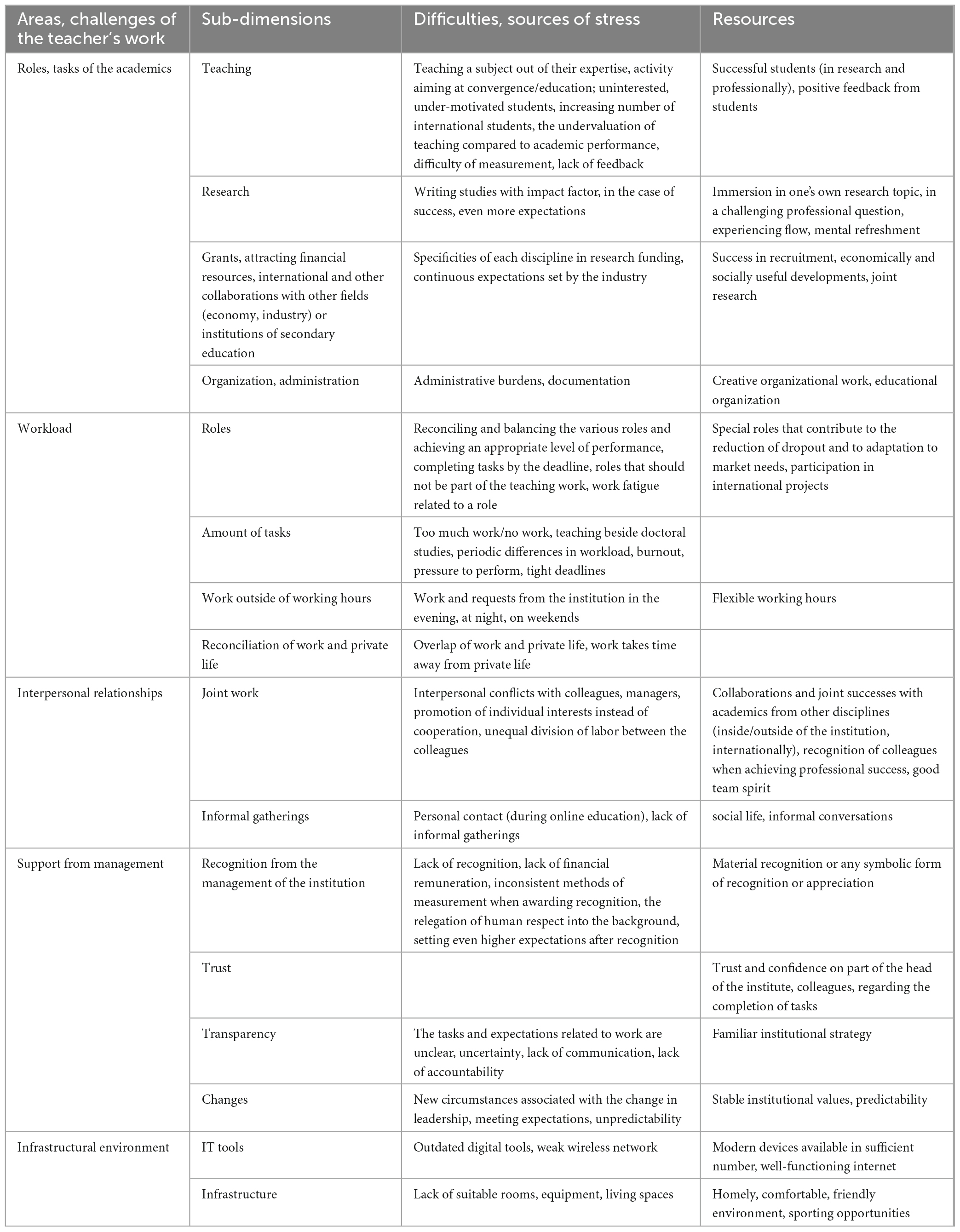

In the first part of the examination, the job demands and resources were discovered. These were compared to the previously identified factors by testing JD-R theory. Based on the analysis of the focus group interviews, five main issues, areas were able to be isolated that appear to be sources of stress or resources in the teaching work, and affect the wellbeing of the teaching staff. These are: 1. teaching tasks, roles, 2. workload, 3. interpersonal relationships, 4. the lack of management, and 5. the infrastructural environment. The reliability of the coding is confirmed by the fact that Kocsis and Hrabéczy (2023) identified the same codes in their analysis of the teachers’ work in the interviews conducted in Hungary. All the five areas contain sources of stress (job-demands) and resources (Table 1).

Table 1. Work-related stress and resources based on focus group interviews with academics. Source: own research.

The tasks of the academics include teaching, research, application for grants, attracting external financial resources, cooperating with actors in the economy in research and development projects, and organizational tasks. Difficulties that came up with regards to teaching include that it is undervalued compared to research performance, even though it takes a lot of work and energy to prepare, be up to date in the course material, to organize the classes, and pass on practical, but always professional knowledge. However, student feedback is not always adequate in this regard, especially during the time of COVID-19, when there was no personal contact. Hence instructors got feedback neither from the students nor from the institution in general about how well they were able to deliver the study material to the students. Hungarian institutions of higher education do have a mostly voluntary feedback system, as well as a completely informal website (markmyprofessor), where the work of a given instructor can be evaluated anonymously. However, these are not necessarily objective, as students are influenced by the difficulty and importance of the course material, and of course the grade received. This way, the measurement of the quality of education itself can also be problematic.

A further problem is that even if someone is an excellent lecturer and teaches interesting, diverse, and popular classes, this performance is still not equivalent with success in publication. Irrespective of the country, there is a very strong pressure on the academics to write studies with an impact factor, while the possibilities vary by the discipline to a large extent, very large differences can be witnessed (the technical and medical fields are at an advantage, while for example, the humanities, especially linguists doing research on the native language, are at a significant disadvantage). As the following interviewee put it,

“I think—and I’ve been in the field for thirty years—that in reality, at the university it has officially never really mattered how good of a teacher someone was. It obviously mattered in terms of work relationships and recognition, but otherwise, people are evaluated based on scientometrics… I never felt that it mattered whether one is a good teacher or bad teacher” (male, UD Faculty of Engineering).

In addition to these two roles, there is the continuous expectation to attract external resources. In this regard, the problems are differentiated when it comes to the particular fields: in humanities and social science, the problem is the scarcity of opportunities and obtainable resources, in the technical, technological, and IT fields, the challenge is meeting the expectations of the partners. Concerning the differences between the countries, it could be seen that in the institutions in Slovakia and Romania, administrative obligations are a heavy burden, while at certain Hungarian faculties, the increasing number of international students represents a challenge, primarily due to language issues and cultural differences. In the case of the Hungarian institutions outside of Hungary, the additional administrative burdens also arise from the necessity to comply with special requirements arising from the minority status.

The most difficult is the completion of tasks on a deadline, as well as compliance with the professional and institutional requirements. This is especially true if the teacher is at the beginning of their career, and in addition to their work, they also have to fulfill the conditions required to obtain their doctoral degree, while they have little experience with teaching students. It is also a difficulty that burdens are distributed unevenly throughout the semester, and often among colleagues, which is closely related to the next problem area, interpersonal relationships. Another problem is that certain tasks (usually teaching work) prove to be too much by themselves, so there is not enough time and energy for other areas (e.g., research that could form the basis of publications).

“Today’s university teacher has to be almost Superman. In addition to all kinds of impact factors and work for Chilean journals, you have to be a very good teacher, calm and attentive in class. In addition, you have to be able to lead projects, you must be a psychologist, finances are often entrusted to the project manager, everything that needs to be covered, costs, papers, documentation” (male, UND Faculty of Agriculture).

The variety of roles can be accompanied by significant workload, an increase in evening and weekend working hours, difficulties in reconciliation with private life, the reduction of time spent with the family, thus conflicts in personal life. Referring back to interpersonal relationships, the biggest psychological and mental difficulty is if the burdens are distributed unevenly, and they continuously fall on the colleague who is successful in any field of the work of the academic, thus being recognized by the institution. As stated by the next two interviewees,

“There is a saying in Hungarian, that the horse that draws better is the one that is beaten, and I think this kind of thing can be felt at every department. Meaning that if someone’s work capacity is over the average, then they get 80% of the tasks, and the remaining 20 percent gets distributed among the other colleagues” (female, SAPI, Teacher Training Institute).

Our interviewees referred to several factors of management support, emphasizing the importance of transparency, recognition, and control. A large-scale change took place in Hungarian higher education in 2021, when the vast majority of higher education institutions (with the exception of 6) became institutions held by private foundations.1 The significant salary increase was also realized at the University of Debrecen and the University of Nyíregyháza, in addition to which a performance evaluation system has also been developed until December 2022: here academics needed to list and quantify every activity related to teaching, research, and organizational tasks that they have completed in the past 4 years. If they reach the minimal requirement, they can keep their current salary, if not, then a so-called variable salary will be established as half of their salary, and they will receive the amount over the fixed salary (50%) in proportion to their performance. The functionality and efficiency of the evaluation system, as well as the acceptability of the wages calculated on this basis, will be revealed in February 2023. A similar system of evaluation was introduced earlier in other countries (Romania, Ukraine). Although it was stated that the new system of evaluation finally measures the work and performance of the academics unambiguously, it is not done ad hoc (e.g., recognition), but at the same time, some also pointed out that it affects collegial relationships negatively due to the competitive, performance-oriented approach, and human respect is pushed to the background.

“And then it also follows from this, the phenomenon, that the community of academics started to get individualized a little bit, and… well, maybe at first they started to see each other, the teachers, as adversaries, but after a while I feel that they see each other even as enemies, and informally it might seem like they are happy for each other’s successes, but under a little bit beneath the surface I feel that some kind of professional envy has begun” (male, University of Nyíregyháza, Institute of Music).

The final challenge related to work as a university teacher is the infrastructural environment. It makes work very difficult if there are no suitable classrooms, technical equipment for teaching, and especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of a private sphere for the teachers came to the forefront, where they can teach an online or even hybrid classes without being disturbed, with appropriate digital devices. The most important sources of stress are summarized in the following word cloud (Figure 1). In line with the above, the figure also draws attention to interpersonal conflicts, excessive and uneven workloads and the difficulties of the various teaching roles. In the latter case, problems include multiple roles and the need to perform evenly and at a high level in these roles, the underestimation of teaching in relation to research performance, and roles that should not be part of teaching. The difficulty of maintaining a good work-life balance is also a particular challenge.

In the five areas of the work of an academic presented above, in addition to the difficulties and challenges, it can also be managed to identify important resources. In case of the last, infrastructural conditions, it has a positive effect on the academics if the work environment is homely, intimate, friendly, where they can retreat to and serves their comfort (there is a kitchen, or a place where they can chat, have a coffee with the colleagues, etc.). The most important resource are teacher and student success, academic and professional achievements. A research, development result, a high-ranking article, international cooperation, and especially the positive feedback of students, and the development of a special mentoring, or experiencing the success together, can be reason for very important satisfaction, renewal, and joy. This is the case even if this cannot be measured, as can be read in the following quote:

“… that the student comes up and says thank you or writes an e-mail at the end of the semester. And I don’t know, but I think this can often compensate for a lot of things, especially in a period that almost leads to a burnout., I also think that the problem with this system is that we try to quantify something that really can’t be quantified.” (female, UD Faculty of Humanities)

If one manages to reconcile the various roles of the teacher and have enough time for research work, immerse in their own research, experience the flow while writing their own publication, and the related professional successes (publications, conference presentations) help get out of the everyday grind and provide the opportunity to recharge. In terms of the diversity of teaching roles, the most valuable resource is the ability to perform in all roles at an appropriate level and to have one or more roles, which the teacher can fulfill in. It was mentioned as an important advantage of teaching work that although the workload is large and diverse, the working hours are flexible, so the academics have freedom and can decide the activities beyond the classes that need to be taught. It is worth noting here that one of the interviewees evaluated as an important resource not just that the schedule is flexible, but that they also receive the support for this from the head of the institute in the form of trust: they do not have to sit in the office all day, as the head of the institute knows that they will do required tasks regardless. Another interviewee also mentioned trust. In her interpretation, she is entrusted by leaders with the responsibility of organizing joint, enjoyable programs for students and teachers. These have a very important community-building role and create a very intimate relationship with lecturers and students. Trust was identified as a new resource; it is not included in the JD-R theory.

In addition to achieving success, it is just as important that these elicit the appreciation and respect of the leadership of the institute and the colleagues, if they can be happy about these results together, and perhaps it is an even bigger resource if this is achieved jointly, or as part of an international cooperation, perhaps with colleagues from different institutes or with industrial players. Related to international relations, it is important to note how much face-to-face meetings mean after online teaching: people can meet, talk, see, feel each other, especially in Ukraine, where because of the war, the period of distance learning was extended, and constant tension, insecurity, fear became part of everyday life (Table 1). This clearly shows the prominent role of interpersonal relationships (with colleagues, students), the joy of teaching and working with students, students’ and own success, and the positive feedback from leaders, colleagues, and students as the Figure 2 shows.

JD-R theory is an enhanced version of the JD-R model, and the key difference between the two is that the theory also examines the coping strategies, which can help individuals to cope with stress caused by the job demands. In our research, it was also examined the individual methods that interviewees use to cope with difficulties and stress in the workplace, and to attempt to maintain their health and wellbeing. The most frequently mentioned form of health behavior was playing sports and regular physical activity (13 people), and three people mentioned spending their leisure time with active recreation (excursions, hiking). Significant differences can be observed between the institutions (countries) examined; among the subjects in Ukraine, no one mentioned physical activity or sports, while when it comes of gender, there was an equal proportion of active teachers. Taking vitamins, regularly participating in screenings, avoiding harmful addictions, and an enough rest (sleep) were noted in connection with behavior that protects health. Passive free-time activities, such as reading, watching movies, listening to music were also mentioned, as well as social and communal activities (self-improvement groups, choir, church community).

The next important protective factor is the family (mentioned by 5 people): the quality time spent with them gives strength, opportunity for renewal, exit from the daily grind, the wellbeing of the family can be a source of wellbeing for the individual as well, therefore it is a source of great difficulty and exhausting for academics if they fail to preserve the balance of work and private life. This was especially apparent during the time of COVID, when the time spent with the family and work completely collided physically as well. Two female interviewees mentioned that taking care of the family, i.e., housework, provides refreshment after periods of work:

“I am truly at peace with myself when I have patience for the recipe book. Because I usually cook the daily, usual routine from my head, and based on what’s in the fridge. But when I see that Jamie Oliver winking from the shelf, it’s really like I don’t have a deadline. And then this is also a kind of self-realization, that I had time to think a little beyond the daily routine, in a context different from the university” (female, SAPI Miercurea Ciuc Faculty, Teacher Training Institute).

The last type of stress-relieving techniques is spirituality, turning inward, experiencing the inner silence, defining and observing the boundary between work and life outside of work, in order to preserve mental and spiritual balance.

Going beyond the JD-R theory and previous research on this topic, one of the novelties of our study was not only to explore individual coping strategies, but also to investigate what factors at the institutional level help teachers to reduce workplace stress, and thus how higher education institutions contribute or can contribute to teachers’ health, wellbeing and work outcomes. Thus, as the final step of our research, it was examined how the institutions can contribute to the wellbeing of the academics, and the reduction of sources of stress in the workplace. In this regard, it can be differentiated between two areas: the contribution of the institutions, and the expectations of the academics. When it comes to institutional contributions, the respondents mentioned the adequate infrastructure on the one hand, and on the other hand, sports opportunities, the use of sports infrastructure, as well as communal sports programs, the purpose of which is to build community not only with the colleagues, but also with students, in addition to promoting a health-conscious lifestyle. The importance of interpersonal relationships as a resource was already noted, these programs help colleagues within an institution to form a good team that can motivate each other, cooperate effectively, as the following interview excerpt also points out:

“I used to look down on everyone, who is running. Or is doing any sports… Then I got into an environment, at the Faculty of Public Health, where everyone pays more attention to their health. And I started doing sports, I started running. When the big university tells me to do it, I am not sure that I would pay attention. But when my colleague, with whom I am otherwise in daily contact, starts whispering in my ear, … but three months later I start asking them what kind of running shoes I should buy. Such small communities have an amazing, formative power, and can probably also form a very good protective shell for our mental health.” (male, UD Faculty of Public Health)

These sporting opportunities were mainly mentioned by the interviewees from Hungary, Slovakia, and Ukraine. Mental health and psychological counseling at the University of Debrecen and the college in Transcarpathia make an important contribution to the preservation of mental and psychological wellbeing.

The expectations are primarily related to support by the management. The lack of support from administrative staff was not mentioned. But as it was noted above, primarily in the Romanian and Serbian institutions, the interviewees highlighted the need for transparent, unambiguous requirements and expectations from the management, as well as continuous feedback and control, so that there would consequences, if someone does not fulfill their obligations. Decisive leadership is also important, defining the institutional values and the development of a strategy, where the academics should also be involved. The teachers at Serbian institutions would require an increase in salary, the Slovakian teachers would require the reduction of administrative burdens, and they miss community-building programs in the institutions where there are none, or where they were stopped.

In our study, sources of work-related stress and resources affecting the health and wellbeing of Central and Eastern European university academics were examined based on the JD-R theory. Similarly to research conducted among university teachers in Britain, Australia (Kinman et al., 2006; Bell et al., 2012; Fetherston et al., 2021), Pakistan (Aziz and Quraishi, 2017), Saudi Arabia (Alqarni, 2021), China (Han et al., 2020) and Nigeria (Iyaji et al., 2020), the most important workplace difficulties, challenges, and resources are related to teaching roles, interpersonal relationships, support by the management, and infrastructural conditions. In accordance with the results of research conducted by Kinman (2014) and Fetherston et al. (2021) among British and Australian researchers, the reconciliation of the different roles (teacher, researcher, administrator, mentor etc.) is the greatest source of stress. An important finding of our research is that, although the interviewees were not asked specifically about the prevalence, importance and role of these stressors and resources in their work, they were only asked in general terms to describe what causes them stress, difficulty and pleasure in their work. Yet the responses identified the same factors that were previously examined during the testing of JD-R theory. The different teaching roles in each country were mentioned as difficulties to reconcile them or even the undervaluation of the teaching role in relation to the researcher’s performance. Thus, we did not find differences between countries but rather between disciplines. In STEM fields, particularly in cases where there is a need to collaborate with industrial companies, there are more roles to play. In contrast in some humanities fields (e.g., linguistics), the expected high publication pressure is a major burden, as it is difficult to get into IF journals due to the peculiarities of the Hungarian language. As a result, securing external funding, which typically comes from grants, is considerably more restrictive. The importance of support from management, a clear and unambiguous institutional strategy and goals, and transparent expectations were highlighted mainly by Serbian and Romanian academics. The lack of infrastructural conditions was also mentioned as a source of stress, mainly by teachers from Romanian and Hungarian institutions, while the administrative burdens by the Slovakian interviewees.

One of the most important differences between previous research and our study is the appearance of the issue of trust, which was not encountered in research introduced previously utilizing the JD-R model or theory. It was mentioned by two interviewees from a Hungarian and a Slovakian HEIs. An important finding is that mistrust as a source of stress was not formulated, but trust as a resource is an important support factor in the work of teachers. Trust is an important element of Putnam’s concept of social capital (Putnam, 2015). It is the basis for the effective functioning of communities, and if well-functioning interpersonal relationships characterize the work of teachers, they are considered primary capital and resources that can contribute to job satisfaction (Agneessens and Wittek, 2008). In our research, our interviewees considered both forms of trust (institutional and interpersonal) to play a prominent role. Interpersonal relationships were found to be part of everyday life in the form of joint research, the management of proposals, the achievement of successes, informal conversations and coffee breaks, and when these are characterized by mistrust, they are a very serious source of stress in the work of the teachers, which they find difficult to cope with. According to the interviewees, there are two areas that could break trust. The first one stems from interpersonal conflicts like disagreements arising from unequal division of labor, communication gaps, etc. The other potential source is the performance-based pay resulting from competition for university ranking in several countries (Romania, Ukraine, Hungary), which negatively affects these two areas of social capital, institutional and interpersonal trust, by generating competition between academics, increasing mistrust, suspicion, envy, and individualizing work, performance and success. It also creates difficulties in terms of interpersonal relationships if the micro-communities at work that are important to the individual are loosened or possibly broken up, e.g., among others, due to the distancing caused by the COVID epidemic, and now the war in Ukraine. All this can have a negative impact on workers’ wellbeing as it was emphasizing some interviewees from Ukraine. Previous research has shown that institutional and interpersonal trust are important predictors of subjective wellbeing (Jovanović, 2016), with the latter being negatively related to job stress, burn out and positively contributing to job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Vigoda-Gadot and Talmud, 2010; Guinot et al., 2014).

The issue of institutional trust is closely linked to management support as a resource. A positive aspect of the work of the teachers was the mutual trust between the management and the teacher, the fact that they do not necessarily have to be present in the institution from morning to night, that they are not under constant supervision, and yet they believe in each other that everyone is doing their job honestly. Therefore, the teaching job has a high degree of flexibility, which is a great advantage compared to other jobs. However, the lack of management support greatly reduces trust in the institution and is a major source of stress. Based on their results, Kinman (2014) and Alqarni (2021) highlighted the importance of clear, transparent, clearly defined tasks, expectations, institutional strategy, as well as encouragement and recognition from the institutions, furthermore, the involvement of academics in changes in the life of the institution. All of these factors fall within the scope of management support, and mentioned by our interviewees.

The most important resources are also strongly linked to interpersonal relationships and trust concerning the difficulties mentioned above and coping with them. Such resources include working together and achieving success with gifted or even with less talented students (teacher-student relationship), working together and achieving success in applications and academic research, informal and friendly conversations, relationships and leisure activities with colleagues (teacher-teacher relationship), and trust from immediate superiors and colleagues (supervisor-subordinate relationship). Furthermore, previous research has shown since the beginning of the last century that these well-functioning, mutually trusting workplace micro-communities contribute more to job satisfaction and employee wellbeing than technical conditions (Agneessens and Wittek, 2008). The role of interpersonal relationships as resource was mentioned by Hungarian, Romanian and Ukrainian academics. Also, when examining the role of the institution beyond the formal, top-down, institution-run organizations and programs (mental health services, sports, recreational activities, etc.), the interviewees’ primary expectation and effective help in coping with workplace stress was the assistance of these informal micro-communities. Mental health services, sports, and recreational activities are mainly available in institutions in Hungary, Slovakia and Ukraine and represent an important institutional contribution to the mental health of teachers.

Related to the JD-R Theory, the tools were examined that teachers use at the individual level to cope with workplace stress and challenges. They deal with the workplace stress by playing sports, physical activity and quality, active time spent with the family in order to preserve their health and wellbeing. At the same time, in accordance with earlier studies (Kinman, 2014; Koen et al., 2018; Iyaji et al., 2020), the vast majority of subjects do not play sports or perform regular physical activity (only 13 people do), however, regular physical activity and active recreational activities have a primary role in health prevention and an important contribution to wellbeing and quality of life (Lengyel et al., 2019; Devita and Müller, 2020; Kinczel and Müller, 2023). There are also significant differences between countries in terms of sport and physical activity. While more respondents in Hungary and Slovakia mentioned sports, and more respondents in Romania and Slovakia mentioned recreational physical activities such as walking, hiking, and climbing as stress-relieving activities due to the environmental conditions, there were no respondents in Ukraine who mentioned physical activities. Several studies draw attention to the unhealthy lifestyle of university teachers, employees (inactivity, unhealthy diet, high stress, etc.) which also leads to loss of life among them in many cases (Iyaji et al., 2020). Still, only a few studies deal with the physical activity of the academics, the problem of inactivity, while compared to the average population, they are more likely to be familiar with physical activity’s importance and its beneficial effects on various dimensions of health, especially those who work and do research on this field. But this knowledge is not always followed by the activity (Kwiecień-Jaguś et al., 2021).

The results of our study suggest practical implications at institutional and micro-community levels that can contribute to reducing workplace stress and thereby increase the physical, mental and psychological health, wellbeing, job satisfaction, work engagement and efficacy of academics. At the institutional level, the most important requirement is the formulation of a clear, unambiguous institutional strategy, goals and expectations for teachers, and a transparent performance evaluation system. It would also be important to provide free or at least discounted sports and recreation programmes, facilities and counseling services from the side of the institution to help teachers cope effectively with everyday stress. At the micro level, it is very important to support and encourage small community initiatives (at the level of institutes, departments) that are team- or community-building, strengthening interpersonal relationships, cooperation and trust.

Our research has limitations due to its exploratory nature. Since the interviews were conducted primarily in the minority Hungarian institutions of higher education in non-Hungarian countries, we could not learn about the opinions and experiences of the majority Hungarian teachers. Being qualitative research, the reliability of the results is limited. Due to the small number of items and scope limitations, it was not possible to make comparisons by gender, age/grade and discipline. We intend to carry out these comparative analyses in our next questionnaire survey.

In our study, a qualitative method was used to investigate the job demands and resources of CEE academics in relation to the JD-R theory. Due to the exploratory nature of the research, the stress and resources mentioned by the academics were compared with the factors previously identified in the testing of the JD-R theory. It can be concluded that, for the most part, teachers in the region mentioned the same stressors and resources as those found in the previous literature. However, at the same time, the issue of trust was identified as a new resource, which represents access to previously known job resources. Contributing to previous researches on this topic, it was examined and identified how HEIs at institutional level can contribute to reducing workplace stress for lecturers.

The most important message of our study is that the institutional environment is key to both the effective work and wellbeing of the academics. This requires well-functioning technology and suitable infrastructure (PCE), financial remuneration independent of external grants for existential security. Meanwhile, it is even more important to define predictable, transparent institutional goals, strategy, and jointly agreed values, to create a predictable and controlled system of evaluation and rewards, which do not change according to the whims of the current leadership or with the change of leadership (in Serbia and Romania). For this reason, constant and effective communication between the leadership and the smaller subunits is very important: the challenges that need to be dealt with every day and must be known, unambiguous, and clear for both parties, and expectations must be set toward each other. Although a stable, predictable system of evaluation already exists in several countries (Romania, Ukraine), and compliance with it is another source of stress, but it has only been introduced into the operation of the institutions examined in Hungary during the recent changes in higher education. Thus, its effectiveness is not yet known, but at the same time it promotes predictability and transparency, which go hand in hand with the differentiation of wages. This could result in a kind of competitive situation within the teaching community, which can negatively affect interpersonal relationships.

Among the resources related to work, a good community or team within the faculty or with colleagues from other institutes stands out, so it is extremely important for the management of the institution to support these common, grassroots teambuilding programs. In addition, institutions can contribute to the wellbeing and health of the academics primarily by offering free or at least discounted participation in sports, cultural and leisure events, as well as mental health counseling, but it is important for these not to be self-serving (the colleagues from the university should not participate in the programs to make up for the missing audiences of the otherwise overfunded organizations of the institution) and haphazard: without a targeted health strategy, these are not sufficiently effective.

Due to reasons of brevity, it has not the opportunity to examine in detail the demographic and country differences in teaching work and the institutional background. This will examine the job demands and resources in the CEE countries concerned, with a focus on differences between the countries and exploring the connections with the wellbeing and performance of academics. Additional research directions will involve examining the background of stress and resources, as well as individual and institutional factors that may compensate for the stress caused by job demands. the next step of our research, it is planned to make a comparison by conducting a questionnaire study on a wide sample, supplemented by the lessons learned from the focus group interviews.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data set contains sensitive personal data, so it cannot be passed on to persons who did not participate in the research. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to KK a292YWNzLmtsYXJhQGFydHMudW5pZGViLmh1.

The studies involving humans were approved by the School Ethics Committee of Doctoral Program on Educational Sciences at the University of Debrecen. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because before the interviews began, the research ethics were explained, the subjects were assured of their anonymity, and verbal permission was sought from each of them individually to record and use audio material for analysis. All participants agreed to participate; thus, all interviewees’ responses could be recorded and used for analysis. Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article because before the interviews began, the research ethics were explained, the subjects were assured of their anonymity, and verbal permission was sought from each of them individually to record and use audio material for analysis and publications. All participants agreed to participate.

KK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. TP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. IT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

The authors declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This publication was supported by the project “Investigating the role of sport and physical activity for a healthy and safe society in the individual and social sustainability of work ability and quality of work and life (multidisciplinary research umbrella program) and by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences”.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1326515/full#supplementary-material

Aarrevaara, T., Finkelstein, M., Jones, G. A., and Jung, J. (2021). “The academic profession in the knowledge-based society (APIKS): Evolution of a major comparative research project,” in Universities in the knowledge society: The nexus of national systems of innovation and higher education, eds T. Aarrevaara, M. Finkelstein, G. A. Jones, and J. Jung (Berlin: Springer International Publishing), 49–64. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-76579-8_4

Agneessens, F., and Wittek, R. (2008). Social capital and employee well-being: Disentangling intrapersonal and interpersonal selection and influence mechanisms. Rev. Fr. Sociol. 49, 613–637. doi: 10.3917/rfs.493.0613

Alqarni, N. A. (2021). Well-being and the perception of stress among EFL university teachers in Saudi Arabia. J. Lang. Educ. 7, 8–22. doi: 10.17323/jle.2021.11494

Aziz, F., and Quraishi, U. (2017). Empowerment and mental health of university teachers: A case from Pakistan. Pakistan J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 15, 23–28.

Bakker, A. B. and Demerouti, E. (2014). “Job Demands-Resources Theory.” In Work and Wellbeing: Wellbeing: A Complete Reference Guide, eds P. Y. Chen and C. L. Cooper. (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd).

Bell, A. S., Rajendran, D., and Theiler, S. (2012). Job stress, wellbeing, work-life balance and work-life conflict among Australian academics. E-J. Appl. Psychol. 8, 25–37. doi: 10.7790/ejap.v8i1.320

Bentley, P. J., Coates, H., Dobson, I. R., Goedegebuure, L., and Meek, V. L. (2013). “Academic job satisfaction from an international comparative perspective: Factors associated with satisfaction across 12 countries,” in Job satisfaction around the academic world, eds P. J. Bentley, H. Coates I, R. Dobson, L. Goedegebuure, and V. L. Meek (Berlin: Springer), 239–262. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5434-8_13

ChaaCha, T. D., and Oosthuysen, E. (2023). The functioning of academic employees in a dynamic South African higher education environment. Front. Educ. 8:1016845. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1016845

Devita, S., and Müller, A. (2020). Association of physical activity (sport) and quality of life: A literature review. GeoSport Soc. 12, 44–52. doi: 10.30892/gss.1205-057

Fetherston, C., Fetherston, A., Batt, S., Sully, M., and Wei, R. (2021). Wellbeing and work-life merge in Australian and UK academics. Stud. Higher Educ. 46, 2774–2788. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1828326

Guinot, J., Chiva, R., and Roca-Puig, V. (2014). Interpersonal trust, stress and satisfaction at work: An empirical study. Pers. Rev. 43, 96–115. doi: 10.1108/PR-02-2012-0043

Han, J., Yin, H., Wang, J., and Zhang, J. (2020). Job demands and resources as antecedents of university teachers’ exhaustion, engagement and job satisfaction. Educ. Psychol. 40, 318–335. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2019.1674249

Höhle, E. A., and Ulrich, T. (2013). “The Academic Profession in the Light of Comparative Surveys.” In The Academic Profession in Europe: New Tasks and New Challenges, eds B. Kehm and U. Teichler. (Dordrecht: Springer).

Hoogendoorn, W. E., Bongers, P. M., de Vet, H. C., Ariëns, G. A., van Mechelen, W., and Bouter, L. M. (2002). High physical work load and low job satisfaction increase the risk of sickness absence due to low back pain: Results of a prospective cohort study. Occup. Environ. Med. 59, 323–328. doi: 10.1136/oem.59.5.323

Iyaji, T., Eyam, S. O., and Agashi, V. A. (2020). An assessment of some stress factors in academic profession and their health implications among academics in tertiary institutions in cross river state Nigeria. Int. J. Innov. Res. Adv. Stud. 7, 53–59.

Johnson, S., Cooper, C., Cartwright, S., Donald, I., Taylor, P., and Millet, C. (2005). The experience of work-related stress across occupations. J. Manag. Psychol. 20, 178–187. doi: 10.1108/02683940510579803

Jovanović, V. (2016). Trust and subjective well-being: The case of Serbia. Pers. Individ. Differ. 98, 284–288. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.061

Jung, J., Jones, G. A., Finkelstein, M., and Aarrevaara, T. (2021). “Comparing Systems of Research and Innovation: Shifting Contexts for Higher Education and the Academic Profession.” In Universities in the Knowledge Society: The Nexus of National Systems of Innovation and Higher Education, eds T. Aarrevaara, M. Finkelstein, G. A. Jones, and J. Jung 415–28. (Cham: Springer International Publishing). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-76579-8_23

Kinczel, A., and Müller, A. (2023). The emergence of leisure travel as primary preventive tools in employee health behaviour. GeoJournal Tourism Geosites 47, 432–439. doi: 10.30892/gtg.47209-1041

Kinman, G. (2014). Doing more with less? Work and wellbeing in academics. Somatechnics 4, 219–235. doi: 10.3366/soma.2014.0129

Kinman, G., Jones, F., and Kinman, R. (2006). The well-being of the UK academy, 1998–2004. Q. Higher Educ. 12, 15–27. doi: 10.1080/13538320600685081

Kocsis, Z., and Hrabéczy, A. (2023). Felsooktatási kihívások és az oktatói jóllét összefüggései egy kvalitatív kutatás tükrében. Neveléstudomány 11, 46–64. doi: 10.21549/NTNY.42.2023.3.3

Koen, N., Philips, L., Potgieter, S., Smit, Y., van Niekerk, E., Nel, D. G., et al. (2018). Staff and student health and wellness at the faculty of medicine and health sciences, Stellenbosch University: Current status and needs assessment. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 60, 84–90. doi: 10.1080/20786190.2017.1396788

Kwiecień-Jaguś, K., Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W., Kopeć, M., Piotrkowska, R., Czyż-Szypenbejl, K., Hansdorfer-Korzon, R., et al. (2021). Level and factors associated with physical activity among university teacher: An exploratory analysis. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 13:114. doi: 10.1186/s13102-021-00346-5

Lei, J. (2022). Research article professional well-being and work engagement of university teachers based on expert fuzzy data and SOR theory. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022:4191405. doi: 10.1155/2022/4191405

Lengyel, A., Kovács, S., Müller, A., Lóránt, D., Szőke, S., and Bácsné Bába, É (2019). Sustainability and subjective well-being: How students weigh dimensions. Sustainability 11:6627. doi: 10.3390/su11236627

Moueleu Ngalagou, P. T., Assomo-Ndemba, P. B., Owona Manga, L. J., Owoundi Ebolo, H., Ayina Ayina, C. N., Lobe Tanga, M. Y., et al. (2019). Burnout syndrome and associated factors among university teaching staff in Cameroon: Effect of the practice of sport and physical activities and leisures. Encéphale 45, 101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2018.07.003

Papp, D., Győri, K., Kovács, K. E., and Csukonyi, C. (2021). The effects of video gaming on academic effectiveness of higher education students during emergency remote teaching. Hungar. Educ. Res. J. 12, 202–212. doi: 10.1556/063.2021.00101

Pimenta, R., Liege, C., Rónay, Z., and Németh, A. (2021). Centralisation and decentralisation in higher education: A comparative study of Hungary and Germany. Pedagogy 93, 1119–1135.

Pusztai, G., and Márkus, Z. (2019). Paradox of assimilation among indigenous higher education students in four Central European countries. Diaspora Indig. Minor. Educ. 13, 201–216. doi: 10.1080/15595692.2019.1623193

Putnam, R. D. (2015). “Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital,” in The city reader, 6th Edn, eds R. T. LeGates and F. Stout (London: Routledge). doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113501

Salami, S. O. (2011). Job stress and burnout among lecturers: Personality and social support as moderators. Asian Soc. Sci. 7:110. doi: 10.5539/ass.v7n5p110

Szigeti, F., and Kovács, E. (2022). ‘The role of objective and subjective health-awareness factors in students’ higher educational pathways.’. Youth Central Eastern Eur. 8, 61–75. doi: 10.24917/ycee.2021.12.61-75

Keywords: academics, job demands-resources (JD-R) theory, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), higher education institutions (HEI), focus group interview

Citation: Kovács K, Dobay B, Halasi S, Pinczés T and Tódor I (2024) Demands, resources and institutional factors in the work of academic staff in Central and Eastern Europe: results of a qualitative research among university teachers in five countries. Front. Educ. 8:1326515. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1326515

Received: 23 October 2023; Accepted: 11 December 2023;

Published: 05 January 2024.

Edited by:

Juliana Elisa Raffaghelli, University of Padua, ItalyReviewed by:

Dan-Cristian Dabija, Babeş-Bolyai University, RomaniaCopyright © 2024 Kovács, Dobay, Halasi, Pinczés and Tódor. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Klára Kovács, a292YWNzLmtsYXJhQGFydHMudW5pZGViLmh1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.