- Faculty of Science, VU Amsterdam, Athena Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Despite the growing trend to integrate engaged education activities in (Higher) Education Institutions ((H)EIs), their adoption responds to diverse and often conflicting rationales. These rationales are shaped by institutional logics at both the field and organizational level, and their conflicting nature is a manifestation of the institutional complexity that arises when organizations and the individuals within them are confronted with divergent prescriptions from multiple institutional logics. This study examines how engaged practitioners in (H)EIs experience institutional complexity and how they respond to such complexities. We conducted research at the intersection of field-level and organizational-level logics, and individual responses. Our findings show that engaged practitioners who initiate engaged education that follows the principles of the dominant market and corporate logics do not experience institutional complexity, and we therefore refer to them as compliers. Conversely, those whose intentionality follow the minority state logic take different roles in their response to the underlying institutional complexity. Those roles may refer to the adherence to multiple conflicting logics while keeping them apart (compartmentalizers), the (selective) combination of elements of dominant and minority logics (combiners), or the (partial) rejection of the dominant logic to protect the minority logic (protectors). The implications of our study offer valuable insights into the change process in (H)EIs concerning the integration of engaged educational processes and activities.

Introduction

There is a growing trend in (Higher) Education Institutions ((H)EIs) to integrate various forms of engaged education activities. Inquiry-based learning, community service learning, engaged education, and transformative learning (McGregor, 2017) are examples of these kinds of practices. In this study, we define engaged education as educational activities in which students, as part of their curricular activities, apply their knowledge and practices to contribute to social issues in collaboration with an external community partner (Bringle and Hatcher, 1995; Tijsma et al., 2020). Individual practitioners within these (H)EIs are increasingly seeking to embed these engaged education activities within their curricula (Lund Dean and Wright, 2017). In addition to this bottom-up approach driven by engaged practitioners, (H)EIs are promoting engaged education through top-down measures (Agasisti et al., 2019; Compagnucci and Spigarelli, 2020). For instance, core missions are redesigned and expanded, by giving more emphasis to the need to contribute to the social, economic, and cultural developments of the regions in which they operate (Agasisti et al., 2019). Both the top-down and bottom-up approaches contribute to more structural embedding of engaged education practices in which students contribute to addressing social issues as part of their curricular activities (Clark, 2017).

There are different—and sometimes conflicting—rationales for adopting engaged education practices. In her work on the conceptual development of the scholarship of engagement, Sandmann (2008) notes that (H)EIs express engagement in various ways due to the complex institutional dynamics and highly disaggregated nature of these institutes. Previous studies have shown that engaged education can be framed as a means to address social challenges or increase students’ social, civic, and moral development. Mitchell (2008) and later also Shea et al. (2021) have argued for instance, that some forms of engaged learning can encourage students to see themselves as agents of social change, and use the experience of ‘service’ to address and respond to injustice in communities. On the other hand, engaged education can also be framed as a means to prepare work-ready graduates, as well as increase revenues and teaching efficiency (Lounsbury and Pollack, 2001; Taylor and Kahlke, 2017; Compagnucci and Spigarelli, 2020; LaCroix, 2022). The potentially conflicting nature of these rationales become more evident when there is a misalignment between individual action (i.e., the individuals’ intention and rationale to adopt engaged education in their work), and the rationales behind the organizational policies and practices associated to the expansion of the organizational core mission and visions toward engaged education (Pekkola et al., 2022).

Those rationales are shaped by institutional logics, namely an overarching set of principles that prescribe what constitutes appropriate behavior and how to succeed in a given organization (Thornton et al., 2012). Thus, these tensions between organizational practices and individual action are a manifestation of the institutional complexity that arises when organizations and the individuals within them are confronted with divergent prescriptions from multiple institutional logics (Thornton et al., 2012). The ever-expanding body of literature on institutional logics has to date focused mainly on organizational development, rather than on the experiences of individuals navigating this institutional complexity (Gautier et al., 2018; Pache and Thornton, 2020). In particular in the context of higher education, little is known about how logics at the organizational level play out at the individual level (Cai and Mountford, 2022; Siekkinen and Ylijoki, 2022).

This research takes the Dutch context as its point of departure and aims to answer the following research question: How do practitioners within different (H)EIs in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, experience and respond to institutional complexity within their engaged education practices? Answering this question contributes to a better understanding of how engaged practitioners in (H)EIs respond when navigating institutional complexity. These insights may help inform the design and implementation of engaged education, as well as the institutional embedding needed for individuals pursuing in these practices.

Institutional logics, institutional complexity, and individual responses

Institutional logics make it possible to consider interactions across social, field, organizational, and individual levels (Thornton et al., 2012). At the level of society, scholars have identified seven distinct institutional orders and their associated logics [i.e., family, community, religion, state, market, profession, and corporation; Thornton et al., 2012; also discussed by Friedland (1991) and Thornton (2004)]. These logics encompass broader cultural, social, and economic systems that influence ways of thinking, organizing, and behaving in society overall (Besharov and Smith, 2014). Whereas field-level institutional logics refer to the prevailing sets of beliefs, values, norms, and practices that shape organizations’ behavior and decision-making within a specific field or industry. These logics provide a shared understanding of what is considered appropriate and legitimate in the field, guiding the actions and interactions of organizations, professionals, and other stakeholders (Besharov and Smith, 2014).

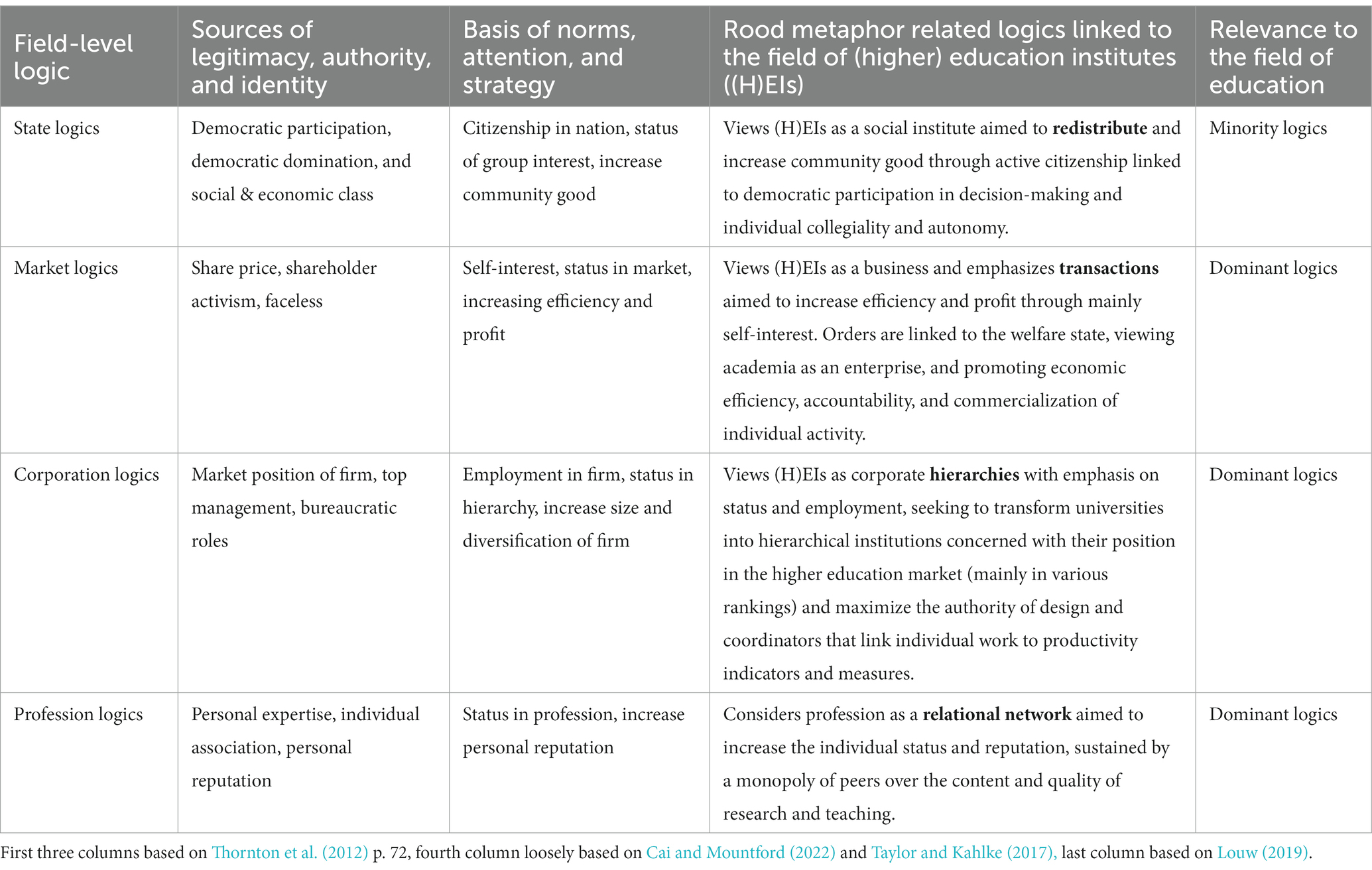

To gain insights into the different institutional logics to which individuals are exposed in (H)EIs, we draw on the work of Cai and Mountford (2022), whose systematic literature review finds that field-specific logics of higher education can be clustered in four main groups: professional logics, market logics, corporate logics, and state logics. The academic, or professional, logics consider the profession as a relational network and emphasize status in a profession through high-quality teaching and research; market logics view (H)EIs as a transitional entity aiming to increase profit; corporation logics consider (H)EIs as hierarchical entities with an emphasis on status; and state logics emphasize the important role of (H)EIs in contributing to the common good (Cai and Mountford, 2022).

The logics that drive individual behavior are to a large extent determined by the availability and accessibility of logics as these direct the individuals’ attention (Thornton et al., 2012). This makes it important to consider that these field-level logics will probably not be equally central to the organization and, and consequently to the individuals working within it. Based on Durand and Jourdan (2012), we refer to the logics that play a bigger role in informing an organization’s objectives, vision, and practices as the ‘dominant logics’ and any additional logics as ‘minority logics.’ In the educational field, market, corporate, and professional logics are generally reported as the dominant logics (Louw, 2019), with the state logics being considered a minority logic. Table 1 provides an overview of the educational field-level logics used in this study.

To understand how engaged practitioners experience institutional complexity, and the nature of this complexity, individual motivations and behavior can be associated with the above-mentioned logics (Greenwood et al., 2011). For instance, engaged practitioners’ might experience institutional complexity because their own intentionality is shaped by the state logics of common good, aiming for redistribution (Vargiu, 2014; Shea et al., 2023). These practitioners could experience increased institutional complexity due to the dominant field-level market logic of increasing efficiency (Louw, 2019; Shea et al., 2023). The presence of different institutional logics elicits contrasting responses from individuals, including ignoring, rejecting, and adopting them (Pache and Santos, 2013; Gautier et al., 2023).

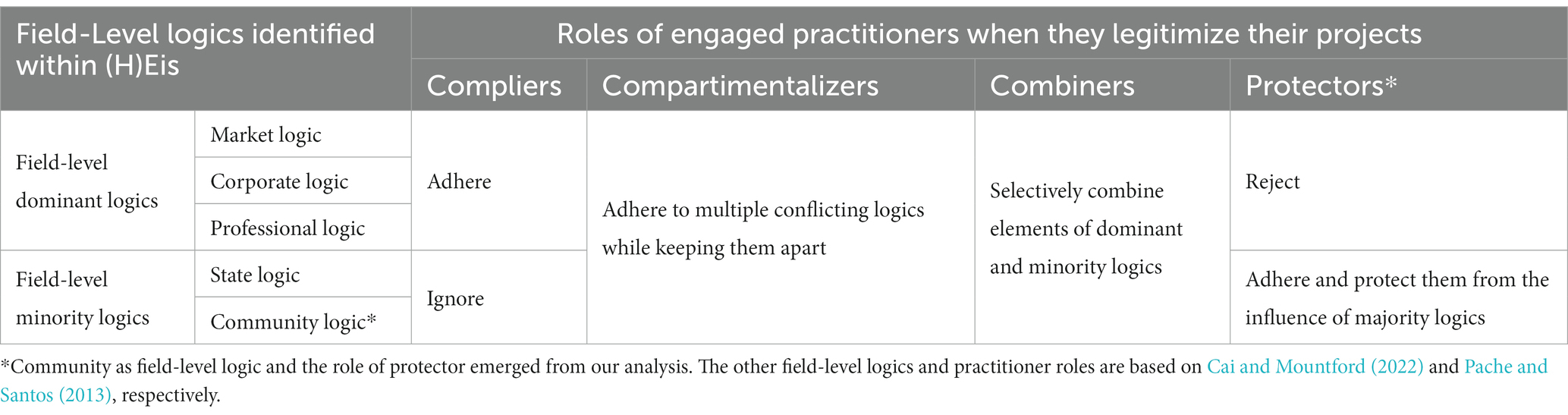

To gain insights into possible responses of engaged practitioners, we build on the work of Pache and Santos (2013), who describe five patterns of individual responses in the face of competing institutional logics, namely: Ignorance, Compliance, Defiance, Compartmentalization or Combination. Ignorance refers to the lack of response because the individual is unaware of the logics’ influence. Compliance refers to ‘an individual’s full adoption of the values, norms, and practices prescribed by a given logic’ (p.12). Defiance on the other hand, refers to an individuals’ explicit rejection of a given (dominant) logic. Compartmentalization refers to the purposeful segmentation of two competing logics by an individual. Finally, combination refers to the individuals’ attempt to blend values, norms and practices associated with the competing logics.

Pache and Santos (2013) also note that when individuals are exposed to a single logic, they might resort to ignorance, compliance, or defiance. When individuals are exposed to institutional complexity as a result of tensions between competing logics, they might resort to more complex responses such as compartmentalization or combination. Pache and Santos (2013) also outline the importance of exposure and adherence to a particular logic in shaping certain responses. For instance, when individuals are less familiar with a particular logic and identify with another logic, they will comply with the logic they identify with. However, when an individual identifies with 2 competing logics, they will most likely try to combine these logics.

Engaged education in Amsterdam, the Netherlands

In order gain insights into how engaged practitioners experience institutional complexity and how they respond to this complexity, we included three (H)EIs within the region of Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

In the Netherlands there are three main educational routes after secondary education:

• Middelbaar Beroeps Onderwijs (MBO) Secondary Vocational Education

• Hoger Beroepsonderwijs (HBO) Higher Vocational Education

• Wetenschappelijk Onderwijs (WO) University

From now on, we refer to MBO, HBO, and WO institutes. The Dutch context is a good basis for understanding how institutional logics at the organizational level play out at the individual level for multiple reasons. First, the Netherlands has a rich history of engaged educational practices, such as the Science Shops movement in the 1970s (Dixon, 1988; Urias et al., 2020). Second, in the Netherlands, the expansion of core missions and visions are apparent across the whole spectrum of post-secondary education institutes from MBO (Simons et al., 2000; Geurts and Meijers, 2009) to HBO and WO (Meijs et al., 2019). Lastly, this expansion is informed and influenced by policy initiatives such as the City Deals on Education, which have fostered engaged educational projects in which cities (local governments), MBO, HBO, WO, civil society and / or the private sector collaborate to find solutions to pressing local social and urban challenges (see for example: Mees et al., 2019; Sibbing et al., 2021). Within the Dutch context, the city of Amsterdam is one of about 10 cities in the Netherlands in which WO, HBO and MBO are present.

Methodology

We conducted a qualitative research study focusing on individuals’ responses to the implementation of engaged education practices, when exposed to multiple institutional logics. The study was based on a combination of deductive, inductive and abductive reasoning, using interviews as the primary data-collection method. Specifically, we followed Eisenhardt (1989) approach to case studies to compare and contrast the experiences of 13 individual practitioners who design, coordinate, and/or teach engaged education projects in three Dutch (H)EIs. Through this approach, we were able to reveal similar processes occurring in diverse organizational contexts (Langley, 2007). This made it possible both to gain insights into how these individuals interpreted and responded to institutional complexity as well as to identify patterns associated with their responses.

Respondent selection

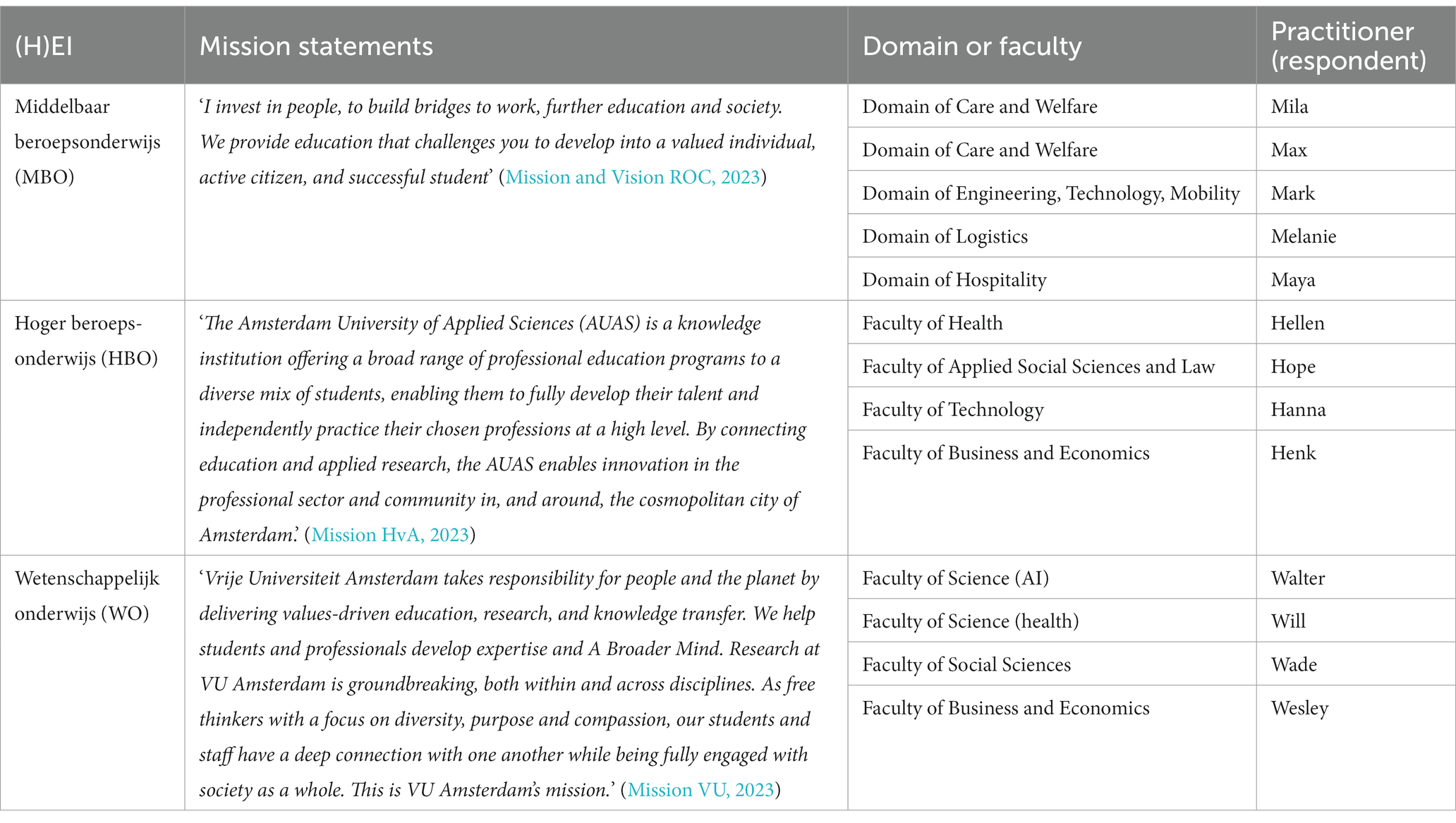

In this study we included one WO: the ‘Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam’ (VU), one HBO: the ‘Hogeschool van Amsterdam’ (HvA), and one MBO, the ‘Regionaal Opleidingscentrum’ (ROC) institute. Each institution has a mission statement that includes some kind of emphasis on the importance of embedding engaged education through engaged knowledge production and active citizenship. Among other terms ‘active citizen’ in the MBO, ‘enables innovation in the professional sector and community’ in the HBO and ‘fully engaged with society’ in the WO. For the entire mission statement for each institute see Table 2. We deemed it necessary to include institutions of the three post-secondary routes because each, in its own way, aims to contribute to social, economic, and cultural development in the region of Amsterdam. Furthermore, they all operate in the same landscape—as illustrated by the City Deals on Education—and are all exposed to the dominant field logics of market and corporation (van Houten, 2018).

Table 2. An overview of the included (higher) education institutions (H)EIs, the included faculty or domain, and the fictive name of the engaged practitioner (respondent).

Within each included institute, we used a purposeful sampling strategy (Merriam, 2015) to identify four to five engaged practitioners that work across diverse domains (in the case of MBO) or faculties (in case of HBO and WO). To safeguard anonymity, we refer to all engaged practitioners with fictional names starting with an M for the MBO institute, an H for the HBO, and an W for the WO institute. Respectively: Mila, Max, Mark, Melanie, and Maya (MBO); Hellen, Hope, Hanna, and Henk in (HBO); and Will, Wade, Walter, and Wesley (WO; see also Table 2). All practitioners included in the study were involved with an engaged education project. To qualify as an engaged education project, the project had to be part of a credit-bearing course that aims to contribute to a social issue in collaboration with an external social partner (based on: Bringle and Hatcher, 1995). Examples of issues addressed are: the direct support of elderly people by students in a health facility, the assistance of students in in financial matters such as tax returns, or creating an action plan for an external commissioner to increase individual sustainable consumer behavior. A description of all the included engaged education projects (anonymized and in random order) can be found in appendix A.

Data collection

In total, 13 in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with practitioners that design, coordinate, and sometimes teach engaged education projects within different institutional domains or faculties: five with practitioners from MBO, four with practitioners from HBO, and four with practitioners from WO (see Table 2). The interviews took place between January and May 2020. The interviews lasted for approximately an hour, and were, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, mainly held online through Zoom. All interviews were conducted by the first author. Interviews were held in Dutch and quotes were translated into English.

The interview guide builds on a systematic literature review of the process of embedding engaged education within (H)EIs. This review found that this process can be segmented into startup, scale up, and sustaining phases. The review concludes that the individual practitioners play an important role in embedding engaged education but also acknowledges the importance of organizational practices such as awards, promotion criteria, funding allocation, assessment, and formalization within educational structures (just to name a few).

At the start of each interview, respondents were asked to describe the design of, and the intentionality behind their engaged education project. So, what was the intention or urgency of the practitioner in starting this project? Subsequently, the respondents were asked to elaborate on their considerations in relation to organizational support related to policies and practices such as recognition, development programs, and allocated time. Lastly, respondents reflected on the possibilities for sustaining their project and the challenges they thought they might encounter in doing so. Therefore, reflecting together with the practitioners on their considerations in relation to the factors identified in this review for each phase, enabled us to outline their individual intentionality as well as their perception of the existing or desired organizational support or tensions when embedding engaged education. These considerations could then be associated with institutional logics (see next section) to allow for the consideration of how institutional complexity is experienced and responded to. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

All the transcripts were analyzed in ATLAS.ti 22. First, through deductive reasoning, we associated the field-level logics as identified by Cai and Mountford (2022; see Table 1) to the practitioners’ intentions and considerations relating to their perceived organizational support and tensions when embedding their engaged education project. For instance, when practitioners noted that their intentionality in the engaged education project was to attract more students and thus boost numbers, it was coded as: ‘adhering to market logic’. Alternatively, when a practitioner would note tensions in relation to work productivity or ranking when embedding their engaged education project, this was coded as: ‘conflicted by corporate logics’. This allowed us to associate field-level logics to individual intentions and considerations.

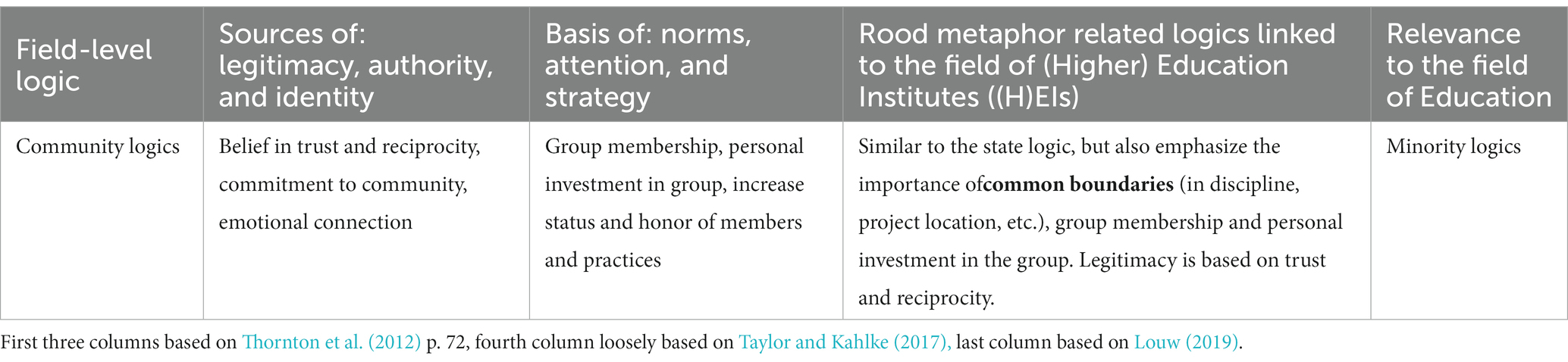

In parallel to deductive reasoning, we employed inductive reasoning to identify patterns in logics related to intentionality, conflicting logics and ways in which practitioners would deal with institutional complexity. By comparing and contrasting the experiences of those 13 individuals, we could identify one additional field-level logic that is not mentioned by Cai and Mountford (2022). This is described in the first part of the result section (see also Table 3 in the result section).

Table 3. Inductively identified field-level logics and the description in relation to (higher) education institutes ((H)EIs).

Finally, to better grasp how those individuals responded to the multiple logics that are available to them, as well as to better embed our findings in the literature, the last stage of our analysis consisted of an abductive reasoning approach which required a constant movement back and forth between theory and empirical data (Mantere and Ketokivi, 2013). Our initial empirical findings directed our search for additional literature that could offer theoretically-sound explanations to the emergent patterns that we observed by comparing and contrasting the responses of the 13 individuals in our study. Through this process of iteration between data and theory, we identified the study of Pache and Santos (2013; see also section 2), who developed a model that predicts which response organizational members are likely to activate as they face two competing logics.

We found that most of the individuals in our research activated responses (as well the associated roles attached to those responses) as modeled by Pache and Santos (2013). For instance, when a practitioner described purposefully segmenting their engaged teaching and research roles to deal with the bureaucratic organizational roles and structures, they were classified as taking the role of ‘compartmentalizer’. When a practitioner described how they combine their practices related to different logics, for instance by involving community in acquisition thereby adhering to increasing revues but also purposely contributing to community good, they were classified as taking the role of ‘combiner’.

By comparing and contrasting the responses of the individuals in our research, we found however, that the model of Pache and Santos (2013) could not predict all the patters that we identified in our empirical analysis. This led to further iteration with literature (e.g., Perkmann et al., 2019) that gave us a sufficient basis to propose explanations for responses and roles that we observed in our study and that were not yet represented in the literature in a way that corresponds to our study context. We describe those roles and responses in detail in the first part of our results section.

Ethical considerations

Participation in the study was on a voluntary basis. All parties signed an informed consent form before participating in the interviews. Participants were told that they could withdraw from the study at any stage if they wished to do so. Audio recordings and transcripts were stored on a safe drive that is password protected and can only be accessed by the researchers. After transcription, the audio recordings were destroyed. All data transcripts were anonymized. In accordance with the regulations of the VU Amsterdam the anonymized transcripts are stored for 5 years.

In adherence to the ethical standards established at VU Amsterdam, our research aligns with the prescribed conditions for human subjects, which encompass:

• Provision of comprehensive and accurate information regarding the research prior to participants’ involvement.

• Obtaining explicit consent from adults, who are cognizant of potential burdens or harm, and ensuring their voluntary engagement before the commencement of the research.

• Ensuring the confidentiality of acquired information through robust security measures and encryption.

• Conducting thorough risk assessments on data disclosure before making it accessible to others.

Moreover, our research adhered to the following guidelines:

• No envisaged harm to participants or the population from which participants were selected.

• Provision of detailed and accurate information to participants about the research objectives before their participation.

• Obtaining active consent from participants for their involvement in the research.

• Inclusion of healthy adults who are not in a vulnerable position as participants.

• Maintenance of confidentiality and secure storage of personal and sensitive data in a protected environment.

The study also adhered to the Code of Ethics for the Social and Behavioral Sciences of VU Amsterdam (2016). As a research undertaking classified as ‘standard’ and compliant with the established guidelines, further scrutiny by the Research Ethics Review Committee was deemed unnecessary.’

Results

Emerging outcomes from the comparison of individual responses

Through our deductive coding we associated individual intentions and perceived institutional support and tensions to the state, market, corporate, and professional logics (see Table 1). However, during our analysis, in which we compared and contrasted the 13 interviews, individual intentions as well as perceived tensions went beyond the categorization of these four logics. We found for instance, that some partitioners emphasized the need for non-hierarchical structures, common boundaries, and trust in relation to their engaged education projects. Though similar to the state logic, these considerations seem to fit better with the community logic (also defined by Thornton et al., 2012), as this logic particularly stresses the importance of common boundaries, trust, and reciprocity. We therefore opted to introduce a fifth field-level logic namely the community logic and coded this as ‘adheres to community logic’ (see also Table 3).

In addition, our analysis uncovered instances where the responses of engaged practitioners extended beyond the five patterns of individual responses outlined by Pache and Santos (2013) namely: Ignorance, Compliance, Defiance, Compartmentalization or Combination. Specifically, we found that some practitioners refused to compromise toward more dominant market or corporate logics of bureaucratic roles or increasing revenues, in order to protect the minority logics of, for instance, increasing community good. This response is different from the response of Defiance as described by Pache and Santos (2013), in which the minority logic is ignored. It is also different from the response of Perkmann et al. (2019) in which the dominant logic is shielded from the influence of minority logics. We therefore opted to introduce a new response namely: Protector. Within this response, practitioners not only adhere to minority logics (of state and community) and reject more dominant logics (of market, corporate, and profession), but also protect the minority logics from the influence of the more dominant ones. For instance, when a practitioner refuses to compromise in their flexible approach, going against rigid bureaucratic roles to protect their commitment to community—this response was coded as ‘protector’.

After comparing and contrasting 13 interviews through combined deductive, inductive, and abductive reasoning, we eventually identified five field-level logics that engaged practitioners might adhere to or be conflicted by when embedding engaged education, namely: state, market, corporate, professional, and community logics. Moreover, we identified four engaged practitioner roles within our study: Compliers, Compartmentalizers, Combiners, and Protectors.

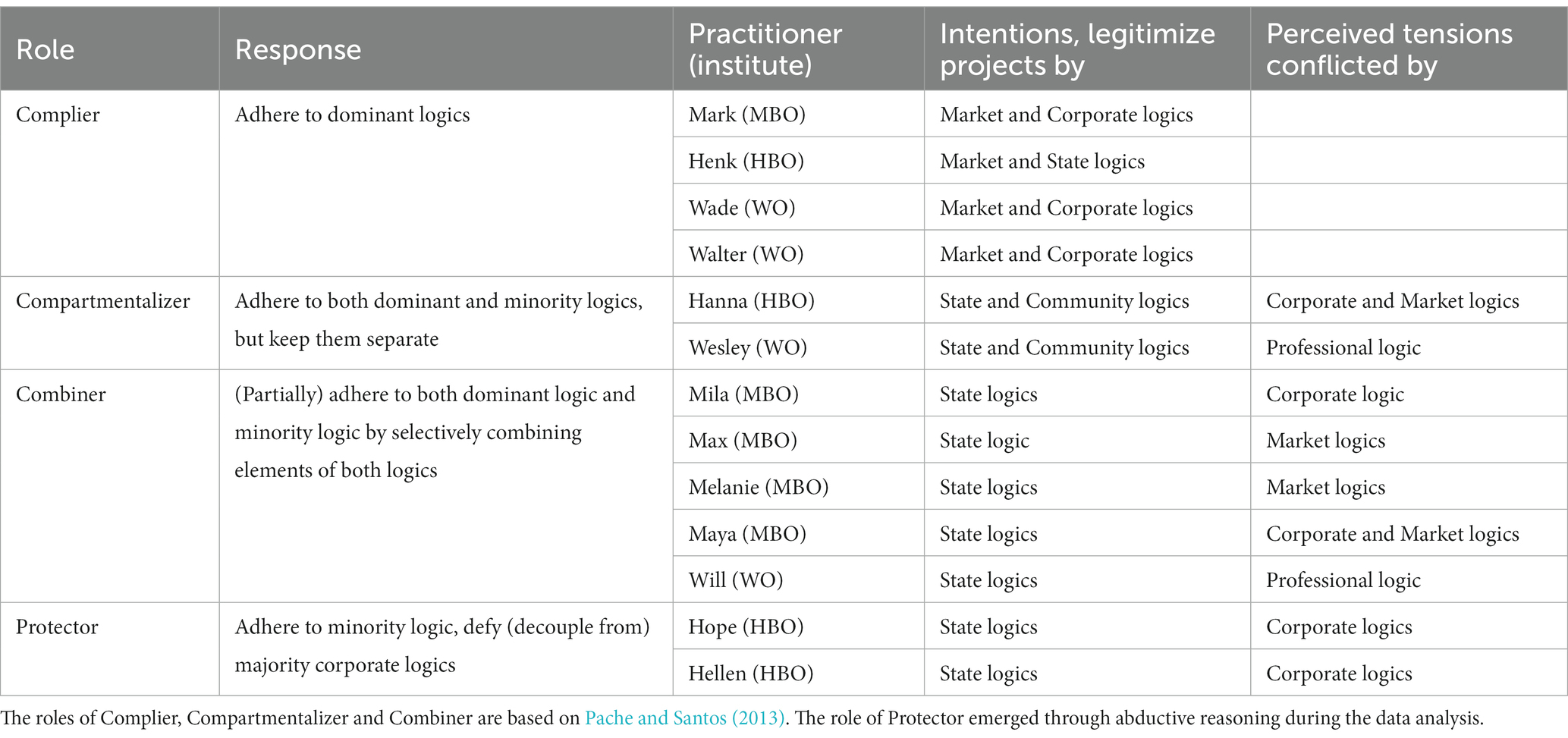

Engaged practitioner roles

We present the rest of the results section within the four roles that emerged after comparing and contrasting 13 interviews. Within each section, we describe the intentionality, institutional tensions and support (connected to their corresponding logic), and responses (if any) for each of the 13 practitioners included in this study. Table 4 shows an overview of each role and the related response, the name of the engaged practitioner, the logic associated with their intentions, and the logic they perceive as conflicting (if any).

Table 4. An overview of the roles, responses, engaged practitioners’ intentions and perceived tensions within different (H)EIs (MBO, HBO, WO) within Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Compliers

Compliers are practitioners who adopt the values, norms, and practices described by the most dominant logics and thus ignore minority logics (Pache and Santos, 2013). These practitioners therefore usually experience limited institutional complexity. We found that compliers often legitimize their engaged education projects by conforming to the dominant market or corporate logics that focus on employment, status, and increasing profits (see also Table 1).

For instance, Mark noted that he intended his engaged education project to attract more students, in order to deal with the growing need for employees within his sector. More specifically, he used the engaged education project as a way to promote and ratify the program, adhering to the corporate logic strategy of increasing size and diversification. Moreover, Mark stated that he intended the engaged education project to contribute to overcoming ‘language barriers’ between policy, government, and small and large companies. He pointed out that he often gave meaning to his engaged education project based on the external partners’ needs: ‘So, I always try to make that translation: what does a company need? And how can education respond to that? In doing so, he takes a more corporate and market-driven approach in relation to his intentionality in engaged education.

Henk noted that the engaged education project was intended to contribute to the students’ employability, saying: ‘I think we should use this more in education, because it’s just really good for the students.’ This focus on the students’ needs, preparing them adequately to the labor market can be associated with the market logic. Henk also noted that it was truly valuable for the students to gain insights into the various perspectives from the different parties they worked with during the engaged education project. For example, he could see how some stories had a big impact on the students, which opened their eyes and enabled them to withhold judgment. Thus, Henk viewed engaged education as having a transactional value through which students acquire different perspectives and valuable competences related to their future professions.

Wade and Walter’s original intent was to attract more students. As Wade commented: ‘we actually suspected that our education was not attractive enough, not interesting enough, and perhaps not distinctive enough.’ Wade continued by saying that engaged education helps students to develop a better idea of their future job perspectives and motivates and empowers them to make their own choices. Walter placed emphasis on the fact that engaged education can be seen as a unique selling point to differentiate their program from similar programs at other institutes. These intentions can be associated with market and corporate logics of ratification, increasing the number of students and their employability.

Walter also hopes that the engaged education project can assist in outsourcing supervision to partners, thereby increasing efficiency linked to the market logics strategy: ‘One solution [for the increase inflow of students] is to look for more external projects, because you can outsource parts of the daily supervision to that institution.’

So, even though we see different forms of complier behavior, this role is found in practitioners of all types of institutes: MBO (Mark), HBO (Henk) and WO (Wade and Walter).

Compartmentalizers

Compartmentalizers are individuals who segment their compliance with competing field-level logics by adhering selectively to elements of both dominant and minority logics while keeping them apart (Pache and Santos, 2013). In general, we found that engaged practitioners often segmented their practices when they legitimized their projects through the minority state logics associated with active citizenship and increasing community good.

For instance, Hanna’s intentions were to make students aware of social issues through her engaged education project, thereby increasing civic mindedness. Moreover, she sees engaged education as a strategy to build community capacity, as it can ‘draw attention to developing neighborhoods.’ In doing so, Hanna specifically emphasized the importance of a direct connection to the community. However, she noted that the importance of ensured continuity of the project, for which a mature process and, above all, patience are needed. She regarded one of the ways to ensure the continuity of such projects as being able to combine engaged education with engaged research. However, currently at the HBO institute she experiences bureaucratic separation between research and education roles. She comments: ‘It’s really two separate worlds, research and education,’ which she believes complicates combining the role of teacher and researcher. Moreover, she finds that, at times, researchers who conduct only research and do not teach can think too easily about how students can be ‘used’ for research purposes; ‘what I’m really allergic to is that students are used to collect data and that’s it… that’s not the intention! There should be some reciprocity.’ In a way, these researchers neglect the students’ learning which, consequently, jeopardizes the development of students’ civic mindedness. As a response, Hanna now separates engaged education and engaged research projects in the same neighborhood. Although there is some aspiration for combining such projects, the rigid roles in which researchers currently concern themselves mainly with research, without prioritizing students’ learning, do not (yet) allow for this.

At the WO institute, Wesley intended the engaged education project to somehow contribute to the community good, saying: ‘I hope to give something tangible back to the partner,’. He hereby adheres both to state logics as well as the community logics of finding legitimacy in benefits to the community. He reflected that, to safeguard this benefit and with that community good, it can be valuable to collaborate across different disciplines to address the issues from various perspectives. He was conflicted, however, by the professional logics, as his publications are mainly valued for career progression. Due to this focus, there was simply little or no time to invest more in the engaged educational practice. In response, Wesley reflected, for instance, that he does not see himself as a successful scientist per se as he does not put much emphasis on publications anymore. Although Wesley does not display full compliance with the dominant professional logic, to some extent he still adheres to its norms and values associated with the importance of scientific output—yet keeping it separate from the prescriptions of the minority logics to which he also adheres.

Thus, the main reason for engaged practitioners to take on the role of compartmentalizer was when the bureaucratic roles associated with the corporate logic (Hanna) within the HBO institute or professional logics conflicted with state logics (Wesley) within the WO institute.

Combiners

Combiners are practitioners who blend or assimilate values, norms, and practices from competing field-level logics. These practitioners rely on selectively coupling discrete elements drawn from each logic or on blending conflicting logics into a new logic (Pache and Santos, 2013). Thus, they enact a combination of activities drawn from each logic in an attempt to make sense of institutional complexity. By doing so, they can reconcile competing logics and secure endorsement from other field-level actors.

In MBO Mila noted that through the engaged education project, she intended to increase community good. She views engaged education as a means to directly contribute to assisting a specific target group. To her, engaged education projects require flexibility to quickly adapt to changes that take place in practice. She reflected that adapting swiftly to changing situations does not align with the prevalent hierarchical organizational practice, which gives managers the power to make their own decisions while they are often not directly involved with practice. Mila experienced increased institutional complexity reflected in the mismatch between the state logics with a strategy of increasing community good, and the corporate logics of hierarchical structure and bureaucratic roles. In response to this perceived tension between community and corporate logics, Mila initiated more frequent opportunities for knowledge exchange with her manager in order to deal with the hierarchical structure in their institution. As she commented: ‘what I do with [name of manager] now, is schedule a meeting once a week to translate the work floor to him. Because sometimes he is too far away [from practice].’ Her response complied with the prevailing hierarchical structure, but by adding elements of common boundaries of the community logic, she could foster knowledge exchange. This combination contributed to Mia’s achieving the intended goal of engaged education.

In his engaged education practice, Max intended that the project contributes to state logics of equal opportunities through redistributing community welfare. However, he was conflicted by market-driven, short-term project funding, which is often sought in relation to engaged education projects. This external, market-driven funding often has a duration of a maximum of five years. Max, for instance, noted that: ‘Even projects of which everyone says: ‘how great!’, then the question still is: but who will continue to pay for this…?’ He continued that this short-term external funding is a result of constantly shifting public funds, which are in turn dependent on the current political and market discourse in which one must operate with shifting resources. Max’s response consisted of adhering to those elements of market logic by continuously applying for funding, but with a slightly different angle. Thus, through reframing his approach to the social issue, he could use elements of the dominant logic to achieve goals of the minority logic to which he also adheres.

Maya intended the engaged education project to contribute to the state logics of democratic participation. She emphasized the importance of collaboration by ‘co-creating’ with companies and ‘applying for funding together’, thereby committing to community logics of group membership. However, she experienced competing field-level logics, as the main funding schemes do not allow social partners to be the main applicant. This hampers democratic participation and amplifies power imbalances. Also, the short-term nature of funding brings uncertainty about continuity and roles and responsibilities after the funding period. To reconcile those conflicting logics, Maya and the social partners involved in the engaged education project changed the project into a foundation after the initial 5 years of external project funding ended. Through this foundation, continuity of the project can be safeguarded: ‘In fact all partners have said “we will make a contribution,” they do not only do this in cash, but they also have a number of hours that they make available.’ Through this foundation, Maya could combine elements of state logics, such as democratic participation, with elements of the market logic, such as shared costs, referring to equal investment and gain for all parties involved. Although those elements remain intact, this combination led to a new, contextually specific form of collaboration, which promotes shared ownership.

Melanie’s intention for her engaged education project was primarily exploratory. There was an increasingly market-driven demand in her sector, and she wanted to explore openly how education could contribute to this. She noted that teachers can experience insecurity in an engaged education project, since they take on a slightly new and different role in these kinds of project, in which they coach more, rather than lecture, and which requires some improvisation on their behalf. As she commented: ‘the teachers who participated were also confronted with their own insecurity. You do not have a book, you do not have a method.’ Moreover, she noted that teachers feel little room to make mistakes, because their reputation depends, at least partly, on student ratings in numbers. Thus, elements of market logics that sees students as clients and accountability systems based on metrics are in conflict with elements of state logic. In response, Melanie started to involve teachers, students, and partners in redeveloping the curriculum: ‘It [co-creating the curriculum with partners, students and teachers] actually had a great effect because I think that there has just been an enormous awareness among many teachers of how it can be done differently.’ Melanie thus combined the corporate logic of bureaucratic roles (namely teacher, student, and partner) with the community logics of common boundaries, leading to a new way of working together. This resulted, according to her, in reducing teachers’ insecurities.

Apart from practitioners at the MBO (Mia, Max, Maya, and Melanie), we also observed the role of combiner in the WO organization. Will intended that his engaged education projects would enhance civic mindedness: ‘let students experience the social side of the profession’ relating to state logics. He also noted that, although redeveloping and redesigning his course to make it engaged was a major investment, this is not necessarily rewarded and recognized as a contribution to advancing his status in his profession. In response to the tensions between the state and professional logics, Will applied for the VU innovation prize together with a team that assists teachers in setting up and designing engaged educational practices in a university. This prize is a university-wide award for an innovative education project. The innovation was not by definition associated with engagement, but the professional logic of status was assimilated with engagement. Although the professional logics were still dominant, parts of the state logics therefore became associated with this logic. Will thus combined the professional logic of status with state and community logics, noting that the nomination for the VU innovation prize was important, as it provides the opportunity of framing community good as an opportunity to ‘succeed’ and demonstrate the value of what they have been working on: ‘[the nomination] is also good for your manager to see what you have done, and they appreciate that more. Because they [referring to management] actually have no idea how you spend your time.’

These deliberations clearly show the increased institutional complexity as the bureaucratic roles or market-oriented field-level influence clashes with the time-consuming effort of designing and coordinating engaged education projects through state and community logics. We find examples of combiners within the MBO and WO institute.

Protectors

Protectors are practitioners who take action to protect the minority logics to which they adhere to from challenging influences of values, norms, and practices of the dominant field-level logic. We found two such examples in the HBO institute.

Hope aimed to contribute to the community good with her engaged education project: ‘for me it is the [target] people who matter.’ She noted that to safeguard the community good, cross-disciplinary collaboration within, as well as collaboration beyond, the institute are needed to bring people together and create synergies. This aligns with the idea of common boundaries and the norm of group membership linked to the community logics (see also Table 3). She reflected, however, that collaboration across different departments is considered administratively challenging and therefore regarded by the management as complex, especially when deciding which faculty or institute is paying for your hours. Again, increased complexity appears to arise from the identity of bureaucratic roles associated with corporation logics versus the common boundaries associated with community logics. Moreover, Hope noted that engaged education projects bring uncertainty compared to simply fictitious cases as they need to adjust to the possible changing community needs in order to ensure benefits not only to students but also to partners. Hope suggested that the lack of managerial flexibility might come from a fear of this uncertainty:

‘It is also the culture of the institution, [..] maybe it has to do with that, a kind of penchant for uncertainty reduction. [...] I’m not going to give myself any problems, most managers think, so never mind.’

This quote suggests that Hope did not experience flexibility from the management level to give meaning to engaged education projects that are inherently uncertain. Institutional complexity arises as elements of community logics of ensuring shared benefits clash with elements of corporate logics of status and hierarchy and elements of market logics of efficiency and accountability. In response to this clash, Hope noted that, even though her way of working within engaged education projects does not fit within the frames of the dominant logics, she does not want to compromise as illustrated by the following quote: ‘At the HBO, we tend to want to incorporate it into systems very quickly, while it is precisely the creativity that arises in the edges and beyond.’ To protect her autonomy from the influence of corporate logics, Hope now seeks to apply for external funding that can allow her to continue her way of working, without having to conform to the bureaucratic roles of her institution. To Hope, this kind of response is necessary until the underlying organizational practices become more flexible and actively promote engaged education projects that value contributing to the community good.

Also in HBO, we found that Hellen adopted the role of protector as a response to a previous attempt to embed rationales of engaged education into prevailing organizational practices. Hellen hopes that her engaged education project contributes both to students’ civic mindedness as well as to the needs and goals of external social partners. To achieve this, she emphasized the importance of freedom in designing and coordinating such projects and the importance of active stakeholder involvement and equality. This can be associated with the logic of group membership and the attention to investment in groups, associated with the community logics. However, she was conflicted with bureaucratic roles and norms at the organizational level. She observed that the management would often perceive her project as an inconvenience due to differing needs and preferences compared to more conventional practices, such as requiring additional time and budget for travel. In response, Hellen tried to combine her practices with the organizational level as she formalized the concept of her engaged education project to be part of the accreditation criteria, meaning that her program would now officially become assessed on foundational elements of the engaged education project. Interestingly, she later abandoned this notion because those responsible for accreditation did not understand what the engaged education project was about:

‘As a program, we have a special feature: [name]. That’s a feature we officially wear since the previous accreditation [...]. But that, you know, we are almost letting it go a little bit again, but not because we let go of the system, but mainly because people [responsible for the accreditation] do not understand very well what it is.’

It appears that being part of the accreditation criteria was an example of decoupling, wherein organizations symbolically endorse practices prescribed by one logic while actually implementing practices promoted by another. The quote shows that Hellen did not feel that the values of students’ civic mindedness as social stakeholder involvement and equality were understood and/or shared by the dominant bureaucratic assessment carried out by the accreditation commission. Hellen thus felt it was necessary to separate the two.

Discussion

This study addresses the following research question: How do practitioners within different (H)EIs in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, experience and respond to institutional complexity within their engaged education practices? We investigated the intersection of institutional complexity, field-level logics, and individual responses by analyzing in-depth interviews with 13 practitioners from MBO, HBO, and WO who are involved in engaged education projects in which students, as part of their curricular activities, addressed a social issue in collaboration with an external community (partner; see appendix A for project descriptions).

Through comparing and contrasting the interviews, we found that these engaged practitioners differ in relation to logics that drive their intentions. Consequently, we found that the way those practitioners experience institutional complexity varies in degree and in the nature of the incompatibility of logics. This, in turn, influences what kind of role they adopt in response to the institutional complexity they experience. In addition to the previously identified field-level logics (Cai and Mountford, 2022) and individual responses (Pache and Santos, 2013) this study uncovered the significance of the community field-level logic and the role of Protector. Table 5 summarizes the main findings in relation to logics and responses within (H)EIs.

As the name suggests, compliers initiate their engaged education projects by complying with the dominant market and corporate logics. Compliers see engaged education as a means to respond to the demands of the labor market, to offer students better employment prospects, as a unique selling point to attract more students, and/or to increase the efficiency of their education by, for instance, outsourcing supervision. This role was observed in all three (H)EIs. Given the ongoing marketization of higher education, (H)EIs are often competing for students and confronted with prescriptions of new public management (NPM) (e.g., efficiency; van Houten, 2018). As the intentionality of compliers’ engaged education projects do not clash with those dominant logics, they experience limited institutional complexity in their practice.

The remaining roles, namely compartmentalizers, combiners, and protectors, refer to practitioners who experience some degree of institutional complexity for adhering to minority logics (i.e., state and/or community logics) that conflict to with field-level logics (i.e., market, corporate and/or professional logics) when initiating engaged education projects. Nevertheless, in line with the existing literature (Pache and Santos, 2013), these practitioners differ in terms of their responses.

Compartmentalizers were observed in the HBO and WO institutions. These individuals legitimize their engaged education by selectively adhering to different logics but keeping them apart. The practitioners experience the need to adhere to the prescriptions of professional and corporate logics in their other functions, especially in relation to research, that did not align with the state and community logics to which they adhere when designing and implementing engaged educational practices. This might explain why compartmentalizers were not prevalent in the MBO institute, as research plays a much less prominent role there. Practitioners in the HBO and WO reported the need to segment and favor increasing efficiency, bureaucratic roles, and individualism even when they would prefer to reject those elements of dominant logics and, instead, adhere to state and community logics in their research (e.g., moving away from traditional metrics, more recognition for social impact, more room for inter- and transdisciplinary collaboration).

This finding is in line with previous studies of Bromley and Powell (2017) and Kern et al. (2018), who note that contexts of institutional complexity such as universities are particularly propitious for segmentation or decoupling. Interestingly, this tension goes against the mission statement of the institutions. For instance, HBO notes that: ‘By connecting education and applied research, the AUAS enables innovation in the professional sector and community’ and within the WO: ‘Research at VU Amsterdam is groundbreaking, both within and across disciplines.’ This shows that adapting the strategic vision, although necessary, does not automatically translate to enabling individual practices (in line with Clark, 2017).

The role of combiner was observed in both the MBO and WO institutions. In the case of combiners, we could observe two distinct patterns, which were also reported by Perkmann et al. (2019): leveraging and hybridization. Leveraging refers to responses that draw upon dominant logic practices to achieve minority logic objectives (i.e., Mia, Max, and Melanie). Hybridization refers to the modification of dominant practices to allow engagement with the minority logic. Like Pache and Santos (2013), two forms of hybridization were identified in our study: (a) selective coupling, where intact elements drawn from each logic are combined (i.e., Maia); and (b) blending different logics leading to a contextually new logic (i.e., Will). In our study, we showed that Mia created a hybrid space that allowed for conflicting logics to co-exist in a way that her intentionality was not compromised. In WO, one practitioner sought to blend elements of state and community logics into the dominant professional logic, in such a way that the latter could be expanded by incorporating reward and recognition elements associated with minority logics.

Finally, the role of protector—which was only observed within HBO (Hope and Hellen)—refers to individuals who adhere to minority logics but who also refrain from compartmentalizing or combining conflicting logics. Those individuals responded to protect the minority logic from the influence of dominant logics, either to a perceived incommensurability of logics (i.e., protection by blocking) or the need to decouple from existing organizational practices associated with dominant logics (i.e., protection by segmentation). Existing literature has reported responses in which hybrid spaces can protect dominant logics against excessive minority logic influence (Perkmann et al., 2019). To our knowledge, this is the first time that individual responses aim to protect the minority logic from the influence of the dominant ones.

A potential danger associated with responses that rely on the combination of conflicting logics is that engaged education practices may have limited impact at the institutional level (Lounsbury and Pollack, 2001; Butin, 2006; Owen et al., 2021). Rather, existing norms and practices may be repositioned (Owen et al., 2021), possibly undermining the social impact of those institutions. Interestingly, the role of protector might have implications in relation to this commonly voiced concern, as individuals who resort to the role of protector refuse to compromise or to selectively couple, and thus challenge this effect. We argue that this role could be a promising bridge to strengthen the links between neo-institutional theory and transition studies. The transitions literature emphasizes establishing protected spaces for path-breaking innovations (i.e., niches) and have acknowledged strategies such as shielding, nurturing, and empowerment to create such protection (Smith and Raven, 2012). Thus, individual responses to protect minority logics may be a rich avenue for further investigation in relation to institutional change and system transformation in higher education and beyond.

Our study illustrates that engaged education is not a monolithic entity. There are different rationales driving the adoption of engaged education practices. In the dominant logic, engaged education is seen as a means to prepare work-ready graduates, and increase revenues and teaching efficiency. In the minority logic, engaged education is viewed as means to address social challenges or increase the students’ social, civic, and moral development. This has been reported in the literature both at the field and organizational levels (Lounsbury and Pollack, 2001; Taylor and Kahlke, 2017; Compagnucci and Spigarelli, 2020; LaCroix, 2022). Our research shows that individual practitioners also apply different rationales when designing and implementing engaged educational practices.

This study provides valuable insights in relation to possible directions for the process of change in (H)EIs. In expanding their core missions and visions toward contributing to social, economic, and cultural development, such institutes should be aware of the tensions experienced by individual practitioners and consider ways of dealing with, or catering for, them. At times of increasing discussions of the institutionalization of engaged research and engaged educational practices (Compagnucci and Spigarelli, 2020; Aramburuzabala and Cerrillo, 2023; Tijsma et al., 2023), it is important for (H)EIs to have a clearer vision of the material expression of the engaged practices they seek to institutionalize. This is essential for them to build the necessary institutional coherence that can steer and influence the individual actions, and associated roles, toward the desired vision (Fuenfschilling and Truffer, 2014). Investigating this topic through the lenses of the literature on institutional entrepreneurship may be a promising path to understand to what extent the roles we identified can be strategized to bring about institutional change toward distinct desired future directions.

Limitations and further research

The current study included only four to five examples of engaged education in each (H)EI. Although we conducted purposeful sampling strategies with the aim of including a variety of domains and faculties, we cannot draw conclusions at the institutional level of differences and similarities between the institutions based on such a selective and limited sample. Our aim was, however, not to map the institutional-level structures in their entirety, but rather to gain insights into how individuals within different (H)EIs in the Netherlands navigate institutional complexity when designing and coordinating engaged education. Future studies should consider whether the individual roles of Complier, Compartmentalizer, Combiner and Protector are more widespread. The exploratory nature of our study does not allow us to draw inferences about the relative frequency of those roles or which are more or less frequent in each institute that we considered. For instance, the fact that we did not identify combiners in HBO does not mean that they do not exist or that they are less prevalent in that institute. Conversely, the fact that protectors were identified only in HBO does not mean that individuals do not take on this role in other institutes.

Moreover, it should be noted that we did not take the background and contextual factors of the engaged practitioners into account when researching their responses. A recent study by Gautier et al. (2023) conducted 14 life-story interviews and showed the importance of contextual factors and the crucial role of individuals’ adherence to a certain logic. Similar to this study they considered how field logics influence individual responses. However, for Gautier et al., individuals were not embedded in an organizational setting and therefore the findings are bounded by an extra-organizational setting. It would be interesting for future research to apply the findings van Gautier et al. (2023) to the institutional and organizational field of education. For instance, we could not draw any conclusions about the individual and organizational factors that made those responses possible. At the organizational level, further research might examine how far factors such as position, job security (e.g., permanent versus temporary contracts), career stage, organizational (sub-)cultures, among others, influence the role and associated responses that individuals take when confronted by institutional complexity.

Conclusion

Our study illustrates that engaged education is not a monolithic entity and that individual practitioners adhere to different rationales when designing and implementing engaged education practices. Practitioners who initiate engaged education according to the dominant market or corporate logics do not experience institutional complexity, thus we refer to them as compliers. Conversely, those whose intentionality pursues the minority state or community logic take different roles in their response to the underlying institutional complexity. Such roles may refer to the adherence to multiple conflicting logics while keeping them apart (compartmentalizers), the (selective) combination of elements of dominant and minority logics (i.e., combiners), or the (partial) rejection of the dominant logic to protect the minority logic (i.e., protectors).

At a time of growing discussions on the institutionalization of engaged research and engaged educational practices, it is important for (H)EIs to have a clearer vision of the desired material expression of engaged practices within their own institutions. This becomes especially pressing when this material expression differs from the dominant logics and instead, is associated with the state and community logics, for instance through redistribution and common boundaries. Alignment of organizational practices is essential for (H)EIs to establish the necessary institutional coherence that can adhere to, steer, or influence individual actions and associated roles toward the desired vision. Further research on how different (H)EIs can institutionally embed organizational practices that are aligned with a plurality of individual material expressions of engaged education practices that follows the principles of state and community logics is still necessary.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

GT: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology. FD: Writing – review & editing. MZ: Writing – review & editing. EU: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Onderzoeksregeling City Deal Kennis Maken, Nationaal Regieorgaan Praktijkgericht Onderzoek SIA (onderdeel van NWO).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agasisti, T., Barra, C., and Zotti, R. (2019). Research, knowledge transfer, and innovation: the effect of Italian universities’ efficiency on local economic development 2006− 2012. J. Reg. Sci. 59, 819–849. doi: 10.1111/jors.12427

Aramburuzabala, P., and Cerrillo, R. (2023). Service-learning as an approach to educating for sustainable development. Sustain. For. 15:11231. doi: 10.3390/su151411231

Besharov, M. L., and Smith, W. K. (2014). Multiple institutional logics in organizations: explaining their varied nature and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 39, 364–381. doi: 10.5465/amr.2011.0431

Bringle, R. G., and Hatcher, J. A. (1995). A service-learning curriculum for faculty Michigan. J. of Comm. Serv. Learn. 2, 112–122.

Bromley, P., and Powell, W. W. (2017). From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: decoupling in the contemporary world. Acad. Manag. Ann. 6, 483–530.

Butin, D. W. (2006). The limits of service-learning in higher education. Rev. High. Educ. 29, 473–498. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2006.0025

Cai, Y., and Mountford, N. (2021). Institutional orders analysis in higher education research. Stud. High. Educ., 1–25. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2021.1946032

Cai, Y., and Mountford, N. (2022). Institutional logics analysis in higher education research. Stud. High. Educ., 47, 1627–1651.

Clark, L. (2017). “Implementing an institution-wide community-engaged learning program: the leadership and management challenge” in Learning through community engagement (Berlin: Springer), 133–151.

Compagnucci, L., and Spigarelli, F. (2020). The third Mission of the HEI: a systematic literature review on potentials and constraints. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 161:120284. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120284

Dixon, B. (1988). Selling research, and it pays. BMJ. Br. Med. J. 297:1416. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6660.1416

Durand, R., and Jourdan, J. (2012). Jules or Jim: alternative conformity to minority logics. Acad. Manag. J. 55, 1295–1315. doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.0345

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 14, 532–550. doi: 10.2307/258557

Friedland, R. (1991). “Bringing society back in: symbols, practices, and institutional contradictions” in The new institutionalism in organizational analysis, University of Chicago Press 232–263.

Fuenfschilling, L., and Truffer, B. (2014). The structuration of socio-technical regimes—conceptual foundations from institutional theory. Res. Policy 43, 772–791. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2013.10.010

Gautier, A., Pache, A. C., and Santos, F. M. S. D. (2018). Compartmentalizers or hybridizers? How individuals respond to multiple institutional logics. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2018, No. 1, p. 17953). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

Gautier, A., Pache, A. C., and Santos, F. (2023). Making sense of hybrid practices: the role of individual adherence to institutional logics in impact investing. Organ. Stud. 44, 1385–1412. doi: 10.1177/01708406231181693

Geurts, J., and Meijers, F. (2009). “Vocational education in the Netherlands: in search of a new identity” in International handbook of education for the changing world of work (Dordrecht: Springer), 483–497.

Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E. R., and Lounsbury, M. (2011). Institutional complexity and organisational responses. Academy of design and coordinatement annals 5, 317–371. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2011.590299

Kern, A., Laguecir, A., and Leca, B. (2018). Behind smoke and mirrors: a political approach to decoupling. Organ. Stud. 39, 543–564. doi: 10.1177/0170840617693268

LaCroix, E. (2022). Organizational complexities of experiential education: institutionalization and logic work in higher education. J. Exp. Educ. 45, 157–171. doi: 10.1177/10538259211028987

Langley, A. (2007). Process thinking in strategic organization. Strateg. Organ. 5, 271–282. doi: 10.1177/1476127007079965

Lounsbury, M., and Pollack, S. (2001). Institutionalizing civic engagement: shifting logics and the cultural repackaging of service-learning in US higher education. Institutions 8, 319–339. doi: 10.1177/1350508401082016

Louw, J. (2019). Going against the grain: emotional labour in the face of established business school institutional logics. Stud. High. Educ. 44, 946–959. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1405251

Lund Dean, K., and Wright, S. (2017). Embedding engaged learning in high enrollment lecture-based classes. High. Educ. 74, 651–668. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0070-4

McGregor, S. L. (2017). Transdisciplinary pedagogy in higher education: Transdisciplinary learning, learning cycles and habits of minds. Trans disciplinary higher education: A theoretical basis revealed in practice. 3–16.

Mantere, S., and Ketokivi, M. (2013). Reasoning in organization science. Acad. Manag. Rev. 38, 70–89. doi: 10.5465/amr.2011.0188

Mees, H. L., Uittenbroek, C. J., Hegger, D. L., and Driessen, P. P. (2019). From citizen participation to government participation: a n exploration of the roles of local governments in community initiatives for climate change adaptation in the Netherlands. Environ. Policy Gov. 29, 198–208. doi: 10.1002/eet.1847

Meijs, L. C., Maas, S. A., and Aramburuzabala, P. (2019). “Institutionalisation of service learning in European higher education 1” in Embedding service learning in European higher education (UK: Routledge), 213–229.

Merriam, S. B. (2015). “Qualitative research: designing, implementing, and publishing a study” in Handbook of research on scholarly publishing and research methods (US: IGI Global), 125–140.

Mission and Vision ROC (2023). Available at: https://www.rocva.nl/Over-het-ROCvA/Missie-en-beleid (accessed 29–08-23)

Mission HvA (2023). Available at: https://www.amsterdamuas.com/about-auas/profile/mission-and-vision/mission-and-vision (accessed 29–08-23)

Mission VU (2023). Available at: https://vu.nl/en/about-vu/more-about/mission-and-core-values (accessed 29–08-23)

Mitchell, T. D. (2008). Traditional vs. critical service-learning: engaging the literature to differentiate two models. Michigan J. Commun. Service Learn. 14, 50–65.

Owen, R., Pansera, M., Macnaghten, P., and Randles, S. (2021). Organisational institutionalisation of responsible innovation. Res. Policy 50:104132. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2020.104132

Pache, A. C., and Santos, F. (2013). “Embedded in hybrid contexts: how individuals in organizations respond to competing institutional logics” in Institutional logics in action, part B (UK: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.), 3–35.

Pache, A. C., and Thornton, P. H. (2020). “Hybridity and institutional orders” in Institutional hybridity: Perspectives, PMBOesses, promises (UK: Emerald Publishing Ltd)

Pekkola, E., Pinheiro, R., Geschwind, L., Siekkinen, T., Pulkkinen, K., and Carvalho, T. (2022). Hybridity in Nordic higher education. Int. J. Public Adm. 45, 171–184. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2021.2012190

Perkmann, M., McKelvey, M., and Phillips, N. (2019). Protecting scientists from Gordon Gekko: how institutions use hybrid spaces to engage with multiple institutional orders. Institution Sci. 30, 298–318. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2018.1228

Sandmann, L. R. (2008). Conceptualization of the scholarship of engagement in higher education: a strategic review, 1996–2006. J. Higher Educ. Outreach Engag. 12, 91–104.

Shea, L. M., Harkins, D., Ray, S., and Grenier, L. I. (2023). How critical is service-learning implementation? J. Exp. Educ. 46, 197–214. doi: 10.1177/10538259221122738

Sibbing, L., Candel, J., and Termeer, K. (2021). The potential of trans-local policy networks for contributing to sustainable food systems—the Dutch City Deal: food on the urban agenda. Urban Agricul. Regional Food Syst. 6:e20006. doi: 10.1002/uar2.20006

Siekkinen, T., and Ylijoki, O. H. (2022). Visibilities and invisibilities in academic work and career building. European J. Higher Educ. 12, 351–355. doi: 10.1080/21568235.2021.2000460

Simons, R. J., Van Der Linden, J., and Duffy, T. (Eds.). (2000). New learning (pp. 1–20). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Smith, A., and Raven, R. (2012). What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Res. Policy 41, 1025–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2011.12.012

Taylor, A., and Kahlke, R. (2017). Institutional orders and community service-learning in higher education. Can. J. High. Educ. 47, 137–152. doi: 10.47678/cjhe.v47i1.187377

Thornton, P. H. (2004). Markets from culture: Institutional logics and organizational decisions in higher education publishing. US: Stanford University Press.

Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., and Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional orders perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. UK: Oxford University Press on Demand.

Tijsma, G., Hilverda, F., Scheffelaar, A., Alders, S., Schoonmade, L., Blignaut, N., et al. (2020). Becoming productive 21st century citizens: a systematic review uncovering design principles for integrating community service learning into higher education courses. Educ. Res. 62, 390–413. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2020.1836987

Tijsma, G., Urias, E., and Zweekhorst, M. (2023). Embedding engaged education through community service learning in HEI: a review. Educ. Res. 65, 143–169. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2023.2181202

Urias, E., Vogels, F., Yalcin, S., Malagrida, R., Steinhaus, N., and Zweekhorst, M. (2020). A framework for science shop processes: results of a modified Delphi study. Futures 123:102613. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2020.102613

van Houten, M. M. (2018). Vocational education and the binary higher education system in the Netherlands: higher education symbiosis or vocational education dichotomy? J. Vocational Educ. Train. 70, 130–147. doi: 10.1080/13636820.2017.1394359

Vargiu, A. (2014). Indicators for the evaluation of public engagement of higher education institutions. J. Knowl. Econ. 5, 562–584. doi: 10.1007/s13132-014-0194-7

VU Amsterdam (2016). The code of ethics for the social and behavioural sciences of VU. Available at: https://bit.ly/41Dwowy

Keywords: institutional logics, engaged education, engaged practitioner responses, institutional complexity, roles

Citation: Tijsma G, Demeijer F, Zweekhorst M and Urias E (2024) Unraveling institutional complexity in engaged education practices: rationales, responses, and roles of individual practitioners. Front. Educ. 8:1310337. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1310337

Edited by:

Cheryl J. Craig, Texas A and M University, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Tijsma, Demeijer, Zweekhorst and Urias. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Geertje Tijsma, Zy50aWpzbWFAdnUubmw=

Geertje Tijsma

Geertje Tijsma Frederique Demeijer

Frederique Demeijer Eduardo Urias

Eduardo Urias