- Chair of Primary School Education, Institute of Pedagogy, Faculty of Human Sciences, Julius-Maximilians-University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany

The transition to school is a key juncture in an individual’s educational trajectory, with far-reaching effects on the development of children and their families. Successful transitions require flexibility in the design of the transition process, addressing the needs of the persons involved in an adaptive manner. Adaptivity is also considered crucial for the success of inclusive transitions. However, a systematic breakdown of the aspects that characterize the concept of adaptivity in the context of inclusive school entry is not available at this point. This article therefore provides a conceptualization of adaptivity in the inclusive transition to school as well as a review of the current literature focusing this topic. The goal is to develop a model that structures the various aspects of adaptivity at school entry and offers an overview of the way these aspects are important to design the transition successfully according to current findings of empirical research. Building on a concept of transitions informed by ecological systems theory, we are guided by the assumption that adaptivity at transition to school may occur in three forms: as a feature of the persons involved in the transition; as a feature of the processes that moderate the course of the transition; and as a feature of the structures that frame the transition. Based on this distinction, we develop a model that presents adaptivity in the inclusive transition to school.

1 Introduction

Adaptivity—i.e., the flexibility of pedagogical processes and structures as well as the ability to meet the needs of individuals within these structures and by shaping these processes—is among the core elements of successful school entry. Consequently, personalized measures to facilitate that transition can address the needs of the transition actors (Sands and Meadan, 2022) and ensure positive developmental trajectories if they are based on the specific circumstances of those involved. Likewise, adaptivity is key for making the transition from preschool to school1 an inclusive one (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023), i.e., a transition that leads to participation in mainstream primary (rather than special) school: Considering the individual needs of children and parents is essential when providing need-based support both to all children (broad concept of inclusion; Ainscow et al., 2006; Lindmeier and Lütje-Klose, 2015) and to children with disabilities and their parents specifically (narrow concept of inclusion; Lindmeier and Lütje-Klose, 2015) in the transition from preschool to mainstream school. Given that school entry is a predictor of future academic success (Crosnoe and Ansari, 2016), adaptivity is especially important at this point.

Although the transition discourse is clear about the relevance of adaptivity, it is less clear on how to conceptualize that construct (Pohlmann-Rother and Then, 2023). The only thing that existing conceptualizations seem to share is an understanding of adaptivity as flexibility in existing structures, which may be individual (e.g., cognitive structures) or ecological (e.g., design of learning environments or legislation). The goal of adaptivity is to create conditions that match the needs of children and parents by designing educational processes and trajectories catering to those needs. However, a current systematization that conceptualizes adaptivity in the inclusive preschool-to-school transition based on specific theories of school entry is missing at this point. Existing conceptualizations of adaptivity/adjustment2 either do not focus on that transition (Corno, 2008) or require supplementary concepts in light of current developments in research and society (Perry and Weinstein, 1998; Spencer, 1999). An update and reconceptualization of the construct of adaptivity in the transition to school is warranted primarily for the following reasons:

• Existing conceptualizations do not explicitly describe and specify the competencies needed by the actors involved (e.g., children, parents, teachers) to make the transition adaptive, even though current models of the preschool-to-school transition postulate that those actors play an active role in the process (e.g., Griebel and Niesel, 2009; Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023). The competencies the actors need for facilitating adaptive transitions, as well as the exact nature of these competencies, are thus essential for successful transition to school, i.e., a transition without adjustment problems both for the child/parents and for the school environment.

• In existing conceptualizations of school adjustment, parents are primarily considered as part of the context in which their child is navigating the transition. However, research findings show that parents also face numerous specific challenges when their child starts school (Dockett and Perry, 2004; Dockett et al., 2011; Ben Shlomo and Taubman-Ben-Ari, 2016) and experience a transition themselves (from being parents of a preschooler to being parents of a primary schooler) (Wildgruber et al., 2017).

• Existing conceptualizations do not explicitly draw on theoretical models of school entry to describe adaptivity in the processes moderating the transition (i.e., the interactions among transition actors). As a result, there is no specific link to transition theories. It is doubtful whether the processes specifically relevant to transition to school are sufficiently considered. However, the interactions between the actors are crucial for a successful transition (Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta, 2000). Paying specific attention to these processes is therefore of critical importance.

• Existing conceptualizations of adaptivity do not consider the context of inclusion. However, since the 2006 adoption of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities at the latest, inclusion has become a significant social transformation process that also affects the education system (Werning, 2014), including school entry.

To date, a systematic conceptualization of adaptivity that incorporates these developments does not exist. Thus, there is a gap between the assumed relevance of adaptivity in the context of inclusive school entry and the theoretical description of the concept. A conceptualization is needed that integrates theoretical perspectives and the results of empirical research and relates them to transition-related issues.

To address this research need, our goal in this paper is to design a model of adaptivity in transition processes that reflects the various facets of school entry and may guide future transition researchers by enabling them to specify the concept of adaptivity on which their work is based. For this purpose, we first clarify the basic terminology on adaptivity found in the transition discourse and derive our definition of the concept for this paper (section 2). Next, we present different perspectives from which adaptivity in the transition to school can be understood (section 3). From there, we develop a model of adaptivity for this transition (section 4). We conclude with an outlook on possible directions for future research on the preschool-to-school transition (section 5).

To be able to describe the special qualities of the inclusive transition in concrete terms, we focus on the example of a selected group—children with disabilities—and present the specifics of school entry for this group of children. Even if the model we develop is generally appropriate to describe the transition for all children (see section 4), our analysis thus follows a narrow understanding of inclusion, i.e., an understanding that focuses the social participation of children with and without disabilities in mainstream education system (Lindmeier and Lütje-Klose, 2015). Following the definition of the World Health Organization [WHO] (2001), the term “children with disabilities” is used hereafter to refer to children who experience long-term restrictions participating in society because of their specific physical, mental, and/or emotional condition.

2 Adaptivity in transition research: basic terminology

In the research on the transition to school, adaptivity (resp. adjustment) as well as adaptation (resp. adjustments) are considered critically important (Margetts, 2014). The transition is viewed as a process (Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta, 2000), which is accompanied by a number of changes (Griebel and Niesel, 2009; Vitiello et al., 2022a) and hence calls for adaptations to be navigated successfully. For that reason, the focus in transition research is on the adaptations that help the actors involved master this transition and give children a successful start to their school career.

The existing conceptualizations of the construct “adaptivity” are nonetheless characterized by inconsistencies. Aside from the term adaptivity, the term adjustment is especially common in empirical studies on school-related transitions, but it is not clearly and consistently distinguished from the terms adaptivity or adaptation (Lam and Pollard, 2006). Generally, there is no standard definition of the relationship of these two concepts in empirical studies: Some studies are based on terminology that does not systematically distinguish between the two concepts (e.g., Shields et al., 2001; Pratt et al., 2019); others draw on definitions that allow for systematic terminological distinctions, describing environmental adaption(s), for instance, as component(s) of the construct “school adjustment” (e.g., Sánchez-Sandoval and Verdugo, 2021). In these studies, school adjustment is presented as a higher-level process that requires individual “adaptations” at different levels and in different domains, including the school entry process. Perry and Weinstein (1998, p. 179), for example, describe school adjustment as a “multifaceted task, involving adaptation to the intellectual, social-emotional, and behavioral demands of the classroom and reflected in the development of specific competencies across the domains.” Spencer (1999, p. 43) refers to school adjustment as “the degree of school acculturation required or adaptations necessitated for maximizing the educational fit between the student’s qualities and the multidimensional character and requirements of learning environments.” An integration of the two concepts is discussed as well: Birch and Ladd (1996) point out that school adjustment includes adaptations both on the part of the child and on the part of the social environment. In the following, we build on this understanding: “adjustment” is hereafter understood as a process that may be realized through adaptations at different levels (individual, process, and society, see section 3). “Adaptations” are changes that occur in this context and lead to adjustment; “adaptivity” describes the general condition for these changes, i.e., the flexibility of individuals and contexts that forms the prerequisite for adaptations to occur.

This understanding may also be applied to the inclusive transition to school. Adaptation processes supporting the transition for children with disabilities and their parents have the same goal as supportive adaptation processes for all children: facilitating a seamless transition and a successful start to their school career. The developmental tasks that children and parents are facing in this context (Griebel and Niesel, 2009) may be more extensive and more complex than the developmental tasks of other children and parents. It is possible, for example, that children with disabilities must not only adapt to changes in their school environment but also to changes in other support systems (Janus and Siddiqua, 2018). Nevertheless, developmental tasks may generally be identified at the same levels as developmental tasks for all children and parents (Pohlmann-Rother and Then, 2023). Consequently, the construct “adjustment” also comprises adaptations at different levels in the inclusive transition of children with disabilities. These adaptations are specified in the next section.

3 Adaptivity: theoretical perspectives and implications for the transition to school

For the following systematization of adaptivity in the transition to school, we draw on Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological system theory and relate it to school entry (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023). The approach is suitable to differentiate different domains in which the concept of adaptivity is relevant (Hung et al., 2014) and different emphases that are used to describe adaptivity.

Bronfenbrenner (1979) breaks down the contexts of human life into different system levels that influence individual development. Based on Bronfenbrenner (1979) and transition-specific specifications of his developmental model (Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta, 2000; Griebel and Niesel, 2009), Then and Pohlmann-Rother (2023) identified three levels that are relevant for transition to school:

(1) The individual level, which is aligned with the microsystem level. This is where the actors involved in the transition (e.g., child, teachers) are found with their competencies and subjective perspectives.

(2) The process level, which corresponds to the mesosystem level. It includes the interactions between the actors, that is, the processes moderating the successful course of the transition (e.g., cooperation between preschool and school teachers).

(3) And the societal level, which serves as the foundation of the general social and educational policy framework of the school entry process, for instance through school entry legislation. This level corresponds to the macro- and exosystem levels.

Based on this systematization, it is possible to derive different perspectives that can be distinguished analytically and applied to explore adaptivity in the transition to school. If the focus is on the individual level, we study adaptivity in the competencies and perspectives of individuals. Here, adaptivity is a personal feature, that is, a competence possessed by an individual (section 3.1). At the process level, we analyze the adaptivity of the processes moderating the successful course of the transition. Here, adaptivity serves as a process feature (section 3.2). Finally, at the societal level, the focus is on the adaptivity of the structures that frame the transition. Here, adaptivity may be described as a structural feature (section 3.3). In the following sections, we provide detailed discussions of each of these three perspectives.

3.1 Individual level: adaptivity as a personal feature

When adaptivity is addressed as a personal feature, it is understood as an aspect of an individual’s agency. In this case, the term adaptivity is used to give a more precise description of the capacities that individuals need to master more or less specifically defined challenges in a manner adequate for the situation. This means adaptive competencies refer to capacities to navigate environmental challenges in an adequate manner (Koh et al., 2014).

For the transition actors—the child, the parents or families, the preschool teachers and school teachers, the members of the neighborhood (e.g., clubs, local communities), or additional service providers (e.g., therapists) (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023)—adaptivity may be specified as a personal feature from different perspectives. Below, we explain how adaptivity in the transition to school plays out as a personal feature for each of these actors.

3.1.1 Child, families/parents

For both children and their parents,3 the transition from preschool to school is a key milestone in their development (Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta, 2000). Adaptivity as a feature of the child and their parents thus describes their capacity to make adaptations in order to successfully navigate the transition as a developmental task. The adaptations that matter in this context may be described along the dual role that the child and their parents play at transition to school (Griebel and Niesel, 2009). On the one hand, the child and their parents are the addressees of support accompanying the transition; on the other hand, they are active agents in the transition process (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023).

As addressees of support accompanying the transition, it is up to the child and their parents to indicate their needs and to articulate those needs accordingly to the support structures in place (e.g., preschool teachers and school teachers, service providers). The needs thus expressed may, in turn, serve as a starting point for preschool teachers, school teachers, and service providers to offer adequate support to accompany the parents and support the child in the transition (see section 3.2). This is especially relevant in the context of inclusion, because the high degree of heterogeneity among preschool children means there is a great variety of specific needs and competence profiles (Petriwskyj, 2010), which need to be addressed in a way precisely tailored to each inclusive transition. Children with disabilities show particular needs when transitioning into mainstream school (Janus and Siddiqua, 2018). Shortcomings in the required support structures (e.g., insufficient continuity of support between educational settings) create barriers at this point, but are still found in practice (Janus et al., 2008; Daley et al., 2011).

As agents in the transition process, child and parents are challenged to make adaptations themselves to ensure a successful transition and to use the support they receive to address transition-related developmental tasks. The object of adaptation may be subject-related and may involve individual adaptations (i.e., adaptations of one’s own set of competencies or personality) to master the requirements in school. Possible examples include adapting one’s identity to the new role as schoolchild or parent of a schoolchild (Dockett and Einarsdóttir, 2017; Wildgruber et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2022) or expanding one’s set of competencies (Margetts, 2007). However, the adaptation processes may also be object-related, meaning they may require adaptations to the transition framework. For example, children and parents may articulate needs that initiate an adaptation of the existing support structures. It is possible, for example, that parents request additional counseling appointments, thereby initiating an adaptation of the counseling practice at the preschool or school. For such structural adaptations to take effect, it is necessary that the existing structures are sufficiently adaptive (e.g., allow for additional counseling appointments), since structural adaptations are only possible if the structures permit them in principle (see section 3.3).

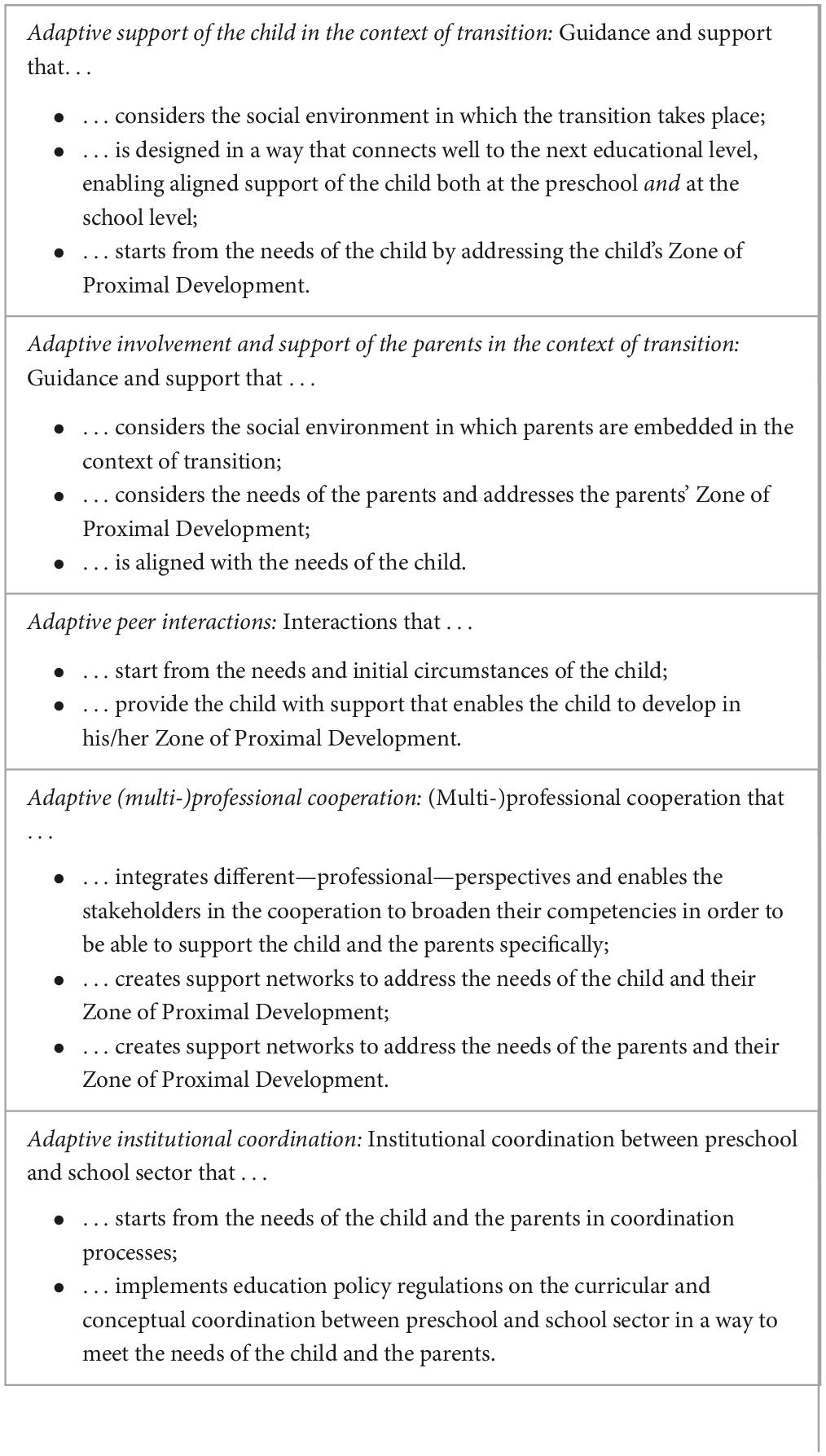

To successfully navigate the transition, the child and their parents therefore have both the opportunity and the responsibility to make adaptations. In this setup, the relationships between the child’s adaptations and those of their parents are reciprocal. For example, adaptations made by the children change their needs in the transition [e.g., if the child fails to expand their competencies in certain areas (individual adaptation) and develops a need for support in these areas]. The parents’ behavior, in turn, is guided by the child’s needs [e.g., support in developmental areas in which the child shows special developmental needs; or contacting the teacher to obtain additional support for the child in the corresponding developmental area (structural adaptation)]. At the same time, adaptations made by the parents to expand their own set of competencies influence their ability to support their child. This means both child and parents must be capable of making individual and structural adaptations to productively influence the transition to school. Furthermore, it is important that the child and the parents can use each other’s adaptations to facilitate their own transition. For example, parents might observe an increase in their child’s competence at school (and thus an individual adaptation of the child), gaining confidence and resources from this adaptation for navigating their own transition. Both aspects—the ability to make adaptations oneself and the ability to use the adaptations of others—together produce the child’s and the parents’ adaptation competence in supporting the transition. Figure 1 shows the interactions that constitute adaptation competence.

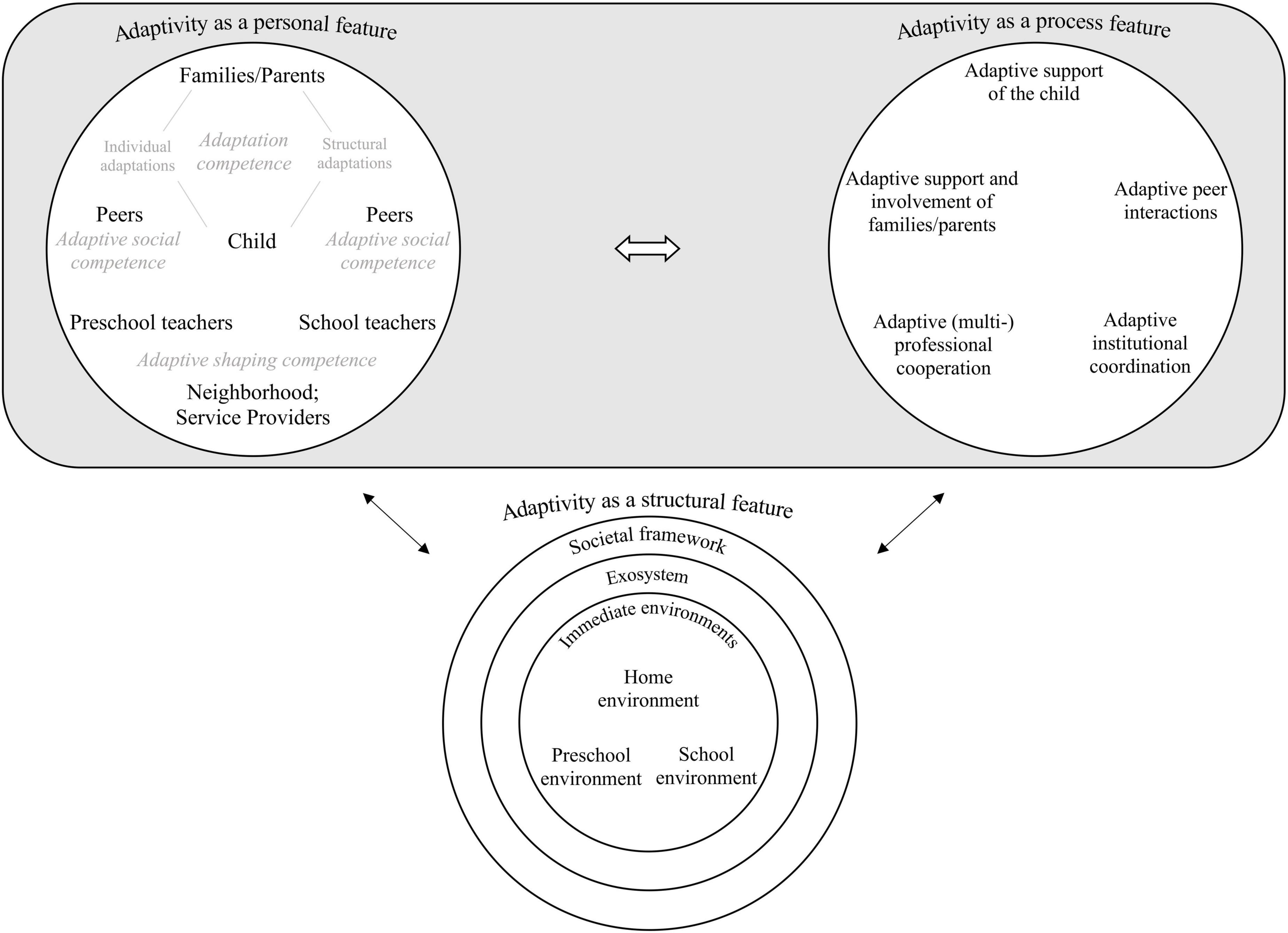

Figure 1. Components of the adaptation competence of the child and their families/parents in the transition (schematic).

When considering the inclusive transition to school of children with disabilities, it is the structural adaptations that are of special interest. One key prerequisite for inclusion to unfold as a process of social change is that existing structures can be adapted, and indeed are adapted, to individual needs (Werning, 2014). It is essential, therefore, that children and parents can adapt the structures and use that structural adaptivity to meet their needs. In this respect, children with disabilities offer a case in point: Both the children themselves (Janus and Siddiqua, 2018; Jiang et al., 2021) and their parents (McIntyre et al., 2010; Dockett et al., 2011) need special support in the transition and experience school entry as challenging. At the same time, additional support structures are crucial for the successful transition of children with disabilities and their parents (Pohlmann-Rother and Then, 2023). Consequently, the success of the transition essentially depends on the children and parents not only accepting the support of the existing systems (e.g., by taking advantage of preschool support services or existing counseling services) but also being capable of articulating needs that entail the expansion of existing support structures (e.g., by expressing a need for additional counseling).

3.1.2 Preschool teachers; school teachers; neighborhood and service providers

Preschool teachers, school teachers, and representatives of the neighborhood (e.g., clubs in which the child is a member, additional service providers) support the child and their parents in the transition. Aside from preschool teachers and school teachers, it is primarily the external support staff (i.e., the service providers such as therapists) who are directly involved in the daily educational interactions and hence directly relevant for the transition (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023). That is why our focus in this section is on the service providers in addition to the teachers. We concentrate on the professionals for whom supporting children and their parents in the transition is part of their professional profile. Adaptivity, as a characteristic of these actors, describes their capacity for making the educational processes that accompany the transition need-driven to the child and their parents (i.e., adaptive to the needs of the child and their parents) in order to enable a successful transition for the child and the parents and to perform a key professional responsibility.

In the effort to adapt educational processes to the specific needs of the child (and the parents), metacognition is considered an important prerequisite (Parsons et al., 2018). Metacognition refers to the ability to reflect on and regulate one’s own thought processes (Flavell, 1979). The main principle is thinking about one’s own cognitions (Veenman, 2017). In the teaching context, metacognition refers to the teacher’s ability to reflect on their own thought processes and on ways to adapt their own ways of thinking and acting to meet the needs of the child and parents (Parsons et al., 2018). Lin et al. (2005) refer to “adaptive metacognition” in this context.

For preschool teachers, school teachers, and service providers, the capacity for metacognition is a prerequisite for addressing the needs of children and parents in the transition. Professional adaptation thus requires prior reflection on adaptation needs and possibilities. The capacity for metacognition therefore also shapes the set of competencies that preschool teachers, school teachers, and service providers need to facilitate adaptive preschool-to-school transitions. The exact nature of these competencies can be derived from the aspects of adaptive teaching competence according to Beck et al. (2008) and Brühwiler and Vogt (2020). Although these aspects refer to the skills needed for an adaptive classroom and hence focus exclusively on school teachers, they can also be transferred to the transition context, making them equally relevant for preschool teachers and service providers. Specifying these aspects to the transition results in the following competence aspects in which adaptation is important/necessary:

(1) At the subject level, preschool teachers and school teachers, but also service providers, must be knowledgeable about the curricular requirements of the different educational sectors and keep them in mind when planning transition-related measures. Misconceptions and knowledge gaps, which have been shown to exist both among preschool teachers regarding the work done at schools (Bülow, 2011) and among school teachers regarding preschool work (Purtell et al., 2020), can act as an obstacle. Thus, knowledge about shaping transitions is significant at this point.

(2) At the level of classroom management, the main point is selecting and adapting appropriate pedagogical interventions to ensure a smooth (initial) classroom experience (Kounin, 1970) resp. transition. The main competence here is orchestrating transition measures, that is, arranging pedagogical and didactic measures in the transition adequately.

(3) Diagnosing students’ learning status is key to adaptive teaching (Hardy et al., 2019; Brühwiler and Vogt, 2020). Diagnostics are also essential to identify children’s and parents’ needs, as well as the needs for adaptation in the transition. At the same time, diagnostics are relevant to children’s performance development in the context of transition. Baker et al. (2015) have shown that the initial assessments of preschool teachers at the beginning of preschool predict children’s performance and performance development at the end of preschool—that is, at the transition. Children whose performance has been significantly underestimated show lower competence gains by the time they enter school. The diagnostics accompanying the transition play a key role at this point.

(4) Didactics accompanying the transition are important to facilitate the transition through the curricular coordination of learning opportunities between the educational sectors. For example, it is important that preschool teachers, school teachers, and service providers consider preschool learning contents and the children’s prior knowledge within the school context (Cohen-Vogel et al., 2021). The adaptive design of support processes for the child and the parents (see section 3.2) thus results from the ability to use didactic measures to support the transition in ways that address each student’s needs.

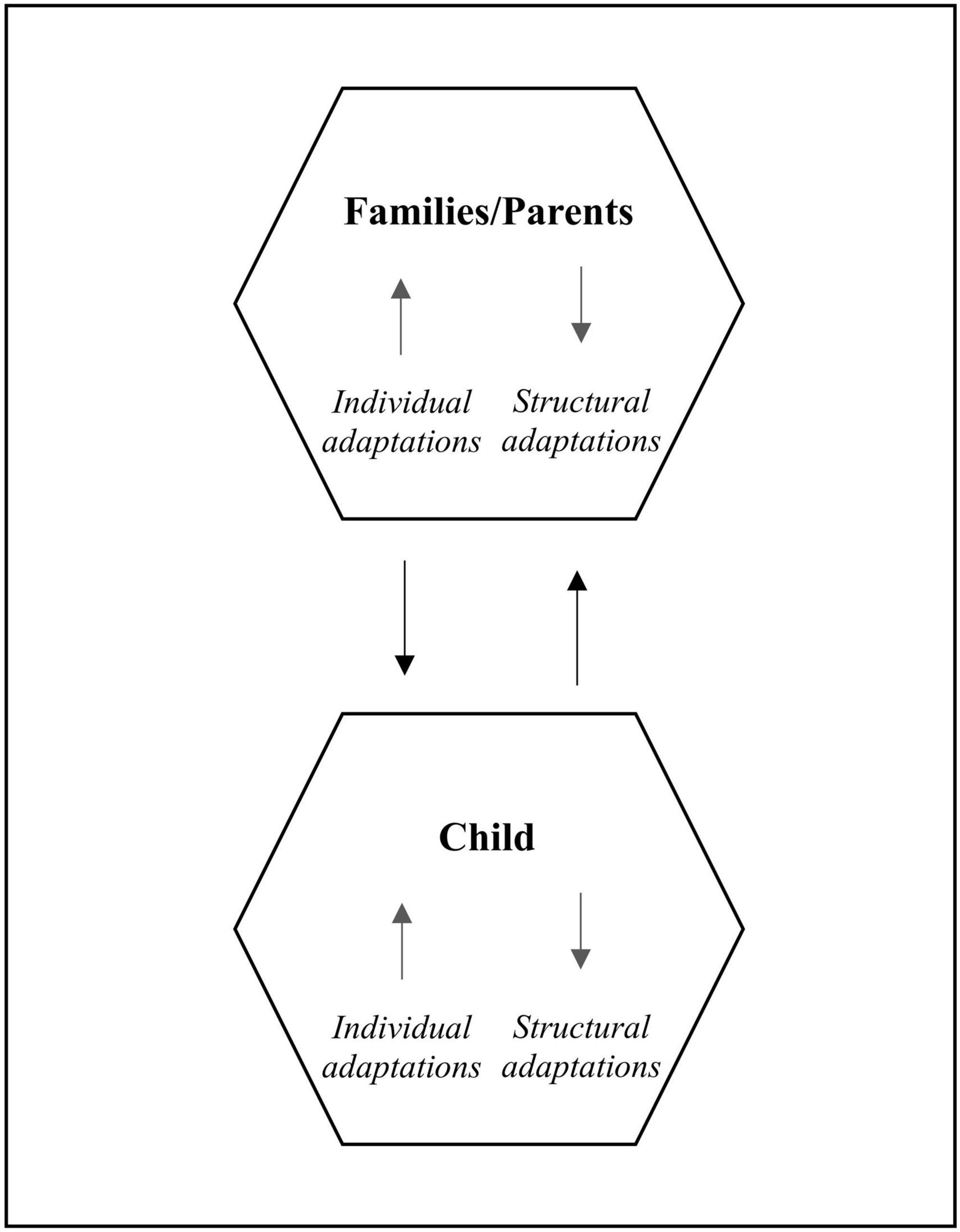

Based on the construct of adaptive teaching competence, these four aspects may be summarized as competence for shaping transitions adaptively, or transition-related adaptive shaping competence. One crucial aspect that frames these aspects, forming a higher-level fifth area of competence, is the capacity for cooperation in the transition. Long-term collaborative relationships among professionals (both among each other and with additional transition agents) are a major factor in facilitating successful transitions (Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta, 2000; Boyle and Petriwskyj, 2014; Wilder and Lillvist, 2018). These collaborations are also significant in the context of inclusion (Albers and Lichtblau, 2020; Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023). When children with disabilities enter mainstream school, (multi-)professional cooperation plays a crucial role (Rous et al., 2007; Sands and Meadan, 2022). The particular needs of children with disabilities, for example, are most likely to be met by involving professions with specific expertise in the transition process. Here, the capacity for cooperation is not only an important competence aspect in itself; it also impacts the other aspects. For example, the transition-related knowledge of preschool teachers and school teachers can be expanded through the cooperation of both groups. Figure 2 provides an illustration of adaptive shaping competence.

Figure 2. Facets of adaptive shaping competence [schematic, in orientation to Brühwiler and Vogt (2020)].

Adaptive shaping competence is characterized by specific connections, with didactics and diagnostics—following Beck et al. (2008) and Brühwiler and Vogt (2020), respectively,—forming the core of transition design. Being able to diagnose and precisely address children’s and parents’ needs in the transition is thus at the heart of adaptive shaping competence. Both areas are mutually dependent and influence each other: the didactic measures implemented in the transition are based on the learning requirements diagnosed earlier. At the same time, diagnostics is used to explore the effect of the didactic measures on the children’s development. Knowledge and the orchestration of measures create a conducive context for the transition. Successful transitions thus require knowledge of compatible educational processes between preschool and school and the ability to create an initial classroom experience without disruption. Cooperation in the transition serves as frame for the other competence facets and is itself a key transition-related capacity.

The importance of adaptive shaping competence is also and especially evident in the transition to school of children with disabilities. Children with disabilities have specific developmental needs during the transition that can vary greatly depending on the nature and severity of their disability (Bailey et al., 2019). Parents of children with disabilities face additional challenges when their children enter school (e.g., managing different support systems for their child), resulting in a higher need for support (Dockett et al., 2011). It is therefore particularly relevant that preschool teachers, school teachers, and service providers reflect on those needs to meet the individual needs of the child and their parents.

3.1.3 Peers

The child’s peers—i.e., children at the same grade level experiencing the transition together with the child—accompany the transition. They shape the social context in which the transition takes place and in which the child looks for guidance. In this process, the peers are expected by other transition participants to interact with the child in a stable manner and to support the child in navigating the transition. Adaptivity as a characteristic of peers, therefore, includes their ability to engage with the child in positive social interactions and to provide support for the child as needed in the context of the transition in order to meet the expectation that they will support the child. It is important to note that peers must navigate the transition themselves and are therefore—as children—also potential recipients of support.

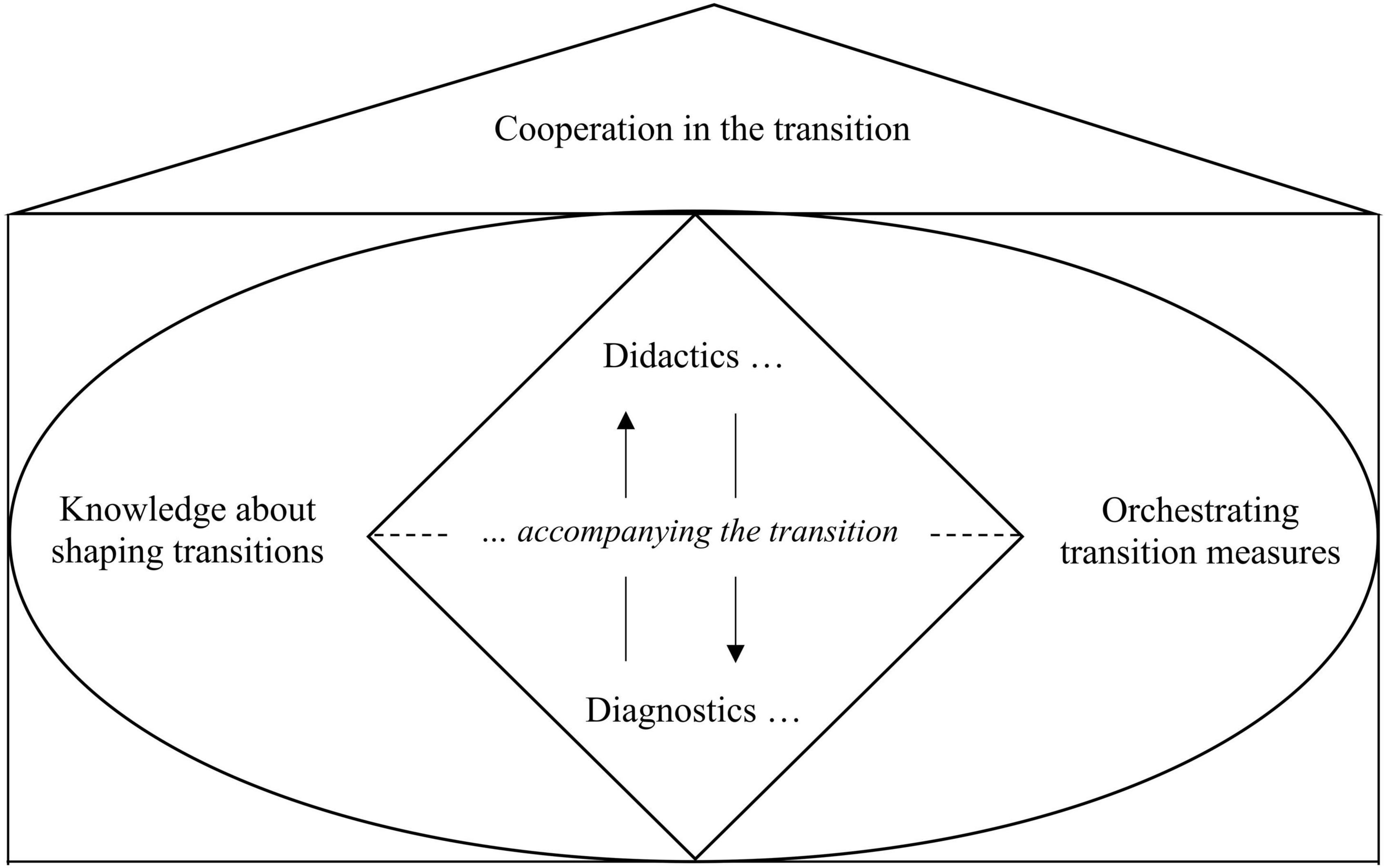

Peers’ social competence is essential when interacting with and supporting the child in an appropriate manner. Social competence, on the one hand, is an individual capacity made up of various sub-competencies. Gresham and Elliott (1987) point out two sub-competencies that constitute social competence: adaptive behavior—i.e., practical life skills (e.g., independence) and functional academic skills—, as well as social skills (e.g., communication). This leads to general, context-independent skills that peers need to interact with the child and that are generally significant for facilitating the transition.

On the other hand, social competence can be described as the fit between characteristics of the individual and those of the environment. In this context, Wentzel et al. (2014, p. 268) refer to social competence as “the achievement of context-specific goals that result in positive outcomes for the self but also for others.” The guiding assumption here is that social support is influential in achieving these goals and that peers may provide such support in their interactions with the child. Here, support may include (1) the communication of expectations and values, (2) instrumental help, (3) emotional support, and (4) safety from physical threat and harm (Wentzel et al., 2014). For the transition, this results in context-specific skills, that is, skills that are specifically relevant to the needs-driven design of the interactions with or to the support for the child in the context of the transition. According to Wentzel et al. (2014), the following specific skills of peers may be derived when it comes to providing needs-based support for the child in the transition:

(1) Peers can provide the child with positive expectations about school as well as values that promote school adjustment (e.g., values that endorse learning-related behaviors). This may result in positive feelings about going to school, which facilitate school adjustment (Hong et al., 2022).

(2) Peers can provide instrumental help to the child, such as helping with tasks during the first weeks and months in school. Aside from the positive effects for the child receiving support (Leung, 2015), peers also benefit in their own competence development (Leung, 2019).

(3) Peers can provide emotional support to the child. For example, peers can help the child process the changes in their family relationships brought on by the transition (Griebel and Niesel, 2009).

(4) Peers may offer the child safety from physical threats and harm, such as bullying. On the other hand, children who are rejected by their peers face a higher risk of becoming a victim of bullying (Sapouna et al., 2012).

The general, context-independent skills and the context-specific, transition-related skills can be combined into the construct of adaptive social competence. Figure 3 illustrates the construct, which is a significant prerequisite for adaptive peer interactions in the transition to school (see section 3.2.3).

Figure 3. Facets of transition-related adaptive social competence [schematic, in orientation to Gresham and Elliott (1987) and Wentzel et al. (2014)].

Peers are an essential factor in making the transition to school inclusive, i.e., leading to mainstream school participation (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023). First, interactions with peers, or support by peers, in the daily classroom environment can address the child’s needs directly, thus creating fitting and low-threshold resources that are relevant to the transition of children with particular needs. Moreover, peer acceptance itself is considered an indicator of successful school entry, also in the transition of children with disabilities (McIntyre et al., 2006). However, peer acceptance, especially in the context of inclusion of children with disabilities, is by no means a given (Woodgate et al., 2020; Schwab et al., 2021). Research findings show that children with disabilities face a higher risk of social exclusion by their peers (Broomhead, 2019). Therefore, in addition to adaptive social competence as the ability to interact with the child as needed, peers’ willingness to engage in such social interactions with the child is also significant. Research findings on peers’ attitudes toward inclusion indicate that the degree of willingness may vary greatly, however. When it comes to children with disabilities, that variance may depend on the type of support needed. For example, peers tend to have negative views of inclusive classrooms with children with social-emotional disabilities (Hellmich and Loeper, 2018), whereas the inclusion of children with physical disabilities is viewed more favorably in comparison (de Boer et al., 2012). In general, peers show more positive attitudes toward children with more obvious (e.g., sensory) disabilities than toward children with less obvious disabilities (e.g., learning disabilities) (Freer, 2021). In the transition, this results in the need to observe both the ability and the willingness of peers to support the child in navigating transition-related tasks. That is also because inclusion is not a professional responsibility for the peers (in contrast to preschool teachers, school teachers, and service providers), meaning they cannot be assumed to interact with children whose inclusion they oppose as a matter of principle.

3.2 Process level: adaptivity as a process feature

When looking at adaptivity as a process feature, the focus is on the adaptivity of the processes that moderate the successful transition trajectory. Adaptivity is thus not understood as a feature of an individual’s set of competencies but as a feature of the interactions that occur between the transition actors and that produce processes moderating the transition. The focus is on how closely these processes are adapted to the needs of the actors, and on how closely they can be adapted.

Five processes are relevant for the transition to the formal school system: (1) support of the child in the transition, (2) involvement and support of families/parents in the transition, (3) peer interactions, (4) (multi-)professional cooperation, and (5) institutional coordination between the preschool and school sectors (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023). The role of adaptivity in each of these processes is explained below. Before doing so, we outline the general theoretical framework that can be used to describe adaptivity as a process feature.

To systematize adaptivity as a process feature, Vygotsky’s (1962; 1978) theory of social constructivism offers a suitable basis. The theory of social constructivism focuses on the interactions between actors. These interactions are especially important when designing the transition, specifically at the process level, as the processes moderating the transition represent the interactions between the actors involved in the transition (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023). The theory of social constructivism is therefore particularly suited to describe adaptivity in transition-moderating processes. That is why we are using it here as our theoretical framework, out of the wealth of available theories referring to adaptivity (Aleven et al., 2017; Parsons et al., 2018).

The theory of social constructivism assumes that an individual’s development should always be considered in their specific social context. Learning in this context is a process of social construction, in which learners actively construct knowledge through their social interactions (Vygotsky, 1962). Learning processes are most successful when they take place in the “Zone of Proximal Development,” that is, if they address the developmental level the child is expected to reach next: where he/she will complete tasks unsupported that can currently only be performed with social assistance (e.g., from teachers or peers). Ideally, the child’s development takes place in this Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978). To enable a child to follow a positive developmental trajectory, it is important to adapt educational contexts in a way that the respective Zone of Proximal Development is considered (Parsons et al., 2018).

The transition to school is accompanied by a series of sweeping changes in the child’s and parents’ life and experience (Griebel and Niesel, 2009). Moreover, the transition occurs during a sensitive period of child development (Sameroff, 2010; Skinner, 2018). That is why the “Zone of Proximal Development” concept is especially important for school entry: The transition-moderating processes are most likely to lead to successful transitions if they enable the child (and their parents) to act in their Zone of Proximal Development. Adaptations that accompany the transition-moderating processes are therefore most promising if they are directed at the respective Zones of Proximal Development. Adaptivity in the processes moderating the transition thus refers to designing these processes according to the actors’ needs, addressing the Zone of Proximal Development of the child (and the parents). This has significant implications for an inclusive transition to school. The high heterogeneity in starting conditions of children (and parents) in inclusive transitions creates highly individual needs that shape the respective Zone of Proximal Development and must be considered when designing the transition. Children with disabilities may have very specific developmental trajectories depending on the severity of their disability (Bailey et al., 2019), which can strongly influence their Zone of Proximal Development and, consequently, the type and amount of support needed.

The specific ways in which adaptivity manifests at the process level in the context of the transition may be described by looking at each of the processes that matter in the transition.

3.2.1 Support of the child in the transition

From a socio-constructivist point of view, developmental guidance and support of the child in the context of the transition includes the social environment (i.e., preschool and school teachers, the neighborhood and social space—especially service providers—as well as parents and peers). Support measures that take account of the Zone of Proximal Development in a need-driven, adequate, and adaptive manner thus always include the social environment in which the child is embedded in the context of the transition.

The primary goal of adaptive support is to create adaptive educational contexts in preschool and school that address the child’s needs in both educational settings—that is, contexts that are adapted or adaptable to the child’s needs. Effective transition support thus starts from the needs of the targeted child (Sands and Meadan, 2022). One way to do this in a way that may be conducive for children’s learning is to provide support in preschool and school settings and gradually remove it based on the child’s changing needs, as in the classroom teaching technique of scaffolding (van de Pol et al., 2010). So, teaching measures based on scaffolding procedures are proven to enhance children’s learning (Sun et al., 2023) as well as their beliefs toward learning-related subjects within classroom settings (Abdelfatah, 2011). Applied to the preschool-to-school transition, preschool teachers, school teachers, and service providers might develop guidance and resources for the children, provide them to preschool children, continue to use them in the first time in school, and then gradually remove them to enable children to get along independently. As resources are gradually removed, peers and parents could be involved to support this process. The pace at which the resources are withdrawn may be based on the child’s individual needs. For children with disabilities, this applies accordingly. For example, a higher need for support in the transition (Janus and Siddiqua, 2018) may be accompanied by a more careful withdrawal of resources. Conversely, resources may be removed more quickly for children who need less support. Moreover, encouraging children to become independent and take ownership of their actions helps them activate their resources (e.g., specific competencies or knowledge) and incorporate them in the school adjustment process.

Furthermore, when designing support measures for the child in transition, it is important to be aware of the educational concepts of each educational sector and to ensure that the pedagogical work in preschool connects well to that in school (Stipek et al., 2017; Justice et al., 2022). This is where the “institutional coordination of educational sectors” is important to ensure that both institutions are closely aligned (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023; see also 3.2.5). To achieve positive support effects in the long term, it is crucial that the quality of support is also compatible, meaning that high-quality support in preschool is followed by high-quality support in school (Ansari and Pianta, 2018).

3.2.2 Support and involvement of parents in the transition

Parents are key actors in the transition and hence important to a successful school entry (Lau and Power, 2018; Puccioni et al., 2019). That is why getting parents involved and supporting them in the transition is essential to foster the course of the transition. There are two ways in which this is relevant: First, it creates resources for the child in the transition (Cook and Coley, 2017); second, involving and supporting parents is key to enabling parents to have a successful transition themselves (Wildgruber et al., 2017). In the context of the transition, therefore, it is essential to involve and support parents in a way that is adapted to the specific needs of the children, while also keeping the parents’ own circumstances and needs in mind and making adaptations as needed. Since parents also experience the transition as a period of profound change (Dockett and Perry, 2004; Ben Shlomo and Taubman-Ben-Ari, 2016) and have specific transition-related developmental challenges to master (Griebel and Niesel, 2009; Webb et al., 2017), they are also in a Zone of Proximal Development. Adaptations that preschool teachers, school teachers, and service providers make for parents in the context of the transition should therefore also consider their Zone of Proximal Development. As with the support provided to children, the social context is relevant for guiding and supporting parents. For example, parents may interact with parents of other children, thereby receiving additional support in the transition (Griebel et al., 2013).

In the context of inclusion, parents are an important source of support for the child. At the same time, they are a key source of information when it comes to identifying a child’s specific needs in the transition and addressing them appropriately. In addition, involving parents and coordinating support services at home with those in preschool and school is important to create an adequate transition for the child. Especially for children with particular needs, close coordination of parental and institutional support is crucial. It cannot be taken for granted, however: Parental involvement in the transition of children with disabilities has been shown to be lower when the child’s disability is more severe (Daley et al., 2011). Furthermore, in inclusive transitions, parents are also recipients of transition-related support. It is important to consider both the potential and the needs of parents and, for example, to provide more comprehensive support to those parents of children with disabilities who show a greater need for support in the context of the transition (McIntyre et al., 2010). Needs-based, transition-related counseling sessions are one possibility in this regard.

3.2.3 Peer interactions

From a socio-constructivist point of view, peers, or interactions between the child and peers, are crucial to child development. Peers can provide support and enable the child to engage in activities in their Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978). Peers are also relevant for successfully navigating the transition to school (Ladd and Price, 1987; Müller, 2015). Adaptive guidance in the transition process therefore requires that appropriate attention be paid to the interactions between the child and peers, ensuring that the interactions match the child’s initial circumstances. This requires that peers have adaptive social competence (see section 3.1.3).

In inclusive transitions, children with very different needs and abilities are enrolled in school together. The resulting high degree of heterogeneity in the student body gives rise to specific conditions for peer interactions that need to be considered. One example is homophily (Lazarsfeld and Merton, 1954), i.e., the tendency for children to form friendships with similar other children. Accordingly, research findings show that children with disabilities are more likely to form friendships with other children with disabilities (Schwab, 2019) and, conversely, children without disabilities are more likely to form friendships with other children without disabilities (Hoffmann et al., 2021). Social contacts between both groups, on the other hand, are less frequent (Banerjee et al., 2023). In addition, there is evidence suggesting that differences by type of disability exist and that such effects exist for children with learning disabilities, for example, but not for children with hyperactivity (Hassani et al., 2022). Since such group-specific inclusion and exclusion processes can undermine inclusion and the supportive role of peers in the transition, the child-peer interactions in inclusive transitions require close observation.

3.2.4 (Multi-)Professional cooperation

In addition to cooperation with parents, cooperation between preschool teachers, school teachers, and service providers as well as within these professions (i.e., (multi-)professional cooperation) is significant for successful transition to school (Ahtola et al., 2011; Dockett, 2018). Cooperation between—and within—the professions can create support networks from which support services for the child and parents can emerge. Such support can enable both child and parents to engage in activities in their respective Zone of Proximal Development. Therefore, viable collaborative relationships are guided by the child’s and the parents’ Zone of Proximal Development. To achieve this, the professions involved start from the needs and developmental potential of the children and parents, coordinate their perspectives, and adapt needs-based support measures to precisely address the child’s and parents’ circumstances in the transition. This requires that professionals are capable of cooperating with the other parties involved in the transition and of adapting the transition accordingly (see section 3.1.2).

(Multi-)Professional cooperation is especially relevant in the context of inclusive education (Lütje-Klose and Urban, 2014). Teaching children with very different and specific needs in the same classroom forces preschool and school teachers to broaden their own perspective by engaging additional (professional) perspectives to meet these needs and to align educational processes with those needs (see section 3.1.2). Conducive (multi-)professional cooperation that is guided by the circumstances of the individual child (and their parents) is thus a key condition for inclusive preschool-to-school transitions to be successful (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023). Accordingly, successful school entry of children with disabilities calls for (multi-)professional cooperation (Gooden and Rous, 2018; Sands and Meadan, 2022). In addition to the cooperation of professionals working in the facilities, cooperation with other members of the social space may also become relevant at this point. One option, for example, is getting representatives of the educational administration involved in the transition, thereby enhancing the transition process (Smith et al., 2021).

3.2.5 Institutional coordination between preschools and schools

Institutional coordination between preschools and schools (e.g., in curricular matters) is a major prerequisite for ensuring smooth transitions. Institutional coordination can help eliminate gaps but also redundancies between preschool and school curricula and ensure that children’s prior knowledge from the preschool level is adequately considered in school. Adaptivity in coordination processes therefore means taking the needs of the child and the parents into account when coordinating the educational work between the institutions and using those needs as the starting point. In practice, however, this is not always done successfully (Cohen-Vogel et al., 2021). Structural differences between preschools and schools (Vitiello et al., 2020, 2022a,b) make coordination between these institutions considerably more difficult. Accordingly, educational policies on the structure and institutional setup of these institutions are relevant for successful coordination, as is the legal framework for institutional cooperation between the preschool sector and the school sector. Curricular coordination, for example, is only possible if educational policies governing the contents of preschool and school teaching give leaders in both institutions the freedom to change their curricula accordingly (see section 3.3).

For inclusive transitions, it is essential that institutions have the capacity for flexible and adaptive coordination, which considers the needs of the child and the parents when designing the institutional framework. This concerns both curricular and conceptual aspects: If preschool education is individualized while schools insist on the principle of equal learning goals, it is more difficult to create a classroom experience guided by individual needs in the initial months and years of school. For children with disabilites, this involves a higher risk of experiencing negative developmental trajectories. Here, basic coordination between the institutions preschool and school at the management level is necessary, for example in curricular matters.

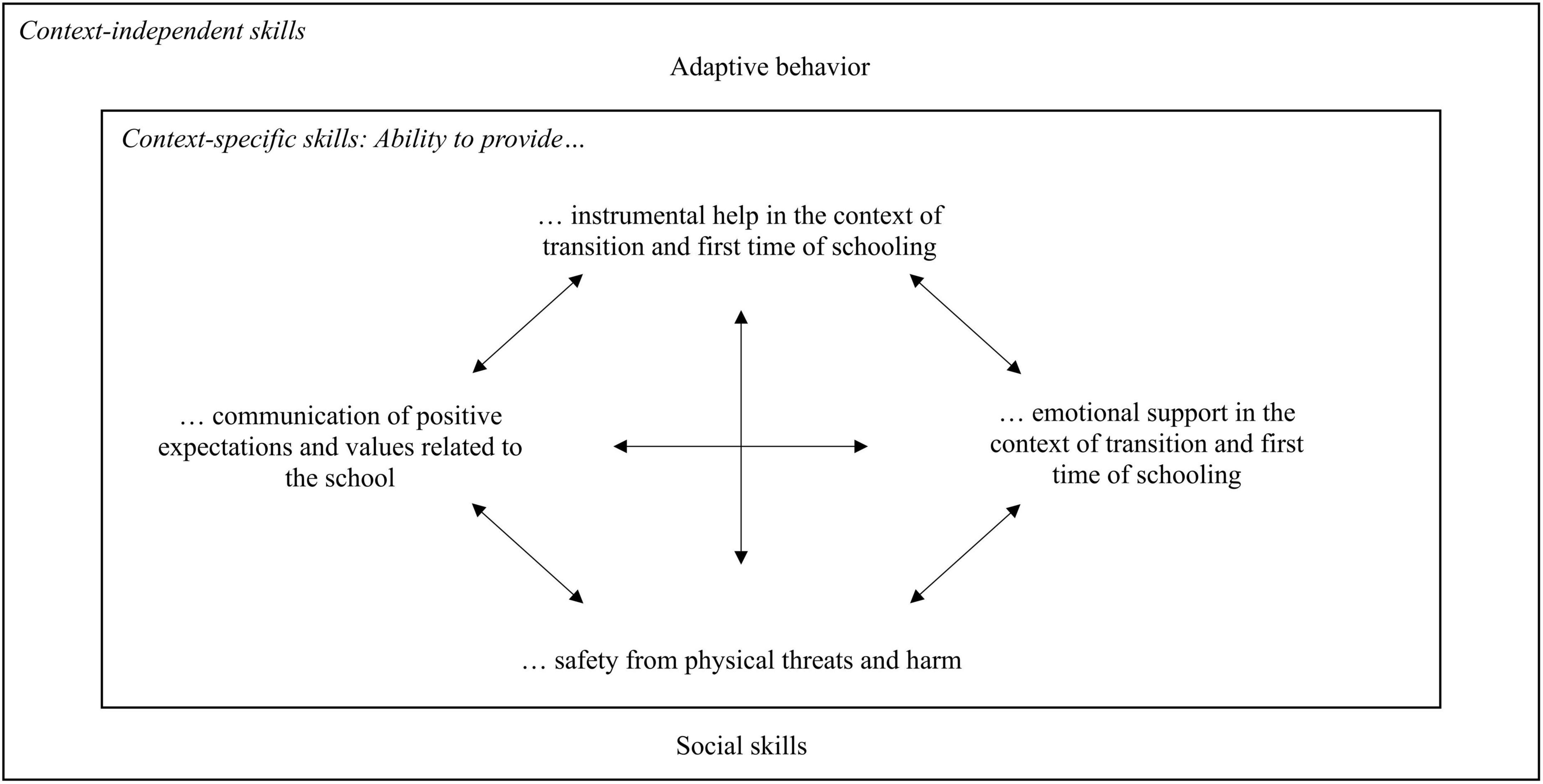

The previous explanations show that adaptivity at the process level refers to taking children’s and parents’ needs into account in the processes moderating the transition. Furthermore, they show that there are specific relevant aspects in the adaptive design of the single processes. Table 1 summarizes these aspects and lists the specific features that characterize transition processes as adaptive processes.

3.3 Societal level: adaptivity as a structural feature

Aside from its significance as an individual and process feature, adaptivity may be understood as a structural feature of social systems. From this perspective, adaptivity describes the degree to which the social framework can be adapted to the needs of individuals and to the specifics of the interactions between individuals. This concerns, for example, the extent to which current school enrollment laws allow for alternative school entry pathways for children with particular needs, such as disabilities. Adaptivity as a structural feature thus describes the flexibility of the (broader) context in which the transition takes place and which determines the options for action available to actors in the transition (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023).

To specify the role of adaptivity as a structural feature, Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) model of the ecology of human development itself provides a suitable basis. Here, the social context serves as the frame of reference for both individuals and the interactions between individuals in a given society. This means it defines the general patterns underlying the social order, which can be specified, for instance, by laws, but also, for example, by social norms or macropolitical decisions. The degree to which these patterns allow for considering the needs of the individual and the specifics of the interactions between individuals defines adaptivity as a structural feature.

Contexts that directly influence the development of individuals build on societal patterns and their manifestations (e.g., laws). Schools or preschools, for example, can only perform their educational work within the framework granted to them by applicable law. In their teaching, therefore, preschool and school teachers are free only insofar as the laws grant them freedom of action, provide for the consideration of individual needs, and are, in that sense, adaptive. Adaptivity as a feature of the general societal framework thus determines the adaptivity of the immediate environments (e.g., the school and preschool environment). The same applies to the exosystem of the individual. This includes any setting in which an individual is not directly involved and has no direct points of contact, but which nevertheless is important for the individual’s development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Policies at the parents’ workplace, for example, can give the parents freedom or impose constraints that may enable or keep them from supporting their child (in the context of the transition). The parents’ workplace is thus part of the child’s exosystem, because although the child is not an active participant in this area, the structures and activities of other persons in this area nevertheless have an impact on the child’s development.

For transition to school, adaptivity is relevant as a structural feature of (1) the immediate environments as well as a feature of (2) the exosystem, and (3) the general societal framework.

Immediate environments in which the child and parents are directly engaged in the transition process include the home environment, preschool environment, and school environment (Yelverton and Mashburn, 2018). Compatibility of the preschool and school environments, for instance in pedagogical or curricular matters, is essential for facilitating the transition (Petriwskyj, 2014) and has direct implications for the actions of preschool and school teachers. Here, adaptivity as a structural feature refers to the extent to which structures designed to coordinate both areas (e.g., joint preschool and school curricula) help ensure that children receive support based on their needs. Structural adaptivity as the basic flexibility of structures thus supports adaptivity in the corresponding transition-moderating process (“institutional coordination”). Another important factor for the child’s development and a successful transition is connecting the home environment to the institutional contexts—for example, by matching parental educational expectations with the requirements of the (pre)school sector. Research findings show, for example, that children whose parents believe school-related competencies to be relevant school readiness criteria show higher academic achievement on average (Puccioni, 2015; Puccioni et al., 2022). At the same time, the needs of children and parents in the transition can be met by taking their circumstances and perceptions into account when creating the (pre)school context. Consequently, adaptivity as a structural feature means aligning the home learning environment (e.g., home support for the child) with the requirements of the institutions while at the same time keeping institutional requirements flexible enough to allow for an alignment with the needs of children and parents. Again, structural adaptivity frames the adaptivity of the corresponding transition-moderating process (“parental involvement and support”). In the context of inclusion, institutional flexibility is of special importance: to accommodate the particular needs of children with disabilities as well as their parents, the structures in place must allow for far-reaching adaptive processes. For children with disabilities, for example, the extent to which preschool and school regulations allow for the involvement of additional service providers (e.g., therapists), including service providers from outside the institution, to accompany the children in the transition is a relevant aspect (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023).

Exosystem-level characteristics are also relevant to transition-related issues. The exosystem includes settings in which the child or parents are not actively involved, but which are nevertheless important for the development of the child and parents. For example, for the child in the transition, the parents’ workplace is part of the exosystem (Faust, 2013). Even though the child himself or herself is not an active participant in the parental workplace, the parents’ work situation nevertheless influences the support they can provide and thus the child’s development (see above). Adaptivity in the exosystem refers to the extent to which the needs of the child and parents are taken into account in areas of life in which they themselves are not active participants, but which are nevertheless relevant to their development. Through flexible working hours, for example, workplace regulations can enable parents to align their working hours with the needs of the children. In such an arrangement, parents could, for example, reduce working hours in periods when their child needs more intensive support and use the additional time to support their child. This means that structural adaptivity at the parents’ workplace is important for the child’s successful transition, even though the child is not a direct participant at their parents’ workplace.

The importance of the general societal framework for the transition to school process manifests primarily in the laws governing the transition, such as the regulations on postponed school entry. These regulations assume that children should not enroll in the formal school system until their development suggests they will succeed in school (Larsen et al., 2021). This assumption translates into legal guidelines that specify when parents or teachers have the authority to delay a child’s school entry. Delaying a child’s school entry, in turn, may impact the child’s development: they may benefit their socio-emotional development, for example (Hong and Yu, 2008). Adaptivity as a structural feature here concerns, among other things, the extent to which policies for delaying school entry help create a situation in which the individual child’s needs can be better catered to at a later point than at regular school entry. The general societal context is also important when it comes to inclusion. The main regulation here is the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations [UN], 2006) as an educational policy framework. In this document, the state parties commit to designing their social systems in such a way that people with disabilities are empowered to participate in society as much as people without disabilities. For children with disabilities, this means the fundamental right to equal access to mainstream education. Since equal participation requires needs-based participation, it is essential to meet the needs of children (and parents) in an adaptive manner at this point.

3.4 Preliminary conclusion

We have shown that adaptivity in inclusive transition to school may appear as a feature of the persons involved, of the moderating processes, and of the framing structures. When looking at adaptivity as a personal feature, the focus is on the actors involved in the transition, including their competencies and personal resources. When examining adaptivity as a process feature, we study the extent to which the transition-moderating processes are adapted, or can be adapted, to the needs of the child and the parents. Adaptivity as a structural feature refers to adaptations in the general conditions framing the transition.

Figure 4 summarizes these aspects of adaptivity in inclusive preschool-to-school transitions at each level. Given that activities at the individual and process levels are directly interrelated (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023), adaptivity as a personal and process feature also corresponds directly. This means that actors’ adaptive competencies at the individual level are a prerequisite for making the processes moderating the transition adaptive as well. At the same time, actions taken at the process level may influence the actors’ individual competencies, for example by stimulating the further growth of competencies. That is why adaptivity as a personal and process feature is shown in a common field in the figure.

Figure 4. Adaptivity in inclusive transition to school as a personal, process, and structural feature [simplified representation, in orientation to Bronfenbrenner (1979)].

The figure illustrates the features of adaptivity in inclusive transition-to-school practices in their specific forms. The extent to which these features are interconnected is explained in the next section.

4 Summary: model of adaptivity in inclusive transition to school

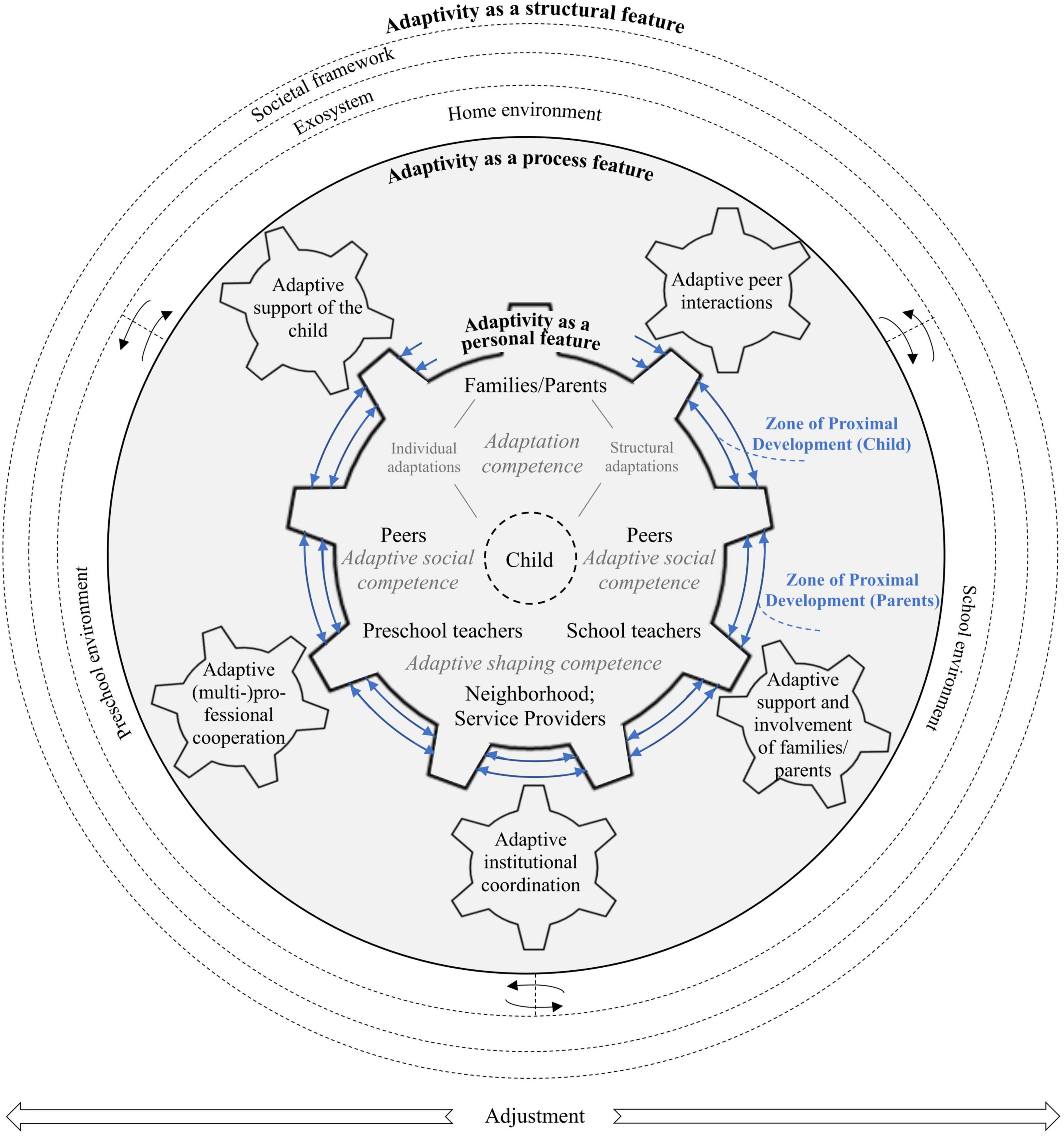

Adaptivity at the transition to school is a multifaceted construct. To conceptualize it, different aspects are relevant. Below, we break down these aspects systematically and combine them into a comprehensive model (see Figure 5). Building on the model of inclusive transition to school (Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023), the model is designed as a generic model. As such, it is suitable for describing adaptivity at school entry for all children. At the same time, it is possible to narrow the focus of the model and use it to represent adaptivity in the transitions of specific groups of children. In the previous sections, following a narrow understanding of inclusion, we demonstrated how this can be done specifically by using the group of children with disabilities as an example.

Figure 5. Model of adaptivity in inclusive transition to school [in orientation to Bronfenbrenner (1979) and Then and Pohlmann-Rother (2023)].

The basic structure of the model reflects the forms in which adaptivity can occur in the context of the transition to school:

(1) The core of the model is the individual level, i.e., the actors involved in the transition. Here, adaptivity occurs as a personal feature: it concerns the competencies of those involved in the transition (see section 3.1). The focus is on the extent to which the actors can make adaptations (to their own skillset and/or their environment) to address the tasks they face in the transition context. What matters for the child and parents is the extent to which they can make individual and structural adaptations to navigate the transition. The focus is on the adaptive competence of the child and parents in the context of the transition (see section 3.1.1). For preschool teachers, school teachers, and service providers, the focus is on the extent to which they can adapt the transition process for the child and parents, in other words: their transition-related adaptive shaping competence (see section 3.1.2). With respect to peers, the main aspect is the extent to which they can consider the child’s needs in their interactions with the child and support the child in the transition. Here, the peers’ adaptive social competence is essential (see section 3.1.3).

(2) The process level consists of the processes (i.e., the interactions between the actors) moderating the successful trajectory of the transition. Here, adaptivity occurs as a process feature, meaning it indicates the extent to which the needs of the child and the parents are taken into account in the transition-moderating processes (see section 3.2). The individual and process levels are directly interrelated (see section 3.4). Adaptivity as a personal and process feature therefore correspond directly as well (see also Figure 4).

To create a good fit between the transition-moderating processes and the needs of the child and the parents, it is crucial to address the child’s and the parents’ respective Zone of Proximal Development. This refers to the developmental area that the child or parent is expected to reach next: where they will complete tasks unsupported that can currently only be performed with social assistance. Transition-moderating processes are most developmentally beneficial when they allow the child or parent to engage in activities in their respective Zone of Proximal Development. Adaptivity in transition-moderating processes means designing the processes in such a way to enable the child and/or parent to engage in activities in their Zone of Proximal Development.

In the transition to school, five processes are relevant; making these processes adaptive is crucial for the transition to be successful (see also Table 1): adaptive support of the child (see section 3.2.1); adaptive support and involvement of parents (see section 3.2.2); adaptive peer interactions (see section 3.2.3); adaptive (multi-)professional cooperation (see section 3.2.4); and adaptive institutional coordination between preschools and schools (see section 3.2.5). Each of these processes can contribute to a successful course of the transition for the child and the parents. At the same time, the processes can interplay and promote a seamless transition in this way. In inclusive transitions, the starting conditions of the children and the needs of parents at school entry are particularly heterogeneous. Addressing the different initial circumstances of children and parents individually in the transition-moderating processes is a special challenge in this context, but doing so is essential for positive transitions.

(3) Unlike the individual and process levels, which affect the transition directly, the societal level creates the framework conditions for school entry and hence has an indirect effect on the transition. Here, adaptivity occurs as a structural feature (see section 3.3). The focus is on the contexts in which the transition takes place and on the extent to which the structures of these contexts allow for considering the needs of the child and parents in the transition. Three context levels are relevant here: first, the immediate environments, that is, areas that directly affect the course of the transition. These include the preschool environment, school environment, and home environment. Second, the child’s or parents’ exosystem—i.e., areas of life in which the child or parents do not become active themselves, but which are nevertheless relevant for their development—are also influential in the transition. Finally, the general societal framework is of major importance for the transition process. This is where macro-political decisions are made that determine the boundaries of what transition actors can or cannot do. For inclusive transitions, structural adaptivity is essential, because inclusion processes require that existing structures can be adapted to individual needs.

Adaptations in these three forms—as a personal feature, as a process feature, and as a structural feature—call for changes that result in a successful transition. The term adjustment describes the sum of all changes, i.e., adaptations that lead to successful school entry (see section 2). School adjustment thus refers to the process that is achieved through adaptations at the different levels and indicates the successful trajectory of the transition. Figure 5 summarizes these relationships in the form of a model.

5 Discussion and outlook

Making the transition-to-school process adaptive is a key prerequisite for its success. Yet, until now, no concept of adaptivity in inclusive transitions existed that adequately considered current scientific and social developments, while integrating theoretical and empirical perspectives and bringing them together in a coherent model. In this paper, we attempted to address this gap by creating such a model. The goal was to offer a detailed representation of the various aspects of adaptivity that factor into inclusive transitions and to highlight the relationships between these aspects. With this intention in mind, we developed the Model of Adaptivity in Inclusive Transition to School. The model illustrates where adaptivity matters in the transition process to ensure a successful transition for those involved, as well as the relevant forms of adaptivity at each point. It thus provides a theoretical basis for conceptualizing adaptivity in the inclusive transition to school. Empirical studies can use the model as a guide to help make explicit the form(s) of adaptivity they are interested in, for example. The model could be used to explain whether the focus is on adaptivity in the competencies of one or more individuals involved in the transition (adaptivity as a personal feature), adaptivity in one or more transition-moderating processes (adaptivity as a process feature), or adaptivity in one or more framework conditions of the transition (adaptivity as a structural feature). By referring to the model, researchers could also concretize the way a specific group of actors, a specific process, or a given structure is relevant in the transition. The model’s conceptual proximity to ecosystemic models of the transition process itself (Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta, 2000; Then and Pohlmann-Rother, 2023) provides a link for further theory-building.

In summary, the model can add to the discourse on adaptivity in the preschool-to-school transition and helps refine theory-building in this area. Nevertheless, it also has limitations: when designing the model, we drew on selected theoretical perspectives to derive implications for the transition-to-school process. However, there are other reference theories that might be used to conceptualize adaptivity in the transition, such as the perspective of ATI research (Cronbach and Snow, 1977; Corno and Snow, 1986; Corno, 2008). The model should therefore be understood as an attempt at systematization or a basis for discussion. It may be beneficial to discuss the model from other theoretical perspectives. Moreover, the model was developed based on theoretical considerations and available research findings. Further research could empirically test different components of the model (e.g., constructs such as “adaptive shaping competence” postulated here). Finally, the model focuses on the transition to school as a key milestone in an individual’s educational career (Crosnoe and Ansari, 2016). Subsequent research could relate it to other transitions in the educational career, such as the transition to secondary school or the transition to work. The model could thus serve as a starting point for establishing a theoretical foundation of adaptivity in transition research as a whole.

Author contributions

DT: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SP-R: Conceptualization, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Faculty of Human Sciences of the University of Würzburg as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Würzburg.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ In the following, we use the terms “transition to school,” “transition from preschool to school,” “preschool-to-school-transition,” and “school entry” synonymously, that is, to describe a child’s transition to the first formal and compulsory school-based setting he/she attends.

- ^ For a discussion of both terms—adaptivity and adjustment—as well as their relation see section 2.

- ^ Given that parents—aside from the child—are the family members who are the main agents in the transition and experience a transition themselves, the focus in the following is on the parents. To take account of the fact that other family members (e.g., siblings) may also impact the transition, the term “families/parents” is used in the model.

References

Abdelfatah, H. (2011). A story-based dynamic geometry approach to improve attitudes towards geometry and geometric proof. ZDM Math. Educ. 43, 441–450. doi: 10.1007/s11858-011-0341-6

Ahtola, A., Silinskas, G., Poikonen, P. L., Kontoniemi, M., Niemi, P., and Nurmi, J. E. (2011). Transition to formal schooling: Do transition practices matter for academic performance? Early Childhood Res. Q. 26, 295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2010.12.002

Ainscow, M., Booth, T., and Dyson, A. (2006). Inclusion and the standard agenda: negotiation policy pressures in England. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 10, 295–308. doi: 10.1080/13603110500430633

Albers, T., and Lichtblau, M. (2020). “Transitionsprozesse im Kontext von Inklusion - Theoretische und empirische Zugänge zur Gestaltung des Übergangs vom Elementar- in den Primarbereich,” in Kooperation von KiTa und Grundschule: Band 2: Digitalisierung, Inklusion und Mehrsprachigkeit - Aktuelle Herausforderungen beim Übergang bewältigen, eds S. Pohlmann-Rother, S. D. Lange, and U. Franz (Cologne: Carl Link), 198–225.

Aleven, V., McLaughlin, E. A., Glenn, R. A., and Koedinger, K. R. (2017). “Instruction Based on Adaptive Learning Technologies,” in Handbook of Research on Learning and Instruction, 2nd Edn, eds R. E. Mayer and P. A. Alexander (London: Routledge), 522–559.

Ansari, A., and Pianta, R. C. (2018). Variation in the long-term benefits of child care: The role of classroom quality in elementary school. Dev. Psychol. 54, 1854–1867. doi: 10.1037/dev0000513

Bailey, T., Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Hatton, C., and Emerson, E. (2019). Developmental trajectories of behaviour problems and prosocial behaviours of children with intellectual disabilities in a population-based cohort. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 60, 1210–1218. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13080

Baker, C. N., Tichovolsky, M. H., Kupersmidt, J. B., Voegler-Lee, M. E., and Arnold, D. H. (2015). Teacher (Mis)Perceptions of preschoolers’ academic skills: predictors and associations with longitudinal outcomes. J. Educ. Psychol. 107, 805–820. doi: 10.1037/edu0000008

Banerjee, C., Tao, Y., Fasano, R. M., Song, C., Vitale, L., Wang, J., et al. (2023). Objective quantification of homophily in children with and without disabilities in naturalistic contexts. Sci. Rep. 13:903. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-27819-6

Beck, E., Baer, M., Guldimann, T., Bischoff, S., Brühwiler, C., Müller, P., et al. (2008). Adaptive Lehrkompetenz: Analyse und Struktur, Veränderbarkeit und Wirkung handlungssteuernden Lehrerwissens. Münster: Waxmann.

Ben Shlomo, S., and Taubman-Ben-Ari, O. (2016). Child adjustment to first grade as perceived by the parents: the role of parents’ personal growth. Stress Health 33, 102–110. doi: 10.1002/smi.2678

Birch, S. H., and Ladd, G. W. (1996). “Interpersonal relationships in the school environment and children’s early school adjustment: The role of teachers and peers,” in Social motivation: Understanding children’s school adjustment, eds J. Juvonen and K. R. Wentzel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 199–225.

Boyle, T., and Petriwskyj, A. (2014). Transitions to school: reframing professional relationships. Early Years 34, 392–404. doi: 10.1080/09575146.2014.953042

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Broomhead, K. E. (2019). Acceptance or rejection? The social experiences of children with special educational needs and disabilities within a mainstream primary school. Education 3–13 47, 877–888. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2018.1535610