94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 20 December 2023

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1303765

This article is part of the Research TopicAdvances and New Perspectives in Higher Education QualityView all 17 articles

Introduction: In recent years, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the entrance and development of university life has become a complex process, making it relevant to investigate which variables could facilitate the adaptation of young people to university. This study aimed to analyze academic emotions and their prediction of university adaptation and intention to drop out.

Methods: The study was quantitative, explanatory, and cross-sectional. A total of 295 university students participated. Academic emotions were assessed with the short version of The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire, adaptation to university life with the reduced version of the Student Adjustment to College Questionnaire, and intention to drop out with three items designed to measure this variable.

Results: Differences were identified in the emotions experienced during classes and study by students according to the year of entry. We found that males report experiencing emotions such as enjoyment and hope more during evaluations.

Discussion: Generally, students report positive emotions in their academic experience. Positive emotions predict adaptation to university life and the intention to study.

Due to the consequences generated by the COVID-19 pandemic, students entering universities during the last years presented essential changes in how they experienced their university entrance. In this context, academic adaptation has been considered a fundamental problem for today’s educational system Shamionov et al. (2023). This set of changes in young people has been overwhelming and has had significant effects on various aspects of their training, especially on how they adapted to university life and the effects of this on university dropout.

Adapting to university life has been defined as the student’s ability to adjust effectively to the challenges encountered in the new university environment (Crede and Niehorster, 2012). This variable is considered an important indicator of academic success and permanence of students (Pérez et al., 2020). For the achievement of an adequate integration into university life, empirical evidence has shown that contributing to the adaptation of young student’s elements such as emotions, wellbeing, and perception of support is essential for their development, and this is because during the transition processes students experience emotions such as anxiety, hopelessness, worry, and stress (Chan and Rose, 2023; Hako et al., 2023). Adaptation to university life is critical to permanence and depends, from the student’s point of view, on the social experiences and resources that the student uses at the university (Van Rooij et al., 2018).

When students have difficulties adapting to university, they may present thoughts associated with dropping out of their studies (Galve-González et al., 2022). Dropping out of university studies is one of the current problems of higher education (López-Angulo et al., 2023). Figures in Chile, where this study was conducted, show that the student dropout rate increased by two percentage points in 2020, exceeding 25% (SIES, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on the educational system. In this case, it generated a negative impact in terms of the social and academic experiences of young people when entering their university careers, affecting the academic performance of students, their achievements, and their emotional wellbeing (Casanova et al., 2022; Galve-González et al., 2022).

The intention to abandon studies is considered an early warning sign of university dropout, and it is possible to characterize it by feelings of apathy toward studies manifested by non-attendance to classes, procrastination in the delivery of work or not taking exams (Jacobo-Galicia et al., 2021). It can also be defined as those ideas, desires, and intentions associated with the possibility of withdrawing from one’s career before graduating or leaving a higher education institution (Díaz-mujica et al., 2018).

In recent years, research has sought to contribute to identifying issues related to students’ educational experiences in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this regard, a recent bibliometric review indicated that mental health and wellbeing were among the most researched topics in the university context during the pandemic (Aristovnik et al., 2023). In that line, research has shown how academic emotions contribute significantly to the adaptation and success of university students (Zhang et al., 2021). Additionally, it has been found that students who experienced the remote teaching emergency produced by the pandemic have reported a more significant presence of negative emotions such as anxiety, stress, and boredom, which may impact their adaptation process (Wu et al., 2022).

Emotions are an intrinsic part of everyday life for all human beings and are ubiquitous in academic settings (Pekrun, 2016), yet over the years, educational researchers have tended to neglect the role they play in students’ lives, focusing exclusively on cognitive, motivational, and behavioral constructs (Ganotice et al., 2016). The emotions correspond to a multidimensional process of short duration that generates diverse responses in the organism as a reaction to internal or external stimuli with biological, behavioral, and cognitive implications (García-Álvarez et al., 2019).

To understand the importance of emotions in academia, it is essential to recognize that they involve sets of coordinated psychological processes that include affective, cognitive, physiological, motivational and expressive components (Pekrun, 2016), having particular relevance the cognitive component of every emotional process, which consists of the interpretation and evaluation of objects, situations or people, to which neurophysiological reactions are associated (Bzuneck, 2018).

The connection between teaching-learning processes and emotions has given rise to the concept of “academic emotions,” which is understood as those emotional experiences (e.g., enjoyment, pride, anxiety) that are directly related to academic learning, classroom instruction, and performance (Pekrun and Perry, 2014). These emotions can be grouped according to their valence of activation. Valence refers to the extent to which an emotion is experienced as pleasant or unpleasant. At the same time, the activation dimension determines the state of physiological arousal, distinguishing between activating and deactivating emotions (Martínez-López et al., 2021b).

According to Lei and Cui (2016), it is possible to group emotions considering their valence arousal, managing to distinguish four groups: (a) high arousal positive emotions, including enjoyment, hope, and pride; (b) low arousal positive emotions including satisfaction, calm and relief; (c) high arousal negative emotions including anger, anxiety and embarrassment; and (d) low arousal negative emotions including hopelessness, boredom, depression, exhaustion and discomfort (Lei and Cui, 2016).

The following groups of academic emotions based on the object approach have been established, which can be identified as (a) achievement emotions, both to the activity and to the outcome, being possible to identify that the results can be past or future-oriented, in the dimensions of success (hope and pride) or failure (anxiety and shame); (b) epistemic emotions, which arise as a result of the cognitive qualities of the task information and the processing of such information; (c) subject emotions, triggered by the contents of the learning material; and (e) social emotions, derived from the interactive nature of most academic environments (Pekrun, 2016).

The impact of academic emotions on students’ performance and wellbeing is undeniable. According to the results of research conducted by Pelch (2018), students reporting high levels of anxiety coincided with statements of lack of confidence, academic excuses, and fear; furthermore, poor performance would be linked to a spectrum of negative academic emotions, including negative self-image, lack of confidence, and defeat mentality. Pelch establishes that students’ challenge mentality was associated more with good study habits than with and, as well as with students’ security, associated with confidence. The influence of academic emotions on the teaching-learning process is so significant that it can affect students’ attitudes toward learning, motivation, involvement with academic tasks, and general wellbeing (Barrios Tao and Gutiérrez De Piñeres Botero, 2020).

A study by Lei and Cui (2016) suggests that academic emotions can directly impact learning-related decision-making and the strategies students adopt to cope with academic situations. For example, those students who experience negative high-arousal emotions, such as anxiety, tend to avoid learning situations that they perceive as threatening. In contrast, those who experience positive, high-arousal emotions, such as pride, may be more willing to take on academic challenges.

Regarding adaptation to university life, another study indicated that students at their university entrance experience both positive and negative emotions during the beginning of their university careers. Although positive emotions usually predominate, negative emotions may increase during the university experience (Cobo-Rendón et al., 2020). Today’s college students possess characteristics due to their experience living during the pandemic. They are young people who often completed their high school education or began their college education through emergency remote education. Traditionally, first-year students struggle with the academic, learning, emotional, cognitive, and social demands of beginning a college career (Lobos et al., 2022).

A successful transition of students to college life is an essential element to consider when discussing educational quality, as this transition is associated with academic success, retention, social development, and personal growth that can shape students’ future success and wellbeing (Chan and Rose, 2023).

The importance of this research arises in theoretical and applied terms, especially in how the investigation of psychosocial variables such as emotions could intervene in processes related to the quality of education (Dimililer, 2018). This study attempts to know the importance of academic emotions in the university students. The teachers and researchers to need promote this variables, as well as to encourage universities to consider this during the early experiences of young people in their profesional training.

Taking into account the changes experienced by students due to the pandemic and considering that entering university life is a stage in the life of young people that is characterized by a process of personal, social, academic, and behavioral transformation, it is necessary to know how psychological factors such as academic emotions predict adaptation and intention to drop out of university in young people, for this reason, the present study proposes to evaluate the predictive capacity of academic emotions on university adaptation and intention to drop out. To respond to this objective, the following hypotheses have been proposed:

H1. There are differences in academic emotions reported by students according to the emergency remote education experiences generated by COVID-19.

H2. There are differences in the academic emotions present in the different academic activities according to the sex of the participating students.

H3. Both positive (enjoyment, hope, pride, and relief) and negative (anger, anxiety, embarrassment, shame, hopelessness, and boredom) emotions predominate during the performance of academic activities by university students.

H4. Academic emotions can predict adaptation to university life and intention to drop out, according to the type of activity performed.

A predictive associative methodology was selected. This type of research design analyzes the relationship between variables and examines the possibility of differences between two or more groups of individuals, taking advantage of differential situations created by nature or society (Ato et al., 2013), to evaluate how academic emotions reported by students during classes, studying, and exams predicted adaptation and intention to drop out of the university career. Likewise, this study corresponds to cross-sectional research since the information was obtained in a single time frame (Hernández Sampieri and Pilar, 2014).

Two hundred and ninety-five undergraduate psychology students (71 = men, 219 = women, 5 preferred not to say) from a Chilean university participated in the study. The mean age was 21.35 years (SD = 2.93). Table 1 shows the distribution of the participants according to the year of entry into university life. A total of 71.89% indicated that this was their first experience in higher education. An accidental non-probabilistic sampling was used based on the availability of the students present in the classrooms at the time of the application of the questionnaires.

The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire Short Version (AEQ-S). It is a measurement instrument designed to assess a wide range of emotions students experience in educational contexts, such as joy, boredom, anxiety, confidence, and frustration. These emotions are relevant to understanding how students react emotionally to academic challenges, success, and failure in educational settings. This more practical and easier-to-administer abbreviated version contains vital questions that capture the most representative or significant emotions in the academic context. The AEQ-S is helpful for ease of implementation in research studies and educational contexts, as it reduces the time required for participants to respond to the questions. In addition, the AEQ-S provides comparable results with the original version of the questionnaire, making it a valuable tool for studies that require a quick and efficient assessment of academic emotions (Bieleke et al., 2021).

The AEQ-S comprises 24 scales assessing the nine trait emotions of achievement-related enjoyment, hope, pride, relief, anger, anxiety, shame, hopelessness, and boredom. The items cover emotional experiences before, during, or after the corresponding environment and measure each emotion’s affective, cognitive, motivational, and physiological components. It consists of 96 items that measure emotions in three contexts: in classes (example: “During my classes, I enjoy being in it”), during learning or studying (example: “During my study hours, I feel confident when I study”), and in evaluations (example: “During exams, I get angry”). It presents a Likert-type response scale with five options (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = agree strongly). We averaged the items to obtain composite scores for each dimension of the questionnaire. The AEQ-S includes items to cover the four components of each emotion considered in the AEQ (i.e., affective, cognitive, motivational and physiological), the fit of the 9-factor model representing correlated emotions within learning environments was corroborated χ2(133) = 340.82, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.92, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.063. The reliability of the AEQ-S was identified as ranging from α = 0.75 to α = 0.93 (Bieleke et al., 2021).

For the assessment of adaptation to college life, four items were selected from the Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire Short Version (López-Angulo et al., 2021b). These items refer to the student’s academic adaptation to college life. The items are I1, “I am satisfied with the number and variety of subjects I have;” I2, “I am satisfied with the quality of the subjects I have;” I3, “I am satisfied with the subjects of this semester,” and I4 “I am delighted with the professors I have this semester.” The responses were obtained using a 7-alternative scale (1 = totally disagree to agree 7 = totally). We averaged the items to obtain composite scores for the variable. The reliability obtained in this study was α = 0.89.

Participants were presented with three items related to their thoughts or intentions to continue or not to continue their university studies (López-Angulo et al., 2021a). The items aim to evaluate the intention to drop out and focus on the desire to abandon the semester, the career, and the institution (I1: “I am thinking of not continuing to study this semester,” I2: “I am thinking of changing to another career,” and I3: “I am thinking of dropping out of college for good”). The questions were answered utilizing a 7-alternative response scale (1 = totally disagree to agree 7 = totally). We averaged the items to obtain composite scores for the variable. The reliability obtained in this study was α = 0.86.

This research is part of a broader project entitled “Academic Emotions, wellbeing, and Autonomy Support as Predictors of Adaptation and Intention to Drop out of University Life,” which was evaluated by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad del Desarrollo, Chile. For its development, contact was made with the psychology faculty authorities to explain the study’s characteristics and to obtain their authorization for the application of the questionnaires in their courses to guarantee the highest response rate. Some of the researchers went to the classrooms to explain to the students the characteristics of the study and to propose their participation. Subsequently, students were invited to answer the questionnaires using QR codes after reading and signing the informed consent form. The response time was an average of 15 min; the students did not receive any incentive for participation. The Ethics Committee of the Universidad del Desarrollo evaluated and approved this research on October 4, 2022.

The information obtained was stored in a Google form with the data. Initially, the reliability of the responses was analyzed using the internal consistency index of the dimensions and the total of the measurement instruments using Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonald’s Omega. Descriptive and central tendency analyses were performed for academic emotions and their dimensions, adaptation to university, and intention to drop out. Inferential analyses (Student’s t-tests and ANOVA) were performed to evaluate the differences in the scores of the variables of interest according to gender and academic year. Linear regressions were performed to corroborate the statistical prediction of academic emotions on adaptation to university life and on the intention to drop out. For this purpose, compliance with the statistical assumptions according to each procedure was previously evaluated. JASP 0.16 and Power BI software were used for data analysis.

In response to the general objective of evaluating the predictive capacity of academic emotions on university adaptation and intention to drop out, the results obtained according to the responses of the 295 participants of the study are presented. Initially, descriptive, and inferential analyses are presented that seek to respond to the hypotheses posed at the beginning of this research.

Table 2 presents the descriptive and reliability statistics for each of the dimensions of emotions and the variable’s adaptation to university life and intention to drop out. In this case, according to the averages of the scores, we find that during the classes, the students report a predominance of emotions such as Pride, Enjoyment, and Hope; in this case, these types of emotions are considered positive emotions oriented to success.

Regarding the predominant emotions during learning, enjoyment, optimism, and pride were identified, constituting positive emotions of high activation. Regarding the emotions during the evaluations, Relief was identified as predominant, followed by anxiety and pride. In this case, it was possible to identify positive emotions of low arousal, such as Relief, and negative emotions of high arousal, such as anxiety. Finally, high adaptation to university life and low intention to drop out were identified on the part of the participating students (see Table 2). On the reliability analysis of the analyzed dimensions, adequate levels of reliability were identified, presenting a range of scores from α = 0.86 to α = 0.93 and ω = 0.86 to ω = 0.93.

To answer, H1 referred to check if there are differences in academic emotions reported by students according to the emergency remote education experiences generated by COVID-19. ANOVA test was performed to evaluate the presence of statistically significant differences between group scores for each emotion studied according to class activities during the study. During the evaluations, the statistically significant results are presented in each case.

When evaluating academic emotions during classes, statistically significant differences were found in the emotion of embarrassment [F(3,291) = 3.335; p = 0.020; η2.033]. In this case, the students who entered in 2020 presented less presence of this emotion during classes than those who entered in previous years.

In the case of the emotions experienced during the study, statistically significant differences were found in the student’s anxiety levels according to the year of entry [F(3,291) = 3.559; p = 0.015]; η2.035. Higher anxiety levels were identified in the students who entered in recent years (2022 and 2021), ending the period of pandemic, social restrictions, and emergency remote education. Concerning the emotions experienced while taking the exams, no statistically significant differences were identified in the groups. Table 3 presents the averages of the emotion scores where such differences were identified.

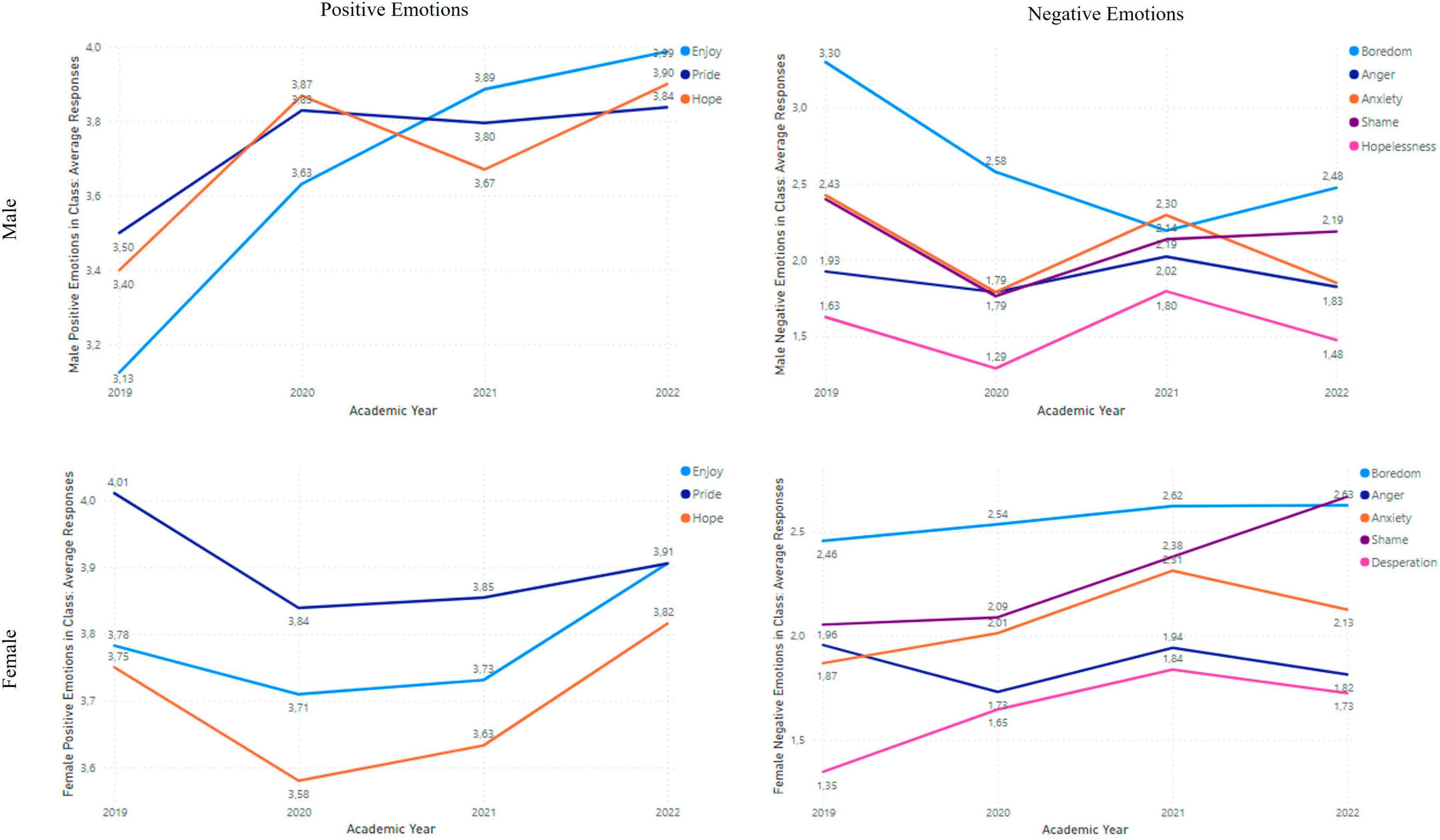

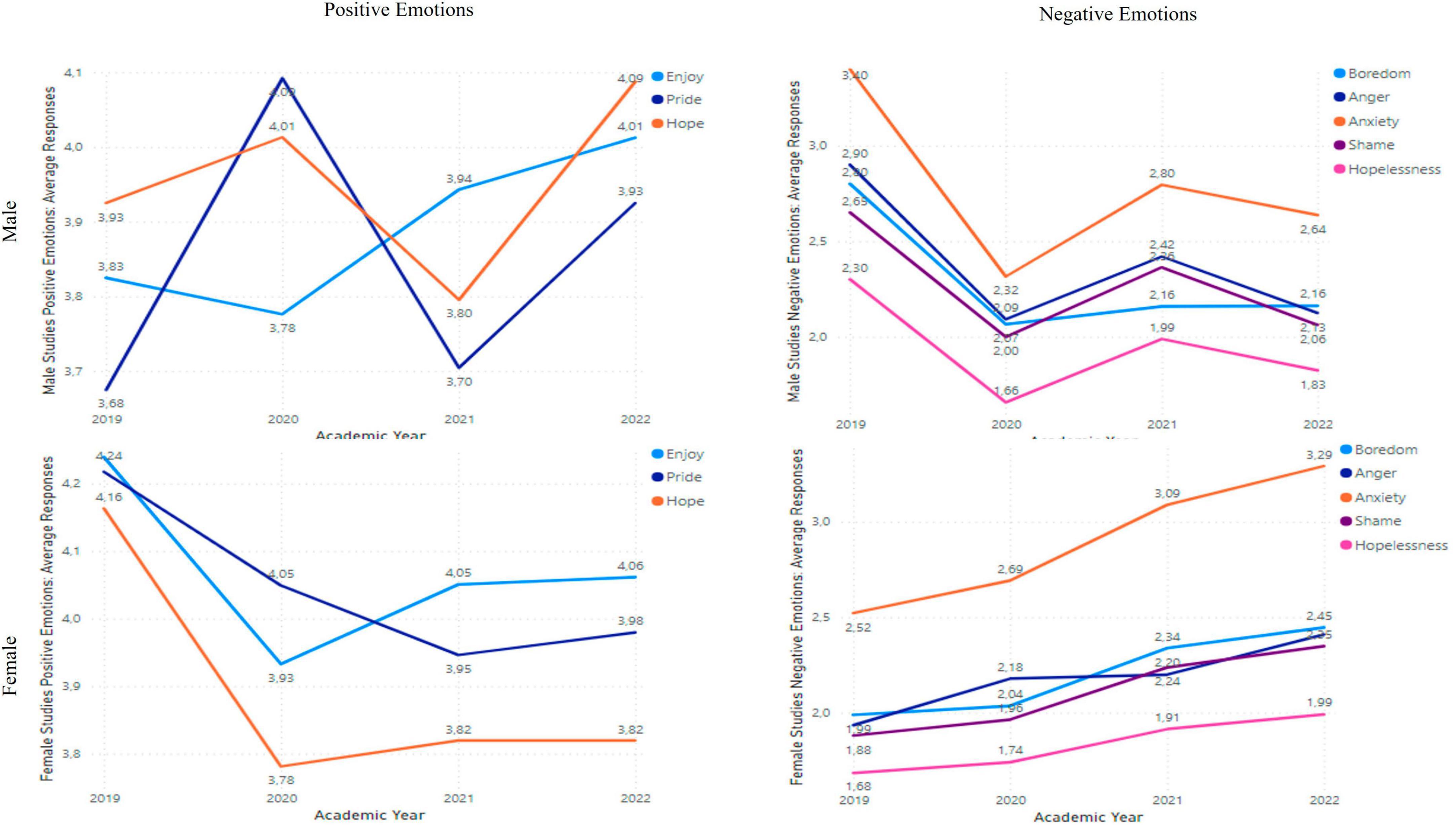

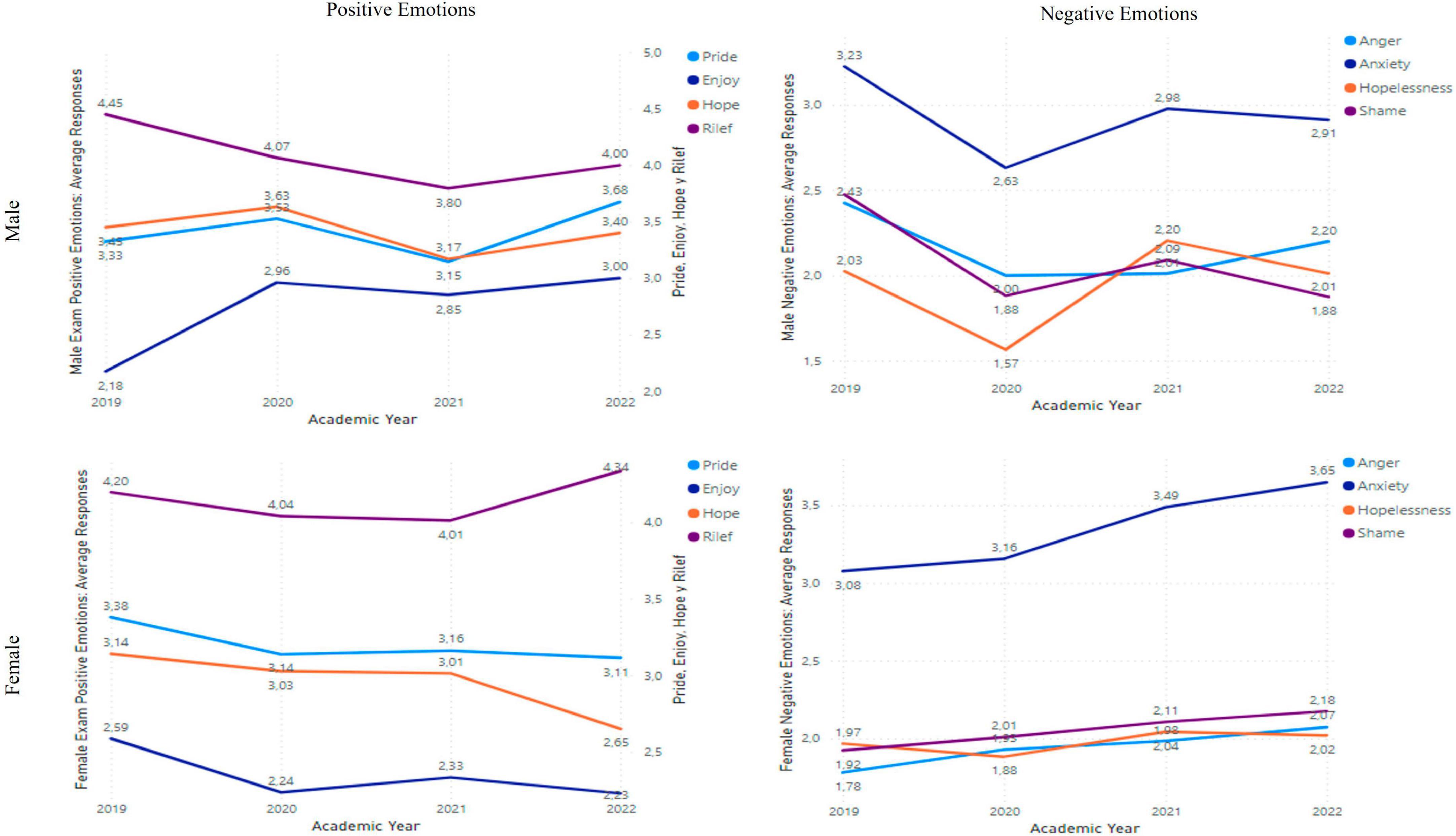

To answer H2, referring to the differences in the academic emotions of the students concerning sex, we found that in the case of emotions during classes and study, it was not possible to identify statistically significant differences (see Figures 1, 2). In the case of emotions during evaluations or exams, differences were identified in the emotions of enjoyment [t(288) = 3.459; p = < 0.001; r = 0.199]. In this case, males presented higher scores (M = 2.827; SD = 1.178) than females (M = 2.306; SD = 1.079). Statistically significant differences were also identified for the emotion of hope [t(288) = 3.036; p = 0.003; r = 0.176]; men presented higher scores (M = 3.398; SD = 1.112) than women (M = 2.929; SD = 1.136). Finally, statistically significant differences were identified in the reported levels of anxiety during the performance of the evaluations or exams [t(288) = 3.089; P = 0.002; r = 0.179], unlike the previous cases, men presented lower scores of this emotion (M = 2.901; SD = 1.127) than women (M = 3.404; SD = 1.212) (see Figure 3).

Figure 1. Descriptions of academic emotions in classes according to gender and year of entry of the students.

Figure 2. Descriptions of academic emotions in the study according to sex and year of entry of the students.

Figure 3. Descriptions of academic emotions in the test-related according to gender and year of entry of the students.

To answer H3, referring to the predominance of positive as well as negative emotions during the performance of academic activities by university students, the emotions were organized into two large groups. For this purpose, the average of emotions was obtained as follows: for the positive emotions, the scores of enjoyments, hope, pride, and Relief were included, and for the negative emotions, the scores of angers, anxiety, shame, hopelessness, and boredom were used.

A more significant predominance of positive emotions was identified in all cases; positive emotions were highlighted during study times over lectures and evaluations. In the case of negative emotions, they are presented to a lesser extent, being their highest score in the case of academic evaluations (see Table 4).

Additionally, the scores of positive and negative emotions experienced by the students were analyzed according to academic year and gender. For sex, only statistically significant differences were identified concerning the presence of positive emotions while taking the exams [t(288) = 2.606; p = 0.010; r = 0.151], with higher scores in males (M = 3.416; SD = 0.832) than females (M = 3.132; SD = 0.786). No statistically significant differences were identified for different academic years.

Now, to respond to hypothesis H4, which referred to the prediction of academic emotions with adaptation to university life and intention to drop out, according to the type of activity performed, linear regression analyses were performed for positive and negative emotions in each of the academic activities analyzed. The results indicate that positive emotions predict adaptation to university life during classes [F(1,294) = 97.128; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.249], during study hours [F(1,294) = 48.616; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.141], and during the performance of evaluations [F(1,294) = 31.329; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.097]. In the case of negative emotions, we also found that they can inversely predict adaptation to university life during classes [F(1,294) = 48.654; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.142], during study [F(1,294) = 31.986; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.098], and during exams [F(1,294) = 23.261; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.074], the coefficients are described in Table 5. A medium effect size is presented only in the positive emotions during classes; the identified effect size is small in the rest of the variables.

In the case of the intention to drop out, the same process was carried out linear regressions were analyzed for positive and negative academic emotions according to the academic activities reported; in the results, it was possible to identify that positive academic emotions during class [F(1,294) = 26.523; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.083], during the study [F(1,294) = 27.141; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.085], and during the exams [F(1,294) = 18.282; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.059] inversely predict the intention to drop out of university life. Similarly, the results indicate that negative emotions during classes [F(1,294) = 27.468; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.086], during study [F(1,294) = 15.639; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.051], and during taking exams [F(1,294) = 11.873; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.039] predict intention to drop out of university life. Table 6 presents the coefficients for each case; small effect sizes were identified in all the variables studied.

The main objective of this research was to evaluate the predictive capacity of academic emotions on college adjustment and intention to drop out. Before moving forward with the results that allowed us to respond to the intention of the study, we explored the reliability of the scores obtained in the instruments, finding that the measures of internal consistency of the scales used were adequate to interpret the results, being also congruent with previous studies that have analyzed these scales, (Bieleke et al., 2021; López-Angulo et al., 2021a,b).

The results indicate that the emotions reported by students during class are pride, enjoyment, and hope. Students feel proud of themselves in class; they feel proud of what they learn about their subject area, which motivates them to continue attending. Also, when attending classes, students typically enjoy being in the class; they are excited about learning in the class, motivated by the class, and love participating. They feel the excitement of hope in the confidence and optimism that comes from learning new material in class.

Moving forward with the emotions during learning or referring to the moment of studying, the trend described when they are in class is repeated, i.e., they report enjoying the challenge of learning the new course material, as well as feeling happy when they are aware that they are advancing in their learning sessions, they also report hope and optimism by developing confidence due to the progress they are making, and of course they feel proud of their progress and achievements which generates motivation to continue learning, it is essential to mention that all the emotions described are considered positive emotions of high activation.

The students reported two types of emotions during the evaluations, on the one hand, emotions of relief and pride, which can be interpreted as the pride they feel when they perceive that they have performed well on the test, feel that the effort they have made during the study has been worthwhile, and feel that they have grown in their mastery of the evaluated content. In contrast, relief is associated with the post-test experience. This is consistent because anxiety was reported as one of the most experienced emotions at the time of the evaluation, feeling nervous, worrying about not being able to finish on time due to the difficulty, and even wishing not to take the exam; anxiety is considered an academic emotion of high arousal (Bieleke et al., 2021).

Regarding H1, referred to check if there are differences in academic emotions reported by students according to the emergency remote education experiences generated by COVID-19, the results showed that students who entered the university in 2020 reported less embarrassment than those of other years. It can be interpreted that students who entered that year are currently more advanced in their university career; this has exposed them to multiple academic situations linked to academic achievement or failure, the latter linked to negative emotions such as anxiety, shame, or fear of failure that students have probably learned to manage during their university career and also because of their age (Respondek et al., 2017; Ekornes, 2022) in addition they entered in full COVID-19 contingency to college which according to studies was a period in which academic embarrassment was reported (Vo et al., 2021; Ghaderi et al., 2022). Similarly, statistically significant differences were found in anxiety levels, which were higher for first-year students and decreased as they progressed; note that the lowest anxiety levels were reported by upperclassmen (Respondek et al., 2017).

Regarding H2, referring to differences in students’ academic emotions concerning sex, we found that in the case of emotions during classes and study, no statistically significant differences were identified. However, we found statistically significant emotional differences during evaluations or tests. In that case, the findings can be summarized as follows: emotional valence in males during tests tends to be of more pleasant valence than for females, e.g., greater enjoyment and hope, while for females, the valence of emotions tends to be more displeasing, e.g., anxiety, being consistent with the findings of Ekornes (2022). These results are in the general line of affirming that gender could have implications in psychoeducational variables such as academic emotions (Pekrun and Stephens, 2012) and achievement (Lei and Cui, 2016), as well as in the retention of students in some regions of knowledge such as STEM in which women show greater probability of engaging in a self-deprecating cycle driven by negative academic emotions (Pelch, 2018).

To answer H3, referring to the predominance of positive and negative emotions during the performance of academic activities by university students, a more significant predominance of positive emotions was identified in all moments: during class, during study, and tests, positive emotions are highlighted during the moments of study on classes and evaluations, while negative emotions are presented to a lesser extent, being their highest score in the case of academic evaluations, evidence in line with the theory of the control-value theory of achievement emotions (Pekrun et al., 2007; Pekrun and Stephens, 2012), having implications in how the emotional experience is varied, subjective, activation and not only emphasizing the anxiety that the academic and evaluation context can cause in students.

Similarly, when analyzing the average of positive and negative emotions in the sample, the finding of statistically significant reporting of positive emotions by males during the tests than females is repeated. As exposed by Lei and Cui (2016), there is some vulnerability in female students in reporting a lower frequency of positive academic emotions compared to male students, and even the literature has shown that women tend to present more negative affectivity in everyday life and academic situations (Prowse et al., 2021; Bermejo-Franco et al., 2022; Díaz-Mosquera et al., 2022; Kaleta and Mróz, 2022), this possible vulnerability should be addressed in university spaces through counseling and advice spaces that perform psychoeducational interventions that provide tools to women at the level of emotional regulation, coping and even emotional intelligence (Goetz and Bieg, 2016).

The results indicated that the sample presented adequate adaptation to university life and low intention to drop out on the part of the participating students. Positive emotions during classes, learning, and tests predict students’ adaptation to college, while they inversely predict the intention to drop out. This finding is also congruent in the opposite direction, as negative emotions predict dropout intention and inversely predict college adjustment. Furthermore, it is consistent with a study at a German university that found negative emotions to predict college dropout, specifically anxiety (Respondek et al., 2017).

Our findings are also consistent with research conducted at a university in Norway, in which it was explained that academic emotions contribute significantly to the variance of explanation of the intention to drop out of university studies, with emphasis on emotions related to learning (Ekornes, 2022). Similarly, it adds to the evidence reported by Ganotice et al. (2016) about the emotional profiles that explain adequate or maladaptive outcomes in university education; specifically, those students who experience higher positive and lower negative academic emotions are those with better adaptive educational outcomes and then those students with moderate levels of shame and high positive emotions, while the worst maladaptive university profile is those students with high negative and few positive academic emotions; in our research positive emotions during classes have greater weight and even more significant effect size in explaining university adaptation, previously Yu et al. (2020) explained that academic emotions are directly implicated in college academic persistence, and Wang et al. (2022) explained that one of the internal mechanisms that mediate students’ interactions with professors, content, and other peers are academic emotions.

Therefore, evidence suggests that positive academic emotions may be more suitable than those considered in promoting better college outcomes and learning performance in students, as well as the importance of both positive and negative academic emotions in the activation spectrum of either high or low activation in the college student experience such as pride, enjoyment, hope, relief, anxiety and others in college retention (Lei and Cui, 2016; Tan et al., 2021); previous evidence suggests that academic emotions have long-term implications on psychological wellbeing, self-regulated learning, and harmonious passion displayed in studies, (Sverdlik et al., 2022).

The results have some practical theoretical implications, among them: (a) the importance of positive emotions as mechanisms that regulate cognitions and other resources as explored in the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2002); (b) the theory of emotions that groups them according to object focus: achievement emotions, epistemic emotions, topic emotions (Pekrun, 2016; Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2022); (c) the balance between boredom and anxiety explained by Flow theory to motivate behaviors from a perception of challenge and overcoming (Csikszentmihalyi, 2013); (d) sources of self-efficacy precisely: the one referred to previous achievements and emotional and physiological responses (1997); (e) self-regulated learning as it is understood that some emotions such as those referred to achievement would enable conditions to commit to one’s own learning (Pekrun and Perry, 2014; Asikainen et al., 2018; Martínez-López et al., 2021a); and (f) the possible relationship of academic emotions with self-determination theory specifically the need for competence (Ryan and Deci, 2022).

The practical implications of this research can be enlisted in two directions. On the one hand, academic guidance, and counseling services to carry out psychological interventions aimed at students that allow them to adapt adequately to university life, possibly with interventions to promote personal resources such as emotional regulation, coping, psychological flexibility, emotional intelligence, and other emotional competencies that can be activated for the benefit of students, it is crucial that these spaces for growth have a gender vision.

On the other hand, there are implications for teachers when planning and executing their classes, among them planning safe and positive learning environments, providing support for student autonomy, providing contextualized examples, generating a warm classroom environment to answer students’ comments and doubts, reinforcing their curiosity, giving effective feedback based on content mastery, and making use of verbal persuasion as a source of self-efficacy. Teachers should also guide how to study the contents when students must perform their individual or group learning sessions. Teachers should also be transparent, predictable, and concrete about the test’s learning outcomes (Pekrun and Stephens, 2012; Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2022). Similarly, another implication could be strengthening self-regulated learning strategies from the sources of academic self-efficacy (Bzuneck, 2018).

As a final reflection, it is essential to mention that in this study, positive academic emotions prevail over negative ones. However, it is essential to remember that although the latter are unpleasant, they also have adaptive functions within the psychological, motivational, and behavioral components in the academic context (Pekrun and Stephens, 2012). This research is intended to study how emotions affect university permanence. However, it is not intended to establish a utopian or simplistic look at the situation of positive emotions vs. negative emotions in the university experience.

The study’s main strength is to contribute to a field of knowledge about how academic emotions are related to educational outcomes, in this case, university adaptation and intention to drop out (Camacho-Morles et al., 2021). However, this study has some limitations that can be considered in future research. Among them are non-probabilistic sampling, not including students from several careers and different locations or type of institutions (public and private), inclusion of objective indicators of the university experience such as academic performance, and not only having self-report evaluations, but future research should also explore the academic emotions generated in specific areas of knowledge such as mathematics and statistics. Longitudinal studies could also investigate how the relationships between the analyzed constructs change across semesters. In promoting adaptation to higher education, psychological practices may include fostering students’ development of emotional skills and resilience.

The academic emotions that characterize the college experience are varied. They can be classified into three moments: during class, pride, enjoyment, and hope are experienced; during learning or study, those above were reported; and during evaluations or tests, relief, anxiety, and pride are experienced. Therefore, positive emotions are predominant over negative ones. The report of academic emotions varies according to the year of entry to the university; For example, less embarrassment and anxiety are reported in senior students. It was also found that there are differences in the academic emotions present in the different academic activities according to the gender of the students, with male students reporting higher positive emotions. Finally, it is concluded that academic emotions have implications for college adjustment and intention to drop out; precisely, positive emotions during classes, learning, and testing predict students’ college adjustment while inversely predicting intention to drop out. This finding is also congruent in the opposite direction, with negative emotions predicting dropout intention and inversely predicting college adjustment.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Comité de Ética, Universidad del Desarrollo. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

RC-R: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. VH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. DG-Á: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. RC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research is part of the “Academic Emotions, well-being, and Autonomy Support as Predictors of Adaptation and Intention to drop out of university life” project, funded by the Centro de Innovación Docente (CID), Universidad del Desarrollo, Chile.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aristovnik, A., Karampelas, K., Umek, L., and Ravšelj, D. (2023). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on online learning in higher education: a bibliometric analysis. Front. Educ. 8:1225834. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1225834

Asikainen, H., Hailikari, T., and Mattsson, M. (2018). The interplay between academic emotions, psychological flexibility and self-regulation as predictors of academic achievement. J. Furth. High. Educ. 42, 439–453. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2017.1281889

Ato, M., López, J., and Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. An. Psicol. 29, 1038–1059. doi: 10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511

Barrios Tao, H., and Gutiérrez De Piñeres Botero, C. (2020). Neurociencias, emociones y educación superior: una revisión descriptiva. Estud. Pedag. (Valdivia) 46, 363–382. doi: 10.4067/s0718-07052020000100363

Bermejo-Franco, A., Sánchez-Sánchez, J. L., Gaviña-Barroso, M. I., Atienza-Carbonell, B., Balanzá-Martínez, V., and Clemente-Suárez, V. J. (2022). Gender differences in psychological stress factors of physical therapy degree students in the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environm. Res. Public Health 19:810. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020810

Bieleke, M., Gogol, K., Goetz, T., Daniels, L., and Pekrun, R. (2021). The AEQ-S: a short version of the achievement emotions questionnaire. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 65:101940. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101940

Bzuneck, J. A. (2018). Emoções acadêmicas, autorregulação e seu impacto sobre motivação e aprendizagem. ETD Educ. Tematica Digital 20, 1059–1075. doi: 10.20396/etd.v20i4.8650251

Camacho-Morles, J., Slemp, G. R., Pekrun, R., Loderer, K., Hou, H., and Oades, L. G. (2021). Activity achievement emotions and academic performance: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33, 1051–1095. doi: 10.1007/s10648-020-09585-3

Casanova, J. R., Gomes, A., Moreira, M. A., and Almeida, L. S. (2022). Promoting success and persistence in pandemic times: an experience with first-year students. Front. Psychol. 13:815584. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.815584

Chan, K., and Rose, J. (2023). “Conceptualizing success: a holistic view of a successful first-year undergraduate experience,” in Perspectives on enhancing student transition into higher education and beyond, eds D. Willison and E. Henderson (Pennsylvania: IGI Global), 47–68.

Cobo-Rendón, R., Pérez-Villalobos, M. V., Páez-Rovira, D., and Gracia-Leiva, M. (2020). A longitudinal study: affective wellbeing, psychological wellbeing, self-efficacy and academic performance among first-year undergraduate students. Scand. J. Psychol. 61, 518–526. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12618

Crede, M., and Niehorster, S. (2012). Adjustment to college as measured by the student adaptation to college questionnaire: a quantitative review of its structure and relationships with correlates and consequences. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 24, 133–165. doi: 10.1007/s10648-011-9184-5

Díaz-Mosquera, E., Corral Proaño, V., and Merlyn Sacoto, M. (2022). Sintomatología depresiva durante la pandemia COVID-19 en estudiantes universitarios de Quito, Ecuador. Veritas Res. 4, 147–159.

Díaz-mujica, A., García, D., López, Y., Maluenda-Albornoz, J., Hernández, H., and Pérez-Villalobos, M. (2018). “Factores asociados al abandono. Tipos y perfiles de abandono,” in Octava conferencia latinoamericana sobre el abandono en la educación superior, Panamá.

Dimililer, K. (2018). Use of Intelligent Student Mood Classification System (ISMCS) to achieve high quality in education. Qual. Quant. 52, 651–662. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0644-y

Ekornes, S. (2022). The impact of perceived psychosocial environment and academic emotions on higher education students’ intentions to drop out. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 41, 1044–1059. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2021.1882404

Fredrickson, B. (2002). “Positive emotions,” in Handbook of positive psychology, eds C. R. Snyder and S. J. Lopez (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 120–134.

Galve-González, C., Blanco, E., Vázquez-Merino, D., Herrero, F. J., and Bernardo, A. B. (2022). Influencia de la satisfacción, expectativas y percepción del rendimiento en el abandono universitario durante la pandemia. Rev. Estud. Invest. Psicol. Educ. 9, 226–244. doi: 10.17979/reipe.2022.9.2.9153

Ganotice, F. A. Jr., Datu, J. A. D., and King, R. B. (2016). Which emotional profiles exhibit the best learning outcomes? A person-centered analysis of students’ academic emotions. Sch. Psychol. Int. 37, 498–518. doi: 10.1177/0143034316660147

García-Álvarez, D., Liccioni, E., and Cobo-Rendón, R. (2019). Conociendo las emociones y sus implicaciones en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje en la educación primaria. Rev. Convocación 40, 50–63.

Ghaderi, E., Khoshnood, A., and Fekri, N. (2022). Achievement emotions of university students in on-campus and online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tuning J. High. Educ. 10, 319–336. doi: 10.18543/tjhe.2346

Goetz, T., and Bieg, M. (2016). “Academic emotions and their regulation via emotional intelligence,” in Psychosocial skills and school systems in the 21st century: theory, research, and practice, eds A. Lipnevich, F. Preckel, and R. Roberts (Cham: Springer), 279–298.

Hako, A. N., Shikongo, P. T., and Mbongo, E. N. (2023). “Psychological adjustment challenges of first-year students: a conceptual review,” in Handbook of research on coping mechanisms for first-year students transitioning to higher education, ed. K. R. M. Peter Jo Aloka (Pennsylvania: IGI Global), 191–210.

Hernández Sampieri, R. F., and Pilar, C. B. (2014). Metodología de la investigación. New York, NY: Mc Graw Hill.

Jacobo-Galicia, G., Máynez-Guaderrama, A. I., and Cavazos-Arroyo, J. (2021). Miedo al Covid, agotamiento y cinismo: su efecto en la intención de abandono universitario. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 14, 1–18. doi: 10.32457/ejep.v14i1.1432

Kaleta, K., and Mróz, J. (2022). Gender differences in forgiveness and its affective correlates. J. Relig. Health 61, 2819–2837. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01369-5

Lei, H., and Cui, Y. (2016). Effects of academic emotions on achievement among mainland Chinese students: a meta-analysis. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 44, 1541–1553. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2016.44.9.1541

Lobos, K., Cobo-Rendón, R., Mella-Norambuena, J., Maldonado-Trapp, A., Fernández Branada, C., and Bruna Jofré, C. (2022). Expectations and experiences with online education during the COVID-19 pandemic in university students. Front. Psychol. 12:815564. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.815564

López-Angulo, Y., Cobo-Rendón, R., Saéz-Delgado, F., and Mujica, A. D. (2021b). Exploratory factor analysis of the student adaptation to college questionnaire short version in a sample of chilean university students. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 9, 813–818. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2021.090414

López-Angulo, Y., Cobo-Rendón, R. C., Pérez-Villalobos, M. V., and Díaz-Mujica, A. E. (2021a). Apoyo social, autonomía, compromiso académico e intención de abandono en estudiantes universitarios de primer año. Formación Univ. 14, 139–148. doi: 10.4067/S0718-50062021000300139

López-Angulo, Y., Sáez-Delgado, F., Mella-Norambuena, J., Bernardo, A. B., and Díaz-Mujica, A. (2023). Predictive model of the dropout intention of Chilean university students. Front. Psychol. 13:893894. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.893894

Martínez-López, Z., Villar, E., Castro, M., and Tinajero, C. (2021b). Self-regulation of academic emotions: recent research and prospective view. An. Psicol. 37, 529–540.

Martínez-López, Z., Villar, E., Castro, M., and Tinajero, C. (2021a). Autorregulación de las emociones académicas: investigaciones recientes y prospectiva. An. Psicol. 37, 529–540. doi: 10.6018/analesps.415651

Pekrun, R., and Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2022). “Academic emotions and student engagement,” in Handbook of research on student engagement, eds A. L. Reschly and S. L. Christenson (Berlin: Springer International Publishing), 109–132. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-07853-8_6

Pekrun, R., and Perry, R. P. (2014). “Control-value theory of achievement emotions,” in International handbook of emotions in education, eds R. Pekrun and L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (New York, NY: Routledge), 120–141.

Pekrun, R., and Stephens, E. J. (2012). “Academic emotions,” in Individual differences and cultural and contextual factors. APA educational psychology handbook, Vol. 2, eds K. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, S. Graham, J. Royer, and M. Zeidner (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association).

Pekrun, R., Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., and Perry, R. P. (2007). “The control-value theory of achievement emotions: an integrative approach to emotions in education,” in Emotion in education, eds P. A. Schutz and R. Pekrun (San Diego, CA: Academic), 13–36.

Pelch, M. (2018). Gendered differences in academic emotions and their implications for student success in STEM. Int. J. Stem Educ. 5, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s40594-018-0130-7

Pérez, A. B. D., Quispe, F. M. P., Aguilar, O. A. G., and Cortez, L. C. C. (2020). Transición secundaria-universidad y la adaptación a la vida universitaria. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 26, 244–258.

Prowse, R., Sherratt, F., Abizaid, A., Gabrys, R. L., Hellemans, K. G., Patterson, Z. R., et al. (2021). Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic: examining gender differences in stress and mental health among university students. Front. Psychiatry 12:650759. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.650759

Respondek, L., Seufert, T., Stupnisky, R., and Nett, U. E. (2017). Perceived academic control and academic emotions predict undergraduate university student success: examining effects on dropout intention and achievement. Front. Psychol. 8:243. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00243

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2022). “Self-determination theory,” in Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research, ed. F. Maggino (Cham: Springer), 1–7.

Shamionov, R. M., Grigoryeva, M. V., Grinina, E. S., Sozonnik, A. V., and Bolshakova, A. S. (2023). Subjective assessments of the pandemic situation and academic adaptation of university students. OBM Neurobiol. 7:18. doi: 10.21926/obm.neurobiol.2301150

SIES (2021). Informe de retención de 1er año pregrado cohortes 2016–2020. Ministerio de educación. Available online at: https://www.mifuturo.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Informe_Retencion_SIES_2021.pdf (accessed August 10, 2023).

Sverdlik, A., Rahimi, S., and Vallerand, R. J. (2022). Examining the role of passion in university students’ academic emotions, self-regulated learning and well-being. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 28, 426–448. doi: 10.1177/14779714211037359

Tan, J., Mao, J., Jiang, Y., and Gao, M. (2021). The influence of academic emotions on learning effects: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:9678. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189678

Van Rooij, E. C., Jansen, E. P., and van de Grift, W. J. (2018). First-year university students’ academic success: the importance of academic adjustment. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 33, 749–767. doi: 10.1007/s10212-017-0347-8

Vo, P., Lam, T., and Nguyen, A. (2021). Achievement emotions and barriers to online learning of university students during the COVID-19 time. Proc. AsiaCALL Int. Conf. 621, 109–120. doi: 10.2991/assehr.k.211224.012

Wang, Y., Cao, Y., Gong, S., Wang, Z., Li, N., and Ai, L. (2022). Interaction and learning engagement in online learning: the mediating roles of online learning self-efficacy and academic emotions. Learn. Individ. Differ. 94:102128. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2022.102128

Wu, P., Li, M., Zhu, F., and Zhong, W. (2022). Empirical investigation of the academic emotions of gaokao applicants during the COVID-19 pandemic. SAGE Open 12:215824402210798. doi: 10.1177/21582440221079886

Yu, J., Huang, C., Han, Z., He, T., and Li, M. (2020). Investigating the influence of interaction on learning persistence in online settings: moderation or mediation of academic emotions? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:2320. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072320

Keywords: academic emotions, adjustment to university life, university dropout, university students, higher education

Citation: Cobo-Rendón R, Hojman V, García-Álvarez D and Cobo Rendon R (2023) Academic emotions, college adjustment, and dropout intention in university students. Front. Educ. 8:1303765. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1303765

Received: 28 September 2023; Accepted: 20 November 2023;

Published: 20 December 2023.

Edited by:

Joana R. Casanova, University of Minho, PortugalReviewed by:

Abílio Afonso Lourenço, University of Minho, PortugalCopyright © 2023 Cobo-Rendón, Hojman, García-Álvarez and Cobo Rendon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rubia Cobo-Rendón, cmNvYm9AdWRkLmNs

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.