95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 28 November 2023

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1291357

This research employs a qualitative lens to explore the multifarious hurdles international students face in underrepresented educational destinations, taking Kyrgyzstan as an exemplar. Leveraging Bourdieu’s theoretical insights, the study unearths nuanced personal, social, and academic adversities. Central to the study’s findings are the prevailing power imbalances, positioning international students at a disadvantage due to varying habitus and insufficient cultural capital. Notwithstanding these issues, these students exhibit determination and agency. The research underscores the urgency for more inclusive practices, curbing discrimination, rebalancing power structures, and fortifying student support mechanisms, providing policy directions for enhanced international student experiences in analogous settings.

International student mobility (ISM) for education abroad involves students leaving their home country to pursue higher education in a destination abroad. This endeavor promises “better quality education, achieve academic success, develop career prospects, and enhance employability skills” (Nachatar Singh & Jack, 2021, p. 445). However, this pursuit is not devoid of challenges. While staying in the host country, international students experience a process of acculturation to the new social, cultural and academic environment of the host country (Zhou et al., 2008).

Given the substantial volume of ISM and its associated benefits for individuals and nations, these acculturation experiences of international students (IS) have garnered significant attention from researchers. However, “despite this growing attention, there are also recognized gaps in our knowledge” of IS experience (Gilmartin et al., 2021, p. 4724). A majority of the existing research in the field of IS experiences pertains to core (e.g., Canada, the US, Australia, the UK, France, Germany) and emerging (e.g., Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, UAE, Sweden, Norway) ISM destinations as these countries receive a higher volume of the ISM. The newer potential destinations at the peripheries have remained overlooked or underexplored. These destinations attract 19% of the total global ISM volume and represent a horizontal or regional shift in ISM trends (Chan, 2012; Teichler, 2017).

The disparity between the rising ISM flow to these peripheral destinations and the.

lack of knowledge regarding IS experiences in these contexts hampers a comprehensive understanding and theorization of IS experiences. This also reflects the inequalities in the global higher education research landscape, where marginal and peripheral contexts receive inadequate attention (Altbach, 2006, 2013; Gilmartin et al., 2021; Lipura, 2021; Tight, 2022). Addressing this gap, this research delves into the higher education sojourning experience of IS in a peripheral, marginal, and unconventional context. The IS sojourning experiences in such contexts warrant exploration due to their value in the broader field of ISM, shedding light on how various aspects of IoHE and ISM “work out in different parts of the world, [and by doing so] offer a window into policy and practice, and how this might be further developed in the future” (Tight, 2022, p. 253).

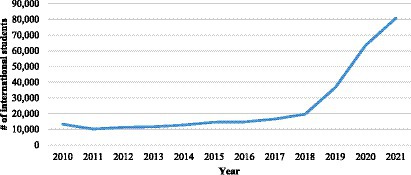

To fulfil this objective, this exploratory research delves into the sojourn experiences of a group of IS studying in Kyrgyzstan. Kyrgyzstan serves as an illustrative example of a peripheral hub of ISM, being the second-largest recipient of IS after Kazakhstan in the region (Figure 1). Employing a qualitative approach, the study gathered data through semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions and diary entries. These data were thematically analyzed and interpreted within the framework of Bourdieusian concepts of field, habitus, and capital. The central research question guiding the study is: How do IS experience personal, social, and academic life during their higher education sojourn in Kyrgyzstan?

Figure 1. Rise in the number of internationals students in Kyrgyzstan (Source: National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic).

The transition to higher education abroad for international students (IS) involves a shift from their home country’s academic, social, and cultural environment to that of the destination country (Jindal-Snape and Rienties, 2016). This shift results in various adaptation challenges for IS in personal, academic, and social spheres (Smith and Khawaja, 2011).

International students face feelings of homesickness, loneliness, depression, and isolation (Tseng and Newton, 2002). Homesickness, in particular, has been identified as a prevalent issue among various nationalities studying abroad (Ying, 2005; Vergara et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2016). This emotion can lead to anxiety, depression, and a sense of alienation (Brown and Holloway, 2008). Additionally, depression, often related to homesickness, has been reported at higher rates among IS (Zheng et al., 2015). Factors contributing include emotional instability, academic pressures, health issues, and challenges in integrating into the host society (Han et al., 2013; Popescu and Buzoianu, 2017).

The academic challenges emerge from the clash of Eastern learning culture, which is teacher-centered, and Western learning culture, which is student-centered (Ma and Wen, 2018). English language proficiency (ELP) is another significant academic adjustment challenge. A deficiency in ELP negatively affects students’ academic performance and their ability to effectively communicate, comprehend lectures, and complete assignments (Campbell and Li, 2008; Andrade, 2009).

The key challenges in the social realm include language barriers, discrimination, lack of friendships, and inadequate social support. Insufficient language skills lead to reduced interaction opportunities, limiting the formation of social connections and inducing feelings of anxiety (Park et al., 2017). Discrimination, a recurring challenge for IS, can result in feelings of worthlessness, stress, and other health issues (Poyrazli and Lopez, 2007). Establishing friendships is vital for IS, but many find it difficult to connect with local students. Instead, they tend to bond with fellow nationals, leading to ‘ghettoization’ and further isolation from the host community (Brown, 2009; Cao et al., 2018).

The literature underlines that international students face numerous challenges when adapting to their host countries. These challenges range from personal feelings of homesickness and depression to academic struggles with language and differing learning styles, and social challenges of discrimination and building new friendships. While there is extensive research on these adaptation experiences, there remain gaps, especially in less-researched destinations. The current study aims to bridge this gap by examining the experiences of international students in Kyrgyzstan – a peripheral education hub. By doing so, it seeks to enrich the discourse on international higher education and provide a deeper understanding of IS experiences in non-mainstream educational settings.

Most of the existing literature on international student experiences (ISE) examines the process of studying abroad from the perspective of the acculturation model. However, this model has faced criticism for portraying the adjustment and adaptation process as a “deficit” being’s struggle to fit into the host community social order by surrendering their “identities for re-acculturation” (Marginson, 2014, p. 9). In the context of ISM, this implies that individuals are leaving an inferior environment and culture behind to undergo re-acculturation into a supposedly superior social, cultural, and academic environment of the host country. Recognizing the limitations of this deficit view, Bourdieusian thinking tools (field, capital, habitus) provide a “conceptual framework that theoretically explores individual-context interrelationship” (Joy et al., 2018, p. 4). Human experiences arise at the intersection of individuals’ interaction and coaction with their surroundings, and this holds true for the lived experiences of IS. These experiences are intricately linked to and influenced by the position of IS within their context. Therefore, Bourdieu’s conceptual tools of field, capital and habitus offer a suitable framework for comprehending the nature of these experiences.

In Bourdieu theory, the concept of field represents the contextual backdrop. It can be envisioned as an “autonomous social microcosm” (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, p. 97) with its own governing dynamics (Bourdieu, 1993). Thomson (2008) likens a field to a sports arena, complete with its unique game, participants with positions, rules governing competition, and an ongoing struggle within. From this analogy, any realm of human social activity can be understood as a distinct social microcosm where individuals occupy specific horizontal and vertical positions and engage in a competitive struggle (Joy et al., 2018). This struggle within social spheres emerges as individuals strive to acquire various forms of capital, as possession of such capital grants them positional advantage within a specific field.

Naidoo (2004) clarifies the concept of capital as “the specific cultural or social [….] assets that are invested with value in the field which, when possessed, enables membership to the field” (p. 458). According to Bourdieu (1986), capital “makes the game of the society,” “produce(s) profit” and even can “reproduce itself in identical and extended form” (pp. 241–242). Capital manifests in three primary forms: economic, social, and symbolic. The value of capital is intimately tied to its relation within the field. The pursuit of capital within any field is guided by an individual’s habitus.

Habitus, in essence, represents stable and enduring dispositions. Soong et al. (2018) refers to habitus as “elements of consciousness” (p. 245) that influences “one’s present and future practices” and “generates perceptions [and] appreciations” (Naidoo, 2015, p. 343), thereby affording individuals a “practical sense for what is to be done in a [….] situation” (Bourdieu, 1998b, p. 25).

The pursuit of higher education mobility involves a struggle to acquire capital and gain social advantage. In this pursuit, IS leave the field of their home country and transition to a new field in their destination country. This new field has its own distinct context and set of rules. By examining the lived experiences of IS in Kyrgyzstan through Bourdieu’s framework, valuable insights can be obtained into various dimensions of this struggle within the specific context of a peripheral destination. These insights encompass understanding how students position themselves into this new field, navigate the new contextual dynamics, interpret, and make sense of this novel social environment, recognize which form of capital hold relevance in this context and comprehend these forms of capital are allocated and valued within the unique social and academic settings. Additionally, this approach can provide insights into how students’ and other actors’ habitus influence perceptions, behaviors, and attitudes within the field. Analyzing these dimensions sheds light on the challenges faced by IS in peripheral destinations and contributes to a deeper and broadening understanding of the intricate dynamics of ISM.

This exploratory study employed a qualitative multimethod research design. Qualitative research offers the advantage of studying phenomena within their “natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meaning that people bring to them” (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018, p. 43). Ravitch and Carl (2019) endorse this approach for its power in “understanding the way that people see, view, approach, and experience the world and make meaning of their experiences” (p. 40). This approach, being “multimethod in focus” allows the “use and collection of a variety of empirical material […] that describe routine and problematic moments and meanings in individuals’ lives” (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018, p. 43). This specific aspect of the approach facilitated the adoption of a multimethod qualitative research design for this study. A multimethod research design entails “the practice of employing two or more different methods […] within the same study or research […] rather than confining the research to the use of a single method” (Hunter & Brewer, 2015, p. 187). It is essential to differentiate multimethod from mixed method designs: the former involves using of multiple qualitative quantitative methods within the same epistemological perspective, whereas the latter integrates methods from different epistemological perspectives (Mik-Meyer, 2020). The clear advantage of a multimethod design lies in its potential to yield a comprehensive, multifaceted understanding of a complex phenomenon, generating multi-dimensional insights and bolstering the confidence in interpretations, inferences and conclusions (Chamberlain et al., 2011; Hesse-Biber et al., 2015). Since ISE is inherently intricate, involving multidimensional processes of adjustments and adaptations; consequently, a multimethod qualitative design was chosen to facilitate a comprehensive, nuanced, and context-sensitive understanding of the participants’ experiences during their international sojourn.

The investigation employed three distinct methods of data collection: semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, and journal writing.

Semi-structured interviews served as the primary data collection method. Cohen et al. (2018) consider them effective and “powerful implement for researchers” (p. 347) for allowing participants and researchers “to discuss their interpretations of world in which they live” (p. 349). These interviews consist of a set of pre-determined, standard, open-ended questions. This predetermined structure gives interviews focus, while the open-ended nature of the questions empowers participants to share their world view, and thereby fostering con-constructed understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. This aligns with the study’s purpose, which aimed to explore the phenomenon from participants’ perspective. The interview protocol consisted of two parts: one addressing background information (with questions such as “Where are you from?,” “How long have you been in Kyrgyzstan?”), and the other containing 19 questions delving into personal, social, and academic experiences of the participants. Some questions included in this part were: “Please describe your experience of studying in Kyrgyzstan so far.,” “What social life challenges you face here?,” “What kind of personal challenges have you faced after coming here?,” and “Have you faced any study-related difficulties in your university?”

Focus group discussions and journal writing were employed as complementary methods to enrich the investigation’s depth and intensity (Gall et al., 2003). Journals are “the most effective research tools to mine the rich personal experiences and emotions of participants’ inner lives” and make “introverts [….] feel particularly comfortable when voicing” their experiences “in private writing” (Smith-Sullivan, 2008, p. 214). Focus group discussions (FGD), on the other hand, are “less threatening to many research participants, and this environment is helpful for participants to discuss perceptions, ideas, opinions, and thoughts” (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009, p. 2). While journals afford privacy, FGD encourage interaction, potentially eliciting insights participants might not share in one-on-one interviews (Morgan, 2008). These methods, combined with semi-structured interviews, bolstered the collection of comprehensive and reliable information, facilitating a holistic grasp of participant’s sojourn experience.

Prior to data collection, participants were collectively briefed on the research purpose, their voluntary participation, confidentiality, anonymity, and other ethical considerations. They were informed about the data collection methods and schedule, and their informed consent was obtained. For journal entries, each participant was provided with a password-protected digital document following their interviews. These journal entries were directed by two questions: (a) What are your personal, social, and academic experiences in Kyrgyzstan? (b) What difficulties and challenges have you faced in the countries? Participants were encouraged to engage in reflective documentation, recording their experiences, feelings, and reflections in response to these prompts. The participants sustained the journal entries over a span of 3 months.

The FGD were structured to encourage open dialogue among the participants. The participants were distributed into four groups. Each discussion session lasted for approximately 90 min. The discussions were framed around the following open-ended sentence stems: (a) According to students living in Kyrgyzstan, studying in a university here is … …, (b) Students’ academic life in Kyrgyzstan is …, (c) Students’ experience of living and studying in Kyrgyzstan is …. The approach of using sentence stems is recognized as a projective technique, which effectively stimulates truthful responses from the participants. It serves to diminish the possibility of participants providing socially acceptable answers and, during analysis, facilitates a diverse range perspectives on specific issues when comparing responses among participants (Clow and James, 2014).

To fulfill the study objectives of investigating the sojourn experience of IS in a peripheral international education destination, data was collected from a group of 13 students, selected purposively through snowball sampling. Participants’ inclusion criteria were: (1) pursuing a higher education degree with a long-term stay in the country (2) enrollment in a university (3) a minimum of 2 years’ residency in the country at the time of the interviews. Table 1 presents participant detail, with pseudonyms used in place of actual names to ensure confidentiality.

The data analysis process followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis approach to systematically explore patterns with the collected data. It was an iterative process comprising multiple phases. The entire process was completed manually. The first phase involved meticulously familiarizing myself with the data through multiple listens of the interview and focus group discussions recordings (and reading in the case of journal entries). This phase also included transcribing interviews and focus group discussions. Subsequently, the coding process began. Initial codes were assigned to the data fragments through line-by-line coding, and preliminary themes were identified by grouping these codes. This clustering led to the emergence of three main themes which are presented in the findings section.

The data analysis revealed a predominantly challenging nature of the participants lived experience in Kyrgyzstan. They reported facing various difficulties in their daily existence and routines. These difficulties can be located into three broader spheres: personal, social, and academic. The following parts of the findings section comprehensively detail these problematic aspects of their experience.

Personal sphere refers to the students’ personal and private world, and the lived experiences in this sphere relate to psychological experiences of homesickness, loneliness, depression, frustration, alienation, isolation, loss of identity, and worthlessness (Tseng and Newton, 2002). The data revealed homesickness as the most salient experience in the case of this group of students. The feeling of homesickness had certain other psychological effects.

Homesickness was identified as the most common and significant personal problem among the participants. Homesickness is “a psychological reaction to the absence of significant others and familiar surroundings” (Poyrazli and Lopez, 2007) which triggers emotional and adjustment difficulties. Homesickness equally affected all participants, irrespective of the geographic, cultural, and linguistic proximity of their background to that of the host country.

I’m from Kazakhstan which is quite similar to this country. I mean we have almost the same traditions, same culture, and nearly same language. But I always missed my home. It was the first time I was separated from my parents and family, and I still miss them. It is draining. (Aigerim, Focus Group Comments)

The quote emphasizes the deep emotional impact of homesickness, underscoring the paramount importance of human connections, especially with family, over linguistic or cultural ties to one’s surroundings. While Aigerim’s host country, Kyrgyzstan, shares linguistic, cultural, and historical similarities with her homeland, Kazakhstan, her separation from family remains a profound source of distress, impacting her adaptation and integration. This underscores that human bonds often outweigh cultural or linguistic similarities in importance. This suggests that homesickness can be even more emotionally taxing for those who lack these cultural and linguistic connections with the host community.

Furthermore, homesickness, and the emotional toll that it exacts, also affected other aspects of the participants’ life. This included their academic performance and their ability to establish new friendship networks and benefit from these networks. The following quote highlights how it affected their academic performance.

I missed home. This put so much pressure on me. I was not able to focus on my studies. I felt burnt out during my first year and it was horrible, honestly. It was mentally very hard for me. (Momal, interview comment)

Momal’s experience illustrates the negative and exacerbating impact of homesickness on the academic adjustment of the students. The use of past tense and an allusion to ‘first year’ imply that the intensity and impact of homesickness is higher during the first year, but it mitigates in the subsequent years. The first year of the sojourn is usually also a transition year for students. They not only transition from one level of study to another level of study but also make psychological, emotional, cultural, and physical transition. Momal’s experience shows that homesickness exacerbates the difficulties of the academic aspect of the transition year, creating a kind of double jeopardy for the students. They not only endure the emotional toll of homesickness, which negatively impacts their studies, but this effect on studies causes further stress to the students.

The other aspect of this double jeopardy effect is evident in the students’ inability to form friendships network during the sojourn and live in a profound sense of loneliness.

I haven’t had a friend now like in five years. I mean what you call a real friend. I am away from my real friends and family. They are back home. That is my country and society. This is a new society, not mine. My classmates and other students that I have started knowing here are individualistic. They are not real friends. So, I am alone most of the time, and this affects my mental health. In 2020, I got really sick. (Zarina, interview comment)

Zarina’s story illustrates the lasting impact of homesickness. Despite residing in her host country for 3 years, she remains deeply connected to her homeland, impairing her ability to forge new relationships. Viewing her current community as too “individualistic” for friendship, she becomes isolated, adversely affecting her health. This isolation not only diminishes her mental and physical well-being but also hinders her integration. The broader student experiences further highlight homesickness’s prolonged and severe mental and emotional toll. This intense distress limits their engagement with positive aspects of their new environment, such as potential friendships. Consequently, they feel perpetually out of place, struggling to bond with their new setting and access its social resources.

Social sphere represents relations, interactions, and life experiences with the local community outside the campus and academic sphere. The participants reported intense experiences of discrimination and exclusion in the social domain. These experiences affected them physically, psychologically, and financially, and had a negative impact on their integration into the local community. The data analysis revealed the following nature of the experience in this domain.

The findings revealed an intense experience of discrimination and social exclusion. These experiences were particularly salient among the Afghan, Pakistani and Indian students. These three nationalities represent numerically the largest groups of the international students in the country, and they do not share any cultural, linguistic, and racial features with the local population and these dissimilarities become the foundations of their greater vulnerability to discrimination and social exclusion compared to other nationality groups. The data revealed multiple layers of discrimination that these students experienced, and its negative and constrictive effects on them. These layers ranged from covert to overt and from passive to aggressive forms.

Many local people don’t like us, and it becomes clear from their treatment of us in the supermarket or other public places like local transport. They call us “industania” and consider us unhygienic. When you go to Bazar, you can feel that many shopkeepers start gossiping about you in their language. They say things about you which you do not understand but you know they are saying them about you, and they are bad things. You can feel that I am not a child. I am not paranoid. I am a very rational person, and their expressions say it all. It is very obvious. They don’t respect you. They look down upon you. (Priya, journal entry)

This excerpt from Priya’s journal highlights the perceived bigotry and bias of the host community against the students. It also shows how the locals stereotypically profile these students. The word ‘industania’ (a local variation of Hindustani) has disparaging religious, ethnic, and racial connotations and it seems that the host community use it for the otherization of the students coming from South Asian countries. The behavior and attitude of some of the locals, as detailed by Priya, is seemingly an act of covert racial aggression realized through behavioral and attitudinal cues. This discrimination and profiling make the students feel unwelcome, disrespected, and alienated, and renders their integration and acculturation in the host community difficult. It appears that the host community, instead of obliterating differences between themselves and the sojourning students, entrenches them further and deeper through their ethnocentric, bigoted, and biased attitude and behavior towards these international students.

The students also shared that the discriminatory and bigoted attitude of the host community against them did not always remain covert and implicit. They reported instances where this attitude turned into overtly hostile and aggressive actions in the form of unprovoked bullying and physical assaults.

The block I live in, the local people there really make us feel that they don’t like us—maybe because of my hijab. Once I was cooking my country’s dish and one of the next-door neighbors started banging on the door. When I opened the door, she started shouting at me and said that my cooking is spreading smell in the block, and she cannot tolerate it. She kicked the door a couple of times. She was so rude. I cannot even cook in my own apartment what I like. (Sarah, interview comment)

Sarah’s experience of a neighbor intruding in her apartment and bullying her illustrates that the students have no escape from the racial and xenophobic hostility and aggression of the locals even within the safety of their apartments. The only reason for this behavior of the locals, that can be deduced from these incidents, is the locals’ lack of empathy and intolerance for the cultural practices of these students. Cooking and food are part of one’s culture and it is difficult for individuals to abandon such cultural practices. However, it seems that the locals’ tolerance for these students’ following their native country’s cultural practices is substantially low. This indicates the insensitivity, cultural bias, and xenophobia of some of the locals who are not willing to afford these students their rightful cultural freedom even within the privacy of their residences. Sarah’s incident is a flagrant example of the disrespect and lack of understanding of the locals of the way of life of other communities and also confirms the extent of vulnerability of these students in their daily lives to the racial aggression of the locals. The troubling aspect of such an attitude is that it not only involves bullying but also escalates into violence. The students shared instances of experiencing unprovoked physical assaults due to their cultural practices and cultural differences compared to the locals.

I was attacked once or twice by local guys, maybe because I was wearing my national dress called shalwar kameez. So, one Friday when I was going to the mosque in a public bus, this guy for no reason attacked me and punched my face and started saying something in Kyrgyz and pointing at my dress again and again. My lip was ruptured and there was blood all over my clothes and no one around us even raised an eyebrow or tried to help me. (Kamran, interview comment)

The incident involving Kamran is an extreme case of xenophobia, resulting in physical assault and injury. A xenophobic individual could not tolerate a foreign student dressed differently and attacked him. The silence of other locals during the incident can be interpreted as their tacit approval and indifference to racially motivated violence against a foreign student. This indicates a prevailing trend of a hostile and apathetic attitude within the larger community towards these students. Somehow, they do not feel comfortable with the presence and cultural practices of these foreign students around them. While a few of them resort to overtly aggressive displays of this xenophobic attitude, others take a complacent position by failing to disapprove or intervene in such hostile actions. Such an environment of hostility and vulnerability has serious and critical implications for the students’ mental well-being, adjustment, and integration. They live in a persistent state of anxiety, stress, fear, and otherness.

The xenophobic and discriminatory attitude of the locals also had a financial impact on the students. They reported being charged higher prices for facilities, services, and commodities compared to the locals.

The taxis and other places charge us more. Like we pay more rent and more for certain services and things because we are foreigners. For example, if a taxi charge 20 soms from a local, it will charge 80 soms from us. They lie to you about prices in shops. They think you are a foreigner. Similarly, we are charged more rent for our apartments. Same is the case with visas and other government documents. We cannot get anyone of these without paying a bribe to various people. (Jamil, focus group discussion)

The quote highlights the financial exploitation that these students face in the host country. Seemingly, instead of being charged a fair and standard price, the locals tend to overcharge them. This financial discrimination and exploitation not only add to the cost of the students’ studies in the country but also contributes to their financial difficulties. This tendency of the locals is another indication of their apathy towards the students. The students also shared how this apathetic and discriminatory attitude limits their access to certain facilities such as renting accommodation.

They refuse to rent us apartments. Some renting agents and apartment owners clearly tell us that apartments are not available for Pakistani and Indian students. They turn us down. I paid an advance surety money through some source for an apartment but when the owner came to know that I was a Pakistani, she backed out and refused to rent it to us. We find it so difficult to rent an apartment. (Fatima, interview comment)

These instances and incidents of xenophobic, prejudiced, and discriminatory treatment highlights the challenging nature of the interaction of the international students with the local people in social spaces. The locals are not perceived as tolerant of the students’ presence and show little willingness to support, accommodate, and facilitate the students’ sojourn. The students generally experience extreme levels of passive and aggressive mistreatment, exclusion, economic exploitation, and cultural misunderstandings at the hands of the locals in their daily lives.

The students also shared their experience of personal security challenges. They shared that they do not feel very safe in the streets. They have to remain cautious and alert all the time when they are in the streets. This persistent sense of being unsafe and insecure has negative psychological effects on them.

I’m always on the watch in the streets especially when I go outside late in the evening or in the night due to some reason. There are drunk people in the streets. They try to harass you somehow and would even attack you or pick up a fight with you. I cannot do the simple thing of even going to the public park and spending some time there just sitting and relaxing and be to myself. For locals it is not a problem. But I am always afraid how someone will interpret my sitting there and pounce on me. (Ali, interview comment)

The concerns shared by Ali highlight another problematic aspect of the social sphere environment. While the students face difficulties because of discrimination and the prejudiced attitude of the locals, they also face safety issues in these spaces. This limits their mobility and recreation opportunities and heightens their sense of insecurity. They cannot enjoy simple activities like spending time in a public park due to apprehensions that their presence in that public place may potentially lead to some negative consequences. These concerns keep them in a persistent state of anxiety and vulnerability.

Another significant aspect of the social sphere’s experience was the financial difficulty. The students reported that an ever-increasing inflation in the country, due to geopolitical situation, is adding to their financial difficulties and indirectly affecting their study.

There is inflation. It is very difficult to cover our expenses. All products, groceries, and clothes— the prices are increasing because of inflation; especially, housing. After Russian Ukraine war, the rent of the apartments doubled and tripled. This is a challenge for students. Now five or seven students are living where before only one or two were living. There is no privacy, no space to study or talk to family members. It is so difficult to concentrate on study. (Jamil, interview comment)

The situation depicted by Jamil highlights how economic factors of the host community significantly affect the sojourning students. It reveals that international students’ lives are affected not only by their personal circumstances but also by local and global events and circumstances which involve the host community. In the particular case of this research, these circumstances are the inflation that the host community is experiencing and the ongoing Russian-Ukraine war. Both of these factors have collectively raised the cost of living for these students and have negatively affected their living conditions. Consequently, the increasing cost of accommodation compelled these students to live in crowded apartments to lower their rent expenses. However, this has come at the expense of their personal space which made their living conditions more challenging and negatively affected their studies because they find it difficult to concentrate on their studies in their crowded apartments. This impact of the financial challenges has implications for their mental and physical well-being.

Academic sphere refers to the formal learning environment and context such as university. Academic sphere experiences represent encounters that the students had in this formal learning environment and encompasses experiences related to teaching and learning in classrooms, attending lectures, participation in cocurricular and extracurricular activities, interaction with teachers and fellow students, assessment, and other units or departments of the university. Following are the details of the students’ experiences in the academic sphere.

The findings of the data analysis also revealed the challenging aspects of the students’ academic experience. They reported their dissatisfaction with the overall academic situation. They opined that their academic expectations were not met.

My impression of the university and study here is not as positive as I had. It was a great deceit. The university wrote big things on their website. I thought I was going for a world class education with some world class professors. There will be a lot of research. But all this is nowhere. The professors cannot speak proper English. The universities do not have the basic labs and other facilities. I feel like cheated. (Ahmed, interview comment)

The quote reveals a sense of disappointment and frustration arising from a disparity between the students’ expectations and the actual experience of the academic standards and quality. The students seemed to be disillusioned with the academic quality of their institutions. They were attracted to the country by the claims and promises projected on the university websites. However, after spending some time in these universities, they discovered that the reality of academic quality did not live up to the promises made. This disparity between the high claims of academic quality and standards and the actual dismal reality leads to a sense of betrayal, and they feel cheated.

The students also expressed their dissatisfaction with the curriculum. They reported that the programs were not optimally designed and appropriately tailored to their future needs.

The academic aspects are not really suited for the major that I opted for. There are a lot of courses which in my perspective are not related to our major, but they are all mandatory and we have no other choice. If you fail a course, you fail everything. There is not as wide a range of courses available as it should be, and I think this will not help my future. (Diyor, focus group discussion)

The quote highlights the limitations in the curriculum that the students experienced. It represents their perception of a disconnect between their current learning and their future aspirations. Further, it also shows that the students have limited freedom of choosing what they want to study, and they have to perform in a high-stake environment which implies that they also experience greater academic pressure and stress.

The data also revealed the students’ dissatisfaction with the attitude of the local faculty members. They complained about their biased, unjust, and prejudiced attitude towards the international students.

Local professors are nice and supportive of their Kyrgyz students. They give them more opportunities. But they are not so nice with us. Some of my Afghan classmates wear hijab, and these professors always treated them in a way to show that they don’t like them. They also gave good grades to the local students and gave them easier assignments but put more and more pressure on us. They know that there are foreign students in class who do not speak Russian, yet they would start speaking or teaching in Russian in the middle of the lessons. (Sarah, journal entry)

The quote reflects the students’ perception of the prejudice and biased treatment of the faculty members. It seems that the local faculty members not only culturally discriminated against the international students by frowning on their dress choices but also academically discriminated against them by awarding them low grades compared to local students and assigning them different tasks. This shows that these foreign students not only face discrimination and prejudices in the social sphere but also in the academic sphere. It also confirms the dismal situation in the institutions. These perceptions and complaints of these students suggest a lack of fairness, equity and consistency in evaluation and assessment practices of the faculty members. It indicates that students are assessed and graded on different and arbitrary criteria resulting in an unequal and unfair educational experience. Such practices have negative implications for the credibility of the institutions and are also a reason for their dissatisfaction and frustration with the academic quality and standards.

Alongside complaints of the faculty members’ discriminatory attitude, the students also reported experiencing similar prejudiced attitudes of the local students towards them.

In my law course, the teacher put us in groups, and I was the only foreigner in my group. At the beginning of the group discussions, the local students asked me in English where I am from and that was the only time, they spoke to me in English. After that, till the end of the whole group work, they talked to each other in Russian. It was always like this and then finally I had to drop that course. (Momin, focus group discussion)

Momin’s experience shows that the local students did not make any accommodations for his lack of Russian language proficiency. They held their group discussions in Russian instead of English, even though they knew English, as is apparent from their initial conversation with Momin. This deliberate choice of the local lingua franca over a global lingua franca kept Momin excluded from the group discussions. Consequently, this insensitive attitude of the local students had a negative effect on Momin’s learning experience in that course, leading him to eventually drop the course. Thus, the way Momin was treated by his groupmates significantly impacted the outcomes of his participation in that course. This experience, along with the faculty members’ tendency to use Russian in their lessons, highlights the inequitable and exclusionary social dynamics within the academic environment. It appears that there is a lack of an inclusive and supportive learning environment. The local faculty and students are not fully aware of the importance of using a language that is commonly and equally understood by both local and foreign students. For their communicative ease, they tend to use Russian language, creating a barrier for foreign students for their participation in learning activities. These kinds of social dynamics negatively impact the engagement of foreign students fostering a sense of discrimination and exclusion among them.

The students complained about the lack of a support system in the universities. They shared that in many cases, the universities do not help with visa and other issues, such as finding accommodation or acquiring necessary documents from the government offices.

I have been without a visa for many months. I needed the university support for this since it was not possible without that. They needed to give some documents to the ministry, but they never cared. I feel university should care more for us and help us with these issues. We do not know the ministry offices and do not speak the local language, and all this makes it very difficult here. (Rajesh, journal entry)

The quote highlights the nonchalant and complacent attitude of the university towards the necessary issue of visa acquisition. Being without a visa is a significant challenge for any international student and university support is crucial and vital in resolving visa-related issues. Rajesh’s experience underscores the reality that the student affairs support system either does not exist in many universities or does not work in a well-coordinated manner. This lack added a great deal of stress and anxiety and this compounded the overall challenges they face. It not only severely restricted their ability to perform their daily life tasks but adversely affected their learning and development as explained by Sarah in the following quote.

Initially they gave a visa for three months only. Then it took ten months to renew it. It was so difficult to go to banks because I needed this registration card and without a visa, I could not get it. I was living here illegally for ten months. Without visa banks were not giving me money. It was so hard. I needed to find people to beg them to the bank transactions for me from their account. I was also not able to attend many development and learning opportunities because I needed to travel to them and without a visa I was stuck in this country. I kept going and asking my university to help. But you know when you a foreigner and a student, you cannot argue or impose yourself. You have no power. So, I have to live with it. (Sarah, interview comment)

The quote highlights how the students faced significant delay in renewing their visa due to the lack of a support system and the apathy within the system. It highlights the bureaucratic inefficiencies in the visa renewal process. For some of the students, these challenges changed their stay in the country from legal to illegal, impacting them in multiple ways. As a result, they faced many everyday life practical difficulties such as restricted access to banking services and limited mobility which prevented them from attending important development and learning opportunities. Deprivation from such opportunities hindered their personal and professional growth. The situation also affected their emotional and mental wellbeing. They felt powerless and lived in a state of stress, uncertainty, and frustration. The situation reflects the bureaucratic and administrative difficulties that these students faced overall and also highlights their feelings of helplessness in dealing with these difficulties.

The students also shared their experience of challenges and discrimination that they face in the academic sphere due to their lack of proficiency in Russian or Kyrgyz language. They reported that this language limitation hinders their access to various opportunities.

For example, there are internship opportunities in my university. But all good opportunities are grabbed by local students because they can speak Russian and Kyrgyz and the employers prefer them. We do not get these opportunities because we cannot speak these languages. (Fatima, journal entry)

The quote depicts the situations where the international students are deprived of growth and development opportunities due to their linguistic limitations. Russian is a lingua franca and Kyrgyz is the national language in Kyrgyzstan, English is still considered a foreign language and is not widely used. While international students have English language proficiency, they lack competence in either Russian or Kyrgyz. This linguistic limitation not only hinders their social and cultural integration but also negatively impacts their access to the learning and development opportunities, particularly in the form of internships because employers naturally prefer local students who are fluent in local languages as it facilitates communication and integration in the workplace. However, this situation of the international students highlights the importance of language support programs for them to bridge the language gap and increase their chances of securing internship opportunities.

ISM is diversifying, with emerging destinations in the semi-periphery and periphery. Yet, research on international student (IS) experiences in peripheral destinations remains limited, preventing a comprehensive understanding. This study investigated IS experiences in a less-researched peripheral hub, Kyrgyzstan, using a qualitative approach. Findings highlighted challenges in personal, social, and academic domains.

Homesickness was predominant, aligning with prior research (Götz et al., 2019; Saravanan et al., 2019). This homesickness has been linked to socioemotional challenges, health problems, and academic struggles (Saravanan et al., 2017; Tsevi, 2018; Götz et al., 2019; Nauta et al., 2020).

Students reported discrimination, safety concerns, and financial issues. Discrimination was particularly marked, with the ethnocentric host community branding them as “industania,” leading to “otherization.” This discrimination hindered cultural practice, equitable service costs, and housing opportunities. This confirms the findings of the previous research (Duru and Poyrazli, 2011; Tran and Hoang, 2020; Yang et al., 2022). Safety concerns which in this study directly impacted students’ satisfaction, limiting freedom and recreational activities were also reported earlier by Lê et al. (2013). Financial stressors echoed prior studies (Jones et al., 2018).

Participants highlighted teaching quality, faculty and peer attitudes, and institutional support. Although many findings mirrored existing research (Middlehurst, 2011; Trahar, 2014; Sandekian et al., 2015; Quan et al., 2016; Yu and Wright, 2017; Smith, 2020; Cena et al., 2021), a unique sense of betrayal emerged. IS often seek better education, but the disparity between expectations and actual experiences in Kyrgyzstan was stark, diverging from prior findings.

To dissect these findings more profoundly, they were interpreted through Bourdieu’s theoretical lens, which encompasses the triad of field, capital, and habitus. In Kyrgyzstan, IS “enter a new space and navigate their positionality related to the interaction between different economic, and social conditions and rules associated with the original and new localities in the home and host countries” (Tran & Hoang, 2020, p. 601).

Upon entering the destination country, the students step into a new field. Throughout their stay, they also navigate the subfields encompassing personal, social, and academic aspects of their sojourning life. These main and the subfields represent, as per Bourdieusian theory, encompass an “autonomous social microcosm” (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992, p. 97) hosting “people who dominate and people who are dominated. Constant, permanent relationships of inequality operate inside this space, which at the same time becomes a space in which various actors struggle for the transformation or preservation of the field” (Bourdieu, 1998a, p. 40–41). From this viewpoint, IS in Kyrgyzstan essentially hold a position of subordination within this microcosm. They occupy an enduringly inferior hierarchical status compared to the host community. The host community’s dominant position and the students’ subordination are evident in the discriminatory and exclusionary treatment that IS receive in both social and academic spheres. This treatment and attitude signify the host community’s effort to maintain their dominant position. However, the sojourning students do not merely accept this dominance positively; they engage in a struggle for transformation. This struggle materializes through their cultural practices, despite facing hostility from the host community. Consequently, the challenging nature of the students’ experience stems from the ongoing power struggle between the host community’s quest for dominance and the students’ resistance to it.

Capital plays a pivotal role in this ongoing struggle. Adopting a Bourdieusian perspective, capital serves as “the basis of power. Possession of capitals places actors in social hierarchies and allows them to influence their value” (Joy et al., 2018, p. 2544). In essence, capital equips individuals with an advantage within a field. For this particular group of students, their hierarchically inferior status in the field can be attributed to their lack of relevant capital. Although they have accessed the social and academic field of the host country through their economic capital, this capital’s value is limited— it merely serves as an entry pass. Within the host country’s field, the most prized capital is social (local friends, faculty, and support staff) and cultural (local language and cultural practices). Unfortunately, the students are deficient in both these forms of the capital due to their absence of local social networks and proficiency in local languages. These deficits compound their disadvantages. Consequently, their exploitation through unfair transportation fare and prices, housing exclusions, unjust course evaluations, internship restrictions, in-class group activity exclusions, and difficulties in accessing visa and university support services can be linked to their inadequacy in social, cultural, and linguistic capital. Similarly, the experience of homesickness and their struggle to integrate within the local community also trace back to their shortcomings in these forms of capital.

In determining the students’ position within the field, capital is interwoven with the role of habitus. Habitus, described as “durable, transposable dispositions” (Bourdieu, 1990, p. 53), functions as “product of structure, producer of practice, and the reproducer of structure” (Wacquant, 1998, p. 221). In simpler terms, actors’ standing in a specific field depends on their habitus (Maton, 2008). In the context of this study, the students enter the host country field bearing certain dispositions that clash with those of the host community. For instance, the students’ disposition aligns with their home country’s cultural practices, and through their agency, they aspire to uphold the social and academic culture they brought from their homeland. Conversely, the host community’s habitus favor maintaining the academic, social, and cultural status quo— a stance that secures their dominance and advantage. However, the students’ habitus do not equate this status quo with economic, cultural, or social gain. Consequently, they seek to reshape their field’s existing positions through their academic, social, and cultural practices. This endeavor is perceived by the local community as a challenge to their dominant position, triggering a violent and xenophobic response aimed at suppressing the students’ efforts to restructure the established academic and cultural practices. Thus, the persistent tension and conflict between the sojourning students and the host community— reflected in discriminatory, exclusionary, xenophobic, and violent actions from the host community, and the students’ withdrawal, dissatisfaction, and resistance— is fundamentally rooted in the clash of opposing habitus. This role of habitus also underscores that sojourning students do not exist in a passive, submissive position within the host community. Instead, they tenaciously strive to exert their agency and navigate the constraints imposed by their context and limited capital. This determination is aimed at acquiring the capital necessary for their future positional advantage within the larger field of life—a primary reason for their venture into the destination country’s field.

Based on this interpretation of the students’ experience through a Bourdieusian lens, several conclusions can be drawn about the inherently challenging nature of international students’ experiences in the destination country. This challenge stems from the clash of habitus. While economic capital serves as a mere passport for entering the host country’s higher education field, it is the possession of social and cultural capital within the field that truly empowers students in their daily lives. Therefore, those engaged in facilitating the international students’ experience in Kyrgyzstan must prioritize the development of their social and cultural capital even before they enter the country. Simultaneously, efforts must be directed towards fostering a shift in the habitus of the host community. Such an evolution would involve cultivating an environment of increased tolerance and acceptance towards international students. Rather than interpreting the students’ cultural practices as a threat to their own culture, the host community should perceive it as a dynamic aspect of diversity and a channel for cultural exchanges. This transformation would lay the foundation for a more welcoming and harmonious environment for international students within the country. It would contribute not only to an increased flow of international students towards this destination but also enhance the quality of higher education and drive economic gains for the country.

This study, rooted in Bourdieu’s theoretical framework, delved into the experiences of international students in a peripheral education destination using a qualitative multimethod approach. This facilitated a comprehensive analysis of students’ personal, social, and academic challenges in their host country. The Bourdieusian framework elucidated the complex interactions of habitus and capital, revealing power dynamics based on capital distribution that reinforced discrimination, xenophobia, and a sense of “otherness” for students. This hindered their assimilation into Kyrgyzstan’s societal structure.

Simultaneously, the students’ agency, while restricted by overarching power structures, was evident in their responses to daily challenges, showcasing their resilience and adaptability. Despite the limitations of a qualitative design, the findings are impactful. They stress the need for institutional reforms and societal shifts to improve international student experiences in Kyrgyzstan. Priorities include combating discrimination, fostering inclusivity, addressing power disparities, and nurturing a favorable learning environment. Additionally, language assistance, enhanced student support, and cultural integration initiatives are vital for alleviating challenges in both social and academic realms.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for this study. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

HE: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Altbach, P. (2006). Globalization and the university: realities in an unequal world. In J.J.F. Forest and P.G. Altbach International handbook of higher education, Springer International Handbooks of Education: Dordrecht 18.

Altbach, P. (2013). “Globalization and forces for change in higher education” in The international imperative in higher education (Rotterdam: SensePublishers).

Andrade, M. S. (2009). The effects of English language proficiency on adjustment to university life. Int. Multilingual Res. J. 3, 16–34. doi: 10.1080/19313150802668249

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. Available at: https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/fr/bourdieu-forms-capital.htm

Bourdieu, P. (1993). “Some properties of field” in Sociology in question (Sage Publications Ltd.), 72–77.

Bourdieu, P. (1998b). “The new capital” in Practical reason: on the theory of action (Stanford University Press), 19–33.

Bourdieu, P., and Wacquant, L. (1992). “The logic of field” in An invitation to reflexive sociology (Cambridge: Polity Press), 94–114.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, L. (2009). An ethnographic study of the friendship patterns of international students in England: an attempt to recreate home through conational interaction. Int. J. Educ. Res. 48, 184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2009.07.003

Brown, L., and Holloway, I. (2008). The adjustment journey of international postgraduate students at an English university. J. Res. Int. Educ. 7, 232–249. doi: 10.1177/1475240908091306

Campbell, J., and Li, M. (2008). Asian students’ voices: an empirical study of Asian students’ learning experiences at a New Zealand university. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 12, 375–396. doi: 10.1177/1028315307299422

Cao, C., Zhu, C., and Meng, Q. (2018). Chinese international students’ coping strategies, social support resources in response to academic stressors: does heritage culture or host context matter? Curr. Psychol. 40, 242–252. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9929-0

Cena, E., Burns, S., and Wilson, P. (2021). Sense of belonging and the intercultural and academic experiences among international students at a University in Northern Ireland. J. Int. Stud. 11, 812–831. doi: 10.32674/jis.v11i4.2541

Chamberlain, K., Cain, T., Sheridan, J., and Dupuis, A. (2011). Pluralisms in qualitative research: from multiple methods to integrated methods. Qual. Res. Psychol. 8, 151–169. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2011.572730

Chan, S.-J. (2012). Shifting patterns of student mobility in Asia. High Educ. Pol. 25, 207–224. doi: 10.1057/hep.2012.3

Clow, K., and James, K. (2014). “Qualitative research” in Essentials of marketing research: Putting research into practice (London: Sage Publications), 95–126.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. 8th Edn. New York: Routledge.

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. (2018). “The Sage handbook of qualitative research” in The Sage handbook of qualitative research. eds. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. 5th ed (London: Sage Publications, Inc.).

Duru, E., and Poyrazli, S. (2011). Perceived discrimination, social connectedness, and other predictors of adjustment difficulties among Turkish international students. Int. J. Psychol. 46, 446–454. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2011.585158

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., and Borg, W. R. (2003). Educational research, an introduction. New York: Allyn and Bacon.

Gilmartin, M., Coppari, P. R., and Phelan, D. (2021). Promising precarity: the lives of Dublin’s international students. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 47, 4723–4740. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732617

Götz, F. M., Stieger, S., and Reips, U.-D. (2019). The emergence and volatility of homesickness in exchange students abroad: a smartphone-based longitudinal study. Environ. Behav. 51, 689–716. doi: 10.1177/0013916518754610

Han, X., Han, X., Luo, Q., Jacobs, S., and Jean-Baptiste, M. (2013). Report of a mental health survey among Chinese international students at Yale University. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 61, 1–8. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.738267

Hesse-Biber, S. N., Rodriguez, D., and Frost, N. A. (2015) in A qualitatively driven approach to multimethod and mixed methods research. eds. S. N. Hesse-Biber and R. B. Johnson (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Hunter, A., and Brewer, J. D. (2015) in Designing multimethod research. eds. S. N. Hesse-Biber and R. B. Johnson (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Jindal-Snape, D., and Rienties, B. (2016). “Multiple and multi-dimensional transitions of international students to higher education” in Multi-dimensional transitions of international students to higher education. eds. D. Jindal-Snape and B. Rienties (New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group), 260–283.

Jones, P. J., Park, S. Y., and Lefevor, G. T. (2018). Contemporary college student anxiety: the role of academic distress, financial stress, and support. J. Coll. Couns. 21, 252–264. doi: 10.1002/jocc.12107

Joy, S., Game, A. M., and Toshniwal, I. G. (2018). Applying Bourdieu’s capital-field-habitus framework to migrant careers: taking stock and adding a transnational perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 31, 2541–2564. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2018.1454490

Lê, Q., Auckland, S., Nguyen, H. B., and Terry, D. R. (2013). The Safety of International Students in a Regional Area of Australia: Perceptions and Experiences. Journal of the Australian & New Zealand Student Services Association.

Lipura, S. J. D. (2021). Deconstructing the periphery: Korean degree-seeking students’ everyday transformations in and through India. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 16, 252–275. doi: 10.1177/17454999211038769

Liu, Y., Chen, X., Li, S., Yu, B., Wang, Y., and Yan, H. (2016). Path analysis of acculturative stress components and their relationship with depression among international students in China. Stress. Health 32, 524–532. doi: 10.1002/smi.2658

Ma, J., and Wen, Q. (2018). Understanding international students’ in-class learning experiences in Chinese higher education institutions. Higher Educ. Res. Develop. 37, 1186–1200. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2018.1477740

Marginson, S. (2014). Student self-formation in international education. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 18, 6–22. doi: 10.1177/1028315313513036

Maton, K. (2008). “Habitus” in Pierre Bourdieu: key concepts. ed. M. Grenfell (London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group), 48–64.

Middlehurst, R. (2011). Getting to grips with academic standards, quality, and the student experience. Leadership Foundation for Higher Education. Available at: www.bcu.ac.uk/cuc

Mik-Meyer, N. (2020). “Multimethod qualitative research” in Qualitative research. ed. D. Silverman (London: Sage), 357–374.

Morgan, D. (2008). “Focus groups” in The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (London: SAGE Publications, Inc.), 352–354.

Nachatar Singh, J. K., and Jack, G. (2021). Challenges of postgraduate international students in achieving academic success. J. Int. Stud. 12. doi: 10.32674/jis.v12i2.2351

Naidoo, R. (2004). Fields and institutional strategy: Bourdieu on the relationship between higher education, inequality and society. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 25, 457–471. doi: 10.1080/0142569042000236952

Naidoo, D. (2015). Understanding non-traditional PhD students habitus – implications for PhD programmes. Teach. High. Educ. 20, 340–351. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2015.1017457

Nauta, M. H., Rot, M., Schut, H., and Stroebe, M. (2020). Homesickness in social context: an ecological momentary assessment study among 1st-year university students. Int. J. Psychol. 55, 392–397. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12586

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Dickinson, W. B., Leech, N. L., and Zoran, A. G. (2009). A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. Int J Qual Methods 8, 1–21. doi: 10.1177/160940690900800301

Park, H., Lee, M.-J., Choi, G.-Y., and Zepernick, J. S. (2017). Challenges and coping strategies of east Asian graduate students in the United States. Int. Soc. Work. 60, 733–749. doi: 10.1177/0020872816655864

Popescu, C. A., and Buzoianu, A. D. (2017). Symptoms of anxiety and depression in Romanian and international medical students: relationship with big-five personality dimensions and social support. Eur. Psychiatry 41:S625. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1011

Poyrazli, S., and Lopez, M. D. (2007). An exploratory study of perceived discrimination and homesickness: a comparison of international students and American students. J. Psychol. 141, 263–280. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.141.3.263-280

Quan, R., He, X., and Sloan, D. (2016). Examining Chinese postgraduate students’ academic adjustment in the UK higher education sector: a process-based stage model. Teach. High. Educ. 21, 326–343. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2016.1144585

Ravitch, S. M., and Carl, N. M. (2019). Qualitative research: bridging the conceptual, theoretical, and methodological. London: Sage Publications.

Sandekian, R. E., Weddington, M., Birnbaum, M., and Keen, J. K. (2015). A narrative inquiry into academic experiences of female Saudi graduate students at a comprehensive doctoral university. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 19, 360–378. doi: 10.1177/1028315315574100

Saravanan, C., Alias, A., and Mohamad, M. (2017). The effects of brief individual cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and homesickness among international students in Malaysia. J. Affect. Disord. 220, 108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.037

Saravanan, C., Mohamad, M., and Alias, A. (2019). Coping strategies used by international students who recovered from homesickness and depression in Malaysia. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 68, 77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.11.003

Smith, C. (2020). “International students and their academic experiences: student satisfaction, student success challenges, and promising teaching practices” in Rethinking education across Borders (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 271–287.

Smith, R. A., and Khawaja, N. G. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 35, 699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.08.004

Smith-Sullivan, K. (2008). “Diaries and journals” in The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (London: SAGE Publications, Inc.), 213–215.

Soong, H., Stahl, G., and Shan, H. (2018). Transnational mobility through education: a Bourdieusian insight on life as middle transnationals in Australia and Canada. Glob. Soc. Educ. 16, 241–253. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2017.1396886

Teichler, U. (2017). Internationalisation trends in higher education and the changing role of international student mobility. J. Int. Mobility 5, 177–216. doi: 10.3917/jim.005.0179

Thomson, P. (2008). “Field” in Pierre Bourdieu: key concepts. ed. M. Grenfell (London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group), 65–80.

Tight, M. (2022). Internationalisation of higher education beyond the west: challenges and opportunities – the research evidence. Educ. Res. Eval. 27, 239–259. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2022.2041853

Trahar, S. (2014). ‘This is Malaysia. You have to follow the custom here’: narratives of the student and academic experience in international higher education in Malaysia. J. Educ. Teach. 40, 217–231. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2014.903023

Tran, L. T., and Hoang, T. (2020). “International students: (non) citizenship, rights, discrimination, and belonging” in The Palgrave handbook of citizenship and education (London: Springer International Publishing), 599–617.

Tseng, W.-C., and Newton, F. (2002). International students’ strategies for well-being. Coll. Stud. J. 36, 591–597.

Tsevi, L. (2018). Survival strategies of international undergraduate students at a public research midwestern university in the United States: a case study. J. Int. Stud. 8, 1034–1058. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.1250404

Vergara, M. B., Smith, N., and Keele, B. (2010). Emotional intelligence, coping responses, and length of stay as correlates of acculturative stress among international university students in Thailand. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 5, 1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.315

Wacquant, L. (1998). “Pierre Bourdieu” in Key sociological thinkers (London: Macmillan Education UK), 215–229.

Yang, F., He, Y., and Xia, Z. (2022). The effect of perceived discrimination on cross-cultural adaptation of international students: moderating roles of autonomous orientation and integration strategy. Curr. Psychol. 42, 19927–19940. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03106-x

Ying, Y.-W. (2005). Variation in acculturative stressors over time: a study of Taiwanese students in the United States. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 29, 59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.04.003

Yu, B., and Wright, E. (2017). Academic adaptation amid internationalisation: the challenges for local, mainland Chinese, and international students at Hong Kong’s universities. Tert. Educ. Manag. 23, 347–360. doi: 10.1080/13583883.2017.1356365

Zheng, M., McClay, C.-A., Wilson, S., and Williams, C. (2015). Evaluation and treatment of low and anxious mood in Chinese-speaking international students studying in Scotland: study protocol of a pilot randomised controlled trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud 1:22. doi: 10.1186/s40814-015-0019-x

Keywords: international students, peripheral destinations, international student experience, Bourdieu, student mobility, internationalization, higher education

Citation: Eusafzai HAK (2023) Inhabiting the peripheries: a Bourdieusian exploration of international students’ encounters in Kyrgyzstan. Front. Educ. 8:1291357. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1291357

Received: 09 September 2023; Accepted: 01 November 2023;

Published: 28 November 2023.

Edited by:

Mohammad Jamal Khan, Saudi Electronic University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Shakir Saleem, Saudi Electronic University, Saudi ArabiaCopyright © 2023 Eusafzai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hamid Ali Khan Eusafzai, ZXVzYWZ6YWkuaEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.