- Global, Innovative, Forefront, Talent Management (GIFT), Research Professor – North West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Doctoral education in Africa is a rigorous journey that demands unwavering commitment from both students and mentors. It involves original research aimed at contributing new knowledge to the academic realm, making it a formidable scholarly pursuit. The pivotal players in this endeavor are the students, their mentors, and the higher education institutions. This paper delves into the strategies and recommendations for enhancing excellence in doctoral education across Africa. One significant approach is fostering entrepreneurship among doctoral students, empowering them to develop businesses and cultivating an innovative culture to broaden their career prospects. Additionally, robust academic support systems play a crucial role, encompassing services like academic writing centers, article writing workshops, and well-structured mentoring programs. These resources bolster research and writing skills, aid in crafting research proposals, and facilitate publishing, thereby boosting students’ self-esteem. International partnerships offer opportunities for academic mobility, through scholarships, exchange programs, and funding. This international exposure fosters cross-cultural understanding and academic excellence. Collaborations, both with academia and industry, enable problem-solving and interdisciplinary research, further enriching the doctoral experience. Exchange programs serve dual purposes by providing funding and ensuring quality standards are met in doctoral programs. These measures collectively contribute to the advancement of excellence in doctoral education in Africa, nurturing a skilled workforce capable of driving innovation and development on the continent. This theoretical paper relies on extensive scrutiny of reputable sources and accredited journals. The findings emphasize the significance of collaborations and academic support systems in achieving academic success, which, in turn, leads to entrepreneurship, job creation, and wealth generation. Adequate funding and motivated supervisors and students are foundational elements for a thriving doctoral program. Overall, these interventions and recommendations pave the way for Africa’s doctoral students to reach their full potential, contributing to the continent’s growth and prosperity.

Introduction and background

The twenty-first century is recognized as a knowledge era, in which education is recognized as a key force for modernization and development. In this regard, higher education must therefore play a central role in catapulting this global development. African higher education, particularly doctoral education, faces unprecedented challenges. The narrative on African doctoral education has been disproportionately exhibited in a deficit mode in international comparison and has been persistently and permanently highlighted as being in a crisis. If the continent is to advance, her academic institutions must overcome the existent obstacles in providing the education, research, and service needed, particularly through advancement on the doctoral education front. Africa, a continent with fifty-four countries, a population of 1,433,442,635 (16.72% of the total world population) (United Nations, 2023), and which will be home to a quarter of the global youth population by 2050, has only 1,682 universities. In global terms, this means that Africa’s share of the world’s 18,772 higher education institutions remains low at a paltry 8.9%, compared to 37% for Asia, 21.9% for Europe, 20.4% for North America and 12% for Latin America and the Caribbean (Zeleza, 2021). The total number of students in African higher education institutions in 2017 stood at 14.6 million out of 220.7 million worldwide, or 6.6%. By international standards, Africa is the least developed region in terms of higher education institutions and enrollments. Waruru (2022) recommends that African universities should produce as many as 100,000 PhDs over a 10-year period, and these should be mandated to produce research for solving or providing insight into the development challenges plaguing the African continent, such as job creation for the youth, population explosion, disease, climate change, food insecurity and political instability (Waruru, 2022) among a plethora of other genuine developmental needs of the continent’s young and bourgeoning population. The African Union and the AAU, and furthermore government policy pronouncements like South Africa’s National Development Plan (NDP) have continued to give voice to the need to up the stakes in terms of raising the PhD production and throughput numbers.

Problem statement

While global and regional goals, such as Agenda 2030 and the African Union’s Continental Education Strategy for Africa; AU Agenda 2063 and The Africa we want, position higher education as an engine for development and job creation (Adu, 2020), African universities currently function in very difficult, volatile and unpredictable environments, both in terms of the social, economic, and political problems facing the continent as well as in the context of globalization (Wangenge-Ouma and Kupe, 2020).

These contexts negatively impact the ability of universities in some of Africa’s regions to provide mentors who have adequate doctoral promotion and supervision skills resulting in the inadequacy of properly qualified lecturers particularly in East Africa and Southern African regions. Furthermore, in another recent edition of the University World News, because of these and other challenges like funding, Africa suffers a unique dearth of students willing to enroll for PhD education, since such candidates prefer to pursue these studies elsewhere where there is better funding and potential to complete these studies in record time.

Due to this inadequacy or scarcity of public funding (Zeleza, 2021), African universities are plagued with serious shortages of published materials, books and journals as all major sources of income are constrained, including tuition fees, auxiliary income, research grants, government subventions, philanthropic donations and concessionary loans. According to the latest UNESCO Science Report, 2021, Africa spends only 0.59% of its GDP on research and development, compared to a world average of 1.79%. It therefore comes as no surprise that research output is low, accounting for a mere 1.01% of global research and development expenditures, 2.50% of global researchers and 3.50% of scholarly publications, compared to 45.7%, 44.5% and 48.0%, respectively, for a region such as Asia. The entire African continent, with a population of 1.3 billion, produces fewer scholarly publications than Canada (3.60%), with a population of 37.7 million! (UNESCO Science Report, 2021) The data for the cutting-edge fields of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) (artificial intelligence and robotics, biotechnology, energy, materials, nanoscience and nanotech and opto-electronics) is even more abysmal, more so with the characteristic gross underinvestment in electronic infrastructure. Under COVID-19, cash-strapped African universities were forced to close, and then transition to online teaching, which many universities found very difficult to do and almost ground to a halt.

African universities are under pressure to seek ways to cope with a diverse variety of challenges (such as brain-drain, technological issues, political interference, issues of funding; Leadership and Management challenges and many more) and still thrive. The role of Doctoral education in advancing excellence in African higher education cannot be overemphasized.

Research question

On a continent which faces such a plethora of challenges, what type of doctoral education should we promote on the continent, and what interventions and recommendations can be undertaken to strengthen the doctoral education landscape?

Aim

The aim of this conceptual paper is to propose the type of doctoral education that is suitable for Africa, and to extensively explore and propose relevant interventions for the advancement of excellence in doctoral education in Africa.

The theory of change as the underpinning philosophy

The Theory of Change is a theory that was developed to assist in understanding and explaining how change takes place and how the interventions lead to desired outcomes and goals (French et al., 2020). It is a process for individual and organizational learning that includes analysis of actions, outcomes, and consideration of the explicit and implicit assumptions about how actions and outcomes are interconnected (Taplin and Clark, 2012; Valters, 2015). Key principles/tenets of this theory are an emphasis on learning through the complexity of problem situations, a commitment to have a process led by those most affected by a particular problem, and a recognition that the theory is a “compass” for navigating change as opposed to a defined map or blueprint (James, 2011; Valters, 2015). For the purposes of this paper, the theory of change might involve conducting assessments of African doctoral students’ current knowledge and skills, developing targeted interventions to address the existent gap between what they are achieving now and what they ought to be achieving in their current context (the necessary changes to be effected); monitoring progress, and evaluating the effectiveness of the interventions in terms of continental development.

Literature review

Models of PhDs

The world over, the increased openness of national borders has resulted in not only the accelerated flow of goods and services, but also of knowledge and information; of enhanced mobility of high-skills labor; and the new organizational forms and delivery modes that have resulted from the ICT revolution (Academy of Science of South Africa [ASSAf], 2010). The rapid rate of obsolescence that has come about as a result of the explosive growth in the stock of global knowledge have led to a sustained shift from the emphasis of acquiring a particular body of knowledge to developing the skills for acquiring new knowledge and the capacity for using knowledge as a resource in addressing societal needs, demands that have given rise to new kinds of knowledge, new modes of knowledge production and dissemination, as well as the need for developing effective networking and partnerships (Sawyerr, 2004; Eugste et al., 2018; Hassan, 2020). The African Doctoral education is thus brought under the spotlight as a way of ensuring her modernization and development.

In general, a doctoral study is one that aims to produce highly skilled and knowledge graduates who are capable of transferring their intellectual and technical expertise to wide-ranging global contexts (Academy of Science of South Africa [ASSAf], 2010; Teferra, 2015, Council on Higher Education [CHE], 2022). A doctorate is considered as a key qualification that defines the quality and level of a country’s research standards; and is in turn, viewed as the acceptable way of acquiring, generating and using research-based knowledge in key strategic areas of national interest. There are several models of PhD education and training around the world. According to Fredua-Kwarteng (2023), there are several models:

The first model is the individual PhD, which involves an individual writing a scholarly thesis under the supervision of a professor who is an expert in the specific field. The individual does not attend courses, lectures or seminars, but they are required to write and then defend their dissertation before a panel of experts in a colloquium. The model is most prevalent in Germany, Australia and South Africa.

The second model, very common in North America, the United Kingdom and several other European countries is called the traditional or structured model, and it requires the individual to attend rigorous courses, lectures and seminars with fellow doctoral students. At the end of it all, the individual must produce a dissertation/thesis with equal scholarly and research vigor as the individual PhD; also, under the supervision of an expert in the field and then orally defend it before a panel of expert evaluators.

The third is the PhD by publication and is an emergent model in some countries in the Western world, a few select universities in South Africa, such as the University of the Free State. This type takes on all the features of the traditional model, but in addition, the individual is required to publish an average of three to twelve inter-related articles in specified academic journals from their dissertation project. The traditional PhD, in comparison to this type, has been subjected to severe criticism.

The fourth type, known as the doctoral capstone projects, involve intensive research and writing but primarily focus on developing innovative, implementable solutions to existing real-life problems. The individual must demonstrate before a committee of experts how their proposed solution can be implemented. For example, a doctoral student in architectural engineering may craft their study on design of buildings that maximize on the use of green energy, which makes an impact on the African and Global energy crises we are experiencing at present.

The desired African PhD model

With the existence of these several models of PhD education and training around the world, what Africa needs to adopt is not something organized according to the European model, but one that enables her to drive her development as she is struggling to meet the increased demands that come with her rapid population growth, to map out her expected outcomes and compare them to what she expects her doctoral graduates to know, perform and possess by way of skills, knowledge, values and attitudes (Tremblay et al., 2012; Adu, 2020; Fredua-Kwarteng, 2023). Academic literature (Cloete et al., 2015b; Alemu, 2018; McKenna, 2019) shows that African universities have continuously adopted the traditional or structured model of PhD education and training of the Western world without any modifications or innovation to suit their developmental challenges, this chosen traditional model has proved inadequate to instill in her doctoral graduates the relevant knowledge, skills and values that suffice to drive the much-needed development on the continent. According to Durette et al. (2014), doctoral graduates should possess the competencies to formulate implementable solutions for local and national challenges, read and interpret research findings, take up leadership roles when it comes to confronting development issues. She needs a wide variety of active researchers who are motivated by relevant interventions and recommendations for the advancement of excellence in doctoral education in Africa, such as state-sponsored incentives to produce continent-based solutions geared for African development and many more as shall be discussed henceforth.

Promotion of entrepreneurship

It is essential to encourage entrepreneurship among doctorate students since it can have a positive impact on both individuals and society as a whole. Universities and academic institutions can enable doctorate students to explore cutting-edge concepts, market their research, and launch enterprises that assist economic development and societal advancement by encouraging a culture of entrepreneurship and offering resources and support. Their potential as future leaders, issue solvers, and job creators may be unleashed by encouraging PhD students to think outside of their comfort zones and to adopt an entrepreneurial mindset.

Doctoral graduates are expected to be catalysts for the development of an entrepreneurial ecosystem as well as collaborating with all relevant stakeholders (Mazzarol et al., 2016; Wadee and Padayachee, 2017). To succeed, such a system requires interaction between people and institutions, along with agreed processes which all work together toward creating entrepreneurial ventures. Doctoral graduates, by virtue of their research background, can scout and recognize potential entrepreneurs within their communities and then go on to play the critical roles of conveners and collaborators for such, and thus promote the economic development of their region.

Doctoral students can be given the knowledge, connections, and skills they need to successfully traverse the complicated world of entrepreneurship by providing entrepreneurship-focused courses, mentorship programs, and networking opportunities targeted to their particular study topics. Moreover, giving them access to finance sources and incubator facilities might help them turn their research into successful company initiatives. We can unleash a wealth of creativity and propel positive change in numerous industries and sectors by encouraging and supporting the entrepreneurial goals of doctoral degree students, ultimately adding to a healthy entrepreneurial ecosystem.

To promote entrepreneurial activities, study leaders of doctoral students must provide the best instructional methods, programmes and curricula that are conducive to promoting entrepreneurship, must provide a wealth of information on current and viable entrepreneurial activities in the informal sector and be able to point out real and existent role models that they are involved with, as well as in the business environment. In this way, doctoral research would lead to the development of a vibrant entrepreneurial spirit spearheaded by African doctoral students.

Benchmarking, networking, scholarships and exchange programs

A variety of pursuits designed to promote their academic and professional development are accessible for doctoral students. In order to juxtapose their research efforts, techniques and findings with those of other scientists and the top authorities in their field, benchmarking is an essential part of their journey. Networking is as important for PhD students given that it allows them to connect with other academics, mentors, and business luminaries. These interactions frequently result in partnerships, knowledge exchanges, and promising future employment possibilities.

A student exchange program is one in which students from a higher education study abroad at one of their institution’s partner institutions, and learn in that new environment. The establishing of international scholarships creates opportunities for academic mobility (Beall and Lemmens, 2014); gaining international exposure and experience (Murchison, 2021); foster cross-cultural understanding (Barczyk et al., 2012) and promote academic excellence (Marsh, 2018).

Scholarships are essential for doctorate students’ monetary assistance since they lessen their financial pressure and free them up to concentrate on their research. These scholarships not only offer financial support, but also honor and reward exceptional performance and promise. Exchange programs give students the chance to study or do research in different nations, which improves their PhD experience. These courses expose students to various viewpoints, cutting-edge methodologies, and international networks, generating a genuinely global and invaluable educational experience for a doctorate students.

Scholarships and exchange programs serve a dual purpose in that they can be both a funding as well as a quality assurance mechanism. Aligned with exchange programs, doctoral programs can be developed and compared to ensure that international standards are met and excellence in the production of doctoral students is achieved. Partner non-African institutions should build equitable relationships with their African counterparts; exchanges should be mutually beneficial, with proposals that benefit all stakeholders concerned. In the context of this paper, such scholarships, exchange programs, benchmarking and networking at doctorate level should involve more than collecting and analyzing data and using data to construct theories or make recommendations to solve development challenges. Over and above that, they should offer in-depth insights into identified issues and produce technologies that improve, for example, agricultural productivity, food preservation and affordability, and the general life of the African population. They should facilitate the communication and exchange of ideas, experiences, statistics and learning between universities, research institutes and other stakeholders (Campbell, 2016; Adu, 2020).

Academic support system

To succeed in their research and scholarly endeavors, PhD students need an efficient academic support structure. Such a system includes a number of components that promote and encourage students as they pursue their doctorates. Most importantly, academic advisors or mentorship are essential in imparting direction, knowledge, and honest feedback on research concepts, techniques, and improvements. They act as an authoritative source of information and aid students in traversing the difficulties of their chosen field of study. Additionally, peer support groups and communities give doctorate students a place to connect with their peers, exchange information, share experiences, and provide support to one another. These networks encourage teamwork, friendship, and a sense of community among academics.

To produce doctorate holders, more university-educated lecturers are needed; but in Africa, this has been very slow. Many of Africa’s professors have moved abroad (Adu, 2020), and without senior staff to provide the backbone, this will lead to a lag in the production of researchers and lecturers, and consequently, a lack of locally produced research to drive the doctoral education (Khuluvhe and Netshifhefhe, 2023).

Students can acquire crucial research approaches, methodologies, and writing strategies through workshops, seminars, and training programs. These chances to expand their knowledge and get them ready for the difficulties of PhD study. Doctoral students have access to research facilities, funding sources, databases and libraries, which give them the resources and equipment they need to perform their study successfully. Ultimately, it is crucial to address the distinct difficulties and pressures that doctorate students may experience in order to ensure their general wellbeing. These services include counseling and support groups. Doctoral students are equipped to realize their full potential and make major contributions to their chosen fields of study courtesy to the strong academic support mechanisms that are in place.

The world is a global village, and African higher education needs to be seen to be successfully competing and appearing in international ranking systems, such as the Times Higher Education or World University Rankings. But according to the Times Higher Education [THE] (2020) only a few African universities are found in the top 200: University of Cape Town (ranked 136) and University of Witwatersrand (194), and lately, University of Johannesburg is climbing up the ranks.

Such a scenario means that academics will move away, and students will also choose to study abroad, a situation that will lead to the draining of both brains and fees from Africa (Kweitsu, 2018). Universities need to provide environments suitable for innovation and research, and to make their research more visible by providing excellent academic support systems, such as the development of well-planned mentoring programs; workshops to improve doctoral students’ research and writing skills, assist in the development of research proposals, and writing publishable research. There should also be knowledge production metrics that favorably consider African scholars (Cloete et al., 2015a) (and negate these rankings where only 3 universities on the entire African continent qualify to be among the top 200 in the world), perhaps including their input into groundbreaking reports, international research projects and such highly ranked academic outputs.

Lecturers can be offered refresher workshops, and seasoned professors who have sought further education, research and career opportunities abroad could be incentivized and enticed back by good working conditions so they can increase Africa’s footprint on the doctoral arena.

Industry, national and international collaboration on PhD production

Doctoral students are frequently collaborating together on a variety of projects to advance their research, obtain novel perspectives, and expand their professional connections. These kinds of connections can be divided into three categories: multinational collaborations, national collaborations, and collaborations with particular industries. Here are some specifics about each type:

– International links and connections between academics and doctorate students from various nations include international collaborations. These partnerships might take a variety of forms, encompassing joint research initiatives, arrangements for shared supervision, exchange programs, and participation in international conferences. Through international collaborations, PhD students can collaborate with subject matter experts from other cultural backgrounds and gain access to resources and facilities that aren’t offered at their home university. Additionally, they promote intercultural awareness and broaden opportunities for potential future partnerships and employment prospects.

– National Collaborations: These relationships and alliances between doctorate students and researchers from the same nation are referred to as national collaborations. These partnerships frequently take place between various academic institutions, research centers, or university departments. Doctoral students may cooperate together on research projects, pool resources and knowledge, or take part in workshops and seminars with other students. National collaborations offer chances to make use of shared skills and resources, solve multidisciplinary research problems, and promote cooperation within the national academic community.

– Industry-Linked Collaborations: These partnerships between doctorate students and companies or other commercial entities are known as industry-linked collaborations. These partnerships seek to close the gap between academia and industry by giving doctorate students the chance to get real-world experience, use their research in practical contexts, and participate in initiatives that are pertinent to the sector. Internships, corporate placements, sponsored doctorate research, and joint research and development initiatives are a few examples of industry-related cooperation. These partnerships improve the relevance and effect of doctorate research, give participants access to resources and knowledge from the industry, and raise job opportunities in that field.

Through international, national as well as collaboration with industry, existing problems of funding can be solved, or at least be ameliorated. This will also promote interdisciplinary research (Guzman, 2020). A long-term and sustainable plan would be for the government to increase its collaboration with these stakeholders by developing mutually benefiting plans that will contribute toward the funding of higher education. They may undertake this function by providing grants, bursaries and scholarships on a larger scale to doctoral students.

International collaboration of African doctoral studies is essential for capacity improvement (Bekele, 2022) and should promote opportunities for sustainable research growth on the continent. It is important to guard against indiscriminate replication of educational approaches from high-income countries and universities as this would pose as a barrier to creating novel research and delivering excellent doctoral education on the continent (Cross and Backhouse, 2014). Prior curriculum transformation should be undertaken to provide a framework that particularly defines and guides excellence in African doctoral programmes.

Benefits of Doctoral Student Collaborations includes the following:

– establishing one’s own place in the world of academia.

– exposure to various research approaches, views, and methodologies.

– access to specialized resources, facilities, and equipment.

– broaden the spectrum of study opportunities.

– possibilities for networking with subject-matter specialists.

– enhancing research’s multidisciplinary nature.

– improving research productivity by working together on publications.

– getting opportunities that would never have been available before.

– acquiring new abilities and methods.

– improved professional opportunities and employability.

– expanding viewpoints across cultures and continents.

It’s important to keep in mind that the availability and size of collaborations can change based on the academic discipline, organizational guidelines, and personal research preferences. To make the most of their research journey, doctoral students should look into opportunities and discuss potential partnerships with their supervisors, colleagues, and pertinent institutions or organizations.

Public funding and its contribution toward PhD production

In order to promote the creation of PhDs and advance knowledge in numerous sectors, public support is essential. Public funding provides the facilities, opportunities, and resources required for PhD programs to be completed successfully through investments made by the government in higher education and research. With the help of these funds, universities and research organizations can support aspiring PhD candidates by offering stipends, scholarships, and grants, drawing in and fostering brilliant individuals who might otherwise face obstacles due to lack of funding. Modern research facilities, laboratories, and libraries are also supported by public financing, giving PhD students access to the equipment and resources they need to carry out cutting-edge research.

Higher education is costly in Africa, and investment in research and development (as a share of each country’s GDP) is remarkably low as very few countries meet their goal of 1 per cent of GDP. This means that the cost is cascaded down to students and their families (Marmolejo, 2015; Adu, 2020).

To achieve excellence in this regard, innovative schemes to fund higher education can be tapped into, such as the increasing of government subsidies/grants to universities (Mlambo et al., 2017). PriceWaterhouseCoopers [PwC] (2016), opines that expanding government spending on higher education from its current level to at least 2 percent of GDP will alleviate the weight on students to finance their own education. These Government subsidies to universities can play a huge role in promoting African doctoral education. Loans can also be made available to doctoral students, as an innovative scheme for reducing unequal access to higher education.

The following recommendations can be made when application for public funding to peruse a Doctoral degree:

– Investigate funding organizations: Find out which public funding institutions or groups sponsor PhD students in your subject. Investigate local, regional, and global funding opportunities that fit with your study focus or interests.

– Examine the eligibility requirements for each financing opportunity carefully: Make sure you satisfy the prerequisites for your research subject, citizenship, academic standing, and any other requirements.

– Application deadlines: Be mindful of application deadlines and create a calendar for your applications accordingly. Start working on your application well in advance to give yourself plenty of time to acquire the required paperwork and polish your research idea.

– Effective proposal: Write a strong research proposal that describes the significance, goals, methodology, and potential effects of your study. Explain in detail how your research supports the objectives and priorities of the funding source.

– Recommendation letters/references: Request recommendation letters from respectable, experienced people who can persuasively defend your capacity for research, academic promise, and dedication to your field.

– Updated documentation: Prepare your academic transcripts, curriculum vitae, and any other supporting documentation the funding organization may require. Make sure they are precise, current, and effectively presented.

– Budget and justification: Create a thorough budget that details how the funding will be used, taking into account travel expenses, registration fees for conferences, research costs, and any other necessary outlays. Justify each item to show why it is required.

– Impact and dissemination: Describe how your research may have an impact on the larger scientific community as well as society. Put a focus on how you intend to share research results through papers, talks, or other knowledge-sharing efforts.

– Evaluate and edit: Ask a dependable mentor, advisor, or coworker to evaluate your application materials so they may offer insightful criticism and pointers for development. Make sure your application clearly explains your study objectives and is well-structured and error-free.

– Fulfill specifications: Pay close attention to the funding agency’s instructions. Pay heed to any specific instructions on the submission process, word limits, and formatting specifications.

A Doctoral student in his/her search of public money, keep in mind to be persistent and tenacious. It could be advantageous to look into several funding possibilities at once and to make use of any research alliances or collaborations that already exist to boost your application.

Methodology

The study set to find out the best model of doctorate for Africa and to suggest ways of strengthening the doctoral education landscape in a continent which faces a wide variety of challenges. It is a qualitative review of databases and information on doctoral education in African universities. All doctorate-awarding universities on the continent formed the population.

A literature study was carried out using the desk-top research method. The study used archival data and other critical secondary data sources, such as policy documents, reports and organizational communiques, which were thematically analysed. Various electronic databases were also scanned for published articles. A thematic analysis was employed based on themes presented during a conference session focused on doctoral degrees. After thoroughly reviewing multiple articles, the articles were organized into distinct files corresponding to various themes related to doctoral degrees. Different categories were established to align with the specific themes explored in the study. Subsequently, the articles were systematically categorized within these themes and categories. This process served as the foundation for this manuscript in dissecting the articles and crafting a research paper cantered on the topic of doctoral degrees in Africa. Additionally, the author is actively engaged in the development of a doctoral degree program tailored specifically for the African context.

Sample sources

The population comprised 254 hits of articles that were closely related to the topic as accessed from EBSCOHOST and GOOGLESCHOLAR, but only 50 were very close to the topic under discussion. This therefore became the sample, and they were from the years 2000 to 2023 as the study had to take into consideration the important and historically diverse contexts and experiences of the African countries. Data were reported as accurately as possible in keeping with the research code of ethics (Tripathy, 2013). The study is geographically limited to universities in Africa, and this decision to demarcate the present study as such was taken with due consideration of the theme of the conference: Advancing Excellence in African Higher Education.

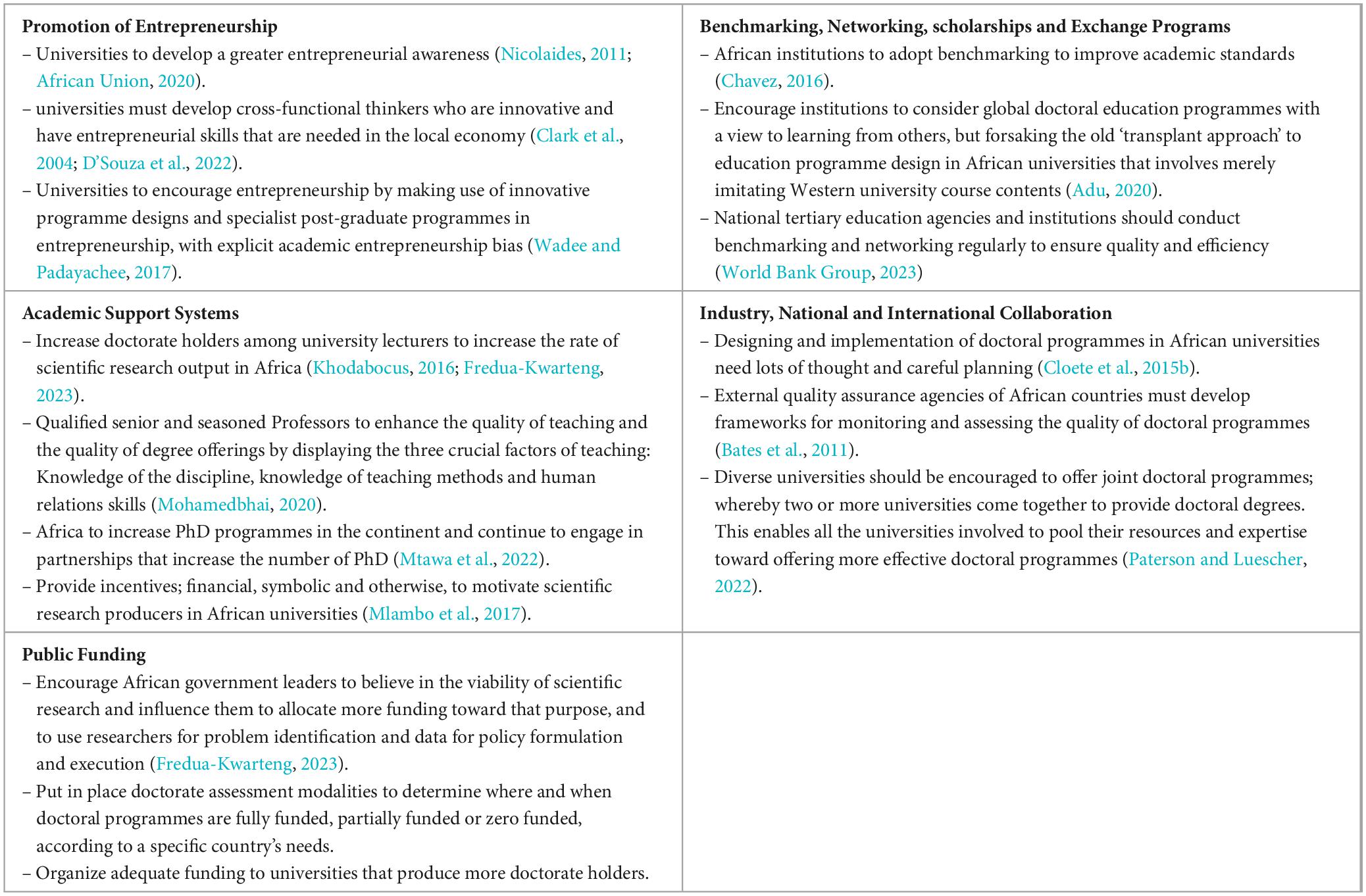

Themes and thematic analysis of direct citations were gleaned from the reviewed literature, policy and other sources and tabulated below is a compilation of the most relevant verbatims on aspirations of the African Doctorate. Table 1 below shows the themes (in bold), and the sub themes are also presented.

Data presentation

Discussion

What follows is a discussion of the interventions on how to strengthen the African doctoral education landscape.

The Theory of Change is the theory guiding this research, and it was developed to assist in understanding and explaining how change takes place and how the interventions lead to desired outcomes and goals (French et al., 2020). In this research, there is need for change in how the African doctorate is prepared and presented, while taking into consideration the interventions tabled above to meet the desired outcomes.

Promotion of entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship can create more jobs on the continent and increase the middle class which is essential in sustaining economic growth (Obonyo, 2016). There is need to change the mindset of our doctoral graduates, to influence them to think as employers by integrating entrepreneurship training in their degree programs. However, despite this realization, African governments seem not to be doing enough as most goods are still being brought in from elsewhere, particularly from China (Hanauer and Morris, 2014). This frustrates any aspiring entrepreneur as s/he does not have access to working capital to make headway and create a niche in the market. Africa’s much needed manufacturing jobs, which are more labor intensive, are therefore not created. The doctorate degree in Africa must be tailor made to encourage entrepreneurship by invoking the use of innovative programme designs and other specialist post-graduate programmes which have explicit academic entrepreneurship bias (Wadee and Padayachee, 2017). African PhDs in Business and Business management must be tailored to exploit the African market, and should encourage trade that is inter-African, for the development of the continent.

Benchmarking, networking, scholarships and exchange programs

In looking up to global doctoral education programmes with a view to learning from them, African institutions must do away with the ‘transplant approach’ to their programme design as this amounts to merely imitating Western university course contents (Adu, 2020), and is not of much use to providing Africa’s needs. What Africa needs right now is urgent job creation for its youth. Many are the PhDs that have been awarded in, for example, in Animal Science. On most African farms, the cattle found there as beef breeds are exotic ones originating from Britain and across Europe; and these are a genetically different population from the African cattle. Of great concern is that the purely African cattle’s unique livestock genetic resources are in danger of rapidly disappearingly due to uncontrolled crossbreeding and breed replacements with exotic breeds (Mwai et al., 2015). While Africa has churned out PhDs in livestock breeding, breeding improvement programs of African indigenous livestock remain dismally too few and yet the demand of livestock products is continually on the rise. Many of the African indigenous breeds are now endangered and their unique adaptive traits may be lost forever (Mwai et al., 2015). Where are the African doctoral graduates in all this (Berg, 2013)? Is the African doctoral qualification educating our graduates to be broad and critical thinkers who are prepared to address current and future scientific challenges such as these?

Academic support systems

Doctoral researchers need to work in a supportive, stimulating and creative environment so that they achieve their set goals. Not only must they obtain the degree, but they need to be supported in various ways so that they become well rounded individuals who can easily make the transition from scholarship to the world of beneficial productivity. There must be free programmes on offer to help them develop both academically and professionally. Doctoral students must be provided with sessions on writing skills, managing data, interviews, how to get their work published and also be exposed to leadership programs as these will effectively prepare them for future engagements (University of Reading, 2023), and to be ready to take up leadership roles when it comes to confronting issues of development.

Partnerships should be forged between universities and employers for the effective grooming of industry-ready graduates and to enable them to embrace industrial training. The universities should revise their curricula to bridge the knowledge gap with industry requirements and conduct regular labor market surveys to improve the curriculum’s relevance so that the graduates do not graduate into a cull de sac.

Industry, national and international collaboration

Designing and implementation of doctoral programmes in African universities need lots of thought and careful planning (Cloete et al., 2015b). Importing wholesale programs from the West will not help Africa in any way. The African doctorate must be a hybrid of Europe, the Americas and then fused with Africa’s needs; the doctorate must consist of bankable projects which create value to Africa, and not just thick essays that sit and gather dust on university library shelves. For example, Africa produces several doctorates in the Engineering field. Africa has lots of mineral wealth, whose exploitation needs tapping into the knowledge gathered from these degrees, but the doctoral engineers are failing the African child who ends up dying in the Mediterranean sea in search of a job in Europe (Al Jazeera Media Network, 2023). There should therefore be collaboration between universities, industry, national as well as regional or international interests. Universities must not produce what the continent cannot make use of or cannot consume. This probably explains why there are so many unemployed graduates in Africa (Jambo, 2022)−a situation that is not worth the ROI, and which is of concern as it poses challenges to policy. The African PhD must be produced for knowledge production, innovation, technology transfer, commercialization and value addition. External quality assurance agencies of African countries must develop frameworks for monitoring and assessing the quality of doctoral programmes (Bates et al., 2011).

Public funding

Doctoral students are funded for them to successfully complete their qualifications and become recognized experts who make distinctive contributions in their fields of study. It is the doctoral qualifications that form a significant part of the funding framework for public higher education institutions. Most African higher education institutions are grossly underfunded, thereby negatively affecting their performance (Armitage et al., 2019). The quality of PhDs produced by any institution impacts heavily on knowledge creation, international comparability, competitiveness, and mobility; on the preparation of future researchers and their research output; and on national capacity to respond appropriately and innovatively, through research, to the various demands of globalization, localization and transformation, in the context of a rapidly changing knowledge economy (Council on Higher Education [CHE], 2022). In this regard, it is of utmost importance to encourage African government leaders to believe in the viability of scientific research and influence them to allocate more funding toward that purpose, and to use researchers for problem identification and data for policy formulation and execution (Fredua-Kwarteng, 2023).

Relevant interventions

African universities should have innovation centers which transform doctoral research theses into tangible artifacts as is happening in some universities such as the Free State which is doing much in terms of indigenous medicine where they have already patented several innovations. The Central University of Technology and a few other universities in the region have also begun to do so, especially in response to the recent COVID 19 pandemic. Secondly, funding is provided just for PhD research. Beyond this there is need for universities to be given funding not just for PhD production, but also as a follow up to the projects covered under these PhDs. The research should be funded in 2 phases: whereby the researcher first produces the thesis, and in the 2nd phase, the researcher and other specialists work on the innovation of the findings of the research study as well as commercialization.

Limitations

The study used secondary data for analysis. The details of the secondary data when it was collected, years it was collected, and timing of collection are a well-known limitation (Miles, 2018). This may have had negative impact on the conclusions drawn from the study.

Conclusion

Current knowledge production as well as research output of African universities are not strong enough to make sustainable contribution to continental development, and yet the call for them is to produce more academics to increase knowledge production. As the knowledge economy grows, so too will jobs emerge that need doctoral education in Africa, and new methods of research will be needed. It is therefore of paramount importance that doctoral students take up programs that are responsive to the needs of the continent and thus strengthen the quality of the human capital so they are prepared to meet and solve the many crises that we are currently experiencing in Africa. The degree of Peace and Governance is widely available in Africa, yet we have so many conflicts on the continent. This needs to change. As regards the engineering doctorate, many doctoral qualifications in all forms of engineering have been produced in African universities, but we still fall far short of the commercialization and innovation that derive from these PhD qualifications. These PhDs in engineering could be solving Africa’s challenges in agriculture, infrastructural development, farming chemicals, seeds and pesticides - which would add value to the agricultural sector in Africa and enable the continent to be food and nutrition sufficient, hence solving a number of challenges experienced thereon. PhD qualifications in Chemistry, Pharmacy and Ethnobotany should result in tangible outputs for innovation and commercialization. This could be in the area of medicines and medicinal plants that could be used to treat health conditions like COVID-19.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

A-MP: Writing–original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Academy of Science of South Africa [ASSAf] (2010). The PhD study: An evidence-based study on how to meet the demands for high-level skills in an emerging economy. Pretoria: ASSAf Publications.

Adu, K. H. (2020). Resources, relevance and impact – Key challenges for African Universities. Uppsala: The Nordic Africa Institute. NAI Policy Notes.

African Union (2020). Promoting youth entrepreneurship in a policy brief – 2020. Bonn: GIZ-German Cooperation.

Al Jazeera Media Network (2023). At least 25 people from sub-Saharan Africa drown off Tunisia. Doha: Al Jazeera Media Network. News report.

Alemu, S. K. (2018). The meaning, idea and history of university/higher education in africa: A brief literature review. Forum Int. Res. Educ. 4, 210–227. doi: 10.32865/fire20184312

Armitage, D., Arends, J., Barlow, N. L., Closs, A., Cloutis, G. A., Cowley, M., et al. (2019). Applying a “theory of change” process to facilitate transdisciplinary sustainability education. Ecol. Soc. 24:20. doi: 10.5751/ES-11121-240320

Barczyk, C. C., Davis, N., and Zimmerman, L. (2012). Fostering academic cooperation and collaboration through the scholarship of teaching and learning: A faculty research abroad program in Poland. Int. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 6, 1–20. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2012.060217

Bates, I., Phillips, R., Martin-Peprah, R., Kibiki, G., Gaye, O., Phiri, K., et al. (2011). Assessing and strengthening African Universities’ capacity for doctoral Programmes. PLoS Med. 8:1001068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001068

Beall, J., and Lemmens, N. (2014). “The rationale for sponsoring students to undertake international study: An assessment of national student mobility scholarship programmes,” in British Council and DAAD German Academic Exchange Service, Edinburgh: Going Global.

Bekele, T. A. (2022). Boosting African doctoral capacity needs national partnerships. London: Times Higher Education.

Campbell, A. C. (2016). International scholarship graduates influencing social and economic development at home: The role of alumni networks in georgia and moldova. Curr. Issues Comp. Educ. 19, 76–91. doi: 10.52214/cice.v19i1.11536

Chavez, D. (2016). Data collection and benchmarking to improve African University Standards. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Clark, W. A., Johnson, K. V., and Turner, C. A. (2004). “Cross-functional student teams as a teaching tool for enhanced learning,” in Proceedings of the 2004 American Society for Engineering. Education Annual Conference and Exposition, Salt Lake City, UT.

Cloete, N., Maasen, P., and Bailey, T. (eds) (2015a). “Knowledge production and contradictory functions in African Higher Education,” in African minds higher education dynamics series (1), Cape Town: African Minds publishers.

Cloete, N., Mouton, J., and Sheppard, C. (2015b). Doctoral Education in South Africa: Policy, Discourse and Data. South Africa: African Minds publishers.

Council on Higher Education [CHE] (2022). National review of South African doctoral qualifications. Brummeria: Council on Higher Education. Doctoral Degrees National Report.

Cross, M., and Backhouse, J. (2014). Evaluating doctoral programmes in Africa: Context and practices. Higher Educ. Policy 27, 155–174. doi: 10.1057/hep.2014.1

D’Souza, D. E., Bement, D., and Cory, K. (2022). Cross-functional integration skills: Are business schools delivering what organizations need? J. Innovat. Educ. 20, 117–130. doi: 10.1111/dsji.12262

Durette, B., Fournier, M., and Lafon, M. (2014). The core competencies of PhDs. Stud. Higher Educ. 41, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2014.968540

Eugste, J., Piazza, R., Jaumotte, F., and Ho, G. (2018). How knowledge spreads. Finance & Development. Washington, DC: IMF.

Fredua-Kwarteng, E. (2023). Africa needs more PhDs, but they must be of high quality. London: University World News. Available online at: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20180306124842675 (assessed May 19, 2023).

French, J., Bachour, R., and Mohtar, R. (2020). Theory of change for transforming higher education. Beirut: American University of Beirut.

Hanauer, L., and Morris, L. J. (2014). China in Africa: Implications of a deepening relationship. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Cooperation.

Jambo (2022). Demystifying Africa #4: Reasons behind unemployment among graduates. Lucknow: Jambo Technology.

James, C. (2011). Theory of change review. Report commissioned for Comic Relief. London: Comic Relief.

Khodabocus, F. (2016). Challenges to doctoral education in Africa. International Higher Education. Available online at: https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/ihe/article/view/9246 (accessed May 24, 2023).

Khuluvhe, M., and Netshifhefhe, E. (2023). Are we producing enough doctoral graduates in our universities?. Pretoria: Factsheet.

Marmolejo, F. (2015). The great challenge in tertiary education: Is it really just about the fees? Education for Global Development. London: World Bank.

Marsh, R. (2018). Can international scholarships lead to social change? University World News. Can international scholarships lead to social change?. Available online at: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20180130135416862 (accessed May 15, 2023).

Mazzarol, T., Battisti, M., and Clark, D. (2016). “The role of universities as catalysts within entrepreneurial ecosystems,” in Book: Rhetoric and reality: Building vibrant and sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems, eds D. Clark, T. McKeown, and M. Battisti (Prahran, VIC: Tilde University Press). doi: 10.1177/20552076231173303

McKenna, S. (2019). The model of PhD study at South African universities needs to change. Johannesburg 05, 97–112.

Miles, J. (2018). Teaching history for truth and reconciliation: The challenges and opportunities of narrativity, temporality, and identity. McGill J. Educ. 53, 291–311. doi: 10.7202/1058399ar

Mlambo, H. V., Hlongwa, M., and Mubecua, M. (2017). The provision of free higher education in South Africa: A proper concept or a parable? J. Educ. Vocati. Res. 8, 51–61. doi: 10.22610/jevr.v8i4.2160

Mohamedbhai, G. (2020). SA’s PhD review: Its relevance for other countries in Africa. London: University World News.

Mtawa, N., Wildschut, A., and Fongwa, S. (2022). Towards developing a Collaborative PhD Program across ARUA Member Universities. Experiences from the University of Rwanda, Rwanda. A Research Report Produced for ARUA by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC)*.

Murchison, C. (2021). Why global experience should be a college requirement. Portland, OR: GO OVERSEAS.

Mwai, O., Hanotte, O., Kwon, Y.-J., and Cho, S. (2015). African indigenous cattle: Unique genetic resources in a rapidly changing world. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 28, 911–921. doi: 10.5713/ajas.15.0002R

Nicolaides, A. (2011). Entrepreneurship- the role of Higher Education in South Africa. Educ. Res. 2, 1043–1050.

Obonyo, R. (2016). Africa looks to its entrepreneurs. Available online at: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/april-2016/africa-looks-its-entrepreneurs#:~:text=%E2%80%9CEntrepreneurship%2C%20if%20well%20managed%2C (accessed May 29, 2023).

Paterson, M., and Luescher, T. M. (2022). The future of African higher education is in its diversity. London: University World News.

PriceWaterhouseCoopers [PwC] (2016). Funding of public higher education institutions in South Africa. Available online at: https://www.pwc.co.za/en/publications/funding-public-higher-education-institutions-sa.html (accessed May 29, 2023).

Sawyerr, A. (2004). Challenges facing African Universities: Selected Issues. Afr. Stud. Rev. 47, 1–59. doi: 10.1017/S0002020600026986

Taplin, D., and Clark, H. (2012). Theory of change basics: A primer on theory of change. New York, NY: ActKnowledge, Inc.

Teferra, D. (2015). Manufacturing - and Exporting - Excellence and ‘Mediocrity’: Doctoral education in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Higher Educ. 29, 8–19.

Times Higher Education [THE] (2020). World university rankings 2022. Available online at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2022/world-ranking (accessed May 28, 2023).

Tremblay, K., Lalancette, D., and Roseveare, D. (2012). Assessment of higher education learning outcomes. Paris: OECD.

Tripathy, J. P. (2013). Secondary data analysis: Ethical issues and challenges. Iran J. Public Health. 42, 1478–1479.

UNESCO Science Report (2021). The race against time for smarter development; Executive summary. Paris: UNESDOC.

United Nations (2023). United Nations Graduate Study Programme 2023 for Studies. Switzerland. Available online at: https://studygreen.info/unitednations-graduate-study-programme-for-studies-in-switzerland/ (accessed May 12, 2023).

University of Reading (2023). How we support PhD students. Available online at: https://www.reading.ac.uk/art/phd/how-we-support-phd-students (accessed May 29, 2023).

Valters, C. (2015). Theories of change: Time for a radical approach to learning in development. London: Overseas Development Institute.

Wadee, A. A., and Padayachee, A. (2017). Higher education: Catalysts for the development of an entrepreneurial ecosystem, or …Are we the weakest link? Scie. Technol. Soc. 22, 284–309. doi: 10.1177/0971721817702290

Wangenge-Ouma, G., and Kupe, T. (2020). Uncertain times: Re-imagining universities for new, sustainable futures. London: Universities South Africa.

Waruru, M. (2022). Project seen as ‘great achievement’ for HE in Africa. London: University World News Africa Edition.

World Bank Group (2023). Data collection and benchmarking to improve African University Standards. Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2016/08/03/data-collection-and-benchmarking-to-improve-african-university-standards (accessed May 29, 2023).

Keywords: academic support systems, entrepreneurship, interdisciplinary research, international partnership, quality assurance, technological infrastructure

Citation: Pelser A-M (2024) Synergistic advancements: fostering collaborative excellence in doctoral education. Front. Educ. 8:1289424. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1289424

Received: 05 September 2023; Accepted: 11 December 2023;

Published: 05 January 2024.

Edited by:

Sergio Andrés Cabello, University of La Rioja, SpainReviewed by:

Mariana Alonso, University of Malaga, SpainAinara Ruiz-Sancho, University of Valencia, Spain

Copyright © 2024 Pelser. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anna-Marie Pelser, YW5uYS5wZWxzZXJAbnd1LmFjLnph; YW1wZWxzZXJAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=; orcid.org/0000-0001-8401-3893

Anna-Marie Pelser

Anna-Marie Pelser