- 1Department of Family Science and Social Work, Miami University, Oxford, OH, United States

- 2Department of Social Work, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, United States

Career readiness of college graduates is of critical importance in higher education. As defined by the career readiness is the attainment and demonstration of requisite competencies that broadly prepare college graduates for successful transition into the workplace and/or graduate school. This article outlines the development of a sophomore-level course – Critical Thinking and Writing for Social Work Professionals – as part of a Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) program at Ball State University. The primary purpose of this course is to help students develop career readiness competencies that support their growth throughout their educational and professional social work careers. The career readiness competencies support the Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards required by the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE). The authors discuss the importance of this approach for undergraduate education and how career readiness enhances and builds upon CSWE competencies. The authors conclude with a brief discussion of student feedback and lessons learned through this process that suggests students’ gained career readiness skills.

Introduction

The National Association of Colleges and Employers (2023) is a professional association that connects nearly 17,000 college career service professionals, university leaders, and industry professionals together. The organization is the leading source of information on the employment of the college educated, and forecasts hiring trends in the job market. One area of specific focus for the association is the development of career readiness competencies within the higher education classroom. These competencies can provide a foundation from which students can demonstrate requisite skills for workplace success and lifelong career management (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2021). National Association of Colleges and Employers (2021) delineates eight career readiness competencies defined as professionalism, communication, career and self-development, critical thinking, teamwork, equity and inclusion, leadership, and technology. For social work students, in conjunction with CSWE competencies, career readiness competencies also promote their successful entrance into the workforce and/or graduate school programs (Levin et al., 2018; McSweeney and Williams, 2019). In the college classroom, these competencies provide a framework to ensure career-related goals and outcomes are addressed in curricular and extracurricular activities (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2021). As such, social work graduates become prepared to transform their higher learning activities into key skills that employers or graduate schools recognize as assets. These career readiness competencies also allow educational programs to track performance metrics (graduation and persistence rates, time to degree matriculation, graduate school acceptance, and job placement) and train students transformative skills such as regulation, listening, resilience, bias recognition, and problem-solving that contribute to performative outcomes (Bresciani, 2019).

These career readiness objectives are not a replacement for CSWE competencies; rather, they support the strong history of social work education in preparing students for practice (Bowie and McLane-Davison, 2021). Research studies demonstrate the effectiveness of CSWE competencies in preparing entry-level social workers (Levin et al., 2018; McSweeney and Williams, 2019). The NACE competencies are another tool social work educators can use in navigating a complex social work curriculum. The Department of Social Work at Ball State University observed value and crossover in incorporating both the NACE and CSWE competencies in a field-specific, sophomore-level course to prepare students for the needs of the workforce, and this article outlines the development of this new course – Critical Thinking and Writing for Social Work Professionals – as part of our Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) program. The authors believe the crossover between CSWE and NACE competencies to be a value add to social work courses. The NACE competencies reinforce the practice and professional skills required of entry-level social work practitioners.

The role of NACE competencies in supporting CSWE competencies

Our department developed a new 200-level course with a focus on NACE career readiness competencies based on student data from annual reports, course evaluations, and implicit curriculum surveys, as well as faculty observations of gaps and challenges in our undergraduate educational setting. Our undergraduate student population is greater than 50% first-generation students. Early efforts to support first-year and sophomore level students in their transition to education and career preparedness show positive results for long-term educational and career success (Knotek et al., 2019; Lopez Vergara, 2022). While our program decided to create a new course at the 200-level, it is also possible to integrate career readiness competencies into existing courses, and additional faculty members are integrating these competencies at the 300- and 400-levels. These courses build off of the foundation established in the 200-level course and allows for students to further practice NACE competencies in conjunction with CSWE competencies as students progress throughout the program. This includes the ability to translate NACE competencies in field practicum, where students are consistently working to define their professional self. This also includes select integration of NACE competencies that align more closely with micro- versus macro-based concepts and those that best align with community agencies during practicum placements. Below is a summary of the eight NACE career readiness competencies and how they can facilitate activities that promote the strengths of current CSWE competencies. The authors believe many of these competencies are present in multiple if not all social work courses.

Competency one: professionalism

Many social work students are not prepared for the transition from student to qualified practitioner, which suggests a possible gap in preparation for practice during coursework (Moorhead, 2019). Students in our program shared a desire for more coursework dedicated to the development of their professional identity as a way to cultivate skills to improve their transition to entry-level social work employment and/or graduate school admission (Cleak, 2019). Concepts covered in the course include the following: (1) information about potential careers in social work, (2) salary expectations based on career path and fringe benefits, (3) student loan debt repayment, (4) advanced education options, (5) licensing expectations, and (6) affiliations with professional associations such as the National Association of Social Workers (NASW).

Competency two: communication

Our department observed some undergraduate students lacked the skills and/or confidence to communicate clearly in a professional manner and setting. Indeed, improving the information literacy and writing skills of undergraduate social work students who arrive in our programs with varied abilities and backgrounds in communication skills continue to be a challenge for many educators (Alter and Adkins, 2001; Granruth and Pashkova-Balkenhol, 2018). Our department also understands the complexity of communication as it relates to oral communication, body language, influence of the environment, cultural responsiveness, etc. Topics discussed in the course include the following: (1) organization and structure of written materials, (2) grammar usage, (3) mechanics of APA, (4) preparing oral presentations, (5) creating professional PowerPoints, and (6) email etiquette.

Competency three: career and self-development

Social workers should continually strive toward self-awareness of their professional development needs and strengths. They should only practice within their areas of professional competence and aspire to contribute to the clinical and evidence-informed knowledge base of the profession (National Association of Social Workers, 2021). Yet, many students lack confidence in their preparedness for entry-level practice in various settings and/or graduate school admission (Moorhead et al., 2019). Topics to cover this competency include the following: (1) articulating and promoting personal skills and experiences, (2) building a resume and cover letter, (3) defining career goals, (4) preparing for interviews, and (5) negotiating a salary.

Competency four: critical thinking

Social work educators cannot assume critical thinking skills are central to practice proficiencies, so they are always incorporated into the learning process (Sheppard and Charles, 2017). Critical thinking requires students to reflect on problems, issues, and situations with clarity, accuracy, precision, relevance, depth, breadth, logic, and fairness (Paul and Edler, 2006). This approach encourages students to become reflexive in their education and ultimately their practice (Lay and McGuire, 2010). To meet this competency, the following content is included in the course: (1) multiple models of critical thinking, (2) analysis of the NASW Code of Ethics, (3) management of ethical dilemmas, and (4) self-exploration strategies related to personal values and beliefs.

Competency five: teamwork

Council on Social Work Education (2023) maintains a commitment to advancing interprofessional education and teamwork to improve well-being for populations worldwide. Social workers strive to deliver high quality services within their scope of practice, with respect for the expertise of other members and disciplines that make up intervention and treatment teams (World Health Professions Alliance, 2021). As such, the course covers the following concepts: (1) competencies of interprofessional education and practice, (2) accountability to colleagues, and (3) the power of networking.

Competency six: equity and inclusion

Social work programs have a responsibility to train students to navigate and manage the influence of bias, power, privilege, and oppression when working with clients and communities. However, not all students feel prepared to employ anti-oppressive practices or lead initiatives for diversity, equity, inclusion, justice, and belonging in organizational settings (Cano, 2020). To address this competency, the course presents the following: (1) strategies for promoting inclusive excellence, (2) strategies for critical self-reflection, (3) international social work perspectives, and (4) advocacy skills to confront social, economic, racial, and environmental injustices.

Competency seven: leadership

Social workers are regularly promoted to management from direct service positions without adequate skills and training from their undergraduate programs (Peters, 2018; Vito and Hanbidge, 2021). Topics of discussion include the following: (1) various leadership styles and inventories, (2) strategies for leveraging the strengths of others, (3) embracing feedback form others, and (4) organizing and prioritizing tasks.

Competency eight: technology

A gap exists between the level of digital skills required in the labor market and the actual level of digital skills of social work students (Boddy and Dominelli, 2017; Reamer, 2019; López Peláez et al., 2020). This course illustrates the power of digital technology and reviews the ethical use of technology.

Development of a course with NACE competencies

The development of this course was the outcome of a professional development experience termed the “Skills Infusion Program” (Ball State University, 2021). This program took place over the course of one semester via a series of three-large group, required workshops. The workshops included faculty members from diverse disciplines across the university and focused on developing a new course (or modifying an existing course), mapping course outcomes to the NACE competencies (connecting NACE competencies to CSWE competencies), and creating a syllabus that received extensive and ongoing input from the University Career Center and Indiana employer/alumni partners. The employer/alumni network consisted of several individuals from human service agencies that played an integral role in connecting NACE and CSWE competencies in a manner that elevated their effectiveness. Each faculty member was also paired with an assigned faculty fellow who had previously completed the program. The fellow was a consistent voice of support and coordinated, led, and completed individual meetings with faculty members.

Both the University Career Center and the employer/alumni network strongly supported the inclusion of the NACE competencies into either new or existing courses. While the University Career Center is able to provide support to students on a variety of topics, the center needs help from academic programs to help students better articulate transferable skills learned in concert with course content. Moreover, the University Career Center provides a gap analysis that students can use to reflect on skills not yet practiced or learned. This new social work course aimed to provide clear connections to how the skills taught in the classroom transcend colleges and span industries.

Overview of a NACE competency social work course

While all eight National Association of Colleges and Employers (2021) competencies are critical to the development of workforce- and/or graduate school readiness, the course developed listed the competencies in a hierarchical fashion based on the specific needs of the student body and the program’s regional workforce. Our department also was able to place additional emphasis on the NACE competencies that best support the CSWE competencies that tend to have lower scores in our annual assessment report. With the NACE competencies, educators are able to tailor course assignments related to the CSWE competencies based on the identified needs of students. Examples of assignments include a professionalism contract, ethical principle screen worksheet, annotated bibliography with PowerPoint, attendance at interprofessional education and practice events, attendance at a cultural event related to social injustice, social media campaign, cover letter and resume, and mock job interview.

Course description

Career readiness of college graduates is of critical importance in higher education. Career readiness is the attainment and demonstration of requisite competencies that broadly prepare college graduates for successful transition into the workplace. The primary purpose of this course is to help students develop career readiness competencies that will support their growth throughout their educational and professional social work careers. This course places an emphasis on developing eight career readiness competencies that will prepare social work majors with requisite skills and knowledge. These competencies include: professionalism, communication, career- and self-development, critical thinking, teamwork, equity and inclusion, leadership, and technology.

Course objectives

1. Students will demonstrate personal accountability and effective work habits in the classroom setting (Professionalism).

2. Students will articulate thoughts and ideas clearly, concisely, and effectively in written and oral forms to persons inside and outside of the social work program (Communication).

3. Students will identify one’s strengths, knowledge, and experiences relevant to desired positions and career goals, and identify areas necessary for professional growth (Career- and Self-Development).

4. Students will exercise sound reasoning to analyze issues, make decisions, and overcome problems (Critical Thinking).

5. Students will build collaborative relationships with social work colleagues and individuals from other professions who represent diverse viewpoints (Teamwork).

6. Students will exhibit openness, inclusiveness, sensitivity, and the ability to interact respectfully with all people and differences (Equity and Inclusion).

7. Students will leverage strengths of others to achieve common course goals (Leadership).

8. Students will leverage existing digital technologies ethically and efficiently to solve problems, complete tasks, and accomplish goals (Technology).

Weekly course breakdown

1. Week 1: professionalism (Introduction to NACE Competencies and Connection with Social Work Profession, Personal Accountability for Learning, Effective Work Habits in the Classroom, Defining Professional Behavior).

2. Week 2: critical Thinking (Paul-Edler Critical Thinking Model, University of Leeds Model of Critical Thinking, Critical Thinking in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

3. Week 3: critical Thinking (NASW Code of Ethics, Ethical Principle Screen, Self-Exploration with Personal Values, Using Critical Thinking within Decision-Making).

4. Week 4: communication (Concise and Effective Writing, Outlining and Planning for the Writing Process, Organization and Structure of Writing, Reducing Bias in Language, Grammar Usage).

5. Week 5: communication (Mechanics of APA).

6. Week 6: Communication (Preparing Oral Presentations, Creating a PowerPoint, Writing for Professional Growth, Proofreading Basics, Email Etiquette).

7. Week 7: teamwork (Interprofessional Education and Practice, Collaborative Work, Multidisciplinary Teams).

8. Week 8: teamwork (Accountability to Colleagues, Teamwork and Critical Thinking, negotiating and Managing Conflicts, Networking).

9. Week 9: technology (Digital Technology, Technology Ethics, Emerging Technology).

10. Week 10: leadership (Leadership Styles, Leveraging Strengths, Offering and Responding to Feedback, Managing Emotions, Organizing and Prioritizing Tasks).

11. Week 11: career- and Self-Development (Identifying and Articulating Strengths, Identifying Areas for Professional Growth, Functionalizing Current Activities, Defining Career Goals).

12. Week 12: career- and Self-Development (Preparing for an Interview, Participating in an Interview, Follow-Up Emails, Self-Advocacy, and Negotiating Salary).

13. Week 13: career- and Self-Development (Self-Care, Time Management, and Stress Management).

14. Week 14: equity and Inclusion (Diversity Panel, Anti-Oppressive Practices, Intercultural Fluency, International Perspectives).

Student feedback

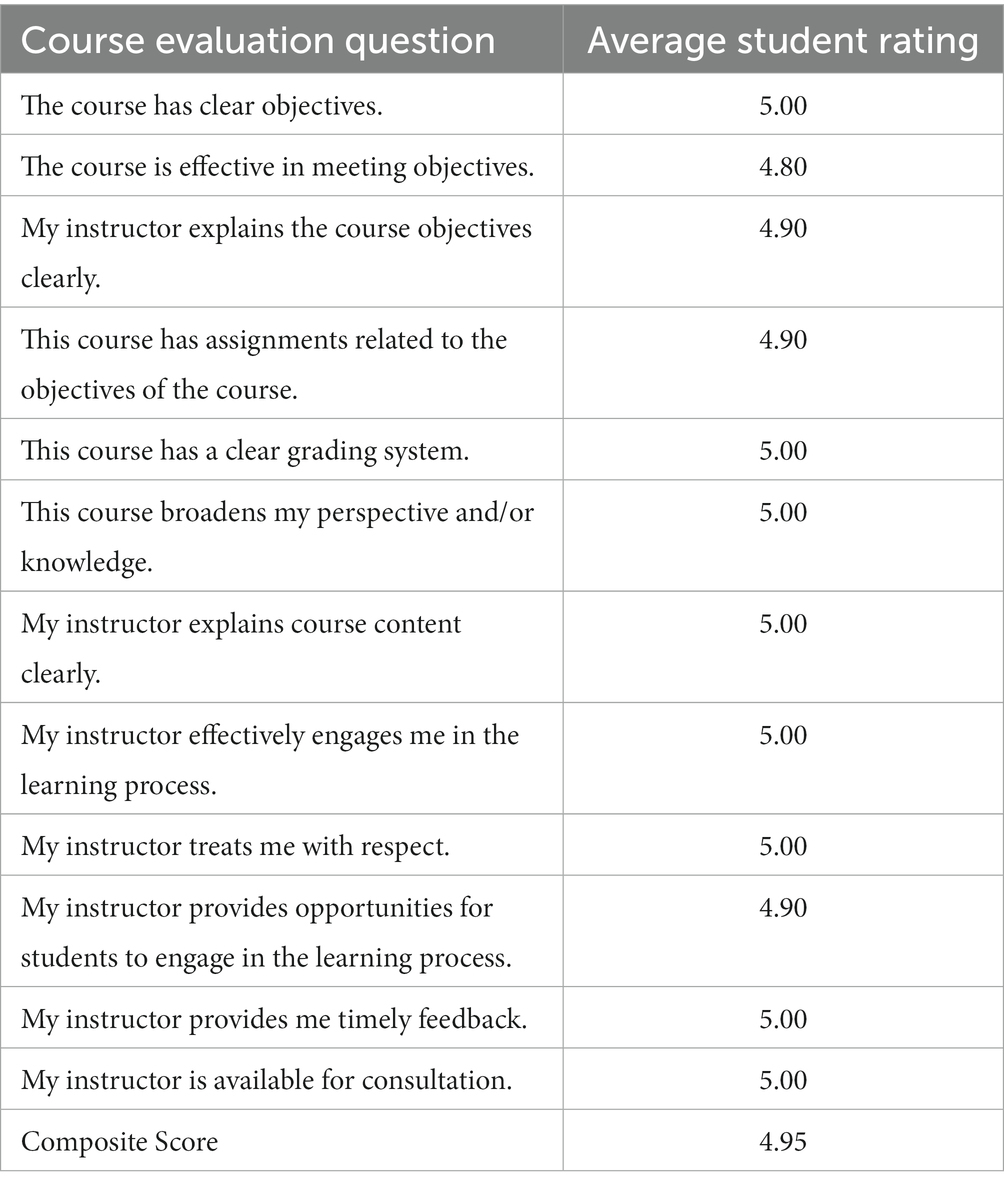

Seventy students completed this newly required course. Student feedback on overall course effectiveness averaged a 4.95 on a 5.0 scale (see Table 1). Sample questions asked included the following: (1) Does the course have clear objectives? (2) Is the course effective in meeting the objectives? (3) Does the course have assignments related to the objectives of the course? (4) Does the course broaden your perspective and/or knowledge? Student qualitative feedback consistently showed students (1) learned materials that will help them throughout their social work program and career, (2) believed faculty members mentored the NACE competencies in their interactions with students, and (3) developed resources that will put them further ahead in their professional development (e.g., cover letter, resume, and mock interview). As it relates specifically to career readiness, students reported they were able to use the NACE competencies in their required volunteer experiences and have subsequently used their skills in the practicum planning process. Volunteer experiences and practicum experiences are key CSWE assessment measures for our department.

Discussion

The inclusion of the NACE competencies into social work course curriculum largely emphasizes CSWE’s competency of Demonstrating Ethical and Professional Behavior (Council on Social Work Education, 2022), while organizing various aspects of this competency into clearly demarcated career readiness standards that attempt to meet the needs of an ever-shifting workforce. As underscored by the Equity and Inclusion NACE competency and the Engaging with Diversity and Difference in Practice competency from CSWE, culture plays an important role in how organizations, employees, and their clients interact and engage with one another. While there is considerable emphasis placed on professionalism in this course, it is essential that classroom discussions around professional standards are nuanced, taking into account differences in cultural norms and expectations. Students are taught to be mindful of how their professional performance is evaluated and often connected to leadership expectations, and they are also encouraged to challenge White/Western standards based in affinity bias in those workplaces. Similarly in professional practice, social workers should gain skills to assess for and apply specific standards of professionalism within the context of their employers and populations that they serve.

In consideration of lessons learned from the development of this course, there may be value in scaffolding these competencies across multi-levels of social work education (introductory, bachelors, masters, and doctoral). For example, since the creation of this sophomore-level class, the BSW program has started implementing these competencies into junior- and senior-level courses with further expansion into the MSW program as a possibility. Programs who wish to include this type of course or the NACE competencies in their curriculum ought to adapt and emphasize the assignments to match the specific professional development needs of their student body with the hiring needs of organizations in their catchment area.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ball State University - Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MM: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. JT: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alter, C., and Adkins, C. (2001). Improving the writing skills of social work students. J. Soc. Work. Educ. 37, 493–505. doi: 10.1080/10437797.2001.10779070

Ball State University (2021). Skills infusion program. Available at: https://www.bsu.edu/about/administrativeoffices/careercenter/programs-services/skills-infusion-program (Accessed October 15, 2023).

Boddy, J., and Dominelli, L. (2017). Social media and social work: the challenges of a new ethical space. Aust. Soc. Work. 70, 172–184. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2016.1224907

Bowie, S. L., and McLane-Davison, D. R. (2021). Readiness for graduate social work education: does an undergraduate social work major make a difference? J. Teach. Soc. Work. 41, 360–372. doi: 10.1080/08841233.2021.1947440

Bresciani, M. L. (2019). Looking below the surface to close achievement gaps and improve career readiness skills. Change 51, 34–44. doi: 10.1080/00091383.2019.1674106

Cano, M. (2020). Diversity and inclusion in social service organizations: implications for community partnerships and social work education. J. Soc. Work. Educ. 56, 105–114. doi: 10.1080/10437797.2019.1656577

Cleak, H. (2019). Holistic approach to curriculum development to promote student engagement, professionalism, and resilience. Aust. Soc. Work. 72, 248–250. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2018.1559337

Council on Social Work Education (2023). Advancing interpersonal education. Available at: https://www.cswe.org/Centers-Initiatives/Initiatives/Advancing-Interprofessional-Education (Accessed October 15, 2023).

Council on Social Work Education (2022). Education policy and accreditation standards. https://www.cswe.org/accreditation/standards/2022/.

Granruth, L. B., and Pashkova-Balkenhol, T. (2018). The benefits of improved information literacy skills on student writing skills: developing a collaborative teaching model with research librarians in undergraduate social work education. J. Teach. Soc. Work. 38, 453–469. doi: 10.1080/08841233.2018.1527427

Knotek, S. E., Fleming, P., Wright Thompson, L., Fornaris Rouch, E., Senior, M., and Martinez, R. (2019). An implementation coaching framework to support a career and university readiness program for underserved first-year college students. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 29, 337–367. doi: 10.1080/10474412.2018.1544903

Lay, K., and McGuire, L. (2010). Building a lens for critical reflection and reflexivity in social work education. Soc. Work. Educ. 29, 539–550. doi: 10.1080/02615470903159125

Levin, S., Fulginiti, A., and Moore, B. (2018). The perceived effectiveness of online social work education: insights from a national survey of social work educators. Soc. Work. Educ. 37, 775–789. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2018.1482864

López Peláez, A., Erro-Garcés, A., and Gomez-Ciriano, E. J. (2020). Young people, social workers and social work education: the role of digital skills. Soc. Work. Educ. 39, 825–842. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2020.1795110

Lopez Vergara, C. C. (2022). Creating a competitive advantage for a successful career trajectory. J. Multidiscip. Res. 14, 77–84.

McSweeney, F., and Williams, D. (2019). Social care graduates’ judgements of their readiness and preparedness for practice. Soc. Work. Educ. 38, 359–376. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2018.1521792

Moorhead, B. (2019). Transition and adjustment to professional identity as a newly qualified social worker. Aust. Soc. Work. 72, 206–218. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2018.1558271

Moorhead, B., Bell, K., Jones-Mutton, T., Boetto, H., and Bailey, R. (2019). Preparation for practice: embedding the development of professional identity within social work curriculum. Soc. Work. Educ. 38, 983–995. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2019.1595570

National Association of Colleges and Employers (2021). What is career readiness? Available at: https://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/career-readiness-defined/ (Accessed October 15, 2023).

National Association of Colleges and Employers (2023). About us. Available at: https://www.naceweb.org/about-us/ (Accessed October 15, 2023).

National Association of Social Workers (2021). Code of ethics. Available at: https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English (Accessed October 15, 2023).

Paul, R., and Edler, L. (2006). Critical thinking: Tools for taking charge of your learning and your life. Hoboken, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Peters, S. C. (2018). Defining social work leadership: a theoretical and conceptual review and analysis. J. Soc. Work. Pract. 32, 31–44. doi: 10.1080/02650533.2017.1300877

Reamer, F. G. (2019). Social work education in a digital world: technology standards for education and practice. J. Soc. Work. Educ. 55, 420–432. doi: 10.1080/10437797.2019.1567412

Sheppard, M., and Charles, M. (2017). A longitudinal comparative study of the impact of experience of social work education on interpersonal and critical thinking capabilities. Soc. Work. Educ. 36, 745–757. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2017.1355968

Vito, R., and Hanbidge, A. S. (2021). Teaching social work leadership and supervision: lessons learned from on-campus and online formats. J. Soc. Work. Educ. 57, 149–161. doi: 10.1080/10437797.2021.1932650

World Health Professions Alliance (2021). Interprofessional collaborative practice. Available at: https://www.whpa.org/activities/interprofessional-collaborative-practice (Accessed October 15, 2023).

Keywords: career readiness, social work education, competency-based education, higher education, student outcome

Citation: Moore M and Thaller J (2023) Career readiness: preparing social work students for entry into the workforce. Front. Educ. 8:1280581. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1280581

Edited by:

Antonio P. Gutierrez de Blume, Georgia Southern University, United StatesReviewed by:

Oğuzhan Zengin, Karabük University, TürkiyeCopyright © 2023 Moore and Thaller. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matt Moore, bW9vcmVtMjhAbWlhbWlvaC5lZHU=; Jonel Thaller, anRoYWxsZXJAYnN1LmVkdQ==

Matt Moore

Matt Moore Jonel Thaller2*

Jonel Thaller2*