- Karaganda Buketov University, Department of Kazakh Literature, Karaganda, Kazakhstan

This paper explores the use of coaching and mentoring methods in teaching literature to secondary school students. This innovative pedagogical approach has not been previously practiced in Kazakhstani schools. The study employs a one-month coaching and mentoring initiative tailored for secondary school students. This qualitative study employed the collection of the reflective journal “life scenario” and the focus group interview with participants. The data obtained from the reflective journal and focus group interview were subjected to content analysis. The integration of coaching and mentoring methods into literature pedagogy is postulated as a catalyst for inspiring students to develop “life scenarios,” thereby propelling them towards goal achievement and academic success. Additionally, the paper suggests integrating more practical exercises from business, psychology, coaching, and mentoring in literature lessons at the secondary school level.

Introduction

The Ministry of Education and Science of Kazakhstan implemented a new curriculum reform in all mainstream schools starting from the 2016–2017 academic year. The primary objective of this reform was to establish a bridge between school education and real-life application, with a particular emphasis on developing students’ functional literacy and critical thinking skills (National Academy of Education named after Altynsarin, 2020). As a secondary school teacher during this period, I gained valuable insights into the engaging nature of the reform and the emergence of new perspectives in the teaching process. Given the tendency of individuals to rely on their backgrounds and experiences, this paper aims to analyze the benefits and challenges of integrating coaching and mentoring into literature teaching from the perspective of a literature teacher.

Coaching and mentoring are longstanding concepts in Kazakhstani education, originally employed during the Soviet period. The terms “nastavnichevstvo” and “shevstvo” within the USSR’s education system focused on the socialization and support of newly qualified teachers, encompassing the principles of guiding, supporting, coaching, and mentoring (Kadyrova, 2017). However, until the recent curriculum reform, coaching and mentoring practices for young teachers in Kazakhstani schools were not as prevalent as during the Soviet era. The understanding of coaching and mentoring in Kazakhstani education primarily revolved around adults, such as teachers and managers. Even a recent study by Sarmurzin et al. (2022), which recommends the establishment of a specialized mentorship program to support young school leaders, primarily explores mentoring for professionals. Notably, no studies have been conducted on coaching and mentoring school students. Therefore, the primary objective of this paper is to conduct an in-depth analysis of the potential applications of coaching and mentoring methods in the teaching literature to secondary school students. Furthermore, the study endeavors to elucidate the various advantages and disadvantages that may manifest within the context of literature instruction. The unique perspective of considering coaching and mentoring in the context of literature education enhances the novelty and significance of the study.

Literature review

Coaching and mentoring in an educational context

The poem “The Odyssey” by Homer serves as an ancient example that illustrates coaching and mentoring practices. In the story, Mentor takes care of Telemachus while his father, Ulysses, is engaged in the Trojan Wars (Roberts and Chernopiskaya, 1999; Satchwell, 2006). The term “mentor” originates from the noun “mentos,” which encompasses the meanings of intent, purpose, spirit, and passion (Etymology Online, 2023). Coaching is widely recognized for its valuable role in supporting students’ emotional and social development (Van Nieuwerburgh, 2012), facilitating change, enhancing performance, effectiveness, and success (Connor and Pokora, 2007, pp. 56–68), and demonstrating an evolutionary nature (Lofthouse et al., 2010, p. 8). Conversely, mentoring involves a more experienced individual providing sponsorship, teaching, counseling, and encouragement to someone with less experience (Anderson and Shannon, 1988). According to Kochan (2013), mentoring has the potential to bring about powerful and transformative changes in organizations, people’s lives, and societies. Mentors also provide support for research development, professional growth, and psychosocial well-being (Abedin et al., 2012), and they serve as “career guides,” “friends,” “intellectual guides,” and “sources of information” for mentees (Sands et al., 1991). Moreover, mentoring helps mentees to focus on the progress and the learning process (Alred and Garvey, 2000), guide and support students from different perspectives: reducing alcohol and drug use, decreasing absences from school (Jekielek et al., 2002), maintains emotional and social development of students (Van Nieuwerburgh, 2012), and helps to establish a good relationship with parents (Satchwell, 2006). Additionally, mentoring can contribute to positive changes in students’ academic outcomes, including improved academic achievement, motivation, homework completion, self-confidence, and concentration on studies (Lay, 2017).

Both coaching and mentoring aim to motivate students for goal achievement, change, growth, improved performance, and facilitated learning (Lofthouse et al., 2010, pp. 7–8). They have the potential to enhance students’ motivation for learning. However, there are distinctions between coaching and mentoring. Coaching involves engaging in a dialogue with the client to define problems (Armstrong, 2012) and typically entails a longer process compared to mentoring, which can be either long-lasting or short-term (Connor and Pokora, 2007, pp. 45–63; Koroleva, 2017). Considering the context of Kazakh literature, where time is limited due to the constraints of the school program and the Ministry of Education’s prescribed calendar, implementing short-term coaching methods within a single lesson (lasting 40 min) may be more practical. On the other hand, coaching may be better suited for classroom tutors who assume responsibility for the motivation, development, and psychological well-being of an entire group of students while working closely with parents and subject teachers. Even though coaching and mentoring have some differences, they share common characteristics (Fletcher and Mullen, 2012; Van Nieuwerburgh, 2012). This fact encourages us to contemplate them together in this study.

According to Priestley (2010), teachers play a crucial role as the primary agents of change within the field of education. Building upon this notion, the “Inner game” theory proposed by Gallwey (1979, pp. 13–36) posits that all transformative changes in people’s lives originate from an internal source. Gallwey specifically illustrates how athletes who excel in their “inner game” are more likely to achieve success in their actual competitive endeavors. Drawing a parallel to the realm of education, an effective teacher can serve as a role model and employ strategies to influence students’ personal growth and development. However, it is important to recognize that not every teacher possesses the capacity to fulfil this role. Typically, only highly skilled and experienced educators, similar to accomplished coaches in sports (Mooney, 2006), can effectively navigate this responsibility.

By strengthening students’ internal motivation and behavior, educators can foster corresponding external manifestations of motivation and behavior. The concept of motivation, as defined by Everard et al. (2004), revolves around “getting results through people” and “bringing out the best in individuals.” In line with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1970, pp. 241–260), motivation can be categorized into five stages: physiological needs (e.g., food, drink, and warmth), safety needs (e.g., freedom from risks), social needs (e.g., friendship, love, and group acceptance), ego needs (e.g., status, respect, and prestige), and self-realization needs (e.g., achieving success and psychological growth). Therefore, the motivation to study and engage in academic pursuits primarily aligns with the self-realization stage, as it encompasses the desire for personal fulfillment and psychological development.

Coaching and mentoring in literature context

Coaching and mentoring demonstrate significant parallels with literature as they all emphasize self-education, pedagogy, and moral values (Goldensohn, 1992). According to the National Academy of Education named after Altynsarin (2016), the Kazakh literature curriculum in secondary schools aims to foster students’ aesthetic, moral, national, and humanistic values. The study of literature also strives to cultivate creativity, promote a passion for reading, enhance communication skills, and facilitate the exploration of positive and negative character traits. However, limited scholarly literature specifically addresses coaching and mentoring within the Kazakhstani educational context, primarily because coaching and mentoring have historically been associated with sports and business domains. To bridge this gap, a comparative study conducted by Smagulov and Karinov (2018) examined the rational relationships between life coaching provided by Western coaches/mentors and the works of Kazakh writers and poets. Therefore, it is imperative to draw upon examples from foreign researchers that highlight the utilization of literature in coaching and mentoring practices.

An exemplary academic contribution in this field is Eastman’s (2019) extensive research entitled “Coaching for Professional Development: Using Literature to Support Success.” The author outlines the scope and rationale behind her investigation in the following scholarly passage:

I decided on the experiment of using literature as a coaching tool, and I must admit that the enterprise originated to some extent in an act of self-indulgence. I love literature, have taught literature, and have an irrepressible desire to use literary works in my practice as an educator. This book explores the value that literature can bring to coaching. (Eastman, 2019, p. 1)

One noteworthy example of applying literature to the coaching process is the “Changing Lives through Literature (CLTL)” program, which was provided in a prison in the United States. This distinctive program originated in Massachusetts and subsequently expanded to other states, as well as England. In the CLTL program, participants were assigned novels to read, followed by organized discussions aimed at deeply impacting their emotional and moral development. The chosen novels included works such as “Of Mice and Men” by Steinbeck, “The Old Man and the Sea” by Hemingway, “Seawolf” by London, “Affliction” by Banks, and “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” by Kesey. The organizers emphasized the potential for these activities to transform lives both internally and externally while acknowledging the associated risks.

Another notable example can be found in Leo Tolstoy’s novel “War and Peace,” where General Bagration serves as a mentor and role model for the growth and development of two young Russian soldiers, Nikolai Rostov and Andrei Bolkonsky (Mumma, 2013). Moreover, Eastman (2019, p. 158) explores the impact of Shakespeare’s writings on clients’ motivation and self-actualization in the context of coaching.

Reading literature can stimulate coaches’ thought processes, encouraging deeper reflection on various situations and enhancing their emotional intelligence. Integrating literary works into coaching practices can maximize their potential benefits (Eastman, 2019, p. 158). It is important to note that reading books in general offers numerous practical advantages. Supporting this notion, a significant study conducted by Sabine and Sabine (1983) involved interviews with 1,382 readers, concluding that books act as powerful catalysts for personal transformation. Similarly, Ross (1999, pp. 793–795) outlined a range of benefits derived from reading books, including expanding possibilities, improving social skills, fostering the courage to make changes, and promoting acceptance.

Teaching is a profession primarily concerned with moral development and the cultivation of students’ moral values (Fullan, 1993, 2005). Lamarque (2008) asserts that reading literature offers cognitive benefits that contribute to personal growth. According to Robinson (2005), literature provides emotional support, facilitates self-understanding, fosters connections with the world, and aids in dealing with difficulties. Literary texts have a greater capacity for stimulating self-reflection compared to non-literary texts due to their thought-provoking nature (Koopman and Hakemulder, 2015, p. 96). Shirley (1969) highlights how reading Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” helped readers overcome their self-centeredness. Literature becomes an ideal tool for examining actions, experiences, and emotions, establishing a meaningful connection between the real and the fictionalized lives. In ancient Greece, there was a belief that people could not fully experience life without having stories that resonated with their own experiences (Eastman, 2019, pp. 7–10).

Eastman (2019) analyzes various literary works and shares her own experiences to illustrate the potential impact of literature. For instance, she suggests that “The Swimmer” could facilitate coaching conversations (p. 2), “Alexander’s Bridge” might guide coaches in exploring their colleagues’ envy (p. 54), and a story about Anton Rosicky led students to experience physiological changes, feeling calmer and more at peace (p. 56). Reading “Rosicky” also made one student contemplate “the barrenness of collecting new things” (p. 60).

Literary works offer psychological, emotional, and communicational benefits, providing practical advantages for readers, students, and participants. Eastman (2019, p. 67) observes that using a coaching toolkit based on literary works enables individuals to express and manage their emotions effectively. Moreover, individuals who encounter certain problems for the first time can draw on their reading experiences to navigate crises successfully. Additionally, reading literary works enhances conversational skills, as shared knowledge of the same novel between a coach/mentor and their coaches/mentees can facilitate meaningful dialogues that address seemingly unsolvable or incomprehensible issues. Effective communication is fundamental to successful social interactions.

Douglas and Carless (2008) employed stories, both literary and biographical, as pedagogical tools to promote, stimulate, and support athletes, with fiction serving as the primary literary genre in this context (Eastman, 2019, p. 318). Fiction offers flexibility in incorporating diverse information, including characters’ stories and biographies. Readers can learn from characters’ actions, thoughts, and mistakes, fostering empathy and gaining insights into their personal lives.

In summary, literature plays a significant role in promoting personal and professional development by offering cognitive, emotional, and communicational benefits. Integrating literature into coaching practices has the potential to maximize its transformative impact.

Poetry coaching and mentoring

Poetry as a coaching and mentoring tool can set people to think deeply and influence the heart and soul. As argued by Humphrey and Tomlinson (2020) poetry has the power to enable creativity, awareness, emotion, and empathy. This view is developed by Bachkirova and Jackson (2011, p. 103) who mention that poetry can change people. International Academy of Poetry Therapy (2023) can be a good illustration of how mentoring techniques can be applied in helping clients with reframing and support. A qualitative study by Kreuter (2007) has analysed a perspective of the poetic mantra in making people (prisoners) positive and affirming better life choices. Threlfall (2013) argues that applying poetry in teaching can help learners consider strengths, develop weaknesses, develop academic potential, analyse social worlds, look and move forward to actions. Applying poetry in mentoring practice can contribute to change in people’s lives, minds, hearts, souls, knowledge, and wisdom (Snowber, 2005). Xerri (2017) ads that spoken-word poetry has more effect on young people’s development. According to Humphrey and Tomlinson (2020), the use of poetry is not well-established yet. Authors examined some poems such as “Pedestrian Women” by Robin Morgan, and “Hope” by Emily Dickinson and claim that using metaphors is a good practice in literary coaching.

Thompson (2021) claims metaphors in coaching and mentoring from literature help to promote success and solve issues which people face. They can provide new insights, inform and benefit the process. Another qualitative study examines the use of the metaphor “Magic” (Seto and Geithner, 2018). Authors argue metaphor “Magic” is helpful in building and exploring clients’ metaphoric landscape concerning a question, topic, and scenario. By asking open-ended, concise, and direct questions employing metaphors, coaches enabled clients to delve into their attitudes and experiences in different situations. Building upon this concept, Eastman (2019) further develops the idea of utilizing metaphors in coaching, highlighting their effectiveness in capturing clients’ experiences and thoughts during coaching dialogues.

Poems can help students with self-belief and self-esteem as well. According to Van Nieuwerburgh (2012), high confidence is emphasized as a beneficial trait for effectively handling tasks. In the context of 7th-grade Kazakh literature, two poems stand out as potentially valuable for fostering strong self-belief in students.

One of these poems is “Farewell to the Motherland” by Qaztugan, which explores the theme of a poet’s forced separation from his homeland due to an enemy invasion. The poem aims to cultivate a sense of love and reverence for one’s homeland among students. Despite the tragic defeat suffered in the war against the enemy, the author maintains unwavering self-belief, as exemplified in the concluding two lines of the poem.

A powerful black deer antler,

Symbolizing strength and support for the community,

The leader of the flock of sheep,

Known for eloquence and skill in debates,

If the enemy dares to confront,

I will bring them down with such force,

Like an old camel that kicks up dust to the heavens,

I am Qaztugan Qargaboyly! (Tursyngaliyeva and Zaikenova, 2017, p. 56)

The author utilizes the literary device of hyperbole, commonly found in poetry, to depict oneself. This figurative language technique serves to enhance the description by exaggerating and imbuing it with a dramatic quality. Moreover, within the context of the short-term coaching and mentoring course, there is another poem that pertains to the theme of self-belief. “Exegi Monumentum” by Pushkin, a work from the World Literature unit, delves into the creative endeavors of the Russian poet. In this poem, Pushkin characterizes his written works, including his poems, as “a monument forever,” underscoring their enduring significance and profound impact.

A monument, unforged, I for myself erected.

A common path to it will not be ever lost,

And its unheedful head reigns higher than respected,

The known Alexandrian Post! (Tursyngaliyeva and Zaikenova, 2017, p. 188)

The enduring fame and global translations of Pushkin’s poems validate his claim. His works are not only read by children but also by adults worldwide. Both poems emphasize the importance of strong self-belief and confidence. It is clear that without believing in one’s abilities and goals, achieving them becomes challenging. “Exegi Monumentum” exemplifies this concept as the author confidently portrays his future.

Methodology

Study design

The study employed an interactive approach and a qualitative case study methodology to investigate the perspectives of coaching and mentoring methods in teaching literature. This choice of research design was driven by practical considerations, including the relatively short duration of the course (1 month) and the limited number of participants (30 students). During the study, two primary methods were utilized: the first involved students writing “life scenarios” inspired by diary writing, and the second comprised a final focus group interview. Focus group discussions were to discern participants’ insights regarding the application of coaching and mentoring approaches in literature teaching.

Study participants

A one-month coaching and mentoring course was organized, targeting teenagers aged 14–18. The selection of this age group was motivated by two primary factors. Firstly, students within this age bracket are mandated to study literature as a compulsory subject in their school curriculum. Secondly, our research team possesses a specialized focus on this specific cohort of school-aged individuals. To engage participants, social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp were utilized, and approximately 30 students from various regions in Kazakhstan were registered. The course was offered free of charge. Five online lectures were conducted via the Zoom platform, aiming to introduce students to the transformative potential of reading and the value of exploring literature through coaching and mentoring approaches. The decision to deliver the lectures online was motivated by the geographical dispersion of the participants across different cities in Kazakhstan, as well as the cost and time-saving benefits. These five lectures effectively communicated the course’s objectives and addressed students’ inquiries effectively. Although some students were unable to attend certain online sessions due to various reasons, the average attendance rate ranged from 20 to 23 out of the total 30 students.

Study procedure

Information was disseminated to participants through a combination of online lectures and email correspondence. The online lectures served the purpose of elucidating the role, significance, and importance of employing coaching and mentoring methods in the teaching of literature. Emails were effective instruments in delivering additional information, including a compilation of links to online resources. Furthermore, email correspondence was used to respond to inquiries and to submit assignments and homework.

During the course, students were assigned two principal tasks: making regular entries to their diaries and the composition of a “life scenario” in the final week. It is important to delve into these tasks in greater detail.

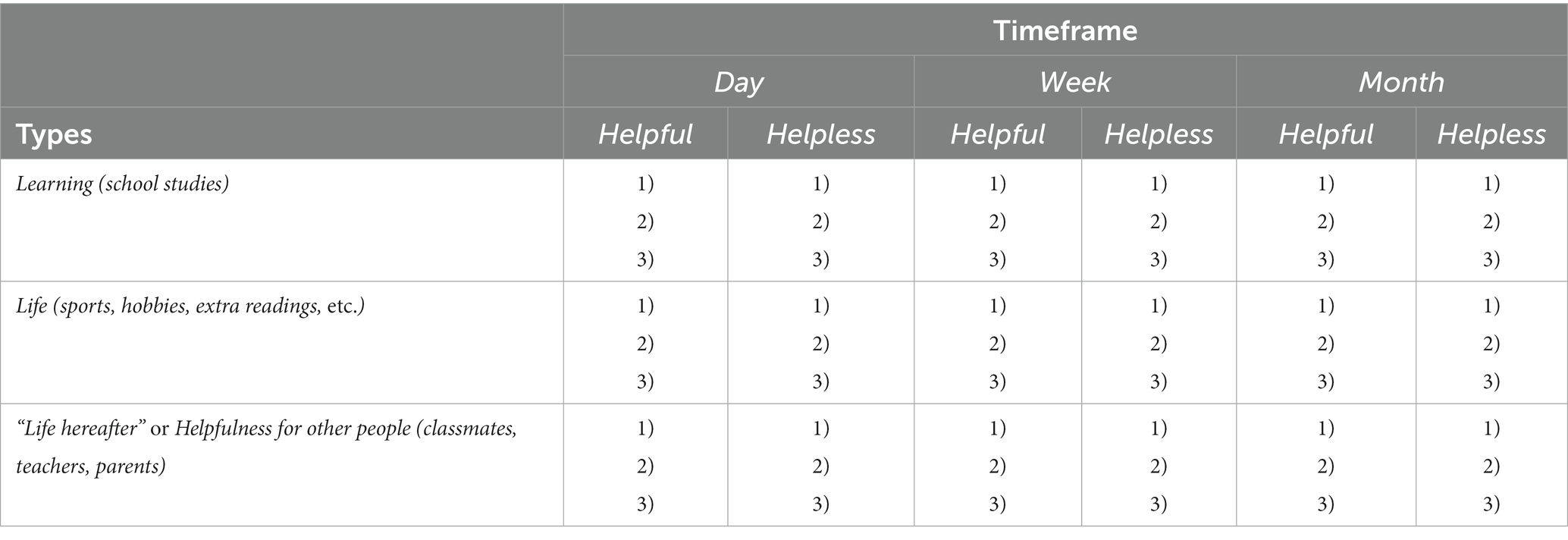

Firstly, the diary writing template (Table 1) was developed by drawing from a fusion of Abay’s (Kazakh philosopher) edification principles. Specifically, author’s word number 15, and Whitmore’s GROW model were taken as a basis for the template. Table 1 shares similarities with the GROW model commonly employed by coaches and mentors (Whitmore, 2002; Eastman, 2019). The GROW model consists of four stages, each serving a specific purpose: Goals (establishing the final objective), Reality (assessing the current situation), Options (evaluating different approaches and methods), and Will (formulating a plan of action). The Reality stage holds particular importance, as goal-setting depends on an accurate assessment of the present circumstances. Table 1 can be utilized for evaluating the current situation (Reality). Eastman (2019, p. 65) suggests the addition of “r” for “risks” to the model, placing it between “Options” and “Will” (GROrW). This inclusion is valuable, as evaluating risks is crucial in any plan. Overall, the GROW model provides guidance for individuals in their pursuit of achieving goals.

Table 1. An example of the action analyzing table provided to the participants of 1 month coaching and mentoring course.

Students were provided with instructions to assess their daily, weekly, and monthly activities. They were supposed to categorise them as either beneficial or non-beneficial concerning academic outcomes, personal life, and helpfulness of actions to society. This categorization employed the use of green and red colors, denoting helpful and unhelpful actions, respectively.

The practice of diary writing played a pivotal role in fostering the development of students’ “life scenarios,” which were composed during the final week of the course. In accordance with Alyautdinov (2013, pp. 90–100), a “life scenario” can be defined as a future-oriented model that spans various temporal horizons (e.g., 1, 2, 5, or 10 years). In this construct, individuals depict themselves as the principal actors, striving to achieve a set of predefined goals.

Before participants embarked on the task of crafting their life scenarios, they were presented with a lecture that expounded upon the intrinsic value of this exercise. Two preliminary exercises were recommended as prerequisites. The first exercise, known as the “inner dialogue” (Alyautdinov, 2013, pp. 8–18), entailed students attentively listening to their inner thoughts to identify their desires, strengths, and challenges. Subsequently, they were prompted to articulate their future objectives and establish corresponding deadlines, as elucidated in Magauin’s “The Golden Notebook” (1998, p. 127).

The final phase entailed the composition of “life scenarios,” wherein students provided a comprehensive narrative delineating their envisioned future lives. These scenarios elucidated their goals, strengths, potential risks, deadlines, and other pertinent details. Individualized feedback on all students’ life scenarios was conveyed through email correspondence or online meetings.

At the last week of the course, a focus group interview was conducted with the participants in an online format. The primary aim of this discussion was to assess the course’s strengths and weaknesses, as well as to glean insights into the prospective utility of coaching and mentoring methods in the context of literature teaching.

Data analysis

The analysis of the data collected during the course proceeded in two different directions. First, the participants’ daily schedules and “life scenarios” written in the last week were reviewed based on the reflective journal method (Lindroth, 2015, pp. 66–72). To protect the anonymity of the students, each participant was assigned a pseudonym (Student A, Student B, Student C) based on the order of their submissions.

Next, transcripts of the focus group interviews were transcribed. The participants were identified by nicknames (Student 1, Student 2, Student 3) based on the order of their contributions, and their actual names were kept confidential. Subsequently, all transcripts were organized, and similar comments were grouped and coded (Braun and Clarke, 2013). Although these two methods were used in the data analysis, the information obtained from each method was not mixed. In alignment with the research’s objectives, the information derived from each method addressed specific research questions.

Ethical considerations

Prior to the initiation of the online lectures, explicit consent forms and participant information sheets were dispatched to all enrolled individuals electronically. These documents comprehensively outlined the course’s objectives, the safeguarding of personal information, and the security measures in place for data protection. Participants were duly apprised of their unfettered prerogative to discontinue their involvement in the study at any given time. Additionally, given the focus on adolescent participants, the acquisition of parental consent forms was requisite. It is worth noting that the research topic in question did not involve any sensitive subject matter, and the projected mental risks were deemed negligible (Cohen et al., 2018).

Results

Initially, participants of 1 month course found it interesting to integrate coaching and mentoring methods in literature teaching. They consider that they read different literary poems, novels, and fiction but never thought about the practical benefits of literature. Let us share some thoughts from the focus group discussion:

“I did not realize that literature can influence people at this level” (Student 1); “Mostly I read fiction as leisure, now I will pay more attention to their meaning” (Student 4); “Before I have searched motivation, self-belief from books about business, psychology, but now I understand that I can find them from literary books” (Student 17); “Doing exercises like “diary writing,” “self-analyzing” helped to understand Abay’s edification words better” (Students 10, 11); “Poems are magic. They are easy to read and have much power” (Students 5, 18, 24); “I will do read literary books with extra attention” (Student 26).

Some students recommended re-organizing literature lessons at school integrating the elements of business, coaching, mentoring, and psychology. They support that there should be more exercises, tasks, and assignments relating to it (Students 2, 6, 13, 14, 23). Almost half of the participants argue that the course helped to increase self-belief, understand their goals for the future time, make priorities between deals, and establish time-management skills.

Throughout the one-month coaching and mentoring course, it became evident that certain students encountered challenges related to self-confidence and actively sought guidance to address this particular impediment. Reading and reflecting on the meaning of the aforementioned poems were recommended as initial steps. Additionally, students were encouraged to explore various books, music, videos, and other resources to enhance their self-belief and motivation. As a result, some participants overcame their self-belief issues:

“I think of becoming a billionaire and a president of Kazakhstan simultaneously. Then I can spend some part of my wage on the Kazakhstani economy as a dedication” (Student B); “My best dream is to become a student of Nazarbayev University. Before this course it was just a dream. But now it became a goal” (Student F); “I want to find a job in Elon Musk’s company. I think working there will give me an enormous experience so after some time I can establish my own high-tech company” (Student L).

Pursuing ambitious dreams and goals was common among course participants, considering their age and aspirations. The mentioned above poems by Pushkin and Qaztugan exemplify the ambitious self-belief and goals that individuals can strive for. However, it was recommended to emphasize the importance of setting realistic goals that are easier to believe in. Alongside this, it was encouraged to explore broader goals for future perspectives. To facilitate this, creative brainstorming sessions were conducted to foster innovative ideas and establish new goals for the upcoming period (Connor and Pokora, 2007, pp. 124–134).

Discipline and time management emerged as recurring challenges for some students. Many participants expressed concerns about insufficient time for lesson and examination preparations. In response, the course addressed the value of time, action planning, power management, and prioritization. Kazakh literary works focusing on time management were introduced, including poems such as “A Ticking Clock” by Abay (2012), “The Value of Time” by Temirbay (2019), and “A Value of Youth” by Sultanqozhauly (2014). Additionally, participants were guided to prioritize their upcoming activities by categorizing them into three groups: “must/need/want to do.” The biographical novel “Me” by Magauin (1998) served as a model for this task, with selected quotes about time management and scheduling actions from “The Golden Notebook” used as prompts.

In the novel “The Golden Notebook,” when I was twenty years old, I had a grand plan to write twenty-five extensive novels, forty-nine shorter novels, and one hundred and thirty-four stories… (Magauin, 1998).

During the crucial period between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five, which I consider to be the most significant seven years of my life, I made sure that every day was purposeful. In our youth, we possess our most productive and valuable time. Throughout these extensive seven years, my sole focus was on engaging in reading and pursuing knowledge. I dedicated a minimum of ten hours a day, often extending to twelve or even fifteen hours, to this pursuit. (Magauin, 1998)

Seventeen “life scenarios” were received via email, and commentaries with recommendations were provided in response. These exercises helped all students to reorganize their goals and plan perspective. All of them marked at least 4 from a total of 5 in the focus group discussion. As participants mentioned practicing the “daily action sheet” and developing “life scenarios” were very interesting and helpful exercises to understand themselves (Students B, D, M), establish goals and deadlines (Students A, B, D, F, H, I, K, P), increase motivation (Students C, F, I, J), broadening horizons and believe that goals will be realized (Students D, E, J, K, L).

Discussion

Participation in the one-month course significantly broadened the students’ perspectives on literature. Prior to the course, many participants had not expected the application of coaching and mentoring methods in literature teaching. The study’s results clearly demonstrate that the incorporation of coaching and mentoring techniques into literature teaching had a positive impact on students’ self-belief, motivation, and time management skills.

A substantial number of participants emphasized the valuable role of literature in fostering self-awareness and enhancing their self-belief. Specifically, exercises such as “Life Scenarios” and “Daily Action Sheets” empowered them to engage in introspection and effectively identify their strengths and weaknesses. This practice proves beneficial for evaluating performance quality (Wallace and Gravells, 2007). As a result, students can gain insights into their strengths and weaknesses through self-reflection, reducing their reliance solely on the guidance of coaches and mentors. Abay advocates the use of inner dialogue as a method to facilitate this self-awareness process.

If you wish to be counted among the intelligent, then ask yourself once a day, once a week, or at least once a month: “How do I live? Have I done anything to improve my learning, worldly life, or life hereafter? Will I have to swallow the bitter dregs of regret later on? Or perhaps you do not know or remember how you have lived and why? (Abay, 2005, p. 108).

The author posits that engaging in self-dialogue confers the advantage of comparing one’s present situation with the past, and regular practice of inner dialogue enhances the efficacy of self-evaluations. Throughout the one-month coaching and mentoring course, participants were introduced to a specific Table 1, exemplifying these principles. In this context, coach custodians recommend employing dialogue as a tool to comprehend an individual’s desires, thoughts, and beliefs. Furthermore, Armstrong (2012) notes that meaningful conversations can assist coaches in recognizing issues and hold the potential to yield transformative results.

Self-analysis leads individuals to cultivate self-belief. Literary works such as “Exegi monumentum” by Pushkin, “Farewell to the Motherland” by Qaztugan, and “I Will Come Out Alive as a Human Being” by Toraigyrov (Aktanova et al., 2018, pp. 55–56) serve as excellent illustrations of strong self-belief. All poems are composed in the first person by the author and exhibit the high levels of self-confidence possessed by these poets. Throughout the course, participants engaged in reading and discussions about the meanings of these poems. For instance, Pushkin expresses the belief that his literary works will endure eternally, surpassing even the Alexandrian State. Qaztugan portrays himself as an unbreakable leader with unwavering self-belief. Toraigyrov demonstrates remarkable confidence that his goals will materialize. Participants found these poems instrumental in fostering self-belief and in shaping their “life scenarios.”

These literary works assisted students in comprehending the significance of coaching and mentoring methods in the development of self-belief. Several studies emphasize the role of coaching and mentoring in self-belief development: coaching and mentoring provide emotional and social support to students (Van Nieuwerburgh, 2012); mentoring has a positive impact on academic outcomes and self-confidence (Lay, 2017); mentoring leads to transformative changes in individuals’ lives (Kochan, 2013).

Developing strong self-belief significantly boosted participants’ motivation to pursue their dreams. The majority of students acknowledged that the one-month course empowered them to establish ambitious goals. In this context, reading literary works and gaining insights from lecturers regarding the practices of various coaches and mentors played a vital role. Several examples from Kazakh literature can illustrate this.

Kazakh philosopher Abay provides insights into motivating young individuals for academic pursuits with the following statement: “A child does not naturally have the desire to learn. They must be influenced through coercion or incentives until they develop a thirst for knowledge” (Abay, 2005, p. 151). This perspective shares similarities with the “carrot and stick” approach commonly employed by some coaches and mentors (Everard et al., 2004). Additionally, the idea of a “thirst for knowledge” aligns with the principles of the “inner game” theory (Gallwey, 1979), which emphasizes the importance of students studying independently without external supervision from teachers, parents, or siblings.

Numerous novels and poems in Kazakh literature can be associated with motivation for goal achievement. For instance, “we should not limit ourselves to knowledge, but rather act based on what we know…” (Kudaiberdiyev, 1988, p. 86), “let the advice of an intelligent person reach those who possess aspiration” (Abay, 2012), and “the most wretched among men are those without aspiration…” (Abay, 2005, p. 179). Additionally, there are short stories from schoolbooks prepared under the Ministry’s guidance, such as “How to Find Wealth?” by Altynsarin (Kerimbekova and Quanyshbayeva, 2017, pp. 48–49), as well as “The Boy Who Cleaned the Snow” and “To Carry the Sleigh on Foot” by Abdiqadirov (Aktanova et al., 2018, pp. 86–93).

At this stage of the one-month course, all participants had completed their “daily action sheets,” possessed strong self-belief, and were in the process of developing their “life scenarios.” They had gained a comprehensive understanding of how the combined approach of reading literary works and utilizing coaching/mentoring methods could be applied effectively. Reading and discussing the aforementioned literary works in group settings significantly contributed to enhancing the motivation and determination of the participants in pursuing their goals.

There is supporting research regarding the practical benefits of reading literary works. Eastman (2019, p. 158) found that reading Shakespeare had a positive impact on increasing clients’ motivation for self-development. Additionally, a study by Alden et al. (2003) demonstrated that engaging in various exercises with students contributed to an increase in their motivation to read. Everard et al. (2004) proposed the concept of “getting results through people,” which can be interpreted as how external motivation and personal character influence an individual’s internal motivation.

The subsequent stage of the course involved the participants taking action in alignment with their goals. However, an issue emerged concerning the effective scheduling of their activities and the challenge of managing their time efficiently. In response, the course focused on imparting valuable time management strategies and promoting discipline.

To illustrate the importance of time management, various poems were shared and discussed with the participants. These poems included “A Ticking Clock” by Abay (2012), “A Value of Youth” by Sultanqozhauly (2014), and “The Value of Time” by Temirbay (2019). “A Ticking Clock” and “A Value of Youth” are concise poems that emphasize how time swiftly passes, particularly in one’s youth when energy abounds. In contrast, “The Value of Time” by Almas Temirbay is a lengthy poem comprising 320 lines. Despite its length, the poem is composed in straightforward language, making it easily accessible. It provides numerous relatable examples from everyday life, illustrating the consequences of wasting time on futile activities, engaging in conflicts, indulging in gossip, and fixating on transient matters.

Extensive discussions were held with the participants regarding the content of this poem. They found the examples presented by the author to be engaging, pertinent, authentic, and reflective of the realities of life. Additionally, the participants had the opportunity to listen to a professional audio rendition of the poem, accompanied by music, which added an intriguing dimension to their engagement with the material.

To enhance the coaching and mentoring process, the utilization of audio and video materials was strongly encouraged (Everard et al., 2004). Watching documentaries, movies, and listening to audiobooks served as effective methods to save time and energy. These activities could be conveniently integrated into students’ daily routines, such as during their commutes to school or during leisure time. Unlike intensive reading, listening, and watching require less mental effort, allowing students to allocate the time and energy saved to other enjoyable leisure activities. According to Tracy (2001), the practice of daily audiobook listening during commutes can be as academically enriching as completing a full bachelor’s degree, which traditionally spans 3–4 years.

Participants found this idea intriguing. On one hand, delving into the ideas of Kazakh poets regarding time management provided new insights for the students. On the other hand, the suggestion of utilizing audiobooks and video materials demonstrated the practical advantages of combining literature reading with coaching and mentoring. This approach proved beneficial for both enhancing their literary engagement and developing time management skills.

The impact of the one-month course on the participants’ lives underscores the vast potential of literature when applied in conjunction with coaching and mentoring methods. Nearly all participants grasped this perspective on literature. They recommended reorganizing school literature lessons to incorporate more practical elements similar to those applied in this course. The course proved effective in helping students transform themselves in terms of their goals, motivation, and time management skills. There is substantial evidence to suggest that the course met the expectations of both the instructors and the participants.

Conclusion

The provided study contributes significantly to the understanding of the potential benefits associated with integrating coaching and mentoring methods into literature teaching. It is worth noting that the literature on this specific topic is limited, thus underscoring the significance of this paper as a pioneering work that lays the foundation for future research in this area. The one-month course described in the study effectively showcases the practical advantages of incorporating coaching and mentoring techniques within the learning process.

While it is evident that excessive utilization of coaching and mentoring methods, as well as transforming school lessons into business coaching sessions, would be inappropriate. It is reasonable to posit that occasional application of these approaches can complement the educational experience. Hence, it can be inferred that integrating coaching and mentoring with literary examples proves beneficial in broadening students’ horizons, fostering self-belief, and establishing meaningful goals.

Moreover, compelling evidence supports the assertion that the incorporation of coaching and mentoring methods in literature instruction facilitates a perceptual shift, cultivates unwavering determination, nurtures active internal dialogue, enables effective goal-setting, and promotes the development of functional literacy. Notably, participants in the one-month course found the evaluation of reality through inner dialogue to be particularly captivating. Additionally, students readily identified the poems by Sultanqozhauly and Pushkin as striking instances of resolute self-belief. Despite the participants’ initial encounter with writing a “life scenarios,” they all comprehended the value of planning, acquired valuable skills, and formulated concrete plans for their future endeavors.

Limitations and suggestions for the future research

One month may not provide sufficient time to comprehensively evaluate the long-term outcomes of the course, considering its primary focus on information dissemination and encouraging self-reflection. Nonetheless, monitoring the participants’ progress over an extended duration would be advantageous. Conducting an additional survey would serve as a valuable tool in this endeavor. However, assessing students’ development within a condensed timeframe presents inherent challenges. Nevertheless, it is evident that most participants acknowledged literature’s inherent value in fostering personal growth, development, and resilience. As a result, they demonstrated a genuine commitment to self-improvement and embarked on a transformative journey. It is important to note that the literary examples and experimental activities presented during the course exhibit potential for further application and investigation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in the study was provided by the participants’ parents/next of kin.

Author contributions

AK: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZS: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation. ST: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abedin, Z., Biskup, E., Silet, K., Garbutt, J. M., Kroenke, K., Feldman, M. D., et al. (2012). Deriving competencies for mentors of clinical and translational scholars. Clin. Transl. Sci. 5, 273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00366.x

Aktanova, A. S., Zhundibayeva, A. K., and Zhumekenova, E. K. (2018). Textbook for the 6th grade of secondary school, Astana: Arman-PV.

Alden, K. C., Lindquist, J. M., and Lubkeman, C. A. (2003). Using literature to increase reading motivation.

Alred, G., and Garvey, B. (2000). Learning to produce knowledge: contribution of mentoring. Mentor. Tutoring 8, 261–272. doi: 10.1080/713685529

Anderson, E. M., and Shannon, A. L. (1988). Toward a conceptualization of mentoring. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 38–42. doi: 10.1177/002248718803900109

Armstrong, H. (2012). Coaching as dialogue creating spaces for (mis)understandings. Int. J. Evid. Based Coach. Mentor. 10, 33–47.

Bachkirova, T., and Jackson, P. (2011). “Peer supervision for coaching and mentoring” in Coaching and mentoring supervision: theory and practice: the complete guide to best practice, vol. 230. eds. T. Bachkirova, P. Jackson, and D. Clutterbuck (Maidenhead: Open University Press)

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. A practical guide for beginners. London, SAGE.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. 8th ed. New York: Routledge

Connor, M., and Pokora, J. (2007). Coaching and mentoring at work: developing effective practice, Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Douglas, K., and Carless, D. (2008). Using stories in coach education. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 3, 33–49. doi: 10.1260/174795408784089342

Eastman, C. (2019). Coaching for professional development: using literature to support success. New York: Routledge

Etymology Online. (2023). Etymology online: an online etymology dictionary. Available at: https://www.etymonline.com

Everard, K. B., Morris, G., and Wilson, I. (2004). Effective school management, 4th edn. London: Paul Chapman Pub.

Fletcher, S., and Mullen, C. A. (2012). The SAGE handbook of mentoring and coaching in education, London: Sage

Goldensohn, L. (1992). Elizabeth bishop: the biography of a poetry, New York: Columbia University Press.

Humphrey, D., and Tomlinson, C. (2020). Creating fertile voids: the use of poetry in developmental coaching. Philos. Coach. Int. J. 5, 5–17. doi: 10.22316/poc/05.2.02

International Academy of Poetry Therapy. (2023). Poetry Therapy – The Power of Words. Available at: https://iapoetry.org

Jekielek, S. M., Moore, K. A., Hair, E. C., and Scarupa, H. J. (2002). “Mentoring: A promising strategy for youth development”, child trends research brief. Available at: https://www.childtrends.org/publications/mentoring-a-promising-strategy-for-youth-development (Accessed 3 May 2022).

Kadyrova, S. (2017). “The role of the mentor in the first year of teaching” Nugse Res. Educ. 2, 27–35. Available at: http://nur.nu.edu.kz/handle/123456789/2413 (Accessed 8 May 2021).

Kerimbekova, B., and Quanyshbayeva, A. (2017). Textbook for the 5th grade of secondary school, Almaty: Mektep.

Kochan, F. (2013). Analyzing the relationships between culture and mentoring. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 21, 412–430. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2013.855862

Koopman, E. M., and Hakemulder, F. (2015). Effects of literature on empathy and self-reflection: a theoretical-empirical framework. Journal of Literary Theory 9, 79–111.

Koroleva, Y. (2017). The role of mentoring in teacher professional development [Master’s thesis]. Nazarbayev University Graduate School of Education. Available at: http://nur.nu.edu.kz/handle/123456789/2582 (accessed 6 May 2021).

Kreuter, E. A. (2007). Creating an empathic and healing poetic mantra for the soon-to-be-released prisoner. J. Poet. Ther. 20, 159–162. doi: 10.1080/08893670701546452

Lay, K. (2017). Learning mentor support: an investigation into its perceived effect on the motivation of pupil premium students in year 11. STeP J. 4, 42–54.

Lindroth, J. T. (2015). Reflective journals: a review of the literature. Update: applications of research in music. Education 34, 66–72. doi: 10.1177/8755123314548046

Lofthouse, R., Leat, D., and Towler, C. (2010). Coaching for teaching and learning: a practical guide for schools, Guidance report.

Mooney, E. (2006). A study of the qualities of effective Mentor teachers. Seton hall university dissertations and theses (ETDs). Available at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2367 (Accessed 4 March 2021)

Mumma, K. (2013). Warrior, hero, mentor: the influence of Prince Peter Bagration on the fictional protagonists of war and peace. CONCEPT 36

National Academy of Education named after Altynsarin. (2016). Methodological manual for teaching integrated subjects “Kazakh language and literature” (L 2), “Russian language and literature” (L 2), “artistic work” for primary school, toolkit. Available at: https://www.nao.kz/blogs/view/2/675 (Accessed 2 May 2021).

National Academy of Education named after Altynsarin. (2020). Methodical recommendations based on the results of monitoring the implementation of the upgraded curriculum of education. Available at: https://nao.kz/blogs/view/2/1576 (Accessed 28 April 2021).

Priestley, M. (2010). Schools, teachers, and curriculum change: a balancing act? J. Educ. Chang. 12, 1–23. doi: 10.1007/s10833-010-9140-z

Roberts, A., and Chernopiskaya, A. (1999). A historical account to consider the origins and associations of the term mentor. Hist. Educ. Soc. Bull. 64, 81–90.

Robinson, J. (2005). Deeper than reason: Emotion and its role in literature, music, and art. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Ross, C. S. (1999). Finding without seeking: the information encounter in the context of reading for pleasure. Inf. Process. Manag. 35, 783–799. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4573(99)00026-6

Sabine, G., and Sabine, P. (1983). Books that made the difference. Hamden, CN: Library Professional Publications.

Sands, R. G., Parson, A. L., and Duane, J. (1991). Faculty mentoring faculty in a public university. J. High. Educ. 62, 174–193. doi: 10.2307/1982144

Sarmurzin, Y., Menlibekova, G., and Orynbekova, A. (2022). ‘I feel abandoned’: exploring school principals’ professional development in Kazakhstan. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 32, 629–639. doi: 10.1007/s40299-022-00682-1

Satchwell, K. (2006). Mentoring literature review, Alberta Children’s Services: Sue Waring, Rick Walters.

Seto, L., and Geithner, T. (2018). Metaphor magic in coaching and coaching supervision. Int. J. Evid. Based Coach. Mentor. 16, 99–111. doi: 10.24384/000562

Shirley, F. L. (1969). The influence of reading on concepts, attitudes, and behavior. J. Read. 12, 369–413.

Smagulov, Z., and Karinov, A. (2018). Coaching in Kazakh literature. Isolation in coaching. Bull. Karaganda Univ. Philol. Ser. 2, 79–85.

Snowber, C. (2005). The mentor as artist: a poetic exploration of listening, creating, and mentoring. Mentor. Tutoring: Partnersh. Learn. 13, 345–353. doi: 10.1080/13611260500107424

Temirbay, A. (2019). The value of time. Available at: https://bilim-all.kz/olen/7958-Uaqyt-qadiri (Accessed 12 May 2022).

Thompson, R. (2021). Coaching and mentoring with metaphor. Int. J. Evid. Based Coach. Mentor. S15, 212–228. doi: 10.24384/4sve-8713

Threlfall, S. J. (2013). Poetry in action [research]. An innovative means to a reflective learner in higher education (HE), reflective practice: international and multidisciplinary. Perspectives 14, 360–367. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2013.767232

Tracy, B. (2001). The 21 success secrets of self-made millionaires: how to achieve financial independence faster and easier than you ever thought possible. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers

Tursyngaliyeva, S., and Zaikenova, R. (2017). Textbook for the 7th grade of secondary school, Astana: Arman-PV.

Van Nieuwerburgh, C. (2012). Coaching in education: getting better results for students, educators and parents, London: Karnac Books.

Wallace, S., and Gravells, J. (2007). Mentoring (professional development in the lifelong learning sector), 2nd edn, Exeter: Learning Matters.

Whitmore, J. (2002). Coaching for performance: growing people, performance and purpose, 3rd edn, London: Nicholas Brealey.

Keywords: coaching, mentoring, literature, method, teaching

Citation: Karinov A, Smagulov Z, Takirov S and Zhumagulov A (2023) Implementation of coaching and mentoring methods in teaching Kazakh literature to the secondary school students. Front. Educ. 8:1279524. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1279524

Edited by:

Myint Swe Khine, Curtin University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Eila Burns, JAMK University of Applied Sciences, FinlandErnest Afari, University of Bahrain, Bahrain

Sabbir Ahmed Chowdhury, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh

Copyright © 2023 Karinov, Smagulov, Takirov and Zhumagulov. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abylay Karinov, YWJ5bGF5cWFyaW5AZ21haWwuY29t

Abylay Karinov

Abylay Karinov Zhandos Smagulov

Zhandos Smagulov