- 1Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 2Hardwired Global, Richmond, VA, United States

This study assesses the effect of conceptual change pedagogy on students’ attitudes toward pluralism and related rights within culturally sensitive contexts. Global efforts to address the spread of intolerant ideologies that foment radicalization, discrimination, and violence are fraught with controversy. Prior research on the Middle East and North Africa region has found that efforts to address these challenges in the field of education — including reform to curricula, the promotion of narratives inclusive of religious diversity, and civics education initiatives — have had varied levels of success. Absent from these efforts is the development of an effective pedagogy and the training of teachers to identify and address ideologies and behaviors that foment intolerance and conflict among students. Hardwired Global developed a teacher training program based on conceptual change theory and pedagogy to fill these needs. Conceptual change refers to the development of new ways of thinking and understanding of concepts, beliefs, and attitudes. Hardwired Global implemented the program in partnership with the regional Directorate of Education for Mosul and the Nineveh Plains region of Iraq from 2019–2023. From 2021–2023, Hardwired trained 485 teachers in 40 schools across the region. Following the training, teachers implemented two lessons. A mixed method research study — with a primary focus on quantitative data collected — was conducted to determine the effect of the program on student perceptions, understanding, and behavior toward key concepts inherent to pluralism. Quantitative data consisted of a pre-post survey with four multiple choice questions. Scores on pre-surveys were compared to post-surveys and a two sample paired t-test was applied. We documented statistically significant developments in students’ conceptual understanding of key concepts inherent to pluralism and associated rights, including: respect for diversity in expression inclusion of diverse religious and/or ethnic communities, gender equality, and violent or non-violent approaches to conflict. Qualitative data consisted of semi-structured interviews with teachers and students implemented at the conclusion of the program and observations reported by Master Trainers and teachers during training and activity implementation. Findings suggest conceptual change pedagogy on pluralism and associated rights is a promising approach to education about controversial topics in conflict-affected and culturally sensitive environments.

1 Introduction

Given the rise of religion-related conflict globally, governments and organizations have undertaken efforts to address growing concerns about the spread of intolerant ideologies that foment radicalization, discrimination, and violence among youth. But the religious, political, and social dynamics inherent to these efforts are fraught with controversy and tension (Smith et al., 2017).

Children are particularly vulnerable to ideologies that promote intolerance and polarization (United Nations, 2019). The classroom can often serve as a microcosm to observe the impact of the biases, fears, and misconceptions students hold about others, especially those who hold different or dissenting beliefs (Smith et al., 2017; Rea-Ramirez et al., 2020a,b; Abboud and Dbouk, 2022). This is reflected in observations made by teachers in distinct learning environments. On a playground in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, a group of children were playing a game where they pretended to be members of ISIS. As their teacher drew close to them, she observed her students pretending to behead one another. Thousands of miles away, on a playground in San Diego, California, a group of refugee students began fighting. As their teacher broke up the fight, they heard one of the boys say to his classmate that he was a member of ISIS and would “get him back” (Smith et al., 2017).

Religion-related conflict affects nearly every human right, including freedom of conscience, expression, belief, and association as well as equality and non-discrimination. It most often foments in societies in which pluralism is not understood or valued. A pluralistic society is one in which people with diverse ideas, beliefs, opinions, practices, and behaviors can live freely in community with others. Pluralism is not merely coexistence or tolerance — or even diversity — but a deep respect for the humanity of others who share the same inherent human rights. At the same time, pluralistic societies require energetic engagement with diversity and dialog, rather than blind acceptance of ideas or an aversion to debate or expression of dissenting opinions. Individuals in a pluralistic society recognize the equal rights of others who hold different beliefs and engage in different practices, especially when they disagree. In this way, pluralism is antithetical to intolerant ideologies that fuel social and violent conflict.

In the Middle East and North Africa region, most efforts to overcome intolerant ideologies that fuel religion-related conflict have included religious education curricula reform, the promotion of narratives inclusive of religious diversity, and civics education initiatives (Smith et al., 2017). However, these efforts have yielded varied levels of success. Reforms to religious education curricula have historically fomented conflict between civil society and the state as well as between diverse religious communities in the region. Religious authority and religious teaching can be highly sensitive topics. Any efforts to change curricula — either by removing religious texts or by introducing information about diverse religious practices — are often met with fear, hostility, and protest by both majority and minority religious communities (Smith et al., 2017; Rea-Ramirez et al., 2020a,b). Multi-lateral declarations and plans of action — including the Marrakech Declaration (2016), Rabat Plan of Action (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2012), and Beirut Declaration (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2017) — have sought to reach a consensus about principles and practices to guarantee peace among diverse religious and political groups. While these efforts have established varying levels of “common ground,” tension often begins at points of disagreement. In this way, declarations and action plans fail to directly and concretely address topics or issues that are the basis for conflict.

Notably absent from these efforts is the development of a pedagogy and the training of teachers to identify and address ideologies and behaviors that foment intolerance and conflict among students. The classroom can be an important front line of efforts to confront discrimination, intolerance, and violence among youth (Smith et al., 2017; Abboud and Dbouk, 2022). But teachers in conflict-affected environments have reported they are not prepared to address sensitive topics — including issues relating to religion and identity — in their classrooms, and they are advised to avoid controversy altogether. The result is a learning environment in which students are unable to discuss critical issues that affect them, and teachers are unable to address the biases, fears, and misconceptions students have about others that fuel conflict in their schools and communities.

It is in this context that Hardwired Global, a non-governmental organization with Special Consultative Status at the United Nations, set out to answer the following questions:

1. How can teachers be equipped to facilitate discussion about controversial topics relating to pluralism and associated rights in a manner that mitigates tensions and increased respect for the rights of others?

2. How does conceptual learning about pluralism and associated rights inform student perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward controversial topics relating to these rights?

Based on research and experience in the field of human rights and education in more than 30 countries, Hardwired developed a new educational approach to these challenges using conceptual change theory and pedagogy (Smith et al., 2017; Rea-Ramirez et al., 2020a,b; Abboud and Dbouk, 2022). Conceptual change refers to the development of new ways of thinking and understanding of concepts, beliefs, and attitudes (Rea-Ramirez and Clement, 1998; Rea-Ramirez and Ramirez, 2018). While the use of conceptual change pedagogy in the social sciences is relatively new, it has been widely used for many years in the sciences. It is from the sciences that we can begin to understand the possible application and effect, particularly in difficult areas of the social sciences such as human rights. In the sciences, conceptual change occurs when the individual changes understanding and beliefs from naïve conceptions or misconceptions to those that are more scientifically accepted (Chi et al., 1994; Heddy et al., 2018; Vosniadou, 2019). This occurs through first recognizing one’s own beliefs, conceptions, and biases, and then confronting often embedded fears and misconceptions (Hewson and Hewson, 1983; Rea-Ramirez and Clement, 1998; Rea-Ramirez, 2008; Rea-Ramirez and Ramirez, 2018). The curriculum fosters conceptual change in the way learners view the rights and freedoms of others and reconcile those ideals with their own beliefs (Rea-Ramirez and Ramirez, 2018).

When applied in the social sciences, particularly concerning human rights, it is not the intent of conceptual change to change an individual’s beliefs, but rather to help the individual better understand where these come from and how they affect behavior. Conceptual change is also intended to open new avenues of communication with others who may believe differently, affecting their attitudes toward others and, in turn, participation in their communities. Cherry (2022) states that, “Attitudes are often the result of experience or upbringing. They can have a powerful influence over behavior and affect how people act in various situations. While attitudes are enduring, they can also change.” It is this change that conceptual change theory and pedagogy seeks to achieve.

Hardwired’s application of conceptual change pedagogy to education on pluralism and associated rights has provided a deeper look into the process of “conceptually moving from actions based on inherent beliefs to new models of conceptual understanding of others and directly addresses the issues of intolerance, social conflict, and violent extremism” (Smith et al., 2017, 9). Conceptual change pedagogy has proven effective as a vehicle for introducing controversial topics and facilitating change in student attitudes and behaviors related to these topics in a safe classroom environment. But this requires training in ways to embrace, rather than avoid, situations that may cause dissonance and use it as a strategy to foster communication and conversation about controversial topics. Research suggests that dissonance can play an important role in conceptual change, particularly in the area of controversial and/or powerfully emotional topics (Rea-Ramirez and Clement, 1998; Kitayama and Tompson, 2015). Dissonance refers to a sensed internal discrepancy between a conception or belief and another conception or belief (Rea-Ramirez and Clement, 1998). Some have referred to this dissonance as cognitive conflict and have suggested that this conflict can play a positive role in conceptual change when it is integrated with a constructive process (Chan et al., 1997). The first step then is to induce dissonance and the second step is to introduce construction of new ways of thinking. Analogy may be used for the constructive part of this process (Brown and Clement, 1989; Clement et al., 1989; Mason, 1994; Clement, 2013).

Festinger believed cognitive dissonance is “an antecedent condition that leads to activity oriented toward dissonance reduction” (1957, 3). In the area of controversial topics, we suggest that a level of optimal dissonance may be necessary to provide the impetus for conceptual change while not causing the student to shut down because they feel unsafe or threatened. To create the discourse necessary for the dissonance and construction process to occur and that results in the development of critical thinking skills necessary for engaging positively with others who may hold different ideas and beliefs, the teacher needs to understand how to intervene to introduce sources of optimal dissonance. Optimal dissonance should induce the student to either question their prior model or begin to be curious about other possibilities. Recco (2018) suggests that “Students need to debate things they feel passionate about, even if those things are controversial.” At the same time, however, we believe it is critical that this discourse occur in a safe space where students can verbalize controversial ideas and beliefs leading to not only learning but changes in attitudes, beliefs, and behavior. Therefore, the teacher’s role is the continuous monitoring to determine when, where, and how much dissonance is needed to obtain optimal reaction in the student within a safe space. But we have seen that teachers often do not have the knowledge of theory and strategies needed to engage in the dissonance and construction process.

In 2019, Hardwired Global was invited by the Directorate of Education — the regional authority under the national Ministry of Education — to support their efforts to overcome intolerance and mitigate conflict in the Mosul and Nineveh Plains region of Iraq. Historically, Iraq has been entrenched in conflict along religious, sectarian, political and ethnic lines. Legal restrictions limiting freedom of religion and social hostilities targeting religious minorities have affected generations of Iraqis. Clashes between political and sectarian groups, foreign interventions, and the rise of al-Qaeda and affiliated terrorist groups have undermined the country’s stability for decades. In 2014, ISIS fomented a radical ideology against anyone who did not adhere to their interpretation of Islam (Abboud and Dbouk, 2022). Their attacks on religious and ethnic minorities, in particular, were condemned as genocide (UN News, 2016). An estimated 70,000 civilians were killed by ISIS and in the battle to defeat the group, though the total number of casualties is likely much higher, and more than 5 million people were displaced from their homes (BBC News, 2018; Abboud and Dbouk, 2022). While the region was declared “liberated” from the terrorist group in 2017, their radical ideology — and its effect on Iraqis — remains a significant threat (Center for Preventative Action, 2023). Children are among the most vulnerable to this ideology, and teachers have reported that children in the region still openly identify with ISIS. Others returning to their homes remain fearful of those neighbors who lived under, and even supported, ISIS (Abboud and Dbouk, 2022).

It is in this context that the organization undertook a Training-of-Trainer (ToT) model program to train teachers in conceptual change pedagogy and to lead students in conceptual learning about key concepts inherent to pluralism and associated rights, including: human dignity, equality, non-discrimination, the human conscience, the expression of beliefs, and the balance of rights and responsibilities that affect how rights may be limited or restricted in certain circumstances to protect the rights of others. At the same time, the program challenges long held and embedded ideologies, misconceptions, and fears in a way that many other programs do not. This is an important distinction, since merely teaching about a concept is very different from teaching for conceptual change about a concept to achieve behavioral change.

This approach is unique in that it does not require reforms to curricula or any immediate revision of educational content. Rather, the program uses a pedagogy of conceptual change to promote key concepts inherent to universal human rights that lead people toward a greater respect for the dignity of others, including those with whom they disagree, and a greater appreciation for diversity of opinion and ideas (Smith et al., 2017; Rea-Ramirez et al., 2020a,b; Abboud and Dbouk, 2022). The curriculum builds upon five years of research that demonstrates the statistically significant positive impact of education for pluralism and associated rights can have upon teachers and youth, and ultimately their broader communities, by: (a) building a pluralistic environment where people of diverse backgrounds and beliefs are free to explore the spiritual dimension of life together; (b) encouraging dialog and active engagement with people of different backgrounds or beliefs to address underlying fears, misconceptions, and biases held by youth; and (c) building empathy toward others and resiliency to the ideas of hate and intolerance that contribute to violence and extremism (Rea-Ramirez et al., 2020a,b).

The training curriculum prepares educators to develop a robust understanding of pluralism and associated rights, and ultimately develop resilience to the intolerance that fuels conflict with people who hold different beliefs than their own. The curriculum also equips teachers with tools and resources that can be directly applied and implemented in their schools. Throughout the training, teachers participate in small group activities and lessons that actively engage them in cycles of conceptual change: accessing prior conceptions, dissonance, construction, criticism and revision of ideas, and evaluation and application. The conceptual change process extends outside the training environment as teachers continue to experience dissonance and test, apply and revise their ideas as they interact with others in their classrooms and communities. In this way, conceptual change is a continual process that begins during the training and continues throughout life. (See Rea-Ramirez and Ramirez, 2018 article for a more detailed discussion of the conceptual change theory and strategy and Rea-Ramirez and Ramirez, 2018, and Rea-Ramirez et al., 2020a,b for discussion of statistical findings of conceptual change). Once teachers experience and understand their own conceptual change process, they can lead others through the same transformation.

This article evaluates the impact of conceptual change pedagogy on students’ attitudes and behaviors toward key concepts inherent to pluralism and associated rights that are perceived as controversial or sensitive in their cultural context.

2 Materials and methods

To better understand the effect of a curriculum based on conceptual change applied to controversial issues inherent to pluralism and associated rights in Iraq, Hardwired Global designed a training program based on conceptual change theory to equip teachers to use the pedagogy with students. The program was implemented in partnership with the Directorate of Education for Mosul and the Nineveh Plains region of Iraq from 2019–2023. The training model was believed to allow for scalability and sustainability of the program.

From 2019–2021, Hardwired Global equipped 20 Trainers, referred to as Master-Trainers in the program, to train teachers in conceptual change pedagogy and curricula about pluralism and associated rights. Master-Trainers are experienced educators or school administrators from the Mosul and Nineveh Plains region and have worked with students and/or teachers in classroom and school settings. Hardwired identified and selected Master-Trainers based on their educational expertise, capacity to train others, interest in human rights and pluralism education, and ability to manage program activities. Prior to their acceptance into the training program, Master-Trainers completed two interviews, a written evaluation, and participated in a training session through which Hardwired staff assessed their engagement with training material and interaction with others.

From 2021–2023, 10 Master-Trainers facilitated trainings with 485 teachers in the region. Hardwired coordinated with the regional Directorate of Education to select 40 schools from across the region to participate in the program. These schools were selected to reflect the religious, ethnic, and social diversity of the region. Within schools selected for the program, school administrators and Directorate staff identified 10 to 15 teachers in each school — depending on school size — to complete the training. Teachers were selected based on their ability to complete program objectives rather than their previous training experience or understanding of pluralism and associated rights and, as such, reflect more diverse attitudes and behaviors toward key concepts and issues addressed in the program. To this end, the selection of participants — and the impact of the program on their attitudes and behaviors toward pluralism and associate rights — is consistent with what we would likely observe in the broad application of teacher training and curricula across the region.

The training program consisted of two main components: (1) conceptual learning on pluralism and associated rights; and (2) training on effective conceptual change pedagogy to teach about key concepts inherent to this right. Key concepts included: human dignity, equality, non-discrimination, the human conscience, the expression of beliefs, and the balance of rights and responsibilities that affect how rights may be limited or restricted in certain circumstances to protect the rights of others.

Teachers completed two trainings — one training in the spring of 2022 and a follow up training in the summer/fall of 2022. Master-Trainers provided ongoing training and learning support to their teacher cohorts through online meetings and in-person observation as they implemented activities with students. Following the trainings, teachers were required to implement two standardized lessons — one in the fall 2022 academic term and one in the winter 2023 academic term. However, not all teachers implemented a second lesson during the data collection period due to administrative challenges. As a result, the number of students who participated in the winder 2023 academic term is lower than the fall 2023 academic term. A total of 2,452 students participated in the lesson implemented in the fall 2022 term and 1,176 students participated in lesson implemented in the winter 2023 term. Teachers received training on the implementation of both lessons, and Master-Trainers observed the implementation of these activities with students. Teachers and students who participated the program represented the religious and ethnic diversity of Iraq and, notably, the population most affected by the occupation of ISIS and its radical ideology in the country. All teachers and students were displaced from the region or lived under ISIS occupation from 2014–2017. Training and lessons were implemented in single gender/religion and mix gender/religion classrooms as well as in urban and rural communities across the region.

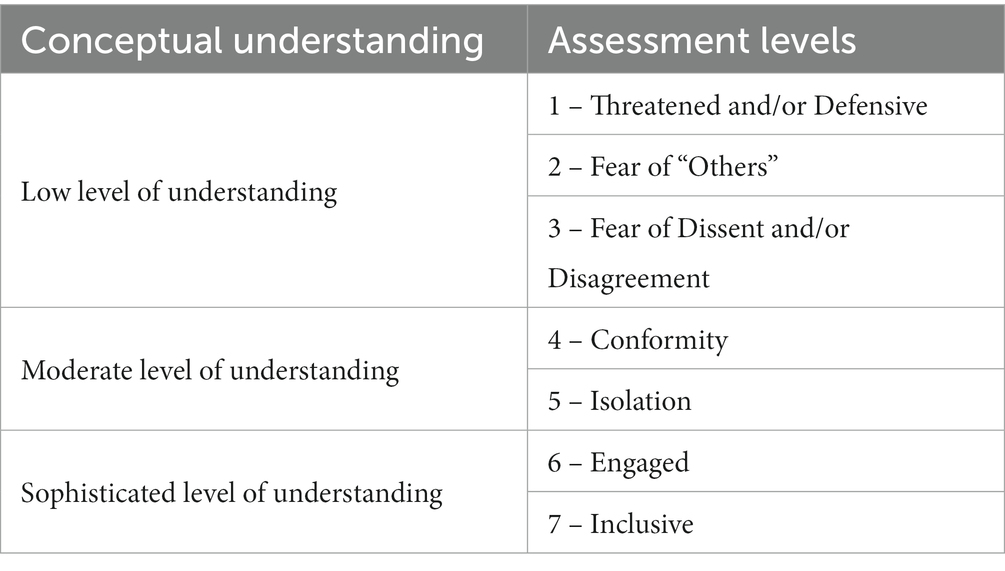

A mixed method research study was conducted to determine the effect of the program on student perceptions, understanding, and behavior toward key concepts inherent to pluralism. Our research focused on two core elements: (1) knowledge about pluralism and associated rights and (2) change in degree and depth of empathy (Smith et al., 2017; Rea-Ramirez et al., 2020a,b). Quantitative data consisted of a pre-post survey made up of four multiple choice questions. The questions focused on the following topics: inclusion and respect for diversity, engagement with diversity, understanding rights, gender equality, and violent vs. non-violent approaches to conflict. The questions were scenario-based where the distractors, rather than being simply right or wrong, were based on a continuum of answers based on beliefs and attitudes. The questions consisted of seven possible scenario responses and were scored on a scale of 1–7. This score range represented the levels of conceptual understanding as well as specific biases, fears, and/or misconceptions exhibited in the community, from least, “threatened or defensive,” through “fear of ‘others’,” “fear of dissent or disagreement,” “conformity,” “isolated,” “interested or engaged,” to the most sophisticated, “inclusive” (see Table 1). Survey scenarios and responses were selected and structured based on several assessments of the biases, fears, and misconceptions learners have about topics raised in each question. Response options for each scenario reflect actual, rather than hypothetical, behaviors and attitudes observed and/or reported by Hardwired staff, trainers, teachers, and education officials in classroom and community settings over more than eight years of work in the Mosul and Nineveh Plains region of Iraq. Participants were asked to choose an answer that best expressed their knowledge, attitudes, or beliefs at that time.

Responses were grouped to reflect low, moderate, and high levels of understanding of pluralism and associated rights. Responses that reflected low levels of understanding indicated students felt threatened by or defensive of the actions of others, fearful of others who believed or behaved different from themselves, and/or feared dissent or disagreement about religious or cultural expectations. Moderate levels of understanding were reflected through responses that indicated students preferred conformity to religious, cultural, or social expectations and/or isolation from others who believe or behave differently from themselves. The highest, or most sophisticated, levels of understanding were reflected in responses that indicated students were engaged or interested in the beliefs and opinions of others and/or a willingness to defend the rights of others, even when they disagree.

The three levels used in our assessment reflect observable changes in attitudes and behaviors in the community, and therefore progress in conceptual learning about key concepts inherent to pluralism and associated rights. Students within a level of conceptual understanding exhibit similar attitudes and behaviors, and student responses within each level reflect the motivation for their attitudes and behaviors in response to the scenario. We employ three assessment levels to assess observable levels of progression in the conceptual change process. Student responses reflecting “Threatened and/or Defensive,” “Fear of ‘Others’,” or “Fear of Dissent and/or Disagreement” within the Low Level of Understanding are consistent with attitudes and behaviors resistant to or even antagonistic toward pluralism and associated rights. Progression to a Moderate Level of Understanding — reflected in “Conformity” or “Isolation” responses — indicates a decisive shift in attitudes and behaviors. These students are neither resistant nor receptive to pluralism and associated rights and, as such, are distinct from students exhibiting Low or Sophisticated levels of understanding. Finally, student responses reflecting “Engaged” and “Inclusive” within the Sophisticated Level of Understanding demonstrate yet another decisive shift in attitudes and behaviors, as they actively model or promote pluralism and associated rights.

Data was aggregated, scores on the pre-surveys were compared to post-surveys, and a two sample paired t-test was applied. Additionally, post-survey results following the Fall 2022 lesson implementation were compared to post-survey results following the Winter 2023 lesson implementation to assess the impact of teachers on students as they gained more experience teaching the curriculum.

Qualitative data consisted of semi-structured interviews of Master-Trainers and teachers collected throughout the program as well as trainer and teacher observations. Interviews were carried out in Arabic, the native language of participants. The interviews used open ended standardized protocol to engage participants in discussions about their own conceptual change through the training and teaching of the curriculum in the classroom. Master-Trainer and teacher observations were collected during training and activity implementation. Master-Trainers reported observations and examples of conceptual they observed during the implementation of activities with students. Teachers reported observations made during activities as well as in the classroom setting following the lessons. Observations were reported to Hardwired training staff through written assessments and/or online evaluation meetings with Hardwired training staff.

There are some limitations to the study to consider. Teachers received extensive training in survey implementation and data collection. Interviews and observations conducted in this study were structured to evaluate student responses to specific topics addressed in the pre-post survey, but were not effectively administered by teachers. Further training on monitoring and evaluation methodology is required for Master Trainers and teachers alike to produce adequate results. Nevertheless, these interviews and observations did provide deeper insight into the impact of conceptual change on both teacher and student interactions and engagement with others, particularly on issues relating to pluralism and associated rights. Qualitative data also provided context for pre-post survey responses. However, the data were not specific enough to assess conceptual change about the four topics — inclusion and respect for diversity, engagement with diversity, understanding rights, gender inclusion, and violent vs. non-violent approaches to conflict —addressed in the survey. Therefore, qualitative data presented in this paper provides some context for survey data. Moreover, survey results were aggregated for the fall 2022 and winter 2023 activities. As a result, this study does not evaluate how the composition of the classroom — mixed gender vs. single gender and/or mixed religion vs. single religion classes as well as urban vs. rural classes— impacts findings.

3 Results

3.1 Pre-post survey findings

We evaluated pre-post responses to four survey questions addressing specific controversial issues inherent to pluralism and associated rights. Analysis of each question — including the pre-survey baseline assessment, post-survey responses from participants in the fall 2022 lesson, and post-survey responses from participants in the winter 2023 lesson — is provided below (see Table 2).

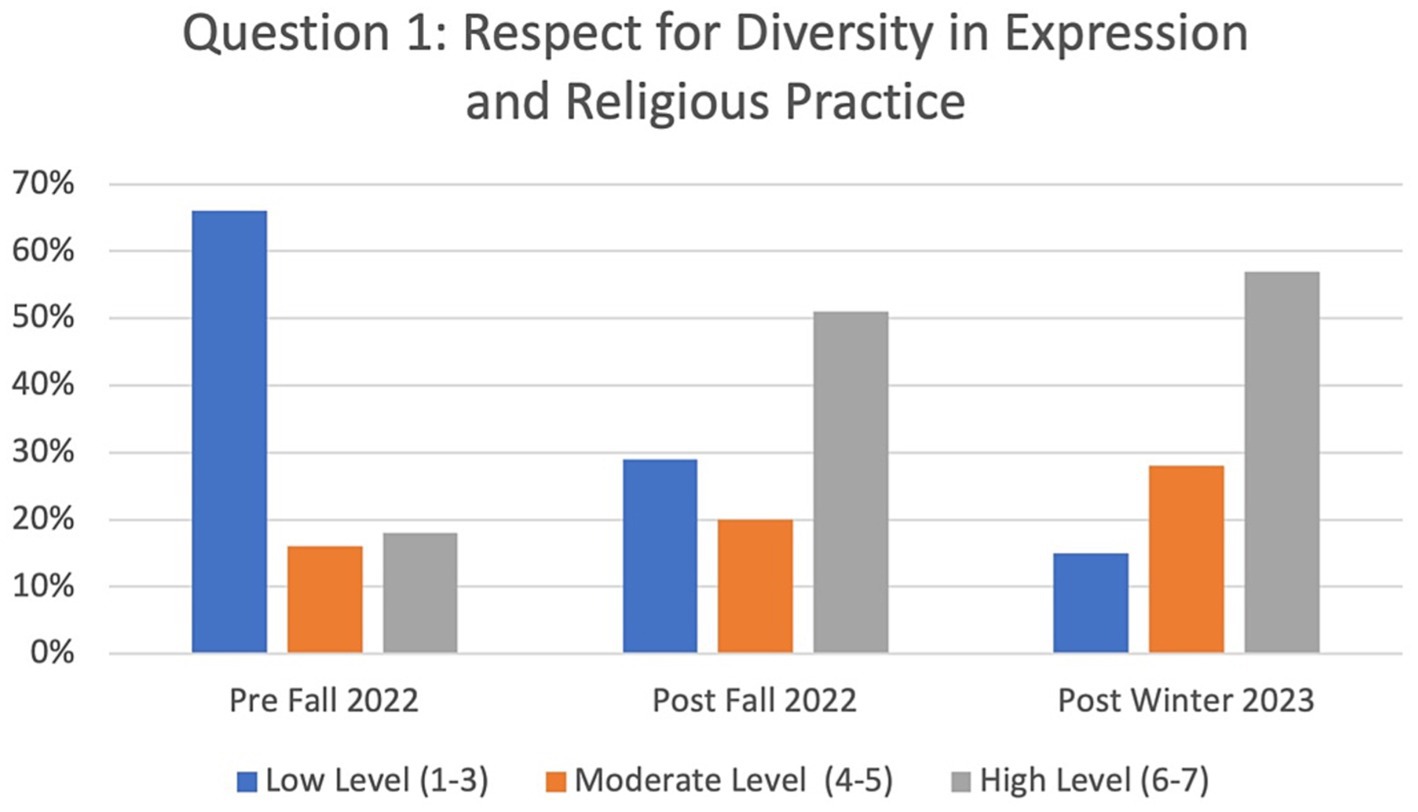

3.1.1 Respect for diversity in expression and religious practice

The first multiple choice question addressed respect for diversity in expression and religious practice, both among various religions and within a single religious community. Fasting, and whether or how individuals choose to observe religious fasts, was identified as a controversial topic relating to pluralism by teachers in Iraq. Religious leadership and cultural or communal norms often dictate how individuals are expected to observe religious practice. The survey question assessed how conceptual learning on pluralism informed students’ willingness to engage with diverse religious expression, particularly when a peer chose to observe religious practices different from the cultural or communal ‘norm.’ The question stated: “You are fasting, but one of your friends chose not to fast. Someone told your friend that it is shameful and disrespectful not to fast with everyone. How do you respond?”

Overall, 72% of students showed a positive move in understanding of respect for diversity and religious expression (see Figure 1). In the pre-survey, more than two-thirds of students selected responses that reflected the lowest levels of understanding of pluralism and associated rights. Nearly 16% indicated moderate levels of understanding, and 18% of students selected responses reflecting the highest levels of understanding. Following the Fall 2022 lesson, the proportion of students reflecting the lowest levels of understanding of pluralism dropped by more than half to 29%. More than half of students indicated the highest levels of understanding. Following the Winter 2023 lesson, the proportion of students indicating the lowest levels of understanding dropped to 15% and the proportion of students indicating the highest levels of understanding or engagement increased to 57%.

Figure 1. Pre-post scores for survey question 1. Sample size for Fall 22 is 2,452 students and sample size for Winter 23 is 1,176 students.

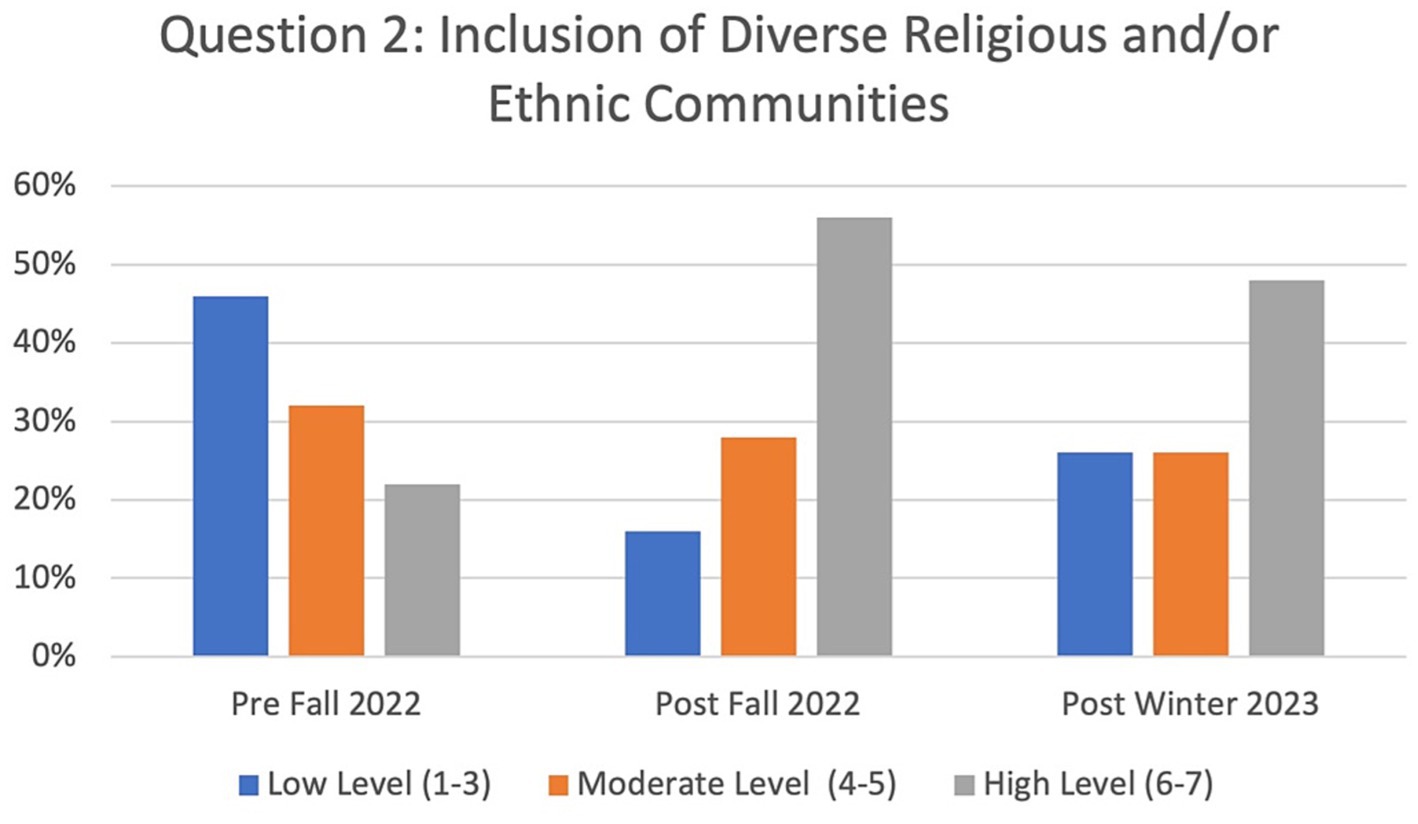

3.1.2 Inclusion of diverse religious and/or ethnic communities

The second multiple choice question addressed the inclusion of diverse religious and ethnic communities in society. Regional conflict has displaced millions of people from their homes, and teachers have reported the topic of refugees has become a flashpoint for conflict across all sectors of society. Teachers reported tensions between refugee and host communities, and refugees are regularly segregated or discriminated against. Fear or mistrust of “outsiders,” perceived competition over resources, including international aid, employment, or other support, and inflammatory political rhetoric exacerbate tensions. The survey question assessed how conceptual learning on pluralism informed their response to and inclusion of refugees who hold different beliefs in their community. The question stated: “Several refugees moved into your community. They practice their beliefs differently from you and they have different ways of expressing themselves through their clothes, food, and celebrations. Some of your friends think they are dangerous and do not want them in your community. How do you respond?”

Overall, 67% of students showed a positive move in understanding of inclusion of diverse religious and ethnic communities (see Figure 2). In the pre-survey, nearly half of students indicated the lowest levels of understanding of pluralism and associated rights, 32% of students indicated moderate levels of understanding, and less than one quarter of students indicated the highest levels of understanding or engagement. Following the Fall 2022 lesson, the proportion of students indicating the highest levels of understanding more than doubled to 56%. The proportion of students reflecting the lowest levels of understanding or engagement dropped to 16%. Following the Winter 2023 lesson, the proportion of students reflecting the highest levels of understanding was 48% and the proportion of students indicating the lowest levels of understanding was 26%.

Figure 2. Pre-post scores for survey question 2. Sample size for Fall 22 is 2,452 students and sample size for Winter 23 is 1,176 students.

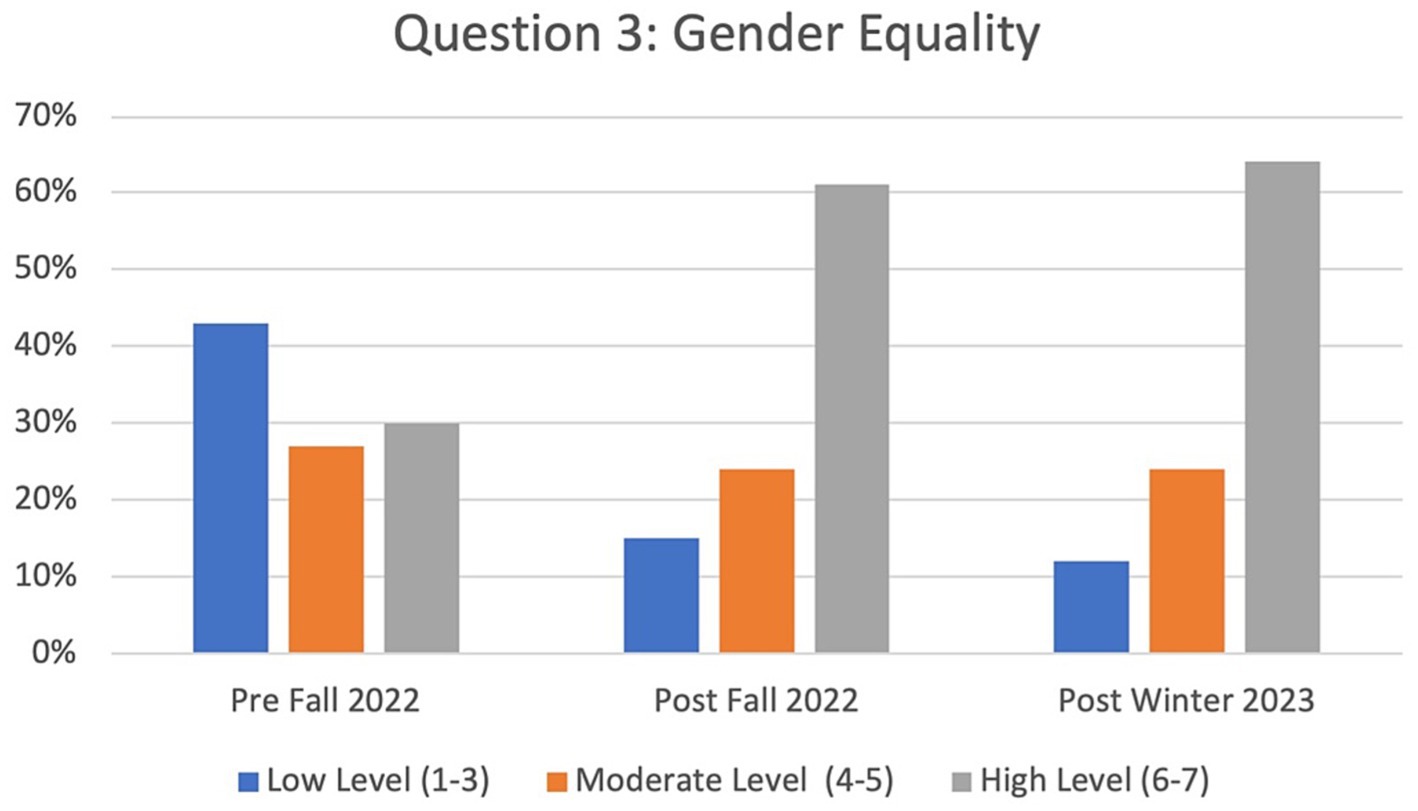

3.1.3 Gender equality

The third multiple choice question addressed gender equality and non-discrimination in the classroom. Despite significant strides made toward gender equality, the MENA region “has made the slowest progress on gender equality across multiple indicators and indices” (UNICEF, 2021). Cultural preference and socioeconomic conditions affect education and employment for women, particularly in rural areas. Teachers have reported that girls are removed from school due to financial constraints, concern for their security, or in favor of domestic production. Despite broad advances made in gender equality, equal access to education and opportunities for women and girls nevertheless can be perceived as controversial. The survey question assessed how conceptual learning about pluralism informed student understanding of gender equality and non-discrimination as associated rights. The question stated: “Someone in the government thinks that girls should be excluded from science and technology courses at your school because boys are stronger in these fields. What do you think?”

Overall, 65% of students showed a positive move in understanding of gender equality (see Figure 3). In the pre-survey, nearly 43% of students reflected the lowest levels of understanding of gender equality and non-discrimination, 27% of students indicated moderate levels of understanding, and 30% of students indicating the most sophisticated levels of understanding. Following the Fall 2022 lesson, the proportion of students reflecting the lowest levels of understanding dropped by more than half to 15%. The proportion of students indicating the highest levels of understanding doubled to reach 61%. Following the Winter 2023 lesson, the proportion of students reflecting the most sophisticated levels of understanding reached 64%, and the proportion of students reflecting the lowest levels of understanding dropped to 12%.

Figure 3. Pre-post scores for survey question 3. Sample size for Fall 22 is 2,452 students and sample size for Winter 23 is 1,176 students.

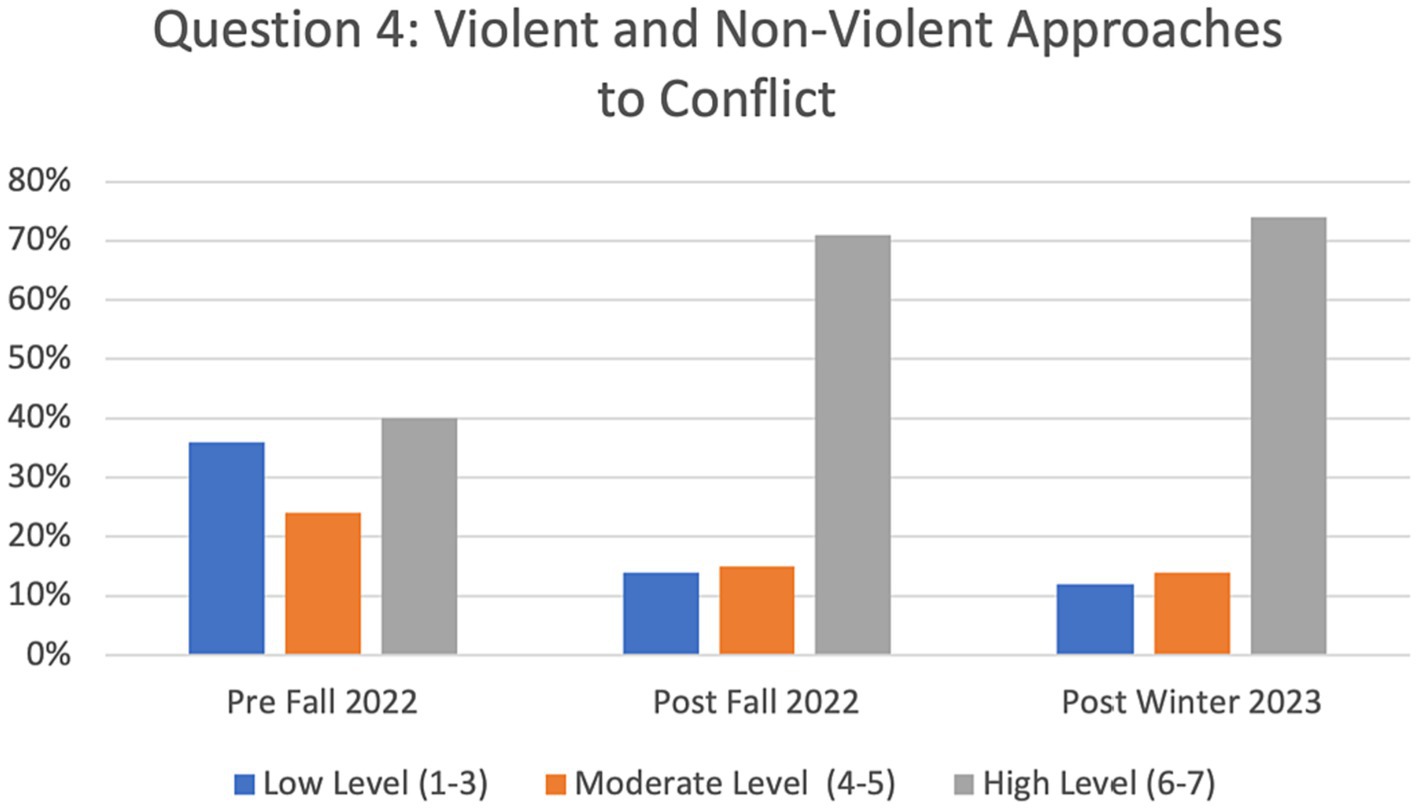

3.1.4 Violent and non-violent approaches to conflict

The final multiple-choice question addressed the use of violence in response to conflict. This issue is a particular concern in Mosul and the Nineveh Plains because of the influence of ISIS on youth in the region. Teachers have observed varied responses to the occupation of ISIS from students. Some students, themselves subjected to violence at the hands of ISIS, reject violence altogether. Other students who shared the same experience under ISIS express strong desires for retaliation and retribution. The third and most concerning group of students are those who lived under ISIS or supported the group and share their violent ideology. In conflict-affected contexts, discussion about violent or non-violent approaches to conflict can exacerbate tensions (Abboud and Dbouk, 2022). Students and teachers must confront their own experience with conflict as well as their understanding of justice, including whether and by whom it will be carried out. The survey question assessed how conceptual learning about pluralism and associated rights informed student approaches to conflict resolution, particularly when they or a member of their community was subjected to discrimination and injustice. It also assessed how students respond to groupthink promoting violence, which is often reflected in social media or other forms of communication with peers. The question stated: “Some new kids at school hit one of your friends because he was wearing a religious symbol they did not like. Some of your friends want to retaliate. How do you respond?”

Overall, 61% of students showed a positive move in understanding of non-violent approaches to conflict (see Figure 4). In the pre-survey, more than one-third of students indicated the lowest levels of understanding and favored more violent responses to conflict, nearly one-quarter of students indicated moderate levels of understanding, and nearly 40% of students indicated the most sophisticated, and non-violent, levels of understanding. Following the Fall 2022 lesson, the proportion of students advocating for violent responses to conflict decreased by more than half to 14%. The proportion of students reflecting the highest levels of understanding reached 71%. Following the Winter 2023 lesson, the proportion of students reflecting the lowest levels of understanding dropped to 12%, and nearly three-quarters of students reflected the most sophisticated and non-violent responses.

Figure 4. Pre-post scores for survey question 4. Sample size for Fall 22 is 2,452 students and sample size for Winter 23 is 1,176 students.

3.1.5 Interview and observation findings

Other broader changes in both teachers’ and students’ understanding, attitudes and behaviors were observed and documented by trainers and teachers through semi-structured interviews conducted at the conclusion of the program and observations documented during training and activity implementation. These changes reflect ongoing cycles of conceptual change that took place during the program and through further engagement with the curriculum and colleagues and/or classmates in their classrooms and communities.

Students demonstrated an increased willingness to express their opinions and beliefs about culturally and religiously sensitive practices. One student reported she wore the hijab due to community and peer pressure rather than her own choice. Through the program, she understood her personal right to express her religious beliefs according to her conscience, and she reported she was able to express her beliefs to others with confidence. She reported the program gave her “tools to defend [her] beliefs courageously and to speak up and contribute to peace within our school.”

Moreover, teachers and students demonstrated increased understanding of and respect for diverse religious beliefs, particularly among those who supported intolerant or violent approaches to conflict. A Master-Trainer reported significant conceptual change in a teacher who previously supported ISIS. At the beginning of the training, the teacher stated that the development of laws to govern the community were not necessary because the Quran — the religious text of Islam — includes every law needed to live. Through the training, he recognized his beliefs did not consider the rights and beliefs of others. At the end of the training, he stated, “I should always consider that there are people who have different references and that not all are the same.”

Overall, teachers reported a decrease in fear and mistrust among students. A teacher reported observable changes among students who participated in the lesson, stating, “I was able to help students reduce their fears of others. Then, I observed how students transferred the concepts they learned into their daily behaviors. My students became more accepting of people who were diverse in race, ethnicity, religion, or appearance.” Another teacher implemented the lesson with a group of students whose parents supported ISIS and students whose parents fought against ISIS. Through the lesson, these students were encouraged to interact with one another in mixed small groups. At the beginning of the lesson, the children of ISIS supporters did not participate and the children whose parents did not support ISIS sought to impose their opinions on their silent peers. But as the lesson progressed and the students discussed key concepts, their interaction became more inclusive of all group members. Students with no family connection to ISIS actively sought to collaborate with the other students to build peace and understanding. Similarly, the children of ISIS supporters began to share their perspective and opinions.

Interview and observation data suggested students became more respectful of others, not only in relation to pluralism and associated rights, but in relation to broader differences observed in the community. One teacher reported the lessons positively contributed to a culture of respect for students with physical and/or learning disabilities. He stated, “Pluralism is not only about people with different religious backgrounds; it is about people with different abilities and backgrounds… [The lessons] showed the school and community that stereotypes are wrong and that everyone should be respected for [who he or she] is.”

Master-Trainers reported education about pluralism and associated rights effectively countered intolerant ideologies that have historically fomented conflict between community members in the region. One Master-Trainer stated:

“We have been able to bring [pluralism] into discussion and that was a very big challenge. Creating and developing this mindset is not easy where I live, but it certainly is not impossible. It takes time, and there is still a further need to keep this work going. We have addressed the child, the teacher, the family, and the community, but we must keep going to reach every household in the region. Radicalization is a disease that can never be completely eradicated, but we must always fight against it.”

This is significant in this particular conflict-affected and geographic context, as teachers and students in the study were directly affected by the violence of ISIS.

4 Discussion

We set out to evaluate the impact of conceptual change pedagogy on student attitudes and behaviors toward key concepts inherent to pluralism and associated rights that are perceived as controversial or sensitive in their cultural context. We evaluated pre-post survey data from 2,452 students in the fall 2022 term and 1,176 students in the winter 2023 term. Due to administrative challenges, not all teachers were able to complete a second lessons during the data collection period, and thus fewer students were evaluated in the winter 2023 term. We documented statistically significant developments in students’ conceptual understanding of key concepts inherent to controversial topics relating to pluralism and associated rights, including: respect for diversity in expression inclusion of diverse religious and/or ethnic communities, gender equality, and violent or non-violent approaches to conflict. Interviews and observations provide additional context on impact of the conceptual change process on individual and collective attitudes and behaviors.

The findings indicate that even one lesson can instigate significant conceptual change in student understanding of controversial topics inherent to pluralism and associated rights. Pre-post survey responses following the fall 2022 lesson indicate significant conceptual change in students’ understanding of key concepts relating to pluralism and associated rights. No curriculum reforms were required. Teachers implemented lessons alongside their standard curricula and integrated the skills they learned through the training in their broader approaches to discussion and interaction with students. In this way, the training allowed teachers to integrate the program into the classroom.

Conceptual learning about pluralism has a positive impact on student perceptions, attitudes, and behavior toward diverse rights, including those related to gender, ethnicity, religion, and nationality. While lessons did not teach explicitly about specific rights or values, conceptual learning on pluralism and the inherent dignity of individuals informed how students approached controversial topics, specifically in the way they viewed the rights and freedoms of others to live according to their conscience. Previous research supports this finding. In a program implemented in Lebanon from 2017–2018, teachers reported lessons on pluralism allowed students to speak openly and honestly about sensitive or controversial topics, including the rights of women and girls, individuals of different sexual orientations, and ethnic minority groups (Rea-Ramirez and Ramirez, 2018).

Conceptual change — specifically about the inherent rights of all people — has a positive impact on students’ behaviors toward others. Pre-post survey answer choices reflect various responses students can have toward others in settings including sensitive or controversial topics. Responses reflecting low levels of understanding also demonstrate the most severe or antagonistic behavior, including responding with violence or discrimination. Responses reflecting moderate levels of understanding demonstrate isolated behaviors, with students opting to separate themselves from members of other groups or only interact with people who share their personal associations. Responses reflecting sophisticated levels of understanding demonstrate the most inclusive and empathetic behavior as students choose to bridge divides with whom they disagree to find mutual understanding and/or respect, even when they disagree. These observations are also reflected in interview and observational data, as Master-Trainers and teachers observed changes in the way students engaged with one another in classroom or school settings. It is important to note that the objective of the program was not to change students’ personal beliefs, particularly concerning religious, cultural, political, or social identities or convictions. Anecdotally, students have acknowledged that increased conceptual learning about pluralism and associated rights actually increased their confidence in their own beliefs and convictions because they understood their individual right to hold them. Rather, students’ perceptions of and attitudes toward others shifted in the conceptual change process as they identified and explored the biases, fears, and/or misconceptions they had about others that motivated their interactions. This suggests that, as students experience conceptual change about the inherent rights of all people, they demonstrate more respectful and empathetic behavior toward them, even when they hold conflicting or opposing views about controversial or sensitive topics.

The impact of education on pluralism on such diverse cultural topics also indicates the program can be adapted to diverse educational settings. Conceptual learning on pluralism creates an environment in which the issues most pertinent to learners can be introduced and discussed. It is not necessary to develop curricula addressing specific controversial topics, as discussion about key concepts inherent to pluralism and associated rights invites teachers and learners to consider issues that most directly affect their communities. It can also be applied to diverse learning environments, as reflected in the mixed religion-single religion and mixed gender-single gender classroom compositions represented in this study. This finding is further reflected in the expansion of Hardwired’s program across the region. Hardwired presented the impact of the program assessed in this study to the Ministry of Education for the Kurdistan Regional Government in northern Iraq and was subsequently invited to expand the program across the region.

Moreover, comparison of post-surveys from the fall 2022 lesson implementation to the winter 2023 lesson implementation show students’ conceptual learning about key concepts was maintained or increased as teachers developed more experience in conceptual change pedagogy. Pre-post survey data evaluated the impact of two cycles of conceptual change on students through two lessons. In three of the four survey questions evaluated, students completing the lesson in Winter 2023 illustrated additional conceptual change in pre-post survey results. The exception was a question relating to the integration of refugees into the community. As noted in the previous section, the issue of refugee integration is a highly controversial topic; it relates not only to pluralism, but to concerns about political influence, access to resources, and security. Further data is needed to assess why students who completed the winter 2023 lesson reflected overall lower levels of understanding on this question compared the post fall 2022 survey results. Students’ own refugee status and geographic proximity to other refugees as well as political or social discourse concerning refugees at the time may have influenced their responses. The inconsistent structure between the pre-post survey and the interview limited our ability to further assess these findings through interviews, which would have provided valuable insight to this end. These findings also suggest that ongoing training of teachers will increase the impact of lessons on students, particularly as teachers gain more experience navigating activities and discussion around key concepts and related controversial topics.

The research findings also suggest that conceptual change pedagogy effectively allowed teachers and students to explore controversial topics inherent to pluralism and associated in a constructive and supportive environment with no reported hostility from teachers, students, school administrators or community members. This suggests an optimal level of dissonance was created through the lessons, as students were challenged enough to demonstrate significant conceptual learning but not challenged so much as to elicit resistance or hostility toward the concepts introduced. Similarly, teachers and schools responded positively to the lessons and their impact on students. Teachers reported that parents who initially responded to activities with resistance or concerns ultimately became supportive of them after reviewing the content and observing the impact of activities on their children. This was further documented when we attended community events hosted by participating schools and interviewed parents about the impact of the program on the community. This finding suggests conceptual change pedagogy about pluralism can be applied successfully to controversial topics in diverse cultural environments, including those contexts in which key concepts inherent to pluralism may be perceived as threatening. Previous studies have supported this finding, as students who experienced conceptual change in their understanding of pluralism and associated rights have demonstrated more confidence in their own convictions and beliefs while at the same time respecting the rights of others to do the same, even when they disagree (Smith et al., 2017; Rea-Ramirez et al., 2020a,b; Abboud and Dbouk, 2022).

Additional research can further investigate the impact of conceptual change pedagogy on education about controversial topics. As noted previously, interviews and observations conducted in this study were structured to evaluate student responses to specific topics addressed in the pre-post survey but were not effectively administered by teachers. This data would provide important context for how specific aspects of the program curriculum supported conceptual change about topics addressed on the survey as well as other topics or issues of particular interest or priority for educators and students. In this way, pluralism education can provide a safe environment in which controversial or sensitive topics of interest within a classroom or community can be identified and pursued. Further training on monitoring and evaluation methodology is required for Master Trainers and teachers alike to produce results for such a study. Additionally, study of the effect of the training and pedagogy on teachers and students in environments with different conflict, social, or political contexts and/or different geographic regions will provide more insight on the impact of the program in diverse environments, and therefore inform its applicability to other conflict-affected environments and regions.

5 Conclusion

This study assesses the effect of conceptual change pedagogy on students’ attitudes toward pluralism and related rights within culturally sensitive contexts. The findings show conceptual change pedagogy can have a significant impact on student attitudes and behaviors toward key concepts inherent to pluralism and associated rights. Educators trained in the pedagogy were able to teach students about key concepts perceived as controversial in their social and/or cultural context. Importantly, teachers were able to navigate and address controversial topics in a way that instigated positive developments in students’ attitudes and behaviors toward pluralism and associated rights without higher level education reforms or other initiatives that historically had varied levels of success. We documented significant conceptual change among students about key concepts inherent to pluralism and associated rights after one lesson. Conceptual learning about pluralism had a positive impact on student perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward diverse rights, including those related to gender, ethnicity, religion, and nationality. The impact of education on pluralism on such diverse cultural topics also indicates the program can be adapted to diverse educational settings. Conceptual change pedagogy effectively allowed teachers and students to explore controversial topics inherent to pluralism and associated rights in a constructive and supportive environment with no reported hostility from teachers, students, school administrators or community members. These efforts were also accepted by regional government officials, as demonstrated by Hardwired’s formal partnership with the regional Directorate of Education, as well as parents and community members. To this end, the pedagogy and program developed by Hardwired successfully filled a need observed in previous efforts to address issues relating to pluralism in conflict-affected environments. Further research is needed to assess the impact of the program in other conflict-affected and geographic contexts, but the study suggests conceptual change pedagogy on pluralism and associated rights is a promising approach to education about controversial topics that can support a culture of respect for diverse perspectives and opinions in culturally-sensitive environments.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because we partnered with the Regional Directorate of Education to conduct the research. The Directorate reviewed and approved activities and data collection methods prior to the study. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The Regional Directorate of Education for Mosul, Iraq waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because activities implemented the classroom were part of the educational curriculum.

Author contributions

MR-R: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology. LA: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Hardwired Global’s Teacher-Training program in Mosul and the Nineveh Plains region of Iraq was funded through the Templeton Religion Trust from 2019-2020 and 2021-2023.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the regional Directorate of Education for Mosul and the Nineveh Plains in Iraq as well as the teachers, trainers, schools, and students who participated in the program assessed in this study. We would also like to thank the Templeton Religion Trust and Stirling Foundation for their generous support of the training and implementation of activities evaluated in the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abboud, L., and Dbouk, Z. (2022). Classroom and community transformation through education in post-conflict Iraq. J Middle Eastern Politics & Policy, 12–16.

BBC News. (2018). “Islamic state and the crisis in Iraq and Syria in maps.” Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-27838034

Brown, D. E., and Clement, J. (1989). Overcoming misconceptions via analogical reasoning: abstract transfer versus explanatory model construction. Instr. Sci. 18, 237–261. doi: 10.1007/BF00118013

Center for Preventative Action (2023). Instability in Iraq. Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/political-instability-iraq

Chan, C., Burtis, J., and Bereiter, C. (1997). Knowledge building as a mediator of conflict in conceptual change. Cogn. Instr. 15, 1–40. doi: 10.1207/s1532690xci1501_1

Chi, M. T., Slotta, J. D., and De Leeuw, N. (1994). From things to processes: a theory of conceptual change for learning science concepts. Learn. Instruct. 4, 27–43. doi: 10.1016/0959-4752(94)90017-5

Clement, J. (2013). Roles for explanatory models and analogies in conceptual change. Intern Handbook of Res Conceptual Change. doi: 10.4324/9780203154472.CH22

Clement, J., Brown, D., and Zietsman, A. (1989). Not all preconceptions are misconceptions: finding "anchoring conceptions" for grounding instruction on students’ intuitions. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 11, 554–565. doi: 10.1080/0950069890110507

Glynn, S. (1995). Learning science meaningfully: Constructing conceptual models. Learning science in the schools: research reforming practice. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Heddy, B. C., Taasoobshirazi, G., Chancey, J. B., and Danielson, R. W. (2018). Developing and validating a conceptual change cognitive engagement instrument. Front Educ (Lausanne) 3:43. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00043

Hewson, M. G., and Hewson, P. W. (1983). Effect of instruction using students' prior knowledge and conceptual change strategies on science learning. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 20, 731–743. doi: 10.1002/tea.3660200804

Kitayama, S., and Tompson, S. (2015). A biosocial model of affective decision making: implications for dissonance, motivation, and culture. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 52, 71–137. doi: 10.1016/bs.aesp.2015.04.001

Marrakech Declaration. Marrakesh declaration on the rights of religious minorities in predominantly Muslim majority communities (2016). Available at: https://www.rfp.org/resources/marrakesh-declaration-on-the-rights-of-religious-minorities-in-predominantly-muslim-majority-communities/

Mason, L. (1994). Cognitive and metacognitive aspects in conceptual change by analogy. Instr. Sci. 22, 157–187. doi: 10.1007/BF00892241

Rea-Ramirez, M. A. (2008) in An instructional model derived from model construction and criticism theory. Model based learning and instruction in science. eds. J. Clement and M. A. Rea-Ramirez (Dordrecht: Springer), 23–43.

Rea-Ramirez, M. A., and Clement, J. (1998). In Search of Dissonance: The Evolution of Dissonance in Conceptual Change Theory. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching (71st, San Diego, CA, April 19-22, 1998). ERIC Document ED41798.

Rea-Ramirez, M. A., and Ramirez, T. (2018). Changing attitudes, changing behaviors: conceptual change as a model for teaching freedom of religion or belief. J Soc Sci Educ 4, 85–97.

Rea-Ramirez, M. A., Ramirez, T., and Abboud, L. (2020a). Becoming a human rights master trainer: the journey. Intern J Arts and Soc Sci 3 Available at: www.ijassjournal.com

Rea-Ramirez, M. A., Ramirez, T., and Abboud, L. (2020b). Promoting pluralism and peaceful coexistence through a master trainer program. Intern J Arts and Soc Sci 3 Available at: www.ijassjournal.com

Recco, R. (2018). Why we need controversy in our classrooms. EdSurge Available at: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2018-01-17-why-we-need-controversy-in-our-classrooms#:~:text=We%20Need%20to%20Teach%20Students%20How%20to%20Respectfully%20Disagree&text=Students%20need%20to%20debate%20things,to%20learn%2C%20not%20as%20invalidation

Smith, L., Ramirez, T., and Rea-Ramirez, M.A. (2017). Protecting children from violent extremism: Using rights-based education to build more peaceful, inclusive societies in the Middle East and North Africa. Available at: https://hardwiredglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hardwired-Report-Draft-29-May-single-page-scroll-reduced.pdf

UN News. (2016). “UN human rights panel concludes ISIL is committing genocide against Yazidis.” Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2016/06/532312

UNICEF. (2021). Situational analysis of women and girls in the Middle East and North Africa: A decade review 2010–2020. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/mena/reports/situational-analysis-women-and-girls-middle-east-and-north-africa

United Nations (2019). A child-resilience approach to preventing violent extremism. United Nations Office of the SRSG on Violence against Children. Available at: https://violenceagainstchildren.un.org/news/child-resilience-approach-preventing-violent-extremism

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (2012). The Rabat plan of action. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/outcome-documents/rabat-plan-action

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2017). Beirut declaration and its 18 commitments on faith for rights. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Press/Faith4Rights.pdf

Keywords: pluralism education, controversial topics in education, conceptual change, human rights education, gender equality, post-conflict education

Citation: Rea-Ramirez MA, Abboud L and Ramirez T (2023) Evaluating the impact of conceptual change pedagogy on student attitudes and behaviors toward controversial topics in Iraq. Front. Educ. 8:1278231. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1278231

Edited by:

Esther Sanz De La Cal, University of Burgos, SpainReviewed by:

Almudena Alonso-Centeno, University of Burgos, SpainAsma Belmekki, University of Khenchela, Algeria

Copyright © 2023 Rea-Ramirez, Abboud and Ramirez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lena Abboud, bGVuYUBoYXJkd2lyZWRnbG9iYWwub3Jn

Mary Anne Rea-Ramirez1,2

Mary Anne Rea-Ramirez1,2 Lena Abboud

Lena Abboud