- English Language Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted the educational sector, leading to profound changes in teachers’ roles and identities. While these disruptions have been challenging, they also offer a unique opportunity for teachers to redefine and evolve their traditional roles and practices. This study, grounded in the poststructuralist perspective of teacher identity, investigates the impact of COVID-19 on the professional identities of seven EFL teachers at a Saudi university post-school reopening. Mezirow’s Transformative Learning framework was utilized to trace the transformations of teachers’ identities, with the pandemic serving as the catalyst for reflection and change. Teachers’ experiences were captured using narrative inquiry and Life Story Interviews, and analyzed via reflexive thematic analysis with an emphasis on professional agency as a conceptual lens. The analysis revealed three key dynamics that characterized the transformation in professional identity during these times: delegitimization, reconstruction, and empowerment. These insights contribute to the teacher education literature by offering a nuanced understanding of identity transformation and by proposing strategies to support teacher identity development in challenging contexts.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted education globally through school closures and emergency shifts from traditional face-to-face (f2f henceforth) to virtual mode, causing disruptions in maintaining quality teaching and learning. As has occurred in many countries, Saudi Arabian schools and universities responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 with an immediate lockdown and school closure. This has entailed the emergency shift to the virtual modes of education that remained throughout the academic year 2019–2021. The transition was challenging and further exacerbated by the shifts in teachers’ “normal” roles and responsibilities as they were encouraged to maintain quality teaching in the unprecedented remote and virtual situation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been widely viewed as a transformative event in contemporary educational research, often described as a “game changer” (Harris and Jones, 2020) and a “black swan event” (Harford, 2021). During this period, teachers felt enormous pressure, both intellectually and emotionally, as they wrestled with the difficulties of adapting to this new way of teaching (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2021) while integrating new digital technologies into their pedagogies (Farrell and Sugrue, 2021).

Extensive literature has examined the myriad of disruptions and shifts faced by teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Cutri et al., 2020; Harris and Jones, 2020; Kim and Asbury, 2020; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2021; Yuan and Liu, 2021; Mellon, 2022; Ramakrishna and Singh, 2022; Song, 2022). Despite the huge disruptions they experienced while delivering inclusive education, many scholars have also underscored the opportunities that emerged, enabling teachers to create new teaching strategies, unpack their view of teaching, and reconstruct their identity during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kim and Asbury, 2020; Zhang, 2021; Mellon, 2022; Zhang and Hwang, 2023). Nevertheless, there has been a paucity of research on the way in which teachers negotiate internally with themselves and externally with the changed educational setting post the COVID-19 pandemic to develop their professional identity. Moreover, voices from university teachers regarding the transformations in their experiences post-school reopening have been overlooked. This study aims to address these gaps by examining the nuanced internal processes of the transformation in the professional identity of English as a foreign language (EFL) teacher in a Saudi university post the pandemic. Since the current study views COVID-19 as a disorienting dilemma with multiple challenges and possibilities for teachers’ sustainability and professional growth, investigating transformations in teachers’ identity post-pandemic serves as an analytical lens to interpret the ways in which teachers develop as professionals as they interact with the changing context, offering insights for future sustainable change.

Literature review

Language teacher identity

Language teacher identity (LTI) has increasingly received scholarly attention in teacher education literature. Despite its growing centrality in teacher education, agreement on the meaning and breadth of teacher identity remains unresolved. Teacher identity is defined differently based on the lens through which it is viewed (Beijaard et al., 2004). In a broader sense, LTI refers to “the way language teachers see themselves and understand who they are in relation to the work they do. It is also the way others, including their colleagues and students and institutions, see them” (Barkhuizen, 2021, p. 549). This definition implies that teacher identity involves conscious self-awareness, knowledge, and deliberateness, with teachers actively participating in their own development (Beijaard et al., 2004).

Contemporary theories on professional identity, however, add to their complexity by arguing that teachers’ identities are intricately intertwined with their surrounding contexts. This viewpoint asserts that identity development is influenced by the opportunities and constraints afforded by social and physical contexts (Bukor, 2015; Pennington and Richards, 2016; Yazan, 2018). Consequently, LTI is described as a composite of teacher learning, teacher cognition, teachers’ participation in communities of practice, contextual factors, teacher biographies, and emotion (Yazan, 2018). These descriptions align with a poststructuralist perspective, wherein identity is viewed as multifaceted, complex, socially constructed, and a site of struggle that shifts across time and space (Norton, 2013; Song, 2016), illuminating the possibility of deliberate influence (Varghese et al., 2016). In this regard, teacher identity is both a product and a process that is bound to the social, cultural, institutional, and individual factors within a given context. The current study adopts Ruohotie-Lyhty (2018) definition of teacher identity development as “a process in which teachers develop their identities to better match the environmental conditions and to develop professionally” (p. 29). The environmental conditions in this study are viewed in terms of transformations in the teaching context after schools reopened post the COVID-19 pandemic.

The significance of researching LTI development lies in its perceived pivotal role in teachers’ professional growth. Advocates argue that LTI can serve as an organizing element to teachers’ professional trajectory (Beauchamp and Thomas, 2009; Van Lankveld et al., 2021), and an overarching framework that guides teachers to “construct their own ideas of ‘how to be’, ‘how to act’ and ‘how to understand’ their work and their place in society” (Sachs, 2005, p. 15). The main argument here is that teacher identity offers an analytical tool for teachers to dialectically construct their beliefs about teacher selves and understand the teaching profession, as well as a basis for their pedagogical decisions and meaning-making in the classroom. Additionally, it is postulated that LTI enacts “an integral part of teacher learning” (Tsui, 2011, p. 33), and that LTI development is even coined with language teacher education itself (Varghese et al., 2016; De Costa and Norton, 2017; Yazan, 2018). This position is consistent with contemporary sociocultural orientations in teacher education, which emphasize “teacher knowledge not as an isolated set of cognitive abilities but as fundamentally linked to matters such as teacher identity and teacher development” (Johnston et al., 2013, pp. 53–54). Hence, teacher development entails developing a new identity rather than merely acquiring new teaching techniques and knowledge (Clarke, 2008), while expanding self-understanding is a part of teacher identity development (Kanno and Stuart, 2011). Thus, it becomes evident that teachers’ learning and identity transformations are closely intertwined factors, which together underpin their professional growth (Kelchtermans, 2009; Yazan, 2018).

Despite the burgeoning body of teacher identity development literature over the past decade, it is crucial to evaluate the focus of existing research. A substantial majority of language teacher professional identity studies focus on preservice teachers and new practitioners (Haniford, 2010; Hong, 2010; Timoštšuk and Ugaste, 2010; Thomas and Beauchamp, 2011; Barkhuizen, 2016), whereas a significant gap remains in our understanding of in-service language teacher identity development, especially in the context of change (Buchanan, 2015). Therefore, there is a need for robust empirical evidence of how teachers develop and transform their identities within educational change, as this could significantly inform teacher education. To better comprehend the temporal aspect and development in teacher identity during the educational change, this study reports on seven EFL teachers’ narratives of their experiences post the pandemic and conceptualizes the ways in which the participant teachers transformed and reshaped their professional identity.

Teacher identity during the pandemic

COVID-19 and the accompanying school closures resulted in a highly fragmented educational context that prioritized digital solutions (Kim et al., 2022). Amid this educational crisis, a discernible transformation in teacher identity was an emergent theme in research that explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast to their former roles as proactive and agency-driven, teachers found themselves “invisible” (Xu and Huang, 2021, p. 107), marginalized (Song, 2022), and “disembodied and depersonalized purveyors of education” (Watermeyer et al., 2021, p. 632). This resulted from the limited control teachers had over the reform as teaching was transformed into “‘easily automated’ practice” (Watermeyer et al., 2021, p. 632). Other studies have examined the transformations in teacher identity focusing on teachers’ emotions and experiences of vulnerability, anxiety, coping strategies, engagement, readiness, and self-confidence (Cutri et al., 2020; Kim and Asbury, 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2022; Mellon, 2022; Song, 2022). These studies, however, highlighted this pandemic teacher-self as a “complex quilt, patching together concern for the self, concern for one’s teaching values or commitments, and concerns for one’s community” (Jones and Kessler, 2020, p. 7).

Despite the burgeoning pandemic teacher identity research in the past 3 years, research on the long-term transformation and development of LTI is lacking. Existing research has predominantly focused on LTI transformation while transitioning to online education. For example, Ashton (2022) investigated teacher agency with respect to digital affordances and restrictions, revealing a nuanced interplay between agency and professional identity, with structural factors playing a significant role. This body of research postulated changes to teacher education programs to better prepare teachers for diverse teaching contexts. In a similar vein, Yuan and Liu (2021) analyzed the evolution of the identities of three EFL teachers within a Chinese university while teaching online, uncovering transformations from an imagined identity to a pragmatic identity depending on the virtual space and resources. From a different but relative standpoint, El-Soussi (2022) discerningly examined the shifts in the professional identity of four EFL teachers at UAE universities that resulted from the changes in teaching beliefs and practices accompanying the transition to online teaching. Another flourishing line of inquiry in this domain delves on teacher resilience and identity reconstruction to adapt to the new reality. Zhang and Hwang (2023) and Zhang (2021) revealed the development of new teaching practices and a shift in their understanding of teaching, as a common practice that contributed to EFL teachers’ identity reconstruction during the COVID-19 pandemic, and further identified two types of identity reconstruction processes in the online teaching: that relate to situational context and interactional context.

These studies assert that the pandemic has undeniably forced teachers to reshape their identities as they attempt to balance their own feeling of agency with the requirements of a disrupted teaching context. They frequently emphasize the negotiation of teacher identity and agency as a basis for their identity shift and development. However, there is a notable gap in research addressing the nuanced process of identity transformation when teachers return to f2f teaching post-pandemic. Examining EFL teacher identity shifts during the transition to online teaching amidst the pandemic belied the complexity of teacher identity that is more continual and multilayered and failed to capture what the future may hold or how the pandemic will affect the teaching profession for a long time. To capitalize on the hard-learned lesson and move forward, Mellon (2022) highlighted the need to move beyond the emergency shift to online teaching and recognize the complex nature of teacher identity and the factors that influenced and may continue to influence their professional growth rather than focusing on just one part of teachers’ professional lives. The current research is intended to contribute to the existing discourse and examine teachers’ identity transformation processes and their implications for teacher education and professional development.

Teacher reflection and identity

Reflection is a key notion in understanding and performing qualitative inquiry (Creswell and Poth, 2018), and a powerful source for teachers to delve deeper into their teacher identities. Engaging in reflective practices entails a profound level of self-awareness and understanding of one’s positioning within the larger context. This, in turn, creates opportunities for self-evaluation, revisiting the “whys” and “hows” of teaching, and rigorous interrogation of one’s own perceptions of oneself and perceptions of others (Giampapa, 2011; Palaganas et al., 2017; Greene and Park, 2021). A growing body of research supports the benefits of reflexivity as a global response to the pandemic (Hollweck and Doucet, 2020; Murray et al., 2020;Greene and Park, 2021; Song, 2022). One such benefit is that reflection represents a critical lens to magnify and unfold teachers’ own sense of uncertainty, fear, and vulnerability brought to teachers’ roles and identities by the pandemic, which in turn allowed them to cope with and understand their positioning in the disrupted teaching context (Greene and Park, 2021; Song, 2022). This potential for being open and transparent about teachers’ roles and responsibilities and deliberately negotiating who they are, what they need to achieve, what pedagogical decisions they make, and why, would not only contribute to the (re)shaping of teachers’ identity but arguably enhance both their personal growth and professional transformation. Given the numerous changes and conflicts that teachers have encountered since the outbreak of the pandemic, analyzing teachers’ reflections through self-stories (McAdams, 2008) would offer valuable insights into how teachers navigate their experiences post-pandemic, and the interpretations of those events, including how they perceive their roles as teachers and reconstruct their pedagogical responsibilities. Such endeavors are crucial to legitimize teachers’ emerging identities and to foster sustainable growth in their professional trajectories.

The current study, therefore, aims to expand on the aforementioned areas of research. It is a narrative inquiry that seeks to understand how seven EFL teachers negotiated and transformed their teacher identity at a Saudi university. The significance of this study is twofold: theoretical and empirical. In terms of theory, it builds on Mezirow (2000) Transformative Learning (TL) theory and professional agency. This study, informed by these two conceptual lenses, will add to the existing research on the teacher identity post-pandemic by providing deeper and more nuanced interpretations of the teacher identity transformation and development processes during change. Furthermore, it elucidates the intricate interplay between teacher professional agency and teacher identity development. Empirically, it contributes to the emerging literature on teacher education and preparation during change by navigating the existing challenges in dealing with changes in teaching situations and potential practicalities for promoting professional growth. To meet the study’s objectives, the following research question will be addressed:

• How did the teachers negotiate and transform their teacher identity post the COVID-19 pandemic?

The theoretical framework

Transformative learning theory as identity change

Mezirow’s TL framework (1978) is deemed appropriate for the current study given that the framework’s originates from a disorienting issue that serves as an impetus for transformative learning, which was pertinent in the context of COVID-19. Rooted in the work of Kuhn (1962), Habermas (1971, 1984), Freire (1970), and many others, Mezirow (1978), a Professor of Adult Education, conceptualized transformative learning in connection to a study of US women returning to postsecondary study or the workplace after an extended time. The theory has since evolved and become prominent in the field of adult education. Mezirow (1978, 2006) defined TL as a learning process that involves transformations in the learner’s “meaning perspectives,” “frames of reference,” and “habits of mind.” He claimed that “as there are no fixed truths or totally definitive knowledge and because circumstances change, the human condition may be best understood as a contested effort to negotiate contested meanings” (Mezirow, 2000, p. 3). Exploring qualitative changes in one’s identity and self-understanding can capture the wide range of areas where TL takes place (Illeris, 2014). A central tenet of this argument is the notion of transformation as profound changes in self-consciousness associated with reconstructing a multifaceted, narrative self. Through examination and reevaluation of one’s attitudes, values, and convictions, learners are offered fresh capabilities to learn and deal with innovations, unanticipated problems, and possibilities posed by life in contemporary society. TL is thus considered to be the ultimate form of deep learning and necessitates critical reflection (Mezirow and Taylor, 2009; Illeris, 2014). Critical reflection comprises the deconstruction and reconstruction of personal beliefs, which can lead to the development of new perspectives (Mezirow and Taylor, 2009).

Illeris (2014) contributed to the discourse by developing a three-layer model of identity structure to better understand the dynamics of identity changes in light of TL. The “core identity layer” embodies the deep traits of being a unique individual with a sense of coherence. This level remains relatively stable despite numerous forces that threaten instability and fragmentation. In contrast, the “personality layer” is less stable and is influenced by how one interacts with the external world, society, and environment of which one is a part. It consists of a person’s principles, behavioral patterns, values, meanings, social distance, and sense of belonging (Illeris, 2014). The “preference layer” on the other hand, is the least stable comprising experiences and meanings that are somewhat tied to one’s identity yet are relatively malleable to change. The type of learning I am aiming for is learning that brings about transformations in teachers’ identities and roles at the personality level.

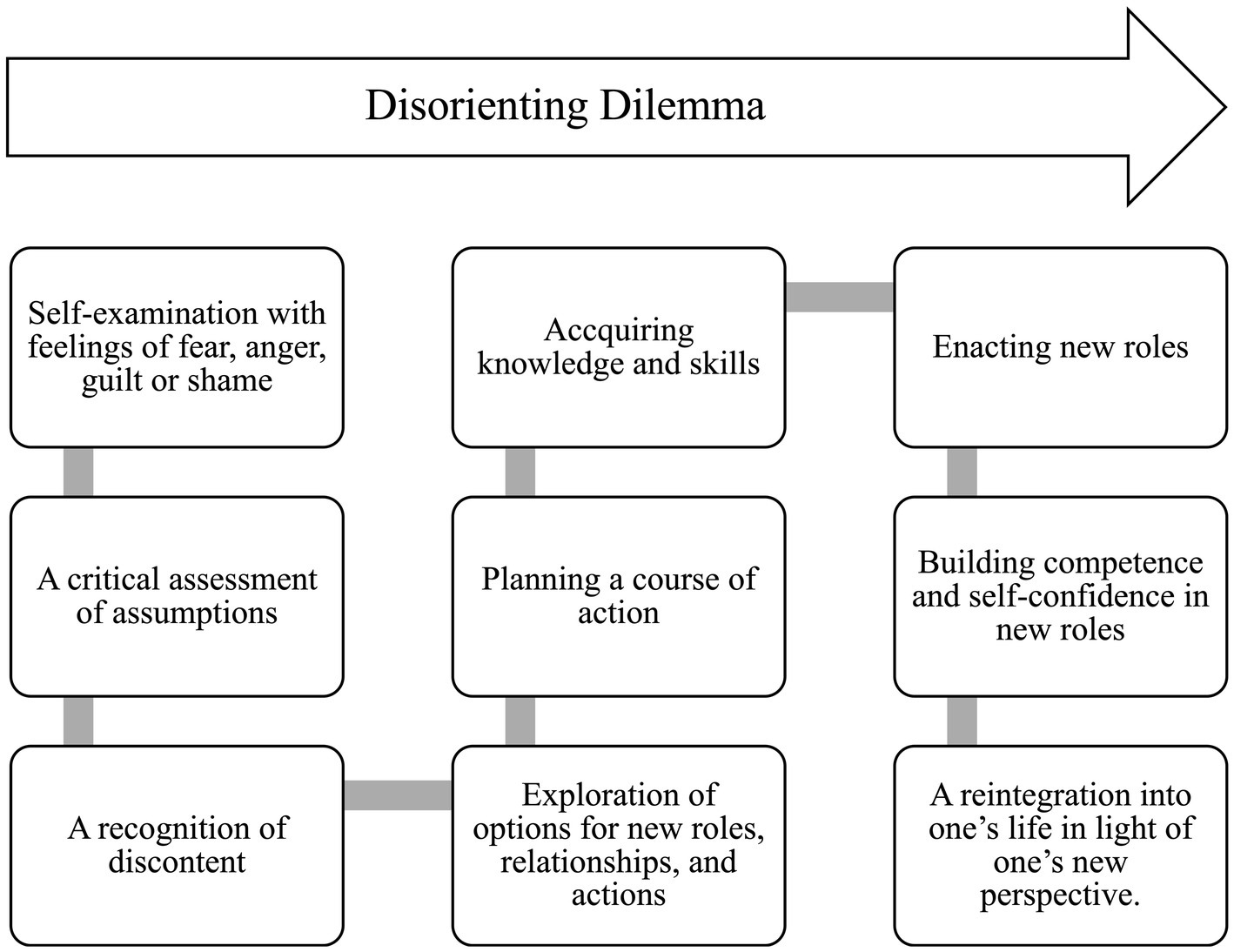

Thus, it can be assumed that Mezirow’s TL framework would offer a robust conceptual framework for the current study due to its capacity to address the profound changes in teacher identities brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. It emphasizes the significance of critical reflection and provides a comprehensive framework for navigating the complex process of identity transformation. The current study utilizes the 10-stage process that makes up Mezirow (1978) TL model which is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mezirow’s 10 stage process (adapted from Mezirow, 1978).

Professional identity development and agency

To construct a holistic picture of teachers’ identity development, I utilized a narrative approach (Polkinghorne, 1988; Bruner, 1999; Barkhuizen, 2016), which is congruent with poststructuralist identity theories that view identity as a social, multiple, and discontinuous construct (Beijaard et al., 2004; Akkerman and Meijer, 2011). This postmodern conceptualization posits that individuals can have diverse even contradictory conceptualizations of themselves that are socially situated (Akkerman and Meijer, 2011). It also portrays individuals as active agents in the development of their identities (Beijaard et al., 2004; Eteläpelto et al., 2013). This agentive act of the individuals in making sense of their experiences is the special target of the narrative approach. While acknowledging the postmodern conceptualization, this study also aligns with Akkerman and Meijer (2011) who deny the decentralized view of identity, emphasizing the need to consider issues of unity, continuity, and uniqueness in identity as well. As such, I adopt a narrative approach as a methodological lens to conceptualize the teacher identity development post-pandemic and analyze the contradictory dynamics of multiplicity and unity, discontinuity and continuity, and sociality and individuality.

Furthermore, this study delves into LTI transformation and development post-pandemic through the analytical lens of professional agency, also known as agency, the “socioculturally mediated capacity to act” (Ahearn, 2001, p. 112). Professional agency signifies that professionals (e.g., teachers) are consciously acting, exercising control, making decisions, and taking stances in relation to their work and professional identities (Lasky, 2005; Lipponen and Kumpulainen, 2011; Ketelaar et al., 2012; Eteläpelto et al., 2013). Professional agency is intricately connected with teachers’ professional identity development amid changes in two essential ways. First, the agency is necessary to drive the development of teachers’ professional identity. Professional identity is conceptualized as “a work history-based constellation of teachers’ perceptions of themselves as professional actors” (Vähäsantanen, 2015, p. 7). As teachers actively participate in a particular community, they make decisions regarding how to interact and connect with people drawing on their beliefs, ideals, and prior experiences. However, in a changing context, teachers’ current identities may be challenged, leading to a reevaluation of who they are and what type of professionals they want to be (Akkerman and Meijer, 2011). Therefore, it can be argued that agency is a means by which the negotiation and transformation of a teacher’s professional identity can be realized and conceptualized. Second, the agency is intrinsically linked to the nature of narrative identity development (Eteläpelto et al., 2013). Identity development is a process that is purposefully enacted by individuals who are invested in the reshaping of their identities (Beijaard et al., 2004; Eteläpelto et al., 2015). As teachers narrate their “self-as-teachers stories” (Ruohotie-Lyhty, 2013, p. 122), they organize and draw on experiences perceived as meaningful for teacher identity, thus exercising their agency. This narrative activity, or what Ruohotie-Lyhty (2018) called identity-agency, is crucial to teacher identity development, serving as “a ‘mediator’ that contributes to understanding the interaction between [the changing] social environment and individual identity” (Ruohotie-Lyhty, 2018, p. 5). This study seeks to unravel teachers’ identity transformation by examining how seven EFL teachers embody their identity-agency and make sense of their own professional selves in the post-COVID-19 pandemic context.

Methods and materials

Research design

In line with the theoretical framework, this study adopts a narrative qualitative design, a means to capture teachers’ lived experiences. Bruner (1987) argues that we live in a storied world and that narrative is the primary structure for making sense of experience. In this sense, stories serve as “a portal through which a person enters the world and by which their experience of the world is interpreted and made personally meaningful” (Connelly and Clandinin, 2006, p. 479). Empirical evidence supports the effectiveness of narrative inquiry, utilizing stories in examining teachers’ professional identity and agency (Ruohotie-Lyhty, 2018; Chaaban et al., 2021).

Context and participants

This study was conducted at a public university in Saudi Arabia. In the study context, the lockdown was in effect from March 2020 to August 2021. With schools reopening, faculty and students returned to the f2f teaching taking certain precautions, such as wearing masks and keeping a social distance. The teachers were recruited and interviewed in June 2022, so that they had a few months of experience returning to f2f instruction after more than a year of school closures.

A convenience sample of seven EFL female teachers at a Saudi university was recruited through email which provided access to the pool of EFL teachers at the university. A purposive sampling strategy was used to maximize data efficiency and validity (Morse and Niehaus, 2009) and select suitable EFL university teachers with the following criteria: (1) teaching experience, (2) ongoing online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown for at least one academic year, and (3) have returned to f2f teaching for at least 3 months. This would allow teachers to reflect on the transformations in their identity negotiations after the return to f2f teaching.

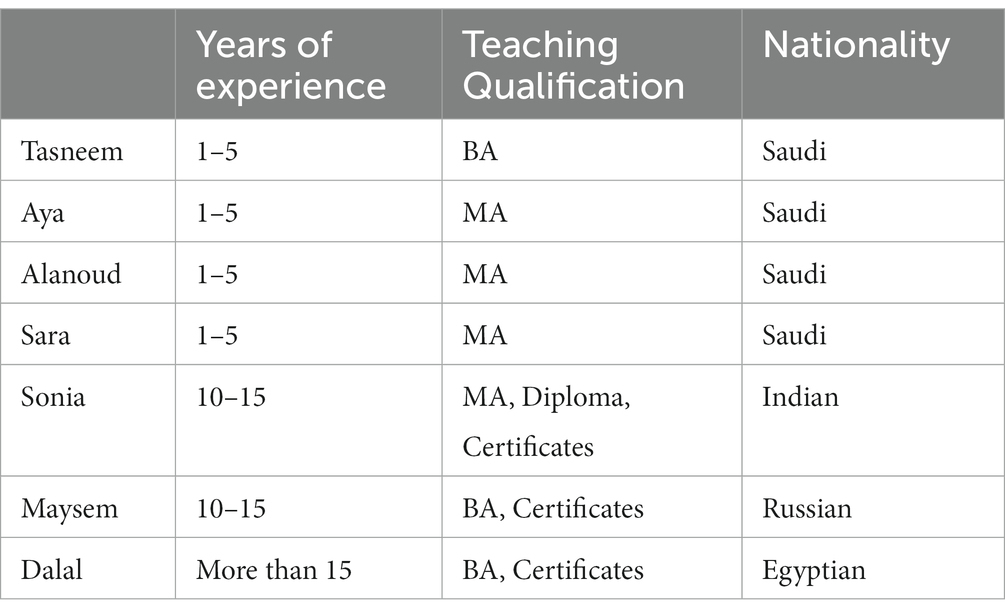

The project’s ethical approval was obtained from the researcher’s institution before any possible volunteers were recruited. I sent an email announcement to colleagues, which included an information sheet that provided details of the study’s voluntary nature and its inclusion requirements. Nine teachers volunteered to participate, however, seven only met the criteria and participated in the study. All participants reviewed and signed the informed consent form before data collection. The teachers had a range of years of experience and teaching qualifications. Table 1 provides information about the participants using pseudonyms.

Data collection

Data were collected from a semi-structured interview that was based on Section B of the LSI, as outlined by McAdams (2008). This method focuses on key scenes—a low point, a high point, and a turning point—that stand out in one’s story. These key scenes are defined as moments that hold special meaning, evoke emotions, or are unforgettable. In this context, a low point signifies an event associated with unpleasant feelings, dissatisfaction, and uncertainty while a high point denotes an event that generated positive feelings, satisfaction, and confidence. A turning point represents certain events that led to a change of perspective and a significant shift in the teachers’ roles and identities. Significant to this storytelling process is the participants’ reflection on why a particular life story event is salient for them, and whether the event is informative about who they are as teachers (McAdams, 2008). The LSI method allowed the researcher to understand how teachers make sense of their professional lives as they tell stories about noteworthy events in their post-pandemic experiences. Furthermore, this framework, with its focus on three crucial moments in teachers’ lives, offered insights into how teachers’ professional identities evolved and changed in the face of change.

Using the LSI method, the interview questions consisted of three sections, corresponding to the three scenes: low point, high point, and turning point. Participants were asked to narrate these scenes from their teaching experiences after school reopening, providing detailed descriptions and reflecting on what distinguished these scenes from others and what they might say about them as teachers. The interview schedule for this section is attached in the supplementary materials. These interviews were conducted via video conferencing, with each lasting approximately 30–45 min. The recorded interviews were transcribed, cross-checked against the audio recordings, and then anonymized by the researcher. Any personally identifiable information was removed and replaced with a broad description to ensure the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using a reflexive thematic analysis (Clarke and Braun, 2014). I took a deductive orientation to analyze the development of teachers’ professional identity, where Mezirow (2000) TL model and professional agency serve as a theoretical lens “to guide data coding and the exploration and determination of final themes for the analysis, rather than provide a predetermined structure to code the data within or test the data against” (Braun and Clarke, 2022, p.10). A degree of inductive analysis, however, was also employed to emphasize the participants’ meaning making.

I organized narratives based on the key scene model (low, high, and turning point) to navigate the transformations in teachers’ life stories. I followed multiple steps in the data analysis. First, I got myself deeply engaged with narratives and made initial observations on potential codes and themes. Next, I coded the data focusing on both the semantic and latent levels of meaning. I paid close attention to what was said and how it was said such as thrilling and vulnerable moments, realizations, and other nonverbal cues while transcribing the interviews and taking field notes that were considered in developing the initial codes. Then, I collated relevant codes in light of Mezirow (2000) TL model and professional agency to produce themes. These codes represent elements of the transformative learning process and identity negotiations including “disorienting experience,” “identity loss,” “perspective change,” and “resilience.” Afterward, I developed themes that accurately represent the process of teachers’ professional identity developmental trajectory in light of the identified codes. Last, I defined and reorganized the themes into a story to outline the meanings of the EFL teachers’ professional experiences and highlight their identity transformation post the pandemic era. It is noteworthy that the development and refinement of the themes was an ongoing process in which the codes’ positioning shuffled. Furthermore, the data were handled as a single set, and patterns were studied across the seven teachers’ experiences, yet individual differences were maintained throughout the analysis.

Trustworthiness and validity

Since both the researcher and the participants were EFL teachers at the same institution, this study faces the risk of “insider research” (Sikes and Potts, 2008). Insider studies often grapple with issues related to objectivity in data interpretation or the possibility of overlooking crucial information when data gathering (Asselin, 2003; Tshuma, 2021). To address these challenges and ensure the trustworthiness of the reflexive practice and the credibility of the data analysis, I integrated several strategies, including the member reflection process (Tracy, 2010) and journaling. Through member reflection, participants were encouraged to reflect on the concluding analysis, offering deeper insight and generating additional information about their transformative experience. This, in turn, facilitated spotting analytical gaps and the consideration of addressing them in the written report (Smith and McGannon, 2018). Additionally, I kept a journal throughout the study, documenting my justifications, opinions, and emotional reactions to the interview along with my field notes, to ensure that reflection was ongoing. These journals include my perception of my relationship with the participants and their reactions, my emotions, the flow of events in the interview, how that affected the process, and my interpretations of the data. It also encompassed questions I had, and what further explanation I required from the participants. Keeping a journal helped me to be more conscious of my positionality in the study and how I interacted with the participants and data interpretation.

Analysis

The findings of this study are organized into a story of LTI transformation. This story consists of four sections that navigate the process of identity-agency construction and how it shapes identity development. Minor typographical errors in illustrative quotations have been corrected.

COVID-19 as a disorienting dilemma

The changed contextual and social factors in the educational setting post the COVID-19 pandemic placed teachers in a disorienting dilemma. After teaching online for one and a half academic years, teachers and students returned to the f2f educational setting with some precautionary safety measures to maintain social distancing and control the virus spread. Although the seven EFL teachers expressed their excitement to return to the “normal” f2f classroom teaching post-pandemic where they could make eye contact with the students and observe their learning process, most teachers soon recognized the drastic changes brought by the pandemic. Central to their experience was “a change in students’ learning mode … they are using their phones instead of using books. The students do not want to interact. They have lost their communication skills” (Aya, personal communication, June 5, 2022). Genuine low points were associated with incidents of students’ disengagement in the class environment, reluctance to engage in class activities, and anti-socialization, which in turn, contributed to teachers’ feelings of guilt, blame, uncertainty, disappointment, and less efficacy. These jumbled feelings negatively resonated with their view of themselves as professional language teachers who could maintain quality language teaching where students are effectively engaged and willing to learn in the classroom context. Tasneem for instance reflected that “due to their [students] lack of reciprocation, I thought I’m doomed” (Tasneem, personal communication, June 5, 2022), whereas Dalal expressed, “This was really disappointing... I was a bit suffocating. It’s not me as a teacher” (Dalal, personal communication, June 15, 2022). For her, wearing a mask not only obstructed her breathing but also created a challenge in establishing effective communication between her and the students. A similar sense of discontent occurred at a juncture with teachers’ reflection of them being “muddled” (Sara), not “accepted” by students (Alanoud), and not “prepared” enough (Maysam) to teach post-pandemic as a result of students’ antilocalization in the physical classroom. It was through their interaction with the students and the changed teaching context that the teachers’ prior teaching experiences and identities were challenged, which triggered them to examine their teacher selves.

Delegitimizing identity: skepticism toward development

In stories that focused on the tension between the changed educational setting and teachers’ original identity, teachers frequently felt forced to examine their teacher selves as an essential step to respond to challenges in the changing context. Typically, the disorienting experience threw teachers into a state of skepticism, which in turn, sparked them to assess their old identity in relation to the new context as a part of their professional self-understanding as well as developing their professional identity.

As a part of the identity examination process, teachers started to be skeptical about their unquestioned assumptions about their professional identity as EFL teachers. They negotiated the changed landscape as a platform to critically reassess their “own orientation to perceiving, knowing, believing, feeling, and acting” (Mezirow, 1990, p. 13) as professionals. Teachers’ stories depict different orientations to the process of professional identity examination, which varies based on how teachers drew on their beliefs, ideals, and prior experiences as language teachers:

There is no way to hide from it. The immediate feedback that you get [from the students]. If they are upset, automatically it gets to my skin. I feel like I’m upset too, but when it comes to online teaching, I do not get to see their faces. So, I’m assuming that I am the best teacher alive (Tasneem, personal communication, June 5, 2022).

The shocking point for me is that we have not returned to normal. Even the teaching method that you were thinking is a good thing in class, that if you use it, you will be a good teacher was not like before, never, ever (Alanoud, personal communication, June 14, 2022).

I tried to control the situation, and then after that, they did not even bother to talk to each other... It made me feel like I lost my teaching skills and my interaction skills (Aya, personal communication, June 5, 2022).

Besides, teachers went to critically reassess their invisible values and meanings that underline being and working as a language teacher in relation to the current context:

It really hits a big concept in my life, which is passion and meaning. I’m trying to do something meaningful, but it does not seem as meaningful as I thought it would be. Also, is this what I want to do in my life? Am I passionate enough to make other people like what I’m doing? (Tasneem, personal communication, June 5, 2022).

It looked like I was not interesting enough or motivating them enough... Maybe my level of motivation should be more than what I provided them with (Aya, personal communication, June 5, 2022).

Indeed, evaluative language in teachers’ stories such as “assuming that I am the best teacher alive,” “not like before,” “lost my teaching skills,” “not interesting enough or motivating them enough,” and “passionate enough” evoke teachers as doing an active assessment of how they see themselves fitting into the changed teaching context. This skeptical act enriched teachers’ developmental opportunities as they acknowledged that the changes in the teaching context demand a significant change in their identity to sufficiently align with the new teaching context. They knew that they could not “control the situation,” yet they did not flow passively in the stream of change (Vähäsantanen and Eteläpelto, 2011; Vähäsantanen, 2015). Instead, they actively assessed the changes and chose to accept these changes in their identity as the initial step to endorse the transformation. Consequently, teachers practiced their identity-agency by delegitimizing their old identity. Identity delegitimization includes teachers’ awareness that their original professional identity was in clear conflict with the current context and that they should accept the contextual changes in their teacher-selves to develop professionally.

Identity transformation at this stage is viewed as a process in which teachers delegitimize their “old” identity as a conscious step to work out the mismatch between their previous views and the current roles and responsibilities of the changed teaching context and develop their professional identity. This view opposes the previously initiated relationship between teachers’ passivity and weak agency in the context of educational reform where teachers have less to no control over the change (Lasky, 2005; Pyhältö et al., 2012). In contrast, it illuminates teachers’ acceptance of the changes in their professional identity as a practice of agency in which teachers are actively engaged with the change to develop their identity. At this stage, teachers felt the need to dismiss their original ideas about what makes an effective language teacher and reported significant changes in the ways they view themselves as professionals.

Reconstructing identity: agentive development

By accepting the transformation in their old identity, the seven teachers employed the disorienting experience as a venue wherein they drew on collective experiences to challenge their prior ones and enhance their understanding of the new interpretations. Thus, their view of their teacher-selves became “more inclusive, discriminating, open, reflective and emotionally able to change,” generating new understandings that are more “justified to guide action” (Mezirow, 2006, p. 92). Through comparing the contexts, teachers were able to “monitor the epistemic nature of problems and the truth value of alternative solutions” (King and Kitchener, 1994, p.12). As they recognized the serious effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on their personal and professional selves as well as on the educational setting, they started to critically reflect on their changing teaching roles and responsibilities and deliberately negotiate who they are, what they need to achieve, what pedagogical decisions they make, and why in light of the disorienting experience. This process coexisted with multiple trials that put the new meaning perspectives into practice, which is crucial to enhance effective transformation (Baumgartner, 2001), and identity development.

The high-point stories depict teachers’ agency as a site where teacher identity is reconstructed and reshaped. Despite the differences in their new interpretations about what makes “good” teaching in the new context, the seven teachers adapted new teaching approaches and pedagogies that allow them to be the kind of teachers they want to be. These agentive acts constituted a critical resource for them to enact identity transformation and live out their evolving perception of themselves as professionals. According to Fleming (2016), Mezirow always argued that learning or transformation does not occur until one acts on the basis of a new set of assumptions.

Since the pandemic created difficult times for students and teachers alike, teachers sought to find a resolution, thus changing their teaching approaches, and assuming different roles. In this regard, Tasneem stated “I try to make my classes as entertaining as possible because students learn so much through playing, through fun discussions, … I do believe that life is hard in many ways” (Tasneem, personal communication, June 5, 2022). Apparently, her decision to implement fun materials in the classroom was a thoughtful response to ease the tensions and the “hard” life imposed by the pandemic. Her identity-agency was conceptualized as a renegotiation and reshaping of her post-pandemic professional identity to assume roles that align with her changed perspectives, asserting that “I’m not really someone who just delivers the information, and I pack my stuff and leave. I had a role…making their [students] life more delightful in a way” (Tasneem, personal communication, June 5, 2022). A similar account was found in Aya’s story where the development in her identity included agentive development in terms of employing new pedagogies that best fit her reframed and contextualized understanding of teaching. For her, implementing creative interactive online activities in the f2f context where students were less interactive and more attached to their phones was crucial to the reconstruction of her identity as “a good teacher” as she “did something good” and adapted to the change by choosing “the right activity in the right time for the right section” (Aya, personal communication, June 5, 2022). In these accounts, developing teacher identity was mingled with enacting agentive practices and utilizing new pedagogies that align the teachers’ reframed understanding of teaching. Making these decisions was significant for their development as professionals.

In addition, teachers sought to reshape their roles and responsibilities in the classroom in light of the disorienting experience. A fundamental change did not occur until they began to develop a deeper understanding of the meaningful connection of place to their professional identity, pedagogies, and practices. This would explain teachers’ description of the return to the physical classroom as the “highest and the best moment” (Dalal) and the “most enjoyable moment” (Maysem) where their identity development is “negotiated, lived, and practiced” (Gross and Hochberg, 2016, p.1244) in re-establishing meaningful connections with the physical classroom. For them, teaching online led to a huge detachment from their “original” teacher-selves since they felt uncertain about students’ presence and learning progress and could not effectively interact with students. This detachment, however, has triggered “a rational, metacognitive process of reassessing reasons that support [such] problematic meaning perspectives” (Mezirow, 2006, p. 103). In this process, teachers started to reassess the quality of f2f teaching compared to online teaching, in terms of maintaining eye contact with students, establishing a connection with the students, and observing students’ learning progress in maintaining effective learning, and thus making decisions about what they should do in the new context.

In high point stories, six teachers also reconstructed their professional identity by taking up new responsibilities as a part of acting upon their transformed insights and promoting their efficacy as a language teacher. In such contexts, the teachers emphasized establishing rapport with students or what they called an “emotional bond” (Maysem) or “deep emotional connection” (Alanoud) as an integral part of their new teaching responsibility in the f2f class. While students were reported as less interactive, anti-socialized, and disengaged, the teachers mentioned how they incorporated multiple practices and engaging activities so that they could build strong connections with students who could freely approach them and interact with them, the fact that was not possible in the online platform unless “you are in front of them in flesh and blood” (Sonia). This assumed responsibility was significantly tied to their efficacy as a teacher. For instance, Sonia denoted,

I believe it’s all again, about how well you are able to build a rapport with your students... A student has to be very comfortable with her teacher. She should not hesitate in asking her a question... Even the more inhibited ones should not feel shy about asking you. And if they are, then it’s up to you to elicit, to ensure, or ask them to get them to ask you (Sonia, personal communication, June 23, 2022).

Whereas Dalal associated her success in the teaching profession with building teacher-student connections in the physical classroom. For her, this connection was an ultimate goal delineating that, “I succeeded to connect with my student... I can have the highest degree in teaching, in my profession... when my students do not come or they do not ask me, I feel there is something wrong with me” (Dalal, personal communication, June 15, 2022). From a different standpoint, Sara reflected,

I felt like I finally knew my student, my student’s level of writing, and my student’s proficiency level. I felt like I’m connecting with my student again. Instead of correcting none of their work, I got exhausted because it is really apparent that [it] was not a student’s writing or mistakes. The words do not make sense. Finally, like I’m teaching, I’m really teaching. Um, students are learning, which is the big goal or the main goal, basically. That’s why I felt it’s a, yeah, yeah (with a relieved tone) this is what I can say (Sara, personal communication, June 20, 2022).

In the above extract, Sara described the observation of students’ actual writing production as a true connection with her students. This act was obviously not possible in the online context, which explains the state of relief that was mingled with her reconstructed teacher role and identity. It was through comparing and contrasting contexts that Sara felt her identity as a language teacher was reclaimed in light of reframing her teaching objectives in the classroom.

Teachers’ conceptualization of the adjustments in their approaches as high points not only suggests their value for easing the tensions resulting from the disorienting experience but also outlines taking these agentive acts as a key step in their development as teachers. In these narratives where the seven EFL teachers reported a significant transformation in their teaching perspectives, they reconstructed their professional identity by carrying out the new professional roles and responsibilities laid down by the transformed insights, which are flexible and negotiable in nature. Ideally, the participating teachers enacted their identity-agency by reconstructing their professional identity as fluid, contextual, and open to change to align with the TL experience. In this identity development process, the identity-agency served as a “mediator” (Ruohotie-Lyhty, 2018) to link teachers’ new meaning perspectives and new assumed roles, illuminating purposeful agency and identity development. This type of agentive development is partially consistent with what Ruohotie-Lyhty (2018, p. 7) describes as “additive development” in that teachers adapted new pedagogical convictions as a part of identity development “to better match the environmental conditions and to develop professionally.” While Ruohotie-Lyhty (2018) highlights the match between teacher-self and environment to allow development to take place, agentive development reported in the current study is closely intertwined with a significant transformation in teachers’ teaching perspectives and their conceptualization of their teacher-selves, as a key step to act upon the disorienting experience and respond to the discrepancy between teacher old identity and the changed educational setting. The transformation in teachers’ perspectives and interpretations is here viewed as a responsive act to teachers’ dismissal of their original perspectives about being teachers so that they became open to change.

Empowering identity: awareness of development

In the turning point stories where teachers negotiated significant shifts in their professional identity and practices, they demonstrated a greater awareness of the positive transformations in their teacher-selves. This awareness was mingled with the recognition of the potential personal and professional growth created by the pandemic, which in turn, has expanded their professional experiences and confidence in their new roles. Altogether, these factors have empowered teachers’ identity as positive learners who could reintegrate the lessons learned into their current and future teaching careers.

This process of identity empowerment was further promoted by teachers’ critical reflection and assessment of their collective experiences. While reported dialogs with other colleagues led some teachers to make sense of their new experiences, the reflective spaces offered in this narrative inquiry allowed teachers to reconstruct their life stories as a means for self-exploration, agency negotiation, and redemption from challenging experiences (Bauer et al., 2005). In effect, the participating teachers considered the interview as a “therapy” (Tasneem) and a “click” and “learning moment” (Maysem) as it promotes shuttling between what teachers experienced and what they learned from the disorienting experience. Very soon amid reflection, teachers started to realize that the drastic shifts in their roles as well as the educational setting should not necessarily be disruptive in a negative sense. Instead, they considered all the shifts and dispositions in the disorienting experience as a catalyst for self-discovery and identity development. They reflected:

I became more open to the change. Like I do not see it as negative as I used to see it... I try to enjoy it (Maysam, personal communication, June 15, 2022).

I think my low point has led to my high point in this situation. I feel like they are so connected. What I thought was, at the end of my teaching career was actually the core of me continuing, in continuing teaching actually. So yeah, I would say bliss in disguise (Tasneem, personal communication, June 5, 2022).

Although it was sudden with all the cons it had, it made a huge refresh. It made you observe yourself as a face-to-face teacher and what you could do, to get the student back on track (Sara, personal communication, June 20, 2022).

These reflective accounts illustrate instances of heightened self-awareness and professionalism where teachers were willing to take advantage of the disruption in the status quo and move forward. They encompass meaningful moments where teachers positioned themselves as flexible and sustained teachers who could “change,” adapt, as well as “carry and maintain working in the education industry while maintaining mental sanity and meaning” in times of change (Tasneem). This expansion of their consciousness about their teacher-sense of self and their capacities in relation to the disorienting experience has evidently increased teachers’ confidence, resulting in the development of their inner-self and professional identity.

Central to their deepened self-awareness was teachers’ reflection and recognition of their ability to deal with challenges in times of change. Thus, many teachers characterized the development of their professional competence as a crucial part of their identity development in stories that describe significant shifts in their experiences. Teachers’ creativity and gained knowledge such as in reading about and utilizing innovative teaching strategies for the first time amid disorientation as well as transferring the acquired online teaching skills to the physical classroom appeared as driving forces that allowed teachers to not only “create something that suits the circumstances” (Dalal) but also recognize their professional growth. As Sara reflected,

I felt it [COVID] taught me a lot of things. I felt it added one year of experience besides having all my experiences as an online teacher because this single thing needs a lot of different skills, so you have all the expertise as an online teacher, and then returning as a face-to-face teacher, I’m still doing some of the stuff I used to do online,... So I felt the return from online has taught me a lot, improved me a lot. Besides all the activities I was doing with my students before COVID, I added some more because I left it for a while and returned so I looked up new things, new strategies, new techniques, and new activities. So, returning was for us like a refresh (Sara, personal communication, June 20, 2022).

Besides expanding resources, online teaching skills, and technology use, teachers could ultimately view teaching as a situated, social, and human act in nature. They became aware that circumstances change and that instead of resisting the changes, they accentuated the need to be prepared to deal with crises and unexpected challenges in general. Thus, the participating teachers conceptualized the development of their professional identity as they negotiated what teachers should do in the future to maintain quality teaching in times of crisis:

I think it has been a time that tests us, and I think this pandemic has also taught us that, regardless of what the situation is, work must go on, business must go on. It should never stop. So, one has to look for options, and one has to accept them with grace and dignity and take it up as a challenge and try to make it the best possible class, whether it is online or it is face to face... So besides just learning nouns, pronouns, and academic writing, you are also learning how to deal with situations which can help you evolve as a wonderful human being and a wonderful student after that (Sonia, personal communication, June 23, 2022).

I need more awareness of what might be expected in that environment, not just having to know what I am doing and what I am teaching, I memorize the book, I know the pages, and so on. But it is not just that. That is not just the thing that happens in the classroom, in the teaching process. So, yeah maybe for me it is [the learned lesson] to be more aware of all the other things and aspects that are going to happen in the classroom, to be prepared much better. (Maysam, personal communication, June 15, 2022).

In these stories, teachers’ expanded awareness and competence were not limited to their instrumental learning but also extended to TL where teachers could understand changes in their teacher-selves, make sense of the changes, and thus reintegrate their new meanings into their teaching career in the post-pandemic era, as a principal outcome of their TL experience (Mezirow, 2006). Indeed, the use of imperatives here as in “has to look for options” and “to be prepared” postulates the reintegration of their new perspectives into their profession dictated by the disorienting experience. In such contexts, reflection became a conscious tool for negotiating professional growth and development, where the development of self-awareness and competence served as a professionally crucial means for identity empowerment. Identity development at this stage is defined as a process in which teachers develop greater self-awareness and build competence and confidence in their new roles in light of their gained new experiences, thus empowering their identity. Teachers’ identity-agency in these cases is enacted by reconstructing their identity as positive learners who could capitalize on the learned lesson and consciously develop as professionals.

Concluding remarks

This narrative inquiry is a step forward in examining how the changed educational setting post the COVID-19 pandemic impacted and intersected with teachers’ professional identity development in the Saudi context. Through LSI (McAdams, 2008), seven EFL teachers reflected on their teaching experiences post-pandemic and emphasized low points, high points, and turning points in their teacher-selves. This section discusses three emerging aspects from the findings that add to the scholarly literature on EFL teacher identity development, TL, and professional agency and inform teacher education programs in Saudi Arabia.

First, teachers’ stories confirm the view of educational change as a disorienting experience (Mezirow, 2000) that serves as a catalyst for teachers to unpack and transform their understanding of their professional selves (Farrell, 2021; Young et al., 2022). Despite the tension, stress, and uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, a variety of opportunities including transformation, confidence, and increased self-awareness have emerged. The task now is for teacher education programs to implement and leverage the highly effective practices that have emerged as an outcome of the pandemic to support teachers’ transformation process and identity development.

Critical self-reflection appears to be a driving force that enhances teachers’ self-understanding and professional identity development. Through critical reflection, teachers were able to challenge prior assumptions about their roles and responsibilities as language teachers. This has created a great sense of flexibility where teachers’ experiences became more “inclusive, differentiating, permeable, critically reflective, and integrative of experience” (Mezirow, 1996, p.163) regarding who they are and what they are expected to do. In this sense, critical reflection has enhanced teachers’ TL by challenging their prior assumptions, developing new meanings, and acting upon their emerging meanings leading to behavioral change. It also facilitates teachers’ “learning within awareness” (Mezirow, 2006, p. 101) allowing them to recognize all the positive transformations in their personal and professional growth and act upon this newfound awareness that is critical for their identity development (Illeris, 2014; Meijer et al., 2017). These findings resonate with Greene and Park (2021) and Song (2022) argument that reflection represents a critical lens to magnify and unfold teachers’ disruptive sense of self caused by the pandemic, which in turn allowed them to cope with and understand their positioning in the disrupted teaching context. The current study further expands on the conceptualization of the magnifying lens by demonstrating the reciprocal relationship between critical reflection, expanded self-awareness, and behavioral change in the development and transformation of seven in-service EFL teachers’ professional identities.

These findings have significant implications for the development of current language teacher education programs in Saudi Arabia. Policymakers should consider integrating critical reflection practices to enhance the development of EFL teachers’ professional identities. Given that most TL occurs outside the awareness (Mezirow, 2006), educators should help teachers become aware of this process and boost their ability to engage in TL. Reflective journals, critical incidents, and life stories may serve as useful tools for teachers to expand their consciousness, understand the temporal dimensions and changes in teacher identities through time, and thus “generate beliefs and opinions that will prove more true or justified to guide action” (Mezirow, 2006, p. 92).

Second, the current research, which is rooted in Mezirow’s TL theory, contributes to the advancement of EFL teacher identity development research in Saudi Arabia. While research on EFL teachers’ identities is in its early phases, this research introduces a conceptual framework for navigating and describing language teachers’ identity negotiation and transformation, especially in times of change. The nuanced process of identity negotiations unfolded in the participants’ reflections highlights the soundness of this theoretical framework in revealing the rational and metacognitive process of teacher identity development. Adapting Mezirow’s theory has lent theoretical support for navigating rational transformations in awareness and behaviors that are both critical for maintaining professional growth at the personality identity layer (Illeris, 2014; Meijer et al., 2017). Although teachers’ stories revealed a recurring pattern in their TL and identity development, this process was not linear and instead appeared to be more fluid, recursive, and individualized (Baumgartner, 2001), capturing the dynamic and multilayered process of identity negotiation and transformation.

In addition, adopting professional agency as an analytical lens enriches the literature that conceptualizes teachers’ identity development as a significant outcome of TL (Kelchtermans, 2009; Illeris, 2014). While Mezirow’s conceptualization of TL as a change in meaning perspectives has been criticized for being narrowly framed, incorporating the lens of professional agency has elucidated the extent of teachers’ TL by illuminating “changes in elements of the learner’s identity” (Illeris, 2014, p. 580). This conceptual platform enhanced the understanding of how TL took place by disclosing the fundamental changes in teachers’ awareness and behaviors connected with evaluating and reconstructing their complex narrative selves. Such changes include teachers’ expanded consciousness for handling unexpected challenges, navigating innovations, and making justified decisions that characterize the evolving nature of contemporary society, which in turn, resources teachers’ agentive identity development. Consequently, this study postulates a comprehensive framework that combines Mezirow’s theory with a focus on professional agency for future research on language teacher TL and identity development.

The last conclusion that deserves special attention is the crucial role of teacher identity-agency as a tool where teacher identity is negotiated or transformed. Based on the results of this study, the teacher identity development process is viewed as an agentive act that includes identity delegitimization, reconstruction, and empowerment as a part of reconstructing teachers’ narrative selves and bridging the gap between self and the changed educational setting. These findings broadly align with Ruohotie-Lyhty (2018) study, emphasizing the role of identity-agency in mediating the match between self and environment, thus accentuating the development of teachers’ identity. This match, however, does not imply assimilation into the changed environment. Rather, it delineates teachers’ purposeful agency to create a balance between their new understandings and what they are expected to do in light of the disorienting experience, leading to “tentative best judgment” (Mezirow, 2000, p. 11). Thus, the current study conceptualizes teachers’ identity-agency as a consciously directed performance of critical self-reflection, which is a driving force for teacher identity transformation. As teachers attempted to reassess the problematic issue (Mezirow, 2006), they were subconsciously engaged in the process of critical reflection in unpacking and challenging their prior teacher selves. Yet, practicing identity-agency would enable teachers to consciously challenge their unquestioned assumptions, make new meanings, and verify these emerging understandings, which are critical to their transformation.

Teacher education programs often fall short of adequately supporting student teachers in developing their professional identities (Beauchamp and Thomas, 2009). This study highlights professional agency as a critical component of understanding EFL teachers’ identity development and enacting transformations. Given the study’s findings and shortcomings in teacher education programs, it is imperative for policymakers and teacher educators to establish policies and practices that assist teachers in achieving positive changes by enhancing professional agency. Such initiatives should include establishing trusting communities where teachers can collaboratively make sense of their experiences, address their fears, and learn from each other. Ultimately, this would create a supportive learning environment that helps teachers feel safe, confident, and receptive to any necessary transformation and development. Furthermore, educators can promote teachers’ professional identity development by training teachers and other stakeholders to analyze the potential impact of the reform on students, teaching roles, and pedagogical practices and prepare them to teach in adverse conditions. This, in turn, would empower them as active agents and legitimize their new expected roles and responsibilities, thus enhancing the efficacy of the reform.

While assessing this study’s contribution, it is crucial to keep in mind its limitations. One limitation of this study is the convenience sampling that was used because of the COVID-19 pandemic’s circumstances and social distancing precautions. Thus, the results of this study are based on a small sample of seven female EFL teachers in a Saudi university. Despite thoroughly and contextually examining a phenomenon, the convenience purposive sampling strategy, which is a nonprobability method, limits the breadth of the findings. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to a general population. Given the nature of this qualitative inquiry, the participants’ narratives provided rich data that answered the research questions. Nevertheless, a larger sample size might bring different results. Furthermore, while this study aimed to explore how EFL teachers negotiate and maintain their professional identity post the pandemic, it primarily recorded their initial reflections on how disrupted teaching contexts affected teacher identity as they were adapting to the new normal. There is arguably room for different interpretations of their experiences and professional identity development as teachers become more adapted to and involved in the transformed teaching context. As such, longitudinal future research is recommended to generate knowledge about the transformative and complex process of professional identity construction, especially in the time of reform.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by ELI Ethics Committee, KAU, Saudi Arabia. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1275297/full#supplementary-material

References

Ahearn, L. M. (2001). Language and agency. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 30, 109–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.109

Akkerman, S. F., and Meijer, P. C. (2011). A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 308–319. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.013

Ashton, K. (2022). Language teacher agency in emergency online teaching. System 105:102713. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102713

Asselin, M. E. (2003). Insider research: issues to consider when doing qualitative research in your own setting. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 19, 99–103. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200303000-00008

Barkhuizen, G. (2016). A short story approach to analyzing teacher (imagined) identities over time. TESOL Q. 50, 655–683. doi: 10.1002/tesq.311

Barkhuizen, G. (2021). Language teacher identity. Res. Questions Lang. Educ. Applied Linguist. Reference Guide, 549–553. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-79143-8_96

Bauer, J. J., McAdams, D. P., and Sakaeda, A. R. (2005). Interpreting the good life: growth memories in the lives of mature, happy people. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 88, 203–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00346.x

Baumgartner, L. M. (2001). An update on transformational learning. New Directions for Adult Continuing Educ. 2001, 15–24. doi: 10.1002/ace.4

Beauchamp, C., and Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: an overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Camb. J. Educ. 39, 175–189. doi: 10.1080/03057640902902252

Beijaard, D., Meijer, P., and Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 20, 107–128. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 9, 3–26. doi: 10.1037/qup0000196

Buchanan, R. (2015). Teacher identity and agency in an era of accountability. Teachers Teach. 21, 700–719. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044329

Bukor, E. (2015). Exploring teacher identity from a holistic perspective: reconstructing and reconnecting personal and professional selves. Teachers Teach. 21, 305–327. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2014.953818

Chaaban, Y., Al-Thani, H., and Du, X. (2021). A narrative inquiry of teacher educators’ professional agency, identity renegotiations, and emotional responses amid educational disruption. Teach. Teach. Educ. 108:103522. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103522

Clarke, M. (2008). Language teacher identities: Co-constructing discourse and community. Multilingual Matters. doi: 10.21832/9781847690838

Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2014). “Thematic analysis” in Encyclopedia of critical psychology. Ed. T. Teo (New York, NY: Springer), 1947–1952.

Connelly, F. M., and Clandinin, D. J. (2006). “Narrative inquiry” in Handbook of complementary methods in education research. eds. J. L. Green, G. Camilli, and P. Elmore (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 477–487.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. US: Sage Publications.

Cutri, R. M., Mena, J., and Whiting, E. F. (2020). Faculty readiness for online crisis teaching: transitioning to online teaching during the COVID 19 pandemic. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 523–541. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1815702

De Costa, P. I., and Norton, B. (2017). Introduction: identity, transdisciplinarity, and the good language teacher. Mod. Lang. J. 101, 3–14. doi: 10.1111/modl.12368

El-Soussi, A. (2022). The shift from face-to-face to online teaching due to COVID-19: its impact on higher education faculty's professional identity. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 3:100139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2022.100139

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., and Hökkä, P. (2015). How do novice teachers in Finland perceive their professional agency? Teachers Teach. 21, 660–680. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044327

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., and Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educ. Res. Rev. 10, 45–65. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001

Farrell, R. (2021). Covid-19 as a catalyst for sustainable change: the rise of democratic pedagogical partnership in initial teacher education in Ireland. Irish Educ. Stud. 40, 161–167. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2021.1910976

Farrell, R., and Sugrue, C. (2021). Sustainable teaching in an uncertain world: Pedagogical continuities, un-precedented challenges. In Teacher education in the 21st century –Emerging skills for a changing world. Ed. M. J. Hernández-Serrano (IntechOpen), pp. 101–118.

Fleming, T. (2016). Toward a living theory of transformative learning: going beyond Mezirow and Habermas to Honneth. This is the text of the 1st Mezirow memorial lecture at Columbia University Teachers College sponsored by AEGIS IXX, The Department of Organization and Leadership and the Office of Alumni Relations at teachers College, New York.

Giampapa, F. (2011). The politics of “being and becoming” a researcher: identity, power, and negotiating the field. J. Lang. Identity & Educ. 10, 132–144. doi: 10.1080/15348458.2011.585304

Greene, M. V., and Park, G. (2021). Promoting reflexivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. American J. Qualitative Res. 5, 23–29. doi: 10.29333/ajqr/9717

Gross, M., and Hochberg, N. (2016). Characteristics of place identity as part of professional identity development among pre-service teachers. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 11, 1243–1268. doi: 10.1007/s11422-014-9646-4

Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action: Jurgen Habermas ; trans. McCarthy Thomas. US: Heinemann.

Haniford, L. C. (2010). Tracing one teacher candidate's discursive identity work. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.041

Harford, J. (2021). All changed: changed utterly’: Covid19 and education. Int. J. Historiography of Educ. 11, 55–81.

Harris, A., and Jones, M. (2020). COVID 19–school leadership in disruptive times. School Leader. Manag. 40, 243–247. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2020.1811479

Hollweck, T., and Doucet, A. (2020). Pracademics in theft pandemic: pedagogies and professionalism. J.Professional Capital and Community 5, 295–305. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-06-2020-0038

Hong, J. Y. (2010). Pre-service and beginning teachers’ professional identity and its relation to dropping out of the profession. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 1530–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.003

Illeris, K. (2014). Transformative learning and identity. J. Transform. Educ. 12, 148–163. doi: 10.1177/1541344614548423

Johnston, B., Pawan, F., and Mahan-Taylor, R. (2013). “The professional development of working ESL/EFL teachers: a pilot study” in Second language teacher education Ed. D. Tedick (UK: Routledge), 53–72.

Jones, A. L., and Kessler, M. A. (2020). Teachers’ emotion and identity work during a pandemic. Front. Educ. 5:195. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.583775

Kanno, Y., and Stuart, C. (2011). Learning to become a second language teacher: identities-in-practice. Mod. Lang. J. 95, 236–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01178.x

Kelchtermans, G. (2009). Who I am in how I teach is the message: self-understanding, vulnerability and reflection. Teachers Teach. 15, 257–272. doi: 10.1080/13540600902875332

Ketelaar, E., Beijaard, D., Boshuizen, H. P., and Den Brok, P. J. (2012). Teachers’ positioning towards an educational innovation in the light of ownership, sense-making and agency. Teach. Teach. Educ. 28, 273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.10.004

Kim, L. E., and Asbury, K. (2020). ‘Like a rug had been pulled from under you’: the impact of COVID-19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the UK lockdown. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 90, 1062–1083. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12381

Kim, L. E., Oxley, L., and Asbury, K. (2022). What makes a great teacher during a pandemic? J. Educ. Teach. 48, 129–131. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2021.1988826

King, P. M., and Kitchener, K. S. (1994). Developing reflective judgment: understanding and promoting intellectual growth and critical thinking in adolescents and adults. Jossey-bass higher and adult education series and Jossey-bass social and behavioral science series. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA.

Lasky, S. (2005). A sociocultural approach to understanding teacher identity, agency and professional vulnerability in a context of secondary school reform. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 899–916. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.003

Lipponen, L., and Kumpulainen, K. (2011). Acting as accountable authors: creating interactional spaces for agency work in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 812–819. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.001

Liu, S., Yuan, R., and Wang, C. (2021). Let emotion ring’: an autoethnographic self-study of an EFL instructor in Wuhan during COVID-19. Lang. Teach. Res. 136216882110534. doi: 10.1177/13621688211053498

McAdams, D. P. (2008). The LSI. The Foley Center for the Study of lives. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University.

Meijer, M. J., Kuijpers, M., Boei, F., Vrieling, E., and Geijsel, F. (2017). Professional development of teacher-educators towards transformative learning. Prof. Dev. Educ. 43, 819–840. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2016.1254107