- School of Arts and Creative Technologies, University of York, York, United Kingdom

This research explores perceptions of dialogic teaching amongst trainee instrumental/vocal teachers enrolled on the MA Music Education: Instrumental and Vocal Teaching programme at the University of York. Thirty students from three different cohorts responded to an online questionnaire. Findings indicate that respondents were aware of a broader range of advantages of using dialogic teaching than disadvantages. Despite this, 59% of respondents reported that they inconsistently use dialogic teaching. Respondents also reported that they learn to use dialogic teaching through observation of fellow teachers, practical teaching experience, and peer-to-peer discussion. Some respondents viewed dialogic teaching primarily as a process of teacher-led questioning, rather than questioning and discussion, which suggests that trainee teachers may benefit from a more in-depth understanding of dialogic teaching within the context of instrumental/vocal lessons. The results of this research are of relevance to teachers, teacher educators, and providers of pedagogical resources.

1 Introduction

1.1 Dialogic teaching in instrumental/vocal lessons

The social nature of speech and its dialogic potential is highlighted by Bakhtin’s theory of ‘voice’ (Cazden, 1996). The ‘voice’ considers the social context in which it is situated by acknowledging that the person speaking (or writing) is doing so in a specific place and time and that the voice’s utterances represent values or opinions. The ‘voice’ also considers the other voices it addresses (Cazden, 1996). Bakhtin suggests that meaning is constructed through the interaction and development of ideas as a result of this dialogic exchange (Daniel, 2016). Furthermore, Delp (2004) argues that ‘multivoiced discourses’ (p. 203), where ideas are exchanged and then internalised, lead to an ‘ideological becoming’ that enables participants to develop new meaning and understanding. Similarly, within educational contexts dialogue between teachers and students has been described as integral to meaning-making and learning (Matusov, 2009; Wegerif, 2011). Matusov (2009) suggests that dialogue is omnipresent within education because it is closely connected with meaning; learning is a shared discovery for both the student and teacher that is facilitated through dialogue. Wegerif (2011) argues that dialogue is not only an effective teaching strategy, but ‘a way of being in the world’ (p. 8). Theoretical literature indicates that dialogue can be facilitated when teachers are committed to learning with their students and when both teachers and students are able to ask questions that confront one another’s interpretations (Freire and Shore, 1987; Matusov, 2009).

Many pedagogical approaches have been developed to promote classroom dialogue, including dialogic instruction (Nystrand, 1997), dialogic inquiry (Wells, 1999), dialogical pedagogy (Skidmore, 2000), and dialogic teaching (Alexander, 2020). Skidmore (2016) suggests that pedagogical approaches designed to encourage dialogue enhance student progress and enable students to explore alternative perspectives. Dialogic teaching (Alexander, 2020) has been found to be effective within instrumental/vocal lessons (Meissner, 2017; Meissner and Timmers, 2019; Meissner et al., 2021) and has been defined as an extended teacher-student exchange consisting of four primary components: questioning, discussion, extending, and argumentation. Alexander (2020) provides eight dialogic teaching ‘repertoires’ (p. 126) that support teachers in facilitating dialogue within classroom settings. Meissner (2017) found that five out of the 14 participating instrumental students (aged 9–15) were able to improve their musical expression in two pieces, with four of these five students having been taught by teachers using enquiry and discussion and ‘instruction about modifying expressive devices’ (Meissner, 2017, p.118). Furthermore, Meissner and Timmers (2019) conducted a teaching test in which a control group of students (aged 8–15) were instructed by the researchers to focus on their technical accuracy in performing two set pieces. An experimental group of students also addressed the technical challenges of the pieces but the researchers asked questions about expressive techniques and discussed the mood of the piece using the dialogic teaching framework. Performances were then assessed by independent adjudicators, with results indicating that the experimental teaching was more effective in enabling students to improve their musical expression during a performance of a ‘sad’ extract than the control teaching, while the control teaching was effective in developing students’ technical accuracy (Meissner and Timmers, 2019, p. 33). In semi-structured video-stimulated recall interviews, Meissner et al. (2021) found that students in the experimental group valued the opportunity to discuss the musical character with their teacher and were able to independently consider and develop their musical expression. In a separate study Meissner and Timmers (2020) found that peripatetic instrumental teachers viewed dialogic teaching as effective in developing musical expression, at-home practice, rhythm, and pitch in lessons with students aged between 8 and 15.

1.2 Teacher perceptions of dialogic teaching

Despite potential benefits, research suggests that some teachers are reluctant to use dialogue. Hughes (2005) found that trainee classroom music teachers rarely asked questions and instead launched into ‘mini lectures’ (p. 84) at the beginning of school music lessons. Through analysis of video recordings, Hughes (2005) found that, whilst many teachers believed they were asking questions, they went on to provide the answers and failed to facilitate dialogue. West and Rostvall (2003) studied video recordings of lessons given by four teachers working in Swedish schools and found that teacher-student interactions were heavily dominated by teachers, with 4,851 teacher utterances being instructional. Only 691 utterances contained questions, and West and Rostvall (2003) claim that most of these were answered by the teachers. Similarly, in their review of literature concerning verbal interactions between instrumental/vocal teachers and their students in ensemble settings, Warnet (2020) found teachers infrequently used questioning and discussion. Warnet (2020) notes that ‘novice’ (p. 14) teachers’ questioning often lacked focus and indicates that further research is needed to understand how teachers can use questioning to enhance student progress. Burwell (2012) found that exam deadlines resulted in one teacher within a university music department adopting a ‘directive’ (p. 124) approach that dominated verbal exchanges between the teacher and student. In addition, Burwell (2019) reported that two undergraduate students’ instrumental lessons mainly consisted of teacher feedback and the teachers’ transmission of knowledge.

Furthermore, at the beginning of Meissner’s (2017) action research project none of the teacher participants suggested dialogue as a possible teaching strategy; teachers were later ‘surprised’ (p.127) by the positive effect on students’ expressive performance. Similarly, Meissner and Timmers (2020) found that their teacher participants had not previously incorporated dialogic teaching, but by the end of the project four (out of five) teachers considered dialogic teaching to be effective. Whilst teacher perceptions of dialogic teaching changed over the course of these projects (Meissner, 2017; Meissner and Timmers, 2020), a limited amount of detail concerning how teachers develop dialogic teaching skills is provided. Meissner (2017) states that teacher participants discussed ‘various methods for teaching expressivity’ (p. 122) in an initial meeting and were able to share ideas during breaks. Teachers in Meissner and Timmers’ (2020) project took part in a workshop that outlined research concerning musical expression and watched video recordings of each other’s lessons, meeting on three occasions to discuss experiences (Meissner and Timmers, 2020). The researchers give little further detail concerning these activities (Meissner, 2017; Meissner and Timmers, 2020) and do not indicate how many participants valued these experiences or to what extent teachers believed they supported the development of dialogic teaching skills (Meissner, 2017; Meissner and Timmers, 2020). Given that dialogue has been described as integral to learning (Matusov, 2009; Wegerif, 2011) and that instrumental/vocal teachers have been found to inconsistently facilitate it, insight into how teachers can start to use dialogue would be relevant to educators of instrumental/vocal teachers. Moreover, studies outlined within this literature review exclusively concern the experiences of teachers in existing roles; insight into the perceptions and experiences of trainee teachers would be of interest to teacher educators who may wish to support these individuals in developing dialogic teaching skills.

1.3 How do trainee teachers learn to teach effectively?

Existing research has explored how trainee teachers learn to teach (Haddon, 2009; Cain, 2011; Legette and Royo, 2021) but these studies have investigated how teachers acquire a broad range of teaching skills, rather than the ability to use dialogue. For example, Cain (2011) found that peer discussion groups enabled trainee classroom music teachers to collectively discuss solutions to common problems. The topic of each session was decided through a democratic vote (Cain, 2011), with all but one of the trainee teachers reporting that the discussions were useful. Some participants felt reassured that peers were facing similar problems (Cain, 2011), a finding that is echoed in Ballantyne’s (2006) study which found that trainee classroom music teachers benefitted from sharing personal experiences.

Teaching experience also seems to support the development of trainee teachers, as undergraduate music students in Haddon’s (2009) study viewed experience as one of the most helpful ways to develop as an instrumental/vocal teacher, whilst 65% of professors at the Royal College of Music indicated that acquiring experience had been most beneficial to their development as instrumental/vocal teachers (Mills, 2004). Similarly, 21.8% of instrumental/vocal teachers who responded to a survey as part of research by Norton et al. (2019) considered teaching experience, skills, and personal attributes as necessary requirements to teach, with one respondent claiming that ‘one learns from one’s pupils’ (p. 570).

Observation of fellow teachers is given as a strategy for developing teaching skills by the conservatoire professors in Mills’ (2004) study. Furthermore, trainee choral teachers in Legette and Royo’s (2021) research reported that they valued the opportunity to watch their peers teach and receive constructive criticism, a finding that is echoed by the trainee vocal teachers in Conkling’s (2003) study. Ultimately, though, these studies do not explore how trainee instrumental/vocal teachers might begin to use dialogue or dialogic teaching.

1.4 Research questions

In summary, research concerning dialogue has prioritised the experiences of instrumental/vocal teachers in existing roles, rather than those completing pedagogical qualifications (West and Rostvall, 2003; Burwell, 2012; Meissner, 2017). As a result, little is known about how trainee teachers perceive dialogic teaching or in which circumstances they would use dialogue. Research has indicated that most teachers come to believe that dialogic teaching is effective but it has not explored how teachers developed dialogic teaching skills (Meissner, 2017; Meissner and Timmers, 2020). Finally, whilst research has investigated how trainee teachers learn to teach, it has not addressed how they may start to use dialogue (Mills, 2004; Cain, 2011; Elgersma, 2012; Legette and Royo, 2021). The following research questions were formulated to address these gaps in the literature:

1. What are trainee instrumental/vocal teachers’ perceptions of using dialogic teaching in terms of potential advantages and disadvantages?

2. In which situations do trainee instrumental/vocal teachers use dialogic teaching? For example, when teaching musical expression, rhythm, pitch, or at-home practice, as found by Meissner and Timmers (2020).

3. Which activities do/have trainee instrumental/vocal teachers found helpful in developing their use of dialogic teaching?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 ‘Real-world’ impetus

Before discussing methodological considerations, it is important to outline why these research questions were pursued. Author 1 has completed the MA Music Education: Instrumental and Vocal Teaching programme at the University of York, in which a previous version of this article formed their independent study module. Author 2 was the supervisor of this submission. Prior to MA study Author 1 subconsciously adopted a master-apprentice approach (Jørgensen, 2000) as an instrumental teacher, rarely facilitating teacher-student dialogue. Shortly after enrolling on the MA programme at the University of York Author 1 watched a video recording of a one-to-one violin lesson taught by Author 2 that featured dialogic teaching. This was a ‘light-bulb’ moment as Author 1 suddenly became aware of the potential for teacher-student dialogue. Author 1 began experimenting with dialogue but was surprised to find that peers doubted its success or did not understand how they could develop this approach. As a result Author 1 became interested in exploring perceptions of this teaching strategy, and understanding how fellow trainee teachers on the MA programme may use dialogic teaching within their instrumental/vocal lessons. Both authors endeavour to engage their instrumental students through dialogue and remain committed to improving this aspect of their teaching.

2.2 Method

The research questions indicate a clear aim to provide practical recommendations to educators of trainee instrumental/vocal teachers. It was therefore decided that a pragmatic research philosophy would be taken to achieve this ‘real-world’ outcome (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Williamon et al., 2021). Furthermore, it became apparent that quantitative and qualitative data would be required to answer these research questions. Terrell (2012) suggests that quantitative data tells us ‘if’ whilst qualitative data indicates ‘how’ or ‘why’ (p. 258). It was anticipated that quantitative data would determine which experiences trainee teachers found useful when starting to use dialogic teaching, whilst qualitative data could explore how and why these activities supported the development of this teaching strategy. This would enable quantitative findings to be confirmed by qualitative data, and vice versa (Greene et al., 1989). It was anticipated that the unique relationship between Author 1 and Author 2, and their exploration of attitudes amongst trainee teachers toward lecture content delivered by Author 2, could result in findings that inform the delivery of the course at the University of York. This philosophy of method is similar to the reflective nature of action research that can lead to valuable outcomes for a larger group of individuals (Cain, 2008). The potential for hierarchical pressure to influence the discussion and analysis of results was effectively managed by both authors and further detail is provided in the ‘Ethical considerations’ section.

2.3 Materials

An online questionnaire was constructed (see Appendix A) due to its capability to collect quantitative and qualitative data through open and closed questions (Oppenheim, 1992; Sapsford, 2007; Williamon et al., 2021). The questionnaire was developed based on the above research questions and by adapting items from the questionnaire used to explore teacher perceptions of dialogic teaching within Meissner and Timmers’ (2020) study. This questionnaire was developed through domain and item generation,1 with content validity testing and pre-testing of questions also being conducted, as recommended by Boateng et al. (2018). The questionnaire was piloted with two students on the MA programme; both reported that it was clear and did not have any recommendations for improvement. These responses are not included in the final data set. The terms ‘questioning’ and ‘discussion’ are used throughout (rather than ‘dialogic teaching’) to enable trainee teachers who might not have been familiar with ‘dialogic teaching’ to respond. These two terms were chosen as they are described as ‘key areas’ of dialogic teaching (Alexander, 2020, p. 126). As a result, caution is taken when drawing conclusions about respondents’ attitudes toward ‘dialogic teaching’ within the ‘Results and discussion’ as respondents were answering questions about the terms ‘questioning’ and ‘discussion’.

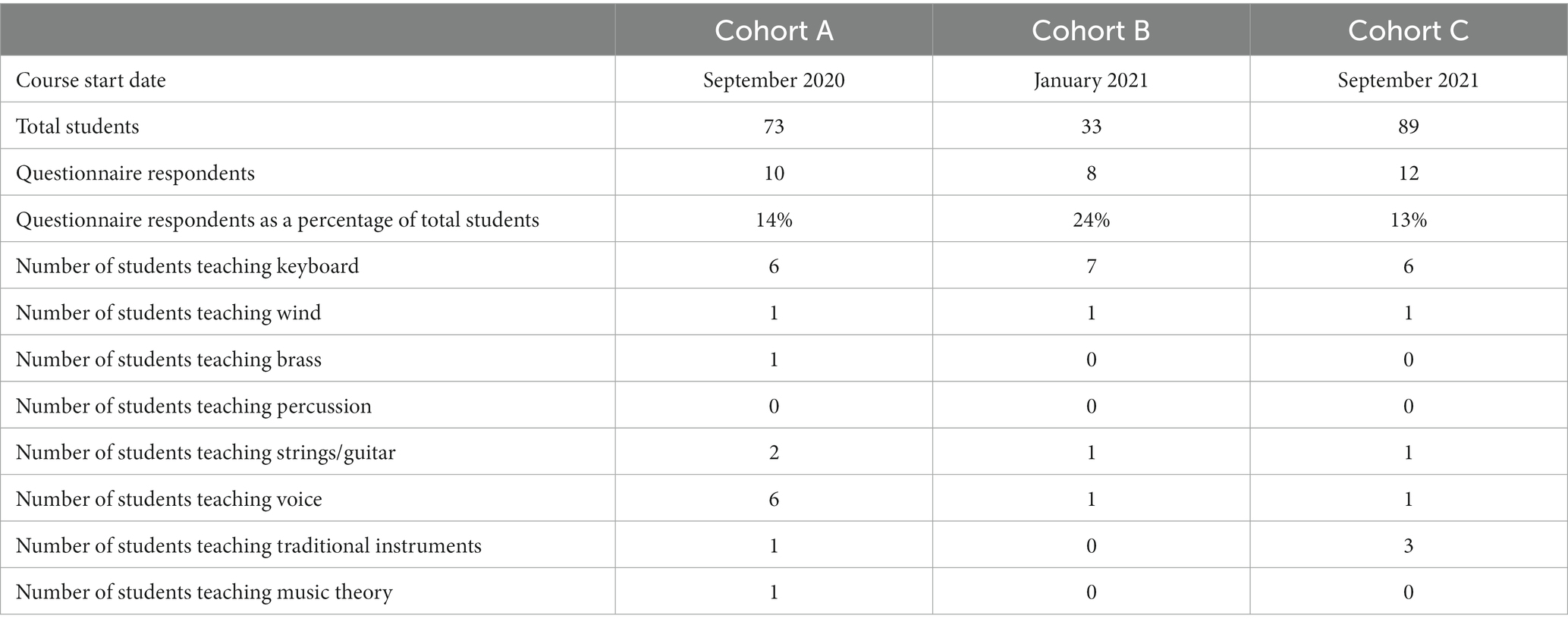

It was agreed that asking three cohorts of students on the MA programme to respond would help to gain a broad range of perceptions amongst trainee instrumental/vocal teachers (see Table 1). The three cohorts were invited to respond in October 2021. The first group of students (Cohort A) began the course in September 2020 and had completed all lecture content, course-related activities,2 and assignments by October 2021. Students in Cohort B enrolled in January 2021 and were able to engage in lecture content and course-related activities by October 2021, but had their dissertation still to complete. Cohort C students began their studies in September 2021 so had just gained access to online lecture content when invited to respond. Respondents were teaching in a variety of contexts; 16 of the 30 respondents taught on Zoom, 20 in teaching studios, 21 at pupils’ (or teachers’) homes, 10 in schools, two in higher education institutions, and two in specialist music schools. Table 1 also details the instruments taught by respondents in each cohort. The authors hoped to compare responses from all three cohorts and anticipated that responses from Cohorts A and B may pinpoint the experiences that supported trainee teachers to use dialogic teaching.

Table 1. Total students vs. questionnaire responses amongst MA Music Education: Instrumental and Vocal Teaching students at the University of York.

The questionnaire also asked respondents to identify as ‘home’ or ‘international’ students. A high proportion of trainee instrumental/vocal teachers that take part in the MA programme at the University of York are international students, most of whom are Chinese. Cultural backgrounds and educational experiences have the potential to influence perceptions of dialogue and its use in a variety of contexts. Teacher-student dialogue is often considered essential for effective teaching within western or UK educational contexts (Howe and Abedin, 2013; Mercer and Dawes, 2014) but classroom dialogue can occur less frequently in Asian schools, where it is sometimes difficult to facilitate due to class sizes and resources (Jin and Cortazzi, 1998; Li, 2005; Watkins, 2010). Research indicates that Chinese university students studying in the UK and USA may be reluctant to engage in questioning and discussion (Tran, 2013; Heng, 2018; Zhu and O’Sullivan, 2020). It was therefore vital to consider cultural backgrounds when investigating perceptions of dialogic teaching amongst students on the MA programme at the University of York.

2.4 Data analysis

Qualitative data were analysed by Author 1 using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). This analysis method was selected as Braun and Clarke (2006) suggest that it can ‘unpick or unravel the surface of reality’ (p. 81); thematic analysis could reveal why and how particular activities within the MA programme were useful for trainee teachers. A ‘top-down’ (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 83) approach was taken, allowing the analysis to focus on respondents’ perceptions of dialogue. The prevalence of themes was determined by the number of respondents that referred to a theme (rather than the number of occasions a theme was referred to) to understand the proportion of students that found a particular activity to be beneficial. The prevalence of individual themes is illustrated through frequency counts to indicate their ‘qualitative strength’ (Williamon et al., 2021, p. 253).

2.5 Ethical considerations

This research project was approved by the University of York Arts and Humanities Ethics Committee in September 2021. There was a risk that respondents would feel that their teaching was being questioned and both authors addressed this by ensuring that the wording of questions did not imply that there were more advantages to using ‘questioning and discussion’ than disadvantages. Respondents were also given the opportunity to explain their opinions within ‘Other’ text boxes (see Appendix A). As a contracted member of staff, Author 2 has a responsibility to protect the reputation and standing of the University; however, as part of a reflexive community committed to continual professional development the possibility of receiving negative comments about course teaching was not viewed as problematic because the response to address such criticism is more important than the comments themselves. Author 1 was reassured that this was the case and encouraged to represent results fully and honestly. This project was welcomed by the MA Music Education: Instrumental and Vocal Teaching Programme Leader at the time as an opportunity for reflective engagement with the course and both authors worked in consultation with them to develop the questionnaire. There was a danger that students who responded to the questionnaire may have felt compelled to give positive responses if they thought they could be identified or were concerned that their course outcome might be affected; the potential for this to influence results is acknowledged and discussed further within the ‘Results and discussion’. Despite this, all responses were anonymous and Author 1 processed the raw data and conducted the data analysis prior to Author 2 reviewing the findings for the purpose of publication. Throughout this research project Author 1 has been reflexive by acknowledging their own beliefs concerning the efficacy of questioning and discussion (Sapsford, 2007; Williamon et al., 2021). Author 1 aimed to prevent this from unfairly impacting data collection by providing opportunities for respondents to present their own ideas through text boxes in multiple-choice questions (see Appendix A). The authors also sought to understand perceptions concerning the disadvantages of using questioning and discussion and allowed respondents to detail activities outside of the MA programme that supported their development of this teaching strategy.

3 Results and discussion

Data gathered by the online questionnaire will be presented and discussed by addressing each research question in turn.

3.1 What are trainee instrumental/vocal teachers’ perceptions of using dialogic teaching in terms of potential advantages and disadvantages?

3.1.1 Perceived advantages of dialogic teaching

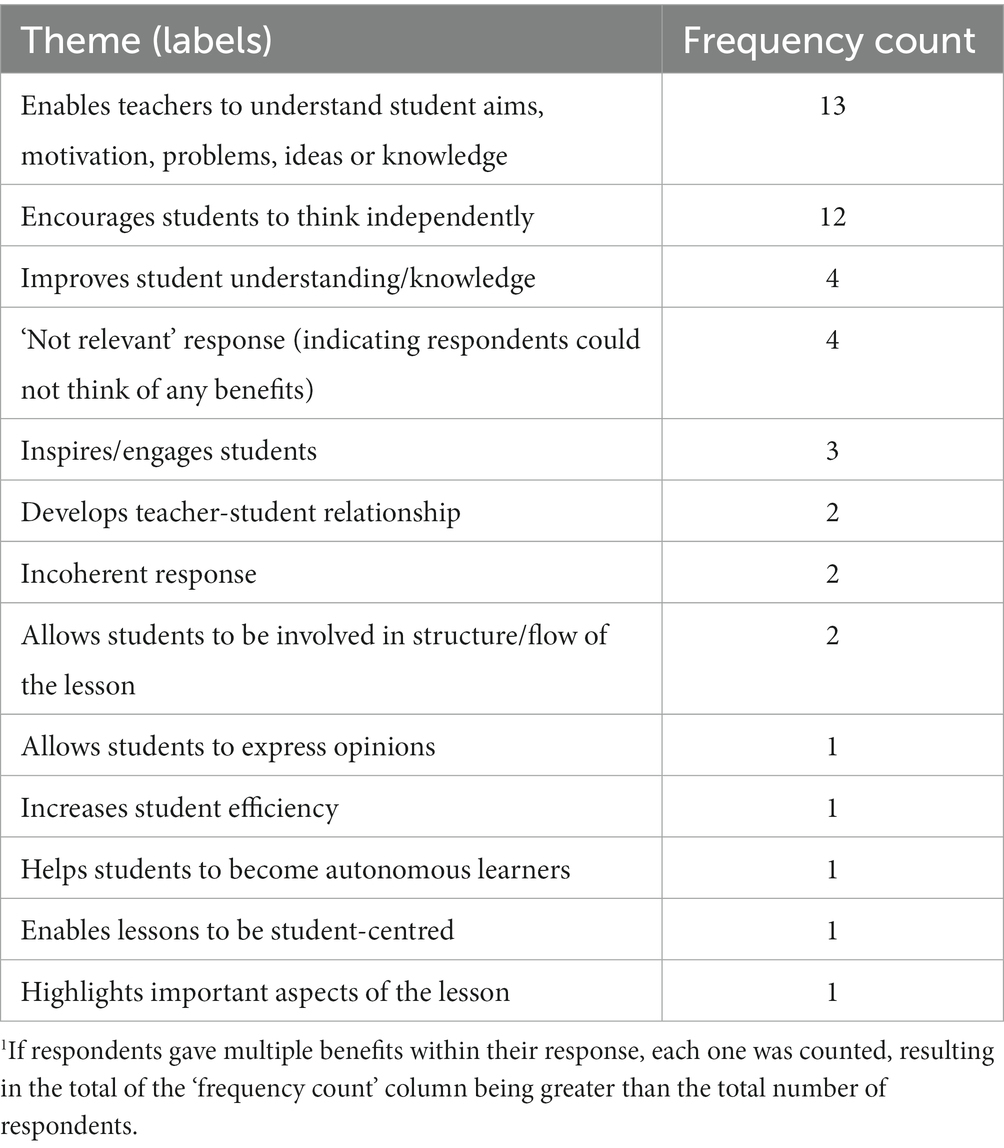

Respondents were required to give a written response (in an open text box) when asked to detail any advantages of questioning and discussion. These responses are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Themes developed from questionnaire responses concerning the perceived advantages of questioning and discussion (question 6, see Appendix A).1

Two themes were mentioned more frequently than any other: ‘encourages students to think independently’ and ‘enables teachers to understand student aims, motivation, problems, or knowledge’. For example, one respondent said:

‘The use of dialogue helps teachers to better understand students’ ideas and promote students’ thinking about the learning content’

Another respondent said that questions and discussion ‘let students think for themselves and get independent thinking abilities’. This supports literature that has found that dialogic teaching can encourage students to think independently (Meissner and Timmers, 2020; Meissner et al., 2021). Two respondents also reported that questioning and discussion improved the teacher-student relationship; this is corroborated by Meissner and Timmers’ (2020) study, which found that dialogue allowed teachers to ‘get to know’ (p. 11) their students. Indeed, one respondent said that questions and discussion ‘promote[s] pupils’ thinking and improves the relationships between teachers and students’ and one further respondent said:

‘It can exercise students’ self-thinking ability; teachers can more directly understand the students’ learning progress and requirements; can promote teacher-student relationship; make the lesson more students-centred.’

All four ‘not relevant’ responses (indicating that respondents could not think of any advantages of questioning and discussion) came from respondents identifying as international students, with three of these responses being Cohort C students. This may indicate that international students in this research project were less likely to be aware of any associated benefits of using questioning and discussion when beginning the MA programme. Three of these international students reported that their own instrumental teachers had inconsistently used questioning and discussion. Furthermore, two of these respondents believed their teacher’s questioning and discussion was ‘ineffective’. In contrast, eight (80%) home students reported that they experienced questioning and discussion to some extent in their own instrumental/vocal learning and all home students believed questioning and discussion was either ‘very effective’, ‘effective’ or ‘quite effective’. This indicates that international students had more varied perceptions concerning the success of questioning and discussion within their own learning and had more limited experiences of this teaching strategy than home students.

It is worth acknowledging that the trainee instrumental/vocal teachers were responding to this questionnaire whilst completing their MA programme and that their perceptions of questioning and discussion may have changed following graduation. Indeed, research in the field of science has found that trainee science teachers adapted their teaching beliefs following their preparation programme, as five trainee teachers in one study favoured reform-based teaching3 during their training but then considered a ‘didactic’ (p. 1124) style of teaching more effective during their first year of teaching (Fletcher and Luft, 2011). The researchers argue that enhanced longitudinal support is needed to support in-service teachers in developing reform-based teaching (Fletcher and Luft, 2011). Lowell and McNeill (2022) conducted a 2-year study with 322 US science teachers and found that a series of professional development opportunities encouraging teachers to facilitate whole-class discussion resulted in participants gradually increasing their ‘self-efficacy beliefs’ (p. 1457) and being less likely to hold ‘traditional’ (p. 1458) teaching beliefs. Lowell and McNeill (2022) go on to suggest that development of teaching practice takes place ‘over time’ (p. 1481). This may indicate that the trainee instrumental/vocal teachers in this study may have altered their perceptions of questioning and discussion following the completion of their course, and that further research could explore longitudinal support that may be offered to instrumental/vocal teachers as they develop their use of this teaching strategy.

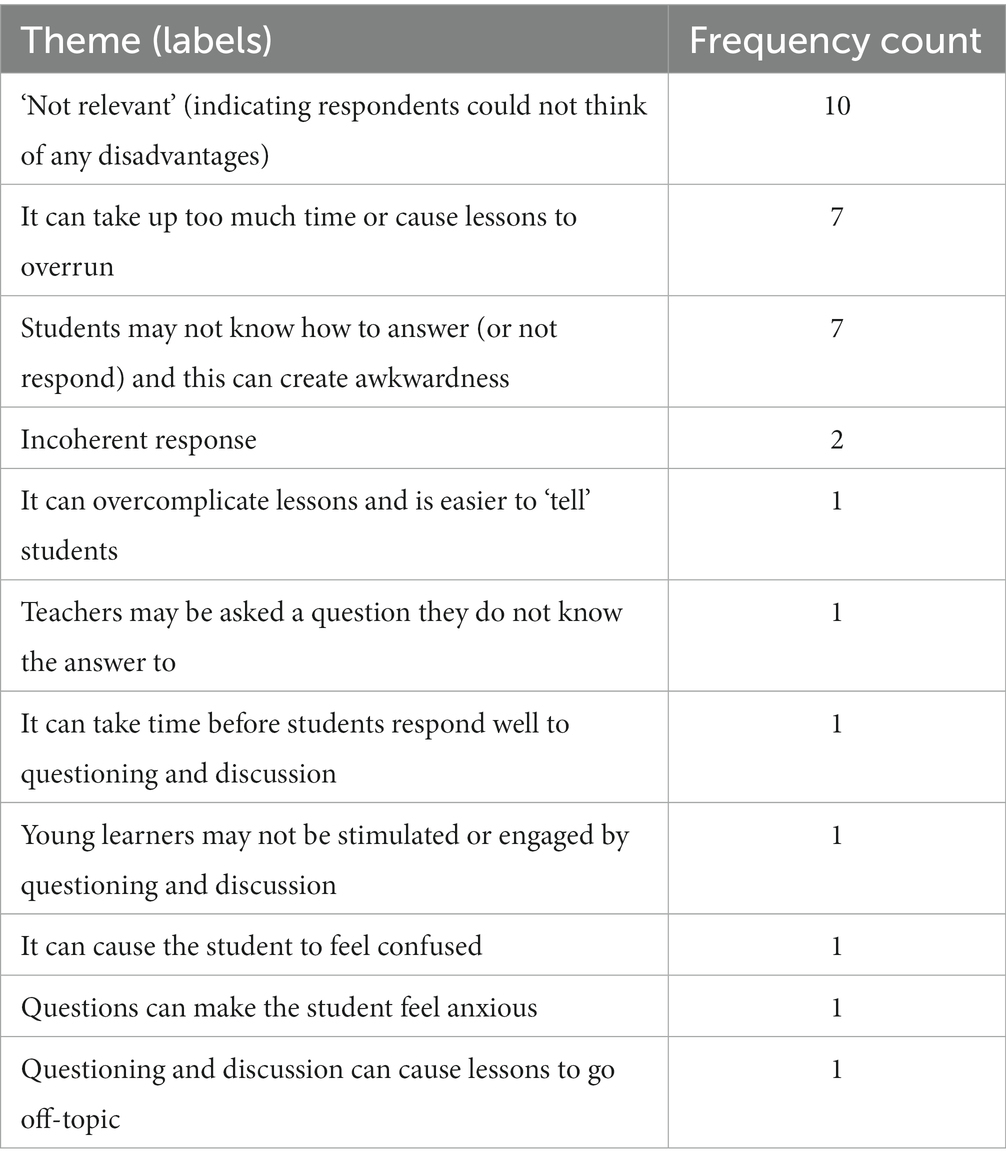

3.1.2 Perceived disadvantages of dialogic teaching

Respondents were also asked to outline any disadvantages they believed to be associated with questioning and discussion in an open text box: see Table 3 for results. The most common response (ten respondents) was ‘not relevant’, indicating that these respondents did not provide any disadvantages. This does not necessarily imply that these respondents believe questioning and discussion does not have any associated disadvantages; it is perhaps more indicative of them being unable or unwilling to provide any while completing the questionnaire.

Table 3. Themes developed from questionnaire responses concerning the perceived disadvantages of questioning and discussion (question 7, see Appendix A).

Seven respondents indicated that questioning and discussion can cause lessons to overrun. This is supported by one teacher within one university music department in Burwell’s (2012) study who cited exam-related time constraints as a reason for not asking questions. This may highlight the need for trainee teachers to learn how to use dialogic teaching within limited time frames.

Seven respondents also suggested that students may not know how to respond to questions and discussion. This suggests that trainee teachers within this research may benefit from understanding that students can require time to become accustomed to this teaching strategy.

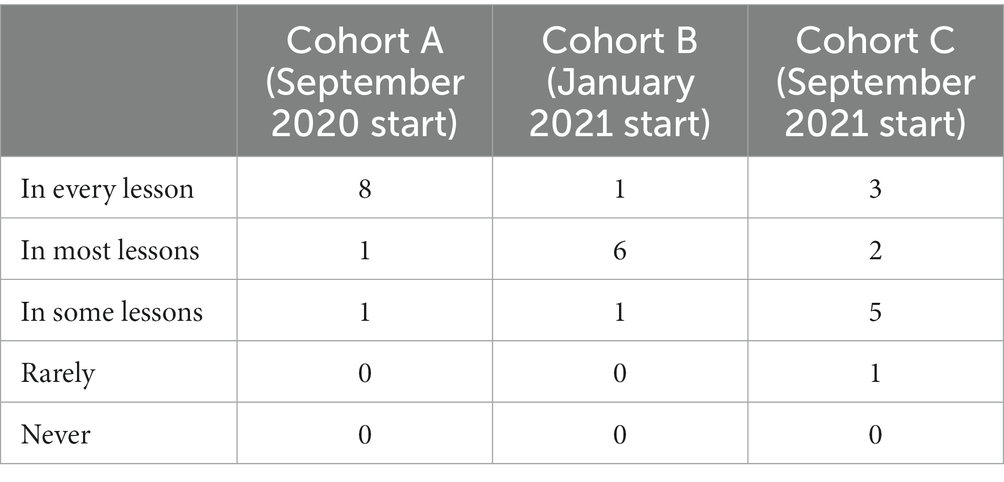

Overall, respondents gave a greater number of advantages (13, see Table 2) than disadvantages (11, see Table 3). This does not necessarily indicate that respondents are more likely to use questioning and discussion as quantitative data revealed that only 12 respondents (41%) reported that they used questioning and discussion in every lesson, whilst 17 (57%) suggested that their use of this strategy was more inconsistent. Of these 17 respondents, one said that they ‘rarely’ employ this teaching method, seven claimed they use this approach in ‘some’ lessons, and nine said that they use questions and discussion in ‘most’ lessons. This data seems to suggest that these trainee teachers used questioning and discussion more frequently than the instrumental/vocal teachers in Burwell (2019) and Warnet’s (2020) studies.

When this data is analysed by cohort (see Table 4), it becomes apparent that respondents in Cohorts A and B are more likely to claim that they use questioning and discussion. Eight (80%) of Cohort A students suggest that they employ questioning and discussion in ‘every’ lesson whilst six (75%) Cohort B students reported they used this strategy in ‘most’ lessons. The most popular response within Cohort C was that respondents adopted this approach in only ‘some’ lessons (five respondents), with one reporting that they ‘rarely’ use questions and discussion and three in ‘most’ lessons. This suggests that respondents that had progressed through the MA programme (Cohorts A and B) were more likely to believe they consistently use dialogue. Alternatively, respondents within Cohorts A and B may claim that they are more confident in using questioning and discussion because, after engaging with course content, they believe that the teaching team would expect them to employ this strategy. Caution must be taken before generalising from these responses which could have been influenced by ‘demand characteristics’4 (Williamon et al., 2021, p. 428).

Table 4. Questionnaire data indicating the frequency in which respondents (by cohort) used questions and discussion (question 12, see Appendix A).

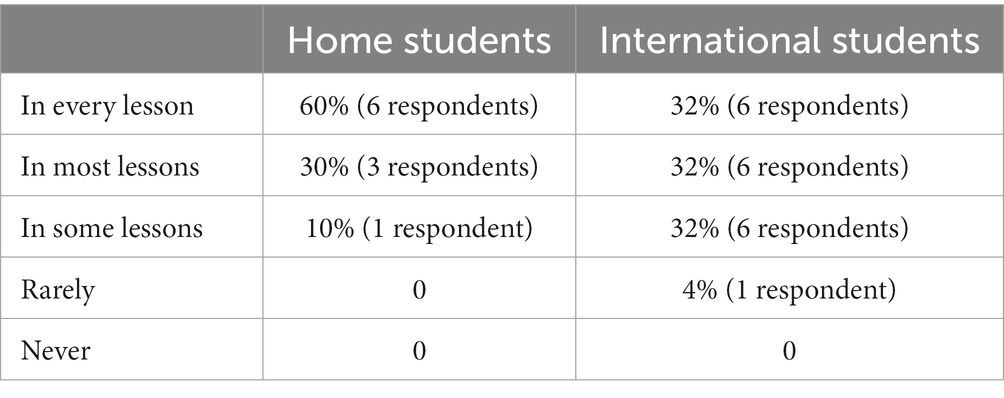

This data was also analysed by student identification (‘home’ or ‘international’, see Table 5), which revealed that home students were more likely to claim that they use questioning and discussion than international students. Six respondents (60%) identifying as ‘home’ students reported using questioning and discussion in every lesson, compared with six international students (32%). Of the eight respondents claiming that they use questioning and discussion in ‘some’ lessons or ‘rarely’, seven were international students and six were in Cohort C.

Table 5. Questionnaire data indicating the frequency in which respondents (by home/international student) used questions and discussion (question 12, see Appendix A).

This could indicate that international students at the beginning of the MA programme were less likely to use questioning and discussion. This also supports research that has found that Chinese students studying in the UK and USA may be reluctant to engage in dialogue (Tran, 2013; Heng, 2018; Zhu and O’Sullivan, 2020). Given that international students were found to have more varied perceptions of questioning and discussion as learners and be less likely to use this teaching strategy in every lesson, further insight into their studio teaching experiences may improve our understanding of the learning environments they are accustomed to, and how this may impact their use of questioning and discussion.

3.2 In which situations do trainee instrumental/vocal teachers use dialogic teaching?

Respondents were also asked to select topics that they would approach using questioning and discussion through a multiple-choice item (see Figure 1). The two most frequently selected responses were ‘musical expression’ (21 respondents) and ‘practice’ (21 respondents).5 This supports existing literature that has found that dialogic teaching is effective in developing musical expression (Meissner, 2017; Meissner and Timmers, 2019; Meissner et al., 2021).

Figure 1. Questionnaire data revealing the number of musical topics respondents claimed they would approach using questioning and discussion (question 9, see Appendix A).

Meissner and Timmers’ (2020) research also found that dialogic teaching was useful in discussing performance directions, pitch, rhythm, technical accuracy, and practice. This indicates that dialogic teaching may be successful when discussing a variety of topics. Of the 12 respondents that selected ‘any topic’, eight were from Cohorts A and B, suggesting that respondents who had engaged with the course content were more likely to use questioning and discussion when teaching a wider range of topics. Again, this could suggest that respondents who had engaged with the course content had responded in a way that they thought might be expected of them as students enrolled on the MA programme, even if they may not regularly use this teaching strategy.

Of the remaining 17 respondents that did not select ‘any topic’, those in Cohorts A and B were more likely to claim that they use questioning and discussion to teach a larger number of topics than respondents in Cohort C. Cohort A respondents gave a mean average of 3.5 topics and students in Cohort B listed a mean average of 3.7 topics. This contrasts with Cohort C respondents who selected a mean average of 3.1 topics.

3.3 Which activities do/have trainee instrumental/vocal teachers found helpful in developing their use of dialogic teaching?

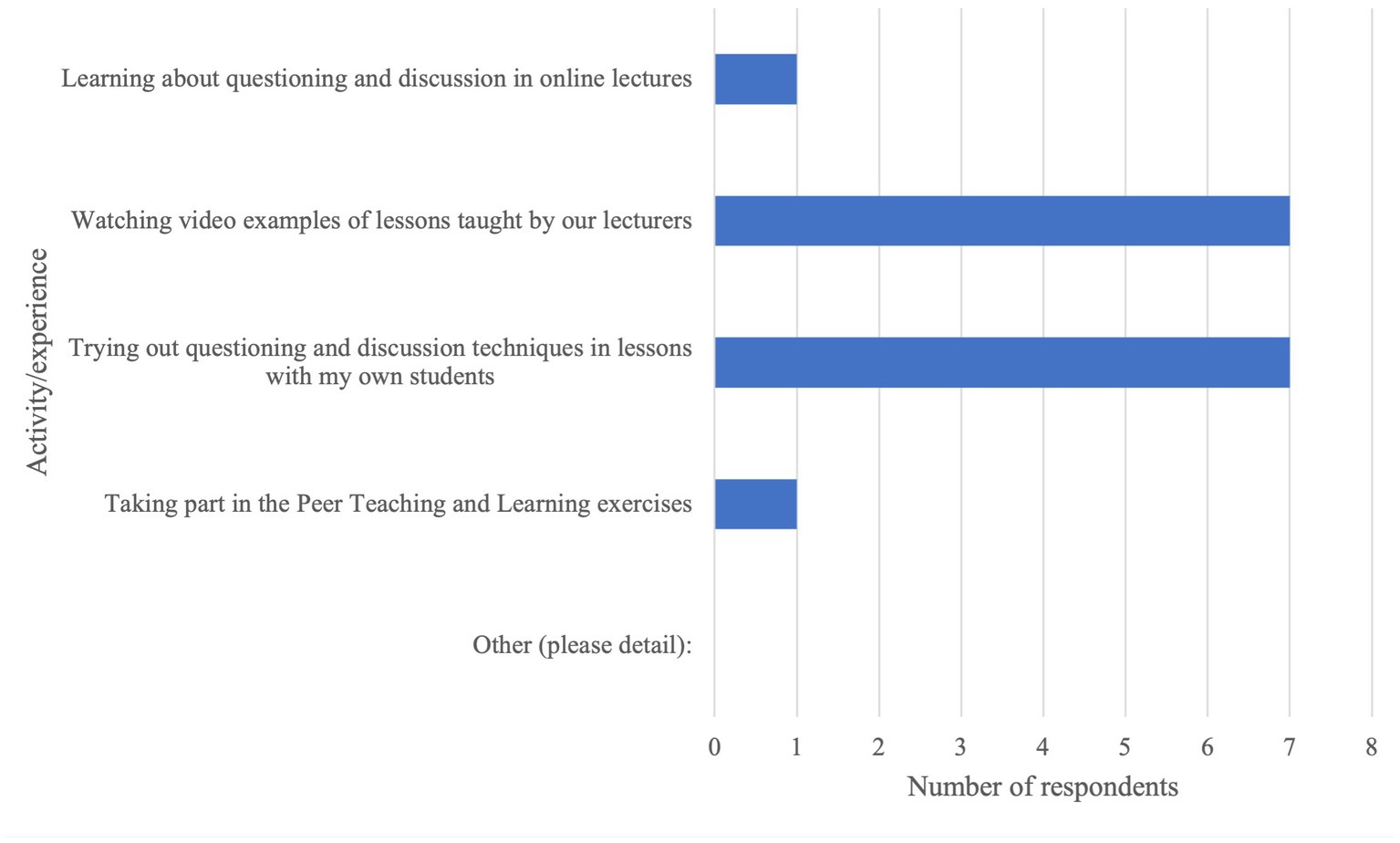

When respondents from Cohorts A and B were asked to specify activities that were most helpful when starting to use questioning and discussion, two activities were selected more frequently than any other: ‘watching video examples of lessons taught by our lecturers’ and ‘trying out questioning and discussion in lessons with my own students’ (see Figure 2). This supports findings from Conkling (2003), Mills (2004), and Legette and Royo’s (2021) research which found observation to be successful in supporting trainee teachers, whilst Mills (2004) and Haddon’s (2009) studies indicated that gaining teaching experience was helpful.

Figure 2. Quantitative data indicating the number of respondents that considered each activity to be the most helpful when starting to use questioning and discussion (question 14, see Appendix A).

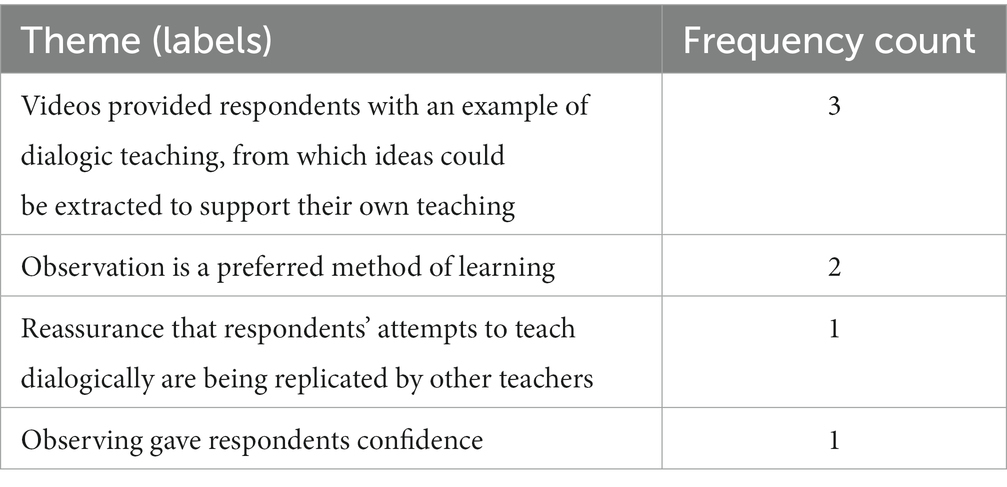

Respondents were then asked to give reasons for these choices through written responses; answers from those that found watching video examples of questioning and discussion to be most helpful were thematically analysed: see Table 6.

Table 6. Reasons for ‘watching video examples of lessons taught by our lecturers’ being the most helpful activity when starting to use questioning and discussion (question 15, see Appendix A).

The most frequently cited theme was that observing video examples enabled respondents to incorporate ideas within their own teaching. One respondent said:

‘Watching the video can more directly know where to use the problem, how to use, how to better interact with students.’

Another respondent said ‘I can learn how to use this skill from the lecturer’s example’, suggesting that trainee teachers may benefit from observing teachers that use questioning and discussion.

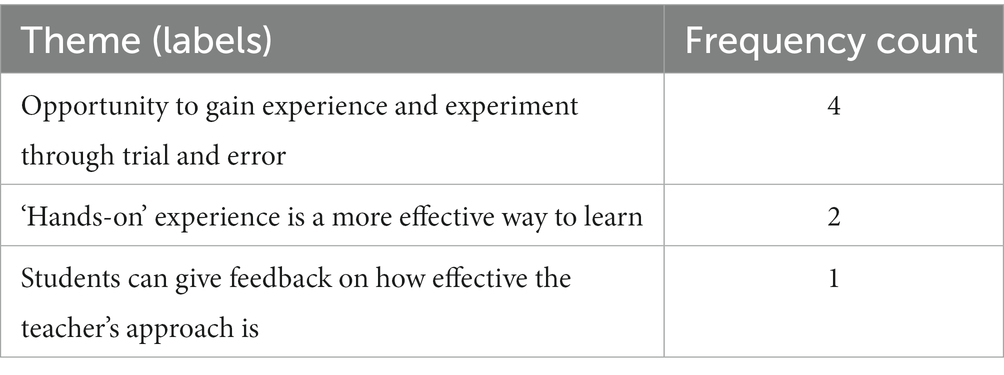

Responses from students claiming that practical teaching experience was the most helpful are shown in Table 7.

Table 7. Reasons for ‘trying out questioning and discussion techniques in lessons with my own students’ being the most helpful activity in starting to use questioning and discussion (question 15, see Appendix A).

The most popular theme suggests that gaining practical teaching experience allows trainee teachers to experiment with questioning and discussion through ‘trial and error’. One respondent said:

‘I can adjust the questions I use in the lesson according to the requirements of the students. This is a process of progress.’

Another respondent said ‘It gave me the chance to experiment within actual lessons’. The word ‘experiment’ indicates that they may have to step outside of their comfort zone when beginning to use dialogue, and this may be challenging. In addition, this respondent said:

‘Most of my students knew I was studying toward this MA so they didn’t mind me trying different teaching techniques.’

This suggests that trainee teachers starting to use dialogue may require students who are happy for their teacher to experiment, whilst trainee teachers might need to feel comfortable within the environments they are experimenting.

Future research could also corroborate these findings with data from other institutions; this research is limited in the extent to which data can be generalised as findings relate to trainee teachers within one MA programme at one university, with only 30 students (out of a total of 195) responding to the questionnaire (Cohen et al., 2017; Williamon et al., 2021). Furthermore, these findings do not explain how respondents determine what constitutes a ‘better interaction’. For example, the lecture content that accompanied the video examples may have influenced respondents’ understanding. Whilst the above data provides insight into how these trainee teachers started using questioning and discussion, it does not reveal how they come to understand what constitutes ‘questioning’ or ‘discussion’, or why it may be useful. Exploring this was beyond the scope of this research but this information could be of further relevance to educators of trainee instrumental/vocal teachers.

3.3.1 Activities outside the MA programme

Respondents were also asked to detail any experiences outside of the MA programme that supported their use of questioning and discussion. One respondent explained that they observed colleagues working within a teaching studio:

‘I was working as a music teacher in my country so I had a good experience by visiting my colleagues in my workplace in their classes. Most of them was using the questioning.’

Another said ‘my violin teacher kept asking me questions so I could find the answers on my own’, again indicating that watching other teachers helps trainee teachers to start using questioning and discussion.

One respondent reported that ‘talking about questions with other educators’ supported their use of this teaching method. This reiterates a theme found within the qualitative data that explained why observing the video examples was effective: one respondent reported that it was helpful to see that peers were using similar strategies (see Table 7). Furthermore, one respondent also cited the peer teaching and learning exercises6 as the most helpful activity within the MA programme (see Figure 2), suggesting that peer-to-peer discussion may be valued by some respondents. This also supports research that has found collective discussion to be appreciated by trainee classroom music teachers (Ballantyne, 2006; Cain, 2011; Elgersma, 2012). Given that respondents indicated that using questioning and discussion is a ‘process’ and can take time, trainee teachers may value group discussions that take place throughout their course. As a result of these findings, the teaching team at the University of York scheduled two peer-to-peer discussions inviting students to discuss questioning and discussion within their teaching. Future research could explore how (or if) this supported students in using questioning and discussion.

All three of the above responses only mention ‘questioning’, despite this questionnaire referring to questioning and discussion (see Appendix A). Additionally, in written responses that explained why particular activities were useful in developing this teaching strategy, three respondents (just under one fifth of respondents that answered this question) mention ‘questioning’ without referring to ‘discussion’. Only one response includes both ‘questioning’ and ‘discussion’. The omission of ‘discussion’ within responses may suggest that respondents could benefit from understanding that dialogic teaching consists of more than teacher-led questioning. Trainee teachers may benefit from discussing how they can build on student responses to facilitate discussion. Perhaps this also highlights the need for trainee teachers to consolidate their understanding of what is implied by ‘questioning and discussion’ and ‘dialogic teaching’ in relation to instrumental/vocal pedagogy. Alexander (2020) describes dialogic teaching in relation to classroom education, but research projects investigating dialogic teaching within instrumental/vocal lessons have primarily examined its efficacy and provided limited detail concerning what this practically involves for teachers (Meissner, 2017; Meissner and Timmers, 2020). Although Meissner (2021) suggests that dialogic teaching is effective and recommends strategies that incorporate this teaching strategy, this advice has been created exclusively for the teaching of musical expression, rather than the variety of topics that could be taught using dialogic teaching. Furthermore, Meissner (2021) does not provide practical suggestions that indicate how teacher-led questioning can lead to teacher-student exchanges. The exclusion of ‘discussion’ within responses to this questionnaire suggests that practical advice may be helpful for trainee instrumental/vocal teachers, together with an enhanced understanding of what dialogic teaching can involve within instrumental/vocal lessons. A number of studies have investigated the implementation of dialogic teaching within science classroom teaching contexts (Kubli, 2005; Rahmawati and Koul, 2016; France, 2021); however, the context in which instrumental/vocal learning takes place can be quite different to whole-class settings. Data from ABRSM’s (2021) survey of 2,485 instrumental/vocal teachers found that 94% of teachers provide one-to-one lessons and 57% of these teachers exclusively deliver one-to-one lessons. This is likely to impact how and when instrumental/vocal teachers choose to facilitate dialogue and collaborate with students as a ‘collective’ to ‘address learning tasks together’ (Alexander, 2020, p. 131). The unique context in which a large proportion of instrumental/vocal learning takes place underlines the need for further understanding and practical advice to support trainee teachers in these environments.

Finally, caution should be taken when drawing conclusions about respondents’ attitudes toward dialogic teaching; respondents were asked about ‘questioning and discussion’ and, whilst questioning and discussion are ‘key areas’ of the dialogic teaching framework (Alexander, 2020, p. 126), respondents were not answering questions that explicitly referred to dialogic teaching. Findings give a suggestion of respondents’ perceptions and further study could corroborate these findings by giving participants a description (or perhaps an example) of dialogic teaching within the context of instrumental/vocal teaching before asking about their experiences. This could enhance understanding of trainee instrumental/vocal teachers’ perceptions of dialogic teaching and how they learn to develop dialogic teaching skills.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, respondents reported that the primary advantages of questioning and discussion include the potential for improvements to the teacher-student relationship and the development of independent thinking amongst students. The most frequently cited disadvantages were unenthusiastic (or non-existent) student responses and the potential for lessons to overrun. Trainee teachers that had progressed through the MA Music Education: Instrumental and Vocal Teaching programme at the University of York (Cohorts A and B) more often claimed that they were more likely to use questions and discussion in ‘every’ or ‘most’ lessons than trainee teachers from Cohort C. Furthermore, respondents in Cohorts A and B were more confident in using questioning and discussion and claimed to use this approach when discussing a larger number of topics than respondents in Cohort C (who had just started their MA course when they responded).

Observing questioning and discussion and accumulating practical teaching experience were the most frequently cited activities that enabled trainee teachers to start using this teaching strategy. This research has found that trainee teachers may require ‘safe’ environments in which to experiment, as well as students that are happy for teachers to trial new teaching methods. Discussing questioning and discussion with peers was also described as helpful as it allowed respondents to share and learn from experiences. Further study could examine the efficacy of peer-to-peer discussions concerning dialogue that took place amongst students on the MA programme at the University of York as a result of this research.

Findings from this research provide an indication of trainee instrumental/vocal teachers’ perceptions of dialogic teaching; these findings could be corroborated by further research that provides participants with a clear explanation (or example) of dialogic teaching before investigating their experiences and perceptions. Future study could also compare responses from trainee instrumental/vocal teachers at other institutions as the data presented in this research represents the perceptions of only 16% of three student cohorts from one institution.

Despite these limitations, this research reveals a lack of certainty concerning the characteristics of ‘questioning and discussion’ and dialogic teaching; some trainee teachers prioritised teacher-led questioning over two-way discussion. This suggests that trainee instrumental/vocal teachers would benefit from learning to build on student responses to create two-way discussion and indicates that future research could determine the hallmarks of dialogic teaching within instrumental/vocal contexts for the benefit of future trainee teachers and their (future) students.

Data availability statement

The anonymous raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study involving humans was approved by the University of York Arts and Humanities Ethics Committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JP: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NN: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The University of York funded the publication of this manuscript through the York Open Access Fund.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the trainee instrumental/vocal teachers who took part in this research and Elizabeth Haddon (MA Music Education: Instrumental and Vocal Teaching Programme Leader at the time) for supporting the development of the questionnaire.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1272325/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The first process in the development of an original questionnaire, as stipulated by Boateng et al. (2018). This involves deciding what will be measured and selecting the items that will appear within the questionnaire.

2. ^The MA Music Education: Instrumental and Vocal Teaching programme at the University of York promotes questioning and teacher-student discussion through a range of resources and activities, including exemplary lesson recordings (produced by the teaching team), lecture content, and tutor group discussions (University of York, 2023).

3. ^Reform-based teaching methods encourage students to play an active role in their learning through whole-class discussion and reflection (Sherin, 2002; Gabriele and Joram, 2007; Fletcher and Luft, 2011).

4. ^The term ‘demand characteristics’ refers to respondents being influenced by the perceived beliefs or assumptions of the researcher(s) (Williamon et al., 2021, p.428).

5. ^One Cohort C respondent said that they had not started teaching instrumental or vocal lessons yet; their response to this question (question 9) is therefore not included in Figure 1.

6. ^Peer teaching and learning exercises involve students on the MA Music Education programme at the University of York submitting a 5-min video recording of a lesson to discuss with peers and one member of the teaching team. Constructive criticism and praise is shared with all students.

References

ABRSM. (2021). Making music: Learning, playing and teaching in the UK. Available at: https://gb.abrsm.org/media/66373/web_abrsm-making-music-uk-21.pdf Accessed September 27, 2023.

Ballantyne, J. (2006). Reconceptualising preservice teacher education courses for music teachers: the importance of pedagogical content knowledge and skills and professional knowledge and skills. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 26, 37–50. doi: 10.1177/1321103X060260010101

Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., and Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioural research: a primer. Front. Public Health 6, 1–18. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Burwell, K. (2018). Coaching and feedback in the exercise periods of advanced studio voice lessons. Orfeu 3, 11–35. doi: 10.5965/2525530403012018011

Burwell, K. (2019). Issues of dissonance in advanced studio lessons. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 41, 3–17. doi: 10.1177/1321103X18771797

Cain, T. (2008). The characteristics of action research in music education. Br. J. Music Educ. 25, 283–313. doi: 10.1017/S0265051708008115

Cain, T. (2011). How trainee music teachers learn about teaching by talking to each other: an action research study. Int. J. Music. Educ. 29, 141–154. doi: 10.1177/0255761410396961

Cazden, C. (1996). “Vygotsky, Hymes, and Bakhtin: from word to utterance and voice” in Contexts for learning: Sociocultural dynamics in Children’s development. eds. E. A. Forman, N. Minick, and C. A. Stone (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 197–212.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education, 8th. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Conkling, S. W. (2003). Uncovering preservice music teachers’ reflective thinking: making sense of learning to teach. Bull. Council Res. Music Educ. 155, 11–23.

Daniel, H. (2016). “Vygotsky and dialogic pedagogy” in Dialogic pedagogy: The importance of dialogue in teaching and learning. eds. D. Skidmore and K. Murakami (Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters), 48–67.

Delp, V. (2004). “Voices in dialogue – multivoiced discourses in ideological becoming” in Bakhtinian perspectives on language, literacy, and learning. eds. A. F. Ball, S. W. Freedman, and R. Pea (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 203–212.

Elgersma, K. (2012). First year teacher of first year teachers: a reflection on teacher training in the field of piano pedagogy. Int. J. Music. Educ. 30, 409–424. doi: 10.1177/0255761412462970

Fletcher, S. S., and Luft, J. A. (2011). Early career secondary science teachers: a longitudinal study of beliefs in relation to field experiences. Sci. Educ. 95, 1124–1146. doi: 10.1002/sce.20450

France, A. (2021). Teachers using dialogue to support science learning in the primary classroom. Res. Sci. Educ. 51, 845–859. doi: 10.1007/s11165-019-09863-3

Freire, P., and Shore, I. (1987). A pedagogy for liberation: Dialogues on transforming education. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

Gabriele, A. J., and Joram, E. (2007). Teachers’ reflections on their reform-based teaching in mathematics: implications for the development of teacher self-efficacy. Action Teach. Educ. 29, 60–74. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2007.10463461

Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., and Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-methods evaluation designs. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 11, 255–274. doi: 10.2307/1163620

Haddon, E. (2009). Instrumental and vocal teaching: how do students learn to teach? Br. J. Music Educ. 26, 57–70. doi: 10.1017/S0265051708008279

Heng, T. T. (2018). Different is not deficient: contradicting stereotypes of Chinese international students in US higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 43, 22–36. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2016.1152466

Howe, C., and Abedin, M. (2013). Classroom dialogue: a systematic review across four decades of research. Camb. J. Educ. 43, 325–356. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2013.786024

Hughes, J. (2005). Improving communication skills in student music teachers. Part two: questioning skills. Music. Educ. Res. 7, 83–99. doi: 10.1080/14613800500042158

Jin, L., and Cortazzi, M. (1998). Dimensions of dialogue: large classes in China. Int. J. Educ. Res. 29, 739–761. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(98)00061-5

Johnson, R. B., and Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: a research paradigm whose time has come. Educ. Res. 33, 14–26. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033007014

Jørgensen, H. (2000). Student learning in high instrumental education: who is responsible? Br. J. Music Educ. 17, 67–77. doi: 10.1017/S0265051700000164

Kubli, F. (2005). Science teaching as a dialogue – Bakhtin, Vygotsky and some applications in the classroom. Sci. & Educ. 14, 501–534. doi: 10.1007/s11191-004-8046-7

Legette, R., and Royo, J. (2021). Preservice music teacher perceptions of peer feedback. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 43, 22–38. doi: 10.1177/1321103X19862298

Li, J. (2005). Mind or virtue: Western and Chinese beliefs about learning. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 14, 190–194. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00362.x

Lowell, B. R., and McNeill, K. L. (2022). Changes in teachers’ beliefs: a longitudinal study of science teachers engaging in storyline curriculum-based professional development. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 60, 1457–1487. doi: 10.1002/tea.21839

Meissner, H. (2017). Instrumental teachers' instructional strategies for facilitating children's learning of expressive music performance: an exploratory study. Int. J. Music. Educ. 35, 118–135. doi: 10.1177/0255761416643850

Meissner, H. (2021). Theoretical framework for facilitating young musicians’ learning of expressive performance. Front. Psychol. 11, 1–21. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.584171

Meissner, H., and Timmers, R. (2019). Teaching young musicians expressive performance: an experimental study. Music. Educ. Res. 21, 20–39. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2018.1465031

Meissner, H., and Timmers, R. (2020). Young musicians' learning of expressive performance: the importance of dialogic teaching and modelling. Front. Educ. 5, 1–21. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00011

Meissner, H., Timmers, R., and Pitts, S. (2021). Just notes': Young musicians' perspectives on learning expressive performance. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 43, 451–464. doi: 10.1177/1321103X19899171

Mercer, N., and Dawes, L. (2014). The study of talk between teachers and students, from the 1970s until the 2010s. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 40, 430–445. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2014.934087

Mills, J. (2004). Working in music: the conservatoire professor. Br. J. Music Educ. 21, 179–198. doi: 10.1017/S0265051704005698

Norton, N., Ginsborg, J., and Greasley, A. (2019). Instrumental and vocal teachers in the United Kingdom: demographic characteristics, educational pathways, and beliefs about qualification requirements. Music. Educ. Res. 21, 560–581. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2019.1656181

Nystrand, M. (1997). Opening dialogue: Understanding the dynamics of dialogue and learning in the English classroom. London, UK: Teachers College Press.

Oppenheim, A. N. (1992). Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement. London, UK: Pinter.

Rahmawati, Y., and Koul, R. (2016). Fieldwork, co-teaching and co-generative dialogue in lower secondary school environmental science. Issue Educ Res. 26, 147–164.

Sherin, M. G. (2002). When teaching becomes learning. Cogn. Instr. 20, 119–150. doi: 10.1207/S1532690XCI2002_1

Skidmore, D. (2000). From pedagogical dialogue to dialogical pedagogy. Lang. Educ. 14, 283–296. doi: 10.1080/0950078000866794

Skidmore, D. (2016). “Pedagogy and dialogue” in Dialogic pedagogy: The importance of dialogue in teaching and learning. eds. D. Skidmore and K. Murakami (Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters), 98–110. doi: 10.21832/9781783096220-007

Tran, T. T. (2013). Is the learning approach of students from the Confucian heritage culture problematic? Educ. Res. Policy Prac. 12, 57–65. doi: 10.1007/s10671-012-9131-3

University of York. (2023). MA music education: Instrumental and vocal teaching. Available at: https://www.york.ac.uk/study/postgraduate-taught/courses/ma-music-education/#course-content Accessed July 27, 2023.

Warnet, V. (2020). Verbal behaviours of instrumental music teachers in secondary classrooms: a review of literature. Update: applications of research in music. Education 39, 8–16. doi: 10.1177/8755123320924827

Watkins, D. (2010). Learning and teaching: a cross-cultural perspective. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 20, 161–173. doi: 10.1080/13632430050011407

Wegerif, R. (2011). Towards a dialogic theory of how children learn to think. Think. Skills Creat. 6, 179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2011.08.002

Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic inquiry: Towards a sociocultural practice and theory of education. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

West, T., and Rostvall, A. (2003). A study of interaction and learning in instrumental teaching. Int. J. Music. Educ. os-40, 16–27. doi: 10.1177/025576140304000103

Williamon, A., Ginsborg, J., Perkins, R., and Waddell, G. (2021). Performing music research: Methods in music education, psychology and performance science. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Keywords: dialogic teaching, dialogic pedagogy, instrumental/vocal teaching, trainee instrumental/vocal teachers, questioning, discussion

Citation: Poole J and Norton N (2023) Investigating trainee instrumental/vocal teachers’ perceptions of dialogic teaching: an exploratory study. Front. Educ. 8:1272325. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1272325

Edited by:

Renee Timmers, The University of Sheffield, United KingdomReviewed by:

Henrique Meissner, Hanze University of Applied Sciences, NetherlandsSami Lehesvuori, University of Jyväskylä, Finland

Copyright © 2023 Poole and Norton. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: James Poole, amFtZXMucG9vbGVAYWx1bW5pLnlvcmsuYWMudWs=

James Poole

James Poole Naomi Norton

Naomi Norton