- 1Graduate School of Advanced Integrated Studies in Human Survivability, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan

- 2Graduate School of Education, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan

Introduction: The ideal second/foreign language (L2) self, a concept in second-language acquisition theory, is a learner’s future vision about their language ability. Research on the ideal L2 self is important for finding ways to improve motivation for learning a new language, foreign language teaching strategies, and personalization of instruction for individuals with different backgrounds and aspirations. The present study aimed to better understand the factors that might influence the ideal L2 self among Japanese elementary school students. While there have been numerous studies about the ideal L2 self in English language learning, few have focused on elementary school students’ motivation to learn English.

Methods: Data were collected from 225 4th- and 6th-grade elementary school students in Japan. The data were analyzed by performing t-tests and a hierarchical linear regression to understand the relationships between the pertinent variables and the ideal L2 self.

Results: The analysis results revealed three characteristics of the relationship between elementary school students’ English language skills and their ideal L2 selves. First, the results of the t-test suggested that international travel and English cram school experiences were differentiating factors for the ideal L2 self, suggesting that the groups of participants with and without those factors (experiences) had significantly different ideal L2 selves. Second, the experience of living abroad was not a significant differentiating factor for the ideal L2 self. Third, the results of the regression analysis suggested that school, home, and foreign media influences are significant contributors to the formation of the ideal L2 self. These factors may therefore subsume international travel and English cram school experiences.

Discussion: By understanding the factors that contribute to the ideal L2 self, educators and policymakers can strive to establish a more effective environment to improve students’ motivation to learn English.

1 Introduction

With the advent of globalization, English has become the global lingua franca, and many people from non-English-speaking countries choose to learn English as their second language (L2). This trend has also been observed in Japan. Japanese schools and policymakers now place great value on English-language education. The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) in Japan has claimed that English language ability is essential for Japan’s future in a globalizing society, as English is a global language. High school and university entrance exams often require certain levels of achievement in English language assessments, which can influence students’ future career opportunities. Consequently, many parents in Japan make considerable investments in their children’s English education, preparing them from a young age through cram schools (juku): 54.9% of children learn English outside of school by the third grade in Japan (Meiko gijuku research, 2017).

Numerous studies have been conducted in the broad area of L2 learning. L2 learning motivation has been shown to have a strong relationship with motivational behaviors (Harter, 1981; Dornyei and Ottó, 1998; Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2009; Hashemian and Heidari, 2013), which influence L2 acquisition. Thus, research on L2 motivation can be instrumental in promoting more successful L2 acquisition. Some previous studies (e.g., Ryan, 2009; Ocampo, 2017; Kikuchi, 2019) have already examined some aspects of Japanese students’ motivation to learn English.

While there are plenty of studies that have been undertaken on English language learning motivation, a relatively small proportion of those have focused on elementary school students’ motivation to learn English; the bulk of studies have focused on high school and university students’ motivation. As children and adults differ in their cognitive skills and maturity in outlook, undertaking studies on children is essential. There are also differences in learning expectations. For example, with the new curriculum introduced in Japan in 2020, 3rd- and 4th-graders in public elementary schools are now focusing more on listening and speaking to become more familiar with English. Meanwhile, 5th- and 6th-graders are focusing on all of listening, reading, writing, and speaking (including skills necessary for English conversation and presentations). In middle schools, with the shift in the elementary school English curriculum, the curriculum now includes the development of the ability to think and speak for oneself. Middle schools are also shifting to providing all-English classes, in which English classes are taught in English instead of Japanese, which was the traditional practice. Clearly, with different goals for learning English, students’ motivation to learn English would likely differ depending on the stage of their lives. For students preparing for school entrance exams, their motivation to learn English may be more instrumental (external goals or benefits such as future career prospects and improving academic performance, etc.) than intrinsic (internal desire to learn the language such as to satisfy curiosity, pursue an interest, or just for pure enjoyment). However, for younger children, the motivation to learn English may be more intrinsic. Even within these broad age groups, differences in motivation may occur, making it important to not only identify such variations but also understand their sources and possible reasons.

The present study, therefore, aimed to better understand the factors that might influence elementary school students’ motivation to learn English. Gaining a deeper understanding of these factors and their interconnections with language learning motivation can aid in understanding the complexity of student motivation to learn English, which in turn can help in developing effective curricula and environments for English learning. Existing frameworks such as Gardner’s Socio-Educational Model and Dörnyei’s L2 Motivation System provide conceptual tools to understand the intricacies involved in acquiring a second language and the motivation to learn a new language.

2 Literature review

2.1 The socio-educational model

The Socio-Educational Model (Gardner and Lambert, 1959, 1972; Gardner, 1979, 1985, 1988) of language learning has set a strong foundation for language learning motivation research. It focuses on the role of educational and environmental factors in language learning, such as integrative orientation (the learner’s aspiration to integrate into the target language community and culture), instrumental orientation (the learner’s desire to achieve realistic goals), and institutional support (resources and opportunities offered by educational institutions to assist in language learning). However, some researchers have suggested that Gardner’s conception of language learning lacks adequate links to new cognitive motivation concepts such as goal and self-determination theories. Additionally, most of Gardner’s research was based in Canada, a country with English and French as its official languages. Therefore, researchers have claimed that the term integrativeness may not apply to other countries where the English-speaking community is limited (Taguchi et al., 2009; Kim, 2011; Lamb, 2012).

2.2 The motivational system

Researchers, such as Kim (2012), have proposed that Dörnyei’s L2 Motivational System is a better predictor of students’ English proficiency than Gardner’s socio-educational model for predicting students’ motivation. With a reformulation of Gardner’s approach, Dörnyei (2005) proposed the L2 motivational system framework, which focuses on the role of motivation and psychological factors. This framework is built on three main dimensions: the ideal L2 self, the current L2 self, and the L2 learning experience. The ideal L2 self, the focus of the present research, is a major component of the framework’s dimensions and a vision of what the language learner wants to become. When there is a discrepancy between the current and ideal selves, an individual becomes motivated to learn the language to try to narrow or eliminate that gap. In terms of the applicability of the L2 motivational system framework to different age groups, Zentner and Renaud (2007) suggested that the adolescent ideal self is still under development and that it is difficult for adolescents to establish a stable image of their ideal self. Dörnyei and Ushioda (2009) claimed that the L2 motivation system might not apply to secondary school students. While some posit challenges in defining this ideal for adolescents, recent studies question such views. Although there might be challenges in establishing a stable image of their ideal self at this age, some of the recent studies (Kim, 2009; Wong, 2018; Zhu et al., 2023) have suggested that the concept of the ideal L2 self can be particularly influential during adolescence. Kim’s (2009) study had shown a relationship between ideal L2 self and motivated behavior at younger ages (grades 3 to 6) for students learning English in Korea. Furthermore, Zhu et al.’s (2023) research discovered a positive association between the ideal L2 self and motivation among non-Chinese speaking primary school students in Hong Kong. Similarly, Wong’s, 2018 study demonstrated that the ideal L2 self of 5th-grade Chinese as a second language learners in Hong Kong correlated with their reading achievement and motivated learning behaviors. These findings strongly suggest that the concept of an ideal L2 self is closely linked to the motivation even of younger learners such as elementary school students. However, research on the ideal L2 self among Japanese elementary school students is limited. Thus, the present study focused on the ideal L2 self of Japanese elementary school students to better understand whether this factor is likewise important in their language learning motivation.

Previous studies have reported that individual differences such as age, gender, and past experiences significantly affect L2 learning attitudes. For instance, Carreira (2006) found that 3rd graders in Japanese schools had a higher intrinsic motivation to learn English than 6th graders. A similar pattern was also observed in other academic subjects, suggesting an age-related influence on this decrease in motivation. Furthermore, 3rd graders had a higher interest in foreign countries and higher levels of instrumental motivation than 6th graders. Hayashibara (2014) investigated the factors that influence the English learning motivation of 5th- and 6th-grade students in Japan and found that gender and grade are differentiating factors in intrinsic motivation. In terms of past experiences, although living and traveling abroad experiences were not a differentiating factor for intrinsic motivation, they were a differentiating factor for “avoiding uneasiness,” which is when students try to avoid negative feelings, like feeling foolish or embarrassed, because of their low English ability. However, studies on how individual differences affect young adolescents’ ideal L2 self are limited. Hence, this study also attempted to clarify how individual differences and past experiences might influence younger students’ ideal L2 selves.

Previous research has also revealed that external influences (e.g., parents, teachers, peer groups) and instructional materials are related to students’ motivation to learn an L2 (Dörnyei, 1994; Kikuchi, 2009). These studies have indicated that motivation to learn and develop possible L2 selves can be influenced by external factors such as encouragement and the presence of important role models in students’ lives. Ideal L2 selves vary between individuals, but they also appear to be influenced by social constructs. According to Oyserman and Fryberg (2006), possible selves are socially constructed, meaning that they are shaped by influential figures such as parents, role models, and media portrayals that serve as models for the realization of these potential L2 identities. In fact, Oyserman and Fryberg (2006) found differences in possible selves between rural and urban areas due to different exposures to role models for youth in America. While studies have explored the connections between external influences and the motivation to learn an L2, research examining the relationship between these influences and the formation of a possible L2 self, particularly the ideal L2 self, is limited. It is important to understand the relationship between these influences and the ideal L2 self because it can help education stakeholders (e.g., researchers, policymakers, teachers, parents) to determine and establish an effective learning environment for language learners.

2.3 The current study

The present study had three main aims. The first was to better understand the relationship between Japanese elementary students’ English language/foreign exposure and their ideal L2 selves. The authors wanted to determine, for example, whether elementary school students’ English language/foreign exposure was a differentiating factor in their ideal L2 selves. According to Neff and Apple’s (2023) study, both short-term (one month) and long-term (one year) study abroad experiences were effective in enhancing Japanese university students’ sense of their L2 selves. In Hayashibara’s (2014) study, students with living and traveling abroad experiences had higher levels of avoidance of uneasiness, which was one factor that influenced the English learning motivation of Japanese elementary school students. Thus, the authors’ hypothesized that Japanese elementary school students’ experiences of living and traveling abroad, as well as attending cram school, would be differentiating factors of the ideal L2 self, similar to previous studies.

The second aim of this study was to investigate the possible contributing external influences (i.e., home influence, school influence, media influence, and peer influence) on the ideal L2 self. Studies have shown that the ideal L2 self is associated with motivated behavior, which in turn is associated with English proficiency (Dörnyei, 2005). Thus, investing in the optimal development of an ideal L2 self could help establish an effective second language learning environment. Kim and Kim’s (2014) study revealed that an ideal L2 self directly influences the achievement of English proficiency for elementary third graders in South Korea, and for high school students, motivated behavior is the most critical factor affecting English proficiency. This suggests that more research on understanding the ideal L2 self is important to understand younger students’ English learning. Determining what contributes to the ideal L2 self of young adolescents, such as elementary school students, can help toward establishing an effective learning environment. However, the predictors of the ideal L2 self for young adolescents remain unclear. The present study investigated the possible relationships between external influences (home, school, peers, foreign media, etc.) and the ideal L2 self, and hypothesized that some external influences significantly predict the ideal L2 self, as they provide models for possible future selves (Dörnyei, 1994; Oyserman and Fryberg, 2006; Kikuchi, 2009).

The authors are also aware that most if not all factors that can influence the ideal L2 self are related in various ways to each other. For example, home influence and students’ attendance at cram schools or experiences of traveling overseas are likely to be connected. Similarly, teachers’ influence may be related to students’ motivation, which may vary with age and gender. If there were multiple contributing factors to the ideal L2 self, the third aim of this study was to explore the relative contributions of those different factors to students’ ideal L2 selves (i.e., to determine if some may be comparatively more influential). Therefore, in this study, the authors evaluated the factors that might be better at predicting the ideal L2 self by performing a hierarchical linear regression.

The main research questions and associated sub-questions we addressed in this study were as follows:

1. What is the relationship between Japanese elementary students’ English language/foreign exposure and their ideal L2 selves?

• Is English language exposure a differentiating factor in their ideal L2 selves?

2. What are the external influences (home influence, school influence, media influence, and peer influence) on the ideal L2 self of Japanese elementary students?

3. Among the various factors that could influence the ideal L2 self, which factors contribute the most to students’ ideal L2 selves?

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Participants

This study was approved by a faculty-based human participants’ research ethics committee of Kyoto University.

The participants for our study were selected using a combination of stratified and purposive sampling methods. The participants were 4th (9–10 years old) and 6th (11–12 years old) graders from two public elementary schools in Japan. One school is located in Kyoto, and the other is in Chiba. Within each stratum, we utilized a purposive sampling technique to select students who were going to a school which has active foreign language classes. We chose these specific grades as they were at pivotal educational stages where variations in foreign language class durations have been observed. By stratifying based on grade levels and purposively selecting schools involved in these specific language programs, we aimed to analyze the effects of grade level within a well-defined and relevant sample, enhancing the study’s specificity and relevance to similar educational contexts as these schools. Participants included 225 students (102 boys and 123 girls); 227 sets of data were originally collected; however, data from two students were excluded due to crucial missing information.

3.1.1 S elementary school (Kyoto)

In this school, 3rd and 4th grade students receive about 25 h, while 5th and 6th grade students receive about 50 h, of foreign language class activity annually. Students start foreign language activity classes in the 1st grade. They occasionally have an assistant language teacher (a non-Japanese, foreign teacher) to help with foreign language activity class sessions.

3.1.2 T elementary school (Chiba)

In this school, 3rd and 4th grade students receive approximately 35 h, while 5th and 6th grade students receive approximately 70 h, of foreign language class activity annually. As in Elementary School S, they occasionally have assistant language teachers to help with class sessions.

3.2 Measurements

Quantitative data were collected from the students’ using questionnaires. This approach was deemed appropriate for examining the relationships between and the relative influences of different factors.

3.2.1 Student questionnaire

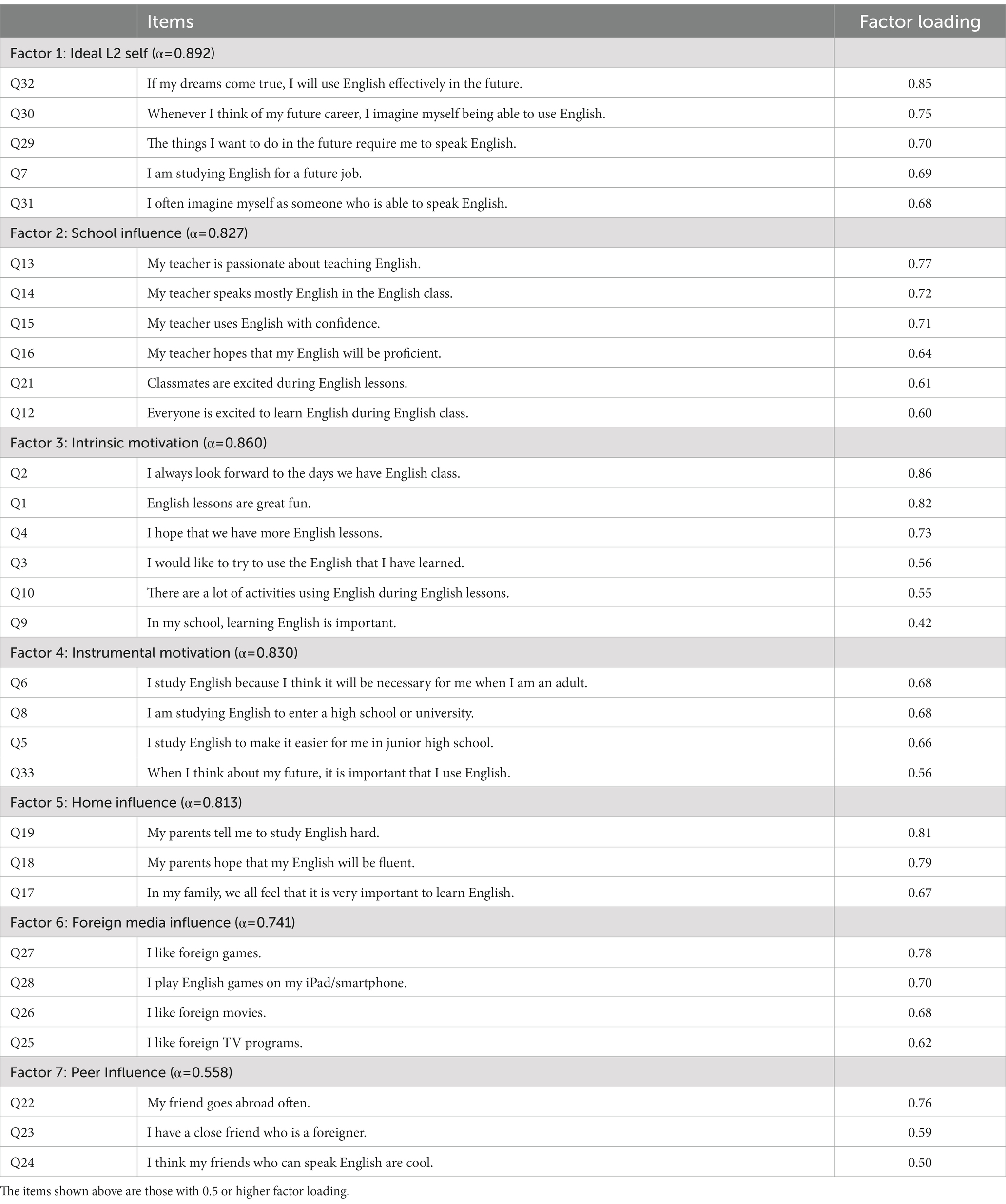

The questionnaire comprised two demographic factor items, four English language/foreign exposure items, and 33 items relating to language learning motivation and external influences, including items on motivation to learn English, school influence, home influence, and foreign media influence. Items related to motivation to learn English and external influences required responses on 5-point Likert-type scales. Exploratory factor analysis identified four underlying external influencing factors: school, home, foreign media, and peers; and three motivational factors: instrumental motivation, intrinsic motivation, and the ideal L2 self (Table 1). The peer influence factor was excluded from subsequent analysis owing to the low reliability of its items.

The demographic factor section of the questionnaire required students to provide information on their age and gender. In the English language/foreign exposure section, the participants answered questions about whether they had traveled abroad, lived abroad, and attended or were currently attending an English cram school outside of their regular school. These questions were added to examine how the students’ past language exposure-related experiences might have related to their ideal L2 self.

In Hayashibara’s (2014) study, student overseas experience, (experience or lack of experience in living and traveling abroad) was measured. In the present study, traveling and living abroad were placed in separate questions to investigate possible differences in their relationship to motivation. English cram school experience was also added as it is another foreign language exposure that students could have.

To measure ideal L2 self, questions relevant to Japanese children were selected from Taguchi et al.’s (2009) ideal L2 self questionnaire. Dörnyei (1990) developed the original ideal L2 self questions, which Taguchi et al. (2009) adapted to the Japanese context. Questions that were irrelevant to Japanese elementary school students (e.g., I can imagine myself writing English e-mails fluently) were excluded in the current study questionnaire. External influence questions were developed based on those used in Hayashibara’s (2014) study and Carreira’s (2006) study. Additional items (e.g., I play English games on my iPad/smartphone) were added to Hayashibara’s (2014) study’s existing questionnaire items to adapt to known English-related activities of the current new generation of children.

Prior to its use, four elementary school teachers reviewed an earlier version of the questionnaire to ensure that it was relevant and understandable to elementary school children and teachers.

3.3 Procedure

In elementary schools S and T, after securing the necessary permissions, homeroom teachers passed the questionnaires to their classroom children. The questionnaire included easy instructions for the children to follow, and included an explanation of their right not to complete the questionnaire and to withdraw at any time from the study if they wished. The teachers also verbally explained this to the students. The questionnaire took approximately 10–15 min to complete.

3.4 Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 29.0. First, factor analysis was performed to confirm the structure of each measured factor. Table 1 lists the items for each factor. Cronbach alpha values were computed to evaluate the reliability of the items that comprised those factors.

A t-test was then performed to investigate differences in the ideal L2 self as a function of demographic variables and previous learning experiences. An independent samples two-tailed t-test was performed to determine whether the English language and foreign exposure were differentiating factors for ideal L2 selves. The analysis tested whether there was a significant difference in the ideal L2 self scores of children with and without current English cram school experience, past English cram school experience, living abroad experience, or traveling abroad experience. An alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine significance in all statistical analyses.

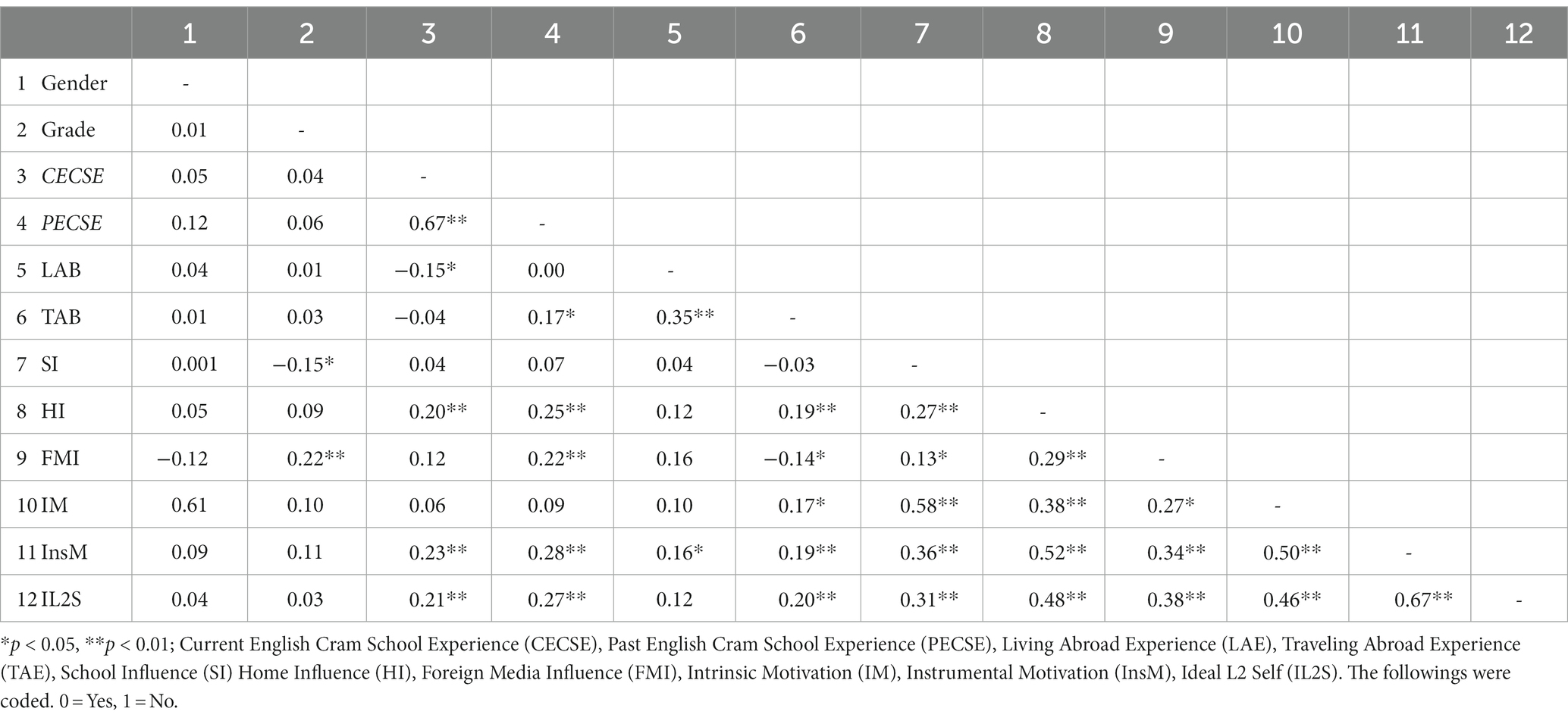

Then, correlation analysis was conducted to explore the associations among the variables, as shown in Table 2. It aimed to determine whether linear relationships, either positive or negative, existed between the ideal L2 self and the various factors considered in the study. The findings from the correlation analysis informed subsequent steps in the study, offering valuable guidance for the hierarchical linear regression analysis that followed.

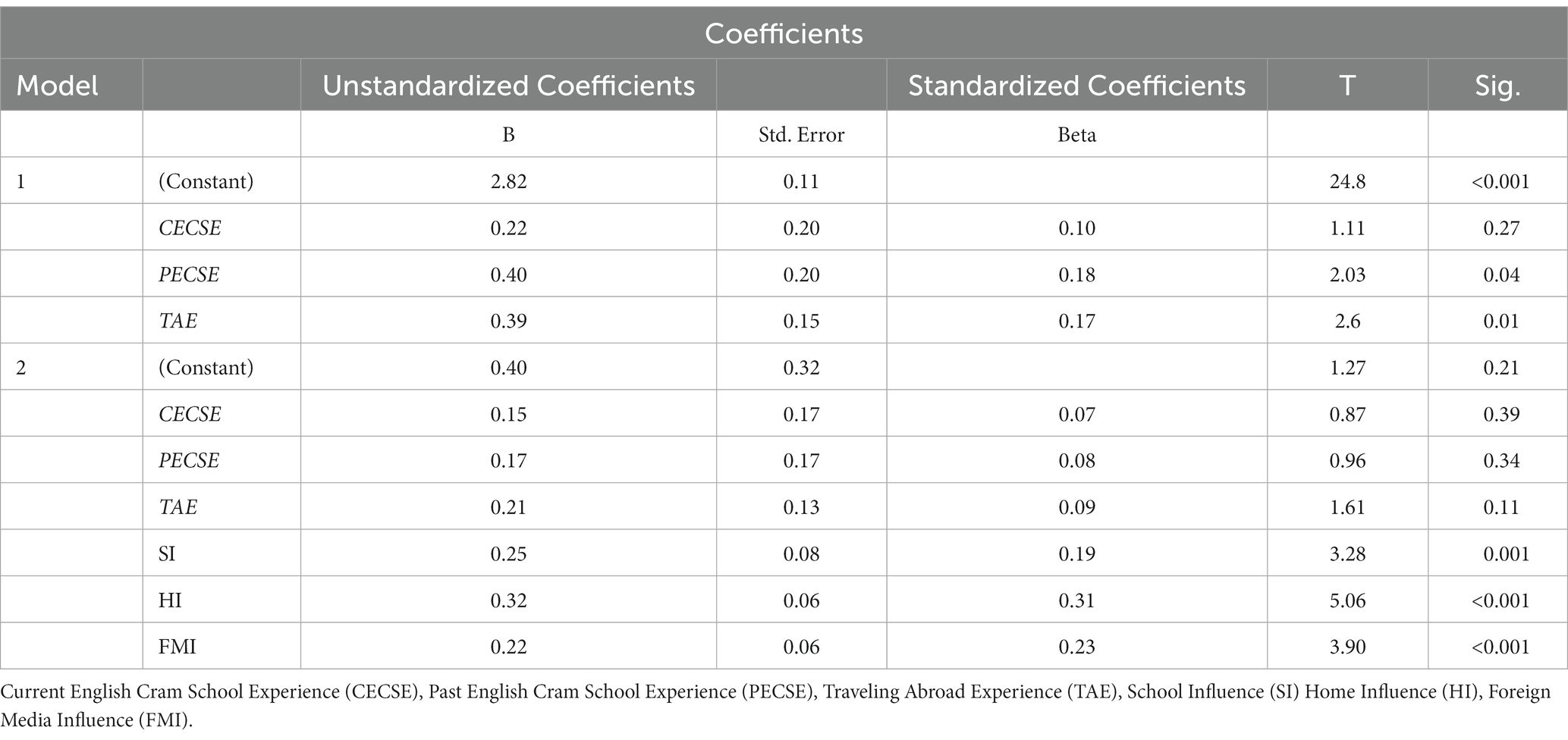

Finally, a hierarchical linear regression analysis was performed to determine which of the significant external influences inside and outside the classroom contributed the most to an ideal L2 self. To assess multicollinearity, variance inflation factors of variables were analyzed. Variance inflation factor values below 5 indicate low levels of multicollinearity. All variables were between 1 and 5, indicating a moderate correlation. Table 3 presents the results of the hierarchical linear regression.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

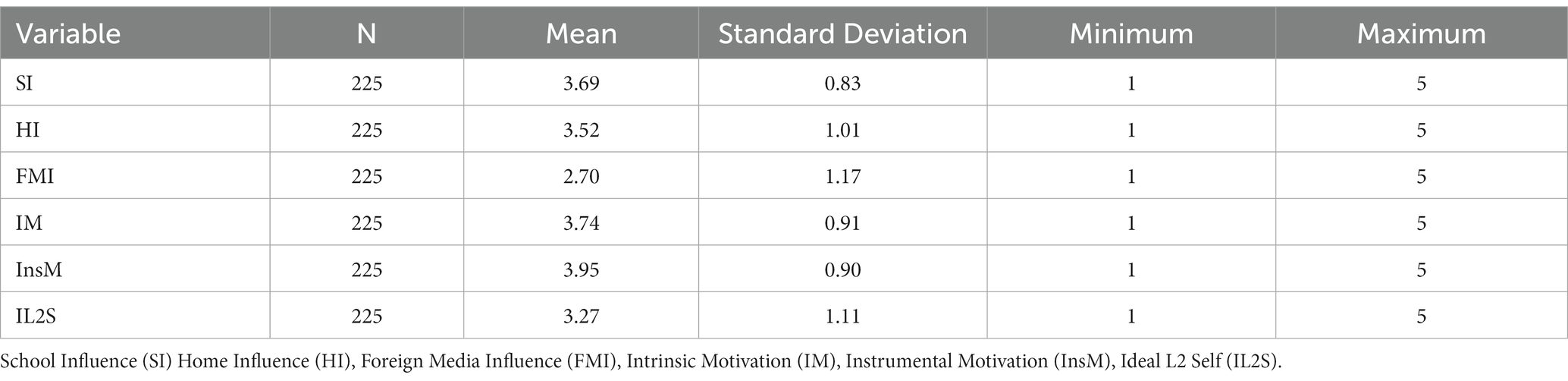

The gender and grade distributions of the sample were fairly even. This means that the proportion of girls (54.67%) and boys (45.33%) were approximately equivalent. Likewise, the proportion of students in grade 4 (49.33%) and in grade 6 (50.67%) can be considered equivalent. Regarding English cram school experiences, a lower percentage of students had current enrollment (40%) compared to those without (60%). In the case of past English cram school attendance, 52.44% of students had prior experience, while 47.56% did not. A significantly lower proportion of students had experiences of living abroad (10.22%) compared to those without such experiences (89.33%). As for traveling abroad, approximately 40.44% of students had this experience, while 59.56% did not. Descriptive statistics on continuous variables are shown in Table 4. Means, standard deviations, medians, and ranges provide the numerical characteristics of the dataset.

4.2 T-test results of English language/foreign exposure on ideal L2 self

The t-test indicated that there was a significant difference in the ideal L2 self between children with (M = 3.56, SD = 1.08) and without (M = 3.09, SD = 1.09) current (at the time of the survey) cram school experience: t(223) = 3.200, p = 0.002 < 0.008. The effect size, as measured by Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988), was 0.435, indicating a medium-size effect.

Similarly, there was a significant difference in ideal L2 motivation for children with (M = 2.96, SD = 1.07) and without (M = 3.56, SD = 1.07) past cram school experience: t(223) = 3.200, p = 0.001 < 0.008. The effect size (Cohen’s d) was 0.568, again indicating a medium-size effect.

There was a significant difference in ideal L2 self between children with (M = 3.54, SD = 1.01) and without (M = 3.09, SD = 1.13) travel abroad experience: t(223) = 3.034, p = 0.003 < 0.008. The effect size was d = 0.412, indicating a medium-size effect.

The independent samples two-tailed t-test results suggested that although current and past English cram school attendance status and traveling abroad experience were significant differentiating factors for students’ ideal L2 selves, gender, grade, and experience living abroad were not.

To reduce the risk of Type I error in the multiple t-tests, Bonferroni correction was applied. In this case, desired overall significance level (p = 0.05) was divided by the number of comparisons (6) which gave the p value of 0.008. This stricter p value was used in determining significant effects, as indicated results reported above.

4.3 Correlations

Table 2 shows Pearson’s correlations between demographic factors, English language/foreign exposure, external influencing factors, L2 learning motivations, and the ideal L2 self scores of the students. All predictor variables were found to statistically correlate with the ideal L2 self, indicating that the data were suitably correlated with the dependent variable for reliable examination through multiple linear regression.

4.4 Hierarchical linear regression

In the first step of the hierarchical linear regression model, the English language and foreign exposure factors were entered to predict the ideal L2 self. In the second step, external influencing factors (school, home, and foreign media influence) were added to the first step as independent variables, and the ideal L2 self was kept as the dependent variable. Preliminary analyses were performed to ensure that assumptions related to normality, linearity, and homogeneity of variances were not violated. Additionally, it was confirmed that no outliers required removal.

Results of the first step (F(3,221) = 8.56, p = 0.001) revealed that although past English cram school experience (β = 0.180, p = 0.044) and travel abroad experience (β = 0.173, p = 0.009) significantly predicted the ideal L2 self, current English school experience (β = 0.097, p = 0.270) did not. In the first step, the three independent variables together explained 10% (adjusted R2 = 9%) of the variance in the ideal L2 self.

The second step (F(6,218) = 19.05, p < 0.001), which additionally included external influencing factors, was also significant, showing an explanation of 34% (adjusted R2 = 33%) of the variance in the ideal L2 self. School (β = 0.187, p = 0.001), home (β = 0.309, p < 0.001), and foreign media (β = 0.227, p < 0.001) influence emerged as significant predictors of the ideal L2 self. After including these external influencing factors, the previously significant predictors from the first step (past English cram school experience, and traveling abroad) were no longer statistically significant in the second step.

5 Discussion

In the current study, the relationships between Japanese elementary students’ English language/foreign exposure and their ideal L2 selves were investigated. In addition, the significance of external influences (home, school, media, and peers) on the ideal L2 self of the students was examined. This study’s results suggest three characteristics of the relationship between elementary school students’ English/foreign language exposure and their ideal L2 selves. First, the results indicate that both current and past English cram school attendance and travel abroad experience are significant differentiating factors for students’ ideal L2 selves. This aligns with findings from Neff and Apple’s (2023) study, which suggested that both short and long study abroad experiences enhance Japanese university students’ ideal L2 selves. The findings here indicate that, similarly, for elementary school students, going to English cram school or traveling internationally is a significant differentiating factor for the development of ideal L2 selves. This study complements Hayashibara’s (2014) findings, which indicated that elementary students with experience living and traveling abroad were significantly better at avoiding uneasiness to those without such experiences. It underscores the importance of English/foreign language exposure within the language learning curricula. Additionally, it brings to light the potential educational disparities that may arise from gaps in educational opportunities available to students.

Second, the experience of living abroad was not a significant differentiating factor for the ideal L2 self. This result is interesting because it differs from those of previous studies. It could be that despite living abroad, there was limited exposure to the English-speaking community or that it had been a while ago, and so, it was not a significant factor in differentiating the students’ ideal L2 self. However, in this study, the duration, countries, or reasons for living abroad were not specified. Therefore, information on understanding the students’ experiences of living abroad is limited. Additionally, the proportion of students who had lived abroad (10.22%) might have been too small for the analysis to detect a significant difference in the comparison of their ideal L2 selves. Furthermore, while these factors correlate with the ideal L2 self, they can also be attributed to parental influence, as suggested by the subsequent regression results.

Third, the results of the multiple linear regression analyses indicated that home, school, and foreign media influence were all significant predictors of the ideal L2 self. Specifically, home influence appears to predict children’s ideal L2 selves. When both English language/foreign exposure variables and external influence variables were considered, the English language/foreign exposure variables (cram school experience and traveling abroad experience) were no longer significant. This aligns with the ideal L2 self-framework (Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2009), suggesting that parents and teachers can influence students’ ideal L2 selves through expectations, encouragement, and guidance, as well as the opportunities for language exposure experiences (e.g., attending cram school, traveling abroad) that they provide for their children/students. Foreign media can have a similar influence. While English cram school and traveling abroad experiences can provide exposure to authentic language use and cultural immersion, parental and teacher influence is more continuous, personalized, and supportive, which makes them powerful factors in shaping an individual’s ideal L2 self. It is also important to note that this external influence depends on the students’ circumstances and the quality of parental and teacher involvement. Building upon prior research (Kim, 2009; Kim and Kim, 2014; Wong, 2018; Zhu et al., 2023), it becomes evident that fostering an ideal L2 self-image is an effective approach to enhance motivation. Furthermore, from the current study, it is clear that the surrounding environment plays a crucial role in shaping this ideal L2 self-image. These results suggest that it is crucial to establish a daily living environment in which students can increase and maintain a positive ideal L2 self-image through their parents, teachers, and media. For example, parents speaking English at home might help students establish their ideal L2 selves by providing an English-speaking role model. In other words, to develop an effective English language curriculum, policymakers and educators need to consider not only learning content and structure but also the crucial role of home and school.

6 Conclusion and directions for future research

The present study identified factors that contribute to the development of the ideal L2 self for elementary school students in Japan. By understanding the factors that contribute to the ideal L2 self, educators and policymakers can establish an effective environment to improve students’ motivation to learn English. Therefore, it can be said that the findings of the present study can benefit policymakers, researchers, and educators in effectively utilizing resources and effort at home and in schools.

The implication of the results of the present study is that researchers must consider the interplay among students’ demographics, English language/foreign exposure, home and school influences, and other influencing factors to understand their ideal L2 selves and learning motivations. Educators must be aware that students come to their classes at different motivational levels to learn English, depending on their demographic backgrounds, English language level, foreign exposure, and external influences. Parents and teachers should also be fully aware that their behaviors and decisions (including opportunities they present) significantly affect their children’s ideal L2 selves. Thus, what they say and do (including modeling) and what beliefs and attitudes they convey through their words and actions will ultimately affect children’s English language achievement (via learning motivation).

In future research, it will be essential to first investigate the specific external influences related to student motivation. For example, it would be useful to investigate the kinds of parental beliefs and behaviors that increase students’ motivation to enhance their ideal L2 selves. By identifying such beliefs and behaviors, educators can help build environments and curricula that consider these factors. It is also important to consider negative factors that can lead to decreased motivation so that the associated beliefs and behaviors can be avoided when dealing with children. Additionally, to better understand the consequences of an increased ideal L2 self toward learning the English language, it would be helpful to consider volition, which is motivated behavior such as effort and persistence (Yashima, 2012).

Second, it would be helpful to consider the external factors related to students’ ideal L2 selves and their motivation for L2 learning. For example, it would be useful to investigate the relationship between students’ social environments and L2 learning attitudes and beliefs. Furthermore, it is important to examine close social relationships with friends, classmates, peers, more senior students, and older and younger siblings.

Third, intervention studies focusing on English language learning materials and teaching strategies should be conducted. The results of the present study suggest that students’ schools, homes, and foreign media influence their ideal L2 selves. Therefore, the intervention should be focused on ways that parents and teachers might be able to more positively impact students’ ideal L2.

The present study only examined the factors affecting elementary school students’ ideal L2 selves. To gain a more complete picture, conducting similar research with older students (i.e., at junior high and high school levels) would be useful, as it would clarify whether predictors of learning motivation change with increasing age and grade levels.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Education Psychological Experimental Research Ethics Review Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because the information about the study was explained in Japanese to the participating teachers and students. The participants were informed that they have the right not to participate in the study and there will be no negative consequences. They were also informed that they can withdraw from the study at any time. Students were recommended to read a book silently if they wished not to participate in the study. Instead of using the consent forms, their decision to do the tasks was considered tacit consent.

Author contributions

AI: Writing – original draft, Data collection and analyses. EM: Writing – review & editing. TS: – Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Japan Science and Technology Agency: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. This work was supported by JST SPRING, Grant Number JPMUSP2110, and JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number 20k01501. Additionally, the scholarship and research fellowship of the "Program for Leading Graduate Schools" by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science were funded by the main author. Financial support was instrumental in covering the various expenses associated with this research project, such as research resources and access to specialized databases and literature.

Acknowledgments

We thank all schools, teachers, and children who participated in this study. The authors would also like to thank Eriko Kawai for her invaluable comments and advice regarding earlier versions of this research report. They would also like to express their deep gratitude to Hiroaki Ayabe, Daisuke Akamatsu, and Enming Zhang for their help with statistical procedures and various aspects of manuscript preparation. Finally, they thank the school members and students who supported this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Carreira, J. M. (2006). Motivation for learning English as a foreign language in Japanese elementary schools. JALT Journal 28:135. doi: 10.37546/jaltjj28.2-2

Dörnyei, Z. (1990). Conceptualizing motivation in foreign-language learning. Lang. Learn. 40, 45–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1990.tb00954.x

Dörnyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and motivating in the foreign language classroom. Mod. Lang. J. 78, 273–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02042.x

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. London, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dornyei, Z., and Ottó, I. (1998). Motivation in action: A process model of L2 motivation. In Working Papers in Applied Linguistics. London: Thames Valley University. 4, 43–69. Available at: https://nottingham-repository.worktribe.com/output/1024190.

Dörnyei, Z., and Ushioda, E. (2009). Motivation, language identity and the L2 self. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Gardner, R. (1979). “Social psychological aspects of second language acquisition” in Language and social psychology. eds. H. Giles and R. St Clair (Oxford: Blackwell), 193–220.

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold Publishers.

Gardner, R. C. (1988). The socio-educational model of second-language learning: assumptions, findings, and issues. Lang. Learn. 38, 101–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1988.tb00403.x

Gardner, R. C., and Lambert, W. E. (1959). Motivational variables in second-language acquisition. Canadian J Psychology/Revue canadienne de psychologie 13, 266–272. doi: 10.1037/h0083787

Gardner, R. C., and Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second-language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers.

Harter, S. (1981). A new self-report scale of intrinsic versus extrinsic orientation in the classroom: motivational and informational components. Dev. Psychol. 17, 300–312. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.17.3.300

Hashemian, M., and Heidari, A. (2013). The relationship between L2 learners’ motivation/attitude and success in L2 writing. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 70, 476–489. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.085

Hayashibara, S. (2014). Factors that influence the English learning motivation of fifth and sixth grade students in Japan. Educational technology research 37, 25–35. doi: 10.15077/etr.KJ00009649883

Kikuchi, K. (2009). Listening to our learners' voices: what demotivates Japanese high school students? Lang. Teach. Res. 13, 453–471. doi: 10.1177/1362168809341520

Kikuchi, K. (2019). Motivation and demotivation over two years: a case study of English language learners in Japan. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 9, 157–175. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2019.9.1.7

Kim, T. Y. (2009). Korean elementary school Students' perceptual learning style, ideal L2 Selt and motivated behavior. English Language and Linguistics. 9, 459–486.

Kim, T. Y. (2011). Korean elementary school students’ English learning Memotivation: a comparative survey study. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 12, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12564-010-9113-1

Kim, T. Y. (2012). The L2 motivational self system of Korean EFL students: Cross-grade survey analysis. English Teaching. 67, 29–56. doi: 10.15858/engtea.67.1.201203.29

Kim, T., and Kim, Y. (2014). 6 EFL Students’ L2 Motivational Self System and Self- Regulation: Focusing on Elementary and Junior High School Students in Korea. In The Impact of Self-Concept on Language Learning. (Ed.) K. Csizér and M. Magid (Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters), 87–107. doi: 10.21832/9781783092383-007

Lamb, M. (2012). A self system perspective on young adolescents’ motivation to learn English in urban and rural settings. Lang. Learn. 62, 997–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2012.00719.x

Meiko gijuku research (2017) Kodomono eigo gakushu ni kansuru zenkoku chosa [National Survey on Children's English learning]. Available at: http://special.meikogijuku.jp/image/170710_meiko_english.pdf.

Neff, P., and Apple, M. (2023). Short-term and long-term study abroad: the impact on language learners’ intercultural communication, L2 confidence, and sense of L2 self. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev.. 44, 572–588. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2020.1847125

Ocampo, M. B. (2017). Japanese students’ mindset and motivation in studying English grammar and reading. People: Intern J social sciences 3, 1192–1208. doi: 10.20319/pijss.2017.32.11921208

Oyserman, D., and Fryberg, S. (2006). “The possible selves of diverse adolescents: content and function across gender, race and national origin” in Possible selves: Theory, research and applications. eds. C. Dunkel and J. Kerpelman (New York: Nova Science Publishers), 17–40.

Ryan, S. (2009). Self and identity in L2 motivation in Japan: the ideal L2 self and Japanese learners of English. Motivation, language identity and the L2 self 120:143. doi: 10.21832/9781847691293-007

Taguchi, T., Magid, M., and Papi, M. (2009). The L2 motivational self system among Japanese, Chinese and Iranian learners of English: a comparative study. Motivation, language identity and the L2 self 36, 66–97. doi: 10.21832/9781847691293-005

Wong, Y. K. (2018). Structural relationships between second-language future self-image and the reading achievement of young Chinese language learners in Hong Kong. System 72, 201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2017.12.003

Yashima, T. (2012). “Willingness to communicate: momentary volition that results in L2 behaviour” in Psychology for language learning. eds. S. Mercer, S. Ryan, and M. Williams (Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan).

Zentner, M., and Renaud, O. (2007). Origins of adolescents' ideal self: an intergenerational perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 92, 557–574. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.557

Zhu, X., Chan, S. D., and Yao, Y. (2023). The associations of parental support with first-grade primary school L2 Chinese learners’ ideal selves, motivation, engagement, and reading test performance in Hong Kong: a person-centered approach. Early Educ. Dev. 34, 1647–1664. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2022.2139544

Keywords: ideal L2 self, L2 learning, English education, motivation, Japanese elementary school students

Citation: Ishida A, Manalo E and Sekiyama T (2024) Students’ motivation to learn English: the importance of external influence on the ideal L2 self. Front. Educ. 8:1264624. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1264624

Edited by:

Zhengdong Gan, University of Macau, ChinaReviewed by:

Hui Helen Li, Wuhan University of Technology, ChinaYuan Yao, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, China

Copyright © 2024 Ishida, Manalo and Sekiyama. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ayame Ishida, aXNoaWRhLmF5YW1lLjU4ckBzdC5reW90by11LmFjLmpw

Ayame Ishida

Ayame Ishida Emmanuel Manalo

Emmanuel Manalo Takashi Sekiyama

Takashi Sekiyama