- 1Faculty of Health/Dean of Studies, Chair of Didactics and Educational Research in Health Care, University of Witten/Herdecke, Witten, Germany

- 2Faculty of Health, Chair of Didactics and Educational Research in Health Care, University of Witten/Herdecke, Witten, Germany

To enable interprofessional collaboration in practice, it is important to practice interprofessional action during education. Teachers in interprofessional education (IPE) in Germany are insufficiently prepared for joint teaching and often lack pedagogical-didactical training. Teachers who have been who have been used to working uniprofessionally up to now are expected to be able to teach competently across professions. This overlooks the fact that the admission requirements for teaching at the various institutions such as technical colleges, universities of applied sciences and universities are different. In addition, interprofessional teaching is characterized by a special feature: it should be carried out in team teaching. This poses the challenge for the teachers not only to prepare for the teaching in terms of content, but also to get involved with another teaching person. This study asks what interprofessional faculty need to feel well prepared to teach together and focuses on three professions: human medicine, nursing, and physiotherapy. For this purpose, 15 experts were interviewed, five from each of the three professions. The interview material was analyzed according to the structuring qualitative content analysis by Kuckartz, where categories were created to answer the research question. As a result, the analysis showed that three levels are important for the interviewees: the personal prerequisites that contribute to the success of IPE as well as good preparation on a structural and content-related level. Based on this, a concept for further education for interprofessional teachers will be developed.

1. Introduction, theoretical background and research question

The basis for teaching at universities is the Framework Act for Higher Education. It is explicitly stated that German university lecturers perform their tasks in science, art, research, teaching and further education independently (Hochschulrahmengesetz, 2019). No information is given on the qualifications that a university lecturer should possess. Moreover, teachers at universities often find themselves in a dual role. They are not only teaching, but also pursuing a research interest. Reconciling these roles presents them with challenges, as teaching and research function according to different logics. If a central point of interprofessional teaching is togetherness and the logic of research is a competitive one, the question may be raised how a well-functioning togetherness in teaching can be realized.

1.1. Introduction

Patient care is not possible without cooperation between the different professions in the health care system. In order to improve care and ensure good cooperation between professions, learners from different professions should be brought together in education (Wissenschaftsrat, 2012). The focus of research is mostly on the learners, with the role of the teacher less well studied (Reeves et al., 2016). However, they are the ones who are responsible for teaching, planning and implementing. For inter-professional education (IPE) in Germany, learners from different education can come together - from technical colleges, universities of applied sciences and universities (Cichon and Klapper, 2018). The entry requirements for teachers to be allowed to teach are very different in the institutions. The basis for teaching at universities is the Framework Act for Higher Education (2019). It is explicitly stated that university lecturers perform their tasks in science, art, research, teaching and further education independently (Hochschulrahmengesetz, 2019). No information is given on the qualifications that a university lecturer should possess. At universities, further training in didactics and pedagogy is only partially required (Strauss et al., 2020).

Thus, the scope for deciding which persons with which existing or non-existing qualifications are employed in teaching is relatively large. For technical colleges and universities of applied sciences, there are no uniform federal specifications, which is why there are considerable differences. In most cases, however, not only professional competences in the sense of the professional title are required for teaching, but also pedagogical competences (MPhG - Masseur- und Physiotherapeutengesetz, 1994; PflBG - Pflegeberufegesetz, 2017; Zusatzqualifikation von mind - Deutscher Verband für Physiotherapie, 2018). What exactly is meant by this varies from region to region. It should be noted that pedagogical competencies are at least considered in technical colleges and universities of applied sciences, but are not mentioned in the university setting according to the Higher Education Framework Act (2019).

1.2. Theoretical background

In the university setting, the assumption of teaching for lecturers usually comes suddenly. In the university setting, it is assumed that lecturers can teach even if they have previously worked exclusively in the practical setting, for example. They are often inexperienced and are not prepared for the new challenges. From the management level it is assumed that teaching teaching occurs naturally (Böss-Ostendorf et al., 2014). Individual, non-mandatory programs show that quality improvement in teaching through professionalization offers are advertised and accepted by teachers (Babbe et al., 2020). However, knowing about teaching competence or acquiring it are two different aspects. Moreover, the development from novice to teaching professional is not automatic. Winteler and Batscherer (2004) outline five phases of development that are occur in the best case: The first phase is characterized by ‘survival’, the teacher is preoccupied with him/herself and his/her own role. In the second phase, the teacher is still uncertain, but recognizes that the learners are interested in the lesson content. In the third phase, the teacher focuses more on the content rather than the learners. If the teachers perceive and reflect on their fixations on the lesson content, they can enter the fourth phase. If this self-fixation cannot be abandoned, they remain in the third phase. In the fourth phase, the teacher focuses on the learners and the learning process and is able to adjust the content and teaching style accordingly. In the fifth phase, the teacher adapts the variety of methods and the use of media to the learners, as he or she recognizes that they are more likely to retain what they have worked out for themselves. These developmental stages show that teaching is fraught with challenges. If pedagogical and/or didactic competencies are lacking, it does not become easier for the teacher to navigate the classroom.

In uniprofessional teaching, one teacher is responsible, so there is no need to cooperate with other teachers. However, this ability to cooperate is an important element in interprofessional education (Crow and Smith, 2003). It is about thinking as a team, planning and implementing lessons together. Through collaborative competence, teachers can engage in reflective dialogue with colleagues and plan, deliver, and evaluate teaching together (Feldmann, 2005). Team teaching is more than the existence of another teacher. The goal should be to become communicative and cooperative team players and to turn away from individualism and lone wolf existence (Rohr et al., 2016). To be able to collaborate across professions, it is necessary to work together at eye level and to overcome silo thinking (Sottas et al., 2013). Cooperation at eye level can be made more difficult if teachers also pursue a research interest in addition to their teaching activities. Research interests are competitive and joint teaching places its emphasis on good cooperation. Combining this could be a big challenge for IPE teachers (Viebahn, 2009). If a central point of interprofessional teaching is togetherness and the logic of research is a competitive one, the question may be raised how a well-functioning togetherness in teaching can be realized.

1.3. Research question

Reeves et al. (2016) note that the research interest is more on learners and less on teachers. However, since teachers train and accompany learners on their way, they have a special task. The different institutional requirements for teachers make equal cooperation in teaching difficult. Therefore, an adapted preparation for interprofessional teaching is needed. According to Hattie, in order for good teaching to work, certain requirements must be fulfilled, which were compiled by Steffens and Höfer (2016):

• Concrete action on the part of the teacher

• Knowledge about instructional planning, forms of instruction, learning strategies and forms of learning

• Knowledge of feedback strategies

• Dealing with feedback

Thus, adapted preparation for interprofessional teaching is needed. Our quantitative preliminary study (Schlicker and Ehlers, 2023) shows that of the 76 online respondents, 14 have an additional pedagogical qualification and seven have an interprofessional one. This indicates that there is currently no preparation that fits exactly. There are currently no special interprofessional training courses for teachers throughout Germany. Some institutions offer in-house training for their interprofessional staff, which is not accessible to outsiders. The content that is covered is not communicated to the outside world, so that it remains unclear which topics are being dealt with.

Since uniprofessional teaching formats differ from interprofessional ones, our research question is:

• What do interprofessional educators in Germany need to feel well prepared to teach together?

This research project focuses on the three professions of human medicine, nursing and physiotherapy, as they have a large overlap in the provision of care.

2. Materials and methods

A mixed methods approach was chosen. Mixed-methods design makes it possible to better understand a complex issue. The quantitative perspective of counting is combined with the qualitative perspective of understanding meaning with the aim of exploring research problems more comprehensively (Kuckartz, 2014). In a preliminary study (Schlicker and Ehlers, 2023) quantitative data were generated. The qualitative inquiry conducted here was designed to fill explanatory gaps in more depth. The answers of the quantitative questionnaire provided first indications of what is important for the teachers in interprofessional teaching (Schlicker and Ehlers, 2023). More detailed answers should be obtained from the interviews. Therefore, expert interviews were conducted.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee of Witten/Herdecke University decided that no “ethical or legal concerns were apparent and that the study could therefore be carried out (No214/2018). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

2.1. Qualitative study design

2.1.1. Questionnaire

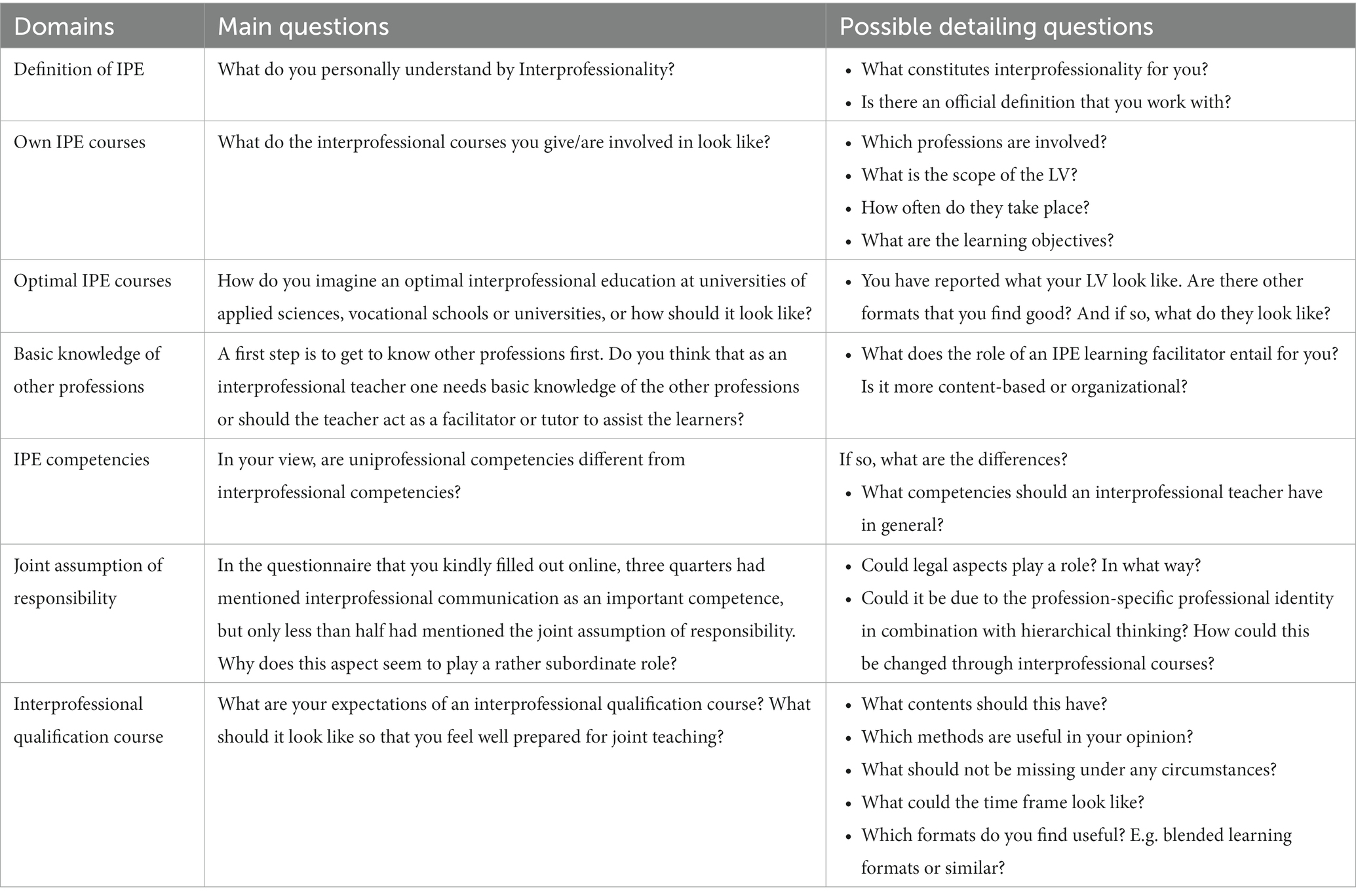

The quantitative study (Schlicker and Ehlers, 2023) formed the basis for the development of the guideline questionnaire. To elaborate on selected topics for the guideline-based expert interviews, the guideline contained seven areas: Definition of IPE, own IPE courses, optimal IPE courses, basic knowledge of other professions, IPE competencies, joint assumption of responsibility, and interprofessional qualification course. Each area contained main and detailed questions (Table 1).

2.1.2. Sample

We invited interviewees based on their returned questionnaires. The online survey determined whether respondents were available for an interview. If they were, they were asked to provide their email address. In the selection, the greatest possible heterogeneity we aimed for with regard to gender, age, qualification for teaching as well as duration and scope of interprofessional teaching. A total of fifteen interviewees were selected, three physiotherapists, three physicians and three nurses. If theoretical saturation was not achieved after the fifteen interviews, additional individuals would be solicited based on the aforementioned criteria. The interview partners received a detailed information letter about the research request when contacted and an informed consent form when the appointment was confirmed. All interview partners participated voluntarily and agreed to anonymous publication of their data.

2.1.3. The interviews

The interviews were conducted from late January 2020 to mid-February 2021. We carried out the first eight interview in person at each facilities, and the last seven via the cloud-based Zoom videoconferencing service due to Corona restrictions. Eleven women and four men between the ages of 31 and 60 with 3.5 to 32 years of work experience were interviewed. The interviews ranged in length from 20 min to 70 min. The length of the interviews was not dependent on the profession. All recorded interviews were transcribed, anonymized, and analyzed using MAXQDA computer-assisted qualitative data and text analysis software (Analytics Pro 2022).

2.1.4. Analysis of the data

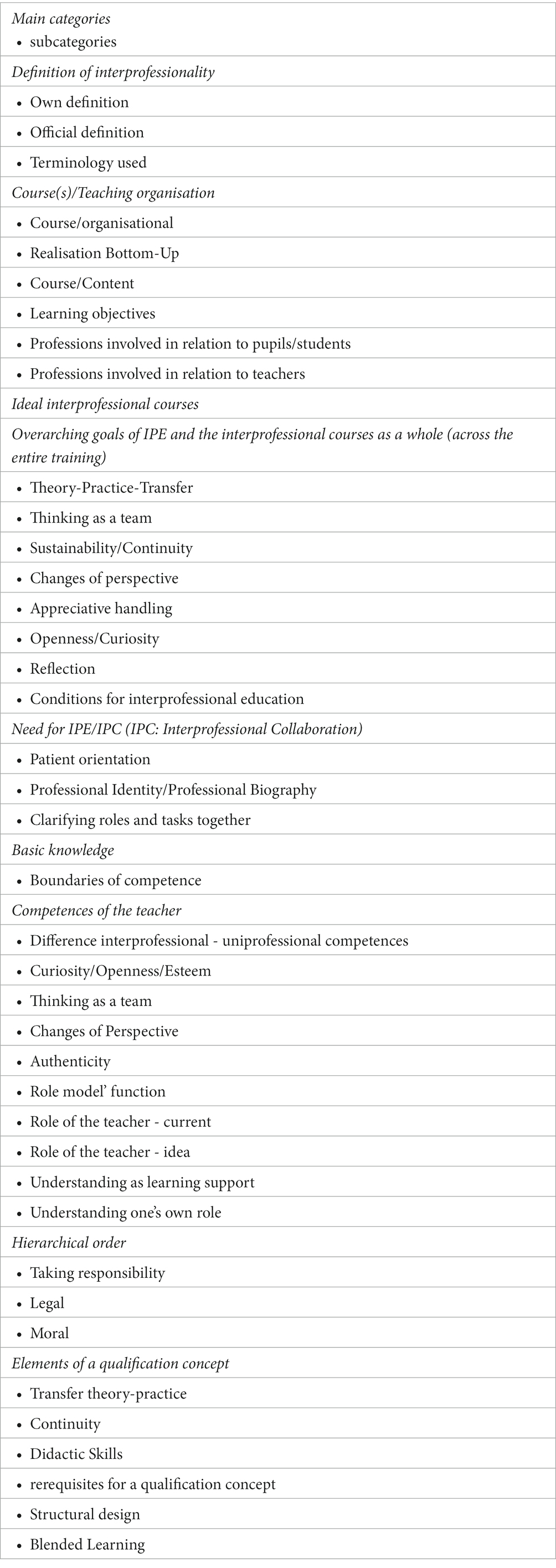

JE and AS separately read the transcribed interviews. The data were analyzed according to the structuring qualitative content analysis of Kuckartz (2018). In a first step, the text material was open-coded and divided into main and subcategories, which took place in close exchange. In parallel, category formation via summaries was developed with the aim of comparing the codings with each other in order to be able to close gaps in the coding, if necessary. The main categories were developed deductively and inductively. Deductively, the interview guide served as orientation to introduce main categories. Inductively, these were supplemented by the open text work in the main categories and subcategories.

Categories and codings were discussed and decided together. The category manual in Table 2 lists the individual categories and subcategories.

3. Results

The categories can be grouped into three themes in the results: personal prerequisites, which are considered important for interprofessional teaching, structural design and organization of a qualification course, and content-related topics.

3.1. Personal prerequisites which are considered important for interprofessional teaching

Openness in cooperation is important to the interviewees: To be open in order to recognize the expertise of other professions, to look at the fields of activity of other professions and thus to get to know them. This applies to the practical setting as well as to teaching.

"And this participation, this being allowed to experience the other training, i.e. observing colleagues teaching, I would still personally feel as an increase and would probably still help me to understand the other profession better." [Interviewee No. 9, Physiotherapist]

For many of the interview partners, openness in the practical setting is expressed in the fact that they would like to accompany other professions in their work. They want to get to know the field of activity by looking over the shoulders of other professions in their everyday work, asking questions, discussing cases with them and, if possible, reflecting on them afterwards.

"I would actually look at their practical field of activity and have it explained to me. I would actually look at their everyday life. What do they do, how do they do it. I would talk to them." [Interviewee No.8, Physiotherapist]

Other personal prerequisites mentioned are an empathetic approach, a willingness to engage with other professions, and a high degree of self-awareness through self-experience in order to be able to reflect on one’s own patterns of thought and action. If a discussion of the various topics only takes place on a theoretical level, the practical reference in dealing with people from other professions is missing.

"But I think a certain degree of self-awareness, because otherwise self-enlightenment is almost impossible, I think that is extremely important, because I think otherwise you run directly, without wanting to, into all these traps that you also encounter in everyday life, in everyday work." [Interviewee No.1, Physician]

3.2. Design of a qualification course – on the structural level

A very important point mentioned for the design of interprofessional teaching is time. Each profession makes its own initial thoughts, which are then compiled. Thus, a first structure is created, which is adapted again and again in further steps. If the planners of the different professions see themselves as equals, appointments must be found that allow everyone to participate in the planning. This is a complex process due to different framework conditions. In addition to the planning of IPE events, the implementation of the teaching as well as a subsequent reflection is equally time-consuming.

"But the most important thing is really time. Development takes time, implementation takes time. […]. And the time should also allow us to keep asking what can be done differently. That this is not so firmly encrusted, but that we have a flexibility in it, that's what I think is the most important thing in the meantime." [Interviewee No. 12, Nurse]

Furthermore, the time is mentioned, which can be spent for the participation in a qualification course. This depends on many factors, such as course duration, work substitution, travel times and childcare. The tasks in the individual areas of activity are varied and complex, so that it is difficult for some to take or be able to take the time for further qualification.

"Well, I find that a very difficult question, because, I mean, nobody has time."

[Interviewee No. 6, Nurse]

On the one hand, the respondents find it difficult to take the time for a qualification course. On the other hand, repetition and continuity are important to them for implementation in practical everyday life and in terms of sustainability. These two poles reveal a certain discrepancy. A certain degree of continuity is desired for the implementation of a qualification course. Through the repetitions and the recurring confrontation with different topics, the probability is higher to be able to implement ideas into the daily work. IPE means to initiate changes in the facilities. Change takes time and practice. In order to be able to practice, topics must be regularly reflected upon and thought and action patterns must be adapted accordingly.

"So, I always think repetition is good. I think a one-time thing like that is the case with every continuing education program, because you always have so many ideas, but they always fizzle out again very quickly or are difficult to implement, and then you lose the thread a bit. That's why I think repetition is very good." [Interviewee No. 6, Nurse]

As a result of the Corona pandemic, many stakeholders have become accustomed to using online tools, which is seen as an opportunity in interprofessional work, but rather in the area of knowledge acquisition. The desire is expressed to make materials available online in order to be able to familiarize oneself thematically. An exchange in small groups is also seen as useful to get to know each other on a personal as well as professional level and to discuss and analyze cases.

"So, especially when it comes to the exchange, to opinions, (…) so, when it comes to subjective sensitivities and views must be exchanged, then it is indispensable that you come together and then I think it is also imperative that you sit across from each other. What happens between people cannot be solved in any way electronically, it is too divisive and there is simply a lack of closeness to each other." [Interviewee No. 9, Physiotherapist]

The interviewees would like to see a theory-practice transfer. They want to get to know the field of activity of other professions, but also their practical field of work. This can be achieved through job shadowing, for example. The time for this should be provided by the qualification course and considered in the planning.

3.3. Structure of a qualification course – at the content level

On the content level, good theory-practice transfer can be achieved through observation if the respective field of activity is experienced and explained in its many facets in a practical manner. The knowledge gained increases when the different professions exchange views on the cases during observation, bring in their own perspectives and discuss them.

"If I want to understand the other person, I have to go to his island and not the other way around" [Interviewee No. 8, Physiotherapist].

Further wishes include a teaching of didactic skills. These relate to teaching methods for the classroom - Which methods are particularly useful in interprofessional teaching? - but also preparation on a human level - How do I give appreciative feedback? How do I accept appreciative feedback? How do I really engage with others? These questions also reflect the desire to be prepared on a personal level. What does it take for me to be able to deal with other people in a way that is as free of hierarchy as possible, as free of prejudice as possible, and as sensitive to discrimination as possible? The interviewees mention terms such as openness, appreciation and reflection. However, these must be filled with content.

"Just because you mean well and want to do interprofessional cooperation or teaching, it doesn't mean that you don't secretly run after your prejudices and transport them and that's why I think self-education is a real basis for something like this" [Interviewee No. 1, Physician].

One’s own attitude towards interprofessional work is relevant for cooperation. Questions about the voluntary nature of teaching, the choice of topics, the view of other professions, teamwork and conflict management should be answered by each person individually, because for interprofessional work to be fruitful, “everyone must be behind it.

"[…] everyone must be behind it. And if not everyone is behind it, and as free of hierarchy as possible, then quality management goes wrong, so interprofessional work with each other also goes wrong. Or it becomes very difficult, let's say so" [B8, Physiotherapist].

Interprofessional teaching means working together, relying on each other and designing teaching together.

"That we not only complement each other and make each other a little bit easier, but that we have this more, the sum is more than the whole of its parts, ne. So these energy gains that we have through that as well." [Interviewee No. 12, Nurse].

4. Discussion

4.1. What personal prerequisites are needed for interprofessional teaching?

The interviewees mentioned openness on different levels as an important concept for them in the cooperation with other professions. Cooperation is characterized by the internalization of stereotypes, which in turn have an influence on attitudes and behavior (Petersen and Six, 2008). Since the term stereotype tends to have a negative meaning in everyday life, disdainful behaviors are assumed as a consequence. Since stereotypical patterns are mostly automated, the consequences on the level of one’s own thought and action patterns are unconscious (Schmid Mast and Krings, 2008). Attitudes and perceptions are already developed at an early stage of training through profession-specific socialization and form the basis for later interaction (Sottas et al., 2016). This can be counteracted by the job shadowing mentioned by the interviewees (Monahan et al., 2018). In the practical setting, previously negative assumptions about other professions can be revised by accompanying them in their everyday work. Experiencing what tasks other professions have, what expertise they possess, what their everyday work looks like in all its facets, can change the empathy and the view of these professions. It is possible to form one’s own picture and to enter into a targeted exchange with the actors. In most cases, job shadowing is arranged on an individual basis, and there are few opportunities in the health care system to get to know other professions in this way. The Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin (2023) offers a “Hospitationswoche im klinischen Qualitäts- und Risikomanagement” (Hospitalization week in clinical quality and risk management). Since this week is not remunerated and an application is required, it is questionable how many people have the possibilities and resources to accept this offer. Teaching observations also help the respondents to better understand other professions.

There are fears of contact between the teachers due to their different educational backgrounds. The idea of being observed by other teachers in their own lessons is described as unusual (Arens, 2017). In addition, the norm in teaching is to give lessons alone, which is why teachers are not used to working in a team (Feldmann, 2005). By observing other teachers in the teaching context, insights can be gained and implemented in one’s own teaching (Burgsteiner, 2014). A joint reflection afterwards can be beneficial for observers and teachers, as difficulties and questions can be discussed from different perspectives. It is essential that the observer expresses criticism constructively and that the teacher accepts it as well (Zankel-Pichler, 2014). Since interprofessionality thrives on cooperation, teaching should also be done in a team (Sottas et al., 2013). Through the preparation and implementation of joint teaching, the various professions get to know each other on a variety of levels - from the content of the training courses to practical activities and teaching skills. By working together as a team, individuals are relieved, lone wolves are reduced and silo thinking can be overcome (Arbeitsstab Forum Bildung, 2001; Sottas et al., 2013). Professional practice is characterized by an ambivalence between what the actors say and what they show. The joint cooperation is seen as quite important, which indicates a positive basic attitude of the persons. In practical everyday life, however, this attitude is less visible. Kerres et al. (2022) outline this using the example of interprofessional rounds. A ward round in which several professions are involved does not necessarily mean that interprofessional exchange takes place and ideas, suggestions, feedback and impulses are accepted respectfully.

4.2. What kind of structure does an IPE qualification course need?

Time is an essential factor for the interviewees in order to be able to adequately plan, carry out and reflect on joint teaching. In this context, it is not enough to talk about IPE. In order to be able to develop an understanding of the perspective of other professions, guidance for critical reflection is needed (Charles et al., 2010). To what extent the participants have time for this process of planning, implementation and critical reflection remains an open question. Interprofessional education in Germany is currently still carried out in few institutions (Schlicker and Ehlers, 2023) and teachers are rarely given additional time for this type of teaching. The reasons for this are manifold. Above all, the lack of support from the institution in terms of resources such as money, staff and rooms is mentioned. Co-teaching is often covered by dedicated staff. The problem does not only relate to time resources.

It is also difficult for interprofessional teachers to access interprofessional teaching-learning materials. Although the Robert Bosch Foundation with the program ‘Operation Team’ (Sottas, 2020) as well as the national model curriculum (IMPP, n.d.) are strongly committed to interprofessional education, there is relatively little material available for the planning of interprofessional courses (Kerres et al., 2022). Without the possibility of accessing existing material, time is again needed in addition to the methodological-didactic skills for planning.

Studies on how many interprofessional lecturers carry out joint teaching within the framework of their actual field of activity could not be found at present. If joint teaching, which is still the exception in Germany but common in international comparison (Crow and Smith, 2003; Cimino et al., 2022 Piper-Vallillo et al., 2023), is already performed as an additional task, the question can be asked what priority interprofessional continuing education has. The calendar of events of the Medical Association of Schleswig-Holstein (Aeksh De, n.d.) shows that the topic of “interprofessional training” is listed, but no training courses are currently offered. In many professions, continuing education credits must be earned in order to ensure medical quality. It is questionable what priority is given to training in interprofessional collaboration and to what extent it is offered. There is no central register for continuing education in which continuing education points can be acquired for the professions from the health care sector. And if, using the example of the medical profession, 250 continuing education points have to be acquired within five years and part of these must be subject-specific (Ärztefortbildungen.de, n.d.), it is questionable how much capacity the individual persons want to invest in interprofessional topics.

4.3. What content structure does an IPE qualification course need?

Since interprofessional teachers in Germany, in contrast to international comparisons (Paradis and Whitehead, 2019). Hardly have access to adequate teaching and learning material, they would like to see didactic skills taught in the context of a qualification course. This is aggravated by the fact that teachers at different institutions have considerable differences in their teaching skills (see introduction), which can lead to difficulties in cooperation. We can only speculate here about the reasons why things are done differently in Germany than internationally. IPE has only become an important topic here in recent years, so there is certainly still some catching up to do. Also the didactic training of lecturers in medicine has a much shorter tradition than in other countries. Positively, this opens up some possibilities to learn from other countries and to convey these learnings in newly designed courses.

Taking the two professions of human medicine and physiotherapy as an example, the practice in Germany is that physiotherapists provide therapy according to the doctor’s instructions. In the educational situation, teachers in physiotherapy colleges are expected to have “relevant professional qualifications and pedagogical aptitude” (MPhG - Masseur- und Physiotherapeutengesetz, 1994; Zusatzqualifikation von mind - Deutscher Verband für Physiotherapie, 2018), which is not the case for teachers in the university context. It has to be considered how the actors in the cooperation deal with the reversed roles. If the physiotherapy teacher has a higher pedagogical-didactic qualification for teaching, can the teacher from medicine, who may not have these qualifications, get involved? This is where the personal prerequisites mentioned by participants for a qualification course intertwine with what they want from a course in terms of content. Preparation on the human level seems to be an important aspect. Appreciative interaction is mentioned, as is reflection on one’s own attitudes. This joint preparation seems all the more important in view of the fact that, for example, the professional expertise of nurses is often not recognized by physicians (Dienhart et al., 2022). In the context of a qualification course, the aim should be for people to learn to relate to each other as human beings, to respect others in their field of activity, and to be able to give and accept feedback constructively. Thus, a course should not only cover the professional level of interprofessional cooperation, but rather bring the actors who work together in the practical setting for the patients together on a human level. To this end, it is essential to reflect on one’s own thought and action patterns vis-à-vis other professions and to critically question one’s own sensitivities, so that the WHO goal formulated as early as 1988 “Learn together to work together for health” (World Health Organization, 1988; p. 1) can already be achieved at the training level.

5. Limitations of the study

In this study, the three professions of human medicine, nursing and physiotherapy were included. This does not mean that other professions are unimportant in interprofessional education and care.

Not all respondents provided their contact details in the online survey, so that only some of them could be requested for an interview. From this response, an attempt was made to generate as heterogeneous a group as possible.

The first eight interviews were conducted in person. By visiting the interview partners on site, a relaxed atmosphere could be created in advance through small talk, and in some cases this was combined with a presentation of the institution. As the last seven interviews took place via the digital provider ZOOM, there was no need to get to know each other in advance, as the interview partners only took the previously agreed time for the interview.

6. Conclusion and outlook

Even after intensive research, no cross-professional and openly accessible qualification concept for interprofessional teachers could be found in the German-speaking area (Germany, Austria and Switzerland). Internationally, these already exist (Steinert, 2005 Williams and Gregory, 2012). Due to the different framework conditions in Germany, a transfer is often challenging. Nevertheless, the opportunity to learn from other countries should be used to develop qualification concepts in German-speaking countries and offer them across professions. According to informal information, in-house training courses could be identified in individual facilities, but these were only available to their own staff. In addition, there was no way to access interprofessional teaching-learning materials through public channels. In 2020, the Robert Bosch Stiftung published a “Handbuch für Lernbegleiter auf interprofessionellen Ausbildungsstationen” (Handbook for learning facilitators on interprofessional training stations; Sottas, 2020), which also addresses the topics of role understanding, methodological competence, and strategies for the implementation of learning objectives. However, since this manual is not based on any accompanying joint training, it is questionable to what extent good cooperation can be achieved in practice if one’s own attitudes in dealing with other professions are not questioned. In addition, only the cooperation at interprofessional training stations is focused on, but not the teaching in the preceding training sections. This study focuses on interprofessional teachers already in the early training context. The focus is not exclusively on the development of pedagogical-didactic skills, but above all on the confrontation with one’s own thought and action patterns. Through an intensive own as well as common reflection a real basis can be created to work on eye level with each other. If these preconditions are met - the existence of pedagogical-didactic skills and the confrontation with one’s own thought and action patterns - the probability is higher to be able to engage in a good cooperation and to come closer to the formulated goal of the World Health Organization (1988, p. 1) “Learning to work together for health.

In the context of this study, only the three professions of human medicine, physiotherapy and nursing were included. It would make sense to include other professions involved in the health care system.

This study addresses the needs of interprofessional faculty. The aim was to find out what they need in order to feel well prepared for joint teaching. It became clear that, in addition to professional content, collaboration on a personal level is most desired.

On the basis of these findings, the next step will be to work out complexes of topics that will serve as a starting point for creating a concept for a qualification course in terms of content and content.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

AS: Writing – original draft. JN: Writing – original draft. JE: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study is financially funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and supported by the Federal Institute for Vocational Training (BIBB), grant number 21INVI0301.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all respondents who participated in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aeksh De . (n.d.). Ärztekammer Schleswig-Holstein. Available at: https://www.aeksh.de/seminare?tag=interprofessionelle+fortbildung&group=aerzte (Accessed June 16, 2023).

Arbeitsstab Forum Bildung . (2001). Pedocs open access Erziehungswissenschaften. Neue Lern-und Lehrkultur: vorläufige Empfehlungen und Expertenbericht. Available at: https://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2008/237/pdf/band10.pdf (Accessed 16 June, 2023).

Babbe, C., Schneider, M., and Hille, K. (2020). “Fit für die Lehre. Und nun? Eine Befragung der Teaching Professionals Programmabsolvent/innen” in Lehre und Lernen entwickeln – Eine Frage der Gestaltung von Übergängen, (Potsdamer Beiträge zur Hochschulforschung). eds. S. Goertz, B. Klages, D. Last, and S. P. Strickroth. 6th edn.(Potsdam: Universitätsverlag Potsdam).

Böss-Ostendorf, A., Senft, H., and Mousli, L. (2014). Einführung in die Hochschul-Lehre : Stuttgart: utb GmbH.

Burgsteiner, H. (2014). “Bedeutung der Hospitationen im Rahmen der Hochschuldidaktischen Weiterbildung für die Reflexion der eigenen Lehrkompetenz” in Hochschuldidaktische Weiterbildung an Fachhochschulen. Lernweltforschung. eds. R. Egger, D. Kiendl-Wendner, and M. Pöllinger, vol. 12 (Wiesbaden: Springer VS).

Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin . Hospitationswoche im Herbst (2023). Available at: https://qualitaetsmanagement.charite.de/ueber_die_stabsstelle/hospitation/; (Accessed June 14, 2023).

Charles, G., Bainbridge, L., and Gilbert, J. (2010). The University of British Columbia model of interprofessional education. J. Interprof. Care 24, 9–18. doi: 10.3109/13561820903294549

Cichon, I., and Klapper, B. (2018). Interprofessionelle Ausbildungsansätze in der Medizin. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 61, 195–200. doi: 10.1007/s00103-017-2672-0

Cimino, F. M., Varpio, L., Konopasky, A. W., Barker, A., Stalmeijer, R. E., and Ma, T. L. (2022). Can we realize our collaborative potential? A critical review of faculty roles and experiences in Interprofessional education. Acad. Med. 97, 87–95. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004909

Crow, J., and Smith, L. (2003). Using co-teaching as a means of facilitating interprofessional collaboration in health and social care. J. Interprof. Care 17, 45–55. doi: 10.1080/1356182021000044139

Dienhart, M., Leschensky, S., and Dunkel, S. (2022). “Wenn überhaupt, dann habe ich zweimal im Monat Kontakt zu einem Arzt. Darstellung der Ergebnisse für die Zielgruppe der Physiotherapeutinnen,” in Interprofessionelles Lernen im Gesundheitswesen. eds. A. Kerres, C. Wissing, and K. Lüftl. (1. Aufl). Stuttgart: Kolhammer.

Feldmann, K. (2005). Erziehungswissenschaft im Aufbruch: eine Einführung; Lehrbuch. Wiesbaden: Springer-Verlag.

Hochschulrahmengesetz . Bundesministerium für Justiz. (2019). Available at: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/hrg/BJNR001850976.html (Accessed June 28, 2023).

IMPP . (n.d.). Projektverlauf Nationales Mustercurriculum interprofessionelle Zusammenarbeit und Kommunikation". Available at: https://www.impp.de/forschung/drittmittelprojekte/interprofessionelle-zusammenarbeit-und-kommunikation/projektverlauf.html (Accessed June 16, 2023).

Kerres, A., Wissing, C., and Lüftl, K. (2022). Interprofessionelles Lernen im Gesundheitswesen: Unterricht entwickeln und gestalten. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Mixed methods Methodologie, Forschungsdesigns und Analyseverfahren, Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Kuckartz, U. (2018). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, praxis, Computerunterstützung. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Monahan, L., Sparbel, K., Heinschel, J., Rugen, K. W., and Rosenberger, K. (2018). Medical and pharmacy students shadowing advanced practice nurses to develop interprofessional competencies. Appl. Nurs. Res. 39, 103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.11.012

MPhG - Masseur- und Physiotherapeutengesetz . (1994). Bundesministerium für Justiz. Available at: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/mphg/BJNR108400994.html (Accessed June 23, 2022).

Paradis, E., and Whitehead, C. R. (2019). “Verschiedene Formen von Wissen: Evidenz in interprofessioneller Praxis und Bildungsarbeit kritisch hinterfragen” in Interprofessionelles Lernen, Lehren und Arbeiten. eds. M. Ewers, E. Paradis, and D. Herinek (Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Basel), 270–284.

Petersen, L.-E., and Six, B. (2008). “Stereotype, in Stereotype, Vorurteile und soziale Diskriminierung” in Theorien, Befunde und Interventionen. eds. L.-E. Petersen and B. Six (Weinheim: Beltz), 21–22.

PflBG - Pflegeberufegesetz . (2017). Bundesministerium für Justiz. Available at: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/pflbg/BJNR258110017.html; (Accessed June 23, 2022).

Piper-Vallillo, E., Zambrotta, M. E., Shields, H. M., Pelletier, S. R., and Ramani, S. (2023). Nurse–doctor co‐teaching: A path towards interprofessional collaboration. The Clinical Teacher. 20: e13556.

Reeves, S., Pelone, F., Hendry, J., Lock, N., Marshall, J., Pillay, L., et al. (2016). Using a meta-ethnographic approach to explore the nature of facilitation and teaching approaches employed in interprofessional education. Med. Teach. 38, 1221–1228. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1210114

Rohr, D., Ouden, H. D., and Rottlaender, E. (2016). Hochschuldidaktik im Fokus von Peer Learning und Beratung. Weinheim: Beltz.

Schlicker, A., and Ehlers, J. (2023). Die Rolle von Dozierenden in der interprofessionellen Ausbildung in Deutschland – eine Befragung von Lehrverantwortlichen in Deutschland. Int. J. Health Prof. 10, 37–45. doi: 10.2478/ijhp-2023-0005

Schmid Mast, M., and Krings, F. (2008). “Stereotype und Inforationsverarbeitung, in Stereotype, Vorurteile und soziale Diskriminierung” in Theorien, Befunde und Interventionen. eds. L.-E. Petersen and B. Six (Weinheim: Beltz), 33–44.

Sottas, B. (2020). Handbuch für interprofessionelle Ausbildungsstationen. Stuttgart, Robert Bosch Stiftung. Available at: https://www.bosch-stiftung.de/sites/default/files/documents/2020-09/200901_Handbuch%20für%20Lernbegleiter%20auf%20interprofessionellen%20Ausbildungsstationen.pdf; (Accessed June 16, 2023).

Sottas, B., Brügger, S., and Meyer, P. C. (2013). Health Universities-Konzept, Relevanz und Best Practice: Mit regionaler Versorgung und interprofessioneller Bildung zu bedarfsgerechten Gesundheitsfachleuten. ZHAW Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften. Available at: www.zhaw.ch/de/zhaw/hochschul-online-publikationen.html; (Accessed August 23, 2022).

Sottas, B., Kissmann, S., and Brügger, S. (2016) Interprofessionelle Ausbildung (IPE). Erfolgsfaktoren–Messinstrument–Best Practice Beispiele. Bern. sottas formative works. Available at: https://formative-works.ch/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2016_3_IPE-Erfolgsfaktoren-Messinstrument-Best-Practice-Beispiele-QR.pdf; (Accessed June 16, 2023).

Steffens, U., and Höfer, D. (2016). Lernen nach Hattie. Wie gelingt guter Unterricht? Weinheim: Beltz Verlag.

Steinert, Y. (2005). Learning together to teach together: Interprofessional education and faculty development. J. Interprof. Care 19, 60–75. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081778

Strauss, M., Ehlers, J. P., Gerss, J., Klotz, L., Reinecke, H., and Leischik, R. (2020). Status quo - the requirements for medical habilitation in Germany. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift (1946) 145, e130–e136.

Viebahn, P. (2009). Lehrende in der Hochschule: Das problematische Verhältnis zwischen Berufsfeld und Lehrkompetenzentwicklung. Beiträge zur Lehrerbildung 27, 37–49.

Williams, J., and Gregory, B. (2012). Open education resources for interprofessional working. Br. J. Midwifery. 20, 436–439.

Winteler, A., and Bartscherer, H. (2004). Professionell lehren und lernen. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Wissenschaftsrat . (2012). Empfehlung zu hochschulischen Qualifikationen für das Gesundheitswesen. Available at: https://www.wissenschaftsrat.de/download/archiv/2411-12.html; (Accessed June 16, 2023).

World Health Organization . (1988). Learning together to work together for health: report of a WHO study group on multiprofessional education of health personnel: the team approach. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/37411/WHO_TRS_769.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed June 16, 2023).

Zankel-Pichler, U. (2014). “Lehren lernen–Ein Erfahrungsbericht in Hochschuldidaktische Weiterbildung an Fachhochschulen” in Durchführung-Ergebnisse-Perspektiven. eds. R. Egger and D. Kiendl-Wendner (Wiesbaden: Springer-Verlag), 205–211.

Zusatzqualifikation von mind - Deutscher Verband für Physiotherapie (2018). Bundesländerregelung zur Qualifikation von Lehrkräften in der Physiotherapieausbildung. Available at: https://www.physio-deutschland.de/fileadmin/data/bund/Dateien_oeffentlich/Beruf_und_Bildung/Fort-_und_Weiterbildung/Bundesländerregelungen_zur_Qualifikation_von_Lehrkräften_in_der_Physiotherapie_.pdf (Accessed June 28, 2023).

Keywords: interprofessional education, interprofessional qualification concept, interprofessional teachers, focus on three professions: human medicine, nursing, physiotherapy, teamwork

Citation: Schlicker A, Nitsche J and Ehlers J (2023) Special challenge interprofessional education – how should lecturers be trained? Front. Educ. 8:1260820. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1260820

Edited by:

Jill Thistlethwaite, University of Technology Sydney, AustraliaReviewed by:

Patricia Bluteau, Coventry University, United KingdomWarren Kidd, University of East London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2023 Schlicker, Nitsche and Ehlers. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea Schlicker, YW5kcmVhLnNjaGxpY2tlckB1bmktd2guZGU=

Andrea Schlicker

Andrea Schlicker Julia Nitsche

Julia Nitsche Jan Ehlers

Jan Ehlers