- 1Department of Recreation Management and Policy, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, United States

- 2Education Department, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, United States

- 3College of Health and Human Services, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, United States

- 4Department of Education, Democracy & Social Change, Plymouth State University, Plymouth, NH, United States

- 5NH Community Development Finance Authority, Concord, NH, United States

This study examined the normative messages that inform youth postsecondary decision making in a predominantly rural state in the northeastern U.S., focusing on the institutionalization and circulation of identity master narratives. Using a multi-level, ecological approach to sampling, the study interviewed 33 key informants in positions of influence in educational, workforce, and quality of life domains. Narrative analysis yielded evidence of a predominant master narrative – College for All – that participants described as a prescriptive expectation that youth and families orient their postsecondary planning toward four-year, residential baccalaureate degree programs. Both general and domain-specific aspects of this master narrative are elaborated, as well as findings indicating that the College for All ideology appears to both obscure and stigmatize the development and institutionalization of alternative postsecondary pathways. Implications for rural communities, rural mobility, and future research on narratives informing postsecondary options for youth are discussed.

1 Introduction

The secondary to postsecondary transition is a significant decision point for youth and is receiving considerable policy and media attention as college costs rise, workforce needs increase, and equity concerns persist. Because the “college-choice process” remains “one of the first major noncompulsory decisions made by American adolescents” (Kinzie et al., 2004), it provides a valuable window into the way culture and identity are mutually interconnected in ways that are consequential both individually and societally.

Individually, earning a college degree has substantial financial repercussions over the life course (Carnevale et al., 2021) as well as signaling claims to what Côté (1996) called “identity capital,” or the tangible and intangible attributes that mark one’s ability to “aspire” and “achieve” (Huerta et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021). Given these benefits, the high degree of personal, familial, and institutional investment in the four-year baccalaureate degree as a normative ideal is understandable. However, in rural areas, the emphasis on college attendance also has been criticized as a “talent extraction mechanism” that depletes human capital and promotes a sense of uprootedness (Roberts and Grant, 2021; Tran and DeFeo, 2021), making postsecondary planning complicated for individuals and perilous for communities due to the “mobility imperative” college-going typically introduces (Farrugia, 2016). These factors create different normative pressures on youth future planning that are important to understand.

The present study examined how postsecondary pathways in a predominantly rural New England state are organized according to culturally normative ideas about what is possible and desirable for youth to do after high school. The research was motivated by demographic changes in the northeastern U.S. state of New Hampshire over the 40-year period between 1970 and 2009 which shifted to an outmigration pattern after a period of relative stability among the 15–19 and 20–24 age cohorts. Beginning in 2008, policymakers attempted to address the consequences of outmigration by launching strategies aimed at recruiting young adults to the state, but the prospect of retaining youth was given comparatively little attention. Absent concerted policies, programs, or even robust public dialogue about retaining youth versus recruiting young adults over the next decade, we wanted to know what explanations people occupying different institutional vantage points provided on the causes of youth outmigration and what solutions and barriers they envisioned. Since as developmental researchers we were chiefly interested in the cultural factors that shape processes of identity formation (Seaman et al., 2017; Syed and McLean, 2023), we adopted the lens of master narratives, which identity theorists define as “culturally shared stories that guide thoughts, beliefs, values, and behaviors” (Syed and McLean, 2023). Moreover, because master narratives contain normative prescriptions about “how to be a ‘good’ member of a culture” (McLean and Syed, 2015), they structure possibilities for identity formation involving “integration of the past and present self with the future self” (Johnson et al., 2014). Master narratives therefore have important implications for future planning. Our aim was to contribute to understanding how culturally circulating messages about what youth can and should do, operationalized here as master narratives, may be shaping adolescent future planning particularly in rural areas that have undergone significant demographic, educational, and economic transformations over the late 20th century (Hamilton et al., 2008; Sherman, 2009).

2 Literature review

2.1 Master narratives: linking individual and cultural identity processes

Research on adolescent identity has traditionally emphasized individual agency as the main engine of identity formation (McLean et al., 2017), including at the secondary/postsecondary transition (e.g., White et al., 2021). Narrative identity researchers view identity as constituted by a life story that starts to coalesce in adolescence and connects past, present, and future in a cohesive plotline about who one is and might become (McAdams and McLean, 2013). While narrative identity researchers have long acknowledged that life story forms vary culturally (Fivush et al., 2011), individual biographies have historically dominated as the typical unit of analysis (Bamberg, 2011). Issues of marginalization, discrimination, and other systemic conditions that both support and confound biographical self-construction have been comparatively deemphasized as core processes in identity research, prompting calls to “reorient our understanding of identity as a societal variable” (Rogers, 2018).

The master narrative framework seeks to understand the fundamental relations among individual and cultural processes across different timescales and levels of social ecology (Hammack and Toolis, 2015). It locates psychological processes in the “social and cultural space where knowledge, understanding and relationships are constructed. Identity is not something supposedly private, that one possesses, but something that is made by using a particular cultural resource” (Esteban-Guitart, 2012). Because master narratives are “repertoires of behaviour and identity … shared artefacts, of historical origin and their content is social, political and cultural” (Esteban-Guitart, 2012), they are not “stored” exclusively in episodic memories or personal biographies; they are also “embedded in families, communities, institutions, social classes, and the power structures of society” (McAdams, 2022). For example, Dvorakova (2022) illustrated how contrasting Native American ideals of assimilation and self-determination are enshrined in public policies and serve as a basis for both legal entitlements and personal identification. Bergen (2010) argued that normative expectations about proper domestic arragements are violated when spouses live apart for periods of time, requiring “commuter wives” to provide extended justifications when queried about their marriages. In this case, Bergen maintains, the master narrative of marriage is as much a physical and spatial configuration as it is a property of individual persons.

As “templates for the kinds of experiences one should be having, and how one should interpret them” (McLean et al., 2020), master narratives have a compulsory or prescriptive quality. This can generate identity conflicts when individuals’ aspirations, lived experiences, or community values are misaligned with culturally normative models (Syed and McLean, 2022). In such cases, individuals may construct alternative or counter-narratives that can be personally coherent but tend to receive less institutional and community support, which can exacerbate marginalization and pose mental health challenges. For instance, Kerrick and Henry (2017) found that new mothers whose feelings toward their infants grew positive over time but were inconsistent with dominant cultural expectations for immediate affiliation experienced shame, insecurity, and diminished wellbeing.

Researchers have also investigated how master narratives function across historical and developmental time, focusing on what Erikson (1968/1994) called the “coordinates for the range of a period’s identity formations” (p. 32). Smith and Dougherty (2012) found that a master narrative of retirement – a psychologically complex experience with important identity implications – helped individuals to focus on some features of the experience while ignoring others as they crafted their own career biography. The authors found highly consistent narratives across ages, suggesting that the “guiding cultural story about retirement” has been broadly institutionalized to such a degree that it “is deeply enmeshed in the master narrative of the American Dream” (pp. 460–461). Discussing a series of related studies on gender socialization, McLean et al. (2020) presented evidence of stability in traditional gender expectations with deviation in certain cases. Although such border cases may indicate changes in young adults’ situational experiences of gender, unless they index enduring biographical forms “the trajectory of identity development is amorphous, and the traditional narrative may maintain its hold” (p. 124). Likewise, Hammack (2006) found centuries-old narratives of Israeli-Palestinian conflict resistant to intervention at a biographical timescale. Such studies demonstrate the value of seeking evidence of master narratives in a range of social locations to understand how identity functions at a cultural and institutional level to construct normative possibilities for individuals.

2.2 The rise of a College for All ideology

Historians and sociologists of higher education view the institution’s social function as inseparable from the cultural ideologies of a given historical period. One influential work in this tradition is Martin Trow’s phase-and-form framework that describes a post-WWII progression from elite to mass to universal higher education (Trow, 1973). Alongside elite institutions, designed to shape the character of a ruling class, mass institutions arose to sort and train technical and managerial elites. Universal institutions, including community colleges, emerged to support the “adaptation of [the] ‘whole population’ to rapid social and technological change” (Trow, 2007). Attitudes toward access expanded accordingly: in the case of elite institutions, access is viewed as “a privilege of birth or talent or both”; with mass institutions, it is “a right for those with certain qualifications”; and with universal institutions, it is “an obligation for the middle and upper classes” (Trow, 2007). The institutional shifts Trow outlines illustrate how college-going expectations became broadly normalized in the 1970s and how a rising “College for All” ideology and corresponding policy response both emerged from the history of college-going and continued to drive its expansion.

The College for All paradigm simultaneously developed into an educational policy ideology (Rosenbaum, 2011), a cultural discourse (Glass and Nygreen, 2011), and, we argue here, a life-course master narrative that is consequential for processes of youth identity formation. It can be read as the cultural victor of a hard-fought policy battle that dominated the late 20th century between “school-to-work” advocates seeking to expand and diversify career and technical education pathways (see, e.g., Symonds et al., 2011), and those promoting four-year baccalaureate degrees as universally desirable. The College for All approach advanced under Bush-era policies like No Child Left Behind as an ostensible effort to move beyond the discriminatory effects of school-based tracking and its associated “soft bigotry of low expectations” (C-SPAN, 2000). In contrast to the school-to-work position, college became viewed as a more just, equitable, and economically prosperous alternative to vocational education. Although the weakening of rigid tracking structures was a positive outgrowth of this era, these debates nonetheless reveal a history of contestation about the wisdom and desirability of college-going as a universal ideal (Anderson and Nieves, 2020).

Full discussion of these two policy positions is beyond the scope of this review, however the binary way college and work pathways have evolved suggests an undercurrent of zero-sum normative thinking: Anyone who does not participate in higher education in a normatively expectable way is aberrant – defaulting on their obligation to participate adequately in social and technological change or lacking the ambition to realize their economic and moral potential (Kromydas, 2017). Such characterizations are often inferred of youth who direct their own aspirations toward goals not involving a baccalaureate degree or who otherwise complete college at lower rates or in different fashions (Perez-Brena et al., 2019; Missaghian, 2021). College for All is therefore not merely a social policy ideology, it is a normative identity prescription.

2.3 How College-for-All poses risks in rural contexts

The strong emphasis on college as a culturally normative ideal in U.S. educational policy and practice has undoubtedly expanded access for members of underrepresented groups including from rural communities. However, it has also contributed to the phenomenon sociologists have dubbed “rural brain drain” (Carr and Kefalas, 2010), especially in rural “education deserts” where access to postsecondary education is limited (Hillman, 2016). The uncritical maintenance of college-going as an educational and developmental ideal may be overshadowing other gainful workforce opportunities (Thouin et al., 2023). For example, approximately 50% of current jobs in the US are defined as “middle skilled,” the majority of which are considered well-paying, stable, and do not require a 4-year degree as traditionally pursued (Anderson and Nieves, 2020). Labor forecasts show that many of the fastest growing professions are in jobs such as green energy installation and service technicians, hospitality managers, technology and advanced manufacturing positions, and home healthcare aids (United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022).

Even if four-year baccalaureate degrees provided an equal guarantee of economic security, rural youth, families, and communities may not be served by their universal promotion over other alternatives. Rural students perform comparably to suburban peers on math and reading assessments and complete high school at similar rates (Jordan et al., 2012; Aud et al., 2013). In fact, between 1992 and 2004, standardized test scores among rural students increased while they decreased for students from urban and suburban areas (Wells et al., 2019). Despite these attributes, rural youth have lower rates of postsecondary planning, enrollment, persistence, and attainment relative to non-rural youth, revealing a discrepancy that scholars have yet to fully explain (Byun et al., 2015; Koricich et al., 2018). Although some research shows associations between “high parental expectations” and increased educational aspirations and outcomes among rural youth (e.g., Agger et al., 2018) rural scholars maintain that there are implicit risks to rural youth, families, and communities when ideological frameworks are adopted that conflate “aspirations” with attendance in a four-year residential degree program. “One core problem is that implicitly defining educational success in terms of a mobile population of youth exported to urban areas, rural schools may tacitly promote the erosion of their own human capital” (Corbett, 2005). Importantly, the kinds of commitments educationalists deem “aspirational” are inseparable from dominant cultural narratives and models of success that determine the ends to which youth ought to aspire (McLean and Syed, 2015). The study reported here describes some of the properties, dimensions, and causal attributes of one such narrative: College for All.

3 The present study

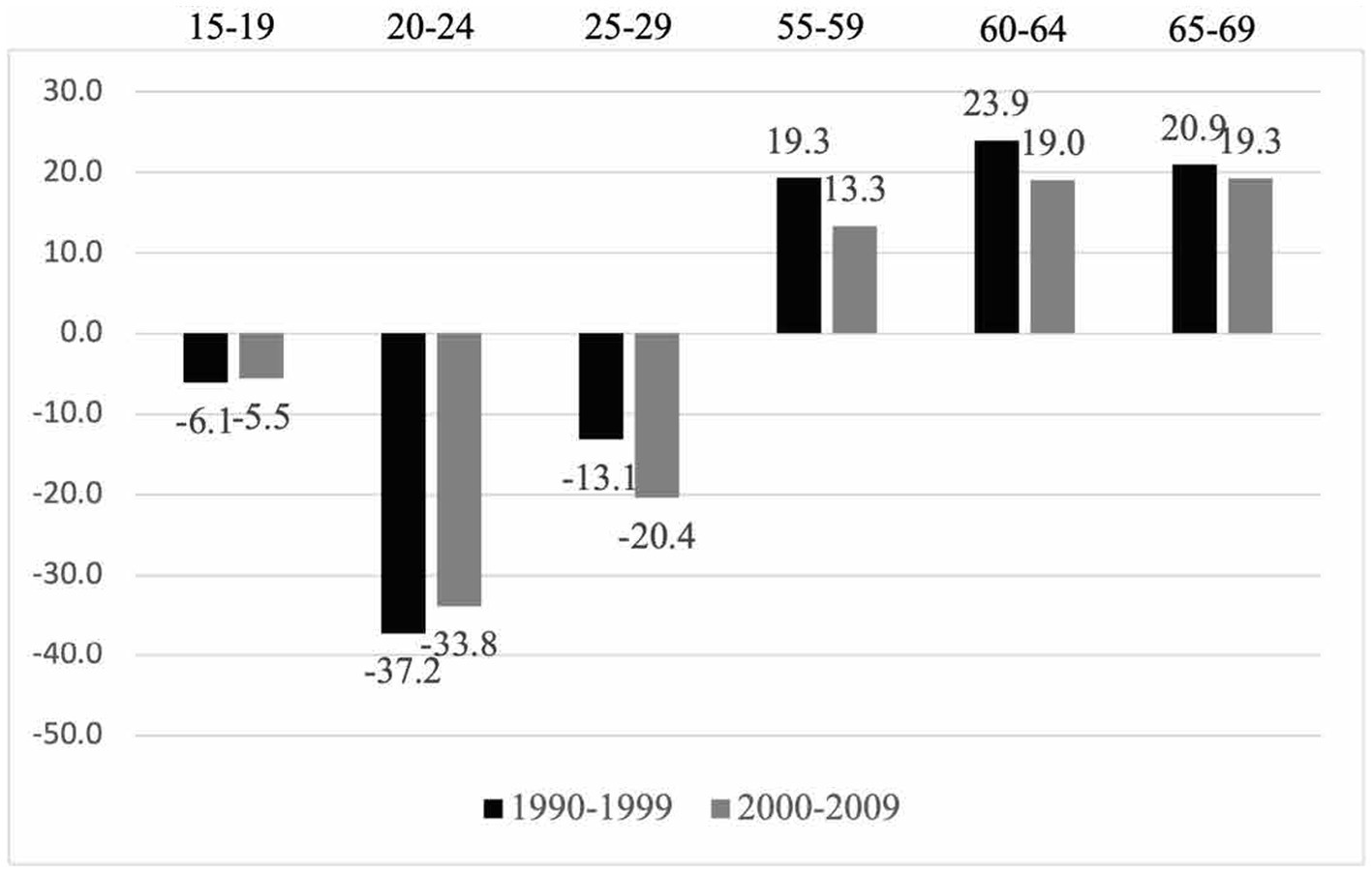

The present study was conducted between September 2020 and March 2021 in New Hampshire (NH), a predominantly rural state in the northeastern U.S. that typifies rural conditions around the country in many ways but also has some unique demographic properties. Between 1970 and 2009, the northeastern U.S. experienced massive economic and demographic shifts that profoundly shaped its character as an environment for youth future planning. Although the total populations among northern New England states increased over this period, they all shifted to a pattern defined by youth outmigration, inmigration of older adults, and declining birth rates, making NH one of the three oldest states in the United States by median age (United States Census Bureau, 2021). Census data reveal pronounced outmigration among the 20–24 age cohort in NH starting around 1990, with the exception of counties housing large colleges and universities (Egan-Robertson et al., 2023). This shift particularly affected the states’ ruralmost counties, which experienced the highest levels of youth outmigration despite aggregate population figures stabilizing because of an influx of older adults seeking to “age in place” or retire near natural amenities (Johnson and Lichter, 2019). See Figure 1 (data from Egan-Robertson et al., 2023). NH also remains one of the least “sticky” states in both the U.S. and the northeast region, with only 41% of its current residents having been born in the state (Johnson, 2023), a factor that compromises economic development and community vitality (Pranger et al., 2023).

Figure 1. Net migration of age cohorts in NH ruralmost counties by decade, 1990–2009. Average net migration in Coös, Carroll, and Sullivan counties designated ruralmost using UDSA urban/rural continuum codes.

In addition to overall migration trends (which moderated slightly between 2010 and 2019. See Johnson, 2021), during this same period 1990–2010, the average cost of a 4-year degree in the U.S. increased by 238% and in-state tuition at NH’s public institutions rose to become the second-most expensive at $16,960 (Bouchirika, 2022). Consequently, data collected by the U.S. Department of Education from 2012 to 2020 shows a higher average percentage of NH high school graduates (58.7%) leaving their home state to attend college elsewhere than any other U.S. state (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022).

The above trends led to a 2009 report by The Governor’s Task Force for the Recruitment and Retention of a Young Workforce for the State of NH, which catalyzed the launch of a nonprofit organization called Stay Work Play NH,1 a name that captures both a branding strategy and a recruitment and retention program (Governor’s Task Force, 2009). However, both the ensuing policies recommended by the Task Force and Stay Work Play’s efforts to date have focused on gathering input from and recruiting young adults 20–39 rather than on retaining youth already in the state. Thus, understanding the factors influencing the postsecondary plans of youth 14–18 is a topic of interest for both policymakers and researchers interested in youth future planning.

3.1 Research questions

NH’s changing demographic and economic characteristics present a unique opportunity to understand factors that shape youth postsecondary planning in rural states that have undergone significant transformations over the past 40 years. In particular, we were interested in how messages about educational, occupational, and quality of life domains are communicated by youth-focused institutions, and how these messages might be shaping youth postsecondary planning in intended or unintended ways. Therefore, we sought to address the following research questions:

• What explanations do people with different institutional vantage points provide for recent patterns of youth outmigration in New Hampshire?

• What do the explanations they offer suggest about how normatively prescriptive ideas about identity – i.e., master narratives – are shaping youths’ postsecondary planning?

• What are the main components of the master narrative(s) described by individuals occupying positions of influence relative to postsecondary planning? What are the implications of these components on the normative identity pressures youth face?

4 Methodology

4.1 Participant selection and interview design

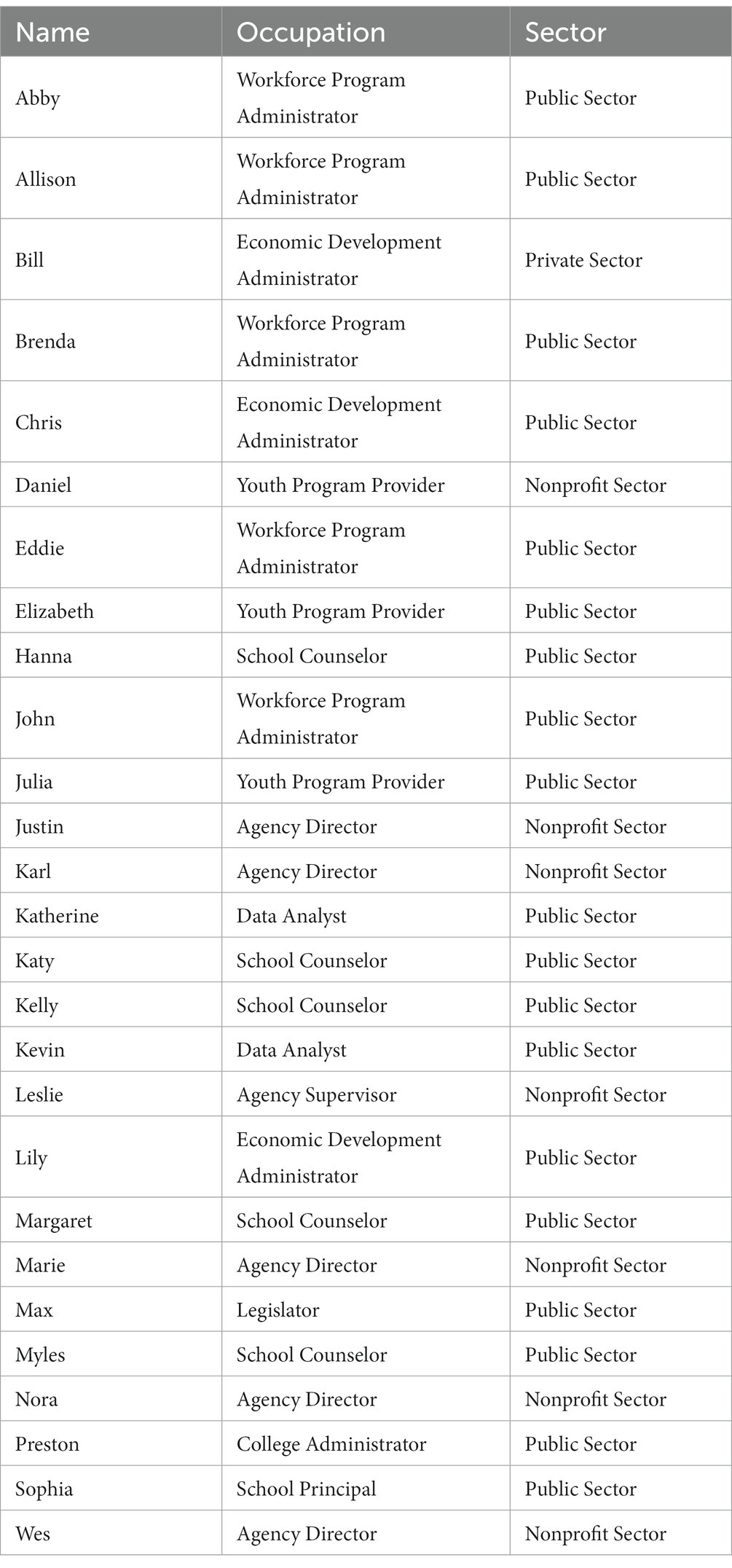

To gain insights into the way postsecondary master narratives circulate and are maintained at the social-structural level, we interviewed 33 adults occupying positions of influence relative to postsecondary planning in three main sectors: educational, occupational, and quality of life (e.g., recreation, community development). Participants were selected based on their ability to comment on how major organizations and institutions in the state are responding to youth outmigration. We began by generating a list of key informants including legislators, State department heads, statewide non-profit and association directors, and public university system administrators. We also employed a snowball strategy which expanded our initial pool to include school counselors, workforce advocates, and community service providers. Theoretically, our sampling was guided by Bronfenbrenner’s (1994) ecological systems model and was aimed at learning how people with views of macrosystem, or social-structural, conditions explain youth outmigration in NH. For confidentiality purposes, respondents were given pseudonyms and, due to their prominence as state-level leaders, their roles defined only in general terms and by sector (see Table 1). Recruitment proceeded after securing Institutional Review Board approval [University of New Hampshire; IRB-FY2021-96].

Interviews were conducted between November 2020 and June 2021 and followed a semi-structured protocol lasting between 45 and 75 min (see Supplementary material). All interviews were conducted over Zoom, recorded, and stored on our University’s secure cloud file system. Audio files were transcribed and manually cleaned using an online platform, and the resulting transcripts were then uploaded to Nvivo for coding and analysis.

4.2 Analytic approach and procedures

Tannen’s (2008) three-level narrative framework guided our analysis. In addition, we included the fine-grained linguistic elements outlined in Tannen’s (2007) text on conversational discourse as well as Schiffrin’s (2009) method of discerning narrative themes across different types of talk.

4.3 Coding phase 1: involvement strategies, scenes, and types of narrative

Tannen (2007) argued that speakers routinely use different “involvement strategies” to illustrate specific points that build into themes across conversational turns. Involvement strategies are literary conventions used to convey meaning, generate sympathy, and achieve mutual understanding, such as “recurrent patterns of sound (alliteration, assonance, rhyme)” or other features like metaphor or irony (Tannen, 2007, p. 34). Analytically, involvement strategies provide a way to begin discerning what Tannen (2008) called an interview’s “coherence principle,” or central organizing storyline or argument. Identifying speakers’ involvement strategies helped address the first level of analytic concern in Tannen’s (2008) framework: small-n narratives. As she described them, “… a small-n narrative is a series of scenes, so the concept of scene is central to our understanding of narrative and to why narrative is central to our understanding of discourse” (p. 215). Scenes, elicited and analyzed inductively (Adler et al., 2017), thus formed the building blocks of our analysis. We also coded surrounding text that was thematically connected to the scenes using Schiffrin’s (2009) characterizations of explanatory, illustrative, and intertextual functions of non-narrative responses. This approach enabled us to identify the “non-linear distribution and recurrence of themes that facilitate connections among non-adjacent parts of discourse” (Schiffrin, 2009, p. 425), aiding interpretation of what individual scenes meant in the context of one or more emerging coherence principles.

4.4 Coding phase 2: big-N narratives and master narratives

The focus on small-n narrative scenes in Phase 1 established an empirical basis for subsequent interpretation of larger themes respondents developed throughout their interviews – what Tannen (2008) called “Big-N Narratives.” A Big-N Narrative represents an “explanation, theory of causation, theme, assumption, or idea” (Tannen, 2008, p. 214). Procedurally, this involved determining what, on the whole, respondents communicated intertextually across scenes, descriptions, and explanations, then evaluating what this discovery signified as a potential causal theory of youth outmigration. Wherever possible, we used participants’ own terms to capture the “‘theories’ formulated personally by the producers of the text in question” (Böhm, 2004).

Finally, Tannen (2008) differentiated between Big-N Narratives and a master narrative, or “a culture-wide ideology that shapes the Big-N Narrative” (p. 209). As Tannen (2008) explained, identifying an underlying cultural ideology requires “discerning patterns in Big-N Narratives across multiple speakers” (p. 214). To accomplish the conceptual move from a Big-N Narrative to a master narrative we sought two important objectives in master narrative research: (1) To capture master narrative content and process, which Syed and Mclean (2023) define as follows:

Content pertains to the nature of the master and alternative narratives; how they are de-fined and conceptualized, what details are included, etc., all of which is relatively static. In contrast, process refers to how individuals relate to the master and alternative narratives, including how they negotiate, resist, internalize and perpetuate them. These are the relatively dynamic elements – how individuals interact with and make sense of the narratives. (p. 55, italics in original)

(2) To assess Big-N Narratives in relation to five key attributes: (a) utility, (b) ubiquity, (c) invisibility, (d) compulsory nature, and (e) rigidity (McLean and Syed, 2015). To qualify as a master narrative, the Big-N Narrative themes needed to be describable in these terms and possess explanatory power relative to the phenomenon of interest, which in our case was youth future planning at the secondary-postsecondary juncture with a potential relationship to outmigration as both an individual choice and a historically evolved demographic pattern.

5 Main findings

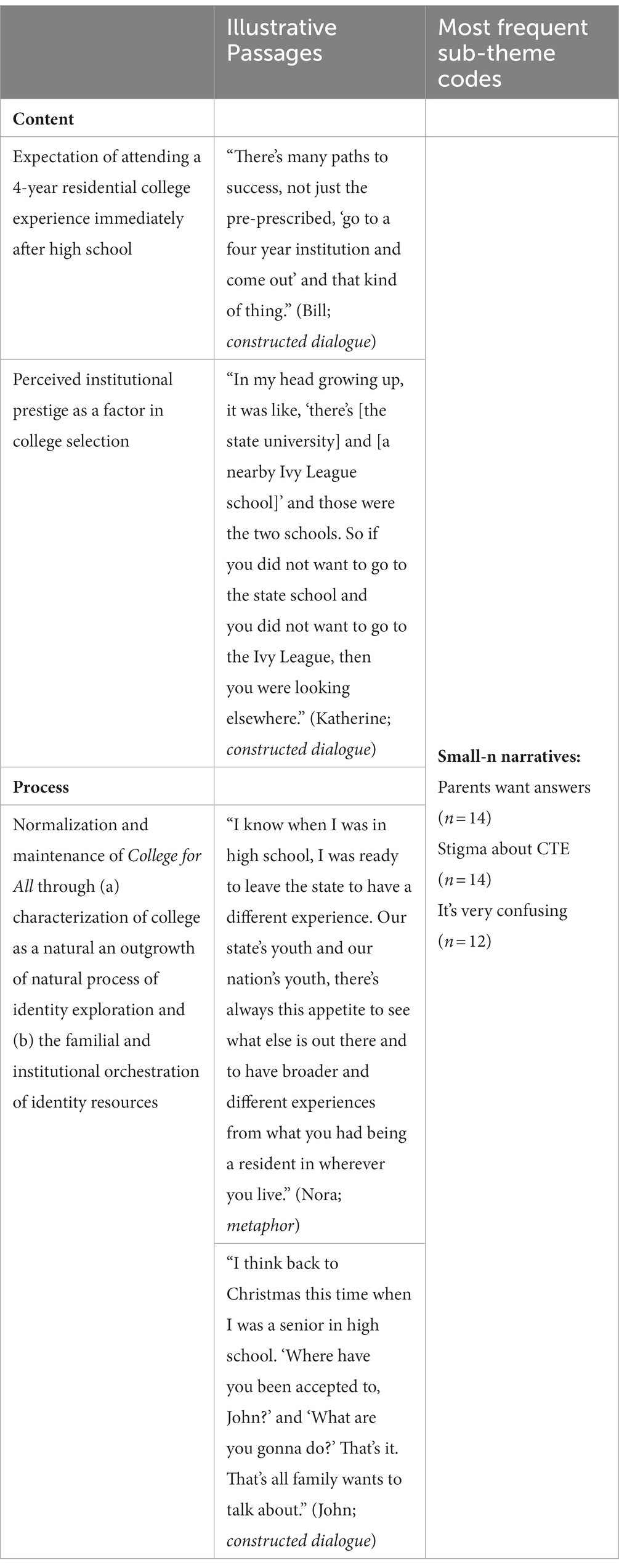

We focus the present report on the College for All master narrative (henceforth CFA) due to its ubiquity in participants’ accounts as an explanation for youth outmigration. We anticipated college to be one of the reasons our respondents gave for youth outmigration, however we did not expect it to be so pervasive; we identified more instances of CFA than any other Big-N Narrative across a majority of our transcripts (N = 29/33 [88%], 158 coding instances). Table 2 summarizes CFA as a master narrative and provides the labels of the most frequent small-n narratives used to capture themes in the data. Brief data excerpts are shown for definitional purposes.

5.1 Master narrative content

5.1.1 4-year residential college as the assumed norm

A majority of our respondents described in various ways encountering or observing a normative expectation that youth should attend a 4-year, residential college full time immediately following high school. This first core feature of CFA was succinctly expressed by Nora, who said: “when kids are in middle school and high school, there is this expectation that they go to college. And there’s a very narrow view of what is meant or articulated by college. And it’s typically that four-year bachelor’s pathway.” In other interviews, the normative expectation of attending a 4-year institution was implied rather than stated overtly: “[postsecondary planning] comes down to what your family is telling you. And there’s a very strong and clear expectation that … you will go just to traditional college” (Melanie). Likewise, when Margaret discussed youth pursuing options other than college, she enjoined the interviewer to “remember that there’s still the larger portion that go the traditional route.”

The ubiquity of CFA, evident by its coding frequency across participants occupying different positions in educational, occupational, and quality of life sectors in NH, was also expressed descriptively by Preston when he observed,

One thing that's interesting about this region is a lot of the work is already done for us because going to college in this region is an expectation for many, many, many groups. And so we don't usually have to do as much messaging around the advantages of college, unless it's a really, really, really, really low income-band student.

When asked if employers have been successful at recruiting high school students, John used repetition to emphasize the constancy of forceful messaging to the contrary: “They try. The tough part is, a lot of the high schools can be cagey about it. Because they push college, college, college.” Apart from denotationally indicating CFA’s ubiquity, the above passages are examples of terse telling (Boje, 1991), where a speaker assumes such a degree of shared meaning that no elaboration is required. Use of this linguistic device indicates an expectation of mutual understanding that “traditional college” refers to the norm of a 4-year residential college experience, even when not fully elaborated as such.

5.1.2 Institutional rank and prestige

Another element of CFA’s content is an implicit status hierarchy that prioritizes institutional rank and organizes possibilities in relation to an imagined order. Prestige as an ideological feature gives aspiration its directionality and influences a number of antecedent processes like course selection and peer relationships. This feature was expressed in a number of ways by our respondents, both in biographical form and as a matter of professional observation. For example, Abby recognized its presence in her own experiences as a parent: “It started hitting me when my kids went to high school. There was a big push when they went to high school about getting in those top level courses.”

Despite the fact that “guidance counselors” were charged in various ways by different respondents with “saying ‘four-year college or bust’” as John idiomatically stated, school counselors in one focus group expressed frustration with how a preoccupation with institutional prestige distorts motives for learning and causes social and identity conflict among their students. Employing constructed dialogue, a type of involvement strategy (Tannen, 2007), to perform the student’s side of a conversation about course selection, Katy said: “‘What are the best classes I can have my transcript to get where I want to be?’” Her colleague Hanna chimed in to extend the student’s turn: “‘What are people going to say about where I apply? Am I going to four year?’” A third colleague, Kelly, concluded by explaining how such prototypical conversations both reflect and uphold the larger social order of the school:

Peer pressure is huge from peers and their own family members or just other people. The [school’s upper-class hallway] in the Fall is always very stressful because kids will start hearing about the schools. Kids will say, “oh, you're going to …” Like [the local State University] is a not a desirable place to be at [this high school]. Literally just yesterday I was talking to this parent, and her second child is also going to [the local State University], and she's struggling with it right now. Because all of her peers are like, “you're going to [the local State University].”

Kevin echoed this sentiment when he explained in his interview, “You’ve got one of the huge educational magnets … across the border in Massachusetts. … And there’s always a lot of kids who do not want to go to the state school no matter how good it is.” Kevin’s telling accounts for prestige as a factor in outmigration by treating it as a choice driven by individual preferences, however Preston offered a more sociological assessment:

This region is so wired on private or bust, even if it's a mid-tier private or private that doesn't offer much value. There's this notion here that all privates are better, even if they're not good. And that is not healthy because it actually pushes students to take on some environments that are really expensive that honestly don't offer as much value as one would hope.

The foregoing excerpts capture two core features of CFA content: the normative idealization of a 4-year residential college experience and an implicit value hierarchy based on perceived institutional rank. These features affect goal-setting and decision-making processes in ways that are likely to produce outmigration. However, they do not explain how the CFA master narrative is normalized or maintained, which are issues of process.

5.2 Master narrative process

5.2.1 Normalizing and maintaining College for All: its invisibility and utility

Preston’s use of the metaphor “wired” to signal an innate cultural tendency points to another dimension of CFA: how its normalization and maintenance are accomplished through shared assumptions and institutional routines that can be taken for granted, which makes expectations of college-going invisible and thus difficult to unseat or counter. As Hanna explained when describing how she approaches planning meetings with students, “I usually start with, ‘what do you want to do after high school?’ I do not say ‘do you want to go to college.’ It’s very open ended. A lot of times you get – it’s almost expected – like, ‘college, duh.’” Our data suggest that such assumptions about college-going are normalized and maintained through beliefs about human nature and institutional practices that prioritize college over other options.

5.2.1.1 College-going as an expression of human nature

Laureau’s (2011) landmark study Unequal Childhoods explained how parents organize children’s activities based on their beliefs about development which varied by, and reproduced, class differences. We found evidence for a similar phenomenon regarding college-going: some respondents characterized it as an extension of a natural process of development, part of the personal exploration youth invariably undergo and for which mobility is a necessary condition. Describing a survey her rural development organization did among alumni from a high school in northern NH, Marie characterized respondents as “people who stayed, people who left and came back, and people who left and did not return.” “What was very consistent,” she explained,

was people left for primarily for college or for opportunity elsewhere, whatever that meant. There was a perception – or reality – that there just wasn't good work there, but a lot of it just had to do with, “I want to go and see the world and then perhaps come back.” … And one of the stark differences was that the people who stayed really prioritized personal safety; there was a sense of “this community will take care of me. I value that sense of familiarity.” This leads me to think that perhaps the people who left are a little more adventure seeking, more aspirational.

Several others, like Wes, used figurative language in their descriptions of why NH youth select out-of-state colleges:

I think it's a several things. One is just a natural inclination of young people to want to spread their wings a little bit and see more than just their little NH hometown, or just something different. I think you see that everywhere.

Chris assessed the situation similarly: “part of it is just human nature, you want to go to a bigger place and go somewhere else.” Eddie invoked the trope of wanderlust and also conveyed a sense of its inevitability: “That question of ‘why are the kids leaving?’ – if we can figure that answer out, then maybe we can stem the tide. [Personal finances] may not be the reason they are leaving. If they are leaving over wanderlust, we cannot help that.”

Speaking about the youth of color with whom he works, Daniel used constructed dialogue to explain the perceived alignment between natural processes of personal exploration and college-going as an opportunity for them, indicating some distinct motivations while also underscoring its universality:

The notion of – “if I want to go to college, hey, this is my chance to go somewhere else. To get out of here. Go somewhere different. Where I might be more accepted, or go somewhere different, where I can have a different experience.” And that's universal too for White kids. I mean, that's universal for all kids. It's not just immigrant youth that think that way … Some students, by the time they get to that point, they want to get out of here and they have the right to do so – that's part of living life. You want to step out and go explore.

These examples illustrate how different people understood and linked college with mobility at the psychological level beyond rational estimates of cost or residential selection: as an extension of naturally-occurring developmental processes of personal exploration and self-expression achieved by moving away. Our point here is not to evaluate the veracity of such statements, but instead to show how universal college-going as an ideal was often merged with beliefs about development through narrative processes that explain, justify, and prescribe a normative pattern with mobility as a necessary condition. This kind of invisibility is one of the ways the CFA master narrative is normalized: by providing a plausible explanation for outmigration that hides its cultural and historical specificity while also making it seem morally undesirable to inhibit or redirect.

5.2.1.2 College-going norms expressed through institutional practices

College-going expectations arise not only in conversations with counselors, parents, or other adults but are transmitted through a number of other sources in the institutional and social ecology. Examples respondents gave included sources like images on Justin’s agency website where “everybody’s wearing college sweatshirts” and his program that provides “coloring books” for “middle school and elementary ages,” or a “college awareness week” at Myles’s high school where “teachers talk about their experiences and hopefully the colleges that they went to; they send pens and pennants and t-shirts and things like that.” More subtle sources included the values reflected in school graduation metrics, where “[schools are] keeping track of two-year degree programs and four-year degree programs. They’re not necessarily keeping track of [other outcomes]” (Max) and “the gap year may make sense to the parent, but it may not make sense to the school” (Leslie). Sophia even observed how seasonal routines determined by school calendars establish a pattern of expectability:

They don't know what they're gonna do [after high school] a lot of kids. I mean, for their entire life every August they heard back-to-school commercials. And then they went back in September, and then in June, they were done and they had a couple months off. There are so many kids who just have that rhythm embedded in them, that they don't know what they're going to do next.

Such features of the institutional and social ecology add to the rigidity and compulsory nature of college-going expectations. An example shared by Allison illustrates how the reinforcement of college-going assumptions can deter alternatives even when students prefer them:

I think the sell [of a paid apprenticeship] to the student is easy, because they're gonna want to do what they think they would really like. It's the parents. … We would do tours of manufacturing companies, and the kids would be like, “this is great!” you know, “it'd be really cool to do this.” And then the next day they come back and it's like, “no I'm going … this isn't for me,” and it's like, “okay.” (Allison)

Allison’s narrated scene indicates the rigidity of expectations about college when youth are in the midst of postsecondary decision making. However, the timespan of this decision making process extends much earlier developmentally, shaped through long-term engagement with ideas and materials circulated within child-rearing institutions such that their influence on individual and family processes is made invisible and can become rigid and compulsory over time. As Brenda put it, “kids have been told and parents have been told for a very long time that that’s the way that you have got to come out and make something of yourself;” consequently, the “thought that four year schooling is a requirement is just pervasive.”

5.2.2 The utility of a College for All ideology

Master narratives persist because they help people solve both the practical problem of making consequential life decisions and the developmental problem of establishing a coherent, culturally valued identity. We detected three small-n narratives in respondents’ explanations about why college dominates as a normative ideal, which we coded it’s very confusing, parents want answers, and stigma about CTE. CFA’s core idea of aspiring to a 4-year college provides an established and highly scaffolded script for youth and families to follow while forestalling fears about drifting aimlessly, defaulting into a putatively less lucrative option like community college, or directly entering a potentially unstable workforce. Brief scenes recounted by Justin and Allison reveal the identity consequences of misalignment with CFA: “You look at people from our generation and it’s like ‘if you did not go to college, what were you doing?’” (Justin)

I can think of one student, a top student, fully planned on going to a four-year school, found out right before they were supposed to go that they couldn't afford it, and there was no way that it was going to happen. Was devastated, and then looked into the community college system. Went into it with an attitude of “fine, I'll just do this, that's not really what I want to do. But I'll do it,” and then had such a great success with it, is now a champion for things. (Allison)

Youth and families justifiably want to avoid stigma, self-doubt, and disappointment by making the right postsecondary choice, whether it is college or another option. But understanding one’s options is not easy or straightforward especially in cases that deviate from familial patterns or where limited or ambiguous information is available. The following two examples, the first narrative and the second descriptive, from individuals trying to expand access to trades and to college, respectively, reveal difficulties in each case.

[relaying an imaginary conversation with a potential apprentice] “You may not need a four-year degree, but you need to continue your education.” And I think that's a big piece that's missing when we're talking to youth. And when I talked to a couple of companies, like “please be careful when you're saying that, because you're not hiring people without experience and without education.” So when a 14, 15 year-old hears that you can be a plumber and come out and make $95,000 a year working on your own, they're not realizing that there's still four years of schooling that go into that – it's just not at a four year institution. So I think there's confusion for them. I really do. I think it's very confusing. (Allison)

When I go visit the high schools to talk about our programs with our admissions counselors, what I pick up on is a lot of the students don't realize how they can afford college because we're in the [urban] school district, where there's a lot of students with free and reduced lunch. … a lot of them just think they're just going to get a job and not go to school, because they don't recognize or understand those pathways. And they're not getting those consistent messages across the board. (Elizabeth)

The above examples allude to confusion’s meaning as an ideological and developmental concept: not only as an inability to differentiate among alternatives at a given decision point, but in the proleptic sense of not having ideational resources sufficiently assembled into the kind of “imagined scenario” that is necessary to “guide our actions toward the future, thus reducing its inherent uncertainty” (Brescó De Luna, 2017). Confusion in this sense is both communal and cumulative, and is especially acute for youth whose lives have not been organized around normative expectations of college attendance or who feel pressured to attend college when it is not a realistic or desirable option personally.

CFA alleviates confusion by providing a ready-made, culturally endorsed, and institutionally reinforced future image of having earned a “good life” (Syed and McLean, 2022) by getting a college degree. It does so via the predictable means of goal-setting and role modeling, and also by organizing attention and effort around identity resources directed to that end. Eliminating confusion in this way eases postsecondary planning, yet it also serves the deeper function of reducing anxiety about long-term financial and material security in the face of unpredictable social and technological change. When asked why some parents at her technical school are not more supportive of the school’s philosophy of steering youth toward their “their passions and interests in something that they are pursuing,” Sophia explained, “I think parents want answers. They want to know that their kids are going to be okay. And kids want that because of the great unknown. So I think they tend to start on kind of a safety path.” Constructing dialogue to make a point about parents on the precipice of a college decision, Brenda conveyed how this sense of “safety” currently exists in tension with real financial risk:

Some parents are starting to realize that “we can't afford to pay $50,000 a year to send our kids to a four-year school,” but there's still that predominant feeling that “four years is the only way you're going to rise above and do better than I did.”

Prolepsis is again a useful concept for understanding how the safety calculus of a traditional college experience should be interpreted narratively as part of the CFA ideology: First, not as a (knowingly dubious) belief about guaranteed financial security, but as a form of reassurance that one is doing everything possible to maintain an intergenerational grasp on the American dream. And second, not merely as an article of faith, but as a “social mobilizing power” that “acquires pragmatic force for current actions … according to different future goals” (Brescó De Luna, 2017). In an illustrative example of a parent conversation reminiscent of Laureau’s (2011) developmental model of concerted cultivation, a scene narrated by Katy captures the proleptic, present/future dynamic inherent in the safety/risk relationship:

You can work yourself to the bone by the time you're senior in high school and it's still not a guarantee you're going to get into these [elite] schools. … [For] the parents just it's high stakes, and everyone comes in here – even the parents who are level headed – you have to talk them through like “it's going to be okay, your child got a C+. It's going to be fine.” And they're like, “they're doomed. They're never going to be successful.” And it's ninth grade biology. It's like “take a breath.” And it's really convincing them and assuring them it's going to be okay.

Youths’ college aspirations are therefore not a direct psychic reflection of parental expectations or high school messaging, but a source of meaning inferred through everyday activities that are an important means of gaining traction on a culturally valued identity as a future college graduate.

5.3 The College for All binary: stigma about CTE and “The forgotten group”

We have presented data showing how CFA alleviates confusion by providing a compelling identity model that organizes attention and conduct around a culturally valued, future-oriented, aspirational ideal that may entail outmigration. Despite the inherent mobility implications, this can be regarded as CFA’s positively valenced pole. But what is its inverse – the thing youth are being kept “safe” from, or are at risk of? For as Brenda’s example above suggests, college today is not without significant financial risk, but debt is not the only risk respondents identified. Over half of our respondents (N = 17) narrated scenes indicating, in various ways, a stigma related to non-college options, which we coded at stigma about CTE [career and technical education]. Using an ordinal metaphor apropos to CFA’s prestige hierarchy, Marie expressed consternation over an apparent cultural tendency to “[look] down on people who do not have quote-unquote ‘professional jobs.’” Enduring this anticipated judgment during one’s secondary years requires fortitude and enterprise, as Daniel recalled from his own experiences growing up: “I had a lot of friends that did [CTE], that went into job trades: electrician, mechanics. Unless a kid who’s really driven … they leverage the crap out of that, there’s still a lot of stigma.” Eddie attributed this stigma in part to outdated parental attitudes:

How many of the parents are still under the old understanding of what voc-tech education was, who it was for, and what it was all about. And that, no, “if my kid is gonna be successful, they have to get a bachelor's degree right out of high school to be competitive in the job force.”

The idealization of college attendance after high school and the stigmatization of non-college options do not merely represent an imbalanced menu of choices; they create a binary that works ideologically by marking out unequal identity regions, one “safer” and the other riskier, as Allison expresses using the spatial metaphor of “in between”:

I think their biggest message [that youth receive] is, “is it college or is it not college?” and then with college, the new message now is, “you're going to be wasting all of your money on college and the expense of college.” And so even if they don't throw in the conversation of, “you're wasting money on continuing your education” it's more that fear of “you're going to have hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of debt, and you'll never be able to make that back.” But what's the alternative to that? There's no message in between.

The identity implications of ending up on the wrong side of this binary were expressed by Justin: “The schools still talk college first. But if you do not see yourself as a two-year, four-year college type, then you may feel like you are the forgotten student.” School counselor Katy put it exactly the same way:

It's funny that we invest a lot into the college bound students. I think a lot of those students end up dispersing. And I feel like sometimes we forget our workforce students. Those are the ones that stay in our community. … I feel like sometimes they can be the forgotten group.

Julia also used a spatial metaphor to characterize this binary tendency within her own youth organization which has launched new campus-based programs designed to support and retain its college-bound members:

What are we saying when we say, “we’re going to continue your [program] experience if you go to college?” We're not doing anything for kids that don't go to college. I feel like it's totally unintentional. Nobody meant it to be that way. But it's a message nonetheless, that we're saying: “We're done with you. If you want to come to college, great. We want to keep you. And if you don't, see ya.”

As a cultural model depicting how one can achieve a “good life” (Syed and McLean, 2022), CFA is normalized and maintained through a universe of material and narrative resources whose incorporation into personal identity is, as Erikson (1968/1994) theorized, “for the most part unconscious” (23). For those whose individual biographies align with the College for All master narrative, attendance at a four-year residential college may appear to be, and feel like, a natural culmination of personal aspirations. While this may provide important traction for youth who lack the kinds of ideological scaffolding middle-class families often assume (Laureau, 2011), its binary character also creates a formless region of non-college where “forgotten” youth – “the ones that stay in our community” – face the risk of identity stigmatization, reducing the visibility and desirability of other career options that have been shown to support successful postsecondary transision (Thouin et al., 2023).

6 Discussion

This study examined how cultural ideologies at the social-structural level configure resources for identity formation and future planning. Our concerns were motivated by conditions in a rural state in the northeastern United States, which has seen outmigration accelerate since 1990 along with persistent disparities in rural postsecondary outcomes, identity conflicts when rural youth transition to college, and emerging workforce gaps despite the presence of viable opportunities and training pathways. This research responds to recent calls to expand beyond individual-level analyses and focus on identity as a societal variable (Rogers, 2018; McLean et al., 2023).

Our findings demonstrated that a multifaceted College for All ideology is predominant in how key institutional leaders in educational, occupational, and quality of life sectors in NH understand and narrate youth lifecourse decisions involving educational and professional commitments. Drawing on narrative data and employing McLean and Syed’s (2015) criteria, we assembled evidence to substantiate CFA as a normatively prescriptive master narrative in the cultural and social-structural landscape of youth education and workforce decision-making after high school, with geographical mobility as a related entailment. The ubiquity and invisibility of CFA were features participants also recognized; few could identify precise origins or locations of the master narrative, much less where or how exactly to intervene.

Our view is that efforts to intervene on CFA and either enhance or minimize its effects requires viewing college-going not just as an individual choice but as an institutionalized developmental ideology whose concrete features are coordinated in part through narrative processes that compound over time and across settings. We concur with Thouin et al. (2023), who argued:

Notably, identity-related processes require attention. Identity development is preeminent during the transition from adolescence to adulthood, … Future studies also need to sort out synergies and intersections involving different types of factors associated with youths’ engagement in different [school to work] pathways. Paying due consideration to the interactions between structural/contextual and individual/internal factors appears especially important if research is to be better attuned to the specific realities and needs of particular subgroups, defined among other things along racial and ethnic lines.

In response to Thouin et al.’s (2023) point, our study suggests that successful interventions would need also to be narrative in nature, not just informational, schematic, or programmatic. In rural contexts,

by encouraging students to pursue certain postsecondary options without also providing them with a “roadmap” (Means et al., 2016) for how to successfully navigate their route, our efforts to ensure that they are college and career ready are selling them a dream that we are not preparing them for. (Roberts and Grant, 2021)

From a social-structural perspective on identity, navigating some kind of postsecondary “roadmap” in rural communities is partly a narrative problem. For example, undifferentiated messaging about college in rural schools may reproduce gender inequities:

As students grow up in these communities, these public narratives socialize individuals as to which career opportunities are appropriate for them to pursue, wherein fields associated with women (e.g., teaching and nursing) often require more education than those associated with men (e.g., farming and oilfield work). (Hallmark and Ardoin, 2021).

Such narrative insights expand prior insights that families and youth, particularly from marginalized backgrounds, may approach post-secondary decision making with a “rational optimism” based on cultural narratives that prompt consumers to minimize the risks and overestimate the benefits of college to particular life plans (Ovink, 2017).

Our findings also illustrate some of the domain-specific features of the CFA master narrative, such the priority placed on the institutional rank and prestige of some colleges relative to others and relative to non-college pathways, which are comparatively formless and stigmatized. This ranking dimension further constricts the educational prescriptions of the CFA master narrative in ways that rationalize “sending off all your good treasures” (Sherman and Sage, 2011) instead of making local postsecondary investments or orienting youths’ psychological striving toward other individually and socially productive aims.

6.1 Developmental and institutional features of the College for All master narrative

Analyzing CFA at the social-structural plane helps to clarify the pressures of the master narrative not only as a biographical prescription, but also as an ideological force structuring the landscape of youth postsecondary planning into interrelated developmentally and institutionally normative features. Our choice to interview individuals occupying positions of influence in the youth postsecondary policy space was based on their institutional proximity, but not on the assumption that they had greater visibility of the CFA master narrative than, for example, youth or families (see Vélez-Agosto et al., 2017). Indeed, the present study corroborates prior research on how master narratives are messaged via concrete institutional policies, practices, and artifacts in multiple settings that facilitate identity formation and guide decision making (Dvorakova, 2022).

Another data excerpt provides an example of CFA’s multi-sited, longitudinal nature. By the time children are juniors or seniors in high school, families have encountered many institutionalized messages about college-going, as illustrated by a summer camp marketing pitch to parents that Karl rehearsed in his interview:

When I talk to parents about the type of commitment that coming to an overnight program involves, we talk about how “one of these days, little Johnny's going to, it's going to be time to think about going to college, and as he transitions to that phase of his life, having already had the experience in a in a very controlled and managed environment of being on his own, or on her own, is an experience that they need to feel confident to step out and apply to go to college.”

The viability of this pitch is dependent on a mutually understood ideological ecosystem informed by the assumptions and promises of CFA. Marketing a summer camp experience on the basis of a child’s projected readiness to leave home for college is an example of an ideational resource for identity formation (Nasir and Cooks, 2009), constructing an idea of children’s eventual future to which parents proleptically orient their present expectations and efforts (Cole, 1996).

The above summer camp example details just one of many settings in which youth and families encounter CFA institutionally. In schools, navigation of the institutional logics and manifestations of CFA carries enormous consequences. The multiple close ties that high-achieving students and families cultivate with school counselors, afterschool programs, sports teams, and the like may contribute to an overarching identity narrative that facilitates personal and biographical connections to college-going (Carnevale et al., 2021). In this sense, institutional agents possess significant responsibility, especially for marginalized communities, to transmit timely and accurate information (Missaghian, 2021). However, in the case of many rural communities, these imagined futures often appear to include outmigration imperatives (Sherman and Sage, 2011).

CFA’s rigidity and compulsoriness may also derive effects through coordination with several other complementary cultural ideologies. One such cohort-adjacent ideology is the meritocratic “getting ahead” motive and value paradigm that pervades middle-class developmental and parenting ethnotheories (Rogoff, 2003; Plaut and Markus, 2005). Because of schooling’s strict chronological age progression (Chudacoff, 1989), the meritocratic return on middle-class parents’ early investments may be perceived as (a) deferred until after high school and (b) expressed as postsecondary opportunities that earlier investments enable youth to access. Given that many youth in middle-class families leave home after finishing high school, parents may further construe the outcomes of youth postsecondary planning as a personal achievement that fulfills latent investments in their children’s futures.

Second, youth, families, and communities not only adopt master narratives like CFA as useful resources for lifecourse planning during an otherwise fraught developmental period, but also, in doing so, are drawn into collective meritocratic projects such as the American Dream:

The “College for All” discourse portrays a future in which equity, excellence, and international competitiveness are interwoven into a compelling narrative of progress—both individual and collective … unit [ing] social actors across the political spectrum only by incorporating liberal ideals of equity into the logic of neoliberalism (the primacy of individual self-interest, markets, and profits), and by representing the global changes driven by advanced capitalism as inevitable facts that require individuals to adjust to them, rather than as contested realities open to alternative interpretations and futures. (Glass and Nygreen, 2011)

Understanding how CFA works in coordination with other ideological narratives helps to situate its logic within broader economic and sociopolitical frames, amounting to a culturally normative paradigm of youth future decision making that appears to overshadow and stigmatize alternative educational and workforce pathways – despite emerging opportunities in growing industry sectors and alternative ways to earn a college degree that might be more financially viable for rural or other marginalized youth.

6.2 Limitations and future directions

This study examined how individuals occupying positions of influence in educational, workforce, and quality of life sectors explained the reasons for youth outmigration due to influences on postsecondary decision making. Given their roles, it is perhaps unsurprising that college emerged as a prominent theme in their observations about youths’ decisions. However, their stories illuminated their own personal and professional experiences with CFA as well as idealized versions that helped to identify some of its nuances. These insights were aided by the adoption of a narrative approach; by their nature narrative depictions are idealized because “youth comes to be read against a horizon of expectations based on other texts and our own experiences that emphasizes a continuity between our literary and personal experiences of youth” (Reynolds, 2017). An advantage to such idealized depictions is that they tend to draw more explicitly from ideological aspects of messaging and discourse related to CFA – a crucial source of insight into master narratives. This is a strength of narrative analysis, and it points to important areas of future research with other participants such as youth, families, current college students, and those who pursue alternative career paths in rural or other areas.

Our narrative findings buttress existing research on the effects of college planning in rural communities (e.g., Corbett, 2005; Sherman and Sage, 2011). But college may not be the only option that compels youth as its costs increase; understanding how youth and families themselves work to coordinate, align with, and even hybridize across personal and master narratives will reveal both important empirical and conceptual insights as well as opportunities for policy intervention (e.g., Jusseaume, 2023). On this point, a number of respondents alluded to the fact that CFA is currently facing structural limits, leading to “fracturing” or weakening of the master narrative (Smith and Dougherty, 2012). For example, Leslie explained:

I feel like we might be [at] a bit of a turning point where [there] is still a lot of push to go to college. And many students, we're still hearing that message and probably still arguing that message. But I also feel like I'm hearing more parents are saying, “well, maybe don't rush off to college if you don't know what you want to do. Consider the trades. Just don't rush into to having all that college debt if you're not sure what pathway you want to go on.” Of course, parents thinking that, saying that doesn't mean that schools aren't still pushing it and I'm not trying to suggest that it's not good to pursue post-secondary education. But I just feel like there's more of an awareness of it doesn't have to be the automatic next thing that students do.

These fractures appear to be taking hold as a function of factors like college cost, but also in terms of intervening ideologies related to youth entrepreneurship, lifestyle commitments related to leisure, and a growing public skepticism regarding college-going as a worthwhile lifecourse investment. Nonetheless, alternative narratives remain difficult to imagine and construct at the individual level. Interventions that leverage known strengths or emerging economic sectors may provide opportunities to understand alternative narrative processes (e.g., Seaman and McLaughlin, 2014; Hartman and Bonica, 2019).

7 Implications and recommendations

Postsecondary decisions occur at a time when individuals may rely especially heavily on master narratives for guidance both for future actions and as a way to organize and justify/rationalize previous experiences, bolstering CFA’s utility at a pivotal point in youth identity formation. Our position is that broadening actual postsecondary options requires policy change such as expanding workforce and higher education pathways (see Anderson and Nieves, 2020). We found strong agreement with these policy recommendations among our interviewees, yet also learned some of the challenges related to implementation. Everyone we interviewed endorsed practices like internships, early career exposure, and stronger links between school counseling offices and local postsecondary opportunities. We concur that these structures should be expanded. Indeed, in NH, many of these structures exist or are starting to be instituted, if unevenly. Our analysis also suggests the importance of coupling structural policy changes with cultural strategies involving expanded life-course narratives, since normative alignment from subjective points of view will determine their viability. For example, if non-college pathways lack definition and continue to be stigmatized, arranging them into a compelling alternative biographical form will be difficult for individuals to accomplish. Collecting biographical stories of and profiling successful “ambitious stayers” (Wang et al., 2021) who have created different models of “the good life” (Syed and McLean, 2022) for themselves in rural communities could be one strategy to explore empirically and programmatically.

Because the narrative forms of identity-relevant postsecondary decisions are consequential not only to individuals but also to communities and institutions, they deserve greater recognition as opportunities for policy attention, intervention, and coordination.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because data includes information that is identifiable by person and organization. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to amF5c29uLnNlYW1hbkB1bmguZWR1.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of New Hampshire Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. AC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft. CH: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. ES: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. MD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding for the research reported in this article was provided by the University of New Hampshire Collaborative Research Excellence (CoRE) Initiative.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1257731/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Adler, J. M., Dunlop, W. L., Fivush, R., Lilgendahl, J. P., Lodi-Smith, J., McAdams, D. P., et al. (2017). Research methods for studying narrative identity: a primer. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 8, 519–527. doi: 10.1177/1948550617698202

Agger, C., Meece, J. L., and Byun, S.-Y. (2018). The influences of family and place on rural adolescents’ educational aspirations and post-secondary enrollment. J. Youth Adolesc. 47, 2554–2568. doi: 10.1007/s10964-018-0893-7

Anderson, N., and Nieves, L. (2020). ““College for All” and work-based learning: two reconcilable differences” in Working to learn: Disrupting the divide between college and career pathways for young people. eds. N. S. Anderson and L. Nieves (London: Palgrave Macmillan)

Aud, S., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Kristapovich, P., Rathbun, A., Wang, X., and Zhang, J. (2013). The condition of education: the status of rural education, Washington, DC, National Center for Education Statistics-Institute of Education Sciences.

Bamberg, M. (2011). Who am I? Big or small – shallow or deep? Theory Psychol. 21, 122–129. doi: 10.1177/0959354309357646

Bergen, K. M. (2010). Accounting for difference: commuter wives and the master narrative of marriage. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 38, 47–64. doi: 10.1080/00909880903483565

Böhm, A. (2004). “Theroetical coding; text analysis in grounded theory” in A companion to qualitative research. eds. U. Flick, E. Kardoff, and I. Steinke (London: Sage Publications)

Boje, D. M. (1991). The storytelling organization: a study of story performance in an office-supply firm. Adm. Sci. Q. 36, 106–126. doi: 10.2307/2393432

Bouchirika, I. (2022). How much has college tuition increased in the last 10 years? [online]. Research.com. Available at: https://research.com/universities-colleges/college-tuition-increase (Accessed April 1 2023).

Brescó De Luna, I. (2017). The end into the beginning: prolepsis and the reconstruction of the collective past. Cult. Psychol. 23, 280–294. doi: 10.1177/1354067X17695761

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). “Ecological models of human development” in International encyclopedia of education. eds. M. Gauvain and M. Cole (New York: Freeman)

Byun, S., Irvin, M. J., and Meece, J. L. (2015). Rural-nonrural differences in college attendance patterns. Peabody J. Educ. 90, 263–279. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2015.1022384

Carnevale, A. P., Cheah, B., and Wenzinger, E. (2021). The college payoff: more education doesn’t always mean more earnings. Washington, DC: Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy Center on Education and the Workforce.

Carr, P. J., and Kefalas, M. J. (2010). Hollowing out the middle: The rural brain drain and what it means for America. Beacon Press.

Chudacoff, H. P. (1989). How old are you? Age consciousness in American culture, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Cole, M. (1996). Cultural psychology: a once and future discipline, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Corbett, M. (2005). Rural education and out-migration: the case of a coastal community. Can. J. Educ. 28, 52–72. doi: 10.2307/1602153

Côté, J. (1996). Sociological perspectives on identity formation: the culture–identity link and identity capital. J. Adolesc. 19, 417–428. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0040

C-SPAN (2000). George W. Bush NAACP 2000. Available at: https://www.c-span.org/video/?c4450116/george-w-bush-naacp-2000

Dvorakova, A. (2022). Identity in heterogeneous socio-cultural contexts: implications of the native American master narrative. Cult. Psychol. 28, 43–64. doi: 10.1177/1354067X19877913

Egan-Robertson, D., Curtis, K. J., Winkler, R. L., Johnson, K. M., and Bourbeau, C. (2023). Age-specific net migration estimates for us counties, 1950-2020 (Beta release). University of Wisconsin-Madison. Available at: https://netmigration.wisc.edu/

Esteban-Guitart, M. (2012). Towards a multimethodological approach to identification of funds of identity, small stories and master narratives. Narrat. Inq. 22, 173–180. doi: 10.1075/ni.22.1.12est

Farrugia, D. (2016). The mobility imperative for rural youth: the structural, symbolic and non-representational dimensions rural youth mobilities. J. Youth Stud. 16, 836–851. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2015.1112886

Fivush, R., Habermas, T., Waters, T. E. A., and Zaman, W. (2011). The making of autobiographical memory: intersections of culture, narratives, and identity. Int. J. Psychol. 46, 321–345. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2011.596541

Glass, R. D., and Nygreen, K. (2011). Class, race, and the discourse of ‘College for All.’ A response to ‘schooling for democracy’. Democr. Educ. 19, 1–8.

Governor’s Task Force. (2009). Final report of the Governor's task force for the recruitment and retention of a young workforce for the state of New Hampshire. Concord, NH.

Hallmark, T., and Ardoin, S. (2021). Public narratives and postsecondary pursuits: an examination of gender, rurality, and college choice. J. Women Gend. High. Educ. 14, 121–142. doi: 10.1080/26379112.2021.1950741

Hamilton, L. C., Hamilton, L. R., Duncan, C. M., and Colocousis, C. R. (2008). Place matters: challenges and opportunities in four rural Americas. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire Carsey Institute.

Hammack, P. L. (2006). Identity, conflict, and coexistence: life stories of Israeli and Palestinian adolescents. J. Adolesc. Res. 21, 323–369. doi: 10.1177/0743558406289745

Hammack, P. L., and Toolis, E. E. (2015). Putting the social into personal identity: the master narrative as root metaphor for psychological and developmental science. Hum. Dev. 58, 350–364. doi: 10.1159/000446054

Hartman, C., and Bonica, M. J. (2019). A transdisciplinary, longitudinal investigation of early careerists’ leisure during the school-to-work transition. J. Leis. Res. 50, 438–460. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2019.1594467

Hillman, N. W. (2016). Geography of college opportunity: the case of education deserts. Am. Educ. Res. J. 53, 987–1021. doi: 10.3102/0002831216653204

Huerta, A., Mcdonough, P. M., and Allen, W. R. (2018). “You can go to college”: employing a developmental perspective to examine how young men of color construct a colllege-going identity. Urban Rev. 50, 713–734. doi: 10.1007/s11256-018-0466-9

Johnson, K. M. (2021). Modest population gains, but growing diversity in New Hampshire with children in the vanguard. Regional Issue Brief. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy.

Johnson, K. M. (2023). Migration sustains New Hampshire’s population gain: Examining the origins of recent migrants. National Issue Brief, Issue. Available at: https://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/464/

Johnson, S. R. L., Blum, R. W., and Cheng, T. L. (2014). Future orientation: a construct with implications for adolescent health and wellbeing. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 26, 459–468. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2013-0333

Johnson, K. M., and Lichter, D. (2019). Rural depopulation in a rapidly urbanizing America. National Issue Brief. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy.

Jordan, J. L., Kostandini, G., and Mykerezi, E. (2012). Rural and urban high school dropout rates: are they different? J. Res. Rural. Educ. 27, 1–21.

Jusseaume, S. (2023). Narrative insight into how rural, first-generation college students and their families establish non-deficit, multi-sited identities. Ph.D., University of New Hampshire.

Kerrick, M. R., and Henry, R. L. (2017). "Totally in love": evidence of a master narrative for how new mothers should feel about their babies. Sex Roles 76, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11199-016-0666-2

Kinzie, J., Palmer, M., Hayek, J., Hossler, D., Jacob, S. A., and Cummings, H. (2004). Fifty years of college choice: social, political and institutional influences on decision making. Indianapolis, IN: Lumina Foundation for Education.

Koricich, A., Chen, X., and Hughes, R. P. (2018). Understanding the effects of rurality and socioeconomic status on college attendance and institutional choice in the United States. Rev. Higher Educ. 41, 281–305. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2018.0004