- 1Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 2Connecticut College, New London, CT, United States

Introduction: A substantial amount of evidence suggests a negative association between traumatic experiences and mental health among primary and secondary school students. These vulnerable students are at an increased risk of academic, social, and emotional problems. However, there is limited evidence on the connection between traumatic experiences and student mental health in higher education, especially regarding trauma-related content in classrooms. This study aims to explore students’ experiences with traumatic material in a UK university setting and to understand educators’ perceptions of trauma-informed pedagogy.

Methods: Eight students from the University of Manchester and seven educators (from the humanities and social sciences departments) participated in one-on-one semi-structured interviews. The analysis adopted an inductive thematic approach.

Results: Four major themes emerged from the interview data: Inclusion and delivery of trauma-related content in higher education; Effects of trauma-related content on class attendance; Availability of support systems for handling trauma-related content; Perceptions on trauma-informed education.

Discussion: The implications of this study for future research and current teaching practices are discussed. Recommendations are provided for teaching sensitive material. Limitations of this study, such as sample size and demographics, are acknowledged. Additionally, a conceptual framework for trauma-informed pedagogy is introduced, laying the groundwork for an upcoming concept paper.

Introduction

Psychological trauma represents a complex neuropsychological phenomenon known to disrupt homeostasis and nervous system function (Agorastos et al., 2019) – placing significant strain on various aspects of everyday life ranging from our emotions and relationships to career objectives and academic achievement. This highlights the pervasive nature of trauma and the potential it has to derail an individual’s life. The US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014) defines individual trauma as: “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.” SAMHSA highlights the broad scope of potential traumatic experiences and emphasizes the lasting adverse effects of trauma on multiple dimensions of an individual’s well-being. The inclusion of multiple dimensions of well-being implies that recovery from trauma may require a holistic approach that addresses various aspects of an individual’s life. The key point here is that the individual perceives the event or events as harmful or threatening, which contributes to the development of trauma. This suggests that trauma can have far-reaching effects that extend beyond the immediate aftermath of the traumatic event.

The significance of trauma to student mental health and academic achievement has been increasingly recognized over recent years. Researchers and educators have recognized the importance of understanding the impact of trauma on students’ mental health and how it can affect their academic performance (Kennedy and Scriver, 2016; Becker-Blease, 2017; Chan et al., 2020; Imad, 2020; Tsantefski et al., 2020; Guzmán-Rea, 2021; Imad, 2021; Anzaldúa, 2022; Prabhu and Carello, 2022; Sweetman, 2022). As a result, emerging concepts focused on developing trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education have surfaced (Jolly, 2011; Chan et al., 2020). Trauma-informed pedagogy – rooted in the theory of Universal Design for Learning and trauma-informed practice (Bloom, 2010; CAST, 2018)—is an approach to teaching and learning that acknowledges the presence and impact of trauma in students’ lives and enables educators to appreciate that trauma exposure among students may impair self-regulated learning and result in academic challenges that include assignment completion, engaging with peers as well as quitting a course or even a degree program (Imad, 2022; Lecy and Osteen, 2022).

The discrepancy in the adoption of trauma-informed teaching and learning practices between primary/secondary education (K-12/P12) and higher education is noteworthy. While the concept of being trauma-informed educators and institutions has been embraced by primary and secondary (K-12/P12) school educators as well as policymakers for several decades (Morton and Berardi, 2018; Thomas et al., 2019; Stratford et al., 2020; Scannell, 2021), the conversation in higher education has only gained traction over the last decade – with much of this discourse originating in social work education, a field that is intimately familiar with the impacts of trauma on individuals and communities (Carello and Butler, 2015; Thomas, 2016; Negrete, 2020; Voith et al., 2020). Notable in this regard is the extant literature suggesting that as much as 85% of students in higher education have experienced one or more traumatic events (Frazier et al., 2009), that remain a constant part of their lives (Cunningham, 2004; Read et al., 2011; Butler et al., 2017; Guzmán-Rea, 2021; Lecy and Osteen, 2022). These traumatic experiences not only affect vulnerable individuals but can impact individuals collectively or in some cases, be passed down generationally (viz., intergenerational trauma) (Gaywish and Mordoch, 2018). Among socially vulnerable students including refugees, LGBQT people, and those racialized or ethnically minoritized, traumatic experiences (e.g., abuse, violence, COVID-19, natural disasters or death) can heighten existing mental health problems triggering a cascade of anxiety and fear culminating in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Cless and Nelson Goff, 2017).

Against this background, Carello and Butler, among others, have drawn attention to the use of trauma-informed care principles in higher education classrooms as a means to practice teaching safely (Carello and Butler, 2015). As a cornerstone of trauma-informed education, teaching safely ensures that students are adequately supported to better manage academic, social and emotional challenges. However, it is important to note that the requirements of any student who has experienced trauma are uniquely distinct and as such there is no one size fits all framework, an aspect that requires educators to design the ideal or optimum space for engagement (Parker and Hodgson, 2020). As such, Carello and Butler emphasize that educators should be knowledgeable and skilled in presenting potentially trauma-triggering or retraumatizing materials while being vigilant in identifying signs and symptoms of existent and/or emergent trauma in students (Carello and Butler, 2015). By adopting these principles, educators can better support students who may have experienced trauma and minimize the risk of retraumatizing them.

While effective trauma-informed approaches in classroom settings involve creating holistic and sustainable changes that can be adopted at all levels of higher education institutions, there is recognition that everyone in an institution – regardless of their faculty, rank or level – should be trained to promote the well-being of vulnerable students. Notable in this regard are the six principles recommended by SAMHSA for providing effective trauma-informed care in organizations (e.g., colleges and universities) that include: (1) Safety; (2) Trustworthiness and Transparency; (3) Peer Support; (4) Collaboration and Mutuality; (5) Empowerment and Choice; and (6) Cultural, Historical and Gender Issues (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Imad added two additional principles: Empower Students to Self-Regulate and Impart to Students a Sense of Purpose (Imad, 2022). Each of these principles represent key elements when working in a classroom setting or engaging with students studying at higher educational institutions who may have been impacted by trauma. And it is for these guiding principles that neglecting the impact of trauma on students could be seen to constitute a form of institutional betrayal (Imad et al., 2023).

Rationale for the study

University courses in disciplines including the humanities and social sciences often utilise classroom material depicting traumatic events such as violence, accidents and natural disasters. This material is presented in various forms ranging from video clips and images to written works and the educator’s personal experiences of trauma. While delivering this form of material in the classroom to promote student critical thinking, learning and engagement may seem pedagogically sound, it is not without some risk (Carello and Butler, 2014). Specifically, students who have experienced trauma in their personal lives may feel they are at risk of being retraumatized (Carello and Butler, 2015). Furthermore, other students can also be indirectly affected when exposed to difficult or disturbing material (i.e., secondary traumatic stress otherwise known as vicarious trauma). To date, little remains known about how courses in which traumatic experiences or content is disclosed can impact the well-being and academic achievement of students in higher education. This is of particular import when considering the evidence which suggests that individuals who have experienced trauma are more likely to embark on university courses and/or careers that may serve to resolve the abuse that they experienced as children (Bryce et al., 2023). The implication here is two-fold. On one hand, these students may bring a rich, lived experience to the academic discourse, providing valuable perspectives. On the other hand, these very students may be at a greater risk of retraumatization or vicarious trauma when course material delves into difficult topics. Here, we add to the scant literature by investigating how traumatic material can be more effectively delivered within a university classroom environment.

Methodology

Materials and methods

Study design

The study objectives were addressed using a qualitative design (Crabtree and Miller, 1999; Creswell and Guetterman, 2019). Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Manchester on August 19th, 2022 (Ref: 2022-14,803-25126). Participants consented to participate by filling out and returning a signed consent form.

Participants and procedures

Two purposeful sample participant groups were recruited to take part in this study. Sample one was comprised of students (undergraduate and postgraduate) from the University of Manchester, whereas sample two consisted of educators who taught in the humanities and social sciences at the university level. In addition, snowball sampling – a purposeful method of data collection in qualitative research (Naderifar et al., 2017) – was conducted among educators by asking whether they could recommend other individuals with expertise in trauma-informed pedagogy who could offer insight relevant to the study objectives. All included student participants had undertaken the Emergency Humanitarian Assistance course, a module offered at the undergraduate and postgraduate level by the Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute (HCRI) that focuses on exploring the different aspects of mounting a humanitarian response, from recognition and initiation of a response through to the delivery of the different essential components that are at the root of a successful humanitarian mission.

Initial contact was made with all participants via e-mail with information sheets attached and interested parties were invited to contact the researchers directly. Following a positive response, the interviewer arranged a date and time for the interview to take place and sent a Zoom link and calendar invite to the participant. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the first author (BB; Male), a Lecturer in Global Health who has previous experience in qualitative research. A total of 115 individuals were invited to participate. Those who did not participate either declined participation or did not respond, with some participants contacted in the snowball sampling procedure responding after the deadline had passed. Fifteen individuals completed interviews.

Tools

A qualitative interview guide was developed and reviewed by a specialist in trauma-informed pedagogy (Dr. Janice Carello, Associate Professor, Pennsylvania Western University). Three pilot interviews were conducted. Questions were designed to elicit interviewees’ reflections on how traumatic material can be more effectively delivered within a classroom setting.

Data collection and analysis

Interviews were conducted in English between September 7th and December 8th, 2022. Participants were interviewed online via Zoom and each interview lasted approximately 40 min. Only the interviewee and interviewer were present on the Zoom calls. At recruitment stage, and again at the beginning of the interviews, participants were informed that the interview data would inform how traumatic material can be more effectively delivered within a classroom setting and to provide guidance for educators working in a university setting with an aim to improve trauma-informed educational practice. Each participant was interviewed at length and advised that they may contact the interviewer to make any additional comments of clarifications by e-mail if they wished. However, no further data was submitted in this way.

Interviews were audio recorded, with verbal and digital consent obtained from participants. The interviewer took field notes which were de-identified and securely stored to assist thematic development. Recordings were transcribed verbatim, and transcripts were de-identified by removing names, affiliation, and locations. Each transcript was checked for accuracy against recordings. Participants were offered the opportunity to view their transcripts and redact or change any information and were asked to verify and approve direct quotes prior to inclusion in the study. All the quotes proposed were approved to be included, with only minor grammatical and syntactical changes requested. Data was analyzed thematically in NVivo 12, using an inductive approach. A coding tree was developed by the first author (BB) and discussed with the co-author (MI) to reflect insights emerging from the interviews. Following this, the codes were revised to identify common themes in the data. The coding and theme development process was completed by BB and further checked and validated by MI to ensure intercoder reliability, an aspect known to increase the transparency of the coding process as well as promote reflexivity, consistency and dialog within research teams (O’Connor and Joffe, 2020). The themes were refined in collaborative discussions between the co-authors.

Results

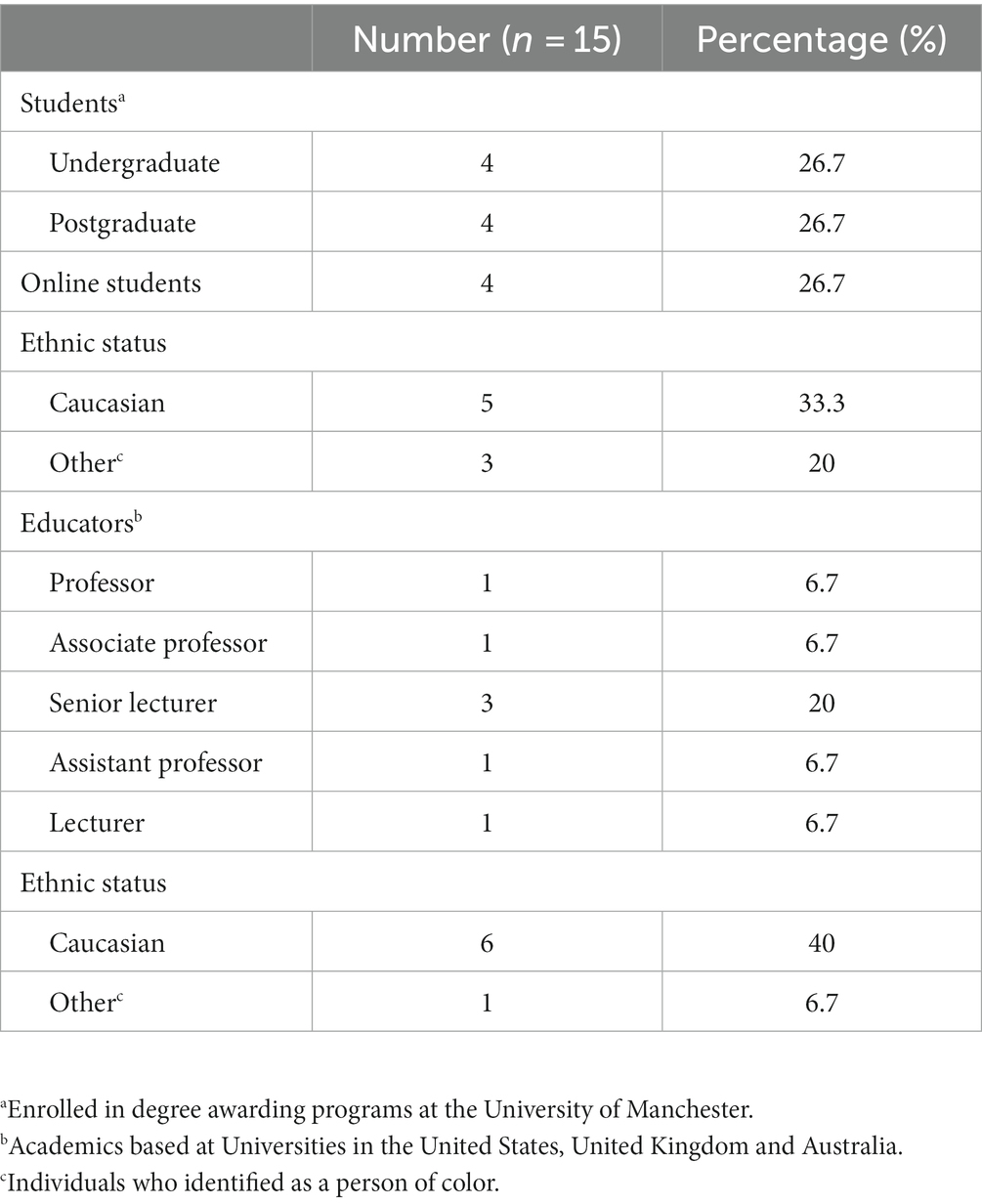

The demographic characteristics of participants and the themes that emerged from the study are presented below. Four themes arose from the data analysis: 1) inclusion and delivery of trauma-related content in higher education, 2) effects of trauma-related content on class attendance, 3) access to support systems for dealing with trauma-related content, and 4) perceptions on trauma-informed education.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

A total of 15 (13%) individuals agreed to participate in the one-on-one interviews. The majority of the participants were female (n = 10). Over half of the participants (n = 8) were students enrolled on a degree awarding program at the University of Manchester (undergraduate n = 4; postgraduate n = 4) with 4 students self-identifying as a person of color. Seven of the participants were educators (Professor n = 1; Associate Professor n = 1; Senior Lecturer n = 3; Assistant Professor n = 1; Lecturer n = 1), all of whom taught on programs related to the humanities or social sciences at Universities in Western countries (e.g., United Kingdom, United States, and Australia). The detailed demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1.

The knowledge shared by students

Within the present study we analyzed interview conversations from University of Manchester students to help understand how traumatic material can be more effectively delivered within a classroom setting. Student interviews consisted of ten main questions that addressed the students’ experiences. We commenced by probing students in relation to the inclusion of sensitive material in lectures.

Inclusion and delivery of trauma-related content in higher education

The inclusion of sensitive content in lectures remains a controversial issue, with lingering questions ranging from the implications of trigger warnings, age and resilience when confronted with trauma-related material, emotional aspects of engaging with trauma-related material and the impact of humanitarian courses on better dealing with personal trauma. Notably, advocates of incorporating sensitive content into higher education emphasize that engaging such an approach can assist in preparing students for real life situations they may encounter during their respective careers (Kostouros, 2008). This view is echoed by a student who described the benefits of delivering sensitive information in class:

“I think it’s very necessary because it brings to life some of the text that you’re reading and sometimes it’s all very good reading about this stuff in journal articles and in academic journals but when you see it in real life it triggers something inside you where you’re like no that’s real, that has real implications.” (Participant C, Undergraduate Student)

In a similar vein, a postgraduate student stated:

“I think it’s very important and it’s meaningful and I do agree that it is necessary because it aligns with the reality of the situations that we’re studying whether you mean to move into it professionally or not.” (Participant K, Postgraduate Student)

An important factor in relation to including sensitive content in a classroom setting is the need for the provision of a safe and open space (viz., a “sanctuary,” Bloom, 2010). In this regard, one student made the following comment:

“I think it is important to create a safe and open environment in the classroom to begin with. Because if students don’t feel like they can talk to their lecturer then that’s a real issue.” (Participant O, Undergraduate Student)

The impact of culture

While research has shown trauma-informed practices can benefit students (Hunter, 2022), it is also understood that one-size-fits-all programs do not necessarily work. In order for trauma-informed practices to be meaningful for students their educators must question as to whether those practices are being delivered in a culturally responsive and effective way. In this context, one student explained:

“Sexual violence against women is something we don't learn in our culture [Japanese]. It is something that people don't really speak about or is even included on the curriculum. So, I got more disturbed by this [sexual violence] than being exposed to material of people being shot.” (Participant I, Postgraduate Student)

Emotive response following exposure to traumatic-related material

When describing emotions following exposure to traumatic material, students often spoke of emotional self-regulation. They described these experiences in relation to mental health. In one student’s words:

“I think when going into that [work] setting you’ve got to know how to deal with your mental health and know how to do things healthily rather than sort of pushing things [emotions] to the side and that can start from when you’re learning at university.” (Participant O, Undergraduate Student)

Other students recognized that engaging directly with traumatic material made them more attuned to their work. For instance, one postgraduate student made the following statement:

“I think I felt calm and empathetic, and I definitely felt connected to the material, especially considering the type of work that I do as a Project Coordinator for Doctors without Borders in Myanmar. I didn’t feel uncomfortable or frightened or nervous or anything like that.” (Participant K, Postgraduate Student)

How course material has helped you deal with trauma in your life

As students discussed their experience of how attending courses that present traumatic material has impacted their educational journey, some disclosed experiences with racism and family ‘dysfunction’ that took place before and during their university studies. Students who were able to see positive effects, such as better understandings in terms of personal relationships, noted that these positive effects were accompanied by painful memories. One student explained:

“My mum is a refugee from Uganda. I think my mum and I haven’t had the best relationship; it’s been kind of rocky because there’s some generational trauma and I think it’s helped me understand a lot more about everything that’s going on with her. Because I understand now, you’ve been through a lot, and I’ve seen what you’ve been through, and I study it every single day and I appreciate her a lot more for it.”

Age and mental health resilience when confronted by trauma-related material

A widely accepted psychological concept is that age differences in terms of mental health resilience can contribute to diverse outcomes in mental health (Rossi et al., 2021). As such, mental health resiliency in relation to student age gap may also be reflected in terms of mental health acuity in a classroom setting. One postgraduate student described the effects of age in relation to resilience when being confronted by trauma-related material in the following way:

“At my age [35], when I see something like this, I can probably cope with it, I can be resilient and tolerant, but I think for the young people they take time, they need a bit of experience to be OK with it.” (Participant A, Postgraduate Student)

Trigger warnings

The use of trigger warnings is common in academic settings and are meant to forewarn audiences of content that may be distressing. Most frequently, trigger warnings have been used to preface material related to significant traumas such as violence, sexual assault and suicide, that individuals might find upsetting, although their use remains debatable (Bridgland et al., 2022). In this context, many students highlighted the benefits of using trigger warnings, particularly for individuals who may be struggling with their mental health and have experienced traumatic events. As one student explained:

“I was surprised when I saw ‘it’ [trigger warning] almost because I took it for granted that this is the type of information that we would be studying and looking at. I think it was a good thing definitely. I think now we recognize the importance of having trigger warnings particularly for people who might be struggling or who might have had negative experiences in the past.” (Participant K, Postgraduate Student)

Other students opined as to whether trigger warnings are relevant, with one undergraduate student describing the use of trigger warnings in the following way:

“I mean personally, for me I don’t think it’s relevant. Not because of some bravado, it’s because I’ve chosen this course because this is the sort of context I want to be deployed to. I mean, I think for me the whole course is just a trigger warning.” (Participant E, Undergraduate Student)

Delivering effective trauma-informed education

When describing effective ways to deliver trauma-informed education, students spoke of creating an inclusive environment whereby their personal experiences and career ambitions are made aware to the educator so that it can better help shape the material that is delivered within the classroom. As one student explained:

“If I was a lecturer, I would request the students to share their personal experiences and what is the career they want to pursue. So, does this course that I'm teaching align with the career of the student or not? I will want to know that information before choosing what kind of material I share with the students.” (Participant G, Postgraduate Student)

Effects of trauma-related material on class attendance

Content delivery is perhaps the most challenging and important aspect of teaching. Developing engaging content represents one of the integral elements that keeps students involved and motivated in relation to academic pursuit. As such, how content, particularly sensitive material, is presented to students strongly impacts their academic success and satisfaction. In this study we found that student participants felt strongly in terms of how content delivered in the classroom can affect their attendance of a course. For instance, some students expressed that seeing traumatic content or discussing traumatic issues as being important in relation to better understanding that subject matter when it comes to career choices. As explained by Participant I:

“Personally, I never leave the lecture even though they show something that I don't want to see. I never leave because when I think of all the courses that I took, it was something to do with my career. I was so determined to pursue this career.” (Participant I, Postgraduate Student)

Other student participants described fear of being ‘left out’ especially given the notion or belief that university is a place where you make a lot of friends in the classroom, and that this can become difficult when you are talking about complex and sensitive issues (such as colonialism) which may result in a conflict of opinions. As explained by participant O:

“It kind of stopped me wanting to come to the class, because I just felt like I couldn’t. Like I had opinions and ideas, but I just didn’t really feel like I could express them because I was worried about either not really being understood or like contradicting other people and then making them feel guilty and making me feel more different.” (Participant O, Undergraduate Student)

Also, the use of disparaging words by lecturers such as ‘others’ was found to affect attendance. As one student noted:

“But there still can be a little bit of a divide that gets a little bit scary, and I think my attendance dropped a little bit because I kept hearing the word ‘others’ a few times and I was like well, what am I doing here if it’s like I’m not included in the conversation.” (Participant C, Undergraduate Student)

Access To support systems for dealing with trauma-related content

Exposure to trauma should not be a barrier to students participating in education that includes trauma-related material (Cless and Nelson Goff, 2017). Educators should therefore be aware of protective and supportive systems that may mitigate risk of reactivity after exposure to trauma has occurred. When discussing access to support systems for assisting with traumatic material delivered in class, students described several competencies and inadequacies in relation to existing systems. Some students felt that it was possible to build supportive relationships with educators and that these relationships provided psychological safety:

“It’s really nice when you build a relationship with the lecturer because it helps a lot more to deal with the bad things because then you can talk to the lecturer a bit more privately about everything and again it humanizes it [lecture content].” (Participant C, Undergraduate Student)

While the aspect of a dyadic relationship between the student and the educator was suggested to provide a positive support system, it was also mentioned that there was an inadequacy in systems to support the needs of marginalized students:

“I was thinking something possibly like peer support groups for marginalized people in the class, where you can talk about how the lecture went or how the content was and that you feel supported because you know, these are people who “understand,” and you won’t have to fight to be heard over everyone else.” (Participant O, Undergraduate Student)

Some students recognized cultural barriers in relation to expressing the need for assistance and subsequent access to the necessary support, as stated by participant I:

“I didn’t personally seek support, maybe it’s a cultural thing. We don’t read something as an issue in our culture, in our society we are not taught like that. So, I mean, let’s say Japanese people we don’t really raise issues in the class.” (Participant I, Postgraduate Student)

The knowledge shared by educators

Educator interviews consisted of fifteen questions that addressed the educator’s experiences and perceptions in relation to trauma-informed pedagogy. We began with asking what is currently understood and the effectiveness of trauma-informed pedagogy.

Perceptions of trauma-informed pedagogy

What is trauma-informed pedagogy and is it effective?

As with Universal Design for Learning, trauma-informed pedagogy focuses on supporting the learning needs of students in the classroom (CAST, 2018). Marquart and Báez emphasize that trauma-informed pedagogy focuses on addressing barriers resulting from the impacts of traumatic human experiences to create classroom communities that promote student well-being and learning (Marquart and Báez, 2021). Trauma-informed pedagogy, therefore, represents a key element of fostering an equitable classroom. Echoing this perspective, one educator explained:

“It's about putting the students in control and ways of dealing with what they are feeling and giving them access to potential sources of support that could improve their engagement but also improve their well-being. It’s about also generally respecting the values and the voice of the students, making them feel empowered and understanding their experience.” (Participant F, Senior Clinical Lecturer)

When describing whether trauma-informed pedagogy was effective in higher education, educators often spoke of its effectiveness but that it ‘lagged’ in comparison to what has been established in primary and secondary school education. One participant explained that:

“Theoretically speaking, of course it’s effective. It’s hard to answer the question with respect to what the evidence in higher education is because we haven’t been doing this for long. Trauma-informed teaching is not something new but higher education is behind.” (Participant D, Assistant Professor)

Other educators highlighted that for effective trauma-informed teaching to take place in the higher education setting there needs to be more funding. As one educator opined:

“Becoming trauma informed requires research, it requires training, it requires funding and so that has not been available. As we start to see more funding becoming available, we start to see things develop in the domain.” (Participant H, Associate Professor)

On appreciating the value of trauma-informed teaching

As the concept of trauma-informed teaching continues to evolve, the key challenge remains of how educators can best support students and each other (e.g., peer support and supervision) in communicating and discussing difficult material. Therefore, to be trauma-informed, educators must have enough knowledge about how trauma affects their students. In this context, a number of educators emphasized the value of trauma-informed teaching particularly in relation to the well-being of the educator and its subsequent impact on the student. For instance, one educator explained how deficiencies in self-regulation can be picked up by students and affect the learning process:

“So, if I, the teacher am not aware of how I can regulate my nervous system, what triggers me, if I am not well, how am I going to teach my students? And as you know we co-regulate and so if I walk into a space and you’re my professor and you’re having a bad day I can feel it.” (Participant D, Assistant Professor)

Another educator described the significance of trauma-informed teaching in terms of the dyadic interaction between educator and student in relation to self-care as follows:

“It's not enough to just tell students that you need to take care of yourself, but there are ways we can build in that self-care. And probably tracing my own well-being so that I can model self-care and I can help the students to ‘regulate’ in ways that are respectful and within my scope of practice are important.” (Participant L, Associate Professor)

Gauging student reactivity to traumatic material

Educators often spoke in relation to personal knowledge and experience as a means of explaining how exposure to distressing material in the class can impact the level of trauma-related dissociation or reactivity that may occur among students. As one Professor stated:

“Because people pathologize trauma and see dissociation as protection, how people frame and understand it [trauma] and teach it to students so that they can also know that this might be what they notice is happening to them is important. This aspect is of particular significance in terms of the teacher’s experience and in understanding the nuances of what happens when trauma gets activated in students.” (Participant N, Clinical Professor)

Defining successful teaching in higher education

When describing educational effectiveness and successful teaching in relation to trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education, educators emphasized several factors ranging from whether the students had a deepened understanding of the topic at hand (as measured through coursework and practical performance) to class attendance and participation. As one educator explained:

“So, the participation is one thing and the second is engagement with the key concepts of the module. If students feel confident and feel reassured and they engage with the content, I will find the module a success. Also ensuring that the students have not been affected by the material in a way that stops them from being a student, and from attending, from talking to the class, from writing good essays and so on. Now another point of success will be that you don't traumatize students.” (Participant B, Senior Lecturer)

Other educators emphasized the significance of feedback and check-ins with students as integral elements of successful teaching. In one educator’s words:

“I’m doing those check-ins, not just at the end of the semester. Doing check-ins weekly, biweekly, during the semester, during conversations to see where people are at and if there is anything we need to do so that it is not real quiet in the classroom again next week because people don’t want to talk about that material again. Instead of being frustrated with students when they are resisting things, we are trying to understand ‘it’.” (Participant H, Associate Professor)

Creating a safe learning environment in higher education

For the student who has experienced trauma, the physical boundaries of where university spaces end, and how these boundaries are staffed to encourage a nurturing environment to help manage emotions as well as promoting connection, resilience, safety and empathy are integral. In this context, students need to feel that the necessary resources are accessible to them should they be required. For instance, by signposting students to university student support and well-being services as necessary. As one educator explained:

“The other thing I do is I remind people of sources of emotional support and other kinds of important people. Again, this is covered all in the initial contact. So, of course the counseling services and there are people at times that are concerned about finances and stuff like that. So, making sure that they are reminded that there are resources and staff available and how quickly they can access them.” (Participant F, Senior Clinical Lecturer)

Some educators recognized the need for screening students (or prerequisites) as a safety precaution prior to enrolling them in classes that would expose them to content that may risk re-traumatisation. One educator made the following comment:

“Understanding why somebody takes this module. Because some people are not necessarily ready or fully equipped to do that. For instance, if the student said they were a survivor of the Manchester arena attack it might not be a good idea for them to volunteer on a project dealing with this kind of material. So, is there some kind of screening that needs to happen not in order to exclude people from taking the module but understanding the motivations and getting the kind of support they might need. And in an extreme case refusing access to the module if this is not good for their well-being.” (Participant B, Senior Lecturer)

Other educators spoke about the need to support the development of resilience and the student’s ability to engage with difficult material and experiences. As Participant N emphasized:

“Preparing them [in class] to be resilient once they get in the early phases of training and before they go out into their clinical placements and to be safe and vulnerable because that is what's expected at this level of affective reflection without tipping them too far.” (Participant N, Clinical Professor)

Adequate training and support in terms of trauma-informed education

The significance of providing training for educators at the university level so that the students – particularly, marginalized and vulnerable students – who have experienced trauma receive the necessary support to thrive cannot be overstated. Unfortunately, training in relation to trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education remains overlooked as observed by one educator:

“I’m always going to say not enough training takes place for multiple reasons. Number one, our understanding of trauma is still changing, and I follow the science. Number two, science is important and also people’s voices are important, and we haven’t really had conversations about how trauma shows up in higher education. Also, how much is in higher education for marginalized students and how does intergenerational trauma show up.” (Participant D, Assistant Professor)

The need for a standardized means of delivering trauma-informed practice within training at the university level was also highlighted as one interviewee explained:

“I think there probably needs to be some kind of embedding of trauma-informed practice within training in universities. I definitely think that should be the case. Well, it definitely does not exist in a standardized way.” (Participant J, Senior Lecturer)

Educators also spoke of the significance of monitoring and supporting one another by teaching in pairs, and of the significance of such an approach particularly to new staff members who would be teaching a module that includes traumatic material. In the words of one educator:

“When teaching a module for the first time, one should ensure the module is closely monitored and that you may even have two members of staff teaching it, rather than one. That would be something especially valuable if you’re a new member of staff and have not taught this form of material before so that you can support each other.” (Participant B, Senior Lecturer)

Developing policy and guidelines in relation to trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education

The trauma-informed framework incorporates the science of early adversity and promotes thriving for individuals, families, communities, and systems. When applied at the policy level, this framework has the potential to create sustainable, scalable change (Bowen and Murshid, 2016). When educators were asked if the institutions at which they teach had some form of policy or guidelines in relation to trauma-informed teaching there was ambiguity and incongruity with a general consensus for the need of clearer policy and guidelines. As one educator explained:

“An explicit kind of policy position or guidelines of looking at what is happening to certain students through the lenses of trauma would be beneficial in the long run.” (Participant F, Senior Clinical Lecturer)

Discussion

This qualitative study is one of very few exploring perceptions and experiences among students and educators in higher education pertaining to teaching of sensitive material (see Cavener and Lonbay, 2022). These findings present important outlooks on student’s and educators’ knowledge and concerns regarding trauma-informed pedagogy.

The results of this study highlight a lack of congruity, training and funding in relation to trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education. In addition, a lack of support for minority students was identified. This is particularly concerning given the evidence suggesting that minority students are disproportionately affected by exposure to adverse childhood experiences, racial trauma, and traumatic stress (Piper et al., 2022). In this section we delve deeper into the four themes that emerged from the data analysis.

Inclusion and delivery of trauma-related content in higher education

The results of our study show that students appreciate the inclusion of trauma-related content in their classes, especially when it aligns with their desired career choice. Perhaps relevant to this aspect is the evidence suggesting that adopting a pedagogical approach that involves a titrated exposure to traumatic material in class can be beneficial in higher educational institutions and in reducing the emotional impact of engaging with trauma-related content in a real-world context (Black, 2008). While the use of trigger warnings in classroom settings remains debatable (Bridgland et al., 2022)—as corroborated by the inconsistency in answers shared by the student interviewees in our study—the significance of age and resilience when confronted with trauma-related material was found to be of importance, with what was interpreted to be better coping strategies among more mature students. In this regard, McLafferty and colleagues draw attention to the role of age as a key factor in fostering resilience in an academic setting (McLafferty et al., 2012). Culture was also found to be an integral factor in the way students engage with traumatic content in the classroom, consistent with the notion of “cultural intelligence” and culture-specific teaching (Hunter, 2022). Importantly, some students spoke to the significance of traumatic material delivered in class as a means of better understanding and bridging personal relationships (e.g., painful memories) in terms of intergenerational trauma, an aspect that closely aligns with work published in relation to the educational journey to higher education among First Nations people in Australia (Gaywish and Mordoch, 2018).

Effects of trauma-related content on class attendance

Students discussed how content delivered in the classroom affected their attendance of the Emergency Humanitarian Assistance course. Specifically, some ethnic minority students spoke about their fear and/or stress of feeling “left out” due to voicing up their personal impressions about sensitive issues (e.g., colonialism) and the potential conflict of opinions that may ensue among peers in the classroom. The aspect of “othering” was also recounted as a source of stress among marginalized students, consistent with recent work by Olaniyan (2021). Therefore, directing students’ attitudes to be more appreciative and empathetic of differing views and experiences being shared by their peers while avoiding othering and/or seeing distress as a normative reaction represent key strategies in terms of developing effective trauma-informed teaching (Carello and Butler, 2015). In this context, attention has been focused on the significance of group dynamics and styles of presentation in classroom settings in higher education institutions (Cunningham, 2004). Notable in this regard is the work by Cunningham which highlights how educator presentation styles can risk devaluing the experience of students who may have similar life experiences where trauma-materials are shared in an emotionless and/or detached way (Cunningham, 2004).

Access to support systems for dealing with trauma-related content

While our study suggests that mental health and well-being support systems are available in higher education for students who may be facing academic challenges such as dealing with trauma-related content in class as well as personal and emotional problems, this was not always the case, particularly for marginalized and ethnic minority students. For instance, some students mentioned the lack of peer-support systems and/or networks for marginalized and ethnic minority students made them go through stressful experiences. Similar results were found in the study by Olaniyan that reported racial and ethnic minority students from two UK universities had to navigate a “minefield” of racial microaggressions and othering – aspects that are likely to have influenced both the student’s mental health and their help-seeking attitudes (Olaniyan, 2021).

Perceptions on trauma-informed education

We found that perceptions among educators on trauma-informed pedagogy were generally positive, particularly as a strategy for fostering an equitable classroom in higher education. Despite acknowledging the importance and effectiveness of trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education, several educators emphasized that as a teaching approach it continues to fall short in contrast to what has been achieved in primary and secondary school education. To this end, educators spoke of the need for further funding in the domain that would enable more research and training in relation to trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education, that in turn, would help instill policy guidelines and frameworks for better training of staff at this level of academic pursuit.

A number of educators that were interviewed in our study spoke in relation to creating a safe learning space (or sanctuary) for the students, an element consistent with one of Carello and Butler’s 5 principles of trauma-informed care in classroom settings (Carello and Butler, 2015). The element of ensuring safety among students in higher education was encapsulated in a recent study by Cavener and Lonbay that explored educator and student experiences of teaching and learning traumatic material in two UK universities, and found that educators actively took steps to create a safe environment for their students on social work programs (Cavener and Lonbay, 2022). Like the study by Cavener and Lonbay, our study was conducted in a UK setting and focused on undergraduate and postgraduate experiences in relation to trauma-informed learning. However, while Cavener and Lonbay’s work specifically targeted social work educators and students, our research involved students from the humanities and educators teaching in the humanities and social sciences—recruited from 5 different higher education institutions situated in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. It follows that the increased diversity among educators in our study is likely to have provided for a broader and more encompassing set of information, particularly in relation to perception of trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education.

The aspect of self-care for the educator and student was also discussed at length by educators. This often took the form of check-ins, with educators checking in on one another but also whereby educators checked in with students throughout the course, so as to ensure that students had ‘choice’ in how they engage with taught material (i.e., reactivity to traumatic material). Beyond, the self-care aspect, these check-ins provide a measure for the educators to gauge how successful the course is. Particularly in understanding as to whether students have been affected by the material presented in class and as to whether this stops them from attending the course and if it impacts academic performance.

Future research directions

Future research that includes different higher education courses (from different faculties) that incorporate sensitive content in the classroom setting will help further develop and understand the results of the present study. In addition, a follow-up study that tracks study participants in terms of their career decisions and as to whether they have completed specific degree programs (e.g., in the humanities and social sciences) would enhance our knowledge of the value of course content that includes traumatic material in learning and teaching in higher education. Furthermore, trauma-informed research that reflects student diversity (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, religion, geographical representation) in the higher education setting will be important. Finally, because we understand trauma to be culturally informed, comparing a course/program taught in the United Kingdom with a similar course/program taught in a different culture (e.g., Hong Kong, New Zealand, and South Africa) may provide additional insights into this important consideration in the field of trauma.

Limitations

Most of the students interviewed in this study were from Western countries (United Kingdom and United States). Similarly, all the educators who participated in the study were based at Institutions in Western countries (United Kingdom, United States and Australia). The study only included students from a specific Institute of the University of Manchester (i.e., the HCRI) who had previously undertaken a module on Emergency Humanitarian Assistance. Therefore, findings are not generalisable across all higher-education institutions. Certainly, the study would have been strengthened with data from more students and educators (that included a broader spectrum of demographics). Nonetheless, the data generated here offers a window into the subjective perceptions of students and educators in relation to trauma-informed pedagogy.

A conceptual framework for trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education

Steps to becoming trauma-informed can be conceptualized as a progression from trauma-aware, trauma-sensitive, trauma-responsive, then trauma-informed (Missouri Model, 2014). It is also important that trauma-informed teaching practices overlap with existing and established educational approaches, including critical, feminist, anti-racist pedagogies and Universal Design for Learning.

Guided by these principles and the effects of traumatic stress on learning, below we provide a framework of recommendations to bolster trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education:

1) Develop a trauma-informed institutional framework. It is important for higher education institutions to understand what trauma is, how it shows up, and what exacerbate or ameliorate its impacts before developing an equity-minded and culturally-grounded trauma-informed action plan. To this end, more funding is required for research in this domain.

2) Uphold learning as the primary goal and student safety as a necessary condition. Invite but do not require students to share how they are feeling at key junctures (even when the content itself is unlikely to be upsetting) (Carello and Butler, 2014).

3) Institutions should be open and transparent about their actions and decisions, and should hold themselves accountable for any harm or wrongdoing that occurs.

4) Cultivate “spaces” and opportunities in the classroom where students can co-create and focus on co-being and well-being.

5) Focus on developing peer-support systems for marginalized students as an approach to address potential psychological distress related to sensitive material delivered within the classroom.

6) Empower students to make the best decisions they can for themselves and their learning by building in flexibility and a contained set of choices where possible (e.g., mode of participation) (Carello and Butler, 2015).

7) Build and maintain trust with students and the people that the university serves by being responsive, transparent, and accountable. This can involve engaging with stakeholders and community members and working to address their concerns and needs.

8) Spell out the “why” of tasks and assignments along with the “what” to help improve the clarity and transparency of the assignments and exercises (Imad, 2020).

9) Take responsibility for the long history of ignoring the fact that many of the students who came to university to learn are already suffering from the impact of generational and intergenerational trauma and adversities.

10) Create a culture that values and respects the dignity and rights of all individuals, and that genuinely promotes radical inclusivity and belonging.

11) Reduce and focus information and create predictable structures to help manage information overload, decrease uncertainty, and improve cognitive functioning (Imad, 2020), through resilience interventions such as playful resilience (Ang et al., 2022; Heljakka, 2023).

12) Create and reinforce communication techniques that promote self-regulation, like de-escalation techniques, psychological first aid, and nonviolent communication (Imad, 2020).

13) Demonstrate unconditional positive regard. This is important for helping those students who have experienced trauma restore their sense of self (Wolpow et al., 2009).

14) Avoid the romanticization of trauma narratives or implication that trauma is desirable. This can be dysregulating for those with trauma histories or invite trauma disclosures without providing an appropriate environment or adequate support (Carello and Butler, 2014).

Conclusion

The current study provides a fresh perspective on a subject that remains under-researched: trauma-informed pedagogy and its impact on students in higher education. The findings presented herein are subjective and based on student and educator perceptions. Notably, the data support Janice Carello and Lisa Butler’s principles of teaching trauma without traumatizing in higher education, whereby educators can help students recognize their strengths and build resilience (Carello and Butler, 2015). It is believed that the principles of titrated exposure, self-care and peer-support (particularly among minority and marginalized groups) would help prevent students becoming overwhelmed and remain able to learn in a course or degree with exposure to traumatic content. The cost of ignoring these principles may be that students, who are trying to learn will feel overwhelmed during the class (Black, 2006). Choosing to ignore these principles may represent a form of institutional betrayal and academic trauma to students in higher education (Imad et al., 2023), and as such being trauma-informed represents a moral duty and obligation for educators.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

BB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MI: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. BB is recipient of a SALC Staff Development Fund Award.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the participation of the students and educators who gave their precious time to share their personal experience and for kindly granting us permission to use excerpts from their interview. We also thank Jessica Hawkins and Darren Walter of the HCRI who provided invaluable insight and comments in relation to an earlier version of the manuscript. Finally, we extend our gratitude to Stephanie Rinaldi (HCRI) for providing invaluable administrative assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1256996/full#supplementary-material

References

Ang, W. H. D., Lau, S. T., Cheng, L. J., Chew, H. S. J., Tan, J. H., Shorey, S., et al. (2022). Effectiveness of resilience interventions for higher education students: a meta-analysis and metaregression. J. Educ. Psychol. 114, 1670–1694. doi: 10.1037/edu0000719

Agorastos, A., Pervanidou, P., Chrousos, G. P., and Baker, D. G. (2019). Developmental trajectories of early life stress and trauma: a narrative review on neurobiological aspects beyond stress system dysregulation. Front. Psych. 10:118. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00118

Anzaldúa, J. M. (2022). “Internationalizing trauma-informed perspectives to address student trauma in post-pandemic higher education” in COVID-19 and higher education in the global context: Exploring contemporary issues and challenges. eds. R. Ammigan, R. Y. Chan, and K. Bista, (STAR Scholars), 154–171.

Becker-Blease, K. A. (2017). As the world becomes trauma–informed, work to do. J Trauma Dissociation 18, 131–138. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1253401

Black, T. G. (2008). Teaching trauma without traumatizing: a pilot study of a graduate counseling psychology cohort. Traumatology 14, 40–50. doi: 10.1177/1534765608320337

Black, T. G. (2006). Teaching trauma without traumatizing: principles of trauma treatment in the training of graduate counselors. Traumatology 12, 266–271. doi: 10.1177/1534765606297816

Bloom, S. L. (2010). “Organizational stress and trauma-informed services” in A public health perspective of Women’s mental health. eds. B. L. Levin and M. A. Becker (New York, NY: Springer), 295–312.

Bowen, E. A., and Murshid, N. S. (2016). Trauma-informed social policy. A conceptual framework for policy analysis and advocacy. Am. J. Public Health 106, 223–229. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302970

Bridgland, V., Jones, P. J., and Bellet, B. W. (2022). A meta-analysis of the effects of trigger warnings, content warnings, and content notes. Clin. Psychol. Sci. doi: 10.1177/21677026231186625

Bryce, I., Pye, D., Beccaria, G., McIlveen, P., and Du Preez, J. (2023). A systematic literature review of the career choice of helping professionals who have experienced cumulative harm as a result of adverse childhood experiences. Trauma Violence Abuse 24, 72–85. doi: 10.1177/15248380211016016

Butler, L. D., Maguin, E., and Carello, J. (2017). Retraumatization mediates the effecst of adverse childhood experiences on clinical training-related secondary traumatic stress symptoms. J. Trauma Dissociation 19, 25–38. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1304488

Carello, J., and Butler, L. D. (2014). Potentially perilous pedagogies: teaching trauma is not the same as trauma-informed teaching. J. Trauma Dissociation 15, 153–168. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2014.867571

Carello, J., and Butler, L. D. (2015). Practicing what we teach: trauma-informed educational practice. J. Teach. Soc. Work. 35, 262–278. doi: 10.1080/08841233.2015.1030059

Cavener, J., and Lonbay, S. (2022). Enhancing ‘best practice’ in trauma-informed social work education: insights from a study exploring educator and student experiences. Soc. Work. Educ. 1-22, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2022.2091128

Chan, K. D., Humphreys, L., Mey, A., Holland, C., Wu, C., and Rogers, G. D. (2020). Beyond communication training: the MaRIS model for developing medical students’ human capabilities and personal resilience. Med. Teach. 42, 187–195. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1670340

Cless, J. D., and Nelson Goff, B. S. (2017). Teaching trauma: a Model for introducing traumatic materials in the classroom. Adv. Soc. Work 18, 25–38. doi: 10.18060/21177

Crabtree, B., and Miller, W. (1999). “A template approach to text analysis: developing and using code books” in Doing qualitative research. eds. B. Crabtree and W. Miller (London: Sage), 93–109.

Creswell, J. W., and Guetterman, T. C. (2019). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. 6th. Pearson London

Cunningham, M. (2004). Teaching social workers about trauma: reducing the risks of vicarious trauima in the classroom. J. Soc. Work. Educ. 40, 305–317. doi: 10.1080/10437797.2004.10778495

Frazier, P., Anders, S., Perera, S., Tomich, P., Tennen, H., Park, C., et al. (2009). Traumatic events among undergraduate students: prevalence and associated symptoms. J. Couns. Psychol. 56, 450–460. doi: 10.1037/a0016412

Gaywish, R., and Mordoch, E. (2018). Situating intergenerational trauma in the educational journey. In Education 24, 3–23. doi: 10.37119/ojs2018.v24i2.386

Guzmán-Rea, J. (2021). “Experiencing Compassion Fatigue and Utilizing Trauma-Informed Pedagogy while Teaching Graduate Students Online,” in Tackling online education: implications of responses to covid-19 in higher education globally. eds. H. Han, J. H. Williams, and S. Cui, (Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 25–34.

Heljakka, K. (2023). Building playful resilience in higher education: learning by doing and doing by playing. Front. Educ. 8:1071552. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1071552

Hunter, J. J. (2022). Clinician’s voice: trauma-informed practices in higher education. New Dir. Stud. Serv. 2022, 27–38. doi: 10.1002/ss.20412

Imad, M., Bitanihirwe, B., and Barranco, K. (2023). Transforming higher education: Building trauma-informed communities for healing and intergenerational wellbeing. Wiley. Hoboken, NJ

Imad, M. (2022). “Our brains, emotions, and learning: eight principles of trauma-informed teaching” in Trauma-informed pedagogies. eds. P. Thompson and J. Carello (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 35–46.

Imad, M. (2021). Transcending adversity: trauma-informed educational development. To Imp. Academy J. Educat. Develop. 39, 1–23. doi: 10.3998/tia.17063888.0039.301

Imad, M. (2020). Leveraging the neuroscience of now. Inside higher. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2020/06/03/seven-recommendations-helping-students-thrive-times-trauma (Accessed March 29, 2023).

Jolly, R. (2011). Witnessing embodiment. Aust. Fem. Stud. 26, 297–317. doi: 10.1080/08164649.2011.606604

Kennedy, K. M., and Scriver, S. (2016). Recommendations for teaching upon sensitive topics in forensic and legal medicine in the context of medical education pedagogy. J. Forensic Legal Med. 44, 192–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2016.10.021

Kostouros, P. (2008). Using traumatic material in teaching. Tranform. Dialogues Teach. Learn. J. 2, 1–7.

Lecy, N., and Osteen, P. (2022). The effects of childhood trauma on college completion. Res. High. Educ. 63, 1058–1072. doi: 10.1007/s11162-022-09677-9

Marquart, M., and Báez, J. (2021). Recommitting to trauma-informed teaching principles to support student learning: an example of a transformation in response to the coronavirus pandemic. J. Transform. Educ. 8, 63–74.

McLafferty, M., Mallett, J., and McCaulet, V. (2012). Coping at university: the role of resilience, emotional intelligence, age and gender. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1, 1–6.

Missouri Model (2014). A developmental framework for trauma informed approaches, MO Dept. of mental health and partners. Available at: https://dmh.mo.gov/media/pdf/missouri-model-developmental-framework-trauma-informed-approaches (Accessed March 29, 2023).

Morton, B. M., and Berardi, A. A. (2018). Trauma-informed school programming: applications for mental health professionals and educator partnerships. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 11, 487–493. doi: 10.1007/s40653-017-0160-1

Naderifar, M., Goli, H., and Ghaljaie, F. (2017). Snowball sampling: a purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Stride. Dev. Med. Educ. 14:e67670. doi: 10.5812/sdme.67670

Negrete, M. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences of social work students and implications for field specialization and practice. Electronic theses, projects, and dissertations. 1033. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1033 (Accessed March 29, 2023).

O’Connor, C., and Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qual Methods 19, 160940691989922–160940691989913. doi: 10.1177/1609406919899220

Olaniyan, F.-V. (2021). Paying the widening participation penalty: racial and ethnic minority students and mental health in British universities. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 21, 761–783. doi: 10.1111/asap.12242

Parker, R., and Hodgson, D. (2020). “One size does not fit all”: engaging students who have experienced trauma. Issues Educ. Res. 30, 245–259.

Piper, K. N., Elder, A., Renfro, T., Iwan, A., Ramirez, M., and Woods-Jaeger, B. (2022). The importance of anti-racism in trauma-informed family engagement. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 49, 125–138. doi: 10.1007/s10488-021-01147-1

Prabhu, S., and Carello, J. (2022). “Utilizing an ecological, trauma-informed, and equity Lens to build an understanding of context and experiences of self-Care in Higher Education” in Trauma-informed pedagogies. eds. P. Thompson and J. Carello (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 187–202.

Read, J. P., Ouimett, O., White, J., Colder, C., and Farrow, S. (2011). Rates of DSM-IV-TR trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among newly college students. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 3, 148–156. doi: 10.1037/a0021260

Rossi, R., Jannini, T. B., Socci, V., Pacitti, F., and Di Lorenzo, G. (2021). Stressful life events and resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown measures in Italy: association with mental health outcomes. Front. Psych. 12:635832. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.635832

Scannell, C. (2021). Intentional teaching: building resiliency and trauma-sensitive cultures in schools. Intech Open. Available at: https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/intentional-teaching-building-resiliency-and-trauma-sensitive-cultures-in-schools (Accessed March 29, 2023).

Stratford, B., Cook, E., Hanneke, R., Katz, E., Seok, E., Steed, H., et al. (2020). A scoping review of school-based efforts to support students who have experienced trauma. Sch. Ment. Heal. 12, 442–477. doi: 10.1007/s12310-020-09368-9

Sweetman, N. (2022). What is a trauma informed classroom? What are the benefits and challenges involved. Front. Educ. 7:914448. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.914448

Thomas, M. S., Crosby, S., and Vanderhaar, J. (2019). Trauma-informed practices in schools across two decades`; an interdisciplinary review of research. Rev. Res. Educ. 43, 422–452. doi: 10.3102/0091732X18821123

Thomas, J. T. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences among MSW students. J. Teach. Soc. Work. 36, 235–255. doi: 10.1080/08841233.2016.1182609

Tsantefski, M., Rhodes, J., Johns, L., Stevens, F., Munro, J., Humphreys, L., et al. (2020). Trauma-informed tertiary learning and teaching practice framework. Brisbane: Griffith University

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Available at: https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4884.pdf

Voith, L. A., Hamler, T., Francis, M. W., Lee, H., and Korsch-Williams, A. (2020). Using a trauma-informed, socially just research framework with marginalized populations: practices and barriers to implementation. Soc. Work. Res. 44, 169–181. doi: 10.1093/swr/svaa013

Wolpow, R., Johnson, M. M., Hertel, R., and Kincaid, S. O. (2009). The heart of learning and teaching: Compassion, resiliency, and academic success. Available at: https://rems.ed.gov/docs/ospi_theheartoflearningandteaching.pdf (Accessed March 29, 2023).

Keywords: higher education, mental health, resilience, self-regulation, trauma-informed pedagogy

Citation: Bitanihirwe B and Imad M (2023) Gauging trauma-informed pedagogy in higher education: a UK case study. Front. Educ. 8:1256996. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1256996

Edited by:

Marta Moskal, University of Glasgow, United KingdomReviewed by:

India Bryce, University of Southern Queensland, AustraliaJeanie Tietjen, Massachusetts Bay Community College, United States

Copyright © 2023 Bitanihirwe and Imad. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Byron Bitanihirwe, Ynlyb24uYml0YW5paGlyd2VAbWFuY2hlc3Rlci5hYy51aw==

Byron Bitanihirwe

Byron Bitanihirwe Mays Imad

Mays Imad