- 1Moray House School of Education and Sport, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 2Scottish Book Trust, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Psychology, University of Dundee, Dundee, United Kingdom

Research has consistently demonstrated declines in reading motivation and engagement from childhood to adolescence, with current levels of reading enjoyment and engagement among adolescents at an all-time low. This has led to increased interest in approaches for supporting adolescents’ reading motivation. To date, efforts to support adolescent reading motivation have utilized a variety of approaches, yet there is currently no review which synthesizes existing research in this area and provides recommendations for future research and practice. Drawing upon both narrative and scoping review principles, this review synthesizes 38 peer-reviewed articles and research reports which have evaluated approaches for improving adolescents’ (12–16 years old) reading motivation. The article outlines the breadth and scope of approaches which have been used previously, categorized into five types: (1) reading and literacy skills programs; (2) whole-school reading culture; (3) book clubs; (4) technology-supported interventions; and (5) performance and theater. The review also identifies gaps and issues relating to the current body of research and proposes priorities for future work in this area. Together, the findings and recommendations address calls to dedicate renewed and sustained attention to supporting adolescents’ reading motivation and engagement and provide a point of reference for researchers and education practitioners seeking to select, develop, and implement strategies for supporting adolescents’ reading motivation in the future.

1. Introduction

There is growing interest in the concept of motivation in reading research, due to increased recognition of its role in reading achievement (e.g., Toste et al., 2020) and amount and breadth of reading (e.g., Miyamoto et al., 2019). However, adolescence has been consistently associated with declines in reading motivation and in related constructs such as enjoyment (Clark and Douglas, 2011; Cole et al., 2022), attitude (McKenna et al., 2012; Allred and Cena, 2020), and frequency (Twenge et al., 2019) for both academic and recreational reading (Clark, 2019; Clark and Teravainen-Goff, 2020). Indeed, in the last 50 years, overall time spent reading for pleasure has declined amongst adolescents (Twenge et al., 2019), with fewer adolescents reporting enjoying reading for pleasure in 2022 than in the previous 15 years (Cole et al., 2022).

For researchers, policymakers, and classroom practitioners, knowledge of approaches which can support adolescents’ reading motivation is essential for informing future research priorities and guiding classroom practice. However, to our knowledge, there exists no review which synthesizes the diverse ways in which reading motivation support for adolescents has been implemented and evaluated. This is especially challenging given that reading motivation is multidimensional and complex (Schiefele et al., 2012; Toste et al., 2020) and cognate concepts such as reading interest, self-efficacy, and self-concept are often used interchangeably with reading motivation (Conradi et al., 2014; Jang et al., 2015). The consensus definition of reading motivation proposed by Conradi et al. (2014) conceptualizes it as “the drive to read resulting from a comprehensive set of an individual’s beliefs about, attitudes toward, and goals for reading.” (p. 154), yet the use of conceptually similar terms, which are often ill-defined (Conradi et al., 2014), makes navigating research findings and selecting appropriate strategies to support reading motivation challenging for researchers and educators (Schiefele et al., 2012; Conradi et al., 2014; Jang et al., 2015; Murnan et al., 2023). Alongside this, there is also a lack of consensus regarding an overarching theory or model to underpin reading motivation research (Conradi et al., 2014; McTigue et al., 2019), with different schools of thought advocating for different theoretical frameworks (e.g., Self-Determination Theory; Deci and Ryan, 1980; Expectancy Value Theory, Eccles, 1983). In addition, experimental research evaluating the effectiveness of different types of support for adolescents’ reading motivation has used a variety of different methodological approaches (e.g., randomized controlled trials, qualitative interviews, ethnographic research). While different methodologies are appropriate for different types of exploration, such variety makes it difficult for researchers and practitioners to understand the quality of approaches that might be available.

Therefore, the first aim of this review was to synthesize previous research which has evaluated different types of literacy or reading approaches to sustain and/or improve adolescents’ (12-16-years-old) reading motivation. Given that a wide variety of approaches have been applied and evaluated in previous studies (Pelletier et al., 2022), a combination of scoping review (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005) and narrative review (NR; Baethge et al., 2019) principles were applied in order to attend to the breadth of literature available. Scoping reviews enable examination of the extent, range, and nature of previous research activity, summarization of their findings, and the identification of gaps, issues, and opportunities for future development (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005). NRs are common within medical literature (Bastian et al., 2010; Baethge et al., 2019) and are used to summarize a body of research in a way which allows greater flexibility in terms of selection criteria, thematic inclusion, and exploration of specific research questions than a systematic review (Baethge et al., 2019). NRs can be used to “bring practitioners up to date” by “pull [ing] many pieces of information together into a readable format” (Green et al., 2006, p. 103). There are also some examples of NRs used within educational research (e.g., Zucker et al., 2009; Jerzembek and Murphy, 2013; Erbeli and Rice, 2021) which have highlighted gaps and future priority areas.

The primary aims of this review are (1) to summarize the breadth and type of literacy supports which have been used specifically with adolescents (12–16-years-old) and which explicitly measure reading motivation as an outcome; and (2) to identify gaps in existing knowledge and provide suggestions for future research priorities.

2. Methods

This review combines elements of both a scoping review (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005) and a narrative review (Baethge et al., 2019). We referred to the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA; Baethge et al., 2019) to inform the review process. The SANRA is a simple and brief quality assessment which aims to measure the construct “quality of a narrative review article” (p. 2) on items such as the review’s importance and description of the literature search. Referring to the scale ensured the process adhered to established guidelines for conducting a high-quality review. The research questions which guided the review were: (1) What approaches for supporting adolescents’ reading motivation have been implemented and evaluated previously? (2) What are the research and practice priorities and recommendations to support adolescents’ reading motivation in the future?

A two-step review process was conducted (see Figure 1). In step 1, we conducted a comprehensive computerized search of three databases relevant to the field of education: SCOPUS, Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC), and What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) using search terms in accordance with the research aims (e.g., “reading,” “motivation,” “support,” “intervention”; see Supplementary material for all search terms).

The initial search yielded a total of 635 peer-reviewed journal articles and research reports (SCOPUS: 487; ERIC: 76; WWC: 72) for primary screening. The first author reviewed the titles and abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined below. During primary screening, 600 publications were excluded. This resulted in a total of 31 original research publications and 4 meta-analyses.

In step 2, the first author reviewed the reference lists of 4 relevant meta-analyses (Lazowski and Hulleman, 2016; Unrau et al., 2017; Okkinga et al., 2018; McBreen and Savage, 2020). A total of 397 citations were reviewed from these reference lists (Lazowski and Hulleman, 2016, p. 171; Unrau et al., 2017, p. 53; Okkinga et al., 2018, p. 101; McBreen and Savage, 2020, p. 72). Primary screening against inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in 394 exclusions; 7 publications were added to those identified during step 1. Across steps 1 and 2, a total of 1,032 texts were retrieved; 38 were selected for inclusion (Figure 1). A detailed explanation of search procedures can be found in the Supplementary material.

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.1.1. Inclusion criteria

• Reading and/or literacy support program or intervention.

• Explicit measurement of reading motivation and/or an associated concept (e.g., reading attitude, value, enjoyment).

• Participants aged 12–16-years-old.

2.1.2. Exclusion criteria

• No specific support program or intervention.

• No explicit measurement of motivation and/or an associated concept.

• Outcome measures related to motivation for other academic subjects (e.g., science) or for learning generally.

• Second language or EFL learners.

• Populations younger than 12-years-old or older than 16-years old (including studies with teachers as participants).

• Publications before 1990.

• Conference abstracts.

For examining and charting the data, key features of included studies were identified and coded accordingly. Codes represented “succinct, shorthand descriptive or interpretive labels for pieces of information that may be of relevance to the research question(s)” (Byrne, 2022, p. 1399) including information about the research context (e.g., location), study aims, underpinning theory, definition of terms, participant information (e.g., N-number, age/grade), study design (e.g., assignment of participants to groups, measurement tools, analysis type), information about the intervention (e.g., duration, key features, theoretical grounding), findings, and additional notes (e.g., generalizability of outcomes). Following the coding stage, the key features of each article were reviewed in order to generate subcategories representing the different types of approaches which are represented in previous research.

3. Findings

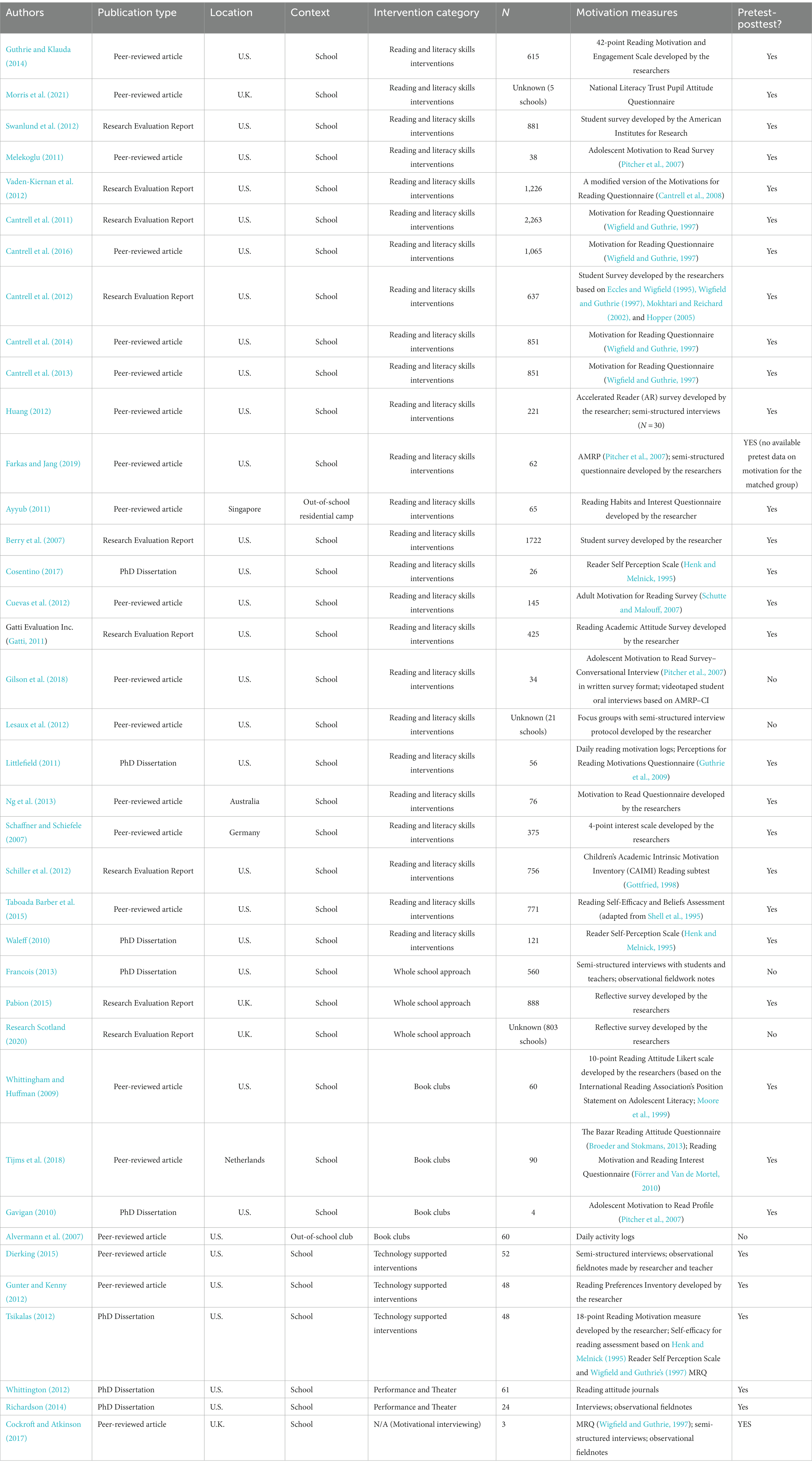

To map the breadth of approaches for supporting adolescents’ reading motivation, approaches were categorized by type. As it is not the role of this type of review to assess the quality of included studies, nor to provide answers to questions about the most appropriate or successful approaches (see Arksey and O'Malley, 2005), organizing the findings in this way aims to enable those who are interested in particular methods to easily locate the information related to these. The following broad types of approach were identified: (1) reading and literacy skills programs; (2) whole-school reading culture; (3) book clubs; (4) technology-supported interventions; and (5) performance and theater (see Table 1). We address each of these approaches in turn. While the aim of categorizing by type is to map the range of approaches in a useful way, it should be noted that some approaches could conceptually span more than one category. Additionally, one study (Cockroft and Atkinson, 2017) used ‘motivational interviewing’, an approach which did not fit into any of the categories above. Readers interested in this approach are directed to the original article. Given the breadth of methodological approaches to evaluation in the studies retrieved, and that it is not necessary with this type of review to critique each study included (Green et al., 2006), the efficacy of each intervention has not been evaluated individually.

3.1. Reading and literacy skills programs

The search revealed reading and literacy skills programs to be the most prominent in terms of approaches which have previously been used to support adolescent reading motivation (N = 24). Previous research has found reading skill to be moderately associated with reading motivation, with evidence for a reciprocal relationship leading from earlier reading skill to later motivation (Toste et al., 2020). Furthermore, the primary focus in much reading research, policy, and practice is on supporting students’ reading and literacy skills (Aukerman and Chambers Schuldt, 2021), meaning that it is perhaps unsurprising that approaches which support reading and literacy skills alongside motivation were most prevalent in the current review.

One of the most established and well evaluated skills interventions which has a specific focus on motivation is Concept Orientated Reading Instruction (CORI; Wigfield et al., 2014). Within the CORI framework, reading motivation is conceptualized as a key component of reading engagement, which is thought of as “the interplay of motivation, conceptual knowledge, strategies, and social interaction during literacy activities” (Wigfield, 2004, p. ix). In its development, the program merged theory related to reading comprehension and motivation (intrinsic motivation, perceived autonomy, self-efficacy, collaboration, and mastery goal pursuit), with experience from teachers, reading specialists and educational psychologists. Key motivational features include fostering interest, encouraging student choice and curiosity, ensuring success, providing a wide variety of interesting texts and materials, providing opportunities for hands-on activities, encouraging students to strive toward knowledge goals, and enabling students to collaborate (Wigfield et al., 2014). CORI has been evaluated extensively in the U.S., usually with a focus on its impact on skills development (not all of these are included in this review, given that studies not explicitly measuring reading motivation were excluded at screening). Regarding studies which did measure motivation and motivation-related outcomes, one (Guthrie and Klauda, 2014) found U.S. 7th Grade (12–13-years-old) students receiving the CORI curriculum to show greater increases in intrinsic motivation, reading value, perceived competence, and positive engagement than those receiving traditional instruction.

A U.K.-based skills-focused curriculum intervention, Literacy for Life (LfL), also evaluated the implementation of a multifaceted approach, which offered access to reading, writing, and oral skills resources alongside professional development for teachers. Notably, LfL schools had considerable freedom around which elements they included in their programs. Morris et al. (2021) adopted a quasi-experimental approach to compare outcomes in five secondary schools using the LfL program with “the strongest comparators available” (p. 7) (details of the control interventions were not provided). Contrary to expectation, the authors found reading enjoyment to decline slightly among participants across the three-year intervention. To explain this, they note that the program contained a large variety of components, each of which were assumed to be beneficial (not always with supporting evidence), which schools were able to adapt however they wished. This led to large variation in implementation which was challenging to evaluate. There was also no clear theory of change for the program. The authors suggest that “clearer, more focused (and possibly fewer) aims and intended outcomes” (p. 13), as well as clarity on the theoretical basis supporting specific elements would have been of benefit to the program.

Another widely used skills-focused approach is Accelerated Reader (Renaissance Learning; Siddiqui et al., 2016). Accelerated Reader (AR) utilizes Reading Practice Quizzes (RPQs) to assess text comprehension, to encourage reading practice, foster text engagement, and develop reading skills. There is a considerable research base evaluating AR (Siddiqui et al., 2016), yet much of the research focuses primarily on increasing skills-based outcomes such as text comprehension and reading fluency (What Works Clearing House, 2008), particularly in younger age groups (e.g., Nunnery et al., 2006). However, some research has explored the efficacy of the program for supporting motivational outcomes in adolescents. In the U.S., Huang (2012) reports that for a sample of 6th – 8th Grade (11–14-years-old) students (N = 221), the AR program contributed toward feelings of being pressured to read. Indeed, in other evaluations of AR, feelings of being “forced to read” were associated with self-reported decreases in motivation to do so (Thompson et al., 2008, p. 555). Huang (2012) also reports that AR contributed toward feelings of competition between peers to get the highest RPQ scores. The authors note that the AR approach may support extrinsic (external) motivation to the detriment of intrinsic (internal) motivation, a position supported by previous evaluations on the program (e.g., Biggers, 2001; Thompson et al., 2008). As intrinsic reading motivation has been associated with more positive effects on reading amount and achievement than has extrinsic motivation (e.g., Schiefele et al., 2012; Wigfield et al., 2016), the small amount of peer-reviewed research investigating AR for supporting adolescent reading motivation can provide useful insights into its potential limitations.

The approaches outlined thus far represent programs which have been applied across whole school and/or year group populations. However, some skills-based interventions have provided targeted interventions for specific groups. For example, The Learning Strategies Curriculum (LSC) was implemented specifically for students with reading scores below the expected standard for their age. The LSC is grounded in theory related to self-regulated learning and generalization (Schumaker and Deshler, 2006), and represents a targeted intervention specifically for ‘struggling’ readers. The literature search retrieved several reports examining the effectiveness of the LSC for improving reading motivation as one of its outcomes (alongside reading skill and strategy use) in U.S. adolescent readers (Grades 6 and 9) (Cantrell et al., 2011, 2013, 2014, 2016). Significant increases in self-reported motivation were reported for 6th (11–12-years-old) and 9th (14–15-years-old) Grade participants (Cantrell et al., 2011). On the selected motivation measures (see Table 1), increases in reading self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation (interest, curiosity, and perceptions of importance), and extrinsic motivation (grades and competition with peers), but not in social motivation, were found for the LSC group (Cantrell et al., 2013). Interestingly, improvements in motivation did not translate into improved reading performance. Evaluation by the same authors of a similar program, the Kentucky Cognitive Literacy Model (Cantrell et al., 2012) reported similar findings – no significant effects on reading achievement despite significant impacts on students’ (14–15-years-old) on reading motivation. The authors suggest that this may be because although the relationship between reading engagement and performance is likely to be reciprocal (e.g., Morgan and Fuchs, 2007; Toste et al., 2020), changes may not occur simultaneously; improvements in performance may take longer to emerge. Another U.S. skills-based program which aimed to support ‘struggling readers’, Voyager Passport Reading Journeys (PRJ), reported differing results: improvements in reading achievement and reading motivation in 6th – 7th Grade students (Vaden-Kiernan et al., 2012). The program featured reading ‘expeditions’ focused on topics related to science and social studies which incorporated support for reading fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Notably, the evaluation also assessed fidelity of implementation and concluded that the program was implemented with medium to high levels of adequacy across the 10 schools in the study.

In sum, reading and literacy skills programs have the potential to support reading motivation alongside skills-based outcomes. Of those eligible for inclusion in this review, positive effects on reading motivation and related outcomes (e.g., engagement, value, interest, curiosity) were identified in CORI (Guthrie and Klauda, 2014), LSC (Cantrell et al., 2012, 2013), and PRJ (Vaden-Kiernan et al., 2012) implementation. However, improvements in reading motivation were not identified following LfL (Morris et al., 2021), and features of AR were identified as being potentially detrimental intrinsic motivation to read (Huang, 2012). This indicates that improvements in reading skills may not necessarily also map onto positive motivation outcomes. More work is needed to establish features of skills-based programs which also support reading motivation.

3.2. Whole school reading culture

The approaches outlined above represent those which have measured reading motivation outcomes from school-or group-wide programs which specifically target reading skills. However, the review also identified serval studies which have implemented or evaluated approaches to supporting a whole school ‘reading culture’ (N = 3). These whole-school approaches aim to create an environment that supports reading motivation across a large student cohort using a wide variety of approaches.

An ethnographic study of one U.S. Secondary school (11–18-years-old), outlined a whole school approach which created a sense of community and individual agency over pupils’ reading habits (Francois, 2013). Situated within a sociocultural perspective and drawing upon theories associated with ‘communities of practice’ (e.g., Wenger et al., 2002), activities which created a “culture of reading” (p. 8) were proposed as the mechanisms supporting students’ reading motivation, engagement, and achievement. Activities included encouraging students to select their own books, form connections with others through reading, recommend books to one another, read in public spaces, and encourage one another to read (both explicitly and through peer modeling). Although acknowledging that it is difficult to form generalizations from single-site case studies, the author suggests that understanding reading as a social practice was key to supporting motivational outcomes and emphasizes the importance of a multidimensional approach to fostering a school-wide motivating reading culture.

Developing a reading culture was also central to the First Minister’s Reading Challenge (FMRC) delivered by Scottish Book Trust and evaluated by Research Scotland (2020). The FMRC program was intended to be inclusive and flexible, working alongside other reading programs taking place both in and out of school to build a school-and community-wide reading culture. While the program provided support for developing a school-wide reading culture (e.g., training sessions, resources), schools were encouraged to make their own decisions about how to do so; there was no requirement to implement a specific set of evidenced-based activities, nor was adherence rigorously evaluated. Similarly, Pabion (2015) evaluated The National Literacy Trust’s Premier League Reading Stars program (PLRS)which incorporated lessons aligned with the national curriculum as well as supporting packs including posters, reading journals, wristbands and pencils, and online resources to promote a reading culture across the school. The author reports increases in reading enjoyment, confidence, frequency and performance following the 10-week program. However, it was not possible to evaluate or compare the particular practices which took place in each participating school, meaning the specific activities/approaches which contributed toward the observed positive outcomes are not clear.

Notably, implementing school-wide strategies to support the development of a reading culture makes it possible for schools to tailor an approach to their specific context. However, this approach also makes it difficult to identify which practices are most effective, and to generalize the findings to other settings. Furthermore, school-wide approaches often require additional support from school leadership teams, investment in the professional development of school staff, resource provision, space, time, and ongoing evaluation (ideally with feedback from students themselves), making their adoption and evaluation complex.

3.3. Book clubs

Book clubs are “small collaborative groups whose purpose is to enhance literacy and personal and social growth” (Polleck, 2010, p. 51), and represent a means of engaging readers with texts outwith classroom practice. Of the retrieved articles, those which have evaluated the use of book clubs for promoting adolescent reading motivation (N = 4) have focused on different motivation-related concepts and operated within a variety of different contexts. For example, in the U.S., Whittingham and Huffman (2009) reported that attending a book club once a week for one semester increased reading attitude in middle school (11–13-years-old) students (n = 60), particularly for those with the most negative attitudes toward reading at the outset. Tijms et al. (2018) reported that a 7-week book club intervention with students (n = 50) aged 12–14-years-old from urban, low-SES communities in the Netherlands also produced significant increases in reading attitude, alongside improvements in reading comprehension and social–emotional competencies, but not reading motivation. Evaluation of participation in a graphic novel (comic) book club (Gavigan, 2010) was also reported to have a positive effect on reading value and reading self-efficacy in struggling male readers (n = 4). These studies indicate the potential of positive motivational consequences from book club participation, particularly regarding reading attitude, value and self-efficacy.

However, there is still a need to develop greater understanding of the underlying mechanisms of book club success in order to inform best practice. Although the reviewed research did not always refer to a particular theory connecting book club participation with reading motivation, social theories of reading motivation and engagement (e.g., Guthrie et al., 1995) may be best applied to the approach. Furthermore, providing students autonomy over their choice of text appears beneficial for increasing engagement (Whittingham and Huffman, 2009; Gavigan, 2010; Schreuder and Savitz, 2020), as does supporting them to identify as readers (Gavigan, 2010), indicating potential mechanisms for change. However, individual book clubs will naturally differ significantly in terms of membership and group dynamics, quality of discussion, text type, meeting frequency, and environment. These variations are likely to affect how effective book clubs are, and for whom (e.g., depending on an individuals’ connection with the text, relationships with other group members, autonomy over text selection, etc.).

3.4. Technology-supported interventions

The growing availability of technology-supported reading resources has brought with it the possibility for digital materials to be used to support adolescents’ reading motivation. Recent research has indicated that the emergence and expansion of digital literacy environments supports the growing diversity of adolescents’ literacy experiences (Loh and Sun, 2019, 2022; Agosto, 2022). In the current review, 3 publications examining the effectiveness of technology-supported interventions in the classroom were identified.

In a U.S.-based exploration of how Nook e-readers affect students’ (N = 52; 15–17-years-old) attitudes toward reading, Dierking (2015) found that using e-readers for sustained silent reading in class was particularly beneficial for students who saw themselves as “reluctant readers.” The author identified 5 ‘qualities’ of e-readers which supported reading engagement: novelty, convenience, escape, privacy, and ‘flow’ (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). However, the authors also note that not all students experience the same levels of “connection or usability” (p. 415) with e-reader technology and that matching specific technology-supported interventions with the needs of students is essential. Indeed, more recent research has indicated that e-readers may be under-utilized by adolescents, with smartphones representing their preferred means of reading digitally (Loh and Sun, 2022).

Other types of technology-supported approaches for supporting adolescent reading motivation were also identified. For example, Gunter and Kenny (2012) evaluated the UB the Director program (part of Digital Booktalk; see also Gunter and Kenny, 2008), which supported reluctant readers (n = 48) to produce narrative videos about a class-assigned book. The approach was reported to “chang[e] opinions and misconceptions about reading” (p. 156). The underlying mechanism for this remained unclear, however connecting the use of technology to reading practices supported engagement within the sample. Greater insights into the aspects that adolescents find engaging and useful from technology-supported interventions are essential to develop resources to meet their needs. More contemporary approaches might utilize video platforms such as YouTube and TikTok to create links between adolescents’ reading practices and their online lives (e.g., Jerasa and Boffone, 2021). However, it should also be remembered that variation in digital skills may pose a barrier for some students (see Sefton-Green et al., 2009) and teachers/practitioners in adopting technology-supported approaches. Care should be taken to ensure technology-supported programs are suitably tailored to the needs and skills of individuals. Finally, access to technology varies considerably based on individual ownership, school budget etc.; this should also be held in mind when considering technology-supported interventions to support adolescent reading motivation so as not to amplify existing inequalities.

3.5. Performance and theater

Finally, the search yielded several articles which had trialed performance and theater interventions to support reading engagement and motivation in adolescents (N = 2). For example, Whittington (2012) examined the effect of a semester-long reading fluency and prosody intervention on reading attitude in struggling and unmotivated 6th – 8th Grade (11–14-years-old) readers. The intervention used dramatic reading to engage students with texts, as well as to support their fluency skills. Following the program, over one third of students reported a more positive attitude toward reading than at the start. Richardson (2014) also reported that a 6-week Reader’s Theater intervention was related to increases in reading motivation and attitude in 9th and 10th (14–16-years-old) Grade students (n = 24) reading below the expected standard for their age; active involvement through performance reportedly made reading more enjoyable and allowed students to become more comfortable engaging with reading activities.

These types of intervention represent a unique approach to supporting adolescent reading motivation, one which only emerged in two studies fitting the inclusion criteria for this review. However, it is notable that when considering approaches for supporting motivation for reading and literacy activities, it is easy to neglect intersecting practices (e.g., performance, creative writing) that may also contribute toward reading engagement and enjoyment. Although the mechanisms of change for performance and theater interventions were not clear from the retrieved studies, these explorations provide useful insights into holistic conceptualizations of engaging with texts.

4. Discussion and recommendations

This review provides a synthesis of approaches which have previously been implemented to support adolescents’ reading motivation. In this final section, we reflect on the research by first identifying the gaps and issues with existing literature, followed by providing recommendations for future research and practice. In relation to gaps and issues, these included:

• A lack of consistency in terms of definition, operationalization, and application of theory and concepts regarding adolescent reading motivation.

• A primary focus on supporting reading motivation in students whose reading skills fall below the expected standard for their age.

• A primary focus on adolescents’ in-school reading practices.

4.1. A lack of consistency in terms of definition, operationalization, and application of reading motivation theory

Previous research has already highlighted the multidimensional and complex nature of reading motivation (Schiefele et al., 2012), as well as the inconsistency in its definition (e.g., Schiefele et al., 2012; Conradi et al., 2014; Toste et al., 2020; Ives et al., 2023). For example, many motivation-related concepts have previously been used interchangeably with reading motivation (Conradi et al., 2014; Ives et al., 2023). To account for the variation in terminology, we utilized search terms which would also identify studies which used related concepts (e.g., reading attitude, reading value). Indeed, in the studies retrieved, reading motivation was conceptualized and measured in myriad ways. Furthermore, outcome measures related both to motivation (e.g., Motivations for Reading Questionnaire, Wigfield and Guthrie, 1997) and motivation-related concepts, including measures of reading attitude (e.g., Whittingham and Huffman, 2009), self-efficacy (e.g., Gavigan, 2010), value (e.g., Guthrie and Klauda, 2014), and self-concept (e.g., Melekoglu, 2011; see Table 1). Additionally, some studies referred to other, less-quantifiable outcomes such as having more positive perceptions about reading ability, or perceiving reading as ‘cool’. The lack of clear and consistent use of terminology makes searching for relevant information challenging (Schiefele et al., 2012; Jang et al., 2015), and underscores one reason why this review is much needed.

Second, it was notable that many of the approaches applied did not have a clear underlying theory to guide their development or application. Understanding the theoretical framework from within which an approach has been chosen is important for understanding the proposed mechanism of change. In the current review, much of the literature did not make explicit reference to a particular theoretical model. This is consistent with earlier findings (Conradi et al., 2014). Approaches which did make reference to specific theory cited variously: Bandura’s (2008) Observational Learning Theory (e.g., Dierking, 2015), Vygotsky’s (1978) social development theory (e.g., Richardson, 2014; Farkas and Jang, 2019), Guthrie and Cox’s (2001) motivational, cognitive and behavioral theories of engagement (e.g., Guthrie and Klauda, 2014), and Schumaker and Deshler’s (1992) self-regulated learning and generalization (e.g., Cantrell et al., 2011, 2013, 2014, 2016). Others made more vague reference to underlying theories (e.g., social theories of literacy and motivation, cognitive theories and strategic processing theories), while some did not report a theoretical basis for their approach (Morris et al., 2021 note the lack of a theory of change for the LfL program as a potential explanation for its lack of effective motivational outcomes). Unrau and Quirk (2014) note that “[t]he existence of an array of theories and models of motivation for reading and reading engagement has contributed to a significant degree of perplexity for practitioners and researchers applying and investigating these constructs” (p. 260). As noted by Conradi et al. (2014), it is unlikely that a single theory could encompass all aspects of reading motivation, however clearly outlining the proposed theoretical underpinnings of an approach can contribute toward the refinement of models for understanding reading motivation. Furthermore, understanding how and why a particular approach has been chosen will help teachers and practitioners to make more informed decisions about applying their principles across contexts and modify them for the needs of their own classrooms.

4.2. A primary focus on supporting reading motivation among students whose reading skills fall below the expected standard for their age

It was notable that many of the publications retrieved for this review exhibited a strong focus on “struggling” readers, or those scoring below the expected standard on measures of reading skills. Supporting the continued development of reading skills into adolescence is important (Ricketts et al., 2020), especially for those with additional barriers. Interestingly, of the studies which utilized reading and literacy skills programs, reading motivation was often positioned as an additional outcome alongside reading and literacy skills (i.e., there were no examples of skills-based approaches to supporting motivation which focused solely on motivational outcomes). Furthermore, only one study sought to support reading motivation among students with literacy skills at or above the expected standard for their age but who displayed low levels of reading motivation or engagement (Gunter and Kenny, 2012; although whole-school approaches necessarily include students across reading levels). This represents a significant gap in our collective knowledge. Skilled, reluctant readers should be an important focus for future inquiry as it is likely that their motivation to read (or not) is not necessarily bound to their reading skill. This could provide further insights into the reciprocal relationship between reading skills and motivation (Morgan and Fuchs, 2007; Toste et al., 2020) as it pertains to adolescents’ reading motivation in particular.

Relatedly, as noted above, a large number of approaches which have a motivation component often have a more primary focus on skills-and/or attainment-based outcomes or use skills programs as a means of supporting motivation. However, reading has previously been associated not only with academic performance (e.g., Krashen, 2004; Clark and Douglas, 2011; Mol and Bus, 2011), but with a range of non-academic outcomes including empathy (Mar et al., 2009), social cognition and social skills (Mar et al., 2006; Mar and Oatley, 2008; Eekhof et al., 2022), theory of mind (Kidd and Castano, 2013), and personal development (Howard, 2011). Despite this, many approaches have positioned motivation as a complementary outcome to a more primary goal of improving reading skills and/or attainment (Aukerman and Chambers Schuldt, 2021). Although there are many educators, researchers, and organizations who champion reading for pleasure, such a focus is not always present in research, particularly in experimental and intervention work. For students struggling with particular reading skills (e.g., fluency, decoding), approaches which support both motivation and skills may be doubly beneficial in that they allow for the possibility of a combined effect on both priority areas. However, for students with secure reading skills, it is unclear whether repetition of skills instruction where students are already proficient may diminish their motivation to read.

4.3. A primary focus on adolescents’ in-school reading practices

Finally, the studies included here detail approaches which have been conducted almost exclusively within school environments. This aligns with a previous scoping review which found that for students aged 9–12 years old, the number of studies on reading support offered by teachers far surpasses the number offered by parents or peers (Pelletier et al., 2022). There are several reasons why this is likely to be the case. First, school is the environment within which adolescents spend the majority of their time and where it is most likely that systematic approaches to supporting their reading motivation could logistically take place. Second, teachers are often looking for ways to support their students’ learning and development, as well as their own professional practice and are therefore likely to be enthusiastic about trialing new programs. It is also possible that activities related to reading and literacy align most closely with the perceived responsibilities of schools and teachers; schools may be perceived as the ‘right’ (or only) vectors of change for literacy-related outcomes. However, it is important to understand adolescents not simply as students whose lives exist only within the classroom; they have experiences outside of school which feed into their attitudes, goals, and motivations and these should be incorporated into research and practice.

Furthermore, reading motivation varies based on context and it is important for researchers teachers, and practitioners to find ways to support adolescents to “connect who they are to what they do in school” (Oldfather and Dahl, 1994, p. 142), supporting reading motivation in the home, amongst peers, and in communities, and situating it as a lifelong practice, rather than something only pursued within formal education is essential (Moje, 2002; Merga and Moon, 2016; Aukerman and Chambers Schuldt, 2021).

Additionally, much previous reading motivation research may have failed to consider or challenge the beliefs which underpin our understandings of how reading motivation is enacted, or to acknowledge the ways in which race, class, disability, gender, and other socio-cultural factors may intersect to influence reading and literacy outcomes (Willis, 2002; Jones, 2020). Jones (2022) challenges us to “reframe the narrative” (p. 16) surrounding adolescent reading motivation and pay closer attention to the sociocultural context within which reading motivation is being defined and measured. Therefore, when designing, selecting, and implementing approaches to support adolescent readers, it is imperative to think about how reading motivation is being defined, why it is being defined this way, how these definitions may exclude or marginalize different groups. Notably, in the current review, the majority of papers retrieved were conducted from within U.S., U.K., and European contexts, illustrating a gap in collective knowledge regarding approaches which have been used elsewhere.

With the above gaps and limitations in mind, we now propose three recommendations to guide the future of research and practice within the field of adolescent reading motivation. These include:

• Adopting flexible and multifaceted approaches which are based on theory and make consistent use of terminology.

• Facilitating deeper and more reciprocal connections between research and practice.

• Centering the experiences, attitudes, values, and opinions of adolescents themselves in the design and implementation of reading motivation support.

4.4. Adopting flexible and multifaceted approaches which are based on theory and make consistent use of terminology

Systematic approaches to supporting adolescents’ reading motivation have, in many instances, provided promising insights into how different types of programs might support different outcomes. Those which report positive outcomes have often adopted a multifaceted approach, using a range of evidence-and theory-based strategies to engage and inspire students (e.g., CORI). Indeed, Gilson et al. (2018) have suggested that systematic motivational support embedded throughout multiple interventions may be most effective in promoting motivation for reading. This may be because the reasons adolescents report for reading, or not reading, differ widely (Wilkinson et al., 2020), and change over time and context (Ladson-Billings, 1992). As noted above, previous research has already highlighted the multidimensional and complex nature of reading motivation (Schiefele et al., 2012). Therefore, it is important that multifaceted approaches are guided by theories which capture this, and which are specifically relevant to the adolescent period. Notably, approaches which achieve this, while simultaneously reflecting the diverse needs of schools, groups, and/or individual students, likely require a longer-term approach to implementation; being open and flexible to exploring the needs of particular groups and modifying approaches based on theory and evidence may be most effective in the long-term. Indeed, this type of flexible and multi-faceted approach will require teachers and other education professionals working with adolescents to have considerable depth of research knowledge, so they are better positioned to exercise their professional judgment to implement practices to support adolescents’ reading motivation in ways which respond to their students’ interests, needs, abilities and contexts, while also being research-informed. It also requires consistent use of terminology to support the interpretation and utilization of research findings.

4.5. Facilitating deeper and more reciprocal connections between research and practice

Experimental research is invaluable for using systematic inquiry to move closer toward an understanding of both how and why a particular intervention works for particular groups. However, this research has the potential to be somewhat disconnected from classroom practice. For example, if a program is developed by external researchers, it is less likely that the approach will meet the needs of those working in practice. With this in mind, it is important that both implementation and effectiveness outcomes are considered in the design and evaluation of literacy support (Moir, 2018). Designing programs in collaboration with practitioners (e.g., through research-practice partnerships, co-designed projects, participatory designs) enables issues of implementation (e.g., acceptability and feasibility) to be embedded from the outset and to include the perspectives of those who will use them in practice (McGeown, 2023). A more collaborative approach requires putting the pedagogical and professional knowledge, experience, and expertise of educators at the forefront of future exploration. Interweaving researcher knowledge regarding theory and existing research creates opportunities to co-create programs which utilize academic research in effective and sustainable ways. Furthermore, collaborating with organizations outside of school (e.g., youth centers, charities) will provide opportunities for the exploration and incorporation of adolescents’ out-of-school literacy practices, which are much overlooked in reading motivation research. Finally, collaboration between researchers and practitioners is important to ensure that research generally reflects the interest and priorities of communities, not only researchers (McGeown, 2023). Combined, these reasons provide a compelling argument to ensure the design and evaluation of future support is a collaborative venture between researchers and communities.

An additional consideration is in ensuring the communication of academic research in ways which reach, are accessible to, and are of value to, educators (Solari et al., 2020). Narrative and scoping reviews such as these can be valuable in terms of synthesizing approaches and findings for educators, especially where there exists great variety in terms of approaches used. However, continued and open dialogues with educators are also important to ensure researchers understand the ways academic research reaches and affects the practice with those responsible for implementing it.

4.6. Centering the experiences, attitudes, values, and opinions of adolescents themselves in the design and implementation of reading motivation support

There is growing recognition of the value and importance of participatory approaches to working with adolescents, both within literacy research (Levy and Thompson, 2015; Calderón López and Theriault, 2017; Webber et al., 2022), but also more generally (e.g., Freire et al., 2022). The approaches to supporting adolescent reading motivation identified in this review reflected a wide diversity of methods, however, no studies were found where adolescents themselves took part in the development or implementation of a program or intervention. While some studies asked for participants’ reflections on particular interventions as part of data collection (e.g., Huang, 2012), no studies worked with students themselves to develop or evaluate an intervention. In the context of adolescent reading motivation, Merga and Moon (2016) note that few studies “have allowed the students to articulate their own views based on their own experience” (p. 134) and that “we risk obscuring the reality of students’ own understandings of their motivations to read by extrapolating theory from studies rigidly designed and dictated by preconceived notions of adolescent literacy” (p. 134). Encouraging adolescents to share their own views regarding their reading experiences (both in and out of school) is essential in ensuring reading motivation is being measured and supported in ways that are meaningful to them. Future work, both within schools and academic research, should explore participatory and co-production methodologies to work with all adolescents (not just those with reading skills below the expected standard) and ensure their opinions and experiences are integrated. Indeed, synthesizing adolescents’ perspectives with existing theory, research and critical reflection may be most effective at creating interventions which genuinely reach and resonate with adolescents.

To conclude, we hope that this review provides a useful description of the extent, range, and nature of approaches for supporting adolescent reading motivation which have been studied previously. We also hope that it has identified key gaps and issues within the current research base (e.g., lack of conceptual clarity, application of theory), and provided some useful suggestions for future work within the field.

Author contributions

CW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. KW: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LD: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the ESRC and Scottish Book Trust and managed by SGSSS. Grant reference number ES/P000681/1. Open access publication fees provided by SGSSS.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Scottish Book Trust for supporting this research as part of the first author’s collaborative studentship.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1254048/full#supplementary-material

References

Agosto, D. E. (2022). Reflections on adolescent literacy as sociocultural practice. Inform. Learn. Sci. 123, 723–737. doi: 10.1108/ILS-02-2022-0013

Allred, J. B., and Cena, M. E. (2020). Reading motivation in high school: Instructional shifts in student choice and class time. J. Adolesc. Adult. Lit. 64, 27–35. doi: 10.1002/jaal.1058

*Alvermann, D. E., Hagood, M. C., Heron-Hruby, A., Hughes, P., Williams, K. B., and Yoon, J. C., (2007). Telling themselves who they are: What one out-of-school time study revealed about underachieving readers. Read. Psychol., 28, 31–50, doi: 10.1080/02702710601115455

Arksey, H., and O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Aukerman, M., and Chambers Schuldt, L. (2021). What matters most? Toward a robust and socially just science of reading. Read. Res. Q. 56, S85–S103. doi: 10.1002/rrq.406

*Ayyub, B. J. M., (2011). Developing a guided reading and multi literacy programme for the academically-challenged students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci., 30, 1281–1285, doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.248

Baethge, C., Goldbeck-Wood, S., and Mertens, S. (2019). SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 4, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/s41073-019-0064-8

Bandura, A., (2008). Observational learning. In: The international encyclopedia of communication. (Ed.) W. Donsbach. doi: 10.1002/9781405186407.wbieco004

Bastian, H., Glasziou, P., and Chalmers, I. (2010). Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 7:e1000326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326

*Berry, T., Eddy, R. M., Fleischer, D., Asgarian, M., and Malek, Y., (2007). The Effects of Prentice Hall Literature. Claremont, CA: Claremont Graduate University.

Broeder, P., and Stokmans, M. (2013). Why should I read?-A cross-cultural investigation into adolescents’ reading socialisation and reading attitude. Int. Rev. Educ. 59, 87–112. doi: 10.1007/s11159-013-9354-4

Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 56, 1391–1412. doi: 10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

Calderón López, M., and Theriault, V. (2017). Accessing a'very, very secret garden': exploring children's and young people's literacy practices using participatory research methods. Lang. Liter. 19, 39–54. doi: 10.20360/G26371

*Cantrell, S. C., Almasi, J. F., Carter, J. C., and Rintamaa, M., (2011). Striving Readers Final Evaluation Report: Danville, Kentucky, Collaborative Center for Literacy Development. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED601005.pdf.

*Cantrell, S. C., Almasi, J. F., Carter, J. C., and Rintamaa, M., (2013). Reading intervention in middle and high schools: Implementation fidelity, teacher efficacy, and student achievement. Read. Psychol., 34, 26–58, doi: 10.1080/02702711.2011.577695

Cantrell, S.C., Almasi, J.F., Carter, J.C., Rintamaa, M., Belcher, K., Parker, C., et al. (2008). Striving Readers: Implementation of the targeted and the whole school interventions summary of Year 1 (2006–07). Report prepared for the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, U.S. Department of Education

*Cantrell, S. C., Almasi, J. F., Rintamaa, M., and Carter, J. C., (2016). Supplemental reading strategy instruction for adolescents: a randomized trial and follow-up study. J. Educ. Res., 109, 7–26, doi: 10.1080/00220671.2014.917258

*Cantrell, S. C., Almasi, J. F., Rintamaa, M., Carter, J. C., Pennington, J., and Buckman, D. M. (2014). The impact of supplemental instruction on low-achieving adolescents’ reading engagement. J. Educ. Res., 107, 36–58. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2012.753859

*Cantrell, S. C., Carter, J. C., and Rintamaa, M., (2012). Striving readers cohort II evaluation report: Kentucky. Collaborative Center for Literacy Development. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED601010.pdf.

Clark, C. (2019). Children and young people's reading in 2017/18: findings from our annual literacy survey National Literacy Trust Research Report. National Literacy Trust. Available at: https://cdn.literacytrust.org.uk/media/documents/Reading_trends_in_2017-18.pdf.

Clark, C., and Douglas, J. (2011). Young people's reading and writing: an in-depth study focusing on enjoyment, behaviour, attitudes and attainment National Literacy Trust. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED521656.pdf.

Clark, C., and Teravainen-Goff, A. (2020). Children and young people's reading in 2019: findings from our annual literacy survey. National Literacy Trust Research Report National Literacy Trust. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED607777.pdf.

*Cockroft, C., and Atkinson, C., (2017). ‘I just find it boring’: Findings from an affective adolescent reading intervention. Support Learn., 32, 41–59, doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12147

Cole, A., Brown, A., Clark, C., and Picton, I. (2022). Children and young people's reading engagement in 2022: continuing insight into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on reading. national literacy trust research report National Literacy Trust. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED627073.pdf.

Conradi, K., Jang, B. G., and McKenna, M. C. (2014). Motivation terminology in reading research: A conceptual review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 26, 127–164. doi: 10.1007/s10648-013-9245-z

*Cosentino, C. L., (2017). The effects of self-regulation strategies on reading comprehension, motivation for learning, and self-efficacy with struggling readers. Western Connecticut State University. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1946738657.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., 1990. Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (1990). New York: Harper & Row.

*Cuevas, J. A., Russell, R. L., and Irving, M. A., (2012). An examination of the effect of customized reading modules on diverse secondary students’ reading comprehension and motivation. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev., 60, 445–467, doi: 10.1007/s11423-012-9244-7

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1980). Self-determination theory: when mind mediates behavior. J. Mind Behav., 1, 33–43.

*Dierking, R., (2015). Using nooks to hook reluctant readers. J. Adolesc. Adult. Lit., 58, 407–416, doi: 10.1002/jaal.366

Eccles, J. S., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., et al. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In: Achievement and achievement motivation. Ed. J. T. Spence. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. 75–146.

Eccles, J. S., and Wigfield, A. (1995). In the mind of the actor: the structure of adolescents' achievement task values and expectancy-related beliefs. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 21, 215–225. doi: 10.1177/0146167295213003

Eekhof, L. S., Van Krieken, K., and Willems, R. M. (2022). Reading about minds: The social-cognitive potential of narratives. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 29, 1703–1718. doi: 10.3758/s13423-022-02079-z

Erbeli, F., and Rice, M. (2021). Examining the effects of silent independent reading on reading outcomes: a narrative synthesis review from 2000 to 2020. Read. Writ. Q., 38, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/10573569.2021.1944830

*Farkas, W. A., and Jang, B. G., (2019). Designing, implementing, and evaluating a school-based literacy program for adolescent learners with reading difficulties: a mixed-methods study. Read. Writ. Q., 35, 305–321, doi: 10.1080/10573569.2018.1541770

*Francois, C. (2013). Reading in the crawl space: A study of an urban school’s literacy-focused community of practice. Teach. Coll. Rec., 115, 1–35, doi: 10.1177/016146811311500504

Freire, K., Pope, R., Jeffrey, K., Andrews, K., Nott, M., and Bowman, T. (2022). Engaging with children and adolescents: a systematic review of participatory methods and approaches in research informing the development of health resources and interventions. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 7, 335–354. doi: 10.1007/s40894-022-00181-w

*Gatti, G. G. (2011). Pearson Success Maker reading efficacy study: 2010–11 final report. Pittsburgh, PA: Gatti Evaluation.

*Gavigan, K. W. (2010). Examining struggling male adolescent readers' responses to graphic novels: a multiple case study of four, eighth-grade males in a graphic novel book club. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/751264473.

*Gilson, C. M., Beach, K. D., and Cleaver, S. L. (2018). Reading motivation of adolescent struggling readers receiving general education support. Read. Writ. Q., 34, 505–522, doi: 10.1080/10573569.2018.1490672

Gottfried, A. E. (1998) Academic intrinsic motivation in high school students: Relationships with achievement, perception of competence, and academic anxiety. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA

Green, B. N., Johnson, C. D., and Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 5, 101–117. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6

Gunter, G., and Kenny, R. (2008). Digital booktalk: digital media for reluctant readers. Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 8, 84–99.

*Gunter, G. A., and Kenny, R. F., (2012). UB the director: utilizing digital book trailers to engage gifted and twice-exceptional students in reading. Gift. Educ. Int., 28, 146–160, doi: 10.1177/0261429412440378

Guthrie, J. T., Coddington, C. S., and Wigfield, A. (2009). Profiles of reading motivation among African American and Caucasian students. J. Lit. Res. 41, 317–353. doi: 10.1080/10862960903129196

Guthrie, J. T., and Cox, K. E. (2001). Classroom conditions for motivation and engagement in reading. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 13, 283–302. doi: 10.1023/A:1016627907001

*Guthrie, J. T., and Klauda, S. L. (2014). Effects of classroom practices on reading comprehension, engagement, and motivations for adolescents. Read. Res. Q., 49, 387–416, doi: 10.1002/rrq.81

Guthrie, J. T., Schafer, W., Wang, Y. Y., and Afflerbach, P. (1995). Relationships of instruction to amount of reading: an exploration of social, cognitive, and instructional connections. Read. Res. Q. 30, 8–25. doi: 10.2307/747742

Henk, W. A., and Melnick, S. A. (1995). The reader self-perception scale (RSPS): A new tool for measuring how children feel about themselves as readers. Read. Teach. 48, 470–482.

Hopper, R. (2005). What are teenagers reading? Adolescent fiction reading habits and reading choices. Literacy 39, 113–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9345.2005.00409.x

Howard, V. (2011). The importance of pleasure reading in the lives of young teens: self-identification, self-construction and self-awareness. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 43, 46–55. doi: 10.1177/0961000610390992

*Huang, S. (2012). A mixed method study of the effectiveness of the Accelerated Reader program on middle school students’ reading achievement and motivation. Read. Horizons, 51, 228–246.

Ives, S. T., Parsons, S. A., Cutter, D., Field, S. A., Wells, M. S., and Lague, M. (2023). Intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation: context, theory, and measurement. Read. Psychol. 44, 306–325. doi: 10.1080/02702711.2022.2141403

Jang, B. G., Conradi, K., McKenna, M. C., and Jones, J. S. (2015). Motivation: Approaching an elusive concept through the factors that shape it. Read. Teach. 69, 239–247. doi: 10.1002/trtr.1365

Jerasa, S., and Boffone, T. (2021). Book Tok 101: Tik Tok, digital literacies, and out-of-school reading practices. J. Adolesc. Adult. Lit. 65, 219–226. doi: 10.1002/jaal.1199

Jerzembek, G., and Murphy, S. (2013). A narrative review of problem-based learning with school-aged children: implementation and outcomes. Educ. Rev. 65, 206–218. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2012.659655

Jones, S. (2020). Measuring reading motivation: A cautionary tale. Read. Teach. 74, 79–89. doi: 10.1002/trtr.1912

Jones, S. (2022). Turning away from anti-blackness: a critical review of adolescent reading motivation research. Read. Res. Q. 57, 1–21. doi: 10.1002/rrq.462

Kidd, D. C., and Castano, E. (2013). Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science 342, 377–380. doi: 10.1126/science.1239918

Krashen, S. D. (2004). The power of reading: Insights from the research, 2nd Edition. Greenwood Publishing Group, USA.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1992). Liberatory consequences of literacy: a case of culturally relevant instruction for African American students. J. Negro Educ. 61, 378–391. doi: 10.2307/2295255

Lazowski, R. A., and Hulleman, C. S. (2016). Motivation interventions in education: a meta-analytic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 602–640. doi: 10.3102/0034654315617832

*Lesaux, N. K., Harris, J. R., and Sloane, P. (2012). Adolescents’ motivation in the context of an academic vocabulary intervention in urban middle school classrooms. J. Adolesc. Adult. Lit., 56, 231–240, doi: 10.1002/JAAL.00132

Levy, R., and Thompson, P. (2015). Creating ‘buddy partnerships’ with 5-and 11-year old-boys: a methodological approach to con-ducting participatory research with young children. J. Early Child. Res. 13, 137–149. doi: 10.1177/1476718X13490297

*Littlefield, A. R. (2011). The relations among summarizing instruction, support for student choice, reading engagement and expository text comprehension. Pro Quest LLC. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/908612968.

Loh, C. E., and Sun, B. (2019). “I'd still prefer to read the hard copy”: adolescents’ print and digital reading habits. J. Adolesc. Adult. Lit. 62, 663–672. doi: 10.1002/jaal.904

Loh, C. E., and Sun, B. (2022). The impact of technology use on adolescents' leisure reading preferences. Literacy 56, 327–339. doi: 10.1111/lit.12282

Mar, R. A., and Oatley, K. (2008). The function of fiction is the abstraction and simulation of social experience. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 3, 173–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00073.x

Mar, R. A., Oatley, K., Hirsh, J., Dela Paz, J., and Peterson, J. B. (2006). Bookworms versus nerds: Exposure to fiction versus non-fiction, divergent associations with social ability, and the simulation of fictional social worlds. J. Res. Pers. 40, 694–712. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.002

Mar, R. A., Oatley, K., and Peterson, J. B. (2009). Exploring the link between reading fiction and empathy: Ruling out individual differences and examining outcomes. Communications 34, 407–428. doi: 10.1515/COMM.2009.025

McBreen, M., and Savage, R. (2020). The impact of motivational reading instruction on the reading achievement and motivation of students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33, 1–39. doi: 10.1007/s10648-020-09584-4

McGeown, S. (2023). practice partnerships in education: why we need a methodological shift in how we do research. Educ. Rev. 47, 6–14.

McKenna, M. C., Conradi, K., Lawrence, C., Jang, B. G., and Meyer, J. P. (2012). Reading attitudes of middle school students: results of a US survey. Read. Res. Q. 47, 283–306. doi: 10.1002/rrq.021

McTigue, E. M., Solheim, O. J., Walgermo, B., Frijters, J., and Foldnes, N. (2019). How can we determine students’ motivation for reading before formal instruction? Results from a self-beliefs and interest scale validation. Early Child. Res. Q. 48, 122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.12.013

*Melekoglu, M. A. (2011). Impact of motivation to read on reading gains for struggling readers with and without learning disabilities. Learn. Disabil. Q., 34, pp. 248–261, doi: 10.1177/0731948711421761

Merga, M. K., and Moon, B. (2016). The impact of social influences on high school students' recreational reading. High Sch. J. 99, 122–140. doi: 10.1353/hsj.2016.0004

Miyamoto, A., Pfost, M., and Artelt, C. (2019). The relationship between intrinsic motivation and reading comprehension: Mediating effects of reading amount and metacognitive knowledge of strategy use. Sci. Stud. Read. 23, 445–460. doi: 10.1080/10888438.2019.1602836

Moir, T. (2018). Why is implementation science important for intervention design and evaluation within educational settings? Front. Educ. 3, 1–9. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00061

Moje, E. B. (2002). Re-framing adolescent literacy research for new times: studying youth as a resource. Literacy Res. Instruct. 41, 211–228. doi: 10.1080/19388070209558367

Mokhtari, K., and Reichard, C. A. (2002). Assessing students' metacognitive awareness of reading strategies. J. Educ. Psychol. 94:249. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.94.2.249

Mol, S. E., and Bus, A. G. (2011). To read or not to read: a meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychol. Bull. 137:267. doi: 10.1037/a0021890

Moore, D. W., Bean, T. W., Birdyshaw, D., and Rycik, J. A. (1999). Adolescent literacy: a position statement. J. Adolesc. Adult. Lit. 43, 97–112.

Morgan, P. L., and Fuchs, D. (2007). Is there a bidirectional relationship between children's reading skills and reading motivation? Except. Child. 73, 165–183. doi: 10.1177/001440290707300203

*Morris, R., See, B. H., Gorard, S., and Siddiqui, N. (2021). Literacy for life: evaluating the National Literacy Trust’s bespoke programme for schools. Educ. Stud. 49, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2020.1867077

Murnan, R., Parsons, S. A., and Verbiest, C. (2023). Striving adolescent readers’ motivation. Liter. Res. Instruct. 62, 127–154. doi: 10.1080/19388071.2022.2115957

*Ng, C. H. C., Bartlett, B., Chester, I., and Kersland, S. (2013). Improving reading performance for economically disadvantaged students: Combining strategy instruction and motivational support. Read. Psychol., 34, 257–300, doi: 10.1080/02702711.2011.632071

Nunnery, J., Ross, S., and McDonald, A. (2006). A randomized experimental evaluation of the impact of accelerated reader/reading renaissance implementation on reading achievement in grades 3 to 6. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk 11, 1–18. doi: 10.1207/s15327671espr1101_1

Okkinga, M., van Steensel, R., van Gelderen, A. J., van Schooten, E., Sleegers, P. J., and Arends, L. R. (2018). Effectiveness of reading-strategy interventions in whole classrooms: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 30, 1215–1239. doi: 10.1007/s10648-018-9445-7

Oldfather, P., and Dahl, K. (1994). Toward a social constructivist reconceptualization of intrinsic motivation for literacy learning. J. Read. Behav. 26, 139–158. doi: 10.1080/10862969409547843

*Pabion, C. (2015). Premier league reading STARS 2013/14. Evaluation Report. National Literacy Trust. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED560658.pdf

Pelletier, D., Gilbert, W., Guay, F., and Falardeau, É. (2022). Teachers, parents and peers support in reading predicting changes in reading motivation among fourth to sixth graders: a systematic literature review. Read. Psychol. 43, 317–356. doi: 10.1080/02702711.2022.2106332

Pitcher, S. M., Albright, L. K., DeLaney, C. J., Walker, N. T., Seunarinesingh, K., Mogge, S., et al. (2007). Assessing adolescents' motivation to read. J. Adolesc. Adult. Lit. 50, 378–396. doi: 10.1598/JAAL.50.5.5

Polleck, J. N. (2010). Creating transformational spaces: high school book clubs with inner-city adolescent females. High Sch. J. 93, 50–68. doi: 10.1353/hsj.0.0042

*Research Scotland (2020) Evaluation of the First Minister’s Reading Challenge: Final Report. Available at: https://www.readingchallenge.scot/sites/default/files/2021-02/First%20Minister%27s%20Reading%20Challenge%20Evaluation%202020.pdf (Accessed May 19, 2021)

*Richardson, E. M. (2014). Motivating struggling adolescent readers to read: an action research study. Capella University. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1537392666.

Ricketts, J., Lervåg, A., Dawson, N., Taylor, L. A., and Hulme, C. (2020). Reading and oral vocabulary development in early adolescence. Sci. Stud. Read. 24, 380–396. doi: 10.1080/10888438.2019.1689244

*Schaffner, E., and Schiefele, U. (2007). The effect of experimental manipulation of student motivation on the situational representation of text. Learn. Instr., 17, 755–772, doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.09.015

Schiefele, U., Schaffner, E., Möller, J., and Wigfield, A. (2012). Dimensions of reading motivation and their relation to reading behavior and competence. Read. Res. Q. 47, 427–463. doi: 10.1002/RRQ.030

Schiller, E., Wei, X., Thayer, S., Blackorby, J., Javitz, H., and Williamson, C. (2012). A randomized controlled trial of the impact of the fusion reading intervention on reading achievement and motivation for adolescent struggling readers SRI International. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED600883.pdf.

Schreuder, M. C., and Savitz, R. S. (2020). Exploring adolescent motivation to read with an online YA book club. Liter. Res. Instr. 59, 260–275. doi: 10.1080/19388071.2020.1752860

Schumaker, J. B., and Deshler, D. D. (1992). “Validation of learning strategy interventions for students with learning disabilities: results of a programmatic research effort” in Contemporary intervention research in learning disabilities: disorders of human learning, hehavior, and communication. eds. B. Y. L. Wong (Springer New York: New York, NY), 22–46. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-2786-1_2

Schumaker, J. B., and Deshler, D. D. (2006). “Teaching adolescents to be strategic learners” in Teaching adolescents with disabilities: accessing the general education curriculum. eds. J. B. Schumaker and D. D. Deshler (Corwin Press), 121–156.

Schutte, N. S., and Malouff, J. M. (2007). Dimensions of reading motivation: development of an adult reading motivation scale. Read. Psychol. 28, 469–489. doi: 10.1080/02702710701568991

Sefton-Green, J., Nixon, H., and Erstad, O. (2009). Reviewing approaches and perspectives on “digital literacy”. Pedagogies 4, 107–125. doi: 10.1080/15544800902741556

Shell, D. F., Colvin, C., and Bruning, R. H. (1995). Self-efficacy, attribution, and outcome expectancy mechanisms in reading and writing achievement: grade-level and achievement-level differences. J. Educ. Psychol. 87:386. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.87.3.386

*Siddiqui, N., Gorard, S., and See, B. H., (2016). Accelerated reader as a literacy catch-up intervention during primary to secondary school transition phase. Educ. Rev., 68, 139–154. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2015.1067883

Solari, E. J., Terry, N. P., Gaab, N., Hogan, T. P., Nelson, N. J., Pentimonti, J. M., et al. (2020). Translational science: a road map for the science of reading. Read. Res. Q. 55, S347–S360. doi: 10.1002/rrq.357

*Swanlund, A., Dahlke, K., Tucker, N., Kleidon, B., Kregor, J., et al. (2012). Striving Readers: Impact Study and Project Evaluation Report--Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (with Milwaukee Public Schools). American Institutes for Research. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED595200.pdf

*Taboada Barber, A. M., Buehl, M. M., Kidd, J. K., Sturtevant, E. G., Nuland, L. R., and Beck, J., (2015). Reading engagement in social studies: exploring the role of a social studies literacy intervention on reading comprehension, reading self-efficacy, and engagement in middle school students with different language backgrounds. Read. Psychol., 36, 31–85. doi: 10.1080/02702711.2013.815140

Thompson, G., Madhuri, M., and Taylor, D. (2008). How the Accelerated Reader program can become counterproductive for high school students. J. Adolesc. Adult. Lit. 51, 550–560. doi: 10.1598/JAAL.51.7.3

*Tijms, J., Stoop, M. A., and Polleck, J. N. (2018). Bibliotherapeutic book club intervention to promote reading skills and social–emotional competencies in low SES community-based high schools: A randomised controlled trial. J. Res. Read., 41, 525–545, doi: 10.1111/1467-9817.12123

Toste, J. R., Didion, L., Peng, P., Filderman, M. J., and McClelland, A. M. (2020). A meta-analytic review of the relations between motivation and reading achievement for K–12 students. Rev. Educ. Res. 90, 420–456. doi: 10.3102/0034654320919352

*Tsikalas, K. E. (2012). Effects of video-based peer modeling on the question asking, reading motivation and text comprehension of struggling adolescent readers. City University of New York. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1018554046.

Twenge, J. M., Martin, G. N., and Spitzberg, B. H. (2019). Trends in US Adolescents’ media use, 1976–2016: The rise of digital media, the decline of TV, and the (near) demise of print. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 8:329. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000203

Unrau, N.J., and Quirk, M. (2014). Reading motivation and reading engagement: Clarifying commingled conceptions. Reading Psychology. 35, 260–284. doi: 10.1080/02702711.2012.684426

Unrau, N. J., Rueda, R., Son, E., Polanin, J. R., Lundeen, R. J., and Muraszewski, A. K. (2017). Can reading self-efficacy be modified? A meta-analysis of the impact of interventions on reading self-efficacy. Rev. Educ. Res. 88, 167–204. doi: 10.3102/0034654317743199

*Vaden-Kiernan, M., Caverly, S., Bell, N., Sullivan, K., Fong, C., Atwood, E., et al. (2012). Louisiana striving readers: final evaluation report. SEDL. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED595145.pdf.

*Waleff, M. L. (2010). The relationship between mastery orientation goals, student self-efficacy for reading and reading achievement in intermediate level learners in a rural school district. Walden University. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/807418289.

Webber, C., Wilkinson, K., Andries, V., and McGeown, S. (2022). A reflective account of using child-led interviews as a means to promote discussions about reading. Literacy 56, 120–129. doi: 10.1111/lit.12278

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., and Snyder, W. M. (2002). Seven principles for cultivating communities of practice. Cultivat. Commun. Pract. 4, 1–19.

What Works Clearing House (2008) Accelerated Reader: WWC Intervention Report. IES. Available at: www.http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/interventionreport.aspx?sid=12

*Whittingham, J. L., and Huffman, S. (2009). The effects of book clubs on the reading attitudes of middle school students. Read. Improv., 46, 130–137.

*Whittington, M. (2012). Motivating adolescent readers: a middle school reading fluency and prosody intervention. Trevecca Nazarene University. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1034581714.

Wigfield, A., Gladstone, J. R., and Turci, L. (2016). Beyond cognition: Reading motivation and reading comprehension. Child Dev. Perspect. 10, 190–195. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12184

Wigfield, A., and Guthrie, J. T. (1997). Relations of children's motivation for reading to the amount and breadth or their reading. J. Educ. Psychol. 89:420. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.420

Wigfield, A., Mason-Singh, A., Ho, A. N., and Guthrie, J. T. (2014). “Intervening to Improve Children’s Reading Motivation and Comprehension: Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction,” Motivational Interventions (Advances in Motivation and Achievemen Vol. 18), Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. 37–70. doi: 10.1108/S0749-742320140000018001

Wilkinson, K., Andries, V., Howarth, D., Bonsall, J., Sabeti, S., and McGeown, S. (2020). Reading during adolescence: Why adolescents choose (or do not choose) books. J. Adolesc. Adult. Lit. 64, 157–166. doi: 10.1002/jaal.1065

Willis, A. I. (2002). Dissin'and disremembering: motivation and culturally and linguistically diverse students' literacy learning. Read. Writ. Q. 18, 293–319. doi: 10.1080/07487630290061854