94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 23 January 2024

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1251063

This article is part of the Research TopicSystematic Screening to Support Well-being with PreK-12 StudentsView all 6 articles

Part of this article's content has been mentioned in:

Editorial: Systematic screening to support well-being with PreK-12 students

Kathleen Lynne Lane1*

Kathleen Lynne Lane1* Wendy Peia Oakes2

Wendy Peia Oakes2 Mark Matthew Buckman1

Mark Matthew Buckman1 Nathan Allen Lane1

Nathan Allen Lane1 Katie Scarlett Lane3

Katie Scarlett Lane3 Kandace Fleming4

Kandace Fleming4 Rebecca E. Swinburne Romine4

Rebecca E. Swinburne Romine4 Rebecca L. Sherod1

Rebecca L. Sherod1 Emily Dawn Cantwell5

Emily Dawn Cantwell5 Chi-Ning Chang6

Chi-Ning Chang6Introduction: We report predictive validity of the newly defined Student Risk Screening Scale – Internalizing and Externalizing (SRSS-IE 9, with 9 items) when used for the first time by middle and high school teachers from 43 schools.

Methods: The sample included 11,773 middle school-aged students representing four geographic regions, and 7,244 high school-aged students representing three geographic regions.

Results: Results indicated fall SRSS-IE externalizing and internalizing latent factors as well as subscale scores (SRSS-E5, SRSS-I4, respectively) predicted year-end behavioral (office discipline referrals and in school suspensions) and academic (course failures) outcomes for middle and high school students as well as referrals to special education for middle school students. Internalizing scores also predicted referrals to special education for high school students. Externalizing and internalizing scores predicted nurse visits at the middle and high school levels with all models except for subscale models of internalizing in middle school. SRSS-IE 12 subscale scores for externalizing (SRSS-E7) and internalizing (SRSS-I5) using the original 12 items were similarly predictive of these outcomes, with few variations.

Discussion: We discuss educational implications, limitations, and directions for future inquiry.

Adolescents’ well-being was negatively affected by lifestyle changes necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Many students experienced ongoing periods of lockdowns, school disruptions, lack of access to internet or technology to engage in school and social relationships, increased negative messages on social media, and shifts in access to extracurricular activities. These circumstances likely contributed to students’ feelings of social isolation, exacerbated symptoms of depression and anxiety (Office of the Surgeon General, 2021; Bera et al., 2022), and impacted students’ well-being and academic performance in the aftermath of the pandemic. As such, many educators are confronted with the challenging task of supporting students’ well-being and mitigating learning loss (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2022).

Schools’ interest in the relation of students’ emotional and behavioral well-being and academic achievement is still relatively new and has been propelled by recent findings of student well-being (Lebrun-Harris et al., 2022). For example, in the 1990’s, attending to mental health and well-being gained momentum with increased attention to mental health treatment in the U.S. (Kessler and Merikangas, 2004) which also brought about systems approaches to meeting students’ multiple needs – academic, behavioral, and social and emotional well-being – ideally in an integrated rather than siloed fashion (Lane et al., 2012, 2014; Weist et al., 2017; Gandhi et al., 2023). Research has long explored the relation between students’ emotional and behavioral wellbeing and their academic achievement (Nelson et al., 2004; Agnafors et al., 2021). Findings suggested, regardless of the directionality of the relation (e.g., behavioral challenges leading to academic challenges; academic challenges leading to behavioral challenges), students with co-occurring emotional and behavioral and academic difficulties often have the poorest educational outcomes when not detected early and provided with an appropriate educational response (Agnafors et al., 2021; Walker, 2023). Fortunately, long before the pandemic began, educational leaders had been designing, installing, and evaluating these systems to create positive, productive, and even joyful educational communities. Rather than attempting to prevent and respond to needs in a siloed manner, integrated tiered systems incorporate evidence-based strategies, practices, and programs at each level of prevention: Tier 1 for all, Tier 2 for some, and Tier 3 for a few (Lane et al., 2013a). Tier 1 practices enable general and special educators, administrators, and families to collaborate to prevent learning, behavioral, as well as social and emotional well-being challenges from occurring. Yet, even when Tier 1 practices are in place as planned (e.g., implemented with high levels of treatment integrity; Buckman et al., 2021), some students will need more than Tier 1 has to offer. In these instances, educators implementing integrated tiered systems use systematic screening data to detect students and connect them to validated Tier 2 (e.g., check/in check/out; reading) and Tier 3 (e.g., functional assessment-based; intensive reading instruction; cognitive behavior therapy; Lane et al., 2019b) interventions.

Systematic screening tools play a pivotal role within these integrated systems, providing valid data used to examine the system as a whole, in addition to responding to students’ individual needs by increasing schools’ early detection efforts (Walker and Severson, 1992). While some educators and families may wonder if early detection efforts are necessary in middle and high schools, prevalence estimates suggest a very real need and in fact, an even greater need since the pandemic (Lebrun-Harris et al., 2022).

Prior to the pandemic, point prevalence estimates showed between 12 and 20% of school-aged students experienced mild to moderate forms of emotional and behavioral disorders (Forness et al., 2012). Similarly, more than 1 in 5 adolescents (22%) experienced mental health difficulties (Merikangas et al., 2010). Secondary school represents an important time for adolescents with these difficulties to be detected and appropriate interventions provided to minimize long-term impact of these challenges into adulthood (Colman et al., 2007). A meta-analysis of the effects of COVID-19 on the mental health of students under age 18 indicated the magnitude of the problem has increased since the onset of the pandemic with a prevalence of 31% experiencing depressive symptoms and 31% experiencing anxiety symptoms (Deng et al., 2023).

Given the challenges secondary-aged students with emotional and behavioral difficulties face within and beyond school settings, and data indicating prevalence of these difficulties has increased in the context of the pandemic – systematic screening is necessary. Fortunately, many educators and families are prioritizing the adoption of feasible and psychometrically-sound tools for the early detection of students with externalizing and internalizing behaviors, which are at the core of major disorders of childhood and adolescence (Lane et al., 2021). One such tool, available to K-12 schools, is the Student Risk Screening Scale for Internalizing and Externalizing (SRSS-IE; Drummond, 1994; Lane and Menzies, 2009) – one of the few remaining free-access screening tools available for use in secondary schools. Free access indicates the tool is free for schools to download and use. Yet, resources are needed for implementing the SRSS-IE such as personnel time to build the data collection method and manage data for educators use. Also, while minimal training is needed to complete the SRSS-IE, there are investments needed in professional learning for educators to use behavioral data alongside other school data for instructional decision making (Lane et al., 2023). In this paper, we extend the inquiry on the SRSS-IE for use with middle and high school students.

In the initial validation study for the SRSS-IE with middle school students, (N = 937) from three schools (two city, one rural), Lane et al. (2013b) conducted an exploratory factor analysis, estimated internal consistency, and assessed criterion-related validity with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997). The initial 14 items (SRSS-IE 14) comprised two factors nearly as expected and accounted for 41% of the variance. Two items did not load well onto the internalizing factor and were removed for empirical and theoretical reasons resulting in 12 items (SRSS-IE 12) yielding two factors – internalizing and externalizing – which account for 19 and 27% of the variance, respectively, with a total of 47% variance recovered. The externalizing factor (SRSS-E7) demonstrated higher internal consistency than the internalizing factor (SRSS-I7, SRSS-I5): SRSS-E7 α = 0.85, SRSS-I7 α = 0.67, SRSS-I5 α = 0.74. The externalizing subscale score was significantly correlated with all SDQ subscales (e.g., conduct problems subscale, r = 0.80) and total score (r = 0.76). Internalizing subscale scores were statistically significantly correlated with the SDQ total difficulties score (r = 0.39), emotional symptoms subscale (r = 0.53), and peer problems subscale (r = 0.49). Overall, the 12-item instrument appeared promising for screening in secondary schools.

Later studies conducted with middle and high school students found similar estimates of internal consistency for the externalizing factor (α = 0.82–0.84), slightly greater estimates for internalizing (α = 0.77–0.81), and slightly greater overall consistency estimates (α = 0.83–0.86; Lane et al., 2017, 2019c; Moulton et al., 2019). Another exploratory factor analysis found improved fit by allowing one item, peer rejection, to cross-load on both factors resulting in the SRSS-E7 and SRSS-I6 subscales (Lane et al., 2017). Additional studies further substantiated the evidence for criterion-related validity with the SDQ (Jones et al., 2020) and established evidence for criterion-related validity with the Behavior Assessment System for Children–2nd Edition (BASC-2) Behavioral and Emotional Screening System (BESS; Kamphaus and Reynolds, 2007; Lane et al., 2019d).

In addition, studies have established predictive validity of SRSS and SRSS-IE studies in middle and high schools primarily using variations of linear regression and group comparisons by risk level. For example, prior to the development of the SRSS-IE (which includes the same 7 items developed by Drummond (1994) to assess externalizing behaviors), the original SRSS scores in fall predicted behavioral and academic outcomes in middle (Lane et al., 2007) and high schools (Lane et al., 2008). Lane et al. (2007) reported findings from two studies conducted with middle school students in rural (n = 500) and urban (n = 528) settings, respectively. In addition to establishing evidence indicating high internal consistency, test-re-test stability, and convergent validity with SDQ scores, results of both studies indicated middle students with low, moderate, and high risk according to fall SRSS scores could be differentiated by ODRs and in-school suspensions, with higher levels of risk indicative of higher numbers of each outcome. Also, students beginning the academic year with lower levels of risk, had higher GPAs, and failed fewer classes relative to students beginning the year in moderate or high-risk categories. Lane et al. (2008) reported similar outcomes for score reliability and predictive validity with a sample 674 high school students, with students at low risk differentiated on ODRs and GPA from students with moderate and high-risk across two academic years.

Predictive validity studies of SRSS-IE subscale scores continued to establish predictive validity with fall SRSS-E7 (externalizing) and SRSS-I6 (internalizing) scores predicting important year-end outcomes: behaviorally and academically (Lane et al., 2019c; Gregory et al., 2021). For example, Lane et al. (2019c) examined predictive validity of SRSS-E7 and SRSS-I5 scores with middle (N = 2,313) and high (N = 2,727). Results indicated students with high levels of risk according to fall SRSS-IE subscales scores – particularly externalizing behaviors – spent more time in in-school suspensions, failed more courses, and earned lower GPAs compared with students in low-risk categories.

Overall, scores on the externalizing scale have repeatedly demonstrated predictive relationships of end of year outcomes, and initial evidence suggests fall SRSS-I6 predict important outcomes in secondary settings. Yet, less is known about the predictive utility of the internalizing scale in secondary settings.

Recognizing systematic screening as an essential feature of tiered systems, with these data used along with other data collected as part of predictable school practices to shape instructional experiences for students, we conducted Project SCREEN. Project SCREEN is an Institute of Education Sciences (IES) funded measurement grant to advance the current literature base by extending the examining psychometric evidence of the SRSS-IE 12 for use with K-12 students. Our intent was to offer professionals information to inform selection and installation of systematic screening tools and practices. We focused on the SRSS-IE 12 given there is currently no financial support for this tool to enable on-going psychometric analyses.

The first Project SCREEN study examined the factor structure, reliability, and measurement invariance of SRSS-IE 12 scores with a sample of K-12 students from 87 schools representing four U.S. geographic regions collected over a 10-year period (Lane et al., 2023). All schools were in their first year of administering the SRSS-IE 12. Confirmatory factor analyses adjusting the standard errors using a sandwich estimator to account for the nested nature of the data yielded a two-factor structure: internalizing and externalizing with three items removed to optimize model fit (peer rejection, item 4; low academic achievement, item 5; and shy, withdrawn, item 9). In short, results yielded the SRSS-IE 9. However, authors urged educators not to shift screening practices until replication occurs with other samples, particularly schools who are beyond the initial installation year. Yet, preliminary findings yielded clear evidence of measurement invariance across gender, race, ethnicity, and special education status within elementary, middle, and high school levels. Within school level model comparisons in fall, winter, and spring between configural, metric, scalar, and strict models met invariance criteria. The same was true for longitudinal models, meeting invariance criteria for elementary, middle, and high school samples. These collective findings are important, suggesting scores produced by teachers new to screening with the SRSS-IE were consistent across various subgroups of students (e.g., evidence of full measurement invariance, demonstrating similar factor structure and levels of behavior rated; Lane et al., 2023). Following this study, authors further examined and established predictive validity of the SRSS-IE 9 scores and SRSS-IE 12 scores in predicting students’ outcomes at the elementary level (Lane et al., 2023). Now, it is necessary to examine predictive validity in secondary schools.

We extended inquiry of the SRSS-IE 9 and SRSS-IE 12 recently conducted at the elementary level (Lane et al., in press), addressing two objectives. First, we conducted predictive validity analyses of SRSS-IE 9 scores with middle and high school students. The SRSS-IE 9 is an adapted, more parsimonious version featuring nine items: five to assess externalizing (SRSS-E5) and four to assess internalizing (SRSS-I4). Following the same data analytic plan applied with elementary students, we examined predictive validity of fall externalizing and internalizing scores by analyzing the degree to which fall scores for middle (grades 5–8) and high (grades 9–12) school students screened by teachers using the SRSS-IE for the first-time predicted year end behavioral (ODRs, suspensions, nurse visits,) and academic (course failures) outcomes according to extant school-wide data. We also analyzed the extent to which fall scores predicted referrals to special education, which has not yet been examined in earlier SRSS and SRSS-IE inquiry in secondary schools. We began by using new latent factors for externalizing and internalizing behaviors derived from the reduced items (Lane et al., 2023) as a rigorous psychometric analysis of how the latent constructs are related to students’ year-end outcomes. Second, given educators are currently making instructional decisions using externalizing and internalizing subscale scores (calculated by summing individual items without weighting), we also examined predictive validity of fall externalizing (SRSS-E5) and internalizing (SRSS-I4) subscale scores in predicting these same outcomes.

Lastly, given many school systems currently use SRSS-IE 12 (Drummond, 1994; Lane and Menzies, 2009) subscale scores for externalizing (SRSS-E7) and internalizing (SRSS-I5) as part of data-informed decision-making practices, we analyzed predictive validity of these subscale scores as previously calculated as well. We viewed this step to be important to provide assurances these scores (SRSS-E7 and SRSS-I5) predict important school outcomes while we complete the programmatic, psychometric evaluation of the reduced scales (Lane et al., 2023). As such, we calculated raw sum scores using the full item set to replicate and extend previous predictive validity analyses of SRSS-IE 12 scores with this large, geographically diverse sample of first year screening. In addition to focusing on end-of-the year outcomes for ODRs, suspensions, nurse visits, and course failures as in years past, we also expanded the scope of end-of-the year outcomes by examining referrals for special education services.

Based on previous associations between SRSS-IE 12 scores and student outcomes in smaller samples as well as findings at the elementary level (Lane et al., in press), we hypothesized SRSS-IE 9 fall scores would be associated with outcomes indicating predictive validity, with externalizing scores demonstrating stronger relations with the behavioral outcomes (e.g., ODRs, suspensions, and nurse visits) than academic outcomes (course failures), yet still predictive of the latter given the established relation between challenging behavior and academic under achievement (Hinshaw, 1992; Nelson et al., 2004). We anticipated a smaller-magnitude predictive relation for course failures, as academic performance is a distinct construct from behavioral challenges (Berry, 2015). Finally, based on findings from new predictive validity analyses at the elementary level, we anticipated middle school students’ fall screening scores for internalizing behaviors would be slightly more predictive of special education referrals than externalizing scores. We did not expect to establish predictive validity for special education referrals at the high school level, as referrals to determine special educational eligibility typically take place earlier in students’ educational careers.

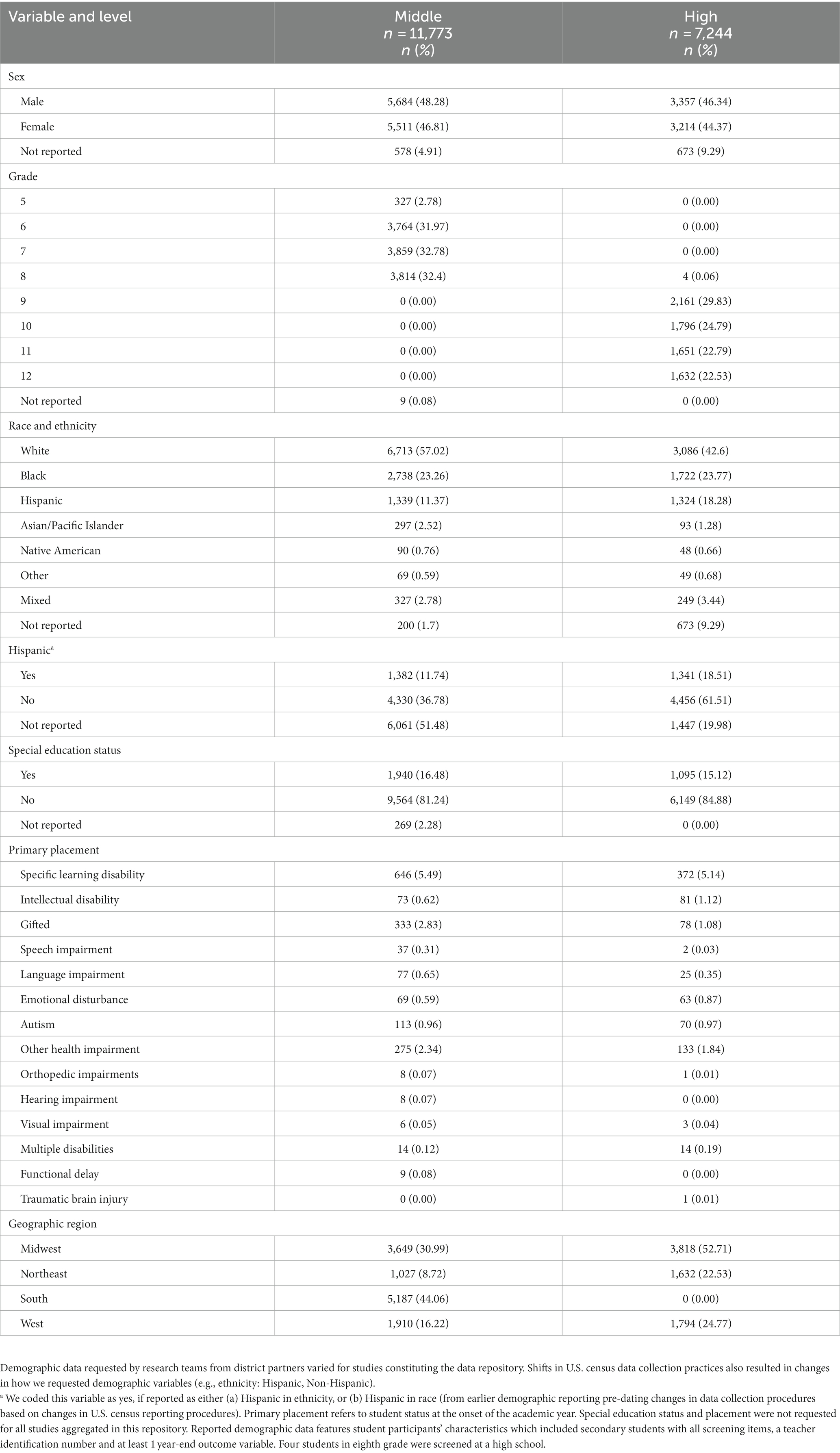

Participants included 11,773 middle (sixth- through eighth-grade) and 7,244 high (ninth- through twelfth-grade) school students from 43 schools in the United States between the 2009–2010 and 2019–2020 academic year (see Table 1 for participant characteristics, and Supplementary Table S1 for teacher rater characteristics). The sample included middle school-aged students from four geographic regions, and high school-aged students from three geographic regions according to U.S. Census. Thus, the middle and high school samples featured the three regions and exceeded sample size recommendations (minimum of 150 students) provided by National Center on Intensive Intervention (2017/2022) to promote generalizability. The sample included data from 22 schools from the Midwest (KS = 12, MO = 10), 4 from the Northeast (PA = 2, VT = 2), 7 from the South (TN = 7), and 10 schools from the West (AZ = 10). Supplementary Table S2 reports school characteristics by geographic region.

Table 1. Characteristics of middle and high school students with fall SRSS-IE externalizing and internalizing, teacher identification numbers, and at-least 1 year-end outcome measure.

Procedures for the current study are identical to those reported by (Lane et al., in press, 2023), examining predictive validity of SRSS-IE scores at the elementary level. We briefly summarize procedures here. We analyzed data for middle and high school students for this current sample from a de-identified data repository created as part of Project SCREEN, a measurement grant funded by IES. IES funded Project SCREEN, with the main objective to re-analyze SRSS-IE data collected from 20 IRB-approved studies conducted across four geographic locales using current standards (National Center on Intensive Intervention, 2017/2022). Results from initial studies are featured in a range of peer-reviewed outlets (e.g., Assessment, Evaluation, and Intervention; Behavioral Disorders; and Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders). Studies spanned the 2009–2010 through 2019–2020 academic years, with all studies involving item-level SRSS-IE data and many requesting and receiving basic student-level characteristics (e.g., sex, school-level, grade-level, race and ethnicity, special education status, and/or primary placement if receiving services). Changes to the U.S. census data collection practices informed changes in our demographic variables (e.g., ethnicity: Hispanic, Non-Hispanic) over the 10-year span. Some study protocols included collecting student-level, year-end outcomes which are the focus of those analyses presented in this manuscript designed to provide evidence supporting predictive validity. Common variables collected for middle and high school students include number of ODRs earned (count), number of in-school suspensions (count), number of nurse visits (count), number of course failures (count), and/or special education referrals (binary: yes/no). As noted in the elementary paper (Lane et al., in press): year-end outcomes requested and received varied by study and district agreements. Overall, student-level missingness of demographic, screening, and year-end variables requested and received for each approved study was small in magnitude as districts provided all available data they were comfortable sharing. Each outcome received, was shared for all students enrolled in the participating school. Requested and received variables varied across studies. As such, we conducted predictive validity analyses for all participants with a teacher identification number for the teacher who completed the SRSS-IE, who had complete screening data in the fall, with at least 1 year-end outcome. This resulted in different numbers of student participants for each year-end outcome model.

The screening repository also included limited teacher demographic data, particularly from studies conducted at the beginning of the 11-year span. Similar to student-level data collection procedures, teacher-level data collection procedures varied across studies according to specific study procedures (see Supplementary Table S1).

After receiving IRB approval to construct the Project SCREEN data repository, data files were reviewed for additional accuracy and quality checks (keeping in mind these procedures were done previously as part of previous protocols). We conducted logic checks and cleaned files before conducting the master data merge using SAS. After completing the master data merge, project staff conducted a series of additional checks to ensure accuracy (e.g., inclusion of appropriate studies). We prepared demographic tables using SAS programming. All models were analyzed using MPLUS.

The sample analyzed in this paper included: (a) student-level SRSS-IE fall data completed by teachers in schools in their first year of SRSS-IE implementation for students attending secondary schools (middle and high school), and (b) data from projects in which we requested and received year-end, student-level outcomes variables. As part of our programmatic line of screening inquiry, we intend to seek funding to replicate these analyses using repository data from middle and high school teachers using the SRSS-IE beyond the initial installation.

Our research team is committed to Open Sciences practices (Cook et al., 2022). Yet, district data sharing agreements prohibit these particular screening data from any form of data sharing – even de-identified data.

The SRSS-IE 12 is a free-access, universal screening tool completed by teachers three times per year to identify students with internalizing and externalizing behavior patterns. Teachers independently complete the SRSS-IE 12 for each student in their class, or during a specific period for secondary students. The SRSS-IE 12 is an expansion of the seven-item Student Risk Screening Scale (SRSS) created by Drummond (1994) which included (1) steal; (2) lie, cheat, sneak; (3) behavior problems; (4) peer rejection; (5) low academic achievement; (6) negative attitude; (7) aggressive behavior. The SRSS-IE contains an additional 5 questions for internalizing behaviors: (8) emotionally flat; (9) shy, withdrawn; (10) sad, depressed; (11) anxious; and (12) lonely. Each item is rated on a 4-point, Likert-type frequency scale: 0 = never, 1 = occasionally, 2 = sometimes, and 3 = frequently as developed by Drummond (1994).

Traditionally, procedures for scoring at the middle and high school level involved summing the seven original externalizing items to form the SRSS-E7 subscale score and summing the five internalizing items and the peer rejection item to form the SRSS-I6 subscale score. Educators used subscale scores to place secondary students into the following categories: (a) SRSS-E7: low- (0–3), moderate- (4–8), or high-risk (9–21) for externalizing behaviors as defined by Drummond (1994) and (b) SRSS-I6: low- (0–3), moderate- (4–6), or high-risk (7–18) for internalizing behaviors (Lane et al., 2016).

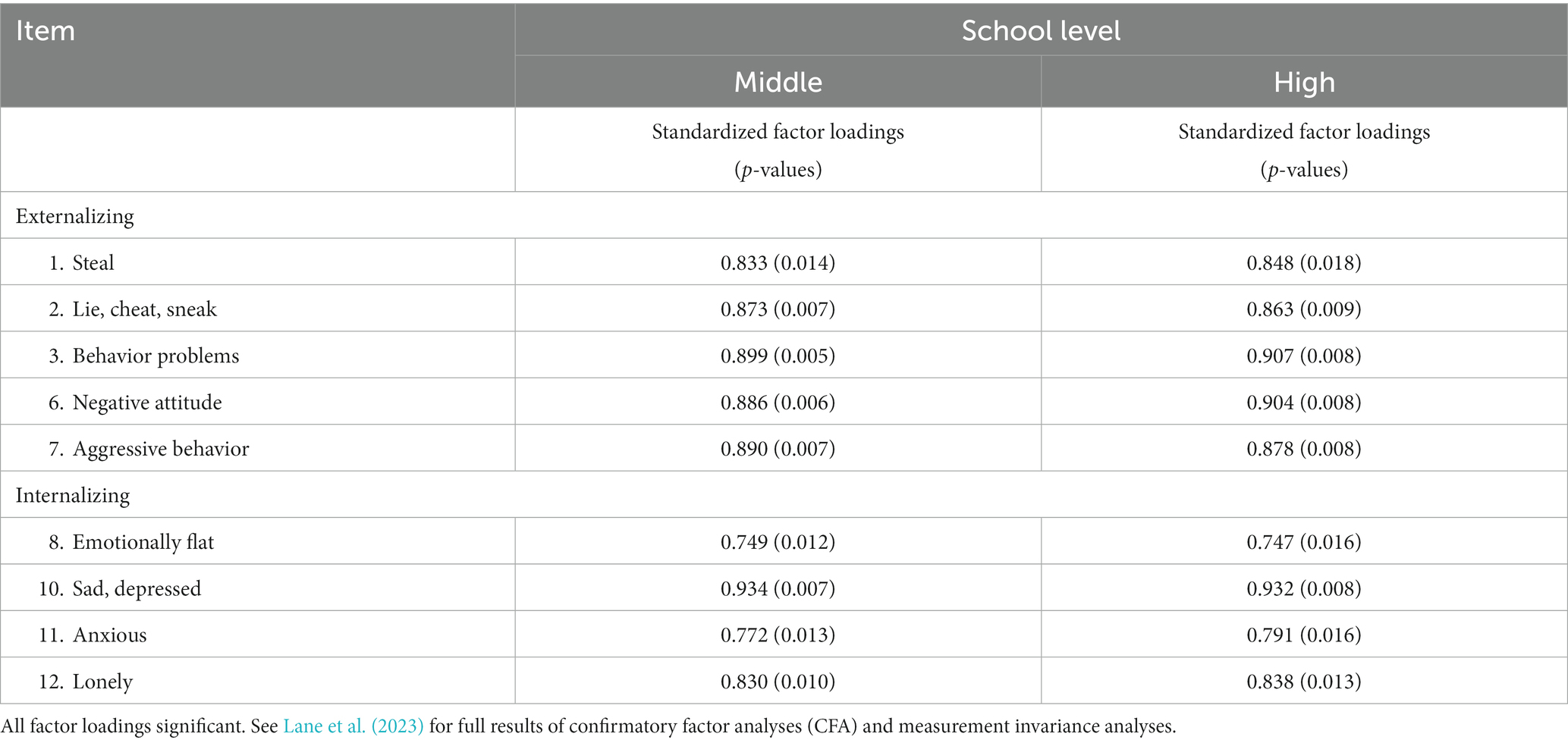

Recent analyses offer preliminary evidence of an updated version of the SRSS-IE 12- the SRSS-IE- 9, pending replication. Specifically, results of a confirmatory factor analyses with adjusted standard errors to account for the nesting of students within teachers conducted by Lane et al. (2023) indicated a reduced set of items to measure externalizing and internalizing behavior constructs yielded a better model fit at the middle (i.e., fall timepoint RMSEA = 0.048, CFI = 0.974, SRMR = 0.061) and high school level (i.e., fall timepoint RMSEA = 0.052, CFI = 0.967, SRMR = 0.055). See Table 2 for standardized factor loadings for externalizing and internalizing constructs for middle and high school levels from Lane et al. (2023), with all factor loadings statistically significant at p < 0.0001. Reduced versions of each subscale for elementary, middle, and high – now the SRSS-E5 and SRSS-I4 – constitute the proposed SRSS-IE 9. However, Lane et al. (2023) strongly recommended educational leaders not shift to the SRSS-IE 9 version until replication studies have been conducted (e.g., with other initial implementers, samples comprised of teacher in later stages of SRSS-IE installation).

Table 2. Standardized factor loadings for externalizing and internalizing constructs: middle and high school levels.

We conducted the current set of analyses designed to provide evidence of predictive validity using the same two approaches with SRSS-IE 9 scores conducted at the elementary level (Lane et al., in press). First, we used item level responses in structural equation models accounting for the nesting of students within teachers to examine the relation between the SRSS-IE 9 latent externalizing (SRSS-E5, 5 items) and internalizing (SRSS-I4, 4 items) factors and student outcomes (variables to follow). Second, using similar models accounting for nesting of students within teachers, we used SRSS-IE externalizing (SRSS-E5) and internalizing (SRSS-I4) subscale scores calculated by summing the items given this is the current approached use by in-service educators. Namely, they use subscale scales scores to inform instruction. In addition, we conducted a final analysis of the SRSS-IE 12 scores, using externalizing (SRSS-E7) and internalizing (SRSS-I5) subscale scores with this same sample as the SRSS-IE 12 is currently used by many school systems as part of their tiered system of support. We conducted this latter set of analyses accounting for the nesting of students within teachers to provide these educators with information on the predictive validity of the SRSS-IE 12.

As noted previously, the repository included a range of end-of-year student outcome measures. In this study, we examined five outcome variables: (a) office discipline referrals (ODRs; i.e., the total number of major office discipline referrals earned during the year), (b) suspensions (i.e., the total number of in-school suspensions earned during the academic year), (c) nurse visits (i.e., the total number of nurse visits made during the academic year, noting students could make more than one visit per day [e.g., dispensing medications]); (d) course failures (i.e., the number of Ds or Fs earned during the academic year), and (e) referrals to special education (i.e., whether or not a student was referred to a multi-disciplinary team to determine special education eligibility [yes or no; outcomes not included]).

Participating schools and districts provided de-identified student demographic information. Requested information included sex (male or female, initially collected using the term gender), grade level, race (White, Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, other, or mixed race), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), and special education status (yes or no) at the onset of the school year. For students beginning the academic year receiving special education service, we requested primary eligibility category codes as defined by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, 20 U.S.C. 1400 et seq, 2004; Table 1).

Most study procedures requested teachers to self-report their demographic characteristics. We requested nominal teacher information. In recent years, we requested more detailed teacher characteristics such as role, educational attainment, age, and years of experience teaching.

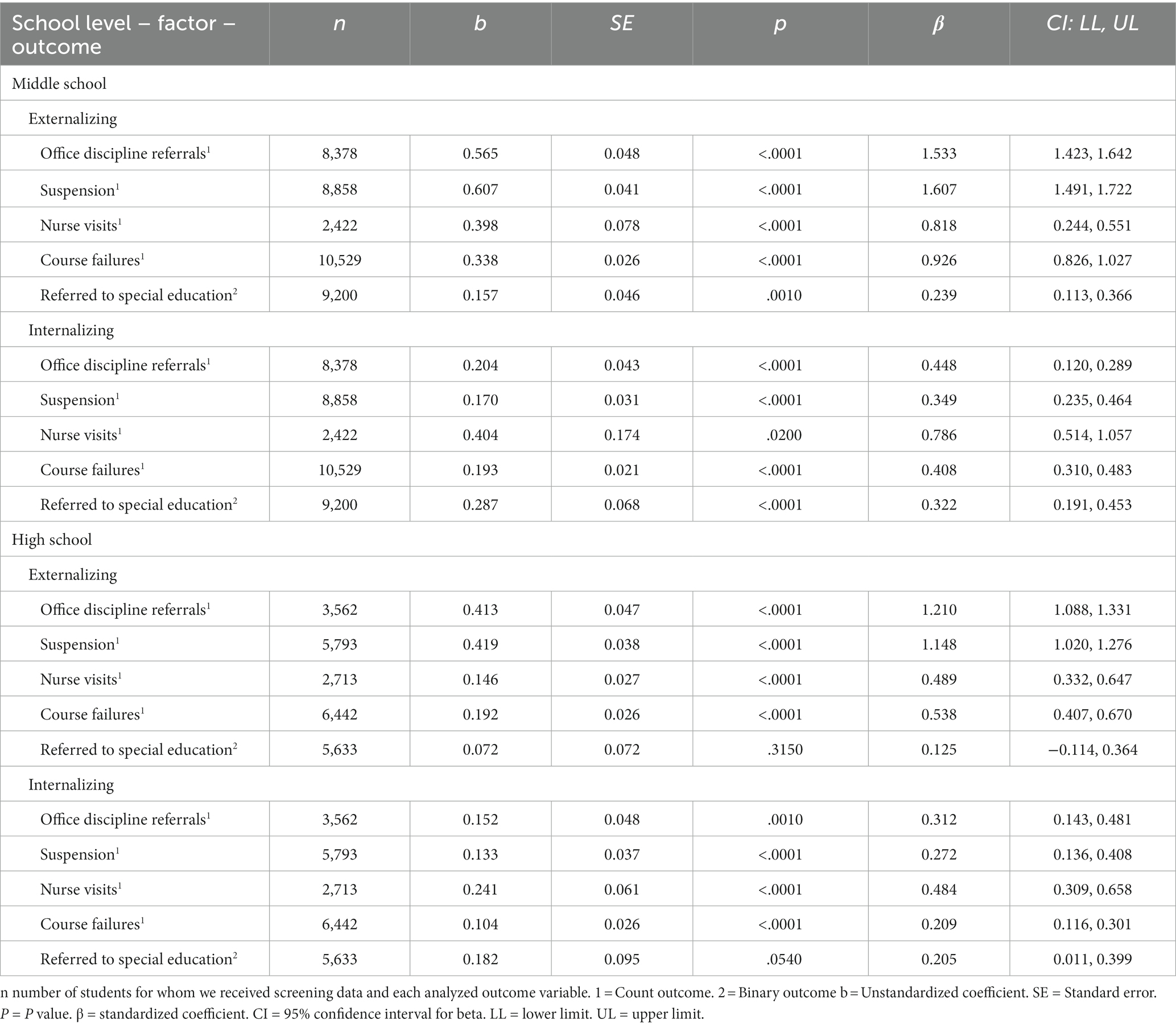

We followed the same data analytic plan employed by Lane et al. (2023) examining evidence for predictive validity at the elementary level, accounting for the hierarchical nature of the data (i.e., secondary students nested within teachers’ classrooms, teachers’ rating multiple students). Specifically, we used a design-based approach to correct the underestimated standard errors by including the Type = Complex routine in Mplus 8.6 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017; Wu and Kwok, 2012) which adjusts the standard errors using a sandwich estimator. The SEM model examined how well each SRSS-IE 9 latent factor (externalizing or internalizing behavior) predicted each year-end student outcome measure (see Table 3). In the first set of models, a latent factor for each construct (externalizing or internalizing behavior) served as the predictor. We computed separate models for each of the five outcomes: ODR, suspensions, nurse visits, course failures, and referrals to special education. We used different estimation approaches for count and binary outcomes. Specifically, for count outcomes (i.e., ODR, suspensions, nurse visits, and course failures), a negative binomial model with an overdispersion parameter was used. We fit negative binomial regression models given distributions for these variables approximated a Poisson distribution (meaning many students had scores of zero). For the one binary outcome (special education referrals), we employed maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR) estimation for categorical outcomes. In this sample of secondary students from the data repository, 19,017 observations were available (i.e., included all screening items, at least one outcome measure, and the teacher identification number to allow for nesting; Table 1).

Table 3. Fall SRSS-IE 9 externalizing and internalizing latent factors predicting year-end outcomes for middle and high students.

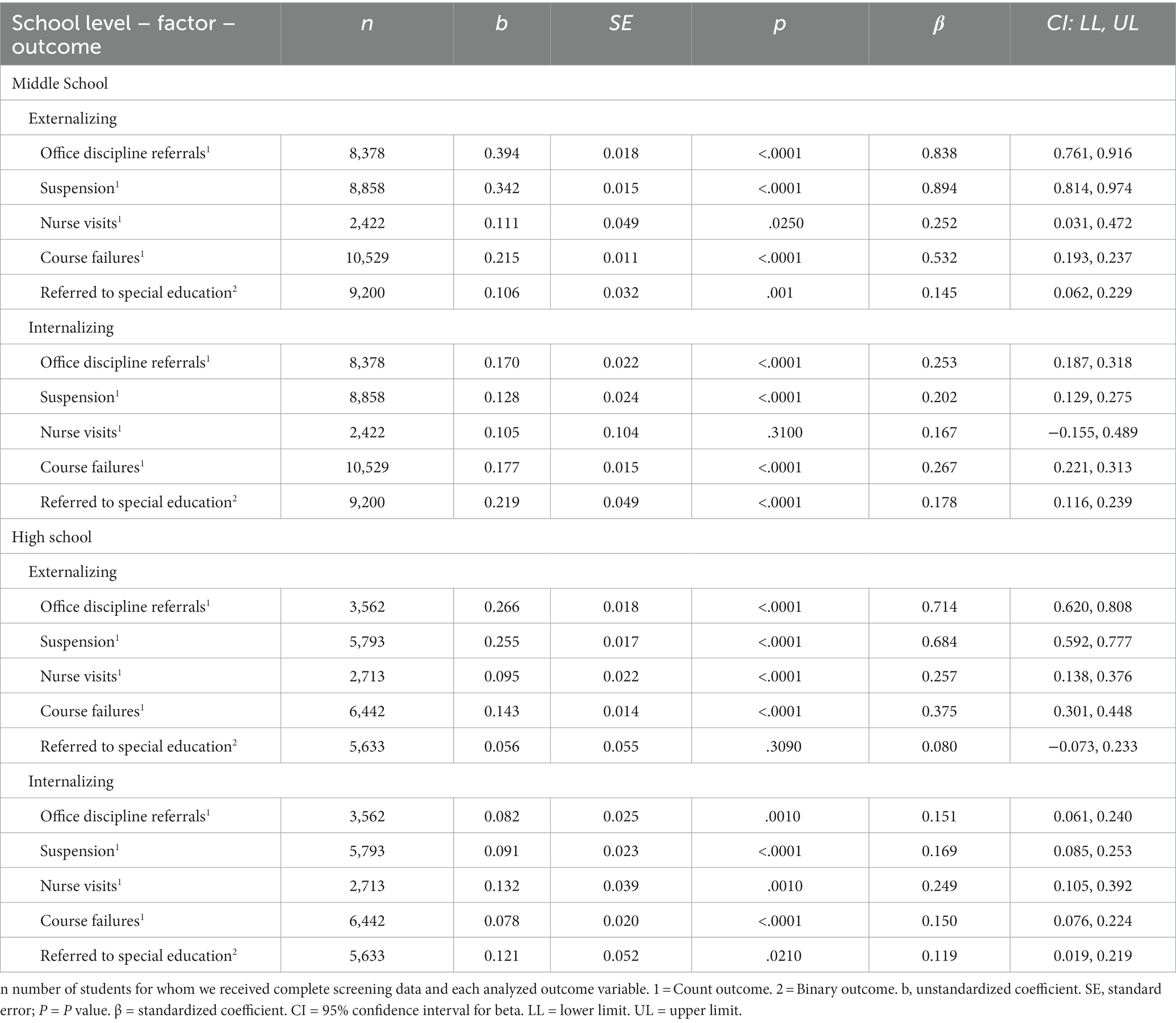

Second, we conducted additional SRSS-IE 9 analyses to provide information about subscale scores that support predictive validity, while also accounting for the nested data structure. Specifically, we evaluated five parallel SEM models (one for each outcome variable) using the summed subscale scores for externalizing (SRSS-E5) and internalizing (SRSS-I4) to predict outcomes (Table 4) rather than the latent factors. For count outcomes we again specified a negative binomial model with an overdispersion parameter. For binary outcomes, we employed maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR) estimation for categorical outcomes.

Table 4. Fall SRSS-IE 9 externalizing and internalizing subscales predicting year-end outcomes for middle and high students.

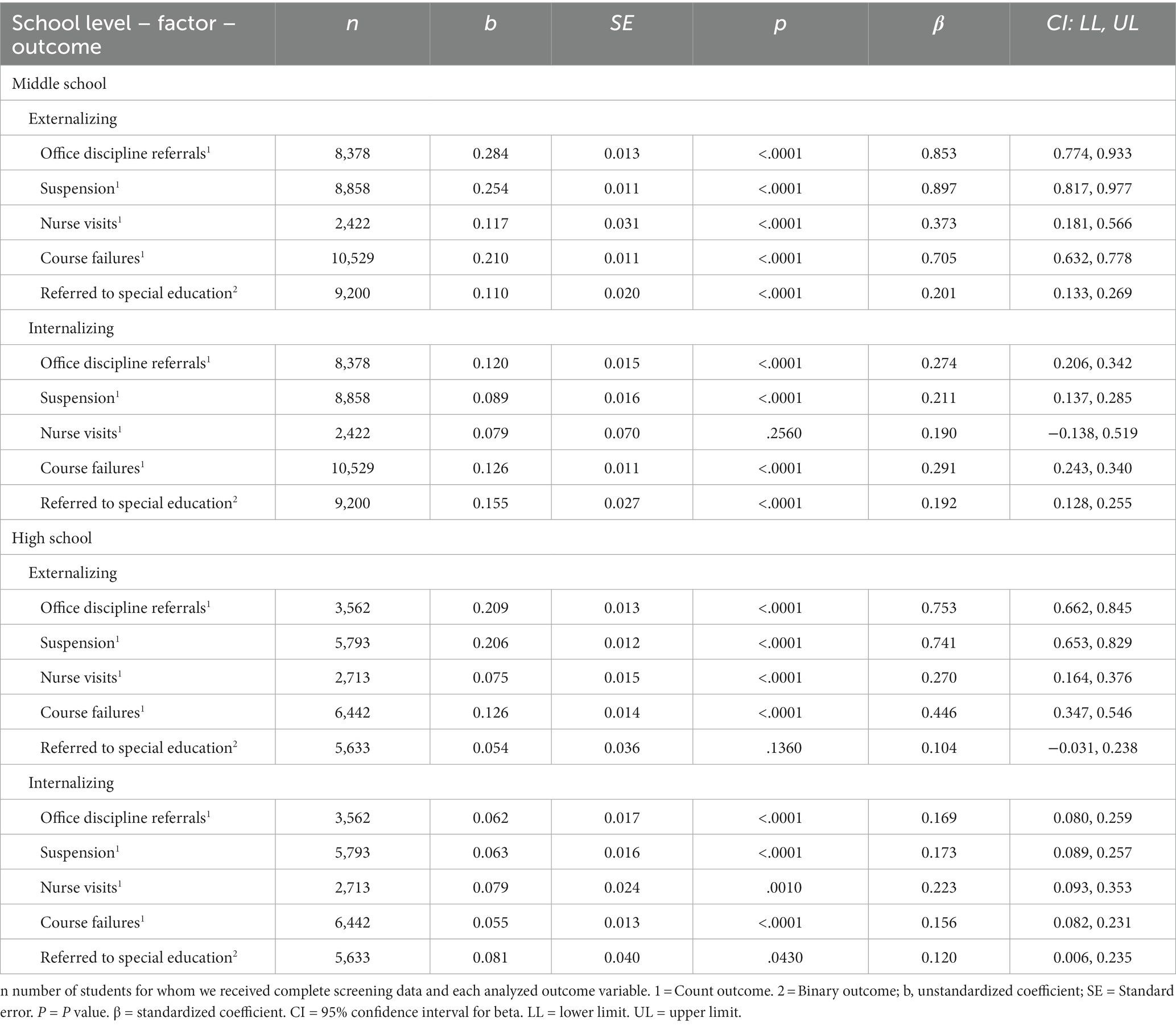

Third, we conducted an additional set of analyses with the SRSS-IE 12 subscale scores (externalizing [SRSS-E7]; internalizing [SRSS-I6]) used in the SEM models as many secondary schools are currently using the SRSS-IE 12 (see Table 5). Our goal was to provide evidence to inform current screening practices using SRSS-IE 12 data to predict important year end outcomes. Again, we urge practitioners to not use SRSS-IE 9 scoring until we conclude our planned psychometric evaluation of the reduced scales (Lane et al., 2023).

Table 5. Fall SRSS-IE 12 externalizing and internalizing subscales predicting year-end outcomes for middle and high students.

For all three sets of models, we reported raw b weights as well as standardized beta weights for all models. We interpreted standardized coefficient (β) effect sizes values using Chen et al. (2010) and Fey et al. (2022) who indicate <0.30 is small, 0.30–0.49 is medium, and >0.50 is large.

For all models, the fall externalizing factor significantly predicted middle school students’ end-of-year outcomes, with most models significant at p < 0.0001 levels (Table 3). Results indicated large effects for fall externalizing for ODR (B = 1.533), suspensions (B = 1.607), nurse visits (B = 0.818), and course failures (B = 0.926). Fall externalizing factor scores predicted referrals to special education, with a small effect (B = 0.239).

Similarly, the fall externalizing subscale score (SRSS-E5) significantly predicted middle school students’ end-of-year outcomes (Table 4). Results indicated large effects for fall externalizing on ODR (B = 0.838), suspensions (B = 0.894), and course failures (B = 0.532), and small effects for nurse visits (B = 0.252) and referrals to special education (B = 0.145).

For all models, the fall internalizing factor significantly predicted middle school students end-of-year outcomes with all models significant at p < 0.0001 levels except nurse visits (p = 0.0200; Table 3). Results indicated large associations with nurse visits (B = 0.786) and medium associations with ODR (B = 0.448), suspensions (B = 0.349), course failures (B = 0.408), and referrals to special education (B = 0.322).

Similarly, fall internalizing subscale scores (SRSS-I4) significantly predicted middle school students’ end-of-year outcomes (Table 4). Results indicated small significant associations with ODR (B = 0.253), and suspensions (B = 0.202), course failures (B = 0.267), referrals to special education (B = 0.178). The association with nurse visits (B = 0.167) was not significant, p = 0.3100; however, the standardized beta weight indicated a small association comparable to other variables significantly predicted by fall internalizing scores.

For the original fall externalizing subscale score (SRSS-E7) significantly predicted middle school students’ end-of-year outcomes, with all models significant at p < 0.0001 levels (Table 5). Results indicated large associations with ODR (B = 0.853), and suspensions (B = 0.897), and course failures (B = 0.705). In addition, results yielded medium associations with nurse visits (B = 0.373) and small associations with referrals to special education (B = 0.201).

The original the fall internalizing subscale score (SRSS-I6) significantly predicted middle school students’ end-of-year outcomes at the p < 0.0001 level for all outcomes, except for nurse visits (B = 0.190, p = 0.2560; Table 5). Results indicated small associations with ODR (B = 0.274), and suspensions (B = 0.211), course failures (B = 0.291), and referrals to special education (B = 0.192).

The fall externalizing factor significantly predicted all high school students’ end-of-year outcomes, except for referred to special education (B = 0.125, p = 0.3150; Table 3). Results indicated large associations with ODRs (B = 1.210), suspensions (B = 1.148), and course failures (B = 0.538) as well as a medium association with nurse visits (B = 0.489).

Similarly, the fall externalizing subscale score (SRSS-E5) significantly predicted most high school students’ end-of-year outcomes at the p < 0.0001 except for referrals to special education (B = 0.080, p = 0.3090; Table 4). Results suggested large associations for ODR (B = 0.714) and suspensions (B = 0.684). A medium association was observed with course failure (B = 0.375) and a small association with nurse visits (B = 0.257).

The fall internalizing factor significantly predicted high school students’ end-of-year outcomes, except referral to special education which yielded a value of p of 0.054, (B = 0.205). Effects were medium for ODR (B = 0.312) and nurse visits (B = 0.484) as well as a small association with suspensions (B = 0.272) and course failures (B = 0.209).

The fall internalizing subscale score (SRSS-I4) significantly predicted all end-of-year outcomes for high school students. All effects were small for ODR (B = 0.151), suspensions (B = 0.169), and nurse visits (B = 0.249), course failures (B = 0.150), and referrals to special education (B = 0.119).

The original scoring for fall externalizing subscale score (SRSS-E7) significantly predicted high school students’ end-of-year outcomes at p < 0.0001 levels, with the exception of referred to special education significant which was not significant (B = 0.104, p = 0.1360). Results indicated large associations with ODR (B = 0.753) and suspensions (B = 0.741), medium associations with course failures (B = 0.446), and small associations with nurse visits (B = 0.270).

The fall internalizing subscale score as originally calculated (SRSS-I6) significantly predicted high school students’ end-of-year outcomes for high school students. Results indicated small associations for all outcomes ODR (B = 0.169), suspensions (B = 0.173), nurse visits (B = 0.223), course failures (B = 0.156), and referral to special education (B = 0.120).

Results indicated statistically significant relations between externalizing behavior and middle and high school student outcomes, regardless as to which scoring method is used – with the exception of referrals to special education and nurse visits. As hypothesized, fall externalizing behaviors were predictive of referrals to special education at the middle school level, but not at the high school level. However, fall internalizing behavior patterns did predict referrals to special education at the middle and high school level. In addition, as hypothesized, middle school students’ fall screening scores for internalizing behaviors were slightly more predictive of special education referrals than externalizing scores for SRSS-IE 9 models using both approaches, but not so for SRSS-IE 12 scores with high comparable standardized coefficient values (externalizing, β = 0.201; internalizing, β = 0.192). Interestingly, fall externalizing behaviors were predictive of nurse visits according to all scoring methods for middle and high school samples. However, there were differences with respect to internalizing scores. Fall internalizing behaviors predicted nurse visits using all scoring methods. However, at the middle school level, only the latent score approach predicted nurse visits.

Systematic screening is a central practice for educators to detect and support all students – including secondary-age students – at the first sign of concern as well as responding effectively when challenges arise. Perhaps now more than ever, in the wake of the pandemic, educational leaders need access to psychometrically sound, practical tools for detecting both major emotional and behavioral disorders: externalizing and internalizing behavior patterns (Lane et al., 2021). Project SCREEN was funded to provide necessary information for the educational community on the evidence supporting score reliability and the validity of inferences based on the SRSS-IE: one of the few free access tools designed for use within tiered systems to inform instruction.

Initial studies conducted as part of Project SCREEN have established (a) score reliability and measurement invariance of the SRSS-IE across the K-12 continuum (Lane et al., 2023) and (b) evidence for predictive validity at the elementary level (Lane et al., in press), of the new SRSS-IE 9. In this study, we provide additional evidence of predictive validity of the SRSS-IE 9 and SRSS-IE 12 for middle and high school students, building upon previous inquiry exploring predictive validity of SRSS-IE 12 subscale scores in secondary schools (e.g., Lane et al., 2017, 2019c; Jones et al., 2020).

We explored evidence of predictive validity of SRSS-IE 9 scores (SRSS-E5 for externalizing, SRSS-I4 for internalizing) using two approaches: latent variables and subscale scores, with the latter approach currently used in practice by educators to inform instruction (Lane et al., 2019b). For both approaches, results indicated fall externalizing and internalizing scores were associated with middle school students’ end of year outcomes, predicting ODRs, suspensions, course failures, and referrals to special education. Surprisingly, only the latent factor models resulted in fall internalizing behavior predicting nurse visits and not the subscale models. This later finding was surprising given previous studies reported internalizing behaviors measured by the SRSS-IE 12 (specifically, the internalizing subscale scores) predicted the number of year end nurse visits, with students visiting the nurse sometimes multiple times a day for a range of reasons (e.g., intensive medical needs, daily medication needs, or somatic complaints; Saps et al., 2009). Similar to studies conducted with elementary students, latent factors yielded slightly stronger evidence of predictive validity on most outcomes compared to the subscale method (Lane et al., in press). These findings were comparable to previous predictive validity models conducted at the middle school level, with the original SRSS items (SRSS-E7) score predicting important behavioral (e.g., ODR, in-school suspensions) and academic (e.g., GPA, course failures) year-end outcomes (e.g., Lane et al., 2007, 2019c) and the SRSS-IE 6 internalizing subscale score also predicting year-end outcomes (e.g., Lane et al., 2016, 2019c; Gregory et al., 2021).

Given early inquiry at the middle school level, we hypothesized SRSS-IE 9 fall scores would predict end of the year performance, with externalizing scores demonstrating stronger relations with the behavioral outcomes (e.g., ODRs, suspensions, and nurse visits) than academic outcomes (course failures) compared to internalizing scores. For the latent factor models at the middle school level, the externalizing construct demonstrated the strongest evidence of predictive validity (larger coefficients) for ODRs and suspensions – and smaller, but still large, coefficients for nurse visits and course failures. For the latent factor models at the middle school level, the internalizing construct was most predictive of nurse visits – which is consistent theoretically (e.g., somatic complaints likely resulting in accessing the school nurse; Saps et al., 2009). Yet, it was noteworthy that internalizing subscale scores did not predict nurse visits (p = 0.31). For the subscale score method, externalizing scores once again demonstrated the strongest predictive validity for ODRs and suspensions with lower coefficients for course failures and the smallest, yet still significant, predictive validity for nurse visits and referrals to special education.

Furthermore, SRSS-IE 9 predictive validity analyses yielded new information, with this study being the first to demonstrate externalizing and internalizing SRSS-IE scores predict referrals to special education, with internalizing scores more predictive than externalizing scores using both scoring approaches. These finding are comparable to findings of SRSS-IE 9 scores at the elementary level (Lane et al., in press), which further underscores the importance of committing to systematic screening efforts to detect student with internalizing behaviors at the first sign of concern (Bradshaw et al., 2008) – especially now, with pandemic-related experiences leaving many adolescents feeling anxious and socially isolated (Office of the Surgeon General, 2021).

For educators currently using the SRSS-IE 12, findings are relatively consistent with earlier studies with smaller samples with significant associations between both externalizing and internalizing subscales, with few exceptions. For example, it is noteworthy that the middle school internalizing subscale did not predict nurse visits as in earlier studies. This finding may have been spurious given the number of models computed, or it could have been due to the vast variability in the sample. Another exception was referrals to special education in high school. Contrary to our initial hypotheses, fall high school internalizing scores did narrowly predict referrals to special education; whereas, externalizing scores did not. In addition, we offer new evidence that the original SRSS-IE externalizing and internalizing scores predict referrals to middle school students – particularly internalizing behaviors. It should also be noted the strength of the associations with student outcomes as indicated by standardized beta weights were typically higher using the SRSS-IE 12 subscale scores for externalizing than when using SRSS-IE 9 subscale scores. However, most were still significant.

In examining SRSS-IE 9 and SRSS-IE 12 scores for high school students, results were highly comparable to those reported for middle school with the exception of predicting nurse visits (as discussed previously) and referrals to special education. Not surprisingly, high school fall externalizing scores were not predictive of referrals to special education using any scoring method, and high school fall internalizing SRSS-I4 subscale scores predicted special education referrals for high school students, which was not true of the latent factor approach (although the standardized beta coefficient was 0.205). As indicated by the standardized beta coefficients, all models yielded small associations between fall screening scores and referrals to special education. We expected that by high school, most students who might require special education services have already been referred and placed according to the rigorous process conducted by the multidisciplinary team.

Collectively, internalizing and externalizing scores from the SRSS-IE 9 and SRSS-IE 12 predict educational outcomes for high school students: ODR, suspensions, nurse visits, and course failures, and in the case of internalizing scores – referrals to special education. In addition, these same scores at the middle school predict referrals to special education. This is an important preliminary finding, and one that must be replicated before generalizing results. It is also noteworthy that for all scoring approaches, fall externalizing scores were more predictive of course failures (larger standardized beta weights than fall internalizing scores – while both were statistically significant). For secondary educators committed to meeting students’ academic needs, behavior and well-being matter. Educators can use externalizing and internalizing subscale scores along with data collected as part of regular school practices (e.g., academic screening, nurse visits, ODRs, attendance, suspensions) to inform instruction (Lane et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2022). For example, educators can (a) aggregate data to determine overall levels of externalizing and internalizing behaviors school-wide, (b) analyze classroom-level data to determine if additional low-intensity supports (e.g., instructional choice) may be beneficial, and (c) review screening data with other school-wide data to connect students to validated Tier 2 and 3 interventions.

Similar to guidance provided by Lane et al. (in press) when interpreting outcomes of similar analyses conducted at the elementary level, this sample included only middle and high schools in their first year of utilizing the SRSS-IE for universal behavior screening. At both middle and high school levels, SRSS-IE 9 scores significantly predicted multiple educational outcomes within the same school year, though it is important to replicate and extend upon these findings to ensure SRSS-IE 9 scores have similar predictive utility in later stages of systematic screening implementation. For those outcomes such as ODRs and suspensions that are direct indicators of the construct measured – externalizing behaviors, the effect sizes were large. Other outcomes were less directly linked to the construct of interest, and so it is not surprising associations were smaller.

Second, academic outcomes in the present study are represented by course failures. Because this sample includes schools from many different schools and districts, the grading scale delineating these grades as well as other school and district grading policies may vary across schools within the sample impacting how Ds and Fs are defined. Although this limitation introduces some additional ambiguity, we are hopeful advances in integrative data analysis will allow for future improvements in this area.

Third, as we have discussed, outcomes related to nurse visits were surprising. Given the number of models computed, it is possible these findings are spurious. We strongly suggest replication of these analyses related to nurse visits in middle schools given these findings were contrary to earlier inquiry.

Fourth, the sample for this study came from a data repository created by retrospectively compiling data collected over a decade spanning the 2009–2010 to 2019–2020 academic years, with the current samples over representing from the Midwest. To be clear, not all districts reported variables of interest for each student. Districts shared a range of outcome variables. Exact sample sizes are reported in tables for included variables and were large enough to conduct these analyses. For future replications, we encourage teams to engage in prospective studies to have comprehensive data sets of like variables for additional analyses, working closing with university and district leaders to rely on procedures that support open science principles (e.g., data sharing). With the commitment to early detection and using data to not only connect students to additional supports, but examine the systems as a whole (e.g., Miller et al., 2022), collaboration across research teams and district partners could be highly beneficial in examining evidence supporting score reliability and the validity of inferences based on the scores from screening tools and procedures.

Taking into account these limitations, results of this large scale, predictive validity study of the SRSS-IE 9 and continued documentation of the SRSS-IE 12 in middle and high schools suggested the externalizing and internalizing behaviors in fall predict behavioral and academic outcomes at the end of the same school year – as well as referrals to special education in middle school populations, and internalizing behaviors also predictive of referrals to special education at the high school. Rather than waiting for students to struggle and even fail academically, educators can use screening data to detect and support students at the earliest signs of concern and examine additional systems-level shifts (e.g., refinements of Tier 1 practices).

Findings build on similar inquiry conducted at the elementary levels (Lane et al., in press), establishing evidence for predictive validity of the inferences drawn from the newly defined Student Risk Screening Scale – Internalizing and Externalizing (SRSS-IE 9) when used for the first time by middle and high school teachers from 43 schools, representing multiple geographic regions in the United States between the 2009–2010 and 2019–2020 academic year. Moreover, fall externalizing and internalizing latent factors as well as subscale scores (SRSS-E5, SRSS-I4) from the SRSS-IE 9 predicted year-end behavioral (ODRs, in-school suspensions) and academic (course failures) outcomes as well as referrals to special education for middle school levels students, with SRSS-IE 12 subscale scores (SRSS-E7, SRSS-I5) yielding similar outcomes. Results were highly consistent at the high school level, with the exception of fall externalizing scores not predicting referrals to special education and nurse visits being predicted consistently across models at the high school level and not so at the middle school level. Pending replication, we are cautiously optimistic about this preliminary evidence SRSS-IE 9 subscale scores predict important student outcomes in secondary schools. Next, it will be important to replicate all findings – K-12 and conduct subsequent studies to ascertain new cutting scores for the SRSS-IE 9 for elementary, middle, and high school contexts. These future scores are important for practitioners (and researchers) who currently use these risk categories (low-, moderate-, and high-risk for internalizing and externalizing behaviors) to (a) examine overall levels of externalizing and internalizing behavior patterns for the school (or district), (b) determine when teachers may benefit from incorporating low intensity supports (e.g., precorrection, instructional choice) into instruction, and (c) detect students who might need more than Tier 1 efforts.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: these data cannot be shared, as not all districts allowed for data sharing – including de-identified data. Contact S2F0aGxlZW4uTGFuZUBrdS5lZHU= for information regarding this study.

Authors and project staff followed all current ethical standards with Project SCREEN. Authors and project staff followed procedures for constructing a Project SCREEN data repository in accordance with a University of Kansas Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocol. After receiving IRB approval to construct the deidentified data repository for secondary data analysis, data files were reviewed for additional accuracy and quality checks beyond those that were conducted as part of the previously approved IRB studies. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

KLL conceptualized the study in partnership with WO and MB. NL, KSL, KF, RSR, and C-NC collaborated on data merging, cleaning, analysis, and reporting, in partnership with the KLL, WO, and MB. RS and EC collaborated with KLL, WO, MB, NL, and KSL on data collection, data management, data entry, and preliminary analyses. All parties contributed to the writing for the manuscript as well as other dissemination activities.

This research was supported in part by the Institute of Education Sciences Project SCREEN (R324A190013). Opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Education, and such endorsements should not be inferred.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer BB declared a past collaboration with the author KL at the time of review.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1251063/full#supplementary-material

Agnafors, S., Barmark, M., and Sydsjö, G. (2021). Mental health and academic performance: a study on selection and causation effects from childhood to early adulthood. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 56, 857–866. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01934-5

Bera, L., Souchon, M., Ladsous, A., Colin, V., and Lopez-Castroman, J. (2022). Emotional and behavioral impact of the COVID-19 epidemic in adolescents. Current Psychiatry Report 24, 37–46. doi: 10.1007/s11920-022-01313-8

Berry, C. M. (2015). Differential validity and differential prediction of cognitive ability tests: understanding test bias in the employment context. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psych. Organ. Behav. 2, 435–463. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111256

Bradshaw, C. P., Buckley, J., and Ialongo, N. (2008). School-based service utilization among urban children with early-onset educational and mental health problems: the squeaky wheel phenomenon. Sch. Psychol. Q. 23, 169–186. doi: 10.1037/1045-3830.23.2.169

Buckman, M. M., Lane, K. L., Common, E. A., Royer, D. J., Oakes, W. P., Allen, G. E., et al. (2021). Treatment integrity of primary (tier 1) prevention efforts in tiered systems: mapping the literature. Educ. Treat. Child. 44, 145–168. doi: 10.1007/s43494-021-00044-4

Chen, H., Cohen, P., and Chen, S. (2010). How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Commun. Statistics Simul Comput 39, 860–864. doi: 10.1080/03610911003650383

Colman, I., Wadsworth, M. E., Croudace, T. J., and Jones, P. B. (2007). Forty-year psychiatric outcomes following assessment for internalizing disorder in adolescence. Am. J. Psychiatr. 164, 126–133. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.126

Cook, B. G., Fleming, J. I., Hart, S. A., Lane, K. L., Therrien, W. J., van Dijk, W., et al. (2022). A how-to guide for open-science practices in special education research. Remedial Spec. Educ. 43, 270–280. doi: 10.1177/074193252110191

Deng, J., Zhou, F., Hou, W., Heybati, K., Lohit, S., Abbas, U., et al. (2023). Prevalence of mental health symptoms in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1520, 53–73. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14947

Drummond, T. (1994). The student risk screening scale (SRSS) Josephine County Mental Health Program.

Fey, C. F., Hu, T., and Delios, A. (2022). The measurement and communication of effect sizes in management research. Manag. Organ. Rev. 19, 176–197. doi: 10.1017/mor.2022.2

Forness, S. R., Freeman, S. F. N., Paparella, T., Kauffman, J. M., and Walker, H. M. (2012). Special education implications of point and cumulative prevalence for children with emotional or behavioral disorders. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 20, 4–18. doi: 10.1177/1063426611401624

Gandhi, A. G., Clemens, N., Coyne, M., Goodman, S., Lane, K. L., Lembke, E., et al. (2023). “Integrated multi-tiered systems of support (I-MTSS): new directions for supporting students with or at risk for learning disabilities” in Handbook of learning disabilities. 3rd ed (Guildford Press)

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 38, 581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Gregory, C., Graybill, E. C., Barger, B., Roach, A., and Lane, K. L. (2021). Predictive validity of student risk screening scale-internalizing and externalizing (SRSS-IE) scores. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 29, 105–112. doi: 10.1177/1063426620967283

Hinshaw, S. P. (1992). Externalizing behavior problems and academic underachievement in childhood and adolescence: causal relationships and underlying mechanisms. Psychol. Bull. 111, 127–155. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.127

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, 20 U.S.C. 1400 et seq. (2004). Reauthorization of individuals with disabilities education act 1990

Jones, C., Graybill, E., Barger, B., and Roach, A. T. (2020). Examining the predictive validity of behavior screeners across measures and respondents. Psychol. Sch. 57, 923–936. doi: 10.1002/pits.22371

Kamphaus, R. W., and Reynolds, C. R. (2007). BASC–2 behavioral and emotional screening system (BASC-2 BESS) Pearson Assessments.

Kessler, R. C., and Merikangas, K. R. (2004). The national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13, 60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166

Lane, K. L., Cook, B. G., and Tankersley, M. (Eds.) (2013a). Research-based strategies for improving outcomes in behavior Pearson.

Lane, K. L., Kalberg, J. R., Parks, R. J., and Carter, E. W. (2008). Student risks screening scale: initial evidence for score reliability and validity at the high school level. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 16, 178–190. doi: 10.1177/1063426608314218

Lane, K. L., and Menzies, H. M. (2009). Student risk screening scale for internalizing and externalizing behavior (SRSS-IE). Available at: http://www.ci3t.org/screening

Lane, K. L., Menzies, H. M., Oakes, W. P., Lambert, W., Cox, M. L., and Hankins, K. (2012). A validation of the student risk screening scale for internalizing and externalizing behaviors: patterns in rural and urban elementary schools. Behav. Disord. 37, 244–270. doi: 10.1177/019874291203700405

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Buckman, M. M., Lane, N. A., Lane, K. S., Fleming, K., et al. (in press). Additional evidence of predictive validity of SRSS-IE scores with elementary students. students. Behavioral Disorders.

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Buckman, M. M., Lane, N. A., Lane, K. S., Fleming, K., et al. (2023). Examination of the factor structure and measurement invariance of the SRSS-IE. Remedial Spec. Educ. doi: 10.1177/07419325231193147

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Cantwell, E. D., Common, E. A., Royer, D. J., Leko, M., et al. (2019a). Predictive validity of student risk screening scale for internalizing and externalizing (SRSS-IE) scores in elementary schools. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 27, 221–234. doi: 10.1177/1063426618795443

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Cantwell, E. D., Menzies, H. M., Schatschneider, C., Lambert, W., et al. (2017). Psychometric evidence of SRSS-IE scores in middle and high schools. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 25, 233–245. doi: 10.1177/1063426616670862

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Cantwell, E. D., and Royer, D. J. (2019b). Building and installing comprehensive, integrated, three-tiered (Ci3T) models of prevention: A practical guide to supporting school success (v1.3) KOI Education.

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Cantwell, E. D., Royer, D. J., Leko, M., Schatschneider, C., et al. (2019c). Predictive validity of student risk screening scale for internalizing and externalizing scores in secondary schools. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 27, 86–100. doi: 10.1177/1063426617744746

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Cantwell, E. D., Schatschneider, C., Menzies, H., Crittenden, M., et al. (2016). Student risk screening scale for internalizing and externalizing behaviors: preliminary cut scores to support data-informed decision in middle and high schools. Behav. Disord. 42, 271–284. doi: 10.17988/BD-16-115

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Carter, E. W., Lambert, W., and Jenkins, A. (2013b). Initial evidence for the reliability and validity of the student risk screening scale for internalizing and externalizing behaviors at the middle school level. Assess. Eff. Interv. 39, 24–38. doi: 10.1177/1534508413489336

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Common, E. A., Brunsting, N., Zorigian, K., Hicks, T., et al. (2019d). A comparison between SRSS-IE and BASC-2 BESS scores at the middle school level. Behav. Disord. 44, 162–174. doi: 10.1177/0198742918794843

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., and Menzies, H. M. (2014). Comprehensive, integrated, three-tiered (CI3T) models of prevention: why does my school – and district – need an integrated approach to meet students’ academic, behavioral, and social needs? Prev. Sch. Fail. 58, 121–128. doi: 10.1080/1045988X.2014.893977

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., and Menzies, H. M. (2021). Considerations for systematic screening PK-12: universal screening for internalizing and externalizing behaviors in the COVID-19 era. Prevent School Failure 65, 275–281. doi: 10.1080/1045988X.2021.1908216

Lane, K. L., Parks, R. J., Kalberg, J. R., and Carter, E. W. (2007). Systematic screening at the middle school level: score reliability and validity of the students risk screening scale. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 15, 209–222. doi: 10.1177/10634266070150040301

Lebrun-Harris, L. A., Ghandour, R. M., Kogan, M. D., and Warren, M. D. (2022). Five-year trends in US children’s health and well-being, 2016-2020. JAMA Pediatr. 176, –e220056. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0056

Ma, Z., Sherod, R., Lane, K. L., Buckman, M. M., and Oakes, W. P. (2022). Interpreting universal behavior screening data: Questions to consider. Center on PBIS, University of Oregon. Available at: https://www.pbis.org/resource/interpreting-universal-behavior-screening-data-questions-to-consider

Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., et al. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 49, 980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017

Miller, F. G., Murphy, E., and Sullivan, A. L. (2022). Equity-oriented social, emotional, and behavioral screening: Equity by design Midwest & Plains Equity Assistance Center.

Moulton, S. E., Young, E. L., and Sudweeks, R. R. (2019). Examining the psychometric properties of the SRSS-IE with the nominal response model within a middle school sample. Assess. Eff. Interv. 44, 227–240. doi: 10.1177/1534508418777866

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. (1998-2017). Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables, user’s guide. Muthén & Muthén.

National Center on Intensive Intervention. (2017/2022). Behavior screening rubric. Available at: https://intensiveintervention.org/sites/default/files/NCII_BScreening_RatingRubric_July2017.pdf

Nelson, J. R., Benner, G. J., Lane, K., and Smith, B. W. (2004). Academic achievement of K-12 students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Except. Child. 71, 59–73. doi: 10.1177/001440290407100104

Office of the Surgeon General. (2021). Protecting youth mental health: The U.S. surgeon General’s advisory. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf

Saps, M., Seshadri, R., Sztainberg, M., Schaffer, G., Marshall, B. M., and Di Lorenzo, C. (2009). A prospective school-based study of abdominal pain and other common somatic complaints in children. J. Pediatr. 154, 322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.09.047

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2022). Pandemic learning: As students struggled to learn, teachers reported few strategies as particularly helpful to mitigate learning loss. [report, GAO-22-104487]. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-104487

Walker, H. M., and Severson, H. H. (1992). Systematic screening for behavior disorders (SSBD) technical manual: Universal screening for preK–9 Pacific Northwest Publishing.

Weist, M. D., Flaherty, L., Lever, N., Stephan, S., Van Eck, K., and Bode, A. (2017). “The history of future of school mental health” in School mental health service for adolescents. eds. J. R. Harrison, B. K. Schultz, and S. W. Evans, 3–23. doi: 10.1093/med-psych/9780199352517.001.0001

Keywords: universal behavior screening, predictive validity, tiered systems, internalizing behavior, externalizing behavior

Citation: Lane KL, Oakes WP, Buckman MM, Lane NA, Lane KS, Fleming K, Swinburne Romine RE, Sherod RL, Cantwell ED and Chang C-N (2024) New evidence of predictive validity of SRSS-IE scores with middle and high school students. Front. Educ. 8:1251063. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1251063

Received: 30 June 2023; Accepted: 21 December 2023;

Published: 23 January 2024.

Edited by:

Robin Parks Ennis, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United StatesReviewed by:

Sara Moulton, Brigham Young University, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Lane, Oakes, Buckman, Lane, Lane, Fleming, Swinburne Romine, Sherod, Cantwell and Chang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kathleen Lynne Lane, S2F0aGxlZW4uTGFuZUBrdS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.