- 1Department of Primary and Secondary Education, Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway

- 2Department of Social Work, Child Welfare and Social Policy, Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway

Interprofessional collaboration (IPC) is increasingly being recognised as an important mechanism to improve the quality of services offered to children. This study imparts results from an investigation of undergraduate students’ participation in an interprofessional education (IPE) programme focusing on working with children (0–18). The programme participants include students across the disciplines of education, health, and social care. In the study the students’ accounts of group processes by which they negotiated their positions and the relevance of their emerging professional knowledge in interprofessional student groups are explored. The more overarching aim is to contribute to a knowledge base serving the development of broad IPE initiatives. Qualitative interviews were conducted with students (n = 15) to explore their experiences participating in the programme. Positioning theory was used as an analytical framework. The results indicate that the students’ joint constructions of the aim of the learning activity were vital for their joint meaning-making in the interprofessional learning (IPL) groups and for processes of positioning. In addition, students’ participation in the IPL groups was closely linked to their approach to negotiations of relevance. The pedagogical implications of these results are discussed.

1 Introduction

There is a global recognition of interprofessional collaboration (IPC) as an important mechanism to improve the quality of care and services within the health and social care sectors (Frenk et al., 2010; WHO, 2010; Xyrichis, 2020; Thistlethwaite and Xyrichis, 2022). However, a sole focus on IPC between professionals within the health and social care sectors is too limited in scope to address the complex needs of children aged 0–18 (see, e.g., Hansen et al., 2018). In modern welfare states, a broad array of professional efforts is crucial to support the needs of children in general healthcare settings and in kindergartens, schools, and after-school care settings. Some children also interact with welfare professionals in more specialised contexts, such as children’s welfare services or specialised healthcare services. Offering children and their families comprehensive support for education, health, and social welfare requires collaboration and mutual understanding among professionals within and beyond the health and social care sectors (Ulvik and Gulbrandsen, 2015), an approach referred to as “broad IPC” within this analysis.

In recent years, key Norwegian government policy documents [e.g., Report No. 13 (2011–2012), 2011; Report No. 20 (2012–2013), 2012; Prop. 100 L (2020–2021), 2021] and other governmental initiatives such as the 0–24 collaboration1 have highlighted the need to increase collaboration among professionals involved in children’s lives. However, new reports reveal that this intention is not always reflected in professional practices (NBHS, 2018, 2019). To address this discrepancy, the Norwegian University OsloMet has developed the broad interprofessional education (IPE) programme Interprofessional Interaction with Children and Youth (INTERACT). The purpose of the programme is to develop more coordinated services and better collaborations between professionals involved in children’s lives. The programme is offered to professional students within and across the disciplines of education, health, and social care at OsloMet, and the programme’s focus is on IPC with and about children.

The research questions were: (1) How do students establish a common agenda for their work in interprofessional learning groups? (2) How do students present their emergent professional knowledge in the groups, and (3) negotiate the relevance of their professional knowledge for their joint tasks throughout the group processes?

1.1 Interprofessional education

Increased global attention to the importance of IPC has led to the development of an extensive number of IPE related programmes (Molloy et al., 2014) and increased awareness regarding the provision of high-quality IPE. In 2016, the UK Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE) published guidelines on IPE as part of a global effort to increase the quality of IPE. The CAIPE defines IPE as “occasions when members or students of two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care and services” (CAIPE, 2016). The published guidelines build on the experiences of CAIPE members, national and international IPE movements, UK research findings, and the results of systematic and scoping research reviews. The guidelines emphasise that learners in IPE participate in socially constructed learning processes whereby the responsibility for learning rests on the whole group (Barr et al., 2016). This focus accentuates the relational character of learning in IPE contexts. However, systematic reviews have found that customising IPE can be difficult due to the varying characteristics, abilities, and viewpoints of the participating students (Reeves et al., 2016). It may be particularly challenging to involve students from a broad array of professional programmes that adhere to a variety of underlying disciplinary thinking approaches.

In a study aiming to “conceptualize the social processes that constitute activities in IPE and collaborative practice,” Green (2013 p.35) found that the participating students constructed the interprofessional aspects as either a dimension of the professional or an addition to it. The first option represents an integration of the professional and the interprofessional, whereas the second presents “being interprofessional” as an option rather than a requirement of being professional (p. 36). The willingness of the students in Green’s study to devote resources to interprofessional outcomes was linked to their decisions regarding the perceived relevance of the interprofessional for their own professional development. If IPE was perceived as relevant and constructed as a dimension of the professional, resources were devoted accordingly (Green, 2013).

Developing broad IPE may necessitate increased attention to students’ participatory efforts and opportunities, as well as their ideas about their own and others’ conceivable contributions to a joint task. IPE researchers recognise a need to explore the processes involved in IPE and to understand the “why” and “how” of this educational model (Lawn, 2016). The “why” may be enlightened through theory, whereas the “how” may be treated as an empirical question. The question of “how” points to processes in the groups, processes that are fueled by the participants’ introductions of content and ideas both from their respective programme syllabus, and from the materials presented in the IPE programme. It is the students’ accounts of their participation in broad interprofessional learning groups that is analysed in this study.

1.1.1 The IPE programme Interprofessional Interaction with Children and Youth

The INTERACT programme involves undergraduate students across the disciplines of education, health, and social care. Participating students are expected to gain knowledge and experience in cooperation with participants from other professional paths who are or will be involved in children’s lives. The students are encouraged to approach children’s everyday lives as a joint frame for interprofessional work. They learn about communication and cooperation with children and their families, as well as children’s rights as participants in professional practises (United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1990). The programme is based on an ecological theory approach to IPC concerning children and was developed from a child-centred perspective that places the child’s focus in the centre, rather than the services. The aim of the programme is to establish a joint knowledge focus for all student participants. The theoretical approach draws on the “common knowledge” concept defined by Edwards (2012), which refers to processes occurring in IPC across practises. Ideally, the joint focus configures the attention of the collaborating professionals in ways that support collaboration while maintaining each professional’s respective expertise and using it for the benefit of the child.

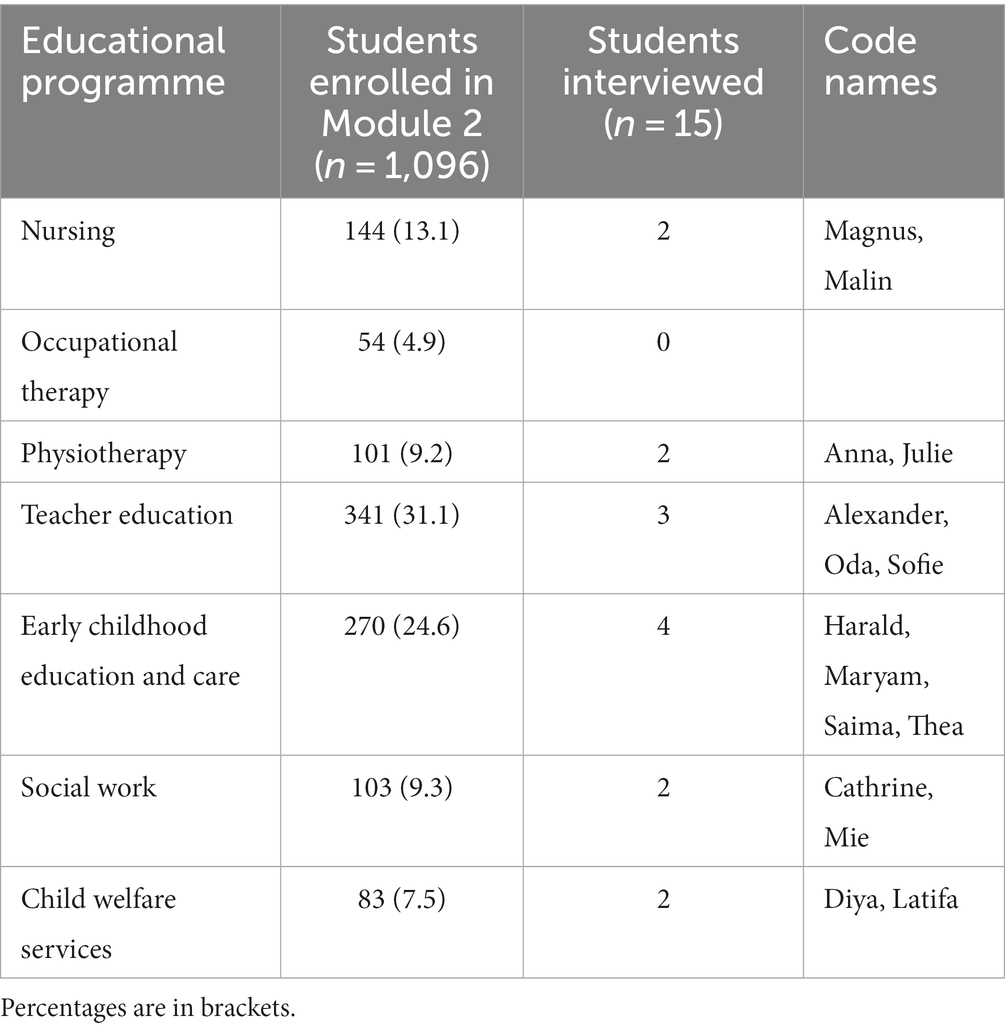

The INTERACT programme is organised as an IPE programme in which participating students attend one module per year (Modules 1, 2, and 3) during their bachelor’s degree studies. Each INTERACT module has separate but interacting learning goals that contribute to meeting the overarching aims of the programme. The theoretical introduction is based on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). This model presents the child in continuous social interactions with different social partners – such as friends, siblings, parents, teachers, nurses, and coaches – and situates these interactions within the context of broader social systems in their neighbourhoods and societies. A digital learning platform is made available to the students, and they are expected to read and watch preparatory materials before attending group sessions. Expected workload for each of the modules is about 40 h per module. This includes the preparatory work, attendance during seminar days and assignments. Participating students work together in interprofessional learning groups of 6–10 students for 1 or 2 days each year. The groups are put together by the administrative support team involved in the organisation of the programme, based on lists of the students attending each of the participating professional programmes. The organisers aim for broadly composed groups comprising students across all disciplines. However, as there is an uneven number of students participating from each of the professional programmes, not all groups include students from all programmes. Table 1 (see 2.2) displays the distribution of students participating from each of the professional programmes, at the time of data collection for this study.

Table 1. The distribution of students enrolled in Module 22,019/2020 and the sub-sample of interview participants.

During the seminar days students are provided with detailed descriptions of how to proceed with the work in the groups. This includes the assignment of distinct roles such as to act as chair and secretary, time estimates for how long time the students should expect to spend on each task, and information about the assignments. Each group is also allocated a supervisor who meet physically with the students to support them in their work. Supervisors are not expected to be with each student group all day, but should meet with the students and be available for questions. Supervisors are recruited among academic staff, master’s degree students from relevant subject areas at the university, and professionals in the practice field. Through casework, typically presented as a child in an everyday context, the students are encouraged to explore various aspects of the child’s situation and discuss their professional understandings and optional approaches to supporting the child in its context. The aim of the programme is for the students to become aware of their own and each other’s possible contributions to the group, and their explicit and implicit professional ideas about the presented child and the child’s situation. This interprofessional group work, carried out over three consecutive years, lays the groundwork for an expanded and shared understanding of future collaboration among the students and with the child.

1.2 Theoretical perspectives

This study draws on a sociocultural understanding of learning, in which learning entails both personal and social transformation and is developed and negotiated through social processes (Packer and Goicoechea, 2000). Knowledge emerges from interactions between the individuals who contribute to the process of learning (Clark, 2006). The sociocultural theory of learning aligns with Bruner’s (1990) concept of making meaning as a process of connecting one’s own experiences to those of others, and to broader cultural ideas. Meaning-making processes involve continuous “negotiations” between those who are directly involved in learning interactions and/or the cultural ideas that frame the interactions. In this analysis, the corpus of course syllabi in higher education are considered local cultural ideas that underly the discussions in the interprofessional learning groups.

Positioning theory (Potter and Wetherell, 1987; Davies and Harré, 1990; Tan and Moghaddam, 1999; Harré and Langenhove, 1999a,b) is used as a framework to analyse the students’ processes of meaning-making within the IPE groups, as recounted by the interviewees. The concept of “positioning” focuses analysis on the dynamic aspects of social encounters (Davies and Harré, 1990, p. 43). Within positioning theory, the word “discourse” is considered to “cover all forms of spoken interaction, formal and informal, and written texts of all kinds” (Potter and Wetherell, 1987, p. 7). Similarly, the term “discursive practices” includes all the ways in which people actively produce social and psychological realities (Davies and Harré, 1990, p. 45). In accordance with Davies and Harré (1990), the concept of positioning is defined for the purposes of this analysis as follows:

With positioning, the focus is on the way in which the discursive practices constitute the speakers and hearers in certain ways and yet at the same time is a resource through which the speakers and hearers can negotiate new positions (p. 62).

In positioning theory (Harré and Langenhove, 1999a,b), positions are relational and defined and redefined through ongoing discourse, and they are “associated with particular rights, duties and obligations for speakers and hearers”(Tan and Moghaddam, 1999, p. 184), where the “right to speak” and “right to hear” are central. However, positions are not fixed. They are constructed and reconstructed through ongoing discursive practices. Participants can initiate or be offered the opportunity to contest or alter their positions. Positions can be altered both by gaining acceptance for the content of an argument and/or through the argumentative process itself and can thus be part of power processes in the groups. A central question then becomes: in which ways and by what kinds of arguments can the rights to speak/hear be established? Identifying positioning processes in the interviewees’ accounts of the group work was central to the analysis.

2 Methods

The present study is part of a larger project that explores INTERACT as a broad IPE initiative to support students’ understandings of IPC with and about children. The overarching project comprises both survey (see Braathen, 2022) and interview data. The present analysis is based on data from individual qualitative interviews with students attending INTERACT.

In this study, INTERACT is the empirical case and analytic foundation. The programme provides the actual frames and inputs that the interviewed students are faced with. As such the programme will play an explicit part in the text. Due to the students’ wide variety of professional and theoretical backgrounds, the negotiations of what should be considered valid contributions in a joint task, are played out in a complex context. To plan and evaluate broad IPE programmes may require sensitivity towards processes of negotiations among the participants, as well as between the students and their respective programme curricula. Starting on the level of the students’ accounts of the group works, the analyses were further developed by introducing concepts rooted in sociocultural and positioning theory. This step points to the more overarching aim of the study which is to contribute to a knowledge base serving the development of broad IPE initiatives. The theoretical optic contributes to the transferability (Lincoln and Guba, 1985) of the results.

INTERACT was first piloted in the 2017–18 academic year, and the programme was still in a developmental phase at the time of data collection for this project in 2019–20. At the time, only Modules 1 and 2 were fully developed and implemented, and seven professional study programmes were included in INTERACT: teacher education, early childhood education and care, social work education, child welfare studies, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and nursing.

2.1 Ethical issues

The project was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data.3 All participants were informed about the purpose and design of the study, what their participation would involve, and their rights to withdraw from the study at any point. Written informed consent was obtained from the student participants. To secure participants’ anonymity, pseudonyms are used in the transcripts and all other presentations of the research findings. No information is shared that may reveal participants’ identities. In the interviews participating students were asked to describe their IPL group (composition etc.) instead of providing the group number of the IPL group they had been part of directly. This was a measure taken to ensure the anonymity also of the other students participating in INTERACT, but not participating in the study. In transforming direct citations from oral to written language and translating from Norwegian to English, care has been taken to preserve the interviewees’ original meaning.

There is no teacher–student relationship between the researchers involved in this study and the students attending INTERACT. The first author was at the outset a novice in the field of interprofessional education. The second author had been involved in developing INTERACT in the programme’s early phase but was not involved when the study reported here was planned and carried through. Previous informal feedbacks from the involved students were highly differing and the need for a systematic investigation was obvious. Due to the wide variation in the students’ immediate feedback, both authors’ primary concern was to establish analytic approaches that could capture this range of variation.

2.2 Sample and sampling strategies

The individual interviews were conducted in May and June 2020. Before the interview round started it was decided that at least four students from each of the three disciplines would be interviewed. This was to ensure that perspectives of students across all disciplines could come to the fore. The study participants were recruited through announcements in lectures, referrals from lecturers and other students, and online announcements. In the end 15 students were interviewed: seven were recruited from education studies, four from healthcare studies, and four from social care studies. Three of the students were male and 12 were female. Most students had attended Modules 1 and 2, though some had only experienced one of the modules. All students participated in the programme before the COVID-19 pandemic occurred, and interacted with their peers physically. Table 1 provides an overview of this study’s population and of the sample of students participating. An overview of the interviewed students and how their IPL groups were composed, as recounted by the participants themselves in the interviews, can be found as an Supplementary Material.

2.3 Qualitative interviews and analysis

The interviews were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, some face-to-face and others online using Zoom due to periods of strict lock-down rules in Norway. The interviews were conducted by the first author and lasted from 43–75 min. They were all audio recorded and transcribed.

The overarching aim of the interviews was to explore the students’ experiences participating in the interprofessional learning groups. The students were initially asked to share their experiences from their recent IPL group (Module 2 for most interviewees), focusing on themes such as the learning context, group interactions, and their perceptions of learning outcomes from participation in the group. The interview framework contained both open questions and prompts to encourage further elaboration of the interviewees account [For example: Can you start by telling what you did in your group? What did you talk about? What happened next?]. After each interviewee shared their initial accounts of the group works, the interviewer followed up with in-depth questions about the course of discussion in their group, their understanding of their own and others’ contributions, and connections between the group tasks and the students’ primary educational paths. The empirical material therefore contains both relatively short answers to specific questions as well as more comprising accounts about an episode or a work sequence during the group sessions.

Both authors read the transcribed interviews, and a qualitative analysis was performed with a focus on constructing meaning within each interview and identifying patterns across the material (Brinkmann and Kvale, 2015; Cohen et al., 2018). The analysis included empirically driven interpretation and concepts drawn from the theoretical framework. First, the authors familiarised themselves with the materials and generated themes to be further explored. An example of such a theme is an “us/them” dichotomy regarding “closeness to children” that appeared in the materials. The initial analysis showed that the interviewees often refereed to themselves, and others, with relation to their professional closeness to “children”. Next, the authors used central concepts from positioning theory as a tool to ask analytical questions to the material, focusing on the students’ accounts of how the negotiations between the students played out, and why. To increase internal validity, the two authors discussed preliminary results throughout the analysis with an external team member who provided feedback (Brinkmann and Kvale, 2015).

From a sociocultural perspective, students involved in IPE create knowledge through social processes in culturally constituted communities with others. The students in our study were enrolled in various professional programmes that differ in focus. The analysis sought to examine the students’ accounts of how the negotiations between them were constructed, and why they were constructed in those ways. These negotiations are thematically connected to the specific IPE programme that these students were enrolled in. It is their participation in INTERACT that frames their experiences and accounts. Other collaboration platforms may contain different conditions for joint work. However, throughout the analytical work we came to see the negotiation process itself as crucial for the development of joint work in the groups.

The authors’ interest in the processes of positioning in the IPL groups led to specific examination of three aspects of the students’ meaning-making processes which will be presented in the study’s third section:

1. Students’ explorations into INTERACT.

2. Negotiations of relevance: the right to hear and the right to speak.

3. Ways of altering positions: “I can contribute with something else”.

3 Results

3.1 Students’ explorations into INTERACT

A recurring theme in the interviews was that the students started the IPE activity with discussions of what INTERACT “is about” and how they should proceed with the activity. The analytic work however suggests that these “what” and “how” aspects of the discussions were deeply intertwined as the definition of “what” seems to constitute conditions for “how” to proceed, and who was expected to have relevant contributions. The interviewed students explained that they commonly began the group work by discussing why they were there, what INTERACT was thematically about, and what strategies they should employ in their groupwork. These discussions occurred both in Modules 1 and 2 but the participants told that it took more time in the first module. Most students started Module 1 in the second term of their bachelor’s programme.4 The participants explained that they at that time still felt “fresh” as students. They were still novices within their fields, and most were new to IPE.

In the interviews, the participants commonly said that they viewed INTERACT to be “about children”. However, what was considered relevant to know “about” children was not always explicated. The interviews indicate that by engaging with each other and the materials provided, the students also had ongoing interpretations of what child-related IPE may concern. The design of INTERACT, that is the material presented to the students, and the design of the casework were important in these discussions. Many interviewees explained that they looked for clues in the materials to understand how they and the other participants could relate to the topic. They also exemplified how this became part of group conversations. This theme comes across in the interview excerpt below with Anna, a physiotherapy student, who recounted a discussion in her group about INTERACT’s context and the involvement of physiotherapy students. Anna explained:

The nurse and I struggled a bit to… find our place in this. The others said it outright; they did not quite understand why physiotherapy students were in the project. They kind of did not understand how we fitted in.

We see here that Anna’s process of constructing the meaning of INTERACT was guided not only by her own interpretations but also by statements from other participants. When the interviewer followed up by asking whether Anna agreed with the other students’ statements, she responded:

Yes, a little, because the case was a bit vague. It was not specifically related to physiotherapy. It is physical activity and such, but in our education, when we learn about children and adolescents, we mostly focus on small children and babies, in terms of motoric control, and a lot on cerebral palsy. There’s not so much focus on other things perhaps, like, for example, ADHD and those types of diagnoses. Then we struggle a little to see; where do I fit into it? When you do not have that background, in a way.

Anna’s statement illustrates how student participants searched for meaning by engaging with the materials they were provided, as well as how the activity of “interpreting what INTERACT is about” was approached both individually and through interactions with other students. By exploring the materials and discussing it within the group, the students defined the purpose of the programme and began positioning themselves and each other accordingly.

Anna’s statement also illustrates how she and others approached the task by bringing in the question of diagnoses: were the group members familiar with the idea of medical diagnoses and did they know implications of the same diagnoses? Anna explained that despite seeing that the case included physical activity, she struggled to find her place in the group work when she could not link the case to a known diagnosis or other known topics in her field. When other students in the group questioned her participation, Anna did not receive support for her position as a resource in the group.

Early childhood education student Thea interpreted the interactions in her group as follows:

I felt that, for the others, that this has really nothing to do with you. How the physical education class in a school is for a child (…). It became like: okay, he gets teased in class, how would you proceed as a teacher or as an adult? Then I think that the nurse has nothing to do with this, really. Or ergonomics and things like that.

Thea’s statement further illustrates how the students’ emerging processes of making meaning occurred through interactions with each other and the materials. This statement also illustrates how the students’ ongoing interpretations of what INTERACT “is about” impacted their positioning in the group and thus their rights and duties in the group work.

Most of the interviewed students presented the theme of their group work to be “about children”, commonly a rather vague notion. However, we will show that it had consequences for the group processes, the how of the group work.

3.2 Negotiations of relevance: the right to hear and the right to speak

3.2.1 What do I – and you – know about children?

From the interviews it appears that most groups initially established that INTERACT is “about children,” and from that starting point the students started to decipher what this meant for each of them, and how they could relate to the topic. Part of this work was to evaluate what prior knowledge each participant could bring to the group work. Individually and through group discussions, the students made judgments about how each participant could contribute relevant knowledge to the group. Processes of positioning took place through joint exploration of the knowledge that each person brought to the conversation.

Early childhood education student Saima explained that it was important for her to establish a link between INTERACT and her study programme:

The first time it was linked to a theme we knew from early childhood education and care, so I felt I could relate to the assignments we were given. Despite being shy, I could contribute with things that we had learned in class.

Saima’s statement is typical of how each student searched for ways to relate to the topic and entered the conversation based on their prior knowledge. Students explained that identifying links between their own syllabus and INTERACT was important for their active participation. However, doing so could also have the opposite effect, as nursing student Malin explained:

The first time, at least, I thought that we should bring in what we knew (…). Then I sat there and felt in a way that I know nothing about this, because we had previously had very little about children.

Here we see how Malin constructed prior knowledge “about children” as the knowledge she should contribute to the conversation, but she did not see how. Moreover, she did not perceive alternative knowledge from her professional programme as relevant. In the interviews, several students made similar remarks explaining how they could contribute to the group work by identifying links between their own professional programmes and children, or the opposite feeling “that they [or I], had nothing to contribute”. These constructions affected how the students negotiated the relevance of their emerging professional knowledge and used that information to influence the groups’ discursive practices.

3.2.2 Explorations of relevance: the right to speak and the right to hear

Teacher education student Sofie stated:

Two of us were from the teacher education programme, one or two were from early childhood education and care, and one was from nursing. The rest had nothing to contribute with, in a way, because they had not yet been exposed to children in their studies – neither in Module 1 nor Module 2. In a way, it was just us who did the talking then.

Sofie’s statement demonstrates how prior knowledge “about children” became the central condition for contributions to her group. Those who did not have such prior knowledge were assumed to have nothing to contribute. Under the surface of Sofie’s statement, we thus see a glimpse of an interpretation of “contributions about children” that may limit the joint focus of the IPL activity. The “about children” discourse put restrictions on “who may hear” and “who may speak” in the group. Later in the interview, Sofie presented her thoughts as to why some students were active in the group and others were not:

We had heard about most, or the new, concepts of Bronfenbrenner’s model and all of them… so, we already knew something about it. I think it was a little intimidating for those who had not been exposed to it before, that we already had a repository of knowledge, albeit very small. They became a bit like, “Oh okay, I might as well withdraw, and you can take over”.

Again, Sofie attributed the varying degrees of participation to the students’ differing levels of prior knowledge “about children”. In this case, she felt that the students took on different positions in the group work based on their experience with a relevant theory presented in the study material. Sofie’s statement exemplifies the relationality of her positioning. In the previous excerpt, she claimed “the right to speak” based on her prior knowledge “about children”. Here, she points to other students in her group claiming a “right to hear” based on the same logic. Employing a narrow interpretation of “interprofessional collaboration with children” and basing the right to participate on prior knowledge has the potential to marginalise some students. Not all students exercised the same right to speak in the IPL groups. For example, this group dynamic affected the participation of physiotherapy student Julie as follows:

At least in the first year, we had not learnt anything about children and young people at all, so we did not have much to come up with. We may not have felt that it was very relevant then, but in retrospect, we see that it was. When we attended Module 2 and had learnt a little about children and young people, it was much better. Also at that time, “communication” and “co-participation” were themes, and this is something we had learnt a lot about in physiotherapy classes. Still, it was very nice when we had some knowledge about children and young people in advance of when we should have about it ourselves. We knew nothing about it, really. The other professions knew a lot about it, so we became a bit… passive, maybe. Also, several of the students in our group from the other professional programmes asked: “What are you really doing here?”

In this statement, Julie establishes links between parts of her syllabus and INTERACT while acknowledging that her position in the group was influenced by having less knowledge “about children”. The statement demonstrates that her marginalised position in the group was accentuated by comments from other students in the group.

These interview excerpts illuminate a central element in the students’ meaning-making processes in INTERACT, which is that they position themselves relative to each other based on who is perceived to contribute the most relevant knowledge. In turn, these perceptions impact the students’ participation in the IPL group, as well as how the students value each other’s contributions. In the following interview excerpt, teacher education student Oda makes a distinction between students who attended programmes that were closely related to “children” and those who did not. She suggested that the former group would gain the most from participating in INTERACT. When asked how she felt about learning with and from students from physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and social work, she replied:

I think it is relevant, but I feel that it is a bit beside teacher education, and what I will use later. It’s nice to know, but it’s not essential in a way. I do not necessarily think I will remember all of what the physiotherapist said and use it later.

Oda was then asked whether each student presented their own perspective in discussing the casework:

Yes, we did. And I feel like, for instance, the student from occupational therapy had a lot to contribute related to how occupational therapists work to help people be able to live as normal as possible, given their capabilities. I understood a lot more… I actually did not even know what occupational theory was, so that was a bit interesting.

Oda concluded that she may potentially use the knowledge she gained about occupational therapy in her professional life:

She explained it very nicely. It was really something I think I will bring with me for later … to keep in mind what that job is all about; I probably would not have known that without this project. I would not have seen that “Oh, occupational therapy can be used in that way” or link it to collaboration.

Initially, Oda highlighted that she did not see the relevance of learning from the other students in the group. However, through her interaction with the interviewer, she seems to extend the boundaries of discourse “about children” by acknowledging the relevance of the occupational therapy student’s knowledge. The other student positioned herself as a speaker with relevant knowledge within the group, which eventually led Oda to not only accept but appreciate her contribution. This suggests that with different explorations, and thus positionings, the discussions could have developed differently.

The students’ perceptions of the topic’s relevance to their own education and the education of others in the group impacted their positioning in the group work, which in turn influenced their contributions to the group. However, this interpretation does not portray the whole picture. A third theme emerged that exemplifies a different approach to negotiating positions within the group.

3.3 “I can contribute with something else”: the “with children” aspect

The primary account presented by the student participants is that they contributed to the learning activity based on the knowledge they brought with them “about children” from their own curricula and positioned themselves and others accordingly. However, the INTERACT curriculum centres work “with children”, not just “about children”. The “with children” portion of the INTERACT programme syllabus comprises both ethical and legal aspects of children’s right to be informed and participate in cooperation with professionals. The curriculum focuses on approaches to talking with children that provide opportunities for them to discuss everyday experiences as well as potentially stressful events. The “with children” aspect of the programme seemed more difficult to establish as common ground in the groups, but it also led some students to contest the initially narrow and vague discourse “about children”. By bringing in the aim of working “with children”, students created new positionings for themselves and others within the group.

In the interviews, some students described how they and others had actively participated in the group despite their lack of direct knowledge “about children”. These students were able to draw relevant parallels between the INTERACT programme and other parts of their curricula. Moreover, they actively engaged in negotiations about the relevance of their professional knowledge for the IPE group. The ability to use prior knowledge from a broader field and reflect on its relevance enabled students to actively participate in the group. For example, nursing student Magnus did not accept the premise that he had little to contribute within the IPE setting:

Perhaps I did not know as much about rules and regulations as the child welfare student did, and that was something I think the physiotherapy student also had thoughts about. But we had the “human perspective” on our side.

Magnus explained further:

With so many different professional groups attending, as far as I remember everyone got to contribute with their perspectives since everyone had something relevant in their studies.

In these statements, Magnus contests positioning into a participant that preferably should “have the right to hear”. Rather, he emphasises that every participant could contribute relevant knowledge from their study programme, and he foregrounds the human perspective, which includes not just work “about” but also “with” children (and others). Other students pointed to communication with children as participatory partners in cooperation with professionals as an area of prior knowledge from their respective study programmes. They recognised this aspect of professional and interprofessional work as relevant to the INTERACT programme. Social work student Mie said:

We have a lot of focus on user participation and communication and things like that, so I felt I could contribute quite a lot there. Even if we had not had much about children and young people, this is a general way to work whether it is with children or adults or…

By introducing communication and participation as relevant themes in her group, Mie positioned herself as having “the right to speak” even while downplaying her expertise “about children”. Physiotherapy student Julie also foregrounded her competence in communication and user participation and argued that these general areas of knowledge were transferable to work with and about children. Child welfare student Diya reported that though the nurse and social work student in her group did not have strong prior knowledge about collaborating with children, “they learned a lot” in INTERACT. However, she also stated:

I felt that we controlled the conversation (…), that those who had some pre-knowledge could easily control the whole issue, I felt it that way.

According to Diya, the right to speak was earned through prior knowledge, and it was easy to dominate the positioning processes in the group by claiming prior expertise. Diya did not initially understand why physiotherapy students were participating in the group, but when the physiotherapy student in her group shared his perspective, she realised, “Of course, he sees it like this”. She observed that the physiotherapy student was able to contribute his perspective despite his assertion that he could not see how he could relate to the topic. Diya explained:

I think he was very clever, so he managed to reason or analyse himself into it. Despite him thinking that what was presented in INTERACT was all very new to him, he still explained how he could use it, if he were to have a patient, to see or capture things that he would not otherwise have been able to. So, it was very interesting. Maybe that was also the intention of INTERACT; why it is so important that you cooperate.

Both Magnus and Diya provide examples of students contesting the inherently limiting understanding of the relevance of their professional knowledge by actively contributing to the IPL setting with their own perspectives. However, doing so required these students to reflect on how their prior knowledge can be relevant in the context of INTERACT and contest the immediate dominance of the “about children” discourse. By insisting on their right to speak, some students expanded upon the valid contributions in their groups and enriched the discussion and learning opportunities of the group members.

4 Discussion and concluding remarks

The overarching aim of this study is to contribute to a knowledge base serving the development of broad IPE initiatives. We have carried out theoretically informed analyses of students’ accounts of their participation in broad interprofessional learning groups, using sociocultural theories of learning as well as the positioning theory concepts of “the right to hear” and “the right to speak”. We find the two theory traditions highly compatible as they point out interactions as the analytic nexus embracing both learning and power aspects of the group works. The results indicate that the individual students’ discursive initiatives and potential impact in the IPL groups were both closely connected to knowledge acquired in their respective professional study programmes, as well as to group negotiations concerning which aspects of the students’ emergent professional knowledge that were considered relevant to the groups’ assignments. These negotiations established premises regarding how and with which knowledge the students could contribute to the interactions in the groups.

It is the pedagogical implications of the results that will be foregrounded in this section. To do so we will first, however, turn our focus once more to what appears from this study to be two important aspects of the students’ meaning making and positioning processes in IPE: the students’ constructions of their joint task and their negotiations of the relevance of their emerging professional knowledge. These aspects correspond with the how approach of the three research questions, as presented in in the introduction section.

4.1 Students’ constructions and negotiations of relevance in IPE

Systematic reviews have shown that customization of IPE can be difficult due to the varying characteristics, abilities, and viewpoints of participating students (Reeves et al., 2016; Hean et al., 2018). This is unsurprising since IPE by nature involves the subject-specific theoretical underpinnings of the participating study programmes (Lindqvist et al., 2019). However, it is still a point worth to linger on for developers of IPE in general, and perhaps even more so for developers of broad IPE. One thing is how the theoretical underpinnings and students’ prior knowledge connects with the IPE programme in question. Another is, as we have seen here, the impact of the constructions and negotiations of relevance that students in IPE carry out during work in interprofessional learning groups. What our study shows is that even if an IPE programme is developed with relevance and authenticity (Hammick et al., 2007) for all participants in mind, it may not be perceived as such by the participants. Our study suggests that equally important to what students enter the meetings with, are the students’ constructions and corresponding negotiations of the relevance of each participants’ possible knowledge contributions to work in IPL groups. The negotiations of relevance also position the participants in the group interactions and sets conditions for further work.

The students’ accounts of the group interactions in this study showed how the students’ joint constructions of what INTERACT “is about” became pertinent to how the interactions were enacted in the groups. In many of the IPL groups the constructions of what INTERACT was about created discourses of IPC “about children” that established which knowledge contributions were considered relevant to the group’s work. By foregrounding children as the category of people involved, the students quickly turned their attention towards what they, as well as the others, knew or not knew “about” this delimited group. How children may also be positioned in categories of gender, ethnicity, social class, disabilities etc., which would modify a general child picture, does not seem to be actualised in the group discussions. Through the lens of the positioning theory concepts of “the right to speak” and “the right to hear” we moreover saw how these constructions affected students’ positionings, and thus, participations in the groups. However, the results also revealed that some students were able to expand the dominant discursive constructions by introducing alternative themes into the conversation. By extending the discursive constructions of the common issue from “about children” to include “with children”, students could open the group interactions to broader participation. The children/child category were replaced by the “participant” or even “human” (Magnus) category which created new perspectives and made new points relevant in the group work. This made other positionings possible. In this way, the students’ constructions of the issue at hand were both limiting and expanding, and could either constrain or encourage students’ participation in the group.

These results align with the study of Green (2013) presented in the introduction section. In his study Green saw that students participating in IPE could construct the interprofessional aspects in different ways. In both Green’s and in the present study, students’ constructions come across as vital. Our results also point to processes whereby the students use the interprofessional group work as an opportunity to negotiate how an interprofessional context may incorporate knowledge acquired within uniprofessional educational frames. These collective meaning-making processes extend the students’ application of established knowledge, and also offer an experience of how acquired knowledge may be further developed in new contexts. Rather than posing a threat to students’ uniprofessional knowledge, these processes provide them with experience of negotiating and accommodating acquired knowledge in new situations. The awareness raised to the ways in which students in IPE construct the IPE activity, and act accordingly, may suggest that developers of IPE ought to take such elements into account when developing IPE. This may be particularly important for the development of IPE programmes comprising students across a broad array of disciplines.

4.2 What kind of support is needed?

A pedagogical implication of our results is the importance of providing sufficient pedagogical support both in advance of and during the delivery of IPE to students across a broad spectrum of disciplines. Respective programme staff ought to prepare their students for the IPE activity by explaining how the professional programmes involved may relate to the interprofessional programme, thus creating a constructive platform for positioning processes.

The study results moreover emphasise the importance of seeing the IPE programme as part of students’ educational journeys, and to pay attention to the individual programme’s underlying understandings during programme intern preparation for the interprofessional sessions. This would be especially important within broad IPE programmes recruiting participants with various disciplinary platforms when it comes to the philosophy of science, methodological approaches and methods for investigations and interventions into a variety of challenges in a person’s life. Broad interprofessional education demand attention towards underlying professional conditions, mutual expectations and pre/post work being carried out in each of the professional programmes. We see the actualizing of several, relevant perspectives as a pertinent part of the preparatory work that ought to be carried out in the respective professional programmes. This may, however, demand a more explicit theoretical and meta-theoretical approach in each of the involved programmes. Such preparatory work may not necessarily mean that all students must work on the same texts, but that the curricula are embracing theoretical points that support the students’ more overarching reasonings.

The results also point to a need for carefully planned pedagogical support to help students develop constructive platforms for positioning in IPL groups during the meetings. In our study we have seen that processes of positioning occurred that affected students’ participation in the groups. The analytic approach taken in this project may, however, itself be of pedagogic use when supporting students before and during meetings in IPE. We found that the application of the positioning theory concepts of “the right to hear” and “the right to speak”, enlightened our analyses of group processes in constructive ways. They directed our gaze towards central aspects of the group interactions. We thus believe that these concepts can also be useful in the development phase of IPE, as well as when supporting students during the meetings. The concepts may be helpful to explore group negotiation processes in order to look into the kinds of arguments, understandings and positioning strategies that are likely to come to the fore in the actual IPE constellation. These will probably vary according to the character of the joint task and the group composition, and thus have to be tailored accordingly, but this way of analysing the situation may be helpful in establishing novel interprofessional learning constellations. This may also exemplify how the development of an analytic framework can add to a qualitative study’s transferability (Lincoln and Guba, 1985), that is, aspects with potential for generalisation beyond the study at hand.

To conclude; the use of a theoretically informed analytical process in this study, has enabled us to become aware of particular aspects of students’ participation in broad IPE that may affect the delivery of such programmes. We have seen that ways in which students participate in INTERACT is intricately linked to positioning processes where the students’ constructions of the task they are working on, and negotiations of the relevance of their emerging professional knowledge for this task, are central elements. We consider these results as “warranted assertions” (Dewey, 1941). This means that even though the results are specific to this particular transactional situation, the systematically produced understandings of the involved processes may be useful in other situations by guiding observations. We find that such situations may both be IPE programmes in general, or broad IPE programmes, more particularly. A main claim deriving from this study is that to provide sufficient pedagogical support in advance of, as well as during, the delivery of IPE, is crucial for the success of such programmes. Such support ought to help students establish constructive platforms for negotiation processes, as well as positioning. This may in turn require a particular focus on the constructions the students create of relevant knowledge, as well as valid ways of presenting and handling it in the group work.

4.3 Strengths and limitations of the study

There are strengths and limitations to this study, which should be taken into consideration when reflecting on its results.

On the strong side, the involvement of students from a broad field of study programmes should be underlined. Their display of the wide variety of disciplinary and professional approaches face developers of IPE programmes with other challenges than those present in more homogenous groups, for example groups comprising exclusively health care students. However, the explicit challenges brought to the fore through greater variation among the participants, may also contribute to a more elucidating discussion for the good of the entire IPE field.

Worth mentioning is also the interview’s focus on the students’ accounts of what happened in the groups as a starting point. The accounts about “what happened” are not classified as “true descriptions”, rather as starting points for joint explorations into the interviewee’s understanding of processes in the groups. Starting with the interviewee’s own words about what happened in the groups establishes a productive context for the interaction between interviewer and interviewee, and it opens fields of reflection. By its potential for pointing out novel aspects of the theme at stake, this approach differs from the use of detailed, preconstructed interview guides.

A limitation to the study may be its number of participants. Even if a sample of 15 may give a useful insight into key processes in the IPE groups’ work, a larger number of participants could obviously have added points to the analyses. Another potential limitation may be the gap in time between the first INTERACT module and the interviews, which may have affected the students’ recollections of their participation.

Further research in the field would benefit from greater samples and, not the least, of a longitudinal design. With IPE programmes, like INTERACT, following students through (three) years, group observations and regular interviews before and after each module could give more insight into students’ pre- and post-understandings of IPE each year, how students from different programmes handle their IPE experiences within their programme internal activities, and how a recognition of other professionals’ contribution in joint, professional efforts with and about children can develop.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because this is not in line with the informed consent provided by the research participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to KB, a2FqYWJyYWFAb3Nsb21ldC5ubw==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Norwegian Centre for Research Data. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KB designed the study and collected the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KB and LMG performed the data analysis. Both authors revised the manuscript, contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The publication of this article was funded by the Oslo Metropolitan University’s publication fund.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the interview participants for the time and effort they put into this research project. We would also like to thank the reviewers and the associate editor for their valuable feedback improving the manuscript. Thanks also to Ellen Merethe Magnus for sharing her knowledge about INTERACT with us and for her support during the data collection work. A thank you also goes to Sissel Seim who kindly commented on the final draft of the manuscript. Finally, a special thank you goes to Finn Aarsæther for his continuous support throughout the work with this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1249946/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The 0–24 collaboration is a cross-sectoral collaborative project that aims to achieve better coordinated, more streamlined services for vulnerable children and young people. The collaborative partners for 0–24 include the Norwegian Directorate of Health; the Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs; the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration; the Directorate of Integration and Diversity; and the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (Information booklet 0–24).

3. ^Approval number 550428.

4. ^Except for physiotherapy and nursing students, who were in their fourth term.

References

Barr, G., HelmeM, R., Low, H., and Reeves, S. (2016). Steering the development of interprofessional education. J. Interprof. Care 30, 549–552. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2016.1217686

Braathen, K. (2022). Measuring outcomes of Interprofessional education: a validation study of the self-assessment of collaboration skills measure. Profess. Professional. 12:4307. doi: 10.7577/pp.4307

Brinkmann, S., and Kvale, S. (2015). InterViews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing, 3rd, SAGE

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

CAIPE. (2016). Statement of purpose CAIPE 2016. Retrieved 27 November, 2020, Available at: www.caipe.org

Clark, P. G. (2006). What would a theory of interprofessional education look like? Some suggestions for developing a theoretical framework for teamwork training. J. Interprof. Care 20, 577–589. doi: 10.1080/13561820600916717

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. R. B. (2018). Research methods in education. 8th Edn Routledge.

Davies, B., and Harré, R. (1990). Positioning: the discursive production of selves. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 20, 43–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5914.1990.tb00174.x

Dewey, J. (1941). Propositions, warranted assertibility, and truth. J. Philos. 38, 169–186. doi: 10.2307/2017978

Edwards, A. (2012). The role of common knowledge in achieving collaboration across practices. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 1, 22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2012.03.003

Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z. A., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., et al. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. London, New York.

Green, C. (2013). Relative distancing: a grounded theory of how learners negotiate the interprofessional. J. Interprof. Care 27, 34–42. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2012.720313

Hammick, M., Freeth, D., Koppel, I., Reeves, S., and Barr, H. (2007). A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME guide no. 9. Med. Teach. 29, 735–751. doi: 10.1080/01421590701682576

Hansen, I L S., Jensen, RS., Strand, A H H., Brodtkorb, E., and Sverdrup, S, (2018). Nordic 0–24 collaboration on improved services to vulnerable children and young people. First interim report.

Harré, R., and Langenhove, L., (1999a). The dynamics of social episodes. Positioning theory: moral contexts of intentional action (1–14). Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Harré, R., and Langenhove, L., (1999b). Introducing positioning theory. Positioning theory: moral contexts of intentional action (14–32). Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Hean, S., Green, C., Anderson, E., Morris, D., John, C., Pitt, R., et al. (2018). The contribution of theory to the design, delivery, and evaluation of interprofessional curricula: BEME guide No. 49. Med. Teach. 40, 542–558. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1432851

Lawn, S. (2016). Moving the interprofessional education research agenda beyond the limits of evaluating student satisfaction. J. Res. Interprof. Pract. Educ. 6:239. doi: 10.22230/jripe.2017v6n2a239

Lindqvist, S., Vasset, F., Iversen, H. P., Hofseth Almås, S., Willumsen, E., and Ødegård, A. (2019). University teachers’ views of interprofessional learning and their role in achieving outcomes - a qualitative study. J. Interprof. Care 33, 190–199. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2018.1534809

Molloy, E. K., Greenstock, L., Fiddes, P., Fraser, C., and Brooks, P. (2014). Interprofessional education in the health workplace. S. Billett, C. Harteis, and H. Gruber (Eds.), International handbook of research in professional and practice-based learning (535–559). Springer, Netherlands

NBHS. (2018). Barnets synspunkt når ikke frem: Oppsummeringsrapport etter lands-omfattende tilsyn med Bufetat 2017 [the voice of the child is not heard: summary of countrywide supervision in 2017 of the Norwegian Directorate for Children, youth and family affairs (Bufetat)] (3/2018). Available at: https://www.helsetilsynet.no/globalassets/opplastinger/publikasjoner/rapporter2018/helsetilsynetrapport3_2018.Pdf

NBHS. (2019). Når barn trenger mer Omsorg og rammer (When children need more, care and frameworks) (9/2019). Available at: https://www.helsetilsynet.no/en/publications/report-of-the-norwegian-board-of-health-supervision/2019/care-and-frameworks-when-children-need-more/

Packer, M. J., and Goicoechea, J. (2000). Sociocultural and constructivist theories of learning: ontology, not just epistemology. Educ. Psychol. 35, 227–241. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3504_02

Potter, J., and Wetherell, M. (1987). Discourse and social psychology: beyond attitudes and behaviour. SAGE.

Prop. 100 L (2020–2021). (2021). Endringer i velferdstjenestelovgivningen (samarbeid, samordning og barnekoordinator) [changes in welfare service legislation (collaboration, coordination and children’s coordinator)]. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/prop.-100-l-20202021/id2838338/?ch=1

Reeves, S., Fletcher, S., Barr, H., Birch, I., Boet, S., Davies, N., et al. (2016). A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME guide No. 39. Med. Teach. 38, 656–668. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173663

Report No. 13 (2011–2012). (2011), Utdanning for velferd [Education for welfare: Interaction as key]. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld-st-13-20112012/id672836/

Report No. 20 (2012–2013). (2012), På rett vei (On the right track). Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld-st-20-20122013/id717308/

Tan, S.-L., and Moghaddam, F. M. (1999). Positioning in intergroup relations. R. Harré and L. v. Langenhove (Eds.), Positioning theory: moral contexts of intentional action (178–195). Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Thistlethwaite, J., and Xyrichis, A. (2022). Forecasting interprofessional education and collaborative practice: towards a dystopian or utopian future? J. Interprof. Care 36, 165–167. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2022.2056696

Ulvik, O. S., and Gulbrandsen, L. M. (2015). Exploring children’s everyday life: an examination of professional practices. Nordic Psychol. 67, 210–224. doi: 10.1080/19012276.2015.1062257

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. (1990), Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx

Keywords: interprofessional education, interprofessional collaboration, positioning theory, meaning-making, IPE with children and young people, qualitative study

Citation: Braathen K and Gulbrandsen LM (2023) Students’ meaning-making processes in an IPE programme with students from education-, health-, and social care programmes. A qualitative study. Front. Educ. 8:1249946. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1249946

Edited by:

Samuel Edelbring, Örebro University, SwedenReviewed by:

Helen Setterud, Linköping University Hospital, SwedenTuija Viking, University West, Sweden

Copyright © 2023 Braathen and Gulbrandsen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kaja Braathen, a2FqYWJyYWFAb3Nsb21ldC5ubw==

Kaja Braathen

Kaja Braathen Liv Mette Gulbrandsen

Liv Mette Gulbrandsen