95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 05 October 2023

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1240782

This article is part of the Research Topic Disciplinary Aesthetics: the Role of Taste and Affect for Teaching and Learning Specific School Subjects View all 11 articles

Food is a part of everyday life, and formal food education is included in compulsory education in many countries, for example through the subject Home and Consumer Studies (HCS). While food education is often underpinned by public health concerns such as preventing non-communicable diseases and promoting cooking skills, there has been little focus on aesthetic aspects of teaching and learning about food. This study therefore aims to gain understanding of aesthetic values as a part of HCS food educational practices. Aesthetic values are here regarded as socially and culturally shared, and related to notions of pleasure and taste. As this study uses a pragmatist approach, aesthetic values are seen as constituted in encounters, encompassing experiencing individual(s), artifacts, and context. By thematically analyzing empirical data from an exploratory case study, including classroom observations, student focus groups, and teacher interviews, we show how values are constituted as culinary, production, and bodily aesthetics. Culinary aesthetics involved cooking processes, cooking skills, and presentation of food and meals. Production aesthetics involved foods’ origin and degree of pre-processing, whereas bodily aesthetics related to bodily consequences of eating. Aesthetic values were vital features of the educational practices studied and played a key role in bringing the practices forward. They also indicated what counted as valid, or desired, outcomes and thereby steered events in certain directions. The study highlights the significance of aesthetic values and argues in favor of acknowledging aesthetics in planning, undertaking, and evaluating HCS food education.

In this paper, we investigate how aesthetic values come into play in food education within the school subject Home and Consumer Studies (HCS). The investigation highlights aesthetic aspects of food education that are often invisible and/or taken for granted. By increasing awareness of the aesthetics that guide and shape HCS food education, this study can contribute to future development of food educational practices.

Since food is a part of everyday life, food education takes place in home kitchens and other settings, both informal and formal. Formal food education in schools varies in scope, design, and teaching methods, depending on cultures and traditions (Kauppinen and Palojoki, 2023). The school subject HCS, internationally known as Home Economics, is one example of formal food education in compulsory school. When the subject was introduced in U.S. and European schools in the late 19th century, the purpose was to prepare women for their domestic roles through lessons in economy, cooking, nutrition, cleaning, and textile care (Mennell et al., 1992). HCS served to spread new scientific knowledge about healthy eating to the public, and another purpose was to educate women in the bourgeois virtues of entertaining and representing through food (Shapiro, 2008). Though the subject’s contents have changed over the years – in different directions in different countries – it still has food education at its core (Pendergast, 2008). In Sweden, HCS (Hem-och konsumentkunskap) is permeated by three perspectives: health, finance, and the environment. It concerns not only cooking, but also nutrition, meal planning, budgeting, and environmental labelling (Skolverket, 2011/2019).

Contemporary arguments for including food education in schools are often underpinned by public health concerns such as prevention of non-communicable diseases [(e.g., Lichtenstein and Ludwig, 2010; Lavelle et al., 2016)] and concerns related to environmental sustainability [(e.g., Williams and Brown, 2013)]. Here, the importance of conveying nutritional knowledge and cooking skills is commonly underlined. However, a rigid focus on these instrumental aspects of food and eating leaves little room for reflection upon experience-based perspectives (Rich and Evans, 2015). Food can evoke experiences of pleasure and delight as well as displeasure and disgust, which can be explored through the lens of aesthetics (Brønnum Carlsen, 2004). In recent years, aesthetics has been the subject of increasing academic interest within the field of education. For example, empirical research has investigated the role of aesthetics in teaching and learning within school subjects like elementary school science (Caiman and Jakobson, 2022), data modelling (Ferguson et al., 2022), and grammar (Ainsworth and Bell, 2020). Although these studies were generated from differing educational contexts, they all showed how aesthetic experiences – including intellectual, practical, and emotional aspects – were integral to educational processes.

The concept of aesthetics originates from the Greek word “aisthesis,” which means sense perception (Freeland, 2012). With a focus on the senses, aesthetics is broadly interpreted in two ways: as a theory of fine art and as a branch of philosophy which concerns the study of beauty, pleasure, and taste (Shusterman, 1999). Though the senses have been the subject of philosophical inquiry since classical antiquity, food was long excluded from these discussions. The exclusion of food can partly be attributed to the traditional philosophical distinction between higher and lower senses, i.e., the view that (gustatory) taste, smell, and touch are inferior to sight and hearing (Korsmeyer, 1999). A significant shift came with “Art as experience,” in which Dewey (1934/2005) made an argument for the aesthetic relevance of food by stressing that aesthetics encompasses every aspect of human experience, including food. He also gave gustatory taste relevance by rejecting the hierarchy of the senses. Korsmeyer’s influential work “Making sense of taste” (1999) can be seen as another landmark which paved the way for increased academic interest in food aesthetics (Pryba, 2016).

Taste holds a central standing as a signifier of aesthetic appreciation, but has double meanings with respect to food. It has an everyday use to describe and/or evaluate gustatory qualities, i.e., how food tastes in our mouths. From an aesthetic point of view, however, taste needs to be considered in a broader sense than merely the gustatory – as a socially situated phenomenon used to define and distinguish between groups of people (Bourdieu, 1987). Using the Bourdieusian view of taste as a part of individuals’ cultural capital, taste can be described as an “identity marker that facilitates interactions” (DiMaggio, 1987, p. 443). Hence, in relation to food, taste encompasses both personal gustatory qualities and contextually shared norms and values (Korsmeyer, 2017). Moreover, taste is not pre-existing within individuals, but shaped by class, education, and other sociocultural forces (Gronow, 1997).

According to Warde (2016), there has been a growing interest in aesthetic aspects of food in the Western world – an “aestheticization” of eating, which he attributes to the increased interest in eating outside the home (e.g., restaurants). Not only has there been a rise in restaurants offering innovative cuisine in the last decades, but there has also been an increase in entertainment such as television shows and competitions focused on cooking (Sweeney, 2012). Likewise, the rise of digital and social media has made visual food aesthetics even more accessible to the public. The visual representations of food in the media create aesthetic values regarding both legitimate and illegitimate meals and lifestyles (Krogager and Leer, 2021). Thus, food aesthetics is dynamic, constantly changing, and exists in multiple forms simultaneously.

In a study of teachers’ food selection in Swedish HCS, Höijer et al. (2014) showed how HCS teachers valued certain foods above others, and that culture and tradition played a role in their food selection. This valuing and selection of certain foods to include in the subject’s contents can be regarded as contributing to HCS disciplinary aesthetics (cf. Wickman et al., 2022). More recently, Bohm (2022) explored cultural connections between Swedish HCS and the home. Here, contradictory aesthetic values were reported in observations of HCS classrooms. The classrooms’ interior design promoted one type of food (nutritious and environmentally friendly) while storage spaces contained other (nutrient-poor) foods. In another study, Bohm et al. (2023) showed how sweet foods were inconsistently valued in HCS – as fun and desirable, but also as unnecessary and disgusting. These studies did not target aesthetics as a main aim. However, they implicitly highlighted the presence and influence of aesthetics in HCS food educational practices.

When it comes to HCS food education, aesthetics can be considered a “secret ingredient,” as there are few empirical studies which explicitly focus on the roles that aesthetics play within these practices. In a previous paper, we investigated students’ cooking in HCS and showed how aesthetic judgments were used to bring the practices forward and directed the students’ meaning-making (Berg et al., 2019). However, HCS food education encompasses more than cooking, and the present study sets out to further explore aesthetics within the subject. The aim of this paper is to gain understanding of aesthetic values as a part of HCS food educational practices. The investigation is based on a case study and guided by the research question: What aesthetic values are central when teachers and students engage with food in HCS educational contexts, and how do these aesthetic values come into play?

In the present study, we adopt a pragmatist approach, meaning that the focus is on actions taking place within the practices under investigation, as outlined by Biesta and Burbules (2003). This approach draws on Dewey’s (1934/2005) concept of “experience,” which provides a comprehensive description of the processes in which individuals actively engage with the surrounding world. From the Deweyan perspective, aesthetic experiences involving food are not only affected by appetite and the context of the encounter, but shaped by a broader context which include previous encounters. These previous encounters are re-actualized (Lidar et al., 2010), meaning that they are brought into our current experience and influence how we perceive and engage with food. Likewise, the “current” experience will affect how similar food encounters will be experienced in the future. This continuous quality of experiences is what Dewey (1938/2007) refers to as “the principle of continuity.” In addition to being continuous, aesthetic experiences are regarded as context-specific, and inseparable from feelings. Hence, aesthetic experiences encompass emotional aspects which can be described as aesthetic feelings (Prain et al., 2022). Aesthetic feelings contribute to the richness, depth, and transformative power of an experience in the sense that they re-actualize how one feels in relation to the object or event that is being experienced. Thus, aesthetic experiences can change relational conditions as well as courses of events.

As a part of educational practices, aesthetics can play a role in the privileging of educational content, i.e., the process of including certain aspects (questions, artefacts, etc.) and ignoring others (Wertsch, 1991). By influencing what content is included and not, privileging processes govern the learning in certain directions (Van Poeck et al., 2019). As such, aesthetic experiences have normative implications: they distinguish personal likes and dislikes, but also what belongs and does not belong within a shared practice (Wickman, 2006). Consequently, students do not only learn a subject’s contents – they learn values tied to the practice and how to relate to these values (Anderhag et al., 2015).

Productive participation in different activities requires making aesthetic distinctions of what is or is not valued as a part of each activity (Wickman, 2006). We assume that the process of making such aesthetic distinctions can be empirically investigated by studying events where aesthetic values come into play. With the pragmatist approach, we understand aesthetic values as “(…) socially and culturally shared, contextualized within shared practices within a community, and they exert themselves by determining what should be considered worthwhile, important, and useful” (Sinclair, 2009, p. 55). Accordingly, the focus of the present study is on aesthetic values as contextual: situated and constituted in transactions. Moreover, aesthetic values are not treated as inherent properties of food, but rather as relations which are created through – and inseparable from – actions. Hence, aesthetic values are not exclusively tied to a subject (the one who values) or object (that which is being valued), but constituted through the transactions that take place in encounters involving subject, object, and context. With this transactional understanding, aesthetic values encompass the experiencing individual(s), the food, and the context in which the valuation takes place (cf. Brønnum Carlsen, 2004).

The findings reported in this paper are part of a more comprehensive study investigating teaching and learning about food, meals, and health in the school subject HCS. In that study, data have been generated through empirical fieldwork following an exploratory, single-case study design (Yin, 2018). It was conducted in a Swedish school at the compulsory level and comprised one school class and two HCS teachers. A range of qualitative data generation methods were used, with data included in the analyses for this paper generated through video-recorded classroom observations, student focus groups, and teacher interviews (Table 1).

Recruitment was undertaken using a critical case selection rationale (Yin, 2018). In order to obtain favorable conditions for investigating HCS-specific teaching and learning processes, three strategic inclusion criteria were set:

i. Formally qualified teacher(s) with several years of working experience and a pronounced interest of working with food, meals, and health education.

ii. Communicative students who were assumed to have good chances to achieve curricular goals.

iii. Functional classroom(s) with fully equipped kitchen units.

With this selection, the likelihood of disruptive moments occurring in the classroom was less. Purposive sampling resulted in the recruitment of two teachers working at a school located in a socio-economically advantaged area in one of Sweden’s largest cities. The two teachers were aged 55–60 years, and both had more than 20 years of working experience as qualified HCS teachers. Informed by the inclusion criteria stated above, the teachers suggested a school class for participation. After being informed about the study and invited to participate, twelve students aged 14–15 years were included, and the first author observed their participation in HCS throughout the school year 2017/2018.

A pilot study was initially conducted, consisting of one classroom observation. The purpose was to get acquainted with the research setting and the technical equipment. The pilot study included one of the recruited teachers and one school class, though not the one recruited to the main study. The pilot study was documented with fieldnotes, and four students were video-recorded while cooking. Data from the pilot were excluded from the main study but resulted in refinement of the study design and use of the technical equipment.

Subsequently, thirty-six classroom observations of HCS lessons were undertaken. The observations followed guidelines by Angrosino (2012) and were documented with fieldnotes, audio recordings, and video recordings. The video recordings adhered to recommendations made by Luff and Heath (2012) concerning how to conduct video observations of two to three people in semi-public settings. Accordingly, an open camera angle was used with a fixed camera placed on a tripod (i.e., a stable mid-shot). During each observation, two video cameras were placed at two separate kitchen units, and the recordings started when the students went to their assigned kitchen units. Each recording includes two students cooking together, except for one recording with only one student.

Ten of the participating students were included in focus groups, with four sessions held during the school year. The teachers were interviewed on four separate occasions each, which resulted in eight interviews. All interviews were semi-structured, building on guidelines by Magnusson and Marecek (2015), and covered broad topics such as teaching, learning, and evaluation.

The two teachers each had their own classroom. Each teacher taught half a school class at a time, as the classes were split in two. The HCS classrooms contained eight kitchen units, a refrigerator, a freezer, a dishwasher, and a small office space. In addition, many details distinguished the HCS classrooms from the school’s other classrooms. First, they stood out in a spatial sense as to how they were located: separated from other classrooms, at the top of the school building. Second, they were decorated in a homey way. There were kitchen curtains and flowers in the windows. School desks were placed together to form a big table in the middle of each classroom, resembling a dining table, where the students ate the food that they prepared. The walls were filled with posters of meals, fruits, and vegetables.

The HCS lessons generally followed the same rhythm in both classrooms and over the school year. They started with the students sitting down at the big table and the teacher welcoming them, presenting the subject of the day, and lecturing on different topics such as nutrients, sustainable food consumption, or food’s role in prevention of non-communicable diseases. This part typically ended with the teacher presenting the recipe of the dish that was about to be prepared. During the lectures, the students were sometimes talkative, but they usually seemed to pay attention to what the teacher said, taking notes and asking follow-up questions. Next, the students were paired up and went to their assigned kitchen units. Here, the classroom was filled with sounds, smells, and sights of students eagerly working to prepare their food. The energy level in the room was generally high, as students talked with excited voices, laughed, and sometimes argued during the cooking process. The lessons usually ended in a calmer fashion, with the students once again gathered around the big table to eat their food and summarize the lesson together with the teacher.

The analysis started in the data-generating process, where the first author became familiarized with the participants and the studied practices. Once the empirical fieldwork was conducted, the first author transcribed all the data from teacher interviews and student focus groups verbatim. Audio data from the observations were transcribed except in cases of private conversations or strictly practical matters, such as placement and grouping of students. Due to the substantial amount of data, video data from the observations were only partly transcribed. Here, consideration was taken to adhere to the research interest, which for the present study meant transcribing selected events in which aesthetic values could be discerned clearly. Consequently, the transcriptions of video data mainly involved spoken word but sometimes also included visible nonverbal actions such as gestures, facial expressions, body language, and movements through the room.

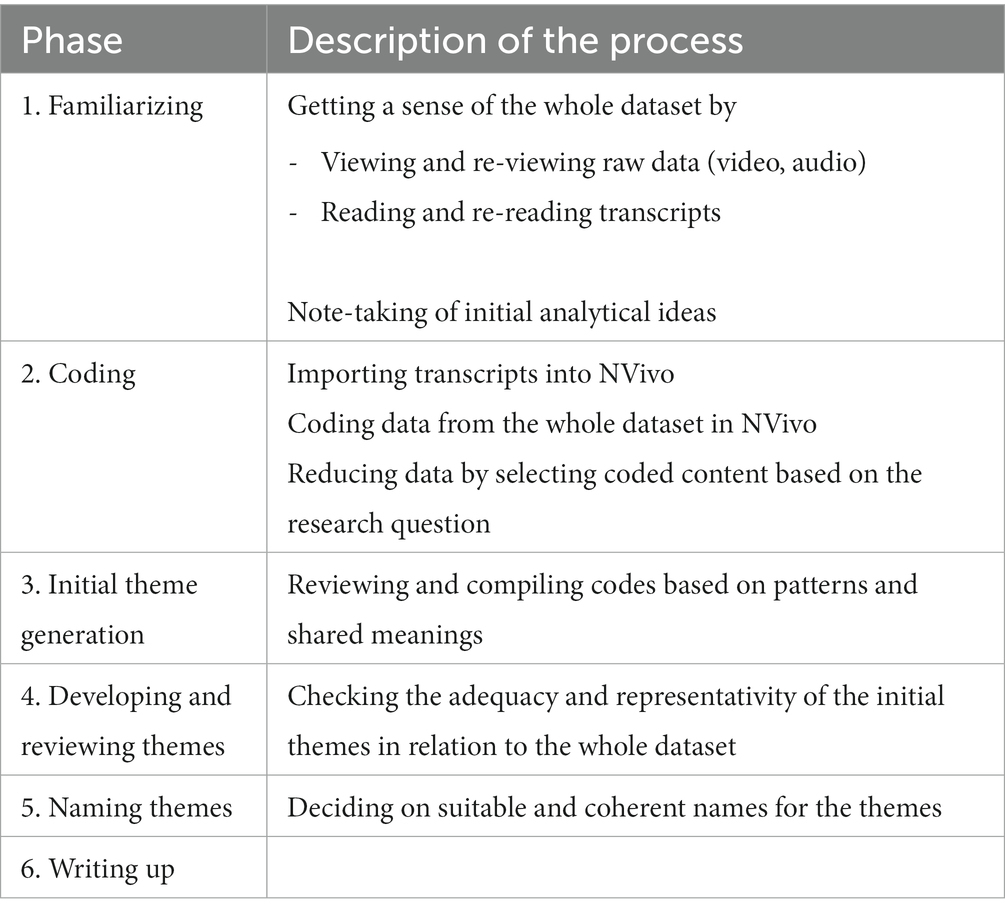

The transcripts were analyzed through reflexive thematic analysis, using the principles of Braun and Clarke (2021). Accordingly, the analysis process covered six phases (Table 2). The coding and theme generation, phases 2–4, were performed using the software program NVivo11 (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2015). The phases were not strictly linear, with the researcher(s) going back and forth between them, revisiting the raw data and transcripts regularly to check for adequacy and consistency, in line with the reflexive approach described by Braun and Clarke (2021). During the reading of transcripts, specific attention was paid to aesthetic values and how they came into play. Thus, the focus was on situated practices, and the aesthetic values constituted therein. To operationalize aesthetic values, we looked for situated practices where signs of immediate aesthetic feelings could be observed, but also more indirect evaluative statements with aesthetic qualities, such as those dealing with taste/distaste. This way of regarding aesthetic values generated both semantic and latent level coding. To exemplify, a semantic code including an evaluative statement was “I’d rather have a tasty meal than a nice-looking meal” (student 1, focus group 4). Latent codes included events or series of events in which aesthetic values were perceived more implicitly. One example of a latent code which included signs of immediate aesthetic feelings was when one student during an observation exclaimed to her classmate, with despair in her voice: “I’ll get diabetes. Do you know how much sugar I’ve had? I do not want to get diabetes.” (student 2, observation 13b).

Table 2. Summary of the analytical phases [based on Braun and Clarke, 2021].

Though the first author conducted the analysis, every step of the process was discussed with the third author and revised accordingly. All three authors agreed on the contents and names of final themes.

Ethical guidelines for good research practice were followed throughout the research process (Swedish Research Council, 2017). Prior to the data generation, all participants received verbal and written information about the study. Written consent was obtained from all participants and from legal guardians for those under the age of 15 years. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala (ref. no. 2017/230).

Aesthetic values were constituted through the transactions taking place within the studied practices, where the participants’ experiences were re-actualized, negotiated, and transformed. They came into play through direct reactions to experienced objects or sensations, such as the exclamation “yuck” (student 3, observation 1a) when touching a raw fish filet. Another way was through evaluative statements, such as “You’ll get really nice MSC-labelled cod from me” (teacher 2, observation 16b).

The analysis shows how aesthetic values could be seen as relating to three themes: culinary, production, and bodily aesthetics (summarized in Table 3). Each theme illustrates a perspective from which aesthetic values related to food came into play in our empirical data.

In the analysis, aesthetic values involving cooking processes, cooking skills, and presentation of food and meals were regarded as culinary aesthetics. Culinary aesthetics was the most prominent theme throughout the studied practices, highlighted during interviews and focus group sessions as well as in observations.

When the students prepared meals, which they did during almost every observed lesson, their actions indicated a concern about making the food aesthetically appealing with regard to gustatory and visual attributes. During the cooking processes, the students followed the assigned recipes with one exception: they often added extra salt, butter, and/or sugar to their food. This was done secretively, behind the teacher’s back, and with the explicit intention of making the food taste better: “You should always have a lot of butter (…) Butter is tasty.” (student 4 when adding extra butter to the frying pan, observation 12a). However, aesthetic values regarding gustatory taste encompassed more than personal preferences, as shown when one student during an observation asked her classmate for help tasting her mashed potatoes: “Because I do not know how it’s supposed to taste, because I do not like mashed potatoes.” (student 3, observation 12a). This can be seen as a recognition of a universal aspect of aesthetic values: that there is a “right” gustatory taste which exists irrespective of one’s own opinion.

Another way that students’ actions could be seen as conforming to the “right” gustatory taste within the subject was through changing evaluative statements. For example, during one lesson, the students were assigned the task of preparing two kinds of soup and comparing them: one prefabricated soup and one with raw ingredients. While the soups simmered on the stove, student 4 told his classmate, student 1, that he thought the prefabricated potato soup would taste better than the homemade equivalent. Student 4 was immediately corrected by student 1, who loudly declared that “I do not think that the prefabricated soup is tastiest,” followed by a whisper that “[teacher’s name] said that it was horrific.” Later that same lesson, student 4 raised his hand and stated to the teacher that “I cannot finish [the prefabricated soup], this is horrific.” It is impossible to ascertain which soup student 4 preferred and if he really thought that the prefabricated soup was horrific. However, this example shows that student 4 changed his evaluative statement and used the same evaluative term that he had indirectly heard the teacher use.

In the focus group discussions, relations between visual and gustatory attributes were established, where the look of a meal served as an indicator of the gustatory taste. The students in focus group 4 agreed that visual attributes were important when cooking for others in general and in HCS in particular, but not so much when cooking only for themselves, since “then it’s just for yourself, you kind of know that it’s tasty” (student 4, focus group 4). What was considered visually appealing differed between the students, but there was a collective preference towards meals presented so that different foodstuffs were separated on different sections of the plate. Also, when plating meals, many students preferred combinations of foods with assorted colors. When asked during focus groups about their views on creating visually appealing meals, the students underlined that this was important within HCS, as their teacher “eats with her eyes” (student 5, focus group 4).

While the students related aesthetic values to visual and gustatory attributes of the meal as an end product, e.g., “it should look good” (student 6, focus group 4), the teachers primarily related aesthetic values to cooking processes, such as “one must work neatly” (teacher 1, interview 3). In this context, this meant that the kitchen was kept clean and tidy during the cooking process. One strategy that the teachers stated they used, partly to move the focus away from the end product, was not to taste the students’ food. When the students asked about that “(…) then I say that I look at the work process” (teacher 2, interview 8). Thus, the teachers had a process-oriented approach where the cooking processes were the focus, rather than the finished meals:

“(…) Then it kind of becomes a status symbol that you, that you can make food healthily, beautifully, and that you can use your knowledge and methods.” (teacher 1, interview 3)

Though the students’ main concern seemed to be the gustatory taste and visual appeal of the meal as an end product, they declared during focus group sessions that they accommodated the HCS teachers’ expectations. Examples included wiping the kitchen counter or washing up dishes during the cooking process, which the students said they would not do when cooking at home. This indicates that the students were well aware of which aesthetic values the teacher emphasized with regard to the HCS practice, and that they took action to conform to these values. Thus, the teachers played important roles in constituting aesthetic values. In the transactions taking place in the classroom, the teachers became the ones who dictated the framework for the desired aesthetic values. When it came to cooking skills, they pointed out desired directions of the practices by highlighting positive aesthetic outcomes and by presenting relations between actions and outcomes. In other words, the teachers suggested to the students how best to proceed in their cooking activities:

“The more you work this dough, the better the gluten threads. So that it’s perfect. Then when you see that the dough comes loose from the edges of the bowl, so that it becomes like a ball, then things start to get better. Then you should be able to pick up the dough and kind of roll it a little between your fingers without getting really sticky. Then it’s good.” (teacher 2, observation 8b)

During another lesson, where the task was making breaded fish, the teacher emphasized that the aim of breading fish was to make it stick together. Subsequently, when one student pair saw parts of their fish falling to pieces in the frying pan, they were quick to label the fish “ugly,” and to eat the small pieces “so that she [the teacher] does not see” (student 4, observation 1a). The students’ actions could, once again, be seen as accommodating aesthetic values that the teachers had emphasized.

Food was valued aesthetically in relation to its origin, i.e., the parts of the food systems that include primary production, processing, and transport. Where, how, and to what degree food had been processed was valued aesthetically. In general, organic foods and local food production were positively valued, whereas animal production and food imports were negatively valued. For example, regarding animal welfare, signs of aesthetic feelings included the exclamation “Ugh” when discussing animal slaughter (student 7, focus group 2). Other examples were evaluative statements such as “the meat industry is horrible” (student 7, focus group 2). Environmental concerns were also communicated in signs of aesthetic feelings, e.g., by a student exclaiming “holy shit” (student 8, observation 4b) when the teacher described the emissions of greenhouse gas from rice production, and in evaluative statements such as “tomatoes are tastiest if they get a lot of sun” (teacher 2, observation 4b).

Production aesthetics also related to the degree of industrial processing that the food had undergone. Towards the end of the Spring semester, there was a course section comprising six lessons called “homemade vs. prefabricated.” The lessons within this course section were built around comparisons between prefabricated food and food prepared by the students from raw ingredients. When interviewed, the teachers described the purpose of the lessons as training the students in making conscious choices by comparing homemade and prefabricated food with regard to price, time expenditure, and sensory attributes. These descriptions did not include valuation of the different foods. However, during the lessons, the teachers ascribed positive aesthetic values to the homemade food. The prefabricated food, on the other hand, was problematized and valued negatively: “(…) it is not necessarily really bad, but it might not taste the best” (teacher 1, observation 16a). The message conveyed seemed to be that the industry only worked to maximize profit and therefore produced cheap, artificial substances intended to taste like their “natural” equivalents:

“There aren’t any shrimp in it. It is only in the picture that they have put a shrimp on here. Kind of shameless, maybe, because the shrimp are kind of, they are one of the most expensive ingredients in this.” (teacher 1, observation 16a)

During one of the lessons, two students who cooked together were asked by the observer what they believed the purpose of the course section was. The students’ answers suggested valuation of homemade food above prefabricated food: “You’re supposed to understand that it’s better to cook homemade food.” (student 5, observation 16a). Akin to culinary aesthetics, the production aesthetic values emphasized by the teachers were reflected in students’ statements, as a skepticism towards industrially manufactured food was stressed:

“When you read the label on some meal and do not understand what it says. Then it’s… I think that’s weird.” (student 5, focus group 4)

The students stated that they would prefer what they called “real food,” even if the gustatory taste and nutrient contents of the artificial substance were exactly the same as in the natural one. When this was discussed during a focus group session, the students said that “you would rather have a kind of honest, a real taste of shrimp that are shrimp, instead of a fake powder taste” (student 3, focus group 4).

In addition to culinary and production aesthetics, aesthetic values which related food to the body were constituted. This included values regarding foods’ biomedical and emotional impact on the body. Biomedical functions of food, and biomedical consequences of eating certain foods, were valued aesthetically by teachers and students alike, using biomedical outcomes as criteria. Overall, dietary fiber, protein, unsaturated fat, and nutrient-dense foods were valued positively, while sugar, saturated fat, and nutrient-poor and energy-dense foods, were valued negatively. For example, when two students discussed dietary fat with their teacher, one student stated that eating certain fats can “create disgusting stuff” (student 2, observation 13b). This is an example of how negative aesthetic values were constituted in relation to fat’s biomedical consequences within the body. Biomedical consequences moreover encompassed physical performance and risks for non-communicable diseases. While the teachers mainly valued biomedical aspects of food in relation to bodily functions, the students used foods’ effect on the body’s visual appearance in their evaluative statements. These statements involved body weight and body shape, e.g.: “If you want to look like me, you need to eat only meat.” (student 8, observation 10b).

Some of the HCS lessons had an explicit focus on foods’ nutrient contents and the biomedical traits of nutrients. Here, aesthetic values were constituted in relation to biomedical consequences. During one lesson, teacher 2 drew a sketch on the whiteboard, depicting a diagram of a fluctuating blood sugar level and stated:

“It’s really hard for the body to have a blood sugar like this (…) Whoop, a lot of insulin, like you said. And you can die here if insulin is not produced (…) And, if you skip meals or eat a lot of sweet stuff (…) then the blood sugar levels can look like this. Not good. You do not want that. So do not skip meals. Eat vegetables. Eat good food.” (teacher 2, observation 13b)

In this event, the teacher negatively valued the visual image of the blood sugar level: “It’s really hard for the body (…) You do not want that.” This is an example of how bodily aesthetic values came to involve the interplay between bodily responses to eating certain foods on the one hand and the agency of making sound food choices on the other hand.

Among the students, aesthetic feelings related to food and eating were similarly valued by linking food and food choices to bodily responses. Through this valuation, relations between biomedical aspects of food and emotional bodily responses were created. When the students discussed foods’ capacity to evoke pleasant or unpleasant feelings, they used a dichotomy, labelling food as healthy or unhealthy. While the “unhealthy” food was sometimes related to unpleasant feelings, both the “healthy” and “unhealthy” food was framed as having the power to evoke feelings of pleasure:

“Then I eat, like, healthily. Then I become, like, super pumped and happy all day. So then, like, I put on my headphones and go out like running. Because I get pumped. I kind of use that feeling to do something. But it is kind of the opposite when I eat something unhealthy. Then I get happy too.” (student 4, focus group 3)

The students also discussed “unhealthy” food being used as a reward:

Student 6: “After you have had like a bowl of pea soup and something, that’s, I think it’s healthy… Then you feel like this that, that you have done something good. That you can kind of reward yourself or something.” Student 5: “And then you eat unhealthily. [laughs]” Student 6: “Yeah, exactly. [laughs]” (students 5 and 6, focus group 3).

During focus group 4, the students also addressed that it felt better to eat certain food because “you get another feeling” (student 6). However, they could not define this feeling further, only that “it feels better” (student 6). Overall, the students seemed to use food instrumentally, to evoke positive aesthetic feelings:

“I’ve started to eat that because, yes, I think that’s made me feel better.” (student 1, focus group 4)

While bodily aesthetic values enacted among the students were dominated by this embodied, holistic perspective, the teachers had a different way of communicating. During lessons and conversations with students, the teachers treated parts of the body as separate entities, implying that the body and its different organs had feelings of their own: “The brain and the body love carbohydrates, it is the best energy for the body.” (teacher 2, observation 9b). “Love” can here be seen as a metaphor used for pedagogical reasons, but also as a way of disembodying the food experience, where different parts of the body are communicated as separate entities, each with its own aesthetic values and feelings.

The aim of this study was to gain understanding of aesthetic values as a part of HCS food educational practices. By thematically analyzing empirical data from classroom observations, student focus groups, and teacher interviews, we have shown how aesthetic values in HCS food education can be understood in light of three different themes: culinary, production, and bodily aesthetics. The results highlight the significance of aesthetics in the studied practices, and how aesthetic values were part of bringing the practices forward.

Food education involves learning to distinguish and value experiences relating to all the senses: sight, smell, sound, taste, and touch (Fine, 2008). Since these processes entail learning what one finds pleasurable and not, they inherently include aesthetics. However, as Ferguson et al. (2022, p. 19) stress, aesthetics in educational activities “(…) is so tightly interwoven with conceptual moves and learning, it tends to be ‘invisible’ until attention is drawn to it.” In a study of handicraft education, Risberg and Andersson (2022) showed how teachers, in a very hands-on way, taught culturally specific ways of valuing products of wood and metal by sensing (touching) them together with students. The present study adds to this body of research by illustrating how aesthetic values were constituted when teachers in HCS food education emphasized preferred courses of actions for the students to take, and the anticipated outcomes of such actions. An example is seen in the culinary aesthetics section of the results, with teacher 2 talking about how to work a dough. In line with the study by Risberg and Andersson, our results show how HCS food education involves teaching and learning a sensory attentiveness, i.e., which senses and sensory impressions to pay attention to, and how to aesthetically value them.

The results moreover highlight how aesthetic values point towards what counts as valid or desired knowledge within the studied practices and thereby steer events in certain directions. In other words, the results demonstrate how aesthetic values play a role in privileging processes (cf. Wertsch, 1991). Here, the teachers influenced what aesthetic values were constituted, for example by implementing the course section “homemade vs. prefabricated.” This is in line with Todd (2020), who likens the role of a teacher to that of an artist, as they stage aesthetic encounters between students and elements in the environment by choosing contents and designing activities. The teacher thereby becomes a “curator” of aesthetic experiences (Ruitenberg, 2015). In a study of early elementary school science, Caiman and Jakobson (2022) showed how emotional aspects of aesthetic experiences were articulated as judgments which often had ethical undertones. This can be seen in our results as well, in relation to production aesthetics involving animal welfare and environmental concerns, and in relation to bodily aesthetics involving bodily consequences of eating certain foods. If HCS teachers are curators of aesthetic experiences, they should be considered as having the power to influence students’ aesthetic feelings, not least in relation to ethical matters when valuing different aspects of food.

As seen in the results, aesthetic values came into play when the students conformed to (their perceptions of) what the teachers valued. When one student described his experience of a prefabricated soup, he used the exact same term, “horrific,” as the teacher. Another example is the students’ stated effort to keep workspaces clean during cooking in HCS. Throughout, the students seemed to make interpretations of what the teacher valued, consider different actions, and choose to act certain ways. It can be discussed whether the students learned to genuinely value certain things through their participation in HCS food education, or if the students’ valuing actions reflected their willingness to accommodate the teacher in order to, e.g., obtain good grades. Nevertheless, the students’ actions did not always align with what the teachers valued. While the students were seen to emphasize aesthetic values of the meal as an end product, the teachers valued the work process. The process-oriented approach articulated by the teachers is not unexpected, as it reflects the HCS syllabus in force at the time of data generation, where actions such as planning, organizing, and undertaking activities were emphasized over end results such as the finished meal (Skolverket, 2011/2019).

Another example where students’ actions did not reflect the teachers’ values was when the students secretively added extra butter to their food to make it taste better. In this case, gustatory taste triumphed over the teachers’ instructions, i.e., the recipe. The importance of gustatory taste for HCS students’ food choices has been highlighted in earlier qualitative studies [(e.g., Bohm et al., 2016; Gelinder et al., 2020)]. Christensen and Wistoft (2016) and Christensen (2019) have shown how taste can be integrated into food education, to promote students’ engagement and learning outcomes. These studies all highlight the role of teachers in facilitating taste-based learning experiences. Our results support the prominent standing of taste experiences in food education, but also show how aesthetic values in HCS encompass more than gustatory taste, and how these values relate to aspects other than food choices. The results thus contribute to existing HCS research by providing empirical examples of how aesthetic values are a part of the transactions taking place in encounters between participants, artifacts, and context within HCS food education. According to the Swedish syllabus, HCS should provide important tools for students to make conscious food choices as consumers with reference to health, finance, and the environment (Skolverket, 2011/2019). We argue that the recognition of aesthetic values as a part of HCS food education can support the processes of fostering consumer awareness within the subject.

Thematic analysis was chosen with the intention to draw attention to aesthetic values by providing an overview of what values were constituted in situated action within the studied practices, and how. In the results, culinary aesthetics is presented more comprehensively than production and bodily aesthetics. This mirrors the differing extents to which aesthetic values were empirically observed: culinary aesthetic values were notably more common than those relating to production and bodily aesthetics and could therefore be investigated more thoroughly. It should be pointed out, however, that the separation of aesthetic values into three themes is not a direct reflection of the studied practices, but rather an analytical approach to discern, highlight, and make sense of the observed values. This way of thematically structuring the data comes with some challenges and limitations. First, data are taken from the context in which they occurred, and thereby run the risk of being fragmented (Maxwell and Miller, 2010). We have addressed this risk by reporting the results in a narrative fashion, where effort has been made to do the raw data justice. Second, one limitation is that the thematic analysis does not address learning per se. We have shown how certain contents are privileged, and how the participants are seen to act, but cannot say anything about the actual learning or meaning-making occurring within the studied practices. Forthcoming studies could address, e.g., meaning-making in detail, with specific attention to aesthetic values and privileging. Future research might also further explore how video data can be used to enable analysis of the multimodal nature of aesthetic experiences taking place in the classroom.

A limitation of the study is related to its contextuality. The critical case selection resulted in an undiversified group of study participants: experienced teachers and high-achieving students who came from advantaged socio-demographic conditions. In the words of Bourdieu, the participants’ shared tastes may be at least partly explained by their similar social, cultural, and economic capital (cf. Bourdieu, 1987). The results of this study should therefore be considered in light of the context in which the empirical data were generated, and knowledge claims based on the results should not include generalization. However, the purpose of this study was not to make general claims about aesthetic values. The intention was, rather, to describe how aesthetic values came into play in situated action and thereby contribute to informed discussions derived from the particular case. Consequently, the results can offer transferability, i.e., ways to understand other “cases,” where similar situations occur. It is nevertheless important to consider the need of studying aesthetics values in other food educational environments. Future studies should explore how aesthetic values come into play in other contexts than that studied here. For example, this could be done within more diverse groups, where experiences and understandings might not be shared to the same extent.

This study unpacks how the “secret ingredient” of aesthetic values comes into play in HCS food educational practices. Based on the results, we underline that the recognition of aesthetic values as a part of food education can contribute to directing the focus towards immediate, experiential aspects of food and eating. These are aspects which are often obscured in the shadow of an instrumental approach, where food is perceived based on its potential consequences rather than as a part of an aesthetic experience. From a teacher’s perspective, this can mean acknowledging aesthetic aspects while planning, undertaking, and evaluating food education.

The raw data supporting the conclusions in this article are not readily available because no permission was given by the participants for anyone to have the raw data except the principal investigators. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Z2l0YS5iZXJnQGlrdi51dS5zZQ==.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala (ref. no. 2017/230). It was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

GB designed the study reported in this paper with support from YMS and EL. GB conducted the fieldwork which generated the data, reviewed literature, phrased the aim, and drafted the first version of the manuscript. GB and YMS conceptualized the results in three themes. YMS and EL reviewed manuscript content. GB edited the first and reviewed drafts of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The study was performed as a part of the Uppsala Research School in Subject Education (UpRiSE), which is funded by Uppsala University.

The authors would like to thank the teachers and students who generously participated in the study, and Professor Helena Elmståhl for support during the initial stages of the work. We also wish to thank the two reviewers for their constructive criticism and useful suggestions to improve the paper.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ainsworth, S., and Bell, H. (2020). Affective knowledge versus affective pedagogy: the case of native grammar learning. Camb. J. Educ. 50, 597–614. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2020.1751072

Anderhag, P., Wickman, P.-O., and Hamza, K. M. (2015). Signs of taste for science: a methodology for studying the constitution of interest in the science classroom. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 10, 339–368. doi: 10.1007/s11422-014-9641-9

Angrosino, M. (2012). Observation-based research, Research Methods & Methodologies in Education, (Eds.) J. Arthur, M. Waring, R. Coe, and L. V. Hedges, London, UK: Sage Publications, 165–169.

Berg, G., Elmståhl, H., Mattsson Sydner, Y., and Lundqvist, E. (2019). Aesthetic judgments and meaning-making during cooking in home and consumer studies. Educare 2, 30–57. doi: 10.24834/educare.2019.2.3

Biesta, G. J., and Burbules, N. C. (2003). Pragmatism and educational research. Washington, D.C: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Bohm, I. (2022). Cultural sustainability: a hidden curriculum in Swedish home economics? Food Cult. Soc. 26, 742–758. doi: 10.1080/15528014.2022.2062957

Bohm, I., Åbacka, G., Hörnell, A., and Bengs, C. (2023). “Can we add a little sugar?” the contradictory discourses around sweet foods in Swedish home economics. Pedagogy Cult. Soc. 1–17. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2023.2190754

Bohm, I., Lindblom, C., Åbacka, G., and Hörnell, A. (2016). ‘Don’t give us an assignment where we have to use spinach!’: Food choice and discourse in home and consumer studies. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 40, 57–65. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12213

Bourdieu, P. (1987). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Brønnum Carlsen, H. B. (2004). Æstetiske læreprocesser med hensyn til mad og måltider: madens muligheder inden for et æstetisk teorifelt og konsekvenserne heraf for en æstetisk baseret didaktik i arbejdet med mad, levnedsmidler og måltider. [Aesthetic learning processes in connection with food and meals.] Dissertation. Copenhagen, DK: Danmarks Pædagogiske Universitet.

Caiman, C., and Jakobson, B. (2022). Aesthetic experience and imagination in early elementary school science – a growth of ‘science-art-language-game’. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 44, 833–853. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2021.1976435

Christensen, J. (2019). Taste as a constitutive element of meaning in food education. Int. J. Home Econ. 12, 9–19.

Christensen, J., and Wistoft, K. (2016). Taste as a didactic approach: enabling students to achieve learning goals. Int. J. Home Econ. 9, 20–34.

Ferguson, J. P., Tytler, R., and White, P. (2022). The role of aesthetics in the teaching and learning of data modelling. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 44, 753–774. doi: 10.1080/23735082.2020.1750672

Fine, G. A. (2008). Kitchens: the culture of restaurant work. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Freeland, C. (2012). Aesthetics and the senses: introduction. Essays Phil. 13, 399–403. doi: 10.7710/1526-0569.1427

Gelinder, L., Hjälmeskog, K., and Lidar, M. (2020). Sustainable food choices? A study of students’ actions in a home and consumer studies classroom. Environ. Educ. Res. 26, 81–94. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2019.1698714

Höijer, K., Hjälmeskog, K., and Fjellström, C. (2014). The role of food selection in Swedish home economics: the educational visions and cultural meaning. Ecol. Food Nutr. 53, 484–502. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2013.870072

Kauppinen, E., and Palojoki, P. (2023). Striving for a holistic approach: exploring food education through Finnish youth centers. Food Cult. Soc. 1–18, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/15528014.2023.2188661

Korsmeyer, C. (1999). Making sense of taste: Food and philosophy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Korsmeyer, C. (2017). Taste and other senses: reconsidering the foundations of aesthetics. Nordic J. Aesthetics 26, 20–34. doi: 10.7146/nja.v26i54.103078

Krogager, S. G. S., and Leer, J. (2021). Mad og medier: identitet, forbrug og æstetik. [Food and media: identity, consumption and aesthetics]. Frederiksberg, DK: Samfundslitteratur.

Lavelle, F., Spence, M., Hollywood, L., McGowan, L., Surgenor, D., McCloat, A., et al. (2016). Learning cooking skills at different ages: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 13, 119–111. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0446-y

Lichtenstein, A. H., and Ludwig, D. S. (2010). Bring back home economics education. JAMA 303, 1857–1858. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.592

Lidar, M., Almqvist, J., and Östman, L. (2010). A pragmatist approach to meaning making in children’s discussions about gravity and the shape of the earth. Sci. Educ. 94, 689–709. doi: 10.1002/sce.20384

Luff, P., and Heath, C. (2012). Some ‘technical challenges’ of video analysis: social actions, objects, material realities and the problems of perspective. Qual. Res. 12, 255–279. doi: 10.1177/1468794112436655

Magnusson, E., and Marecek, J. (2015). Doing interview-based qualitative research: A learner’s guide. Cambridge MA: Cambridge University Press.

Maxwell, J., and Miller, B. (2010). Categorizing and connecting strategies in qualitative data analysis, Handbook of emergent methods, (Eds.) S. N. Hesse-Biber and P. Leavy, New York, NY: The Guilford Press, 461–477.

Mennell, S., Murcott, A., and Van Otterloo, A. H. (1992). The sociology of food: Eating, diet, and culture. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Pendergast, D. (2008). Introducing the IFHE position statement home economics in the 21st century. Int. J. Home Econ. 1, 3–7.

Prain, V., Ferguson, J. P., and Wickman, P.-O. (2022). Addressing methodological challenges in research on aesthetic dimensions to classroom science inquiry. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 44, 735–752. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2022.2061743

Pryba, R. (2016). Discussing taste: a conversation between Carolyn Korsmeyer and Russell Pryba. J. Somaesthetics 2, 1–2. doi: 10.5278/ojs.jos.v2i1%20and%202.1456

QSR International Pty Ltd . (2015). NVivo (Version 11). Available at: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

Rich, E., and Evans, J. (2015). Where’s the pleasure? Exploring the meanings and experiences of pleasure in school-based food pedagogies, Food Pedagogies, (Eds.) R. Flowers and E. Swan, New York, NY: Routledge, 31–48.

Risberg, J., and Andersson, J. (2022) in “Sensing together: Transaction in handicraft education” in Deweyan transactionalism in education: Beyond self-action and inter-action, (Eds.) J. Garrison, J. Öhman, and L. Östman, London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing, 149–164.

Ruitenberg, C. W. (2015). Toward a curatorial turn in education, Art’s teachings, Teaching’s art: Philosophical, critical and educational musings, (Eds.) T. Lewis and M. Laverty Dordrecht, NL: Springer, 229–242.

Shapiro, L. (2008). Perfection salad: Women and cooking at the turn of the century. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Shusterman, R. (1999). Somaesthetics: a disciplinary proposal. J. Aesthet. Art Critic. 57, 299–314. doi: 10.1111/1540_6245.jaac57.3.0299

Sinclair, N. (2009). Aesthetics as a liberating force in mathematics education? ZDM 41, 45–60. doi: 10.1007/s11858-008-0132-x

Skolverket . (2011/2019). Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet 2011 (Reviderad 2019) [curriculum for compulsory school, preschool classes and after school activities 2011 (revised 2019)]. Stockholm, SE: Skolverket.

Sweeney, K. W. (2012). Hunger is the best sauce, The philosophy of food, (Ed.) D. M. Kaplan , Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 52–68.

Todd, S. (2020). Creating aesthetic encounters of the world, or teaching in the presence of climate sorrow. J. Philos. Educ. 54, 1110–1125. doi: 10.1111/1467-9752.12478

Van Poeck, K., Östman, L., and Öhman, J. (2019). Ethical moves: how teachers can open up a space for articulating moral reactions and deliberating on ethical opinions regarding sustainability issues, Sustainable development teaching, (Eds.) K. PoeckVan, L. Östman, and J. Öhman, New York, NY: Routledge, 153–161.

Wertsch, J. V. (1991). Voices of the mind: Sociocultural approach to mediated action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wickman, P.-O. (2006). Aesthetic experience in science education: Learning and meaning-making as situated talk and action. New York, NY: Routledge.

Wickman, P.-O., Prain, V., and Tytler, R. (2022). Aesthetics, affect, and making meaning in science education: An introduction. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 44, 717–734. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2021.1912434

Williams, D., and Brown, J. (2013). Learning gardens and sustainability education: Bringing life to schools and schools to life. New York, NY: Routledge.

Keywords: food education, aesthetic values, home and consumer studies, aesthetic experience, thematic analysis, culinary aesthetics, production aesthetics, bodily aesthetics

Citation: Berg G, Lundqvist E and Sydner YM (2023) Aesthetic values in home and consumer studies – investigating the secret ingredient in food education. Front. Educ. 8:1240782. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1240782

Received: 15 June 2023; Accepted: 11 September 2023;

Published: 05 October 2023.

Edited by:

Per-Olof Wickman, Stockholm University, SwedenReviewed by:

Joseph Ferguson, Deakin University, AustraliaCopyright © 2023 Berg, Lundqvist and Mattsson Sydner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gita Berg, Z2l0YS5iZXJnQGlrdi51dS5zZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.