- 1School of Social Sciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Social Science and Business, Roskilde University, Roskilde, Denmark

- 3Department of Anthropology, Goldsmiths, University of London, London, United Kingdom

- 4Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, University of Kent, Canterbury, United Kingdom

Despite thousands of higher education institutions (HEIs) having issued Climate Emergency declarations, most academics continue to operate according to ‘business-as-usual’. However, such passivity increases the risk of climate impacts so severe as to threaten the persistence of organized society, and thus HEIs themselves. This paper explores why a maladaptive cognitive-practice gap persists and asks what steps could be taken by members of HEIs to activate the academy. Drawing on insights from climate psychology and sociology, we argue that a process of ‘socially organized denial’ currently exists within universities, leading academics to experience a state of ‘double reality’ that inhibits feelings of accountability and agency, and this is self-reenforcing through the production of ‘pluralistic ignorance.’ We further argue that these processes serve to uphold the cultural hegemony of ‘business-as-usual’ and that this is worsened by the increasing neo-liberalization of modern universities. Escaping these dynamics will require deliberate efforts to break taboos, through frank conversations about what responding to a climate emergency means for universities’ – and individual academics’ – core values and goals.

Introduction

Barely a week goes by without a major new scientific report warning of impending catastrophe from our continued collective failure to address escalating planetary crises. Earth system scientists warn that we now exceed multiple planetary boundaries (Rockström et al., 2023) and that we are already perilously close to tipping points in the climate system (McKay et al., 2022). Current policies will lead to a projected global temperature increase of 3.2°C by the end of the century (IPCC, 2023), yet there is little basis for assuming that organized human society can persist through such rapid changes (Richards et al., 2021; Kemp et al., 2022; Steel et al., 2022). Unless climate change is rapidly and seriously addressed, we face the possibility of a future in which the complex societies that support higher education institutions (HEIs) will be so severely disrupted that scholarship as we know it will no longer be possible (Urai and Kelly, 2023).

Radical interventions are clearly necessary to accelerate a rapid social transformation to avoid the dire outcomes currently forecast (McPhearson et al., 2021; Morrison et al., 2022). Despite this, a hegemonic ‘business-as-usual’ largely prevails in our HEIs (Huckle and Wals, 2015; Fazey et al., 2021), as it does throughout wider society (Stoddard et al., 2021; Nyberg et al., 2022). Even though universities have been the fora where much of the vital knowledge warning us of avoidable disaster - and the massive injustices this entails - has been produced, there is little sign as yet of the transformational changes required in the HE sector (Latter and Capstick, 2021; O’Neill and Sinden, 2021). This holds true even for the thousands of HEIs that have publicly acknowledged the scale and urgency of the crisis through their declarations of climate emergency. In the UK, for example, 59% of universities have failed to meet sector wide carbon emissions reduction targets (Horton, 2022), while no university in the world appears to be currently offering mandatory climate education to all undergraduates (following student-led protests the University of Barcelona looks set to be the first HEI to pilot this from 2024; Burgen, 2022).

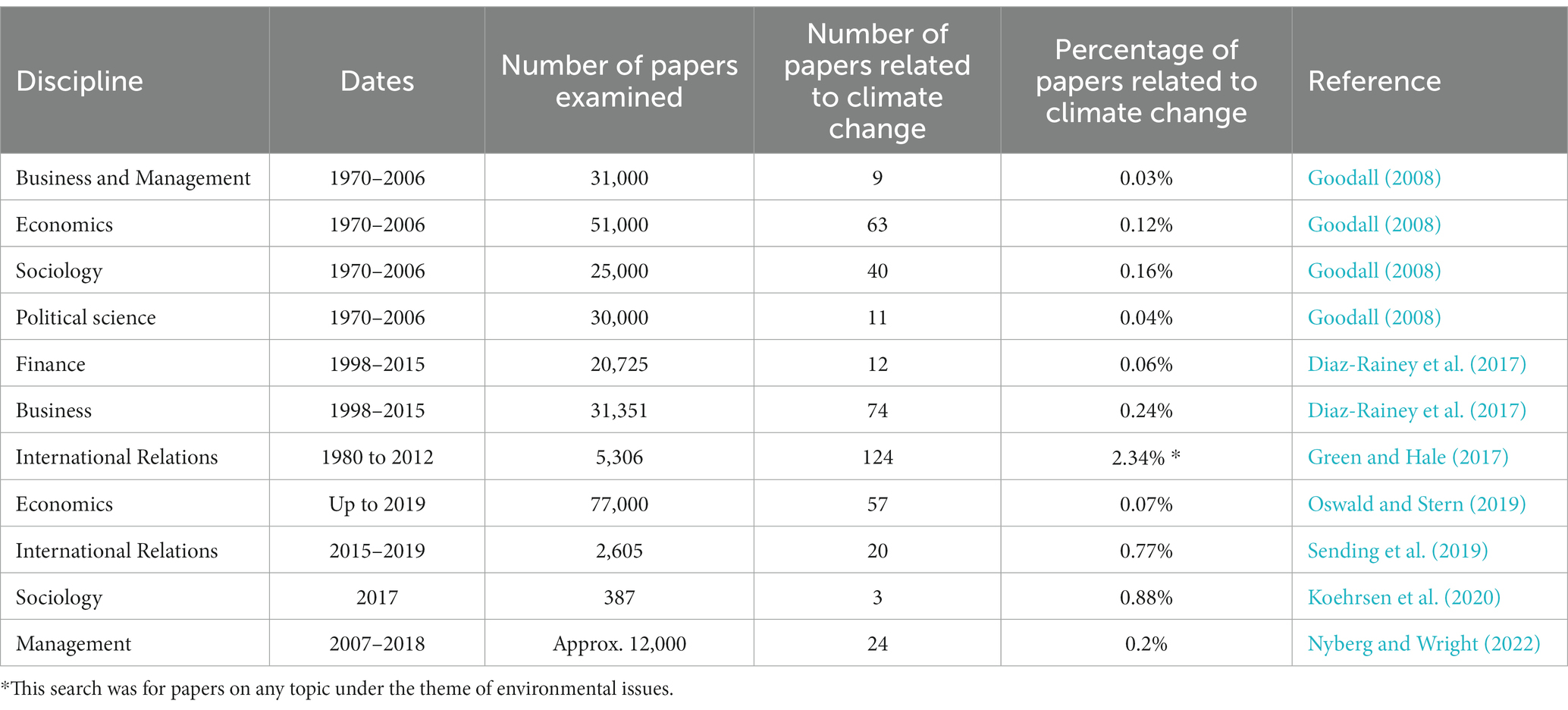

As for teaching, so for research, with scant attention given to the grand challenge of our age in flagship academic journals. For instance, the Quarterly Journal of Economics, a preeminent economics journal, did not publish a single paper on climate change prior to 2019 (Oswald and Stern, 2019; see also: Roos and Hoffart, 2021, p. 22–24). This pattern is repeated across numerous disciplines (Table 1). It’s as though the crisis is somehow deemed unworthy of the academy’s concerted attention; some have referred to this as ‘climate silence’ (Scoville and McCumber, 2023), in the humanities the phenomenon has been dubbed the ‘Great Derangement’ (Ghosh, 2016).

Table 1. Summary of bibliographic searches for papers related to climate change in a variety of academic disciplines.

Nor are universities and academics simply passive by-standers, we are often active agents contributing to the destructive pathway we are currently locked in to. Many universities even continue to conduct research into new fossil fuel exploration and extraction, some of it directly funded by industry, despite the conflicts of interest such funding is known to cause (Franta and Supran, 2017; Corderoy, 2021; Almond et al., 2022). At worst our elite HEIs become the means through which cultural elites can cement hegemonic ideas and legitimize the continuation of business-as-usual (Nyberg and Wright, 2022; Kinol et al., 2023). Thus, McGeown and Barry (2023) point out; “as producers and gatekeepers of knowledge, and as providers of education and training, our universities play a key role in the reproduction of unsustainability,” it follows that HEIs can currently be understood to be perpetuating climate injustice (Kinol et al., 2023).

This dissonance extends to the individual behavior of many academics. For example, the normalization of aviation-based hyper-mobility in academic work (Bjørkdahl and Franco Duharte, 2022). It is even the case that professors in climate science fly more than other researchers, despite the tremendous carbon emissions associated with such activities (Whitmarsh et al., 2020). On a day-to-day basis, most academic staff seem to be maintaining the semblance of normalcy and unconcern. So great is our apparent collective indifference that an onlooker could be forgiven for thinking that we do not believe our own institutions’ official warnings that an emergency is unfolding around us.

This “collective equanimity in the face of the unprecedented risk” (Hoggett, 2019, p. 8) forces us to confront a profound question as academics – given that planetary change threatens the socio-ecological conditions on which our institutions depend, why does this ‘cognitive-practice gap’ persist (O’Neill and Sinden, 2021)? And why aren’t many more of us engaging directly with the effort to push for transformative change within our institutions and across broader society?

Academics are a particularly important group of which to ask this question, given that our skills in critical analysis of information (and often our specialist knowledge) could be expected to give us particular appreciation of the extent of the emergency and effective pathways for addressing the crisis (Racimo et al., 2022; Urai and Kelly, 2023). Our standing in society makes us potentially powerful agents and catalysts of broader societal change (Gardner et al., 2021); conversely, if those with privileged knowledge about the crisis carry on as usual it adds an insincerity to our warnings and communicates a lack of grounds for genuine concern (Attari et al., 2016), how then can we expect others to act?

Here, we suggest that both academic institutions and academics as individuals largely exist in a state of ‘double reality,’ in which we are able to intellectually recognize the existence of the crisis without feeling a compulsion to act on it. We argue that such a response is maladaptive because passivity in the face of the planetary emergency hastens the breakdown of the social-ecological conditions that have allowed academia to thrive. In short, unless we additionally engage in efforts to avoid climate breakdown, we are training students for a future that will not come to pass and devoting our lives to research of limited future relevance or utility under what are projected to be drastically altered circumstances. Currently, we are striving to achieve professional success, but not our collective survival.

In this Perspective essay, we suggest that this ‘double reality’ may arise through a range of psycho-social phenomena, that are exacerbated by institutional inertia and the neo-liberalization of the higher education sector which constrain the possibilities for academic engagement in the crisis and in the quest for climate justice. We conclude by reflecting on the need to break cultural taboos though frank discussions in academic institutions about what it is we truly value, what it will take to build genuinely sustainable universities, and what this means for how we each view our professional priorities in these times.

The double reality of living in denial

Different psycho-social mechanisms have been proposed to explain the continued passivity of individuals despite our knowledge of the need for rapid change. For example, ‘Gidden’s Paradox’ suggests that, “since no previous generation has ever had to confront the problem of human-induced climate change before, it is hard for the public to accept it as a reality, let alone an urgent problem, when stacked up against the diversity of other problems the world has.” (Giddens, 2015, p. 158).

Alternatively, many climate psychologists argue that our lack of action stems not from a sense of apathy and lack of immediate concern, but from a surfeit of concern leading to the unconscious deployment of psychological defense mechanisms that involve mental states negating reality (Lertzman, 2013; Long, 2015). This can present as outright science denial, but more commonly it manifests as more subtle states of disavowal where “reality is more accepted, but its significance is minimized” (Weintrobe, 2013, p. 6). In an effort to continue as we are, we might try to deliberately put our concerns out of mind, or distance ourselves by saying it will be a problem for the far-future or comfort ourselves through magical thinking such as hopes of a techno-fix. A particular form of avoidance manifests as ‘implicatory disavowal,’ whereby individuals do not feel a moral responsibility to act despite being aware of the issue, allowing us to turn a blind eye, such that we do not feel accountable for our actions. Thus, individuals reject the need to address the climate crisis to avoid experiencing traumatic feelings such as anxiety, distress, and helplessness (Hoggett, 2013; Weintrobe, 2021).

Such passivity can spread between individuals, because perceiving an apparent lack of concern amongst our peers can lead to self-silencing and the emergence of a state of pluralistic ignorance (Geiger and Swim, 2016; Kjeldahl and Hendricks, 2018). Indeed, research into socially organized denial reveals how adept people are at managing emotional states by directing attention to other subjects and deliberately ignoring ‘taboo’ topics, creating social silences that prevent us from raising climate change as a subject of conversation and political concern (Norgaard, 2011, see also; Nyberg and Wright, 2022). This is reinforced through attacks by special interest lobby groups who specifically target outspoken academics to make an example of them and intimidate others into silence (Mann, 2015; Jacquet, 2022). Social interactions are constructed in such a way that individuals come to inhabit a ‘double reality,’ a state of simultaneous knowing and not knowing, which allows us to go about our daily routines and fulfill our social roles, whilst managing situations around us to allow us to continue ignoring uncomfortable truths (Cohen, 2001; Zerubavel, 2006). In such situations, practices, norms, conventions and boundaries develop that serve to limit the scope for social change and maintain the status quo (Gramsci, 1971). For example, the emergence of ‘groupthink’ whereby individuals suppress disconfirming information for fear of being ostracized, ridiculed, punished or professionally harming oneself, and career prospects (Cohen, 2001, p. 66).

As a group whose status is privileged in the current system, academics might be especially prone to adopting these defense mechanisms to deflect the associated cognitive dissonance (Sullivan, 2021). However, there is increasing evidence that continuing with normal activities can lead many environmental researchers to suffer, either directly or vicariously, from traumatic stress in response to the subject matter of their work (Clayton, 2018; Pihkala, 2020).

Head and Harada (2017) suggest that emotional detachment is common among environmental scientists and that researchers may adopt coping strategies which bias the research questions we seek to answer or, how we communicate the findings. Hoggett and Randall (2018) further identify a variety of institutional defenses practiced within scientific culture that act as coping mechanisms, these include norms such as “ideas of scientific progress, scientific detachment, rationality and specialization, scientific excitement and normalization of overwork” (p. 252). However, these are not without consequence, as psychoanalyst Sally Gillespie observes “the notion of attempting to separate objective understanding from subjective understating is deeply problematic, as it can morph into a form of splitting or distancing that separates thinking from feeling” and that when such psychic-numbing happens it can “[hinder our] ability to respond fully or effectively” (Gillespie, 2020).

The university: institutional inertia, neoliberalism and cultural trauma

It is also important, however, to consider the ways our psychological responses to climate change are shaped by their contingent social-structural context (Schmitt et al., 2020) and the broader mechanisms responsible for institutional inertia (Boston and Lempp, 2011; Munckaf Rosenschöld et al., 2014). Universities are complex hierarchical organizations with many distinct constituencies and complicated bureaucracies that have traditionally operated on timescales not well suited to the urgency of the climate crisis (Gardner et al., 2021; Green, 2021). Furthermore, the psycho-social factors we have described above have been exacerbated by a contemporaneous shift towards an increasingly neoliberal political economy in the higher education system in many countries.

Since the 1980s, universities have been subject to a number of radical changes rooted in neoliberal ideology: a shift from public to private funding in the form of donations, investments and especially tuition fees, making students customers that need to be served (Brown, 2015); overall financialization both through investments in stockmarkets and borrowing, with some universities now effectively run by accounting firms (Freedman, 2021); the corporatization of university management, all run now by a cadre of people themselves firmly committed to neoliberal ideology and corporate values and practices (Morley, 2023); the prioritization of spending on flashy infrastructure projects over salaries, on STEM subjects over arts, humanities and social sciences (Troiani and Dutson, 2021); universities being seen as employability factories and career investments rather than sites for genuine learning or creative and critical thinking; infused with a spirit of competition and efficiency permeating everything. All this means that universities have not only become highly precarious, stressful workplaces for academic staff, they are also themselves in danger of being little more than “cogs in a market-driven machine designed to perpetuate economic and political injustice” (Sen, 2023).

Urai and Kelly (2023) highlight that the climate crisis is unfolding just as our universities’ ability to respond have been weakened through bureaucratisation, inordinate competition and restrictions to academic freedom. Likewise, McCowan et al. (2021) note “competition for resources and students can also act against public good activities, including sustainability and climate change.” In consequence, academic staff face a lack of time and emotional support, intense hyper-competition and continuous economic precarity (Fochler et al., 2016; Lempiäinen, 2016; Pells, 2019; Albayrak-Aydemir and Gleibs, 2023). This environment denies us the time, energy and emotional resources necessary for reconfiguring curricula, redirecting research, engaging in civic discourse or other duties as an engaged member of academic community, all while universities fail to incentivize or adequately reward such initiatives. Many individuals in the ‘hopeless university’ experience a profound sense of alienation from their work, both academically/intellectually, as well as with regard to the social relations in which they are embedded (Hall, 2021). In short, the neo-liberalization of higher education, as elsewhere, has created a culture of uncare (Weintrobe, 2021).

Brulle and Norgaard (2019) combine the insights of psycho-social processes and institutional intransigence we discuss above, concluding that a more complete explanation for the social inertia is the “avoidance of cultural trauma.” We are witnessing, they suggest, the consequences of an organized information environment focused on the defense of the existing hegemonic culture and the preservation of an ideological framework favorable to the status quo (Brulle and Norgaard, 2019; c.f. Nyberg et al., 2022). When understood from this perspective, “climate change constitutes a profound challenge to established ways of life in Western nations and constitutes the emergence of an ongoing and expanding cultural trauma.” Ways of life ultimately deeply rooted in coloniality and notions of western dominance (Brand and Wissen, 2021; Sultana, 2022; McLaren and Corry, 2023).

Applying this lens, we can recognize that the organizational structures and incentives of modern universities are adapted to reproduce and uphold an extractivist growth economy, and this results in an inbuilt inertia against change, manifest in large part through the legitimating power of hegemonic cultural practices and conventions supporting the common sense of business-as-usual within the organization. This makes it hard for individuals within the organization to challenge the status quo: in other words, “when you expose a problem you pose a problem… [and the] problem would go away if you would just stop talking about it or if you went away” (Ahmed, 2017). To avoid such confrontations and the psychological need to deny the implications of our inaction, we see the emergence of a ‘taboo’ and a climate of silence on issues relating to pathways for genuine sustainability. We also see displacement onto the fetishizing of non-transformatory solutions, such as individual responsibility for sustainability (Maniates, 2001; Lamb et al., 2020); the use of empty marketing discourses centered on a narrative of rhetorical ‘boosterism’ (O’Neill and Sinden, 2021); or the reframing of the emergency in terms of corporate risk-management (Wright and Nyberg, 2017).

Collapsing the ‘double reality’ through living in climate truth

It has been recently suggested that universities, as they currently exist, are not fit for purpose in a time of planetary emergency (Green, 2021; Maxwell, 2021; McGeown and Barry, 2023), and there is a desperate need to develop alternative approaches. This is not to belittle or deny that there are a growing number of individual as well as institutional attempts underway to center the climate emergency in higher education in both teaching and research. New courses on sustainability themes are being created and climate issues discussed in more and more modules. Often in response to growing pressure from students organizing in disciplines as diverse as law and medicine, to demand an education fit for these times (MS4SF, 2022; Hirschel-Burns et al., 2023). Ecology and climate are also increasingly mentioned in research strategies and funding calls. But these are still isolated rather than sector wide initiatives (with some notable exceptions, e.g., the Faculty for a Future, 2023), and often end up becoming part of institutional green-washing which bolsters rather than dismantles business-as-usual. There is also no end in sight for overwork, precarity and marketisation. We are still a long way off the genuine, complete transformation of academia we need.

Aligning HEIs with a path towards climate justice will require provision for the personal growth and transformation of academic staff, including supporting us to process our own eco-anxiety (Pihkala, 2020) and redefining the meaning of scholarly integrity for the Anthropocene (Raffoul et al., 2021; Sutoris, 2022). In this context, it is crucial to be attentive to the existing power relations in academia - the ‘double reality’ we point to is most pronounced in academics with the greatest privilege; those in permanent employment and in positions of institutional power. We cannot leave early career researchers, scholars in precarious positions and students to be the primary drivers for the change we so urgently need in our institutions. More fundamentally still, we need to rethink the power relations in which HEI and knowledge production take place, at a global scale characterized by profoundly unequal impact of the climate and ecological crisis. Tackling the persistence of Eurocentric perspectives and acknowledging climate (in)justice in teaching and research, as Sultana insists (Sultana, 2022, p. 8), requires that we ‘address knowledge production and epistemic underpinnings of climate coloniality.’ Even in academic climate activism, these power relations remain acute (Artico et al., 2023).

This will require setting out a new vision for what HEIs can be in this time, and an experimental approach toward establishing these alternatives (e.g., Lotz-Sisitka et al., 2015; Facer, 2020; Moser and Fazey, 2021; Kelly et al., 2022; Kinol et al., 2023; Urai and Kelly, 2023). Undoubtedly, this will necessarily involve collective organizing within and across our own institutions to effectively challenge dominant paradigms (Gardner et al., 2021; Racimo et al., 2022). None of this will be easy or comfortable – though we can have hope that it will be fulfilling.

In our view, a key initial step in facilitating such a transformation is to break the climate of silence on campus by making an active effort to push through the taboo and hold conversations with our colleagues about our concerns. Thinking with Ahmed (2023), we have to take on a ‘climate killjoy’ commitment: ‘if questioning an existing arrangement makes people unhappy, we are willing to make people unhappy’ (2023, p. 19). This would involve bringing up the topic as often as is possible in university committees or union branch meetings, in the classroom or even on grant review panels, learned associations and other research fora. We must also actively seek opportunities to speak about our collective response to the climate crisis in non-academic spaces through public outreach and engagement activities with citizens, businesses, policymakers, politicians, and through the media and cultural events. This allows concerned communities to form, discuss solutions, and begin to collectively organize for change. Through such efforts we can expect to burst the bubble of ‘pluralistic ignorance’, potentially precipitating a social-tipping point on campus and sparking a process of social contagion that could spread from institution to institution throughout the sector (Moser and Dilling, 2007; Otto et al., 2020; Winkelmann et al., 2022).

By deliberately striving to collapse our ‘double reality’ through aligning our words and our actions into something more congruous, we argue that we can end the paralyzing and distressing effects of cognitive dissonance and begin to effectively challenge the hegemonic culture protecting the status-quo. ‘Living in climate truth’ in this way can have liberatory consequences (Salamon, 2020): it frees us academics to lead by example and fulfil the Socratic virtue of parrhesia to which we are tasked – speaking truth for the public good; and where necessary upholding our duty to speak truth to power.

Conclusion

For too long we have allowed a culture of climate silence to dominate in our universities, leading to a misalignment of our priorities from our core purpose and values, thereby perpetuating a maladaptive response to the unfolding planetary emergency and undermining the very future of the higher education sector. Universities have in effect become ‘fraud bubbles’ (Weintrobe, 2021) in which staff and students must construct a ‘double reality’, in order to pursue a narrow social role, trapped in maladaptive incentive structures of increasingly neoliberal institutions. This ultimately serves to reproduce the hegemonic practices, norms and conventions driving socio-ecological collapse. As an academic community we must urgently learn to grapple with the role that universities can play as leaders in the necessary social transformation to come. Our dearest notions of progress, rooted in our desire for the beneficial accumulation and application of knowledge (Collini, 2012), are now both directly and indirectly threatened by the climate crisis.

We can no longer avoid the realization that as a sector we must engage directly with the existential questions about our collective purpose which are posed by the growing existential threat of unraveling socio-ecological systems (McGeown and Barry, 2023; Urai and Kelly, 2023). As individual academics and HEIs tasked with developing, holding, and passing on knowledge, we must ask ourselves how we ought to respond so as to preserve our core goals and values?

If we allow ourselves and our institutions to fully internalize such a threat, we are forced to accept that, unless urgent action is taken, we risk such disruption to the material circumstances necessary for the social conditions under which research and learning can flourish, that the research to which we currently devote our lives will be lost. In such circumstances our priorities and ambitions, both professional and personal, are forced to shift. Increasingly academics from all disciplines are recognizing that we must, therefore, devote a substantial fraction of our collective efforts as institutions to preserving such conditions (Gardner et al., 2021; Racimo et al., 2022). All academics, no matter their discipline, have a role in this, for there is no research on a dead planet.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AT, LH, PV, and CG contributed to the concepts presented in this manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jay Chard, Samuel Finnerty, Sally Weintrobe, Steve Westlake, Tristram Wyatt and Kylie Yarlett, and the reviewer for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albayrak-Aydemir, N., and Gleibs, I. H. (2023). A social-psychological examination of academic precarity as an organizational practice and subjective experience. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 62, 95–110. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12607

Almond, D., Du, X., and Papp, A. (2022). Favourability towards natural gas relates to funding source of university energy centres. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 1122–1128. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01521-3

Artico, D., Durham, S., Horn, L., Mezzenzana, F., Morrison, M., and Norberg, A. (2023). “Beyond being analysts of doom”: scientists on the frontlines of climate action Frontiers in sustainability sec. Sustain Organ 4, 1–6. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2023.1155897

Attari, S. Z., Krantz, D. H., and Weber, E. U. (2016). Statements about climate researchers’ carbon footprints affect their credibility and the impact of their advice. Clim. Chang. 138, 325–338. doi: 10.1007/s10584-016-1713-2

Bjørkdahl, K., and Franco Duharte, A. S. (2022). Academic flying and the means of communication. Singapore: Palgrave McMillan.

Boston, J., and Lempp, F. (2011). Climate change: explaining and solving the mismatch between scientific urgency and political inertia. Account. Audit. Account. J. 24, 1000–1021. doi: 10.1108/09513571111184733

Brand, U., and Wissen, M. (2021) The imperial mode of living: everyday life and the ecological crisis of capitalism. Verso: London.

Brown, R. (2015). The marketisation of higher education. Issues and ironies. Available at: Issue- https://repository.uwl.ac.uk/id/eprint/3065/1/The%20marketisation%20of%20Higher%20education.pdf

Brulle, R. J., and Norgaard, K. M. (2019). Avoiding cultural trauma: climate change and social inertia. Environ. Polit. 28, 886–908. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2018.1562138

Burgen, S. (2022) Barcelona students to take mandatory climate crisis module from 2024. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/12/barcelona-students-to-take-mandatory-climate-crisis-module-from-2024

Clayton, S. (2018). Mental health risk and resilience among climate scientists. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 260–261. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0123-z

Corderoy, J. (2021) British universities slammed for taking £90m from oil companies in four years. Available at: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/dark-money-investigations/british-universities-slammed-for-taking-90m-from-oil-companies-in-four-years (Accessed May 22, 2023)

Diaz-Rainey, I., Robertson, B., and Wilson, C. (2017). Stranded research? Leading finance journals are silent on climate change. Clim. Chang. 143, 243–260.

Facer, K. (2020). Beyond business as usual: Higher education in the era of climate change. Oxford: Higher Education Policy Institute.

Faculty for a Future (2023). Available at: https://facultyforafuture.org/about-us (Accessed August 4, 2023).

Fazey, I., Hughes, C., Schäpke, N. A., Leicester, G., Eyre, L., Goldstein, B. E., et al. (2021). Renewing universities in our climate emergency: stewarding system change and transformation. Front. Sustain. 2:677904. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.677904

Fochler, M., Felt, U., and Müller, R. (2016). Unsustainable growth, hypercompetition, and worth in life science research: narrowing evaluative repertoires in doctoral and postdoctoral scientists’ work and lives. Minerva 54, 175–200. doi: 10.1007/s11024-016-9292-y

Franta, B., and Supran, G. (2017) The fossil fuel industry's invisible colonization of academia. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2017/mar/13/the-fossil-fuel-industrys-invisible-colonization-of-academia (Accessed May 22, 2023)

Freedman, D. (2021) Goldsmiths strike: Why we’re fighting the marketisation of higher education. Available at: https://braveneweurope.com/des-freedman-goldsmiths-strike-why-were-fighting-the-marketisation-of-higher-education

Gardner, C. J., Thierry, A., Rowlandson, W., and Steinberger, J. K. (2021). From publications to public actions: the role of universities in facilitating academic advocacy and activism in the climate and ecological emergency. Front. Sustain. 2:679019. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.679019

Geiger, N., and Swim, J. K. (2016). Climate of silence: pluralistic ignorance as a barrier to climate change discussion. J. Environ. Psychol. 47, 79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.05.002

Ghosh, A. (2016) The great derangement: Climate change and the unthinkable. University of Chicago Press: Chicago

Giddens, A. (2015). The politics of climate change. Policy Polit. 43, 155–162. doi: 10.1332/030557315X14290856538163

Gillespie, S. (2020) Climate crisis and consciousness: Reimagining our world and ourselves. Routledge: Abingdon

Goodall, A. H. (2008). Why have the leading journals in management (and other social sciences) failed to respond to climate change? J. Manag. Inq. 17, 408–420. doi: 10.1177/1056492607311930

Gramsci, A. (1971) Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci, New York, NY, International Publishers.

Green, A. J. K. (2021). Challenging conventions—a perspective from within and without. Front. Sustain. 2:662038. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.662038

Green, J., and Hale, T. (2017). Reversing the marginalization of global environmental politics in international relations: an opportunity for the discipline. Polit. Sci. Polit. 50, 473–479. doi: 10.1017/S1049096516003024

Hall, R. (2021). The hopeless university: Intellectual work at the end of the end of history. London, UK: Mayfly Books.

Head, L., and Harada, T. (2017). Keeping the heart a long way from the brain: the emotional labour of climate scientists. Emot. Space Soc. 24, 34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2017.07.005

Hirschel-Burns, T., Kay, M., Nogueira, I., Smith, J., and Waldman, N. (2023) Fueling the climate crisis: Measuring T-20 law school participation in the fossil fuel lawyer pipeline. Available at: https://www.ls4ca.org/fossil-lawyers-report (Accessed May 22, 2023).

Hoggett, P. (2013). “Climate change in a perverse culture” in Engaging with climate change: Psychoanalytic and interdisciplinary perspective. ed. S. Weintrobe (Hove, UK: Routledge).

Hoggett, P. (2019) Climate psychology: On indifference to disaster. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan

Hoggett, P., and Randall, R. (2018). Engaging with climate change: comparing the cultures of science and activism. Environ. Values 27, 223–243. doi: 10.3197/096327118X15217309300813

Horton, H. (2022) Most UK universities failing to hit carbon reduction targets. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2022/dec/06/uk-universities-failing-carbon-reduction-targets-emissions-fossil-fuel-divestment (Accessed May 22, 2023)

Huckle, J., and Wals, A. E. J. (2015). The UN decade of education for sustainable development: business as usual in the end. Environ. Educ. Res. 21, 491–505. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2015.1011084

IPCC (2023). “Summary for policymakers” in Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. A report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. eds. C. W. Team, H. Lee, and J. Romero (Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC), 36.

Jacquet, J. (2022). The playbook: How to deny science, sell lies, and make a killing in the corporate world. London, UK: Allen Lane.

Kelly, O., Illingworth, S., Butera, F., Dawson, V., White, P., Blaise, M., et al. (2022). Education in a warming world: trends, opportunities and pitfalls for institutes of higher education. Front. Sustain. 3:920375. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2022.920375

Kemp, L., Xu, C., Depledge, J., Ebi, K. L., Gibbins, G., Kohler, T. A., et al. (2022). Climate endgame: exploring catastrophic climate change scenarios. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119:e2108146119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2108146119

Kinol, A., Miller, E., Axtell, H., Hirschfeld, I., Leggett, S., Si, Y., et al. (2023). Climate justice in higher education: a proposed paradigm shift towards a transformative role for colleges and universities. Clim. Chang. 176:15. doi: 10.1007/s10584-023-03486-4

Kjeldahl, E. M., and Hendricks, V. F. (2018). The sense of social influence: pluralistic ignorance in climate change. EMBO Rep. 19:e47185. doi: 10.15252/embr.201847185

Koehrsen, J., Dickel, S., Pfister, T., Rödder, S., Böschen, S., Wendt, B., et al. (2020). Climate change in sociology: still silent or resonating? Curr. Sociol. 68, 738–760. doi: 10.1177/0011392120902223

Lamb, W. F., Mattioli, G., Levi, S., Roberts, J. T., Capstick, S., Creutzig, F., et al. (2020). Discourses of climate delay. Glob. Sustain. 3:e17. doi: 10.1017/sus.2020.13

Latter, B., and Capstick, S. (2021). Climate emergency: UK universities’ declarations and their role in responding to climate change. Front. Sustain. 2:660596. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.660596

Lempiäinen, K. (2016). “Precariousness in academia: prospects for university employment” in The new social division. eds. D. della Porta, S. Hänninen, M. Siisiäinen, and T. Silvasti (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 123–138.

Lertzman, R. A. (2013). “The myth of apathy” in Engaging with climate change: Psychoanalytic and interdisciplinary perspective. ed. S. Weintrobe (Hove: Routledge)

Lotz-Sisitka, H., Wals, A. E. J., Kronlid, D., and McGarry, D. (2015). Transformative, transgressive social learning: rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 16, 73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2015.07.018

Maniates, M. F. (2001). Individualization: plant a tree, buy a bike, save the world? Glob. Environ. Polit. 1, 31–52. doi: 10.1162/152638001316881395

Mann, M. E. (2015). The Serengeti strategy: how special interests try to intimidate scientists, and how best to fight back. Bull. At. Sci. 71, 33–45. doi: 10.1177/0096340214563674

Maxwell, N. (2021). How universities have betrayed reason and humanity—and what’s to be done about it. Front. Sustain. 2:631631. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.631631

McCowan, T., Leal Filho, W., and Brandli, L. (2021). Universities facing climate change and sustainability. Körbur-Stftung Hamburg: Hamburg.

McGeown, C., and Barry, J. (2023). Agents of (un)sustainability: democratising universities for the planetary crisis. Front. Sustain. 4:1166642. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2023.1166642

McKay, D. I. A., Staal, A., Abrams, J. F., Winkelmann, R., Sakschewski, B., Loriani, S., et al. (2022). Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science 377, 1–10. doi: 10.1126/science.abn7950

McLaren, D., and Corry, O. (2023). “Our Way of Life is not up for Negotiation!”: Climate Interventions in the Shadow of ‘Societal Security’. Global Studies Quarterly 3, 1–14. doi: 10.1093/isagsq/ksad037

McPhearson, T. M., Raymond, C., Gulsrud, N., Albert, C., Coles, N., Fagerholm, N., et al. (2021). Radical changes are needed for transformations to a good Anthropocene. NPJ Urban Sustain 1:5. doi: 10.1038/s42949-021-00017-x

Morley, C. (2023). The systemic neoliberal colonisation of higher education: a critical analysis of the obliteration of academic practice. Aust. Educ. Res. 1, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s13384-023-00613-z

Morrison, T. H., Adger, W. N., Agrawal, A., Brown, K., Hornsey, M. J., Hughes, T. P., et al. (2022). Radical interventions for climate-impacted systems. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 1100–1106. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01542-y

Moser, S. C., and Dilling, L. (2007). “Toward the social tipping point: creating a climate for change” in Creating a climate for change: Communicating climate change and facilitating social change. ed. L. Dilling (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 491–516.

Moser, S. C., and Fazey, I. (2021). If it is life we want: a prayer for the future (of the) university. Front. Sustain. 2:662657. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.662657

MS4SF (2022) Guide to climate and health curriculum reform in medical schools. Medical Students for a Sustainable Future. Available at: (https://ms4sf.org/climate-and-health-curriculum-reform-guide/)

Munckaf Rosenschöld, J., Rozema, J. G., and Frye-Levine, L. A. (2014). Institutional inertia and climate change: a review of the new institutionalist literature. WIREs Clim Change 5, 639–648. doi: 10.1002/wcc.292

Nyberg, D., and Wright, C. (2022). Climate-proofing management research. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 36, 713–728. doi: 10.5465/amp.2018.0183

Nyberg, D., and Wright, C.Bowden, V. (2022) Organising responses to climate change. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK

O’Neill, K., and Sinden, C. (2021). Universities, sustainability, and neoliberalism: contradictions of the climate emergency declarations. Polit. Govern. 9, 29–40. doi: 10.17645/pag.v9i2.3872

Oswald, A., and Stern, N. (2019). Why does the economics of climate change matter so much—and why has the engagement of economists been so weak? R. Econ. Soc. Available at: https://www.andrewoswald.com/docs/ClimatechangeOswaldSternSept2019forRES.pdf

Otto, I. M., Donges, J. F., Cremades, R., Bhowmik, A., Hewitt, R. J., Lucht, W., et al. (2020). Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth’s climate by 2050. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 2354–2365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1900577117

Pells, R. (2019). Hypercompetition reshapes research and academic publishing. Times Higher Education. Available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/hypercompetition-reshapes-research-and-academic-publishing (Accessed May 22, 2023).

Pihkala, P. (2020). The cost of bearing witness to the environmental crisis: vicarious traumatization and dealing with secondary traumatic stress among environmental researchers. Soc. Epistemol. 34, 86–100. doi: 10.1080/02691728.2019.1681560

Racimo, F., Valentini, E., Rijo De León, G., Santos, T. L., Norberg, A., Atmore, L. M., et al. (2022). Point of view: the biospheric emergency calls for scientists to change tactics. eLife 11, 1–15. doi: 10.7554/eLife.83292

Raffoul, W. A., Fopp, D., Elfversson, E., Avery, H., and Carolan, R. (2021) The climate crisis gives science a new role. Here’s how research ethics must change too. The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/the-climate-crisis-gives-science-a-new-role-heres-how-research-ethics-must-change-too-171201 (Accessed May 22, 2023).

Richards, C. E., Lupton, R. C., and Allwood, J. M. (2021). Re-framing the threat of global warming: an empirical causal loop diagram of climate change, food insecurity and societal collapse. Clim. Chang. 164:49. doi: 10.1007/s10584-021-02957-w

Rockström, J., Gupta, J., Qin, D., Lade, S. J., Abrams, J. F., Andersen, L. S., et al. (2023). Safe and just earth system boundaries. Nature 619, 102–111. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06083-8

Roos, M., and Hoffart, F. (2021). Climate Economics: A Call for More Pluralism And Responsibility. (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan), 22–24.

Salamon, M. K. (2020). Facing the climate emergency: How to transform yourself with climate truth, Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Schmitt, M. T., Neufeld, S. D., Mackay, C. M. L., and Dys-Steenbergen, O. (2020). The perils of explaining climate inaction in terms of psychological barriers. J. Soc. Issues 76, 123–135. doi: 10.1111/josi.12360

Scoville, C., and McCumber, A. (2023). Climate silence in sociology? How elite American sociology, environmental sociology, and science and technology studies treat climate change. Sociol. Perspect. 1–26. doi: 10.1177/07311214231180554

Sen, S. (2023). Battleground University. Neoliberalism is Silencing University. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/3/3/battleground-university-neoliberalism-is-silencing-education

Sending, O. J., Øverland, I., and Hornburg, T. B. (2019). Climate change and international relations: a five-pronged research agenda. J. Int. Aff. 73, 183–194.

Steel, D., DesRochesb, C. T., and Mintz-Woo, K. (2022). Climate change and the threat to civilization. PNAS 119:e2210525119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2210525119

Stoddard, I., Anderson, K., Capstick, S., Carton, W., Depledge, J., Facer, K., et al. (2021). Three decades of climate mitigation: why haven't we bent the global emissions curve?'. Ann. Rev. Environ. Resour. 46, 653–689. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-011104

Sullivan, S. (2021). “I’m Sian, and I’m a fossil fuel addict: on paradox, disavowal and (Im)possibility in changing climate change” in Negotiating climate change in crisis. eds. S. Böhm and S. Sullivan (Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers)

Sultana, F. (2022). The unbearable heaviness of climate coloniality. Polit. Geogr. 99:102638. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102638

Sutoris, P. (2022) Educating for the Anthropocene: Schooling and activism in the face of slow violence. MIT Press. Cambridge, USA

Troiani, I., and Dutson, C. (2021). The neoliberal university as a space to learn/think/work in higher education. Archit. Cult. 9, 5–23. doi: 10.1080/20507828.2021.1898836

Urai, A. E., and Kelly, C. (2023). Rethinking academia in a time of climate crisis. eLife 12:e84991. doi: 10.7554/eLife.84991

Weintrobe, S. (2013) Engaging with climate change: Psychoanalytic and interdisciplinary perspective, Routledge: Hove

Weintrobe, S. (2021) Psychological roots of the climate crisis: Neoliberal exceptionalism and the culture of uncare, Bloomsbury: London

Whitmarsh, L., Capstick, S., Moore, I., Kohler, J., and Le Quere, C. (2020). Use of aviation by climate change researchers: structural influences, personal attitudes, and information provision. Glob. Environ. Change 65:102184. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102184

Winkelmann, R., Donges, J. F., Keith Smith, E., Milkoreit, M., Eder, C., Heitzig, J., et al. (2022). Social tipping processes towards climate action: a conceptual framework. Ecol. Econ. 192:107242. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107242

Wright, C., and Nyberg, D. (2017). An inconvenient truth: how organizations translate climate change into business as usual. Acad. Manag. J. 60, 1633–1661. doi: 10.5465/amj.2015.0718

Keywords: climate change, disavowal, higher education, institutional inertia, neoliberal university, socially organized denial, sustainability

Citation: Thierry A, Horn L, von Hellermann P and Gardner CJ (2023) “No research on a dead planet”: preserving the socio-ecological conditions for academia. Front. Educ. 8:1237076. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1237076

Edited by:

Alison Julia Katherine Green, Scientists Warning Foundation, United StatesReviewed by:

John Barry, Queen's University Belfast, United KingdomCopyright © 2023 Thierry, Horn, von Hellermann and Gardner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aaron Thierry, dGhpZXJyeWF0QGNhcmRpZmYuYWMudWs=

Aaron Thierry

Aaron Thierry Laura Horn

Laura Horn Pauline von Hellermann

Pauline von Hellermann Charlie J. Gardner

Charlie J. Gardner