- 1Institute of Educational Science, University of Bamberg, Bamberg, Germany

- 2Institute of Educational Sciences, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

We investigated pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in schools and the extent to which these beliefs differ between students at the beginning and at the end of university teacher training using a sample of 1,319 pre-service teachers at different stages of study from a large public university in Germany. Given the cross-sectional nature of our data, comparisons of the different student groups (Semesters 1–2 vs. Semester 6+) were based on a propensity score matching approach. We further examined the relationship between pre-service teachers’ beliefs and their opportunities to learn (OTL) using a subsample of 428 pre-service teachers. The findings suggest that beliefs about language-supportive teaching and egalitarian—but not multicultural—beliefs differed at the beginning and at the end of initial teacher training. Student teachers who studied German as a second language (GSL) more strongly endorsed beliefs about language-supportive teaching and egalitarian and multicultural beliefs than other students.

1. Introduction

The worldwide trend of migration has led to a steady rise in the number of students belonging to ethnic and cultural minorities in schools and, thus, increased the cultural and linguistic diversity in the classrooms. In many countries, immigrant students tend to exhibit lower academic performance compared with non-immigrant students (e.g., OECD, 2006, 2019). These performance differences have repeatedly been documented as especially pronounced in Germany (e.g., OECD, 2006; Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung, 2016; Henschel et al., 2022).

One factor that may influence academic achievement in culturally diverse settings is how teachers deal with cultural and linguistic diversity in the classroom (Gay, 2002; Aronson and Laughter, 2016; Schotte et al., 2022). Thus, teachers should show cultural awareness, recognizing the strengths of cultural diversity and adapting their instructional practice to the experiences, prior knowledge, and frames of reference of a diverse student population (Civitillo and Juang, 2019; Romijn et al., 2021). Furthermore, it is important that teachers support their students to develop the language skills needed for effectively participating in classroom discourse, reading and understanding textbooks and instructions, and communicating about domain-specific content (Schleppegrell, 2004; Lucas et al., 2015; Kalinowski et al., 2019). Gaining academic language proficiency is a challenging task for most students. However, immigrant students who often have limited contact to the language of instruction in their families and grow up multilingually have repeatedly been found to perform below their peers without immigrant background on measures of academic language proficiency (e.g., Uccelli et al., 2015; Heppt and Stanat, 2020). Therefore, teachers’ positive attitudes toward language-supportive teaching and their willingness and ability to effectively integrate language-support strategies into their regular classroom teaching might be particularly beneficial for immigrant students, creating an effective foundation for reducing immigration-related achievement gaps (Lucas et al., 2015; Kalinowski et al., 2019, 2020).

Although the precise ways that teachers’ behaviors might impact the learning and achievement of immigrant students are not yet clear, there is an increasing awareness that teachers require better training to effectively teach in classrooms that are linguistically and culturally diverse (e.g., Lucas, 2010; OECD, 2010; Morris-Lange et al., 2016). While this has long been acknowledged in the US, accompanied by respective study elements in teacher education programs (Lucas and Grinberg, 2008; Trent et al., 2008; Lucas, 2010), comparable investments in teacher education in other countries, including Germany, Norway, and New Zealand, have only begun in recent years (cf. Hammer et al., 2018; Kalinowski et al., 2019; Paetsch and Heppt, 2021; Bonness et al., 2022). Overall, opportunities to learn (OTL) for teaching in culturally diverse classrooms are still not sufficiently implemented in most teacher education programs in these countries (e.g., Ehmke and Lemmrich, 2018; Bonness et al., 2022) and programs differ widely regarding the number of course offerings and their compulsory nature (Baumann, 2017; Paetsch and Heppt, 2021).

Educational researchers have emphasized that teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity, i.e., their views on how to deal with a culturally and linguistically diverse student population, affect their teaching behavior in diverse classrooms (e.g., Hachfeld et al., 2011, 2015). In general, beliefs are regarded as essential for the professional development of teachers because they might play a significant role in shaping perceptions and behavior (Pajares, 1992; Thompson, 1992; Staub and Stern, 2002; Dubberke et al., 2008). Accordingly, learning opportunities (e.g., in seminars and practical exercises) created in initial teacher training might help develop pre-service teachers’ existing beliefs about cultural and linguistic diversity in a way that creates favorable conditions for later teaching in diverse classrooms.

To evaluate and improve the quality of initial teacher education programs offered by universities, it is crucial to identify the factors that contribute to developing student teachers’ professional beliefs, knowledge, and skills. Studies of teacher education suggest that variations in OTL can result in significant differences in pre-service teachers’ professional competence (Kennedy et al., 2008; Schmidt et al., 2011; Kleickmann and Anders, 2013; Ronfeldt et al., 2014; Stürmer et al., 2015). Studies have been undertaken on the relationship between OTL in university teacher training and pre-service teachers’ beliefs about teaching in linguistically and culturally diverse student populations. These studies provided mixed results, probably because of differences in study designs, research methods, and the study and control variables included. Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate differences between pre-service teachers’ beliefs at the beginning and end of their studies, including their beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in schools. In addition, we examined the relationships between pre-service teachers’ beliefs and their self-reported OTL, taking structural characteristics (school type and subjects) into account.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Teachers’ professional beliefs

Fives and Buehl (2012) define teacher beliefs as “subjective claims that the individual accepts or wants to be true” (p. 476). Teacher beliefs refer to an individual’s personal perspectives on teaching and learning, which can influence their classroom behavior and interactions with students (Pajares, 1992; Fives and Buehl, 2012). Teachers may have a complex web of beliefs, for example, beliefs about how to teach or beliefs about the acquisition of knowledge. Thus, several belief facets can be distinguished (Calderhead, 1996; Baumert and Kunter, 2006; Levin, 2015; Fischer, 2018).

Theoretical considerations and substantial empirical evidence suggest that teacher beliefs play a crucial role in shaping their interpretation of classroom situations and determining their actions (Calderhead, 1996; Hoy et al., 2006; Borg, 2011; Buehl and Beck, 2015). Teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning are linked to their behavior in the classroom and to students’ learning engagement (Schroeder et al., 2011) and academic performance (e.g., Staub and Stern, 2002; Dubberke et al., 2008; Levin et al., 2013). Whether and how these beliefs can be changed during teacher training and professional development, thus, is an important topic for both educational research and practice.

Teacher beliefs are frequently considered as dispositions, suggesting that they are relatively resistant to change (Kagan, 1992; Welch et al., 2010). There is, indeed, evidence that pre-service teachers’ pre-existing intuitive beliefs, which were formed during their past educational experiences (e.g., Kagan, 1992; Tatto, 1998) are relatively stable (Pajares, 1992; Levin, 2015; Paetsch et al., 2021). However, as Fives and Buehl (2012) point out, beliefs can vary in terms of their stability, falling along a spectrum where long-standing and deeply ingrained beliefs are on the stable end, while newer and more isolated beliefs are on the less stable end. This implies that certain beliefs, contrary to dispositions, might still be changeable, while others could remain resistant to change (see also Levin, 2015). In line with these considerations, a substantial body of research has shown that teachers’ beliefs can change (Schraw and Olafson, 2002; Schraw and Sinatra, 2004; Olafson and Schraw, 2006; Buehl and Fives, 2009; Levin, 2015; Civitillo et al., 2018; Sansom, 2020). Against this background, teachers’ beliefs are increasingly considered stable, but still malleable through teacher education (Petitt, 2011; Civitillo et al., 2018; Fischer and Lahmann, 2020). Specifically, empirical studies suggest significant—and most likely, reciprocal—relationships between OTL during teacher education and students’ beliefs (Busch, 2010; Biedermann et al., 2012; de Vries et al., 2013; Civitillo et al., 2018; Fischer and Ehmke, 2019). Thus, pre-service teachers’ beliefs and ideas about teaching certainly influence their career and course choices, and how they interpret their experiences during their studies (Pajares, 1992; Richardson, 1996; Levin, 2015). At the same time, the learning opportunities they encounter during their studies may also impact their beliefs (Levin, 2015).

2.2. Teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in schools

Research on teachers’ beliefs about teaching in linguistically and culturally diverse classrooms has predominantly focused on cultural diversity (for an overview, see Gay, 2010, 2015a). In this research on teachers’ so-called cultural beliefs, different forms of dealing with cultural diversity were distinguished: multicultural beliefs and egalitarian beliefs (e.g., Hachfeld et al., 2011; Costa et al., 2023). Although multicultural and egalitarian beliefs are both associated with positive attitudes toward cultural diversity, they differ in the extent to which they stress cultural differences and consider them important for teaching and learning. Teachers who endorse multicultural beliefs tend to acknowledge cultural differences and consider them enriching for classroom discourse (Park and Judd, 2005). Teachers with strong egalitarian beliefs, however, stress the equality of all students, regardless of their cultural and ethnic background. These teachers are ‘colorblind’, downplaying and ignoring differences between students with and without immigrant backgrounds. Theoretical considerations and empirical findings point to the advantageous effects of multicultural beliefs, which are typically associated with higher motivational orientations to teach in ethnically diverse classrooms and less stereotypical attitudes toward immigrant students than egalitarian beliefs (Gay, 2010; Hachfeld et al., 2015; Aragón et al., 2017). Egalitarian beliefs are associated with less willingness to adapt teaching behavior to a student population with a variety of cultural backgrounds (Hachfeld et al., 2015).

Another line of research more deliberately addresses teachers’ beliefs regarding teaching in linguistically diverse classrooms, i.e., classrooms with a high share of multilingual students who often have limited proficiency in the language of instruction (e.g., Lucas et al., 2015; Hammer et al., 2018; Fischer and Lahmann, 2020; Schroedler and Fischer, 2020). Beliefs that are considered important when teaching multilingual students include (1) the value attributed to students’ multilingualism and teachers’ willingness to include students’ first languages into their regular classroom teaching and (2) the beliefs about language-supportive teaching. The latter beliefs refer to the perceived responsibility and ability for integrating language-support strategies (e.g., identifying linguistic demands of content-related tasks, giving language-related feedback, asking open-ended, language-supportive questions) into regular subject-area teaching. Literature suggests that, despite a general appreciation of multilingualism (Haukås, 2016; Alisaari et al., 2019), many in-service teachers express reservations about including multilingual practices, such as language comparisons or encouraging students to use their first languages during group work, in their classroom teaching (see, however, Young, 2014; Pulinx et al., 2017; Tandon et al., 2017; Lange and Pohlmann-Rother, 2020; Lorenz et al., 2021). In particular, this seems to be the case for predominantly white and monolingual samples of teachers and when education policies reinforce monolingual practices in schools (Lucas et al., 2015; Pulinx et al., 2017).

Previous research on teachers’ beliefs about language-supportive teaching does not provide a fully conclusive picture. Several studies point to teachers’ reluctance to adapt their teaching behavior to the needs of linguistically diverse classrooms by actively providing linguistic scaffolds and fostering students’ language development in the language of instruction. A US-based qualitative study with 36 teacher candidates and novice teachers found that participants did not share strong orientations toward linguistically responsive teaching, as indicated by the small number of participants who related to aspects of scaffolding strategies for multilingual learners in their interviews or essays (Tandon et al., 2017). In line with these results, Pappamihiel (2007) analyzed reflective journals of pre-service teachers enrolled in large university in Florida, US, and found that participants tended to hold negative perceptions of multilingual students, as they required additional time resources. However, a number of recent studies suggest that pre-service teachers have positive beliefs about language-supportive teaching. Quantitative studies explicitly assessing participants’ beliefs revealed that pre-service teachers in Germany had fairly positive beliefs about language-supportive teaching (Schroedler and Fischer, 2020; Schroedler et al., 2022), although they often struggled to integrate language-support strategies into their regular classroom teaching (Hammer et al., 2016). Moreover, there are first indications for cross-cultural differences in teachers’ beliefs about both multilingualism and language-supportive teaching. Specifically, comparing teachers from Germany and the US, Hammer et al. (2018) reported more positive beliefs about multilingualism and teachers’ perceived responsibility for language facilitation for US-based teachers than for teachers based in Germany. This might reflect the comparably longer history of preparing teachers for the needs of multilingual students in the US in comparison to Germany.

2.3. Empirical findings on the relationship between pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in schools and their opportunities to learn in teacher education

Teacher programs are increasingly implementing formal OTL (e.g., seminars, professional development programs) aimed at developing teachers’ beliefs about cultural and linguistic diversity in schools (Trent et al., 2008; Castro, 2010). Yet, as indicated above, lesson elements that are compulsory for all pre-service teachers, irrespective of subject and school track, are still an exception in many countries, including Germany (Paetsch and Heppt, 2021; Bonness et al., 2022). Pre-service teachers of different school subjects and with different study aims will, therefore, vary in their OTL and hands-on experiences of teaching in linguistically and culturally diverse classrooms. This, in turn, should be reflected in differences in their cultural beliefs and their beliefs about language-supportive teaching (for reviews, see Lucas et al., 2015; Civitillo et al., 2018).

Civitillo et al. (2018) reviewed 36 mainly US-based studies, investigating effects of teacher training on pre-service teachers’ cultural beliefs. Although many studies found positive impacts of training programs on teachers’ beliefs concerning cultural diversity, this was particularly true for programs offering opportunities for experiential learning and reflection and discussion of cultural diversity. However, the authors concluded that many studies overlooked the fact that beliefs about cultural diversity in education have multiple dimensions, that most studies used qualitative methods and had small sample sizes, and that long-term effects of interventions were not examined. In addition, the research synthesis revealed that teacher training on cultural diversity is mainly conducted “with a standalone approach” as part of the general teacher training program (e.g., as a single class or seminar) rather than integrated or embedded in a broader diversity program (Civitillo et al., 2018, p. 55). Thus, cultural diversity training seems to be seldom fully integrated into the initial teacher education curriculum.

As for (pre-service) teachers’ beliefs about language-supportive teaching, several studies provide evidence for the role of OTL (Borg, 2011; Hammer et al., 2016; Fischer and Lahmann, 2020), and studies can be grouped into two main types. The first type aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of specific study programs or seminars designed for advancing (pre-service) teachers’ knowledge and skills in the domain of language-supportive teaching. The second type focused on regular teacher training programs without compulsory modules or seminars for preparing prospective teachers for teaching in linguistically and culturally diverse classrooms. Thus, this second group serves as a basis for identifying OTL that might benefit pre-service teachers’ development of professional beliefs during general teacher education.

Research on the effects of specific seminars or study programs on participants’ beliefs about language-supportive teaching provides mixed results. Borg (2011) conducted a longitudinal qualitative analysis of six UK-based language teachers who participated in an intensive 8-week professional development (PD) course, concluding that the PD had a significant impact on participants’ beliefs, although the degree of impact varied. While some of the teachers were more aware of their beliefs after completing the program, the full potential of the PD—ongoing and more productive reflection on their beliefs—was not attained. In contrast, two studies conducted with pre-service teachers in Germany employed quantitative pre-post designs for investigating whether seminars on language-supportive teaching in diverse classrooms, conducted over the course of one semester, altered participants’ beliefs (Fischer and Lahmann, 2020; Schroedler and Fischer, 2020). Both studies used questionnaire items to assess pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic responsiveness (i.e., their perceived need for linguistically responsive teaching) and their perceived responsibility for language facilitation during regular classroom teaching (Fischer et al., 2018). Drawing on data of 27 pre-service teachers, Fischer and Lahmann (2020) found a significant increase in participants’ beliefs about their responsibility for language facilitation. The study by Schroedler and Fischer (2020) was based on a larger sample of pre-service students from different universities (N = 296) and did not indicate any changes in these beliefs. It should be noted that these studies did not use a control group design. Therefore, it remains unclear whether observed changes in participants’ beliefs can be explained by the seminar contents.

A limited number of studies investigated the role of OTL more broadly, focusing on teacher education programs without obligatory courses on teaching in linguistically and culturally diverse classrooms. Assuming that students of language-intensive subjects—such as German, English, and German as a second language (GSL)—have more learning opportunities to address beliefs about culturally and linguistically diverse classrooms, they should hold more positive beliefs about diversity than students of other subjects (Hammer et al., 2016; Fischer and Ehmke, 2019), suggesting that the studied subject can be used as a general indicator of OTL. Drawing on data from a cross-sectional sample of pre-service teachers from 12 German universities, Hammer et al. (2016) found that, along with the study duration (number of semesters), studying GSL was positively related to students’ beliefs about linguistic responsiveness, as indicated by a small effect (r = 0.13). However, studying GSL was not associated with students’ perceived responsibility for language facilitation (r = 0.09), and no significant relations emerged for teachers focused on German and English.

Extending these findings, Fischer and Ehmke (2019) investigated bivariate correlations between indicators of OTL and pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity, and directly assessed OTL and its mediating role. Using a combined measure of pre-service teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism (i.e., whether students’ use of their first languages during classroom instruction was rather encouraged vs. suppressed) and responsibility for language facilitation as the dependent variable, the authors found that senior students who had participated in GSL courses and students who studied German as a school subject, showed more favorable beliefs about multilingualism and language facilitation. In contrast, male students studying mathematics as a school subject reported less favorable beliefs. While the positive effect of German was fully mediated by students’ self-reported OTL, the effects of the number of semesters and participation in GSL courses remained significant even after controlling for OTL.

In sum, previous findings present a mixed picture. While some studies provide evidence that teachers’ beliefs about teaching in linguistically and culturally diverse classrooms and on language-supportive teaching can be changed through teacher education programs, other studies found no changes in pre-service teachers’ beliefs. Moreover, studies investigating the role of OTL in shaping these beliefs yield inconsistent results and often have methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes, lack of control groups for investigating intervention effects, or overlooking complex relationships by using bivariate analyses. Studies have used several methods to operationalize OTL in the field of teaching in diverse classrooms, such as study duration, studied subject, or participation in a topic-specific course, and, thus, OTL are usually measured indirectly with indicators reflecting the amount of time and scope of relevant content that students engaged with during their studies.

3. Aim of the study and hypotheses

Pre-service teachers’ individual characteristics and their formal and informal learning opportunities are critical factors in predicting their learning processes and outcomes. By examining these factors, teacher education programs can lay the foundation for improving effectiveness in preparing future teachers. Considering the contradictory findings of prior research, it remains unclear to what extent pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in the classroom can be effectively changed during university teacher training. Nonetheless, the theoretical background suggests that pre-service teachers who participate in formal learning regarding teaching in diverse classrooms may change their beliefs (e.g., Civitillo et al., 2018). Accordingly, the primary aim of this study was to investigate whether pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in schools are related to OTL during university teacher training. To operationalize OTL, we used several indicators, including students’ study duration, their self-reported OTL in the field of teaching in diverse classrooms, whether they studied language-intensive subjects like German or a foreign language, and whether they attended topic-specific programs like GSL. We argue that senior students who have studied for longer, those studying language-intensive subjects, and those participating in topic-specific programs have more opportunities to learn about cultural and linguistic diversity in classrooms compared with other students (Hammer et al., 2016; Fischer and Ehmke, 2019).

We specified the following hypotheses:

1. Pre-service teachers’ cultural beliefs and beliefs about language-supportive teaching differ at the beginning and end of their university training.

2. Pre-service teachers’ self-reported OTL in the field of teaching in diverse classrooms relate to their cultural beliefs and their beliefs about language-supportive teaching.

Hypothesis 1 and 2 are supported by previous research results which showed that formal OTL (e.g., seminars, professional development programs) could change teachers’ beliefs about cultural and linguistic diversity in schools (Borg, 2011; Civitillo et al., 2018; Fischer and Lahmann, 2020). In addition, previous research revealed that students in topic-specific programs (e.g., GSL) have more learning opportunities in the field of linguistic diversity in classrooms (Hammer et al., 2016; Fischer and Ehmke, 2019) and tend to have more positive beliefs about linguistic responsiveness compared to students of other subjects (Hammer et al., 2016). Thus, we specified the following hypotheses:

3. Pre-service teachers who study language arts (GSL didactics, German, foreign languages) differ from pre-service teachers of other subjects in their cultural beliefs and their beliefs about language-supportive teaching (controlling for duration of study).

4. Differences in cultural beliefs and beliefs about language-supportive teaching between pre-service teachers who study language arts (GSL didactics, German, foreign languages) and those who do not, can be explained by the student teachers’ self-reported OTL in the field of teaching in diverse classrooms.

The study adds to the current body of research on pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in schools by (1) considering both cultural beliefs and beliefs about language-supportive teaching, taking into account the multidimensional and complex nature of these beliefs, (2) using several approaches to operationalize OTL during the initial phase of teacher education, and (3) using propensity score matching to investigate differences between beginning students and advanced students in a cross-sectional study.

4. Methods

4.1. Procedures

The data for the present study were collected within a larger research project, aimed at developing and strengthening teacher education at the University of Bamberg in Bavaria, Germany. Data collection was based on a cross-sectional multi-cohort design. The survey period began in the winter semester 2016/17 and ended in the winter semester 2018/19. Pre-service teachers at different time points in their studies were recruited during this period to participate in a survey. Data collection took place in each semester. During the whole time period students with varying durations of study participated. To ensure data integrity and prevent the possibility of students participating in the study multiple times, we implemented a procedure where each student was given a unique, self-generated, and anonymous code. The surveys took place with paper-pencil questionnaires in different courses. In addition, students who were about to complete their degrees were asked to participate in the survey directly after passing a state examination. Furthermore, there was an online survey to which pre-service teachers were invited to participate. Participation was voluntary, and participants were informed about the goals of the broader research project and about data handling in accordance with ethical standards for research involving human participants. Measures were taken to ensure the confidentiality of data usage and anonymity of the participants.

4.2. Sample

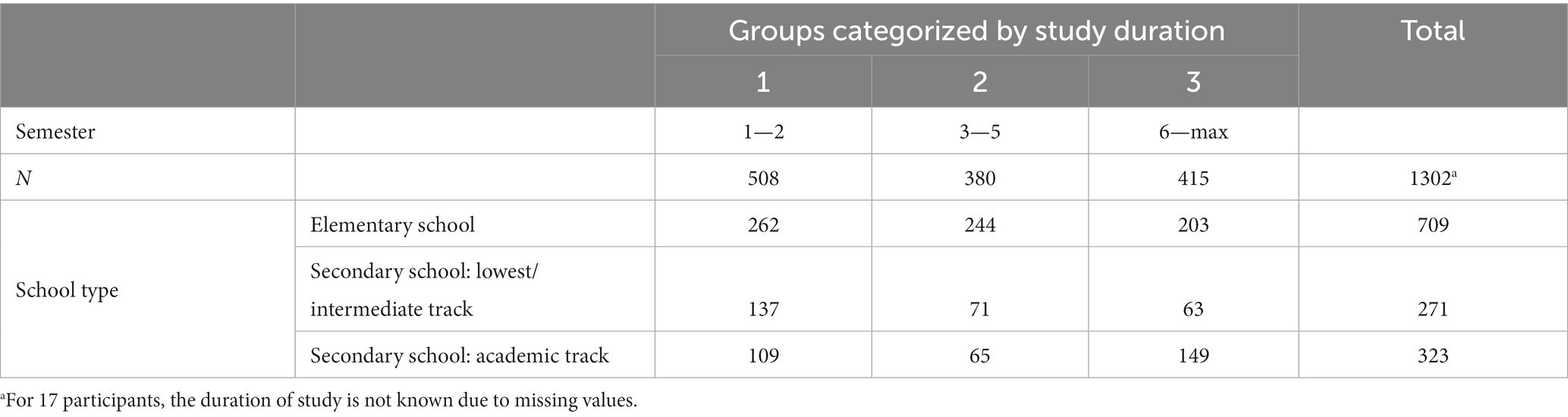

A total of 1,319 pre-service teachers from the University of Bamberg, a large public university in Bavaria, Germany participated in the study, 428 of which form the subsample to investigate hypotheses 2 and 4. The students aspired to teaching positions at different school types (elementary school: 54%; secondary school [middle school]: 21%; high school/upper secondary school [German Gymnasium]: 25%). Pre-service teachers at different stages of study were recruited for participation in the survey. The average participant was in their fourth semester (M = 4.37, SD = 3.57) and was 22 years old (M = 21.53, SD = 3.18). The majority of participants (82.9%) were female. The sample included students of all school subjects offered by the university during teacher training. The main subject groups of the participants were humanities (39.80%), foreign languages (36.16%), German (33.06%), social sciences (24.11%), and art/music (6.75%). To identify students at the beginning or end of their studies, the sample was divided into three groups based on the number of semesters they had attended university at the time they participated in the study (Group 1: Semesters 1–2, Group 2: Semesters 3–5, Group 3: Semester 6+; see Table 1).

Hypotheses 2 to 4 were examined using a subsample because OTL were only part of the survey if the course in which the survey took place was aimed at advanced students (i.e., 93% in Group 3 and 7% in Group 2). For this reason, information on OTL is only available for 428 pre-service teachers. Participants of this subsample were in their ninth semester on average (M = 8.59, SD = 2.49), with a mean age of 24 years (M = 23.69, SD = 2.45). As in the full sample, the majority of participants from this subsample (83.2%) were female. Within this subsample, 52.8% were enrolled in teacher training for elementary school, 15.7% for secondary school (middle school), and 31.5% for high school/upper secondary (German Gymnasium). Again, students of all school subjects offered during teacher training at the participating university were included in the sample. The main subject groups of the participants in the subsample were humanities (40.19%), German (36.2%), foreign languages (30.10%), social sciences (10.28%), and art/music (9.11%). In the subsample, 16.4 percent of the students participated in the topic-specific program GSL didactics (16.4%).

4.3. Instruments

For beliefs about language-supportive teaching and multicultural and egalitarian beliefs, we relied on validated scales used in previous research. To measure self-reported OTL, we designed a novel instrument tailored to the unique context of our study. Below we described each instrument in detail.

4.3.1. Beliefs about language-supportive teaching

To measure pre-service teachers’ beliefs about language-supportive teaching, we used the scales on linguistic responsiveness and responsibility for language facilitation by Hammer et al. (2016). The results of the reliability and factor analysis of the present data did not provide strong evidence for using the suggested two-factor solution. Kaiser’s criteria and the scree plot analysis corroborated the two-factor solution with eigenvalues greater than 1, accounting for 25.8% of the total variance. Among the factor solutions, the varimax-rotated two-factor solution was the most comprehensible, and most items loaded highly on only one of the two factors. However, the reliability coefficient for the items loading highly on Factor 2 did not yield satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.57). Therefore, in the following analyses, we used a single scale on beliefs about language-supportive teaching, consisting of 13 items, which loaded highly on Factor 1 (factor loading >0.3). A sample item from the scale is “Teachers should consider the linguistic skills of their students when selecting tasks.” All items were rated on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“strongly agree”). The reliability coefficient of the scale was α = 0.72.

4.3.2. Multicultural and egalitarian beliefs

The Teacher Cultural Beliefs Scale (TCBS; Hachfeld et al., 2011) was used to assess pre-service teachers’ expressions of multicultural and egalitarian beliefs, with response options on a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (6). The scale consists of six items measuring multicultural beliefs (e.g., “In the classroom, it is important to be responsive to differences between cultures”) and four items measuring egalitarian beliefs (e.g., “In the classroom, it is important that students of different origins recognize the similarities that exist between them”). The reliability coefficient was α = 0.85 for both scales.

4.3.3. Self-reported opportunities to learn

In general, pre-service teachers in Germany have the opportunity to set their own content focus in their studies and choose from a wide range of electives within the required curriculum, therefore variance in topic-related learning opportunities was to be expected (Terhart, 2021). A questionnaire was used to record the students’ self-reported OTL in the field of teaching in diverse classrooms. The development of the scale was aligned with the measure for recording educational learning opportunities in the BilWiSS study, aimed at developing and validating an assessment for teachers’ educational knowledge (Kunina-Habenicht et al., 2013). The scale was not administered to students in the earlier semesters of study, and data are only available for students with advanced study durations (see description of the subsample). The students were asked to provide information about their OTL on an ordinal scale. Students were asked: “To what extent have the following areas been addressed throughout your teacher education program to date?” Respondents were asked to answer four items, indicating the frequency for four areas (Dealing with cultural and socioeconomic heterogeneity, Dealing with linguistic diversity, Inclusion, and Dealing with heterogeneous learning pre-conditions [i.e., adaptive teaching, differentiation within learner groups]) with the response options “not at all” (1), “in one session” (2), “in several sessions” (3), “in a whole course” (4), or “in several courses” (5). To create an interval-like scale for further analysis, these categorical variables were dichotomized by transforming the response options 1 and 2 into 0 (in one session at maximum), and the response options 3 to 5 into 1 (from several sessions up to several courses). These binary responses were aggregated across the four areas, resulting in a sum score for each participant. The reliability coefficient of the resulting scale was α = 0.83.

4.4. Analysis

Study duration represents a sociodemographic variable that cannot be varied experimentally. This circumstance leads to some challenges when investigating the relationships between this variable and our outcome variables (concerning H1). Other sociodemographic variables, such as type of school or subject studied, were also expected to be associated with pre-service teachers’ beliefs (Glock and Klapproth, 2017). To investigate differences between pre-service teachers in Group 1 and Group 3 (see Table 1), we drew on propensity score matching methods, using the R package MatchIt (method = subclass; Ho et al., 2007). Multivariate matching procedures are increasingly used in the social sciences (Thoemmes and Kim, 2011) because they are efficient in simultaneously controlling for many covariates (Adelson, 2013). Participants of the treatment group (i.e., students with advanced study duration; Group 3) were assigned to one or more participants of the control group (i.e., first or second-semester students; Group 1) based on their covariate characteristics. This resulted in a data set with a reduced sample size, with more similar distributions of covariates between the two groups.

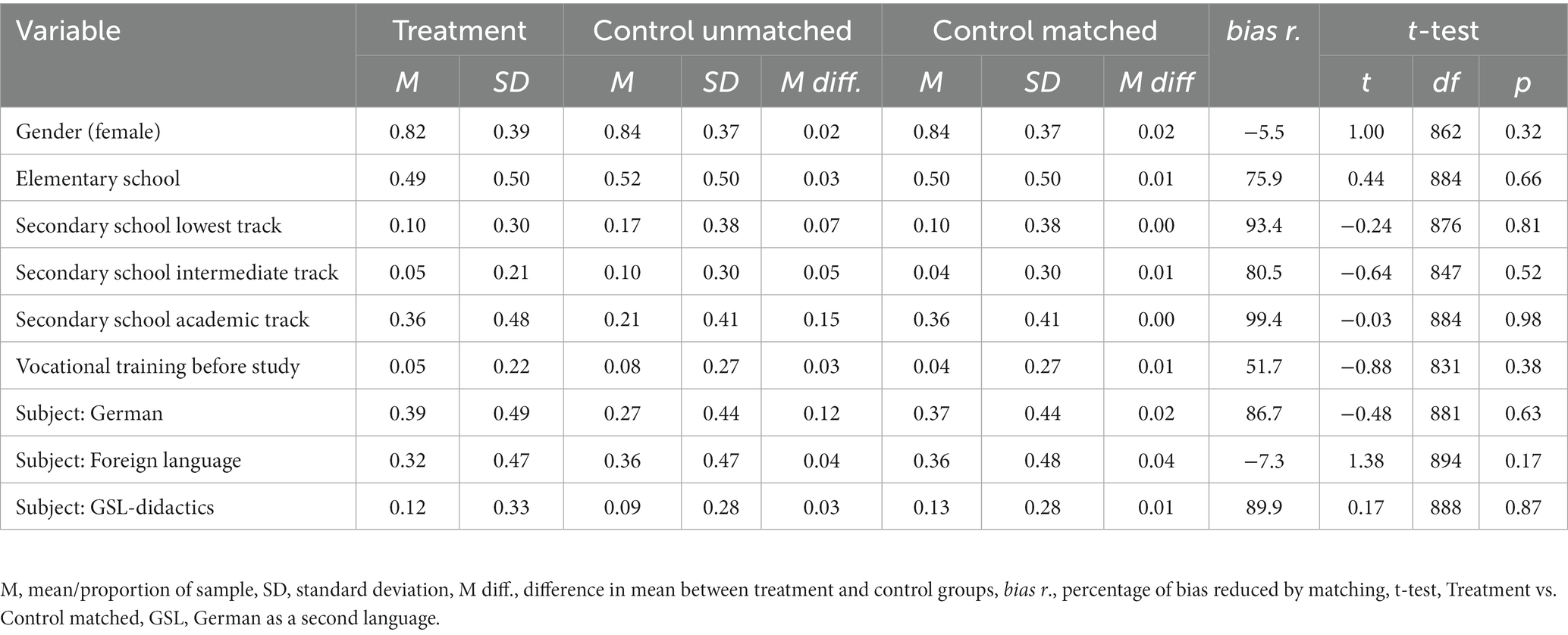

Matching procedures can be systematized by the actual process of matching the units from the two groups to each other. These differ, for example, in the number of study units assigned, their single or multiple uses, or their allowed maximum distance (for an overview, see Ho et al., 2007). To find a well-balanced solution, one-to-one nearest-neighbor, subclass, exact, and full matching were performed in this study. The subclass method, which distributes participants of both groups into a number of subclasses (in this case five) based on their covariate characteristics, and then assigns weights to them, provided a data set without significant mean differences in covariate distribution between the groups while retaining the highest effective sample size (see Supplementary material). This data set was used for further analyses. All used covariates were dummy-coded (Table 2).

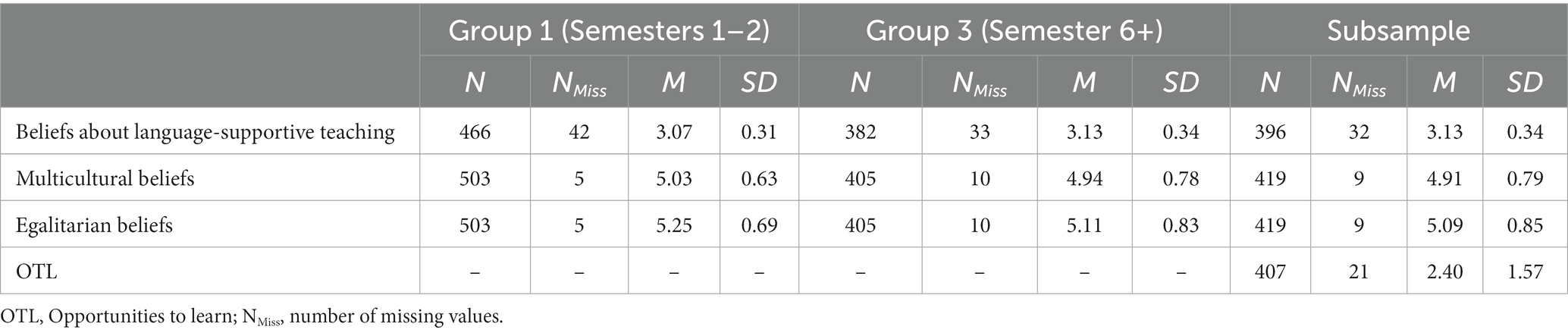

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of group 1 (Semesters 1–2) and 3 (Semester 6+) and the subsample of advanced students who were administered the OTL scales.

For further statistical analysis, we used Mplus 8.7 (Muthén and Muthén, 2012) with robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimation, which allowed us to perform path modeling with full information maximum likelihood (FIML). With a path model, we investigated the differences between Group 1 (Semesters 1–2) and Group 3 (Semester 6+) using weighted data (subclass matched; H1). Furthermore, path models using school type and study duration as control variables were specified (H2–H4). To deal with the small number of missing values, the full information maximum likelihood approach (FIML) implemented in Mplus was employed. Significance testing was performed at the 0.05 level (two-tailed).

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive statistics

The descriptive results for Group 1 (Semesters 1–2) and 3 (Semester 6+) are presented separately in Table 2. The means for beliefs about language-supportive teaching exceeded the theoretical mean of the scale (M = 2.5) indicating that students strongly endorsed these beliefs, with the highest values observed in Group 3 (Mc1 = 3.07, SD c1 = 0.31; Mc3 = 3.13, SD c3 = 0.34). The mean scores for multicultural beliefs and egalitarian beliefs also exceeded the theoretical mean of the scale (M = 3.5) with higher means in Group 1 than in Group 3 (multicultural beliefs: Mc1 = 5.03, SDc1 = 0.63; Mc3 = 4.94, SDc3 = 0.78; egalitarian beliefs: Mc1 = 5.25, SDc1 = 0.69; Mc3 = 5.11, SDc3 = 0.83). Comparing these results with findings from prior research with German samples, the multicultural and egalitarian beliefs were lower in Hachfeld et al. (2015) and Schotte et al. (2022) than in the current study. Yet, in interpreting these differences, it should be considered that Hachfeld et al. (2015) surveyed teachers who were at the beginning of their professional careers while Schotte et al. (2022) included a sample of German in-service teachers.1 Results for OTL in the subsample of advanced students revealed mean scores (M = 2.40, SD = 1.57) just below the theoretical mean of the scale (M = 2.5), indicating that the students attended at least one course on average for most of the topics. The categorical frequencies of OTL items (before dichotomizing) are displayed in Supplementary material.

5.2. Results of propensity score matching

Results of all matching methods are available in the Supplementary material and provide evidence that the covariates were well-balanced after the subclass matching. Table 3 presents means and standard deviations of the covariates entering the matching process before and after subclass matching.

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, and mean differences between treatment (Semester 6+) and control (Semesters 1–2) unmatched and matched via subclass propensity score matching.

5.3. Comparison of beliefs at the beginning and end of students’ study

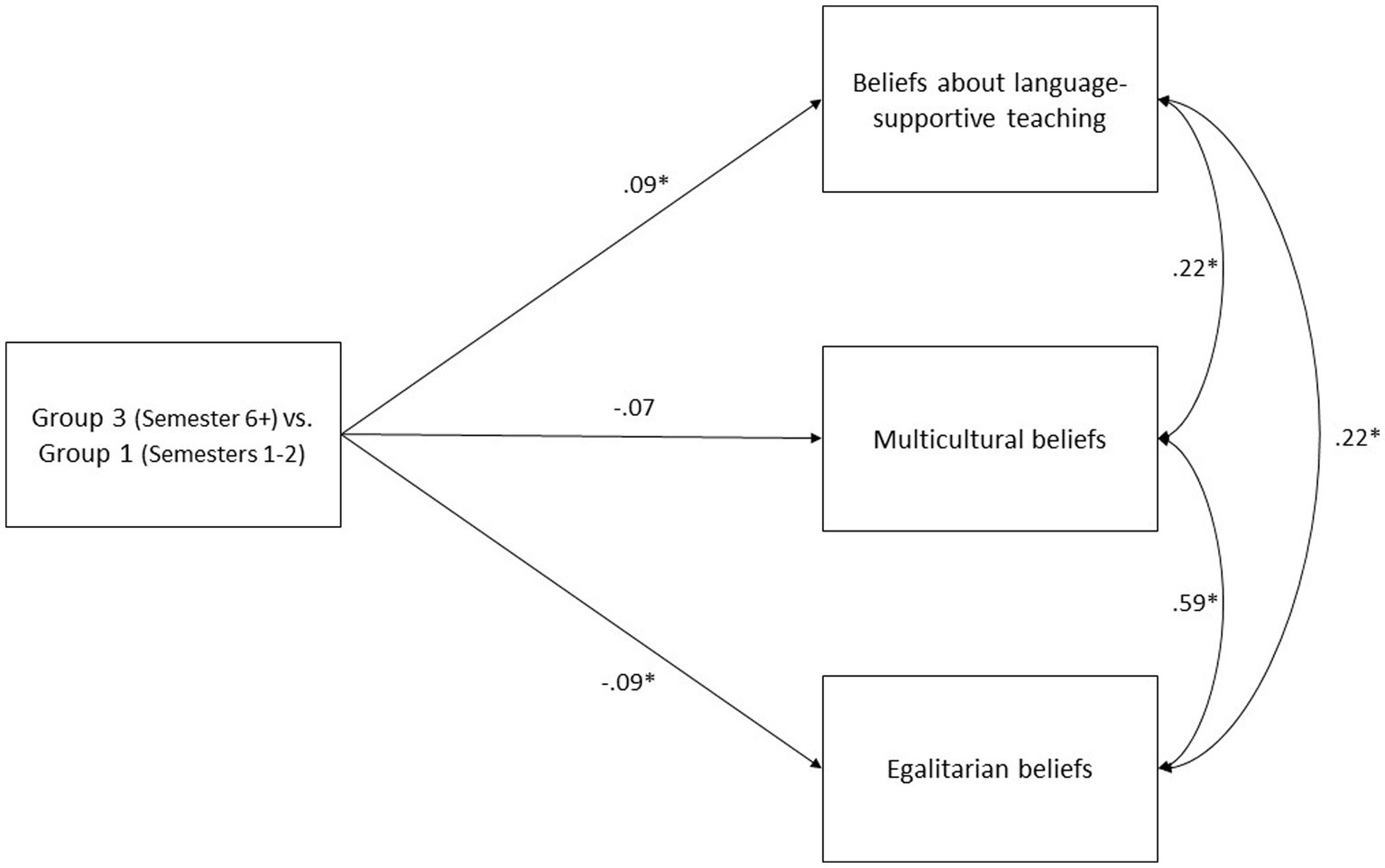

The groups (Semesters 1–2 vs. Semester 6+) resulting from subclass matching were compared using path modeling with the calculated matching weights. Results revealed significant differences for beliefs about language-supportive teaching (β = 0.09, p = 0.01) and egalitarian beliefs (β = −0.09, p = 0.01; see Figure 1). Differences in multicultural beliefs were marginally below the level of significance (β = −0.07, p = 0.06). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is partially accepted. The direction of the differences should be noted. Students from Group 3 more strongly endorsed beliefs about language-supportive teaching than students from Group 1, but showed slightly lower expressions of multicultural and egalitarian beliefs compared with Group 1. The path model also revealed a significant correlation between the different belief facets with r = 0.59 for egalitarian and multicultural beliefs (cf. Hachfeld et al., 2015) and r = 0.22 for beliefs about language-supportive teaching with both multicultural and egalitarian beliefs.

Figure 1. Comparison of pre-service teachers’ beliefs at the beginning (Semesters 1–2) and end (Semester 6+) of their university training.

5.4. Relationship between self-reported opportunities to learn and teaching subject with pre-service teachers’ beliefs

Hypothesis 2 referred to the relationship between students’ self-reported OTL and their beliefs about teaching culturally and linguistically diverse classes. It was tested using path modeling with the three belief facets as dependent variables. The type of school (reference category: academic track) and the number of semesters studied were taken into account as control variables (Table 4; Model 1). Results revealed a significant effect for self-reported OTL on pre-service teachers’ beliefs about language-supportive teaching (β = 0.12, p = 0.03), indicating that more OTL during university teacher training are linked to more favorable beliefs about language-supportive teaching. However, significant effects of OTL on pre-service teachers’ multicultural (β = 0.05, p = 0.41) and egalitarian beliefs did not emerge (β = 0.05, p = 0.40). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is partially accepted.

Table 4. Results from path analysis using the subsample: predictors of pre-service teachers’ beliefs.

Differences between pre-service teachers who study a language and pre-service teachers of other subjects were examined using path modeling, with a dummy-variable included as a predictor for each of the subjects (German, foreign languages, GSL didactics). Results showed significant differences between GSL didactic students and other students in their beliefs about language-supportive teaching (β = 0.18, p < 0.001), and their multicultural (β = 0.20, p < 0.001) and egalitarian beliefs (β = 0.13, p = 0.01), indicating that studying a specific program like GSL is linked to stronger endorsement of all three beliefs (Table 4; Model 2). The analyses further revealed significant differences between multicultural beliefs of students who study German and students of other school subjects (β = −0.10, p = 0.03). Students studying German had lower expressions of multicultural beliefs compared with others. No differences were found between beliefs of pre-service teachers who study a foreign language compared with other pre-service teachers. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is partially accepted.

Hypothesis 4 postulated that differences in the beliefs between pre-service teachers who study language arts and other pre-service teachers can be explained by pre-service teachers’ self-reported OTL. This (mediation) hypothesis was tested by adding self-reported OTL as a predictor in the path model (Table 4; Model 3). These differences could possibly be explained by OTL because differences were only found for GSL didactics and German (see Model 2).

Results revealed significant differences between pre-service teachers who study GSL didactics and other pre-service teachers in their cultural beliefs and beliefs about language-supportive teaching, even after controlling for OTL in the field of teaching in diverse classrooms, school track, and number of semesters. OTL had no significant effect on students’ beliefs, indicating that the differences between the two groups could not be explained by their self-reported OTL in the field of teaching in diverse classrooms. Although the differences in multicultural beliefs between students who study German and other students were no longer significant after controlling for OTL, the effect size did not change from Model 2 (β = −0.10, p = 0.03) to Model 3 (β = −0.10, p = 0.06) and no statistically significant effect emerged for OTL. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 must be rejected. Across all models for predicting pre-service teachers’ beliefs, the amount of explained variance ranged from 0.01 for OTL as a predictor of multicultural and egalitarian beliefs (Model 1) to 0.07 for the full model (including OTL and the subjects GSL didactics, German, and foreign languages) for explaining beliefs about language-supportive teaching (Model 3). This small amount of explained variance suggests that further variables which were not considered in the present analyses play an important role in shaping pre-service teachers’ beliefs.

6. Discussion

Teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity are complex and influenced by a range of factors, including teachers’ own backgrounds, experiences, and professional development (Levin, 2015; Gay, 2015a,b; Civitillo et al., 2018). A better understanding of the sources of these complex beliefs can help in supporting the development of teachers’ competence and in promoting culturally and linguistically responsive teaching (Levin, 2015). Against this backdrop, the present study aimed to investigate whether pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in school are related to OTL during university teacher training. By using several approaches for operationalizing OTL and considering multicultural beliefs, egalitarian beliefs, and beliefs about language-supportive teaching, the study sought to expand prior research on the extent to which pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in the classroom can be effectively changed during university teacher training (Levin, 2015; Civitillo et al., 2018; Fischer and Ehmke, 2019).

First, in line with our hypothesis, the study showed that there were significant differences in beliefs about language-supportive teaching and egalitarian beliefs between a matched sample of pre-service teachers at the beginning and end of their studies. This finding corroborates previous research showing that interventions can contribute to a change in teachers’ beliefs (Schraw and Olafson, 2002; Schraw and Sinatra, 2004; Olafson and Schraw, 2006; Buehl and Fives, 2009; Civitillo et al., 2018; Sansom, 2020). It should be noted, however, that the direction of the differences in our study was not consistent across all beliefs—students from Group 3 (Semester 6+) showed significantly lower expressions of egalitarian beliefs than students in Group 1 (Semesters 1–2). However, the lower approval of egalitarian beliefs at the end of university teacher training is in line with theoretical assumptions (Gay, 2010; Aragón et al., 2017). Hachfeld et al. (2015) showed that teachers who highlight similarities among students may be less inclined to tailor their instruction to meet the unique needs of immigrant students. Furthermore, the stronger endorsement of beliefs about language-supportive teaching at the end of teacher training aligns with the findings of Fischer and Lahmann (2020) who reported a significant increase in participants’ beliefs about their responsibility for language facilitation during a one-semester course. However, our findings do not support the assumption that pre-service teachers’ multicultural beliefs at the end of university teacher training differ from those in the early phases of teacher training. It is worth noting that the participants in our study reported high levels of multicultural and egalitarian beliefs, and as a result, the range of responses on these scales was somewhat limited.

Second, the study found that self-reported OTL in the field of teaching in diverse classrooms was related to pre-service teachers’ beliefs about language-supportive teaching, but not to their multicultural or egalitarian beliefs. Thus, our findings corroborate the results of Fischer and Ehmke (2019) who showed a significant relationship between self-reported OTL in the field of language-supportive teaching and students’ beliefs. However, the results do not support the hypothesis that the number of self-reported topic-specific learning opportunities (e.g., in seminars and practical exercises) in initial teacher training contributes to the development of pre-service teachers’ multicultural or egalitarian beliefs. A possible explanation for the divergent result patterns for beliefs about language-supportive teaching on the one hand, and egalitarian and multicultural beliefs on the other, is that the measurement of self-reported OTL may have been more suitable for assessing OTL that are important for dealing with linguistic diversity than for dealing with cultural diversity in the classroom. Specifically, the OTL scale did not differentiate between different topics in the field of teaching in diverse classrooms. Thus, the measurement may not accurately reflect all perceived learning opportunities that are relevant for shaping pre-service teachers’ beliefs about culturally diverse student bodies.

Third, in our study, pre-service teachers who studied GSL didactics were found to have more pronounced beliefs about language-supportive teaching as well as multicultural and egalitarian beliefs than teachers who studied other subjects. The studied subject is seen as an indicator of OTL (Hammer et al., 2016; Fischer and Ehmke, 2019) because students of language-intensive subjects are more likely to have many (high quality) learning opportunities that address beliefs about culturally and linguistically diverse classrooms compared with students of other subjects. Our results corroborate findings from other studies (Hammer et al., 2016; Fischer and Ehmke, 2019), highlighting that studying GSL was positively related to students’ beliefs about linguistic responsiveness (i.e., whether they considered linguistic demands important when planning and teaching content subjects). However, for pre-service teachers who studied German, we found lower average scores in multicultural beliefs compared with other students. For pre-service teachers who studied at least one foreign language, there were no differences in beliefs about cultural and linguistic diversity compared with others. These results are in line with Hammer et al. (2016), but contradict Fischer and Ehmke (2019) who found students who studied German as a school subject having favorable beliefs about multilingualism and language facilitation. One explanation for this finding is that the composition of the comparison group of students from other disciplines possibly varied across studies. Specifically, while the majority of students in our comparison group studied humanities and social sciences, the comparison group in Fischer and Ehmke, 2019 study comprised pre-service teachers studying mathematics or natural sciences. Therefore, future studies should carefully consider the composition of the comparison group to ensure its representativeness. Students’ study behavior needs to be investigated, in addition to their subjects, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how different factors may affect their OTL.

Fourth, the differences we observed between pre-service teachers who studied GSL and other pre-service teachers in their cultural beliefs and beliefs about language-supportive teaching could not be attributed to their self-reported OTL in the field of teaching in diverse classrooms. Interestingly, we found that the effect of self-reported OTL on pre-service teachers’ beliefs about language-supportive teaching disappeared after accounting for their subjects of study. A possible explanation is that GSL students might have had more topic-related and—importantly—higher quality OTL than students of other subjects. These could, for instance, include opportunities for experiential learning and exposure to authentic learning environments that allow the active application of newly acquired knowledge and opportunities for reflecting on and discussing beliefs and experiences. Such learning environments have been shown to shape pre-service teachers’ beliefs about cultural and linguistic diversity (Civitillo et al., 2018) and are more likely to be implemented in structured study programs with a specific focus on diverse student populations than in traditional teaching programs (Civitillo and Juang, 2019). Including indicators of both quantity and quality of OTL in future research will help to capture a more holistic picture of pre-service teachers’ perceived learning opportunities and their associations with beliefs and other aspects of professional competence.

It can be assumed that students who study GSL have more favorable beliefs about teaching in linguistically and culturally diverse classrooms—even before they start initial teacher education—compared with other students. They may have a personal connection to the topic, such as their own experiences with diversity. This self-selection process might impact the diversity of the students who study GSL, as those who are not attracted to GSL or do not see themselves as capable of being successful teachers in diverse classrooms may be less likely to select this subject. This assumption is in line with other empirical studies that showed that sociodemographic variables such as type of school or subject studied (e.g., Glock and Klapproth, 2017) and personality traits (Unruh and McCord, 2010) are associated with pre-service teachers’ beliefs.

Our descriptive findings indicated that both groups—pre-service teachers at the beginning and at the end of their studies—strongly endorsed language-supportive teaching and have pronounced multicultural and egalitarian beliefs. Comparison with previous studies suggests that the students in the current study may have stronger multicultural and egalitarian beliefs than teachers already working in the profession (Hachfeld et al., 2015; Schotte et al., 2022)—creating a ceiling effect that limited the change that could have possibly occurred from the beginning to the end of their teacher training.

We employed several indicators to define OTL, including study duration, student teachers’ self-reported OTL in the field of teaching in diverse classrooms, and whether they studied language-intensive subjects and attended topic-specific programs like GSL. The study did not yield clear-cut results on the extent to which learning opportunities in initial teacher education contribute to students’ beliefs. Our results varied depending on how we operationalized OTL and on the belief facets under examination. While we found differences between students at the beginning and end of their studies on two of the three investigated belief facets, we also observed more pronounced beliefs on all facets among students who studied GSL didactics. Notably, however, neither self-reported OTL nor study duration explained these differences. When interpreting these results, it should be noted that we used a subsample of advanced students to investigate the impact of self-reported OTL. This approach ensured that the participating students actually had the possibility to benefit from OTL in the field of linguistic and cultural diversity, resulting in a fairly low share of missing values. At the same time, it may have reduced the variance in self-reported OTL.

6.1. Limitations

The study had some limitations worth noting. First, the scales used to measure cultural beliefs and beliefs about language-supportive teaching cover a wide range of ideas. These scales have been tested and proven effective in previous studies (e.g., Hachfeld et al., 2015; Hammer et al., 2016). However, it is possible that using more detailed measures that focus on specific aspects of cultural beliefs and beliefs about language-supportive teaching could have led to a slightly different pattern of results. There are several ways to understand how teachers’ beliefs can change. For instance, their beliefs can be reinforced and expanded, and become more explicit and easily expressed. Teachers can also learn how to apply their beliefs in real-life situations and establish connections between their beliefs and theoretical concepts (Debreli, 2012).

Second, the study relied on self-reported measures of beliefs and OTL. The data may contain biases resulting from participants’ tendency to provide socially desirable responses, and should ideally be validated by alternative methods such as implicit assessments of students’ beliefs or data from examination offices for monitoring course participation and success. Third, the measurement of OTL was rather rough, as it did not differentiate between different topics, or the exact number of courses attended. In particular, transforming the ordinal scale into an interval scale has led to an information loss as frequency categories were merged during the dichotomization process. As the OTL scale broadly covered different aspects of dealing with diversity in the classroom, a more detailed assessment of the specific lesson contents (e.g., language-support strategies, strategies for adaptive teaching, designing inclusive and culturally sensitive teaching materials) is imperative for future research. Fourth, the study used a cross-sectional design, which limits the possibilities for drawing causal inferences. Thus, bidirectional relations and reverse causality are possible. For example, it is possible that pre-service teachers’ beliefs influence their perceptions and behaviors during their studies, and their interpretations of their experiences (Pajares, 1992; Richardson, 1996; Levin, 2015), which may lead to different uptakes of learning opportunities during initial teacher education. However, to investigate the differences between pre-service teachers at the outset and end of their study, we used propensity score matching. A main benefit of this technique when comparing two groups is that it can help to ensure that any observed differences between the groups are due to the treatment rather than to differences in the characteristics of the individuals in the groups. By matching individuals based on their propensity scores, we created groups that were more comparable. Nevertheless, potential differences between the investigated groups regarding their curricula or voluntary internships, that might have resulted in different OTL, were not taken into account.

A fifth limitation is that the study was conducted at a single university in Bavaria, Germany, which limits the generalizability of the findings. However, our sample included students covering a range of school subjects and types of school with varying study durations, and findings provide insights into the formation of professional beliefs that can be expected by general teacher training that does not involve mandatory courses in the field of linguistic and cultural diversity for all students. The limitations outlined in this section should be addressed in future research by using different measures of OTL, longitudinal designs, and by conducting similar studies in different contexts. Further research is needed that clearly separates self-selection effects and the effect of learning opportunities.

7. Conclusion

This study extends the existing literature on predictors of pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in schools. The study is the first to use propensity score matching to simultaneously control for many covariates and reveal differences in pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in schools between student teachers at the beginning and end of their studies. Our research provides valuable insights into the relationship between pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in schools and OTL during university teacher training, even though the findings were not consistent for all investigated belief facets. Future research should consider the effect of OTL in a nuanced way, possibly unraveling the role of high-quality OTL. Furthermore, research is needed to investigate the extent to which language-supportive beliefs translate into teaching practices that promote both domain-specific knowledge acquisition and language development in students.

Given the rather weak associations between OTL and pre-service teachers’ beliefs, our study indicates that the influence of general teacher education on pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in schools is limited. Based on our finding that the endorsement of language-supportive beliefs was mainly related to studying GSL didactics, and on cross-cultural comparisons, indicating more positive beliefs about language-supportive teaching in countries with a longer history of implementing courses on linguistic and cultural diversity into their teacher education programs (Hammer et al., 2018), it might be beneficial for teacher education programs to offer additional mandatory and immersive courses designed for pre-service teachers across all disciplines. These courses could emphasize experiential learning, facilitating meaningful engagement with the challenges posed by diverse classrooms. Making voluntary opportunities more attractive to pre-service teachers of all subjects by offering additional, recognized certificates or other incentives could also be an effective strategy for increasing the number of pre-service teachers who gain insights into teaching in linguistically and culturally diverse classrooms and feel inclined to adjust their teaching to these students’ needs.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because informed consent signed by participants stated that data were only accessible to the authors of this study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to JP, amVubmlmZXIucGFldHNjaEB1bmktYmFtYmVyZy5kZQ==.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JP: conceptualization, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing, data curation, formal analysis, and funding acquisition. BH: conceptualization, writing – original draft, and writing – review & editing. JM: data curation and formal analysis. All authors discussed the results, contributed to the article, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project is part of the Qualitätsoffensive Lehrerbildung, a joint initiative of the Federal Government and the Länder, which aims to improve the quality of teacher training. The program is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01JA1915).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1236415/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The mean values for multicultural beliefs were M = 4.71 in the study by Hachfeld et al. (2015) and M = 4.89 in the study by Schotte et al. (2022). For egalitarian beliefs, the mean values were M = 4.89 (Hachfeld et al., 2015) and M = 4.99 (Schotte et al., 2022).

References

Adelson, J. L. (2013). Educational research with real-world data: reducing selection bias with propensity score analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 18:nk33. doi: 10.7275/4nr3-nk33

Alisaari, J., Heikkola, L. M., Commins, N., and Acquah, E. O. (2019). Monolingual ideologies confronting multilingual realities. Finnish teachers’ beliefs about linguistic diversity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 80, 48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.01.003

Aragón, O. R., Dovidio, J. F., and Graham, M. J. (2017). Colorblind and multicultural ideologies are associated with faculty adoption of inclusive teaching practices. J. Divers. High. Educ. 10, 201–215. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000026

Aronson, B., and Laughter, J. (2016). The theory and practice of culturally relevant education: a synthesis of research across content areas. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 163–206. doi: 10.3102/0034654315582066

Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung (2016). Bildung in Deutschland 2016 [Education in Germany 2016]. Bertelsmann. doi: 10.3278/6001820ew

Baumann, B. (2017). “Sprachförderung und Deutsch als Zweitsprache in der Lehrerbildung - ein deutschlandweiter Überblick [Language promotion and German as a second language in teacher training - a Germany-wide outlook]” in Deutsch als Zweitsprache in der Lehrerbildung. eds. M. Becker-Mrotzek, P. Rosenberg, C. Schroeder, and A. Witte (New York: Waxmann), 9–26.

Baumert, J., and Kunter, M. (2006). Stichwort: Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften [keyword: teachers’ professional competence]. Z. Erzieh. 9, 469–520. doi: 10.1007/s11618-006-0165-2

Biedermann, H., Brühwiler, C., and Krattenmacher, S. (2012). Lernangebote in der Lehrerausbildung und Überzeugungen zum Lehren und Lernen. Beziehungsanalysen bei angehenden Lehrpersonen [learning opportunities in teacher training and convictions regarding teaching and learning. Relationship analyses among future teachers]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 58, 460–475.

Bonness, D. J., Harvey, S., and Lysne, M. S. (2022). Teacher language awareness in initial teacher education policy: a comparative analysis of ITEdocuments in Norway and New Zealand. Language 7:208. doi: 10.3390/languages7030208

Borg, S. (2011). The impact of in-service teacher education on language teachers’ beliefs. System 39, 370–380. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2011.07.009

Buehl, M. M., and Beck, J. S. (2015). “The relationship between Teachers' beliefs and Teachers' practices” in International handbook of research on teachers' beliefs. eds. H. Fives and M. G. Gill (England: Routledge), 66–82.

Buehl, M. M., and Fives, H. (2009). Exploring teachers’ beliefs about teaching knowledge: where does it come from? Does it change? J. Exp. Educ. 77, 367–408. doi: 10.3200/JEXE.77.4.367-408

Busch, D. (2010). Pre-service teacher beliefs about language learning: the second language acquisition course as an agent for change. Lang. Teach. Res. 14, 318–337. doi: 10.1177/1362168810365239

Calderhead, J. (1996). Teachers: Beliefs and knowledge. In handbook of educational psychology (pp. 709–725). US: Prentice Hall International.

Castro, A. J. (2010). Themes in the research on preservice teachers’ views of cultural diversity: implications for researching millennial preservice teachers. Educ. Res. 39, 198–210. doi: 10.3102/0013189x10363819

Civitillo, S., and Juang, L. P. (2019). “How to best prepare teachers for multicultural schools: challenges and perspectives” in Youth in superdiverse societies: Growing up with globalization, diversity, and acculturation. eds. P. Titzmann and P. Jugert (England: Routledge), 285–301.

Civitillo, S., Juang, L. P., and Schachner, M. K. (2018). Challenging beliefs about cultural diversity in education: a synthesis and critical review of trainings with pre-service teachers. Educ. Res. Rev. 24, 67–83. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2018.01.003

Costa, J., Franz, S., and Menge, C. (2023). Stays abroad of pre-service teachers and their relation to teachers' beliefs about cultural diversity in classrooms. Teach. Teach. Educ. 129:104137. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104137

de Vries, S., Jansen, E. P. W. A., and van de Grift, W. J. C. M. (2013). Profiling teachers' continuing professional development and the relation with their beliefs about learning and teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 33, 78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2013.02.006

Debreli, E. (2012). Change in beliefs of pre-service teachers about teaching and learning English as a foreign language throughout an undergraduate pre-service teacher training program. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 46, 367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.124

Dubberke, T., Thamar, M., McElvany, N., Brunner, M., and Baumert, J. (2008). Lerntheoretische Überzeugungen von Mathematiklehrkräften: Einflüsse auf die Unterrichtsgestaltung und den Lernerfolg von Schülerinnen und Schülern. [mathematics teachers' beliefs and their impact on instructional quality and student achievement]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie / German J. Educ. Psychol. 22, 193–206. doi: 10.1024/1010-0652.22.34.193

Ehmke, T., and Lemmrich, S. (2018). “Bedeutung von Lerngelegenheiten für den Erwerb von DaZ-Kompetenz [the role of learning opportunities to learn in the development of GSL skills]” in Professionelle Kompetenzen angehender Lehrkräfte im Bereich Deutsch als Zweitsprache. eds. T. Ehmke, S. Hammer, A. Köker, U. Ohm, and B. Koch-Priewe (New York: Waxmann), 201–219.

Fischer, N. (2018). Professionelle Überzeugungen von Lehrkräften - vom allgemeinen Konstrukt zum speziellen fall von sprachlich-kultureller Heterogenität in Schule und Unterricht [professional beliefs of teachers - from a general construct to a specific case of linguistic-cultural heterogeneity in schools and classrooms]. Psychol. Erzieh. Unterr. 65, 35–51. doi: 10.2378/peu2018.art02d

Fischer, N., and Ehmke, T. (2019). Empirische Erfassung eines messy constructs: Überzeugungen angehender Lehrkräfte zu sprachlich-kultureller Heterogenität in Schule und Unterricht [the empirical analysis of a “messy construct”: pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural heterogeneity in school]. Z. Erzieh. 22, 411–433. doi: 10.1007/s11618-018-0859-2

Fischer, N., Hammer, S., and Ehmke, T. (2018). “Überzeugungen zu Sprache im Fachunterricht: Erhebungsinstrument und Skalendokumentation [Beliefs about language in subject teaching: Survey instrument and scale documentation]” in Professionelle Kompetenzen angehender Lehrkräfte im Bereich Deutsch als Zweitsprache. eds. T. Ehmke, S. Hammer, A. Köker, U. Ohm, and B. Koch-Priewe (New York: Waxmann), 149–184.

Fischer, N., and Lahmann, C. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in school: an evaluation of a course concept for introducing linguistically responsive teaching. Lang. Aware. 29, 114–133. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2020.1737706

Fives, H., and Buehl, M. (2012). “Spring cleaning for the “messy” construct of teachers’ beliefs: what are they? Which have been examined? What can they tell us?” in APA educational psychology handbook. Vol. 2: Individual differences and cultural and contextual factors. eds. K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, S. Graham, J. M. Royer, and M. Zeidner (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 471–499.

Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for culturally responsive teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 53, 106–116. doi: 10.1177/0022487102053002003

Gay, G. (2010). Acting on beliefs in teacher education for cultural diversity. J. Teach. Educ. 61, 143–152. doi: 10.1177/0022487109347320

Gay, G. (2015a). Teachers’ beliefs about cultural diversity. In international handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs, Eds. H. Fives and M. G. Gill (New York: Routledge), 453–474.

Gay, G. (2015b). The what, why, and how of culturally responsive teaching: international mandates, challenges, and opportunities. Multicul. Educ. Rev. 7, 123–139. doi: 10.1080/2005615X.2015.1072079

Glock, S., and Klapproth, F. (2017). Bad boys, good girls? Implicit and explicit attitudes toward ethnic minority students among elementary and secondary school teachers. Stud. Educ. Eval. 53, 77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.04.002

Hachfeld, A., Hahn, A., Schroeder, S., Anders, Y., and Kunter, M. (2015). Should teachers be colorblind? How multicultural and egalitarian beliefs differentially relate to aspects of teachers' professional competence for teaching in diverse classrooms. Teach. Teach. Educ. 48, 44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.02.001

Hachfeld, A., Hahn, A., Schroeder, S., Anders, Y., Stanat, P., and Kunter, M. (2011). Assessing teachers’ multicultural and egalitarian beliefs: the teacher cultural beliefs scale. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 986–996. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.04.006

Hammer, S., Fischer, N., and Koch-Priewe, B. (2016). Überzeugungen von Lehramtsstudierenden zu Mehrsprachigkeit in der Schule [Pre-service teachers' beliefs regarding multilingualism in school]. DDS - Die Deutsche Schule, 13, 147–171.

Hammer, S., Viesca, K., Ehmke, T., and Heinz, B. E. (2018). Teachers’ beliefs concerning teaching multilingual learners: a cross-cultural comparison between the US and Germany. Res. Teacher Educ. 8, 6–10. doi: 10.15123/uel.88yyq

Haukås, Å. (2016). Teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism and a multilingual pedagogical approach. Int. J. Multiling. 13, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2015.1041960

Henschel, S., Heppt, B., Rjosk, C., and Weirich, S. (2022). “Zuwanderungsbezogene Disparitäten [Immigration-related disparities]” in IQB-Bildungstrend 2021. Kompetenzen in den Fächern Deutsch und Mathematik am Ende der 4. Jahrgangsstufe im dritten Ländervergleich. eds. P. Stanat, S. Schipolowski, R. Schneider, K. Sachse, S. Weirich, and S. Henschel (New York: Waxmann), 181–219.

Heppt, B., and Stanat, P. (2020). Development of academic language comprehension of German monolinguals and dual language learners. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 62:101868. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101868

Ho, D. E., Imai, K., King, G., and Stuart, E. A. (2007). Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Polit. Anal. 15, 199–236. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpl013

Hoy, A. W., Davis, H., and Pape, S. J. (2006). Teacher knowledge and beliefs. In handbook of educational psychology (pp. 715–737). US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Implication of research on teacher belief. Educ. Psychol. 27, 65–90. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep2701_6

Kalinowski, E., Egert, F., Gronostaj, A., and Vock, M. (2020). Professional development on fostering students’ academic language proficiency across the curriculum—a meta-analysis of its impact on teachers’ cognition and teaching practices. Teach. Teach. Educ. 88, 102971–102915. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.102971

Kalinowski, E., Gronostaj, A., and Vock, M. (2019). Effective professional development for teachers to foster students’ academic language proficiency across the curriculum: a systematic review. AERA Open 5, 233285841982869–233285841982823. doi: 10.1177/2332858419828691

Kennedy, M. M., Ahn, S., and Choi, J. (2008). The value added by teacher education. England: Routledge.

Kleickmann, T., and Anders, Y. (2013). “Learning at university” in Cognitive activation in the mathematics classroom and professional competence of teachers: Results from the COACTIV project. eds. M. Kunter, J. Baumert, W. Blum, U. Klusmann, S. Krauss, and M. Neubrand (US: Springer), 321–332.

Kunina-Habenicht, O., Schulze-Stocker, F., Kunter, M., Baumert, J., Leutner, D., Förster, D., et al. (2013). Die Bedeutung der Lerngelegenheiten im Lehramtsstudium und deren individuelle Nutzung für den Aufbau des bildungswissenschaftlichen Wissens [the significance of learning opportunities in teacher training courses and their individual use for the development of educational-scientific knowledge]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 59, 1–23. doi: 10.25656/01:11924

Lange, S. D., and Pohlmann-Rother, S. (2020). Überzeugungen von Grundschullehrkräften zum Umgang mit nicht-deutschen Erstsprachen im Unterricht [Beliefs of primary school teachers on dealing with non-German first languages in teaching]. Z. Bild. 10, 43–60. doi: 10.1007/s35834-020-00265-4

Levin, B. B. (2015). “The development of teachers’ beliefs” in International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs. eds. H. Fives and M. G. Gill (England: Routledge), 60–77.

Levin, B. B., He, Y., and Allen, M. H. (2013). Teacher beliefs in action: a cross-sectional, longitudinal follow-up study of teachers' personal practical theories. Teach. Educ. 48, 201–217. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2013.796029

Lorenz, E., Krulatz, A., and Torgersen, E. N. (2021). Embracing linguistic and cultural diversity in multilingual EAL classrooms: the impact of professional development on teacher beliefs and practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 105:103428. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103428

Lucas, T. (2010). “Language, schooling, and the preparation of teachers for linguistic diversity” in Teacher preparation for linguistically diverse classrooms. A resource for teacher educators. Ed. T. Lucas (England: Routledge), 3–17.

Lucas, T., and Grinberg, J. (2008). “Responding to the linguistic reality of mainstream classrooms: preparing all teachers to teach English language learners” in Handbook of research on teacher education: Enduring questions in changing contexts. eds. M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman Nemser, J. McIntyre, and J. Demmer (England: Routledge), 606–636.

Lucas, T., Villegas, A. M., and Martin, A. D. (2015). Teachers’ beliefs about English language learners. International handbook of research on teachers’ belief, Eds. H. Fives and M. G. Gill (New York: Routledge), 453–474.

Morris-Lange, S., Wagner, K., and Altinay, L. (2016). Lehrerbildung in der Einwanderungsgesellschaft: Qualifizierung für den Normalfall Vielfalt. [Teacher education in the immigration society: Qualification for the usual case of diversity]. Sachverständigenrat deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration (SVR) GmbH. Available at: https://www.svr-migration.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/SVR_FB_Lehrerbildung.pdf

OECD . (2006). Where immigrant students succeed - a comparative review of performance and engagement in PISA 2003. France: OECD.

OECD . (2019). PISA 2018 results (volume II): Where all students can succeed. France: OECD Publishing.

Olafson, L., and Schraw, G. (2006). Teachers’ beliefs and practices within and across domains. Int. J. Educ. Res. 45, 71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2006.08.005