- Department of Research and Humanities Innovation, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy

Teacher assessment literacy, generally defined as a set of knowledge and skills a teacher needs to effectively enact assessment in the classroom, has been a priority in the educational policy and educational research agenda for decades. For a long time, it has been identified with standardized measurement and classroom testing. The interest in this topic is related not only to the accountability pressures and the identification of assessment as a lever for school and system reform but also to the need for teachers to support student learning by developing and implementing responsive assessments within their classrooms. Considerable efforts have been made to prepare novice and expert teachers in understanding how to deal with aspects of assessment practice and how to use the assessment results. Although the research on teacher assessment literacy is quite wide, it continues to demonstrate how teachers struggle with assessment, especially when they are required to transfer new approaches and theories into the actual classroom context. This systematic review synthetizes the literature on teacher assessment literacy considering how it has been defined and studied over the last 10 years (2013–2022). Documenting and comparing the different expressions and definitions of assessment literacy used in the 42 selected studies, this systematic review offers a detailed overview of the changes that occurred in the conceptualizations of assessment literacy. Along with the analysis of the theoretical/conceptual frameworks and research methods used to investigate teacher assessment literacy, the scrutiny of its foundational components represents a useful base to orient pre- and in-service teacher education. Against the backdrop of strengths and weaknesses of this review, research priorities and practical implications of the findings are discussed.

1. Introduction

In educational discourses, assessment has always been one of the hottest topics (Flórez Petour, 2015; Roberts et al., 2021). The crucial trait of educational reform (e.g., Assessment Reform Group in the UK, or No Child Left Behind in the US) (Ball, 2015; OECD, 2022), assessment represented a leading force in education, advocated both as a powerful tool of educational policy and school improvement (Hilton et al., 2013; Scheerens, 2016; Torres and Weiner, 2018; Mouraz et al., 2019) and as a fundamental component of teacher instructional practice (Black and Wiliam, 2018; Allal, 2020; Yan, 2021; Brown, 2022). Given its strategic nature, assessment has been identified as a core principle underlying curriculum in many educational systems around the world, as well as a key aspect of teacher professionalism and teaching quality (O'Neill and Adams, 2014; Darling-Hammond, 2016; Cochran-Smith, 2023).

The attention deserved for teacher assessment literacy, as well as the emphasis on assessment implications for educational policy and educational practice, has bolstered the interest of policy makers, teacher educators, and researchers in preparing teachers for assessment (Popham, 2009, 2018; DeLuca et al., 2016b; Stiggins, 2017). Although a large body of literature exists, the concept of assessment literacy remains, per se, a complex and contested concept, difficult to define. Furthermore, if persistent levels of assessment illiteracy continue to be pointed out by researchers within the pre-service and in-service contexts (Beziat and Coleman, 2015; DeLuca et al., 2016a; Christoforidou and Kyriakides, 2021; Atjonen et al., 2022), then how teachers adapt their assessment practice following institutional changes or policy requirements, or inedited instructional circumstances (such as those arouse during the COVID-19 pandemic period), represents a challenging research topic.

Assuming that a unique definition of assessment literacy is not tenable, given the recognized contextual, cultural, and social nature of assessment (Willis et al., 2013), this study offers a scrutiny of the current landscape on assessment literacy and provides, through a systematic review, an overview of current knowledge about teacher assessment literacy.

Against the backdrop of teacher professionalism and teacher competency concepts, this article, in the first section, illustrates the research questions and the method employed to identify and select articles included in the analysis. In the following, instead, the results are shaped and discussed considering the study limitations, as well as the implications for educational research and educational practice.

It is important to recognize that the concept at the heart of this article, teacher assessment literacy, is not without complications and that several words in which research writes about it exist. Thus, although words such as assessment knowledge and skills, assessment competence, assessment approaches, and assessment capabilities can be found (and they have been used in performing the systematic review), over this article, the expression teacher assessment literacy has been preferred.

2. Study aims

With the purpose of mapping out how teacher assessment literacy has been studied over the last 10 years, a systematic review has been performed. Responding to the following research questions, this article aims to provide new insights useful to inform evidence-based actions in the educational research, policy, and practice fields:

• How is teacher assessment literacy defined in research and what are its foundational constructs/components?

◦ On which theories/approaches did teacher assessment literacy definitions rely on?

◦ To what extent and in what ways had teacher assessment literacy been investigated?

3. Conceptual framework

This review of teacher assessment literacy definitions sets the stage for the current efforts to map the key components in the assessment domain and supports (pre- and in-service) teachers to incorporate them into their practice.

Before proceeding with the methodology of this review, a brief reflection on what is meant by assessment literacy, within the broad framework of teacher professionalism, is offered.

For nearly more than 60 years, several studies have scrutinized what teachers should essentially know and be able to do with assessment. These studies were part of the attempts made to re-conceptualize teacher work focusing on how “teachers acquire, generate, and learn to use knowledge in teaching” (Feiman-Nemser, 2008, p. 697). The growing interest in practical knowledge, along with the recognition of the role and significance of daily experience in teacher work, led not only to revise the ideas of teacher and teaching but also to question the modalities through which teachers acquire and transfer their professionality, as well as how they mediate, adjust, and preserve their professional expertise.

Aligned with the idea that (teacher) learning is practical, redundant, spiraliform, and context-embedded (i.e., classroom, school, and national school system), the competence-based approach (Blïomeke and Kaiser, 2017; Day, 2017) deeply affected the debate on teaching quality and teaching effectiveness (O'Neill and Adams, 2014; Darling-Hammond, 2016; Torres and Weiner, 2018; Cochran-Smith, 2023). Stressing the socio-cultural perspective, Shepard pointed out that “teachers need the opportunities to construct their own understanding in the context of their practice and in ways consistent with their identity as thoughtful professionals” (Shepard, 2017, p. XXII). Professional competence is not made by a list of fixed cognitive and affective components. Assuming as an a priori, the idea of a continuum improvement, teacher competence is, instead, a complex set of “woven-together assumptions and meaning about what is important to do and be” (Shepard, 2017, p. XXII). One of the most important implications of this approach is the recognition that different levels of teacher competence and development trajectories exist (Blïomeke and Kaiser, 2017; Day, 2017; Dall'Alba, 2018; Christoforidou and Kyriakides, 2021). Teachers tend to develop their profession over time, in a complex, iterative learning process, which is influenced by pre- and in-service teacher education paths and different variables (e.g., duration, content knowledge, training models, and opportunities), as well as by on-going teaching experience and contextual factors, such as collaboration with colleagues, school participation, and professional standards. Within the specific areas of educational assessment and teacher education, the idea that teachers' continuous learning of knowledge and abilities would be linked to the improvement of classroom instructional practices (and therefore, to the increase of student learning) has been touted by teacher educators, policy makers, and educational researches as a key aspect to raise education quality (Hilton et al., 2013; Torres and Weiner, 2018). If, on the one hand, these research efforts have reduced the original vague and ambiguous definitions of assessment literacy, then, on the other hand, they have tried to ensure an effective assessment preparation for teachers. However, while teacher assessment literacy has been recognized as a key component of effective teaching and learning, research has continued to point out how teachers demonstrate low levels of assessment literacy and tend to perceive themselves as not confident in assessing student learning (DeLuca and Bellara, 2013; Poskitt, 2014; Stiggins, 2017). Different studies, in fact, have shown how, historically, assessment education received little consideration by research on initial teacher education (DeLuca, 2012). Other studies, instead, have tried to shed light on the effects of pre-service assessment education models on novice teachers (Brooks, 2021; Cochran-Smith et al., 2021). The studies and the professional development initiatives purposed to support teachers' assessment practice in their classrooms, instead, have identified more effective training models and strategies. Active, collaborative, engaging, and classroom-embedded learning models are generally recognized as more sustainable by teachers (Neuman and Cunningham, 2009). At the same time, long-term on-the-job training programs have been identified as having more influence on teachers' assessment conceptions change (Desimone, 2009). Despite the consensus that high-quality professional development could provide teachers with knowledge and skills useful to deal with innovation and challenges, some authors have pointed out that continuous development in the assessment field seems to be ineffective and time-consuming (O'Neill and Adams, 2014; Torres and Weiner, 2018). As a consequence, DeLuca et al. (2020) noticed that teachers continue to struggle with assessment practices, especially when they are required to transfer new approaches and theories into the actual classroom context. The current attempts to define teacher assessment literacy, as well as the growing research interest in teacher conceptions of assessment (Brown, 2004; Deneen and Brown, 2016), finally, offer an opportunity to better identify what counts to be an assessment literate teacher and to detect which critical features an education/training path should include (e.g., course content and pedagogies professional drivers) to effectively meet teachers' learning needs in the assessment domain.

4. The present research study

The next paragraphs describe how the systematic review has been realized; moreover, they present the main results corresponding to the research questions, which consider:

• Definitions of assessment literacy and its foundational components,

• Theories/approaches for teacher assessment literacy; and

• Research methods/methodologies used in the selected studies.

4.1. Procedure

Using the approach of Petticrew and Roberts (2006) for systematic reviews in social studies, research questions and search terms have been first defined. Then, databases have been selected and interrogated. After defining inclusion and exclusion criteria, extracted data have been categorized and summarized by theoretical/conceptual approaches to teacher assessment literacy, research aims research methods, and population and sample. Furthermore, selected studies have been evaluated in terms of scientific quality. Finally, a contrastive analysis of reviewed publications has been performed.

4.2. Search string design and databases

Although the term assessment literacy is very specific, terms such as assessment competence, assessment capability, and assessment approaches are often used synonymously in the literature and appear in a wide range of studies. Therefore, to retrieve as many relevant studies as possible, the following search string was designed:

“teacher assessment literacy*” OR “teacher assessment competence*” OR “teacher assessment approach*” OR “teacher assessment literacy capability*” NOT “higher education” NOT “university” NOT “second language” NOT “language” NOT “efl”

This research string delimited the search to compulsory education. The relationships between teacher assessment literacy and second language as a teacher subject domain were not considered. These delimitations allowed us to better situate retrieved studies within the broader context of teacher professionalism and teacher education. To identify additional sources and ensure that influential work was not overlooked, snowballing strategies, such as tracking the reference lists of included sources, and checking the researchers' outputs were also applied (Alexander, 2020; Dekkers et al., 2022). In this way, 28 additional articles were identified.

The literature search in this study was performed across 5 databases: Eric, PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science.

4.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The publications selection followed these set inclusion and exclusion criteria:

• The study was published in a scientific, international, peer-reviewed journal. To systematically pool together updated high-quality research studies, chapters in edited books, doctoral theses, conference papers, books, as well as working papers and reports were excluded. Moreover, although the inclusion of other languages allows us to consider more studies, and, as pointed out by Dekkers et al. (2022) to improve “the internal and external validity of findings in a review” (p. 205), only studies written in English were included.

• The study reported a definition of teacher assessment literacy and research work (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approach) on this topic. Given the focus of this review (i.e., provide insight into how teacher assessment literacy is defined), however, theoretical articles and reviews were also included.

• The study was realized in the context of primary or secondary education.

• The study was published in the last 10 years (2013–2022). This last criterion restricted the selection to the most recent research studies realized in the field.

In case of doubtful or not complete satisfaction with all the inclusion criteria, the publication remained in the selection. Once the title and abstract scan phase was completed, the author and two research assistants assessed the relevance of each study and discussed inclusion decisions. When a publication did not match the inclusion criteria, it was removed.

4.4. Data extraction and data analysis

The studies included in the final set were categorized and summarized using a data extraction form which consisted of the following sections:

• General information of the article (i.e., authors, title, journal, year of publication, and k-words);

• Definition of teacher assessment literacy (i.e., principal components of assessment literacy);

• Study characteristics (i.e., country, theoretical or conceptual framework, research aims/questions, and research design);

• Participant characteristics (i.e., number of participants, educational setting, and sample size).

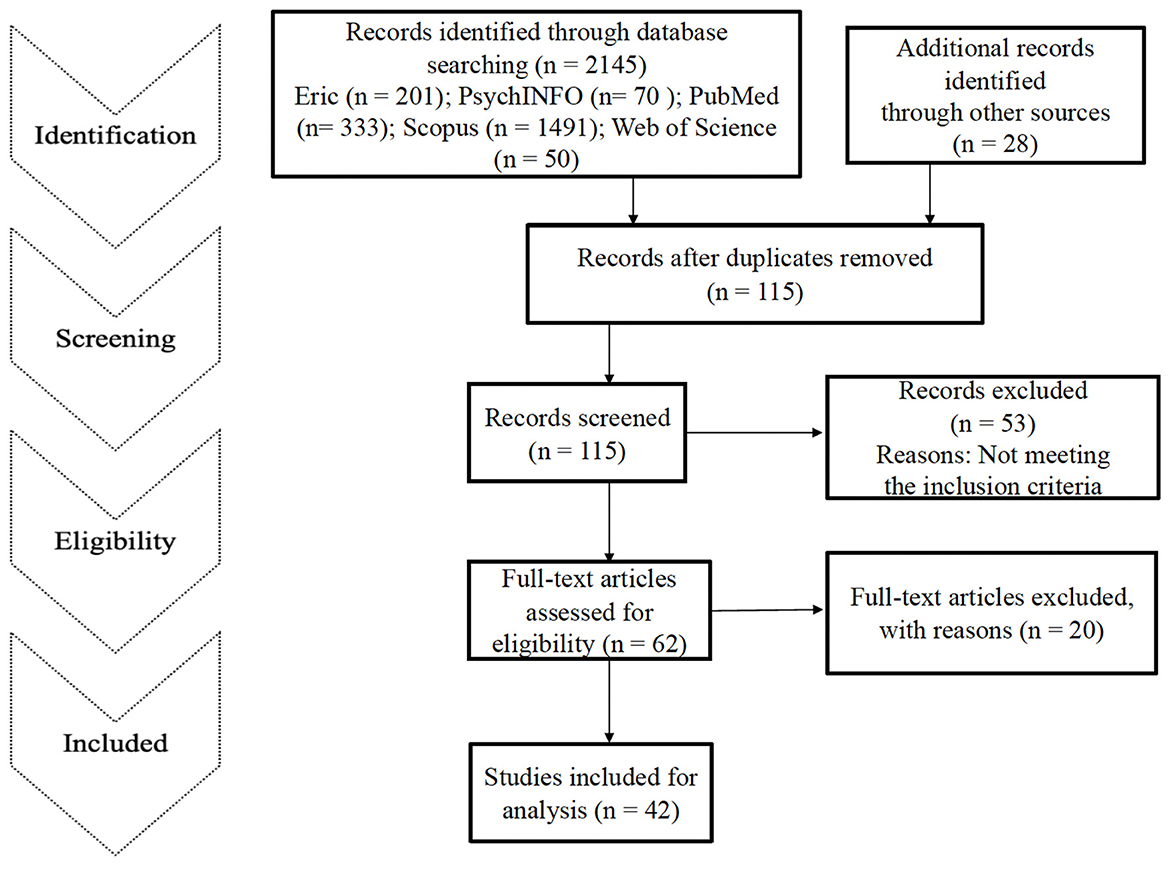

The data extraction form allowed a more effective comparison and cross-checking of data. Publications of the initial search were 2,173 (Figure 1). After removing duplicate and screening titles and abstracts, the full-text articles assessed on inclusion criteria were 115.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the search and screening process. Adapted from Moher et al. (2009).

Moreover, 53 articles were further excluded because not directly focused on teacher assessment literacy. Thus, 62 studies were included in the coding. Of these, 20 articles were excluded: 17 because without a clear definition of teacher assessment literacy and 3 because of general commentaries.

5. Results

In total, 42 studies were considered for the analysis. In the following, the study characteristics are reported (Table 1).

In the teacher assessment literacy research domain, qualitative (N = 18) and quantitative research approaches (N = 15) are more frequent than mixed-method ones (N = 9). More specifically, the qualitative research studies panel included two comparative studies (one on assessment literacy measures and another on assessment education systems) (DeLuca et al., 2019a,c), five reviews (Fulmer et al., 2015; Xu and Brown, 2016; Looney et al., 2018; Oo et al., 2022), three studies aimed to define a model of assessment literacy (Willis et al., 2013; Xu and Brown, 2016; Herppich et al., 2018; Pastore and Andrade, 2019), and two theoretical articles (Willis et al., 2013; Charteris and Dargusch, 2018). Among the review studies, two articles proposed a reconceptualization of the teacher assessment literacy construct (Xu and Brown, 2016; Looney et al., 2018).

Quantitative studies, instead, are generally purposed to examine teacher assessment literacy using standardized instruments such as questionnaires, inventories, or scales. The attempts to analyze how teachers develop assessment literacy focusing on differences between novices and experts can be traced back in time, especially in the US context where professional standards for teaching exerted a great influence on the debate on assessment literacy. The review of assessment literacy measures and the analysis of their psychometric evidence performed by Gotch and French (2014), for example, is aligned with this perspective. In their study Hailaya et al. (2014) used the Assessment Literacy Inventory (ALI) of Campbell et al. (2002). Other studies (Beziat and Coleman, 2015; Gotch and McLean, 2019), instead, used the Teacher Assessment Literacy Questionnaire (TALQ) of Plake et al. (1993). A more recent instrument linked to teacher standards (Classroom Assessment Standards, Joint Committee on Standards for Education Evaluation (JCSEE), 2015) is the Approaches to Classroom Assessment Inventory (ACAI) developed by DeLuca et al. (2016a) and used also in comparative studies (Coombs et al., 2020, 2022; DeLuca et al., 2021). A different instrument instead is offered in the study of Yan and Pastore (2022) who developed a scale focused only on teacher formative assessment literacy.

Most of the studies were conducted in English-speaking countries (e.g., the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand), while only three studies were located in the European area (Herppich et al., 2018; Christoforidou and Kyriakides, 2021; Atjonen et al., 2022).

Pre-service teacher students represent the target group more frequently investigated. In total, 11 studies are specifically focused on primary education, while 15 are on secondary education. Only five studies, instead, pondered in-service teachers and two of these studies consider both pre-service and professional development paths. Only two research studies consider, besides teacher candidates, teacher educators (Hill et al., 2014) and tutors (Akhtar et al., 2021).

The sample size, in quantitative and comparative studies, ranges from a minimum of 26 participants (Beziat and Coleman, 2015) to a maximum of 746 (Coombs et al., 2022). With the exclusion of the study of Atjonen et al. (2022) who collected data form 168 participants, generally, qualitative studies have a very reduced sample size (from 3 to 17 participants).

5.1. Teacher assessment literacy definitions

In the following, an overview of the expressions used in the selected articles to indicate teacher assessment literacy is presented. Then, a comparative and contrastive analysis of teacher assessment literacy definitions is provided. Finally, theoretical/conceptual frameworks and research methods used in the reported studies are analyzed.

There are four main expressions in the reviewed studies: teacher assessment literacy, teacher assessment competence, teacher assessment capability, and teacher assessment approaches. Only one study used the expression teacher assessment knowledge and skills (Edwards, 2017).

Teacher assessment literacy is the most frequent expression: it is used in 30 studies out of 42.

The expression teacher assessment capability, instead, is reported in five studies. A contextual element has to be highlighted in this case: with the exclusion of the comparative analysis of teacher professional standards in the article of DeLuca et al. (2016b), the studies which use the term assessment capability are generally located in Australia and New Zealand.

The expressions teacher assessment competence and teacher assessment approaches appeared in two (Herppich et al., 2018; DeLuca et al., 2019b) and four articles (DeLuca et al., 2018, 2019b, 2021; Coombs et al., 2022), respectively. All of these last articles report studies conducted using the Approaches to Classroom Assessment Inventory (ACAI).

A careful reading of teacher assessment literacy definitions shows how the identification of teacher assessment literacy with the basic principles of a sound assessment practice in the classroom, generally found in early definitions (Stiggins, 2002; Popham, 2011), is present also in more recent studies (Clark et al., 2022). Thus, while, for example, DeLuca and Bellara (2013) point out how assessment literate teachers integrate assessment practices, theories, and philosophies to support teaching and learning within a standards-based education framework, other authors (Gotch and French, 2014; Clark et al., 2022) recall, in their definitions of teacher assessment literacy, the importance of “understandings of the fundamental assessment concepts and procedures deemed likely to influence educational decisions” (Popham, 2011, p. 267). This cluster of definitions presents a very essential conceptualization of assessment literacy influenced by teacher professional standards, as well as by the attempts to measure teacher assessment literacy levels. If, on the one hand, assessment literacy is defined only in terms of knowledge and skills to be implemented by teachers in their classrooms (Kaden and Patterson, 2014; Fulmer et al., 2015; Edwards, 2017), then, on the other hand, some authors focus their attention on assessment literacy measures (Gotch and French, 2014; Hailaya et al., 2014; Kaden and Patterson, 2014; Beziat and Coleman, 2015). Teacher assessment literacy definitions in this first cluster have a clear check-list nature which is influenced by the exert of professional standards as policy mechanisms for leveraging teacher development and educational quality. The concern behind these conceptualizations is to ensure a sound assessment practice in the classroom. The identified components (e.g., construct assessment tasks, interpret, report, and communicate assessment results) are, therefore, very essential to allow teachers to enact required assessment practice.

Two phenomena, however, impressed a substantial change in this way of defining teacher assessment literacy: the widespread interest in formative assessment and the recognition of the socio-cultural nature of assessment practice. The change reported in Willis et al.'s, study where assessment literacy is defined as a “dynamic context-dependent social practice that involves teachers articulating and negotiating classroom and cultural knowledges with one another and with learners, in the initiation, development and practice of assessment to achieve the learning goals of students” (Willis et al., 2013, p. 242). Over the years, it is possible to detect the impact of this definition on the studies published after 2013. Within the articles of the present review, for example, Wills et al.'s definition of assessment literacy not only is reported in the theoretical/conceptual framework by the majority of the articles but six studies used this definition (Poskitt, 2014; Coombs et al., 2018; DeLuca et al., 2019a; Schneider et al., 2020; Clark et al., 2022; Ye, 2022). However, also the change impressed by the assessment for learning perspective in teacher assessment literacy conceptualization is evident. In their attempt to develop an instrument reflective of contemporary assessment practices and contexts (i.e., the JCSEE Classroom Assessment Standards of 2015), for example, DeLuca et al. (2016a) consider assessment literacy as “the skills and knowledge teachers require to measure and support student learning through assessment” (p. 248). Other authors, such as Looney et al. (2018), Adie et al. (2020), and Oo et al. (2022), instead, have stressed, in their definitions of assessment literacy, the use of assessment to support student learning. In this vein, it is interesting to note that three studies focused on specific assessment practices. While Edwards (2017) developed an analytic rubric for summative assessment literacy and Rogers et al. (2022) investigate the key aspect of formative assessment literacy, Yan and Pastore (2022) designed and validated a self-reported scale to assess teacher formative assessment literacy.

Since the publication of Willis et al.'s, study, more articulated and sophisticated definitions with different components have been created.

The first attempt, in this perspective, is represented by the study of Xu and Brown (2016) who provide a reconceptualization of teacher assessment literacy. Merging the research fields of education assessment and teacher education, these authors conceive assessment literacy as a combination of “cognitive traits, affective and belief systems, and socio-cultural and institutional influences” (p. 155) With an emphasis on assessment practice, the Teacher Assessment Literacy in Practice (TALIP) framework, which has a hierarchical structure and a cyclical nature, is functional to teacher learning progression in the educational assessment domain. The TALIP model has been found in the other three articles of the present review. These studies have in common the same aim: explore teacher assessment literacy development. More specifically, Gotch and McLean (2019) used the TALIP framework to examine the outcomes of a state education agency-sponsored teacher development initiative in the US. Doyle et al. (2021), instead, resorted to this model to reconsider the teacher's identity as an assessor; Atjonen et al. (2022), finally, used it to analyze Finnish student teachers' assessment literacy progression.

Among the new assessment literacy conceptualization attempts, there is the study provided by Looney et al. (2018). These authors affirm the need to investigate teacher identity as an assessor, as well as the role of conceptions, beliefs, experiences, and feelings to better understand assessment practices. As pointed out by Xu and Brown (2016), the focus on teachers' perspectives on values leads to questioning teacher assessment practice through the lenses of teacher identity and agency.

Aligned with the last two attempts to define teacher assessment literacy, the model of Pastore and Andrade (2019) emphasizes, instead, the socio-contextual, cultural, relational, and emotional dimensions of assessment practice. More specifically, assuming a holistic and adaptative competence perspective, this model has not a hierarchical structure. Its three-dimensional architecture (conceptual, practical, and socio-emotional assessment dimensions) is connected with local contextual factors, including teachers' professional wisdom and practice, and school and classroom contexts.

These last conceptualizations of assessment literacy have in common the attempts to balance very different aspects and components. Personal and professional identity, agency, and therefore aspects such as conceptions, values, beliefs, and ethical and moral responsibilities are all recognized as relevant for teachers who are called to develop new assessment repertories and practices in the classroom as a consequence of policy and social changes.

The more recent definitions of teacher assessment literacy are similar, especially in their components, to the definition of assessment competence reported in the study by DeLuca et al. (2020). Recognizing the socio-cultural nature of assessment, this competence corresponds to “knowledge, beliefs, and practices as situated within teaching and learning contexts and as influenced by multiple factors, including policy requirements, teacher professional development, learning environment and teacher-student negotiations” (p. 27). A slightly different perspective, instead, is offered by Herppich et al. (2018) who developed a very detailed analytical conceptualization of teacher assessment competence. Within teacher professional competencies, the assessment one is defined as a “measurable cognitive disposition that is acquired by dealing with assessment demands in relevant educational situations and that enables teachers to master these demands quantifiably in a range of similar situations in a relatively stable and relatively consistent way” (p. 185).

Teacher assessment capability definitions (Gunn and Gilmore, 2014; Hill et al., 2014) tend to emphasize the assessment from a learning perspective, as well as the role of student involvement and motivation. The notion of assessment capability, recalling the work of Absolum et al. (2009), includes the “ability to develop assessment that transform learning goals into assessment activities that accurately reflect student understand and achievement” (p. 9). Among these definitions, Cowie et al. (2014) also consider the teacher's ability to interpret assessment results and use these data to adjust and adapt instruction to student learning needs. In a very similar way, DeLuca et al. (2019c), recalling Bernstein's theory, point out how an assessment capable teacher makes a professional judgment based on learning and assessment theories and experiences. All these elements are functional to support teachers in designing, interpreting, and using assessment evidence in the service of student learning.

The ultimate expression found in this literature review is teacher assessment approaches. The first definition of teacher assessment approaches provided by DeLuca et al., in 2018 tends to largely overlap with the assessment capability definitions, as well as with the assessment literacy definitions provided by Xu and Brown (2016) and Looney et al. (2018). First of all, assessment approaches are referred only to the classroom context. Second, the approaches to assessment are influenced by different factors such as “experiences with assessment (as students and teachers), their values and beliefs on what constitutes valid and useful evidence of student learning, their knowledge of assessment theory, and the prevalence of systemic assessment policies” (DeLuca et al., 2018, p. 367). In a more recent definition provided by Coombs et al. (2022), instead, an interesting element is added: teacher assessment approaches, (should) represent a glimmer of how teachers conceive and practice assessment against the backdrop of educational reforms which generally tend to reframe assessment practices.

5.2. Teacher assessment literacy components

The first and more conspicuous cluster of definitions of assessment literacy (N = 16) felt the effects of the professional standards perspective. Following Stiggins (1991) and Popham (1991), and a practical-oriented view, these definitions are focused on very essential aspects:

• Assessment design, construction, administration, and scoring;

• Interpretation and use of assessment results in support of instructional decision-making, as well as of student learning;

• Reporting and communicating assessment results.

The required set of knowledge and skills allows teachers to ensure a sound classroom assessment practice. It is interesting to note how the majority of these conceptualizations (Gotch and French, 2014; Kaden and Patterson, 2014; Deneen and Brown, 2016; DeLuca et al., 2016a,b; Edwards, 2017; Akhtar et al., 2021; Clark et al., 2022; Oo et al., 2022; Rogers et al., 2022) regard pre-service and novice teachers, and the efforts made in terms of initial teacher education to support teachers reaching a “professional requirement” (DeLuca et al., 2016b).

A different panorama emerges, instead, when the focus is on the second cluster which groups the farther conceptualizations of teacher assessment literacy.

Conversely, in previous conceptualizations, the definition of Willis et al. (2013) seems more nuanced. Although the list of essential knowledge and skills is not reported, the importance of initiation, development, and practice of assessment is pointed out by the authors. Stressing the socio-cultural and contextual nature of assessment, this definition highlights the importance of teachers' negotiation and mediation in the assessment process.

Moving from a clear recognition of the socio-cultural perspective addressed by Willis et al. (2013), in their definition of assessment literacy, Xu and Brown propose a hierarchical structure that balances the inclusion of “hard” and “soft” assessment components:

• A wide teacher knowledge base;

• Institutional and socio-cultural contexts;

• Teacher literature in practice;

• Teaching and learning;

• Teacher identity (re)construction;

This model has without doubt the merit of providing a detailed picture of assessment literacy components that act at different levels in the construction of teacher professional identity; a perspective that has been stressed by Looney et al.'s (2018) model of teacher assessor identity. Moreover, in this case, the foundational components, which, traditionally, defined assessment literacy (in terms of knowledge and skills), represent the base of an effective assessment practice. However, these aspects seem not sufficient to describe a competent practice. The emphasis on the assessor's identity catalyzes what was just pointed out by Willis et al.: assessment is a social context-dependent practice and it is expected that an assessment literate teacher knows how to differentiate and calibrate this practice in response to different situations and circumstances. The awareness of teaching as an evolving profession(alism) is the key to understanding these last conceptualizations of assessment literacy.

The model provided by Pastore and Andrade (2019), among the last definitions of assessment literacy, is aligned with this perspective. However, in this case, assessment literacy is conceived not in a hierarchical, bottom-up view, but as a nested interplay of components (i.e., knowledge, skills, and dispositions), grouped in three dimensions. The inner adaptative structure of this model allows teachers to be responsive to different educational contexts and to learn or refine/review knowledge, skills, and disposition that can emerge over time in response to institutional reforms or instructional innovations.

It is clear how the models of this second cluster assume that assessment literacy has an inner core that includes the fundamental knowledge and skills necessary to ensure a sound assessment. However, although necessary, these components are not sufficient to competently enact assessment. Other components are also relevant, such as teachers' dispositions, beliefs, conceptions, and values. Furthermore, these last definitions of assessment literacy tend to identify as fundamental components the same aspects reported in the assessment competence definitions (Herppich et al., 2018; DeLuca et al., 2020).

Assuming that an assessment-competent teacher should master different assessment situations, Herppich et al. (2018) design their model matching assessment process and product perspectives. More specifically, the authors here emphasize the role of the assessment process. This process can be performed by teachers systematically or not, and can be differentiated considering aspects such as teacher assessment aims, teacher assessment activities planning, and teacher assessment-based decision-making. Although a strong similarity appears between this model and Mandinach and Gummer's (2016) model of data literacy, the authors, echoing the work of Xu and Brown (2016) recognize the role of dispositions which are differentiated in cognitive dispositions (e.g., content knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge, teaching and learning knowledge, etc.) and other dispositions (e.g., beliefs, subjective theories, and self-concepts).

An analogous picture emerges with the definitions of teacher assessment capabilities. Within this cluster, Charteris and Dargusch (2018) point out the importance of teacher awareness and skills in assessment practice; Hill et al. (2014) and DeLuca et al. (2019c), instead, provide a definition which in part inherits the components of traditional assessment literacy definitions (e.g., assessment design, interpretation, and use of assessment evidence), and reproposes, following the Bernstein's theory, the importance of teacher professional judgment, the role of teacher agency, as well as the student motivation and engagement.

The last cluster includes the assessment approaches definitions. If, on the one hand, knowledge and skills continue to be considered relevant to ensure an effective assessment practice in the classroom, then, on the other hand, as reported also in other expressions or definitions (Xu and Brown, 2016; Looney et al., 2018; Pastore and Andrade, 2019), factors such as values, beliefs, conceptions, and previous assessment experiences are recognized as shaping factors of assessment practice and teacher assessor identity.

5.3. Teacher assessment literacy theoretical/conceptual frameworks

The analysis of theoretical/conceptual approaches used to frame teacher assessment literacy reveals a composite and somewhat scattered scenario (Table 2). Although the socio-cultural perspective is constantly reported in the selected studies to stress the recognition of the socio-cultural nature of assessment, the Bernstein's socio-cultural theory is used to justify only four studies. Among these, only one is empirical research; the others, instead, include the theoretical attempt of Willis et al. to conceptualize assessment literacy, the systematic review provided by Xu and Brown (2016) as a step function to design their model of assessment literacy, and the comparative study of DeLuca et al. (2019c) on vertical and horizontal dimensions of assessment education systems. Interpreting assessment through semiotic categories, Willis et al. (2013) posed assessment literacy within the socio-cultural learning perspective and pointed out the complex nature of assessment. Depicted as an ethical practice, assessment is influenced by social, cultural, and dynamic variables. Accordingly, learning in the assessment domain is a complex process. In this vein, vertical structures which are fixed in official, schooled, formalized, and hierarchical learning are paralleled by the recognition of the importance of horizontal structures which, instead, indicate the context-dependent, tacit, experiential learning. The effects of this perspective on teacher assessment education have been remarkable because the traditional idea of preparing teachers to ensure sound assessments is replaced with the recognition of the situated nature of assessment and the representation of this practice as a critical process of inquiry performed by teachers. Thus, Willis et al. expanded what is meant by assessment literacy and laid the foundations of a new, complex, conceptualization of assessment literacy. Overcoming assessment knowledge and skills, the development of assessment literate teachers is linked to the professional wisdom of teachers, as well as to their values, conceptions, and their ethical and moral responsibilities. The impact of the socio-cultural approach becomes particularly evident in the studies which have investigated the role of teacher conceptions, values, beliefs (Gunn and Gilmore, 2014; Deneen and Brown, 2016), teacher agency (Clark, 2015), and teacher identity (Looney et al., 2018; Doyle et al., 2021). More specifically, the widespread interest in teacher assessment conceptions (Brown, 2004; Deneen and Brown, 2016) can be justified because conceptions represent, since ever in educational research, a crucial and powerful access to the modalities (how) and purposes (why) of teachers' practices. The attempts to identify teacher assessment conceptions have been relevant in understanding the dynamics involved in the implementation of educational policies.

A discrete number of studies move within the initial teacher education framework. Other studies, instead, rely on teacher professional standards as conceptual framework. However, all these studies have had a somewhat light impact on the conceptualizations or definitions of teacher assessment literacy. Indeed, the focus on initial teacher education programs and teacher professional standards led to exploring the extent to which teacher education in the assessment domain is aligned with policy expectations/requirements. Therefore, these studies although relevant in examining drivers and challenges in preparing “assessment-ready” teachers tend to reduplicate a practical view of assessment literacy. Furthermore, these studies, generally, are very close to studies framed within the perspective of teacher assessment inventories/instruments.

The teacher competence approach is recalled only in two studies: the first one, rooted in the analytical perspective (Herppich et al., 2018), assumes that individual elements of competence may be developed and improved by external intervention (Rotthoff et al., 2021). The second one (Pastore and Andrade, 2019), instead of assuming a holistic perspective on assessment literacy, considers it as linked with other competencies and makes reference to complex real-life situations. The teacher competence approach, both in the analytic and holistic versions, is very close to the socio-cultural perspective. Not surprisingly, the same aspects (e.g., personal and contextual variables, and the role of negotiation and mediation) are considered relevant in the development of teacher assessment literacy.

Two interesting perspectives are offered by the literature review of Fulmer et al. (2015) who used Kozma's model as a conceptual framework to address the different contextual factors (at micro, meso, and macro level) that can influence teacher assessment literacy and classroom assessment practice, and by the study of Charteris and Dargusch (2018) who deploy the use of practice theory to investigate how, and to what extent, schooling settings affect teacher assessment capability development. More specifically, Kozma's framework, in the study of Fulmer et al., is used to investigate the relationships among teachers' views, knowledge, and practices to identify how to support teachers in developing assessment practices. The emphasis on contextual factors in this model tends to overlap with the socio-cultural perspective and its emphasis on teachers' values, conceptions, and knowledge. Kozma's notion of different levels of influence on practice evokes, in fact, the vertical and horizontal structures identified by Willis et al. as operating in the assessment domain. Recalling the importance of teacher identity as an assessor and the role of contexts in assessment capability development, Charteris and Dargush reflect on the schooling practice architectures in terms of cultural-discursive, material-economic, and socio-political arrangements. With a focus on initial teacher education programs, the authors refer to the concept of assessment capability as a concept directly influenced by teacher agency and identity. The development of the assessment capability is, therefore, deeply rooted in real contexts and encompasses social processes of mediation, interaction, and cultural negotiation. The stress on these aspects, however, is not new compared to the perspective of Willis et al.

Some studies ground on the new conceptualizations of assessment literacy. The study of Gotch and McLean, for example, merges the TALIP framework (Xu and Brown, 2016) with the perspective of a comprehensive assessment system developed by Herman's (2016) and investigates the role of summative and interim assessment practice. In their study, Yan and Pastore (2022), instead, on the backdrop of formative assessment literature, used the Pastore and Andrade (2019) three-dimensional model of assessment literacy to design and validate a scale on teacher formative assessment literacy.

Some other studies, instead, proposed remarkable intersections between different conceptual frameworks. For example, Christoforidou and Kyriakides (2021) adopt a measurement framework in the educational effectiveness research to quantitatively detect the teacher assessment literacy characteristics as defined in the TALIP model of Xu and Brown (2016). Furthermore, comparing and contrasting the dynamic and the competence-based approaches, the authors try to highlight which aspects should be considered for an effective professional development path.

5.4. Teacher assessment literacy research methods

Selected articles were coded according to the category of research methods used (Table 3). The analysis confirms how considerable research efforts have been made to explain, examine, and investigate assessment literacy, rather than theorize or conceptualize this teacher professional domain. Only eight studies try to define the concept of assessment literacy or to identify which components should or not be considered. These articles, except for Poskitt's (2014) study which used a mixed-method research approach, are all qualitative in nature.

The use of qualitative methods is approximately the same as quantitative methods, and these research methods are more commonly used than mixed methods. More specifically, 10 qualitative studies try to shed light on different aspects, namely: the alignment of teacher education policy, teacher professional standards, and teachers' expectations (DeLuca and Bellara, 2013); and the effects of pre-service courses or professional standards on teachers' assessment literacy (DeLuca et al., 2016b, 2019c; Adie et al., 2020; Atjonen et al., 2022; Oo et al., 2022), teachers' conceptions (Cowie et al., 2014; Clark et al., 2022; Rogers et al., 2022), or teachers' assessment decisions (Clark, 2015). Therefore, 14 studies out of 15 quantitative studies report systematic attempts to investigate assessment literacy components; nine of these studies analyze how teachers develop their assessment approaches focusing on personal or contextual components. In the first case, variables such as teachers' mindsets about learning (DeLuca et al., 2019b), the career stage (Coombs et al., 2018), or the personality of pre-service teachers (Schneider et al., 2020) can be recalled. In other studies, the focus is on contextual factors such as the influence of educational policy and educational cultures/systems (DeLuca et al., 2018, 2020, 2021). Only 2 studies examine the impact of teacher education on assessment literacy (Gotch and McLean, 2019; Christoforidou and Kyriakides, 2021); while two studies explore the efficacy of education systems on professional programs designed to prepare assessment literate teachers (Hailaya et al., 2014; Beziat and Coleman, 2015).

It is important to note that studies with a quantitative or mixed-method approach tend to use standardized or structured instruments for data collection (e.g., questionnaires, inventories, and scales). The latent assumption is that research performed with this kind of data collection method can be more credible or scientific than observational, qualitative research has to be pointed out. However, a likely explanation could be also related to the traditional modality that has been used to investigate teacher assessment literacy (e.g., inventories and scales to measure and compare teachers' assessment literacy levels). While Gotch and French (2014) offer a review of past available assessment literacy measures, over the 10 years considered in the present review, only three new instruments have been developed. The ACAI instrument (DeLuca et al., 2016a), widely used also in cross-countries studies, offers a very refined standardized measure of assessment literacy. However, this assessment literacy concept is derived from policy documents and maintains a strong connection with professional standards in the classroom. The scale developed for teacher formative assessment literacy (Yan and Pastore, 2022), instead, has a theory-driven nature (formative assessment and teacher assessment literacy). Edwards (2017), finally, combining deductive observations from the literature and inductive observations based on findings from a case study, developed an analytical rubric of summative assessment literacy. This instrument is purposed to support preservice teachers with summative assessment practice.

Document analysis and secondary data analysis are reported in qualitative studies (including systematic review studies). Generally, these kinds of data collection methods are used also when the research focus is on policy documents (i.e., professional teacher standards). The other instruments used in qualitative studies are interviews, observations, and focus groups, respectively.

The analysis of research and data collection methods shows more clearly the prevalence of descriptive studies on teacher assessment literacy.

6. Discussion

The interest in preparing teachers to effectively practice assessment can be traced back to the years when the first definition attempts were mostly (even not exclusively) focused on practical issues/aspects (knowledge and skills necessary to test and evaluate student performance in the class). Not surprisingly, for Roeder (1972), assessment literacy corresponded to the proper use of evaluation techniques by teachers. Originally limited to measurement and testing practice (Gullickson and Hopkins, 1987), assessment literacy has been provocatively recalled by Stiggins (1991) and Popham (1991) as a crucial element to restrain the US educational crisis, and for a long period, this concept meant to be familiar with and knowledgeable about assessment.

The pressure exerted, first, by the global assessment policy environment and the associated discourses of accountability, and then, by the rapid diffusion of the assessment for learning agenda led to deem assessment literacy as a priority for teacher practice and teacher education. Therefore, what a teacher is expected to know and practice in terms of assessment begins to be more and more complex and demanding. The term assessment literacy, first limited to the assessment fundamentals, has progressively overlapped with the competency concept as a set of knowledge, skills, and dispositions germane to teacher assessment practice.

The widespread diffusion of the socio-cultural perspective (Willis et al., 2013), along with the practice turn (Schatzki et al., 2001; Kemmis et al., 2016) and the recognition of the context relevance in the development of teacher professionalism have impressed a substantial acceleration in this re-semantic process. As the contrastive analysis showed, assessment literacy and assessment competence are now used as synonymous. Furthermore, the emphasis added by the socio-cultural approach on aspects, such as the personal identity of teachers as assessors, and the role of beliefs, values, and conceptions led to more sophisticated working definitions of teacher assessment literacy. The teacher assessment approaches expression which incorporates the essence of assessment literacy and competence definitions stressed this perspective indicating the plural modalities through which teachers can interpret and enact assessment.

While teacher assessment literacy, competence, and approaches have a similar meaning and tend, especially considering the more recent definitions, to include the same foundational components, a discourse a part has to be made for the expression of teacher assessment capability. While some authors (Gunn and Gilmore, 2014; Hill et al., 2014) define assessment capability as a set of skills and understandings a teacher needs to support student learning, it is not clear if, and to what extent, the capability approach of Sen (1989) influenced this conceptualization.

The change in the assessment literacy conceptualizations and the identification of its foundational components offers an opportunity to ascertain what counts for teachers to be competent in the assessment domain. Conversely, to past definitions, the focus on teachers' conceptions demonstrates how, among the different theoretical and conceptual approaches identified in this review, the socio-cultural perspective really impressed a considerable shift in the assessment domain.

Drawing upon the socio-cultural perspective, assessment literacy is understood as socially distributed, context-dependent, and embedded in cultural artifacts, objects, and people (e.g., professional standards, school organization, students, and colleagues). Over the past years, research studies have, in a redundant way, pointed out the assessment illiteracy of teachers (both pre-and in-service) and called for improvement of teacher preparation to practice assessment. The new conceptualizations of assessment literacy, far from a check-list approach sometimes flattened against professional standards, instead, reinforce the idea of a dynamic connection between the vertical and the horizontal domains of assessment literacy and question how to investigate these aspects and their impact on the development of teacher assessment competence (Figure 2).

The detection of critical features on education/training paths, in this vein, should include institutional and social expectations (i.e., in professional standards), or teachers' professional learning needs in the assessment domain. Therefore, the great challenge for research in this field is to provide a better understanding of how teachers incorporate new ideas into their practice, how they transfer their learning into classrooms, and how pedagogies and mediating artifacts effectively drive teachers to become assessment literate.

7. Limitations

The findings of this review must be interpreted in light of the study's limitations. The first limitation pertains to the study's inclusion. Certainly, the choice to not include books, book chapters, dissertations, or other published works apart from peer-reviewed articles influenced the present findings. The search process constrained to education research journals led to omitting quality works such as, for example, the reviews provided by Barnes et al. (2015) and Bonner (2016). These well-designed studies, although captured in handbooks, overviewed the research on teachers' beliefs and conceptions about assessment and represent authoritative works in informing policy, pedagogy, and practice in teacher assessment literacy. As a threat to the viability of the present systematic review, this limitation has to be pointed out. Furthermore, only English language peer-reviewed articles were included because it was viewed as having scientific quality and rigor. Future research work should consider this other kinds of studies and other sources across languages to reduce publication bias and offer a more comprehensive understanding of teacher assessment literacy conceptualizations. Although the inclusion and exclusion criteria have been useful in the selecting literature phase, the lack of quality overview represents a further limitation. The exclusion of studies focused on the relationships between teacher assessment literacy and teacher subject domain (including English as a second language) has also to be mentioned. If, on the one hand, this limitation has been helpful in the identification of studies within the broader context of teacher professionalism and teacher education, then, on the other hand, understanding how subject-matter instruction and assessment education are related to each other and how they affect the development of teacher assessment literacy could represent a future research stream.

8. Conclusion

This review demonstrates that the theoretical shift impressed, since 2013, by the socio-cultural perspective has deeply affected how teacher assessment literacy is conceived. The recognition of personal, social, contextual, and cultural features shows how the assessment competence has a highly complex nature. Furthermore, this study highlights a de facto overlap between the assessment literacy and assessment competence definitions. While the growing attention deserved on teachers' conceptions seems to explain the use of the assessment approaches expression, the assessment capability appears more focused on a pedagogical version of formative assessment. Compared to other expressions, teacher assessment capability seems to not capture the complexity of current perspectives on assessment, although it recognizes the importance of cultural, social, political, and material factors in the development of teachers' identity as assessors.

The topic diversity in articles selected in this review remains stable over time, although it is possible to identify a clear trend toward specializations. The identification of what means to be an assessment literate teacher is the common core theme that is linked to different research attempts oriented to explore how to measure this competence, how to promote it in pre- and in-service education paths, and how to manage different variables which could affect teacher learning in the assessment domain.

The current recognition of the importance of teacher assessment approaches has relevant implications in terms of educational research in both pre- and in-service contexts. Understanding how teachers deal with micro (classroom level), meso (school level), and macro (national school system) assessment situations is fundamental to ensure the design and implementation of more responsive assessment education paths. A caution, however, has to be addressed here. A strong interest in assessment conceptions, values, beliefs, risks to generate tunnel visions. An over-attention of teachers' values, beliefs, and conceptions should not replace the need for investigation on assessment education (e.g., teacher education contents, pedagogies, and professional learning drivers).

With a meaningful and powerful cross-fertilization in mind, a call for inter-sectional research between the two broad areas of teacher education and educational assessment is, in conclusion, launched. In this way, it would be possible to reduce the gap between vertical and horizontal components of teacher learning in the assessment domain bridging what teachers learn in public and formal contexts and what they need to practice assessment in daily school life. This review presents a map of the research field on teacher assessment literacy and shows how some themes become central while other themes first dominating the debate (e.g., the attempts to measure assessment literacy) become more peripherical. Overcoming descriptive questions regarding how assessment literacy can be promoted in practice, further research is necessary to determine the extent to which the components enumerated in current definitions adequately reflect a common idea of an assessment literate teacher. The debate flux, furthermore, calls also for different research attempts (especially in terms of research design). Few large-scale or cross-cultural comparative studies have been found in this review. Additional future studies would benefit from longitudinal studies to track the transfer of teacher learning about assessment to actual classroom practice. Finally, the need for a connection between different research clusters (e.g., pre- and in-service teacher education; personal and contextual factors, assessment pedagogies and curriculum; teacher assessment literacy measurement instruments and assessment literacy professional drivers; etc.) is also advocated to reinforce the development of an integrated and established teacher assessment literacy field of research.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Absolum, M., Flockton, L., Hale, J., Hipkins, R., and Reid, I. (2009). Directions for Assessment in New Zealand: Developing Students' Assessment Capabilities. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

*Adie, L., Stobart, G., and Cumming, J. (2020). The construction of the teacher as expert assessor. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 48, 436–453. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2019.1633623

*Akhtar, Z., Hussain, S., and Ahmad, N. (2021). Assessment literacy of prospective teachers in distance mode of education: a case study of Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad. J. Educ. Educ. Dev. 8, 218–234. doi: 10.22555/joeed.v8i1.114

Alexander, P. A. (2020). Methodological guidance paper: the art and science of quality systematic reviews. Rev. Educ. Res. 90, 6–23. doi: 10.3102/0034654319854352

Allal, L. (2020). Assessment and the co-regulation of learning in the classroom. Assess. Educ. Principl. Policy Pract. 27, 332–349. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2019.1609411

Alonzo, D., Labad, V., Bejano, J., and Guerra, F. (2021). The Policy-driven dimensions of teacher beliefs about assessment. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 46, 36–51. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2021v46n3.3

*Atjonen, P., Pöntinen, S., Kontkanen, S., and Ruotsalainen, P. (2022). In enhancing preservice teachers' assessment literacy: focus on knowledge base, conceptions of assessment, and teacher learning. Front. Educ. 7, 891391. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.891391

Ball, S. (2015). Education, governance and the tyranny of numbers. J. Educ. Policy 30, 299–301. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2015.1013271

Barnes, N., Fives, H., and Dacey, C. M. (2015). “Teachers' beliefs about assessment,” in International Handbook of Research on Teacher Beliefs, eds H. Fives, and M. Gregoire Gill (New York, NY: Routledge), 284–300.

*Barnes, N., Gareis, C., DeLuca, C., Coombs, A., and Uchiyama, K. (2020). Exploring the roles of coursework and field experience in teacher candidates' assessment literacy: a focus on approaches to assessment. Assess. Matters 14, 5–41. doi: 10.18296/am.0045

*Beziat, T. L. R., and Coleman, B. K. (2015). Classroom assessment literacy: evaluating pre-service teachers. Researcher 27, 25–30.

Biesta, G., and Tedder, M. (2006). How is Agency Possible? Towards An Ecological Understanding of Agency-As-Achievement, Working Paper 5. Exeter: The Learning Lives Project.

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (2018). Classroom assessment and pedagogy. Assess. Educ. Princip. Policy Pract. 25, 551–575. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2018.1441807

Blïomeke, S., and Kaiser, G. (2017). “Understanding the development of teachers' professional competencies as personally, situationally and socially determined,” in The SAGE Handbook of Research on Teacher Education, eds D. J. Clandinin, and J. Husu (London: SAGE Publications), 783–802.

Bonner, S. M. (2016). “Teachers' perceptions about assessment: competing narratives,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment, eds G. T. L. Brown, and L. R. Harris (New York, NY: Routledge), 21–39.

Brookhart, S. M. (2011). Educational assessment knowledge and skills for teachers. Educ. Measure. Issue. Pract. 30, 3–12.

Brooks, C. (2021). The quality conundrum in initial teacher education. Teach. Teach. 27, 131–146. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2021.1933414

Brown, G. T. L. (2004). Teachers' conceptions of assessment: implications for policy and professional development. Assess. Educ. 11, 301–318. doi: 10.1080/0969594042000304609

Brown, G. T. L. (2022). The past, present and future of educational assessment: a transdisciplinary perspective. Front. Educ. 7,1060633. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1060633

Campbell, C., Murphy, J. A., and Holt, J. K. (2002). “Psychometric analysis of an assessment literacy instrument: Applicability to preservice teachers,” in Annual Meeting of the Mid-Western, Educational Research Association (Columbus, OH).

Carless, D. (2005). Prospects for the implementation of assessment for learning. Assess. Educa. Principl. Policies Pract. 12, 39–45. doi: 10.1080/0969594042000333904

*Charteris, J., and Dargusch, J. (2018). The tensions of preparing pre-service teachers to be assessment capable and profession-ready. Asia Pac. J. Teac. Educ. 46, 354–368. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2018.1469114

*Christoforidou, M., and Kyriakides, L. (2021). Developing teacher assessment skills: the impact of the dynamic approach to teacher professional development. Stud. Educ. Eval. 70, 101051. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101051

*Clark, A. K., Nash, B., and Karvonen, M. (2022). Teacher assessment literacy: implications for diagnostic assessment systems. Appl. Meas. Educ. 35, 17–32. doi: 10.1080/08957347.2022.2034823

*Clark, J. S. (2015). My assessment didn't seem real”: the influence of field experiences on preservice teachers' agency and assessment literacy. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 6, 91–111. doi: 10.17499/jsser.91829

Cochran-Smith, M. (2023). What's the “problem of teacher education in the 2020s? J. Teach. Educ. 74,1–3. doi: 10.1177/00224871231160373

Cochran-Smith, M., Keefe, E. S., and Jewett Smith, R. (2021). A study in contrasts: multiple-case perspectives on teacher preparation at new graduate schools of education. New Educ. 17, 96–118. doi: 10.1080/1547688X.2020.1822485

*Coombs, A., DeLuca, C., LaPointe-McEwan, D., and Chalas, A. (2018). Changing approaches to classroom assessment: AN empirical study across teacher career stages. Teach. Teach. Educ. 71, 131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.010

*Coombs, A., DeLuca, C., and MacGregor, S. (2020). A person-centered analysis of teacher candidates' approaches to assessment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 87, 102952. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.102952

*Coombs, A., Rickey, N., DeLuca, C., and Liu, S. (2022). Chinese teachers' approaches to classroom assessment. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 21, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10671-020-09289-z

*Cowie, B., Cooper, B., and Ussher, B. (2014). Developing an identity as a teacher-assessor: three student teacher case studies. Assess. Matters 7, 64–89. doi: 10.18296/am.0128

Dall'Alba, G. (2018). “Reframing expertise and its development: a lifeworld perspective,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance, 2nd Edn, eds K. A. Ericsson, R. R. Hoffman, A. Kozbelt, and A. M. Williams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 33–39.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Research on teaching and teacher education and its influences on policy and practice. Educ. Res. 45, 83–91. doi: 10.3102/0013189X16639597

Day, C. (2017). “Competency-based education and teacher professional development,” in Competence-Based Vocational and Professional Education, ed M. Mulder (New York, NY: Springer), 165–182.

*Dekkers, R., Carey, L., and Langhorne, P. (2022). Making Literature Reviews Work: A Multidisciplinary Guide to Systematic Approaches. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-90025-0_1

DeLuca, C. (2012). Preparing teachers for the age of accountability: toward a framework for assessment education. Action Teac. Educ. 34, 576–591. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2012.730347

*DeLuca, C., and Bellara, A. (2013). The current state of assessment education: aligning policy, standards, and teacher education curriculum. J. Teach. Educ. 64, 356–372. doi: 10.1177/0022487113488144

*DeLuca, C., Coombs, A., and LaPointe-McEwan, D. (2019b). Assessment mindset: exploring the relationship between teacher mindset and approaches to classroom assessment. Stud. Educ. Eval. 61, 159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.03.012

*DeLuca, C., Coombs, A., MacGregor, S., and Rasooli, A. (2019a). Toward a differential and situated view of assessment literacy: studying teachers' responses to classroom assessment scenarios. Front. Educ. 4, 94. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00094

*DeLuca, C., LaPointe-McEwan, D., and Luhanga, U. (2016a). Approaches to classroom assessment inventory: a new instrument to support teacher assessment literacy. Educ. Assess. 21, 248–266. doi: 10.1080/10627197.2016.1236677

*DeLuca, C., LaPointe-McEwan, D., and Luhanga, U. (2016b). Teacher assessment literacy: a review of international standards and measures. Educ. Asses. Eval. Account. 28, 51–272. doi: 10.1007/s11092-015-9233-6

*DeLuca, C., Rickey, N., and Coombs, A. (2021). Exploring assessment across cultures: teachers' approaches to assessment in the U.S., China, and Canada. Cogent. Educ. 8, 1921903. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2021.1921903

*DeLuca, C., Schneider, C., Coombs, A., Pozas, M., and Rasooli, A. (2020). A cross-cultural comparison of German and Canadian student teachers' assessment competence. Assess. Educ. Princip. Policy Pract. 27, 26–45. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2019.1703171

*DeLuca, C., Valiquette, A., Coombs, A., LaPointe-McEwan, D., and Luhanga, U. (2018). Teachers' approaches to classroom assessment: a large-scale survey. Assess. Educ. Principl. Policy Pract. 25, 355–375. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2016.1244514

*DeLuca, C., Willis, J., Harrison, C., Coombs, A., et al. (2019c). Policies, programs, and practices: exploring the complex dynamics of assessment education in teacher education across four countries. Front. Educ. 4, 132. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00132

*Deneen, C.C., and Brown, G. T. L. (2016). The impact of conceptions of assessment on assessment literacy in a teacher education program. Cogent. Educ. 31, 1225380. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1225380

Desimone, L. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers' professional development: toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educ. Res. 38, 181–199. doi: 10.3102/0013189X08331140

Dixon, H., and Haigh, M. (2009). Changing mathematics teachers' conceptions of assessment and feedback. Teach. Develop. 13, 173–186. doi: 10.1080/13664530903044002

*Doyle, A., Conroy Johnson, M., Donlon, E., McDonald, E., and Sexton, P. (2021). The role of the teacher as assessor: developing student teacher's assessment identity. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 46, 52–68. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2021v46n12.4

*Edwards, F. (2017). A rubric to track the development of secondary pre-service and novice teachers' summative assessment literacy. Assess. Educ. Princip. Policy Pract. 24, 205–227. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2016.1245651

Feiman-Nemser, S. (2008). “Teacher learning. How do teacher learn to teach?,” in Handbook of Research on Teacher Education, eds M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, and K. E. Demers (New York, NY: Routledge).

Flórez Petour, M. T. (2015). Systems, ideologies and history: a three-dimensional absence in the study of assessment reform processes. Assess. Educ. Princip. Policy Pract. 22, 3–26. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2014.943153

*Fulmer, G. W., Lee, I. C. H., and Tan, K. H. K. (2015). Multi-level model of contextual factors and teachers' assessment practices: an integrative review of research. Assess. Educ. Princip. Policy Pract. 22, 475–494. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2015.1017445

*Gotch, C. M., and French, B. F. (2014). A systematic review of assessment literacy measures. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 33, 14–18. doi: 10.1111/emip.12030

*Gotch, C. M., and McLean, C. (2019). Teacher outcomes from a statewide initiative to build assessment literacy. Stud. Educ. Eval. 62, 30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.04.003

Gullickson, A. R., and Hopkins, K. D. (1987). Perspectives on educational measurement instruction for pre-service teachers. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 6, 12–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.1987.tb00501.x

*Gunn, A. C., and Gilmore, A. (2014). Early childhood initial teacher education students' learning about assessment. Assess. Matters 7, 24–38. doi: 10.18296/am.0124

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Does it make a difference? Evaluating professional development. Educ. Leadership 5, 45–51.

*Hailaya, W., Alagumalai, S., and Ben, F. (2014). Examining the utility of assessment literacy inventory and its portability to education systems in the Asia Pacific region. Aust. J. Educ. 58, 297–317. doi: 10.1177/0004944114542984

Harrison, C. (2005). Teachers developing assessment for learning: Mapping teacher change. Teach. Develop. 9, 255–264.

Herman, J. (2016). Comprehensive Standards Based-Assessment Systems Supporting Learning. Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST).

*Herppich, S., Praetorius, A.-K., Forster, N., Glogger-Frey, I., Karst, K., Leutner, D., et al. (2018). Teachers' assessment competence: integrating knowledge-, process-, and product-oriented approaches into a competence-oriented conceptual model. Teach. Teach. Educ. 76, 181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.001

*Hill, M. F., Ell, F., Grudnoff, L., and Limbrick, L. (2014). Practise what you preach: Initial teacher education students learning about assessment. Assess. Matters 7, 90–112. doi: 10.18296/am.0126

Hilton, G., Flores, M. A., and Niklasson, L. (2013). Teacher quality, professionalism and professional development: findings from a European project. Teach. Dev. 17, 431–447. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2013.800743

Joint Committee on Standards for Education Evaluation (JCSEE). (2015). Classroom Assessment Standards: Practices for PK-12 Teachers.

*Kaden, U., and Patterson, P. P. (2014). Changing assessment practices of teaching candidates and variables that facilitate that change. Act. Teach. Educ. 36, 406–420. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2014.977700

Kemmis, S., Edwards-Groves, C., Lloyd, A., Grootenboer, P., Hardy, I., and Wilkinson, J. (2017). “Learning as being 'Stirred into practices,” in Practice Theory Perspectives on Pedagogy and Education, eds P. Grootenboer, C. Edwards-Groves, and S. Choy (Singapore: Springer), 45–65.

Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., and Edwards-Groves, C. (2016). “Roads not travelled, roads ahead: How the theory of practice architectures is travelling,” in Exploring Education and Professional Practice: Through the Lens of Practice Architectures, eds K. Mahon, and S. Francisco (Singapore: Springer), 239–256.

Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., and Bristol, L. (2014). Changing Practices, Changing Education. Singapore: Springer Science & Business Media.

Kozma, R. B. (2003). “ICT and educational change: A global phenomenon,” in Technology, Innovation, and Educational Change: A Global Perspective, ed R. B. Kozma (Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education), 1–18.

*Looney, A., Cumming, J., van Der Kleij, F., and Harris, K. (2018). Reconceptualising the role of teachers as assessors: teacher assessment identity. Assess. Educ. Princip. Policy Pract. 25, 442–467. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2016.1268090

Mandinach, E. B., and Gummer, E. S. (2016). Data Literacy for Teachers: Making it Count in Teacher Preparation and Practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press

Mertler, C. A. (2009). Teachers' assessment knowledge and their perceptions of the impact of classroom assessment professional development. Improv. Schools 12, 101–113.

Mertler, C. A., and Campbell, C. (2005). “Measuring teachers' knowledge & application of classroom assessment concepts: Development of the assessment literacy inventory”, in Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (Montreal, QC).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mouraz, A., Leite, C., and Fernandes, P. (2019). Between external influence and autonomy of schools: effects of external evaluation of schools. Paidéia 29, e2922. doi: 10.1590/1982-4327e2922

National Taskforce on Assessment Education for Teachers. (2016). Assessment Literacy Defined. Available online at: http://assessmentliteracy.org/national-task-force-assessmenteducation-teachers/

Neuman, S. B., and Cunningham, L. (2009). The impact of professional development and coaching on early language and literacy instructional practices. Am. Educ. Res. J. 46, 532–566. doi: 10.3102/0002831208328088

OECD (2022). Trends Shaping Education 2022. Paris: The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

O'Neill, J., and Adams, P. (2014). The future of teacher professionalism and professionality in teaching. New Zeal. J. Teachers Work 11, 1–2.

*Oo, C. Z., Alonzo, D., and Asih, R. (2022). Acquisition of teacher assessment literacy by pre-service teachers: a review of practices and program designs. Issues Educ. Res. 32, 352–373. Available online at: hkp://www.iier.org.au/iier32/oo.pdf

*Pastore, S., and Andrade, H. L. (2019). Teacher assessment literacy: a three-dimensional model. Teach. Teach. Educ. 84, 128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.05.003

Petticrew, M., and Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Blackwell.

Plake, B. S., Impara, J. C., and Fager, J. J. (1993). Assessment competencies of teachers: a national survey. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 12, 39. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.1993.tb00548.x

Popham, W. J. (1991). Appropriateness of teachers' test-preparation practices. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 10, 12–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.1991.tb00211.x

Popham, W. J. (2009). Assessment literacy for teachers: Faddish or fundamental? Theory Pract. 48, 4–11. doi: 10.1080/00405840802577536