- Department of Kinesiology and Health Science, Utah State University, Logan, UT, United States

The decolonization of global health is increasingly promoted as an essential process for promoting social justice, achieving health equity, and addressing structural violence as a determinant of health. Innovative curricular design for short-term, field-based experiential education activities in global settings represents an important opportunity for bringing about the types of change promoted by the movement to decolonize global health. To identify theories, frameworks, models, and assessment tools for short-term study abroad programs, we conducted a federated search using EBSCOhost on select databases (i.e., Academic Search Ultimate, Medline, CINAHL, and ERIC). A total of 13 articles were identified as relevant to curricular innovations, theories, and designs involving experiential education and learning in global settings that are consistent with the aims of decolonizing global health. The subsequent manuscript review revealed several common themes that inform planning, execution, and evaluation of global experiential education programs. Global education experiences can contribute to decolonization by seeking the interests of host communities. Recommended actions include treating local partners as equals in planning and design, providing compensation to hosts for resources and services rendered, creating opportunities for local practitioners to collaborate, interact, and share knowledge with students, and ensuring the rights of local participants are protected. Additionally, the aims of decolonization are furthered as student participants become aware of and are inspired to dismantle colonial practices. Transformational experiential learning includes engaging students with diverse communities and local knowledge, maximizing participation with local populations and community partners, and engaging in critical thinking and self-reflection culminating in intercultural competence.

1. Introduction

The prevalence of scholarly articles dealing with the ‘decolonization of global health’ has grown exponentially over the past two decades (Faerron Guzmán and Rowthorn, 2022). Calls are increasingly being made to decolonize every aspect of global health from partnerships and collaborations (Bhandal, 2018) to research (Lawrence and Hirsch, 2020; Abouzeid et al., 2022) to authority structures (Demir, 2022) to philanthropic efforts (Schwab, 2021) to medical education and missions (Garba et al., 2021; Tracey et al., 2022) to health education and promotion (Eichbaum et al., 2021) to nutrition (Calderón Farfán et al., 2021; Van Winkle, 2022) to mental health (Wessells, 2015) and beyond (Faerron Guzmán and Rowthorn, 2022). While the push for decolonizing global health is clearly based on urgent needs for a transformation in how global health is understood and pursued, there is also a need for clarity, consensus, and purpose in moving forward with decolonization in ways that are truly meaningful, impactful, sustainable, and that avoid unintended negative consequences (Abimbola and Pai, 2020; Hellowell and Schwerdtle, 2022).

The specific goal of this article is to explore efforts to design short term experiential learning programs (e.g., faculty led study abroad programs) in ways that mesh with a coherent framework, are based on sound theory, and align well with the aims of decolonizing global health (Prasad et al., 2022; Ratner et al., 2022). In doing so, we will consider input from relevant articles dealing with theory, methods, models, frameworks, and assessments related to best practices in short-term experiential education abroad, while at the same time aligning identified best practices with the aims for decolonizing public health.

1.1. Definition and aims of decolonizing global health

The Decolonizing Global Health Working Group (2021) at the University of Washington’s International Clinical Research Center has developed a Decolonizing Global Health Toolkit that begins with this definition of Decolonizing Global Health: reversing the legacy of colonialism in health equity work. The Working Group further proposes four primary aims for decolonizing global health practices meant to guide global health practitioners in a variety of fields, including global health education and promotion. As such, they have relevance for this paper and include: (1) achieve equitable collaborations, (2) center projects around local priorities, (3) diversify leadership, and (4) promote respectful, collaborative interactions and language/tone in all communications (Decolonizing Global Health Working Group, 2021).

1.2. Barriers to decolonizing global health

While pursuing these aims, it is helpful to consider barriers to decolonization that must be managed. For example, Kulesa and Brantuo (2021) identify several barriers to decolonizing global health educational partnerships including: the challenges of bringing all relevant stakeholders to the table; managing anxieties among indigenous or vulnerable peoples related to a growing sense of inequity and loss of belonging; and balancing a variety of ethical dilemmas in global health work (Kulesa and Brantuo, 2021). Resolution of these barriers requires targeted strategies, deep community immersion, and in-depth, open discussions with local partners about appropriate moral frameworks that can guide understandings and mutually acceptable resolutions to moral dilemmas.

1.3. Avoiding unintended consequences

As with all public health endeavors, taking a systems thinking approach that fully engages relevant stakeholders is an important process for designing programs and interventions that can minimize the risk of unintended consequences (De Savigny and Adam, 2009). For example, Hellowell and Schwerdtle (2022) have cautioned against three specific harms that should be avoided as the decolonization agenda moves forward, including the potential for: undermining confidence in scientific knowledge; accentuating inter-group and international antagonisms; and curtailing the opportunities for redistributive change in the future (Hellowell and Schwerdtle, 2022). Some authors even argue that if the most radical changes promoted by decolonization are realized, global health as we know and understand it may cease to exist, leaving us with the need to come up with a new name for the discipline (Abimbola and Pai, 2020).

1.4. Philosophical orientation

Philosophically, this paper is in alignment with the Freirean school of thought that education can be an empowering force for positive change, especially for the oppressed and most vulnerable. As it applies to the decolonization of global health, education can be instrumental in allowing individuals and communities to move beyond colonial legacies while gaining local control over the social determinants of health (Giroux, 2010; Freire, 2018). Adopting best practices for study abroad programs is an essential part of this process.

This paper, including our findings outlined below, are presented with the intent of avoiding the negative consequences outlined by Hellowell and Schwerdtle (2022), while at the same time identifying best practices for short-term experiential learning in global settings that are theory and evidence-based, and that align most closely with the highest aims of the decolonization movement (Eichbaum et al., 2021).

2. Methods

Research activities for this synthesis was conducted during November 2022 – April 2023. To identify relevant scholarly articles dealing with educational approaches to the decolonization of global health researchers conducted a systematic review of the literature. This review did not involve human participants, was limited to scholarly published articles written in English from January 2010 to December 2022, did not incorporate grey literature, and had to include full text.

2.1. Search strategy and eligibility criteria

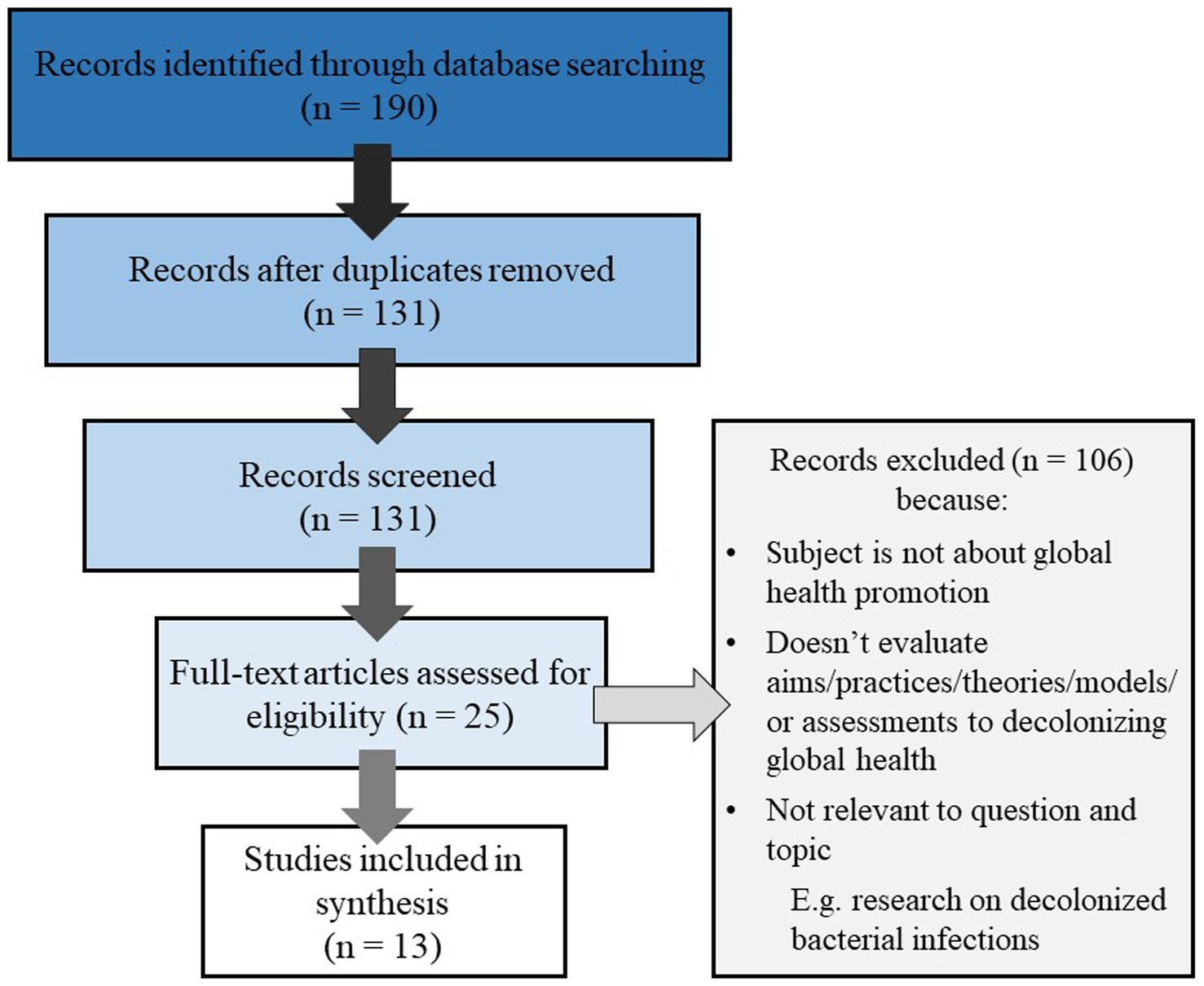

A federated search was conducted using EBSCOhost on select databases (i.e., Academic Search Ultimate, Medline, CINAHL, and ERIC). Using key search terms: ‘global health’ and ‘decolon* and (‘pedagog* or study abroad or learn* or educat* or experien*’) [where the asterisk catches variations of suffixes], 190 articles were identified. Our initial search shows that a majority of results came from Medline (n = 84) followed by Academic Search Ultimate (n = 80), CINAHL Complete (n = 20), and ERIC (n = 6). Once duplicates were removed, the remaining 131 articles were screened by all three authors for relevance to the goals of this article.

Using inclusion criteria: articles dealing with theory, models, frameworks, assessments, and best practices for conducing short-term experiential education abroad within the context of decolonizing global health, 25 articles underwent full text assessment. At the same time, 106 articles were excluded for lack of relevancy. Exclusion criteria included: subject was insufficiently relevant to global health promotion and experiential learning, research was insufficiently related to the inclusion goals outlined above, and articles were off-topic (e.g., decolonizing bacterial infections) (see Figure 1).

After careful full text review and collective analysis, a total of 13 articles were identified as relevant to curricular innovations, theories, and designs involving experiential education and learning in global settings that are consistent with the aims of decolonizing global health. The subsequent manuscript review revealed several common themes that inform planning, execution, and evaluation of global experiential education programs.

3. Results

After a review of the full text of remaining articles, thirteen were selected as being especially relevant to the goal of identifying theories, frameworks, models, best practices, and assessments for the design of short-term, field-based experiential education programs.

Three articles dealt specifically with short-term global health educational experiences (Myers and Fredrick, 2017; Wood and Jobe, 2020; Hawks, 2021), while others focused on contextual factors needed to support the development of global health study abroad experiences, such as curriculum and general global health education (Pentecost et al., 2018; Naidu, 2021; Wong et al., 2021; Ratner et al., 2022), faculty development (Behari-Leak et al., 2021; Hawks, 2021; Naidu, 2021), research practices (Keikelame and Swartz, 2019; Lawrence and Hirsch, 2020), and partner relationships (Kulesa and Brantuo, 2021; Prasad et al., 2022).

Ten articles targeted one or more specific intervention or strategy. Myers and Fredrick (2017), Wood and Jobe (2020), Hawks (2021), and Ratner et al. (2022) all applied high impact educational learning experiences to promote decolonization principles in students. Pentecost et al. (2018), Behari-Leak et al. (2021), Hawks (2021), Naidu (2021), and Prasad et al. (2022) similarly promote specific curriculum and design interventions. Lawrence and Hirsch (2020), Kulesa and Brantuo (2021), Prasad et al. (2022) further outline recommendations regarding partnerships between global health programs and host communities.

Multiple themes and patterns emerged from these targeted curricular, experiential, and program development strategies and interventions that can help guide study abroad best practices within a decolonization framework.

3.1. Themes in best practices affecting students

Transformative Learning Theory (TLT) is a common thread in all articles that proposed student focused interventions. Some authors directly referred to TLT (Wood and Jobe, 2020; Hawks, 2021), while other frameworks included very similar elements (Myers and Fredrick, 2017; Ratner et al., 2022), particularly disorienting dilemmas, critical reflection, and integration and action based on new perspectives. These steps each help students progress along the path from being unaware of colonial legacies to becoming agents of decolonization. Of note, these same concepts are deeply interwoven in the praxis of Freire and provide an underlying moral foundation for this theoretical and philosophical approach to education (Darder, 2017).

3.2. Disorienting dilemmas

Ratner et al. (2022) recognizes that true decolonial education must start with an initial realization and a grappling with real life struggles caused by colonial power. Myers and Fredrick (2017), Wood and Jobe (2020), and Hawks (2021) each posit that short-term educational experiences in a global setting can be effective settings for creating these disrupting dilemmas. “Numerous authors have conveyed the unsettling experiences felt by participants encountering international settings especially for the first times” (Wood and Jobe, 2020). Hawks (2021) comments on the effectiveness of deep engagement with diverse communities, and Myers and Fredrick (2017) attribute transformative benefits of “desirable difficulties” in learning retention.

3.3. Critical reflection

According to Hawks (2021), reflection becomes a catalyst for converting experiences into new, and hopefully transformative perspectives. It can also promote critical examination of course concepts (Hawks, 2021). Taking time to reflect allows learners to identify and confront their own biases (Ratner et al., 2022). Additionally, reflection is helpful in assessing an individual’s progress toward transformation (Wood and Jobe, 2020).

3.4. Integration and action

Transformative learning culminates as new perspectives inform action moving forward. This would translate into observable behavior that could only be completed after engaging in the project (Wood and Jobe, 2020). A learner who has reached this stage is actively seeking to dismantle colonial practices, ideally at a systemic level (Ratner et al., 2022).

3.5. Assessment tools

Wood and Jobe (2020) and Ratner et al. (2022) each propose tools for assessing students’ progress as they engage with transformational learning activities. Ratner’s tool moves learners through stages including Pre-contemplative Learner, Contemplative Reflective Learner, Critical Action Learner, and Transformative Action Learner. The first stage is a baseline, while the final stage is aspirational. Ratner notes that regardless of stage, one is never finished with transformation and an ‘end-point’ would be antithetical and possibly harmful to learners’ decolonial journey” (Ratner et al., 2022).

Wood and Jobe (2020) propose an assessment tool that takes three different competencies—Global and Cultural Competency, Leadership, and Service Learning and Civic Engagement—through three stages—Exposure, Integration, and Transformation. Exposure indicates an openness to improving one’s views, integration is using experience to advance a cause, and transformation involves using one’s leadership skills to empower others to embark on the same process. Wood and Jobe (2020) point out that short term study abroad experiences may not be sufficient to move students through all three stages, however they can be an important element in this journey.

Myers and Fredrick (2017) describe a program that seeks to address the shortcomings short-term study abroad programs may have compared to longer courses of study in a global setting by engaging students in a four-year, longitudinal global medical program. This course follows the transformative learning pattern by creating a disturbing dilemma during a first-year, short-term study abroad experience, guiding reflection during years two and three, and culminating in a second trip to the same community during the fourth year that integrates learning into clinical experience.

3.6. Themes related to curriculum and program design for study abroad experiences

As program planners design study abroad experiences with an aim toward decolonization, the best practices in the literature fall into themes of (1) challenging knowledge hierarchies, (2) self-awareness and cultural humility, and (3) understanding of the larger systemic, historical, and sociopolitical global health landscape (Pentecost et al., 2018; Kulesa and Brantuo, 2021; Skopec et al., 2021). Wong points out the need to move from biomedical hegemony to epistemic plurality (Wong et al., 2021). Decolonization demands that curricular design question the “structured, standardized, compartmentalized” approach to medical and health education, as well as the assumption that this approach is superior in efficiency and measurability (Naidu, 2021). Additionally, to both meet the aims of decolonization and further the progress of innovation, an appreciation of traditional and indigenous practice and ways of knowing is necessary (Naidu, 2021).

As Ratner points out, even the most advanced and experienced practitioners and educators may be novices when it comes to decoloniality (2022), highlighting the need for critical reflection, self-awareness, and cultural humility (Wong et al., 2021). This includes awareness of the knowledge and value systems in which one is formed and embedded (Pentecost et al., 2018). Authors emphasize the distinction between cultural competence and their chosen phrases such as critical reflection (Wong et al., 2021), critical consciousness (Keikelame and Swartz, 2019), and critical awareness (Naidu, 2021). Because culture changes one cannot be simply competent, but also must possess the humility to be adaptable to changing times and contexts as one continues to learn (Keikelame and Swartz, 2019). Behari-Leak et al. (2021) encourage changing the teacher-student power structure as a tool of decolonization through vulnerability, making the teacher and students co-learners, and drawing on the principles of Transformative Learning Theory, give both parties disrupting dilemmas to spur transformation.

Finally, multiple authors argue that an understanding of the history and legacy of colonialism in global health and medicine is essential to global health education. Additionally, current social and political factors must be acknowledged, taught alongside and integrated into the global health curriculum (Eichbaum, 2017; Pentecost et al., 2018; Behari-Leak et al., 2021; Naidu, 2021; Wong et al., 2021). Pentecost et al. (2018) encourage the integration of the humanities, arts, and social sciences, to promote understanding of history, center inclusion, and seek social justice.

3.7. Themes related to partner relationships in study abroad experiences

Study abroad experiences inherently involve partnerships with host nations, communities, and organizations. The colonial model inherently produced hierarchical relationships between unequal partners. Themes in the literature regarding partnerships promoting decolonization include: (1) mutual partnerships with bidirectional learning and empowerment of host country, (2) sustainable programs and capacity building, and (3) accountability and safety.

In the interest of mutual partnerships, global health programs can build trust with partners by prioritizing community engagement, and emphasize respect, reciprocity, collaboration, and cooperation (Keikelame and Swartz, 2019). Trust is maintained by listening to the community members including traditional practitioners, leaders, lay people, and those on the receiving end of services (Lawrence and Hirsch, 2020; Prasad et al., 2022). Bidirectional learning can include giving partners opportunities to share their knowledge and perspectives (Prasad et al., 2022), as well as equalizing access to opportunities, educational experiences, and credit (Keikelame and Swartz, 2019; Eichbaum et al., 2021). Host communities can be empowered as they are allowed to define their own needs and the activities that take place among their people (Prasad et al., 2022). Recognition of community assets and indigenous strengths also leads to relationships that Keikelame and Swartz (2019) define as “power with” instead of “power over.”

A concern with short-term study abroad experiences is that they lack the structure to be sustainable in the long run. Myers and Fredrick (2017) note that this is one of the challenges that is addressed by creating a longitudinal study abroad program, however they acknowledge logistical barriers to maintaining these programs. Kulesa and Brantuo (2021) advises integrating into the community, and asks international partners to consider, “If you cannot integrate, is your presence needed?” Lawrence and Hirsch (2020) encourages utilizing local institutions and expertise as well as existing infrastructure for research to avoid the trap of the “fly-in, fly-out, parachute and publish” researcher.

Lastly, authors emphasized the need for study abroad programs to be accountable for actions and protect the safety of their host communities (Eichbaum et al., 2021; Prasad et al., 2022). Research and program interventions should follow ethical principles, use understandable language, and collaborate with community leaders and practitioners (Keikelame and Swartz, 2019). Protecting the vulnerable is an important element of building trust (Keikelame and Swartz, 2019), and partners should pay attention to the experiences that have led to fear-based rumors such as those about “blood-stealing” (Lawrence and Hirsch, 2020). Participants and facilitators should recognize potential power imbalances and the dangers such imbalances may pose to partners in a position of lesser power (Kulesa and Brantuo, 2021). Additionally, participants should recognize power imbalances within culture, with an awareness that culture does not excuse or justify harm (Kulesa and Brantuo, 2021).

4. Discussion

As outlined by Salm et al. (2021), the concept of ‘global health’ as a coherent endeavor or discipline has been defined with great variability arising from at least four distinct categorical approaches including: (1) a ‘multiplex approach to worldwide health improvement taught and researched through academic institutions;’ (2) an ethos guided by principles of social justice; (3) a governance activity that arises from problem identification, political decision-making, and allocation of resources; and (4) more vaguely as a ‘polysemous concept with historical antecedents and an emergent future’ (Salm et al., 2021). Given the overlapping, broad range of understandings related to global health, the endeavor of decolonization takes on increased complexity. So much so that complexity theory may be a useful orientation for defining global health in a way that captures global health as the integrated outcome of a rapidly evolving globalized system that includes economic, political, cultural, and environmental forces in a webbed, dynamic, and interdependent fashion (Faerron Guzmán, 2022).

As part of this complexity, it is also important to acknowledge that there is heterogeneity within communities. Not all voices and experiences are the same. Needs and desires may diverge between different groups and individuals, and the moral and ethical frameworks at work may also be varied. Understanding these perspectives, especially those of the most vulnerable, and those most impacted by colonial legacies is an important endeavor and priority (Douedari et al., 2021; Faerron Guzmán, 2022).

Given the level of complexity, the decolonization movement cannot assume that global health is a discrete, malleable enterprise that can be manipulated independent of the larger geopolitical and global contexts within which it functions. As a case in point, Hellowell and Schwerdtle (2022) argue that the astonishingly inequitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines globally represents not only ‘an historic failure of the global health endeavor,’ but more accurately, ‘of the global economic order in which it is embedded.’ The decolonization of global health must therefore coincide with the decolonization of global economic and political orders, or it becomes a myopic movement with limited prospects for achieving its ultimate aims (Hellowell and Schwerdtle, 2022).

Nevertheless, despite ambiguity and complexity, targeted activities within the global health arena can exemplify the overarching aims of the decolonization movement and become forces that influence increasingly larger spheres of global health practice and the larger contexts within which it functions. Global health education in general (Hawks and Judd, 2020; Krugman et al., 2022), and short-term, experiential learning activities in particular, such as study abroad programs (Ohito et al., 2021), are well positioned to actively articulate the many nuances of the global health endeavor, including the complex geopolitical, cultural, and economic contexts within which it operates, to ‘boots on the ground’ students from a wide variety of backgrounds pursuing a wide variety of disciplines in ways that can deeply transform understandings and future behaviors that contribute to decolonization efforts across many dimensions (Sathe and Geisler, 2017).

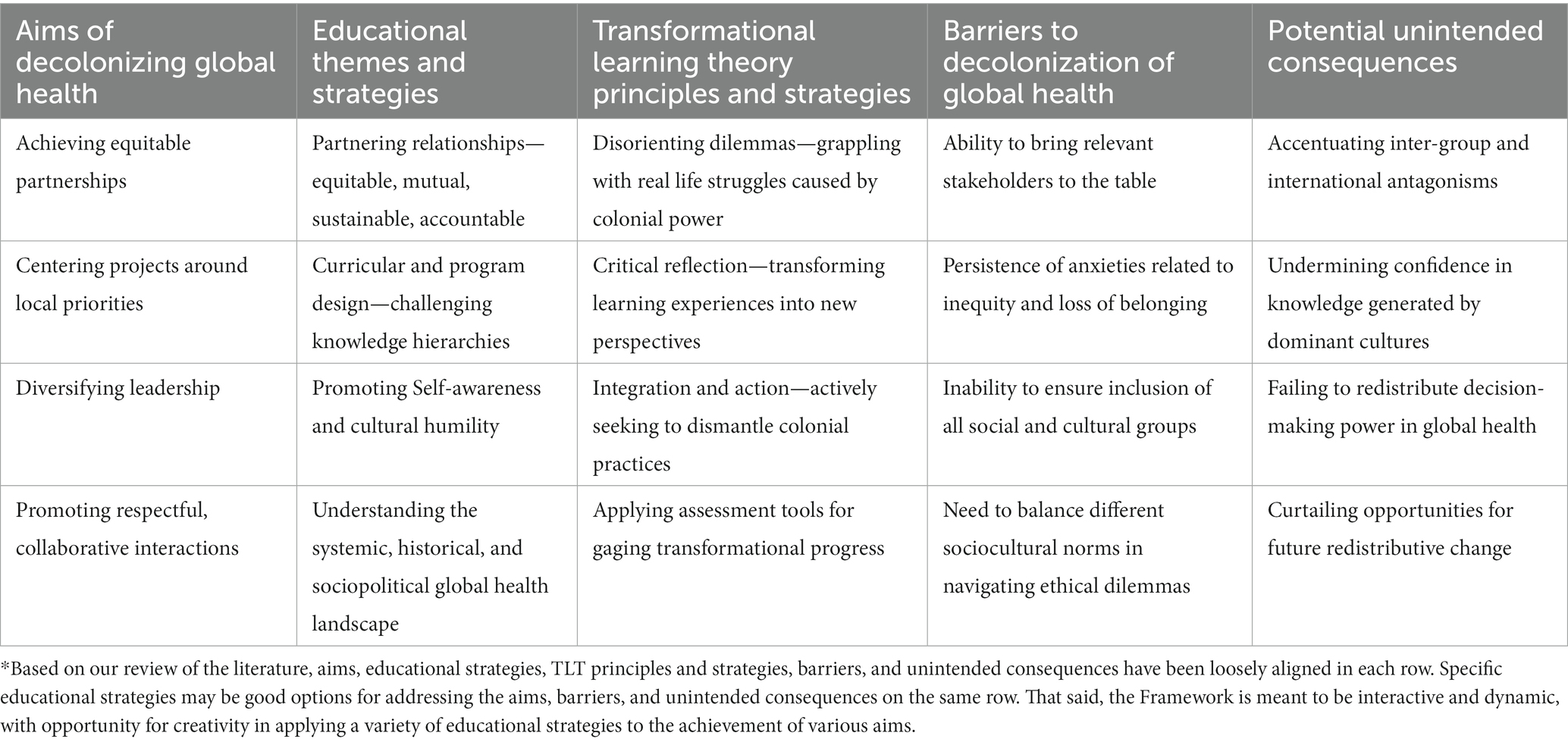

Based on the articles reviewed in this paper, An Interactive Framework for Decolonizing Global Health Education (see Table 1) has been developed that builds on Transformational Learning Theory to articulate educational themes, curricula, learning activities and support systems that strategically align with the aims of (and barriers to) decolonizing global health while actively avoiding negative, unintended consequences and assessing student transformational progress along the way. As outlined in Table 1, the Interactive Framework attempts to align specific aims of decolonizing global health (Decolonizing Global Health Working Group, 2021) with barriers (Kulesa and Brantuo, 2021) and potential unintended consequences (Hellowell and Schwerdtle, 2022) associated with each aim. The Framework then identifies educational themes and strategies, based on Transformational Learning Theory, that might be employed to achieve each aim while mitigating associated barriers and unintended consequences (Lokugamage et al., 2021). While the alignment is not perfect, the Framework provides a dynamic, interactive matrix for applying theory-based pedagogical strategies that can help meet the aims of decolonizing global health while at the same time addressing key barriers and minimizing negative, unintended consequences.

The proposed Framework shares elements of the Fair Trade Learning Rubric developed by Eric Hartman and colleagues which similarly provides important ethical considerations and strategies related to service learning, global engagement, and volunteer tourism (Hartman, 2015; Hartman et al., 2018). The Framework also expands on the article Best Practices in Global Health Practicums (Withers et al., 2018), by specifically identifying decolonization as a targeted outcome of global health practicum experiences.

By conscientiously utilizing the proposed Framework for Decolonizing Global Health Education, global learning and study abroad experiences can contribute to decolonization in numerous ways. Foremost, study abroad programs must conscientiously seek the interests of host communities as determined by the communities themselves. This involves bringing all stakeholders to the table in the form of shared leadership and equitable partnerships that identify priorities, plan activities, resolve ethical dilemmas, and create sustainable, accountable relationships based on trust. Recommended actions include treating local partners as equals in planning and design, providing compensation to hosts for all resources and services rendered, creating opportunities for local practitioners to collaborate, interact, and share knowledge with students, and ensuring the rights and values of local participants are protected.

Additionally, the aims of decolonization are furthered as student participants become aware of and are inspired to dismantle colonial practices. Transformational experiential learning includes engaging students with diverse communities and local knowledge, maximizing participation with local populations and community partners, being exposed to disorienting dilemmas, and engaging in critical thinking and self-reflection that leads to increased cultural competence and action.

As part of study abroad programs, instructors and leaders should design curricula and learning experiences that foster an awareness of colonial and hierarchical historical practices and their impact on current power differences while encouraging an examination of one’s own paradigms and frame of reference. Additionally, the broader influences of colonialism on geopolitical, economic, and cultural structures that constrain global health activities must be presented, discussed, and understood.

As outlined in this paper, short-term, faculty-led study abroad programs that utilize transformational learning theory to carefully address educational themes and design learning activities that align with the aims of decolonizing global health education can be an important step in the overall effort to decolonize global health. Without such efforts, study abroad programs may unwittingly contribute to colonial practices that perpetuate inequities while failing to address social injustices (Hartman et al., 2018).

5. Conclusion

Important steps are being taken globally to address many of the key aims for decolonizing global health. For example, UNESCO’s Recommendation on Open Science is designed to make scientific knowledge more accessible and ensure that the production of knowledge is equitable, sustainable, and inclusive (UNESCO, 2022). The 2015 launch of the Sustainable Development Goals by the United Nations, with the overarching principle of “leaving no one behind,” underscores the central theme of health equity across each of the 17 goals (Marmot and Bell, 2018). These efforts clearly align with other calls for the decolonization of global health and represent necessary strategies for promoting social justice, achieving health equity, and addressing structural violence as a determinant of health throughout the world.

While recognizing that ‘global health’ is a multi-dimensional endeavor that takes place within complex economic and geopolitical forces (Faerron Guzmán, 2022), we nevertheless appreciate the essential value of education as a powerful tool that can support desired outcomes. Specifically, short-term, experiential learning programs can be a meaningful force for promoting decolonization aims if they: (1) are designed within a theory-based framework that incorporates the multiple dimensions of global health; (2) explicitly explore global health endeavors within geopolitical and economic contexts, and (3) provide guided, real-world experiences that help students reflect upon and internalize the values of the decolonization movement (Hawks, 2021). These efforts are consistent with Paolo Freire’s efforts to develop an enlightened educational approach that empowers oppressed populations and delivers on the aims of decolonizing global health (Darder, 2017).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SH, HS, and JH contributed to conception and design of the study. SH and JH organized the database search. HS compiled results and integrated findings into the results section. JH wrote the methods section and designed the PRISMA diagram. SH wrote the first draft of the introduction, discussion, and conclusion sections. SH, HS, and JH had primary responsibility for sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abimbola, S., and Pai, M. (2020). Will global health survive its decolonisation? Lancet 396, 1627–1628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32417-X

Abouzeid, M., Muthanna, A., Nuwayhid, I., El-Jardali, F., Connors, P., Habib, R. R., et al. (2022). Barriers to sustainable health research leadership in the global south: time for a grand bargain on localization of research leadership? Health Res. Policy Syst. 20, 136–114. doi: 10.1186/s12961-022-00910-6

Behari-Leak, K., Josephy, S., Potts, M.-A., Muresherwa, G., Corbishley, J., Petersen, T.-A., et al. (2021). Using vulnerability as a decolonial catalyst to re-cast the teacher as human(e). Teach. High. Educ. 26, 557–572. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2019.1661376

Bhandal, T. (2018). Ethical globalization? Decolonizing theoretical perspectives for internationalization in Canadian medical education. Can Med Educ J 9, e33–e45. doi: 10.36834/cmej.36914

Calderón Farfán, J. C., Dussán Chaux, J. D., and Arias Torres, D. (2021). Food autonomy: decolonial perspectives for indigenous health and buen vivir. Glob. Health Promot. 28, 50–58. doi: 10.1177/1757975920984206

De Savigny, D., and Adam, T. (2009). Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Decolonizing Global Health Working Group (2021). Decolonizing Global Health toolkit. Available at: https://globalhealth.washington.edu/sites/default/files/ICRC%20Decolonize%20GH%20Toolkit_20210330.pdf Accessed April 1, 2023.

Demir, I. (2022). How and why should we decolonize Global Health education and research? Ann. Glob. Health 88:30. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3787

Douedari, Y., Alhaffar, M., Duclos, D., Al-Twaish, M., Jabbour, S., and Howard, N. (2021). “We need someone to deliver our voices”: reflections from conducting remote qualitative research in Syria. Confl. Heal. 15, 28–10. doi: 10.1186/s13031-021-00361-w

Eichbaum, Q. (2017). Acquired and Participatory Competencies in Health Professions Education: Definition and Assessment in Global Health. Acad. Med. 92:468. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001382

Eichbaum, Q. G., Adams, L. V., Evert, J., Ho, M.-J., Semali, I. A., and van Schalkwyk, S. C. (2021). Decolonizing Global Health education: rethinking institutional partnerships and approaches. Acad. Med. 96, 329–335. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003473

Faerron Guzmán, C. A. (2022). Complexity in Global Health- bridging theory and practice. Ann. Glob. Health 88:49. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3758

Faerron Guzmán, C. A., and Rowthorn, V. (2022). Introduction to special collection on decolonizing education in Global Health. Ann. Glob. Health 88:38. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3756

Garba, D. L., Stankey, M. C., Jayaram, A., and Hedt-Gauthier, B. L. (2021). How do we decolonize Global Health in medical education? Ann. Glob. Health 87, 29–24. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3220

Giroux, H. A. (2010). Rethinking education as the practice of freedom: Paulo Freire and the promise of critical pedagogy. Policy Futures Educ. 8, 715–721. doi: 10.2304/pfie.2010.8.6.715

Hartman, E. (2015). A strategy for community-driven service-learning and community engagement: fair trade learning. Michigan J. Commun. Serv. Learn. Fall, 97–100.

Hartman, E., Kiely, R. C., Friedrichs, J., and Boettcher, C. (2018). Community-based global learning: the theory and practice of ethical engagement at home and abroad. Stylus Publishing, LLC. Sterling, VA.

Hawks, S. R. (2021). “Innovative pedagogies for promoting university global engagement in times of crisis” in Resilient pedagogy: Practical teaching strategies to overcome distance, disruption, and distraction. Empower teaching open access book series. eds. T. N. Thurston, K. Lundstrom, and C. González (Logan, UT, USA: Utah State University), 130–147.

Hawks, S. R., and Judd, H. A. (2020). Excellence in the design and delivery of an online Global Health survey course: a roadmap for educators. Pedagogy Health Promot. 6, 70–76. doi: 10.1177/2373379919872781

Hellowell, M., and Schwerdtle, P. N. (2022). Powerful ideas? Decolonisation and the future of global health. BMJ Glob. Health 7:e006924. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006924

Keikelame, M. J., and Swartz, L. (2019). Decolonising research methodologies: lessons from a qualitative research project, Cape Town, South Africa. Glob. Health Action 12, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2018.1561175

Krugman, D. W., Manoj, M., Nassereddine, G., Cipriano, G., Battelli, F., Pillay, K., et al. (2022). Transforming global health education during the COVID-19 era: perspectives from a transnational collective of global health students and recent graduates. BMJ Glob. Health 7:e010698. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010698

Kulesa, J., and Brantuo, N. A. (2021). Barriers to decolonising educational partnerships in global health. BMJ Glob. Health 6:e006964. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006964

Lawrence, D. S., and Hirsch, L. A. (2020). Decolonising global health: transnational research partnerships under the spotlight. Int. Health 12, 518–523. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihaa073

Lokugamage, A. U., Wong, S. H. M., Robinson, N. M. A., and Pathberiya, S. D. C. (2021). Transformational learning to decolonise global health. Lancet 397, 968–969. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00371-8

Marmot, M., and Bell, R. (2018). The sustainable development goals and health equity. Epidemiology 29, 5–7. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000773

Myers, K. R., and Fredrick, N. B. (2017). Team Investment and Longitudinal Relationships: An Innovative Global Health Education Model. Acad. Med. 92:1700. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001768

Naidu, T. (2021). Southern Exposure: Leveling the Northern Tilt in Global Medical and Medical Humanities Education. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 26, 739–752. doi: 10.1007/s10459-020-09976-9

Ohito, E. O., Lyiscott, J., Green, K. L., and Wilcox, S. E. (2021). This moment is the curriculum: equity, inclusion, and collectivist critical curriculum mapping for study abroad programs in the COVID-19 era. J. Exp. Educ. 44, 10–30. doi: 10.1177/1053825920979652

Pentecost, M., Gerber, B., Wainwright, M., and Cousins, T. (2018). Critical orientations for humanising health sciences education in South Africa. Med. Humanit. 44, 221–229. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2018-011472

Prasad, S., Aldrink, M., Compton, B., Lasker, J., Donkor, P., Weakliam, D., et al. (2022). Global Health partnerships and the Brocher declaration: principles for ethical short-term engagements in Global Health. Ann. Glob. Health 88:31. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3577

Ratner, L., Sridhar, S., Rosman, S. L., Junior, J., Gyan-Kesse, L., Edwards, J., et al. (2022). Learner milestones to guide Decolonial Global Health education. Ann. Glob. Health 88:99. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3866

Salm, M., Ali, M., Minihane, M., and Conrad, P. (2021). Defining global health: findings from a systematic review and thematic analysis of the literature. BMJ Glob. Health 6:e005292. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005292

Sathe, L. A., and Geisler, C. C. (2017). The reverberations of a graduate study abroad course in India: transformational journeys. J. Transform. Educ. 15, 16–36. doi: 10.1177/1541344615604230

Skopec, M., Fyfe, M., Issa, H., Ippolito, K., Anderson, M., and Harris, M. (2021). Decolonization in a higher education STEMM institution -- is “epistemic fragility” a barrier? London Rev. Educ. 19, 1–21. doi: 10.14324/LRE.19.1.18

Tracey, P., Rajaratnam, E., Varughese, J., Venegas, D., Gombachika, B., Pindani, M., et al. (2022). Guidelines for short-term medical missions: perspectives from host countries. Glob. Health 18, 19–11. doi: 10.1186/s12992-022-00815-7

UNESCO (2022). An introduction to the UNESCO recommendation on Open Science. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000383771 Accessed August 22, 2023.

Van Winkle, T. N. (2022). Colonization by kale: marginalization, sovereignty, and experiential learning in critical food systems education. Food Cult. Soc. 1–13, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/15528014.2022.2077531

Wessells, M. (2015). Decolonizing global mental health: the psychiatrization of the majority world. Comp. Educ. Rev. 59, 550–552. doi: 10.1086/682012

Withers, M., Li, M., Manalo, G., So, S., Wipfli, H., Khoo, H. E., et al. (2018). Best practices in Global Health practicums: recommendations from the Association of Pacific rim Universities. J. Community Health 43, 467–476. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0439-z

Wong, S. H. M., Gishen, F., and Lokugamage, A. U. (2021). “Decolonising the Medical Curriculum”: Humanising Medicine through Epistemic Pluralism, Cultural Safety and Critical Consciousness. Lond. Rev. Educ. 19. doi: 10.14324/LRE.19.1.16

Keywords: decolonization, global health, education, pedagogy, best practice

Citation: Hawks SR, Hawks JL and Sullivan HS (2023) Theories, models, and best practices for decolonizing global health through experiential learning. Front. Educ. 8:1215342. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1215342

Edited by:

Tracy Rabin, Yale University, United StatesReviewed by:

Carlos A. Faerron Guzman, University of Maryland, United StatesBudd Hall, University of Victoria, Canada

Copyright © 2023 Hawks, Hawks and Sullivan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Steven R. Hawks, c3RldmUuaGF3a3NAdXN1LmVkdQ==

Steven R. Hawks

Steven R. Hawks Jenna L. Hawks

Jenna L. Hawks