- Department of Psychology, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

Introduction: This study investigated the relationship between teachers’ sentiments about physical appearance, student–teacher relationships, psychological adjustment, and the risk of becoming a victim of bullying.

Method: Participants consisted of 995 students (471 females, 47.3%; Mage = 11.3, SDage = 1.49) and 64 teachers (56 females, 87.5%; Mage = 47.59). Students reported their levels of psychological adjustment and their involvement with bullying victimization, while teachers rated relationship quality with their students and reported their sentiments about students’ physical appearance. Teachers’ sentiments about physical appearance were analyzed using the NRC Emotion Lexicon. Correlation and mediation analyses were conducted with Mplus, using a multicategorical antecedent.

Results: Results indicate that teachers’ positive ratings of students’ physical appearance were correlated with close teacher–student relationships, less conflictual relationships, whereas negative ratings were correlated with more conflictual student–teacher relationships and increased bullying victimization risk. Psychological adjustment mediated the relationship, with positive adjustment associated with closer relationships and negative adjustment associated with more conflict.

Discussion: This study suggests the importance of teachers’ sentiments about students’ physical appearance. Positive sentiments promote supportive relationships and reduce the risk of bullying victimization, while negative sentiments erano correlate ad una relazione studente-insegnante netagativa and increased risk of bullying victimization. Promoting positive interactions between teachers and students and addressing appearance biases are critical to creating inclusive educational environments. Further research should focus on understanding and examining the impact of teacher attitudes on student well-being and bullying dynamics.

Introduction

In the educational setting, schools are an essential developmental context for children, significantly influencing their psychological adjustment (Baker et al., 2008). In this context, teachers are an essential part of the classroom community and play a crucial role in promoting optimal psychological adjustment among students at different grade levels. This is particularly relevant in Italy, where formal schooling typically begins at age 6, when children enter elementary school, which spans 5 years (Matteucci and Farrell, 2019). Prior to elementary school, Italian children can attend kindergarten starting at age 3 (Ferraris and Persico, 2019; Matteucci and Farrell, 2019). Then, at age 11, students move to the second school cycle, which includes 3 years of middle school, followed by high school, which lasts either 3 or 5 years, depending on the curriculum chosen. While elementary school classes are usually led by one or two teachers, secondary school introduces a broader range of subjects and a higher number of teachers per class (Ferrer-Esteban, 2011). Compulsory education in Italy continues until the age of 16 (Ferraris and Persico, 2019).

Some authors (Pianta, 2001; Verschueren and Koomen, 2012; Longobardi et al., 2019b, 2021b, 2022; Pallini et al., 2019) have hypothesized that the quality of teacher–student relationships is crucial for children to adjust to school in terms of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive processes. Further, these relationships are key to reducing the risk of victimization and promoting better psychological well-being. However, although some evidence from the Italian context suggests that relationships with teachers can play a role in reducing the risk of victimization (Marengo et al., 2021), little is known about the possible factors involved. In addition to the risk of victimization, several international studies indicate that a conflictual relationship with the teacher is associated with an increased likelihood of physical and verbal aggression toward peers (Wang et al., 2015; Elledge et al., 2016). Such student–teacher conflict can undermine teachers’ adherence to anti-bullying norms and internalization of group norms related to bullying (Wang et al., 2015). This study aims to examine the potential mediating roles of teacher–child relationship quality and psychological adjustment in the association between teacher sentiment and bullying victimization. The basic hypothesis is that teacher’s sentiment about physical appearance may influence the quality of relationships with children and the child’s psychological adjustment, increasing the risk of victimization.

Student physical appearance and teacher sentiments and expectations

In society, individuals often form stereotypes and social judgments based on the outward appearance of others (Koenig, 2018). It is evident that physical appearance plays an important role in forming people’s attributions, attitudes, and behaviors toward others (Rodgers et al., 2019). These attitudes can also affect teachers. They can form judgments and expectations about a student’s behavior, abilities, and performance based on specific student characteristics, such as socioeconomic status, gender, ethnicity, special needs, and appearance (Denessen et al., 2020). Research on the influence of teachers’ perceptions (or expectations) on students’ psychological adjustment and academic success began with Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968) pioneering work on the “Pygmalion effect,” subsequently renamed the self-fulfilling prophecy effect (Lorenz, 2021). According to this perspective, teachers form perceptions of students and interact with them in such a way that students are encouraged to align themselves with these expectations, leading to so-called teacher expectation effects (Rubie-Davies et al., 2014). Therefore, the teacher may set expectations for the student and engage in various verbal (and nonverbal) behaviors that cause the student to conform to those expectations (Lorenz, 2021). For example, teachers may provide more instructional support and oral feedback to students with high expectations (compared to those with low expectations), which can impart better adaptation and academic performance (Wang et al., 2018).

Teachers tend to form expectations based on different characteristics of the student, although physical appearance is probably the main source of information (Dusek and Joseph, 1983; Fitzpatrick et al., 2016). Teachers can infer student’s characteristics through physical appearance and clothing (such as gender, ethnicity, and social status), which are characteristics that are potentially related to teacher expectations (Wang et al., 2018). According to sociological perspectives, Western teachers tend to consider ideal students as those who exhibit the characteristics of the middle classes (Rist, 1970, 2000). Accordingly, it is possible that students who are perceived as coming from high or low social classes tend to solicit different attitudes in the teacher (Fitzpatrick et al., 2016). In addition, gender and ethnicity are two important factors in the perception of a student’s physical appearance. With regard to gender, several studies have indicated that teachers tend to report a higher expectancy of achievement for females compared to males, although there is no substantial agreement in the literature (Wang et al., 2018). Regarding ethnicity, several studies have suggested there is a relationship between belonging to ethnic minority groups and lower teacher expectancies in Europe (Tobisch and Dresel, 2017) and United States (Shepherd, 2011). Some work addresses other physical characteristics, such as weight and height. There is evidence that overweight students are judged by teachers to be less clean, less emotionally competent, and have more family problems than thin ones (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 1999). Similarly, smaller and heavier students were recently found to be rated lower by teachers (Black and de New, 2020). More generally, a recent meta-analysis (Pit-ten Cate and Glock, 2019) of teachers’ attitudes toward students from diverse social groups with a variety of characteristics (such as ethnicity, gender, obesity, special education needs, and socioeconomic status) found that, on average, teachers’ attitudes favored non-marginalized groups. Moreover, according to the authors, these attitudes are implicit and automatic, that is, they are activated without control or volition.

Some research has focused more specifically on the student’s perceived physical attractiveness to the teacher (Clifford and Walster, 1973; Stroebe, 2020). In a landmark experiment, Clifford and Walster (1973) showed that the student’s attractiveness was significantly associated with the teacher’s expectations of the student’s intelligence, future progress in school, and popularity among peers, as well as parental involvement in the child’s education. Finally, the meta-analysis by Dusek and Joseph (1983) highlighted greater teacher expectations (in terms of academic achievement, personality, and social skills) for students judged to have increased face attractiveness. Similarly, Ritts et al. (1992) reported that teachers rated physically attractive students as more intelligent and with more advanced social skills compared to their unattractive counterparts. Overall, the literature thus seems to suggest that, teachers may formulate expectations based on a student’s s appearance and modify their behavior accordingly (Kenealy et al., 1988; Stroebe, 2020). In this direction, increased teacher expectations tend to promote better academic performance (Wang et al., 2018) and influence a range of psychosocial and behavioral outcomes such as learning self-concept (Upadyaya and Eccles, 2015; Wang et al., 2018), achievement motivation (Woolley et al., 2010), and self-efficacy (Vekiri, 2010). Therefore, it is possible that higher teacher expectations can promote improved school adjustment, positively influencing children’s psychological adjustment. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have directly investigated the possible impact of teacher’s sentiment on psychological adjustment in primary and middle school environments. Nevertheless, teachers play an important role in the social dynamics of the classroom (Farmer et al., 2011) and could promote psychological adaptation to the school context through their relationships (Longobardi et al., 2019a; Lin et al., 2022), potentially resulting in a lower risk of victimization (Longobardi et al., 2021a; Marengo et al., 2021). Considering that the perception of a student’s physical appearance could influence the teacher’s expectations and attitudes towards that student, it is possible that this perception could influence the teacher–student relationship. However, the relationship between teachers’ feelings about their physical appearance and the quality of the teacher–student relationship appears to be poorly studied. In this regard, Fitzpatrick et al. (2016) found that elementary school teachers tend to rate low-social status students who appear poorly dressed, tired, sleepy, or hungry as less academically competent and less engaged, which in turn increases the risk of a more negative relationship with the teacher. Thus, it is important to examine the potential impact of teachers’ sentiment about students’ physical appearance on the quality of the teacher–student relationship, as positive teacher relationship quality tends to promote better psychological adjustment to the school context, is associated with fewer psychological symptoms and leads to lower risk of victimization (Longobardi et al., 2019a; Marengo et al., 2021).

Student–teacher relationships and psychological adjustment

According to the developmental systems theory proposed by Sabol and Pianta (2012), the quality of teacher–student relationships could be influenced by various factors, including the characteristics of the students themselves. Inspired by attachment theory, several authors suggest that teachers constitute a relational and affective reference point for students, providing them with support and comfort in moments of stress and encouraging exploration of the learning environment (Silva et al., 2011; Verschueren and Koomen, 2012; Bahia et al., 2013; Prino et al., 2023). Accordingly, positive relationships with teachers (characterized by affection, closeness, and support) tend to be associated with improved academic results (Hamre and Pianta, 2001), greater prosocial behavior and a reduction in psychological symptoms (Hamre and Pianta, 2001; Longobardi et al., 2019a). These factors can favor improved adaptation to the school context. Conversely, negative relationships (characterized by detachment and conflict) tend to be associated with poorer developmental outcomes (Hamre and Pianta, 2001) and increased psychological distress (Marengo et al., 2018; Longobardi et al., 2019a). Shy and anxious students tend to report more conflictual relationships with teachers (Zee and Roorda, 2018), while several studies have suggested a strong relationship between externalizing behaviors and conflictual relationships with teachers (Baker et al., 2008). Furthermore, teachers can foster more positive classroom climates through positive relationships with students (Hamre and Pianta, 2001), increasing inclusion in the class group and discouraging aggressive behavior (Hendrickx et al., 2016). This is particularly important for students at risk of victimization in the school context.

Teacher–student relationships and risk of bullying victimization

Bullying is one of the most studied forms of school violence in the literature (Longobardi et al., 2017, 2019a). Bullying is typically defined as a frequent, repeated, and intentional form of aggression in which there is an imbalance of power or strength between the bully and the victim (Olweus and Limber, 2010; Fabris et al., 2021; Marengo et al., 2022). Bullying victimization tends to be associated with lower psychological adjustment, which even has long-term effects on victims’ psychological well-being (Schoeler et al., 2018; Prino et al., 2019; Fabris et al., 2020). As mentioned earlier, evidence suggests that the quality of the relationship with the teacher plays a role in students’ risk of victimization. Teachers can convey prosocial relational patterns, simultaneously encouraging correct behavior and discouraging bad behavior. Further, they act as a buffer for relationships within the class group (Farmer et al., 2011; Quaglia et al., 2013). Moreover, teachers can mediate peer relationships, stimulate a positive classroom climate, and ensure adherence to rules (Quaglia et al., 2013). In this direction, teachers act as regulators of relationships and play a decisive role in counteracting forms of bullying. Some evidence suggests that students who report conflictual relationships with teachers tend to be at greater risk of bullying victimization (Elledge et al., 2016; Marengo et al., 2018, 2021). Here, teachers could act in the classroom as a social reference. In this sense, if a relationship with a student is negative and conflictual, classmates may make inferences about that student’s attributes and likeability (Hughes et al., 2001; Farmer et al., 2011). Thus, a student having a negative relationship with a teacher could be more likely to be excluded and rejected by peers (Hughes et al., 2001; Hendrickx et al., 2016), placing them at greater risk of being victimized (Longobardi et al., 2021a). In particular, some evidence suggests that rejected students are at greater risk of victimization when they experience a conflictual relationship with their teacher (Marengo et al., 2021). Accordingly, it is likely that negative relationships can undermine a teacher’s ability to intervene effectively in protecting students at risk of victimization, rendering them more isolated and at greater risk of suffering this behavior. Accordingly, positive relationships with teachers tend to be a protective factor for students at risk of peer victimization, probably by offering support and interventions to protect victimized students and increasing connection and acceptance by their peer group (Elledge et al., 2016). Negative relationships with teachers can deteriorate social reputations and expose students to increased risks of bullying victimization through psychological symptoms. Moreover, negative relationships with teachers can reduce a student’s ability to regulate dysfunctional behavior and could be associated with increased psychological symptoms (Longobardi et al., 2019a, 2021a). Students with emotional and behavioral disorders are at greater risk of being disliked by peers and can be at greater risk of becoming targets of victimization (Cook and Cameron, 2010). Therefore, negative and conflictual relationships with teachers can reduced a student’s psychological adjustment, resulting in increased risk of victimization, probably due to a greater peer disliking and low social status.

The aim of the study

Ultimately, a close relationship with the teacher seems to predict a lower risk of victimization, whereas a conflictual relationship tends to predict a higher risk of victimization. However, much research is needed to understand what factors and mechanisms are involved in explaining this relationship. This study aims to contribute to the existing body of knowledge by examining the indirect relationship between teachers’ sentiments regarding students’ physical appearance and the risk of victimization. Specifically, it is hypothesized that teachers’ positive perceptions of students’ physical appearance will promote the development of a closer student–teacher relationship. It is expected that this, in turn, will generate more positive attitudes and expectations toward the student and lead the teacher to invest in a supportive relationship characterized by affection, closeness, and assistance. Consequently, it is postulated that this positive sentiment towards the student’s physical appearance, mediated by a close teacher–student relationship, will enhance the student’s psychological well-being and subsequently decrease their vulnerability to victimization. It is possible that by having a more positive relationship, the teacher helps the student feel supported in the face of learning challenges, feel more effective, and develop greater social–emotional skills. In the context of a secure and positive relationship with the teacher, therefore, the student may report better psychological adjustment to the classroom context, which also leads to greater acceptance by peers, ultimately resulting in a lower risk of victimization.

In contrast, a negative evaluation of a student’s physical appearance is expected to be associated with a more conflictual teacher–student relationship. Consequently, a high-conflict relationship is expected to increase the risk of victimization by decreasing the student’s psychological adjustment. The present study is exploratory in nature and is the first investigation of its kind conducted in Italy. Based on the existing literature, the primary aim is to investigate whether the teacher’s expectations, as measured by their perceptions of the student’s physical appearance, can influence the quality of the teacher–student relationship and subsequently contribute to the student’s psychological adjustment, ultimately leading to a lower risk of victimization.

Method

Participants

The student participants comprised 995 students (471 females, 47.3%) from five different grades: Grade four (n = 240, 24.1%), Grade five (n = 198, 19.9%), Grade six (n = 152, 15.3%), Grade seven (n = 232, 23.3%), and Grade eight (n = 173, 17.4%). These students had a mean age of 11.3 years (SD = 1.49), ranging from nine to 14. Most students identified themselves as Italian (81.2%), while others belonged to other groups (e.g., Moroccan 3.9% and Albanian 3.1%). All students were able to completely understand the Italian language. There were 64 teacher participants (56 females, 87.5%) with a mean age of 47.59 years, ranging from 25 to 65. On average, they had teaching experience of 20.0 years (SD = 10.04), ranging from 2 to 42. Weekly, they taught an average of 11.44 h (SD = 5.94) in the classroom. All participants were recruited through the authors’ personal social network and recruitment emails sent to schools previously unknown to the research team. These schools located in a large city and in some small cities and towns near this city in northwestern Italy.

Measurement

Teacher sentiment ratings about students’ physical appearance

Teacher sentiment ratings about students’ physical appearance were measured by an open-ended question without further instructions: “What physical characteristics of this child are particularly noteworthy, in a positive or negative sense?” In the current data, written answers for 472 students (47.4%) were provided by their head teachers. The lengths of these answers ranged from 1 to 29 words, with an average of 3.65 (e.g., “pretty face,” “Very nice face, excessively overweight”). The National Research Council of Canada (NRC) Emotion Lexicon (Mohammad and Turney, 2013) was employed to obtain teacher sentiments about students’ physical appearance in their answers. The NRC Emotion Lexicon is a state-of-the-art tool for analyzing sentiments through informal short texts (for more details, see Mohammad and Turney, 2013; and see the website: http://saifmohammad.com/WebPages/NRC-Emotion-Lexicon.htm). The scores in 8 affect categories were obtained for each word in the text. This comprised eight basic emotions (anger, fear, anticipation, trust, surprise, sadness, joy, and disgust) and two sentiment polarities (positive and negative). Specifically, the scores indicate the number of words using in the teachers’ descriptions reflecting each specific emotion/sentiment. The positive and negative category scores in the description for one specific student were calculated by summing the scores belonging to the same affect category in this description. The final score for a student was computed by subtracting the sum of the negative categories from the sum of the positive categories. For the final score, a positive value represents an overall positive sentiment toward a student’s physical appearance, zero means an overall neutral sentiment, and a negative value indicates an overall negative sentiment. According to this final score, students were divided into four groups: (1) missing group (teachers failed to evaluate the students’ physical appearance as noteworthy); (2) negative group; (3) neutral group (i.e., had a balance of positive and negative sentiments, or did not have any sentiment words); and (4) positive group.

Teacher–student relationships

Teacher–student relationships were measured by using the student teacher relationship scale (STRS). This was developed by Pianta (2001) with three subscales: closeness (e.g., “this child openly shares his/her feelings and experiences with me.”), conflict (e.g., “this child remains angry or is resistant after being disciplined.”), and dependence (e.g., “this child is overly dependent on me.”). The closeness and conflict subscales from the Italian version of the STRS (Fraire et al., 2013) were used in this study. Since the dependence dimension was not related to our research aims, it was excluded. Teachers were asked to use a 5-point scale for their ratings, where 1 = completely disagree and 5 = completely agree. The average of all item ratings was calculated and taken as the final score for each participant, with a higher score indicating a teacher–student relationship with higher closeness or conflict. In the current research, these two subscales exhibited good reliability: closeness (Cronbach’s α = 0.87, McDonald’s ω = 0.88) and conflict (Cronbach’s α = 0.92, McDonald’s ω = 0.92).

Additionally, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to evaluate the measurement model of the instrument (Alias et al., 2015). The results indicated good fit indices for the Closeness dimension (χ2/df = 4.58, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.03), and the Conflict dimension (χ2/df = 4.71, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.03).

Psychological adjustment

The strength and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) developed by Goodman (1997) was used to measure the total difficulties of students. This is a multidimensional scale that includes five subscales: (1) emotional problems (5 items, such as “often unhappy, depressed or tearful”); (2) conduct problems (5 items, such as “generally well behaved, usually does what adults request,” reversed scored); (3) hyperactivity (5 items, such as “easily distracted, concentration wanders”); (4) peer problems (5 items, such as “has at least one good friend,” reversed scored); and (5) prosocial (5 items, such as “helpful if someone is hurt, upset, or feeling ill”). Teachers were asked to rate these on a 3-point scale, where 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, and 2 = certainly true. The total difficulties score (ranging from 0 to 40) was generated by summing the scores of each item in subscales (1) to (4) (the prosocial subscale was not used), with higher score indicating worse psychological adjustment. In the current study, this scale had good reliability, with Cronbach’s α = 0.87, McDonald’s ω = 0.87. Additionally, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the measurement model of the Total Difficulties construct. The results revealed acceptable fit indices for the Total Difficulties construct (χ2/df = 4.95, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.90, SRMR = 0.05).

Bullying victimization

Bullying victimization of students at school in the previous year was measured by the victimization section of the adolescent peer relations instrument (APRI, Marsh et al., 2011). Three types of victimization in a school context were captured by the three subscales of APRI: (1) physical (6 items, such as “I was pushed or shoved”); (2) verbal (6 items, such as “I was ridiculed by students saying things to me”); and (3) social (6 items, such as “I wasn’t invited to a student’s place because other people did not like me”). Students were required to report the frequency of being bullied on a 6-point scale, from 1 = never to 6 = every day. The mean of all item ratings was calculated as the final bullying victimization score, with a higher score reflecting a higher frequency of being bullied. In the current research, the APRI had good reliability, with Cronbach’s α = 0.91, McDonald’s ω = 0.91. Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to evaluate the measurement model of the Bullying Victimization construct. The results indicated satisfactory fit indices for the Bullying Victimization construct (χ2/df = 3.94, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.04).

Procedure and ethical approval

Trained research assistants were placed in schools to collect data from classrooms. Students were asked to finish the questionnaires in their classrooms, and teachers were required to fill in the questionnaires to evaluate each student in their class when they were not teaching (Good and Brophy, 1997). This study followed the ethical code of the Italian Association for Psychology (AIP), and the procedure was approved by the institutional review board of the authors’ affiliated university (protocol no. 118,643). The consent forms were signed prior to data collection, and participants were told they could refuse to participate and/or drop out whenever they wanted to. Parents also received an information letter and they could deny participation in this research. The data were used only for research purposes without any identifying information to ensure anonymity.

Data analysis

Data analyses were conducted in SPSS 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States) and Mplus 8.3 (Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, United States). First, Spearman’s correlation coefficients between the 10 affects, demographic variables (i.e., gender and age), main studied variables (i.e., teacher–student relationships, total difficulties, and victimization), and descriptive statics were calculated. Simultaneously, mean differences of the main studied variables in four student groups (missing group, negative sentiments group, neutral sentiments group, and positive sentiments group) were explored. Second, path analysis with multi-categorical independent variables was employed to explore the relationship between teachers’ sentiments about student physical appearance and bullying victimization frequency and the mediating roles of students–teacher relationships and student total difficulties. For the categorical independent variables, four dummy-coded variables (coded as 0 or 1, where 0 means not belonging and 1 means belonging to this group) were created to represent the following four groups: (1) missing, (2) negative sentiments, (3) neutral sentiments, and (4) positive sentiments. The missing group was regarded as the reference group when estimating the model. Finally, all possible mediating effects were further examined and confirmed using the bootstrap procedure with a bootstrap sample size of 10,000. In mediation analysis, bootstrapping is widely used for the construction of confidence intervals for indirect effects, and it makes no assumption about the shape of the sampling distribution (Hayes, 2017). If zero is not included in the 95% bootstrap confidence intervals, the indirect effect is regarded as significant.

Results

Correlations and descriptive statistics

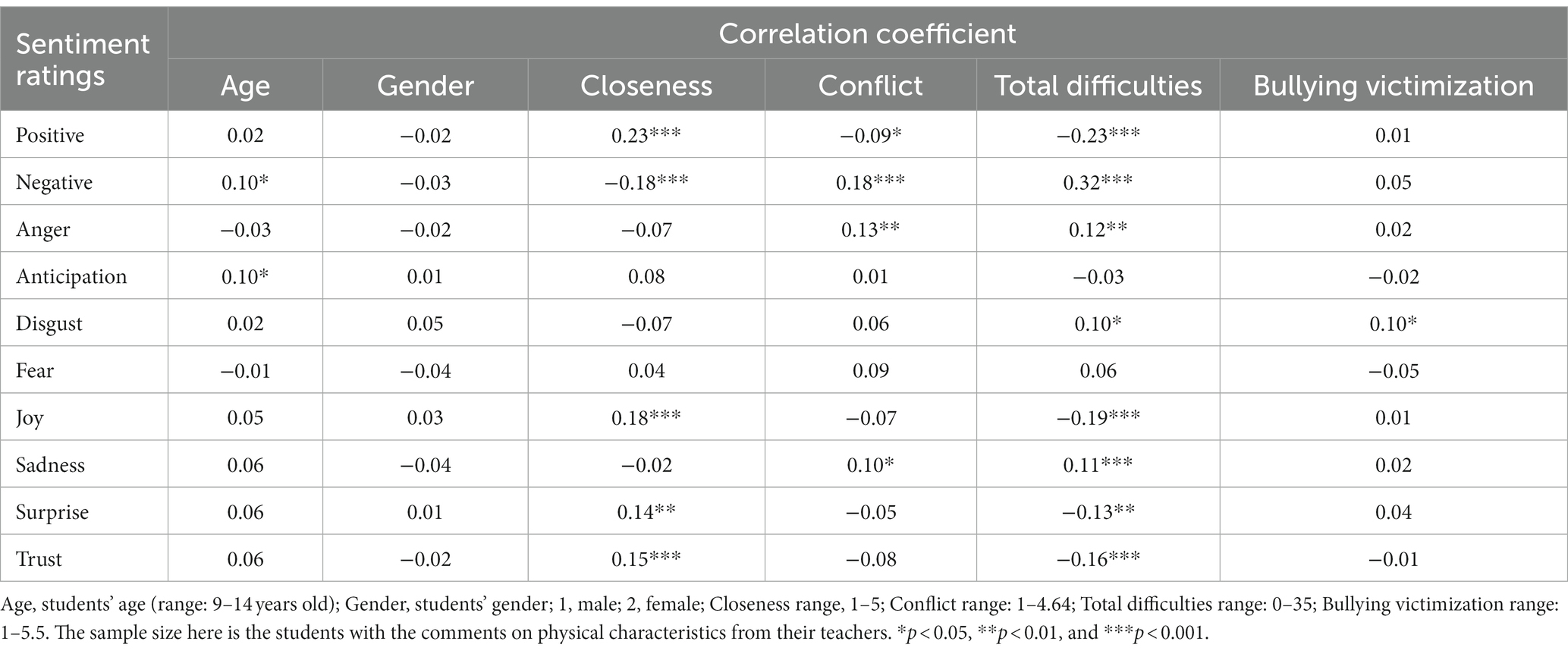

The correlation coefficients are displayed in Table 1. For the demographic variables, student age was positively associated with negative teacher sentiment ratings and the use of words that reflected anticipation, while there was no significant correlation between student gender and teacher sentiment ratings. For the main studied variables, closeness in teacher–student relationships was positively correlated with words reflecting joy, surprise, trust, and positive sentiment polarity, while it was negatively associated with negative sentiment polarity. Conflict was positively associated with negative sentiment polarity with words reflecting anger and sadness, while it was negatively correlated with the positive sentiment polarity. Except for fear and anticipation, student total difficulties were significantly associated with all the sentiment ratings, while bullying victimization was only significantly correlated with the sentiment of disgust. According to Cohen (1988), most of the significant correlation coefficients in Table 1 were in the range of small (r = 0.10) to medium (r = 0.30).

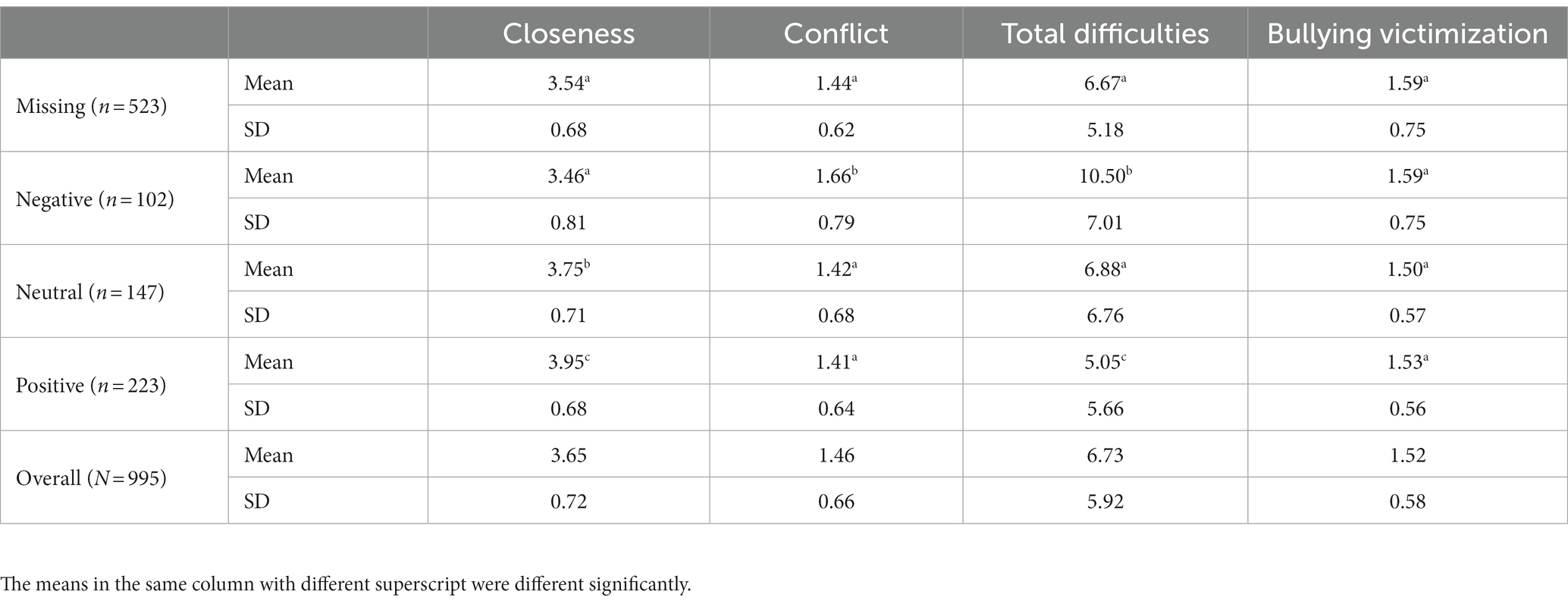

The mean differences of the main studied variables in the four groups were then compared. As presented in Table 2, there were group differences in closeness, conflict, and total difficulties. Specifically, for students in the negative group, they had the lowest levels of closeness (Cohen’s d = 0.66 between the highest and lowest groups, the same as the following ds), and highest level of conflict (Cohen’s d = 0.35) and total difficulties (Cohen’s d = 0.86). For students in neutral group, they had mid-level of closeness and conflict with teacher, and total difficulties. For students in the positive group, they had the closest relationships with teachers, less conflict compared to the negative group, and the lowest level of total difficulties.

Testing the mediated associations

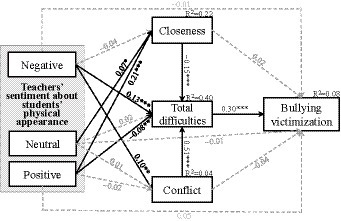

The results of path analysis are illustrated in Figure 1. Although the residual direct effects between teacher sentiments about students’ physical appearance and student bullying victimization were nonsignificant, the indirect paths from teacher sentiments to bullying victimization through teacher–student relationships and total difficulties were significant. Specifically, negative sentiment (β = 0.13, p < 0.001), positive sentiment (β = −0.08, p < 0.01), closeness (β = −0.15, p < 0.001), and conflict (β = 0.51, p < 0.001) was significantly associated with total difficulties, which in turn was positively associated with bullying victimization (β = 0.30, p < 0.001). In addition, negative sentiment was positively associated with conflict (β = 0.10, p < 0.01) and positive sentiment was positively associated with closeness (β = 0.21, p < 0.001). Neutral sentiment was positively correlated with closeness (β = 0.07, p < 0.05). Therefore, closeness, conflicts, and total difficulties might be significant mediators between teacher sentiments and student bullying victimization.

Figure 1. The mediating model (N = 995). All the regression coefficients are standardized. Student’s gender and age were included as control variables and closeness and conflict were correlated with each other but they not illustrated in the figure to make the picture concise. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

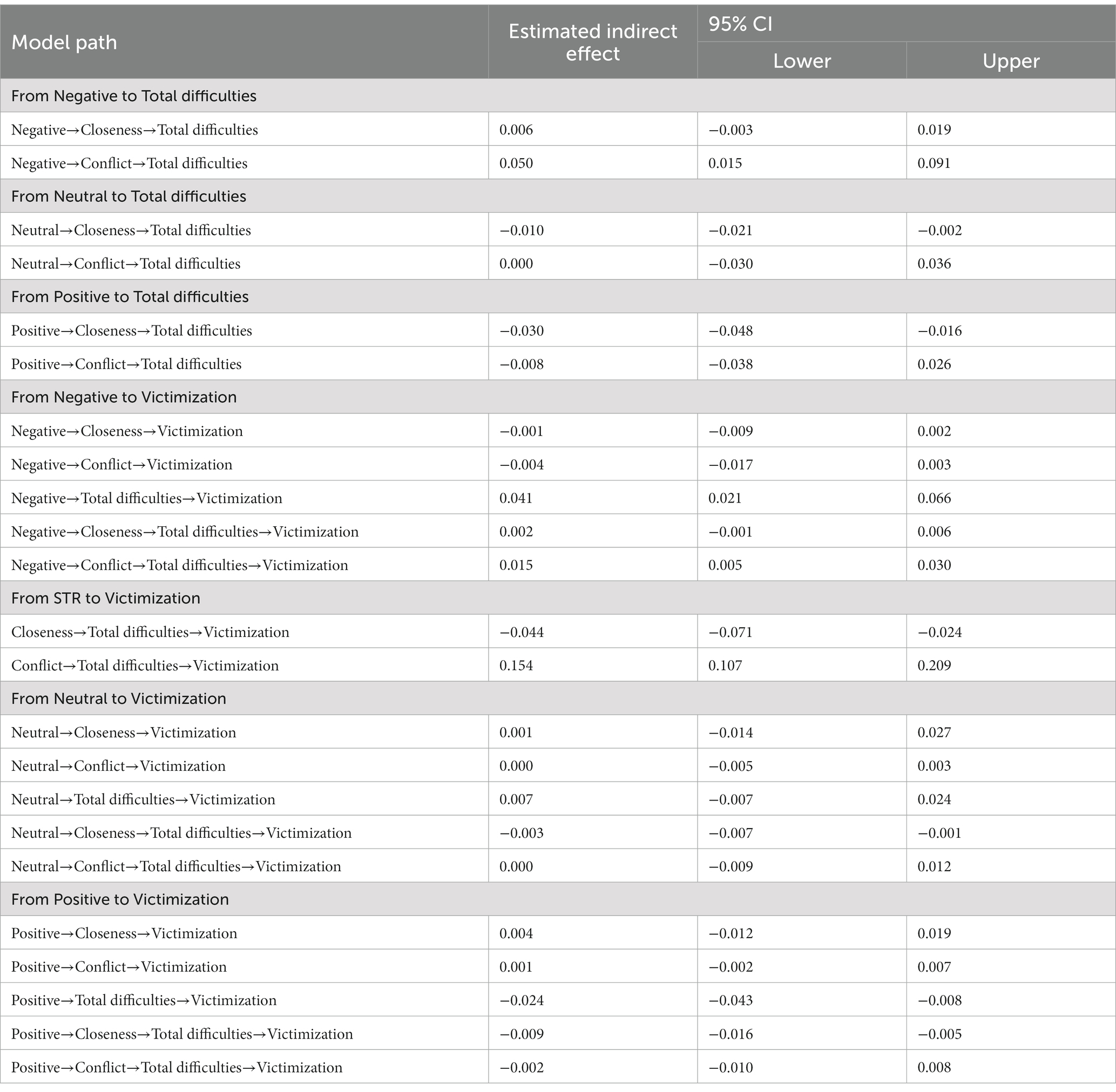

To examine the mediating effects further, bootstrapping 95% CIs were generated for all the indirect effects in the mediating model. As shown in Table 3, zero was not included in the 95% CIs of all potential indirect effects in Figure 1. Therefore, total difficulties played a significant mediating role between teacher sentiments (both negative and positive) and student bullying victimization. In addition, the serial indirect effect of negative sentiment on bullying victimization (through conflict and total difficulties) and the serial indirect effect of positive and neutral sentiment on bullying victimization (through closeness and total difficulties) were significant. Therefore, both teacher–student relationships (closeness and conflict) and student total difficulties played mediating roles between teacher sentiments and student bullying victimization.

Discussion

Very few studies consider teacher sentiments about physical appearance a possible risk factor that could indirectly be associated with the risk of peer victimization in the school context (López et al., 2020; Lorenz, 2021; Marengo et al., 2021). From the analyses, it emerges that teacher sentiments may be a risk factor indirectly associated with the risk of victimization in primary and middle school students. Furthermore, the relationship between teacher sentiment and bullying victimization appears to be mediated by a reduction in psychological adjustment. As it is already highlighted, teachers tend to create expectations about their students, and physical appearance appears to be a possible determinant of these expectations (Dusek and Joseph, 1983; Fitzpatrick et al., 2016). Some evidence has suggested that teachers tend to rate physically attractive students as more intelligent and have greater social skills compared to unattractive children (Dusek and Joseph, 1983; Ritts et al., 1992). Therefore, it is possible that teachers engage in more positive relationships (characterized by closeness, affection, and support) with children they judge more positively. The data obtained in this study support the hypothesized relationship and contribute to the existing understanding of the influence of students’ physical appearance on teachers’ mood. Specifically, the results suggest a positive relationship between teachers’ positive feelings and the development of closer relationships with students. Conversely, negative teacher sentiments are associated with more conflictual relationships with students. Therefore, it is possible that perceptions developed by teachers about the physical appearance of students may be associated with different behaviors towards them, ultimately influencing the quality of teacher–student relationships in accordance with their own expectations and perceptions. In turn, the quality of teacher–child relationships tend to be associated with students psychological adjustment in the classroom context. In agreement with previous literature, the data report that close relationships with teachers tend to be associated with improved psychological adjustment, whereas conflictual relationships tend to constitute a risk factor for decreased in psychological wellbeing. It is possible that students feel supported in their process of adapting to the school context within safe, warm, and supportive relationships. Through close relationships with teachers, students feel supported in the face of learning challenges, can internalize more positive behavioral patterns, develop adaptive social skills, and have more positive beliefs about themselves and others (Hamre and Pianta, 2001; Sabol and Pianta, 2012). Conversely, conflictual relationships tend to be associated with increased emotional and behavioral disturbances, resulting in greater psychological distress (Longobardi et al., 2019a). Hence, it is possible (based on the data) that a teacher’s sentiments regarding a student’s physical appearance could result in them changing their attitudes and relationships with that child. In this way, a negative sentiment tends to be associated with a more negative relationship, while a positive sentiment tends to be associated with a more positive relationship, promoting better psychological adaptation of the student.

Finally, the data from this study suggest that teacher sentiments towards children’s appearance are not only related to their psychological well-being, but also appear to be associated with increased risk of victimization. The results suggest that teacher mood influences victimization risk by affecting children’s psychological adjustment. It is plausible that positive or negative attitudes toward a child may be perceived by other classmates, which in turn affects the child’s social standing and the process of peer acceptance and integration within the class group. Consequently, a negative teacher–student relationship is generally associated with greater peer disapproval, while a positive relationship is generally associated with greater levels of peer acceptance (Hughes et al., 2001). The results of this study provide partial support for this hypothesis by suggesting that positive teacher feeling is associated with a lower risk of victimization because it enhances children’s psychological adjustment. Further, it is possible that when a teacher perceives a student in a positive way, they tend to establish a closer relationship, encouraging the development of adequate social competence and psychological adaptation. Accordingly, the student is perceived more positively by peers and may be more included in the peer group, reducing the risk of victimization (Marengo et al., 2021). Conversely, it is possible that students having closer relationships with teachers are more protected from the risk of victimization when teachers have positive impressions of them, probably because students can count on more support and intervention in cases of victimization. Moreover, potential aggressors could be discouraged from attacking, fearing possible punishment by teachers.

The analysis conducted in this study included the condition of neutral teacher sentiments regarding students’ physical appearance, which represents a new contribution to the literature. Although no specific hypotheses were made regarding this condition, the results suggest an indirect relationship between neutral teacher sentiments and improved psychological adjustment through the development of a close teacher–student relationship. Psychological adjustment, in turn, mediates the relationship between closeness to the teacher and victimization risk. Specifically, higher levels of psychological adjustment are associated with lower risk of bullying victimization. This finding is interesting because it seems to bring into continuity teachers’ neutral and positive sentiments about students physical appearance and their relationship with the other constructs. Thus, it is possible that a neutral attitude is not a barrier to establishing a positive relationship with the teacher, and that this tends to be a protective factor for psychological adjustment and risk of victimization. In this sense, it is not necessary for the teacher to develop positive sentiments in order to establish a close relationship with the students. From the data, even neutral sentiment is associated with a close relationship with the teacher, although to a lesser extent. However, compared to a neutral sentiment, a negative sentiment seems to be more detrimental to the quality of the relationship with students, as it is more likely to be associated with a conflictual relationship. Future studies could further investigate the similarities and differences between the various grade of teachers’ sentiments about students’ physical appearance.

Finally, it is important to note that the indirect effects between independent and dependent variables are very weak and relatively small. This finding is difficult to explain, but future studies may identify additional potential mediators (such as peer acceptance/social status) that could have a larger effect.

In conclusion, the data revealed that teacher assessment of students’ physical appearances may influence teacher–student relationships and students’ psychological adjustment. It is also possible that teachers who develop positive perceptions of students are more likely to interact positively, effectively, and supportively, forming closer relationships and increasing students’ psychological adjustment. In turn, a reduction in psychological symptoms may lead to better acceptance by peers and a lower risk of victimization. Teachers may thus act as social referents. In addition, because of a teacher’s positive attitude toward a student, classmates will give a more positive evaluation, leading to a lower risk of victimization.

Limitations and future direction

The study presents some limitations. First, the cross-sectional approach adopted does not allow to draw conclusions from the perspective of causal relationships between the constructs investigated. However, if it is true that the quality of relationships can influence children’s psychological symptoms, it is also true that students’ behavioral difficulties can influence the quality of relationships with teachers. Therefore, longitudinal studies would be able to clarify any causal association between constructs. Furthermore, we only used self-report instruments, meaning that factors such as social desirability and text comprehension may intervene. Future research could employ experimental situations or third-party observers, or could integrate other assessment instruments. For example, the quality of teacher–student relationships was measured from the perspective of teachers, while future studies could consider how these relationships are perceived by students. Finally, the sample was not representative of the national population. Hence, future studies could replicate the research by considering larger and more representative samples and other cultures.

Practical implications

Finally, this study has practical implications for the educational context, as it reveals that teacher sentiments regarding physical appearance may contribute to an environment in which children are more susceptible to peer victimization. Therefore, it is important to stimulate reflection on how perceptions and stereotypes can influence relationships with students and the classroom and to highlight the mechanisms through which they predict different developmental outcomes. Finally, a reflection on the role of teacher sentiments about physical appearance could be included in training courses on bullying prevention in school contexts. Training can make teachers aware of the potential impact that their perceptions of students’ physical appearance might have on their psychological well-being and risk of victimization. In this sense, ad hoc training could help teachers develop a greater awareness of how perceptions of a student’s physical characteristics and, in particular, perceptions about physical appearance might affect the quality of their relationship with the student and, in turn, might affect the student’s psychological well-being and risk of victimization. It is possible, therefore, that teachers may become more aware of how their perceptions about the student may affect the student’s psychological adjustment and, in this direction, seek to foster a better relationship with their students that is less tied to interpretive bias.

From a theoretical perspective, this study encourages further research on how teachers’ sentiments regarding students’ physical appearance may affect the quality of the teacher–student relationship, students’ psychological adjustment, and the risk of bullying victimization. In a broader context, this study offers valuable insights into the role of the teacher–student relationship in predicting favorable student developmental outcomes and seeks to expand our understanding of the underlying mechanisms linking the teacher–student relationship to the risk of student victimization.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Turin, protocol no. 118643. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

CL conceived and designed the study. MF performed the literature search and study selection process. SM performed the final analysis process. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alias, R., Ismail, M. H., and Sahiddan, N. (2015). A measurement model for leadership skills using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 172, 717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.424

Bahia, S., Freire, I., Amaral, A., and Teresa Estrela, M. (2013). The emotional dimension of teaching in a group of Portuguese teachers. Teachers Teach. 19, 275–292. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2012.754160

Baker, J. A., Grant, S., and Morlock, L. (2008). The teacher–student relationship as a developmental context for children with internalizing or externalizing behavior problems. Sch. Psychol. Q. 23, 3–15. doi: 10.1037/1045-3830.23.1.3

Black, N., and de New, S. C. (2020). Short, heavy and underrated? Teacher assessment biases by children’s body size. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 82, 961–987. doi: 10.1111/obes.12370

Clifford, M. M., and Walster, E. (1973). The effect of physical attractiveness on teacher expectations. Sociol. Educ. 46, 248–258. doi: 10.2307/2112099

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd). New York: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Cook, B. G., and Cameron, D. L. (2010). Inclusive teachers’ concern and rejection toward their students: Investigating the validity of ratings and comparing student groups. Remedial and Special Education, 31, 67–76. doi: 10.1177/0741932508324402

Denessen, E., Keller, A., van der Bergh, L., and van der Broek, P. (2020). Do teachers treat their students differently? An observational study on teacher–student interactions as a function of teacher expectations and student achievement. Educ. Res. Int. 2020:2471956. doi: 10.1155/2020/2471956

Dusek, J. B., and Joseph, G. (1983). The bases of teacher expectancies: a meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 75, 327–346. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.75.3.327

Elledge, L. C., Elledge, A. R., Newgent, R. A., and Cavell, T. A. (2016). Social risk and peer victimization in elementary school children: the protective role of teacher–student relationships. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 44, 691–703. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0074-z

Fabris, M. A., Badenes-Ribera, L., and Longobardi, C. (2021). Bullying victimization and muscle dysmorphic disorder in Italian adolescents: the mediating role of attachment to peers. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 120:105720. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105720

Fabris, M. A., Badenes-Ribera, L., Longobardi, C., Demuru, A., Dawid Konrad, Ś., and Settanni, M. (2020). Homophobic bullying victimization and muscle dysmorphic concerns in men having sex with men: the mediating role of paranoid ideation. Curr. Psychol. 41, 3577–3584. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00857-3

Farmer, T. W., Lines, M. M., and Hamm, J. V. (2011). Revealing the invisible hand: the role of teachers in children’s peer experiences. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 32, 247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.04.006

Ferraris, N., and Persico, D. (2019). Structure of the Italian school system. World yearbook of education 1990: Assessment & Evaluation. London: Routledge.

Ferrer-Esteban, G. (2011). Beyond the traditional territorial divide in the Italian education system: Effects of system management factors on performance in lower secondary school. Turin: Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli.

Fitzpatrick, C., Blair, C., and Côté-Lussier, C. (2016). Dressed and groomed for success in elementary school: student appearance and academic adjustment. Elem. Sch. J. 117, 30–45. doi: 10.1086/687753

Fraire, M., Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Sclavo, E., and Settanni, M. (2013). Examining the student–teacher relationship scale in the Italian context: a factorial validity study. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 11, 851–882. doi: 10.14204/ejrep.31.13105

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 38, 581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Hamre, B. K., and Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher–child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Dev. 72, 625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Publications.

Hendrickx, M. M., Mainhard, M. T., Boor-Klip, H. J., Cillessen, A. H., and Brekelmans, M. (2016). Social dynamics in the classroom: teacher support and conflict and the peer ecology. Teach. Teach. Educ. 53, 30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.10.004

Hughes, J. N., Cavell, T. A., and Willson, V. (2001). Further support for the developmental significance of the quality of the teacher–student relationship. J. Sch. Psychol. 39, 289–301. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(01)00074-7

Kenealy, P., Frude, N., and Shaw, W. (1988). Influence of children’s physical attractiveness on teacher expectations. J. Soc. Psychol. 128, 373–383. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1988.9713754

Koenig, A. M. (2018). Comparing prescriptive and descriptive gender stereotypes about children, adults, and the elderly. Front. Psychol. 9:1086. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01086

Lin, S., Fabris, M. A., and Longobardi, C. (2022). Closeness in student–teacher relationships and students’ psychological well-being: the mediating role of hope. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 30, 44–53. doi: 10.1177/10634266211013756

Longobardi, C., Ferrigno, S., Gullotta, G., Jungert, T., Thornberg, R., and Marengo, D. (2021a). The links between students’ relationships with teachers, likeability among peers, and bullying victimization: the intervening role of teacher responsiveness. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 37, 489–506. doi: 10.1007/s10212-021-00535-3

Longobardi, C., Lin, S., and Fabris, M. A. (2022). Daytime sleepiness and prosocial behaviors in kindergarten: the mediating role of student–teacher relationships quality. Front. Educ. 7:710557. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.710557

Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., and Settanni, M. (2017). School violence in two Mediterranean countries: Italy and Albania. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 82, 254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.037

Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., and Settanni, M. (2019a). Violence in school: an investigation of physical, psychological, and sexual victimization reported by Italian adolescents. J. Sch. Violence 18, 49–61. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2017.1387128

Longobardi, C., Settanni, M., Lin, S., and Fabris, M. A. (2021b). Student–teacher relationship quality and prosocial behaviour: the mediating role of academic achievement and a positive attitude towards school. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 91:12378. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12378

Longobardi, C., Settanni, M., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., and Marengo, D. (2019b). Students’ psychological adjustment in normative school transitions from kindergarten to high school: investigating the role of teacher–student relationship quality. Front. Psychol. 10:1238. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01238

López, V., Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., Ascorra, P., and González, L. (2020). Teachers victimizing students: contributions of student-to-teacher victimization, peer victimization, school safety, and school climate in Chile. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 90:432. doi: 10.1037/ort0000445

Lorenz, G. (2021). Subtle discrimination: do stereotypes among teachers trigger bias in their expectations and widen ethnic achievement gaps? Soc. Psychol. Educ. 24, 537–571. doi: 10.1007/s11218-021-09615-0

Marengo, D., Fabris, M. A., Prino, L. E., Settanni, M., and Longobardi, C. (2021). Student–teacher conflict moderates the link between students’ social status in the classroom and involvement in bullying behaviors and exposure to peer victimization. J. Adolesc. 87, 86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.01.005

Marengo, D., Jungert, T., Iotti, N. O., Settanni, M., Thornberg, R., and Longobardi, C. (2018). Conflictual student–teacher relationship, emotional and behavioral problems, prosocial behavior, and their associations with bullies, victims, and bullies/victims. Educ. Psychol. 38, 1201–1217. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2018.1481199

Marengo, D., Settanni, M., Longobardi, C., and Fabris, M. (2022). The representation of bullying in Italian primary school children: a mixed-method study comparing drawing and interview data and their association with self-report involvement in bullying events. Front. Psychol. 13:862711. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.862711

Marsh, H. W., Nagengast, B., Morin, A. J. S., Parada, R. H., Craven, R. G., and Hamilton, L. R. (2011). Construct validity of the multidimensional structure of bullying and victimization: an application of exploratory structural equation modeling. J. Educ. Psychol. 103, 701–732. doi: 10.1037/a0024122

Matteucci, M. C., and Farrell, P. T. (2019). School psychologists in the Italian education system: a mixed-methods study of a district in northern Italy. Int. J. School Educ. Psychol. 7, 240–252. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2018.1443858

Mohammad, S. M., and Turney, P. D. (2013). NRC emotion lexicon. Natl. Res. Counc. 2:234. doi: 10.4224/21270984

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., and Harris, T. (1999). Beliefs and attitudes about obesity among teachers and school health care providers working with adolescents. J. Nutr. Educ. 31, 3–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3182(99)70378-X

Olweus, D., and Limber, S. P. (2010). Bullying in school: evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus bullying prevention program. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 80, 124–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01015.x

Pallini, S., Vecchio, G. M., Baiocco, R., Schneider, B. H., and Laghi, F. (2019). Student–teacher relationships and attention problems in school-aged children: the mediating role of emotion regulation. Sch. Ment. Heal. 11, 309–320. doi: 10.1007/s12310-018-9286-z

Pianta, R. (2001). Student–teacher relationship scale. Professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. Available at: http://curry.virginia.edu/uploads/resourceLibrary/STRS_Professional_Manual.pdf

Pit-ten Cate, I. M., and Glock, S. (2019). Teachers’ implicit attitudes toward students from different social groups: a meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 10:2832. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02832

Prino, L. E., Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., Parada, R. H., and Settanni, M. (2019). Effects of bullying victimization on internalizing and externalizing symptoms: the mediating role of alexithymia. J. Child Fam. Stud. 28, 2586–2593. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01484-8

Prino, L. E., Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., and Settanni, M. (2023). Attachment behaviors toward teachers and social preference in preschool children. Early Educ. Dev. 34, 806–822. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2022.2085980

Quaglia, R., Gastaldi, F. G., Prino, L. E., Pasta, T., and Longobardi, C. (2013). The children–teacher relationship and gender differences in primary school. Open Psychol. J. 6, 69–75. doi: 10.2174/1874350101306010069

Rist, R. C. (1970). Student social class and teacher expectations: the self-fulfilling prophecy in ghetto education. Harv. Educ. Rev. 40, 411–451. doi: 10.17763/haer.40.3.h0m026p670k618q3

Rist, R. C. (2000). HER classic reprint – student social class and teacher expectations: the self-fulfilling prophecy in ghetto education. Harv. Educ. Rev. 70, 257–302. doi: 10.17763/haer.70.3.1k0624l6102u2725

Ritts, V., Patterson, M. L., and Tubbs, M. E. (1992). Expectations, impressions, and judgments of physically attractive students: a review. Rev. Educ. Res. 62, 413–426. doi: 10.3102/00346543062004413

Rodgers, R. F., Campagna, J., and Attawala, R. (2019). Stereotypes of physical attractiveness and social influences: the heritage and vision of Dr Thomas Cash. Body Image 31, 273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.01.010

Rosenthal, R., and Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom: teacher expectations and student intellectual development. United States of America: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Rubie-Davies, C. M., Weinstein, R. S., Huang, F. L., Gregory, A., Cowan, P. A., and Cowan, C. P. (2014). Successive teacher expectation effects across the early school years. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35, 181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2014.03.006

Sabol, T. J., and Pianta, R. C. (2012). Recent trends in research on teacher–child relationships. Attach Hum. Dev. 14, 213–231. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2012.672262

Schoeler, T., Duncan, L., Cecil, C. M., Ploubidis, G. B., and Pingault, J.-B. (2018). Quasi-experimental evidence on short-and long-term consequences of bullying victimization: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 144, 1229–1246. doi: 10.1037/bul0000171

Shepherd, M. A. (2011). Effects of ethnicity and gender on teachers’ evaluation of students’ spoken responses. Urban Educ. 46, 1011–1028. doi: 10.1177/0042085911400325

Silva, K. M., Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., Sulik, M. J., Valiente, C., and Huerta, S. (2011). Relations of children’s effortful control and teacher–child relationship quality to school attitudes in a low-income sample. Early Educ. Dev. 22, 434–460. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2011.578046

Stroebe, W. (2020). Student evaluations of teaching encourages poor teaching and contributes to grade inflation: a theoretical and empirical analysis. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 42, 276–294. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2020.1756817

Tobisch, A., and Dresel, M. (2017). Negatively or positively biased? Dependencies of teachers’ judgments and expectations based on students’ ethnic and social backgrounds. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 20, 731–752. doi: 10.1007/s11218-017-9392-z

Upadyaya, K., and Eccles, J. (2015). Do teachers’ perceptions of children’s math and reading related ability and effort predict children’s self-concept of ability in math and reading? Educ. Psychol. 35, 110–127. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2014.915927

Vekiri, I. (2010). Boys’ and girls’ ICT beliefs: Do teachers matter?. Computers & Education, 55, 16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2009.11.013

Verschueren, K., and Koomen, H. M. (2012). Teacher–child relationships from an attachment perspective. Attach Hum. Dev. 14, 205–211. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2012.672260

Wang, C., Swearer, S. M., Lembeck, P., Collins, A., and Berry, B. (2015). Teachers matter: an examination of student–teacher relationships, attitudes toward bullying, and bullying behavior. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 31, 219–238. doi: 10.1080/15377903.2015.1056923

Wang, S., Rubie-Davies, C. M., and Meissel, K. (2018). A systematic review of the teacher expectation literature over the past 30 years. Educ. Res. Eval. 24, 124–179. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2018.1548798

Woolley, M. E., Strutchens, M., Gilbert, M. C., and Martin, W. G. (2010). Mathematics success of Black middle school students: Direct and indirect effects of teacher expectations and reform practices. Negro Educational Review, 61:41.

Keywords: teacher sentiment, bullying victimization, psychological adjustment, student–teacher relationships, physical appearance

Citation: Longobardi C, Mastrokoukou S and Fabris MA (2023) Teacher sentiments about physical appearance and risk of bullying victimization: the mediating role of quality of student–teacher relationships and psychological adjustment. Front. Educ. 8:1211403. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1211403

Edited by:

Ali Derakhshan, Golestan University, IranReviewed by:

Luis J. Martín-Antón, University of Valladolid, SpainAthanasios Gregoriadis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Anastasia Vatou, International Hellenic University, Greece

Copyright © 2023 Longobardi, Mastrokoukou and Fabris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sofia Mastrokoukou, c29maWEubWFzdHJva291a291QHVuaXRvLml0

Claudio Longobardi

Claudio Longobardi Sofia Mastrokoukou

Sofia Mastrokoukou Matteo A. Fabris

Matteo A. Fabris