- Department of Human Science, University of Verona, Verona, Italy

Faculty Development, in the last decades, has undergone many transformations and many scholars are now wondering what will be the main feature that will characterize the next age, an age distinguished, in the academic world, by the changes that the just experienced pandemic brought with it. One of the main changes that this pandemic has brought with itself is the increase in digitalization within academic institutions and, consequently, the increase in the number of faculty development proposals that are conveyed through online initiatives. However, this is a consideration that can be read not only as a stand-alone element but also, if properly contextualized, it could be used as a way to promote Faculty Development programs that exploit the potential offered by digitalization in order to create initiatives which are linked in a mutually reinforcing bond. This choice is consistent with the adherence to a holistic approach to Faculty Development that promotes a systemic and multifocal logic. This paper presents a study conducted at the University of Verona in order to discover if the Faculty Development programs here implemented applying this approach were been able to promote a reciprocal mirroring between them. In order to answer this question, it was considered useful to investigate the results of a survey carried out on the “Competenze Trasversali” program, in its first edition, and thus still in an “experimental” phase. In order to collect the data has been used a simplified version of SWOT Analysis was used and the answers to the open questions were analyzed using the content analysis.

1. Faculty development for the next ages

Mary Deane Sorcinelli (Sorcinelli et al., 2006; Sorcinelli, 2020) has presented an evolution of the concept of Faculty Development organized for “Ages” according to which (a) the 60s were “The Age of Scholar” in which the primary purpose of Faculty Development was to support faculty members in the development of their academic skills within their disciplines; (b) the 70s were “The Age of Teacher” in which academic institutions focused their attention on the development of their staff’s teaching skills; (c) the 80s were “The Age of Developer” in which the role of faculty developers was officially recognized; (d) the 90s were “The Age of the Learner” in which more and more programs of Faculty Development were focused on promoting a more autonomous and active learning process (also through the spread of digital technologies supporting learning); (e) the beginning of the 21st century was “The Age of the Network” in which, even through the use of digital platforms, academic institutions all over the world started an enriching confrontation about their Faculty Development experiences; (f) the years between 2010 and 2020 were “The Age of Evidence” in which universities addressed the problem of the effectiveness of their interventions, also in connection with the stakeholders’ needs (Sorcinelli et al., 2006; Beach et al., 2016; Sorcinelli, 2020).

And what about the next Age, the one that now stands before us and has presented itself with the business card of a pandemic that has upset the entire globe’s life and habits? What will it be like? Some scholars believe that it will be “the Age of Global Community” (Baker and Lutz, 2021, p.62), interpreting as a distinctive element of the new decade the possibility for universities to share their Faculty Development actions beyond the local dimension, thanks to the massive spread of digital tools.

This is already a refreshing perspective, but perhaps it is possible to take a step further, considering digitalization as something which is not only able to support an “international” comparison, but also which is also an essential element in the development of an internal process of “positive reinforcement.” More precisely, academic institutions can use digital tools to promote specific FD actions, thus promoting also the “vision” of the academic development that surrounds them. This undoubtedly allows several academic institutions to be aware of what is happening in the other universities within the international panorama, thus leading to the promotion of an “external” globalization. But at the same time, this also allows the different actors involved in the same academic organization to be aware of what “is going on” within their own institution, therefore, promoting an “internal” globalization. According to this perspective, digital tools can be used not only as a way to “conduct” Faculty Development actions or promote them among other institutions, but they can also be employed to spread among the faculty members a shared culture that embodies the principles of faculty development not as simple “suggestions,” but also as pillars around which to build the sense of one’s professional actions. For this to happen, however, digital tools must be put at the service of a precise vision of Faculty Development, in which the core is the desire to involve all those who belong to the academic institution in a common project. Hence, in order to reach this goal, what is needed to be put in place is a holistic approach to Faculty Development.

The initial assumption, from which the holistic approach starts, is the idea (certainly not new) according to which it is not possible to “split” the development of an individual into separated areas. From the point of view of the Faculty Development, this concept was initially considered simply as an exhortation to plan the development actions that would be implemented by faculty members who were called into question starting from all their competencies, both professional and personal as well as “political” (understood as those skills necessary to actively participate in the flourishing of the academic institution to which they belong). Only later, this approach was extended to a “broader” look, grasping the potential not only of an “integrated” training that would enhance the awareness of the own “multiple” soul in the university teacher, leading him/her to invest in different competencies that compose it, but also of an emphasis placed on the systemic nature of the entire academic context (Sutherland, 2018).

Indeed, the holistic approach argues that it is not possible to affect academic culture (an indispensable element to be able to affect university practices) except through a series of linked actions, which are part of a common design, aimed at “involving” faculty members all around. The aim is to bring the university teacher to see him/herself as an element of a complex ecosystem in which he/she is part of a whole. Faculty members must therefore come to perceive themselves not as a cog in a huge mechanism over which they have no control, but as a living being within an ecosystem, in which their actions simultaneously foresee different causes and effects, and are inserted in a rhizomatic way within a network of multiple interconnections. Only in this way, it is possible for him/her to build a new universe of meanings in which he/she can find a profound meaning for each of the occurrences that see him/her called to action within the institution (Stensaker et al., 2017; Sutherland, 2018).

Starting from these suggestions, Faculty Development actions should follow a systemic and multifocal logic according to which they should not be considered as “single initiatives,” organized in a “sectionalized way,” but as connected initiatives according to a principle of mutual reinforcement. In this way, acting at different levels but consistently, it is possible to promote a “flexible” development, capable of rethinking itself even in unforeseen solicitations. In such a perspective, digital tools can represent an essential resource because they allow to emphasize their multi-perspective soul, both by creating opportunities for exchange and comparison and allowing a modular and integrated management of the initiatives.

Furthermore, the holistic approach, starting from the ecological thinking of Bronfenbrenner (1979), identifies three organizational levels, namely micro, meso and macro: it is evident that, from an operational point of view, most of Faculty Development’s actions are oriented one toward the other of these levels. However, individual initiatives should maintain a contact that allows them to promote an organic growth of the individual teacher (micro level), of the groups of individuals belonging to the same organizational unit (meso) and of the academic organization as a whole (macro; Hannah and Lester, 2009; Roxå and Mårtensson, 2012; Simmons, 2020; Dorner and Mårtensson, 2021).

Hence, this means that it is necessary to be aware of the reciprocal influences within the FD programs even if they are focused on different organizational levels and, for this reason, these FD programs need to be “integrated” in the same “framework,” thus linking them to a bigger, strategic aim. From an operational point of view, this means, for example, that the Faculty Development intervention should be organized with the aim to enhance the individual faculty members, such as a training intervention aimed at improving the design skills of the involved teachers, acting on a “micro” level. But it is also possible to think of an intervention that has as its purpose the introduction of a specific innovative teaching strategy within a course of study: in this case the objective is both the professional development of the individual teacher and the raising in the quality of the course of study, placing itself at a meso level. This does not mean, however, that there are no links between these two actions and consequently between these two levels. Indeed, these links are intrinsic to the very nature of the context in which they are inserted, which is systemic by its nature. Therefore, it becomes essential to be aware of these reciprocal influences and focus on them upstream, inserting them within a project of overall meaning.

Therefore, this Faculty Development approach provides interesting stimuli to promote an action planning that consciously fits into the complex and multifocal dimension of academic institutions, starting from the specificities of a challenging contemporary context and contemporary debate. However, these indications may appear to be poorly defined from a programmatic point of view and require a specific effort to be translated into application. Now we can see a practical application of the holistic approach and then derive indications to model it for a more “transversal use.”

2. An experience at the Verona University

A concrete example of what is here described, is represented by two FD actions promoted by the University Teaching and Learning Center (TaLC) of Verona University, one dedicated to teachers (“Formarsi per Formare”) and one dedicated to students (“Competenze Trasversali”).

The “Formarsi per Formare” program is an initiative aimed to develop faculty members’ teaching skills. It is structured into different activities: some meetings are seminars focused on specific contents (for example a teaching strategy, a lesson design model, or also a teaching innovation experience conducted by a colleague) aimed to promote, among the participants, a discussion about the topic in order to reflect on its possible implication in their own teaching. Others are workshop paths, each of them organized into three or four different meetings with a more action-oriented purpose. Their aim is usually to deepen a specific topic connected to academic teaching by providing the participants with the tools needed to connect these elements with their actions. All the meetings are online and synchronously conducted, but they are also registered and available to the staff through intranet. Furthermore, the materials that aim at communicating to faculty members the objective of the program as well as its organizational logic and potential, are disseminated through intranet. In particular, it is highlighted how the program is intended as an action aimed at promoting didactic innovation with specific reference to the dissemination of active teaching strategies. Finally, although potentially open to all University teachers, the program is specifically organized and promoted with reference to new hires.

The “Competenze Trasversali” program promotes training courses open to all Verona University’s students, aimed to support their development from a personal, professional, and civic point of view. Starting from the framework “Life skills for Europe,” the courses are organized into nine areas and propose skill-based courses connected to relevant issues in students’ daily life (i.e., “Positive conflict management”), sometimes related to topical issues (i.e., “Intercultural communication”). The courses are held in digital mode (mainly but not exclusively in synchronous) and use an e-learning platform (Moodle) for the management of the moments of comparison or assessment activities required for the certification of the acquired skills. In this case, the information is disseminated both through the page dedicated to the project, which has a specific section within the web space of the Teaching and Learning Center, and through Moodle. All the courses are conducted online and the teachers are able to choose among the synchronous mode (carrying out the interventions through the University web conference tool, or Zoom), the asynchronous mode (through the Panopto platform, integrated, in the University of Verona, with Zoom and Moodle), or the “mixed mode” that intertwines synchronous and asynchronous activities. Even in this case, the structure of the project as well as its objective are conveyed in order to promote useful skills in the students both from a personal and professional point of view, without neglecting the dimension of civic engagement. To define the set of courses that will be proposed to the students before the start of each semester, TaLC submits to the teachers a call for proposals in which they are invited to elaborate a project aimed at the development of a specific life skill, starting from a format provided by the Center. The stimulus that is given to teachers is to devise a training experience that promotes life skills by targeting one of the areas proposed in the format, starting from a crucial, or in any case debated, topic which can involve all the students (for example the energy sources of the future for the Environmental area or Cybersecurity for the Digital area).

Teaching and Learning Center provides support for the definition of the project ideas and, downstream of the call process, analyzes each one of them suggesting, if necessary, a recalibration action to make the proposal better adhere to the project framework. Each course has a responsible teacher, who is the proponent, but he/she can make use of the collaboration of other teachers inside the University (often belonging to different disciplinary areas) as well as of external experts. For each course, TaLC also provides for the implementation of a specific Moodle space, giving support, where necessary, even in the management phase.

After the courses have been defined, TaLC organizes an overall calendar that takes into account all the activities, in order to avoid internal overlap, publishing the calendar on a dedicated page where the overall framework in which the program is inserted is further recalled as well as its general objectives. In the same online space, the administrative indications that regulate the program are also specified and, for each course, there are included a brief description and a summary information sheet that lists the teacher or the teachers involved, the main focus, the program, the calendar, the teaching methods and the assessment tools as well as a link to the specific Moodle space. The page also contains references to the TaLC team and in particular to the teaching tutor assigned to the project. Once this space has been prepared, direct communications are sent to all the students through the University app, which refers to the dedicated web page. At the same time, the request to disseminate the initiative to their students is sent to the Departments’ offices of the University.

At the end of each course, the students must undergo an end-of-course assessment with the aim to verify the achievement of the objectives of expected learning, in terms of skills. The modalities to carry out this evaluation action are decided autonomously by each teacher, however, as mentioned, the TaLC offers support to the teachers in order to harmonize the evaluation phase with the project’s global objectives. Finally, once the courses have been completed and the assessments collected, the administrative staff of TaLC will liaise with the Departments’ Offices and with the IT Department in order to insert micro-credential in the student’s career.

Although they are two separate programs, they have essential elements of continuity within them. Firstly, they are two connected axes of the “UNIVR per l’innovazione didattica—2021-2023” project (valid for the University Triennial Programming), promoting a vision of FD in which the enrichment of both teachers and students represents two sides of the same coin, each one essential to support the growth of University. In fact, on closer inspection, even if the focuses of the two programs are apparently different and located at two different organizational levels (“Formarsi per Formare” is mainly placed at a meso level by virtue of its specific focus on new hires, while the program “Competenze trasversali” is placed at a micro level because it aims at the development of the individual students involved in the project) they are closely related. “Formarsi per Formare” has, as underlined, the purpose to promote didactic innovation with particular reference to the diffusion of active learning, but we know that active learning does not only improve the students’ academic skills but also their life skills, establishing a direct link with the “Competenze trasversali” project.

Secondly, “Formarsi per Formare” is both a formative moment and the starting point for a stronger relationship between the teachers of the University and the staff of the TaLC. Indeed, in many cases, the teachers who attended “Formarsi per Formare” decided to be actively committed in promoting teaching innovation by choosing to dedicate part of their time to design and implement a course belonging to the program “Competenze Trasversali,” therefore putting into action what they have learned about teaching innovation at the service of all the students of the University and taking advantage of this opportunity as a professional challenge. In a more general sense, we can say that both programs are linked to a single transversal objective, namely to promote a more student-oriented university education within the University of Verona.

Furthermore, the way in which digital tools have been used to unite the projects is not only a tool to conduct activities and certify the acquired skills (for both experiences, the certification through micro-credentials are foreseen: this certification is already activated for the “Competenze Trasversali” project, while it will be activated from 2022/2023 for “Formarsi per Formare”), but it also is a tool to communicate to the involved subjects the global dimension within which the initiatives were inserted.

Hence, these two projects, even if they have “their own life,” are part of a wider framework that, thanks to their mutual positive interactions, promotes a systemic vision of FD at the University of Verona, according to which the growth of the institution is the result of the growth of individuals, within a harmonious and articulated environment.

3. To analyze in order to optimize

3.1. The data and the methodological framework

The two projects presented here are part of a design that refers to the holistic approach of Faculty Development: consequently, they should have highlighted, albeit starting from different organizational levels, reciprocal connections and links to a common framework, promoting what has been here referred to as “internal globalization.” But did this really happen? In order to answer this question, it was considered useful to investigate the results of a survey carried out on the “Competenze Trasversali” program, in its first edition, and thus still in an “experimental” phase, which required specific attention in order to identify those elements on which to act for its optimization. The decision to analyze the feedback of the students who participated in the “Competenze Trasversali” program, and not the ones of the teachers who participated in the “Formarsi per Formare” program is not accidental. The idea behind this choice is that teachers, as they are faculty members and therefore more involved in the political and organizational life of the University, can be more aware of the global framework toward which the Faculty Development initiatives are deliberately placed. On the other side, both due to their role and the transitory nature of their experience within the academic institution, students can grasp the logic that underlies the various initiatives with greater difficulty. This is why, for the purpose of this paper, it is particularly interesting to investigate their point of view.

Indeed, the program started in the academic year 2020/2021 (the same year in which the “Formarsi per Formare” path was inaugurated in a structural way), and was composed of 32 courses and saw the participation of 3,510 students. At the end of the first year of the project (which took place during the academic year 2020/2021), it was decided to carry out a follow-up activity in order to investigate students’ experience, with the aim to identify its characteristics and use the collected insights to optimize the route. The follow-up was carried out in September 2021 by means of a survey (including both open and closed questions) conducted through the Lime Survey platform arranged for the sending of the link to some students who participated in the project in the academic year 2020/2021. More specifically, the request to participate has been sent to students who have attended a selection of courses conducted in the first semester in the 2020/2021 academic year. Being a follow-up, this choice was made so that the participants had definitively completed the experience. The request was sent to a total of 1,558 students. Of these, 778 completed the survey only in the part concerning closed questions, while 244 decided to complete also the part concerning open (optional) questions. Here, consistent with the purpose of this paper, the focus will be on the students who answered the open-ended questions. Although the data are not statistically representative of the population, all the reposted responses were considered. The open questions were intended to investigate the students’ experience and asked them in particular to identify the specificities of the path, suggesting both strengths and areas for improvement.

Indeed, in order to collect the data an open-answer survey, organized into four main questions (preceded by some profiling questions) inspired by SWOT Analysis, was designed. SWOT Analysis is a strategic planning method, which was developed at the Stanford Research Institute in the 1960s. Its purpose is to analyze the performance of specific programs or services in order to hypothesize changes that can improve their effectiveness. In order to do this, it focuses its attention on the strengths of a specific experience (Strengths); on its weak points (Weaknesses); on its opportunities for improvement (Opportunities), and on the risks it faces (Threats; Hill and Westbrook, 1997). In the last 2 decades, this tool has become more and more popular within academic institutions thanks to its capability to evaluate an academic program and identify its possible areas of development without reducing its complexity to a minimum common denominator and without using excessively standardized products, which would inevitably fail to capture its specificity. This is possible because it connects a focused gaze with the possibility, for the ones involved in the survey, to express their opinion in a wide and open way, thus highlighting unexpected needs and allowing a strategic development perspective (Gordon et al., 2000; Panagiotou, 2003; Helmes and Nixon, 2010; Leiber et al., 2018; Safonov et al., 2021).

In this case, a simplified version of SWOT Analysis was used with two questions focused on Strengths and Weaknesses. However, weaknesses, in accordance with the transformative vision that animates the project, were defined as something more than “something lacking”: indeed, the second question has been focused on the identification of the “Areas for improvement.” This is because, in this way, what was under the light were not the mere “gaps,” but the necessary actions to remedy them. Then, a third question asked to the students to specify what kind of courses they would consider useful to be implemented in the next edition of the program, another useful element for the optimization of the program itself. All of these choices were made within the framework offered by the concept of developmental evaluation, according to which evaluation should be a fluid process that must define its tools and procedures consistently with its essential aim, which is not simply to identify the critical areas, but to pinpoint the optimization actions needed by the program submitted to analysis (Patton, 2006, 2016).

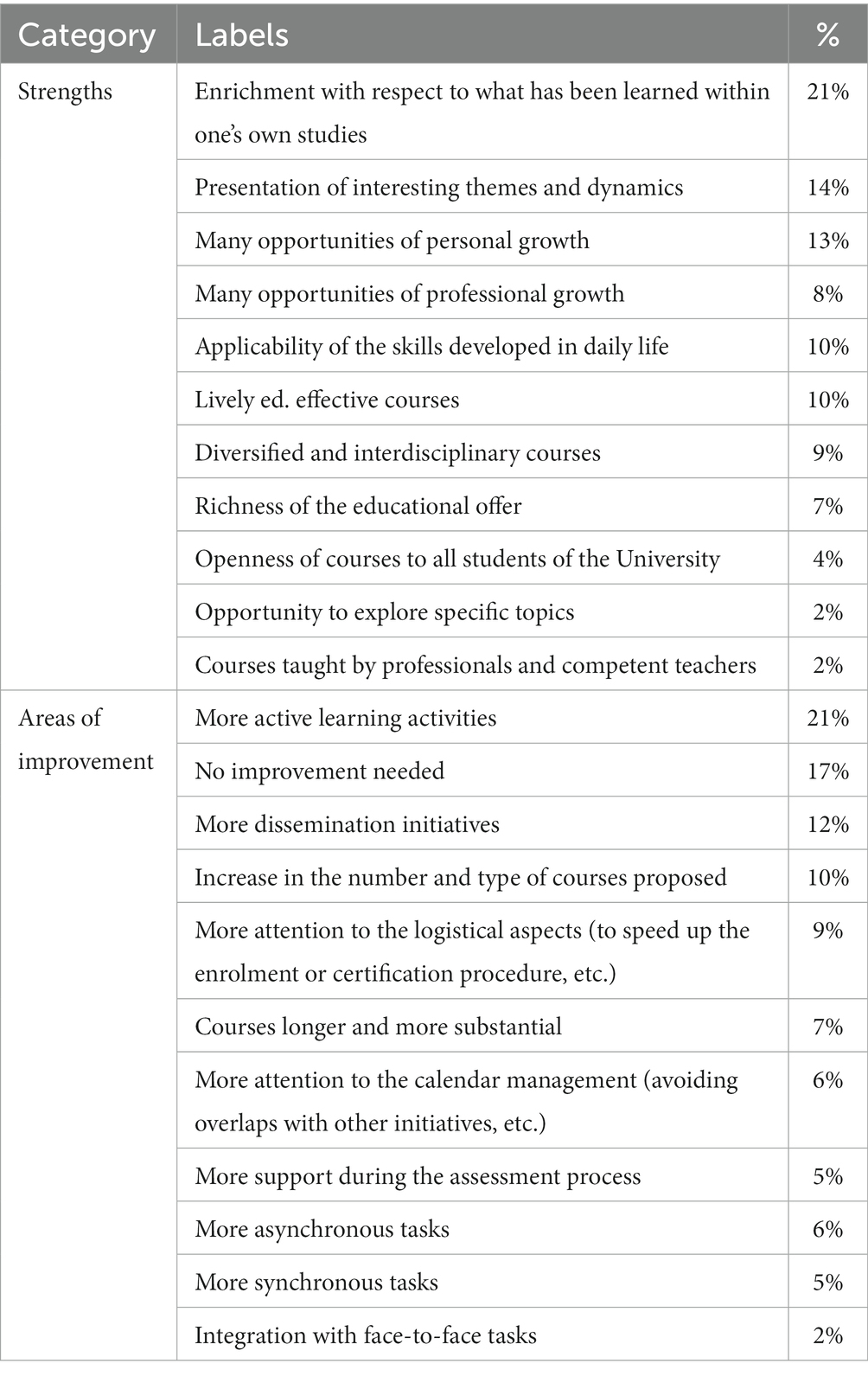

The answers to the open questions were analyzed using the content analysis, by virtue of its flexibility and ability to guide the data analysis process toward a progressive definition and systematization of its salient elements, allowing to synthesize the core elements without for this losing its nuances (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Ramirez-Montoya et al., 2017). Besides, the inductive content analysis emphasizes, as stated by the name itself, the inductive element by acting on the basis of the principles of identification and clustering of the significant elements and allowing the creation of a coding system that can have different levels of abstraction (Smith, 2000; Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). In this case, consistently with the tool used to collect the data, the analysis of the open questions has produced a coding organized in two main categories (Strengths and Areas of improvement), and within each of these areas the main features were identified through an inductive analysis (Hsiehm and Shannon, 2005; White and Marsh, 2006; Elo and Kyngäs, 2008), while the answers to the third question were analyzed through a separate process in order to identify the areas which should be implemented.

3.2. The analysis

The content analysis carried out on the feedback provided by the students made it possible to develop the coding presented below, which identifies the elements that emerged as “strengths” and as “areas for improvement.” In order to give a more in-depth reading, the frequencies with which these labels emerged from the data are also reported, expressed in terms of percentages.

This analysis allowed us to identify important elements useful for the redesign of the program, understanding which aspects needed to be consolidated and which ones, instead, needed corrective actions. Nevertheless, besides this, this analysis can also lead us to understand whether the inclusion of the “Competenze Trasversali” program in a broader framework, in close relationship with the initiatives aimed at teachers (“Formarsi per Formare” program), also allows accomplishing another step. Indeed, the heuristic action here performed also allows us to understand whether from the data emerge elements which are capable to verify the effectiveness of the approach in which they fit, i.e., the holistic approach to Faculty Development, which led to the design of the “Competenze Trasversali” program with specific attention to the elements of coherence between this project and the other Faculty Development actions promoted by the Teaching and Learning Center (as the “Formarsi per Formare” program, which in a certain sense constitutes its counterpart.)

First of all, starting from the strengths, we can see that even if the elements specified by students are different (“Enrichment with respect to what has been learned within one’s own studies,” “Applicability of the skills developed in daily life,” etc.) many of them focus attention on a same aspect, which is the multiformity of the different courses belonging to the program (“Many opportunities of personal growth,” “Many opportunities of professional growth,” “Diversified and interdisciplinary courses,” and Richness of the educational offer”). This lead to affirm that this multiformity of the program was explicitly recognized by the students as an element capable of helping them to go beyond their own experience, sometimes even seeing “usual” issues from different points of view.

"[The strength of the program is] the possibility of choosing courses that do not necessarily have to do with one's own course of study, [which] allows you to get out of your" bubble "by participating in experiences that are radically different from those you can be accustomed" (Int. 183).

"[A strong point is] the integration of different fields of knowledge, the possibility of learning about topics that cannot be easily defined in a particular area" (Int. 78).

In these extracts, students highlight the importance to integrate the specialist knowledge they develop within their own study paths with insights and reflections deriving from other disciplinary areas. The fact that students recognize the positive value of this interaction is significant, first of all because it reveals how they are aware that such mixtures are essential for the formation of a well-rounded member of our society, who possesses robust professional training but also has the necessary knowledge and skills to be an equipped and responsible individual and citizen. Secondly, these reflections show a positive consciousness of how the interaction among different disciplinary areas leads to mutual enrichment, laying the foundations for a second interdisciplinary look that also enriches professional training.

Nevertheless, at the same time, from the students’ answers the awareness also emerged of the presence of a unique “matrix” that surrounds the whole Program.

"The strong point [is…] the construction of the project itself which allows you to try out various types of paths linked together" (Int. 113).

"The strength [is…] the transversality but also the diversity of the courses [offered by the program]" (Int. 27).

“[A strong point is] the integration of different fields of knowledge” (In. 78)

The fact that, albeit in an unfocused way, we can find in the students’ answers traces of awareness of what we could call “unity in multiformity” is significant, because it makes evident how the construction of a shared framework in which the activities are inserted and the effort to communicate the presence of this framework to the students has been perceived by the recipients of the program, even if the presentation of the common logics underlying the project needs to be further emphasized. In other words, students are telling us that they can “see” the architecture underlying the program, which combines the wealth of training offers with a clear general logic that “links” these courses, so different from each other, through a common “matrix.” The realization of this goal owes much to the possibilities provided by digital tools. Central is the use of a learning platform, global but capable to support a wide differentiation and offer support to extremely diversified learning activities. This is an embodiment of the use of digitalization as a way to reach “unity in diversity,” concretely promoting a shared vision of learning and teaching among the faculty members.

A second important aspect concerns the enhancement of active learning experiences: students explicitly indicated the use of active teaching methodologies within the course as the strong point of the project. As pointed out, although this was not mandatory within the program, teachers were encouraged to use what they had learned in the “Formarsi per Formare” course within the courses belonging to the “Competenze trasversali” Program. In the students’ answers, there are clear references to this teaching choice, which was valued by the course participants as one of the strengths of the Program (“Innovative topics and teaching strategies”).

“[The strong point is] the didactic [modality], the possibility of actively participating and being able to share personal experiences” (Int. 125).

"The interactivity between students and teacher and between students is also excellent" (In. 196).

This shows how the students of these courses are aware of how the teachers’ use of active learning methodologies has facilitated the acquisition of knowledge and skills that were outside their area of expertise. It also shows how the active and participatory dimension has been an important element to support the students’ motivation in attending these courses. Obviously, not all the teachers involved in the project were equally able to implement active teaching strategies, however, the fact that this aspect is a relevant element for the students is reiterated, through a sort of “cross-check,” by some labels belonging to the area dedicated to the improvement points, since some students explicitly ask to increase the interactive dimension (“More active learning activities”).

"[A suggestion would be to] make the course more interactive"—(Int. 254).

“Use examples closer to reality”—Int. 143.

“More exercises”—Int. 117.

The fact that students can “see” the role of the teaching choices aimed at promoting greater interactivity and their consequent active participation in teaching activities is certainly an element in favor of the positive link between the two programs promoted by the TaLC. At the same time, the students’ request to increase this aspect in the courses that have introduced it only in a minority, represents an element that makes us understand how active learning is considered by the students themselves to be particularly effective in promoting life skills. A link of reciprocal influence is therefore clearly outlined between the “Formarsi per Formare” and the “Competenze Trasversali “programs. In fact, on the one hand, teachers are able to effectively put to good use what they have learned in the training course dedicated to them, therefore putting themselves to the test in particularly challenging courses (both for the type of users that these courses collect, given that they are open to all University students without distinction of the course of study, and for the innovativeness of the project itself, which is placed in an extracurricular dimension). On the other hand, students themselves, thanks to these experiences, become aware of the potential of a teaching approach that sees them more empowered but also more active, through their participation in their own learning process. Also, in this case the use of the digital dimension has been functional in consolidating this bond. In particular, since both programs are conducted using digital tools, this has allowed teachers to “experience” the same tools from two different perspectives (as teachers and as learners), thus promoting a more multifocal vision of them as well as a more aware and shrewder use of them.

Lastly, a final element that emerged from the analysis of the data and which appears to be linked to our initial focus, albeit in a less direct way than the previous two, concerns the dissemination of the initiative. Although not in large numbers, some excerpts, indeed, highlighted the need to give greater visibility to the initiative:

"[The courses] could be more widespread" (Int. 116).

"[The program] should be more publicized" (Int. 140).

However, this is not just a “practical problem,” it is an essential aspect within an initiative that makes the communication through digital tools a characterizing element of its structure. If on one hand, indeed, the communication that took place was sufficient to make several students aware of the presence of a global framework to which the activities referred (as highlighted above), on the other, however, the need was felt to push even more on the dissemination of the initiative and make more “present” within the panorama of our university, not only the very existence of the initiative but above all the sense that supports it. This aspect is instead essential, especially with respect to the starting point of this paper, which is the desire to increase the “internal globalization” of the university in relation to Faculty Development issues because digital tools can support not only moments of dissemination but also of comparison and shared reflection. If we start from this perspective, the dissemination of the initiative is not simply an element functional to its “popularity”: actually, as regards this aspect we could safely conclude that the problem did not arise, because the Program “Competenze Trasversali,” at its debut, involved 3,510 students out of 25,533 students enrolled in the University of Verona (almost 14% of the enrolled students). The problem here is wider: if the choice made here was to use the holistic approach to Faculty Development as a tool to support the development of linked initiatives, capable of placing themselves in a logic of “mutual reinforcement” while supporting the confrontation on these issues within the university, the fact that the students claimed greater dissemination of the initiative is both good and bad news. It is good news because it means that the action aimed at stimulating a greater “liveliness” of the internal debate has reached the students, making them aware of the need to improve the communication that the university addresses to itself and its members. It is bad news because (as was to be expected) if an important step has been taken toward the right direction, many are still those to be taken in order to reach the final goal.

In the end, the results of the analysis show that: (a) students appreciated the diversification of the training experiences, but they are also aware of the presence of a global framework surrounding them; (b) they particularly appreciated those teachers who used active learning and ask for more experiences connected to this approach; and (c) finally, they think that the program deserves an even more “strong” diffusion across the university. What does this tell us about our starting point? What was presented here was the choice to organize the Faculty Development activities using the holistic approach as a keystone that aims at promoting a systemic and multifocal logic. The digitalization of these programs has made it possible to emphasize this link because it has embodied a way to reach “unity in diversity” which is essential for the fulfillment of this goal. Hence, the systemic vision that is at the basis of these programs and their realization through digital tools emerged from this analysis as elements fruitful connected one to another. Their connection led to the implementation of Faculty Development actions in which the presence of a global framework clearly appears, putting in evidence the presence of the reciprocal influences among the different Faculty Development programs and, at the same time, it also increased the awareness about the importance of promoting a confrontation among academic institutions, emphasizing that the internal globalization is a goal that deserves to be reached.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, what emerges here is the idea that the FD should understand its mission as the embodiment of multifaceted, prismatic actions, which, despite their being composed of different “sides,” are, nonetheless, capable of establishing among them important points of contact and mutual influence. From an operational point of view, the different Faculty Development actions should be designed “upstream” posing specific attention to these “points of contact” which represent the cornerstones from which the design starts. Only in this way, the different programs can be connected providing mutual reinforcement and linking the objectives of the different actions together so that one is not only coherent but also functional to the realization of the other. If properly designed, even programs that refer to different organizational levels can be integrated into a setting where the individual objectives are linked to a broader and more transversal global framework, aimed at an articulated but harmonious growth of the institution. This choice obviously presents complexities from an organizational point of view, as it requires a complex effort, and can be made possible only by a fully structured Faculty Development Center supported by the university governance. However, if the need from which we are starting will bring a real and lasting change in the institution, the effort to maximize the effectiveness of the interventions is worth to be taken.1 The role that digital tools can play in this horizon is on a double level: on one hand, nowadays they are a management instrument that is an integral part of the learning and teaching actions of Higher Education and, if used in a conscious way, they can multiply the possibilities to personalize the teaching activity, promoting that flexibility and multifocality able to reach “unity in diversity.” On the other hand, they can be used as a method of “dissemination” of the Faculty Development programs of the University with the aim to support the “internal globalization” to which reference has been made. To achieve this purpose, it is necessary that they are used in a coherent and integrated way and at the same time that they specifically convey the existence of those “points of contact” to which reference has been made, that is, the link among the different Faculty Development programs, by putting in the spotlight the existence of the “positive reinforcements” that bind them. In this way, digital tools would become “sounding boards” for the holistic approach that inspires Faculty Development actions and could support a process of change capable of recognizing and embracing the systemic dimension of the academic institution.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study are subject to the following licenses/restrictions: the data used for this article are owned by the Teaching and Learning Center of the University of Verona and were collected in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the Faculty Development programs promoted by the Center. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to cm9iZXJ0YS5zaWx2YUB1bml2ci5pdA==.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

Heartfelt acknowledgments to all the members of the Teaching and Learning Center, with particular reference to the Director of the Center, Luigina Mortari, and to my colleague Alessia Bevilacqua.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In this regard, it is worth noting that, consistently with the developmental approach (Patton, 2006, 2016), the conducted analysis was also used as a starting point to optimize Faculty Development initiatives. This led, for example, in the academic years 2021/2022 and 2022/2023 to the introduction of training courses and workshops included in the “Formarsi per Formare” program dedicated to active learning.

References

Baker, V. L., and Lutz, C. (2021). Faculty development post COVID-19: a cross-Atlantic conversation and call to action. J. Professoriate 12, 55–79.

Beach, A. L., Sorcinelli, M. D., Austin, A. E., and Rivard, J. K. (2016). Faculty Development in the Age of Evidence: Current Practices, Future Imperatives. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dorner, H., and Mårtensson, K. (2021). Catalysing pedagogical change in the university ecosystem: exploring ‘big ideas’ that drive faculty development. Hung. Educ. Res. J. 11, 225–229. doi: 10.1556/063.2021.00089

Elo, S., and Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 62, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Gordon, J., Hazlett, C., Ten Cate, O., Mann, K., Kilminster, S., Prince, K., et al. (2000). Strategic planning in medical education: enhancing the learning environment for students in clinical settings. Med. Educ. 34, 841–850. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00759.x

Hannah, S. T., and Lester, P. B. (2009). A multilevel approach to building and leading learning organizations. Leadersh. Q. 20, 34–48. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.11.003

Helmes, M. M., and Nixon, J. (2010). Exploring SWOT analysis–where are we now? A review of academic research from the last decade. J. Strateg. Manag. 3, 215–251. doi: 10.1108/17554251011064837

Hill, T., and Westbrook, R. (1997). SWOT analysis: it's time for a product recall. Long Range Plan. 30, 46–52. doi: 10.1016/S0024-6301(96)00095-7

Hsiehm, H. F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Leiber, T., Stensaker, B., and Harvey, L. C. (2018). Bridging theory and practice of impact evaluation of quality management in higher education institutions: a SWOT analysis. Eur. J. High. Educ. 8, 351–365. doi: 10.1080/21568235.2018.1474782

Panagiotou, G. (2003). Bringing SWOT into focus. Bus. Strateg. Rev. 14, 8–10. doi: 10.1111/1467-8616.00253

Patton, M. Q. (2016). What is essential in developmental evaluation? On integrity, fidelity, adultery, abstinence, impotence, long-term commitment, integrity, and sensitivity in implementing evaluation models. Am. J. Eval. 37, 250–265. doi: 10.1177/1098214015626295

Ramirez-Montoya, M. S., Mena, J., and Rodríguez-Arroyo, J. A. (2017). In-service teachers’ self-perceptions of digital competence and OER use as determined by a xMOOC training course. Comput. Hum. Behav. 77, 356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.09.010

Roxå, T., and Mårtensson, K. (2012). “How effects from teacher-training of academic teachers propagate into the meso level and beyond” in Teacher Development in Higher Education (New York, NY: Routledge), 221–241.

Safonov, M. S, and Usov, S., & Arkhipov S, V . (2021). “E-learning application effectiveness in higher education. General research based on SWOT analysis” in Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Education and Multimedia Technology. 207–212.

Simmons, N. (2020). The 4M framework as analytic lens for SoTL’s impact: a study of seven scholars. Teach. Learn. Inquiry 8, 76–90. doi: 10.20343/teachlearninqu.8.1.6

Smith, C. (2000). “Content analysis and narrative analysis” in Handbook of Research Methods in Social and Personality Psychology. eds. H. T. Reis, H. T. Reis, and C. M. Judd (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 313–335.

Sorcinelli, M. D. (2020). “Fosteting 21st century teaching and learning: new models for faculty professional development” in Faculty Development in Italia: Valorizzazione Delle Competenze Didattiche Dei Docenti Universitari. eds. A. Lotti and P. A. Lampugnani (Genova: Genova University Press), 19–27.

Sorcinelli, M. D., Austin, A. E., Eddy, P. L., and Beach, A. L. (2006). Creating the Future of Faculty Development: Learning From the Past, Understanding the Present, vol. 59. Genova: Jossey-Bass.

Stensaker, B., Bilbow, G. T., Breslow, L., and Van der Vaart, R. (2017). “Strategic challenges in the development of teaching and learning in research-intensive universities” in Strengthening Teaching and Learning in Research Universities: Strategies and Initiatives for Institutional Change (Springer) 1–18.

Sutherland, K. A. (2018). Holistic academic development: is it time to think more broadly about the academic development project? Int. J. Acad. Dev. 23, 261–273. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2018.1524571

Keywords: faculty development, holistic approach, higher education, faculty development programs, effectiveness’ evaluation

Citation: Silva R (2023) Digitalization as a way to promote the holistic approach to faculty development: a developmental evaluation. Front. Educ. 8:1204697. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1204697

Edited by:

Laura Sara Agrati, University of Bergamo, ItalyReviewed by:

Roberto Trinchero, University of Turin, ItalyMaura Pilotti, Prince Mohammad bin Fahd University, Saudi Arabia

Luis Carlos Jaume, University of Buenos Aires, Argentina

Natanael Karjanto, Sungkyunkwan University, Republic of Korea

Copyright © 2023 Silva. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Roberta Silva, cm9iZXJ0YS5zaWx2YUB1bml2ci5pdA==

Roberta Silva

Roberta Silva