- Centre for Evaluation, Quality and Inspection, Institute of Education, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

This study aims to explore the perspectives of school inspectors and leaders on the quality of school inspection in four countries with different inspection systems: Dubai, Ireland, New Zealand, and Pakistan. The study also examines the general perceptions of school leaders and inspectors about the impact of quality assurance agencies on teaching and learning in these countries. Using semi-structured interviews of school leaders (n = 28) and inspectors (n = 14), the research found that school leaders’ experiences and perceptions of school inspection and evaluation were varied in and across all four countries. While some expressed dissatisfaction with the inspectors and the process, others regarded it as a beneficial endeavor that instilled a sense of vigilance and attentiveness toward the quality standards and inspection criteria. School leaders’ experiences and perceptions were mostly positive in Dubai and mixed in the cases of Ireland, New Zealand and Pakistan. Furthermore, the study found a negative correlation between the perception of school leaders and inspectors regarding the quality of inspection practices and their perception of the impact of inspection. Thus, it is imperative to establish improved avenues of communication to facilitate heightened awareness among school leaders regarding the efficacy of inspectors’ work and the comprehensive measures implemented by inspectorates to ensure the quality of their own practices. This initiative will foster enhanced trust between school leaders and inspectors, consequently amplifying the overall influence of school inspections.

1. Introduction

The process of appraising and assuring the quality of education provision exists as school inspection or evaluation in most of the education regimes across the globe (Penninckx et al., 2016; Hofer et al., 2020). Although there is considerable variability in the processes used to hold schools accountable for the quality of education, external evaluation through school inspection is a predominant method of measuring education quality in Europe and the Pacific regions, as noted by Behnke and Steins (2017). Similarly, in several Asian countries influenced by British or European systems, school inspection serves as a major instrument of quality assurance (Gardezi et al., 2023). The growth of school inspection over the past two decades can be attributed to various social, political, and economic factors. According to Gardezi et al. (2023), these factors include the economic crisis of 2008, the adoption of new management policies and neoliberalism, the comparative evaluation of education systems such as the Program of International Student Assessment (PISA), the result-based approach of transnational funding agencies like the World Bank, EU, and UNICEF, and the local socio-political contexts of countries. The economic crisis prompted countries to invest in human capital and monitor the development of future citizens (Brown et al., 2016a). Neoliberal and New Public Management approaches decentralized control and granted schools autonomy, while paradoxically leading to the implementation of stringent governance measures, including school inspection and standardized examinations, to maintain educational quality (Brown et al., 2016b). Funding agencies require rigorous monitoring systems to track ongoing progress as a prerequisite for releasing funds for education-related initiatives (Malik and Rose, 2015) For example, the revival of the school monitoring system in Pakistan is an outcome of such initiatives. In countries like Ireland and Dubai, performance in PISA serves as a driving factor (The United Arab Emirates, 2015; Brown et al., 2017).

Whatever the driver, school inspection or external evaluation has become a popular mechanism of quality assurance (determining what is good and what should be improved) and quality improvement (providing inspiration for how things can be improved) in education (Mac Ruairc, 2019). Hossain (2018) argues that it is a core institutional mechanism to assess the quality of education and according to Gustafsson et al. (2015), it holds schools accountable for a broad range of goals related to the quality of student achievement, teaching organization and leadership (p. 47). Elsewhere school inspection is also defined as an activity meant to collect information about the quality of schools, check compliance with legislation and evaluate the quality of teaching and learning (Eddy-Spicer et al., 2016, p. 16). The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has repeatedly stressed the importance of effective school inspection in its publications. Such inspections provide schools with crucial feedback to improve their practices and drive change, shaping schools’ decision-making processes and leading to continuous improvement in student learning (OECD, 2022).

Similarly, the mission statement of the inspectorate of Northern Ireland encapsulates the typical quality claim of many inspectorates as providing ‘an unbiased, independent, professional assessment of the quality of learning and teaching, including the standards achieved by learners’ (The Education and Training Inspectorate, 2022, para. 3). Commitment to quality reverberates not only in the definition and mission statements but also in all the documents published online or in print pertaining to school inspection or evaluation across the globe.

Although several studies establish a direct link between school inspection and national education policy (see, for example, Altrichter and Kemethofer, 2015; Baxter, 2017), which is intended to assure and promote the effectiveness and quality of an education system at the system-level, there are also studies that highlight unintended consequences of school inspections, both, as it were, philosophical/ political and practical. The former tend to suggest that accountability systems come from a right wing worldview, are demeaning of professional autonomy and thus tend to de professionalize schools and teachers, while the latter focus on unintended consequences at the school level. In the case of the former the extent of the debate precludes a detailed treatment in a paper of this length. Suffice it to say that such criticisms have had a definite impact in challenging high stakes forms of school inspection in the minority of countries where they exist but have largely failed to stem the rising ubiquity of inspection as a moderate tool of school governance and control and a mechanism for improvement in many countries (Thrupp, 2006; Ozga and Lawn, 2014; McNamara et al., 2022).

The unintended consequences at school level include practices like window dressing, fabrication of documentation, and playing the game, which stem from accountability pressure (De Wolf and Janssens, 2007; Ehren et al., 2016; Penninckx et al., 2016; Penninckx, 2017). However, other studies present external pressure exerted through school inspection as a stimulus for positive change in schools (Perryman, 2010; Van Bruggen, 2010; Altrichter and Kemethofer, 2015). To achieve quality improvement in schools through school inspection, it is crucial for well qualified professionals to provide quality feedback and recommendations for improvement. The perceptions of school leaders regarding the quality of school inspectors play a vital role in the acceptance of feedback and its successful implementation in practice.

School inspection, as can be seen, is an appraisal of the quality of the overall performance of schools, but to be an appraiser, one needs to have requisite skills, qualifications, qualities and thorough knowledge of inspection procedures to conduct the review. Furthermore, the acceptance of the outcome of the appraisal depends largely on the appraisee’s perceptions of the appraiser’s quality and the credibility of the process (Reidy, 2022). This paper maps out these notions of appraisal onto the school inspection systems and quality assurance measures of the inspectorates and the perceptions of school leaders in four countries across the globe: Dubai, Ireland, New Zealand and Pakistan. The study also aims to examine the general perceptions of school leaders and inspectors about the impact of quality assurance agencies on teaching and learning, using semi-structured interviews with both groups in these countries. It is an altogether novel aspect as generally, empirical studies on school inspection focus on the effects of school inspection (De Wolf and Janssens, 2007; Ehren et al., 2015; Penninckx et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2017), the role of school self-evaluation in external evaluation (MacBeath, 2006; McNamara et al., 2011; Chapman and Sammons, 2013; Brown et al., 2017; McNamara et al., 2022) or school inspectors’ roles and responsibilities (Baxter, 2017; Baxter and Hult, 2017; Penninckx and Vanhoof, 2017). It is essential to know that in Dubai and Ireland, this institution is called inspection; in New Zealand, evaluation, while in Pakistan, it is called monitoring and supervision. Lexically, the terms may be different, but in the context of these countries, these terms refer to quality assurance procedures.

These inspection systems were deliberately selected for they vary widely in terms of their approaches and procedures. While each system is unique in how it organizes inspections, the ultimate goal remains the same: to ensure quality of education. For instance, the Dubai Inspection Bureau adopts a strict regime that rewards or sanctions schools based on their inspection outcomes, whereas the Irish inspection systems does not grade schools or follow up with return cycles. Instead, it only provides reports on what is working well and what needs improvement in a school. In Pakistan, monitoring and supervision involve frequent visits to schools with real-time data collection and high-level data review. Conversely, the new approach to school evaluation in New Zealand is more of an oversight of self-evaluation rather than external evaluation (Gardezi et al., 2023). Unlike other studies that include the viewpoint of either school leaders or school inspectors, the present study investigates both the perspectives and opinions of school inspectors and leaders on the quality of school inspection, within the context of these diverse case studies. The research aims to address the following questions:

• What do inspectorates do to ensure the quality of their practices and procedures?

• What are the general perceptions of school leaders about the quality of inspection practices and inspectors?

• Is there a gap between the perceptions of school leaders regarding the quality of inspection and those of the school inspectors themselves?

This paper begins by providing an overview of quality measures that the inspectorates undertake in these four countries to manage their own quality and establish their credibility based on an exploration of their official documents, website and literature. This is followed by an account of the methods employed to carry out this research and the analysis of the perceptions of school leaders and inspectors of the quality of school inspection. A critical discussion on the gaps in how school inspection is perceived and experienced by those who inspect and others who are inspected concludes this paper.

1.1. An overview of quality assurance practices of inspectorates in Dubai, Ireland, New Zealand, and Pakistan

School inspection, evaluation or monitoring, as it is called in these case study countries, is a well-established practice. In the case of Ireland, New Zealand and Pakistan, school inspection dates back to the nineteenth century, while in Dubai, it is a little over a decade old (Gardezi et al., 2023). In Dubai, the quality assurance agency is called Dubai School Inspection Bureau (DSIB); in Ireland, the Inspectorate and in New Zealand, the Education Review Office (ERO). While in Pakistan, there are two parallel systems within the Department of School Education in all four provinces1: one led by the District Education Authority2 (supervision and monitoring) and the other the Monitoring and Implementation Unit (monitoring and data collection). These systems and the various positions that comprise them have slightly different nomenclature in the four provinces, but to avoid thickened expression, we have used the taxonomy of the largest province, Punjab. All these systems (Dubai, Ireland, New Zealand, and Pakistan) are essentially different concerning how school evaluation activity is organized and managed even though the focus remains on the quality of education provision. On the basis of the initial review of the literature and document analysis, including the official websites, the quality assurance practices of these agencies are studied and reported under the following themes: Inspectors’ selection criteria, induction and professional development, quality of inspection practices, quality framework and other supporting documents and the quality assurance of the inspection systems.

1.1.1. Dubai

The Knowledge and Human Development Authority (KHDA) and its subsidiary Dubai School Inspection Bureau (DSIB) have several internal mechanisms for assuring the quality of their practices and procedures. Their quality assurance process begins with the recruitment of school inspectors. All inspectors must have teaching and school leadership experience, some knowledge of assessment data analysis and report writing together with other professional competencies such as communication, problem solving and conflict resolution skills. On induction, the novice inspectors receive training based on their skills through mentoring and shadowing a senior inspector. Inspectors are also given extensive orientation on the software system that the inspectors use, the school inspection framework and processes (Knowledge and Human Development Authority, 2018). The inspectors also have opportunities for professional support while liaising with the other experts on the teams.

The school inspection framework lays the foundations of the quality and standards that the inspectorate expects schools to achieve and guides inspectors’ work. The framework also outlines the code of conduct for the inspectors and schools during the inspection. Every inspection team has a quality assurance inspector who reviews and checks the reliability of judgments and any issues relating to the code of conduct while onsite (Dubai Schools Inspection Bureau, 2010). Additionally, KHDA, at any time, may review the quality of an inspection and the outcomes. This quality assurance review involves a small team of inspectors visiting a school after the school-based part of the inspection (Knowledge and Human Development Authority, 2014, p. 11). Every attempt is made to ensure transparency at all stages of the school inspection process and the inspection outcome (Knowledge and Human Development Authority, 2014). School inspection reports are published on the KHDA website and are accessible to the general public. Schools that achieve a good inspection grade are allowed to increase their fee by a certain percentage (Gardezi et al., 2023).

1.1.2. Ireland

The Irish Inspectorate is privileged to be one of the long-established inspectorates in Europe, and historically school inspectors in Ireland were held in high esteem with the title used for them, ‘cigire’ implying awe and respect (Brown et al., 2018). In continuation of that tradition, school inspectors’ selection criteria are quite stringent even today. The applicants for the post of school inspector must have a first or second-class honors degree, some experience in teaching, school leadership, school support services, curriculum design and/or assessment practices and education research (Government of Ireland, 2022). The Inspectorate has developed comprehensive training, induction and mentoring programs to build up and maintain evaluation expertise among serving inspectors. As a part of their long-term professional development, the inspectorate funds inspectors’ post-graduate study and research related to the work of the Inspectorate (Hislop, 2022, p. 75). Also, inspectors are encouraged to attend or participate in International Conferences (Coolahan and Donovan, 2009).

The Department of Education Inspectorate (DEI) (2022a,b), with the aid of guides to school inspection and quality framework, Looking at Our School (Department of Education Inspectorate, 2022c,d), provides guidelines about the inspectors’ work (pre-, while and post-inspection). The functions of the school inspectorate are also stated in the Education Act 1998 Section 13. The DEI has recently published a revised code of practice that includes general principles and standards, which guide the inspector’s work besides serving as a benchmark to assess the quality of their professional practice (Department of Education Inspectorate, 2022e). The school evaluation procedures in Ireland are subject to national audits, according to Perry (2013). The DEI invites external experts to review aspects of their work, for instance, the Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI) in Northern Ireland was invited to review the inspectorate’s work in the School Excellence Fund, Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools (DEIS) scheme and the e-Hub project (Hislop, 2022).

As mentioned in the Guide to School Inspection, the school inspection report published on the DEI website follows definitive steps and quality checks, starting from verbal feedback to the school management team and the first draft of the report sent to the school for factual verification right through until its confirmation by the school. There is also a documented review procedure in case a teacher, board of management of a school, practitioner, manager, or owner of an education center is dissatisfied with an aspect of the inspection or with the inspection report (Department of Education Inspectorate, 2022f). The DEI takes all these measures to ensure that the evaluation of educational provision is conducted in a fair, consistent, and transparent manner.

1.1.3. New Zealand

The Education Review Officers now also called the Evaluation Partners3 are recruited for the quality of their judgments, their analytical skills, knowledge of the curriculum, oral and written communication skills, and their ability to effectively relate to others (Education Review Office, 2021a). Since 1992 within the ERO corporate office, development centers for the assessment and training of reviewers have been established (French, 2000). Simons (2013) during her visit to the ERO regional offices observed that a large number of reviewers had completed an evaluation Diploma and were familiar with various theories and methods of evaluation. Some were in transition from teacher and adviser to the evaluator role. Prior to joining the ERO, they all have substantial experience in teaching and school management (Education Review Office, 2021b). The Education Review Officer Position Statement (Education Review Office, 2021a) clearly defines the role specifications, responsibilities, and individual and team profiles of the reviewers. Additionally, the ERO evaluation capabilities framework (Education Review Office, 2021c), Code of Conduct (Education Review Office, 2021d) and Principles of Practice (Education Review Office, 2021e) outline the expected level of professionalism that an evaluation partner should demonstrate during high-quality evaluations and assure the transparency in the evaluation processes.

Quite similar to Ireland, the ERO publishes several supporting documents to steer the school evaluation process. Along with the framework of School Evaluation Indicators: Effective Practice for Improvement and Learner Success, schools are provided with, Guidelines for Board Assurance Statement and Self-audit Checklists (BAS), Education Now4 and A Framework of School Improvement. The evaluation indicators explain the processes and practices that contribute to the school’s effectiveness and improvement, the BAS assists schools to be aware of and meet their legal obligations while the framework of school improvement enables the schools to mark their journey toward improvement during the evaluation cycle (Education Review Office, 2016, 2022a,b). On the ERO website, a number of other research-based publications are available for schools, for instance, National Reports, to consult and learn about the best practices in the area.

In the recently introduced collaborative evaluation approach, there are several key stages during the three-year evaluation cycle. At the conclusion of each key stage, a short summary report will be prepared, which will contribute to the final report. All reports are prepared collaboratively with the school involved (Goodrick, 2020). The ERO’s work is regularly reviewed by external evaluators. In 2018, the Tomorrow’s School Independent Taskforce conducted a review that led to the transformation of the ERO’s approach to school inspection, resulting in the current low-stakes collaborative process that is now being utilized.

1.1.4. Pakistan

In all four provinces, on induction, the school-monitoring staff are provided with an android tablet, which has a school-monitoring App connected with the Education Management Information System (EMIS) and the monitoring units’ websites to record and report real-time data about schools. Each Monitoring and Evaluation Assistant (MEA) undergoes an orientation session on the data-collection application, followed by a mentorship arrangement with a senior colleague who provides guidance on data collection procedures during school visits and appropriate conduct when interacting with school personnel. Except for Punjab, where MEAs are often retired Junior Commissioned Army Officers (Munawar et al., 2020), school monitoring staff can be fresh graduates and are recruited through the Public Service Commission5 of the respective province. They are responsible for collecting information on the given set of indicators.6 As far as the second stream is concerned, recently the selection criteria for the Assistant Education Officer (AEO) were revised. According to the job postings, the incumbent must have a master’s degree; they have to take a written test followed by an interview to qualify for the position. In most cases, they must have some teaching experience. In Punjab, besides orientation of the role and responsibilities, the AEOs are trained for lesson observation, giving feedback to teachers and coaching and mentoring [Punjab Education Sector Reforms Program (PESRP), 2020a].

Despite a joint framework for minimum standards of quality available on the website of the Federal Ministry of Education (MOFEPT), every province has its own set of indicators to monitor and evaluate schools (Ministry of Federal Education and Training, Government of Pakistan, 2017; Punjab Education Sector Reforms Program, 2020b). Generally, the User Guides for the school monitoring staff or documents or circulars pertaining to school evaluation are not available on the websites of the departments of education. However, among the quality indicators for which MEAs gather data, one pertains to the frequency of visits conducted by officials from the education department (School Education Department, 2017; Punjab Education Sector Reforms Program, 2020b). It is a part of the quality assurance mechanism to record the professional support visits by the District Education Officers (DEO), Deputy DEO and AEO of schools. Higher authorities such as the Education Department at the provincial Secretariat, Directorate of Education (Schools) and divisional Directors or CEO’s access and view these EMIS dashboards and are constantly aware of what is happening at schools. Likewise, the MEAs’ monthly visits are documented and recorded in the EMIS. During these visits, the Global Positioning System (GPS) data of the school is downloaded, which serves as a means of verifying that the MEA has actually visited the school. This helps ensure the accuracy and authenticity of the MEA’s visitation records (School Education Department [GoB], 2017). The real-time school monitoring information enables education officials to make immediate and informed decisions and address any situation based on the key findings [School Education Department (Government of Baluchistan), 2022]. Additionally, the User Guides of the monitoring system across provinces have a professional code of practice for the monitoring staff (Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhawa, 2014).

2. Methodology

This study adopted a qualitative research design and gathered data through three distinct methods: (1) analysis of official documents obtained from relevant websites, (2) a review of existing academic literature, and (3) qualitative interviews with stakeholders including school principals and school inspectors (referred to as evaluation partners in New Zealand and School Monitors and District Education Management officials in Pakistan). Among the school staff, principals were specifically selected for this study because they are the key actors in preparing the school for inspection, facilitating the inspection process when the inspection team is onsite, facing either positive or negative consequences of the inspection and implementing changes in response to the inspection (Altrichter, 2017). Principals’ interviews provided insights into their views of the inspection process and the competence of inspectors while, interviews with the members of the inspectorate were conducted to gain understanding of their approach to quality procedures and how they are implemented in practice. The sample consisted of principals (n = 28), school inspectors and inspection experts (n = 14) from the four case-study countries.

A purposeful stratified sampling technique was employed for this study. The sample was selected based on two main strata: geographical location and the level of classes taught at the school. An equal number of primary and post-primary school principals were included in the sample, with a roughly equal representation of rural and urban areas from the case-study countries with the exception of Dubai. In the case of Pakistan, school leaders from all four provinces were included in the sample.

Clearly, such small samples could not hope to be entirely representative. Therefore, a purposeful sample was chosen using the following criteria: school type, recent engagement in an inspection within the past 2 years, and having undertaken some study in this area at a Higher Education Institution (HEI), indicating knowledge and interest in this field. These criteria and respondents were identified with the help of colleagues in each country. As for the inspectors, they were identified through contacts in the education ministries or HEIs in each country.

The interviewees’ identities are anonymized by assigning them codes for the purpose of sharing their responses in the presentation and analysis section. Each interviewee is coded with a unique identifier, an alphanumeric code according to their country and position (for example, school leader and school inspector in Dubai – DBSL1 & DBSI1; Ireland – IESL1 & IESI1; New Zealand – NZSL1 & NZEP1; and Pakistan – PKSL1 & PKSI1). The first part of the code represents their country of origin and the second their position. However, due to a large number of designations of monitoring and supervisory roles in Pakistan, the code PKSI is used for all of them.

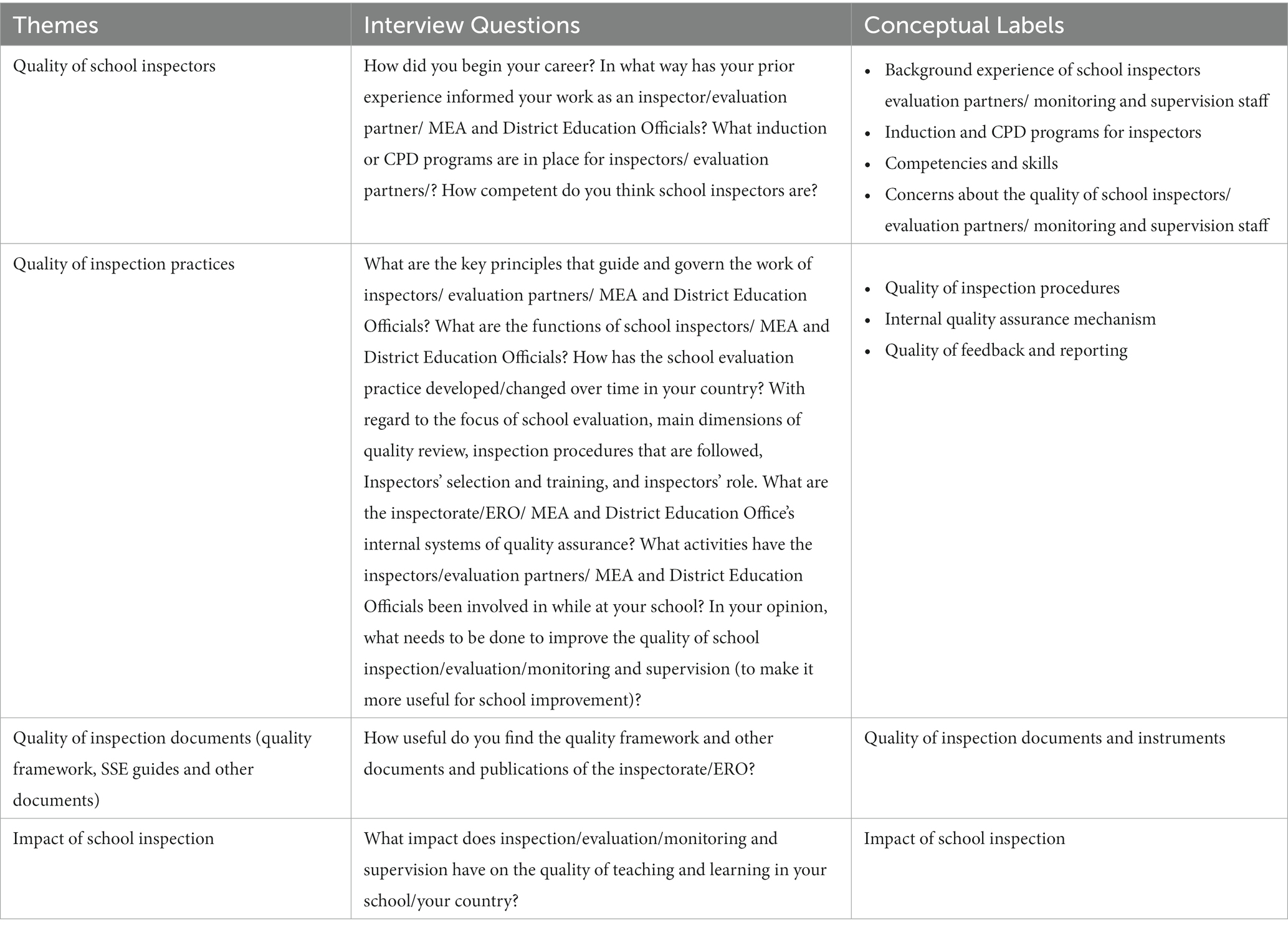

Document appraisal was guided by Scott’s (2006) selection criteria: Authenticity, Credibility, Representativeness and Meaning. All documents were accessed from the official websites of quality assurance agencies and other relevant departments, ensuring their authenticity and accurate representation of the department’s perspective. The information provided was clear and comprehensible. Document analysis was employed exclusively as a methodological approach to develop the interview protocol and to shed light on the operational procedures of school inspections, as well as the strategies implemented by these inspection systems to ensure and regulate their own quality. The academic literature, official documents and reports were reviewed and analyzed to identify the four primary themes that informed the development of the interview questions and subsequent analysis of the interview data. In total, nine sub-themes emerged from the analysis (Table 1).

Interviews with school principals, inspectors, and inspection experts were recorded and transcribed verbatim. A reflexive thematic analysis was performed using Braun and Clarke’s (2022) approach, which allows for a flexible approach and recognizes the researcher’s subjective experiences as the main instrument for interpreting and organizing data. The researcher adopted a deductive approach, following the steps including: reading and re-reading the transcripts, organizing relevant texts under the themes, reviewing and refining the themes into sub-themes and finally, using the data extracts to construct the analytic narrative. The steps were taken in sequence and each stage was based on the previous one, but the analysis was a typical recursive process and underwent several iterations.

3. Findings and results

3.1. Theme 1: quality of school inspectors/evaluation partners/monitoring and supervision staff

Most of the school inspectors we interviewed are seasoned professionals with experience spanning two or more decades, except for MEAs whose monitoring experience ranges from three to five years. Nevertheless, as stated by an MEA, the frequent visitation of 50 to 60 schools each month, coupled with the repetitive nature of their tasks, enhances their proficiency in executing their duties because their fundamental responsibility revolves around a checkbox approach, assessing the presence and functionality of essential facilities such as boundary walls, power supply, and drinking water within schools. Their role basically entails updating this information within the designated application, without necessitating extensive intellectual decision-making processes. MEAs primarily observe and document pertinent information during their visits. The school leaders also have extensive experience in their field. In the case of Dubai, some school leaders have even experienced the first KHDA inspection in 2009. One of the school leaders said, ‘I have experienced the first Inspection also but as a science head of the department, it was in 2009 and since then every year’ (DBSL1).

3.1.1. Background experience of school inspectors/evaluation partners/monitoring and supervision staff

School inspectors with an educational background can definitely have firsthand knowledge and understanding of the educational context and challenges faced by school leaders and teachers. During the onsite visit, they can comfortably engage in conversations with students, observe lessons and the overall environment of the classrooms and school. Their experience, as can be expected, enables them to make informed judgments, provide relevant feedback, and offer practical recommendations that are grounded in the realities of the classroom, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness and credibility of the inspection process (Lindgren, 2015). In the case study countries, the school inspectors, evaluators and supervisory staff interviewed had an educational background and many of them were former school principals.

Evaluation Partners from the ERO shared their prior experience, with one saying, ‘I was the principal of a secondary school before I joined the ERO,’ (NZEP3) and another saying, ‘I moved to ERO from being a teacher, head of a department and deputy principal’ (NZEP1). One of the DSIB inspectors informed the interviewer that she ‘joined the education sector as a teacher, then became a vice principal and school principal’ (DBSI1). Another inspector had a different background starting as an English teacher for middle and senior classes, then becoming the head of the department of English (DBSI2). Irish inspectors referred to their prior experience as school principals, assistant principals, educational psychologists and teacher trainers (IESI2, IESI3). A staff member from a district education office in Pakistan mentioned taking the Public Service Commission examination for BPS-16 and being inducted into Special Education – Slow Learners Institute. After 4 years, she qualified for the post of DDEO through an interview (PKSI4). Most AEOs in Pakistan were former teachers for varying lengths of time, with years of service ranging from one to five years. However, an AEO from Sindh province shared that she was directly appointed as a ‘supervisor’ for 41 small village schools (PKSI3). In contrast, the monitoring assistants had diverse backgrounds, including retired JCOs in the army, training facilitator in the Human and Social Development Centre, and teachers (PKSI1, PKSI2, PKSI5, PKSI6).

3.1.2. Induction and CPD programs for the inspectors

Professional development helps individuals to improve their skills, knowledge, and abilities so that they can perform their professional responsibilities diligently. It also refers to staying up to date on new trends within their field (Collin et al., 2012). This may include induction, which familiarizes new hires with the job expectations of their role, the work environment, and the organization’s policies. Additionally, professional development also involves on-the-job experiential learning and staying current with advancements in the field.

In all four countries, the school inspection, evaluation, monitoring and supervisory staff undergo induction and professional development throughout their career. The school inspectors from DSIB stated, ‘We have a very professional group of inspectors and a training program that prepares the inspectors for their inspections with training held annually for all inspectors’ (DBSI2). The other inspector added, ‘New inspectors do not inspect schools directly, but shadow a senior peer and receive proper training and induction before inspecting independently’ (DBSI1). The inspectors from Ireland briefed that they have an ‘Intensive induction and training period that includes in-school work monitored carefully by experienced inspectors’ and have ‘mandatory CPD multiple times per year,’ as well as receiving specialized CPD for new models and specialized inspections (IESI1). All ERO evaluation partners explained almost identical training and induction procedures for new team members. One senior evaluation partner described the induction process as follows:

‘When new evaluation partners join the team, they first observe the senior evaluation partners and their work. They familiarize themselves with the process of ERO and are attached to a seasoned evaluation partner who provides support and guidance during their induction period, which typically takes six months. As part of the induction process, the new partners are involved in the evaluation process and receive feedback on their performance’ (NZEP2).

Like in the other three countries, monitoring and supervision staff in Pakistan also receive intensive training when joining these roles. A monitoring assistant reported attending a training session with other MEAs, ‘We learned how we will collect data, conduct ourselves in schools, and interact with teachers’ (PKSI1). The district education staff, such as AEOs, informed the us that they receive a comprehensive two-month induction training covering a broad range of topics including school record-keeping, addressing out-of-school children, school environment, early childhood education, departmental rules, and administration of school funds.

3.1.3. Competencies and skills

The school leaders were asked about the quality of school inspectors, evaluation partners and the monitoring and supervision staff and they generally spoke highly of the inspectors’ professional acumen. Phrases like these came up repeatedly during the interviews when school leaders talked about inspectors’ professionalism and competencies, ‘KHDA is hiring cream from all over the world’ (DBSL1), ‘in my opinion they were first class really’ (IESL5) and ‘very experienced and extremely good at looking at the whole school’ (IESL1). ‘They’re well informed in terms of trends and things that are impacting schools at this time’ (NZSL1).

Nevertheless, these remarks were punctuated with comments such as, ‘They are experienced, but in a given situation, they could be harsh, or they could be unacceptable’ (DBSL2). Another related their competence to the repetitive nature of their work, ‘They become competent gradually as they keep doing the same tasks year after year’ (PKSL6).

3.1.4. Concerns about the quality of school inspectors/evaluation partners/monitoring and supervision staff

Though school leaders acknowledged that that school inspectors and evaluation partners are competent and skillful, they also expressed their concerns about the quality or attitude of the school inspectors. Many school leaders from Ireland and New Zealand referred to school inspectors (evaluation partners) as being teachers and lacking experience in leading schools. ‘The lady, who’s working with us, has never been a school leader. She’s been a middle leader in a large school, which is fine, and she’s done the appropriate training and has all those tools and the acuity in her bag but actually not having worked at that level, there is a risk of getting lost in bureaucracy, rather than actually focusing on the functionality of a school on a day-to-day basis’ (NZSL4). A school principal in Ireland shared a similar observation, ‘I know that a lot of the inspectors have been extremely fantastic and good teachers, but I have not met many [inspectors] who have led a school. I think there should be more principals in the inspectorate’ (IESL5). This is a very common theme and it would seem to make a great deal of sense to hire or at least second experienced school leaders to the inspectorate.

A school leader in a Dubai school spoke about inspectors’ outdated perspective on teaching and learning, ‘They’re mostly very old people, and they do not like technology. They do not understand it and they are not interested’ (DBSL5).

Most of the Pakistani school leaders interviewed complained about the fault-finding attitude of the school supervision personnel. A school leader of a rural town said, ‘If it is a rainy day, they [MEAs] will come to check the student attendance and state of cleanliness and report, but they never bother to ask how a school leader is maintaining cleanliness without cleaning staff’ (PKSL9). ‘Though some of them take an interest in teaching and learning, they visit classes and ask questions of the students to get a general impression of their learning, many merely look at the cleanliness of the school and classroom displays’ (PKSL6). One school principal, for example criticized the school supervisors for completely ignoring the ‘ground realities of schools’ (PKSL4).

With the new evaluation model in place, the school leaders in New Zealand also had several reservations and underscored the variability of competence among the evaluation partners.

‘As in any organization, there will be a bell curve shape of competence within ERO. I think there is a risk that people who do not fully understand the complexities of the art of evaluation will cause some harm and make some mistakes’ (NZSL5).

Knowing the evaluation partner as a colleague also came up as another reason for not viewing them favorably ‘ABC [name of place anonymized] is a small area and so some of the people coming into the review team you may have even worked with previously in other schools. So, unfortunately, there is that little bit of bias and prejudice that might sit in your head’ (NZSL2).

In the case of Ireland, ‘rigidity’, ‘inflexible adherence to the rules’ and ‘contextually removed from practice’ surfaced repeatedly while talking to the school leaders (IESL4, IESL3). School inspectors are criticized for not exercising independent critical thinking or personal discretion in assessing quality. They primarily function as agents of the inspection department and adhere strictly to predetermined guidelines and protocols.

These themes make a strong case for a better training and induction for incoming inspectors. Moreover, it does seem that, perhaps understandably, a determination to impose a large degree of uniformity in conducting inspection is resulting in very rigid systems, allowing inspectors little autonomy to share advice and experience.

3.2. Theme 2: quality of inspection practices and procedures

School leaders in all four countries were familiar with the onsite tasks of the school inspectors, evaluators and MEAs except for those in Pakistan, where the approach of each supervisory personnel was described as individualized and sometimes arbitrary. The frequency of inspection visits varied by country. In Dubai, schools are inspected annually; and in Pakistan, MEAs visit each school once a month and the supervisory staff twice a month. In New Zealand, the frequency of visits by the evaluation partners is negotiated between the school leader and the evaluator. However, in Ireland most of the school leaders were not aware of the inspectorate’s selection process. A school principal shared, ‘I have no idea how they decide or select a school for inspection. We just get a phone call or notification letter saying that they are coming to inspect and with the incidental inspection, they’ll just arrive on the day’(IESL3).

With the introduction of a new evaluation approach in New Zealand, both school leaders and evaluation partners expressed high expectations and spoke positively about it. They emphasized its ‘bespoke’, ‘highly differentiated’ and ‘context embedded’ nature, focusing on ‘building relationships’, and ‘developing a clear understanding of schools over time’ (NZEP1, NZEP2, NZEP4 & NZEP5). A school principal said, ‘It’s much more of a partnership model, which I think is what they are really trying to work on now. Doing [evaluation] with not doing to [school]’ (NZSL3).

In the case of Ireland, on one hand, some of the school leaders appreciated the school inspection as providing them with ‘an extra pair of eyes.’

‘I used their recommendations as a checklist for school improvement. I am very conscious of what they see. It is like when you are in something and you are there every day, you actually are so close to it that you do not really see, and they are experienced outsiders’ (IESL5).

On the other hand, some school leaders criticized the inspection practice for being ostentatious and rigid.

‘I would have no questions about their [inspectors’] competency but the model itself is what I would have questions about in that it’s just too rigid a model and it allows these very competent, very well-trained people to have no flexibility at all or no real connection with what’s happening in the classroom’ (IESL4).

School leaders, in Dubai and Ireland, also spoke about unrealistic expectations especially with regard to student achievement.

‘They need to adjust the recommendations in light of the type of school they are in. They expect the attainment should be higher than normal. They say, “You’re below normal in certain subject areas in terms of attainment in the state exams.” It depends on the socio-economic group, which we are drawing our clientele as well. There’re so many other factors coming into play and after all, somebody has to be below normal otherwise, if everyone’s above normal then the normal shifts anyway’ (IESL3).

‘KHDA pilots projects with some elite schools and then they try and test them in some other schools. Finally, they share with us that these are the best practices, which are going on in other schools. Obviously, we have to see the infrastructure and the budget of our school and do accordingly’ (DBSL1).

School inspectors, evaluation partners, and monitoring and supervision staff consistently emphasized the significance of reflective practices in enhancing their professional performance and optimizing their impact on schools. Through intentional self-assessment and critical analysis, they strive to refine their approaches, aiming to make them more advantageous and effective for the schools they serve. For instance, a DSIB inspector shared, ‘Each year, it’s a learning curve for us. We learn from what we did and how we can do things better’ (DBSI1). Similarly, an evaluation partner asserted, ‘ERO regularly reviews its’ own procedures. The change in school review methodology is one example and the updated Code of Conduct is another (NZEP1).

The MEAs agreed that they have very clearly laid out monitoring procedures that they cannot deviate from while the AEOs reported that in the absence of any prescribed course of action, they keep reviewing their practice. ‘I visit every school in my markaz7 twice a month, so during one visit I focus on administrative tasks and in the second I do lesson observation, coaching and mentoring of teachers’ (PKSI6).

Some School leaders, in New Zealand and Pakistan, articulated their worries regarding the magnitude of the work of evaluation partners and MEAs and AEOs that can affect the quality of their work. For example, each evaluation partner has to visit and facilitate the evaluation of forty schools. Every month, MEAs are responsible for visiting 50 to 60 schools to collect data, while AEOs are expected to visit the 13 schools in their assigned center (known as the Markaz) twice a month to monitor the physical environment, review the disbursement of their ‘non-salary budget’ and ‘Farogh-e-Taleem fund’ and provide coaching and mentoring to teachers.

Notable in the above is once again the issue of rigidity in approach required of the inspectors and the limitations this can impose on how much they can work closely as partners. Interestingly, the new model in NZ, which puts partnership rather than oversight at the center of the inspection engagement is being positively received and may well be the model for the future.

3.2.1. Internal quality assurance mechanisms

The school inspectors, evaluation partners, monitoring and supervision staff described a wide range of procedures to ensure quality of their practices. These measures included the establishment of digital record-keeping systems to ensure the accessibility of records for relevant individuals, including inspection managers and inspector mentors/mentees. Furthermore, regular review meetings are conducted among inspectors to foster discussions and facilitate the exchange of best practices. Additionally, inspectors are paired with seasoned colleagues who serve as mentors, offering invaluable guidance and support regarding ongoing matters. Moreover, the school inspection reports undergo a stringent system of quality assurance to uphold their accuracy and reliability.

The Irish inspectors particularly emphasized the measures they take to guarantee the quality of their work.

‘Inspection managers not just manage their local inspection teams but also participate in the team inspection to monitor the team’s working. We have a rigorous system of monitoring and quality assurance of inspection reports. Additionally, our clear frameworks, standardized templates for collection and recording of evidence and clear guidance on report writing lead to quality and consistency in practice. Within our Guidelines to school inspection there are also mentioned complaints’ processes including informal and formal appeal mechanisms, which are transparent and objective. Following WSE inspections, all teachers and principals are invited to complete an online survey and give feedback about the quality of inspection procedures and inspectors. All inspection records are regularly updated and monitored’ (IESI).

Similar systems are in place in New Zealand and Dubai inspectorates. The Dubai inspectorate distinguishes itself by implementing an inspection quality assurance team, which sets it apart from other inspectorates in this regard.

‘In addition to the inspection team, we have a separate quality assurance team to ensure the quality of inspection practices across the system. Before conducting an inspection, we do a risk assessment to anticipate potential issues. We also evaluate the composition of the team being sent to the school. If a complaint is made about the inspection at a school, the quality assurance team investigates’ (DBSI1).

Only the school leaders of Dubai schools mentioned the quality assurance measures of the inspectorate during conversations with school leaders.

‘After four years of inspection, the KHDA introduced quality assurance for their own practices, which has improved the onsite inspection practices and the behavior and attitude of the inspectors’ (DBSL1).

In Pakistan, the monitoring visits are recorded automatically by the GPS on the Tablets used by MEAs to record and submit school data, and supervisory staff visits are monitored and reported by the MEAs. However, no school leader referred to these quality assurance mechanisms reflecting their limited accessibility to this information and a lack of transparency in the quality assurance procedures.

3.2.2. Quality of feedback and reporting

School leaders across all four countries conveyed their discontentment regarding the quality of feedback and reports they received, but they also appreciated certain aspects of reporting. School leaders in Ireland, Dubai, and New Zealand shared comparable concerns, with a principal from New Zealand expressing dissatisfaction with the review reports for their lack of specificity and absence of meaningful differentiation across different schools.

‘The reviews in the past have always been incredibly bland. After the last review, I took our review report, removed our name, downloaded two other reports, removed their names, photocopied them, and gave them to our board. I asked them which one was ours, and they could not tell me’ (NZSL2).

Interviewees in Pakistan reported a lack of standardization in the sharing of monitoring reports by MEAs with the school or uploading it directly into the EMIS. Some MEAs discuss the report with school leaders but most do not. Supervisory staff write their remarks in the school’s visitor log and ‘a written lesson observation report that includes a way forward is handed over to the teacher observed’ (PKSI6). Most school leaders voiced displeasure about the rushed and perfunctory visits of the supervisory staff excluding AEOs. A principal in the metropolis describes the process,

‘After their visit, they document their comments in our logbook. They often make positive remarks, such as praising the high level of cleanliness in my school. If there are any concerns, they provide suggestions for improvement, which I believe is just a formality’ (PKSL6).

However, school leaders in Ireland appreciate that school inspections do not involve grading or ranking of schools, as is the case in high-stakes inspections. This relieves schools of the stress associated with achieving specific grades (e.g., IESL1).

Some school leaders in both Dubai and Ireland expressed genuine interest in the inspection feedback and findings. An Irish school leader stated, ‘The WSE-MLL typically has eight or ten recommendations. In response, we work on these recommendations and take them seriously in good faith’ (IESL1).

Likewise, School leaders in Dubai went a step further and appreciated the inspectors’ complete information of their previous inspections reports and acknowledged that ‘Inspectors’ feedback helped us improve our self-evaluation tremendously because when we are observed by external evaluators, we come across a critical perspective’ (DBSL5).

It is clear that the quality of feedback is a major factor in the value, or otherwise, of inspection. We can see a movement toward these reports becoming less bland and generic, and it emerges that schools and school leaders value advice and guidance, which can often provide a roadmap to improvement and provide them with a tool which can be used to move the school in a particular direction.

3.3. Theme 3: quality of tools and instruments

The school inspection framework, along with other supporting instruments such as the school self-evaluation guide, SSE template, and school improvement guidelines, play a crucial role in the inspection process. These tools provide a structured and standardized approach for inspectors to assess and evaluate various aspects of school performance, including teaching quality, learning outcomes, and overall school effectiveness. By employing these instruments, inspectors are able to ensure consistency, fairness, and objectivity in their evaluations (Knowledge and Human Development Authority, 2014; Education Review Office, 2021b; Department of Education Inspectorate, 2022c,d). All school leaders in Dubai schools acknowledged the high quality of the inspection framework and related materials on the KHDA website, and they exhibited a good understanding of the standards and indicators. A principal spoke about his initial experience with the inspection framework, saying, ‘I found that the framework, introduced by Dubai and aligned with UK Ofsted, to be remarkable. It was a significant opportunity for growth and learning for me’ (DBSL2). Another principal explained ‘One of the benefits of the inspection process is that you have access to a framework that you can study, but it truly comes to life during an actual inspection. The framework provides you a theoretical understanding, but when you go through the inspection, you can make real-life connections with what you have learned. It makes the framework more meaningful and impactful’ (DBSL3).

In the case of Pakistan, school leaders occasionally voiced apprehensions about the lack of quality criteria. ‘They [supervision staff] do not have proper criteria to tell the schools what areas will be monitored, where schools are and what they should aim to achieve?’ (PKSL1) The only standards mentioned by the school leaders were the indicators used by the MEAs to collect data and the standardized classroom observation tool used by the AEOs in their clusters.

In Ireland, the inspectorate has recently introduced a revised framework of quality. When questioned regarding the effectiveness of the new document, the school principals referred to a discrepancy between the schools’ practice and the expectations set by the framework, especially since it was launched after the pandemic, a time when communication between schools and the inspectorate was limited or non-existent. The school leaders raised several concerns, as follows:

‘I think certainly it was a retrograde step to introduce a brand-new document that was just a revamp of an old document and is very externalized’ (IESL4).

‘To me many of them [indicators] sound like a lofty kind of success criteria’ (IESL3).

School leaders in New Zealand showed an interest in utilizing both the Framework of School Improvement and the framework of evaluation indicators jointly. As a school principal stated,

‘Both frameworks are incredibly helpful, especially when school leaders take time to read them, share the information with their teams, and think about how they can make a positive impact in the school. I believe that these documents are based on well-informed research’ (NZSL6).

All the evaluation partners consulted were highly optimistic about the tools that the ERO has developed to facilitate the self-evaluation process. One evaluation partner, for example commented that the Framework of School Improvement enables schools to self-evaluate their position on various aspects of the school and to set aspirational goals for improvement. Another tool, the Board Assurance Statement, was noted to assist ‘schools understand the legal obligations they have and must be completed by the School Board of Management’(NZEP3).

3.4. Theme 4: impact

School inspection is likely to have several impacts. It is expected to promote accountability and quality assurance, potentially driving school improvement through feedback and recommendations. It may also foster a culture of continuous self-evaluation and professional development among educators. Furthermore, school inspection is anticipated to enhance transparency and trust among stakeholders, facilitate the identification of best practices, and potentially contribute to raising educational standards and outcomes (Ehren et al., 2013; Hofer et al., 2020). Most of the school leaders, in Dubai and Pakistan, acknowledged that inspections have contributed toward improving some aspects of schooling. A school principal shared, ‘Our teacher and student attendance, overall cleanliness of the school, the physical environment of the school, and students’ learning [we have to show them our annual results] have improved because of MEAs and AEOs’ monthly visits. Without monitoring and supervision, I think we will become complacent’ (PKSL5).

A principal of a Dubai school appreciated school inspection for bringing a radical change in the teaching practices. ‘What I feel is that if we had no inspection, we would have been the old 17th century model of the blackboard and the chalk’ (DBSL5).

The overwhelming majority of school leaders in Dubai expressed positive sentiments regarding the influence of school inspection, particularly in relation to its efficacy in promoting the effective utilization of formative assessment, leveraging data to inform instructional practices, and incorporating technology in teaching and learning processes.

The Irish school leaders were skeptical of the impact of the school inspection.

An Irish deputy principal shared, ‘I am 34 years in the classroom, and I’ve only had two inspections in all those years of teaching. Of all the 1000s of classes I have taught, I’ve only had two people in my room’ (IESL3).

School leaders in New Zealand while appreciated the newly launched approach to school evaluation, they criticized the previous approach as inadequate for bringing about any improvement in teaching and learning especially with regard to serving the underserved and marginalized.

‘I really do not know if there has been [an impact] and I think that’s part of the problem with it. That’s why they are looking for change’ (NZSL2).

Another principal ironically commented that while the education review itself may not have had an impact, its report certainly did.

‘The education review officer visits schools to conduct review, which can result in a negative report and put the school on a one or two year review cycle. This can lead to students and parents leaving the school. However, some schools, like mine, have a longer four or five year review cycle, which has resulted in a waiting list of hundreds of students. This may impact the students who tend to migrate to other schools’ (NZSL4).

One principal, for example highlighted a significant observation and stated that the direct impact of the ERO feedback is limited due to the school leadership’s tendency to foster an attitude among their staff that can hinder the effective utilization of received feedback (NZSL3).

All representatives of the inspection agencies emphasized that they have been instrumental in improving the quality of education to some extent.

‘We started around with, let us say 30% of our schools were good and better. Now it’s like 70% of our schools are good and better. So definitely inspections have influenced the schools and influenced the improvement of schools. It might not be a direct improvement support, but inspection forces or pushes schools to improve’ (DBSI1).

‘The Irish inspectorate would always argue that inspection, by itself, can never guarantee that teaching and learning in schools is of a good quality – inspection is just one element of a complex eco-system that supports and encourages high quality provision’ (IESI1).

‘We have made a significant impact, but it is challenging to quantify as there are many factors that contribute to a school’s success, and we are only one part of it. After conducting one and two year reviews with schools that had problems, I can confidently say that 80–85% of the schools I worked with went on to become successful, as the issues were addressed. We served as a catalyst for change’ (NZEP5).

‘Our monitoring report is integrated with EMIS, an efficient system that is linked to the SIS [school information system]. If any serious issues arise, they are immediately brought to the attention of the District Education Authority and Administration, which has brought a lot of improvement in the teacher and student attendance and availability of essential facilities in schools’ (PKSI1).

The above is of great interest, in that without a significant impact, the entire expensive business would be a waste of resources. In general, the response was positive although in NZ it was felt that the new system would in time produce more of value than the previous one. Irish school leaders were a bit skeptical and so it seems that the Irish Inspectorate may perhaps have some more convincing to do.

4. Discussion and conclusion

Interestingly, school inspection is a reciprocal activity in which inspectors assess the quality of teaching and learning in schools while schools, in turn, continually evaluate the professional competence of the inspectors. Inspectors utilize quality criteria as the basis for evaluating schools, while schools maintain a stringent focus on inspectors’ code of conduct and professional standards. Any deviation from the prescribed professional trajectory is deemed unacceptable. Despite the professionally competitive environment, the experiences and perceptions of school inspection and evaluation among school leaders varied. While some expressed dissatisfaction with the inspectors and the process, others regarded it as a beneficial endeavor that instilled a sense of vigilance and attentiveness toward the quality standards and inspection criteria. The variability in school leaders’ perceptions of the inspection process and inspectors is highlighted by one school leader who observed ‘huge variations’ in the level of professionalism exhibited by inspectors (IESL3). Bitan et al. (2015) as a part of their study about the perceptions of school principals about school inspections quantified the qualitative responses of the school principals and found that 42% of the respondents had positive attitude toward school inspections, while 32% expressed negative attitudes (p. 430).

One of the common features of all these school evaluation regimes is the professional development of inspectors, monitoring and supervision staff, and evaluation partners. Regardless of their background, prior experience and qualifications, they receive training upon induction. These agencies invest heavily in building the capacity of their human resource to enable them to provide high-quality evaluation, analysis and advice. The inspectors and other personnel responsible for quality assurance mentioned two distinct types of professional development: induction training and ongoing continuous professional development. These two categories of training are also acknowledged by Baxter and Hult (2017), particularly emphasizing the significance of continuous professional development, which allows inspectors to learn and grow through practical experience, eventually progressing from a team inspector role to a lead inspector position. Therefore, notwithstanding their concerns and reservations, school leaders generally concurred that school inspectors and evaluators possess substantial training and expertise in their field. However, except for Pakistan, the two primary concerns expressed by school leaders regarding school inspectors or evaluation partners were their lack of experience in school management as principals, resulting in limited or no experience in running a school. Additionally, as they have not been in schools for years, their knowledge of current classroom practices and stakeholders’ expectations may be outdated. Both criticisms are valid and pose a challenge for these professionals, who are expected to guide school leaders toward improvement in teaching and learning and hold schools accountable for their actions (Penninckx et al., 2016).

Although school leaders had several concerns about the quality of inspectors, they were generally aware of the onsite inspection activities and agreed that inspectors usually follow their code of conduct. It can be said that the quality assurance agencies have been successful in communicating their processes and ensuring transparency in most cases. As stated by the ERO, ‘We designed our review process to be as open as possible. There should be no surprises’ (Education Review Office, 2021b). Especially in case of New Zealand, the BAS checklist results in ‘an increased awareness of laws and regulations at school level’ (Hult and Segerholm, 2017, p. 129).

School leaders in Dubai and Pakistan felt that the quality assurance systems have brought about some improvements in schools, while those in Ireland and New Zealand did not find them impactful. There is also a clear dichotomy between school leaders’ perceptions and inspectors’ claims of impact at least in these two countries. This attitude reflects a negative correlation between the duration of a quality assurance service and its perceived effectiveness. The longer the quality assurance service has been in place, the less effective it is perceived to be by those who receive it. The perception of decreasing effectiveness of a school inspectorate over time may be attributed to several factors. One possible reason is that as the inspectorate becomes more established, there may be a tendency for complacency or routine in the inspection process, leading to a reduced sense of novelty or impact. Additionally, stakeholders who have experienced the inspectorate for a longer duration might develop higher expectations or critical perspectives based on their accumulated experiences, which can contribute to perceiving the inspectorate as less effective. Moreover, there generally appears to be a negative correlation between the perception of school leaders and inspectors regarding the quality of inspection practices and their perception of the impact of inspection. In other words, the greater the difference between their perceptions, the smaller the perceived impact. Similarly, the school leaders’ perception of the quality of inspection and inspectors is positively correlated with their perception of the impact of school inspection on improving the school. When school leaders have a positive image of the quality of school inspection and the inspectors who conduct them, they are more likely to believe that school inspection has a positive impact on improving the school. Put simply, school leaders’ opinions about the quality of school inspection and inspectors are related to their opinions about the effectiveness of school inspection in bringing about positive changes. According to one of the principals in New Zealand, if a principal has a ‘mindset of resistance’ or views feedback as ‘criticism’, it is unlikely that school inspection will have a positive impact (NZSL4). On the other hand, when school leaders and teachers view inspection as a positive process that contributes to school improvement, the school is more likely to benefit from it (De Wolf and Janssens, 2007). In order for school inspection to be considered a beneficial element in school improvement, it is essential that the school leaders perceive it as a constructive and supportive activity.

By publishing a range of documents, guides, reports and explicit quality criteria outlined in extensive quality frameworks and making these resources accessible to the public via websites and other means, the school evaluation agencies assume that the school staff understand them well and work accordingly. Intended to promote transparency of school inspection practice, these resources, on the contrary, are perceived as the inspectorate’s documents at least in Ireland. Despite the involvement of experienced researchers in developing these frameworks and other inspection support materials and holding orientation and training sessions for the school leaders, the top-down nature of these frameworks cannot be reversed. To increase the acceptance of the quality criteria and other support materials, it is essential to involve a representative sample of school leaders and teachers in the development process, both through face-to-face interactions and by creating an online forum where they can review the documents and minimize the disconnect between theory and practice before sharing them with all schools. However, school leaders in Dubai displayed a remarkable familiarity with the quality criteria, demonstrating an in-depth knowledge and recall of the relevant standards.

Regarding Pakistan, it was observed that the school leaders and supervisory staff were primarily aware of only the indicators that were used by the MEAs to collect data. This limited awareness appears to have led to a significant overlap in their onsite monitoring and supervisory practices. For instance, one school leader expressed dissatisfaction with the frequent monitoring and supervisory visits, stating ‘Instead of spending so much on inspection and monitoring officials, the education department should prioritize investing in teachers’ professional development’ (PKSL7). However, the AEOs were found to be familiar with their classroom observation tool and its usage. Unfortunately, not a single interviewee referred to the Framework of Minimum Standards of Quality.

School leaders from all four jurisdictions knew little about the internal quality assurance mechanisms of their evaluation agencies. During interviews, only school leaders from Dubai referred to the quality assurance team, while a principal from Ireland mentioned the complaint process. There appears to be a wide communication gap between schools and the inspectorates regarding the measures that they take to improve the quality of their service and their inspection practice as a whole. To address the misconceptions that exist among school leaders about the inspection services, the inspectorates need to have frequent and open communication with schools and the stakeholders, both upstream and downstream, to ensure they are fully aware of the inspectors’ work and can appreciate it.

Despite various measures taken by inspectorates and the quality assurance agencies, there remains a disconnect between school inspectors’ professed quality and school leaders’ perceptions of their quality. As one of the school principals agreed that the best professional development that she ever received was when she took a sabbatical at the ERO for a few months, where she spent time with evaluation teams visiting schools ‘that was just completely eye opening.’ She found the review officers to be highly skilled at picking up, as they walked into the school, what the school was like. She suggested that ‘anyone going to be a principal should spend six months with the ERO and get a flavor of what’s going on around the place and see the good and the bad and the ugly at times’ (NZSL2). Another school leader from Ireland expressed concerns about the outdated knowledge of classroom practices held by inspectors and suggested that they should spend time working in schools to gain better understanding of recent challenges and demands in the system. We recommend that education systems establish a rotation program to allow school inspectors and leaders to switch role after a period of time. This would provide school leaders with a greater appreciation of the inspectors’ work and update inspectors on the day-to-day realities faced by school leaders. This would help reduce the trust deficit that was frequently observed during our conversations with school leaders.

School leaders expressed concerns about quality of inspectors, dissatisfaction with reporting and feedback process and at times, did not appreciate the documents related to school inspection. Despite variations and criticism, a common observation that emerged was that every school leader was familiar with the inspection procedures, indicating successful communication of quality assurance services limited though. However, it is essential for quality assurance services to ensure that school leaders have confidence in the proficiency of inspectors and are aware of the ongoing efforts undertaken by quality assurance services to recruit exceptionally skilled professionals who possess contemporary knowledge and extensive expertise in best practices. Moreover, it is imperative to establish improved avenues of communication to facilitate heightened awareness among school leaders regarding the efficacy of inspectors’ work and the comprehensive measures implemented by inspectorates to ensure the quality of their own practices. This initiative will foster enhanced trust between school leaders and inspectors, consequently amplifying the overall influence of school inspections.

In conclusion, inspectorates and other quality assurance agencies train their staff, develop supporting documents, and update their websites and practices to stay up to date with changing trends in the field. This is acknowledged by many respondents in this study. However, as Lindgren and Rönnberg (2017) argue, despite these efforts, school inspection systems often strike a balance between transparency and a level of ‘black-boxing’ to establish their credibility (p. 173). The present study also reveals a gap between the perceptions of school leaders and school inspectors, which may arise due to intentional or unintentional ‘black-boxing,’ and can only be rectified through open and frequent communication.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee (REC), Dublin City University, Dublin. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SG wrote the manuscript. GM reviewed and contributed to the manuscript revision. All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtoon Khawa & Balochistan.

2. ^Punjab: a. Chief Education Officer, District Education Officer, Deputy District Education Officer, Assistant Education officer. b. Policy Implementation and Monitoring Unit – Monitoring & Evaluation Assistants. Sindh: a. Director Education (schools), District Education Officer, Deputy District Education Officer, Sub-divisional Education officer & Taluka Education Officer. b. Directorate of Monitoring and Evaluation – Field Monitors. KPK: a. Director Education (schools), District Education Officer, Deputy District Education Officer, Deputy District Education Officer, Assistant Sub-Divisional Education Officer & Assistant District Education Officer. b. KP Education Monitoring Authority – Data Collection and Monitoring Assistant. Balochistan: a. Director Education (schools), District Education Officer & Assistant District Education Officer. b. Policy Planning and Implementation Unit – School Monitors.

3. ^The ERO has changed their evaluation approach instead of periodic and event-based evaluation, evaluation partners (formerly called reviewers) foster an ongoing relationship with schools assigned to them to support school self-evaluation and improvement. They work in a more collaborative way with schools to tailor approaches to school context and need (Goodrick, 2020).

4. ^Survey instruments with questions aligned to the Education Review Office (2016) to gather the perspectives of leaders, teachers, students and whānau.

5. ^Public Service Commission (PSC) is a government agency responsible for hiring and administering the provincial civil services and management services. Every province in Pakistan has a separate PSC.

6. ^Building availability, Building occupation, Classroom and room types, Teaching staff details, Non-teaching staff details, Enrollment-attendance gap, Administrative visits, Delivery of textbooks, Stipends, Basic facilities, Parent-teacher council funds.

7. ^A cluster of schools assigned to an AEO.

References

Altrichter, H. (2017). “The short flourishing of an inspection system” in School inspectors: Policy implementers, Policy Shapers in National Policy Contexts. ed. J. Baxter (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 207–230.

Altrichter, H., and Kemethofer, D. (2015). Does accountability pressure through school inspections promote school improvement? Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 26, 32–56. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2014.927369

Baxter, J. (2017). School inspectors: Policy implementers, policy shapers in national policy contexts. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Baxter, J., and Hult, A. (2017). “Different systems, different identities: the work of inspectors in Sweden and England” in School inspectors: Policy implementers, Policy Shapers in National Policy Contexts. ed. J. Baxter (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 45–69.

Behnke, K., and Steins, G. (2017). Principals’ reactions to feedback received by school inspection: a longitudinal study. J. Educ. Chang. 18, 77–106. doi: 10.1007/s10833-016-9275-7

Bitan, K., Haep, A., and Steins, G. (2015). School inspections still in dispute–an exploratory study of school principals’ perceptions of school inspections. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 18, 418–439. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2014.958199

Brown, M., McNamara, G., and O’Hara, J. (2016a). Quality and the rise of value-added in education: the case of Ireland. Policy Futures Educ. 14, 810–829. doi: 10.1177/1478210316656506

Brown, M., McNamara, G., O’Hara, J., and O’Brien, S. (2016b). Exploring the changing face of school inspections. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 16, 1–35. doi: 10.14689/ejer.2016.66.1