- 1Department of Special Education, Gongju National University of Education, Gongju, Republic of Korea

- 2Innovation Institute for Future Education, Kunsan National University, Gunsan, Republic of Korea

- 3Department of Education, Gongju National University of Education, Gongju, Republic of Korea

Introduction: This research aimed to study the achievement of teacher agency of Korean pre-service teachers through their experiences in an international teaching practicum (ITP). This study also diagnosed the domestic pre-orientation (DPO) program of G University to seek the possibilities of developing a TPACK strengthening program. The participants of this study were five female Korean pre-service teachers who were in the ITP from 2015-2016.

Methods: The data were collected in two different time slots: the teaching diaries and ITP reports from the Korean pre-service teachers, DPO teaching materials, and program instructor's field notes were collected in 2016, and then, the interview was conducted in 2018.

Results and discussion: To study their teacher agency achievement, the three chordal triads of agency, the iterational dimension, the practical-evaluative dimension, and the projective dimension, were spotlighted and used as the lens to analyze the data. In addition, the DPO program was analyzed based on the elements of TPACK competencies. The research shows that the ITP was a trigger experience for the Korean pre-service teachers in terms of the achievement of teacher agency. The participants could project their aspirations and then decide and execute what they had learned from the ITP in their actual Korean classrooms. Also, the need to reconstruct the DPO program to be able to assist the pre-service teachers' TPACK achievement has been raised.

1. Introduction

Since the first COVID-19 case was noted, various kinds of online platforms such as Metaverse, virtual reality, applications (Apps), and other online-based resources have expanded their boundaries in the education area significantly. As people had to keep their distance from each other, the untact education format has been facilitated in schools all over the world. In the meantime, almost every content offering in schools was connected with those systems. Due to COVID-19, the importance of internet- and digital technology-based learning has been strengthened. The need for digital technology has increased, and students in the contemporary world are deeply immersed in the various kinds of digital resources. Therefore, in terms of educating, training, and preparing pre-service teachers, among the varieties of “competencies,” the digital competencies (Instefjord and Munthe, 2017) have started to be considered one of the key competencies. Moreover, in teacher training schemes, the elaboration of not only content teaching but also internet- and digital-based teaching skills has been raised. With the flow of the contemporary world, e-learning also become one of the crucial parts of teaching and learning. The term e-learning “… is an umbrella term describing any type of learning that depends on or is enhanced by online communication using the latest information and communication technologies. The scope of such learning is very broad” (Nagy, 2005, p. 80). Self-directed learning and teaching require the agentive participation of learners and teachers.

In addition, COVID-19 opened the door to the phase of Industry 4.0, in which information and communication technology has more power in existing industries, including the education industry. As the World Economic Forum (04 April 2016) forecast, the global shift through rapid technology changes (Berkley, 2016; Buehler, 2016; Hallett, 2016), including a Metaverse area, a non-fungible token, and “School in the Cloud” (untact classroom). At this point, teacher agency faces 2-fold issues related to “technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)”: (1) how to accept and utilize the rapid technology into “pedagogical content knowledge (PCK)” and (2) how to guide and educate the young generation, including elementary students, to self-protect themselves when selecting and engaging in virtual realities such as various Metaverse programs and one-person broadcast stations.

To train pre-service teachers, in many countries, various forms of teaching practica have been conducted as an essential part of teacher training schemes. As it is the chance to grasp the sense of “the actuality of the context” of schools, classrooms, students, etc. (Kim et al., 2020, 2021), “teaching practica” has been considered an important stage to support pre-service teachers' competency strengthening. In practice, pre-service teachers were learning and developing through teaching (Farrell, 2016). In the teaching practicum program, local schools and the pre-service teachers' universities were critical units of a functional organism as the union of the communities of practices (COP) (Wenger, 1998). Through participation in teaching practica, pre-service teachers could develop their skills. To them, it was a chance to … “developing their discourse skills, their teaching skills, and their overall professional knowledge” (Farrell, 2016, p. 39, his italics). In the context of a given educational policy, teachers are responding and reacting actively while also making “sense of externally initiated policy.” In the procedure, multifarious factors were affecting the procedure (Priestley et al., 2012, p. 198).

The effects of ITP in terms of the participants' multicultural competencies have been explored, and currently, it is time to explore the possibility of reconstructing the ITP program as a site to strengthen pre-service teachers' digital competence. This also will influence the pre-service teachers' teacher agency by assisting them to achieve an understanding of digital utilizing skills as well as an understanding of other kinds of knowledge such as technology (T), pedagogy (P), and content knowledge (CK) and the convergence forms of teaching in education. To explore this, in this study, agency and TPACK will be used as lenses to analyze the data from the pre-service teachers.

The purpose of this research was to study the effects of an international teaching practicum (ITP) in terms of creating space for the achievement of teacher agency and TPACK competence. This study also attempts to seek a way to develop the ITP program in this study to strengthen the TPACK competence of pre-service teachers. The research questions of this study are as follows:

(1) Has the international teaching practicum experience brought any changes in pre-service teachers' personalities, such as attitude, ways of thinking, perceptions of the classroom, teaching, and self?

(2) In which ways was the Korean teachers' teacher agency achieved?

(3) Which components of TPACK have been found in the DPO, and what should be complemented to construct the entire ITP to strengthen TPACK?

2. Literature review

2.1. Multicultural competencies

Multicultural competencies consisted of three factors: multicultural knowledge, multicultural attitude, and multicultural skill (Wilson, 1993; Willard-Holt, 2001; Kim et al., 2019, 2021, 2022). First, multicultural knowledge is knowing about multiculturalism. It has four subfactors: multicultural society knowledge, multicultural student knowledge, multicultural education knowledge, and multicultural education effect knowledge. Second, the multicultural attitude is about the person's reaction toward multiculturalism. It has two sub-factors: multicultural society attitude and multicultural education attitude. Finally, multicultural education skill is something that can be achieved via participation in the context, which would be the background of the teachers' teaching activity in a multicultural classroom. It has two sub-factors: multicultural education environment skill and multicultural education method skill (Park and Kim, 2015). ITP was the place where the pre-service teachers have been strengthening various competencies related to teaching through actual exposure to the site. Also, the effects of an ITP also have been reported in many research studies, and in particular, the participants' multicultural competence development was reported (Wilson, 1993; Willard-Holt, 2001; Tang and Choi, 2004; Stachowski and Sparks, 2007; Walters et al., 2009; Barton et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2019, 2021, 2022; Jin et al., 2020).

Aligning with the importance of e-learning and technology-based teaching, the importance of student agency and teacher agency has been spotlighted by OECD learning compass 2030 (OECD, 2015; Hughson and Wood, 2020). In recent several years, while teaching practicum, ITP, and other kinds of programs have been conducted by using technologies, the importance of technology-related knowledge and skills of teachers, in other words, digital competence, has been spotlighted. Moreover, the emphasis on the importance of the way of applying tools to their classroom “in meaningful ways” (Doering et al., 2014, p. 235) is important rather than simply following the trend of teaching, that is, not only the knowledge of technology but also the competence to facilitate the tool to be useful in the classroom is important in terms of discussing the competencies of teachers.

2.2. Agency and teacher agency

In much of the research, teachers have been considered agentive beings for change and they also have been considered as curriculum developers (Priestley et al., 2015). The policy has been articulated rather prescriptively and suggests what teachers should do; however, teachers could not avoid being descriptive in terms of implementing what the policy says in their classrooms (Biesta et al., 2015). The classroom is the place where the policy is being implemented, and the teachers are the agent of its implementation, so teachers are also called policymakers. While teachers are very focused on their practice, the policy is rather “ignoring or subverting the cultural and structural conditions” (Priestley et al., 2015) of the practice. Therefore, it often destroys the balance of policy and practice and rather frequently creates tension and conflict. The experience of the individual in each context and time could vary as positive, neutral, or negative, but still, people are learning through the experience. It, indeed, influences an individual's achievement of the agency. Emirbayer and Mische (1998, p. 970) defined the agency as

…(t)he temporally constructed engagement by actors of different structural environments—the temporal-relational contexts of action—which, through the interplay of habit, imagination, and judgement, both reproduces and transforms those structures in interactive response to the problems posed by changing historical situations.

Biesta and Tedder (2006) defined agency as “not something that people can have; it is something that people do or, more precisely, something they achieve” (cited in Priestley et al., 2015, p. 3, their italics). “Agency…(ellipsis)… is both temporal and relational” (Priestley et al., 2015, p. 3), so it is about the relationship in the given time and the space. This recalls Weedon's perspective on the subject. To them, the individual was “diverse, contradictory, dynamic, and changing over historical time and social space” (Weedon, 1987, 1997 cited in Norton and Toohey, 2011, p. 417). This perception aligns with the agency's understanding of time and space.

Emirbayer and Mische conceptualized agency as the “chordal triad” (1998, p. 970). Based on the study by Emirbayer and Mische (1998), and by adding up the conceptualization of agency with the value of ecology, Priestley et al. (2015) have reframed a diagram of “the key dimensions of the teacher agency model” (Priestley et al., 2015, p. 30). The model consisted of three dimensions: iterational dimension (past), practical-evaluative dimension (present), and projective dimension (future). The iterational dimension is about one teacher's personal history as a human being and professional history as a teacher. Life histories and professional histories, including “personal capacity (skill and knowledge), beliefs (professional and personal), and values” (Priestley et al., 2015, p. 31), are related to the iterational dimension of teacher agency. The practical-evaluative dimension is about everyday life, and it contains three sub-aspects: cultural aspects, structural aspects, and material aspects. Cultural aspects are revealed through the teacher's verbal and non-verbal ways of expression. These include ways of thinking, speaking, and values (Priestley et al., 2015). Structural aspects are about relationships, roles, power, etc., and it is “concerning the ways in which people are positioned relative to each other” (Priestley et al., 2015, p. 86). Material aspects concern the materials and physical environment of the “day-to-day working environment” (Priestley et al., 2015, p. 33). The projective dimension is about the teacher's aspiration for the future. This dimension considers the temporality of the individual's interaction with the given situation and also a series of outcomes of individuals' interaction with the context in a timescale, from short term to long term (Biesta and Tedder, 2006).

According to Emirbayer and Mische, the practical-evaluative dimension contains five sub-procedures of “Problematization,” “Characterization,” “Deliberation,” “Decision,” and “Execution” (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998, p. 998–999, their italics). Problematization is the starting point of exploring the practical-evaluative dimension of the agency. People recognize the problem and then characterize the problem based on their previous experience and achieve knowledge. “Plausible choices must be weighted in the light of practical perceptions and understandings against the backdrop of broader fields of possibilities and aspirations (here the element of projectivity enters into processes of practical evaluation)” (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998, p. 998). Furthermore, decision refers the moment the individual reaches the moment of choice. After that, the stage of execution by “act rightly and effectively within particular concrete life circumstance” (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998, p. 999) is being followed.

In this study, these procedures have been understood as not only belonging to the practical-evaluative dimension of teacher agency. Rather than that, we have understood the procedure as underlying the full extent of the individual's experience. The three dimensions of teacher agency are revealed and intertwined. Moreover, the teacher agency is achieved “by the individual-in-transition” (Biesta and Tedder, 2006, p. 20). Teachers' perceptions, beliefs, and aspirations are all intertwined.

Teachers' perceptions of and orientations to the knowledge they are presented with may be shaped by belief systems beyond the immediate influence of teacher education (Nespor, 1987, p. 326 cited in Priestley et al., 2015, p. 37).

To sum up, the agency is “… an emergent phenomenon, dependent on the interplay of both the individual (capacity–skills, knowledge, beliefs, etc.) and conditions (cultural, structural, and material resources and constraints)” (Priestley et al., 2015, p. 136), and teacher agency focuses on teachers in their teaching context. In terms of the capacity and conditions of a competitive teacher agency, the agency would attempt to extend its pre-service teachers' attitudes, ways of thinking, and perceptions of the classroom, teaching, and self in order for them to be active policymakers in their classroom and school.

2.3. Technological pedagogical content knowledge

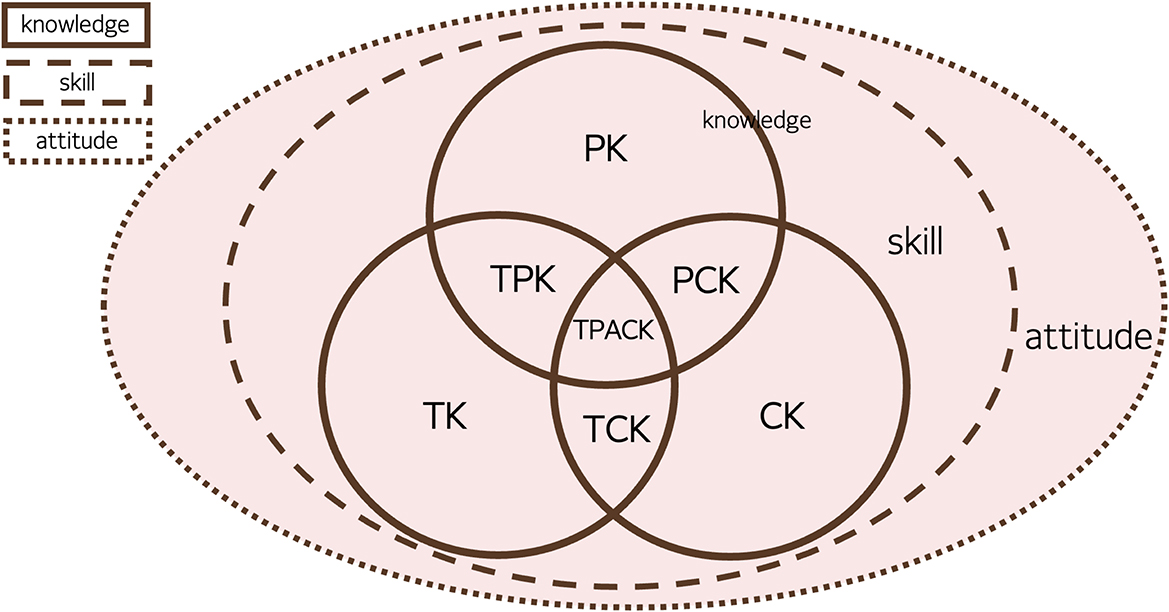

TPACK shows the relationships between various basic components of knowledge (Mishra and Koehler, 2006; Koehler and Mishra, 2008 cited in Schmidt et al., 2009). The role of TPACK in the contemporary world is more important than ever (Cann, 2017; Fries, 2017; Kim, 2018). Rapid technology change, which is directly related to the young generation's jobs in the 4th industrial revolution, is currently creating and forecasting new jobs every day. TPACK is an acronym for “technology, pedagogy, and content knowledge” (Thompson and Mishra, 2007; Niess, 2008b, cited in Niess, 2011, p. 301). The TPACK framework has been revised by Koehler and Mishra (2008) as “content knowledge (C), pedagogical knowledge (P), technological knowledge (T), and the overlaps of these distinct knowledge bases as pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK), technological content knowledge (TCK), and technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)” (Niess, 2011, p. 301). In the past, this term was rather spotlighted in the areas such as science, mathematics, and technology (Niess et al., 2009), but currently, it is expanding its area into the humanities and social sciences.

Content knowledge (CK) refers to knowledge in relation to a certain subject itself. It can be subjects such as mathematics, English language, and science (Kim, 2017). Pedagogical knowledge (PK) refers to the knowledge about the process and way of teaching and learning. It contains activities such as learning activity management, evaluation, and teaching plan design (Kim, 2017). Pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), the concept suggested by Shulman (1986, cited in Kim, 2017), means pedagogical knowledge suitable/affordable/applicable for the teaching of certain content. This knowledge contains a “situational-contextual” feature as the applicable pedagogical knowledge could be varied according to a certain area of given content (Kim, 2017). Technological knowledge (TK) is the knowledge related to technologies that the teacher can use. This comprises the internet, digital videos, and interactive software. Social network services (SNS) such as Facebook and personal blogs also belong to this knowledge area (Kim, 2017). Technological content knowledge (TCK) is, regardless of the teaching behavior, concerned about the knowledge that specific content can be created, studied, and represented using technology (Kim, 2017). Technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK) is the knowledge facilitating teaching-learning strategies of teachers, regardless of specific content areas. This is related to the use of various technologies such as ICT usage in terms of a tool for cooperation (Kim, 2017). Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) means the knowledge required for teachers to possess in terms of the integration of technology into teaching activities in the area of subject content (Kim, 2017). The detailed elements of each area of TPACK are shown in the Appendix of this study. The researchers of this study consider TPACK as one of the competencies that not only pre-service teachers but also in-service teachers need to achieve. Our understanding of the TPACK framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. TPACK framework as a competence [figure developed based on the graphic from TPACK homepage (2012), http://tpack.org/. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, © 2012 by tpack.org].

TPACK provides a beneficial framework for the integration of teachers' application of technology with their teaching performance in their classrooms (Kim, 2017). Teachers act based on the cooperative framework of three elements: CK, PK, and TK (Kim, 2017). According to Niess et al. (2009, p. 10), teachers undergo the “Recognizing,” “Accepting,” “Adopting,” “Exploring,” and “Advancing” paths. Teachers initially recognize the need for applying digital technology in their classrooms. Then, they decide and move on to seek the appropriate tool to be implemented. After the teachers accept what they will be using in their classroom, they also require some time to be familiar with the tool themselves. Therefore, the use of the tool in the classroom will be rather limited at the beginning. Then, there will be an exploring period. Sooner or later, as the teacher is incorporating the tool more professionally, the skill of utilizing the tool of the teacher will be advanced (Niess et al., 2009). “Being able to integrate and use technology for educational purposes involves having a set of generic skills suitable for all situations, both personal and professional, as well as specific teaching-professional skills” (Instefjord and Munthe, 2017, p. 37).

3. Research methodology

3.1. G University's ITP program [domestic pre-orientation (DPO) and on-site teaching practicum (OTP)]

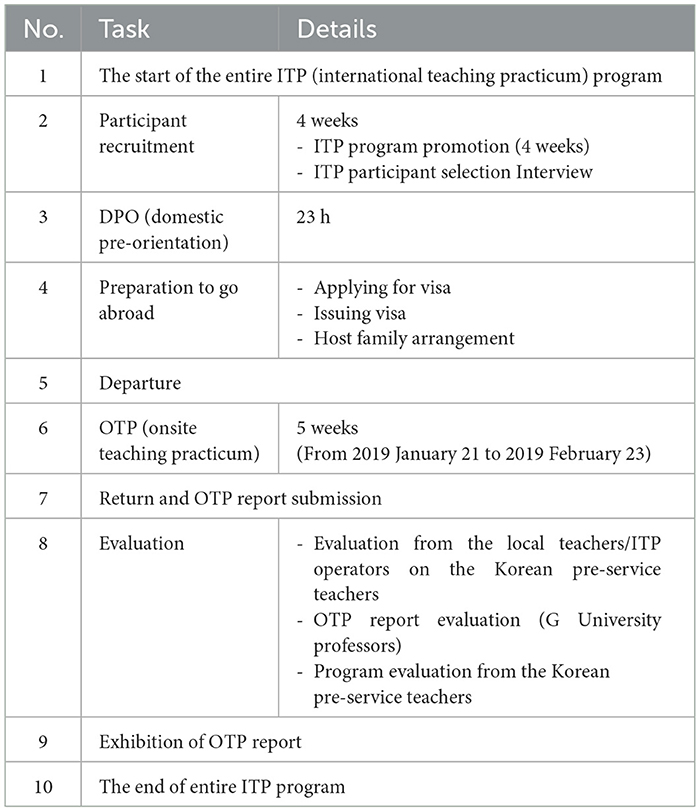

G University is located in the middle part of South Korea. They hold memorandum of understanding (MOU) with several universities abroad and send out their students every year for ITP. The ITP program of G University consists of 10 stages, as shown below (see Table 1).

At stage 1, the ITP program itself is reprogrammed. At the same time, it is the official start of the program. At stage 2, participant recruitment is conducted, and it takes for 4 weeks. At stage 3, domestic pre-orientation (DPO) is being conducted. At this stage, Korean pre-service teachers are trained at G University through various courses. There are various modules such as multicultural aspects, multilingual aspects, English conversation, children's development, and behavior management. Korean pre-service teachers also have a chance to explore the country and the school where they will be allocated soon. At stage 4, students and school prepare for the actual departure, and then at stage 5, they depart for the country where they are allocated. Stage 6 is the actual exposure time of 5 weeks abroad (OTP). At stage 7, they return to South Korea and submit an ITP report. Then, the evaluation procedure (stage 8) and ITP exhibition (stage 9) are followed up. After that, the ITP program officially ends (stage 10) (Kim and Yun, 2019; Kim et al., 2022). Among the 10 stages of the entire ITP, the third stage (DPO) and the sixth stage (OTP) could be counted as the main stages of the ITP program.

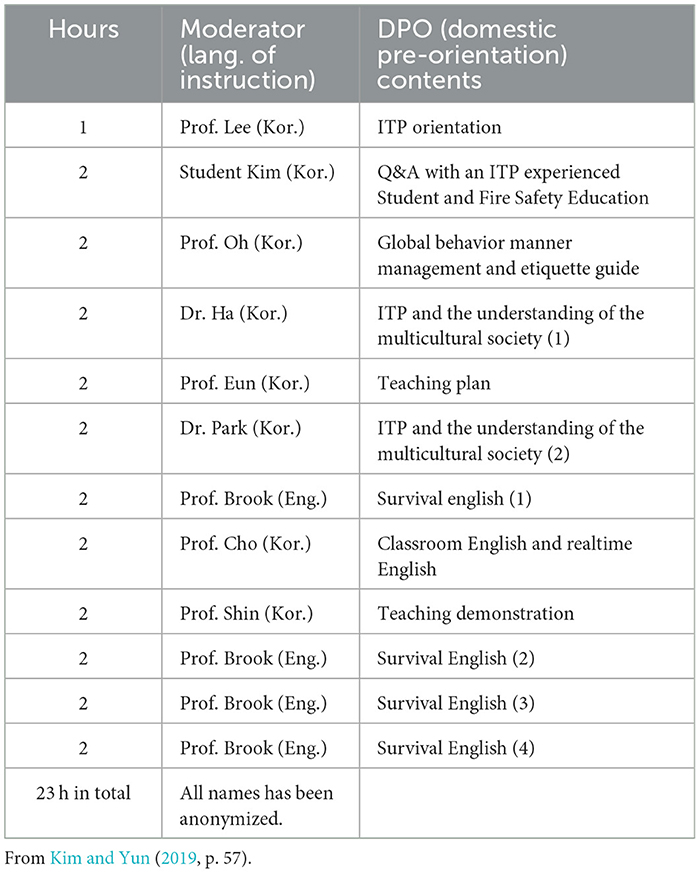

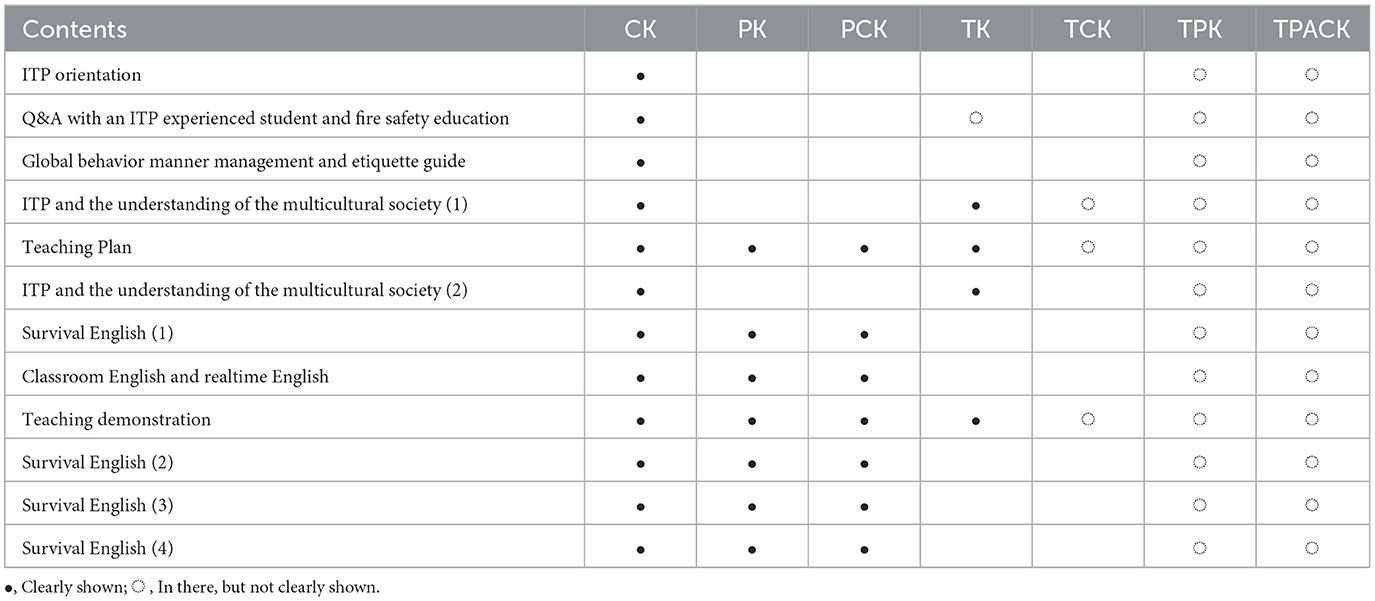

The domestic pre-orientation (DPO) consists of 23 h of lectures. The detail of the program is shown in Table 2.

As shown above, the program contains the “actual survival skills” that might be needed for Korean pre-service teachers who will be positioned in a linguistically and culturally different atmosphere. The content “ITP and the understanding of the multicultural society” (1) and (2) were conducted to strengthen the pre-service teachers' multicultural and multilingual perception. Also, there was a session to listen to stories from the previous ITP participants, including Q&A.

3.2. Research participants & data collection

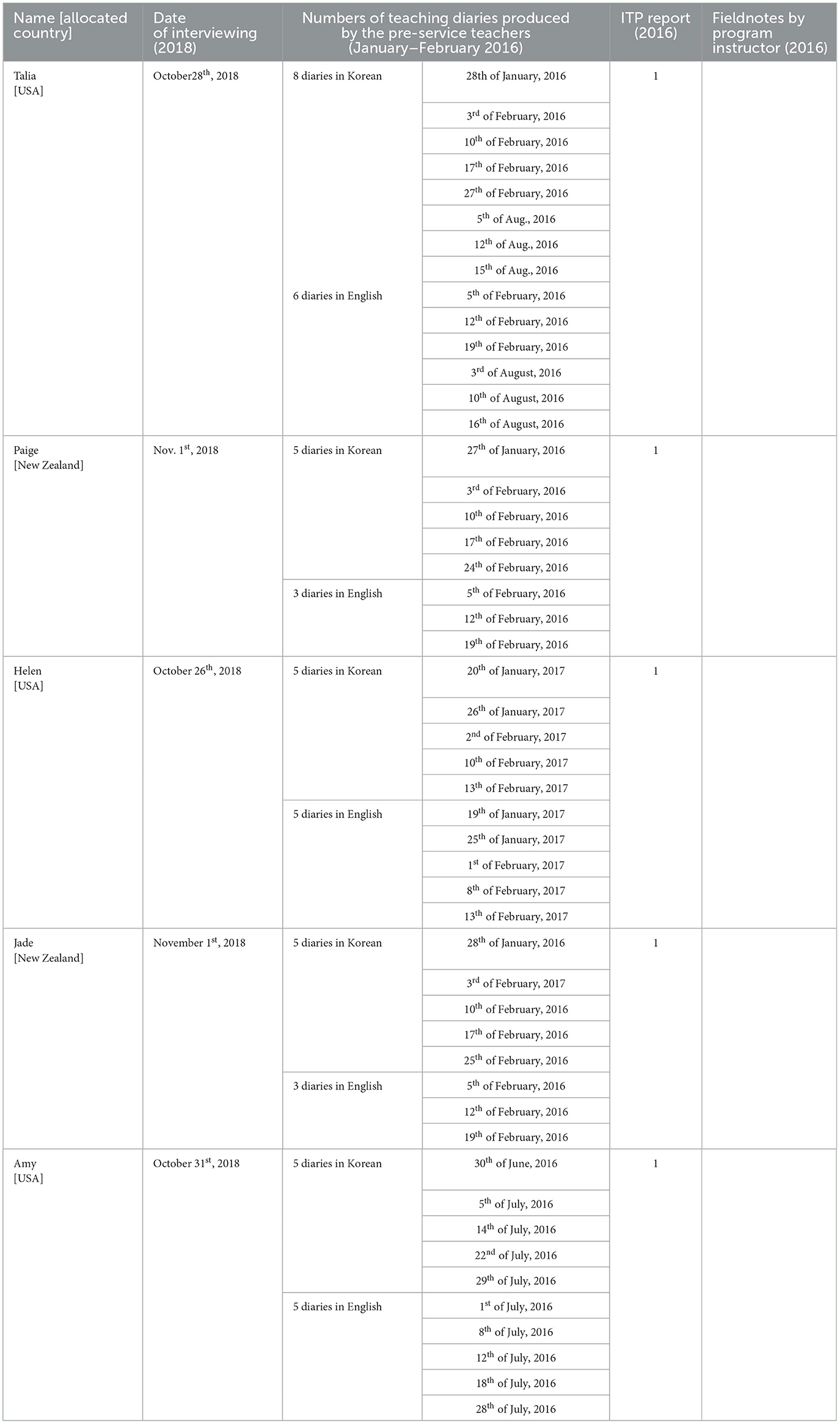

The participants of this study were five Korean pre-service teachers who were in the 2015–2016 ITP program run by G University, and they were all female teachers. The countries where the pre-service teachers were allocated varied. Some were in the United States of America (Taila, Helen, and Amy), and some were in New Zealand (Paige and Jade). All the participants” name has been anonymized. The details of the participants and data collection procedure are shown in Table 3.

The schools where the pre-service teachers were allocated held MOU with G University. In the case of Amy and Helen and Paige and Jade, the interview was conducted as group interviews. Grouping was decided based on the region where the pre-service teachers were allocated for the 2015–2016 ITP participation. In the case of Talia, her allocated region was different from the other pre-service teachers. Therefore, she was in the solo face-to-face interview. For this study, pre-service teachers' bilingually written teaching diaries and ITP reports were collected. Teaching materials used in DPO were also collected. Another set of data from the participants was the ITP report that each participant had to produce and submit to their university. There were also field notes written by the program instructor. Through the field notes from the program instructor, researchers could understand the ITP scene well.

The data were collected in several different time spots. In 2016, the teaching materials used in the DPO and pre-service teachers' teaching journals were collected. In addition to this, the pre-service teachers' teaching diaries were collected while they were in their on-site teaching practicum, and ITP reports were collected right after their completion of the ITP program in 2016. Alongside these data, a field note from the program instructor was collected in the same year. In 2017, the participants were in their preparation for a national examination to be teachers, and no data were collected at that time. Then in 2018, face-to-face group interviews were conducted, and at that moment, the research participants were in-service teachers in Korean schools. All of the data sets were triangulated, and the three were complementing each other (Denzin, 1978).

3.3. Data analysis

The research design and the data analysis procedure are shown in Table 4.

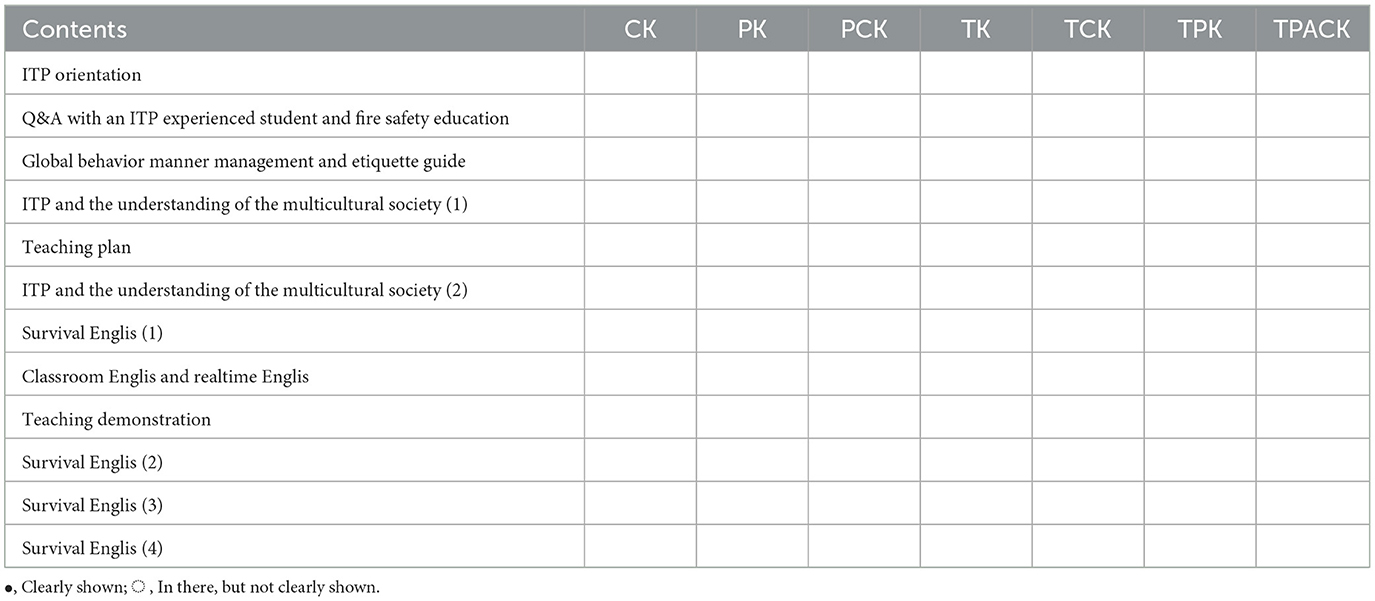

All the interview was voice-recorded at the scene and then transcribed accordingly. The data analysis was based on the in-depth interview, the transcriptions of the conversation, and journals from the research participants. These complemented each other and contained the authenticity of each participant's experience and voice. In addition to this, the 2 years of gap in this study's research design allowed both participants and the researchers to be able to take a close look at the data from a more objective point of view. As agency is defined as “not something that people can have; it is something that people do or, more precisely, something they achieve (Biesta and Tedder, 2006),” newcomer teachers take time (at least 2 years) to do and achieve their own multicultural competencies, technology (T), pedagogy (P), and content knowledge (CK) and the convergence forms of teaching in their real classroom. Moreover, through the 2 years of gap, the participants' status was changing. In 2016, they were pre-service teachers, and in 2018, they were in-service teachers. The interview in 2018 was the chance to diagnose their present and past. Their words in 2018 were compared with other data sets they offered to us in 2016, and the interview itself was a chance to remind themselves of their ITP experience retrospectively. The positionality change from pre-service teachers to in-service teachers allowed them to apply a lens of in-service teacher perspective on their own pre-service teacher life 2 years ago. The data themselves, therefore, hold reliability and validity. The teaching journals and the interview transcriptions of the pre-service teachers were coded four times and thematically analyzed using NVivo 12. The researchers followed the thematic analysis phase that Braun and Clarke suggested: (1) “Familiarizing yourself with the data” (Braun and Clarke, 2012, p. 60), (2) “Generating initial codes” (Braun and Clarke, 2012, p. 61), (3) “Searching for themes” (Braun and Clarke, 2012, p. 63), (4) “Reviewing potential themes” (Braun and Clarke, 2012, p. 65), and (5) “Defining and naming themes” (Braun and Clarke, 2012, p. 66). The researchers discussed the raised themes several times and then some vignettes that represent the pre-service teachers' teacher agency enactment through participation in the G University's ITP program were selected. To shed light on “teacher agency” and TPACK competencies in teacher education, for the analysis of the coded and selected vignettes, researchers read their stories several times carefully. Furthermore, researchers examined the DPO teaching materials in relation to the TPACK elements. The frame for the examination is shown in Table 5.

As shown in the table above, the teaching materials used in each content of DPO were compared with the characteristics of CK, PK, PCK, TK, TCK, TPK, and TPACK. To do so, a tool Schmidt et al. (2009) developed was first analyzed and then developed to be suitable for this study (see Appendix). When the characteristics of each element were clearly shown, researchers marked “•’, and when it seemed like it certainly exists, but not appeared clearly, researchers marked “ .” After the three researchers of this study diagnosed the DPO teaching materials' connection with the CK, PK, PCK, TK, TCK, TPK, and TPACK, the researchers discussed them all together, and then, the final decision was made. The three researchers had several discussions to identify the themes and categories arising from the data. They discussed until they reach an agreement point.

.” After the three researchers of this study diagnosed the DPO teaching materials' connection with the CK, PK, PCK, TK, TCK, TPK, and TPACK, the researchers discussed them all together, and then, the final decision was made. The three researchers had several discussions to identify the themes and categories arising from the data. They discussed until they reach an agreement point.

Through the whole procedure of data collection and analysis, not only the triangulation of the data but also the researchers' point of view was achieved. In particular, for the data triangulation, data sets collected in two different time slots were re-analyzed and interpreted by a compare and contrast procedure of the past and the present. Also, researchers applied the TPACK framework as one of the analytical lenses, and it strengthened the validity of the research methods, results, and data interpretation.

4. Research results

Through field experience, the Korean pre-service teachers achieved teacher agency. The pre-service teachers achieved broader insights about “diversity,” “being perfect,” and “teacher agency.” These themes appeared in their interview transcripts.

4.1. Achieving broader insights about “diversity”

Through the homestay experience, Talia was able to grasp the meaning of the term “diversity.” She said that this opportunity led her to recognize the importance of variety/diversity.

Talia:…(ellipsis)… Well, the house I home stayed was a very unusual one.

Interviewer: Yes.

Talia: I was not the only homestay student… There were a lot of homestay people in the house.

Interviewer: Yes.

Talia: …(ellipsis)… I had my homestay Mama, Papa, and there was a daughter of them. The daughter was staying with her partner in the house. Then I was there, and there was a Japanese student, and Vietnam student. …(ellipsis)… I think the homestay was the opportunity that I could think carefully about the variety! I think the realization of the importance of diversity is very important, and I still consider it a very crucial thing to teachers as I am working now as a teacher in this elementary school. Because there are a variety of students in this classroom… Personally, if there's no bad intension on certain behaviors of a student, as a teacher, I think I should accept it and understand it. I've been able to think about it because of the culture shock (laughs) that I experienced at homestay (laugh). It's an opportunity to think outside of what I normally thought it would be?

Interviewer: Ah~

Talia: Yes, I had that experience, and it was a great experience and a fresh shock to me.

(Talia, 28. October 2018, Interview)

In the homestay where Talia was staying, various nationalities, genders, and relationships existed. It was a “cultural shock” to her, but at the same time, she shifted the meaning of what she experienced. She was showing acceptance toward the differences she encountered and then reconstructing the meaning of the variety. By doing so, Talia's knowledge of cultural differences was shifting from “something surprisingly different and new from her previous classrooms” to “something expecting that she would have in her future classroom.” Through this experience, Talia could contemplate different ways of treating students in her future classroom. Here, the ITP experience was a “gateway experience” linking the pre-service teachers to their future role as classroom teachers. This finding is consistent with Yun (2016) study on young novice teachers in Korean elementary schools. As they were in a totally new context, they were fully immersed in a practice where the difference was pervasive. In her study, the participants showed their acceptance of those differences and the varieties they were facing in the practice. This acceptance was then linked to their achievement of insights regarding teaching in a multilingual and multicultural context.

Paige's story shows another form of diversity. In her OTP, Paige had an opportunity to participate in a meeting for a child with special needs. This was a gateway experience in which she could learn how teachers in the school reacted toward the diversity of students with physical or mental impairment.

There was a meeting about a child with special needs in our class….(ellipsis)… it has been an occasion to sincerely reflect on myself, seeing those who were seeking appropriate approach for children with special needs from an “educational” point of view. To be honest, I have been living in the same classroom as a special child, but I have somewhat considered him as being on an isolated island in the classroom….(ellipsis)…There was also the question of allocation of the student as it seemed much better for him to allocate him in a classroom for special needs. …(ellipsis)… To me, it was a grateful moment to completely change my mind about special education. Right after the meeting was over, I could begin to treat the child as same as any other child in the classroom and could start to recognize him as a classmate of mine, truly.

(Paige. 17. February2016, Teaching Diary)

She described the meeting that was conducted during the lunch period. There were eight people present: the vice-principle, the homeroom teacher, the child's mother, two special education teachers and two facilitators of curriculum design, and Paige herself. While Paige was sitting in the meeting, she recalled her previous mindset and self-portrait as a teacher who considered children with special needs as a group separate from the rest of the class. However, through observing the meeting, her perception regarding differences among people in a community of practice was expanded, allowing her to understand and accept students in diversity as they are, not as different. Being an agentive teacher is possible through achieving the knowledge that could enhance the agency of the teacher. To Paige, the layer of the experience becomes the knowledge, and it becomes the agentive knowledge.

4.2. Achieving broader insights about “being perfect”

In their stories, Helen and Jade described their personalities as “perfectionist.” Helen's story shows her expectation to be perfect in her English language use.

There has been fear that we must be perfect in our study… (ellipsis)… but even in Korea, foreigners are not asked to be perfect when they speak. … (ellipsis)… in a way, as you said before, we are asked to be perfect, so that makes us nervous, (I could achieve insights to understand myself) and think like, “What if a person isn't perfect (in performing one's job)?” and “Well, I can simply ask somebody (about it in order to obtain an answer).”

(Helen. 26. October 2018, Interview)

Helen believed that to be successful in Korea, she had to be perfect. Therefore, the value of achieving perfection in English use seemed to be settled as an important part of her personality. However, in the ITP experience, she struggled with English, and this led her to be flexible in her understanding of the term “linguistic capacity.” While the English language was her particular area of difficulty, her ITP experience facilitated the wider expansion of her understanding of the concept of “being perfect” in using a foreign language, i.e., she became much more relaxed toward this and was able to accept linguistic diversity and variety. This acceptance brought about personality change as her concept of perfection was broadened.

“Being perfect” was a huge part of Jade's personality. For example, she could not bear to make even small mistakes in her PowerPoint presentations (PPTs). However, after participating in the ITP, she became less determinative in her teaching. Her perfectionist personality had prevented her from believing herself to be “perfect” in everything and then led her to be inflexible in the selection of themes and textbook content that she presented to students in the classroom.

I am a bit of… perfectionist. So I have a tendency that I have to finish everything perfectly, and if I miss a thing, I normally feel nervous. However, well at least about the textbook… I don't know if it's because I've been there, but I have been able to consider the progress of my class… the progress of the next class is not the thing that I need to consider. Also, if there's something that seems not meaningful in children's learning, now I can skip that part. This influenced me rather hugely as now I can decide the part to opt out boldly… Because if I hadn't been there, I would've thought that I need to cover all the single pages of the textbook. However, I've been able to know that I can lead the children to learn even though I do not follow every content (of the textbook). I also have found that the textbook is not the answer, and this changed my personality a little bit. …(ellipsis)… I am really fastidious. (for example) if there's a small change in a PPT file, (laughter) I have to (inaudible), but nowadays I feel like… well… I don't need to do so. …(ellipsis)… since I've been there, I've learned a lot about things… that I need to put the burden down and confront things, I cannot be enough and it doesn't matter, well it might not seem good to others if I maintain (my original personality) …

(Jade. 01. Nov. 2018, Interview)

As a result of the ITP experience, Jade became more flexible. This change was reflected in her own classroom, where she was able to be selective when working with textbooks and to use or skip chapters according to what she considered most suitable for the students.

… So, I am trying to do a lot of events and activities by using real-life materials, not only textbooks. Now I can say that what I have seen and learned in the ITP is that even apart from the textbook, children can learn how to read and write enough. For example, now I can decide on chapters to skip and then bring the students to the library to find books that related to the achievement criteria of the chapter of the skipped textbook. …

(Jade. 01. Nov. 2018, Interview)

In 2018, Jade was an in-service teacher who created a new culture in her classroom. This was part of the new wave of change in her Korean school, and it was an import of new culture into her Korean school. She achieved insights to mingle with different cultures for the better.

4.3. Achieving broader insights about “student agency”

At the OTP scene, the local teachers were teaching their students by allowing them to actually see, feel, and touch. It was a very impressive way of teaching, and to Amy, it looked very effective.

In the United States……at the last school… they were giving students safety guidance… for it, they took the students with them, they took them to the cafeteria, then taught about the safety guidance in there by let them think about what kinds of accidents may happen in there…. (Inaudible)… I thought that teaching students by let them actually see and experience things is really effective.

(Amy. 31. October 2018, Interview)

This recalls one participant of Yun (2016) study who was a bit surprised by the Korean school system as Korean students tend not to be allowed to use scissors by themselves due to the “safety” reason, whereas using scissors by themselves was common to students in American primary schools. In American schools, safety guidance was given. Then, the students could join in the activity as active individuals.

5. Discussion

This section presents discussions in response to the research questions for this study as follows: (1) Has the international teaching practicum experience brought any changes in pre-service teachers' personalities, such as attitude, ways of thinking, perceptions of the classroom, teaching, and self? (2) In which ways was the Korean teachers' teacher agency achieved? and (3) Which components of TPACK have been found in the DPO, and what should be complemented to construct the entire ITP to strengthen TPACK?

5.1. Korean pre-service teachers' personality change and teacher agency achievement

The Korean pre-service teachers' narratives revealed the process of their personality change and teacher agency achievement. The pre-service teachers' experience in the OTP scene was about experiencing diversity and learning to be flexible. These became their identities in practice (Lave, 1992).

First, especially in Talia's case, the context shaped the Korean pre-service teachers' positioning among others, and the context influenced their teacher agency achievement. Based on their previous experience in Korean schools, the participants possessed a certain form of cultural competence. Concerning cultural competencies, Emirbayer and Mische (1998) noted that “Bourdieu's notion of habitus proves highly useful in showing how different formative experiences, such as those influenced by gender, race, ethnicity, or class backgrounds, deeply shape the web of cognitive, affective, and bodily schemas through which actors come to know how to act in particular social worlds” (p. 981). The homestay experience allowed Talia to recognize the importance of diversity by having the chance to think carefully about variety. She could apply her previous experience at the OTP homestay where she was surrounded by differences similar to those in her current classroom to project a classroom where diversity is pervasive. The “culturally-located, location-specific knowledge, such as indigenous knowledge or sensory knowledge needed to thrive or survive in particular places, is seen as not valuable for students to acquire” (Ivinson, 2019 cited in Hughson and Wood, 2020, p. 13). The context created location-specific knowledge and then influenced the Korean pre-service teachers' positioning in the practice. This affected the expansion of their identity not only as teachers but also as agentive individuals.

Second, through the interaction in the OTP context, the Korean pre-service teachers could recognize and problematize the Korean educational atmosphere, which was not inclusive compared with the American local schools. What Paige saw at her OTP school was the harmony of the vice-principal, homeroom teacher, mother of the child, two special education teachers, two curriculum design facilitators, and Paige herself. The local school was accepting and creating “the space as a whole,” where the members worked together for harmony. The projective dimension of agency refers to the “creative reconstructive dimension of agency” (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998, p. 984). To see the projective dimension of the participants' agency, the “focus upon how agentic processes give shape and direction to future possibilities” (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998, p. 984, their italics) should be considered. In her teaching diary written in 2016, the experience was described as the grateful moment that influenced the change of her mind about special education.

Third, Helen and Jade could escape from their perception of “being perfect.” Especially for Helen, being perfect was about English language use. She was worried about her language mistakes, and the worry triggered her nervousness. Through the ITP experience, she could expand her understanding of the term “perfection” and the function of language in the situation of conversation. Along with her previous lifetime experience, English was perceived as a “performative action,” rather than an “interactive action.” This led Helen to be more focused on the perfect English sentence utterance, neglecting its social and interactional function. According to Bakhtin, language itself is social. Language is “situated utterances in which speakers, in dialogue with others, struggle to create meanings” (Bakhtin, 1981, 1984, 1986 cited in Norton and Toohey, 2011, p. 416). Through the ITP, Helen could re-establish the notion of the English language, which is “social and interactional,” rather than a “performative” one.

In the case of Jade, she was a very determinative person and paid lots of attention to creating the perfect teaching material. Before the ITP, Jade was paying more attention to being the teacher who prepared things perfectly in advance, but later, the focus was expanded to be able to include the interlocutors of her classroom. Jade gained insights about the teacher's role in the classroom. Through the ITP experience, she recognized the importance of interaction with the students in the classroom. She decided to act more rather than relying on the textbooks. Her decision to be more active and selective in terms of teaching and interacting with her students also influenced the creation of a new culture in her current classroom and the achievement of her teacher agency. Her expectation to be a subjective teacher became a reality in 2018, when she was a teacher who could “make daily decisions that are difficult, involving compromise and conflict with their aspirations, feeling coerced by what [she] might see as arbitrary and unnecessary intrusions into [her] work” (Priestley et al., 2015, p. 33).

Fourth, it was also the chance to be able to recognize students in classrooms as agentive beings. In Amy's story, the local school teacher led the students to explore the real scene and then let them see and feel the practice. The safety guidance was given prior to the activity, and the things the students should avoid were explained at the scene. Teachers in the local school were creating a space to think about possible dangers in a certain area for their students. Through the experience, Amy could project her future teacher aspiration to be a person who let her students actually experience things, and she also admitted that it was a very effective way of teaching.

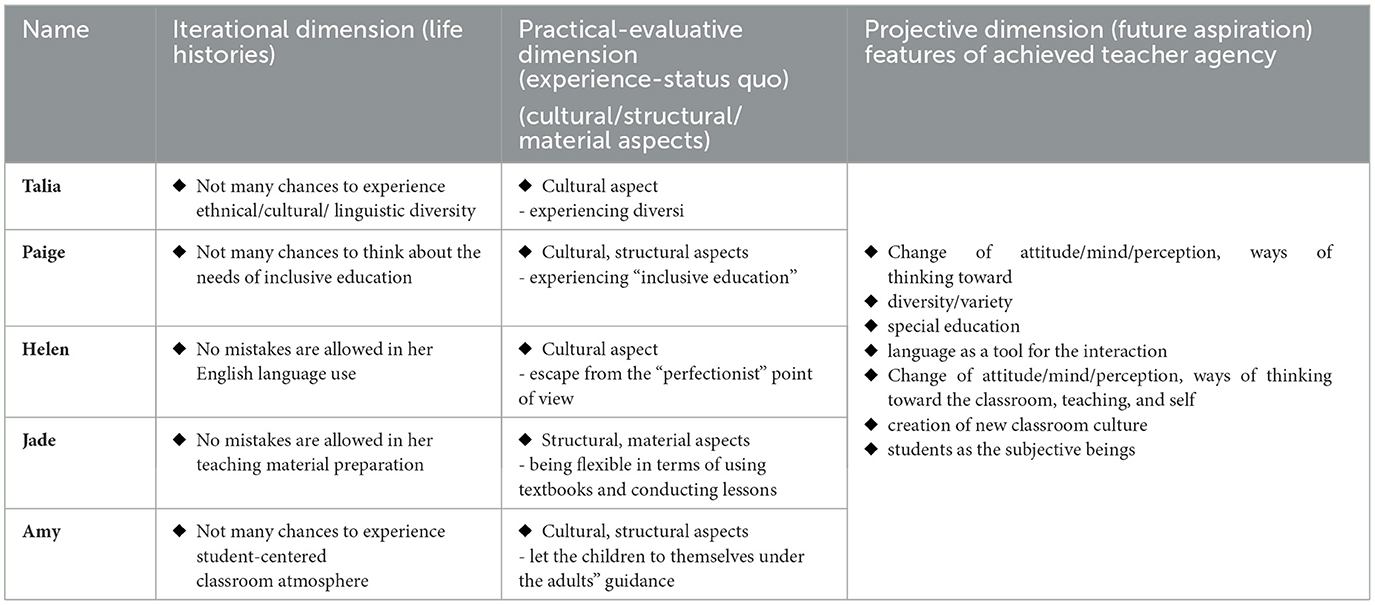

Though there is no significant boundary among the three chordal triads of agency, the characteristics of dimension from the participants' stories categorized and summarized as in Table 6.

All the dimensions of teacher agency were intertwined, each one becoming part of another, and “influenced the projective dimensions of their agentic orientations” (Priestley et al., 2015, p. 95). All the experiences of the past, present, and future became meaningful sites of learning that create the path of the participant (Anderson et al., 1996).

5.2. Which components of TPACK have been found in the ITP, and what should be complemented to construct the ITP to strengthen TPACK?

As discussed in the previous section, Korean pre-service teachers achieved insights about diversity, differences, and agency through actual exposure to the scene (Kim et al., 2020). The entire ITP program offered the chance to look back at the Korean pre-service teachers' past experience compared with the current experience, and then, they could project their future.

At the same time, the DPO played the role of the bridge to link the Korean pre-service teachers with the OTP local schools. Video clips and other internet-based resources used in the DPO allowed the Korean pre-service teachers to grasp the image and atmosphere of the scene they will be allocated for OTP. Also, it offered ideas for creating teaching materials and ways to implement them in their own teaching.

Figure 1 is one of the teaching materials that was actually used in the domestic pre-orientation programs: “ITP and the understanding of the multicultural society.” The slides contained many YouTube video clips, for example, “Westerners who see the world with nouns and Asians who see the world with verbs” (EBS docu-prime, 2009). This video clip is about the differences between the East and the West in terms of language, culture, and educational policy. The technology is integrated to link their students to the “future reality.”

Through the DPO program, the pre-service teachers could grasp the sense of utilizing video clips and photos, among others. It may be helpful in terms of indirectly transferring the knowledge of using technology in classes. Other DPO sessions' teaching materials were also reviewed, and they all contained similar technological features, such as video clips, photos, interview extracts, and teaching materials used in elementary school. The researchers of this study examined the current DPO program's teaching resources to observe whether the teaching courses in each session were enough to assist the pre-service teachers' TPACK competence as summarized in Table 7.

As shown above, the elements of CK, PK, PCK, and TK were rather significantly demonstrated in the teaching materials of the DPO program. However, the other elements of TCK, TPK, and TPACK were not clearly demonstrated. This seems because the DPO program itself was not designed to include technologies or digital competence-focused sessions, and therefore, the vivid purpose of leading the pre-service teachers to achieve technology-related competence did not appear on the surface. Though the elements of TCK, TPK, and TPACK was not significantly shown on the surface of the programme, they were underlying the whole DPO & ITP programme of G university.

To reinforce the TPACK competence strengthening, the DPO program of G University needs to draw out the technological aspects on the surface to contain sessions to enhance the understanding of various technologies that could be used in the classroom. Also, the DPO program needs to be re-designed in a convergence form of technology, contents, and pedagogy so that the elements of TPACK could be fulfilled.

6. Conclusion

This study sought answers to the following three research questions: (1) Has the international teaching practicum experience brought any changes in pre-service teachers' personalities, such as attitude, ways of thinking, perceptions of the classroom, teaching, and self? (2) In which ways was the Korean teachers' teacher agency achieved? and (3) Which components of TPACK have been found in the DPO, and what should be complemented to construct the entire ITP to strengthen TPACK?

To answer research questions (1) and (2), the combination of the three dimensions, the iterational, practical-evaluative, and projective dimensions of their action, were shown via the Korean pre-service teachers' stories through their narration that contains imagination and the reflection of their experience in the ITP (Biesta and Tedder, 2006). The entire ITP experience became the trigger of the Korean pre-service teachers' teacher agency achievement by influencing their attitude, ways of thinking, and the perceptions of classroom, teaching, and self. The OTP experience was a huge step forward for these Korean pre-service teachers as it was a procedure of layering their experience and learning in a totally new context. Through the actual allocation into the OTP country and OTP schools, which brought the engagement in good quality of “temporal-relational contexts-for-action” (Priestley et al., 2015, p. 22), the Korean pre-service teachers could achieve teacher agency.

To answer research question (3), the DPO program and its teaching resources were examined to see whether they were enough to assist the Korean pre-service teachers' TPACK competency achievement. Among the elements of TPACK, the elements of CK, PK, PCK, and TK were shown. However, the other elements of TCK, TPK, and TPACK were not shown clearly. To strengthen the whole ITP program to be more effective in terms of boosting the pre-service teachers' knowledge and skills, the DPO program certainly needs to continue focusing on the skills and knowledge of technology and its implementation. Through the DPO, the Korean pre-service teachers were trained. The original intention of facilitating the DPO program was to create scaffolding that could connect the pre-service teachers to the place where they will be facing soon. It is necessary to design the entire ITP program to be a program that helps to strengthen the varieties of competencies required of teachers in the contemporary world. Therefore, to strengthen the effectiveness of ITP, the DPO program needs to include content that could be helpful in the way of achievement of knowledge of “technologies” along with multicultural, multilingual, pedagogical, and content knowledge. At the same time, e-learning should be interactive (Nagy, 2005). Therefore, the DPO also needs to contain interaction through using technologies. Technology (T) among TPACK forms of teaching might be more needed in a kind of COVID-19 or Metaverse education, and applying chat GPT in the whole procedure of ITP could be one of the options of technology-implemented learning for future generations. To strengthen the effectiveness of the whole program of the ITP, the role of the DPO is very important.

To conclude, two of the Korean pre-service teachers narrated their ITP experiences as follows:

ITP pre-orientation program was the experience like dipping a toe in cold water before fully immersing both feet in it

[‘찬 물에 확 들어가기 전에 발가락 한 번 담가보는 정도의 경험 '(in Korean)]

(Jade. 01. Nov. 2018, Interview)

Well, I am sitting in the classroom with the students, but I can expand my experience to schools, society and the global community, and the ITP was the gate of all the expanded stories. “I have been to America, and I met these students there. They were doing this in their classroom.” Then I can give my students some topics in relation to the stories. The starting point of this, to me, this is the international teaching practicum.

(Amy. 31. October 2018, Interview)

The reality of Korean school was expressed as a pool of cold water, and the ITP experience was the moment that allowed Jade to possess responsiveness toward happenings and daily repeated tasks of her currently given context in terms of interacting with space and time. In terms of the competitive teachers who achieved teacher agency, the ITP experience itself witnessed them as global policymakers in their classrooms and schools through the pre-teachers' ITP. The ITP certainly impacted their attitude, ways of thinking, and perceptions of the classroom, teaching, and self.

The limitations of this study might be two Korean contextual issues. First, it is difficult to “do” and “achieve” teacher agency in the same environment because teachers in public schools in Korea have to transfer to other schools every 4 to 5 years. Second, as the distribution of students from various family backgrounds in Korean primary schools diverges from region to region, it is difficult to secure an opportunity to “do” and “achieve” ITP-related teacher agency. Therefore, there is a low possibility for a “Follow Up Study”.

However, this study also holds a significant strength. There were five pre-service teachers who were able to “do” and “reach” teacher agency through students from various family backgrounds, and it is highly appreciated that they were the first to do such research in ITP because they were able to participate in research interviews.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YK is the first author of this research paper and one of the instructors of the program for this study. She produced field notes in relation to this study and contributed to the data collection, analysis, and manuscript composition procedures. SY is the corresponding author of this paper. She contributed to the data collection, analysis, and manuscript composition procedures, mainly focusing on data analysis and manuscript production. YS is the whole project manager of the underlying research project that this research paper contributed to and involved in the data collection, analysis, and manuscript composition procedure. All authors have collected and analyzed the data set altogether, discussed revealed themes several times, and then produced this research paper.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea under Grant NRF-2020S1A5B8103732.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1200092/full#supplementary-material

References

Anderson, J. R., Refer, L. M., and Simon, H. A. (1996). Situated learning and education. Educ. Resear. 25, 5–11. doi: 10.3102/0013189X025004005

Barton, G. M., Hartwig, K. A., and Cain, M. (2015). International students” experience of practicum in teacher education: An exploration through internationalisation and professional socialisation. Austrian J. Teacher Educ. 40, 148–163. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2015v40n8.9

Berkley, S. (2016). In global shift, poorer countries are increasingly the early tech adopters. MIT Technology Review.

Biesta, G., Priestley, M., and Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teach. Teach. 21, 624–640. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

Biesta, G., and Tedder, M. (2006). How is agency possible? Towards an ecological understanding of agency-as-achievement. Learning lives (RES-19-25-0111). Available online at: https://bit.ly/3DEJI8g

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2012). “Thematic analysis,” in APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, ed. H. Cooper (New York, NY: The American Psychology Association) 57–71. doi: 10.1037/13620-004

Cann, O. (2017). These are the top 10 emerging technologies of 2017. Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/

Denzin, N. K. (1978). The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, 2nd ed. Piscataway: McGraw-Hill.

Doering, A., Koseoglu, S., Scharber, C, Hendrickson, J., and Lanegran, D. (2014). Technology integration in K-12 geography education using TPACK as a conceptual model. J. Geograph. 113, 223–237. doi: 10.1080/00221341.896393

EBS docu-prime (2009). Westners who see the world with nouns and Asians who see the world with verbs. Available online at: https://youtu.be/J5hOkggR_nk

Emirbayer, M., and Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? Am. J. Sociol. 103, 962–1023. doi: 10.1086/231294

Farrell, S. C. T. (2016). From Trainee to Teacher; Reflective Practice for Novice Teachers. Sheffield, Bristol: Equinox.

Fries, L. (2017). Tech for dinner: how our food is changing as fast as our iPhones. World Economic Forum.

Hughson, T. A., and Wood, B. E. (2020). The OECD Learning Compass 2030 and the future of disciplinary leaning: a Bernsteinian critique. J. Educ. Policy. 37, 634–654. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2020.1865573

Instefjord, E. J., and Munthe, E. (2017). Educating digitally competent teachers: A study of integration of professional digital competence in teacher education. Teach. Teacher Educ. 67, 37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.016

Jin, A., Parr, G., and Hui, L. (2020). “The sun is far away, but there must be the sun': Chinese students” experiences of an international teaching practicum in China. Educ. Res.62, 474–491. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2020.1826340

Kim, D. H. (2017). TPACK as a research tool for technology integration into classroom: a review of research trends in Korea. J. Element. Educ. 30, 1–22. doi: 10.29096/JEE.30.4.01

Kim, Y. O. (2018). The 4 th industrial revolution and students with learning disabilities. J. Lear. Strat. Interv. 9, 1–20.

Kim, Y. O., and Yun, S. (2019). The development of a standard model of international teaching practicum program: the formation of procedural structure and detailed elements of the contents. Teach. Pract. Res. 1, 47–62. doi: 10.35733/tpr.2019.1.1.47

Kim, Y. O., Yun, S., and Sol, Y. H. (2020). An exploratory study on the feasibility of on-line international teaching practicum of Korean Educational Universities. Global Creat. Lead. 10, 133–160.

Kim, Y. O., Yun, S., and Sol, Y. H. (2021). The long-term effects of an international teaching practicum: the development of personal and professional competences of Korean pre-service teachers. KEDI J. Educ. Policy 18, 3–20. doi: 10.22804/kjep.2021.18.1.001

Kim, Y. O., Yun, S., and Sol, Y. H. (2022). Effects of enhancing multicultural knowledge competence through an international teaching practicum programme for Korean student-teachers. Asia Pacific J. Educ. 42, 679–698. doi: 10.1080/02188791.2020.1798739

Kim, Y. O., Yun, S., Sol, Y. H., and Seo, C. (2019). The Effectiveness of Enhancing Multi-cultural competence thru the Orientation program in developing an international teaching practicum for pre-service elementary school teachers. J. Learner-Center. Curric. Instr. 19, 183–215. doi: 10.22251/jlcci.2019.19.11.183

Koehler, M. J., and Mishra, P. (2008). “Introducing technological pedagogical content knowledge,” in Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) for educators, ed. AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology (New York: Routledge) 3–29.

Lave, J. (1992). Teaching, as learning, in practice. Mind Cult. Activ. 3, 149–164. doi: 10.1207/s15327884mca0303_2

Mishra, P., and Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for integrating technology in teachers' knowledge. Teach. College Rec. 108, 1017–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

Nagy, A. (2005). “The impact of E-Learning,” in E-Content, eds. P. A., Bruck, Z., Karssen, A., Buchholz, A., Zerfass (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer).

Niess, M. L. (2011). Investigating TPACK: Knowledge growth in teaching with technology. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 44, 299–317. doi: 10.2190/EC.44.3.c

Niess, M. L., Ronau, R. N., Shafer, K. G., Driskell, S. O., Harper, S. R., Johnston, C., et al. (2009). Mathematics teacher TPACK standards and development model. Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 9, 4–24.

Norton, B., and Toohey, K. (2011). Identity, language learning, and social change. Lang. Teach. 44, 412–446. doi: 10.1017/S0261444811000309

OECD (2015). OECD learning Compass 2030. Available online at: http://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/learning-compass-2030/ (accessed August 10, 2023).

Park, M. H., and Kim, K. S. (2015). Development of a multicultural competence scale for pre-service teachers. Multic. Educ. Stud. 8, 1–37. doi: 10.14328/MES.2015.9.30.01

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., and Robinson, S. (2015). “Teacher agency: what is it and why does it matter?” in Flip the System: Changing Education form the Bottom Up, eds. R. Kneyber. and J. Evers (London: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781315678573-15

Priestley, M., Edwards, R., Miller, K., and Priestley, A. (2012). Teacher agency in curriculum making: agents pf change and spaces for manoeuvre. Curric. Inquiry 42, 191–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-873X.2012.00588.x

Schmidt, D. A., Baran, E., Thompson, A. D., Mishra, P., Koehler, M. J., and Shin, T. S. (2009) Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK). J. Res. Technol. Educ. 42, 123–149. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2009.1078254

Stachowski, L. L., and Sparks, T. (2007). Thirty years and 2,000 student teachers later: An overseas student teaching project that is popular, successful, and replicable. Teach. Educ. Quart. 34, 115–132. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23478855

Tang, S. Y. F., and Choi, P. L. (2004). The development of personal, intercultural and professional competence in international field experience in initial teacher education. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 5, 50–63. doi: 10.1007/BF03026279

TPACK homepage. (2012). http://tpack.org/ (accessed August 10, 2023).

Walters, L. M., Garii, B., and Walters, T. (2009). Learning globally, teaching locally incorporating international exchange and intercultural learning into pre-service teacher training. Interc. Educ. 20, 151–158. doi: 10.1080/14675980903371050

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. UK: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511803932

Willard-Holt, C. (2001). The impact of a short-term international experience for preservice teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 17, 505–517. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00009-9

Wilson, A. H. (1993). Conversation partners: helping students gain a global perspective through cross-cultural experiences. Theory Pract. 32, 21–26. doi: 10.1080/00405849309543568

Keywords: international teaching practicum (ITP), Korean pre-service teachers, teacher agency, teacher training, TPACK

Citation: Kim YO, Yun S and Sol YH (2023) Analysis of an “international teaching practicum” as a program for achieving “teacher agency” and strengthening “technological pedagogical content knowledge”. Front. Educ. 8:1200092. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1200092

Received: 04 April 2023; Accepted: 07 August 2023;

Published: 31 August 2023.

Edited by:

Fika Megawati, Universitas Muhammadiyah Sidoarjo, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Kivanc Bozkus, Artvin Çoruh University, TürkiyeElla Fitriani, Jakarta State University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2023 Kim, Yun and Sol. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Soyoung Yun, c295b3VuZ3l1bjA3MjVAZ21haWwuY29t

†ORCID: Youn Ock Kim orcid.org/0000-0001-5774-3209

Soyoung Yun orcid.org/0000-0002-0114-2188

Yang Hwan Sol orcid.org/0000-0001-9087-8631

Youn Ock Kim1†

Youn Ock Kim1† Soyoung Yun

Soyoung Yun