- 1Department of Health Sciences, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, United States

- 2Department of Early Childhood, Western New Mexico University, Silver City, NM, United States

- 3Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, United States

- 4School of Social Work, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, United States

- 5Health Sciences Center, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, United States

- 6Bilingual Multicultural Services Inc., Albuquerque, NM, United States

- 7National University, La Jolla, CA, United States

Purpose: Neurodivergent children who are part of Indigenous communities in rural areas often have inequitable access to specialized services. Parent education and training programs can be used to help address these gaps in the service system. Yet few parent education and training programs exist for Indigenous parents of children with autism, including parents who identify as Diné (Navajo, meaning “The People”), the largest federated tribe in the United States. The Parents Taking Action (PTA) program is a parent education and training program delivered by community health workers that was originally developed for Latine parents of children with autism. The PTA program has been culturally adapted for other groups, and a growing evidence base exists supporting the program’s feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy. We, therefore, sought to adapt the PTA program for Diné parents.

Methods: This was a community-engaged case study on how the PTA program was adapted for Diné parents of children with autism. A community advisory board (CAB) comprised of 13 individuals including Diné parents of children with autism and professionals helped guide the adaptation process. We interviewed 15 Diné parents of a child with autism about their needs and preferences for the PTA program and used this information to adapt the PTA program. CAB workgroups used the Ecological Validity Framework to provide input on adaptations needed for the original PTA program materials. We also obtained input on the program’s adaptation from Diné communities and a PTA research collaborative.

Results: To incorporate the CAB’s collective feedback on the PTA program adaptation, we modified terminology, visuals, and narratives. From the parent interview findings, we reduced the number of lessons and enabled community health workers to deliver lessons remotely. We further integrated feedback from the CAB workgroups in the adaptation of specific lessons. We addressed feedback from the larger community by expanding our project’s catchment area and involving additional programs.

Conclusion: This case study demonstrates how an evidence-based, parent education and training program was adapted for Diné parents of children with autism. The adapted Diné PTA program is being piloted. We will continue to improve Diné PTA by using the pilot’s results and community input to inform future adaptations.

1 Introduction

Indigenous children and their families, including those who identify as being of Diné descent (Navajo, meaning “The People”), have inequitable access to services for autism spectrum disorder (hereinafter referred to as autism; Sullivan, 2013; Travers and Krezmien, 2018). Autism is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition characterized by issues with social communication and restricted and repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Autism is increasingly identified before or around the time children begin primary school, with approximately 1 in 36 U.S. children presently estimated to have autism (Maenner et al., 2023). Although no formal epidemiologic assessments of autism prevalence and related services use have been conducted among Diné children, preliminary findings from the Navajo Birth Cohort Study—part of the National Institutes of Health Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes program—suggest that autism may be as or more prevalent among Diné children (Hunter et al., 2015; Rennie et al., 2023).

Families may have positive and negative experiences related to raising children with autism (Kearney and Griffin, 2001; Taunt and Hastings, 2002). On the positive side, parents or primary caregivers (hereinafter parents/guardians) may feel that their experience is a source of strength and family closeness, helps them to find purpose, and is an opportunity for hope and growth (Kayfitz et al., 2010; Beighton and Wills, 2017). Conversely, adverse financial and employment impacts are common for families of children with autism (Lavelle et al., 2014; Zuckerman et al., 2014) along with heightened parental stress (Schieve et al., 2011; Lindly et al., 2022), as well as unmet service needs (Lindly et al., 2016). Moreover, children with autism are likely to experience poor health outcomes relative to other children including lower quality of life (Kuhlthau et al., 2010), poorer school performance (Wei et al., 2011), lower wages earned as adults (Queirós et al., 2015), and reduced life expectancy (Guan and Li, 2017).

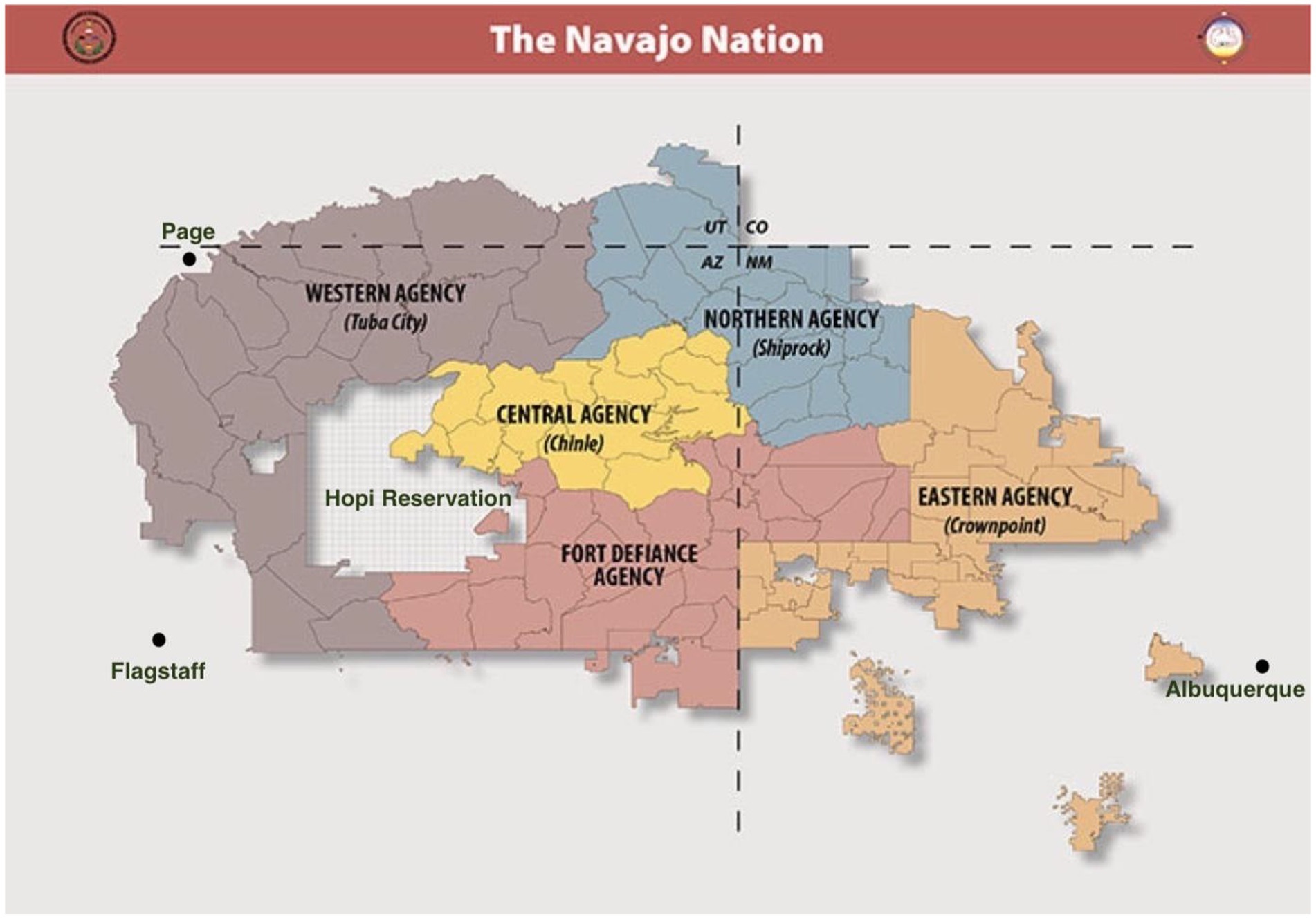

The rural nature of where many tribal nations are located often contributes to poor service access among Indigenous neurodivergent children, including those with autism (Sullivan, 2013; Bishop-Fitzpatrick and Kind, 2017; Travers and Krezmien, 2018; Aylward et al., 2021). The Navajo Nation, for example, is the largest federated tribe in terms of both its population size (~165,158 Diné individuals are estimated to live within the borders of the Navajo Nation) and its geographic size (~17 million acres or 25,000 square miles). The Navajo Nation is in the Southwestern United States, with borders spanning Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah (Figure 1). The Diné are historically nomadic with clusters of homes scattered throughout rural areas with towns of less than 10,000 individuals. In some areas, the population density is only six people per square mile. Many Diné families have low household incomes (e.g., the median household income in Navajo Nation is $25,827; Combrink, n.d.). A challenge for many Diné families, therefore, is limited access to specialists given the ruralness of the Navajo Nation, confounded by families’ limited financial resources, lack of access to public and individually owned transportation, and dirt roads that may be impassable during periods of heavy snow and rain. Many health professionals are in urban areas such as Phoenix, Arizona or Albuquerque, New Mexico that are considerable distances for Diné families to travel to from the Navajo Nation (Bennett et al., 2021). Thus, it is not uncommon for families to relocate closer to a city, change career paths, and/or acquire a second job to afford travel to and the cost of health-related services (DePape and Lindsay, 2015; Lindly et al., 2023).

Figure 1. Map of the Navajo nation with agency councils and certain border towns [adopted with permission from the Navajo Nation Land Department [Cartographer] (n.d.)]. This figure displays the location of the five Navajo nation agency councils in relationship to state boundaries, the Hopi reservation, and three large border towns such as Flagstaff, Arizona.

Historically, Diné parents of children with autism and other developmental disabilities have endured a very limited system of care, often having to place their child in a residential facility or provide at-home care for their child with little to no support (O'Neal et al., 1987). Although funding has increased for individuals with disabilities in the United States, including for those who have autism (Harvey et al., 2010), Diné parents of children with autism continue to experience barriers to accessing services such as long distances to service providers, limited internet connectivity for telehealth services, and competing priorities related to their education, employment, and other family members (Lindly et al., 2023). The intersection of ruralness, poverty, and sociocultural factors unique to Diné families likely affects their experiences raising children with autism.

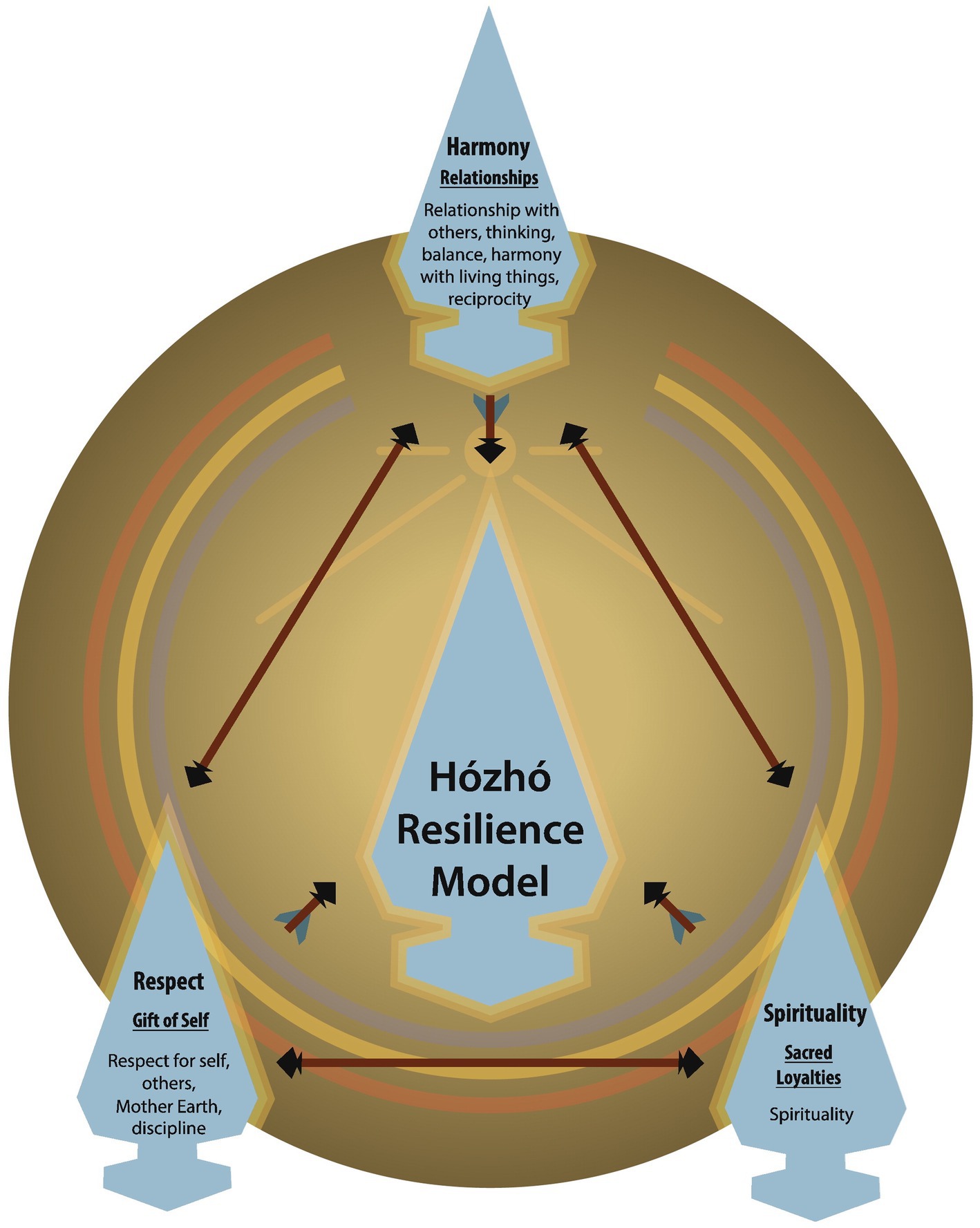

The Diné Hózhó (harmony and balance) philosophy is one that transcends developmental disabilities in favor of an idea of interconnectedness and harmony (Kapp, 2011). The concepts inherent in the Hózhó Resilience Model (Figure 2; Kahn-John, 2016) have supplanted the need for specific disability language. Beyond descriptive terminology, there are presently no words in the Diné language for disabilities or specific conditions, such as autism (Frankland et al., 2004), which is to some extent aligned with the worldview of other Indigenous communities such as the Māori (Berryman and Woller, 2013; Tupou et al., 2023). For this reason and given preferences expressed by this project’s community advisory board members and this paper’s authors who identify as Diné, person first language is used when referring to children with autism. Nevertheless, we recognize that the use of identity first language (i.e., autistic children) is part of the neurodiversity movement and reflects that autism is a social identity and culture (Botha and Gillespie-Lynch, 2022). We further understand that identity first language may be preferred by members of the larger autistic community including other Indigenous populations such as the Māori (Tupou et al., 2023).

Figure 2. The Hózhó resilience model [adopted with permission from Kahn-John (2016). This figure displays the three principles of the Hózhó resilience model including harmony, respect, and spirituality.

Moreover, Diné medicine is pluralistic and may involve the presence of traditional healers and special ceremonies as a complement to western or mainstream medicine (Van Sickle et al., 2003). The concept of K’é (kinship) is a fundamental principle in all aspects of tribal life. The kind of Native healing performed depends on what a healer determines the root of the condition to be. The traditional intervention process may involve diagnosticians, medicine people, and herbalists as practitioners in ceremonies (Vining, 2000). Those identified as ill may undergo these ceremonies to integrate the individual into full acceptance with the universe and the community allowing them to be cured (Kapp, 2011). At times, traditional beliefs may bring about guilt for families, especially parents, as disability may be perceived as the consequence of an action during pregnancy or at another time (Connors, 1992; Vining, 2000). These and other sociocultural factors (e.g., ruralness, poverty) likely interact to impede Diné parents’ access to autism services for their children.

Programs that utilize community-based social care models for Indigenous individuals with disabilities show promise for reducing pronounced and persistent health disparities (Puska et al., 2022). In the Navajo Nation, for example, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) Part C Early Intervention program Growing in Beauty (GIB) provides services to Diné children with developmental disabilities and their families. GIB also provides service coordination to help children transition from early intervention to local education agencies who are responsible for special education and related services for preschool and older children with disabilities. GIB provides advocacy and training for families and delivers assessments and evaluations for at-risk children (Navajo Nation Department of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services, n.d.). However, Part C mandates that early intervention services such as those provided by GIB only be available for children who are younger than three-years-old. School-based services for children and adolescents with autism who are ages 3–21 years may be provided under the IDEA Part B but are mostly focused on the child’s goals as opposed to the family’s (Sarche et al., 2011). Part D of the IDEA governs the federal grants that are aimed toward enhancing school-based services for children with disabilities. This includes parent training and information centers which, along with the schools, are responsible for making sure families have the knowledge and skills to be active participants in the services their child receives at school (Banks and Miller, 2005). In Arizona, Raising Special Kids is the parent training and information center that serves the entire state; however, few families served identify as Indigenous (Raising Special Kids, 2021). This suggests there may be opportunity to improve access to training and education resources for Diné and other Indigenous families.

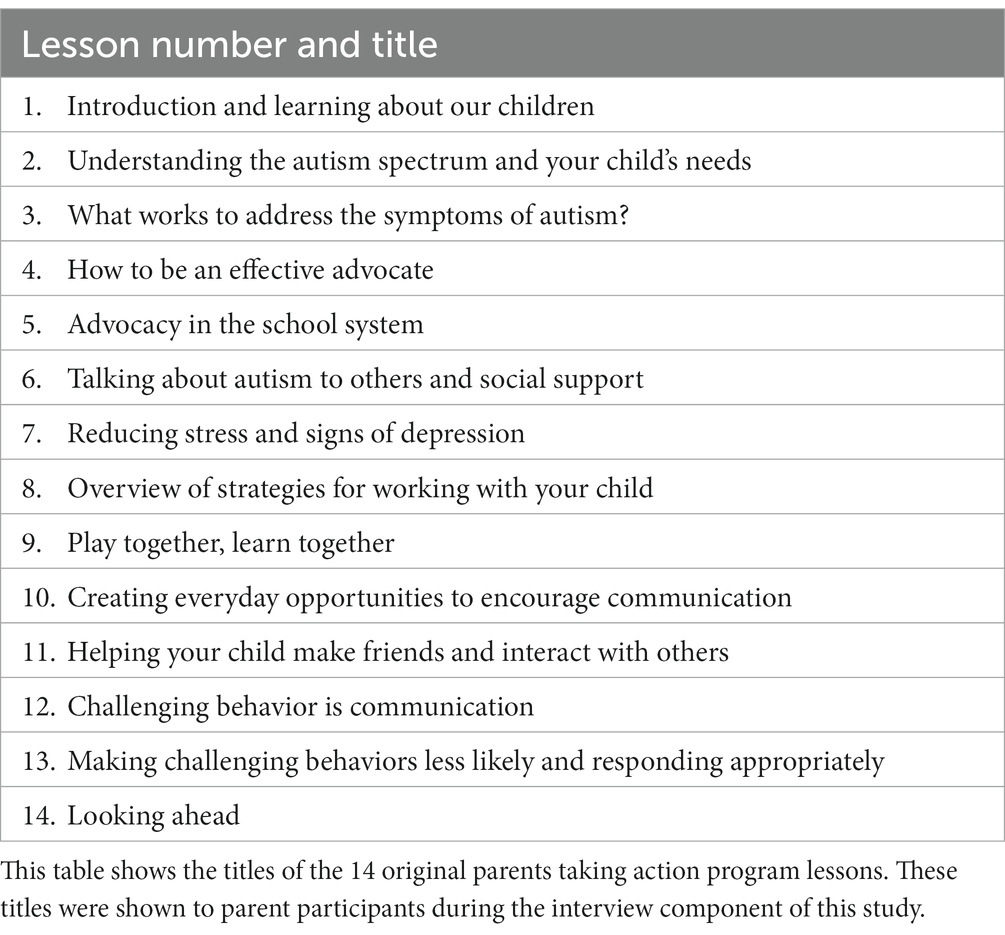

One of the programs that uses the community-based social care model with families of children with autism is the Parents Taking Action (PTA) program, which is a culturally informed psychoeducation program originally developed for Latine parents of children with autism (Magaña et al., 2017). A growing evidence base exists supporting the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy (e.g., improved child social communication) of the PTA program for Latine parents of children with autism (Lopez et al., 2019; Magaña et al., 2019, 2020) and increasingly in other culturally and linguistically diverse groups such as Black and African American parents (Dababnah et al., 2022) and parents who identify as Chinese immigrants (Xu et al., 2023). PTA is typically delivered by promotoras de salud, or community health workers. The promotora de salud model is a community involved approach to health information delivery (Cupertino et al., 2013). Typically promotoras are community members who are taught to deliver health information on a specific topic. PTA promotora criteria is particularly unique in that PTA promotoras are other Latina mothers of children with autism. The shared culture as well as maternal understanding of parenting a child with autism has been identified as especially impactful to participant experience in PTA (Magaña et al., 2014). The PTA program originally included 14 lessons that were delivered by promotoras to parents (Table 1). In addition to the qualitative findings on the delivery mode of PTA, a randomized controlled trial found that Latine families had improved knowledge of autism, elevated self-efficacy of using evidence-based strategies and frequency of using the strategies and increases in family outcomes post intervention (Magaña et al., 2017, 2020; Lopez et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2022).

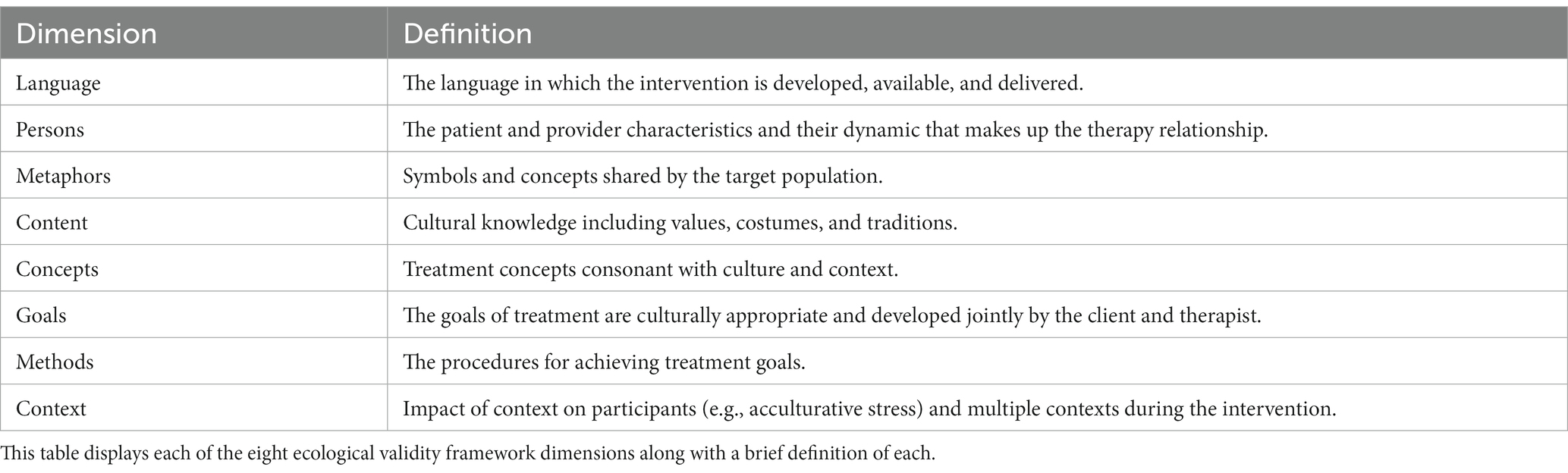

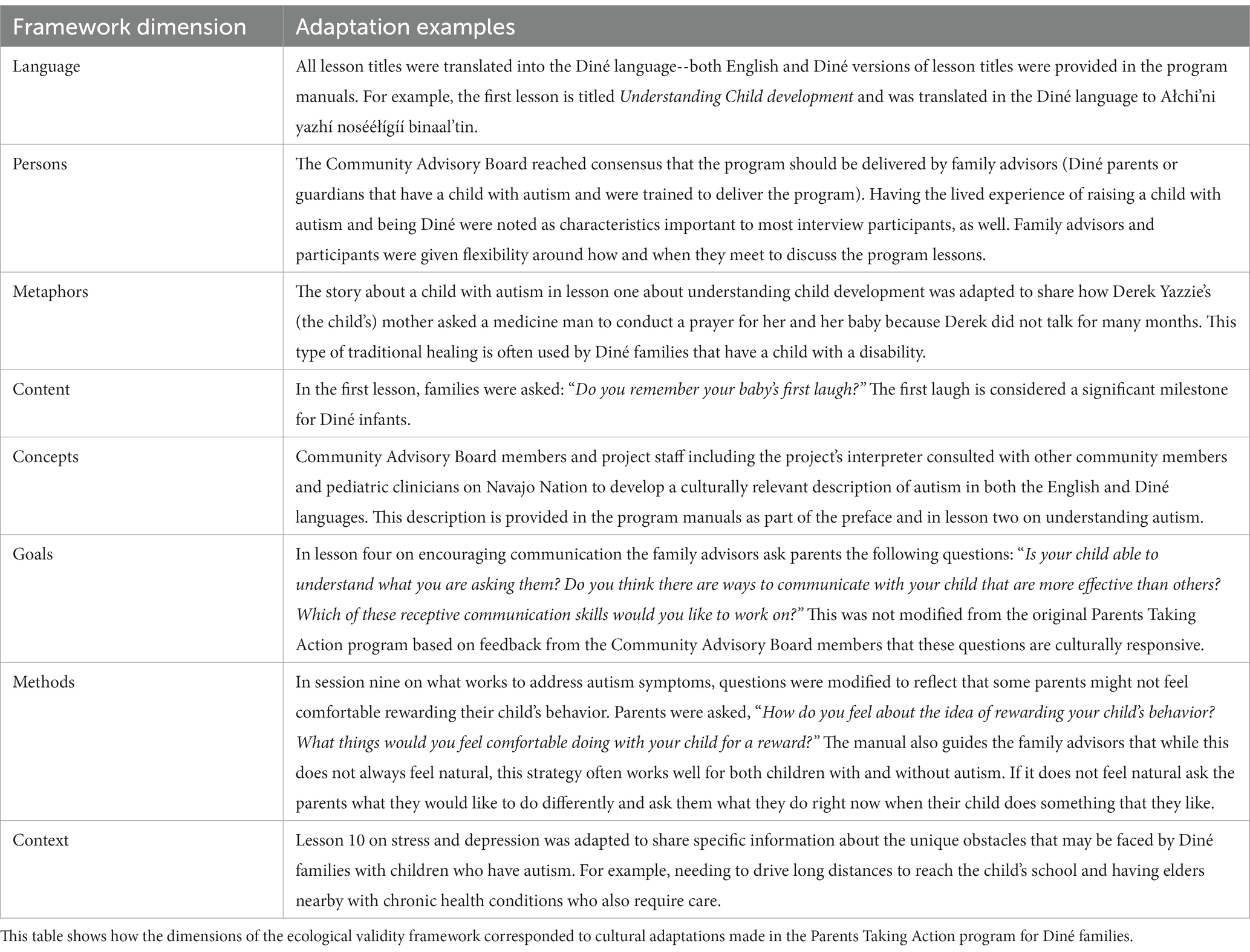

Given the positive research findings and community reception of PTA, numerous researchers have adapted PTA for use with other Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC). Each adaptation has adhered to the Ecological Validity framework (Table 2) to guide decisions for cultural adaptations. Dababnah et al. (2022) adapted PTA for Black families of children with autism in Baltimore, Maryland. A community advisory board composed of mothers and grandmothers of Black children with autism, a self-advocate, service providers, and other key stakeholders in Baltimore steered the adaptation process. The changes made to PTA included the renaming of promotoras to parent leaders, reorganization of sessions, changing of story examples, photos, and video narrations to be about or include Black persons, updated video links, revision of the content to center child and family strengths and lean into the DSM-V criteria, and the inclusion of police information in the advocacy session. In another example, PTA was adapted to meet the needs of parents of children with autism in Bogotá, Colombia (Magaña et al., 2019). Magaña et al. (2019) found decolonization to be central in the adaptation process as they worked with families in Colombia. It was expected that families would not attend to the promotora model due to the high value placed on respeto, or respect for authority. Thus, the researchers included delivery by pre-professionals to compare the acceptability of authority delivered programming compared to peers and used terminology better aligned with the Colombian culture (Magaña et al., 2019). Xu et al. (2023) adapted PTA for Chinese immigrant families of children with autism. Based on focus group findings with the target population of parents and providers, PTA Chinese included changes to the training process of training promotoras, extended sessions, and delivery of PTA in groups rather than one-on-one. In addition, COVID-19 pandemic modifications were needed for PTA Chinese including program delivery to participants via telehealth.

Table 2. Ecological validity framework dimensions and definitions (adopted from Bernal et al., 1995).

Overall, these past studies demonstrate the importance of intentionality, community engagement, and flexibility in the successful adaptation of PTA for use with other BIPOC communities. Few parent education and training programs, including PTA, however, currently exist for Indigenous families of children with autism including those who identify as Diné. Because the Diné and other Indigenous communities in rural areas of the U.S. frequently use community health workers (e.g., community health representatives) to deliver health education and training programs and given the robust cultural adaptation and evidence supporting PTA, we sought to adapt the PTA program for Diné families who have a child with autism. We did so using a community-engaged approach, which we describe as a case study on how the PTA program was adapted for Diné parents of children with autism.

2 Methods

We employed a single case study design to describe how the PTA program was adapted for Diné parents of children with autism using a community-engaged approach (Yin, 2009). According to Yin (2009):

“The essence of a case study, the central tendency among all types of case study, is that it tries to illuminate a decision or set of decisions: why they were taken, how they were implemented, and with what result” (p.17).

Here, the case being studied was the community-engaged adaptation of the Parents Taking Action program for Diné parents of children with autism. Our two main sources of data for this case study were (1) the primary qualitative data gathered through semi-structured, in-depth interviews conducted with 15 Diné parents of one or more child(ren) with autism from June 2021 to June 2022, and (2) the input gathered from our community advisory board (CAB) members from 2021–2022 on how to adapt the PTA program materials for Diné families. Additionally, we obtained input on the adaptation process for this study in 2020 and 2021 from a PTA research collaborative led by Dr. Sandra Magaña and others who have developed and/or adapted the program for various cultural groups in the United States and internationally. This study was approved by the Northern Arizona University Institutional Review Board and the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board. We also adhered to any local or organizational approval processes required to recruit individuals in various communities across the Navajo Nation. As part of these ethical review processes, we additionally obtained input on this larger Diné PTA pilot project from various government entities and organizations, such as the Navajo Nation Agency Councils.

2.1 Researcher positionality statement

Our interdisciplinary research team for this case study was comprised of four Diné individuals, including one individual who also identified as the parent of a child with autism and two individuals who identified as service providers working with children with autism and their family members in and around the Navajo Nation. Our research team additionally included one Latina individual, and two individuals who identified as neurodivergent. Several of our research team members also identified as being the sibling of an autistic individual, and as being the parent of young or adolescent aged children. The disciplinary backgrounds of our research team members span public health, speech and language pathology, special education, social work, psychology, biology, and child development. All research team members live or have previously lived in the Southwestern United States.

2.2 The Ecological Validity Framework

In alignment with the original PTA development for Latine families of children with developmental conditions and subsequent adaptations for autism and other cultural groups (Lopez et al., 2019; Magaña et al., 2019, 2020; Dababnah et al., 2022), we used the eight dimensions of the Ecological Validity Framework (Table 2) to guide our adaptation of the PTA program materials for Diné families of a child with autism (Bernal et al., 1995). The eight Ecological Validity Framework dimensions are as follows: language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods, and context. Table 2 provides a brief description of each dimension. Recent work on cultural adaptation by Lee et al. (2023) suggests that content, concepts, and metaphors may be combined into a single “content” dimension and the additional dimension “process” (i.e., the iterative and collaborative nature of cultural adaptation) may be useful to consider. However, for this study we maintained the original eight dimensions.

2.3 Interviews about PTA adaptation with Diné parents of children with autism

Because the interviews with Diné parents about the PTA program adaptations also covered their lived experiences accessing diagnostic and treatment services for their child’s autism as part of the larger Diné PTA pilot project, a detailed description of the interview methodology is provided elsewhere (Lindly et al., 2023). In summary, a purposive sample of 15 parents ages 18 years or older who self-identified as Diné and as having one or more child(ren) with autism age 2–12 years were recruited through multiple sources (e.g., CAB member referrals, Navajo Nation Head Start referrals, social media) in and around the Navajo Nation. After individuals expressed interest in participating, a brief eligibility screener was completed. Eligible individuals were then asked to provide verbal informed consent. Participants subsequently completed a brief, verbally-administered survey about their demographic characteristics and those of their child(ren) with autism followed by a semi-structured interview, both of which were conducted by a Diné study team member. If participants had more than one child with autism, they responded to the survey and interview questions about the youngest child with autism. The interview questions were used in previous Parents Taking Action adaptations conducted (i.e., Dababnah et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2023). The semi-structured interview guide including questions and probes was collaboratively adapted with input from the project’s CAB. Table 3 shows the interview questions and directed probes on preferences for the PTA adaptations, and Table 1 includes the lesson topics that were referenced during each interview. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Each interview participant received a $30 gift card.

Table 3. Interview guide questions and directed probes on parents taking action program adaptations with magnitude coding summary.

2.3.1 Interview participant characteristics

Ten interview participants lived in the Navajo Nation with regional representation as follows (see Figure 1 for a map of the Navajo Nation Agency Council regions): one participant from the Eastern Navajo Agency (Crownpoint), two participants from the Fort Defiance Navajo Agency, three participants from the Central (Chinle) Navajo Agency, and four participants from the Western Navajo Agency (Tuba City). In addition, five participants resided in border towns such as Page, Arizona or in Phoenix, Arizona. Almost all participants (n = 14, 93%) identified as female and the mother of the child with autism. The median age of the participants was 34.5 years. Only two participants (13.3%) indicated having good or excellent proficiency in speaking the Diné language, and none indicated having good or excellent proficiency writing in the Diné language. The remainder of participants indicated having poor or fair proficiency in speaking (n = 13; 86.7%) and in writing (n = 15) in the Diné language. Most participants were married or living with a partner (n = 10; 66.7%). Two participants (13.3%) indicated having their highest level of education attained as a bachelor’s or master’s degree, while four participants (26.7%) indicated having completed some college and nine participants (60%) indicated having earned a high school diploma. Nine participants (60%) were not employed, and seven participants (46.7%) had an annual household income of less than $25,000. Most participants indicated that their overall health status was good (n = 9, 60%) or excellent (n = 2, 13.3%), while the remainder of participants indicated they had fair (n = 3, 20%) or poor (n = 1, 6.7%) overall health status. Three participants (20%) had two children with autism, and the rest of participants (n = 12, 80%) had one child with autism. The median age of parents’ children with autism was 6 years. A plurality of children with autism were male (n = 12, 80%), and all were identified by parents as being Diné. Two children with autism (13.3%) were also identified as belonging to other tribes (i.e., Hopi or Sioux), and one child (6.7%) was also identified as Latino. Nine children (60%) were reported to have low versus moderate or high support needs, and six children (40%) we reported to require substantial support with activities of daily living.

2.3.2 Interview data analysis

We used a summative content analysis approach to analyze the interview data, whereby the intention was to identify and quantify certain words and phrases to help understand participant preferences for the PTA program and its adaptations for Diné families of children with autism (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). In applying this approach, elemental and magnitude coding methods were used (Saldaña, 2015). For example, under the structural code “program content” the descriptive code “cultural adaptations for the program” was used to capture information provided by participants regarding their preferences for what types of cultural adaptations they would like to see made in the PTA program materials. Additionally, magnitude coding was used to quantify the number of participants who expressed that they thought cultural adaptations specific to Diné families should be made. Two study team members, including one who identifies as Diné, independently coded each transcript and then compared their coding to check for consistency, modify the coding scheme, and resolve differences in coding through discussion and reaching consensus. Coding results were also presented back to the CAB at one meeting and at several community presentations to obtain broader feedback. All qualitative data analysis was performed in QSR NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2020).

2.4. Community advisory board member formation

To initially establish our CAB, we asked several individuals who had agreed to be part of the CAB prior to this project being funded if they had recommendations of other individuals whom we should contact to join the CAB. These included individuals representing different community-based organizations and institutions serving Diné children with autism and their families. We additionally asked our initial CAB members to refer any Diné parents/guardians of children with autism whom they thought might be interested in serving on the CAB in a parent advisor capacity. In doing so, we created a flyer describing the parent advisor role. We circulated this flyer to community-based organizations serving Diné families on and around the Navajo Nation (e.g., the Growing in Beauty Early Intervention program, Navajo Head Start). Between April 2021 and January 2022, we were able to recruit four parent advisors to our CAB. We offered parent advisors serving on our CAB a stipend of $200 each. Our project’s CAB consisted of 13 individuals in total. From April 2021 to May 2022, we had 12 CAB meetings through video conference (i.e., Zoom) during which we primarily discussed the project’s community engagement, participant recruitment strategies, and the adaptation of the existing parent education and training materials for Diné parents. The CAB has continued to meet every other month since September 2022 to focus on the larger project’s implementation, evaluation, dissemination, and sustainability activities.

2.5 Community advisory board member input on PTA adaptation for Diné families

In terms of the CAB’s work to help adapt the PTA program materials for Diné families, three members of the research team sought overarching feedback from the full CAB during regular meetings on broader adaptations to the program such as the project’s logo and commonly used terminology throughout the program materials. This input was recorded in meeting notes taken by the project’s coordinator or another member of the research team. In addition, we sought to obtain more detailed feedback from the CAB on adaptations needed for the PTA manuals, which include lessons on the program’s content. To obtain this feedback, we distributed copies of PTA manuals including program visuals from the original PTA program and subsequent adaptations from its developers and collaborators to the CAB members. We then formed smaller workgroups of volunteers from our CAB that were composed of two to four individuals to review and provide feedback on the adaptations needed for one or two lessons at a time. The duration of each workgroup session was no longer than an hour. For each workgroup, we included at least one parent advisor; therefore, at least one member of the workgroup was of Diné descent. At times certain CAB members were specifically asked to join these workgroups if their area of expertise matched the lesson topic being reviewed. Each workgroup was provided with the lessons assigned and was briefed on the Ecological Validity Framework dimensions (Table 2). Workgroups were also provided with a set of questions (i.e., How can we improve the cultural relevance of the given lesson’s content?; What are your thoughts on the cultural appropriateness of the images and stories used for the given lesson?: Where should Diné words be incorporated?; and Should any other changes be made to the given lesson, so it is better received by Diné families?) and the Ecological Validity Framework dimensions and definitions to consider in providing input. Each workgroup was provided one to two weeks to review and provide feedback on the lesson(s) they were assigned prior to meeting with one or two members of the research team by video conference to discuss their feedback. The discussion of workgroup feedback was recorded and then integrated into the manual lessons by the research team members. The research team members then asked CAB members to review the adaptations made and modified the lesson materials further if CAB members indicated that additional adaptation was needed.

3 Results

3.1 Parent interview results on PTA adaptations

Results from the analysis of the interview data are summarized in Table 3. Additional information and exemplary quotations are provided to convey interview participants’ preferences more fully regarding PTA program adaptations for Diné families. We organize this information in terms of delivery preferences for the program and content adaptation preferences for the program.

3.1.1 Results on preferences for PTA delivery

Nine participants (60%) said that they would prefer the PTA program be delivered by another Diné parent of a child with autism because they would have similar lived experiences (e.g., living on the reservation, being in a rural area, living in poverty) and would, in turn, feel more comfortable working with that person. One participant elaborated on this by stating:

“[B]ecause if they’re on the rez as well, I kind of know their living situation, like how we do have to travel to go to the nearest Walmart. We’re not just right down the street. Or how we do experience that there’s not enough programs out on the reservation. Someone who lives somewhat my lifestyle, rather than somebody who’s a rich, wealthy person who can afford private specialists.”

Participants also commonly mentioned that it was important for the person delivering the PTA program to be a parent, and in some cases more specifically be the parent of a child with autism. Participants described this as making it easier to relate to the person delivering the program. One parent further explained this by stating, “Just as long as they have an autistic child and actually know what it’s like to raise a child with autism.” Most participants did not have a gender preference for the person delivering the program (Does not matter n = 11, 73.3%; Female: n = 3, 20%; Male: n = 1, 6.7%). Other characteristics that participants noted as important for the individual delivering the program were that they be respectful, friendly, and comfortable around the child with autism (n = 3), and that the person delivering the program be knowledgeable about autism (n = 1). When asked about their preference for whether the program be delivered individually (one to one), in a small group, or individually and in a small group, most participants said they would like a mix of individual and small group based delivery (n = 9, 60%). Participants who talked about having a preference for small group based delivery frequently noted that it would be more conducive for collaboration, brainstorming (“learning from others”), and social support. Whereas those participants with a preference for individual delivery said that it may be better for people who “do not really want to open up” or if scheduling a group is logistically challenging. One participant suggested that a sequential approach to mixing individual and small group-based delivery would be desirable as follows:

“I think [parents] would be more comfortable as individuals first and then as they come to trust and maybe feel more comfortable, then I think it could turn into a group, so that they know that they’re not the only family alone there with the child with autism.”

When asked how often the program lessons should be taught, nine participants (60%) said their preference would be for the lessons to be taught weekly for about an hour each. Participants explained that this frequency and duration would be helpful in terms of scheduling feasibility with their other responsibilities and their ability to easily recall the prior lesson’s material. All participants agreed that the lessons should be delivered virtually with one of these participants stating that both virtual and in-person program delivery would be preferred. Many participants mentioned that virtual delivery was safer due to the ongoing risks posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some participants noted that virtual delivery was more comfortable for them given their caregiving responsibilities and also due to the initial dynamic of not knowing and trusting the individual delivering the program.

3.1.2 Results on preferences for PTA content adaptations

Parents were shown a list of the original PTA lesson titles (Table 1) and were then asked questions regarding the sessions without knowledge of the lesson’s full content. In response to their review of the 14 original PTA lesson topics, 10 participants (66.7%) stated that the second lesson on “Understanding the Autism Spectrum and Your Child’s Needs” would be the most useful for Diné families. The rationale many participants provided for this centered around wanting a better understanding of autism for themselves and others. One participant elaborated on why they selected this lesson topic as being the most important by stating:

“It’s because most parents don’t really understand.

They’re just going with the flow, I guess.

They just get the diagnosis and they’re like,

‘Okay. So, I don’t really understand.

What am I supposed to do?

How am I supposed to handle this.

How am I supposed to bring it to my child’s family and friends? […]

But when they understand [autism] completely,

they’re able to help other people in the child’s life understand it better.”

Conversely, when asked what lesson they would find to be the least useful, eight participants stated that all the lessons would be useful, and three parents said that lesson 12 on “Challenging behavior is communication” would not be useful. One participant described how characterizing behavior as challenging would not necessarily help them in working with their child with autism. Rather, it would be more helpful to focus on understanding her son’s sensory sensitivity and activities or strategies that she can employ to help her son with this. Participants were also asked if any of the lessons should be combined. Most participants (n = 12, 80%) agreed that some of the lessons should be combined. Two participants agreed that lesson four on how to be an effective advocate and lesson five on advocacy in the school system should be combined. Additional topics that participants recommended the lessons cover included how to work with siblings of children with autism (n = 2, 13.3%), special diets for autism (n = 1, 6.7%), sign language (n = 1, 6.7%), and how to be with the child with autism in public (n = 2, 13.3%). Working with siblings was recommended as another topic to add, one participant explained this as follows:

“I have my older daughter. She's really bright, and I tell her, ‘My expectations for you are completely different than your brother, but I expect all of you to be able to take care of yourselves once you become adults. I expect you to have some type of living and some type of life.’ I said, ‘nobody is sitting in my house watching TV after they turn 18.’ So I think just maybe even some kind of support group, sometimes, I think, for siblings that have that way, maybe they’re taught what autism is, maybe more so towards them. I think that would be something to add.”

When asked if aspects of the Diné culture should be added to the program materials, most participants said that Diné examples (n = 10, 66.7%) and the Diné language (n = 11, 73.3%) should be included. Suggestions for Diné examples were to include Diné families making fry bread and gardening. A few parents pointed out that they were not fluent speakers of the Diné language, but that the Diné language should be part of this manual because there are grandparents, who most likely are fluent in the Diné language, which are raising children with autism. One participant elaborated on this by stating:

“…a lot of Native American grandparents are raising their grandchildren and I think that would be a really good option, not only because of that, but it would help them understand a little bit more, just because a lot of Navajos speak Navajo and it’s their first language. But for me, I’m 24. It’s my second language.”

Additionally, when asked about how much of the Diné language should be included in the manual one parent answered, “I would say about 10 percent to 15 percent.” Ultimately, the consensus was that all parents who answered this question shared that the Diné language should be included in some aspects of the program’s materials (i.e., program manuals, videos).

3.2 CAB input on PTA adaptations and adaptations made for Diné parents

Examples of adaptations made to the PTA program for Diné families based on input from the full CAB and/or input from the smaller workgroups are displayed by each dimension of the Ecological Validity Framework in Table 4. We expand on key input and decisions made by the full CAB regarding PTA adaptations, as well as on the input and decisions made by the smaller CAB workgroups about adaptations to the specific lessons that are part of the PTA program. The full CAB was provided with several opportunities to review and provide additional input on adaptations that were made based on input from the smaller CAB workgroups.

Table 4. Ecological validity framework dimensions and examples of adaptations made to the parents taking action program for Diné parents of children with autism.

3.2.1 Adaptations resulting from full CAB input

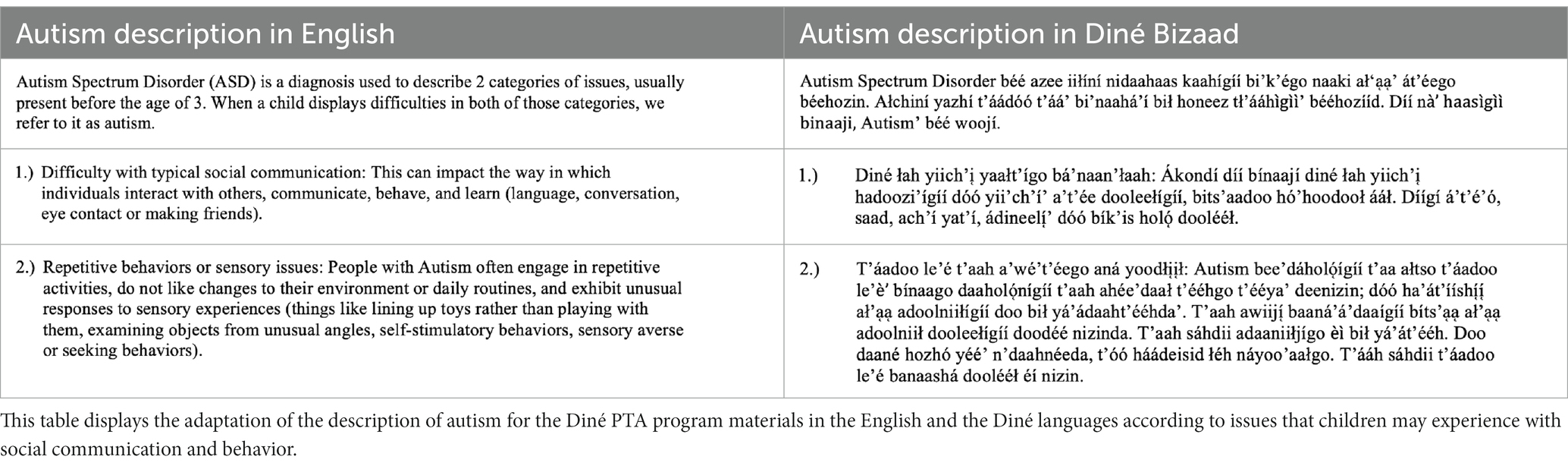

Key input and decisions made by the full CAB regarding adaptations for the PTA program materials were as follows: (1) to have an artist draw a culturally relevant picture to represent the Diné PTA project (Figure 3); (2) to use of the term family advisors for the community health workers delivering the program rather than promotoras or parent advisors in order to be more inclusive of caretakers that may not be the biological parents (e.g., grandparents, aunts, uncles, guardians) of children with autism; (3) to use Diné instead of Navajo to describe their people and language based on the tribe’s directive to maintain the use of their Native language; (4) to ensure that the amount of the manual translated into the Diné language (i.e., lesson titles and commonly recognized words) was based on how much of the Diné language families were likely to understand; and (5) to create new video recordings including a Diné narrator to supplement the written program manuals. A central reason CAB members stated for not including more Diné words is because the Diné language was traditionally an oral only language (McDonough, 2003). The lesson titles in the manual were translated by a Diné interpreter. The interpreter also translated some of the words used in narrative examples and the definition of autism. A primary care physician in an Indian Health Service clinic in the Navajo Nation initially provided a description of how they characterize autism in terms of its core symptoms to families. This description was then used by the interpreter and two CAB members fluent in Diné provided feedback on these translations. The interpreter incorporated this feedback as it was provided in revising the translations (Table 5).

Figure 3. Diné parents taking action project image by Emajoy Rains. This figure shows the shadow art of a Diné family walking together during the sunset, which was developed for this project by the Diné artist Emajoy Rains.

Table 5. Adaptation of the description of autism spectrum disorder for the Diné PTA program materials in the English and Diné Languages.

3.2.2 Adaptations resulting from the smaller CAB workgroups

Based on inputs from the CAB members, the fundamental elements of the program remained unchanged. Some adaptations were made to the story examples in the manual including the addition of Diné culture (i.e., significance of the baby’s first laugh, ceremonies and prayers, names of characters in stories, and pictures). For example, lesson one of the original PTA manual included a true story of Tom Iland and his life experiences as a person with autism. The workgroup assigned to this lesson agreed to adapt this story to one that was culturally relevant to Diné families. A fictional story about a young man with autism, Derek Yazzie, was created. The story started off explaining that Derek’s mother had a medicine man conduct a prayer for her and her baby. The prayer suggestion came from a few of the CAB members who shared that many of the Diné families they worked with in fact had prayers performed for themselves and their child(ren) with autism. Derek later received an automotive technology certificate at a tribal technical college and had a girlfriend named Megan Begay. The mention of a tribal technical college and the use of the common Diné surnames, Yazzie and Begay, bring aspects of the Navajo Nation into the story. The pictures in the manual were changed as much as possible to include Diné and/or Indigenous children/families which the CAB workgroups reviewed and approved. For example, some pictures that were purchased online for the manual included a girl in traditional regalia, a young man in front of a hogan (i.e., a traditional Diné home), and a father standing by his daughter who is on a horse with a red rock landscape behind them. Program images and visuals were reviewed by CAB members including one or more parent advisor (i.e., a Diné parent of a child with autism) to help ensure their cultural responsiveness. The adaptations also included information that the family advisors should note during their interactions with parents. For instance, in session one, the family advisor manual shares that some parents may see doing the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) or other assessments as comparing children to one another, which is something that Diné families may not feel comfortable doing. One CAB workgroup also brought up that Diné parents may not feel comfortable rewarding their child with autism for good behavior with extrinsic rewards, therefore, a question was added in session nine to find out how parents felt about rewarding their child and discovering things they would feel comfortable doing with their child for a reward.

4 Discussion

The purpose of this case study was to describe how the PTA program was adapted for Diné parents who have a child with autism using a community-engaged approach. The adaptation of the PTA program was accomplished by integrating the perspectives of Diné parents of a child with autism and the CAB members on cultural relevance and appropriateness of manual contents – such as pictures and videos – as well as preferences for PTA delivery. We used the Ecological Validity Framework dimensions to guide this process (Bernal et al., 1995). This study’s findings may aid health professionals and policy makers in their efforts to help support families that have a child with autism in Diné and other Indigenous communities. In applying similar types of community-engaged, culturally responsive models of family-oriented education and training, progress toward equitable health outcomes for children may be better sustained and spread.

4.1 Preferences for PTA delivery

In our study, comfort and familiarity between parents and family advisors (i.e., the community health workers) were important and needed. The interview participants expressed the preference that another Diné parent with a child with autism and someone who has experienced living on the Navajo reservation deliver the program. Racial concordance is referred to when a patient and clinician share the same race or ethnicity and it is argued to facilitate trust and comfort between the patient and clinicians – which in our study was between two parents (Cooper et al., 2006). The family advisors (i.e., the community health workers) currently delivering the Diné PTA program have created a bond and a higher level of comfort to share their experiences and struggles with pilot participants, which may be common because of similarities they have with each other not only in terms of racial backgrounds and lifestyles but also in terms of difficulties they may experience with accessibility to resources due to the rural nature of the areas that they live in. Based on additional information shared during the part of the interview about the participants lived experiences, the parents shared that social support in the form of support groups was an area of need for Diné parents who have children with autism (Lindly et al., 2023).

4.2 Preferences for PTA content

One of the most useful lessons reported by the parents interviewed was the lesson in which parents could learn about autism and what behaviors autism often entails. The Diné culture, similar to other Indigenous cultures, does not have a word for disability; therefore, the lack of understanding of many different disabilities or impairments is not surprising (Weaver, 2015). Until the last 15 years, several medical terms and books have been published but not always accessible to the families. The description of autism in the Diné language provided in the adapted PTA manual may help to guide an understanding of what autism is for native Diné speakers. Many families do not understand the behaviors and characteristics of autism due to a non-racial concordance; many times non-natives are doctors who diagnose their child with autism. And so, many Diné parents may feel overwhelmed with the new information that was shared with them. After diagnosis, many Diné parents may want or need to communicate in their own Diné language to better understand autism or would rather hear from another parent’s perspective about autism. Relatedly, one Diné parent interviewed for this project shared that labeling behavior as challenging was not beneficial, because the focus was on the negative connotation of the word, challenging. Nevertheless, after reviewing the full content of this lesson, CAB members agreed that it may be helpful to maintain “challenging” as a term used to describe certain behaviors that would be beneficial for the family and child to work on. Additional work may, therefore, be warranted to ensure that the PTA materials include as culturally responsive as possible language and potentially additional translation in written or audio format. Findings from the parent interviews in this study parallel findings from recent qualitative research conducted with inclusive early childhood educators providing services to autistic Māori children in that the educators interviewed expressed a need for more training and resources reflective of the Māori worldview and language (Tupou et al., 2023). Earlier and related work has further highlighted how effective interventions for autistic Māori children are connected to the Māori worldview and by gathering and integrating the perspectives of Māori families (Berryman and Woller, 2013).

4.3 Adaptations made to PTA for Diné parents

Taking into account racial concordance, materials were culturally and linguistically adapted to help parents connect with the contents. To adapt the materials responsively, we involved the Diné parents who participated in interviews and the CAB to gather and consider changes to the materials. Based on inputs from these two groups, two lessons on autism advocacy at the family and school levels were combined and changes were made to pictures, videos and stories in the manual to include names and narratives from the community and Diné culture. In addition, one question for parents and one consideration for family advisors to note was added to lessons to be respectful to parents’ cultural views on rewarding children and comparison of their child with other same-aged children, respectively. To maintain fidelity to the original PTA program and given input from interview participants and CAB members, major content was not added or deleted in the adapted materials. In some cases, certain topics suggested by parents as being helpful to add to the PTA materials were already included in the full manuals that interview participants did not review (i.e., they reviewed the lesson titles), such as some information on interactions including play with siblings. We also added some resources such as the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health’s Autism web page URL in the manual to provide additional information about the evidence base for special diets and other complementary health approaches for autism that parents may be interested in. In the future, we will endeavor to add more information on topics of interest suggested by parents who participate in our pilot of the initial adaptation of PTA for Diné families. For certain topics that participants recommended more information be added on, such as special diets, we will ensure that the information provided is based on the current evidence available related to the effects of special diets for children with autism.

4.4 Limitations and future directions

Our study is one of a kind research insofar as it involved Diné parents of children with autism. That is, there was little previous work to draw from in this study. Still, we sought our resources from other community-engaged PTA processes – via the PTA research collaborative to help guide this program’s adaptation. Parents who have a child with autism were included in the adaptation process by providing input during the interviews and participation in the advisory group; however, the parents were not questioned to find out if they themselves have autism. In addition, the CAB members were also not questioned about whether they have autism. Because of this, it is unknown if any of the parent interview participants or CAB member had autism. It is known that two members of the CAB identify as being neurodivergent. We recognize that the participation of one or more autistic adult(s), particularly those also identifying as Diné, in the adaptation process would have provided additional, useful perspective and may have strengthened the emphasis on autism acceptance in this study. It is, therefore, recommended that future efforts related to this initial work and other cultural adaptations of parent education and training programs focused on children with autism include the voices of neurodivergent and specifically autistic individuals.

Along these lines, it may be helpful to recognize that the PTA program has many elements that are acceptance oriented such as in the following lessons: 1 - Introduction and Understanding Child Development; 2 – Understanding the Autism Spectrum and Your Child’s Needs; 3 – Play Together, Learn Together; 4 – Creating Everyday Opportunities to Encourage Communication; and 12 – Building Social Support and Looking Ahead. These lessons specifically focus on autism acceptance by parents and community members more broadly (e.g., providing parents with acceptance oriented information and ways to respond to community members about their child’s autism). We also acknowledge that a limitation of this study was that its main purpose was to culturally adapt PTA for Diné families and hence autism acceptance – though important -- was not the central focus in terms of adaptation. Future projects using PTA and other parent education and training programs should consider making all the lessons more autism acceptance oriented. For example, rethinking the titles of Lesson 5 – Challenging Behavior is Communication and Lesson 6 – Responding Appropriately to Challenging Behaviors in terms of not qualifying behavior as being challenging (e.g., Behavior is Communication) and more explicitly recognizing that parents may not favorably view commonly used behavior oriented interventions (e.g., Applied Behavioral Analysis) for children with autism in terms of the intervention’s helpfulness for them and their child, as was shown by Tschida et al. (2021). It may additionally be beneficial to include a lesson more explicitly dedicated to autism acceptance and neurodiversity more broadly including the range of health-related and other experiences that autistic individuals may experience across the lifespan, while maintaining relevant cultural preferences and values expressed by families.

Due to our study’s timeline, our recruitment was affected by COVID-19; however, we were still able to recruit the largest sample of Diné parents of a child with autism for which published research exists. Recruitment may have also been affected by Diné parents not being exposed to recruitment information due to many living in the Navajo Nation the Navajo reservation with limited to no internet access. Despite these issues we were still able to recruit participants for our study, but the input provided by the interview participants was likely not representative of all Diné parents of a child with autism in and around the Navajo Nation. In adapting any evidence-based program for a unique ethnic group using a community engaged process, there are tensions in how to reconcile conflicting perspectives and how to best maintain the original program’s fidelity. We relied heavily on our CAB, various entities on and around the Navajo Nation, and the voices of Diné parents to help inform this adaptation process. We also attempted to use our CAB to help reconcile contrary feedback in adapting the program.

Because this was a qualitative study, the interview participant sample size was small and was not intended to be generalizable, though the sample size in this study was larger than samples in similar prior, related studies (Connors, 1992; Kapp, 2011; Najera, 2012). Rather, the intention of this study was to share information on the adaptation process of the PTA program for Diné families of children with autism to help inform future adaptations of this program and related service delivery and programming for this population. Indeed, research by Sullivan (2013) suggests that thematic saturation, meaning the inability to identify new themes, is often possible with data from six to 12 interviews. Subsequent phases of this work may consider engaging a larger number of individuals to the extent that is possible.

4.5 Conclusion

This study provides new knowledge on how an evidence-based parent education and training program was adapted to be culturally responsive for Diné parents who have a child with autism. We used primary data collected through interviews with Diné parents who have a child with autism, as well as input gathered from a CAB and smaller CAB workgroups to make program adaptations. We are presently piloting the adapted Diné PTA program. Information gathered will be used to inform Diné PTA program adaptations in the future.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because in accordance with Tribal Sovereignty, any data connected with this study that are identifiable data from tribal members can only be shared with appropriate tribal policies and permissions. Should other researchers wish to use these data at a future time for reanalysis or to explore additional hypotheses, they would need to request access to the data through application to the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board, and their proposal would need to meet the guidelines for research in accordance with tribal policy. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bXJ3aW5uZXlAbmF2YWpvLW5zbi5nb3Y=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Northern Arizona University Institutional Review Board and the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because this research was minimal risk and verbal consent reduced the risk of breech of confidentiality.

Author contributions

OL, DH, and KL conceptualized this study. CR recruited, consented and obtained data from all interview participants. CR, DH, and OL obtained feedback from the advisory board members on the PTA materials. CR and OL analyzed the interview data and adapted the PTA materials based on interview results and input from the community advisory board members. DH and CV provided assistance with the translation and cultural adaptation of PTA materials. KL provided the critical guidance on the PTA program’s adaptation process. SB provided input on the adaptation of PTA materials and managed this study’s references. EH and AL contributed to the PTA program adaptation. SN provided assistance with data analysis and results interpretation. All other authors contributed to drafting and to critically revising the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from the Southwest Health Equity Research Collaborative at Northern Arizona University (U54MD012388), which is sponsored by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). This research was also funded by the Organization for Autism Research through an Applied Research Competition Grant.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the guidance and support of our larger project’s Community Advisory Board that is composed of the following individuals Vernyllia Begay, Tudy Billy, Sara Clancey, Joe Donaldson, Holly Figueroa, Rachel Homer, Kelly Lalan, Brian Van Meerten, Maureen Russell, and Summer Weeks. We would also like to acknowledge our project’s interpreter, Julius Tulley. Lastly, we acknowledge the body of work and cultural adaptation guidance on the Parents Taking Action program provided by Sandra Magaña, Sarah Dababnah, Yue Xu, and others.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, (5th Edn.). Washington, DC: APA

Aylward, B., Gal-Szabo, D. E., and Taraman, S. (2021). Racial, ethnic, and sociodemographic disparities in diagnosis of children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 42, 682–689. doi: 10.1097/dbp.0000000000000996

Banks, S., and Miller, D. (2005). Empowering indigenous families who have children with disabilities: an innovative outreach model. Disab. Studies Quart. 25. doi: 10.18061/dsq.v25i2.544

Beighton, C., and Wills, J. (2017). Are parents identifying positive aspects to parenting their child with an intellectual disability or are they just coping? A qualitative exploration. J. Intellect. Disabil. 21, 325–345. doi: 10.1177/1744629516656073

Bennett, A., Ray, M., Zucker, E., and Chuo, J. (2021). Increasing diagnostic Services for Autism Spectrum Disorder in the native American community: a pilot collaborative telecare model. Pediatrics 147, 970–971. doi: 10.1542/peds.147.3MA10.970

Bernal, G., Bonilla, J., and Bellido, C. (1995). Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 23, 67–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01447045

Berryman, M., and Woller, P. (2013). Learning about inclusion by listening to Māori. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 17, 827–838. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2011.602533

Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L., and Kind, A. J. H. (2017). A scoping review of health disparities in autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 47, 3380–3391. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3251-9

Botha, M., and Gillespie-Lynch, K. (2022). Come as you are: examining autistic identity development and the neurodiversity movement through an intersectional lens. Hum. Dev. 66, 93–112. doi: 10.1159/000524123

Combrink, T. (n.d.). Demographic analysis of the Navajo nation 2011–2015 American community survey estimates. Arizona Rural Policy Institute, Northern Arizona University. Available at: https://in.nau.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/212/Navajo-Nation-2011-2015-Demographic-Profile-.pdf

Connors, J. L. Perceptions of autism and social competence: a cultural perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA, (1992).

Cooper, L. A., Beach, M. C., Johnson, R. L., and Inui, T. S. (2006). Delving below the surface. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 21, S21–S27. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00305.x

Cupertino, A. P., Suarez, N., Cox, L. S., Fernández, C., Jaramillo, M. L., Morgan, A., et al. (2013). Empowering Promotores de Salud to engage in community-based participatory research. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 11, 24–43. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2013.759034

Dababnah, S., Kim, I., Magaña, S., and Zhu, Y. (2022). Parents taking action adapted to parents of black autistic children: pilot results. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disab. doi: 10.1111/jppi.12423

Dababnah, S., Shaia, W. E., Kim, I., and Magaña, S. (2021). Parents Taking Action: Adapting a Peer-to-Peer Program for Parents Raising Black Children With Autism. Inclusion 9, 205–224. doi: 10.1352/2326-6988-9.3.205

DePape, A.-M., and Lindsay, S. (2015). Parents’ experiences of caring for a child with autism Spectrum disorder. Qual. Health Res. 25, 569–583. doi: 10.1177/1049732314552455

Frankland, C. H., Turnbull, A. P., Wehmeyer, M. L., and Blackmountain, L. (2004). An exploration of the self-determination construct and disability as it relates to the Diné (Navajo) culture. Educ. Train. Dev. Disabil. 39, 191–205.

Guan, J., and Li, G. (2017). Injury mortality in individuals with autism. Am. J. Public Health 107, 791–793. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303696

Harvey, A. C., Harvey, M. T., Kenkel, M. B., and Russo, D. C. (2010). Funding of applied behavior analysis services: current status and growing opportunities. Psychol. Serv. 7, 202–212. doi: 10.1037/a0020445

Hsieh, H.-F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Hunter, C. M., Lewis, J., Peter, D., Begay, M.-G., and Ragin-Wilson, A. (2015). The Navajo birth cohort study. J. Environ. Health 78, 42–45.

Kahn-John, M. (2016). The path to development of the Hózhó Resilience Model for nursing research and practice. Appl. Nurs. Res. 29, 144–147. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.02.010

Kapp, S. K. (2011). Navajo and autism: the beauty of harmony. Disability Soc. 26, 583–595. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2011.589192

Kayfitz, A., Gragg, M., and Orr, R. (2010). Positive experiences of mothers and fathers of children with autism. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 23, 337–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00539.x

Kearney, P., and Griffin, T. (2001). Between joy and sorrow: being a parent of a child with developmental disability. J. Adv. Nurs. 34, 582–592. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01787.x

Kuhlthau, K., Orlich, F., Hall, T. A., Sikora, D., Kovacs, E. A., Delahaye, J., et al. (2010). Health-Related Quality of Life in children with autism spectrum disorders: results from the autism treatment network. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 40, 721–729. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0921-2

Lavelle, T. A., Weinstein, M. C., Newhouse, J. P., Munir, K., Kuhlthau, K. A., and Prosser, L. A. (2014). Economic burden of childhood autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 133, e520–e529. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0763

Lee, J. D., Meadan, H., Sands, M. M., Terol, A. K., Martin, M. R., and Yoon, C. D. (2023). The cultural adaptation checklist (CAC): quality indicators for cultural adaptation of intervention and practice. Int. J. Dev. Disab., 1–12. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2023.2176966

Lindly, O. J., Henderson, D. E., Vining, C. B., Running Bear, C. L., Nozadi, S. S., and Bia, S. (2023). “Know your children, who they are, their weakness, and their strongest point”: a qualitative study on Diné parent experiences accessing autism Services for Their Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20085523

Lindly, O. J., Shui, A. M., Stotts, N. M., and Kuhlthau, K. A. (2022). Caregiver strain among north American parents of children from the autism treatment network registry call-Back study. Autism 26, 1460–1476. doi: 10.1177/13623613211052108

Lindly, O., Chavez, A. E., and Zuckerman, K. E. (2016). Unmet health services needs among US children with developmental disabilities: associations with family impact and child functioning. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 37, 712–723. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000363

Lopez, K., Magaña, S., Morales, M., and Iland, E. (2019). Parents taking action: reducing disparities through a culturally informed intervention for Latinx parents of children with autism. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work 28, 31–49. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2019.1570890

Maenner, M. J., Warren, Z., Williams, A. R., Amoakohene, E., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., et al. (2023). Prevalence and characteristics of autism Spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years-autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. Morbid. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 72, 1–14. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7202a1

Magaña, S., Hughes, M. T., Salkas, K., and Angarita, M. M. (2019). Adapting an education program for parents of children with autism from the United States to Columbia. Disab. Glob. South 6, 1603–1621.

Magaña, S., Lopez, K., and Machalicek, W. (2017). Parents taking action: a psychoeducational intervention for Latino parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Fam. Process 56, 59–74. doi: 10.1111/famp.12169

Magaña, S., Lopez, K., Salkas, K., Iland, E., Morales, M. A., Torres, M. G., et al. (2020). A randomized waitlist-control group study of a culturally tailored parent education intervention for Latino parents of children with ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 250–262. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04252-1

Magaña, S., Lopez, K., Paradiso de Sayu, R., and Miranda, E. (2014). Use of promotoras de salud in interventions with Latino families of children with IDD. International review of. Res. Dev. Disabil. 47, 39–75. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800278-0.00002-6

McDonough, J. M. (2003). The Navajo sound system. Springer Sci. Busi. Med. doi: 10.1007/978-94-010-0207-3

Najera, B.N. (2012). ABA in native American homes: a culturally responsive training for paraprofessionals, Pepperdine university: Malibu, CA, USA.

Navajo Nation Department of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services. (n.d.). Growing in beauty. Available at: (Accessed December 30, 2022) http://www.nnosers.org/growing-in-beauty.aspx.

Navajo Nation Land Department [Cartographer] (n.d.) 5 Navajo Nation Tribal Agency Councils [Map]. Available at: https://navajofamilies.org/navajo.html (Accessed October 27, 2022).

O'Neal, M.A., Agosta, J., and Toubbeh, J. A., (1987). Path to peace of mind: providing exemplary services to Navajo children with developmental disabilities and their families. Save the children federation, Navajo nation field office (window rock, Az., 1987). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1132&context=nhd

Puska, S., Walsh, C., Markham, F., Barney, J., and Yap, M. (2022). Community-based social care models for indigenous people with disability: a scoping review of scholarly and policy literature. Health Soc. Care Community 30, e3716–e3732. doi: 10.1111/hsc.14040

QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

Queirós, F. C., Wehby, G. L., and Halpern, C. T. (2015). Developmental disabilities and socioeconomic outcomes in young adulthood. Public Health Rep. 130, 213–221. doi: 10.1177/003335491513000308

Raising Special Kids (2021). Annual Report 2020–2021. Raising Special Kids. Available at: https://b5wab7.p3cdn1.secureserver.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/2020-2021-Annual-Report-Portrait-FINAL-for-web-1.pdf

Rennie, B. J., Bishop, S. L., Leventhal, B. L., Zheng, S., Geib, E., Kim, Y. S., et al., (2023). Neurodevelopmental profiles of 4-year-olds in the Navajo birth cohort study.

Saldaña, J. M. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd Edn.). Thousand Oaks, CA. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Sarche, M. C., Spicer, P., Farrell, P., and Fitzgerald, H. E. (2011) American Indian and Alaska native children and mental health: development, context, prevention, and treatment. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Schieve, L. A., Boulet, S. L., Kogan, M. D., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., Boyle, C. A., Visser, S. N., et al. (2011). Parenting aggravation and autism spectrum disorders: 2007 National Survey of Children’s health. Disabil. Health J. 4, 143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2010.09.002

Sullivan, A. (2013). School-based autism identification: prevalence, racial disparities, and systemic correlates. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 42, 298–316. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2013.12087475

Taunt, H., and Hastings, R. P. (2002). Positive impact of children with developmental disabilities on their families: a preliminary study. Educ. Train. Mental Retard. Dev. Disab. 37, 410–420.

Travers, J., and Krezmien, M. (2018). Racial disparities in autism identification in the United States during 2014. Except. Child. 84, 403–419. doi: 10.1177/0014402918771337

Tschida, J. E., Maddox, B. B., Bertollo, J. R., Kuschner, E. S., Miller, J. S., Ollendick, T. H., et al. (2021). Caregiver perspectives on interventions for behavior challenges in autistic children. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 81:101714. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101714

Tupou, J., Ataera, C., Wallace-Watkin, C., and Waddington, H. (2023). Supporting tamariki takiwātanga Māori (autistic Māori children): exploring the experience of early childhood educators. Autism 13623613231181622. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/13623613231181622

Van Sickle, D., Morgan, F., and Wright, A. L. (2003). Qualitative study of the use of traditional healing by asthmatic Navajo families. American Indian Alaska Native Mental Health Res. 11, 1–18. doi: 10.5820/aian.1101.2003.1

Vining, C. B. (2000). Disability in Navajo society. University of New Mexico, Center for Development & Disability. Available at: http://cdd.unm.edu/cspd/index.html

Weaver, H. N. (2015). Disability through a native American lens: examining influences of culture and colonization. J. Soci. Work Disab. Rehab. 14, 148–162. doi: 10.1080/1536710X.2015.1068256

Wei, X., Blackorby, J., and Schiller, E. (2011). Growth in reading achievement of students with disabilities, ages 7 to 17. Except. Child. 78, 89–106. doi: 10.1177/001440291107800106

Xu, Y., Chen, F., Mirza, M., and Magaña, S. (2023). Culturally adapting a parent psychoeducational intervention for Chinese immigrant families of young children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 20, 58–72. doi: 10.1111/jppi.12432

Zeng, W., Magaña, S., Lopez, K., Xu, Y., and Marroquín, J. M. (2022). Revisiting an RCT study of a parent education program for Latinx parents in the United States: are treatment effects maintained over time? Autism 26, 499–512. doi: 10.1177/13623613211033108

Keywords: autism, case study, children, community health worker, Diné, parent education and training, Navajo, Parents Taking Action

Citation: Lindly OJ, Running Bear CL, Henderson DE, Lopez K, Nozadi SS, Vining C, Bia S, Hill E and Leaf A (2023) Adaptation of the Parents Taking Action program for Diné (Navajo) parents of children with autism. Front. Educ. 8:1197197. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1197197

Edited by:

Emily Hotez, UCLA Health System, United StatesReviewed by:

Katherine Ardeleanu, Drexel University, United StatesTaylor Thomas, University of California, Los Angeles, United States

Heather M. Brown, University of Alberta, Canada

Copyright © 2023 Lindly, Running Bear, Henderson, Lopez, Nozadi, Vining, Bia, Hill and Leaf. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olivia J. Lindly, T2xpdmlhLkxpbmRseUBuYXUuZWR1

Olivia J. Lindly

Olivia J. Lindly Candi L. Running Bear2

Candi L. Running Bear2 Sara S. Nozadi

Sara S. Nozadi Erin Hill

Erin Hill Anna Leaf

Anna Leaf