- Department of English Language and Literature, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran

The question of whether podcasting affects the processes of teaching and learning English language has been extensively studied in recent years. However, there are a limited number of studies on whether video podcasts can affect learning English proverbs. The current study investigated the effectiveness of video podcasts in terms of learning English proverbs in a non-native environment. The participants of this study were 31 undergraduate students majoring in English Language and Literature at Yazd University who had enrolled in a course entitled “Listening and Speaking.” They were randomly divided into two groups namely control group and experimental group. A pre-test was given to both groups before the intervention sessions. The control group was taught based on the traditional approach, and the experimental group was taught based on video podcasting. Following 5 weeks of the intervention, all the students in the two groups were given a post-test. The results of the post-test revealed that the students in the experimental group performed much better in comparison to the students in the control group. Preliminary results of this study can increase nonnative English language teachers’ awareness of using technology in their classes with respect to teaching English proverbs. Also, immigrants who intend to learn English language and culture can benefit from the findings of this research.

1. Introduction

A podcast is a digital video or audio file made available on the internet for streaming, typically in a series format. It can be accessed through various platforms such as ITunes, Spotify, and SoundCloud. The term podcast is a combination of iPod (a popular portable media player) and broadcast (Oxford Languages, 2021). Video podcasts have also been referred to as audio graphs (Loomes et al., 2002), podcasts (Heilesen, 2010), vodcasts (Vajoczki et al., 2010), webcasts (Shim et al., 2007), and video streams (Bennett and Glover, 2008).

Investigation on the use of video podcasts in education began to surface in 2002 with references to audio graphs (Loomes et al., 2002), video streaming (Foertsch et al., 2002; Green et al., 2003; Shephard, 2003) and webcasting (Reynolds and Mason, 2002). High speed bandwidth was relatively unusual between 2000 and 2005 (Smith, 2010), so the use of video podcasts in education was limited by download time duration and research in this area was limited. It has been emphasized that two key factors changed the direction and frequency of video podcast use for entertainment, and subsequently education.

First of all, in February of 2005, YouTube, a site designed to spread a wide range of video clips, was launched (You Tube, 2011). By 2006, YouTube was watched by 100 million viewers per day (Infographics, 2010). As of May 2011, YouTube was viewed over 3 billion times per day (Henry, 2011). Originally used for entertainment purposes, YouTube is a free source of numerous educational videos in a wide range of subject areas. The second factor that helped change the landscape of video podcast use in education was increase of bandwidth. Between 2007 and 2010, the adoption of high-speed Internet access increased rapidly in homes and schools (Smith, 2010) along with research studies concerning the use of video podcasts in education. Prior to 2006, eight peer-reviewed articles had been written regarding the use of video podcasts in education. As it has been echoed in the literature 52 new articles have been published since 2006. Nevertheless, few studies have been conducted to examine the benefits and challenges of using video podcasts in Iranian academic context.

The use of video podcasts in higher education, especially in language learning has been shown to have several benefits and challenges. Video podcasts can improve listening comprehension. Chen and Chung (2008) found that personalized English news broadcasts improved novice listeners’ comprehension skills by providing them with authentic listening materials tailored to their interests and needs. According to Kukulska-Hulme and Shield (2008) podcasts can provide learners with exposure to new vocabulary in a context which can lead to better retention and acquisition of new words. Finally, video podcasts can increase motivation. Lee and Chan (2007) reported that university students who used online podcasts for language learning were more motivated than those who did not use them due to their convenience and flexibility.

On the other hand, one of the main challenges identified by previous research studies is related to technical issues. For example, Kessler and Bikowski (2010) found that students encountered difficulties with downloading and accessing podcasts due to limited internet connection or lack of access to appropriate devices. Similarly, Chen Y. et al. (2014) reported that students confronted problems while listening to audio texts. Another challenge is related to pedagogical issues. For instance, Kim (2017) cautioned that teachers must be careful in selecting appropriate podcast materials that align with their learning objectives and students’ needs. Moreover, teachers must provide instruction concerning the benefits of utilizing podcasts for learning the target language accurately and fluently.

Furthermore, some studies have highlighted the challenge of motivation and engagement when using podcasts in ELT. For example, Lee and Chan (2019) found that students’ motivation level varied depending on their interest in the topic of the podcast or proficiency level. Similarly, Wang and Chen (2020) reported that some students felt overwhelmed by the amount of listening required when using podcasts for learning of target language.

In recent years, video podcasting has become an increasingly popular technique for language learning. With advancement in technology, learners now have access to many resources that can help them improve their language skills. In English Language Teaching (ELT), video podcasting has been recognized as an effective technique for enhancing the learning of target language. Several research studies have been conducted to explore the potential benefits of video podcasting in ELT. For instance, a study by Chen C. et al. (2014) investigated the impact of video podcasts on students’ listening comprehension skills. The results showed that students who received video podcasts performed significantly better than those who did not. Correspondingly, Liang and Li (2016) investigated the use of video podcasts in promoting learners’ speaking skills. The findings revealed that learners who received video podcasts were more confident and fluent in their speaking than those students who were deprived of this technique.

Proverbs are wisdom sayings in all cultures. Proverbs have been used as a pedagogical tool in modern societies to teach moral values and social skills. Proverbs are described as “a pithy and popular expression that presents an idea of experience, knowledge, advice, morality, truth, virtue, genius, irony, etc.” (Gorjian, 2006, p. 1). Mieder (2006) has noted that a proverb is a traditional saying that “sums up a situation, passes judgment on a past matter, or recommends a course of action for the future” (p. 11). In today’s media, proverbs repeatedly occur on radio, TV, magazines, advertisements, commercials, and the Internet (Nippold et al., 2000).

According to Güven and Halat (2015), transferring these cultural elements is crucial in teaching the target language. In other words, as proverbs are part of any culture, learning any foreign language cannot be considered apart from its culture. To date, many L2 scholars and researchers have investigated the role of proverbs in teaching different subjects in different languages. Proverbs play an essential part in learning and teaching the target language. They are windows through which learners increase their knowledge about different cultures to comprehend and use them (Akpinar, 2010; Güven and Halat, 2015; Alavinia, 2016). Litovkina (1998) suggests using proverbs in various areas of language teaching such as grammar and syntax, phonetics, vocabulary, culture, as well as developing language skills namely reading, speaking, listening and writing. Correspondingly, Litovkina (2000) asserts that proverbs, besides being an eminent part of a culture, are essential for communicating effectively and efficiently.

The effect of using technological devices such as mobile phones and podcasts while learning the target language learning of EFL learners has been investigated by several researchers in different contexts during the last decade (Crippen and Earl, 2004; Copley, 2007; McCombs and Liu, 2007; Dupagne et al., 2009; Griffin et al., 2009; Jarvis and Dickie, 2009; Leijen et al., 2009; Traphagan et al., 2010; Hill and Nelson, 2011). However, to date, few research studies have been conducted to examine the effectiveness of video podcasts in terms of learning English proverbs of EFL learners. The current study attempted to examine the extent to which the use of technological devices such as mobile phone and video podcast can improve learning of English proverbs. Therefore, this study addresses the following research questions:

1. Is there any significant difference between the traditional approach of teaching English proverbs and using video podcasts in the classroom?

2. What are the attitudes and beliefs of the students in the experimental group in terms of learning English proverbs through video podcasting?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

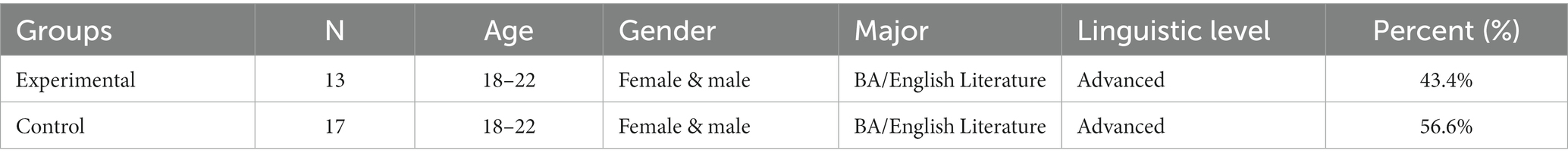

The participants in the current study were 31 undergraduate students majoring in English Language and Literature at Yazd University. These students were in the first semester and had enrolled in the course entitled “Listening and Speaking” in the fall semester of the academic year 2022. Oxford Proficiency Test was used to assess the proficiency level of 31 students who were willing to participate in this research study. The test results revealed that all the students were at the advanced level. The justification behind selecting the students of this level is that they would not encounter serious language barriers to engage in classroom activities. Accordingly, applying the standardized test of proficiency and selecting the participants of high proficiency would limit the effects of membership of the group. Next, the participants were randomly assigned to two groups by researchers, namely an experimental and a control group. The control group including 17 male and female students was taught based on the traditional approach of teaching proverbs whereas the experimental group including 14 male and female students was taught based on video podcasting technique.

As it is necessary for all the participants to be an active participant and be present during all the data collection sessions, one of the participants was excluded from the experimental group of this study. He did not attend the classes regularly and was absent on the post-test. Therefore, the total number of participants whose performances were taken into consideration was 30 (Table 1).

2.2. Materials

The following materials were utilized in this research: (1) a Microsoft word File (©Microsoft 2023) which was prepared by the researchers before each class session in conjunction with the transcript version of the proverbs, (2) a ready-made video podcasts, which was downloaded by the researchers from one YouTube channel (©2022 Accurate English LLC), and each of which contains eight to nine proverbs, (3) mobile phone as a device to join the Telegram group (Telegram FZ LLC Telegram Messenger Inc.) which was created by the researchers. The researchers used the Microsoft word files to teach the participants in the control group the proverbs’ meaning, structure, and historical background of the proverbs. Students in the control group should attend the class regularly, and learned the proverbs based on the traditional approach (teacher-centered approach). In contrast, students in the experimental group joined the Telegram group which was created by the researchers, where they were provided with 12-min video podcasts, each containing eight to nine proverbs. Students in the experimental group downloaded, and watched those podcasts. The content of the podcasts sent to the participants of the experimental group was the same as the content the students in control received. The participants in the experimental group also used mobile phones to share their homework and highlight their attitudes and opinions about proverbs. Figure 1 displays one sample of Microsoft word document which was used for teaching the participants in the control group. In addition, Figure 2 illustrates one sample of video podcast which was used for teaching the participants in the experimental group.

Figure 1. Sample of Microsoft Word document (©Microsoft 2023) which was used for teaching the participants in the control group.

Figure 2. Sample of teaching materials which was used for teaching the participants in the experimental group.

2.3. Instruments

The following instruments were utilized in this study: an Oxford Proficiency Test, a post-test, a pre-test, and a questionnaire. At the beginning of the semester, all the participants in both groups were given the Oxford Proficiency Test to estimate the proficiency level and ensure the homogeneity of the two groups. The results of the test revealed that all the students were at an advanced level and were homogeneous. Furthermore, the researchers designed a pre-test and post-test of proverbs. Each test included 40 questions, including 20 multiple-choice items and 20 matching items. A pre-test was administered to examine the participants’ knowledge of proverbs before the intervention sessions.

After 5 weeks of the intervention sessions, all the students in the two groups were given a post-test to examine which approach for teaching proverbs proved more successful and the extent to which there was a difference between utilizing the traditional approach for the participants in the control group and using video podcasts for the participants in the experimental group for teaching English proverbs. The items included in the post-test were different from the pre-test but at the same level of difficulty. Finally, after 5 weeks of the intervention sessions, researchers administered a questionnaire designed by Al Qasim and Al Fadda (2013) only to the participants of the experimental group to explore their attitudes and beliefs regarding the use of podcasts to learn English proverbs. This questionnaire consisted of 26 Likert-scale items.

2.4. Data collection and analysis

The required data for this study for each group is elaborated in this section. During the semester, the participants in the control group received instruction regarding the meaning, and historical background of proverbs based on the traditional method of teaching proverbs that is, in the class. In fact, the second author was the teacher for the participants in the control group and the experimental group. The teacher used the word files which were prepared in advance and included the transcript version of the proverbs to teach English proverbs. During the teaching process, the participants in the control group expressed their attitudes about the proverbs which were taught in the class. As homework students must write four sentences for each proverb which was taught on each session. In addition, participants must express their opinions about the proverbs in a few sentences and compare and contrast these English proverbs and those that exist in their first language (Persian). The students should write their homework by the means of pen and paper. It was also obligatory for all the students to submit their homework on the following session and received feedback by the teacher. The researcher (the first author) also attended all the intervention sessions in conjunction with the students. The teacher and the researcher read the written tasks of the students and provided feedback and comments about the content, structure, and organization of the tasks written by the participants of the control group.

On the other hand, the students in the experimental group joined the Telegram group created by the researchers, where they were provided with video podcasts for duration of 12 min. The participants in the experimental group within 4 days should download and watch video podcasts and perform their homework, via their mobile phones, and shared them with their classmates in the Telegram group again. This proved fruitful for the participants of the experimental group because they could watch relevant video podcasts and have interaction with the teacher and their classmates in the form of voice messages, texting, and icon use. The assignments of the experimental group were similar to those of the participants in the control group. The researchers to give their comments about the assignments of the students in the experimental group used Microsoft Word Office. Next, the students’ assignments along with the feedback were returned to the students in the Telegram group. The students could download their own files which was related to them and read the comments about their assignments. At the end of the data collection process, a questionnaire was administered to the participants in the experimental group to explore their beliefs and attitudes with respect to using video podcasts as a technique to learn English proverbs.

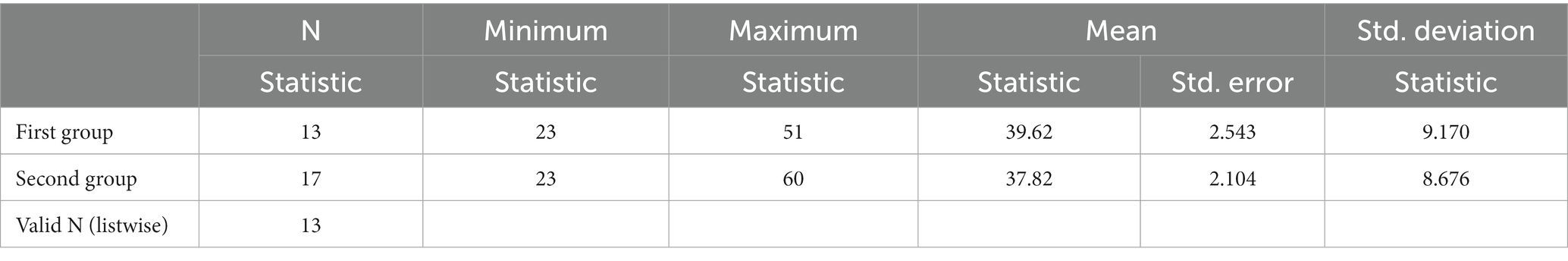

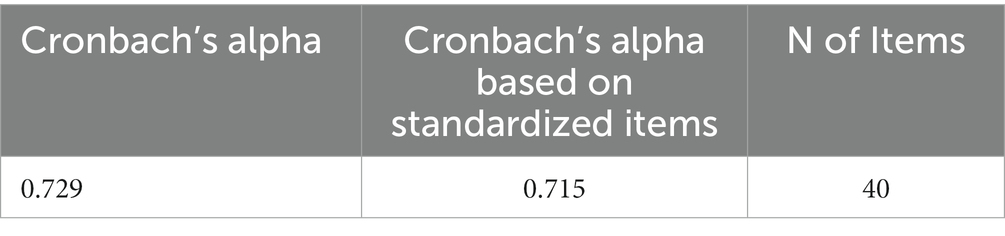

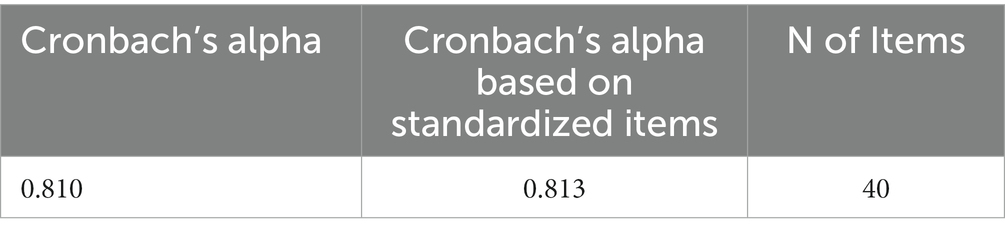

Before conducting a pre-test and post-test the researchers examined the reliability and validity content of the pre-test and the post-test. First of all, to examine the reliability of the items of these two tests, researchers conducted a pilot study on 12 participants who were at the same proficiency level in comparison to the target sample of this study. The results obtained from this pilot study were computed by using Cronbach’s Alpha formula and SPSS software package. Second, to examine the content validity of both the pre-test and the post-test of the current study, researchers requested three associate professors (expert judges) in Applied linguistics to check the items of the tests and report their comments in order to enhance the validity of the tests. The researchers used their comments to revise the items included in the pre-test and post-test.

The obtained data from these two groups of participants were analyzed by using independent sample t-test to examine whether there was a significant difference between these two approaches of teaching English proverbs.

3. Results

3.1. Oxford Proficiency Test

Oxford Proficiency Test was administered to all participants of the current study to estimate the proficiency level and ensure the homogeneity of the two groups. The results of this test are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2 reveals the mean and the standard deviation of the participants who were in Listening & Speaking course, group one (M = 39.62, SD = 9.17). Table 2 also shows the mean and standard deviation of the participants who were in Listening & Speaking course, group two (M = 37.82, SD = 8.67). It can be concluded that they were homogeneous at the beginning of the semester, that is, prior to the intervention sessions. Then, they were randomly divided into two groups namely experimental, and control groups.

3.2. The reliability of the pre-test

To provide valid results and reliable conclusions, a test of the reliability of the pre-test was conducted which is illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3 illustrates the Cronbach’s Alpha is more than 0.70 (0.72), which indicates that the items of the pre-test of proverbs were reliable.

3.3. The reliability of post-test

In addition, a test of the reliability of the post-test items was performed which is displayed in Table 4.

Table 4 illustrates, the Cronbach’s Alpha is more than 0.70 (0.81), which shows that all the items of the post-test of proverbs were reliable.

3.4. Independent sample t-test for the pre-test

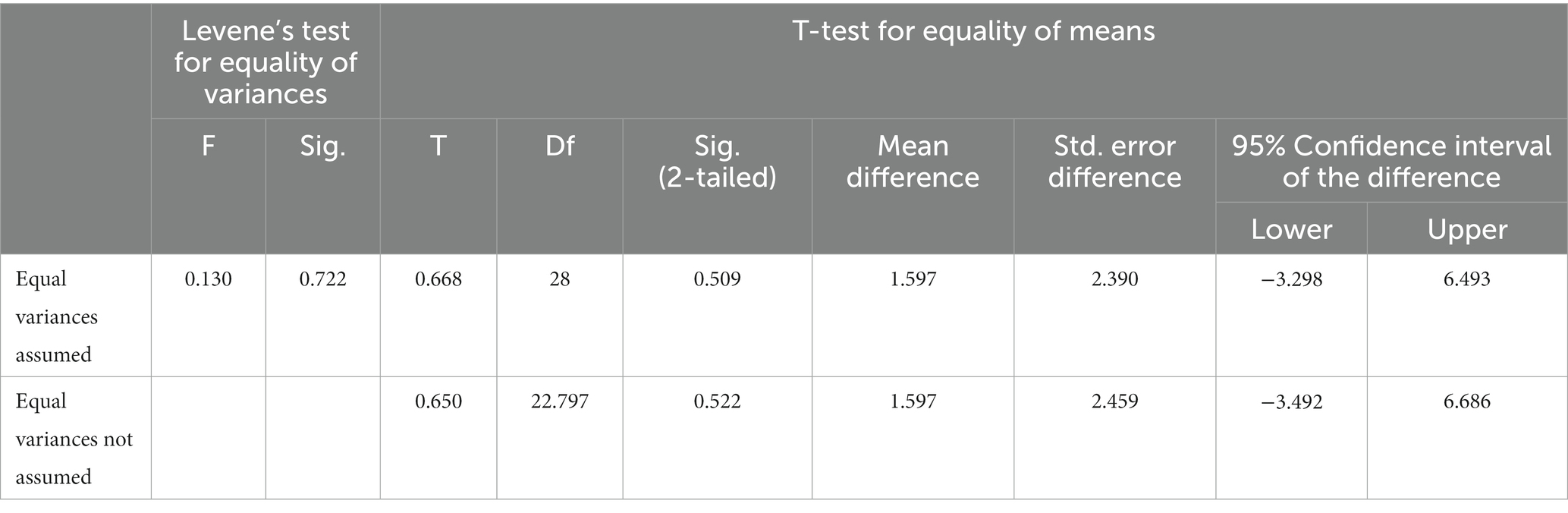

Table 5 displays an independent sample t-test results for the pre-test. The independent sample t-test revealed that the participants in both experimental and control groups were at the same level of proficiency regarding the knowledge of English proverbs at the beginning of the semester.

The results of the independent-sample t-test as displayed in Table 5 indicates that the level of significance was more than 0.05 [t (28) = 0.66, p = 0.51 (two-tailed; p > 0.05)], and the participants of both the groups were homogeneous at the outset of the study. Furthermore, the 95% confidence interval around the difference between groups’ means ranged from −3.29 to 6.49, which reveals the homogeneity of both groups. Consequently, the participants in the experimental and control group participants were homogeneous at the beginning of the study.

3.5. Independent sample t-test for the post-test

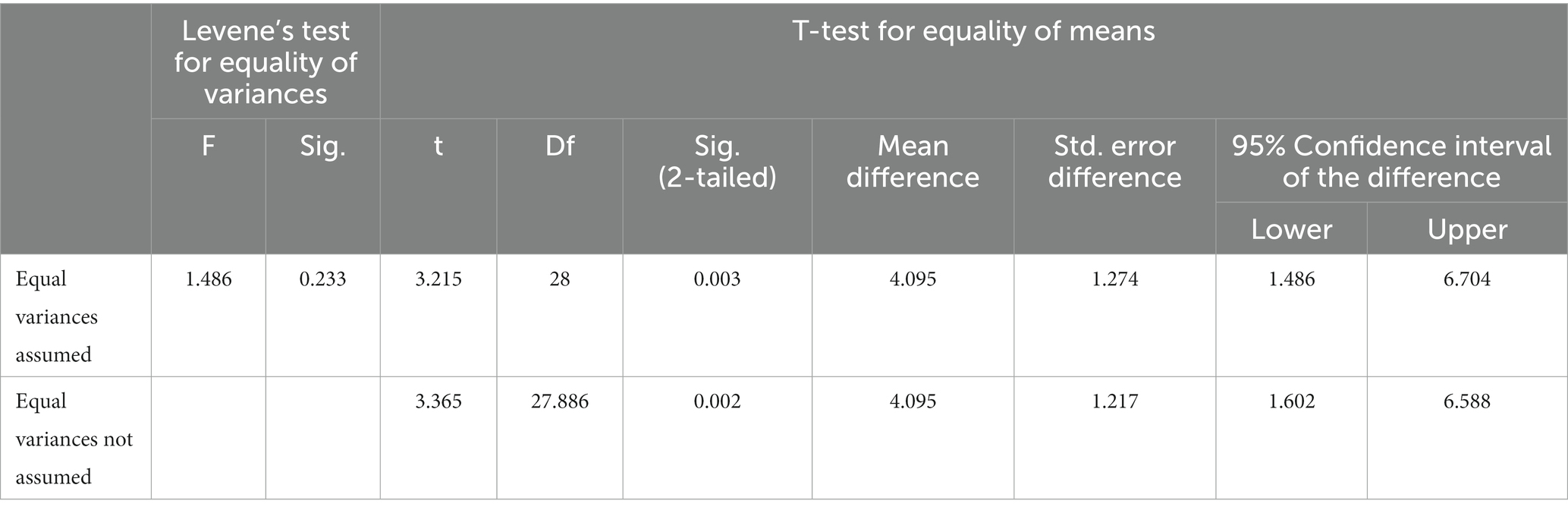

Likewise, an independent sample t-test was conducted for the items included in the post-test. The independent sample t-test showed that the learners in the experimental group performed better than the control group on the post test. The results are presented in Table 6.

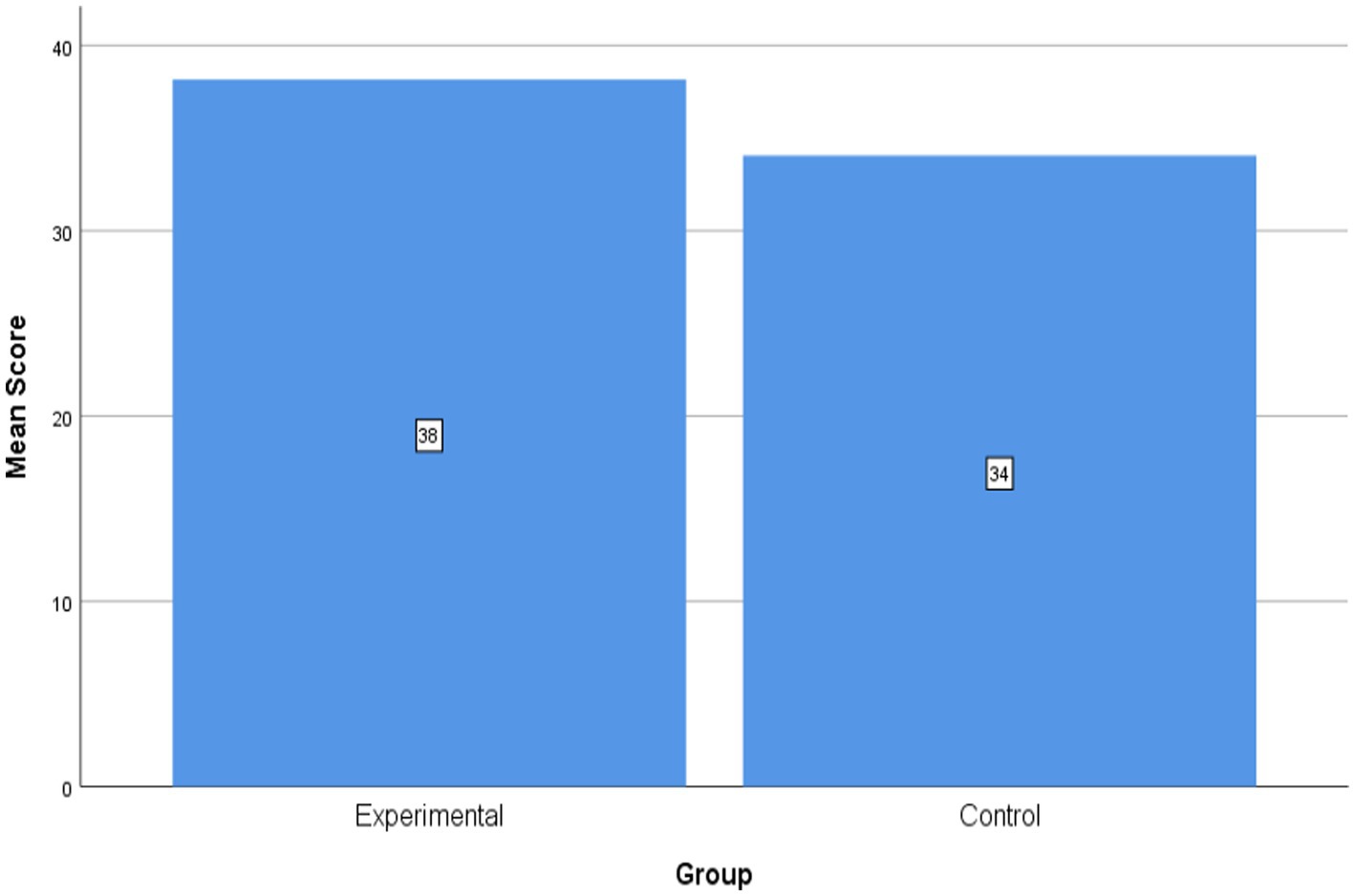

Table 6 reveals that there was a significant difference between the performances of the participants in the experimental and control groups. The results of the independent-sample t-test as displayed in Table 6 indicates that the level of significance was less than 0.05 [t (28) = 3 0.21, p = 0.03 (two-tailed; p < 0.05)]. Therefore, the participants in the experimental group outperformed their counterpart. Furthermore, the 95% confidence interval around the difference between groups’ means ranged from 1.48 to 6. 70. In addition, Figure 3 elaborates the mean scores of the two groups on the post test.

Figure 3 illustrates there was a significant difference between the scores of the two groups which was due to the innovative technique of using podcast for the participants in the experimental group in comparison to the participants in the control group who were taught based on traditional approach. Although the participants in the both groups increased their knowledge of English proverbs, the participants in the experimental group outperformed the participants in the control group.

3.6. Results of the questionnaire

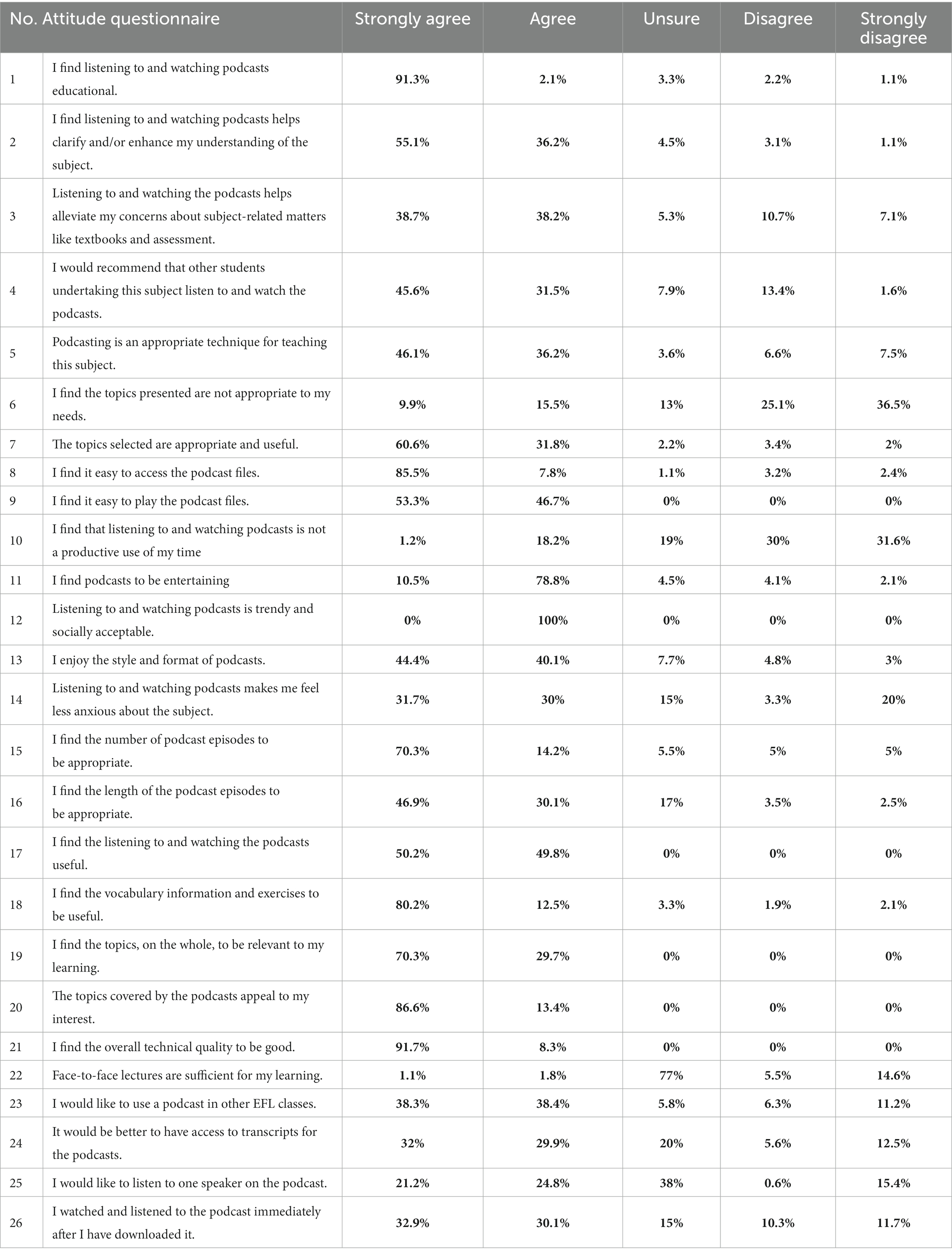

The second question explored the attitudes and beliefs of the participants in the experimental group in terms of learning English proverbs through video podcasts. A questionnaire was administered at the end of the intervention. Table 7 illustrates the findings of the questionnaire and the percentage frequencies for each item. To facilitate the interpretation of nominal categories, “strongly agree” and “agree” were reduced to positive responses; “strongly disagree”, and “disagree” was reduced to negative responses.

Nearly all the participants (93.4%) revealed their positive responses and found listening to and watching podcasts educational (item 1). Correspondingly, almost all the participants (91.3%) responded positively and believed that podcasts helped them to enhance their understanding of the subject (item 2).

An overwhelming number of the participant (76.9%) responded positively that podcasts alleviated their concerns about subjects like textbooks and assessments (item 3). Correspondingly, a good majority of the participants (77.1%) reported positively and responded that they would recommend other students undertaking this subject regarding the benefits of listening to and watching podcasts (item 4).

Moreover, an overwhelming number of the participants (82.3%) responded positively that using podcasts is an appropriate technique for teaching this subject (item 5). A majority number of the participants (61.6%) disagreed with the statement that the topics presented were not appropriate to their needs (item 6). Nearly all the participants (92.4%) responded positively concerning the topics were appropriate and useful (item 7). Correspondingly, an overwhelming number of the participants (93.3%) in the experimental group found it easy to access the podcast files (item 8).

Furthermore, all the participants (100%) responded positively that it was easy to play the podcast files (item 9). In addition, a substantial number of the participants (61.6%) disagreed with the statement that listening to and watching podcasts was not a productive use of their time (item10). A good majority of the participants (89.3%) provided positive responses that podcasts were entertaining (item 11). Furthermore, all the participants (100%) agreed that listening to and watching podcasts was trendy and socially acceptable (item12). An overwhelming number of the participants (84.5%) reported positively that the style and format of podcasts were satisfactory (item13). A considerable number of the participants (61.7%) responded that listening to and watching podcasts makes them feel less anxious about the subject (item 14). Correspondingly, a vast majority of the participants (84.5%) responded positively that the number of podcast episodes were appropriate (item 15). In addition, a substantial number of the participants (77%) provided positive responses with respect to the length of the podcast episodes (item16).

Interestingly, all the respondents (100%) unanimously believed that the podcasts were useful (item 17). Similarly, almost all the participants (92.7%) found the information provided about the vocabulary and exercises useful (item 18). Most importantly, all the participants (100%) reported positively that the topic of the proverbs were relevant to their learning (item19). Similarly, all the participants (100%) reported positively that the topics of the podcasts were interesting (item 20). Correspondingly, all the participants (100%) responded positively regarding the technical quality of all the podcasts (item 21).

With respect to item 22 which explored the participants opinions whether face-to-face lectures was sufficient for their learning, a considerable number of the respondents (77%) selected the option “unsure” (item 22). A substantial number of the participants (76.7%) responded positively to use podcasts in other EFL classes (item23). In addition, a substantial number of the participants (62%) preferred to have access to transcripts of the podcasts (item 24).

With respect to item 25, 46% preferred listening to one speaker on the podcast. On the other hand, 38% of the participants selected the option “unsure” for the above-mentioned item. Finally, a considerable number of the participants (63%) responded positively that they listened to and watched the podcast immediately after downloading it (item26).

4. Discussion and conclusion

The first research question sought to examine the extent to which there was any significant difference between the traditional approach of teaching English proverbs and video podcasting-based instruction. The findings of this study revealed that podcasts can enhance students’ proverb learning better in comparison to traditional classroom instruction. Moreover, the findings of this study support the results of earlier studies that participants learn English language, mainly English proverbs, and idioms, via podcasting compared to those participants who learn English language using traditional instruction (Chen Y. et al., 2014; Al-Qahtani, 2015; Lee and Kim, 2018).

The results of this research also reject the previous studies which challenged using podcasts in teaching languages to students (Kessler and Bikowski, 2010; Kim, 2017; Lee and Chan, 2019). Also, the results of the post-test revealed that there was a difference between these two groups (Table 6). In addition, the findings confirmed that mobile-based applications, including podcast applications, can be helpful in learning proverbs. To learn proverbs more effectively and efficiently, EFL learners can employ such applications in the process of learning proverbs in conjunction with additional instructional materials. In order to fulfill EFL learners’ immediate and delayed needs, teachers can use technology in different educational environments.

The findings of the current study are in consistent with the studies conducted by Al-Qahtani, 2015 who asserts that students who used video podcasts had higher scores in comprehension and retention tests in comparison to students who were deprived of using them. Contrary to the findings of Kennedy and Trofimovich (2008), who mentioned that podcasts did not significantly affect EFL learners’ language learning. The findings of the current study revealed that video podcasts could have significant impact on learning English proverbs by Iranian EFL learners. Vaughan (2002) believed that multimedia could provide an authentic context for language learning and provide an opportunity for interaction and communication. Podcasts can be used to promote different skills in the process of foreign language learning (Zarina, 2009). Correspondingly, podcasts application proved fruitful to enhance the learning of English proverbs in academic context. Mobile applications like podcasts, which integrate video and audio files arouse the interests of EFL learners. Moreover, smartphone’s Podcast application can provide a natural environment and accelerates learning. Based on the findings of the current study, incorporating podcast applications in educational settings provides opportunities to the participants to become autonomous learners. Moreover, mobile applications like Podcasts in classrooms can provide a collaborative and cooperative opportunity for EFL learners to learn English proverbs.

The second research question explored the attitudes and beliefs of the participants in the experimental group in terms of learning English proverbs through video podcasting. Based on the results of the questionnaire, participants in the experiment group were in favor of learning English proverbs via video podcasting. Contrary to the findings of Kessler and Bikowski (2010) who mentioned that students in their study encountered difficulties while downloading and having access to podcasts due to limited internet connection or lack of access to appropriate devices, the findings of the questionnaire (item 8) revealed that nearly all the participants (93.3%) of the experimental group had access to the podcast files easily through internet. The results of the questionnaire also confirmed that mobile learning, especially podcasts, can facilitate interaction and technology such as smartphones, provides flexible materials that can be within reach at any time in different contexts. Due to the communicative nature of language learning, these features contribute to more relaxed learning experiences, and thus motivate language learners to pursue challenging tasks such as learning English proverbs.

Therefore, this study was designed to introduce technology as a solution to solve Iranian EFL learners’ problems of learning English proverbs.

A few limitations in this study are worth mentioning due to administrative and logistical difficulties. The findings of this study were limited to 30 undergraduate advanced students majoring in English Language and Literature at Yazd university who had enrolled in a course called Listening & Speaking. Even though generalizations of this study may be limited, prospective future studies can be conducted on a substantial number of participants studying different specialized English courses. This study utilized video podcasts; prospective future studies can be conducted utilizing other types of podcasts to teach English proverbs. Finally, additional studies can utilize productive tests to examine the learning of English proverbs. The current study only investigated the short-term effects of video podcasting on learning English proverbs of Iranian EFL learners; consequently, it is recommended that prospective researchers investigate the long-term effects of video podcasting in innovative academic contexts and in different educational environments.

This study can be one of the initial studies in terms of learning English proverbs in a non-native environment and the effectiveness and usefulness of Podcast applications. Despite the limitations of the current study, the findings of the current study can have significant implications for language teachers not only at the national level, but also at the international level. The findings of this study would raise the awareness of EFL curriculum designers, teachers and materials writers to plan courses and design materials providing opportunities for learners to utilize mobile applications like video podcasts. Correspondingly, in educational settings, mobile applications can be effective to impart knowledge of language aspects namely vocabulary, grammar, idioms and develop the language skills of EFL learners. Most importantly, teachers should take into consideration the learners’ needs, lacks and wants and design their courses in order to fulfill students’ immediate needs (short term) and delayed needs (long term). Selecting study skills and techniques can develop learners’ target language proficiency. Teachers can offer opportunities for EFL learners to discuss and share their knowledge with their classmates using mobile applications like video podcasts. These techniques can provide learners with multiple opportunities to increase their metalinguistic awareness and become autonomous learners.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The research involving human participants was reviewed and approved by Yazd University. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study (Approval number:34, Date:2022-10-09.34/2022).

Author contributions

Both authors have analyzed the collected data and contributed to the development of the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akpinar, M. (2010). A research on using idioms and proverbs in Turkish education for foreign people. Journal of Science, TUBAV 2, 30–41.

Al Qasim, N., and Al Fadda, H. (2013). From call to Mall: the effectiveness of podcast on EFL higher education Students' listening comprehension. Engl. Lang. Teach. 6, 30–41. doi: 10.5539/elt.v6n9p30

Alavinia, P. (2016). The study of the role of English proverbs in teaching social and cultural beliefs to ESL students in Iranian high schools. Journal of Language Teaching & Research 9, 401–425.

Al-Qahtani, M. (2015). The effectiveness of podcasting in teaching English as a foreign language to Saudi Arabian students. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange 8, 1–14.

Bennett, P., and Glover, P. (2008). Video streaming: implementation and evaluation in an undergraduate nursing program. Nurse Educ. Today 28, 253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2007.04.005

Chen, Y. L., and Chung, Y. C. (2008). The effect of personal innovativeness on mobile shopping value and loyalty. Int. J. Electron. Bus. Manag. 6, 153–160.

Chen, Y., Wang, Y., and Chen, N. S. (2014). Is FLIP enough, or should we use the FLIPPED model instead? Computers and education 79, 16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2014.07.004

Chen, C., Wang, L., and Xu, L. (2014). A study of video effects on English listening comprehension. Studies in Literature and Language 8:53. doi: 10.3968/4348

Copley, J. (2007). Audio and video podcasts of lectures for campus-based students: production and evaluation of student use. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 44, 387–399. doi: 10.1080/14703290701602805

Crippen, K. J., and Earl, B. L. (2004). Considering the effectiveness of web-based worked example in introductory chemistry. J. Comput. Math. Sci. Teach. 23, 151–167.

Dupagne, M., Millette, D. M., and Grinfeder, K. (2009). Effectiveness of video podcast use as a revision tool. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 64, 54–70. doi: 10.1177/107769580906400105

Foertsch, J., Moses, G. A., Strikwerda, J. C., and Litzkow, M. J. (2002). Reversing the lecture/homework paradigm using eTeach web-based streaming video software. J. Eng. Educ. 91, 267–274. doi: 10.1002/j.2168-9830.2002.tb00703.x

Gorjian, B. (2006). Translating English proverbs into Persian: a case of comparative linguistics. Advances in Digital Multimedia (ADMM) 1, 140–143.

Green, S., Voegeli, D., Harrison, M., Phillips, J., Knowles, J., Weaver, M., et al. (2003). Evaluating the use of streaming video to support student learning in a first-year life sciences course for student nurses. Nurse Educ. Today 23, 255–261. doi: 10.1016/S0260-6917(03)00014-5

Griffin, D. K., Mitchell, D., and Thompson, S. J. (2009). Podcasting by synchronising power point and voice: what are the pedagogical benefits? Comput. Educ. 53, 532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2009.03.011

Güven, A. Z., and Halat, S. (2015). Idioms and proverbs in teaching Turkish as a foreign language; Istanbul, Turkish teaching books for foreigners sample. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 191, 1240–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.536

Heilesen, S. B. (2010). What is the academic efficacy of podcasting? Comput. Educ. 55, 1063–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.05.002

Henry, A. (2011). You tube hits 3 billion views per day, 48 hours of video uploaded per minute. [web log post]. Available at: http://www.geek.com/articles/news/youtube-hits-3-billion-views-per-day-48-hours-of-video-uploaded-per-minute-20110526/.

Hill, J. L., and Nelson, A. (2011). New technology, new pedagogy? Employing video podcasts in learning and teaching about exotic ecosystems. Environ. Educ. Res. 17, 393–408. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2010.545873

Infographics (2010). You Tube Facts & Figures (history & statistics) [web log post]. Available at: http://www.website-monitoring.com/blog/2010/05/17/youtube-facts-andfigures-history-statistics/

Jarvis, C., and Dickie, J. (2009). Acknowledging the ‘forgotten’ and the ‘unknown’: the role of video podcasts for supporting field-based learning. Plan. Theory 22, 61–63. doi: 10.11120/plan.2009.00220061

Kennedy, S., and Trofimovich, P. (2008). Intelligibility, comprehensibility, and accentedness of L2 speech: the role of listener experience and semantic context. Canadian Modern Language Review 64, 459–489. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.64.3.459

Kessler, G., and Bikowski, D. (2010). Developing collaborative autonomous learning abilities in computer mediated language learning: attention to meaning among students in wiki space. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 23, 41–58. doi: 10.1080/09588220903467335

Kim, J. (2017). The effects of mindfulness meditation on nursing students' perceived stress and coping strategies. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 7, 64–70.

Kukulska-Hulme, A., and Shield, L. (2008). An overview of mobile assisted language learning: from content delivery to supported collaboration and interaction. ReCALL 20, 271–289. doi: 10.1017/S0958344008000335

Lee, M. J. W., and Chan, A. (2007). Pervasive, lifestyle-integrated mobile learning for distance learners: an analysis and unexpected results from a podcasting study. Open learning. The Journal of Open and Distance Learning 22, 201–218.

Lee, J. J., and Chan, A. (2019). Exploring the motivations and perceived learning outcomes of podcast listeners. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 22, 97–108.

Lee, J., and Kim, H. (2018). The effects of social media on college students. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange 11, 1–14.

Leijen, A., Lam, I., Wildschut, L., Simons, P. R. J., and Admiraal, W. (2009). Streaming video to enhance students’ reflection in dance education. Comput. Educ. 52, 169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2008.07.010

Liang, M., and Li, X. (2016). Podcasts in higher education: students’ and instructors’ perspectives. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange 9, 1–14.

Litovkina, A. T. (1998). “An analysis of popular American proverbs and their use in language teaching” in Die heutige Bedeutung oraler Traditionen/the present-day importance of Oral traditions: Ihre Archivierung, Publikation und index-Erschließung/their preservation, publication and indexing. eds. W. Heissig and R. Schott (Springer Nature Group) 131–158.

Loomes, M., Shafarenko, A., and Loomes, M. (2002). Teaching mathematical explanation through audiographic technology. Comput. Educ., 38 (1–3), 137–149, doi: 10.1016/S0360-1315(01)00083-5

McCombs, S., and Liu, Y. (2007). The efficacy of podcasting technology in instructional delivery. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning 3, 123–134.

Mieder, W. (2006). “The proof of the proverb is in the probing”: Alan Dundes as pioneering Paremiologist. West. Folk. 65, 217–262.

Nippold, M. A., Allen, M. M., and Kirsch, D. I. (2000). How adolescents comprehend unfamiliar proverbs: the role of top-down and bottom-up processes. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 43, 621–630. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4303.621

Oxford Languages. (2021). Podcast. In Oxford languages online dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/

Reynolds, P. A., and Mason, R. (2002). On-line video media for continuing professional development in dentistry. Comput. Educ. 39, 65–98. doi: 10.1016/S0360-1315(02)00026-X

Shephard, K. (2003). Questioning, promoting and evaluating the use of streaming video to support student learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 34, 295–308. doi: 10.1111/1467-8535.00328

Shim, J. P., Shropshire, J., Park, S., Harris, H., and Campbell, N. (2007). Podcasting for elearning, communication, and delivery. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 107, 587–600. doi: 10.1108/02635570710740715

Smith, A. (2010). Home broadband. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Available at: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Home-Broadband-2010.aspx.

Traphagan, T., Kusera, J. V., and Kishi, K. (2010). Impact of class lecture webcasting on attendance and learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 58, 19–37. doi: 10.1007/s11423-009-9128-7

Vajoczki, S., Watt, S., Marquis, N., and Holshausen, K. (2010). Podcasts: are they an effective tool to enhance student learning? A case study from McMaster University, Hamilton Canada. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia 19, 349–362.

Wang, H. C., and Chen, C. W. Y. (2020). Learning English from YouTubers: English L2 learners’ self-regulated language learning on YouTube. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching. 14, 333–346. doi: 10.1080/17501229.2019.1607356

You Tube (2011). In Wikipedia. Available at: <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/You Tube>.

Keywords: EFL learners, MALL, proverb learning, technology, video podcast

Citation: Nikbakht A and Mazdayasna G (2023) The effect of video podcasts on learning English proverbs by Iranian EFL learners. Front. Educ. 8:1193845. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1193845

Edited by:

Antonio P. Gutierrez de Blume, Georgia Southern University, United StatesReviewed by:

Manijeh Youhanaee, University of Isfahan, IranSomayeh Baniasad-Azad, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Iran

Copyright © 2023 Nikbakht and Mazdayasna. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Golnar Mazdayasna, Z29sbmFybWF6ZGF5YXNuYUB5YWhvby5jb20=

Ahmadreza Nikbakht

Ahmadreza Nikbakht Golnar Mazdayasna

Golnar Mazdayasna